Shevlin Sebastian's Blog, page 24

September 23, 2020

Life is beautiful

Malayali entrepreneur Suresh Varma, and journalist Danny Geevarghese who have spent several years in Beijing says things are fine despite the India-China border clashes

Photos: Suresh Varma and his wife Karthika; Danny Geevarghese

By Shevlin Sebastian

On a recent Sunday, a group of Malayalis along with their families got together for lunch at the ‘Indian Kitchen China’ on Ritan street in Beijing. They had rice, sambar and a vegetable curry. And during a discussion, they all agreed they wanted to carry on staying in China.

“You develop a sense of belonging,” says entrepreneur Suresh Varma. “This is not only for Indians but for other foreigners too.”

Even the Chinese feel this way about their country. Around 150 million Chinese travel out every year on business, studies or tourism. And they all come back.

“China has the largest number of students who study in foreign universities and after their graduation, 90 per cent come back,” says Suresh. “They want to be in their motherland. It is not like in India, where out of 100 students who go to the US, 90 per cent stay back.”

Meanwhile, the India-China clash at the Galwan Valley in the Himalayas has fast receded from their minds.

Journalist Danny Geevarghese says he was not unduly worried about the clash in the Galwan Valley. “Although this time tragically there were deaths on both sides,” he says. “During most summers, there are skirmishes. But this time it became serious.”

Interestingly, the coverage was far less than in the Indian media.

“Some like the People’s Daily, the PLA Daily and China’s public broadcaster CGTN did not cover it at all,” says Danny. “Facebook, Twitter and YouTube are banned.”

More than the India problem, the Chinese are obsessed with the Americans, and the Japanese who colonised parts of the country,” says Danny. “India does not appear in the news often. Plus, COVID-19 was the big issue.”

But India’s soft power does have an impact. “All of Aamir Khan’s films are a bit hit in China,” says Danny.

Suresh says that many of his Chinese friends did not know about the incursion into Indian territory.

In fact, only one Chinese colleague said, “Because of this problem, I hope you are not planning to relocate out of China.” Suresh replied in the negative. As to how the Chinese colleague came to know about this, Suresh said that nearly everybody can access international news websites like BBC and CNN.

Suresh has been living in Beijing for eight years. After a long professional career, he has been doing business in supply chain consulting for the past three years.

Asked to describe the plus points of the Chinese, he says, “They are very hard-working and dedicated to what they do. They are warm and helpful. There is a clear demarcation about what they are doing and what the government is doing. They are focused on earning money, ensuring their children get a good education and have enough money for their retirement.”

Chinese are similar to Indians, says Danny. “They want their children to go to good schools,” says Danny. “They are very family-oriented. Grandparents look after their grandchildren while their children go to work. When my son goes down to play, in our gated community, a grandmother will ask one of her grandchildren to play with my son.”

One of the negative traits is that the Chinese have a compulsion to ape the West. “People have beautiful Chinese names with nice meanings to it, a lot of historical significance but just because they want to be accepted by the world outside, they will call themselves George, Harry or Sally,” says Suresh.

Suresh gives an example. The actual name of the martial art form Kung Fu is Gong Fu or Wushu. Suresh asked his Chinese friend why they were using the wrong name. He replied that since Westerners find it difficult to pronounce Gong Fu, they use Kung Fu.

As a result, they are losing a lot of their heritage. This is happening in India, too. “The number of people who know Sanskrit or Malayalam is decreasing,” says Suresh. “The next generation of Chinese may not know how to write the alphabet.”

As to the stories in the world media about people being upset about the way they were being treated, during the COVID-19 crisis, Suresh says that in a population of 1.4 billion, about 20 percent will be unhappy at the actions of the government. “I know friends of mine in Wuhan, which was the epicentre, who were happy with the government’s actions,” he says.

The government is supporting the people as much as possible. During the pandemic, all the patients were treated free of cost. “People are thinking, ‘the government is taking care of me, I shouldn’t be worried if they are sending ships to the South China Sea in a contest with the United States,’” he says. “The government knows the big picture, not me.”

Asked whether there is a lack of freedom in China, Suresh says, “I have not come across anything like that.” He gave an example: the US shut down the Chinese consulate in Houston. In retaliation, China shut down the US consulate in Chengdu. Immediately, on social media, a lot of Chinese complained that the government should not have shut down a consulate that was hardly of any consequence. Instead, they said, the government should have shut down the consulate in Hong Kong. “People express their views,” he says. “But there may be a limit and they ensure they don’t cross it.”

Many sites are banned. But people use the virtual proxy network to access them.

As for India, it does not feature in the minds of the Chinese people. “It's not that they look down but they don’t think about India,” says Suresh. “But for business people, they look at India with a great deal of respect. Because, they know, that apart from China, India has a huge population to whom they could sell their goods.”

A lot of Suresh’s Chinese friends told him that India is a beautiful place to visit. They feel that it is culturally vibrant. “But when it comes to economic superiority, they feel they are far ahead and their main rival is the US,” says Suresh.

Asked about the extensive surveillance in a city like Beijing, Suresh says, “Yes, there are a lot of cameras. China has the maximum number of cameras in a public area than anywhere else in the world.”

There are about 400 million CCTV cameras across the country. In December, 2017, the government told BBC reporter John Sudworth to lose himself in a crowd in the city of Guiyang (2000 kms from Beijing). But they were able to locate him in seven minutes using facial recognition software.

Suresh says people feel safe because of the cameras. At 2 a.m., if somebody's daughter has to come back home, after a party, even among the Indians, there is no fear. “The population has the fear factor because of the surveillance so nothing bad will happen,” says Suresh.

But Suresh does admit that if you are a critic of the government you could face problems.

It’s not that China is the only one which is feeding on privacy. Facebook, Twitter and Google also have a lot of data on all the people all over the world.

Meanwhile, Suresh is very happy with his life in Beijing. “The food is great, and the infrastructure is awesome. In eight years I have never experienced a power cut. Or a tap going dry. Or to have no gas in the house. I don’t think I have seen a pothole ever,” says Suresh, whose wife Karthika is a kindergarten teacher in an international school while son Siddharth, after his Mphys at the University of Surrey, is on a one-year assignment at the Institute of Astrophysics, Tenerife Island, Spain.

Of course, since he grew up in Kochi, he accepts the pothole-strewn roads of Kerala. “I take it as part of my India experience,” he says. “I go with the flow.”

But others may find it difficult. Suresh knows a friend whose child was brought up in China. He is now 15 years old and speaks English and Chinese fluently. “He hesitates to go back to India,” says Suresh. “He might settle down in China. No one can say.”

As for the food, when asked whether the Chinese food made in India and that in China is the same, Suresh starts laughing. “There is a world of a difference,” he says. “The Chinese food in India is Indian food made differently.”

A few years ago, the Indian embassy in Beijing had taken a Chinese delegation to Delhi to participate in a trade show at Pragati Maidan. In the night, they were taken to a Chinese restaurant run by Indians. At the end of the meal, one of the Chinese said, “This is very good Indian food. I like it a lot.”

In China, they cook everything on a high flame for a short period. “Each vegetable or meat retains its original flavour,” says Suresh. “For example, when I eat cauliflower in a Chinese restaurant, it tastes like cauliflower. In India, we use too many spices and overcook it. Essentially, we murder the original taste but we create a taste that is quintessentially Indian.”

(Published in Mathrubhumi English edition)

September 16, 2020

On the frontline

The Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHA) of the Indian government talks about their experiences of working during the pandemic

Pics: Shamla PM and family

By Shevlin Sebastian

Shamla PM goes to the government hospital at Fort Kochi and takes the list of the people who have been afflicted with COVID 19. Then, she, along with the other workers, locate the address of the families. They go to their houses and provide food kits, usually made by community kitchens belonging to the state government.

In each kit, there are rice grains and other essentials. “For a family of four, it should last for about two weeksor more,” says Shamla.

