Shevlin Sebastian's Blog, page 28

March 13, 2020

At home in a different home

The Thiruvananthapuram-based Hindustani classical singer Abhradita Banerjee begins new classes at the Jani Music Academy at Kochi. She talks about her career and her life as a Bengali in Kerala

Photo by Arun Angela

By Shevlin Sebastian

The train from Thiruvananthapuram was late. But it did not spoil the mood of Hindustani classical singer/teacher Abhradita Banerjee. She had a bright smile on her face when she reached the Jani Music Academy at Kochi, which is run by noted Mollywood playback singer Ganesh Sundaram. Abhradita had come to start classes for students in Hindustani classical.

In Thiruvananthapuram, this singer, of Bengali origin, has a music school called ‘Mukthaangan’, which was set up in 2009. But Abhradita came to Kerala 23 years ago. That’s because her husband Dr Moinak Banerjee is a senior scientist at the Rajiv Gandhi Centre for Biotechnology. “It was an arranged marriage,” she says.

So, how do a scientist and an artist get along? “My husband told me right at the beginning of our marriage that we are friends first, then husband and wife,” says Abhradita. “That has worked out very well. We are happy together.”

And she is very happy in Kerala, too. “As a Bengali, I get a lot of respect, maybe because I come from the land of creative geniuses like Rabindranath Tagore and Satyajit Ray,” says Abhradita. “Both states love art and culture. In any house you visit, you will always see the children learning an art form, be it music, dance or painting. Also, apart from a similar climate, both communities like fish a lot.”

Interestingly, Abhradita did not grow up in Bengal. Instead, because of her father’s job in the Railway Mail Service, she grew up in Raipur, the capital of Chhattisgarh.

When her father, Raj Kumar Maitra realised that Abhradita had a talent for singing, he encouraged her. Because he had wanted to be a singer, but due to economic difficulties, he could not pursue his passion. On most evenings Raj Kumar would take her for classes at teacher Sumati Rajimwale’s home. “My father would sit outside and listen intently,” she says. “When we would return home, he would coach me.”

Later, he was able to persuade tabla player Pandit Madan Chouhan, who won the Padma Shri this year, to come to their house twice a week and practice the tabla and teach Abhradita.

The classes went on.

One evening, in 1987, when Abhradita was 13 years old, the guruji did not arrive. Raj Kumar sent a letter through a boy reminding him, but the musician still did not arrive. He felt a bit disappointed. The next morning, he asked Abhradita to sing a particular song by Iqbal Bano. But she said, “Baba, I am running late for class. Will do so in the evening.”

But after class, Abhradita went straight for tuition at a teacher’s house. Suddenly, a visitor came. It was her elder brother. He said, “Baba is ill.” And took her home. Raj Kumar, who had a heart attack, was lying on a bed. “He looked at me, took his last breath and passed away,” says Abhradita. “He was only 54.”

So shocked was Abhradita by this event that she did not sing for an entire year. But when she returned, she won the first Lata Mangeshkar award which was instituted by the Madhya Pradesh government. Some of the other awards she won included the Akashvani Light Music (ghazals) competition, the Centre’s National Music Competition, and the Malayalam Mithra award 2018 given by the World Malayali Council and the Kerala state government. She has also brought out a set of seven songs called Karuna Nidhan, based on Swati Thirunal’s rare Hindi bhajans.

And she sings in many places all over India and on numerous TV channels. “I am happy that I was able to fulfil my father’s dreams,” she says.

(The New Indian Express, Kochi)

Published on March 13, 2020 00:03

March 11, 2020

Of abandoned houses and multiple fences

The Jaffna-based artist Jasmine Nilani Joseph has spent two months at Fort Kochi thanks to a residency of the Kochi Biennale Foundation. She talks about life as an artist in Sri Lanka

Photo by Arun Angela

By Shevlin Sebastian

Jasmine Nilani Joseph sits next to a window in a large hall at Pepper House, at Fort Kochi. On a table in front of her, there are long wooden boxes. “Tamils have a tradition of collecting jewels,” says Jasmine, an artist from Sri Lanka. “Normally, they don’t wear the jewels, which they have. They keep it inside a box, and tell people, ‘I have this much jewellery’.”

Right next to the boxes, using a pen, she has drawn images of abandoned houses with a black pen on white paper. “These houses, like the jewellery, are there as a display, not for use,” says Jasmine, who had come from Jaffna to spend two months at Fort Kochi based on a residency given by the Kochi Muziris Foundation. “So I wanted to connect the two.”

