Shevlin Sebastian's Blog, page 14

June 6, 2023

It’s always better to remember your roots

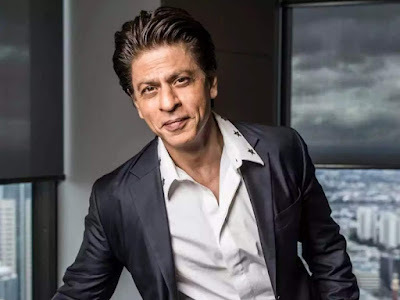

Photo: Shah Rukh Khan

By Shevlin Sebastian

A friend told me a journalist met a famous politician. He asked her how many Twitter followers the newspaper had. She mentioned a number. He smirked and said, “I have double that. So why should I talk to you and waste my time?”

I had a similar experience. A few years ago, a famous woman police officer came to Kochi from Delhi. I met her to do an interview. She asked me the same question about the number of followers the newspaper had. I made a guess. She also smirked and said, “I have double that of your newspaper. Is there any need to talk?”

Her words stumped me, and I remained silent. No interview took place. It was only a day later that I came up with a riposte. I should have said, “Madam, it was the media which made you famous. You are biting the hand that fed you.”

This is familiar behaviour. For over three decades, I have seen many people in sports, arts, politics, literature, and films who have come to newspaper and magazine offices in search of coverage. Sometimes, they got it. Sometimes, they didn’t. But once they became famous and successful, they would keep the press at bay, even the ones who provided coverage at the very beginning.

Being ungrateful is a widespread human trait. About 99 percent of people are ungrateful to the people who helped them on their journey. Too many of them have also pretended they did not climb the ladder to success. They seem to indicate they reached the top by magic. This is dehumanising. By refusing to acknowledge your roots, you damage your inner self.

One who seems to have kept his head on his shoulders is superstar Shah Rukh Khan. On Instagram reels, you can hear him say that there were many people who played a role in his success. It was not a one-man success story. Without the contributions of others, he would not have become the star he became.

Shah Rukh always spoke about the need to spend time with yourself at least once a day, to get an inner perspective and balance. In that way, he was able to counter the intense adulation that would have swept any other man aside. “There’s a personal me, there’s an actor me, and there’s a star me,” he said.

Shah Rukh has kept outward success from contaminating his soul.

Fame, power and money. These are the three most dangerous things in the world. If you get an overdose of even one, it can send you into a tailspin. It is the rare human being who can remain unswayed and remain true to his inner self.

Once you get swept away, your ego gets bloated up, you think no end of yourself; you preen and surround yourself with sycophants. This has a tragic effect. Your intuition goes to sleep as your sense of importance runs rampant. That is when you make career mistakes and errors on the home front. Within a few years, you are unwanted and sometimes you become a laughingstock. Your career comes to a stop. Many turn to drink and drugs and professional sex for solace.

For all those people who are in the limelight today, they need to ask a simple question. Who was in the limelight ten years ago? Those names are no longer there today. They should ask a supplementary question: where are they now? Answer: Nowhere.

Here is a cautionary tale. Rajesh Khanna, the first Bollywood superstar, had 15 solo superhit films between 1969-71. He had become a craze all over India. Women begged him to marry them. Producers kowtowed to him. Directors begged him to act in their films. Ten years later, his films were coming out but they no longer rocked the box office. He had become a has-been.

Imagine how many actors started at the same time as Bollywood superstar Amitabh Bachchan. Where are they now? Some may have died. Others have faded away. Amitabh is one of the rare artists who has stayed relevant and popular over the decades. But for a few years in the 1990s and 2000s, it was touch and go for him.

After setbacks on the professional and financial front, Amitabh anchored a quiz show, ‘Kaun Banega Crorepati.’ That became a superhit and revived Amitabh’s professional career and financial resources. Imagine what would have happened if that had flopped? He would have headed towards oblivion and irrelevance.

So both the politician and the police officer at the beginning of this story should partake of a small dose of humility. Otherwise, they will inadvertently press the self-destruct button and become has-beens.

June 3, 2023

A taut psychological thriller

By George AbrahamWhile reading Shevlin Sebastian's book, 'The Stolen Necklace', I realised how the pen can be mightier than the sword because the pen can produce immortal books like the one he has written which a sword cannot. Shevlin has immortalised not only the astounding story of Thajudheen but also every other major and minor character that figures in the story with the magic touch of his 'pen.'The events described in the book happened a few years ago and created a stir in Kerala then, but public memory being short, the story had faded away. But Shevlin has reconstructed them so thoroughly and in such minute detail that they have returned to haunt and rattle the readers. It is a grim psychological thriller rather than a crime story as the emotions, the feelings, and the fright of an innocent man framed by the police and thrown behind bars for no fault of his are captured in the gripping narrative that shatters the faith of the common man in the system, though there is redemption at the end for the protagonist, which may not be the case for many others like him. It is with trepidation that one goes through the slow build-up, in the beginning, realising what terrible fate awaits Thajudheen, a happy family man enjoying his holidays in his native place. The pace picks up rapidly after the menacing appearance of the police in the narrative and the entire pain and anxiety that Thajudheen faces are transmitted to the reader. Some relief is provided only when his past is unfolded through various events which are described as if they happened yesterday. Thajudheen was lucky to have come out of the ordeal forced on him by the police and what an ordeal it was! He deserves a big salute for fighting to prove his innocence withstanding police brutality, his incarceration in jail and the several other tests by fire that he underwent in his young days and later. He is indeed a man of steel and should be an inspiration for all who are fighting life's hard battles everywhere in the world. The book unravels not only the injustice and inhumanity of the police force, including what awaits a man in the lock-up and jail but also the evolution of Thajudheen into a mature man through various troubled phases, including romantic ones, in his growing years, the murderous Kannur politics, the picture of Mumbai red light street and the insecurity, insensitivity and cruelty that one may encounter abroad, especially in the Gulf countries. Kudos to Thajudheen for the courage and strength he has displayed in overcoming the incredible obstacles he encountered in his life. There is mathematical and clinical precision by Shevlin in the manner in which every sentence is written from beginning to end which adds to the intensity of the story. Collecting such vast and diverse material from available records and conversations with Thajudheen would have been an epic struggle in itself. Sitting down and putting them to paper (or computer screen) to create a drama of this magnitude would have been the ultimate test for the author as a journalist who has blossomed into an astute writer and investigator of the deep recesses of the human mind and its pathos. The book has sufficient material to be made into a perfect cinematic thriller too.

