Leo X. Robertson's Blog, page 21

October 28, 2015

First Draft Anxiety

I am close to over it! All the doubts are

so familiar now. The material doesn’t come at a faster rate than it ever has,

but I expect that. The best quality material, as has been said by many authors,

comes first when you don’t know where you’re going with what you’re writing,

what comes next. Re-framing that as healthy as opposed to anxiety-inducing is a

great idea! I’m about a third of the way through this first draft, I reckon,

and here are some thoughts from my anxiety stream that I have become so

familiar with that I don’t take any of them seriously anymore:

This is the best thing I’ve ever written;

this is the worst thing I’ve ever written; I’m not writing this fast enough; I’m

not taking enough time to consider these sentences; this scene isn’t going to

be long enough; this scene became too long!; writing about this is too

personal: it’s scaring me; writing this stopped scaring me: it’s going flat!; are

you basing this on any kind of fact or is this just your opinion? That has

little value!; this is too factual and not imaginative enough: this is a story,

not an essay!;this scene is too exciting; I’m not using enough fancy words; enough

fancy words? What a stupid thing to think: I’m being too pretentious!; I’m

being too on-the-nose; I’m not hitting the target enough!; I don’t know where

this is going; I know too much about where this is going: it’s not free enough!;

this act isn’t going to be long enough; this act is too long: too many words

before more stuff starts happening!; this character is too close to someone I

know: I need to change it!; this character is too far away from anyone I know:

the guy he’s based on wouldn’t say that!; this story is too similar to stuff I’ve

already written: I’m running out of ideas!; am I sure this scene works? It’s

not like anything I’ve ever written and I can’t think of a writer to compare it

to: that’s bad! That’s good! Is it?!; you started this off based on the work of

WRITER, and now your writing style is diverging too much from theirs for you to

use their typical story structure; you’re imitating WRITER too much! Get off

the rails!; you’re thinking too much about this story when you’re not writing

about it: Hemingway advised against that! You’re going to control it too much and

it will appear quite stiff!; You’re not thinking about this enough when you’re

not writing about it: you’ll return tomorrow and be dead rusty!; there’s too

much dialogue in this scene and not enough description!; there’s too much

description here: we need to get to the dialogue faster!

Given that I write for maybe 1-2 hours a

day I have time to tell myself these things, I don’t know, a hundred times

each, maybe? And how many of them are useful? None. So now I just let them

chatter on behind some door in my head and I can only hear the muffled sound of

them. I’ll bring most of these questions back out during the re-drafting, but

for now the door is shut.

I never used to understand the difference between

first draft mode and editing mode, but the truth is there’s no way to tell a

story what to be until you can see it in its entirety. This is why there’s

always material to cut, because it usually alludes to paths you didn’t end up

taking, or a balance that an earlier scene needs to achieve with a scene that

wasn’t yet written, or a call-back moment that you couldn’t have foreseen including. And there’s nothing

wrong with that: if it wasn’t true, it would probably be a sign that you weren’t

a great writer because you were too afraid to let the material take flight a

bit. That doesn’t mean that the perceived uselessness or amazingness of material

during the first draft can’t still torture you until the story is done.

I have a new mantra much kinder than any of

these: it gets done. Write slow, write fast, write well, write badly: it gets

done. It can all be fixed. Sure it would be easier if you could write better

faster, but if you can’t, fuck it: leave yourself the work to do later. It gets

done. If you can’t tell how long it’s gonna take, certainly no one else can,

which means no one can comfort you about this, but it doesn’t matter. It. Gets.

Done.

October 21, 2015

I Don’t Know 2: Chekhov’s Gooseberries

This is but one example of Chekhov’s

immense storytelling power, the one I thought best suited to “IDK.” In

“Gooseberries”, an old man named Ivan speaks of his brother Nikolai’s desire to

flee the city and buy a farm: “To leave town, and the struggle and the swim of

life, and go and hide yourself in a farmhouse is not life – it is egoism,

laziness; it is a kind of monasticism, but monasticism without action. A man

needs, not six feet of land, not a farm, but the whole earth, all Nature, where

in full liberty he can display all the properties and qualities of the free

spirit.”

Nikolai is given some dashes of telling

characterisation during his pursuit of the farm, such as that “he liked reading

newspapers, but only the advertisements of land to be sold…” We learn how Nikolai

eventually obtained his own farm with the gooseberry bush that was so essential

to him: “[He] married an elderly, ugly widow, not out of any feeling for her,

but because she had money.” Although Nikolai obtains his blissful little

farm-world, his hands are not clean.

Ivan pays Nikolai a visit, and finds that

his brother is still enraptured by gooseberries. Ivan tries one: “It was

hard and sour, but, as Poushkin said, the illusion which exalts us is dearer to

us than ten thousand truths.”

All this rumination culminates in Chekhov’s

philosophical payload: “In my idea of human life there is always some alloy of

sadness, but now at the sight of a happy man I was filled with something like

despair… I thought: ‘After all, what a lot of contented, happy people there

must be! What an overwhelming power that means! I look at this life and see the

arrogance and the idleness of the strong, the ignorance and bestiality of the

weak, the horrible poverty everywhere, overcrowding, drunkenness, hypocrisy,

falsehood… . Meanwhile in all the houses, all the streets, there is peace;

out of fifty thousand people who live in our town there is not one to kick

against it all. Think of the people who go to the market for food: during the

day they eat; at night they sleep, talk nonsense, marry, grow old, piously

follow their dead to the cemetery; one never sees or hears those who suffer,

and all the horror of life goes on somewhere behind the scenes. Everything is

quiet, peaceful, and against it all there is only the silent protest of

statistics; so many go mad, so many gallons are drunk, so many children die of

starvation… . And such a state of things is obviously what we want;

apparently a happy man only feels so because the unhappy bear their burden in

silence, but for which happiness would be impossible. It is a general hypnosis.

Every happy man should have some one with a little hammer at his door to knock

and remind him that there are unhappy people, and that, however happy he may

be, life will sooner or later show its claws, and some misfortune will befall

him – illness, poverty, loss, and then no one will see or hear him, just as he

now neither sees nor hears others. But there is no man with a hammer, and the

happy go on living, just a little fluttered with the petty cares of every day,

like an aspen-tree in the wind – and everything is all right.'”

Realising his own blissful folly, Ivan

compels his young listeners to take action: “"Pavel Koustantinich,”

he said in a voice of entreaty, “don’t be satisfied, don’t let yourself be

lulled to sleep! While you are young, strong, wealthy, do not cease to do good!

Happiness does not exist, nor should it, and if there is any meaning or purpose

in life, they are not in our peddling little happiness, but in something

reasonable and grand. Do good!"”

But will they take his advice?

“Ivan Ivanich’s story had satisfied neither

Bourkin nor Aliokhin… it was tedious to hear the story of a miserable official

who ate gooseberries… . Somehow they had a longing to hear and to speak of

charming people, and of women. And the mere fact of sitting in the drawing-room

where everything – the lamp with its coloured shade, the chairs, and the

carpet under their feet – told how the very people who now looked down at them

from their frames once walked, and sat and had tea there, and the fact that

pretty Pelagueya was near – was much better than any story.”

Much like Nikolai and his gooseberries,

Ivan’s young listeners are exalted by their own illusion. They perhaps feel

indignant: older generations will always lecture the young to do not as they

did. They carry the suspicion that this hypocritical message is delivered with

the intent of denying them their birth-right of peaceful happiness. It seems as

if each generation needs to learn the same lesson about the hollowness of bliss

by repeating the same mistakes. But Ivan does plant a seed: “A smell of burning

tobacco came from his pipe which lay on the table, and Bourkin could not sleep

for a long time and was worried because he could not make out where the

unpleasant smell came from.”

