Leo X. Robertson's Blog, page 26

April 28, 2014

Findesferas now available through Amazon

Here’s the link:

Have you read it yet? If so, I would really appreciate your review! Doesn’t have to be long and of course, feel free to say anything you like!

If you haven’t read it yet, it’s available for free as an ebook in the following formats:

FREE MOBI: http://www.sendspace.com/file/db7tak

FREE EPUB: http://www.lulu.com/shop/leo-x-robertson/findesferas/ebook/product-21466093.html

FREE PDF: http://www.sendspace.com/file/zzzxx8

And I plan to do a Goodreads giveaway soon so you can win a free signed paperback! Free free free :D

New novel, book or something in a month or so when I get myself organised :-)

Ciaociao!

April 19, 2014

me: buys ten new books

me: re-reads harry potter

April 13, 2014

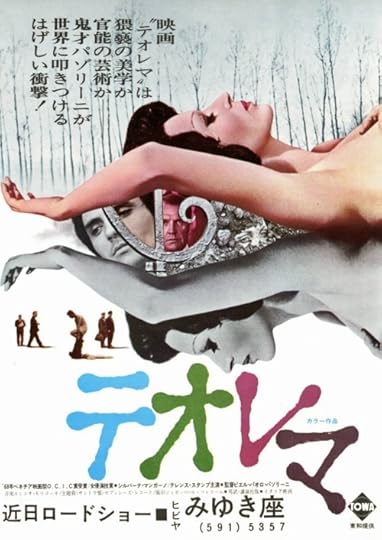

shrapnel:

Japanese poster for Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Teorema

Competitions for Self-Published Authors

I’m still here! I swear I’m still here and filled with new material that I’m working very hard on at the moment :-)

Just thought those self-published authors might want to know about two competitions I discovered recently:

1. Amazon Breakthrough Novel Award Contest: recently closed for 2014 entry, but link below to learn about it. Many different categories depending on your book’s genre, could be a great opportunity to establish yourself as an indie author :-)

https://www.createspace.com/abna

2. The Guardian Legend Self-Published Book of the Month: (for UK residents only!) The Guardian is a well-reputed UK newspaper running a monthly competition looking for the best self-published books.

http://www.theguardian.com/books/2014/apr/08/the-guardian-legend-self-published-book-of-the-month

Know of any more? Had any experience with either of these competitions? Hope you find this useful info :-)

March 13, 2014

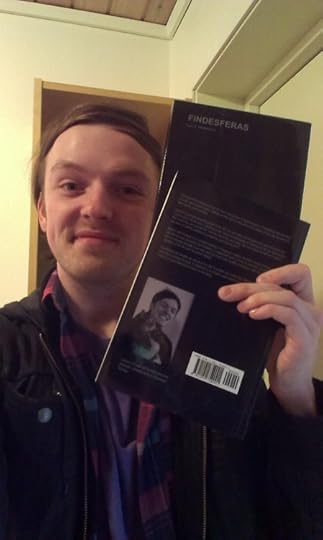

My own copies of Findesferas just arrived, sooo pretty!! A...

My own copies of Findesferas just arrived, sooo pretty!! A paperback and limited edition hardback! Formatting is great!!! Just to proofread everything for sure for sure then approve it to get sold eeeeverywhere! Yayayayayayayayay

March 11, 2014

Findesferas Part 10: The last part!

It took a day for the Brazilians to courteously escort the remaining soldiers and the marshal’s family back to Asunción on horseback. Matías thought he would dread the journey, but he had already lost enough, and barely felt anything at all. Guns were raised and pointed at the enemy soldiers once they had reached the gates of the city, but Matías hopped down from his horse, said ‘Give it up guys, war’s over.’

It was two jittery young men who were granted the task of protecting the entrance to the city, where his wife had been all this time.

'What do you mean, over?' Said one of them, expecting some Trojan trickery, 'While we're here the spirit of Paraguay-'

'The marshal's dead.'