By George AbrahamWhile reading Shevlin Sebastian's book, 'The Stolen Necklace', I realised how the pen can be mightier than the sword because the pen can produce immortal books like the one he has written which a sword cannot. Shevlin has immortalised not only the astounding story of Thajudheen but also every other major and minor character that figures in the story with the magic touch of his 'pen.'The events described in the book happened a few years ago and created a stir in Kerala then, but public memory being short, the story had faded away. But Shevlin has reconstructed them so thoroughly and in such minute detail that they have returned to haunt and rattle the readers. It is a grim psychological thriller rather than a crime story as the emotions, the feelings, and the fright of an innocent man framed by the police and thrown behind bars for no fault of his are captured in the gripping narrative that shatters the faith of the common man in the system, though there is redemption at the end for the protagonist, which may not be the case for many others like him. It is with trepidation that one goes through the slow build-up, in the beginning, realising what terrible fate awaits Thajudheen, a happy family man enjoying his holidays in his native place. The pace picks up rapidly after the menacing appearance of the police in the narrative and the entire pain and anxiety that Thajudheen faces are transmitted to the reader. Some relief is provided only when his past is unfolded through various events which are described as if they happened yesterday. Thajudheen was lucky to have come out of the ordeal forced on him by the police and what an ordeal it was! He deserves a big salute for fighting to prove his innocence withstanding police brutality, his incarceration in jail and the several other tests by fire that he underwent in his young days and later. He is indeed a man of steel and should be an inspiration for all who are fighting life's hard battles everywhere in the world. The book unravels not only the injustice and inhumanity of the police force, including what awaits a man in the lock-up and jail but also the evolution of Thajudheen into a mature man through various troubled phases, including romantic ones, in his growing years, the murderous Kannur politics, the picture of Mumbai red light street and the insecurity, insensitivity and cruelty that one may encounter abroad, especially in the Gulf countries. Kudos to Thajudheen for the courage and strength he has displayed in overcoming the incredible obstacles he encountered in his life. There is mathematical and clinical precision by Shevlin in the manner in which every sentence is written from beginning to end which adds to the intensity of the story. Collecting such vast and diverse material from available records and conversations with Thajudheen would have been an epic struggle in itself. Sitting down and putting them to paper (or computer screen) to create a drama of this magnitude would have been the ultimate test for the author as a journalist who has blossomed into an astute writer and investigator of the deep recesses of the human mind and its pathos. The book has sufficient material to be made into a perfect cinematic thriller too.(George Abraham is former Deputy Resident Editor of The New Indian Express, Kerala)

The Nightmare Begins

Excerpt from 'The Stolen Necklace' published in The South First:

The group inside the car stared at the policemen, their lips partly open, and breaths coming out in short bursts. Young Thazeem pressed his face against his mother’s arm. Had they been waiting for us? Thajudheen thought to himself. But why? Thajudheen’s upper teeth pressed into his lower lip.The houses around were in darkness. It seemed as if no one in the lane was watching the Football World Cup, even though the sport was a craze in northern Kerala.A policeman knocked thrice on Thezin’s window with his knuckles. Thezin pressed the button to lower the glass.The policeman said, ‘Where are you heading?’‘Our house is further down the road,’ said Thezin, pointing with his finger and keeping his voice calm.The policeman peeped into the vehicle and observed all the passengers, his glance moving from one person to the other. He had protruding eyes, with a fierce look that seemed to say, You are all prey. I am a lion looking for meat!Thajudheen counted eight police personnel. A couple of them, muscular men with sloping shoulders, had unsmiling faces. They stood near the second jeep.Three of them were in uniform including Sub-Inspector P. Biju of the Chakkarakkal police station. Biju had an erect posture, but this show of bravado was a result of his knowing that he was the powerful representative of state authority acting against a powerless individual.The policeman asked whether the boys could help them. The wheels of the second jeep had fallen into a rut. Could they bring out the jack?The three boys looked at each other. Then Thezin turned around to look at his father. Thajudheen nodded. Rezaihan switched off the engine. Since the air conditioner could no longer work, he pressed the button to bring down the glass panes of the windows.The boys tumbled out of the car. Rezaihan opened the boot. Thezin took out the jack. The trio walked towards the other jeep.Also read: Siddalingaiah, champion of Dalit cause, resisted through his poemsThe policeman looked at Thajudheen and said, ‘Can you step out?’Thajudheen pushed open the door. As Thajudheen stepped out, the law-enforcer raised his palm and told the women to stay where they were. Thazeem stared goggle-eyed at the cop. Thazleena and Nasreena remained silent.‘Can you help with the jeep?’ the policeman said.Thajudheen said he suffered from lower back pain. It had been a hectic day, and he felt tired. ‘My son and his friends will help you,’ he said.The policeman beckoned Thajudheen with his forefinger and said, ‘Please come to the front of the car.’‘W-why, sir?’ Thajudheen said.‘We need to discuss a matter.’When Thajudheen stepped forward, the policeman led him to the back of the jeep, facing their car. Now his family could not see him.‘Show me your ID?’ the policeman said, proffering his palm.‘Why do you want to see my ID, sir?’ said Thajudheen.‘Who knows, you may be a terrorist,’ he said.‘What are you saying, sir?’ said Thajudheen, as his mouth fell open inadvertently.Terrorism is a word everybody fears in India. Under The Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA) 2019, they could jail you for months or years without bail.‘Show it to me,’ the police officer insisted.Thajudheen took out his purse from the back pocket of his trousers, rummaged through the folds, and proffered the license.The man inspected it by switching on the flashlight of his mobile phone.He looked at the photo and then at Thajudheen.After a few seconds, he returned the card.‘Show me your Aadhaar card,’ he said.‘I don’t have it. It’s in the house,’ said Thajudheen.As they conversed, another policeman began taking a video of Thajudheen, while a third took photos on his mobile phone.‘Why are you doing this?’ said Thajudheen, raising both his hands in exasperation. ‘Am I a thief or what?’ All this took place while Biju watched silently from a distance.Four of them surrounded Thajudheen. One held his collar and said, ‘You snatched a necklace from a woman’s neck, and now you pretend to be a respectable family man,’ said another police officer.‘We are going to punish you,’ said another.Tiny drops of spittle from the policeman fell on Thajudheen’s face. All Thajudheen could see were bared teeth and widened eyes.They pushed Thajudheen from side to side. He grabbed for his spectacles which had slipped off his nose. What is happening? What necklace? Where? Surely, this is a case of mistaken identity, he thought.Hearing the loud voices, Nasreena, Thazleena and Thazeem pushed their way among the cops and stood near Thajudheen.The police stepped back. Thajudheen took this moment to put the spectacles back on. He took out his handkerchief and wiped the spittle off his face.Nasreena wrapped her arms around him from the back. Thajudheen felt relief as the warmth of her body and the strength she transmitted seemed to envelop him.He had met her as a giggly teenager. Now, she was a grown woman and a mother of three.Also read: Telangana registers most fake-news cases in country, TN secondThazeem held on to his father’s legs. Thajudheen reached out and placed a comforting palm on his back. Thazleena stood in front of her father, with hands on her waist. She had the anger of somebody whose happiness was about to be snatched away.‘What is the problem?’ said Nasreena.‘He stole a necklace,’ said one of the policemen. ‘We have proof.’‘Show it,’ said Nasreena.One policeman showed a grab taken from a CCTV on his mobile phone.Right at the edge of the photo, on the left, taken at an angle, at the height of a first floor, there was the image of a balding man with thick ears sitting on a white Honda Activa scooter. He was bespectacled and had a scraggly black beard. There was a black watch on the left hand.Behind the man, on the left, party workers had tied a red Communist flag to a lamppost.The date on the image: 5 July 2018. The time: 12.39.The man resembled Thajudheen. Even he thought so. But he did not own a scooter and could not recognize the place. Nor did he have a watch with a black dial.‘How did you get Thajudheen’s photo?’ said Nasreena involuntarily.Thajudheen stared at the photo without blinking his eyes.He finally said, ‘It looks like an old photo.’Suddenly, Sub-inspector Biju said, ‘We are going to arrest you.’(Published with permission from HarperCollins Publishers, India).The Stolen NecklacePages: 267.Price: ₹399.