The questions the story raises aren’t

answered: they are articulated through the story and delivered to the reader

for him or her to consider. And yet they are so monumental in size that we

don’t expect the reader to answer the question themselves. This story is the

“someone” with the little hammer at the door to knock and remind us that there

are unhappy people. How much happiness we should have versus how much social

injustice we should find it within our power/responsibility to tackle is

forever unclear. Nowadays we have never been more aware of the world’s social

injustices. The internet is the man with the hammer at the door, but he doesn’t

have Chekhov’s humanity. “FW: FW: Leo: Tell Cameron Ice Caps Can’t Melt Bees!”

Those of us plugged in have no farms on which to hide, and the effect can be

debilitating: surely there is a balance? Everyone requires their dose of happiness

as much as their face-rubbed-into-it-ness, but when, how, where, which, and to

what degree is something I will never know, something Chekhov can’t know, nor

does he expect the reader to know. Is it really true that while social

injustice prevails, happiness doesn’t exist?

Chekhov has successfully reflected life and

the human condition without claiming to know what to do about it, which is the

most intelligent and truthful thing a storyteller can do.

October 14, 2015

“I don’t know.”

I want to discuss the power of not knowing.

Not like Barthelme’s Not Knowing, about the power of writing fiction without

knowing where you’re going, but

the power of delivering the message of uncertainty. This is something that only

storytelling of the highest quality can deliver.

You can spot young-writer-nervousness in

our work’s occasional accidental didacticism or its desperation to reveal the

entirety of something or to right some wrong. In fact, it turns out the most

courageous and the truest and most human thing you can do as a writer is only

reveal what you don’t know and admit that you don’t know it: you reveal the

problem without solving it.

What is IDK? It’s giving a fair and

balanced account of all characters, discursive rather than persuasive fiction,

refusing to point the finger by instead showing how characters point fingers at

each other, empathising as far as is possible with all of them, refusing to

provide a victor or a loser and creating a world full of problems so complex

that they defy resolution. (Likely this has some literary term I’ve never heard

of.)

I have several examples of “IDK” and will

serialise them across “I Don’t Know Month” which starts with this post on

Hamlet today and continues for as long as an I Don’t Know Month does, because

it’s my thing. Any work mentioned contains spoilers. I hope you enjoy these

reflections and please feel free to submit your own, because “IDK” is my favourite

brand of storytelling :)

I

Don’t Know 1: Hamlet

I did begin my own analysis on this but

found the basic effect of Hamlet better summarised by Kurt Vonnegut, so much so

that it’s more or less all that remains! Ah, why say it twice though? :D

“[Hamlet’s]

father has just died. He’s despondent. And right away his mother went and married

his uncle, who’s a bastard.… So Hamlet goes up and talks to this fairly

substantial apparition there. And this thing says, ‘I’m your father, I was

murdered, you gotta avenge me, it was your uncle did it, here’s how.’ Madame

Blavatsky, who knew more about the spirit world than anybody else, said you are

a fool to take any apparition seriously, because they are often malicious and

they are frequently the souls of people who were murdered, were suicides, or

were terribly cheated in life in one way or another, and they are out for

revenge. So we don’t know whether this thing was really Hamlet’s father or if

it was good news or bad news. And neither does Hamlet. But he says okay, I got

a way to check this out. I’ll hire actors to act out the way the ghost said my

father was murdered by my uncle, and I’ll put on this show and see what my

uncle makes of it. So he puts on this show… His uncle doesn’t go crazy and say,

‘I-I-you got me, you got me, I did it, I did it.’ It flops. Neither good news

nor bad news. After this flop Hamlet ends up talking with his mother when the

drapes move, so he thinks his uncle is back there and he says, ‘All right, I am

so sick of being so damn indecisive,’ and he sticks his rapier through the

drapery. Well, who falls out? This windbag, Polonius.”

In attempting to kill his father’s

murderer, Hamlet murders Ophelia’s father: he becomes the thing he wishes to

avenge.

“Neither good news nor bad news. Hamlet

didn’t get arrested. He’s prince. He can kill anybody he wants. So he goes

along, and finally he gets in a duel, and he’s killed. Well, did he go to

heaven or did he go to hell?… I don’t think Shakespeare believed in a heaven

or hell any more than I do. And so we don’t know whether it’s good news or bad

news… There’s a reason we recognize Hamlet as a masterpiece: it’s that

Shakespeare told us the truth…The truth is, we know so little about life, we

don’t really know what the good news is and what the bad news is.”

This dense mixture of action, inaction,

reality, fantasy and whether or not we can with our reasoning divine the

correct action to take and whether or not this action will lead to the desired

beneficent consequences is the stuff of life!

For more info on the shapes of stories from

Kurt Vonnegut, check this out.

More “IDK” next week!

October 2, 2015

On Taking a Break from Writing

When you’re writing a first draft, it’s

true that between 1-2k words daily gets you the best possible first draft. I’m

not comfortable with writers saying their first drafts are shit. I’ve noticed

that I don’t change that much between first and last drafts in order to

confidently call the first draft “shit.” In which case, I don’t easily overcome

the upset of writing something that doesn’t work one day. I’m really supposed

to write 2k words a day for, what, 8-12 weeks it could be? Every day? I don’t

have the mental stamina or objectivity required. I take breaks.

Imagine you wrote 2k a day for 365 days a

year. Were it possible, it would produce an unwieldy amount of writing: when

are you supposed to sit and edit all this stuff you’re making? If writing was

your only job, you could… William Goldman said if you write between something

like 6 or 10 pages a day, push for 10 because that energy gets transferred to

the reader. This at least means you have to accept that first drafts are not as

shit as they are made out to be.

The writers who so gleefully advocated

their first draft’s shitness, well I’ve read some of their final drafts and I’m

not sure they were always so aware just what was shit and what wasn’t anyways. I

like the “polished diamond” analogy: many times I couldn’t find the diamond for

all the shit that remained, when I was so confidently assured of its acknowledgement

and subsequent removal.

You can take a one-day break if you can’t

write anything, but more than one day in a row and things get rusty. If indeed

there is rustiness after a more-than-one-day break, it peaks pretty quickly: you’re

about as rusty if you return after a week or a month as you are after a two-day

break. But you might need a long time to recuperate your mental energy. In

which case, if you go beyond a one-day stretch, fuck it: take a month. Who

cares? It gets done. You might as well ensure it gets done in the least painful

way possible. No matter what you’re doing, the one sure thing is that it takes

longer than you think it will. Also, no matter how long it took doesn’t seem to

matter once it’s done.

When I get to editing, all my time goes

into it and I don’t write new material. Writing new material would create this

unwieldy effect and make me feel a bit hopeless. One bloody thing at a time,

right? Editing is not writing so much as it is reading. So maybe you’re reading

and evaluating your own work and reading novels and such with the rest of your

time. Then maybe you have the next story idea you’re super excited about but

you can’t write it yet because you’re still editing. Maybe, since the last

story you wrote, you’ve read tens of books, maybe even a hundred plus: man is

your head ever full of stuff! In which case, you feel absolutely certain that once

the thing is edited, and you return to writing new material, you will fly

through it, and it will be the best quality thing ever and you’ll have it done

super quickly.

So one story is edited and out there, and

you’re starting the next one: that first day you write beautifully, for hours

on end! You get like 5000 words, and you are so enthused about the project, and

it’s off to a wonderful beginning. You go to sleep ecstatic to wake up the next

day and start again. You sit back down and- huh?! Have you been writing for a single

day or are you into week 8 of your 2k-a-day stretch? Makes no difference to

your brain, that has left you without motivation, confidence, stamina. This is

the second curious property of “taking a break.”

To summarise:

-

If you take a break from your writing

project for more than a day, when you return it doesn’t seem to make a

difference if you’ve been away from it for two days or two months. So, if you

need two months or longer to want to return, to do some research, to read other

books with a similar intent to your project’s, just do it. You deserve to enjoy

the creative process. Lack of enjoyment of anything is no guarantee that doing

the thing is worthwhile. I used to operate on the converse of that principle

and it just made me miserable, and it’s no one else’s need or desire to prevent

someone from their self-appointed and unnecessary martyrdom.