Abandoned houses also raise questions in the mind. “Whose house is this?” says Jasmine. “Who lived here? How was the house in earlier times? Every house has its own story and memories. As an artist, I wanted to document them. I saw similar houses in Fort Kochi, too. One day they will vanish. In Jaffna, I did 30 drawings of these houses.”

Jasmine has experience of abandoned houses. When she was five years old, because of the civil war, the family moved to Vavuniya where she and her family spent three years in a refugee camp. “There were times when we were hungry,” she says. “Money was tight. My father no longer had an income.” Later, the family was able to build a house with the support of the government.

From young, Jasmine was interested in the arts. “As a child, I was fascinated by colours,” she says. So, when she grew older and told her parents she wanted to become an artist, unusually, they agreed. It helped that she was the youngest of two sisters and a brother. So Jasmine was able to do her Bachelor of Fine Arts from the University of Jaffna in 2010. Thereafter, she embarked on her career as an artist.

In 2017, she held an exhibition called ‘Fences’ at Colombo. Throughout her life, she saw fences, made of barbed wires and palmyra leaves, everywhere. “There are cultural and physical fences,” she says. “Whenever I saw a fence I would ask myself, ‘Why do we build fences? Even if two people are best friends, they are separated by a fence. Why is there a barrier?’ When you go through a street in Jaffna, you can see a lot of fences.”

But the fences between the Sinhalese and the Tamils seem to be disintegrating.

“There are a lot of things we have in common,” she says. “When I travel to Colombo, on the train, there are a lot of Sinhala passengers. We sit together and chat about many things. A lot of Sinhalese and Tamil artists are working together. In the universities, classes consist of both Tamil and Sinhalese students. In Sri Lanka today, both the communities are trying to understand each other. People are slowly coming together.”

(The New Indian Express, Kochi and Thiruvananthapuram)

Published on March 11, 2020 01:27

March 9, 2020

The Story of An Iconic Family

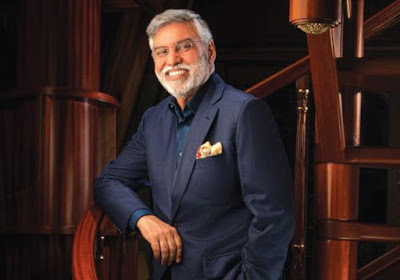

Sunil Kant Munjal, a member of the second generation of the Munjal family, on a recent visit to Kochi, tells the story of how Hero Cycles became one of the great companies of India

By Shevlin Sebastian

Sunil Kant Munjal was supposed to arrive in Kochi at 4.15 p.m. on a recent Wednesday. But at 3.30 pm the information came through that he was in Coimbatore. So, it seemed he would be late. But thanks to a helicopter ride, he was right on time.

The chairman of the Hero Enterprise had come to release the book about their family called ‘The Making Of Hero’ during the annual meeting of the Kerala Management Association. The 221-page book has been published by HarperCollins Publishers and is priced at Rs 699. According to Sachin Sharma, Senior Commissioning Editor of HarperCollins India, who had come to Kochi, it has already scaled up the best-seller charts.

Sunil is the author of this well-written book which traces the history of the Munjal family. They had initially been based in the town of Kamalia in Pakistan but lost everything during the partition of India and Pakistan in 1947. The family settled in Ludhiana and set up Hero Cycles in 1956. In 30 years, it became the largest bicycle company in the world.

And very early in the book, Sunil answers a likely question that might emerge in the mind of the reader. “While my uncles Dayanand and Om Prakash were packing up to move to Ludhiana, one of their suppliers, a Muslim by the name of Kareem Deen, was preparing to shift to Pakistan. He manufactured bicycle saddles under a brand name he had created himself. Before he left, Kareem Deen went to see his friend Om Prakash Munjal.

“What happened next would be a life-changing moment for our family. Uncle Om Prakash asked Kareen Deen whether the Munjals could use the brand name for their business. He agreed….. and so, with nothing more than a casual nod, his brand passed to the Munjals. Yes, dear reader, you guessed correctly, it was ‘Hero’.”

The book is packed with numerous anecdotes and shows the trials and tribulations the family faced before they were able to make a mark.

And they made a mark because it was based on ethical principles. As the former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh said, in the foreword, “Brijmohan Lall Munjal and his brothers belonged to the first generation of entrepreneurs who believed in the credo of learning by doing. They also ran their enterprise like a giant family and prioritised people and profits together in a symbiotic relationship.”