The good news is that 'The Stolen Necklace' is No 1 in the criminology section of Amazon

My book, 'The Stolen Necklace' has been published

Author photos: VK Thajudheen (left) and Shevlin Sebastian

Author photos: VK Thajudheen (left) and Shevlin SebastianHi Friends,A happy moment has arrived! Today, May 17, HarperCollins India Publishers is bringing out our non-fiction book, ‘The Stolen Necklace’. Our grateful thanks to HarperCollins, one of India’s leading publishers as well as the world, and my agent, Anish Chandy.You can pre-order the book on Amazon (Rs 301; free delivery) and on the HarperCollins website. https://www.amazon.in/Stolen.../dp/9356296855/ref=sr_1_1...So, what is the book all about? VK Thajudheen, a Doha-based entrepreneur, flew to Kannur to attend his daughter’s wedding. Two days after the event, following a celebratory dinner, the family returned home. To their surprise, they found a group of police officers waiting there.They accosted Thajudheen, calling him a thief, and said he stole a gold necklace. Thajudheen asked them for proof. On a mobile phone, they showed a CCTV image of a man riding a scooter. It looked like Thajudheen. Even Thajudheen felt it looked like him. The police arrested Thajudheen and took him to jail. The 267-page book details what happened next. As the tagline says, ‘If it can happen to him, it can happen to you.’

May 11, 2023

When the credits stopped rolling

This is a short story about an ageing Bollywood scriptwriterBy Shevlin Sebastian

The people wore sad faces, as they offered condolences to Muzaffar Ali, in his house at Malad, Mumbai. His wife had passed away, at age 65, from a heart attack.

Muzaffar sat on a wooden chair, with a small pillow placed behind his lower back. On a wooden table near him, there was a cup of tea and a copy of the Hindi newspaper Hindustan.

The 68-year-old veteran Bollywood scriptwriter was not in the best of health. He had diabetes and high blood pressure. He had to take insulin injections and tablets to keep his pressure in control.

He was a scriptwriter whose stories were no longer accepted. “Sir, these are out-dated,” said one thirty-something director, as he stared at Muzaffar’s script resting on his lap. “People are not interested in village stories. Young people want a lot of action, sex and hi-jinks.”

Muzaffar did not feel angry. Trends change in cinema every ten years. He had been in it long enough to know that. New heroes, new concepts, and news ways of shooting.

Muzaffar was not the only one to be in this boat. Other scriptwriters of his age, his contemporaries, were twiddling their thumbs. They did not bother to write anything. But Muzaffar’s writing itch remained strong. And he worked every day. He felt he should be ready when the tide changed. But nobody knew how long that would take. He could be dead by then.

At the peak of his career, he had several hit films based on his scripts. In those times, Muzaffar went to many parties. He smoked cigars and drank Johnnie Walker whiskey. Many starlets approached him. Fluttering their eyelashes, they asked him to recommend him to directors.

Like most industry people, he took them to bed first. But unlike the others, if he felt the girl had talent, he would recommend them. A few got breaks. They were always grateful to him.

One or two told him they could lift their family out of poverty from the money they earned in the industry. Since he had not seen them on the screen, he assumed they had become high-class call girls. Later, he understood they were thanking him for giving them the access to the stars and the directors. One influential man led to another. And the currency notes poured in.

He heard stars wanted threesomes and foursomes. Some wanted to place handcuffs on them, tied to the bed’s posts.

One of South India’s top stars had a woman, with grey-black hair, and broad buttocks stationed in his van during the shooting. An ordinary-looking woman, she was supposed to be an expert in blow jobs. The star felt he acted better after she finished working on him.

