Shevlin Sebastian's Blog, page 30

January 29, 2020

Indian students at Wuhan University to be evacuated within two days

By Shevlin Sebastian

Photo: Faizal Nazar

On Wednesday morning, Faizal Nazar, a fifth-year medical student at Wuhan University School of Medicine got a call from the Indian Embassy in Beijing. The Karunagappally native was asked to send the details of the 56 Indian students who are still at the university. Faizal quickly did so. The embassy wants to evacuate the students as quickly as possible. “There is a chance we might leave by Thursday afternoon,” says Faizal. “But nothing is confirmed yet. The embassy people told me a Boeing 747 is getting prepared.”

All the students are feeling scared and nervous. And they have ensured they have not stepped out of the 20-acre campus at all. But they are all grateful to the Chinese government. The university, which is government-run is providing free meals at all times. “They are trying their best,” says Faizal.

He says the students were amazed that the government built a 1000 bed hospital in six days at Wuhan. “We cannot imagine a hospital being built so fast in India,” says Faizal. “The reason is that they want to place all the coronavirus patients in one place. Otherwise, there is a risk of the virus mutating.”

The university has announced that classes will begin only on March 1. But Faizal feels that this break will last till April. “It is a grave crisis,” he says.

(The New Indian Express, Kerala editions)

Published on January 29, 2020 21:39

Use and eat it

Dr Suchitra R is trying to spread the awareness of edible spoons

By Shevlin Sebastian

One day, after doing a Lasik eye operation, at a centre in Kochi, ophthalmologist Dr Suchitra R took a tea break. As she read through the newspaper, she came to know that the Kerala government had announced the ban of single-use plastic. Suchitra felt that she should do something to find an alternative. In her spare time, she began to do research on the Net. And then she came across a company in Gujarat that makes edible spoons. That is, these are spoons you can use and eat afterwards.

She wrote to the company. They sent her Food Safety certificates. Convinced that they are genuine, she began ordering the products.

At her home in Vennala, she showed a variety of table and dessert spoons. “Table spoons come in many flavours like classic salt, black pepper, peri peri which is chilly-based and the chocolate-based dessert spoon,” she says. All of them have individual paper wrappers.

And they are made of oats, corn, chickpeas, wheat and rice flour. “The spoons have a short life because there are no preservatives,” says Suchithra. “And having used it, I can say that it does not crumble. And there is no waste since we are eating them.”

Suchitra is going around and talking to her friends and relatives. And she gives apt examples. “Suppose you are holding a birthday for 30 children,” she says. “A lot of plastic cups and spoons are used. I tell parents they can start by replacing spoons. And they are receptive. The children like chocolate spoons. So I am happy about that.”

The ophthalmologist is also meeting event planners to urge them to avoid using plastic spoons for large events like weddings and birthday parties. Some have promised Suchitra that they will switch to edible spoons.

With the help of her husband Dr Satish Bhat S, she wants to create a market for these spoons. “It is not about profits but my way of doing something for the environment,” says Suchitra.

Satish also spoke about it on his YouTube channel and ate a couple of spoons -- peppercorn and chocolate -- on camera. “There was a good response,” he says. “Many people wanted these spoons.” Viewer Radhakrishnan Vadakkepat says, “This should be used in every eatery.”

Suchitra believes that in Kerala, there will be a market, more in the urban rather than rural areas.

But the couple is happy there is an ecological awareness among people now. “They know that plastic is no longer good for the environment,” says Satish. “In the clinic that I am running, there are seven staff members. Earlier, when they would order from online food apps, it would come with plastic straws and cups. Now, they take the option of ‘no plastic cutlery’.”

Suchitra says, “Edible spoons is an easy solution for these apps.”