'H-he is? Prove it, or we won't let you…'

Matías kept walking, but forgetting his manners, turned around to the Brazilians, ‘Thank you so much for escorting me back here. I won’t forget your kindness,’ and smiled, turned his eyes to the soldiers at the gates, saying ‘these guys are coming in too.’

The shining sun suggested life and liveliness in the city that he grew up in, but the streets were palpably empty. Matías gave no thought to this. It didn’t matter what had changed since he left, as long as one person was still here.

He walked in a straight line across streets, gardens, over fences, never breaking his path, until he arrived at the rear of his mother’s house.

Through the screen door he saw that she was inside, sitting in the dark like an abandoned factory mannequin, but there was some movement. She turned to a side table to pick up a glass of water, take a sip, press it to her forehead and tilt her head back in relief.

He walked up the steps and saw her look in surprise to the door, hunching her knees closer to her body, he opened the screen door.

'You're back? Oh, Matías! Are you okay? Where have you come from? What happened to you? What about the war?'

He looked blankly at her, ‘Over’, walking closer still she shimmied back as far as she could on the couch, then thinking how silly she was being, braced her back to stand up and face him, but he motioned with his hand ‘No, no.’

'Your mother…'

'I know.'

'But how?'

'Later.'

'And… and Juan?'

Matías took a deep breath, shook his head.

The room stopped. They looked away from each other, anywhere but each other’s eyes. He surveyed this room where he’d spent so many hours watching cartoons with his brother, his mother would come in from the kitchen with glasses of juice, ‘tsk’ at them for not playing outside, ruffle their hair and go to sit in the garden. His grandmother too, may she… may they both rest in peace, would sit in the room with them and read silly magazines all day. But even today there was life in this room.

'Are you hungry? I hope you've been taking care of yourself', said Matías.

'Yes I… I could use something to eat.'

He walked into the kitchen, saw a stack of tinfoil packets, each labelled with a different dried food, tin cans, bottles of water.

He raised his voice so she could hear from the living room ‘What will we do this evening?’

She paused, considered her words. ‘There’s not much to do around here.’

He tore open a packet of dried biscuits and placed them on a plate in a neat circle, poured a bottle of water into two fancy glasses, and brought it all in on a tray.

He smiled at his wife, ‘Sounds good.’

Octavia tensed up.

'Did you… want to talk about…'

Food on the table, he sat beside her, turned to her and reached a hand out, she flinched a little and tried to hide it, he put his hand behind her head and brought his head forward, closing his eyes and pressing his forehead to hers. He breathed in her scent, God she smelled good! How did she still have more of that perfume left… She gingerly placed a hand on his shoulder, felt the crumbling dirt of his uniform come off in her hand, but didn’t brush it away, only stayed with him, eyes open until she was sure this was all he wanted to do, then closed her eyes. Who knows how long they stayed like that? Nothing in the house ticked.

He let go and slid down her, embracing her stomach and lying on the couch.

A small figure crawled into the room. Two curious molten eyes of honey peered up at Matías from the floor.

'Hello, son.'

'Hello.'

'What's your name?'

March 7, 2014

Findesferas Part 8

Juan

Shaking rows of weary heads, Juan felt the blood pool in his lower limbs and crouched down amongst the other soldiers, hugging his knees, so glad to feel the soft stream of cool night air on the back of his neck. Every grainy little bump was agony in his swollen feet, hammering on his bones, torn between wanting to run off into the woods or ride it out in the hopes of safety. He thought, not worried, about his brother, who would be striding somewhere towards his eventual escape, Brazilians behind him on an invisible leash, but well aware of its presence. It pained Juan to be apart from Matías, beyond the day-to-day comfort blanket that his brother was to that indescribable level of complex need, that he no longer recognised the world, nor the world Juan, without his brother confidently somewhere, whether a location, a space, pinpointed somehow, and Juan wondered the last time he had been in this predicament, and came up short. Juan was without a reference, lead down a dead end in the dark, flame snuffed out and endeavouring to return to his reality.

Quite a sight was the rickety train and it made an epic humphing sound with violet plumes of smoke billowing sigmoidally up and backwards. Yellow flames pulsed in crackling chambers through the grill, the train like a perforated gas pipe flaring shooting through the darkness.