The advantage was that the actor did not have to take off his costume and could return to the shoot quickly.

Of course, in these times of the #MeToo movement, it was a perilous time for actors. One tweet or a Facebook or Instagram post and their career would go up in smoke. Muzaffar knew the police could even arrest the stars. What a shame that would have brought their wives and families.

He wondered how the men tackled sexual temptations these days. A senior producer told him the starlets had to sign legal agreements which stated that the physical relationship was voluntary. But he was not sure whether this was true.

Muzaffar never imagined that one day his career would end. He had thought then that this success would continue forever. Unfortunately, that was not to be. A friend told him he was lucky to have a successful run that lasted 20 years.

He knew of many scriptwriters who had one hit and a string of flops. Thereafter, everybody avoided them like a man afflicted with chicken pox. The industry people were superstitious. They felt these scriptwriters brought bad luck. Many of them were in penury. Their families treated them with contempt because they could no longer earn a living. Most ended up as alcoholics. A couple of them committed suicide.

Muzaffar realised that in a creative industry like films, it is very difficult to have a long career. What you think is important is no longer important after a few years. The stories do not have a resonance with the audience. It was the rare artist who had a career that spanned decades.

Nowadays, desperate male stars did plastic surgery to remain young. He heard of an ageing superstar who, straight after the annual Filmfare function, had flown to London to get treated by one of England’s best cosmetic surgeons.

The doctor removed the wrinkles on the forehead, the crow’s feet around the eyes, pulled down the skin over the cheeks and lessened the neck lines.

Some stars took steroids, apart from weightlifting, to get six-pack bodies. Others went on protein-rich diets. One star, with his wife’s knowledge, installed a mistress in a nearby house so that he could feel and look young.

‘Wow,’ thought Muzaffar. ‘When you have too much money, fame, or power, you get into kinky sex.’ What about that industrialist who had sex with young boys? Muzaffar wondered whether his wife knew. The pimps always took the boys to the house. These pimps knew if they tried to blackmail this industrialist, they would end up as dead bodies floating in nearby ponds or rivers.

‘Sick,’ he thought as he shook his head and began reflecting on Bollywood once again.

He knew of many actors and actresses who had faded away. The point is when your career is over in your forties or fifties, what do you do after that? It is difficult to embark on another career. Fans would approach them in public places and ask, “Sir, when is your next film coming out?” The questioner knew very well that there were no roles to be had. This was the sadistic pleasure they got in plunging a knife into a man who was once up but was now down and out.

Most former stars would nod and walk away. If they were in a calm mood, these cold-hearted queries would ensure depression would rush in like a river in spate. It would take days before they restored their mental equilibrium. Thereafter, they avoided going out.

But there were stars who lasted for a long time. They had unmistakable charisma and talent. In Hollywood, there were people like Robert De Niro, Al Pacino and Tom Hanks. But they were also people who had grounded themselves, arrived on the set on time, learned their lines in advance, and behaved well.

Muzaffar remembered a video he had seen of De Niro. In it, the star said, “When things are going well, be calm. Don’t think you are on top of the world. You always gotta be wary. I have seen people come. I have seen people go. You should take what is good in your life and move forward cautiously. Everybody’s dispensable.”

Muzaffar had liked the video so much, especially the last line, that he had seen it many times. This was as true as it could get. And it was true for all professions, not only the film industry.

Like the other members of the industry, Muzaffar drank and smoked. But he did it in moderation. He had the mental discipline to control himself.

He gave his children, two sons and a daughter, an excellent education. They now lived prosperous lives in countries like Canada, the USA, and Australia. But they did not send him any money. And Muzaffar was too proud to ask for it.

But he was running out of money. Muzaffar could see the looming debt on the horizon.

On a recent morning, he did something unexpected. When he got up, he saw his wife was sleeping peacefully next to him. They had a loveless marriage. She had turned away from him because she knew he was sleeping with other women. From a marriage, it turned into a partnership.

Muzaffar got on top of her, placed a pillow over her face and pressed hard. He could feel her body struggling as she tried to push him away. But each time she did so, he felt a renewed surge of strength. In the end, it took about half an hour before she stopped breathing.

Muzaffar got off the bed and sat on the edge, his face in his hands. He could feel his entire body trembling. He couldn’t believe what he had done. But some deep, animalistic force had arisen in him and he seemed helpless in its power.

That there was a Rs 70 lakh life insurance policy in the name of his wife may have been the reason. And he was the nominee.

Muzaffar remembered the case of a woman star who had died in a pool at a five-star resort in Kuala Lumpur. It was not clear how she died because she had been an excellent swimmer. There were rumours that the husband, a producer, had got her drowned because of the huge life insurance policy in his wife’s name. His last film had flopped. He was up to his nose in debt. But nothing could be proved. In the end, family members cremated the body in Mumbai.

Muzaffar called his neighbour Dr. Homi Batliwala, who was the same age as him. When he entered the house, Muzaffar said, “It seemed my wife has suffered a heart attack.”

The doctor checked for the pulse. Then he lifted the eyelids and pointed a torch at the pupils. “It seems so,” Dr. Batliwala said. And he wrote the death certificate. Everything went smoothly after that. The burial took place within four hours, at the Kabristaan in New Mahakali Nagar. He would wait for a few months because he did not want to arouse any suspicion. Then he would cash the policy.

All’s well that ends well.

April 27, 2023

May The Force Be With You

Photos: DeenanathMangeshkar with his wife Shevanti. On her lap is Asha. Lata stands between herparents. On the right is Meena; The Mangeshkar siblings: (from left, frontrow) Usha, Lata and Meena; Asha and Hridaynath; LeBron James with hismother Gloria; The philosopher Osho

By ShevlinSebastian

Recently, I read a book on thelife of the legendary playback singer Lata Mangeshkar. In it, she recounted amemory when she was nine years old. She did her first performance with herfather at the Bhagwat Chitra Mandir auditorium at Solapur in 1939. After theduet, she fell asleep on her father’s lap while he continued to sing throughthe night. She felt her father’s love enveloped her. It also gave her a senseof security.