Published on January 29, 2020 21:36

January 27, 2020

Unity in diversity

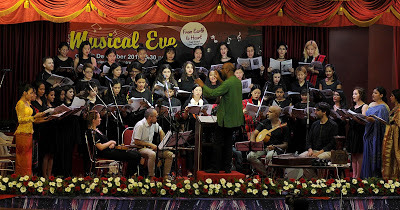

The choir of the Asian University for Women, representing 14 countries, sang a wide variety of Asian and European songs. It has helped the women to develop their talents and self-confidence

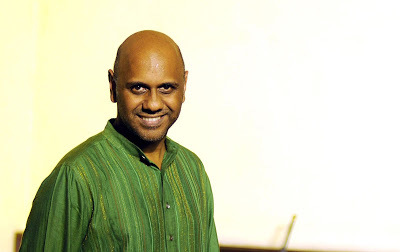

Pics: The choir of the Asian University for Women; Dr. Selvam Thorez. Photos by A. Sanesh

By Shevlin Sebastian

At the Pastoral Orientation Centre in Kochi, a 40 member all-women choir sings, ‘Give me the nay (flute) and sing/ for singing is the secret of existence/And the sound of the nay remains/After the end of existence.’

This is an English translation of a Lebanese song, ‘Aatini al nay’ (Give me the flute), which had been sung by one of West Asia’s greatest singers Fairuz. And the audience laps it up. All the women on stage are dressed in black. In front of them are French musicians Camille Aubret, Martin Bauer, Jean-Luc Tamby, Stephane Tamby and Keyvan Chemirani, who are playing the baroque guitar, flute, bassoon, and percussion instruments. And standing on a stool and directing the choir is the Pondicherry-born Frenchman Dr Selvam Thorez, who is Director of the Alliance Française in Chittagong, Bangladesh.

The singers belong to the Chittagong-based Asian University for Women (AUW). And they belong to four religions, Hindu Muslim, Christian, and Buddhist, and come from 14 countries: Bangladesh, Myanmar, Nepal, Afghanistan, Bhutan, Sri Lanka, Cambodia, Syria, Indonesia, China, America, Vietnam, Pakistan and India.

India is represented by Mercy Kikon from Nagaland. “It is a privilege for me to sing on behalf of my country,” she says. Later, the choir sings a Naga song called Zayele (Protect us). This is a Gospel song, says Mercy. In fact, because of the Christmas season, most of the songs are spiritual ones. But it is a mix of Eastern as well as French baroque music from the 16th to the 18th centuries. Interestingly, the Bangladeshi singers opt for a Rabindranath Tagore song, ‘Anondodhara’. There are songs from Syria and Cambodia, too. The concert, ‘Earth to Heart’, with performances at Delhi, Pune, Kolkata, Hyderabad, Thiruvananthapuram and Kochi (on December 19) had been arranged by the Alliance Française de Trivandrum in association with Alliance Française de Chittagong and the Kochi-based Chavara Culture Centre, along with the French embassies in Delhi and Dhaka.

Conductor Selvam, who trains the choir three times a week, says that the girls were selected through a stringent test. Out of 80 applicants, only 20 were selected. When asked about his job, Selvam says, “A good conductor should be friendly, kind and as helpful as possible, to give the proper direction and provide meaning for the song. I try to give freedom to the singer to express herself. so that they can get better.”

Interestingly, all of them come from poor and lower middle-class families in small towns and cities across Asia. “They are all studying on scholarships provided by the AUW,” says Selvam. “We want to give opportunities to the disadvantaged. There are a few Rohingya girls, too.”

Says Cherie Blair, University Chancellor and former UK First Lady: “At a time when there is so much strife in the world based on our inherited identities, AUW shows that yet another world is possible where young women from different upbringings can come together – first in solidarity with each other, and secondly in supporting a wider vision of changing their communities together.”

Sidrah, a Muslim, who comes from Pakistan shares a room with a Bhutanese, who is Buddhist. “When we are together we forget about our stress and have fun,” she says. “We teach each other about our religions and cultural traditions, and we respect each other.”

The AUW is funded by entrepreneurs Jack and Beth Myer, who has given $10 million, as well as the Ikea Foundation, which has given a similar amount, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation which has given $5 million, apart from 45 other foundations and individuals.

Meanwhile, Naga singer Mercy is enjoying herself in Kochi. “This is my first visit to South India,” she says. “I like the food -- rice, sambhar, and uttapam, the culture, and the ambience. The people are very kind and hospitable..”

The choir is now getting ready for a tour of Myanmar in February, this time with a repertoire of popular songs and baroque Italian music.

