Shevlin Sebastian's Blog, page 23

March 15, 2021

The Malayali girl who worked for Joe Biden

Lubna Sebastian, 24, was the national director of students for Joe Biden during the latter’s 2020 presidential campaign. She speaks about her experiences

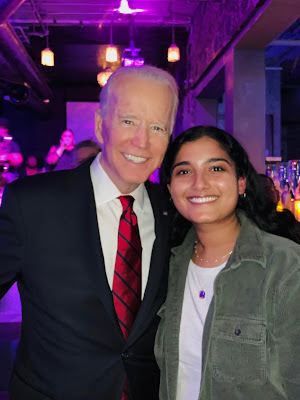

Photos: Lubna Sebastian with President Joe Biden. The family (from left) Adila, Lubna, Shahin and Sebastian

By Shevlin Sebastian

On October 18, 2019, Lubna Sebastian was having a turkey sandwich in a hotel hallway in Houston. She was helping the Joe Biden campaign before the debate among the presidential candidates of the Democratic Party. Suddenly Biden came up, saw Lubna, and said, “Thank you for coming all the way down here.”

Lubna, who had flown in from the campaign headquarters of Philadelphia, a distance of 2900 kms, smiled.

After another debate at Las Vegas, Lubna went up to Biden and said, “Congratulations, you did a superb job.”

Biden smiled and said, “Thank you.”

Lubna saw Biden on the road when she worked on the campaign in Iowa and Nevada. “After each speech, Biden would stay at the venue for two hours, interacting with the local people,” she said. “It was crazy. I did not know you could have so much access to a prominent politician.”

Biden’s humanity always had an impact. “You may only have 30 seconds with him but people would immediately share their problems: ‘My child has cancer’ or ‘I got laid off’,” said Lubna. “He is a person with whom it is easy to be comfortable with. He will listen and connect with you, no matter where you are from.”

Asked the difference between Biden and former President Donald Trump, Lubna said, “He is the exact opposite of Trump. The level of exhaustion because of what happened during the past four years is immense. We have lived through a disaster. During the eight years of the Obama-Biden administration, things were so calm that people became a little politically absent. Even I was, at times.”

But for students who grew up during Trump’s presidency, they had to endure tough times. “They saw mass shootings go unanswered, while their parents could be struck off benefits from Obamacare,” she said. “They had seen kids in cages, who had been separated from their parents on the border with Mexico. They heard about a ban on people from six Muslim countries. Some international students were worried about whether they could study further because of possible future immigration laws. The list goes on. The level of stress which people lived under was abnormal.”

As a result, the students became politically active, including Lubna. She joined the campaign, ‘It’s on Us’, which was founded by the Obama-Biden administration. This was a programme to raise awareness of sexual assault on campuses. She became one of 105 students across the country who became a national committee member.

Asked why a 24-year-old like her supported one of the oldest candidates (Biden is 78), Lubna laughed on a Zoom call, and said, “I grew up seeing Biden on TV. He always seemed personable, someone who was very empathetic and down-to-earth. I felt I had a connection with him.”

Lubna joined Biden’s campaign as an assistant. When some students, after doing their internships, returned to their schools, Lubna set up a programme to keep the students plugged into the campaign.

In July, 2020, Lubna was promoted to be the national director of students for Joe Biden. There were over 400 student chapters. Lubna developed campaign updates and national events for the students across the country.

By this time, Lubna was working 16 hours a day. “Campaign work is back-breaking, and you cannot do it unless you deeply believe in the candidate,” she said.

On September 3, 2020, Lubna sat for her citizenship examination. Later, Biden wrote a letter in which he congratulated Lubna on becoming a citizen. ‘Your family decided to make this country home because they knew, above all else, America is all about possibilities,’ he wrote.

Lubna voted by mail for Biden, on October 3, a month before the election.

After the campaign, in which Joe Biden defeated Donald Trump to become the 46th President of the United States, Lubna worked on the committee that organised the inauguration ceremony of Joe Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris. After a month relaxing, Lubna is now job hunting from Bethesda, Maryland, where she is staying with her parents.

Lubna’s father Sebastian James is a Washington-based economist with the World Bank. A graduate of the Indian Institute of Technology, Delhi, in 1995, he got into the Indian Revenue Service and was posted in Delhi. Later, he completed his Master’s and PhD from Harvard University. He resigned from the Government of India when he was Joint Commissioner and went to America in 2002. “I wanted a more challenging life,” he said.

A Christian, he is married to a Malayali Muslim Shahin whom he had met in Delhi. “It was love at first sight for me,” he said.

Asked whether the couple faced pressure from their families when they decided to get married, Sebastian said, “Shahin’s father did not believe religion should come in the way of two people who are in love. My side of the family had some reservations, but I convinced them that Shahin’s character was more important than her religion. In both our families, we had members who had cross-religious marriages, and they were doing fine.”

Apart from Lubna, the couple has another daughter, Adila, who is 17.

Interestingly, both Lubna’s mother and she were born in the All India Institute of Medical Sciences at Delhi, which was set up in 1956. The family migrated when Lubna was five years old. “Growing up in America, there was a lot of pressure to conform,” said Lubna. “No one could pronounce my name. Or they would do it incorrectly. I looked very different from my classmates, most of whom were white. As a child, you don’t want to be different. You want to be like everybody else.”

She felt she did not belong at times. But when she grew up and worked on different professional projects, Lubna met with a diverse range of people who belonged to so many different countries. “We had the most fun, and brought unique experiences to the table,” she said.

Asked the meaning of her name, Lubna said, “It is an Arabic word which means river of milk in paradise. It is also the name of a tree that produces a fragrant flower.” Many people tell Lubna it is a beautiful name, including her family who are originally from Thiruvananthapuram.

When she was growing up, she would come to Kerala once every two years. But in college, the gaps became larger. The last time she came was in December, 2019. “I grew up with my mom’s parents, because they were in Delhi, so I was closer to them,” she said.

Lubna admits that when she comes to Kerala, she feels she is reconnecting with her roots. “I blend in a lot more easily because everybody looks like me, unlike in the US, where I don’t always see anybody else like me,” she said.

Lubna particularly enjoys eating the fruits in Kerala which she says are very fresh, like mangos, bananas, and guavas.

Asked about her plans, Lubna says she is interested in a career in politics. “There are different ways to be politically active,” she said. “It can be through elected office, or advocacy groups that are inherently political.”

(Published in OnManorama)

February 16, 2021

Face-to-face with death

By Shevlin Sebastian

Mangalore native, Shazeer Majeed, a war surgeon talks about his work in Yemen, Syria, South Sudan, Iraq and Jordan

On a sunny February morning, in the residential area of Shmeisani in Amman, Jordan, the Mangalore native Shazeer Majeed looks out of the third-floor window. He has been in Amman for the past one year as the medical director for the Reconstructive Surgery Project of Medecins San Frontieres (MSF).