The only precaution she takes is to wear gloves and a face mask. She also carries a sanitizer bottle. What they lack is personal protective equipment.

Shamla is an ASHA worker (The initials stand for Accredited Social Health Activist belonging to the Indian’s government’s Ministry of Health and Family Welfare).

She is in charge of 300 households. Shamla says that when somebody is diagnosed with COVID, the neighbours shun the family, as it scares them they will also get it. “That is a problem the family faces,” says Shamla. But she cannot blame the neighbours. It is a colony where houses are very close to each other. So people have a right to be scared.

Shamla advises the family not to step out. But sometimes, they are forced to, as the water tap is outside. So they have to come out and collect water.

Thankfully, in the area where she is staying, the people have appreciated the work she has been doing. Shamla has twice won the ‘Best ASHA Worker Award’. Incidentally, there are 24 ASHA workers in Fort Kochi.

In between, Shamla, 44, had to face a personal crisis. Her husband, Najeeb, 49, a fisherman who worked at the Cochin Harbour, had a heart attack in April. He needs to get an angioplasty done, but the government hospital is busy treating pandemic patients. So, the doctor has given him medicines. Shamla has two children, a daughter, Sujeesha, 30, who is married. Her son, Alameen, 24, is doing a logistics course, but they have suspended classes for the time being. “My family is supportive of my work,” she says.

As the days go past, Shamla isamazed at the power of the virus and its ability to disrupt lives and the economy too. “My husband is not able to earn because the harbour is closed,” she says. “I know of so many people who are jobless. We are going through hard times. And we had already suffered the impact of two major floods in 2018 and 2019.”

It is not a risk-free job. Around 20 ASHA workers have died nationwide. According to newspaper reports, one of them was a woman named Bheemakka, 51, who passed away on May 13.

She was working at a village in Ballari district, Karnataka. The relatives refused to take the body until she received insurance for having died of COVID. However, the doctor said Bheemakka had tested negative for the virus. The cause of death was a heart attack.

There is no doubt about the risks. ASHA workers go to many houses and when they come across positive cases, they inform the hospital. Thereafter, they have to provide the medicines and look for primary and secondary contacts.

Seena KM, Senior Consultant, Social Development, National Health Mission, of the Kerala State Government, says that ASHA workers do a daily tracking of people in quarantine to see whether they are displaying any symptoms of the virus. “If a person becomes symptomatic, the worker will immediately inform the primary health centre,” she says. “Then a swab test is done.”

The workers have to put up posters outside houses where people are in quarantine along with the date. “This prevents outsiders from coming to the house,” says Seena.

On May 21, the state government had launched a campaign called ‘Break the chain’. The aim was to bring about a change of behaviour among the people. ASHA workers spearheaded this programme. They talked about how to keep a distance from each other at funerals and marriages. “The workers also distributed pamphlets, conducted health education sessions and did home visits to generate awareness,” says Seena.

There are over 9 lakh ASHA workers all over the country. In Kerala, it is 26,475. They earn anywhere between Rs 2000 and Rs 7000 per month. Shama, in Fort Kochi, is earning Rs 7000 a month.

Sheeja AS, 44, is also earning the same amount. She is working in Manaloor village, near the Canoly Canal in Thrissur (87 km from Kochi). She has been an ASHA worker for the past 12 years. At present, she has the responsibility for 234 houses. She gives the residents notices from Arogya Jagratha (a Kerala state initiative) of the actions that need to be taken to safeguard oneself during the pandemic.

Sometimes, she buys medicines for elderly people who live alone. So far, nobody has got the virus in her area. She wears a mask, a face shield, and carries a sanitiser bottle.

Some residents are happy to see her. But others have told Sheeja to just call them on the phone. “They told me they had seen on the TV that a few ASHA workers had turned positive, so it scares them I might have it also,” says Sheeja. In Thrissur district, two workers have tested positive.

So, to comfort them, Sheeja speaks from the courtyard itself.

Regarding her family, her husband Premlal, 54, works in a shop at Thrissur. Daughter Krishnendu, 26, is married, while son, Pranav, 24, is working in the credit card section of a bank.

The family takes precautions. As soon as they return home, all of them take a bath first. “We have to do this because you can never say from where the virus will come,” says Sheeja.

As community spread increases in Kerala, Seena says there is coordination between ASHA workers, health volunteers, police, and the COVID Rapid Response Team, so that they can render efficient services.

“We are doing our best,” she says.

(Published in the Jesuit magazine Pax Lumina)

September 15, 2020

This land of ours

By Shevlin Sebastian

The rice is boiling in the steel utensil. Shamila watches as the white grains go left and right, up and down, and in circles. “Just like our lives,” she thinks, as she stirs the water with a wooden ladle.

It is a Sunday noon.

Her husband, Suresh, is an electrician. He meets the family’sexpenses, despite drinking a bottle of toddy every night. Shamila’s son,Pradeep, 22, works in a transport company in Mumbai, while her 20-year-old daughter, Reshma, is a salesperson at a cosmetics shop in a Bangalore mall. As for Shamila, she works as a maid in a house down the hill. But today is her weekly holiday.

Shamila lives in a brick house of three rooms and a kitchen. It is modest: a wooden sofa, and two chairs in the living room. On the low centre table, there is the 'Malayala Manorama' and a vase which has red plastic roses in it. In the bedroom, there is a wooden bed. The only ornamentation is a calendar hanging on the wall. In the children’s room, there is a wet patch at a corner where the ceiling meets the wall.

She takes a few grains in the ladle, presses it with her fingers to see whether it is cooked, and, when she confirms it, switches off the gas stove, and places the lid on top of the vessel.

Shamila walks barefoot to the living room. Clad in a blue nightgown, with white frills at the neck, she sits on a chair near the window and looks at the newspaper. She has pulled her hair back in a topknot.

The house, on the slope of a hill in Thodupuzha, is in a scenic spot: surrounded by rubber trees and wet leaves. The only sound Shamila hears is the tap-tap of the raindrops hitting the asbestos roof. It is peaceful, although, in the newspaper, there are reports of murders, robberies and accidents. “No peace in the world,” she thinks and shakes her head.

Soon, a sound rises at the edge of her consciousness. It puzzles Shamila. It seems like thunder, but she is not sure. What could it be? All at once, she hears shouts: it is a mix of fear and rage. Shamila’s intuition buzzes, and she experiences the first signs of panic: shortness of breath and trembling legs. The shouting goes on.

Shamila opens the door and rushes out. Her neighbour, Parvathy, is pointing up, and screaming.

Shamila glances upwards and sees an unimaginable sight. The top part of the hill is rolling down: thick, red mud, branches, roots, plants, leaves, tree trunks, stones, and bricks. The roar feels like as if somebody is shouting in her ears. “It is a landslide,” Shamila’s mind screams. “RUN, RUN RUN!”

She turns and flees, forgetting all about Parvathy. Shamila takes the narrow mud path, a shortcut to the road below, that people in the area use all the time. “Oh God, please save our houses, I beg you,” she says, even as she concentrates on running on the wet and slushy surface. But in another part of her mind, she knows how deadly a landslip can be. At a sharp turn on the path, she loses her balance but grabs a tree trunk to hold on.

Through the branches, Shamila gets occasional glimpses of the tarred road. At the back, the roar is non stop. She is panting now, more out of fear than tiredness. Shamila notices an overpowering smell in the air and realises that it is of wet mud.

There is a cry of pain, the sound rolling down the hill like a shriek. “Somebody is injured,” she thinks. “Krishna, please don’t kill anybody.”

Shamila reaches the road, her mouth open, her chest heaving forward and backwards with the effort. She can feel the wetness of the road through the soles of her feet. Soon, dhoti-clad men run past her towards the hill. They don’t stop to ask her what has happened. They all know what the roar is and what it means to their lives.