And they had the providential good luck too. In the 1970s, Atlas Cycles was the largest player in the industry. However, there was a labour strike which lasted for a while. And it coincided with the peak season for bicycles. Many Atlas Cycles dealers had to rush to Hero Cycles to procure their supplies. “Once they entered into this relationship with Hero Cycles, they got to experience our way of doing business in terms of fairness, timely supplies, consistent quality and timely payment,” says Sunil. “From this point on, their relationship with Hero became permanent, and this put Hero Cycles on a continuous growth path.”

One of the most important chapters was on how the family restructured the company so that the transition of ownership to the younger generation would be smooth. As Sunil says, “Global research studies, including those by management consultants and research firms, show that 94 per cent of family businesses rarely survive beyond the third generation. In many cases, they tend to implode because of infighting. Only 6 per cent remain intact or make a smooth transition.” And thanks to careful planning and discussions, the Hero Group has managed to stay in the six per cent.

In a way, this book can be a text-book for family firms on how to run a successful business over several decades.

(The New Indian Express, Kochi and Thiruvananthapuram)

Published on March 09, 2020 23:14

March 5, 2020

When a girl gets harassed

Bureaucrat Dr KN Raghavan has written his first novel, ‘A slice of Calicut Halwa’, about the life and times of Rema

Photo by Arun Angela

By Shevlin Sebastian

One day, author KN Raghavan was having a chat with a friend at Kochi. The latter recounted a story. “He told me there was a man Deepak who would stalk his mutual friend Meena and harass her when she was in college,” says Raghavan. “But today, Meena is 50 plus, married and has children. Deepak went abroad and made a lot of money. But recently, he came back and began stalking Meena again, apart from sending non-stop text messages. Stalking has become electronic.”

Raghavan was taken aback when he heard this. “A lot of things happen at the adolescent age which people might not be proud of,” he says. “But they get over it and become mature. But for a certain percentage of the population, these adolescent urges remain.”

Raghavan is not a fiction writer. But suddenly a plot came to his mind, on the lines of what happened to Meena. So, even though he felt apprehensive, he decided to make an attempt to write a novel. So, every morning he would write. And surprisingly for him, it flowed easily. At the end of two months, he had a novel. This has just been published as ‘A slice of Calicut Halwa’ by Zorba Books and is priced at Rs 225. It is available on Amazon, Flipkart, Shopclues and Snapdeal.

The story is set in Calicut Medical College where Raghavan had himself studied. Rema is a brilliant young girl who begins to get harassed by a young man from the law college. Her confidence and self-esteem get affected. But life goes on. Rema gets married to a lawyer, who happens to be a closet homosexual. She feels trapped. And, later, the law student resumes harassing her. The twists and turns from these developments form the core of the novel.

Asked the difference between fiction and non-fiction, Raghavan says, “Fiction means you just go inside your head. For non-fiction, you have to do a lot of research. You have to chronicle details in a systematic manner. When you write a chapter, you have to give your references. It’s time-consuming. But since I enjoy doing it, this is a welcome experience.”

Raghavan has published three non-fiction books thus far. In 1999, he wrote ‘World Cup Chronicle’. In 2012, he published ‘Dividing Lines: Contours of India-China Conflict’ and in 2016, he came out with ‘Vanishing Shangri La: History of Tibet and Dalai Lamas in the Twentieth century’.

As to whether reading has declined, Raghavan nods and says, “The number of bookshops in Kochi have gone down. There was a beautiful bookstore in the Oberon Mall which has sadly closed down. The number of people who go to libraries is becoming less. As for the avid readers, they have moved from print to digital.”

Raghavan’s only child Aishwarya, who lives in Sweden, swears by the Kindle. She had urged her father to buy one but he prefers the charm of holding a physical book in his hands.

A career bureaucrat, Raghavan was Commissioner of Customs (2012-2017) in Kochi as well as Principal Commissioner of Central GST in Mumbai from 2017-19. Today, he is the Kottayam-based Executive Director of the Rubber Board of India.

“Kerala is almost saturated,” he says. “There is no land to grow more rubber. So we are trying to develop plantations in Tripura, Assam and Meghalaya. I travel to these places once a month to oversee the work. I am also looking at non-traditional areas like Orissa and Andhra Pradesh.”

He agrees it is a tough time for rubber growers. “That’s because international prices are very low,” he says.

Meanwhile, when asked about his future plans as a writer, Raghavan says, “I am toying with the idea of writing about the decline of the Left and why it is vanishing from India.”