The organisation brings in war-wounded patients who need reconstructive, maxillofacial, plastic and orthopaedic surgery from Palestine, Iraq, Yemen as well as Syrian refugees living in Jordan. “We want to return them to a near-normal life,” said Shazeer.

But as he stared out of the window, the image of Noor Abdullah (name changed) came to his mind. The 14-year-old lived in the town of Ad Dahi in Yemen. He had found a land mine near his house. He tried to open it because it fetched a good price with scrap-metal dealers, but it exploded.

The major injury was to his right hand. Noor was rushed to the emergency room of a hospital run by MSF. “There were a lot of shrapnel wounds and his forearm had fractured,” said Shazeer, who is a war surgeon. “The main artery which supplies blood to the hand was damaged.”

The boy was in shock. But at the same time, he was aware of his injury. He kept telling Shazeer, “Please do not amputate my hand.”

At that moment Shazeer did not have the equipment or the instruments to do vascular surgery. The instruments were in another MSF project, at Hodeidah, 53 kms away. But within an hour, it was brought to the hospital.

Shazeer did a graft repair. He took a vein from the leg and used it on the forearm. “We were able to re-connect the arteries and restore the blood supply, which fixed the fracture and saved his hand,” said Shazeer, who has done numerous stints in South Sudan, Iraq, Syria, Jordan and Yemen. Within a couple of weeks, Noor was able to move his fingers and arms. And in four months, he made a complete recovery.

But not everybody experiences this recovery. Shazeer admits there are many times when the patient dies. “But I pick myself up,” he said. “Honestly, we are putting in 16 or 18-hour days and when we return to our apartments, we just want to sleep. There is no time to think about victory or defeat in the operation theatre. Sometimes, after a patient passes away, we immediately begin work on another patient to save his life.”

There have been times when Shazeer has worked for over 30 hours at a stretch. This was during a stint in Yemen. “There was fighting close by,” he said. “We just kept receiving patients, so we slept when the operation theatre would be cleaned before the next patient was brought in.”

Shazeer says that he copes with the job by shutting out thoughts about it as soon as he leaves the MSF Mission. “Otherwise, it would be impossible for me to remain calm,” he said.

Sometimes, the MSF sends its staff to another country for five days, so that they can recover from the stress and the tension. “So, if you are in Yemen, they will send you to Djibouti,” said Shazeer.

As for the patients, most of them are ordinary men, women and children. The military has its hospital to treat their victims.

Usually, the people suffer from wounds and injuries which take place when a bomb blast happens. There are also high-velocity bullet injuries. But not all injuries are caused by the war between the Saudis, who are allied with the government of Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi and the Houthis.

“Sometimes, bullet injuries happen when there are fights between family members or friends because Yemen has one of the highest ratios of gun ownership per population in the world,” said Shazeer. “Everyone carries a gun in Yemen.”

Even minor injuries can become fatal. Sometimes, the bullet may hit the leg. But if the hospital is four hours away, the person will bleed to death. Sometimes, the gunshot may be to the chest but the hospital may be only 20 minutes away. “Then he will get proper treatment and survive,” said Shazeer.

Most of the time there are no facilities, like in any hospital. “There is a shortage of blood, or sometimes, we don’t have the right equipment,” said Shazeer. “It is usually a low-resource setting. So, I have developed ways to overcome these limitations.”

As to the precautions that are taken to safeguard the lives of the doctors, nurses and patients, the MSF shares their location with the warring parties. On the roof of the hospital, there is a large logo of MSF; this can be seen from the air, along with the Red Cross sign which depicts a hospital. However, despite these precautions, MSF hospitals have been targeted in Yemen and Afghanistan.

On May 12, 2020, insurgents attacked the Dasht-e-Barchi maternity hospital in Kabul. Twenty-four mothers, children and babies were shot dead. “The organisation is always in touch with the local authorities and keeps them updated,” said Shazeer. “We tell them we are impartial and neutral and have only one aim: to provide medical care to the people who need it.”

Shazeer feels sad about the impact of the six-year war on Yemen. The economy is in freefall. Many young Yemenis want to go abroad for studies. Now they are unable to do so because of severe financial constraints. The medical facilities have broken down.

“There is a lot of hardship, and a high degree of malnutrition because of food shortages,” he said. “There are outbreaks of cholera. But the people are nice, humble and smart. They are eager to learn and are good at grasping a subject.”

Expectedly, Yemen had a large number of Malayalis. Before the war began in 2014, his MSF colleagues in Yemen worked with a lot of Malayali nurses. Now all of them have left the country. Many of them took advantage of Operation Raahat, which was conducted by the Indian Armed Forces to evacuate Indian citizens and foreign nationals from Yemen in April, 2015. “I don’t think there are any Malayalis left in the country,” said Shazeer.

However, there are many Yemenis of Indian origin. Their great grandfathers had migrated to Aden from India during the British rule, which began in 1839.

A desire to help

Shazeer joined MSF in September 2014, because he was interested in doing humanitarian work. His inspiration was his father, Abdul Majeed, a surgeon who always helped the downtrodden as well as his former mother-in-law Nimmi Sheriff. “Their work for the poor had a big impact on me,” he said.

As for his education, he did his undergraduate studies from Yenepoya Medical College in Mangalore. This was followed by a residency in general surgery at the Amrita Institute of Medical Sciences in Kochi. Then Shazeer did his ‘humanitarian surgery in an austere environment’ from the Catholic University of Leuven, Brussels in 2018. At present, he is pursuing his Master’s in Public Health from King’s College, London.

Meanwhile, all these years of working in war zones has changed Shazeer. “I appreciate life much more,” he said. “We complain when we don’t have electricity in our houses for 15 minutes but there are people who stay in 50 degrees centigrade, and do not have power for days together.”

It is also a blessing to walk around in a city like Mangalore. “You can get out of your house, and get back without any major incident happening to you,” he said. “That is no longer the case in Syria, Palestine and Yemen. You could be shot at or bombed. I appreciate everything about life.”

Whenever he finishes a stint with MSF, Shazeer returns to Mangalore where he does operations alongside his father Abdul who works in private hospitals.

Asked how he has viewed the incessant attacks by one group of men on another, and vice versa, Shazeer said, “Man has been killing each other since the beginning of time. There has never been a time when men have not killed other men. It is usually in the name of religion, country, caste, or tribe. Man will always find a reason to kill other human beings. But what is most disheartening is that those who suffer are not involved in the battle. They are the ordinary people who just want to get on with their daily lives, like having a job and looking after their family. They want a normal life.”

(Published in Onmanorama.com)

February 7, 2021

The mysterious death of an Indian sailor; crew members report ghostly disturbances

By Shevlin Sebastian

On January 29, sailor Bhupendra, 24, was having lunch with his colleagues Devadasa Shivaraya and Cheekati Gurumurthy in the mess room of the tanker MT Sea Princess, as it sailed in international waters off the coast of the United Arab Emirates. The 28-year-old ship was on its last journey; it was headed towards the ship-breaking port of Alang in Gujarat.