(Sunday Magazine, The New Indian Express, South India editions and Delhi)

Published on January 27, 2020 23:03

January 25, 2020

Malayalee residents in Beijing feel tense as cases increase

CORONAVIRUS OUTBREAK Pic: Suresh Varma and his family during happier timesBy Shevlin Sebastian On most mornings, these days, when entrepreneur Suresh Varma wakes up at his home in Beijing and checks his mobile phone, he is sure to see three messages. They are from the Indian Embassy, the local municipality and mobile service providers. They all have one plea: about the need to take precautions ever since the fatal coronavirus erupted in Wuhan, which is 1150 km from Beijing on December 31. So, Suresh is told, like lakhs of Beijing residents that he should wear facemasks if he is planning to go out especially towards crowded places, and drink water all the time.The virus thrives if the throat is dry,” says Suresh, by phone from Beijing. “There is a need to keep the throat hydrated all the time. So, we are told to carry water bottles all the time.”There are about 40 Malayalee families in Beijing, for a total of 120 people. They are mostly working for multinational firms, banks, newspapers, schools as well as embassy staffers. At Wuhan University, there are a few Malayalee students. “But till now, it looks like not a single Malayalee has been infected,” says Suresh, who is the president of the Beijing Malayalees Association. “As you know, Wuhan and four other towns (total population: 22 million) have been locked down. No one can go in and no one can come out. The railways and the airports are closed. It is a tense situation. But the government is on a war footing.”But the odds are stacked against them. One major reason is the timing of the outbreak. On January 25th is the Chinese New Year. One week before, all offices had closed. Schools were shut two weeks earlier. “What is going on in China is a mass internal migration,” says Danny Geevarghese, a Beijing-based freelance writer. “Millions of people are travelling back to their hometowns.”So, it is no surprise that cases have been reported in 27 provinces, with 41 deaths so far. And numerous people have already travelled abroad for vacations. So nobody knows who has taken the virus outside.Cases have already been reported in Taiwan, USA, South Korea, Thailand and Japan.To prevent further outbreaks, at Beijing airport, the authorities have put up large temperature-scanners. “You just walk past the scanners,” says Suresh. “If you have a slight temperature, they will take you aside and check you.”As to whether there are fears in China of this becoming a national as well as a global epidemic, Suresh says, “They are hoping it is not. Scientists worldwide are working very hard to discover a vaccine. Let’s hope they make a breakthrough quickly.”(The New Indian Express, Kerala editions)

Published on January 25, 2020 04:32

January 20, 2020

The world of ghosts

Veteran Mollywood director Suresh Unnithan is putting the final touches to his film, ‘Kshanam’, which will be released next month

Pics: Suresh Unnithan. Photo by BP Deepu; Anu Sonara

By Shevlin Sebastian

At the Film Employees Federation of Kerala office at Kochi, director Suresh Unnithan met scriptwriter Sreekumar Arookutty who said, “Sir, I want to narrate a story to you.”

So they stepped to one side. And Sreekumar quickly narrated the gist. It is the story of two girls. One girl has been murdered but she had always wanted to live. The other does not want to live, moves around with a petrol can, and wants to kill herself. “The first one is a ghost,” says Suresh. “The other girl lives in the present.”

Suresh was intrigued. He believes in spirits, ghosts and the afterlife. That’s because he had a personal experience. A few years ago, when he was going through a bad time, his mother appeared in a dream and told him, “You will get work. Don’t worry.”

This turned out to be true. After 12 years, in 2013, Suresh made a comeback with ‘Ayaal’. Director Lal and Iniya played the leads. Suresh won the Kerala State Film Award (Special Mention) in Direction (2014) while Lal won the Best Actor Award.

Meanwhile, after mulling over what Sreekumar said, Suresh decided to make the film, which is called ‘Kshanam’. The male leads are Ajmal and Bharath while the heroine is Sneha Ajith, a newcomer who stays in Bahrain. Actor Anusithara’s younger sister, Anu Sonara also has a role. And so also has Lal who plays a parapsychologist.

“I have a very good understanding with Lal,” says Suresh. “We know each other for more than three decades. And we have many shared memories.”

The shooting, in places like Kuttikanam and Peermade, has been completed. And the final mix is taking place. The film will be released next month.