Published on March 05, 2020 22:06

March 4, 2020

Seeing beauty in ordinary things

The Adelaide-based artist Jane Skeer spent a month at Fort Kochi and produced unique installation art from waste materials. She talks about her experiences

Pics: By Arun Angela

By Shevlin Sebastian

As the Adelaide-based artist Jane Skeer was talking about her works to a group of young visitors at the Pepper House, Fort Kochi, tears began to roll down her face. She quickly took a handkerchief and dabbed at her face. “I am so sorry,” she says. “I feel so sad that I will be leaving Kochi within a couple of days and returning home.”

Jane had come for one month on a Kochi Biennale Foundation-Adelaide Residency Exchange. While one artist comes from there, an Indian artist will go and spend a month there.

For Jane, this is her first visit to Fort Kochi. And she is smitten. “I am taken up by the culture, history and people,” she says. “I spent three to four hours walking around every day, talking to people and taking photographs. What I am most impressed with is the people’s love for family and country. You’ve got it all together so much better than we have in Australia.”

She says that there is hardly any colour in Australia. “Our construction is all about cement and steel,” she says. “We make straight and massive structures. Our architecture has no personality. You come to Fort Kochi and it is colourful, vibrant and beautiful. I don’t see anything ugly.”

Jane’s forte is in installation art. In her temporary studio at Pepper House, she has stacked discarded blue cement bags in a triangle at one side of the hall. It is in striking contrast to the red walls all around.

She had seen the bags on the roadside while walking around. “I thought it was interesting, the way the light was falling on them,” says Jane. Then she noticed that plants were grown in them and placed on top of fences. “There are so many different uses for it,” she says. “It seemed like vessels. And when I looked out through the window at Pepper House, at the backwaters, I saw a boat, another type of vessel, carrying goods and services.”

In the next room, she again used the discarded sacks and placed them in three different rows, of thirty sacks each, but containing the colours of saffron, white and green. “This is my version of the national flag of India,” she says, with a smile.

While standing on the seashore, she noticed that small terracotta stones had floated in from the river. She quickly collected several and made a circular design on the floor of her studio. It gave an impression of being part of an ancient culture.

On the walls, Jane had put up several photographs. Ordinary sights became extraordinary through her camera lens. So, an image of several red Indane gas cylinders, stacked up, with a chain going through them all, becomes, in Jane’s eyes, “An art installation. I love the way they have been stacked, the beautiful markings on it, which indicates its history. Each gas cylinder stands for a person, home or business.”

Jane is a late bloomer. It was only at the age of 47, this mother of two boys and two girls, who are all in their twenties and thirties, went to the Adelaide Central School of Art and said, “I think I can paint.” But to gain entry, she also had to do a sculpture course. And right from the beginning, she became a natural at sculpting.

“I found my passion and now I just can't stop,” she says. Every year, since 2015, she has been holding several exhibitions of her installation art. And in her spare time, she writes poetry, too.

Here are a few lines:

‘All the answers I need Are inside me.

All the love I need Is inside me.

All the happiness I desire Is within me.

I have it all.

I don’t need anybody at all.’

Does that mean she does not need her husband, a businessman, whom Jane had been helping in his work? She laughs and says, “Who knows? I am growing wings. I might just fly away. Or we may become closer. Who can say what will happen?”

(The New Indian Express, Kochi and Thiruvananthapuram)

Published on March 04, 2020 23:13

March 3, 2020

All at sea

Manoj Joy, the new managing director of the Sailors’ Welfare Association, talks about the problems faced by the seafarers and the remedies that are taken

Photo by R. Satish Babu

By Shevlin Sebastian

One night at Pathanapuram in Kollam, Devayani Nair woke up with a scream. Her husband, Prabhakaran Nair, an ex-serviceman, said, “What has happened?”

She replied, “Praveen (son) is in some problem.”

Prabhakaran calmed her down by saying it was a dream.

But the next morning, Praveen called up and said, “Somali pirates have taken control of our ship.” The moment Devayani heard this, she said “Aiyyo” and lost her mental equilibrium.

Praveen had been just five days into his career as a cadet on the Iranian ship MV Amin Darya. There were two Indians apart from six Pakistanis who comprised the crew.

A ransom was paid and the ship was freed. But when the ship reached the port of Mombasa in Kenya, the security forces raided it and confiscated eight kgs of heroin worth $12 million. The captain and crew were arrested. Soon, Prabhakaran got in touch with Manoj Joy of the Sailors’ Welfare Association (SWA) to ask for his help. Manoj agreed, but it would take all of three years, and the tireless efforts of the Malayalee Samajam in Mombasa before Praveen was freed.