After lunch, the trio went to do different tasks. At 4 p.m., fitter Dhananjay tried to locate Bhupendra, since they worked together in the galleys, but couldn’t find him. So Dhananjay went to Bhupendra’s cabin but he was not there. Then he went to the bridge. Again, Bhupendra could not be found. At 4.40 p.m., an alarm was sounded.

All the 12 crew members took part in the search. And it was only at 5.15 p.m. that Gurumurthy found Bhupendra hanging in the boiler room. When they brought the body down, Birendra had no pulse. At 5.45 p.m., Bhupendra’s body was shifted to the cold room.

The authorities were informed, including K Sreekumar, the Inspector at Chennai of the International Transport Workers Federation (ITF).

Since the death of Bhupendra occurred in international waters, the authorities at Sharjah were reluctant to allow the ship to come back. But when a request was made by the Indian Embassy and the ITF, the ship was allowed to return. Thereafter, a postmortem was done in a hospital at Khor Fakkan and the body now remains in the mortuary. The ITF is awaiting the release of the police report.

“From what I heard, Bhupendra had completed a nine-month contract, and stayed on for another three months, because the company, Prime Tankers did not let him off despite repeated requests. But the company said since the ship was going to Alang, they told Bhupendra to continue till he reached India,” said Sreekumar.

It seemed he felt depressed by these repeated rejections and committed suicide. Interestingly, Bhupendra did not leave behind any suicide note. This was confirmed to Sreekumar by the captain Nirmal Singh Brar (the captain was unavailable for comment, citing insufficient data on his mobile phone).

Arun Som, the uncle of Bhupendra, disputed the fact that his nephew had committed suicide. “He told us he had booked a flight ticket from Sharjah to Chandigarh on January 25,” said Arun, by phone from Bhupendra’s hometown, Khera, about 35 kms from Meerut.

From there, Bhupendra was supposed to travel by taxi for the six-hour journey to his home. But from January 25, onwards, his mobile phone remained out of range. But Arun was not worried. On the seas, for days at a stretch, there would be no network coverage, so Bhupendra could not call home.

At 10.30 am, on January 30, Chief Engineer Sushil Kumar called Bhupendra’s father Suresh Kumar and told him his son had passed away.

Arun said, “Why did they take so long to inform the family, especially when he had died the previous afternoon? We cannot believe Bhupendra has committed suicide. He was a peaceful and simple boy, and enjoyed life.”

The parents have been devastated. They have not eaten at all, including Bhupendra’s elder brother, Rajinder, 27, who is a farmer like his father. “The village of 10,000 people, who are predominantly sugarcane farmers, have been deeply distressed by what has happened,” said Arun.

The family is in touch with the Indian Embassy since they have not received the body.

“There is something fishy which has happened,” said Arun.

The ship which used to transport bitumen and asphalt, is at present docked at the Alpha anchorage at Khor Fakkan, near Sharjah.

Meanwhile, crew members told Sreekumar there have been some unnatural disturbances at night. Doors are being banged and the portholes are being shaken. They fear it is the ghost of Bhupendra. “The crew is going through a lot of stress,” said Sreekumar. “I don’t know how much of this is true, but the weather is calm at Khor Fakkan.”

The ITF is preparing a report stating that owing to the mental stress caused by the captain’s refusal to release Bhupendra, he committed suicide. So, Prime Tankers is liable to pay compensation to Bhupendra’s family.

-----------

A helping hand

The Indian branch of the UK-based Sailors Society is in touch with Bhupendra's family and providing necessary support to them. In the event of a crisis, seafarers and their families can contact the society’s round-the-clock helpline, 022-48972266. They can receive advice in a variety of languages including Hindi, Tamil, Gujarati, Telugu, Bengali, Malayalam and Odia.

The free helpline is staffed by a team of professional psychologists, chaplains, maritime lawyers and social workers.

January 20, 2021

The Brand New You

Entrepreneur Nilufer Sheriff talks about the popular Hair Fair cosmetology clinics that she runs in Thrissur, Kochi and Kozhikode. She also recounts the story of her life

Pics: Nilufer Sheriff; Nilufer with her husband Rohit Vijayan. Photos by Unique Times

By Shevlin Sebastian

Whenever a leading Mollywood star Kalpana (name changed) enters the Hair Fair Clinic at Thrissur, owner Nilufer Sheriff has a look of anticipation. “She’s the easiest and most intelligent client that I have,” said Nilufer. “When you talk to clients about certain treatments, they tend to double-check with others. I can understand why. But with Kalpana, she has this ability to trust you completely. She makes you feel that what we are going to do is right. So she says, ‘Do it’.”

Before she comes to the clinic, Kalpana is clear in her mind about the treatment she is seeking. For actors, Nilufer says the doctors can change the jawline, lift the cheeks, pull up the eyebrows, and sharpen the nose. “In a way, we sculpt the face,” said Nilufer. “So, when Kalpana comes, she clearly states what she is looking for.”

Once, Kalpana said she was about to embark on the role of a village woman. So, she did not want sharp features. All these changes are temporary. “A change in jawline lasts a year,” said Nilufer.

Since actors rely on their expressions so much, Nilufer does not use Botox in the central part of their faces. However, in the other sections, she uses a technology which reduces the strength of the Botox. When it is administered into the skin, the pores are removed, but not the wrinkles. “It will not freeze the expressions,” says Nilufer. “If needed, we can also dilute it in a particular proportion for the wrinkles to be removed.” One other positive is that the face gives off a radiance.

When asked whether Botox is safe, Nilufer said, “Of course, it is. I have been using Botox for years. It is not just a corrective, it can be a preventive too. My lifestyle is very stressful, so wrinkles can come up, so I have used Botox and that is why my face has remained unlined.”

Nilufer is the best advertisement for the work done in her clinic. She has done three nose jobs or rhinoplasty, liposuctions, and chin extensions. When lines appear on her face, she inserts a thread and lifts the skin. She has healed her hair.

“I had very little hair because of genes,” she says. “My paternal grandmother had very little hair. Till three years ago, I used wigs and extensions. But throughout that time, I was learning the process of growing the hair.”

Now Nilufer has lush and long hair. Incidentally, her Hair Fair clinics -- in Thrissur, Kochi and Kozhikode -- are well-known for its hair treatments.

Nilufer says the one reason she tries out these things on herself is because if it does not work for her, it means it will not work for her clients. In a way, she is a guinea pig.

Asked whether people have an inferiority complex regarding their looks, Nilufer says, “Of course, they do. Even the most beautiful people have insecurities. Some clients have told me that when they don’t look their best, it affects their confidence and ability to perform. It can also affect their marriage and career.”

As for the clients, the men are at 51 percent while the women are at 49 percent. Most of the men come for a solution for their hair fall. “They are very conscious about their looks,” says Nilufer.

For a 45-year-old male actor who has crow’s feet around the eyes, Nilufer does not remove all the wrinkles, because the audience will notice it immediately. Instead, she softens the wrinkles. “I will just remove the harshest lines,” she said.