During the shoot, Suresh felt the presence of his mother. He had planned a shoot on a hill at Peermade. But each time they went to do the scene, it was raining heavily. A crew member suggested that they could complete the rest of the shooting. “So we did that,” says Suresh. “But I got a feeling that I could get a similar shot elsewhere. I believe it was my mother speaking to me.”

This intuition proved to be correct. When he returned to Thiruvananthapuram, he did the shoot on a nearby mountain. “The effect was the same,” he says. “There was a lot of mist. And it worked out fine.”

But he did find it difficult to find a producer for the film. Right through his career, this has been the case. “That’s because I don’t work with superstars,” he says. But for ‘Kshanam’, Reji Thampi has agreed to co-produce with Suresh under the banner of Roshan Pictures. “I loved the script,” says Reji.

Suresh began his career by working with the late director Padmarajan. He was an associate director for 12 films. This experience helped immeasurably. His debut film, ‘Jaathakam’ (1989), has been one of his most popular films.

Asked the secret to making successful films, Suresh says, “A good script. Padmarajan always used to tell me that. And I believe Kunchacko Boban’s latest film, ‘Anjaam Pathiraa’ is doing very well because of its excellent script. People come to theatres to see stories told well. All the youngsters should remember this.”

(The New Indian Express, Kochi and Thiruvananthapuram)

Published on January 20, 2020 22:21

January 17, 2020

Don’t say cheers, say Adipoli

Drinks entrepreneur Gautom Menon is all set to launch the ‘Adipoli’ drink, which is aimed for the millennial crowd

By Shevlin Sebastian

Three years ago, Gautom Menon, the founder & owner of Wild Tiger Rum was bar-hopping in Thrissur to talk about the newly-launched liquor brand. A few customers told him that they had already bought it from the duty-free shops at Dubai and Muscat airports. “It’s adipoli,” was the remark. Gautom is a Malayali, who grew up in Coimbatore. “At first, I thought they meant Adi puli (which means, hit the tiger),” he says. “But it was only later I came to know that it is a slang word which means ‘awesome’.”

He liked the word so much, and instinctively realising its marketing potential, he registered it as a trademark for his company. And come March, Gautam is launching the ‘Adipoli’ dark and white rum. It has an attractive design which is already drawing rave views on Gautom’s Linkedin page and has gone viral. Says wine writer Ravi Joshi, “The bottle looks awesome!”

The design is in yellow, red and blue. There are a couple of hashtags, squares, rectangles, and circles, two coconut trees, a black driverless auto-rickshaw, and the Adipoli sign: the thumb and forefinger meeting at a point, with the three fingers upraised. Incidentally, the design has been done in-house, by talented designer Paul George.

At the back of the bottle, there are details for two cocktails. One is called the ‘Adipoli Machaan’. The instructions are simple: Add 50 ml Adipoli rum, 60 ml of orange juice, and 15 ml of lime juice. Mix all the ingredients with ice. Stir and pour into a tall glass. Garnish with a fresh orange slice, and say “Adipoli Machaan” before you take a sip.

Another cocktail is the Adipoli Libre. “There is a legendary cocktail called Cuba Libre, which is a mix of rum, cola and lime,” says Gautom. “We wanted to do something similar, with a fun spin, of course.”

The brand is aimed for the millennial crowd, says Gautom. “And so far, no one has dared to market Kerala along with a drink. Through ‘Adipoli’ we wanted to do that. I have noticed that Malayalis all over the world have a lot of pride in their state. So I wanted to give them a reason to embrace something from their neck of the woods and be proud of it. In other words, I want them to forget the word ‘Cheers’ and say ‘Adipoli’ instead.”

Made of dark rum, ‘Adipoli’ is 100 percent molasses-based and uses pristine Indian sugarcane. The flavours are vanilla and toffee. The 750ml bottle is priced at Rs 910 and will be launched in the UAE, Bahrain, Oman, and a few African countries. This will be the main market, apart from Kerala.

Gautom has another ambition. “A lot of brands have made their towns famous,” he says. “For example, Absolut Vodka is made in Ahus in Southern Sweden. The company employs almost everybody in the town. As for Johnny Walker whisky, it is from a town called Kilmarnock in Scotland. Jack Daniels whisky is from Tennessee, USA. My long-term goal is that when people say ‘Wild Tiger’ or ‘Adipoli’, they will say it is from our distillery situated in Pampadi, Thrissur.”