“Praveen’s mother never recovered. Two years ago, she died, less than 50 years of age,” says Manoj, who, on October 18, 2018 won the Safety at Sea's prestigious International Award in the ‘Unsung Hero’ category held at Mayfair, London. And in August, 2019, he became the managing director of SWA.

But today, he is busy keeping track of the spread of coronavirus, in case it affects Indian sailors. He would want to render all help to the families. There was an alarm recently when seven Sri Lankan sailors were quarantined at Colombo because they had fallen ill. They were working on a French operated container ship which had travelled from China to Egypt. However, tests confirmed they were in the clear.

Meanwhile, in Chennai, the SWA, which is part of the 201-year-old Sailor Society in the UK, is running a free medical project for retired seafarers who are having economic problems. “Our ambulance picks up the patients at designated points,” says Manoj. “SWA is tied up with one of the finest hospitals in Chennai known as the Voluntary Health Services Hospital. The treatment and medicines provided are free.”

In Kasaragod, where there are 3000 sailors, SWA is setting up a vehicle that can ferry retired seafarers and their family members to a hospital in Mangalore. The society repaired a seafarer’s house in Chennai, last year, which was leaking. The funds came from contributions made by shipping companies.

Sometime ago, the Chennai-based Manoj, who has spent 18 years at sea, went to Kothamangalam in Kerala to attend the wedding of the daughter of the missing seafarer Jose Mathew Katampally.

Jose was an engineer on the tug Jupiter VI. On September 5, 2005, the tug went missing as it was towing a ship, ‘Satsang’, from Walvis Bay in Namibia to a ship-breaking yard in Alang, Gujarat. “Nobody knows what happened to the ship and crew,” says Manoj. “The family received a compensation of Rs 25 lakh.” In established international companies, the compensation given is Rs 70 lakh.

Sadly, life is not easy for seafarers. In earlier days after duty, the men would assemble in the mess hall and have a drink and enjoy some camaraderie with each other. “Now they are all isolated in their cabins with their mobile phones,” says Manoj. “They are sending Whatsapp messages all the time. Some get depressed when they get news from home. So, in despair, they throw themselves into the sea.”

In the past, sailors would have longer port stays. They would mingle with the people and enjoy the local cuisine. “Today, thanks to technology and mechanisation, the turnaround at a port is much faster,” says Manoj. “Also, because of security concerns, most of the ports don’t allow the sailors to embark. In places like Iran, you should get back to the port within six hours. In Indian ports, you can go outside but by 8 p.m. you have to be back on the ship.”

The scenario changed when America was attacked during 9/11. “The Americans tightened security at all their ports and thereafter many countries followed suit,” says Manoj.

And cadets are not much valued, because there is a surplus. For the training, they end up spending about Rs 8 to 10 lakh. To pay the fees, they take bank loans by mortgaging their property. “Some of them are hell-bent on going to the sea,” says Manoj. “If I am a cadet, then to become an officer I have to spend 18 months at sea. So they get into any ship they can.”

As a result, many cadets work on ships which are run by fly-by-night operators. Some of the sailors are abandoned at foreign ports without being paid, or stranded at sea without food and wages. “So we have to help to bring them back,” says Manoj. “And when they die, the fly-by-night operators do not take the responsibility of sending the body back or pay the compensation. The SWA is trying to help these distressed sailors to get justice.”

Finally, Manoj says, “Despite all these problems, working on a ship can be a fun experience. But it is very important that you are employed by a reputed company.”

Published on March 03, 2020 23:44

March 2, 2020

Aussies, here we come

Two artists, Sabyasachi Bhattacharjee and Sunil KR will be taking part in a residency programme in Australia organised by the Kochi Biennale Foundation and the Adelaide Residency Exchange

Photo: Sabyasachi Bhattacharjee and Sunil KR. Photo by Arun Angela

By Shevlin Sebastian

It is a hot February afternoon. But on the first floor of Pepper House, the humidity is not affecting Sabyasachi Bhattacharjee, a young Tripura artist who is now based in Baroda. On a piece of cloth hanging from the ceiling, he is tracing an image. Sabyasachi is doing this in 10 feet sections. The total length will be around 100 feet.

He is looking at the marine algae phytoplankton. “The algae drift about on the surface of the ocean but it is also one of the most important sources of oxygen on the planet,” says Sabyasachi. “Because of photosynthesis, it converts carbon dioxide into oxygen and is an important cog in the aquatic food web .”

Along with the plant’s drift, Sabyasachi is also looking at the human drift or migration that is happening all over the world. “I am trying to compare both and seeing how it will work out,” he says. “But every ten feet of my installation, the landscape will change, just as it happens in real life when after 10 km the language can change and become a sub-language.”