One popular actor requested that he should not be made fair because the Malayali audience does not like fair actors. Apart from many top Mollywood stars, Nilufer has Tamil and Telugu actors who are clients, too, apart from leading politicians, corporates and businessmen.

As for the most-asked treatment, she said, different clients have different needs. An NRI woman will ask for laser hair removal or facial contouring. A teenager will ask for a product to get rid of her acne.

When a client comes in, a team of experts looks into the quality of the skin, diet, lifestyle, and hormonal balance before suggesting the treatment.

One of her oldest clients is 79-year-old Susan Chacko, who lives in Thrissur. Her husband is a doctor while she is a homemaker. Her children live abroad. “Susan aunty does yoga and exercise, and eats right,” says Nilufer. “She has ensured she received the right treatments, so she looks pretty even now.”

As to whether Malayali women look after their faces and skin, Nilufer said, “Not really, even though we have great skin. Malayalis have a high degree of immunity, unlike Westerners, whose skin ages fast -- they develop wrinkles, freckles, and splotches. Malayalis don’t have those problems.”

The problem is the diet. Most people eat fried or junk food. “Malayalis rarely have broccoli or organic foods,” she said. “And too many foods have pesticides in them. That can affect the skin.” There are lifestyle issues: high stress and lack of exercise. This can make you age fast.

At Hair Fair, there is a range of treatments and products, which are offered. The prices start at Rs 550 and can go up to Rs 2 lakh.

A powerhouse

In person, at her mother’s spacious apartment on Marine Drive, Kochi, Nilufer comes across as strong, forceful, articulate and focused. She is the only child of Muhammad Sheriff and Nimmi.

Sheriff, a graduate of the Indian Institute of Technology, Chennai, is the Executive Director of the Dubai-based Tecton Construction, a desalination, oil and pipeline company. They have executed projects in Qatar, Bahrain, India, Europe and the United Arab Emirates. He also owns an export-trading firm in Africa and Prime Inspections in Italy.

Nilufer grew up in Thrissur with her mother, Nimmi. With the encouragement of her husband, Nimmi began a beauty salon called La Femme in Thrissur in 1988. This remains successful. On an average, they do the make-up for 100 plus brides every month, especially during the wedding season.

When she was in Class six, Sheriff told Nilufer about a toxin, which helps to remove wrinkles and makes people look younger. Later, when she grew up, Nilufer realised it was Botox. “That was the time there was no Google and the Internet but my father was already aware of all the new technological advancements,” says Nilufer.

One day, when Nilufer was in Class 9, Sheriff showed her a magazine in which there was a write-up of the Vandana Luthra Curls and Curves company. “There will come a time when doctors will be handling these salons,” he said.

Her father had sketched out the career plan for Nilufer from the beginning. “The beauty industry will never suffer from recession,” he told her. “Everyone wants to look their best all the time.”

Nilufer did her MBBS from Rajiv Gandhi University in Mangalore. In 2005, she got married to a surgeon named Shazeer Majeed. In 2007, she became a mother to a boy named Rayn (which means, ‘Gateway to Heaven’ in Arabic). However, her marriage did not work out. Thereafter, after her graduation, she worked in Jubilee Mission Hospital and the Trivandrum Medical College.

In 2014, Nilufer went to do a one-and-a-half-year course in dermatology from St. John’s Campus of King’s University in London, and internships in cosmetology clinics in New York and Los Angeles. This was followed by a course in cosmetology from the American Academy of Dermatology. She also worked in Singapore under Dr Dylan Chau.

It was while working in a Beverly Hills salon that one day, Hollywood star Jennifer Aniston walked in. Jennifer was wearing huge sunglasses, with a grey top and a black cardigan, topped up by a huge sun hat. “She slipped in quickly so that people would not recognise her,” said Nilufer. “Jennifer had natural beauty.”

Start of Hair Fair

After her studies, Nilufer returned to Thrissur and began working in her mom’s salon in the reception to get an idea of the beauty enquiries of an average Malayali. Thus far, her knowledge had been only of Western clients. Thereafter, she took some space there. She started with peeling and facials.

Nilufer’s first client was a senior Thrissur Corporation official. Thereafter, many clients followed. So, she decided to start her clinic in 2016. And it has laser technicians, dentists, Ayurvedic experts, plastic surgeons, dermatologists, medi-facial experts and cosmetologists. They have their production line of creams and medicines and an export division.

Personal life

Two years ago, Nilufer married the 6’2” Rohit Vijayan. They met through a mutual friend. And love blossomed. They got married at the Shangri-La Golf Resort & Spa, Hambantota, Sri Lanka on November 16, 2018, in the presence of 120 friends and relatives. Among the guests were Mollywood stars Indrajith, his wife Poornima, Bhavana, and director Geetu Mohandas.

Asked about the qualities of her husband, Nilufer says, “Rohit is well-behaved and expresses his opinions in a forthright manner. He dresses very well. And he is a gentleman. We have similar perspectives on life. In short, he is a great package.”

A year ago, Rohit hit the headlines when he gifted a Lamborghini sports car, valued at over Rs 4 crore, to Nilufer.

She loves to drive. “There is such an adrenaline rush to drive at high speed,” says Nilufer. “It is similar to playing a video game.”

Kochi-based Rohit is a second-generation seafood exporter. Thanks to Rohit, Hair Fair has expanded to different cities. “Hair Fair could not have grown without Rohit’s administrative expertise,” says Nilufer.

But it is not all work and no play. To destress, once a year, Nilufer goes underwater diving. “It is a beautiful experience when you go down and see the beauty of the ocean,” she says “The experience is meditative. When I come up, I feel lighter and experience a clarity of mind. There is a peace within me.” She has gone diving in the Maldives, the Great Barrier Reef in Australia, and Mauritius.

Every year, she travels to London and Singapore for work and recreational purposes. She goes once a month to Dubai where her son is studying in a school. And she enjoys spending time with her father.

For Nilufer, her father is a superhuman. “He has great vision and knowledge,” she said. “Anyone who talks to him comes away enlightened. My father is a man of unconventional thinking, even though he comes from a conservative Muslim family in Kodungaloor.”

She recalls that, as a child, when she went to a shop, she would ask her father to buy her a gift. But he would tell her to earn it. So, she would have to wash the car for a month to earn her pocket money. Sheriff would give her memory tests. He would make her stare at the garden for a minute. Then he would turn her around and ask her to tell the number of flowers and plants. “I learnt how to look at life with a wide vision,” she says.

As for Nilufer, her dermatology job is a passion,” she said. “I am doing it not just to earn money but for the joy of it. My husband and father have made enough money for me to live comfortably.”

When asked whether she is happy to be living and working in Kerala, Nilufer shakes her head and says, “No. The lifestyle is poor. We deserve good roads. All of us are paying road taxes. There is no support from the government or the society for an entrepreneur like me. If I go to the health department or a medical association and suggest some ideas, they are not receptive. They fear change. And we have an out-dated education system. We rely too much on by-rote learning. We should have a research-oriented system.”