-

If you are about to return to

writing and start on a new project, you might think that a long break gears you

up for it, supplies you with enough fuel to reach the end at full pelt. It

does, for about a single day. Thus, long breaks with this intent don’t give you

enough payback to be justifiable.

Essentially, the detriment of taking a

break during a writing project is overrated, as is its perceived benefit

between writing projects. While I do think that writing quality varies

proportionally with the dedication of daily routine (and this has been proven-

somewhere), if you can’t keep this momentum up, as I mentioned in my last post

you can re-type the entire thing one day after another, and supply Goldman’s

daily energy that the first draft was lacking, and overcome any rustiness

induced by a necessary break.

Write or don’t. It gets done. From my

experience, unforeseen delays have done nothing but improve my writing because

they provide an objectivity that my impatience wanted to take away from me.

The project can achieve its maximum quality

in many ways, at any time, but a lack of kindness to oneself cannot be undone.

�QGU��

September 10, 2015

Writing is rewriting is retyping

Dear indie author,

You may be wondering why I haven’t gotten round to reviewing

your book, yet- even although I have read most of the ones I’ve been sent. I am

currently in the middle of a massive retyping effort, and wanted to

procrastinate about it further by telling you about it :)

I have the manuscript for a new novel, and all I’ve been

doing for the last week and a half is typing the damn thing out again. The idea

initially came from my GR friend Lixian who mentioned that one of her favourite

authors, Kazuo Ishiguro, types out his manuscripts 4 times. I don’t know if I

have that stamina, but it makes sense that if you want a story to last a while,

you’re prepared to spend a bit more time on it after it appears done.

Retyping is awesome and I wanted to share with you why:

- Feels like cheating: you know that weird half-hearted

feeling you get when you write a first draft of something and it doesn’t quite

feel like what’s in your head? And you pick and pick at scenes, adding and

subtracting? Well, finally, you get to go back and write it out perfectly for

the first time, at a rate of like 7k words a day, without research, without

doubt about what comes next! Unbelievable!

- Low energy, high quality: If you have a complete, edited

manuscript, it’s undeniable that most of your work is done. Re-typing is like

the victory lap that caps what’s already a success :D However, re-typing is not

a no-energy endeavour, and if you feel yourself typing on autopilot, you should

take a break :)

- What the hell is “rewriting?” I don’t really know. But

what could be a more guaranteed method of “rewriting” than re-typing your

entire manuscript?

“Dear Leo, writing… is re-writing”

“What’s re-writing?”

“I don’t know”

“Cool well I literally rewrote the whole thing so stfu”

- Corrects any imaginable fault in writing: whenever you

hear an author talking about their process, their daily word counts, how long

they leave a manuscript in a drawer for… this is all fluff. It’s just a thing

to say, but it doesn’t matter all that much. You know intuitively when a thing

is done. If, for example, you took too long away from the story or a big break

half way through writing it or wrote sometimes at night/ sometimes during the

day or whatever, retyping a manuscript over a number of consecutive days will

ensure narrative flow from beginning to end and fix any perceivable problem

with your text that may have been induced by erraticism in its construction. You’ll

fix problems you didn’t even realise your text had when you see how completely detached

retyping makes you to any given sentence, description, thing a character says,

whatever! Any and all of it can be changed, discarded, re-ordered. For this

reason it is sometimes recommended to read your story aloud, and I would

recommend this also, but in this case, the old content still exists. I’ve found

that through general editing/ re-drafting, scenes contain all the ingredients I

want them to, but they could arrive in a smoother order. This makes sense when

your scene began from nothing and proceeded in a single direction into unknown

territory, but now that the whole thing is there, you can re-visit, replace,

restructure. And you will spot more opportunities for re-ordering by re-typing

because naturally you will become accustomed to how a scene looks and become

passive in your observation of it. But retyping demands active observation of

your entire text, and easily offers you the chance to solve anything you think

could be done better. This reordering of ingredients is something that does not

and cannot occur to me unless I retype the thing and get an intimate sense of

what is supposed to come next.

- I’ve said it before, I’ll say it again: what better test

of the conviction you have for each sentence than seeing whether or not you’d

happily write it again?

- Works for all writing efforts: it doesn’t really matter

what you’re trying to achieve with your writing, typing it back out again will

improve it. I get that for a first draft, during the best parts of the process,

you type as if the story is flowing through you, as if your fingers are flying

on the keys independent of you. That’s great, and none of that energy or

content is going away: it is simply improved upon. I really enjoy listening to

Terrence McKenna’s lectures on Youtube and in one of them he explains how, on

DMT, elves convince him to sing objects into existence through glossolalia.

Cool, but surely if he were to write a song about that experience for me to

understand, the lyrics wouldn’t be “aoefliuh gurghløielge hg kejhgseiubvkr”? Or

maybe they would- I haven’t decided. I’ll see what I think when I retype it! Even

if you’re doing some wild experimental thing/ capturing a stream of

consciousness or whatever, remember that the people who introduced these

techniques likely wrote them out longhand in notebooks and then went to the

typewriter, and then discovered an error and so used the only method available

back then to correct it: typing the whole thing out again. Re-typing is

reverting to the way stories were written before computers. I can’t remember the

last time I googled something by spelling it correctly, for example- it wastes

time! But written stories of all variety are private, meditative considered

things, and the good ones flow easily- or juxtapose or jar easily: whatever the

intent is- no matter the direction or content. Good stories deserve every

effort to ensure these features.

- Reach new heights: every time you release something, you’re

telling your reader it’s the best you can do. So I imagine that the idea of retyping,

for those who haven’t done it before (myself included) will initially be met

with cynicism. If someone thinks they can achieve their best without retyping,

why would they spend so much time on a lengthy exercise to improve it? I know

you would never release a story if you could possibly imagine how to make it

better. But that’s why retyping is fun: previously unimaginable improvements

come to you.

- Get high on your own stories! Retpying is the closest you

can come to discovering your completed story as a new reader. Because the full

thing is there, but each new page does not yet exist until you type it out.

What could be better? Before you write for others, you get to write for

yourself!!

Don’t believe me? Yeah well you wouldn’t, would you?! Lol I

have yet another manuscript that I plan to retype, and later on I will show you

a comparison scene and step-by-step explanation of the changes I made so you

can see how it works.

I would recommend retyping to everyone, and from here on in,

I won’t consider any project of mine completed unless I’ve typed it out in its

entirety at least once. I owe it to myself and my readers :D

Thanks for reading!

For Goodreaders: when my Tumblr posts make it to Goodreads,

the format goes weird. I don’t know why and apologies, but thanks for making it

this far anyways :D

September 6, 2015

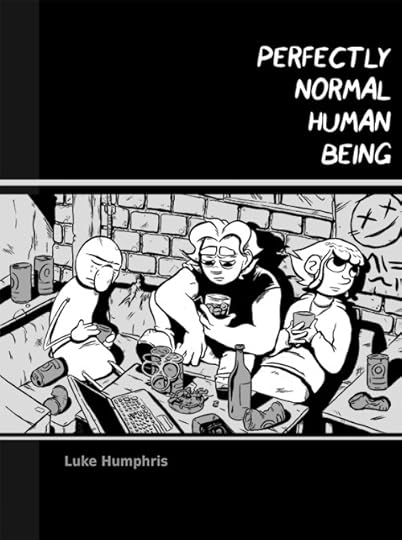

lukehumphris:

I recently finished perfectly normal human being,...