Sabyasachi is hoping to hold a residency show parallel to the next edition of the Kochi Muziris Biennale which commences on December 12, 2020.

The young artist is on a two-month residency, since January, from the Kochi Biennale Foundation (KBF). But on March 17, he will be jetting off to Adelaide where he will spend one month on a KBF-Adelaide Residency Exchange. “I am hoping that when I look at my homeland from that far-off place I will get a different perspective.”

This is his second visit abroad. In 2018, Sabyasachi went to take part in an Art Asia fair in South Korea.

Meanwhile, for Sabyasachi, Fort Kochi is a familiar place. In an earlier Biennale, he had spent two months working as an assistant to the artists. “Fort Kochi feels like home now,” he says. But the focus on his art remains constant. He comes in at 11 am and works till 7 p.m. “This is something I love to do,” he says. “I am a full-time artist now.”

Like him, senior photographer KR Sunil is a full-time artist. He has been a featured artist at the Kochi Muziris Biennale of 2016. Some of his subjects include the dhow workers of Malabar, and the town of Mattancherry with its myriad identities that includes the Jews, Kutchi Muslims and Anglo Indians. He has also focused on the folk ritual called Bharani when devotees assemble in large numbers at a temple in Kodungallur and use harsh words to appease the goddess.

Once Sabyasachi returns, it will be Sunil’s turn to go to Adelaide. And Sunil is excited. “It is my first trip abroad,” he says. And he is already researching the possible subjects he can focus upon. “There are some old houses in Adelaide,” he says. “I might want to take photos of that.” He says he might look at the seafarers of Australia. And at the end of his stay, he is planning an audio-visual presentation, apart from a one-day Open Studio.

“The exposure will be enriching,” says Sunil.

(The New Indian Express, Kochi)

Published on March 02, 2020 01:16

February 27, 2020

Nature Vs Development

Senior artist N Balamuralikrishnan’s painting exhibition, ‘Memoirs of Onattukara’ is a thought-provoking one

Photos: N. Balamuralikrishnan. Paddy fields. A telecom tower. Pics by Arun Angela

By Shevlin Sebastian

As one stepped into the ‘Memoirs of Onattukara’ exhibition by artist N Balamuralikrishnan, at the Durbar Hall Gallery, Kochi, a large canvas catches the eye. It is almost like a drone’s eye view of several green paddy fields stretching out in the distance with green parrots flying above it, along with a white swan. In front, are several golden sheaves of paddy. It brings a moment of tranquillity as one stares at it. But immediately next to this 14’x 4’ acrylic on canvas is an image of a hill seen between the bars of a telecom tower. And that sets the tone for the exhibition.

On the opposite side, on a large black-and-white canvas, a lorry is dumping waste on a patch of land. But when you look closely at the garbage, you can see an owl, rabbit, tortoise, mouse, frog, snail, beetle, and a mouse trapped in it. In another image, a paddy field next to a railway line is filled with pieces of stone.

“My hometown of Onattukara has changed,” says Balamuralikrishnan. “In the name of development, forests and paddy fields have been flattened. Buildings have come up. Telecom towers have been installed in sacred groves. This has spoilt the harmony of the place. Money has been coming from the Malayalis living in the Gulf and is causing rapid changes.”

Balamuralikrishnan had created an image of a man carrying large plastic materials like buckets, mugs, brooms, ladles, pots and chairs on a bicycle. “The arrival of plastic has also caused a lot of damage,” he says.

For several years Balamuralikrishnan had been an art teacher in a government school in Kannur. But in 2013, after taking voluntary retirement, he returned to his hometown and was able to observe the changes first-hand.

He also focused a bit on history. In one image, the head of a statue of Lord Buddha, with a topknot, can be seen nose-deep inside a lake. At the side, broken columns are lying about, with grass growing over it.

The Hindu sage and reformer Chattampi Swamikal (1853-1924) while visiting Mavelikara saw women washing clothes by hitting the stone of a statue which was three-quarters below the surface of a river. Sensing there was something more, with the help of the local people, Chattampi was able to bring up the statue of Lord Buddha. And today, it has been put in a place of prominence.

In the eight century, the Onattukara area was a flourishing centre for Buddhist culture. Many villages and towns had names ending in Palli, which was common in Pali, the language of Theravada Buddhism. But soon Hinduism reasserted itself. As a consequence, Buddhism faded away.