One day, she plans to open an educational institute which will follow world-class systems of teaching. “That is my dream,” she says.

As for the status of women in Kerala today, Nilufer said, “The position has improved a lot. There are a lot of strong women around, whose voices are being heard.”

Finally, on whether the children of successful parents will do well in life, Nilufer said, “Not necessarily. The young generation is into the ‘quick money’ culture. They are very social media-driven. They feel the life they see on social media is the actual reality. They find it difficult to build something from scratch. Our parents, on the other hand, really worked hard. As for my generation, we work smartly, because we have technological access. But in terms of sheer physical effort, our parents were far ahead. God bless them.”

(Published in Unique Times)

December 31, 2020

Talking about dogs during the COVID times

Every day, at 6 p.m., I set out for a jog. In Mumbai and Delhi, during these COVID times, it may be unthinkable. But in Kochi, I can do so, as long as I stay away from the main roads. The view in the suburb where I live is soothing: large trees with overhanging branches. Houses with gardens in front. A few elderly people chat with their neighbours in front of their houses, as the sun sinks into the horizon.

For me, there is another group that I see every day. And these are the dogs.

As I run down Pratibha Bylane, within 100 metres, I meet the first dog. Or rather, I hear it. An Alsatian, in the evening, the owners put him into a kennel which is near the road. The moment he sees me, he barks loudly. I think to myself, ‘This dog has seen me every day for over 100 days, and yet, he’s still barking at me.’

Further down, a brown dog, who is a regular on the road, is ambling about with a puppy following it, wagging its tail. At one moment, the puppy nuzzles against the mother’s body. It is a happy bonding even as the mother casts a wary eye at me.

Soon, I turned right into Pavoor Road and ran for 200 metres. Then I meet the next dog, a white-skinned one. This dog has the most peaceful eyes I have seen in a long time. He does not seem to have any negative thoughts. Placid, he sits with his paws stretched out on the pavement, looking at me. In all these months, he has never barked at me. He is in some sort of nirvana.

After I finish my run, my face streaming with perspiration, my T-shirt drenched, I cross the main road and go for a walk in Sangamam Lane. This is a silent locality, where there are many houses next to each other, but with not much of a space in front.

But I have to brace myself. As I cross one house with a low iron gate, two dogs bark hoarsely when they see me. They seem to be furious. They keep barking till I go past. This happens all the time. A little later, at a pink-coloured house, a black dog stands behind a gate, and peers outside through a gap in the railing. This dog has very sad eyes. He looks at me and remains silent. But there are days when he too lets out a bark.

Then I turn right and enter the long and straight section of Pipeline Road. There is very little traffic. On the right side is Maria Park. It has huge trees and plants growing all over the place. A green-coloured building looks abandoned. Branches of the trees seem to enter the windows. On a large white board, there is a forbidding message in black letters: ‘Trespassers will be prosecuted’. It has been put up by a Mumbai-based real estate company.

About 600 metres later, on the left side, there is a small restaurant. About six people can sit inside. In front of it, a man is selling lottery tickets sitting on a red stool, the tickets placed neatly in rows on a wooden board in front of him. Next to him, another man is selling fish placed on a wooden board.

It is here that I see two brown dogs. Both are small. They are always playing with each other. Sometimes, they mock-bite each other’s body.

Are they siblings, or husband and wife? Who knows? But they live in the present moment and are happy.

I remember how one of the dogs followed a man who carried a plastic packet filled with potatoes, cabbage, beetroot and beans. The smell seemed to excite the dog. His nose kept twitching as he went behind the man for a long time.

What I have noticed is that dogs who live inside houses always bark at strangers. I guess those who have the security of living with owners have the freedom to bark. They are also showing their owners they are always alert. On the other hand, the roadside dogs are mostly quiet. Those who live on the streets have to ensure they don’t antagonise the pedestrians as well as the residents.

Like, in human life, the affluent man, with his money and contacts, can afford to be in-your-face rude, while the beggar has to make sure, he is almost blending into the surroundings so that he does not attract the ire of the police or the local people.

However, while observing these dogs, I have realised one thing. They are bored out of their skulls. There is nothing exciting to do. They do not seem to have any purpose or goal. Their only aim every day is to fill their stomachs. After that has been done, you can see them lazing about, doing nothing. They are in a state of high idleness. They yawn a lot.

What is the meaning of their lives? Of all animals? And birds?

Or are they not supposed to have any meaning to their existence?

Only humans do?

I don’t have the answers.

Do you?

December 27, 2020

Evaluation

By Shevlin Sebastian

A memory came

Of many years ago.

I must have been in

Class 7 or 8.

I was lying in bed

In the ancestral home at Changanacherry,

Had come there from Kolkata

for my summer vacation.

In the next room,

My mother and several sisters-in-law

Were chatting.

About their children

The chatter woke me up.

My mother said, “My son is quiet and well-behaved.”

Another woman said, “My son is the opposite.

Restless and mischievous.”

The other mothers joined in.

Talking about their daughters and sons.

Today, when I remember this,

I think to myself,

From the time we are born,

Till the day we die

And even after,

People are always evaluating you.

First, it is our parents,

Then our siblings, friends and relatives.

Teachers and classmates.

This carries on

In college,

Professors and fellow students,

The University Board

All measuring your performance,

Ready to congratulate or condemn you

When you go to work.

Bosses, colleagues, subordinates,

The management

All assessing your work,

And your character

From morning to night.

And now since it is work from home,

From night to morning, too.

In the meantime,

Your wife and children

Are also evaluating you.

In this pandemic world,

They think: does the old man have the cash

To meet our expenses?

You go to the hospital,

The doctor evaluates you

Not to forget,

At different times,

The dentist, the ophthalmologist,

The dermatologist,

The gastroenterologist

The cardiologist.

Depending on which part has broken down.

You feel like screaming

God, is there a single moment when I am

Not being assessed.

God is the wrong person to ask.

Because He is the master of

The appraisal.

When you die, he is busy peering into your soul.

Is he a good or a bad guy?

Should I send him to heaven or hell?

And then you resign yourself

To the fact.

The appraisal will never stop.

And when there is an unnatural death,

Then it is the turn of

Human beings to cut open your body

And poke about,

Looking for this and that.

A post-mortem.

Ha, ha, no respite at all!

(Published in HelloPoetry.com)

December 18, 2020

The passing

A poem about old age

By Shevlin Sebastian

One by one,

People of my dad’s generation

Are passing away.

A call came

At 9 a.m. on a Sunday

An old family friend,

Died, in his nineties.

Cause of death: old age

He was a morally upright,

decent and humble person

Soon, a photo of the deceased,

Arrives on WhatsApp

Lying still on a hospital bed.

The wife stands nearby

Gazing at the husband.

Fingers pressed against

Her cheeks.