Her thigh and calf muscles are hurting. She has never run so hard in her life. Shamila wants to look back but is scared to see the devastation. But she knows where she has to go -- to her husband’s friend, Murali’s tea shop, a shack by the side of the road, a kilometre away. She has to inform her husband she is safe. In her hurry, she had forgotten to take her phone.

At the shop, Murali is sitting behind a rickety wooden table near the entrance, a white cloth towel tied around his head, like a bandana. The two men, who worked for him, have rushed off to see what is happening. Inside, there are tables and benches, placed against the bamboo walls, with an open area in the middle. At one corner, a TV set, with rusted buttons, has been placed on a shelf of a wooden sideboard.

When Murali sees her, he nods, and says, “Good, you are safe. What about Suresh?”

She smiles and says, “He is at a worksite.”

She asks for his mobile phone. He passes it to her.

Shamila calls her husband and tells him she is okay.

Murali goes to the kitchen to make a cup of tea. Shamila sits down on a bench. She is glad to give her legs a rest, although she is still breathing rapidly. Her heartbeat has still not slowed down. “How does a landslide start, with no warning,” she thinks? The image of the river of mud coming down the hill flashes in her mind’s eye. Her body shudders involuntarily.

Murali brings the tea in a glass, and a white towel. She wipes her face, arms and hair.

She sips with soft slurps.

After a while, she senses that Murali is staring at her. When she looks up, she notices that his eyes are focused on her breasts. He looks frustrated. Shamila knows that his wife is fat and ugly and nags him.

Murali blinks and realises that Shamila does not approve of what he is thinking. Embarrassed, he moves away and switches on the television. Both spot the red and white band moving across the bottom of the screen: “Breaking News: Landslip at Thodupuzha.”

“These TV guys move fast,” he says, with a trace of admiration in his voice.

“Yes,” she says. “They are everywhere. Too much competition, I guess.”

The ticker changes: “Many may have died.”

“Who could have died?’ says Murali, as they gaze at the screen.

“Must be Rekha’s old and sick mother,” says Shamila. “She is bed ridden.”

“What about Parvathy?” she wonders and feels a stab of pain. Was the yell she heard that of Parvathy? Should she have stopped, gone up, and tried to save her? But Shamila knows that if she did that, she would have risked her own life.

“This is a tragedy,” he says.

Shamila nods.

The first visuals are aired. The slope has collapsed. Nothing is left, except mud, thatched roofs, some beds and chairs which are embedded in the soil. The local men she saw on the road are now wading through the muck, pulling away the debris, trying to locate survivors.

Murali looks at her and says, in a flat voice, “I am sorry, but you have lost everything!”

“I am alive,” she says, pointing a thumb at herself. “That is more important than all the possessions in the world.”

Murali’s eyes enlarge, and his eyebrows go up. To have property is so important these days. He does not know what to say. So, he remains silent and looks at the screen.

Time passes.

It is a silent tableau. Both of them gaze at the non-existent slope.

Her husband appears at the entrance. When Shamila sees him, she feels her heartbeat against her rib cage, like a hammer. Suresh’s eyes are wild, the pupils enlarged, and he keeps opening and closing his mouth.

She embraces him. And, like her own experience, she realises his body is shaking. And soon, the tears are rolling down his face.

“We have lost everything,” he says. “There is no land anymore. It has vanished. The house has collapsed. All the valuables are lost, including your gold jewellery. How do we live? What do we do? Where do we go from here? At 45, how do I start from scratch? We have no insurance. And what will this idiotic government do? These politicians are only making money for themselves. They don’t care about the poor. This horrible life that we live, always on the edge, always struggling to make ends meet and to keep our dignity, to give our children a chance for a better life. All this is ash now. Nothing remains. Ashashashash…”

Shamila knows that all what Suresh has said is true. But she does not have the desire to think about the future. She is trying to recover from her panicky run down the crumbling hill. Her mind is blank, but she is glad she is alive, and not buried under the mud. She feels happy that she had the foresight to run, instead of trying to save some of their possessions, knowing that there was no time for that.

“Our children are earning,” she says, in a soft voice. “You are earning. I am working.”

Shamila sees a flash of anger in Suresh’s eyes. He raises his voice, and says, “How much can we earn? Do you know the price of land these days? You need lakhs of rupees. It is beyond us. We are poor, Shamila. We have lost our dignity. That is how cruel God is. I shudder at the life ahead. How will we pay for our daughter’s dowry?’

This mention about his favourite child makes Suresh to cry.

Shamila hugs her husband, trying to press a mother’s warmth to him. She inhales a peculiar smell: a mix of sweat and muskiness coming off Suresh’s body. It is familiar. During the earlier years of their marriage it was appealing, but now she is repelled. She thinks it is the stench of defeat.

Suresh becomes silent but continues to sob. This shock has hit the deepest part of him. Shamila becomes fearful. “Will he find the will and strength to overcome this?” she wonders. Shamila is not sure at all. Her intuition panics once again. She caresses his face and head, like as if he is a child. She knows that, underneath their bluster, all men are Mama’s boys.

“Come, sit down,” she says and leads him to the bench. “Murali, can you make a cup of tea?”

Murali moves to the kitchen.

Suresh wipes his face with a towel, which Shamila extends to him. They both stare at the screen once again.

Suresh’s body is becoming calm, as Shamila can sense that the trembling is slowing down.

Murali brings the tea and places it on the table.

Suresh sips it.

By this time, people troop into the shop. One of them is businessman Harish Raghunandan, who has a walrus-like moustache.

He grasps Suresh’s hand.

“Suresh, you have to remain strong,” says Raghunandan. “The colony of ten houses has been destroyed. Rekha’s mother, Lalithamma, Parvathy and her daughter, Meena, are dead. But there is no confirmation. There are others still buried under the mud. The men are trying to pull them out. It is unlikely there will be many survivors.”

There is pin-drop silence. Nobody knows what to say.

“It is great luck that Shamila survived, thanks to her quick thinking,” says Raghunandan, looking at her with piercing eyes. “If you had waited for half a minute, you would have died.”

Shamila feels grateful for this praise by Raghunandan. She acknowledges it with the faintest nod of her head.

Raghunandan sighs, looks at Suresh, and says, “You may have lost everything, but your family is safe. Be happy about that.”

Suresh wants to be grateful, but all he can think about is the loss of his property. Raghunandan reads his mood and says, “Once I owned a large farmhouse and it burnt down. I had to start from scratch once again. Life has its trials. It is a rare person who enjoys a smooth ride. Sometimes, the setbacks can be life-threatening.”

Suresh stares at him in silence. Shamila knows that her husband will say nothing. In public, he is shy and discreet.

It had been a love cum arranged marriage. The fathers of Suresh and Shamila had been friends for many years and worked as tappers in the rubber plantations of Thodupuzha. Every morning before they set out for work, they would stop at a temple and say their prayers. The families would meet during festivals like Vishu and Onam.

As Shamila grew up, Suresh found her attractive: the shining brown skin, firm breasts, and slim figure were eye-catching attributes. Shamila had a few admirers. But when Shamila turned eighteen, Suresh told his father he wanted to get married to her. Shamila’s father agreed. As for Shamila, she did not have any problems, although she knew her life would be difficult. Suresh was a school dropout, who had apprenticed to an electrician, and was learning the trade. “What can we poor people expect?” she had thought when her father told her about the proposal.

The couple struggled and bought a plot and built the house. And although Suresh drank every night, he was not a wife-beater, and nor was he abusive, like the husbands of her friends. Shamila walks to the door of Murali’s shack and beckons to Suresh to come out. Her husband has a questioning look in his eyes, but she urges him out with a wave of her hand. She no longer wants to sit with a group of men, all ogling her. She wants some privacy now.

When Suresh comes out, Shamila says, “Come.”

“Where to?” he asks, looking baffled. Shamila keeps her face blank, although there is a trace of a smile on her lips.

