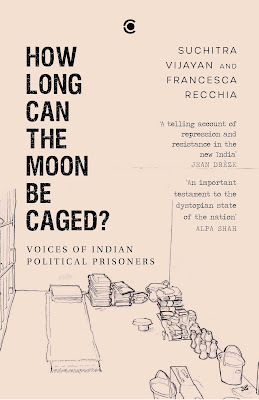

‘How Long Can the Moon Be Caged?’ by Suchitra Vijayan and Francesca Recchia is an examination of how the Indian state stifles dissent

Photos: Authors Suchitra Vijayan and Francesa Recchia

By Shevlin Sebastian

The book, ‘How Long Can the MoonBe Caged?’ (Voices of Indian Political Prisoners) by Suchitra Vijayan andFrancesca Recchia begins with a quote from the book, ‘The Gulag Archipelago’ byRussian literary great Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn:

‘At no time have governmentsbeen moralists.

They never imprisoned people orexecuted them for having done something.

They imprisoned and executedthem to keep them from doing something.’

And the authors prove this inchilling, frightening and alarming detail.

As Vijayan and Recchia stated,‘Political prisoners challenge existing relations of power, question the statusquo, confront authoritarianism and injustice; they stand with thedisenfranchised. Theirs is a ‘thought’ crime: the crime of thinking, acting,speaking, probing, reporting, questioning, demanding rights, defending theirhomes, and, ultimately, exercising citizenship.’

The state’s response: widespreadarrests and incarcerations. Even illegal bulldozing of homes. One of theauthors’ research colleagues, student activist Afreen Fatima’s house in UttarPradesh, was demolished by the authorities on June 10, 2022.

The first chapter, ‘A Season ofArrests’ chronicled in a timeline, from May 9, 2014, to April 17, 2024, themany arrests, temporary releases and rearrests of many activists, poets,fact-checkers, journalists, lawyers, social workers, intellectuals and membersof the Dalit community. It came to 41 pages.

It also chronicled the judicialfight waged by these people, while the government continued to amend laws togive even more unfettered power to the security agencies. Far too many times,the courts have sided with the government.

Incidentally, authors Vijayanand Recchia took the book’s title from a sentence that activist Natasha Narwalsent in a letter from jail. Narwal had been incarcerated for protesting againstthe Citizen Amendment Act (CAA).

In unflinching detail, the bookchronicles the arrest of academician GN Saibaba, who was in a car.‘Plainclothes police from Gadchiroli dragged the driver out, then assaulted,blindfolded and kidnapped Saibaba from the [Delhi] university campus in broaddaylight,’ wrote the authors. ‘No warrant was issued, and he wasn’t allowed tocall his wife or lawyer.’

For those who don’t know,Saibaba is 90 percent physically disabled and needs a wheelchair to movearound. And a district judge, despite scant evidence, did not give him bail.During his first 14 months in prison, Saibaba’s health deteriorated, his lefthand became paralysed and he had to be taken to hospital 27 times.

‘The vast power granted underthe UAPA [Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act] and the regimes of impunity itoffers have fundamentally remade what it means to disagree with the Indianstate,’ wrote Vijayan and Recchia. ‘The UAPA essentially reversed criminal lawby shifting the burden of proof from the prosecution to the defence and makingit illegal to hold certain political beliefs, especially those that questionthe Indian state.’

Tragically, Saibaba joins a longlist of activists and politicians like Binayak Sen, Soni Sori, GaurChakraborty, and Kobad Ghandy, who have been falsely charged under UAPA. Butthe authors state that for every activist whose name is remembered, and theircase reported, hundreds disappear unknown.

Suchitra and Francesca talk atlength about the notorious Bhima Koregaon case, where 16 activists, teachers,intellectuals, university professors, writers, and lawyers were arrested andcharged with arms smuggling, for allegedly helping Maoists, and having a plan tokill Prime Minister Narendra Modi, apart from waging war against the state.

They include Arun Ferreira,Sudha Bharadwaj, Varavara Rao, Vernon Gonsalves, Sudhir Dhawale, Mahesh Raut,Anand Teltumbde, Gautam Navlakha, Hany Babu, Sagar Gorkhe, Ramesh Gaichor,Jyoti Jagtap, Rona Wilson, Surendra Gadling, Shoma Sen, and Fr. StanSwamy.