Lata adored her father,Deenanath Mangeshkar. He had realised his daughter had talent and strived toencourage her. It devastated the family when Deenanath died on April 24, 1942,at the age of 41. Lata, as the eldest, bore the responsibility of looking afterthe family. It comprised her mother, Shudamati, and siblings, Meena, Asha,Usha, and Hridayanath.

Throughout her life, Lata alwaysremembered her father with great fondness. She recounted the incident of hersleeping on her father’s lap many times.

Because she had such a goodrelationship with her father — the first male in her life — her laterencounters with men were positive. Many of them helped her during the earlystages of her career. These included composers, singers and directors.

It led me to a conclusion. Thefirst relationship with the opposite gender played a vital role in the way aperson regarded himself or herself. It would colour their reactions to theopposite gender later on in life.

When a daughter had a father whowas loving, she usually made the right choices in men in her later life. But ifthe relationship was one of fracture, lack of respect, and emotional damage,this had an opposite effect. Her attraction would be for a man who displayedthe same qualities. This resulted in unhappy and violent relationships.

The same is the case with theboy’s relationship with his mother. One of America’s greatest basketballplayers, LeBron James, spoke about the influence of his mother Gloria on hislife. Gloria was only 16 when she gave birth to James. His father, AnthonyMcClelland, a career criminal, had abandoned the family when James was a child.But it was Gloria’s faith and undying love that saved her son’s life.

Parents play a phenomenal rolein shaping their children’s mindset and attitudes. But too many parents taketheir responsibilities casually. Many fathers appear distracted at home. Liketheir children, they are also constantly staring at mobile phones. Many arereeling under immense office pressures. Sometimes, they take out their stressby saying hurtful statements to their children. They do not realise it then,but this has a lifelong impact.

As for the mothers, they have tobalance the pressures of running a home, as well as having a career and being amother. It can get overwhelming. Mothers, under stress, can also say things inanger that might hurt their children. And there is the added problem of parentsnot having successful marriages. This results in arguments and shouting betweenthem in front of the children. Sometimes, there is domestic violence.

All this has a devastatingeffect on the children. When they grow up, they will inflict the same damage onpeople around them and to their children. And the cycle carries on.

So, how to break it?

Mindfulness is one way.

This is something I have beenreading a lot about these days. How to watch your thoughts and get detachedfrom them. How to create a gap between the mind and the thought. In onlineresearch, I read that we have about 60,000 thoughts a day.

Wellness guru Deepak Choprawrote that behind every thought, there is a chemical reaction in the body. Thatmeans, daily, we have about 60,000 chemical reactions. Most of them arereactions to negative thoughts. Our body is a roiling furnace of negativity. Nowonder many of us have health issues.

Self development author WayneDyer said that our thoughts make or break our life. While some thoughts areoperating on a conscious level, and are easy to recognise, others are embeddedin the unconscious.

Almost all these thoughts arenegative. How to get rid of them?

John Selby, author of the book,‘Quiet your mind,’ wrote, “When you feel any negative emotion in your heart,it’s time to catch the thought or memory or buried assumption that isgenerating the emotion — and process that underlying thought so that it nolonger determines your mental and emotional condition.”

This is easier said than done.

The key is to live in thepresent moment. The philosopher Osho said we cannot do this by using the mind.

“The mind cannot exist in thepresent,” he asserted. “It exists only in the past or it projects into thefuture. It never comes in contact with the present.”

Osho felt we could live in thepresent by silencing the mind and its stream of thoughts. He called it theNo-Mind. This requires a superhuman effort. Spiritual seekers take decades ofmeditation to achieve this inner silence. How can ordinary people do it? But wehave to make the attempt.

Deepak Chopra believed thathigher consciousness is the only answer to the dark side of human nature. “Itis that part of you that is beyond the thoughts and feelings of the moment, thepart that never tires and never sleeps. Can you feel the deeper current ofconsciousness within you?”

This current is also called God,the Cosmic or the Universal Energy or the Source.

In January, American GrammyAward-winning record producer Rick Rubin published a book called ‘The CreativeAct: A Way of Being’.

In it, he said, “The Source isout there. A wisdom surrounding us, an inexhaustible offering that is alwaysavailable. We either sense it, remember it, or tune in to it.”

If parents can transformthemselves by silencing their minds and learn to live in the present moment,they will experience a life-changing spiritual experience. For this, they willhave to set aside time every day for meditation practices. Physical exercisealso has a calming effect on the mind. If parents can change, this will have aprofound effect on their children. They will grow up psychologically healthy.

Parents will then be able tounearth many more versions of geniuses, like Lata Mangeshkar and LeBron James.

April 2, 2023

When life stopped

This is a short story set in Bengal

This is a short story set in BengalBy Shevlin Sebastian

Barnali Mitra walks on bare feet, as if in slow motion on a bund between two paddy fields. She leans forward as she walks, looking at the ground. It is a misty morning. The sun hides behind clouds. She sees greyness all around. But when she looks down, she sees lustrous green saplings in the paddy fields. She observes they are only six inches tall. There is a layer of water in the fields. Barnali hears insects flying about. She also notices a couple of earthworms wriggling their red bodies across the wet mud by the bund.

But Barnali’s mood is heavy. It has been heavy for one-and-a-half years, because she lost her husband Aveek. He was crossing the highway. A truck ran over him. He died on the spot. This was the news report she often read in newspapers. But Barnali never imagined it would happen to somebody so close to her. Barnali did not recover. She was still in mourning. Hence, she wore no earrings or necklaces, nose or toe rings, make-up, lipstick, eyeliner or nail polish.

The villagers were worried. After six months, they told her to get over it. Barnali did not respond. One elderly man, in a white banian and loose-fitting pyjamas said, “You are young. Life is ahead. You have no children. There is nothing holding you back.”

Barnali stared at the old man. Her nose twitched as she felt an odour coming from his mouth. It seemed he had not brushed his teeth. ‘Here was somebody who was more bothered by what others did,’ she thought. ‘But he had forgotten to brush his teeth.’

What could she tell the old man?