(The New Indian Express, Kochi and Thiruvananthapuram)

Published on January 17, 2020 21:34

January 15, 2020

Wide Open

Ramesh Menon, a BSNL customer, finds no watchman at the gate, doors open, and counters unmanned when he visited the company office at Tripunithara

By Shevlin Sebastian

Entrepreneur Ramesh Menon was working on his laptop early on Wednesday morning at his home in Tripunithara. Realising that the line was a bit slow, he decided he would go to the BSNL office and change his digital plan. But when he reached the building, he found that the gate was open, with no watchmen present.

And nobody was manning the counters on the ground floor. A few rooms which had technical equipment were empty. He went to the first floor to look for some senior staff. Again, he walked about and did not see anybody. All the rooms were in darkness but the doors were wide open. Soon, a few more customers had gathered around. “Everybody looked puzzled,” says Ramesh.

As he stepped out of the building he met a man. “He identified himself as an electrician who looked after the electrical room at the back of the building,” says Ramesh. “He told me that out of a staff of approximately 35, around 19 had applied for VRS. In fact, I read recently, 68.9 per cent of the eligible staff in Kerala have applied for VRS, the highest among all the states.”

Asked the lack of a security guard at the gate, the electrician told Ramesh that he was an employee of an agency which had been contracted to provide security. But because of non-payment of dues, they withdrew the guard.

When Ramesh stepped out, he saw a board which stated, in Hindi, English and Malayalam ‘Today Holiday’. “I missed seeing it,” says Ramesh. “It was at an inconspicuous place. Later, a friend told me that they were closed because of Pongal.”

Meanwhile, an official of the Sanchar Nigam Executives’ Association, Kerala, on condition of anonymity said that on holidays, one person is always deputed to keep an eye on the equipment. “Maybe, at Tripunithara, he might have stepped out to have tea,” he says.

Whatever may be the reason, Ramesh feels pained at the state of BSNL. “It has the best infrastructure when compared to the private mobile companies,” he says. “For my dad, who is 86, and my mom, who is 78, BSNL is their lifeline. They don’t use mobile phones. And for years, I lived outside and stayed in touch with them through BSNL only. What I fear most about the decline of BSNL is that landlines will become redundant. And elderly people will be left without phones.”

Ramesh also questioned this idea of giving VRS to technicians who have two to three decades of experience. “These veterans know where the cable is, and how it connects under the ground,” he says. “Tomorrow, you will have to bring temporary staff by paying higher salaries but who have only three to four years of experience. They will not have much technical knowledge. It will weaken the company.”

(The New Indian Express, Kochi)

Published on January 15, 2020 22:55

January 14, 2020

The life and death of Jesus Christ

Mural artist Sasi K Warier has done a series of paintings on the incidents in the Holy Rosary

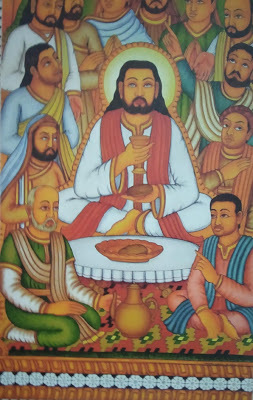

Pics: Sasi K Warier. Photo by A Sanesh. The Last Supper. Jesus Christ and his disciples sit on the floor

By Shevlin Sebastian

The Bangalore-based IT expert Chad Voss came across an article in a newspaper on mural artist Sasi K Warier who had done a series of paintings on the life of Jesus Christ. Intrigued, he did a Google search and managed to get in touch with Sasi. Thereafter, he gave Sasi a commission to do a series on the Mysteries of the Rosary.

These are meditations about episodes from the life and death of Jesus Christ. It begins with the Annunciation and concludes with the Ascension into Heaven by Jesus. It comes under the headings of the Joyful Mysteries, the Sorrowful Mysteries, the Glorious Mysteries and the Luminous mysteries. Each Mystery has five sub-themes, for a total of 20 scenes.