They passed over dirt, dust, asphalt, concrete, on roads, off roads, a disconnect from the ground beneath them, on some definite path cut through the country as if the convoy was stationary, wheels rolling on a moving globe, rotating tortuously, never to perturb the tenacious route of this strange train. Small cities ran past them left and right, and there was no curious glance from a single soldier, not at the cities or the swaying trees, not a guess at what cawing wildlife joined the singular crackle of the fires.

No, not until they reached that shadowy village because they passed through that too, slicing across the earth straw broken underwheel cattle wailing caterwauling blazing fire, villagers screaming, one man left his hut at the wrong time, witnessing the snapshot of the marshal’s face mapped by fire on the night and in that flickering face he swore- no, please no- it was him, the spirit of López had returned! That same inflated flesh shining skin and wretched dark teeth, determination, how could… then he was back. Yes, somehow here he was again, glaze of twisted monomania in the eyes. He will not let Paraguay meet that fate again oh no he was back like a malevolent spirit dancing across the wasteland of that old failure of his, saw the villager, to change the course of history, or- who could say!- play out a foolish play on the grandest stage, a parody of that great loss.

In the morning there was heat from the men crowded onto the wooden carts, heat from the burning furnaces, from the sun beating down upon their weary heads. There was no way of knowing how long they had been travelling for, the poor men having to stand the whole way, feeling every bump through the rickety wooden wheels. It took Juan some getting used to the way the men shuffled around the cart to stand in the middle to protect themselves from the sun, taking turns standing by the furnaces and they spent the first few miles clinging on to the other men so as not to fall off the side of the cart. Eventually he picked up the rhythm though, he had to. Juan was the only one present who could not tell his face how to act, and was a red hot sweaty vision of the unbearable conditions they had been enduring all this time. While the other soldiers did not speak, their feverish shuffling had started to slow down. Everyone was in desperate need of a rest.

The marshal yelled out ‘Stop!’ and the carts slowly trundled to a halt, men swaying to and fro with the change in acceleration before snapping back upright when everything was stationary. There was almost absolute silence, only the furnaces chuntering out their remaining puffs of energy, then the silence started blaring as the furnaces stopped as well, silence and dusty nothing everywhere. It stayed like this for a while, and Juan was so far from the captain that he couldn’t see him and had no idea what he was doing.

A flitting sound like birdsong stretched out and played in reverse. Another. Another. Bullets, πBullets flying through the air, the men readied themselves and hopped off the cart, forming a three-sixty degree battle stance they had obviously spent a lot of time preparing in Atyrá. Matías would have joined in seamlessly, finding a small gap between the other soldiers and forcing his way in. Instead Juan clutched his rifle, jumped off the cart and peered out aimlessly through the spaces between the soldier’s heads.

‘Me cago en diez!’ shouted the marshal, ‘They said the route was clear!’ Where these bullets were coming from, no one could see. That meant that snipers had dipped below the horizon peeking their cruel heads out every now and then to fire off rounds. Juan listened carefully to the shots. Wheow, wheow, wheow. Several shots occurring every five seconds, with a reloading time of ten seconds, maybe two teams of ten men firing at two distinct times? Outnumbered, then. A climactic sound rung out like a wet fleshy punch as one of the soldiers dropped and the wind of bullets stopped at the same time. Then tension in the men’s shoulders suddenly relaxed and they released the dead man from the wall of soldier, and he slid face first to the ground in front of Juan. Juan sighed in disbelief, and knelt down by the man, placing a hand on his back in an act of comforting but drew it back to his face sticky with bright red arterial blood.

The marshal stamped his feet from the opposite side of the train of carts, and his angry march could be seen through the gaps in the wheels as he stormed round to the location of the man.

'Well, what was all that about?' He said, like a confused friend and not a leader.

'Who's this on the ground?'

'It's… it's one of your men? I don't know his name, I wish I did', said Juan.

'Not me, son. Better that way. Men! Put him to good use.'