I recently finished perfectly normal human being, first of all if you have not read it and have a little bit of spare time, please check out

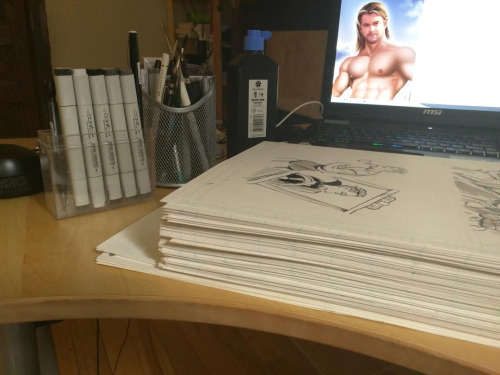

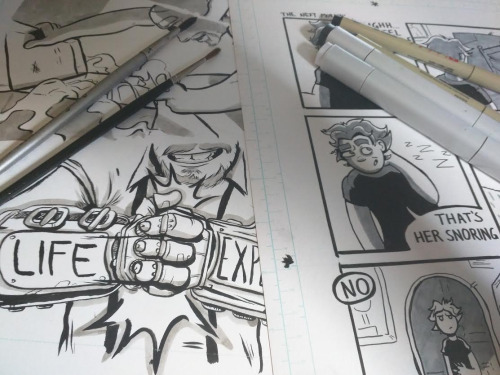

http://www.lukeatsea.com/pnhb/

I wanted to show off my stack of papers, this has definitely been my largest project to date and there is something satisfying about having this physical representation of my work.

I mainly worked digitally before this, and that is how the story started and then moved into pens and copics before ultimately using brush/ink washes with digitial lettering. The whole thing is a bit frankenstein monsterish.

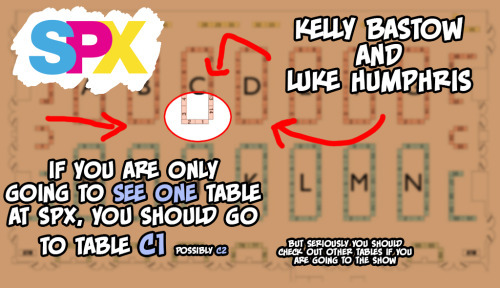

I created this whole thing to help me get closure and wrap my head around the things that happened in my life. I really tried my best to be as open and honest as I could with what happened in my relationships and own thoughts and wants. I’ve never put so much work into something like this before, and just by completing it I feel like I have killed a few demons and I do feel a whole lot lighter in the process. If people read this and at least find it interesting, that makes me unbelievably happy.

I will be sharing a table with the incredible http://moosekleenex.tumblr.com/, and table neighbours with the amazing space pyrates (http://caitlindmajor.tumblr.com/ and http://mkhoddy.tumblr.com/)at SPX later this month where I will have printed versions of this book, so if you are hanging around please come say hello.

I will also be selling some original pages from the book for $40 at the show, I can only take a few down, so I am going to try and pick out some good ones I like. If you are keen to buy and original and a specific page, please send me a message and I will be sure to bring it. If you do, you will not be obligated to buy it or anything, some pages the text was done digitally so it may not look the way you want, so I am more then happy to let you check it out before you decide.

I have had a few people ask if they can get the book online, I have nothing planned at the moment, but I will do a kickstarter or sell a few through etsy or something when I get back.

I started each paragraph with I, I am a terrible writer.

August 28, 2015

Gold, Miners and a German Flaker

I underwent (what a painful verb!) one of those timeless

lessons in misanthropy also known as a university group project. I decided to

be team leader because, surprise! No one else volunteered, and I didn’t trust

them at all anyways. Later, I allowed a German guy into our group because he

joined the class late. I was in charge of assembling our report, and the people

who actually did their work on time sent me their sections. I put it all

together, labelled the missing pages with something like “pending” and the

person responsible’s name, and sent it back around with an email saying ‘Good

job guys, it’s in good shape.’

German guy emailed back. This was written in red, by the way-

something like “Well, Leo, if you’d actually read the report you would see that

it’s NOT in good shape!!!!” He singled out those people I’d highlighted in the report

as not doing their job, and called for an “emergency” meeting, something only I

had the authority to do.

You see the dilemma: he thought he was some super sleuth for

discovering information I had provided him with, and emailed the entire group,

Phoenix Wright-style, to say “J’accuse!” I was one of only two native English speakers

in my year, and I’m not even sure how many of the rest of the group actually

read the email, so luckily no one picked up that the red, bold, italicized,

underlined and multiply exclamation-marked sentences within were pure unsubtle

invective against me, the guy who, I’ll point out again, volunteered to

coordinate everything because nobody else did, and provided Lorenz with

information that, now in his possession, he then accused me of not having.

(A mini-digression: I don’t believe it

should be anyone’s responsibility to ensure that adults do

what they were asked to do, and I did not give a fig that there was missing

work from this report, because I’d planned to re-write the entire thing with no

one’s permission and submit it at the end without telling any of them because

university group projects are hell made earthbound and require the dirtiest of tricks

to pull off successfully, and “pleasantly” is the least frequent of ways I’ve

ever been surprised, although “inappropriately” is in the upper percentile for

sure…)

Lorenz was a well-educated intelligent and otherwise

friendly, interesting guy. Clearly, he was a little bit egomaniacal, and

thought himself more perceptive than others. Personally I can’t relate to

any of that ;) I had provided him (and eight or so others) with

a communication that I thought was congenial and watertight when it came to

misinterpretation, and he completely blew up and fell out with me, entirely

through his own doing.

Imagine now that you’ve written a piece of fiction, and send

it out into the world. You’ve worked super hard on it, and no one asked you to

write it. Lorenz pops into the fray and gives you feedback on it. He hates it.

You feel terrible for a while, then you look back on it, and realise you didn’t

do anything wrong. The fault was that you live in a world where Lorenzes exist

in large quantities.

You see, people say they like to be challenged by fiction,

but either few of them do, or few of them rise to the challenge. The strongest examples

I can think of are a bunch of films. The thing most people liked about Birdman

was the meta-casting of actors who were in superhero films, because they got to

tell you they “got that.” People for whom this was the only take-away from

Birdman enjoy smarmy trickery for its own sake. That in Halloween, some artist

who used white masks is referenced in a picture appearing in the background; Borat

was really making fun of America, not Kazakhstan, because the point was that Borat

was believed by Americans; Day of the Dead was also a social commentary on American

consumerism; Before Midnight wasn’t supposed to have a plot, or be insightful,

fun, funny, or worth watching at all; They Live was a satire of duh duh fucking

DUH! They go into these films, barely scratch the surface and come out with flakes

of gold thinking that everyone else’s hands only contain dirt. You and I know that

the excavation of gold is a sophisticated act and never shine our wares in the

face of those with meagre tools unless someone asks us to share.

Some people probably loved the whole Borat film just because

Sacha Baron Cohen wore a funny moustache: so fucking what? Who is it for these people

to judge anyone else’s response? All they’re doing is wanting someone else to

acknowledge how smart they are. But as we saw in the quintessential case of

this, known as “Lorenz’s fallacy”, the response they evoke is often the exact

opposite from what they were looking for.

If you’re a writer, your work is going to fall into the

hands of a Lorenz. You can write the best, most skilled, deepest, coolest most

intricate whatever: someone is going to misunderstand it so badly it will

boggle your mind that it wasn’t deliberate.

Lorenz got to me. I just needed to tell you that because I

don’t think it was obvious.

When I started releasing books, one lovely thing that my

sister said to me was “before you take any reviews to heart, ask yourself if

your reader was clever enough.” I am trying to write for those readers:, using

whatever skills I have to the best of my ability to reach them. Inevitably, readers

outside of my target group are going to pick up my works. Having not pitched to

them, I don’t know how they’re going to react.

(Another digression: this can work in your favour. If you

have some concept or idea and later realise it’s pretty similar to some other

film or book, NEVER point it out. Chances are your reader hasn’t noticed, but

if you try to defend yourself- no matter what kind of clever in-jokey way you

find of doing this- they definitely will. If you think some part of it is weak,

never overcompensate. Think of Frank in It’s Always Sunny In Philadelphia,

running the children’s pageant and feeling it necessary to point out that he

isn’t going to touch any of the kids. It’s implicit that both writer and reader

believe the writer did his or her job- any attempt to assert this only raises

doubt. It’s also been scientifically proven that confidence Trumps ability.)

I could try to pander to large groups with cheap smarmy

trickery. But it’s this back to this goldmine analogy:

- Some writers only provide flakes of gold and

dirt. They satisfy those who can find the flakes. Since flakers are in

abundance (although this fact eludes them, those wacky, free-thinking

individuals!), these writers are insanely popular.