Barnali nodded, smiled briefly, and walked away. Barnali always felt that words aggravated the issue. Silence quietened people. They calmed down. So she never responded to endless advice.

She herself was not sure why she continued to grieve. It was a weight she could not throw away. Like something was stuck in her throat. Like her legs felt leaden. There was no feeling in them. She walked barefoot. She hoped that when her soles touched the earth, she would experience something within her. But there was nothing. It seemed like she was floating instead of walking.

Maybe one day, she would shake off her lethargy and start living. If she had a child, it would have been the right distraction. Now, she lives alone, in a house purchased by her husband in her name. ‘Thank God for that,’ she thought. ‘Now nobody could take it away from me. Maybe Aveek had a premonition about his death and made this vital decision to buy it in my name.’ All the loans had been cleared because he had sold some family property.

Barnali gave up her job as a class five teacher. She now lives off her husband’s savings. How long could she carry on like this? She did not know. All she felt was heaviness. And when people looked at her with patronising sympathy, her head felt heavier. That was why she did not like to step out of the house.

But she was a human being. After a couple of days of sitting inside, she would feel like the bricks, cement, the walls and the tiles of the roof were crushing her. So she stepped out. And tried to feel something.

She inhaled the fresh air and listened to the breeze. She tried to feel it in her arms and concentrated on the whooshing sound in her ears. But her body and mind remained unmoved, detached, and uncaring.

At the other end of the Bund, she saw a man. Two people could walk on it side-by-side. She knew who he was. Bhaskar, a local politician, and a rumoured-to-be criminal. But the police had not caught him. Bhaskar drank hard, patronised prostitutes and swore loudly.

In the village, they knew about Bhaskar. But he had one saving grace, she knew. He treated women and children kindly. This showed he had something good in him. Barnali bit her tongue. She kept her eyes on the ground. She hoped they could go by without speaking. In silence, and without incident.

She could sense Bhaskar coming close. She concentrated hard on the mud in front of her. Her breath developed a stop-start pattern. She realised it had been a long time since she had painted her toes. Aveek always liked her painting her toenails red. “It looks fiery,” he said, and hugged her.

As they came abreast, Barnali looked at the ground. But Bhaskar caught her wrist. Her eyes opened in surprise. She looked at him.

“Barnali, what is happening to you?” he said calmly. “Don’t lose your life. Everybody has a fate. God decides it. You should accept it and move on.”

She did not know what to say. Barnali stood still, as if someone had electrocuted her. After a while, he let go of her wrist.

“I have a suggestion,” he said. “I am travelling to Kolkata tomorrow. Come with me. I am a politician and have an unsavoury reputation. I know that. But you will be safe with me. You need a break.”

Bhaskar’s soft voice contrasted starkly with his muscular body. It made her receptive to his suggestion. Against her will, she nodded.

“Come to the station at 8 am,” he said. They walked past and continued in opposite directions.

Barnali returned home after buying vegetables. She could not believe she had agreed to meet him. It seemed she was losing her sanity.

She tossed and turned in the night. But the next day, she was at the station at 8 am.

They were in the same compartment. Because there were many known people from their village, they did not talk to each other. Barnali got a window seat. She looked out and stared at the paddy fields as the train whizzed past.

Bhaskar held the rod above him. When he was in her line of sight, she looked at him. He had thick biceps and broad arms. Barnali thought he did weightlifting. Aveek did not have these arms. He was a sensitive literary type, interested in poetry, books and films. Aveek wore a juba and a kurta most of the time. They had met in college and fallen in love. He was sensitive and kind. It was an easy marriage. They got along well.

At Howrah they stepped out. Bhaskar showed with his eyes to follow him. So she did. They walked about 400 metres from the station when Bhaskar stopped and waited for Barnali to come up.

“Hi,” he said.

She gave a half smile.

“Let’s take a cab,” he said.

She nodded.

He raised his palm. A taxi stopped beside them. They got in. He said, “Sudder Street.”

Barnali looked out of the window. Kolkata offered a stark contrast to the village. The massive numbers of people, the thick black fumes from buses, trucks, taxis and cars. The noise of so much traffic moving about, and people blowing horns all the time.

Bhaskar remained silent. He checked some messages on his WhatsApp.

Because of excessive traffic, it took 45 minutes to reach the Lytton Hotel. Barnali immediately knew it was a swanky hotel. This was confirmed when she entered the room. There was a king-size bed. A sofa to one side. A low table. And the air conditioner’s cool hum.

Bhaskar pulled the thick curtain to one side so sunlight streamed in.

She sat on the edge of the bed while he sat on the sofa.

“What would you like to drink?”

“Lime juice would be okay,” she said.

She did not feel nervous at all, even though she knew where this was going. But Barnali remained calm and composed.

He called room service and ordered juice, as well as chilled Heineken beer.

As she looked around, Barnali realised Bhaskar had money on him. She knew it was illegal money, but so many people deal with illegal money in India. Business people evade tax. All government officials who took bribes evade tax. Even professionals like doctors and lawyers avoid paying tax. The only difference was that Bhaskar broke the law. And that was unpalatable for society. Everybody looted, but they did it in the shadows.

As they sipped their drinks, Bhaskar asked about her life. For one-and-a-half years, Barnali had waited for the right person to come along to open up. And she opened up.

She spoke about the miserable existence she led after her husband’s death. She spoke about the shock she experienced when seeing her husband’s dead body. It reminded Barnali of her father’s untimely death. Losing two men she adored. She spoke about how she missed their masculine energy. While it was a world today when women disparaged men, Barnali said she loved men. She liked their physical strength and straight-forwardness. And their uncomplicated bodies. Barnali felt a sense of security when she was with them.

Barnali did not have a terrible experience with a man, unlike many of her peers. Men molested her friends on trains, buses, inside malls, and while walking on the streets. Even close relatives did not miss their chance. “I am one of the lucky ones,” she said. “Or maybe I let out a vibration showing I liked men. So they let me be.”

Bhaskar sipped his beer. He had instinctively sensed that the need for the hour was to listen. The words tumbled out of Barnali in a never-ending flow. It was like a waterfall during the rainy season following a drought.