She is mourning two deaths

The physical death of her husband

And the death of a marriage of several decades.

What now?

There will be no one to share the days and nights.

The children are scattered all over the world.

The life alone,

Is terrifying at the best of times.

More so, during the end stages of life.

The husband had the company of the wife

When he passed away

But what about the wife?

Who will give her companionship now?

Her children, perhaps.

The cycle of life

Spring, summer, autumn and winter.

No matter how powerful you are.

Or how rich.

Or how charismatic

The ascent is always followed by a descent

To the graveyard

Or the crematorium.

Depending on your religion.

You have to say goodbye one day.

But it’s not easy… this last lap

To extinction.

Many suffer prolonged agony.

Some lose their minds

To dementia and Alzheimer's.

A few have their bodies ravaged

By cancer.

Many have regrets

About the actions they took

But it’s too late.

An act can never be undone.

It’s like a word which comes out of the mouth.

You cannot pull it back.

So, forgive yourself

And forget about it.

It’s also frightening to behold

That one day, we too

Will have to go through the same process.

A friend said, “Let’s live,

As if each day is going to be our last.

And cherish it to the fullest.”

Easily said,

But so difficult to implement.

The human mind

Slides into negativity so easily.

And so persistently.

The fight between light and darkness

Occurs at every moment.

This battle will go on.

Till the exhausted heart gives up

And stops beating…

(Published in Poetry Soup.com)

December 9, 2020

All that jazz

Dance pioneer Astad Deboo, 73, passed away in the early hours of Thursday, December 10 at his home in Mumbai, after a brief illness.

I had the good fortune to meet him while working in Mumbai. The following story highlights his work with deaf students.

Maestro Astad Deboo says deafness is not a handicap for the dancers of the Clarke school

Pics: The students of the Clarke School; Astad Deboo

By Shevlin Sebastian

As with all Astad Deboo productions, the moment the 'Contrapositions' show by dancers of the Clarke school for the deaf ended at Mumbai, there was a stunned silence. And then the applause rolled down in waves. Later, the dancers stood upfront so that audience members could come and meet them.

One elegantly clad lady made her way to the front and quietly touched the feet of the dancers. “Would you believe it or not but she was none other than Helen, the grand lady of dancing," says Deboo. "Such humility! But the dancers did not who she was.”

Deboo has been working with deaf children for the past sixteen years in places as diverse as Hongkong, Mexico, USA and, of course, India.

And it all began rather casually. On a visit to Kolkata, he told Zarine Choudhury, the artistic director of the deaf company, Action Players, “Why don’t you take the advantage of my being here and do a workshop for the kids?”

It was only after the third year that both Choudhury and Deboo felt that it was possible to create a full programme, half dance and half mime. And even though you see perfect synchronicity between the dancers during a programme, there is a lot of sweat, tears and frustrations behind the serene display.

“The way I teach is that they all have to count in their heads… 1, 2, 3, 4. All have to count in the same rhythm, to be in sync.” Mostly, the dancers learn through sign language, body gestures and lip-reading.

In Kolkata, they lip-read in English, in Mexico, it is in Spanish and places like Bhopal, it is Hindi. And it is not just a one-way process. Whenever he works on a new composition, time and time again, he would come to a dead end. Then he would tell the dancers, ‘Okay, show me what you have in your repertoire.’”

So they would show something and he would try to see whether he could incorporate it in his choreography. “It is a creative collaboration between the girls and me,” he says. But underneath the affability, he is a hard taskmaster. “I am patient but after that, the girls get the fireworks,” he says. “When they cry, I say, ‘I am not going to melt, so there is no point.’ I encourage them but I don’t say ‘Wah!’ because I want to keep pushing them. Because it is only then that they will get better and better through every performance.”

And, like in all dance troupes, he also has a diva. “She is very talented and she knows it,” he says, with a smile and shaking his head from side to side. “From time to time, she throws a tantrum in her coterie.” The youngest girl in the troupe is a thirteen-year-old and the diva, who is 22, decided to take her on as a protégé.

“One day after a show, I saw the younger one massaging the feet of the older one. I said, ‘What nonsense is going on?’ And the diva replied, ‘My leg was paining and I just asked her to massage it.’”

And like ordinary teenagers, they also love to receive accolades. “Every morning, if we have a performance in a city, they will say, ‘In which newspaper are we in today?’ I try to make sure everybody gets an original copy. Sometime ago, there was an article in the newspaper and I had only one copy. And the diva said, ‘I want the original’. And we had to remind her that there was only one copy and she would get a photocopy like the others.”

Asked about his plans, Deboo says he would continue to work with the Clarke School dancers. “We are going for a tour of Singapore and Malaysia and following that, we will be doing several shows in India which will keep us busy till the end of the year. And then there is a commission for the inauguration ceremony for the 2007 Winter Olympics for the Deaf in Salt Lake City.”

(Published in The Hindustan Times, Mumbai, December 22, 2005)

#AstadDeboo #Dance #ClarkeSchool #ZarineChoudhury

December 8, 2020

Crossing Boundaries

By Shevlin Sebastian

It was past midnight. Ten-year-old Roshan lay, his right cheek pressed against the pillow, between a cousin Tony and an uncle Satish at his home in Calcutta. His parents were in another bedroom. Yellow light lit up the upper part of the room, thanks to the lamppost on the road. The only sound was the trembling of the blades of the fan above him.

Tony raised his head to look at Satish. He slept facing the wall. So Tony relaxed. He sat up, leaned to his right, and pulled at the pyjama cord of Roshan. It loosened. He waited. There was no movement on Roshan’s part. Tony pulled down the pyjama by gently lifting Roshan’s waist. Again he waited. The boy made no movement.

But Roshan was wide awake, even though his eyes remained closed. He felt exposed because of the breeze from the fan; it raised tiny goose bumps on his upper thighs. But he also felt nervous. He knew something forbidden was about to take place.

He sensed some movement behind him, and then Tony raised his left leg, inserted his penis and brought the leg down. It remained between Roshan’s thighs. It was hot and throbbing. Again, Tony paused to see whether there was any reaction from Roshan, who remained still. Tony pressed Roshan’s thighs together and pushed his penis forward and backward, trying to simulate a vagina.

There was an urgency in Tony’s grip on Roshan’s leg and the first signs of air rushing out of his mouth. Roshan felt he was on the edge of a cliff. All he could feel was this thing moving and getting bigger, between his legs and Tony’s grip on his thigh. The movements became faster. Tony slipped into another world.

After a few minutes, Roshan could sense the organ expanding followed by several contractions. And then a stillness. Then a soft and satisfied moan, as Tony withdrew. Roshan did not understand what had happened.

Then Tony lifted Roshan’s pyjamas and re-tied the cord. Roshan sensed Tony’s body turning over to the other side.

Roshan lay still for several minutes, not wanting to give the faintest hint he was awake. Soon, he heard a soft snore, and realised that Tony had sunk into a deep sleep. In the darkness, Roshan reached out and touched the sheet beside him. His left hand came across gooey stuff. Roshan rubbed his hand against another part of the sheet and drifted off to sleep.