They walk for several minutes. The rain has stopped. A cool breeze is blowing.

Several ambulances roar past, their sirens blowing. Two police jeeps, with khaki-clad cops in it, also speed past. Following them is a group of men crammed into a minivan. They look like political party workers.

Shamila ignores them all, and, holding her husband’s hand, she turns left from the road, down a mud path, which leads into a forest. They carry on walking. Suresh says nothing. Instead, he is immersed in his thoughts. After walking for 20 minutes, they arrive at a pond. It is surrounded by large trees, with overhanging branches, on all sides, so the pond is hidden from view. Frogs are croaking at the edge of the bank and green leaves float on the surface.

“How did you discover this place?” says Suresh, and his voice echoes in the silence.

Shamila says, “My friend Ashwathy showed it to me one day. Isn’tit nice?”

He nods as they both sit on the bank, next to each other. They stare at the still water.

They can hear bird calls, and the chirp of a squirrel following bya few quick barks. And under all this, there is the ceaseless call of the crickets. The leaves are a shimmering green thanks to the monsoon showers.

Nature was undergoing its annual rejuvenation.

Minutes pass.

Then Shamila turns to Suresh and says, “Let’s always remember what Raghunandan said. If he can come back from disaster, then we can. It is veryimportant that we stay positive and develop a fighting spirit.”

Suresh looks at her, and presses her hand…

(Published in Borderless Journal)

August 20, 2020

A Rajasthani in Kerala

Kerala State Chief Secretary Vishwas Mehta, who was born in Rajasthan, talks about his three-decade stay in God’s Own Country Pics: Vishwas Mehta; with wife Preeti By Shevlin SebastianOn July 22, when Vishwas Mehta, the chief secretary of the Kerala State Government, was returning home, after a hard day’s work at the Secretariat, in Thiruvananthapuram, he realised that it was the birthday of the playback singer Mukesh (1923-76). Vishwas had been an intense fan for many years. He remembers the day Mukesh died, on August 27, 1976, as if it had happened yesterday. The singer had been performing with Lata Mangeshkar at a concert in Detroit, USA when he collapsed with a heart attack. “I was 16 years old then,” says Vishwas. “His songs are so melancholy. I don’t know why I was attracted to them.” Vishwas was devastated when he heard the news. He stepped out of his home at Chandigarh, went to a nearby park and cried for a long time. Then Vishwas prayed to God, “Please give me the voice of Mukesh.” Vishwas also prayed to Mukesh with a similar plea. At his home in Thiruvananthapuram, Vishwas has a mike and a sound system. That night, in the presence of his wife Preeti, and a family friend, through karaoke, he sang ‘Kahin door jab din dhal jaye’ from the 1971 film, ‘Anand’ and other songs. Another version of him singing ‘Kahin door’ can be seen on YouTube. It would seem as if God has granted his wish. He sounds like Mukesh. And he has sung in many public concerts. In his official career, Vishwas has been steadily moving upwards — Sub Collector, District Collector, Secretary, Principal Secretary, and Additional Chief Secretary. On May 31, Vishwas became the Chief Secretary in place of the incumbent Tom Jose who had retired. And he has gone straight into the hurricane as COVID-19 is now spreading all over Kerala through community transmission.“These are busy and stressful days,” he says. “The most important task at hand is to find as many places to convert into first-line COVID treatment hospitals. Every day there is planning and coordination with the different departments so that things move forward smoothly.” What is interesting to know is that Vishwas is a Rajasthani who has now spent 34 years in Kerala. Asked his view about the state, Vishwas says, “Kerala is 15 years ahead of other states in terms of its health and education. It is on par with Europe.” And he has a clear idea of how this has happened. “There are Four ‘M’s’ behind Kerala’s success,” he says. The first M is missionaries. They came over a hundred years ago and set up schools and hospitals. The second M was the prevalence of the matriarchal society. It brought empowerment to women. They got educated and owned property. As a result, they developed independent thinking. The third M is the monarchs. The kings never fought a war with anybody, but they built many schools, colleges, hospitals and public infrastructure like the Secretariat. There was not much consolidation of wealth and power within the royal families. “In Rajasthan, the rulers were engaged in wars all the time,” says Vishwas. “They were fighting the Mughals or the British. So, they needed to make forts and castles to defend themselves. In Kerala, you will not find forts or castles, except maybe, the Bekal Fort.” The fourth M was the first Marxist Government in the world which came to power in Kerala in 1957 through the ballot box. Chief Minister EMS Namboodiripad started education and land reforms. There was a limit to the number of acres an individual could own. Excess land was distributed to the landless. “This was missing in other parts of India where many people do not own land even now and have to work directly or indirectly for a landlord,” says Vishwas. “These four ‘M’s have brought about the transformation that we see today.” But it is not all perfect. “If the people had been aware of their duties also, instead of only their rights, Kerala could have become an island of prosperity,” he says. “There also would not have been this demand for labour from other states.” This now numbers five lakh. And despite having 22 lakh people in West Asia, there is hardly any manufacturing industry, nor do Keralites generate economic wealth. “All they do is make houses, buy cars and jewellery,” says Vishwas. But it does not mean Vishwas does not enjoy himself. He had the best time of his career when he spent four-and-a-half years as Sub-Collector and Collector of Wayanad. He would travel to the most remote hamlet to meet the tribals, like the Panniyan, Kattuniakkan, and the Kurichyan, and try to address their problems. “They will say a road needs to be repaired, or a well needs to be dug deeper as there is no water, or the doctor does not come to the primary health centre or they are not getting their weekly rations,” says Vishwas. He knew that a lot of officers and politicians who visited them had not resolved their problems. Vishwas wanted to restore their faith in the administration. “I tried to fulfill at least one or two of the demands immediately,” he says. “In the collectorate, I would chase the departments to ensure implementation.” There were unusual moments, too. One day, 30 tribal women led by an elderly woman named Ponamma came to the Collectorate. They said they wanted to see the Collector and see the collectorate. So Vishwas led them around and showed them the different departments. For them, it was an eye-opener. At the end of the walk-around, he chatted with them as they sipped cups of tea. He asked the Bishops of the local churches to give him all the donations in kind, like clothes, oil, and rice grains. He would put the materials in the boot of his car and donate it directly to the villagers. He was aware if he gave it to the officials, many things might be pilfered away. After two years, when it was announced that he was being transferred, he was invited to Sulthan Bathery for a farewell. While there, in front of a church, over 500 tribals had assembled. Since he did not want a formal meeting, they surrounded the Collector and started talking to him. At the edge of the crowd, Vishwas noticed a 70-year-old tribal lady. She looked familiar, yet he was not sure. A few minutes later, he suddenly realised it was Ponamma. He said, “How come you are here?” She replied, “I just came to meet you. We are very sad that you are leaving.” When Vishwas was leaving, she caught hold of his hand and put something in it. As the car left, he opened his palm and saw that it was a chocolate eclair. “This was her gift, and it was from her heart,” he says. “It made me cry. It was one of the best gifts I received.” Early Life Vishwas, who was born in Dungarpur in Rajasthan, is the son of a geology professor who taught in Punjab University. So, he grew up in Chandigarh. An exemplary student throughout his school years, he did his MSc in geology. After initial stints in geology research and as a management trainee at the Steel Authority of India Limited, Vishwas got a job as an executive officer at the Oil and Natural Gas Commission. But all along, his father urged him to sit for the civil services examination. To please his father he sat for the exams. In his first attempt he got a rank of 186 and was inducted into the Indian Police Service in 1985. His batch mates included Rishiraj Singh and Lokanath Behera. While Rishiraj is the Director-General of Prisons and Correctional Services, Kerala, Lokanath is the state’s Director General of Police. But Vishwas wanted to join the Indian Administrative Service. So he sat for the exams the next year and got the ninth rank. However, through random selection, he was inducted into the Kerala cadre. Before he embarked to Kerala, all his colleagues sympathised with him. “Kerala is rock bottom in terms of facilities for government servants and the people do not give much respect,” says Vishwas. “Nobody wanted to come to the South.” In North India, the officers lived in palatial bungalows, with many servants at their beck and call. “You are treated like a demigod,” says Vishwas. “But that is not the case in Kerala.” In fact, Vishwas remembers a Class Four staffer telling him one day when he was posted to Mananthavady, “Sir, the only difference between you and me is that you sat for an exam and passed it. I did not have the resources nor the education to do so.” Vishwas was taken aback. “Lakhs of aspirants take the exam,” he says. “It is not easy to get through. But he was unwilling to show that respect.” Vishwas spent one year, from August 1987, in training at Kollam under the collector CV Ananda Bose. Like any first-timer, it was difficult for Vishwas to adjust to the rice-based diet (he preferred chapatis), people, culture and language. But within a year, he got married to Preeti, a homemaker, so his family life became settled soon. In the office, at Mananthavady, he had a clerk translate Malayalam words into English. “I realised that whether you speak right or wrong does not matter,” he says. “What matters is to keep speaking in Malayalam.” It took Vishwas about five years to gain some measure of fluency. “I am still learning,” he says. “People have shown their appreciation because they know I was from Rajasthan. They never made fun of me. That was very nice of Malayalis.” In his personal life, Vishwas has two married sons, Ekalavya (San Jose, USA) and Dhruv (Noida). Both are in the IT industry. Meanwhile, Vishwas remains focused on his work. “My aim is to do good for society and try to make a difference,” he says. “Only when you give back are you honoured and respected.” (Published in Mathrubhumi, English edition)