After an hour, Barnali felt tired. She lay down on the bed and closed her eyes. Her mind and body needed silence now. Her body had trembled with the effort of speaking. She had released all the pain, guilt, fear, anger, and frustration inside her. They no longer tormented her any more. Barnali felt free after a long time.

After half an hour, when she opened her eyes, she saw Bhaskar standing at the window and looking out.

She looked at her watch. It was 12.15. She walked to the window and stood next to Bhaskar. He put his arm around her shoulders. She leaned on him. That was the signal he needed. Bhaskar led Barnali to the bed.

The love-making began.

After a while, as she inhaled his masculine odour, she whispered, “Can you push harder?”

Bhaskar turned on the effort.

Barnali felt, as she withstood the pounding, that the walls in her brain were crumbling.

He kept up a steady rhythm, grunting occasionally.

After ten minutes, Bhaskar slowed down. He took a deep breath and leaned in. They kissed, as Bhaskar stopped moving. But Barnali could feel his hardness inside her. She realised he needed to breathe. There was perspiration on his forehead. He had used a lot of effort.

After a while, he began moving.

Then she got on top. This time, she became breathless. She had been out of touch with sex for so long. But Barnali felt satisfied and complete. It brought her back from the brink of whatever mood she had been in for so many months. They lay side by side. Then they drifted off to sleep. When they awoke, Barnali realised it was 1.45 p.m. She could feel her stomach contracting with hunger.

Bhaskar got dressed and called room service and ordered lunch. Barnali knew he was also hungry and that had become acute following their sexual activity. By this time, Barnali had gone to the bathroom carrying her blouse and saree to get dressed.

She opted to take a quick shower. Barnali used perfumed soap and rubbed it all over her body. Bhaskar’s sweat and body odour pressed into her skin.

Bhaskar pulled the curtain back. Light flooded the room. Soon, Barnali came out. Lunch arrived. They ate silently. Chicken biryani, salad, papad and pickles followed by two cups of ice cream.

They ate with their hands in silence and speed. Both had suffered from hunger pangs. They rested for 15 minutes. Bhaskar lit a cigarette and blew smoke rings towards the ceiling. Barnali walked to the bathroom and rinsed her mouth. Bhaskar said, “Let’s go.”

They left the hotel after he paid the bill.

He turned to look at her and said, “I have some work. I will put you in a cab. You can go straight to the station. I will come later.”

She nodded, relieved. Barnali wanted to be by herself, so that she could figure out the emotions she was going through. On the street, an empty cab pulled up. He raised a palm. The cab stopped, and she got in. Barnali waved at Bhaskar.

As she waited at Howrah station, thoughts came to the surface, despite the continuous din all around. Yes, she was going to leave Burdwan. She would come to Kolkata and look for a teacher’s job. Barnali realised she needed the anonymity of a large city to find out the next steps in her life.

She knew there was a reason Aveek died, and she had become alone. But she still did not know what would be the purpose of her life. Maybe her destiny was to live outside of convention, to forge a new and creative way of living. She would give the house at Burdwan on rent, so that some money came her way every month.

Barnali would take a flat in Kolkata. She would introduce Bhaskar as her brother to the landlord. That will enable him to come often without raising suspicions.

After that, she did not know what would happen in her life.

March 26, 2023

A conversation with a cab driver

By Shevlin Sebastian

Driver Mulik Nilesh Dadaso is driving the cab which I hired at 100 kms/hour. Abroad, this may be fine. But on the Pune-Mumbai Expressway, it is risky. There is no lane discipline. Drivers in cars, buses or trucks cut in and out of lanes at high speed. One tiny error of judgement might cause an accident.

Mulik said that two days ago, a large container truck, whose brakes had failed, had hit a bus from behind. Four men fell off the bus on the road. Another bus, coming from behind, ran over them. They died immediately.

Mulik said that he sees an accident almost every other day. But he admitted it no longer affected him. “If I get disturbed mentally, I will get scared and it will affect my driving,” he said.

He has been doing this route almost every day for the past several years. It is his most lucrative assignment. He earns Rs 2000 as profit travelling to Mumbai and back. “That’s enough for the day,” he said. “I don’t drive after one to-and-fro trip.”

Of course, the time taken varies. If it is in the morning rush hour, then it could take four hours. That is the case in the evening when he is returning from Mumbai. But in the pre-noon and in the afternoon, he can do it in one and a half hours. However, in the monsoon season all these journeys become longer.

These long hours have taken a physical toll. Mulik has recurring back pain. But when he stops driving and walks around a bit, the pain recedes. Since he is in his late thirties, his recovery is quick. But I am apprehensive things will no longer be the same after a decade or so.

This is because I had done a story, in May, 2020, about auto rickshaw drivers in Kochi. Many have shoulder and back problems because of the constant use of the gear and leg pedals. A 46-year-old, after two decades behind the wheel, had to stop driving because of severe back pain.

As for Mulik, he lives in Bhugaon, 14 km from Pune. His wife is a homemaker, while his six-year-old son studies at a private school. The second son is two years old. “Private schools are more expensive, but it is imperative that my children get an excellent education,” he said. “But now, I have heard that government schools are getting better. Later, I may shift my son to a government school.”

Mulik is from Satara, 112 km from Bhugaon. The family grows sugarcane on land they own. But in the past three years, the yield has not been high. There is also a lack of water because of a lack of rain. Mulik bemoaned the impact of climate change.

Last month, he received another blow. His 60-year-old father died of a sudden heart attack. Now his elder brother, a cab driver, has shifted his family from Mumbai to his ancestral home. The aim is to ensure their mother is not alone. Once a month, Mulik drives in his car to meet his mother and to survey the fields.

The subject changes to the topic of development. He lauds the Bandra-Worli Sea link. User charges begin at Rs 80. “The average person cannot afford to use it every day,” he said. “But for rich people and Bollywood stars, time is money. What is 80 rupees for them? It is nothing. For them, this link is an enormous benefit.”

It is unnerving that messages keep popping up on Mulik’s mobile phone. He reads them and drives at the same time. Through the rear-view mirror, I can see his eyes darting from the screen to the road and back again. ‘So risky,’ I thought.