The other soldiers swarmed around the fallen man, pushing Juan out of the way, forcing him to climb back on to the cart. Through the mass of soldiers, Juan didn’t know what was going on, not even a suspicion. There were tearing noises, then the men stood back from the soldier, who was now naked, and stood all around him, lifting him up on their soldiers. Juan looked away out of respect and confusion as the soldiers marched the man alongside the train and flung him onto the first cart. They clambered up beside him and one soldier opened the furnace door. The men lifted the fallen soldier like a battering ram, and shoved him head first into the furnace, packing in his splayed arms and legs and forcing the furnace door shut again with their backs.

'Oh yes lads, that's right!' The marshal cried out, standing on the front of the train again, looking forward but calling back, 'Nothing to go to waste anymore, oh no, don't want that at all! Onwards and upwards, got to keep moving, and our man here's going to help us do that.' The furnace was kicking out fat plumes of acrid smoke, and the soldiers were quickly resuming their original formation on each of the carts, not a single one looking disgusted at the heavy smell that filled the air.

Juan covered his mouth and turned away from the dark smoke, and looked up at a road sign that one of the bullets had cut through: Concepción 200 km.

'Sir, we're heading to Argentina, right?'

'What's that, Juan? Of course we're heading to Argentina, didn't you hear me? We're going to Argentina, Argentina! Rio del Plata!'

There was silence, and all the men had turned to look at Juan. His heart slowed down. He had known it was a mistake before he spoke, Concepción was north of Atyrá, and the mouth of the Rio del Plata was south.

Juan looked back at the marshal’s family, huddled in a corner of the cage in flimsy rags, trying their best to stay out of the sun. The marshal’s mother looked back at him with a stern face, unflinching, and Juan knew then that this was all a mistake, the body, the cruelty, the misdirection. Something bad was happening, and Juan knew the only way out was to kill the marshal.

Findesferas

It was during the recommended hours for sleep that Juan went for a wander through the ship’s long branching corridors. He had many things on his mind, but he had gotten out of bed because he knew that if he did, he would find the woman from the graveyard.

Juan wore soft slippers and slid gently along the metal panels on the floor. There was almost no lighting of which to speak, all shut off for the artificial night, some ineffectual strips of LEDs underfoot. He had to be careful: his bearings weren’t the best, and he soon realised how impractical his footwear was when the floor gently inclined, and he found himself slipping back down, sometimes on all fours using the friction of his hands to climb up. There was a gentle hum from the engines that always seemed of uniform volume in all directions, which was surely not possible. Juan followed the branching network of cylinders, some smaller, some bigger, progressively darker, never looking out through the thick portholes to marvel at the purple darkness, on a mission to find the woman.

It was two hours and seventeen minutes before she appeared, walking away at the end of a corridor, disappearing round the bend and heading off a branching path unseen to Juan, hypnotised in a sleepy stupor, not surprised to see her, but more determined to speak with her. He picked up the pace, balancing himself against the curving wall, cursing his slippers as he slid on the floor, almost falling, so desperate to catch up.

It was another very long half an hour before he saw her again, and could not help but shout out, knowing fine well he would wake some of the other passengers.

'Hey!'

She turned around, a dark silhouette, but he knew it was she. He stopped, waving his arms, and she moved her head closer to see who it was. She moved in his direction, getting nearer, still a shadow but as she passed a porthole a fortunate nebula cast a red light on her and he saw her face, but it wasn’t the woman who stole his swimming pools. She stopped in the light, confused, but still something familiar… She called back.

‘Juan?’

'How do you…?'

At that moment, a booming voice joined in, this time from behind: ‘Juan!’

He was desperate not to turn around, but someone was definitely approaching at a quick pace. The woman also didn’t know what to do, but she looked sorry, sorry for making Juan chase her for so long, looking around for a way to help him, for them to speak, the two of them, panicked, she shouted ‘My name is Lalia.’

Lalia. But she looked nothing like his wife, her hair was longer, shoulders broader, still he knew that… That was it!