Long-term impact

Rooma Sarika runs the ‘Rooma Permanent Cosmetics’ clinic at Kochi. She talks about the many beneficial treatments

Rooma Sarika runs the ‘Rooma Permanent Cosmetics’ clinic at Kochi. She talks about the many beneficial treatments By Shevlin Sebastian

The doorbell rang at the flat in Mumbai. Priya Sharma opened the door. It was her former boyfriend Deepak. He had a small plastic bottle with him. It was uncapped. He threw the liquid at her face. She moved sideways, but drops of liquid still fell on her face. She screamed. Deepak fled. Priya realised he had come to take revenge. A week ago, she had ended their two-year relationship. The 30-year-old went to the hospital. The treatment did not cure her. Her lips fell to one side. One eyebrow had gone. She had to keep using the eyeliner to make an eyebrow but it gave off an artificial look. One day, her Delhi-based aunt Mona, who runs a chain of nail studios, called her. Priya told her about the problems with her face. “I have a solution,” Mona said. About a month earlier, Mona did a Google search to look for beauty therapists who did permanent make-up. And she came across the name of Rooma VS who runs a clinic, ‘Rooma Permanent Cosmetics’ in Kathrikadavu, Kochi. She called Rooma, fixed an appointment, flew down and got her eyebrows fixed and lip contouring. So Priya called Rooma, and came to Kochi. When Rooma had a look, she saw that the acid had damaged the eyebrows and an area near the eyes. Her lips did not have a proper shape. “This affected her self-confidence,” she says. “But the other side of her face looked beautiful.” Rooma propagates a technique called microblading. It is a method by which, with the help of microblades, a pigment is placed in the upper layers of the skin. This results in eyebrows becoming full and it can be shaped in a way the client wants. This lasts for two years. Rooma imports healthy pigments from the PhiAcademy, USA.Rooma’s first celebrity client was a noted singer and popular Malayalam TV anchor. Rooma worked on the eyebrows and made it permanent. “I also made the eyeliner permanent,” she says. “So, before a shoot, she does not have to bother about her eyebrows and eyes at all.” Another Mollywood star is also a client. She wanted her eyebrows to be done. So Rooma used the microblading technique. So happy was the actress with the treatment, she appeared in an online advertisement for the beauty clinic. For celebrities, this treatment is a God-send. Because of the mobile phone, people are always taking photos. “So even if a guest comes to the house, they have to rush and put on make-up, because there is a high possibility of a selfie being taken with them,” says Rooma. “It will be uploaded on social media, and so they must look good all the time. That is why permanent eyebrows are an enormous help.” On being asked whether women come to beautify themselves, so that they can look good for their spouses, Rooma laughs and says, “No, it has got nothing to do with husbands. Women want to increase their confidence levels by looking good. Plus, it will help them in their careers like acting and in jobs where they have to interact with the public.” Rooma has a wide range of customers: from 25 to 72. But most of the clients are in the 30 to 40-year age group. Women with distinctive problems come to see Rooma. One woman told her that because of an illness she lost her eyebrows. So, she could never step out of her bedroom without using a pencil and making lines. Unfortunately, the eyebrows looked fake. “She had become self-conscious,” said Rooma. “So, she felt relieved when she could get permanent eyebrows.” Some suffer from alopecia (spot baldness) and have lost their eyebrows. This also happens to women who have undergone chemotherapy. Apart from microblading, other services include permanent eyeliner and lip contouring. Sometimes, when women smoke too much, their lips can grow dark. Or it could be because of the daily use of lipstick, which has lead and mercury in it. To hide the dark patches, they increase the use of lipstick. “But this is like a slow poison,” says Rooma. In lip contouring, Roopa replaces the underlying melanin, a natural skin pigment with mineral pigments. “These are safe,” says Rooma. “It is only metallic pigments that have a side-effect because it gets oxidised. After the procedure, you need not use lipstick at all.” Another procedure is the lifting of the eyelids through plasma treatment. After the age of 30, the collagen content in the skin goes down. When this happens, the skin tends to collapse. “By using a small needle, I try to create some breaks. This will allow the body to make collagen naturally, and the drooping will go away,” she says. Earlier, people used Botox, but it resulted in deposits under the skin. Rooma is also adept at hair extensions. The earlier way was to put clip-on extensions, but that damaged the roots of the hair. “You have to remove it often,” she says. “We use micro ring hair extensions. You don’t need glue, heat or braids.” The strands, matching the original hair colour, are placed seamlessly into the hairline. “You cannot spot the difference,” says Rooma. “The advantage of these types of extensions is that you can wash and comb your hair and nobody will notice the difference. These are also lightweight so that the wearer will not even feel there is extra hair.” It is clear while talking to Rooma that she has a passion for her job. And this love began very early. Early influences One of Rooma’s aunts ran a beauty boutique in Mumbai. During summer vacations, she would come to the ancestral house at Ambalapuzha, in Kochi, where Rooma lived with her maternal grandmother. (Rooma’s father, who worked in the Central Reserve Police Force, had a transferable job). As a child, Rooma idolized her aunt. “She was very beautiful and wore impeccable make-up, with lipstick and mascara,” says Rooma. “I got interested in cosmetics from that age.” After her schooling at the St Mary’s School in Kayamkulam, she did her pre-degree at the Fatima Mata National College in Kollam. At that time, she came across a course for beauty therapists in the newspaper. They would conduct the theory classes through the post. And then she had to do some practical classes. She did not tell her family as nearly all of them are doctors and engineers. “They would not be interested in me doing this course,” says Rooma. “So, I did the course without telling my father. But I confided in my mother, and she gave me the money to do it.” After her BA from the same college, Rooma moved to Kochi where she got a job in Naturals Cosmetics at their Kadavanthra branch. She gained plenty of experience by working there. Later, she became a trainer for other beauty therapists. In 2013, she got an opportunity to do a three-year degree in cosmetology at the Houston Community College in the USA. When she finished that, she took a 1000 sq. ft area, and opened a beauty centre at Houston.This location turned out to be lucky. Because right next to her centre, former Mollywood star Divya Unni was running the Sreepādam School of Arts. Rooma befriended Divya, and the latter sent many clients to her. “Divya gave a lot of support to me,” says Rooma. At that time, she got a chance to do a six-month course at the PhiAcademy on permanent cosmetics. Soon, Rooma got the idea to start a clinic in Kochi. This came to fruition on September 10, 2018. “Ordinarily, I would have been just a cosmetologist and a beauty therapist,” says Rooma. “But the course at the PhiAcademy was a game-changer.” Today, she is the only one to offer permanent make-up in Kerala. And the clients are coming from all over India. The reviews have been good.S. Krishna Som, who did microblading and hair extensions, says, “I am very happy with the quality and efficiency of their services. Also, the products are of superior quality. Rooma and her team are dextrous and qualified.” Priya Anoopkumar says, “Rooma has added a new light in the life of people suffering from alopecia. This is the best service available in Kochi.” Annu Philip, who works in the airline industry, had suffered from thinning hair for many years. It affected her poise and self-confidence. “When I did my hair extensions, I felt so good,” she says. “A big thanks to Rooma.” (Published in Unique Times)

August 11, 2020

Lessons in the drizzle

By Shevlin Sebastian

It’s drizzling

But it doesn’t matter.