- Some writers’ mines are filled with gold, ready

to be reaped by those who dig deep enough (miners.)

- Miners < flakers.

- Flakers patronize miners at parties.

- Miners cry more often in general, and are never

really sure if their hard work is worth it 9 times out of 10, until

piece-of-fiction #10 delivers them a high so powerful they can’t believe they

ever doubted their efforts.

- Some books are without gold; some readers love

dirt. Leave them to it! Join in, even! Dirt can be fun, and what are you gonna

do with that gold, anyway? The type you get from fiction is not often a kind of

currency. That’s right: in my extended metaphor, “gold” doesn’t contain all the

properties of gold. Now isn’t that useful?

Gold flakes are addictive, though. For example, Ray Bradbury

walked out of a reading of/talk on Fahrenheit 451 because his readers insisted

he didn’t understand the message of his own book. Bradbury got badly Lorenz’d!

And the most painful thing for him was that, writing for miners, it probably

didn’t occur to him that anyone could misinterpret his story.

I have fantasies of one day being on some panel doing

something where people ask me insightful questions about… something. But who’s

gonna be in that audience? The call to Lorenz is a powerful thing. Don’t you

sense a general discomfort of any creator at a Q&A sesh? Since I wanna be

there A-ing Qs, I usually frown at how jaded some people appear about the process.

And yet I don’t know if an appearance fee high enough exists that would get me

out in front of an audience of Lorenzes.

You have to read this wonderful essay, which in part points

out that in the 80s and 90s, advertisers sold lots of products by embedding the

artifice of advertising in their adverts. That is, they more or less projected

the message that they were evil capitalists selling you crap you didn’t need.

Sneery flakers sneered and bought the products as if in part to prove to

themselves that they “got it.”

Although I don’t feel sorry for such people and I don’t

agree that receiving these types of messages puts consumers in an inescapable

bind- it’s just a tax on the self-congratulatory.

If you send something creative into the world, you’re gonna

put yourself in the firing line. If you take a hit, it will make you feel bad,

because you volunteered to do it, and you feel that you warrant some sort of

respect for this- and you do! You absolutely do. You are incredibly brave. But just

because you deserve respect, doesn’t mean you’ll always receive it.

Idiocy is a powerful drug.

Okay, that was fun. But it’s worth saying a few more things.

It’s true that if you are a miner, a flaker may berate your lack of love for

some crappy book or other because they think you “just don’t get it”, whereas

you dug deep and found only gold flakes and false allusions to riches beneath,

and want to respond “Yes, I do get it. I get all of it, and I still hate it!”

But you’re too damn kind and beautiful. Hit me up later in life if I get

divorced? That’s the last thing I’m trying to do, although I’m sure when I

leave coffee grounds all over the kitchen, beer cans in the living room and

pants in the shower, Juan suspects otherwise! Aha aha aha.

Some flakers are earnestly trying to share the fun of mining

with others by pointing out where the flakes are. And I’d say not just flakers

but almost everyone, smart or no, is generally insecure about their

intelligence, at least some times. I think it’s because the following is just

not said enough:

1.

No one can tell you that your interpretation of

art, or of anything really, is not valid, if you have ample evidence for

something being the case. Disagreeing with someone is not always conducive to

either of you being wrong, or even that one of you is “more right.” But since

this is a commonly held belief, when it comes to art, a lot of people are happy

with receiving a work of art’s single message through minimal interpretation,

because to them it’s like being offered entrance into a secret club with their

favourite amount of effort: some, but not that much. The response then is, with

one’s new authority, to attempt to offer membership to others, or berate them

for not having it. Although, my kinda cultural people are of the Groucho Marx

variety and would not be in any club that would have them as a member! I think

a lot of miners are like this. Pfft, who am I kidding? Goodreads has proved

that!

2.

In my opinion, not “totally getting” something is

not only acceptable but a necessary condition for loving it. I love good

fiction like I love my husband, family, job, life: I don’t totally get it, probably

never will. That’s okay, because the process of understanding is the goal, and can

provide a lifetime’s worth of satisfactory pursuit.

Flakers are happy just to have gold in their hands. True

miners know that they can reap riches, but will never really know when they’ve

collected everything. There is always the unexplored patch of dirt, the rock

that won’t crack open. In my fucked up extended metaphor, rocks can have gold

in them, but not always. Here I am writing about respecting a reader’s intelligence

yet my own metaphors beg a painful explanation. Hey: I never said it was either

easy or that I had 100% success rate! I’d be happy with 51% tbh… And at least I’m

self-aware when my metaphor isn’t working. And if I managed to warm to you by

letting you in on the secret that my analogy is a cheap artifice, would you be

interested in this state-of-the-art BMW?

Check out this total Lorenz. The guy read and reviewed David

Foster Wallace’s collection, Oblivion. The title story- SPOILER- deals with a

married couple, and the entire narrative purports to be first person through the

husband’s eyes. It is revealed ever so subtly at the end that the whole thing

has been the wife’s dream, revealing her impression of her husband, rather than

it being a factual account of how her husband really was. She is an unreliable

narrator, looking through her husband’s eyes. And yeah, in case you needed more

proof how great a writer Wallace was, he wrote the only great “it was all a

dream” story in existence (or since Adam Sandler’s Click, if you’re a flaker.) Here’s

what a reviewer said:

“The pomposity of

[‘Oblivion’s’] narrator has disastrous results for the story. What might have

been an affecting and genuinely ironic domestic tale, about a man’s

comic-pathetic inability to read correctly the warning signs in his marriage,

becomes instead a fantastic and repellent exercise through which the reader can

barely drag himself. Moreover, the hideousness of the husband’s voice stacks

the cards against him, precluding any possibility of sympathetic

identification. ‘Look at this pedantic little idiot,’ Wallace seems to be

saying, ‘which we can tell by looking at his absurd manner of speaking.’ So

irony is starved to sarcasm, and sympathy to voyeurism. It is literally

impossible for the reader to enter the story; Wallace has sealed all the gates.”

This guy’s job is to review books, and he slates a book

because of his own misunderstanding. Is Wallace to blame? Nope, but he still

takes the hit for foolishly misjudging his peers’ intellect. He hands them

precious, jeweled grenades. A week later, they return to him: “Wallace! You

left this pin in here, you fool! But I located it, with these: my eyes! Hah!

Bet you weren’t expecting I had those. But you see, I’m a free-thinking

maverick individual! They don’t make billions of them like me! Here: take your

pin back!”

BANG.

You know this already. And if you’re a fiction writer, and

this sometimes happens to you? My god, treasure it! It’s a truth that should be

universally acknowledged that most people are pretty dim, and if the success of

your fiction relies on its entrance into an intelligent mind, you have done a

kindness to both of us: you bet high stakes on intelligence conquering idiocy.

Go you.

(Disclaimer: GR formats my Tumblr posts weird. But thanks for making it to the end anyways :D)

August 17, 2015

A Timely Lesson in Skimming

Let’s get ready to ramble!!

I read a whole bunch of books on holiday. But what the hell

do I mean when I say I “read” a book? Do I mean page 1, 2, 3, through to last

page? Looking through this year’s selection, I’d say that’s true of a third of

the things I read, if that. A much higher chance if the thing was short, with a

next-to-none category for anything above 400 pages.

Books above 400 pages exist. Lots of them. I’m not sure that

they should. In Oslo I was wandering around a “friki” shop (for frikis) called

Outland, which has this massive sci-fi/ fantasy selection of books in English,

and I kept picking up the biggest books I could find, in awe that any one

person could maintain a single narrative over so many pages. But whether or not

a lengthy book exists and hence implicitly claims that the writer has the

ability to captivate you for the full length, I’m not sure that more than 5

people who ever existed really can.

I first started writing at 22, having always thought of

myself as a big reader. But when I added it up on Goodreads, I’d read 85 books

my entire life up to that point (Leo Silverblatt lawl.) So I sped up. I

justified the act of writing after the fact, and I did what 22 year-olds do: I

collected knowledge for the sole purpose of letting people know what I knew.