'You need to remember me, Juan, that's the trick', before she sped off again on her long journey through the ship, up and over and around and out of sight again.

‘Juan, what are you doing, boy?’

The voice got nearer, and Juan recognised the captain speaking. His fear started to dissipate, he felt a bit more satisfied. Remember her. Remember Lalia. That’s the trick.

Juan turned around to see the captain approaching. ‘A fellow night owl, what a pleasure to meet you at this hour. Come with me though, can’t have you noising up your neighbours like that, you gave everyone a bit of a fright. Thought it might have been you, you have that nervous sleeper look about you, son.’

'Sorry captain, I don't know what I'm doing here.'

'Don't know what I'm doing here either, son. Tell you what, let's have a little chat for a while, get your head settled then you can head back to your room.'

'Here?'

'Here? Spheres no, son, my quarters are a few branches away.'

Only the captain could use a word like “quarters” thought Juan as he was guided in Lalia’s direction to a large circular door, much like that of the captain’s study.

As the two men entered, Juan couldn’t help his curiosity, and made no attempt to hide how he peered around the captain’s room. It was much bigger than his own room, with a large four poster bed with a steel frame right in the centre, and the biggest porthole yet cut out of one of the walls above a metal desk, colouring the room like a kaleidoscope in the wild colours of the galaxies outside. There were two chairs bolted to the floor beside a small drinking cabinet. Juan imagined that through the other circular door was the captain’s personal bathroom and felt a pang of jealousy thinking about all the eyes he had to meet in the suggested morning hours while waiting for an unsatisfactory chemical shower.

'Sit down, my lad.'

'Really I'll be fine, I can go back to my room.'

'Do you remember how you got here?'

Juan smiled.

'I'll have a seat, then.'

'I'm glad it was you shouting out there. I did mean to have a chat with you.'

'We always have a chat though, I come by your study when I can.'

'I know you do son, but it's not always the right moment for us to discuss certain things.'

‘What did you want to talk about?’

The captain squeezed himself into the chair, and it soon became apparent that this was some initial design of the sitting area for this room during the first conception of The Findesferas. The chairs were positioned at an awkward angle so that neither man was directly looking at the other. The burly captain’s fat thighs extended a little too far in Juan’s direction and pressed into his knees. It would have been nice to shift the chair on the floor, except it was bolted down.

'It's Juliana. I'm starting to think she might be lost. I can't find her or her boyfriend, but I can't imagine they've run off together.'

'What can I do?'

'My men have started a search so there's nothing to worry about, but you? You're my little adventurer. In case you spot her on one of your night time explorations, you know where I'll be.'

'Right you are. Um… you know young women, they've got plans we don't understand.'

'Hm?'

'I only mean… nothing. Well, thanks for keeping me out of trouble. Could you direct me back to my room?'

'Ah yes of course lad! Out of here, left, left again, follow the path along and you can't miss your corridor from there.'

‘Um, thanks’, said Juan, not understanding the instructions but too embarrassed to clarify. He wandered down the corridor, head filled with thoughts of elusive women.

Matías

- Is this him? You said there were two of them! What was it then, a trick of the light? Did they merge?

- How should I know? Be happy I found him. Will we take him back to the cave, or do you want to eat him here?

- We can’t risk being seen, and I want both of them. It took us long enough to find one, now do you swear he was two people before?

- I’d bet your life on it.

- Then… leave him here.

- What? Why?

- Because he’ll return to the other one

- But you don’t know when that will be or if it will even happen. You were complaining of your hunger and that’s why I brought you here. If you’re saying that you can last longer then I don’t want to give you either of them.

- Tell me why not!

- Their family has been loyal to me, for a long time. The traditions are fading, few families still show their gratitude but still they give me gifts. If I don’t need to, don’t make me do this, please.

When the warbling red sun spun over the sand and poured through the weave of the basket, Matías awoke with a start and a wicked hunger. He stood up and, pushed the cloth away, hopping to remove a string wound round his leg.