Tony grew up in Margao in Goa. His father — Roshan’s Dad’s brother — worked in the Indian Navy. Tony got a job as an accountant in a biscuit-making firm at Calcutta. He was 6’ tall, but on the plump side — a slight paunch fell over his belt. But, at 24, he remained frustrated. In the early 1970s, India was a conservative place. There was little chance of an interaction between the sexes, let alone the thought of having sex. For that, you had to go to the red-light district of Sonagachi. But Tony knew there was a risk of contracting a sexual disease.

The next morning, when Roshan opened his eyes, Tony and Satish were not in the room. He glanced at the place where the sperm had fallen and, sure enough, a yellowish stain could be seen but it was not noticeable, unless you were looking for it, because of the maroon colour of the sheet. Soon, Abdul the servant would come and place a counterpane over the two beds. At breakfast, Tony, dressed in a long-sleeved white shirt and black trousers, and shining black shoes, smiled at Roshan.

He said, “How is school?”

Roshan said, “Fine.”

Roshan realised that Tony felt sure the child did not know what had happened the previous night. ‘He must be dumb,’ thought Roshan. The boy drank his glass of milk, and ate his omelette and toast, using a spoon. His mother helped him put on his white shirt and grey shorts. Then she combed his hair, left to right, while holding his chin with her left hand. Soon, he was off to school.

For the next few months, it continued like this. After midnight, Tony pulled down Roshan’s pyjamas, placed his penis between the boy’s thighs and had an orgasm. Roshan thought of telling his parents but couldn’t muster up the courage.

Anyway, relief came when a marriage proposal came for Tony. The girl, Lisa, a daughter of a wealthy businessman, lived in California. Tony said yes because he always wanted to go to the United States and what better way than by marrying a citizen? And so Tony married Lisa and moved off to California. Roshan was relieved that his nights had become peaceful. Now he slept on one bed and Satish on the next.

However, predators remained close by. In school, the English teacher. Fr James told him to come to his room with his English composition paper after classes concluded for the day. Roshan had got five out of ten, which was better than many students. So it puzzled him about why the priest had called him.

Roshan knocked on the door. Fr James opened it. He smiled. The priest had large eyes, which had a hint of lasciviousness.

When Roshan entered, Fr. James took off his white cassock and placed it on a hanger. Underneath Fr. James wore khaki Bermuda shorts and a brown T-shirt.

“Come, sit on my lap,” said Fr. James.

Roshan was too timid to say no.

He sat on the left knee. Fr. James said, “You have to improve your grammar.”

As the priest leaned forward to look at the paper spread open on the table in front of him, Roshan fell between the thighs of the priest. The boy realised Fr James had not worn underwear. He felt the priest’s penis press against his lower back. Soon, it became hard. The priest pressed harder.

But Roshan was lucky. The priest did not do anything more than that. After half an hour, Fr James allowed him to leave. When he stepped out, he saw Shyamal Mitra, a classmate of his. He wore thick-lensed spectacles. They were the smallest boys in the class.

The next day when Roshan asked Shyamal what had happened, his friend said that Fr. James took out the boy’s penis and stroked it forward and backwards.

He kissed it many times.

Roshan decided that if Fr. James called him again, he would tell his parents about what had happened on the first visit.

Shyamal was not upset.

“I liked it,” he told Roshan.

Roshan did not know what to say. He knew it was wrong.

As for the priest, he knew that one complaint would destroy his career. So, he had to be very careful. He realised Roshan did not have gay tendencies, but Shyamal seemed okay. Fr James would give him some gifts now and then to keep the boy happy. He came from a lower-middle class family.

Just like Fr. James, whose father worked as an accountant in a small firm. When James turned fifteen, he realised that he liked boys rather than girls. He had his first sexual encounter in school when Mark, a gay like him, took him to the back of the building in the evening, and jerked him off.

James remembered it as painful as Mark pulled too hard. He was not able to come. Mark pressed down on the shoulders of James, who sat on his haunches. “Suck,” Mark whispered as he opened his trousers. For James, it was novel and exciting — the musky smell of the penis, mixed with the sweat, and the way it grew inside his mouth. James moved his mouth forward and backward.

Expectedly, Mark came. James swallowed the sperm and wiped his lips with a handkerchief. Thereafter, James sneaked into the school toilet and masturbated silently, his breath going in and out with a rising speed.

After they parted, Fr. James pondered over the experience. And he enjoyed the throbbing penis in his mouth. He decided he would become a priest. This had been a vague thought, but now it became an earnest desire. There was an advantage of joining the celibate Catholic clergy; nobody would ask him why he was not getting married. He could always be with gay priests. Or seduce children. Fr James did not call Roshan to his room again. Shyamal went often, but Roshan did not ask him about it. He did not want to know.

At home, his mother said a new servant, Freddy, had come from Goa. He slept on the floor near Roshan’s bed. The 25-year-old wore sleeveless banians, so Roshan could see the bulging shoulder muscles. But he spoke in a quiet voice. So Roshan liked him. They became friends. Thanks to his presence, his parents and Satish went for film shows at night.

One night, when they had gone out, Roshan was lying in bed. Freddy lay on the floor next to him. Freddy sat up and told Roshan to come to the edge of the bed. The boy did so. Then Freddy took Roshan’s hand and placed it on his penis. Roshan’s eyes bulged out, to see how thick it was. He caught it like you would hold a tennis racket. Roshan sensed the trembling in his hand. He felt less scared than when he was with Fr. James. And Shyamal’s reaction had emboldened him. There was nothing to be afraid of.

But soon, his Jesuit upbringing — Roshan studied in St Xavier’s school — reared its head. He pulled his hand away, fell on to the bed and rolled to the other side. Freddy did not press him. He switched off the light.

After a while, Roshan went to sleep. Freddy pleasured himself to an orgasm and used tissue paper to remove the sperm from the floor.

—————

Fifty years have passed since that moment. Roshan, who had a shaved bald head now, stood in the verandah of his fourth-floor apartment in Calcutta and smoked a cigarette. He exhaled in a lengthy breath, to lengthen the pleasure. It was a leafy neighbourhood — trees on both sides of the road.

The road remained deserted even though it was a Monday evening, thanks to the coronavirus. Roshan was in isolation at home. The entire world was in isolation at home, he thought.

It gave him the opportunity to journey back into the past. And people like Fr. James and Freddy came floating to the surface of his mind. He had heard that Fr. James had retired a decade ago. Nobody had filed any child abuse charge against him. ‘A smooth operator’, thought Roshan. As for Tony, he died in his thirties, in a car accident in Los Angeles, and left behind a wife and daughter. Roshan did not know where Freddy was. That was the way with servants. Nobody knew where they went and what happened to them. Did he marry and have kids? And was he doing well? The middle class only kept track of their middle-class friends. They did not care about the poor but idolised the rich.