But the case against them hasbeen flimsy. As the authors write, ‘First, information asserted withoutevidence; second, tampered evidence presented as a fact of complicity. Aforensic report issued by [US-based] Arsenal Computing found that Rona Wilson’scomputer was compromised for over 22 months and the attack was intended for tworeasons: surveillance and planting incriminating documents using Netwire, aremote malware infrastructure.’

The Delhi riots

The authors also focus on thesix-day Delhi riots that began on February 23, 2020. BJP leader Kapil Mishraprovided the impetus by stating that the police should clear the roads withinthree days of protesters against the CAA. Otherwise, he would act.

The riots began soon after.‘Mobs roamed the streets, unchallenged by the police in the days following theriots: an inferno unleashed in the heart of the nation’s capital,’ wrote theauthors. ‘The perpetrators dumped bodies and severed limbs into open drains,and bloated bodies were fished out of the gutter in the aftermath of thepogrom.’

A list of names had beenpublished in the book of those who had died. Out of 53 people, 40 are Muslims,while the rest are Hindus.

In an extraordinary twist, thepolice accused those who were the victims of having inflicted the violence.‘The Delhi police claimed Muslims had targeted their own communities,properties, and people, killed fellow Muslims, and burnt down mosques toprotest a discriminatory act directed towards their communities,’ said Vijayanand Recchia. ‘In one instance, the police arrested an imam for burning down themosque where he used to preach. He had been the one to file a complaint withthe police.’

One of the accused was KhalidSaifi. Once, Saifi’s wife, Nargis, took her eldest son to a court hearing. Whenthe boy saw his father, he reached out to touch his father’s arm. But apoliceman violently pushed the boy away, citing security reasons. The son brokedown. Later, he told his mother, “How can I be a danger to my father?”

Nargis thought, ‘Who is going toanswer this?’

But there is a streak ofsunlight and hope that penetrates this numbing darkness when the authors talkabout ‘a community in resistance’. They write about people who are in the samestruggle to uphold individual and human rights as well as democracy.

And whenever the authors met thefamilies of political prisoners or former prisoners, there was a longdiscussion on the status of other prisoners and their families and their communities.Inadvertently, Vijayan and Recchia became ‘carriers of information in thiswider network of people, who may or may not have met before, but who are nowintimately connected by a shared destiny.’

And the prisoners were gratefulfor the support. From prison, Fr. Swamy (1937-2021) wrote, ‘First of all, Ideeply appreciate the overwhelming solidarity expressed by many people duringthese past 100 days behind bars. At times, news of such solidarity has given meimmense strength and courage, especially when the only thing certain in prisonis uncertainty.’

In the last line of the missive,he said, ‘A caged bird can still sing.’

Once, when Sahba Husain went tomeet her jailed partner, human rights activist Gautam Navlakha, he quoted aline from Canadian singer Leonard Cohen: ‘There is a crack in everything.That’s how the light gets in.’

One of the most moving chaptersis called ‘Small Things’. The authors had asked the families of prisoners andthe prisoners themselves to share objects that were meaningful to them abouttheir experience in jail. These photos are displayed in the book.

For example, Fr FrazerMascarenhas, who was Fr. Swamy’s guardian and official next-of-kin, preservedthe hearing aid that was used by the late activist. There are paintings andphotographs. But the most touching was when Khalid Saifi’s daughter Maryam drewa card for her father, but the guards would not allow Khalid’s wife Nargis toshow it. So Maryam requested Nargis to draw it on her arm, and they took aphoto.

In another section, there arepoignant letters written by the prisoners to family members, to jailsuperintendents, and friends.

This is a heart-breaking book.Most people are not aware of how bad things become when the state moves againstyou when you show dissent. So the authors have to be commended for anextraordinary achievement. Publisher Westland, through the Context imprint,deserves plaudits for having the courage to publish it.

Finally, the authors make atelling statement in the epilogue: ‘The Indian state, with its immense powerand vast resources, was scared of its writers, thinkers, scholars andactivists. Its prisoners stood tall, laughed and sang in the face ofunrelenting assaults.’

(Published in scroll.in)