After doing some research, Sasi got down to work. But it took a year before he could complete the project. Initially, he sent rough drafts by mail and Chad approved them. And all these works, measuring 2 ½ feet x 7 feet, were on display at a recent exhibition called ‘Rosary’ at the Indian School of Arts in Kochi.

Expectedly, Sasi gives the images an Indian touch. So Jesus Christ has black hair, moustache and beard instead of the traditional blond colour. And he wears a shawl. His disciples are also black-haired. In the Last Supper, Jesus and his disciples are usually depicted sitting behind a long table, but Sasi has done something different. He has placed Jesus sitting cross-legged on the floor, behind a small circular table. And so are the other disciples. “I wanted to remain true to the Kerala mural style and the Indian habit of sitting on the floor,” he says. In the image, one disciple is looking away. And that is Judas Iscariot who betrays Jesus to the Romans later.

And since the scenes are sombre, Sasi has not given bright coloured clothes to the women. So, he has avoided using necklaces, earrings, rings or bracelets. In fact, he has made dresses as they wear in the Gulf (West Asia) where Jesus lived. Mary has been shown wearing a veil.

And in the Crucifixion scene, where Jesus is nailed to a cross, very little dripping blood is shown. “Again, that is in the Kerala mural style,” says Sasi. Across the top of the frame, above different images, he has drawn angels, pigeons and bells, and musical instruments like the harp, violin and shenai.

Gallery visitor Shreya says, “It is nice, interesting and colourful.” Today, the paintings are hanging in Chad’s house, but he has relocated to the USA.

(Published in The New Indian Express, Kochi)

Published on January 14, 2020 23:02

January 13, 2020

Acing it on the ice

The Kottayam-born and Toronto-based photographer Thomas Vijayan has just won the Bird Photographer of the Year contest with his shot of penguins in Antarctica. He also says that global warming is irreversible

Pics: The prize-winning photograph; Thomas Vijayan

By Shevlin Sebastian

It is a November morning. Photographer Thomas Vijayan is lying on the ice in a penguin colony in Antarctica. Several feet away, an Emperor Penguin and his wife stand behind a baby penguin. They have almost joined their beaks together, as they look down on their newly-hatched baby. The scene lasts a few seconds but Thomas is able to take several shots. “I knew these are rare shots,” he says, via phone from Mexico, where the Toronto-based photographer was on a holiday.

When the female penguin lays an egg, she immediately leaves and goes looking for food for the next two months. During that period, the male balances the egg on its feet and covers it with its brood pouch, a layer of feathered skin. He stands still even when the temperatures go down, and there are icy winds and powerful storms. When the mother returns, she feeds the chick by regurgitating the food stored in the stomach. Soon,.the father goes out for food. “So, it is rare to get all three of them together,” says Thomas, who uses a Nikon D5 camera. “It turned out to be a unique shot.”

The judges at the Bird Photographer of the Year contest conducted by the Society of International Nature and Wildlife Photographers concurred. Last month, out of 2000 entries worldwide, they said the shot taken by Thomas was the best. Incidentally, this is not his first win. Over the course of his two-decade career, Thomas has won over a thousand medals.

But the Antarctica assignment was not an easy one. He flew from southern Chile to the Union Glacier Camp, a distance 2500 km. From there he took a Twin-Otter plane and landed on a sea ice in the Weddell Sea. “Going to the penguin colony was difficult,” says the Kottayam-born photographer. “To cover 14 km, it took me eight hours of walking in soft snow. The leg sinks till the knee.”

But when he reached the colony, the penguins showed no fear. “They had not seen human beings before, so they were curious and friendly,” says Thomas. “Many tried to come close but I kept my distance, as I felt that my germs would be fatal for them.”

This is his third visit to Antarctica. And tragically, he is seeing the effects of global warming first-hand. “Each time I go to a glacier, about 300 to 500m have melted,” says Thomas. “Many of the ice sheets have vanished. So, I do not doubt that it is leading to a disaster.”

He says that in places like Alaska, Brazil and Australia, forest fires are happening because of the increase in temperature. “Last summer, I was in Alaska, and there were 60 incidents of forest fires,” says Thomas. “The whole sky was filled with smoke.”