Meanwhile, on one side, Balamuralikrishnan has done several small charcoal drawings within the frame of a canvas. In one, a bare-bodied man, with palms upraised, near his face was shouting “Hoi Hoi”, to warn lower-caste people to stay away. Behind him was a horse-drawn carriage, which had an upper-caste passenger. When they went past a school, social reformer TK Madhavan, who was a child then, mimicked the sound of “Hoi, Hoi.”

The carriage moved on. After several hours, two men came to find out who had shouted. The children and teachers remained silent. But Madhavan confessed and was beaten up.

“It was a time when workers also had to hide when a member of the upper caste walked on the road,” says Balamuralikrishnan.

But there was a path to freedom. Another image showed a tall, bearded Christian priest, in a white cassock, arms upraised, while on the ground in front of him sat several downtrodden people. “Because of the priest’s help the lower castes were able to get access to education and by adopting Christianity they could walk anywhere,” says Balamuralikrishnan.

Other images include members of the Communist Party holding aloft their hammer and sickle flags, as they took out a demonstration, a boat on a river and an autorickshaw, with a loudspeaker on top, announcing a death.

All in all, this senior artist’s exhibition, comprising 21 works, is a thought-provoking one.

(The New Indian Express, Kochi)

Published on February 27, 2020 22:42

February 25, 2020

Getting high on the high notes

Singer Sanah Moidutty came to Kochi to record a song for a Malayalam film. She talks about her life and experiences

By Shevlin Sebastian

Last week, singer Sanah Moidutty came to Kochi to record a Malayalam song by composer Prakash Alex for the film 'Varayan'. It is a soulful song with beautiful lyrics, she says. The recording was over in less than a day. And thereafter Sanah relaxed a bit. “It is always good to come to Kerala,” says the Mumbai-based singer, whose father belongs to Pattambi, while her mother is from Areekode.

She says she is the typical ‘outsider’ Malayali. She can speak Malayalam but is unable to read and write it.

In Kerala, Sanah enjoys the food and the greenery. “The traffic jams are much less, as compared to Mumbai, where we can be stuck for hours on the road,” she says. “I also get a chance to breathe fresh air, although, in Mumbai, I stay near the Sanjay Gandhi National Park in Borivali, which is one of the few major national parks in the world within city limits.”

These days, Sanah is practising as hard as ever. She admits that the competition in Bollywood is very intense. “There are many talented singers around,” she says.

She has a dedicated YouTube channel where she does covers of hit songs, but sometimes, adds her innovations. For the classic Malayalam song, ‘Karuthe Penne’ from ‘Thenmavin Kombath’ (1994), she added a rap section in English and Malayalam.

Sanah made her name with the songs, ‘Tu Hai’ and ‘Sindhu Maa’ that she sang for AR Rahman for the film, ‘Mohenjo Daro’ (2016). And this happened through her own initiative. She had sung a song on her channel and, at the suggestion of her manager Ben Thomas, she sent the link to Rahman. The latter appeared to have heard it, and kept it in his mind. Because Rahman called her after two years to give her a chance in ‘Mohenjodaro’.

Asked to give her impressions of the two-time Oscar winner, Sanah says, “When Rahman Sir calls someone, he believes in that person’s talent. So, he will present something to the singer and say, ‘Make this beautiful.’ He gives a lot of freedom to the singer. Rahman Sir is always in a creative ferment. He comes up with new ideas all the time. You have to be on your toes.”

Sanah has been on the toes since the age of seven. That was when she joined the children's troupe ‘Bacchon Ki Duniya’ and performed in over 500 stage concerts in many cities of India. “It helped develop my self-confidence,” says Sanah, whose mother, a home-maker, had accompanied her to every show. “I am a different person on stage -- lively and outgoing. There is a subconscious switch-on. However, off stage, I am quiet and don’t speak much.”

Instead, this graduate of a computer engineering course reads a lot. The latest book that she is reading is the bestseller ‘Daring Greatly’ by Brene Brown. “Brene says that being vulnerable enables you to be successful in life,” says Sanah.

The highlight of Sanah’s career was when she took part in the ‘Star of Asia’ international festival at Almaty, Kazakhstan in September, 2017. There were bands from all over Asia, each representing their country. “My band and I were representing India,” says Sanah.

Following suggestions from the organisers, Sanah sang old retro songs like ‘Jimmy Jimmy aaja aaja’, and ‘I am a disco dancer’, both from Mithun Chakraborty’s films. The young men began shouting and tapping their feet, while the girls smiled and waved their hand fans vigorously. “They were having so much fun,” says Sanah. “The people of Kazakhstan are big fans of Bollywood. That’s when I realised music has no boundaries.”