Information joy was simply a plus, not the pursuit. In order to do this

successfully, I had to push myself to read every word of Ulysses, of Gravity’s

Rainbow, of The Recognitions, of Infinite Jest, of The Divine Comedy, of

Finnegans fucking Wake.

Impressive? Stupid.

What self-respecting adult- nay: writer!- abuses their spare

time that much simply to earn the adoration of others?

What are you supposed to do? Not that.

What’s true of all the above books is I enjoyed parts. Huge

chunks. More than half, but definitely not all. As a reader, insisting on

reading each word meant I had less fun. Deconstruction is important, but

visceral response is the thing that time and again bestellers say they tried to

evoke (Donna Tartt, Stephen King, Ray Bradbury, and like, other ones), in which

case they should unashamedly allow prose to fly and leave its structural

intricacies alone- only feel. (This seems like the topic of Patton Oswalt’s new

book: http://www.avclub.com/review/patton-oswalts-memoir-details-risks-and-rewards-fi-213268

)

As a writer, I wasn’t trying to tell a story; I was trying

to prove a point, the point being that I am qualified to tell a story. Where

has any creative writing class ever advocated that? “Remember to unsubtly

remind the reader that you have shit to say. Take those chips off your shoulder

and launch them at the keyboard. Now press ‘print.’” Bullshit. As I’ve said

before: the only way you can convince someone you are capable of writing a good

story is by writing a good story. No one can tell you 100% how to do that. That

being the case, nothing is a guarantee. If nothing is a guarantee, you cannot

claim to be a good writer simply through self-inflicted endurances. Nothing can

de facto make you a writer. You will be known as a good writer if you write

something good. Hey: reading a lot is a good idea. Writing a lot is a good idea.

But no matter you who are, nothing can protect your material from skepticism.

I thought, ‘If I really read all the words in these books, I

will have endured tougher tasks than many other writers, thus I will lead the

pack.’ But I now know the following is true: no fun for the writer, no fun for

the reader. Because it seemed that what I wanted to emulate in my writing was simply

the difficulty in difficult texts. Rather than respecting the complexity a

given story required, I would purposefully make my work difficult such that if

a reader didn’t enjoy the story, they could at least appreciate that I was a

good writer (is that a possible combination of reactions?) I thought I could

get away with it without spilling, without being passionate, without giving

away part of myself. And what I failed to see was that these properties made

Joyce/Pynchon/Foster Wallace et al great. If anything, their penchant to

overcomplexify hindered the greatness of their texts. But I invented multifold

reasons why I was exempt from doing that scary thing: writing good fiction.

It felt like unless I did some penance, unless my head hurt

or I sacrificed something- something fun- I could not call myself a writer. None

of these things are a pre-requisite for writers, although many are common. “Ding

ding ding!” You should hear. “So is most shit I should avoid!”

Times have changed. On holiday, I read:

-

The Diamond Age: this is great fun! What a cool

world. What awesome dialogue. Hang on: a lot of this has nothing to do with the

story. Skipping the parallel fairytale story, lost interest in second half,

read the last chapter. I’d say I read 55% of its content.

-

Wool: baggy. So many words say nothing. The

protagonist’s characterisation was that she was female + the ol’ tic-tac-death

of one or more parents (I think? I don’t even remember): with that, I was dared

not to give a shit. Challenge accepted! Made it halfway through, then read only

the dialogue, skipped 150 or so pages and just read the last chapter. Maybe 55%

of its content.

-

The Time Machine: became obviously standard good

versus evil. Don’t even have to read the end because the story is told by the

time traveler at a dinner party, so I know he got home safe. There was a cool

bit about giant crabs and human fate at the end. Other characters whatever. 60%

-

Dracula: Read the first narrator’s bit until all

the letters-to-beloved came in. Turned out Dracula was a vampire. Where’s Van

Helsing? Skim skim skim. It says Van Helsing! Something about some other

patient. Here we have exposition that explains conversion to a vampire. Even if

this is the origin of the trope, we still all know what happens. Skim, skim,

skim. Van Helsing’s the one who kills Dracula, so let’s get to where he goes to

the castle. Skim, skim. They got him. 35%

-

The City and The Stars. Very cool first 100

pages. Lots of telling me emotions a la Wool. 45% If your whole story is one

guy discovering stuff about the world he lives in, there should be not a single

inclusion of a fact that is not discovered by him. The 3rd person

narrator knows more than the protagonist does? It completely invalidates that mode

of storytelling, as the narrator could surely tell us everything about the

world without the need for one guy to discover it. What I mean is: Greg read on

the laptop some secret email that suggested the cult had meetings for over a

million years. Could it be true, he wondered? Fuck it: sure it was. Greg doesn’t

have evidence for that, but I do because I’m writing the story: it was totally

true.

Of course no such cheap exposition was that on-the-nose, but by extrapolating

the technique of revealing information about the story’s universe whenever it

is seen as convenient by the writer, we see why we just can’t do that, as much

as we might want to. Although frankly, we shouldn’t even want to, because it

undoes all the good mysterious journey crafting work we do. If Greg hasn’t

discovered enough evidence of the millions-of-years-old cult, the narrator

needs to keep his mouth shut.

Why should I care about every sentence in a book when the

writer has not applied his care and skill sentence-by-sentence? Why should

sub-par material be imposed upon us, and why should we have to feel lazy for

not reading it when it is the laziness of the prose, the poor set up, the

pointlessly dry endurance test, that prevents us from doing so?

I also discovered that I don’t care about endings. Once you

reach that set of YES/NO conclusions at the end, the results seem totally

arbitrary in all but a handful of cases, such as in Whiplash or The Wind-Up

Bird Chronicle- simply because when you’ve seen a character overcome such

hardship in order to succeed, they just have to! I find it incredibly rare that

an author has crafted a story where the ending really matters. HARRY POTTER

SPOILERS (really?): does it really matter that Snape dies or that Harry

succeeds? Wasn’t the journey that much more fun? No matter where the narrative

stops, the only true ending to most stories is that everyone dies- or in the

Twilight saga’s case, that you wish everyone did.

This is a Carrie Bradshaw line, is it not? “I couldn’t help

but wonder: what happens after ‘Happily ever after’?” According to the White

Dwarf Research Corporation: “About 5 billion years from now, the hydrogen fuel

in the center of the Sun will begin to run out and the helium that has

collected there will begin to gravitationally contract, increasing the rate of

hydrogen burning in a shell surrounding the core. Our star will slowly bloat

into a red giant – eventually engulfing the inner planets, including the

Earth.” Some time in those 5 billion years, he may well buy you that diamond-

but it seems so much less important in perspective, doesn’t it? :D

One of my favourite novels is Natsuo Kirino’s Out. I couldn’t

wait to read the whole thing. I stayed up to read the ending, and that night, I

dreamt I was the main character, and I also dreamt up some completely different

ending to the story. I had just as much creative ability as a 19 year-old to

end the story as Kirino did. By the end, all that’s left to imagine is the dregs

of story threads: tie them every which way- who cares? What I mean is, every

obstacle has been overcome, and now we’re at the final showdown. If you’re

Chekhov, you just stop there! If you’re Dickens, you do the showdown then you ramble

on for about 50 more pages while your main character says bye to everyone. I

once helped one of my friends to the airport and she was like ‘BYE LAMP POST!

BYE TREES! BYE LITTLE DOGGY!’ On and on and on. Whoever thinks that’s cool has

less than half their anticipated charming quotient. Anyways, when I woke up, I

couldn’t remember which ending to Out I’d read and which I’d invented. And I

didn’t care! A few years later I read it again in Spanish for practice, and it’s

still enjoyable second time around, but seriously: I don’t know how that book

ends, and I could not give less of a shit! 5*!!