Thomas pauses and says, “We have destroyed the planet. It is too late for any course correction. What we can do is to slow down the process. I am 110 percent sure the planet will reach a stage where it will be impossible for humans and animals to live, because of the extreme temperatures.”

Nevertheless, Thomas, an architect, feels he must do his bit to preserve the beauty of the earth through his photographs. He has travelled to the Arctic, Tanzania, Kenya, Japan, Russia, Ecuador, Costa Rica and Indonesia.

Some time ago, he had gone to the island of Sulawesi in Indonesia, where he took photos of the critically endangered crested black macaque. He also spent months in Siberia to take shots of the rarest cat in the world called the Amur leopard. “They are critically endangered and believed to be less than 40 in the world,” he says.

Thomas says he feels recharged after each trip. “There is no luxury in wildlife photography,” he says. “It makes a man very simple.”

Published on January 13, 2020 21:45

January 10, 2020

Preserving culinary knowledge

Art curator Tanya Abraham’s engaging recipe book, ‘Eating with History’ has recipes of Kerala which are hundreds of years old

By Shevlin Sebastian

As a child, art curator Tanya Abraham would often go into the kitchen of the family house at Fort Kochi. There she would see her grandmother, Annie Burleigh, in a white chatta and mundu, preparing dishes. “Her skills never ceased to amaze me,” she says. “She formed cutlets in one palm, throwing them in hot fat in a continuous rhythm and stirring curry with the other, while simultaneously monitoring the cooking for at least forty people.”

Thanks to her grandmother’s culinary skills, Tanya always retained an interest in food. “There were so many communities, like the Christians, Jews, Anglo-Indians, and Muslims, who lived next to each other in Fort Kochi and the food would come from all these homes to my home during their festivals,” she says.

Tanya’s turning point happened when her grandmother passed away at the age of 104 a few years ago. “A storehouse of culinary delights went with her,” she says. “It made me think of all the women, like her, who ran households and brought to life recipes passed down generations in their kitchens.”

So, she decided she would bring out a cookbook, but with a specific angle. It should be the ancient trade-influenced cuisines of Kerala. After three years of research, the recipe book, ‘Eating With History’, has just been published by Niyogi Books, in an elegant, easy-to-hold edition, at 202 pages and priced at Rs 550.

It starts with a bit of personal history: the impact of the different cuisines on her Kurishingal family’s household, and in another chapter titled ‘Kerala and Food’, Tanya delves into the history of food in Kerala during the past several centuries.

The recipes have been neatly divided under different chapter headings: Vegetables, Breads, Rice and Appams with Chutneys, Meats and Fish, Sweets and Desserts, and Squashes and Wines (with a dash of spice). For Malayali readers, there is a distinct advantage. All the dishes have been identified with their Malayali names. So fish curry in coconut milk is written as meel pal curry while dry red chilli chutney is called unaka mulagu chamandi.

What came as a surprise for Tanya was to discover how one dish was cooked differently by the various communities. So, for the meen pollichathu, the Syrian Christians used red chillies, onions and shallots. But the Latin Catholics mostly used black pepper, green chillies, garlic, and coconut milk. “The Latins have a vindaloo which is very specific to Fort Kochi and neighbouring areas,” says Tanya. “Then I realised that the Anglo Indians have a vindaloo but it is so different. And they live just two streets away from the Latins.”

Thanks to her research, Tanya discovered that Malayalis developed new eating habits following the intermingling with the Arabs, Portuguese, Dutch and the British. So, when the Portuguese came in the 15th century, they introduced potatoes, tomatoes, and papaya. But the biggest impact of the Portuguese was their introduction of red chillies.

“Fish and meat curries tasted different when red chillies were added,” says Tanya. “The Portuguese also invented the puttu (the steamed rice cake), which is one of the most popular dishes in Kerala today.” As for the Dutch, they left behind the Brudher (a sweet cake with dried plums), which is still baked in one bakery at Fort Kochi. And the British gave the spiced shepherd’s pie and the cardamom flavoured caramel pudding.

All in all, this is a highly engaging book. Tanya has done an enormous service by collating all these recipes, which would have slipped into history and been lost forever.

(The New Indian Express, Kochi)

Published on January 10, 2020 22:07