I enquire about the legislator Eknath Shinde. He precipitated a division in the Shiv Sena and formed his own government with the BJP in June 2022. Mulik said, “The people have sympathy for Uddhav [founder Bal Thackeray’s son]. The Shiv Sena belongs to him. The Sena Bhawan in Dadar belongs to him.”

Shinde and Uddhav had approached the Supreme Court for control of the Sena Bhawan. “That was not right on Shinde’s part,” said Mulik.

Mulik said that in the next Assembly elections in October, 2024, Uddhav will come back to power. Mulik has shown where his sympathies lie.

Mulik said that the public also seemed to have sympathy and affection for Uddhav. A major reason for this was that unlike previous Sena leaders, when he was unseated, Uddhav did not order cadres to unleash violence in the city.

Right on cue, Mulik points out ‘Matoshree’, the house of Bal Thackeray, behind a high wall in Bandra East. Uddhav stays there with his family, said Mulik.

I asked about Jaidev, Uddhav’s elder brother.

Mulik said, “He appeared in a photo with Eknath Shinde and Fadnavis [the former Chief Minister, belonging to the BJP].” This was during the Dussehra rally at the Bandra Kurla Complex on October 5, 2022.

In the thick of Mumbai traffic, we were now moving at a snail’s pace. At Santa Cruz, I paid the fare through Paytm. That’s how I came to know Mulik’s three-word name. We wished each other goodbye. Both of us were certain we would never see one another again.

That’s life but we enjoyed our time together, no matter how brief it was.

March 24, 2023

Permanent regrets

By Shevlin Sebastian

By Shevlin SebastianFor several years, Thomas Sir and I were regulars at a swimming pool in Kochi, be it summer, monsoon or winter. Many people would come, do it for a few days or a week, and then vanish for months together.

A friend explained to me the primary reason they come. The doctor would warn them their health problems will become worse unless they do some exercise. But the motivation declined after a few days.

Thomas Sir, who was in his seventies, when I first met him, would first go to the gym overlooking the pool. He would do quite a few exercises. The one I remember the most was the way he swung his hips in a half-circular motion while standing on a base that moved in a circle. After that, he would ask me if the water was cold. If I said it was too cold, he would go home.

If not, he would step into the pool after the mandatory shower. He did laps in a slow and relaxed manner. Thomas Sir enjoyed swimming. Sometimes, between laps, as we stood at the shallow end, to regain our breath, we would chat. He asked about my family and my work. I did not ask him about his family. Instead, I asked about his career as a land surveyor.

Once he told me, “Being fit is no guarantee for a long life. My brother, who was a good badminton player and played often, died of a sudden heart attack. He was only 71.”

Both of us pondered over what he said before we resumed our laps.

All was going fine, till the corona pandemic struck. Everything went into lockdown. The club closed. Many employees went home. The pool lay untended. The chlorine coagulated, and the water became spoiled.

Thomas Sir had a problem. He missed the adrenal rush he got from doing regular exercise and having a swim in the pool. His muscles became stiff. Thomas Sir’s body lost its rhythm. His mood fell.

Finally, his health declined.

I offset this loss of access to the pool by going for daily evening runs. That kept me going. I got my daily release of dopamine. And it kept my spirits up. But I was younger than Thomas Sir, so I could do that.

After the epidemic, when the pool opened, I did not see Thomas Sir. I asked the pool in charge, who said that Thomas Sir stopped coming. Unfortunately, I did not have the sensitivity or the grace to get in touch with him. I had neither his number nor did I know where Thomas Sir lived. But the pool in-charge told me he stayed near the club. I assumed that because of his advanced age, Thomas Sir stopped coming.

On the evening of March 15, I went for my usual swim. When I returned home, I saw a message on the club WhatsApp group. ‘Senior member Thomas has passed away. You can view his body at his home.’

In fact, as I swam that evening, my regular companion lay unmoving on a bed in his home.

The next morning, an hour before the burial, I went to his house for the first time. It was less than half a kilometre from the club.

The family had placed his body outside on the porch. Thomas Sir lay on a bier under a white sheet, surrounded by white flowers. They put up a golden crucifix behind his head. His face looked peaceful. A priest, in a white cassock, intoned prayers. Several mourners stood nearby.

I saw his wife sitting next to the body.

I remembered Thomas Sir telling me that his wife suffered from knee and back pain. When he said that, I assumed she was overnight. But she looked slim and frail.

A pony-tailed photographer took a group photo of the family, next to the body.

I heard a man standing next to me tell another man, “He is the son.”

By coincidence, the son, in his fifties, came and stood next to me. His eyes were red from crying. I introduced myself and explained how I knew Thomas Sir. He said his name is Austin.

Then I said, “Did Thomas Sir’s health decline because he stopped exercising?”

“Yes,” said Austin. “That was the main reason. He had no health issues before that. But problems began when he could no longer do any exercise. In the end, his heart became too weak, and he passed away.”

It opened my eyes to the possibility of what could happen to me if I could no longer exercise in old age.

Thomas Sir was 86 when he passed away. So, he exercised till he was 83 years of age. That was remarkable.

That evening, I met a senior swimmer at the pool. He told me he had countless conversations with Thomas Sir over the years. “I have a regret that I did not go visit Thomas in his home,” he said. “I could have easily done so after a swim.”

I realised I was not the only person to feel regret.

This is the second time this has happened to me.

I am a member of a public speaking club. The senior-most member was an eloquent speaker and author. But when he grew old, he could no longer come for the meetings. But none of us went to meet him. It was a case of ‘out of sight, out of mind.’ Then, one day, we heard he had passed away. Members went and offered condolences to the wife and children and placed a bouquet near the body.

Later, at another meeting, I mentioned there was a lapse on our part that we did not pay a visit to our senior-most member when he stopped coming. Everybody agreed. But I had clearly not learnt from the regret I felt. Because I behaved in the same manner with Thomas Sir.

These will be regrets I will carry until the end of my life. That’s what death can do to you. You end up with permanent regrets.

I hope and wish I don’t make more lapses like this in the future.