Short stories make me anxious if they are the

totally-pared-down variety that ensure the importance of every word they

contain. Can you tell? These posts are a total mess! :D On holiday was the

same: it wasn’t until the very evening I left Greece that I let the week’s

cumulative joy find me: the whole time the jury was out over whether or not I

would have a nice time and not spend too much money. Every event and location

held the ability to reverse the rest of the duration’s success. Only when it

was over could I enjoy it in retrospect. Don’t compressed stories make you feel

that way? The lesson here is not to take Camus to the beach. Similarly, I can

only enjoy short stories in retrospect, once I’m sure I paid attention to the

full thing and the hit was delivered.

Thing is, none of the above sounds like an acceptable way to

enjoy a holiday, a novel, a short story. But I submit to the great weirdness. It’s

all gone on long enough for me to conclude that this is how I enjoy things;

this is my method. Find your way of reading and writing: enjoy it without question.

You’ll write something worth reading when you write something you would want to

read, no matter what it contains or doesn’t. The more you take issue with other

novels, the more you will diverge your writing style away from those styles.

The more you find material you don’t want to read, the more you’ll exclude that

kind of material. If I don’t care about a book’s ending, or even remember it,

maybe I’ll write a book with no ending at all. How could I write an ending

authentically if I don’t care about it? And if the neatness of fully compressed

short stories makes me nervous, I’ll write the kind of short story I’d like to

read, whatever that is.

Before I would have considered the above advice deplorable.

But there is no pre-requisite how-to:

-

Learn an artist’s craft. Iron-clad artistic

process? Should you read, write, work hard all the time or be idle for long

stretches? Chances are, your innate artistic rhythm is so specific, so different

from anyone else’s that by the time you’ve honed it you have next to no advice

for me or others! How great that would be: you get to act like you’re being

helpful, but the competition doesn’t even notice that you’re not at all being

helpful. You’re just wasting everyone’s time. If you’re into that- I know it’s

very popular these days ;)

-

Behave as an artist. Enjoy or don’t enjoy your work,

discuss Dostoyevsky or Pokemon, touch yourself constantly or never- fuck knows.

If you ask me, doing something as esoteric and apparently- by which I mean

appears-to-be- next-to-pointless as writing fiction doesn’t sound like the kind

of thing you should do while complaining about how tough it is. Well why don’t

you learn a fucking trade, then? I’ll show you impactful: repair a boiler. Did

the boiler work before? No? Does it now? Yes. Bra-fucking-vo, you’ve made a

difference. If that was really your prime concern, trust me: writing fiction is

the last thing you’d be spending your time on. If you want to spend your time

doing something you hate that you’re never sure is making a difference or not,

go launch potatoes into a black hole or something. Fiction is to be enjoyed

(and my kind of enjoyment requires ample skimmage.) In my honest opinion- but

far be it from me to take away a good excuse to whine.

-

Appreciate and study the work of other artists.

Pore over every word, or don’t even read any? Will Self doesn’t read fiction-

or so he claims. Fellini said that he made films so passionately that he simply

couldn’t watch the films of others- or so he claimed. You see? No one’s even

saying you have to be honest about it.

My own choices leave me in a paradox: if a novelist does not

respect brevity, I will skim. If a short story writer is too adherent to

compression, I’ll get frustrated. Just rest assured that whatever I’m reading,

I’m not completely happy with it. It’s nobody’s fault, it’s just that nothing is

perfect and so we should expect the natural progression of our fun to be

patchy.

I’ve read a number of indie things now, and there’s one form

of nervousness I’ve encountered consistently: the author will claim to enjoy

Kafka, to understand Infinite Jest or The Recognitions, may even reference

these and the most obscure texts you’ve never heard of (call it “pulling a

younger Leo”- pleeeeeenty of people have done.) But their prose is pure Stephen

King. Try as they might to obscurify, they were snagged, ensnared, enchanted by

one guy and one guy only. (The dirty sellouts! Jk. Each2DareOwn.) He’s surely

flattered, but I’m not sure I know of any fan of his or otherwise who would

claim there were not enough Stephen King books in the world. As a writer, not

being completely enraptured by the prose of one single guy or gal is a total

gift. I think the best case scenario for any of us is that we become the brief

obsessive phase of a handful of folk, before they find someone else- but by

that point, hopefully someone else has found you: you stay afloat overall, but

not in a single consciousness.

Literary omnivorism sends you down the path of mongrelism. You

take the cerebral nature of David Foster Wallace and you leave behind his

masturbatory word counts; you use the knowingly crass and childish joy of a

John Waters film without spreading your satire as thinly; you attempt the kind

of honest surrealism that comes from the absolute submission to intuition’s

guide by writing down whatever image or event it tells you to, in the spirit

that produced the films of Jodorowsky, that explains Bergman’s enigmatic

reasons for writing his films (that are not far off “I had a bit of a cold and

my cat was missing: this became The Seventh Seal”), or Murakami’s quest to sit

at the bottom of a well (huh?) but maybe you don’t quite hit the mark because

you’re not comfortable with the meaning of your story being so obscure- because

you’re 26 and have taken exactly 0 mg of peyote.

The most important thing is that you embrace your

dissatisfaction. You pick and choose the best parts of your favourites, minus

what you wouldn’t have done. Complain! Skip! Throw books out your window, tear

down the towering talents of your idols with a lazy shake of the hand, and please:

leave the unwavering doe-eyed adulation to your fans.

��Ye�’

July 24, 2015

Self-aware characters

How does your impression of life inform your fiction? Of

course it does, right? That’s the whole subconscious architecture of whatever

you’ve written, but it’s not a thing we consciously ask. It’s more likely something

we realise once someone tells us their impression of our writing and what they

think it communicates.

One big realisation I’ve had, even just recently, is that I’m

aware of a lot of the bad habits and toxic attitudes I have, but unless I’m

willing to do something about it, things will remain as they are. I might know

even at the time when someone is manipulating me to react somehow, but that

doesn’t make me immune to ever reacting, if I’m tired or in a bad mood- and I

can prevent these in turn by sleeping enough and drinking less, but I don’t.

If none of my characters do things they know are bad and

that won’t work out, or if none of my characters appear aware of the reasons

why they aren’t getting what they want, I’m telling the reader I know these people

better than they know themselves, which is not true.

If you have time, the Chekhov story “A Dreary Story”

illustrates this beautifully. (I’m always drawn to depressing fiction filled with

mental traps, so beware my recommendations.)

The way it was put by the writers of It’s Always Sunny in

Philadelphia is that in order to be engaged in what unlikeable characters are

doing, the audience have to believe that the characters believe what they’re

doing will work out. But I think we can go further than that in writing.

The truth is, people often know what they’re doing even when

they’re behaving badly, which is a big interest of mine. I’ve watched countless

friends (hah! Countless! I’ve had like 10 friends total) and known of countless

more folk (another10 then extrapolating to fuck) who have things they really

want but go in the complete opposite direction of them consistently and make up

so many excuses for why they do what they do. I’ve seen myself do it many times

as well. I’ve known people to go after things they know are stupid and burn

others in the process and end up, unsurprisingly, unhappy!

What the hell is going on? None of this is trivial either. If

small acts of good can propagate in amazing ways (and I believe they can), the

tiniest act of making the world a worse place can go much further. I’ve realised

just now, then, that in my fiction, I’m not suggesting that deconstruction of

behaviours means we can avoid them; I’m probably just saying “Don’t you think

people do this sometimes? Isn’t that interesting? The end.”

Digressing a bit, I took this safety course at university.

In this course, we examined a bunch of case studies of industrial accidents. In

one, two guys climbed into a shut-down reactor that was filled with nitrogen

and they both asphyxiated. The professor said “If all this course does is make

you double-check before you climb into a vessel, I’ll have done my job.” He did

achieve that, and I will double-check, but the course also provided me with my

least appropriate niche-est joke that I can only tell to people I went to uni

with, or you. Two guys walk into a reactor: they both die. Anyways, that’s

probably all my fiction can do: provide a double-check. And if it achieves

that, I’ll be happy. That’s why “We need stories!” is weird. Because, well,

what a novel can achieve once the final page is turned pales in comparison to

the experience of reading it. Or does it? A message powerful enough could last

forever, in fact. We Need to Talk About Kevin, for me, contains many of these

messages, for reasons I won’t digress further about. Or like a friend of mine

said after seeing the film The Hunt (2012): “Next time they start some campaign

against a celebrity for being a paedo, I’ll be like, naw.”