Meanwhile, Sanah, who is trained in Carnatic and Hindustani music, ensures that her voice is in good fettle. Every morning, she does a riyaaz for one-and-a-half hours. “Regular practice is very important,” says Sanah, who has sung for ‘Always Kabhi Kabhi’, ‘Gori Tere Pyaar Mein’, ‘The attacks of 26/11’, ‘24’, ‘Meri Pyaari Bindu’ and ‘India’s Most Wanted’.

(The New Indian Express, Kochi and Thiruvananthapuram)

Published on February 25, 2020 22:35

February 21, 2020

Remembrance of things past

Four Malayalis, who worked for decades at the Bhilai Steel Plant, and live there, visited Kerala to meet their old friends. A story about their experiences

Pics: From left: PRN Pillai, N. Ramadasan (red T-shirt), MNC Pillai (in front) and GVK Nair; a Bhilai group settled in Thrissur

By Shevlin Sebastian

Once a month, four veterans -- PRN Pillai, N Ramadasan, MNC Pillai and GVK Nair --- meet at each other’s home in Bhilai. They play cards or talk about politics or reminisce about their long careers at the Bhilai Steel Plant (BSP).

One day, Ramadasan said, “I wonder how our ex-colleagues are doing in Kerala. Maybe, we should go and visit them.”

The others mulled over what Ramadasan said. Then they decided it was a good idea. There are about 300 families now settled in Kerala. So, on one fine late January day, they set out on the Korba-Thiruvananthapuram Express.

When they reached Palakkad a couple of days later, at 9.30 a.m., two friends received them. One of them was Padmanabhan who worked in the accounts department of BSP. They freshened up at his home, met Padmanabhan’s wife, children and grandchildren, and proceeded to the house of another friend Balasubramaniam. “Then these two friends accompanied us as we met all our old friends in Palakkad,” says Pillai. “One of our colleagues had died, so we went and met his wife.”

For the next one week, they met people at Thuravoor, Vaikom, Kottayam, Thiruvalla, Chengannur, Mavelikara, Pandalam, Pathanamthitta, Adoor, Kottiyam, Karunagapally, Kollam, and Thiruvananthapuram.

In Thiruvananthapuram, journalist Anil Philip met them. His late father KV Philip had worked in BSP for 42 years. “With the help of Anil we were able to meet many families in Thiruvananthapuram,” says Pillai. “Earlier, he took us to meet his mother Leeelamma at their ancestral home near Chengannur.”

At most of the places, people remembered their life in Bhilai and shared unforgettable anecdotes with the quartet. And everybody agreed that Bhilai had a charm of its own.

“It is a well-planned city, which was designed by the Russians,” says Pillai. “So there are wide streets and plenty of greenery.” The steel plant was set up on February 4, 1959, during the premiership of Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru. At that time, the plant had an employee strength of 55,000. “There were more than 5000 Malayalis who were employed,” says Pillai. “Now the staff strength is 30,000.” Interestingly, very few of the succeeding generations of Malayalis are employed at the plant. “Many have gone abroad,” says Pillai.

Meanwhile, in Kerala, Pillai and the others were surprised to hear that most yearned for their life in Bhilai. “They said that they missed the close friendships,” says Pillai. “In Kerala, they told us, there is no concept of visiting each other just like that. People meet only during weddings, birthdays, funerals and other such functions. In Bhilai, it is just the opposite. So, we are very close to each other. Leelamma is sad that they had left Bhilai. She felt happier there.”

Of course, one reason for the lack of friendships is because the mental wavelength is different. “When you have lived 40 years away from Kerala, you will think differently to the people here,” says Pillai.

In fact, a few families returned to Bhilai because they did not like it in Kerala. “They felt out of place, so they came back,” he says. “They told us, ‘Don’t make the mistake we made’.” Pillai remained in Bhilai because he is a widower. “I know that if I have any problem, my friends will be there to help me,” he said. “Because of their presence, I feel less lonely.”

In the end, the group managed to meet 75 families and travelled 750 kms across the state.

And barely a week after they returned, they received the sad news that KV Nair who lived in Cheriyanad, near Mavelikara had passed away. “He had come and met us,” says Pillai “Nair was around 75 and was in good health. He had gone to the Mavelikara General Hospital to get a certificate for his daughter, had a sudden heart attack, collapsed and died.”

The group was grateful they were able to meet Nair. “We are all in our seventies and eighties, so time is running out for all of us,” says Pillai. “We are glad we were able to make this journey."

Published on February 21, 2020 22:42