As for Shyamal, he became a well-known theatre artist, and an avowed gay.

Roshan knew that he suffered far less molestation, as compared to so many others. His wife, Srimati, so stunning with her porcelain skin, grey eyes and sumptuous breasts, had been a victim.

She slept next to Kaushik, a cousin, when they were teenagers during a sleep-over. Kaushik grabbed her breasts, tried to force-kiss her and got on top of her. There were other cousins in the room. But it was pitch dark, so nobody saw anything. Srimati whispered, “I will scream. I will tell your parents.” But he just covered her mouth with his left hand, pushed up her skirt, she was not wearing a panty, and pushed himself in. And he remained inside her for a long while, almost prompting Srimati to vomit.

It scarred her. For years afterward, when she was in bed with Roshan, she would kiss for a few seconds and break away. Unpleasant feelings arose in her like bile from her stomach. She trembled and tried to shake off the terror and helplessness she had felt all those years ago. The mood collapsed. Roshan took her to a psychiatrist. Many sessions took place. She wrote about the experience on white sheets of paper. It went to several pages.

Step by step, the poison seeped out of her mind and body. One reason Roshan remained patient was because he loved Srimati.

Her beauty enthralled him. She was the only child of a Bengali professor and an English writer. They had met in college in London, fell in love, got married and returned to Calcutta.

For a Goan like Roshan, to get a goddess like Srimati was unbelievable. Over the years, she unlocked her sensuousness. And discovered the tigress within. Roshan remained a grateful beneficiary.

Srimati never moved against Kaushik. It remained their one and only encounter. He stayed away from her. They grew up. He became an architect, got married, had two girls and lived in New York. Did well for himself. A house in the suburbs and a BMW in the garage.

Roshan heard Srimati’s story many times in other lives. As a creative head of an advertising company, he had several women employees. Over time, they told him their tales of abuse — the culprits being family members, or strangers, on planes, trains, buses and trams, on the dance floor, and one even said, her own father was the abuser. Another said it was her grandfather.

One colleague said that when she was on an aisle seat in a crowded bus, people packed like sardines in a tin, a man took out his penis and rubbed it against her shoulder. She stood up and slapped his face. Her hand stung from the impact. She had to shake it several times.

As for the offender, he pulled in his penis, pushed himself through the passengers, ran to the entrance, pulled the chain, jumped out and fled. A vanishing act at Superman speed.

So, with their shared history of abuse, Roshan and Srimati vowed that they would protect their children, two girls, at all costs. So, they did not allow them to spend the night away from them, even if close relatives invited them for sleepover parties with their children. They knew the greatest danger came from relatives.

So imagine Roshan’s shock when, one day, Srimati came and told her that when their 16-year-old daughter had gone to the Quest mall, she moved among a throng of people. And from somewhere, a hand came out, and it went between her daughter’s legs and rubbed her. And the hand pulled away and his daughter did not know who it was. It shocked her and gave rise to unpleasant feelings within her. For Srimati, history was repeating itself. Again, she wanted to vomit. Roshan hugged her and kissed her on the forehead. They remained like this for a long time. Her heartbeat slowed down.

As he stood on the verandah, Roshan realised there was no chance of 100 percent safety. An attack could come from anywhere. Roshan’s only hope for his children — if an attack came, it should not be something horrible, but something mild, although there is nothing mild about molestation.

Maybe, he thought, Indian society should open up. Relations between the sexes should be free. But in a free society like America, there were too many instances of violence against women.

There are no solutions to the tense man-woman relationship, he thought.

Srimati had called out to say she had made the evening tea.

Roshan crushed the stub in an ashtray, placed on a low table, turned and walked into the apartment.

(Published in the Scarlet Leaf Review, Toronto)

October 1, 2020

My childhood friend, a hero

By Shevlin Sebastian

Pics: Pushpita Singh at Wimbledon; Anup Singh with his wife Madhu at a tennis tournament in Florida

On Facebook, some weeks ago, Pushpita Singh, the sister of my childhood friend Anup Singh Rashtrawar, posted a four-year-old memory of her maiden trip to the courts of the Wimbledon tennis championship. As I stared at the photos of the pristine grassy courts, it triggered a memory within me. Of me standing at the courtside of the Calcutta Gymkhana Club to watch my friend Anup swing a racket. There was a huge tree near the court, which provided plenty of shade on hot summer mornings.

Anup and I were neighbours. We were a study in contrasts: he was 6’, I was 5’4”. He was muscular; I was frail. He is a Rajput and I am a Malayali. I have no idea how we connected, but we did.

His dad introduced him to tennis. He became passionate about it and trained diligently. Whenever Anup would have a match, he would take me along, to provide moral support. So I would stand on many courts in and around Kolkata. He was a good player: booming serves, a powerful forehand and a smooth backhand, too. The only problem was Anup’s mind. No matter how well he played, he tended to lose, after two or three rounds. Once, after a match, he told me, “Damn, I snatched defeat from the jaws of victory.”

That summed up Anup’s professional career.

But despite his defeats, Anup was a hero to me. This is what happened: just opposite the club, on Suhrawardy Avenue, there is a slum. Eager boys would stand on the pavement and peer through the railings at the games being played.

One boy would be there, day after day. Anup noticed him. One day, he called him inside. And Poonam expressed his desire to play. By this time, Anup had begun coaching too. So, after the trainees had left, he would call Poonam in and exchange shots with him.

Anup was impressed by the boy’s talent. And desire. He hired him as a ball boy. Soon, Poonam began to get better. He took part in junior tournaments and won a few. Then he moved to the seniors. Again he won a bit. He had grown taller, fitter and stronger. Later,

Poonam got a job in the Railways. He played for them, and later, became a coach. Today, he lives a comfortable life, having got steady promotions in the Railways, bought a flat, and now his children study in English medium schools.

Anup did the same for about fifteen Muslim slum boys. All of them started as ball boys. One youngster was the son of the maid who worked in his house. In later years, Shafiq did so well, as a coach, that his mother could stop working and live comfortably.

Indeed, many of them became coaches and earned a decent living from the sport. And it all began when Anup beckoned a bedraggled youngster to come into the club.

As for Anup, his life changed when another childhood friend sponsored him to come to America. Eventually, he became a tennis coach in America. Today, he works in a millionaires’ club in Florida and stays in a gated community with a Mercedes Benz in his garage.

And throughout these years his giving continued. Once when he was browsing online, he came across a story in an Indian newspaper of a poor Muslim girl in Madhya Pradesh who wanted to study medicine but did not have the money. She had nothing to worry about. Because Anup contacted her, by getting the number from the reporter and is now funding her education. And there are many stories like this. The Silent Samaritan.

But the one big puzzle for me was this: Anup never taught me tennis. And I also never asked him to teach me. When I told him this, years later, when he came to visit me in Kochi, where I earned a living as a journalist, he had a baffled look on his face and said, “Gosh, it’s a mystery.”

True, but I don't mind.

I have gained so much from this friendship.