I’ve caught myself trying to make characters less self-aware

of what they’re doing for fear that it doesn’t sound realistic. Why would they

proceed knowing it won’t work out? But as I’ve pointed out, that’s not my

experience of what people do. Not only that, but I think it makes something

more emotionally engaging and more heartbreaking to experience if someone does

something they know is no good for them or anyone else.

The thing that makes it tempting to have non self-aware

characters, although there will be some naturally (you can’t explore the

emotions of everyone in the story and hold interest), is that it’s difficult to

imagine what it’s like to genuinely think “This extramarital affair will be the

one that works out!” (This has to be the thought each and every time a new

affair is embarked upon, right? People are fucked up) or “Just a liiiiittle

more fame will make me blissfully happy and I won’t have to keep trying at

anything, even although my expectations thus far have always ran ahead of the

fame I’ve accrued” or “In a few years I’ll be alive: in a few years I’ll

experience ‘living life’, but for now I don’t have to meet my own basic needs

or have fun.” Thus, if characters are self-aware, it can be misconstrued as the

author being unable to fully put themselves in their characters’ heads. Not everyone

is aware of themselves; not everyone is unaware.

For example, that last quoted guy (“In a few years…”) sounds

a lot like me. But knowing that it’s important to be present doesn’t stop that attitude

creeping back in, and it surely affects my opinions and relationships and

behaviour even when I know what I’m doing and why I’m thinking what I do makes

no sense.

If you have time, this Demetri Martin thing is a brilliant

light-hearted lesson in the failure of self-awareness.

Capturing this kind of complexity makes for better fiction,

not less realistic fiction. It could be a reason young writers write badly:

they feel the need to know everything in order to convince a reader that what

they’ve written is worth reading, and maybe they haven’t yet seen how complex

and chaotic the world is for just about anyone alive. Well, good! This is a

horrible lesson! Well done, bad fiction writers! Good living!

Here’s another example of what I’m thinking about. Some of

my keenest memories are being patronised at parties/restaurants by adults. I remember

the fear in their eyes. Something about my existence as a young dude with

opinions- any young dude would have had the same effect- scared the shit out of

them. There’s this effect I’m beginning to feel where we think that the passage

of time is linear with importance gained or knowledge accumulated, and that isn’t

necessarily true. It’s difficult to stay open or remember that there’s

something to be learned from everyone, or that learning is the natural state.

In fact, with this set of books I’ve written at the moment, I hoped to “do all

my learning” by writing them so that I could “get up to speed” and just write

with a consistent level of skill, but it doesn’t work like that. A phrase I’ve

used many times to describe the process of writing a new novel or developing a

new relationship is that it is a puzzle unto itself. Experience can make you

calmer, more confident, but nobody ever learns anything about everything. “That

being true, why learn anything?” is a question I’ve asked myself many times. My

point is that I as a young guy talking to one of my parents’ friends surely

expected to learn something from them because they’ve been around longer, but I

doubt they expected or even wanted to learn anything from me. And even although

they knew it was ridiculous to think I wouldn’t know something outside their

set of knowledge, they couldn’t help but try to school me, because they didn’t

like that sensation. I’ve just deconstructed what I think is the logic behind

being made to feel small, but I will likely be one of these adults because I

learn almost obsessively as a way to be okay with time passing, which is not

necessarily a bad thing. However, as I learn in one direction, someone else

learns in another, and should they collect a significant body of knowledge that

is different from mine, I will get scared by that truth again: “You will never

know everything. So why bother learning anything? You aren’t everything to

anyone, nor the authority on anything.” I’m scared to talk to people my age

sometimes because I think they’ll be miles ahead of me at… something. So wouldn’t

I hate to be an adult talking to a kid at a party and learn something from

them?! Are you kidding me? I don’t even like talking to children in general!!

I just use this as an example of understanding erroneous

thought processes and the things we can’t accept, yet still falling victim to

them. The fear in the eyes I refer to is the voice in someone’s head saying “What

you’re doing/saying right now is not okay!” And this battle within us is what

interests me, but it doesn’t rage if we pretend either that if we know what we

shouldn’t do, we automatically avoid it; or conversely, if we behave badly, we

don’t know why we do it.

Here’s a funny example of this principle.

Something to consider :)

���[iU%@N

July 13, 2015

The thick skin myth

A few weeks ago I took advantage of a rare state of inebriation

(compared to the rest of the week) to go nuts sending out promo copies of one

of my books. I sent messages to 49 different people. This is admittedly a

promotional grey area, but the responses I got back (if any) were largely

positive. Most people were flattered I had found them and were willing to read

my work, one person politely asked me never to message them again, and the rest

didn’t say anything.

Certain voracious reader/reviewers must get bugged by people

like that all the time. Young curious people with less books and GR friends are

more likely to be flattered that you’ve found them and more responsive/ engaged

with your writing. For me, the reason I don’t promote my books as often as I’d

like is that I hate the idea of sounding so self-serving, and while sober can

only think of my hideous self-promotion as nothing but an irritation. I forget

that people might actually wanna read the stuff I’ve written or be thankful to

receive for free- doesn’t the entire principle of writing/promoting hinge upon

this being true?

But I get this feeling about promotion that I might be

somehow “tricking” someone into wasting their time and distracting them from discovering

something better. And yet, there’s all kinds of cool cred associated with

direct writer contact and the ability to ask about motivations/backstories/the

truth in the fiction/writer advice.

People who are starting to blog about books and are looking

for exclusive interviews and interesting original content? Where are they gonna

get that from? From you, of course! Because who the hell knows who you are? And

if you are any good, who gets to claim they helped you achieve the success you

deserve? Folks like them. And where would these people be? They’d be on

Goodreads. On the flipside of this, the least likely candidates for this

category are the many-friended powerhouse reviewers, for whom I have the utmost

respect but no desire to bother at all. In future.

By the way, every e-friend of mine who is also an indie

author made contact with me by “feeler” email, and I’m so glad they did. I can

see how it’s a pain, but surely it isn’t that much of a pain? Would I do it

again? I don’t know if I have enough reserve health/ kroner for the beer it

took. I also don’t know if I have a thick enough skin for it, but that doesn’t

matter, becauuuuusssee…

I listen to Marc Maron’s podcast intermittently, each time

he interviews someone I’ve vaguely heard of or who might have an interesting

life. Listening to the Henry Rollins interview, Rollins said he didn’t think he

had a thick skin? But do you get the impression that guy is held back from

doing anything at all with his life?! Maron himself has admitted that now in

his fifties he might have a bit of a thick skin, is “getting there”. Again and

again these meek little people shuffle into his garage and profess to their

meekness (Kevin Smith coming off as the most wounded.) But then, all the time

you hear it: in this game you gotta blah blah blah. See if you hear ANYONE talk

to you like that? They are bullshitting to some extent. There are two reasons I

know this:

1.

You have to spend some time working out how you

can authentically use your personality in a new role. For example, I’ve never

been in marketing. Having never assumed this role, I am not allowed to get away

with saying that this isn’t my thing, not for me, I can’t do it: the truth is I

have no idea, because I’ve never done it before. It’s like running or cooking:

running is for people with legs; cooking is for people with mouths. Just try

it! (I don’t run or cook.) Anyways, how can I, me, market something in a way that

seems authentic? How can I imagine myself doing this? Sometimes when we picture

our success in a new role, a few years down the line, it looks like someone

else in our skin, behind our eyes, moving in ways we wouldn’t, saying things we

wouldn’t say and doing things we wouldn’t do. Essentially, it’s a useless visualization

of us and our actions (Word autocorrects to US spelling and I’m too lazy to

change. The spelling. Also myself.)

2.

There are no rules. Nothing will ever work or

not work in every instance. All you have is more risk and less risk, but there’s