I am running,

Around the Jawaharlal Nehru stadium

At Kochi.

The ground is wet,

There are water patches around.

So, I take careful steps.

As I go around,

I see a young man,

In a hoodie,

And track pants.

He is talking,

On the mobile phone.

Standing beneath an awning.

Must be to his girlfriend,

Because he is smiling.

I think to myself,

‘What a wastrel. Do some exercise. Get fit’.

But he is oblivious.

During my next lap,

I see,

A friend has joined him.

‘Two wastrels’, I think,

As I start panting.

My middle-age lungs,

Are aching.

But I like the suffering,

Because it makes me feel good.

When I stop.

On my third round,

They are peeling off their track pants.

I run on..

The drizzle has eased up,

A cool breeze is blowing.

My perspiration-drenched forehead

Gets some relief.

Running triggers

Something primitive in me.

This is what man did,

For thousands of years.

Before the invention

Of the wheel.

I can hear the thud of feet

Hitting the ground

Behind me.

It sounds like heartbeats.

Then these two young men,

Whom I derided,

Whizzed past me

At high speed.

Smooth electrifying movements

Of hands and feet.

‘What?’ I exclaim silently in my head

My perception was

Oh so wrong.

They are athletes,

And they are swift.

And they splash,

Through the puddles.

Fearlessly.

So I had simply

Misunderstood them.

That’s what happens to all of us

We misunderstand

People.

Places.

Communities.

Religions.

Spouses.

Children.

Parents.

Relatives.

Is it any surprise,

Society is so fractured.

I feel like a fool

Message to me: don’t jump to conclusions,

Ever.

(Published in Hello Poetry)

August 8, 2020

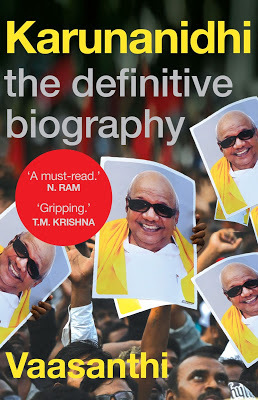

In the spotlight for six decades

Tamil writer Vaasanthi writes about the life and times of five-time Chief Minister MK KarunanidhiPics: The cover; Author VaasanthiBy Shevlin Sebastian Karunanidhi’s father Muthuvelar was playing the instrument called the nadaswaram. The ten-year-old listened as the raga Sankarabharnam filled the room of their home in Tamil Nadu. A few minutes later, there was a knock on the door. When Muthuvelar opened the door, a man said, “Pannaiyar (landowner) wants you to come and see him.” As Muthuvelar set out, Karunanidhi also followed. When his father approached the landlord who was sitting on a swing, Muthuvelar bent his torso and spoke in a deferential tone. After a brief conversation, they returned. But it upset Karunanidhi that his father had to be deferential. Muthuvelar was a farmer who could read and write in Tamil and Sanskrit, and a poet who could recite the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. This incident sparked an aversion in the boy towards the caste hierarchy. “Karunanidhi felt that there was too much of discrimination,” says Tamil writer Vaasanthi, who has just penned the book, ‘Karunanidhi: The Definitive Biography’, which has been published by Juggernaut. “It left a deep mark on Karunanidhi and it lasted till his death in 2018 at 94. It shaped his policies. He felt he had to be just to the underprivileged.” The idea to write the book came at the suggestion of Kannan Sundaram, the editor of Tamil literary magazine Kalachuvadu. Vaasanthi had written a biography of Jayalalithaa earlier, and the first edition became a best-seller. So, she agreed to write on Karunanidhi. When Juggernaut Publishing came to know that she was writing on Karunanidhi they asked her whether she would do an English version. And Vaasanthi concurred. Another reason why she wanted to write the book was that Karunanidhi was a multi-faceted individual: apart from politics, he was a talented scriptwriter, editor, writer and orator. “People outside Tamil Nadu knew little about Karunanidhi as compared to Jayalalithaa,” she says. Jayalalithaa was a Brahmin who belonged to an affluent family. She had an English education. Later, she became a film star and a close friend of superstar MG Ramachandran (MGR), the founder of the All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam, who became the Chief Minister. “MGR made her the propaganda secretary of the party, so she had an easy entry into politics,” says Vaasanthi. As for Karunanidhi, he belonged to the backward community. As to how Karunanidhi could reach the top in a caste-conscious society, Vaasanthi says that when he was growing up, it was a time of great ferment. The freedom movement was taking place. At the same time, Tamil pride was resurgent.British missionary Reverend Robert Caldwell said that Tamil was an independent language and had no links to Sanskrit, unlike other languages. That had a big impact on the Tamil psyche. In the 1930s, E.V Ramasamy Naicker, who later came to be known as Periyar (The Elder), came up with his anti-Brahmin stance and caused a stir. “This appealed to the young Karunanidhi, as he remembered the humiliation of his father,” says Vaasanthi. “So he was in the right place at the right time. Karunanidhi was also intelligent, hard-working and ambitious.” For her research, Vaasanthi met up with politicians belonging to different parties. K S Radhakrishnan, a member of Karunanidhi’s party, the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK), gave her access to a vast library at his home. “It was astounding,” says Vaasanthi. “There were articles, photographs, history of the Dravidian movement, the journals of the founder Periyar, film scripts and copies of the daily letters that Karunanidhi wrote to the workers in ‘Murasoli’, the party organ.” These were neatly bound in several volumes. The entire first floor has been dedicated to this archive. As the editor of the Tamil edition of India Today for ten years during the 1990s, Vaasanthi gained a deep knowledge of the leaders of the two Dravidian parties and their functioning, and that helped in writing the book. She did not read any biography on Karunanidhi written in Tamil or English before writing the book. However, during her research she came across Sandhya Ravishankar’s book on Karunanidhi in English. As a journalist, Vaasanthi had interacted with Karunanidhi’s children, MK Stalin, MK Alagiri and Kanimozhi, but did not speak to them specifically when she was writing the book. She did, however, speak to Shanmuganathan, Karunanidhi’s long-standing personal assistant, and Durai Murugan, a prominent leader of the DMK and a close friend of Karunanidhi. Apart from that, Vaasanthi had many personal interactions with Karunanidhi and developed a close rapport. She also read the six-volume autobiography titled ‘Nenjukku Needhi’ (Justice of the Heart). “There was sparse information about the childhood of Karunanidhi,” she says. “So the first volume was invaluable for me.” Vaasanthi knew that the five-time Chief Minister had the state of Tamil Nadu foremost in his heart. “The North, for a long time, believed he was a secessionist, but Karunanidhi always stressed on the concept of federalism,” she says. “He strived for greater autonomy for the states within a strong, federal structure at the Centre.” However, if Karunanidhi had been alive now, he would have been upset at the way the Centre is squeezing the states’ decision-making abilities and financial freedom. “The Centre is doing this because it has an absolute majority in Parliament,” says Vaasanthi. “The Opposition is weak. But he would have never shirked from raising his voice. Instead, he would have galvanised the opposition.” But Karunanidhi had his flaws, too. He misjudged the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) of Sri Lanka. “It shocked him when the LTTE carried out the assassination of [Indian Prime Minister] Rajiv Gandhi in 1991 at Sriperumbudur,” says Vaasanthi. “He had wanted to help his fellow Tamils across the Palk Strait. But the problem was that Karunanidhi did not understand the mindset of LTTE supremo V. Prabhakaran.” On being asked whether she learned anything new about Jayalalithaa and Karunanidhi, Vaasanthi says, “Even though both were powerful leaders, with a mass base, they were very vulnerable. They could be fooled into thinking somebody is honest or a loyal friend. And because of the isolation that supreme power brings, both were very lonely.” But as an administrator, Vaasanathi had no doubts that Karunanidhi was far better. “He would have efficiently handled the current pandemic,” says Vaasanthi. “His advantage was that the bureaucrats revered him and implemented all his orders at once.”The quality that Vasaanthi admired the most about Karunanidhi was his power of conviction. “You have to believe in what you do or say,” says Vaasanthi. “He was such a powerful Dravidian leader. He played his cards very well about being secular and protecting the rights of the states.” But like most human beings, there was a marked decline at the end. His health broke down and it pained him that his beloved daughter Kanimozhi had to spend six months at Tihar Jail in 2011 because she was an accused in the 2G telecom scam.“By then he became silent because doctors had inserted a tracheostomy tube in his throat to help him breathe,” says Vaasanthi. All these details and many more are crammed into the 259-page narrative. The book is an enjoyable read. Vaasanthi is a seasoned writer. She has published 40 novels and six short story collections. So, she knows how to write in a gripping style. There is an intensity of tone that seems to ensure a reader will follow her to the very end, despite the never-ending distractions of Whatsapp and social media. (Published in HuffPost India)

August 6, 2020

Facing the abyss

Stakeholders in Fort Kochi and Jew Town, including Kashmiri shop owners, restaurant owners, travel agents, businessmen and homestay owners are struggling, but hope is not lostPhotos: Jew Town; Sajid Husain Khatai; Junaid Sulaiman; Sajid Saj with foreign guests

Stakeholders in Fort Kochi and Jew Town, including Kashmiri shop owners, restaurant owners, travel agents, businessmen and homestay owners are struggling, but hope is not lostPhotos: Jew Town; Sajid Husain Khatai; Junaid Sulaiman; Sajid Saj with foreign guests By Shevlin Sebastian

On most mornings, Sajid Hussain Khatai goes to his shop in Jew Town, on the road leading to the Jewish Synagogue. He switches on the fans and lights. He is aware no customers are going to come. But Sajid is doing this, to prevent fungus attacking his carpets, shawls and cotton textiles. He keeps it open till 2 p.m. Then he returns home. But now, with rising rates of coronavirus victims, Fort Kochi is in lockdown. Sajid stays three kilometres from his shop. And he has been unable to open the shop. But the situation in the shop is not alarming. However, Sajid is wondering about the state of the goods in his friends’ shops. These have been closed for three months. “Most of the carpets will be spoiled,” he says. Sajid is from Srinagar. He came to Jew Town in 1998. He is one of the first Kashmiris to settle in Fort Kochi. Like most Kashmiris, he runs a handicrafts shop. He has another shop, near the Mattancherry boat jetty. Kashmiris have about 110 shops in the area. A total of 450 Kashmiris stay in Jew Town and Fort Kochi. But about 440 people have gone back. Sajid has stayed back because his wife works in the MG Road branch of The Jammu & Kashmir Bank. His two daughters study in Choice School. Now they are attending online classes. “The economic damage is huge,” he says. “Our business depends on tourists. Now, there is nobody. We have been suffering for the past few months. The reason many Kashmiris left was to avoid paying the home rent.” Interestingly, many of those who have gone back to Srinagar have started other businesses. One person has started a wholesale business in garments; another has become a transporter; a third one has become a distributor. “If they succeed, they might not return,” he says. Sajid feels that nothing will happen in the upcoming tourist season which starts from October and ends in March next year. “The only way foreigners will come is if a vaccine is found,” he says. “Otherwise, nobody will take the risk of travelling. I believe this will be the case with domestic tourists, too.” He has spoken to travel agents and they expect that things will return to normal only by August 2021. The problem is that since economies have gone into a tailspin all over the world very few people will have the money to travel. “They will be more interested in clearing their debts,” says Sajid. “Bread and butter issues will be paramount. So, the last thing on their minds will be travel.” It is a cloudy morning. Junaid Sulaiman is standing in front of a building which he owns, just next to the Synagogue. “It looks like a full-fledged hartal,” he says, as he points at the empty street and the shuttered shops. “In the months of November to February, because of the presence of so many foreign tourists, I would feel I am in a European country. But now all that is gone.” As for the Synagogue it has been closed for the first time in 452 years. Junaid runs the Mocha Art Cafe. His patrons have included the famed Hollywood director Steven Spielberg and the Vietnamese photographer Nick Ut who shot the Pulitzer Prize-winning photo of children fleeing a bombed-out village in Vietnam. He closed the cafe on March 14, when he heard that some foreigners in Munnar had been afflicted with coronavirus. He felt he could open on April 1. But his plans went haywire. “We never imagined it would last for so long,” says Junaid. Out of ten staffers, three have gone back home. At the cafe, there is a manager, an executive chef, two baristas (coffee experts), one sous chef, and a sweeper. Junaid continues to pay their salaries. One day, Junaid got a call from Aneesh Sharafudeen, the Kerala state head of garment company FabIndia asking for a cut in the rent. The company has a showroom in Junaid’s building. He replied he would think about it. Junaid, who owns the most number of buildings in Jew Town, consulted with the other owners. In the end, they waived off the rent from March 15 to May 31. From June 1 to September 30, 50 per cent have been waived. Junaid has his heart in the right place. One day the Kashmiris approached him for help to get a train from Kochi to Kashmir. So, Junaid met the Collector S Suhas and Agriculture Minister Sunil Kumar. Sunil, a member of the Communist Party of India, is in charge of Ernakulam. Five days later, the Nodal Officer for Kashmir RS Shibu called Junaid from Thiruvananthapuram. A train was arranged on May 20. About 400 Kashmiris got in at Ernakulam and another 400 from Thiruvananthapuram. Around 16 students from Mangalore also boarded the train. The last stop was Udaipur. Thereafter, they took buses to reach Srinagar, 1400 km away. Junaid has another business of distribution of Fast Moving Consumer Goods. These include butter, ghee, flour, wheat, biscuits, jams, edible oils, and cornflakes. However, he has not been able to deliver outside the containment zones. Other distributors are in a similar predicament. “People will suffer,” says Junaid. Apart from the people the economy is suffering. Says Sunny L Malayil, the president of the Indian Chamber of Commerce and Industry: “There is a severe economic impact in Fort Kochi. We had a flourishing tourism-related industry. But now, there is a huge dip in income. At this moment, there are no foreigners or domestic travellers.” The Chamber estimates there has been a loss of income to the tune of Rs 100 crore in the past few months. He says that around 20 percent of the businesses will close down permanently. Those who were handling the Holy Land trips to Israel and Palestine have also suffered a blow to their business. However, he says that if the Kochi Muziris Biennale takes place in December, there might be a revival, of sorts. Sunny says that last year the Chamber had conducted a seminar to analyse the economic impact of the art festival on homestays, hotels, restaurants, and the transportation sector. In the previous Biennale, there were six lakh visitors. Out of that, around 60,000 were outsiders. Many of them stayed in premium rooms, of which there are 700 in Fort Kochi and Willingdon Island. The general sales tax for each premium room is Rs 2000 per day. “For the last Biennale, the state government invested Rs 7 crore, but the returns, through tax, was about Rs 200 crore,” says Sunny.Everybody gained, including the handicrafts shops, homestays, restaurants, auto-rickshaw and taxi drivers. “But now, the opposite is happening,” he says. “It is a loss all around. Those who have taken loans and are paying interest, their debt is growing day by day. They will find it very difficult to manage.” The 2020 season is gone. “We are hoping by next year, there will be a semblance of normality,” he says. Eldose Baby, who is a staffer of the Kochi branch of International Trade Links Tours and Travels Pvt. Ltd., confirms that no domestic tourists have gone anywhere for the past few months. Earlier, they would send people to Europe, the USA, China and Russia. “There are no group departures,” he says. “But since I work for a multinational company, we were offering support to passengers who were returning from other countries in evacuation flights from Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. The situation remains grim.” It’s the same for Sajhome Homestay owner Sadiq Saj. His last guest was Darren and his wife, from the UK, who left on March 18, just before the lockdown. And Darren left a sweet review on Trip Advisor: ‘We couldn't thank Saj and his family enough for looking after us during our stay, organising our trips for us and recommending places to eat and enjoy the sunset. Fantastic breakfast, clean rooms and great service.’ Sajhome has won the Trip Advisor Traveller’s Choice Award for seven consecutive years. When Sadiq closed down his homestay, he had 30 bookings. But once international travel was banned, the guests had no option but to cancel. Sadiq has been running his homestay for the past 12 years. There are five rooms on the first and second floor, while he stays on the ground floor with his wife and two daughters. It is located opposite the office of the Biennale. “I have zero customers,” says Sadiq, who had worked in the Hyatt Regency in Dubai for 13 years. His guests usually come from Britain, USA, Australia, Canada and many countries in Europe. He believes that things will change only when international flights are restarted all over the world. Thereafter, the World Health Organisation has to give the green signal. Then only will he think of opening his homestay. And so the town, which is heading for a curfew, because of a rise in coronavirus cases, is lying comatose. But the residents are hopeful that after the dark times, the dawn will come.

(Published in Mathrubhumi (English edition)

August 3, 2020

Why are you afraid?

This poem won 'Honorable Mention' in the New Poets competition at Allpoetry.com

By Shevlin Sebastian

Why is the powerful Leader

So afraid of the creative people —

the poets, painters, and writers.

These guys have nothing

Except the tools of their arts.

Brushes, paints, easels and canvases,

Words, sentences, paragraphs.

So why is the Leader

Who has the Army, Navy and the Air Force

At his command,

Who has the intelligence bureau,

And the shadow police

Monitoring the population

24/7

Why is he so afraid of the

artists?

Why is he so scared of criticism and protests?

None of these artists or protests can dethrone the leader

So why?

The answer is simple.

The leader lies

All the time

When you lie

For some unknown reason, you feel afraid

Of the Truth

Because the utterance of

Truth

Can shatter the edifice of lies.

Hence, the severe response

To the truth-teller

The leader fears

that his rule can collapse.

And as history shows,

it does.

To build something enduring

Truth and love have always been the cement

While lies and hatred are the sand

Porous and weak.

So, dear leader

Tell the truth

And you will not be afraid

Of anybody

Always remember

What the Nobel Prize laureate

Alexander Solzhenitsyn said,

“One word of truth,

Can outweigh the whole world.”

July 29, 2020

When my daughter made a bowl with newspapers

By Shevlin Sebastian

When I was in Class 4 at the St. Xavier’s school in Kolkata, the class teacher Miss Peterson said that the students should make a chart of the city of Mumbai, along with photos of iconic monuments and the history of the city. It filled me with dread. I was poor at artwork — cutting pictures from magazines and writing text using a felt pen.

Seeing the panic on my face, my mother helped me out. However, when the charts were put up on the wall, I got a shock. Miss Peterson selected mine as the best. I had no option but to blurt out, “Miss, my mother helped me.”

She smiled, nodded and said nothing. I believe my honesty saved me that day. Throughout my school years, I always had this problem with practical projects.

God knew when I had children, and they came to me for help with projects, my old helplessness would come to the fore. So, He gave me a break.

Both my children, a boy and a girl, right from childhood were adept at doing projects on their own. They could do drawings, cut pictures, and paste them on chart paper. They suffered none of the nervousness which I went through. And they did not need any help.

It was a relief.

And my daughter Sneha, throughout her childhood, amazed us with the original things she could make. I remember a coir bag, a man with a thick walrus moustache painted on the back of a coconut shell and a beautiful large chart, with paintings and photographs, which celebrated her grandmother’s birthday.

Then a few days ago, in the afternoon, at our home in Kochi, I saw her take a sheet of a newspaper, cut it, then fold it, and using glue, she made a vertical frame, like a circular fort. Within the frame, at the bottom, she placed a round cardboard. Then Sneha interlinked paper sideways into the vertical frame, and soon the bowl gave the impression as if she had woven it. It was painted black on the outside. Then, using craft paper, which she cut deftly, Sneha made multi-coloured flowers and leaves and pinned it on a green sponge she had kept inside the bowl. Overall, the impact was stunning.

And Sneha did all this, with songs by John Legend, Ed Sheeran, Sam Smith, Dean Lewis, James Arthur and Taylor Swift’s haunting new single, ‘Invisible Strings’, playing loudly on YouTube through the TV.

So, amidst the raging pandemic, we enjoyed moments of joy.

It also made me think about creativity. How some people have it and most don’t.

How things come so easily to the ones who have it.

Talented people, especially in the arts, are markedly different from normal people. They have an original thought process. They don’t follow a path laid down by others. They are keen to find their way. They listen to their intuition a lot. They don’t care what people think about them. They break the rules of morality and don’t feel any guilt.

In my career of interviewing a wide variety of people, artists have been the most interesting, whether it be in art, film, music or theatre. Journalists are not far behind. When you talk to these people, time stands still. The exceptional artists have magnetism and charisma.

I believe in the proverb, many are called, but few are chosen.

Talent is a gift from God. But not all talent is popular. Again, a minority is given the talent that cuts through the hearts of a majority of people. Musicians like AR Rahman or RD Burman, singers like Kishore Kumar and Lata Mangeshkar, bands like Abba or the Bee Gees, or authors like Charles Dickens or Victor Hugo have it. There may be greater artists, but the majority cannot understand their work.

This was confirmed by Rahman’s sister AR Raihanah, whom I met when she came to Kochi in 2015. And this is what she said, “My brother has been blessed with a God-given talent. Many music directors are geniuses. But nobody knows them outside Tamil Nadu. This mass appeal is a divine gift.”

So, for young people, the biggest question is: what do I have the talent for?

Malayalam writer and public intellectual Mohana Varma told me recently that when he was sixteen, he was good at table tennis. But somewhere along the way, he felt that he did not have a genuine talent for it. So he stopped playing. He did not want to waste his time.

He also told me that his teenage grandson expressed an interest in painting. So Mohana arranged for an art teacher to teach him the techniques. But after three months, the grandson said, “I cannot paint images from my mind, but I am good at copying. I don’t think I have the talent.”

Many people make mistakes in identifying the talent they have. There is an initial promise, and they think it is a genuine talent. But then it fades away. It could take a decade for this to happen. By then, it is difficult to start afresh. And one’s destiny is missed.

To ensure a right decision is made, consulting your intuition seems to be the best way. For that to happen, you have to develop it. To develop it, you have to be reflective. And have the ability to go inside oneself. It’s not easy.

But I believe that is the only way one can make the right decision. However, Mohana told me 90 percent of the people get this extraordinarily important decision wrong.

But if you are lucky enough to be in the 10 percent, you will experience heaven every day.