Looking at his torn strip of the map, Cerro Corá was north, north and… he pointed above his piece of map to where he thought it would appear on Juan’s section, then yawn-sighed exasperatedly. So, sort of north-ish? To the dangerous place? Yeah.

He had plenty of time to ruminate on the stupidity of his plan while the Brazilian blouses were inflating, resting in the basket.

There was a fierce acrid smell that pinched at the back of Matías’ throat and made him shudder like a noseful of mustard, like dirt in an open wound, like the creeping runoff of a bag of garbage coming in a warm breath in his direction that heated his cheek with a sickly humidity, and he turned to see a black dog-like creature peeking over the brim of the basket. He gagged at the stench given off by the dog and jumped back falling out the basket on the other side and stepping away. The dog had a melted face and no ears and every breath was a staggered wheeze, thick black pelt coated with old oil, it started to shy away and turn around. Another creature emerged from beside the basket, a little pygmy sheep with mould-infested fur and sharp red horns walking on hind hooves towards him, curious, before trotting up to him on all fours, Matías backing away, it would have reached the height of his knee if it had gotten any closer. And then, for the first time he saw the creature that was with his grandmother all those years ago as it stepped out from behind the dog, unmistakeable, thick dark skin like paper creased and calloused with wrinkles that filled with dust, he looked like a little shrunken man, hundreds of years old but had a thick mane of tangled straw-like hair, black. Matías pressed his hand to his mouth in horror.

- What do we do?

- Pant, pant.

There they stood, looking at one another in silence, spirit met man and man spirit in the middle of the day. Matías was looking at his childhood fears, the beasts he swore as a kid to keep his brother away from. He had slowly begun to forget about them, even explaining away his run-in with Kurupi to a chance falling coconut, but here they were now.

- Pant, pant.

Matías edged his way back to the basket.

The creatures did not move.

- Pant, pant.

He nodded to them. Only the Pombero returned the gesture, and Luison removed his foetid forepaws from the basket.

Matías dragged the basket in his direction.

The soft winds lifted the balloon’s envelope and billowed a shadow over the creatures, and where it touched them they were invisible, and as the balloon waved back and forth they came in and out of view. Matías no longer feared them, and seeing the trickery in front of them was permeated with an odd sadness for the beings, dissolving from their own land.

The balloon waved and waved and like a negative flashlight took the spirits out of sight. Matías held the balloon and directed it to cast a shadow on all three at once, holding it in place for the wind to catch it, and as he moved it again, he saw nothing.

He steadied himself. As he lit the large colander of coal again and waited for the balloon to fill, suddenly he dropped into a heap in the basket and let out a hideous wail.

He dried his face with his sleeve, and standing up to take in Paraguay at daytime, the large verdant patches of green and epic grey ribbons of roads, the distant flapping birds as if in slow motion, clouds breaking in the distance and releasing their weight of rain, the mottled sky of graphite greys and burning red, and with these things that were Paraguay, he wanted to protect all that he could see.

Octavia

To look up, up at that peachy sky! A blanket of clouds, milk with sweeps of blood, then one at first in the distance… It was a dot. The soldiers rubbed their eyes, it wasn’t something to see, a speck of dust on the eyeball, but it didn’t go away if they looked up, down, blinked really hard, then there were two or three, getting bigger, then somehow like two adjacent slides on a projector it went from these dots in the distance to a skyful of hot air balloons, fluttering blouses, gunshots, flickering flames of the burners, that’s how they got here over the border, undetected, to the capital! Crammed in the sky like bubbles in a glass of stale water.

Ana was sitting in the living room in her favourite seat, green velvet eroded through years of sitting where the light poured in from the garden and illuminated her attempted reading, thumbing through a cookbook trying to get a high when she fingered a familiar stain of flour from when she had resources to cook for herself, when the house was hers, before the spirits started making deals. It was a recent favourite hobby of hers that was interrupted by the low moaning of Octavia upstairs in her study, where she’d been hiding of late and wailing too, but never like this. Ana closed her book with care, as if it was much newer than it was, and decided she’d better go investigate, preparing her best sympathetic mum face as mums probably do before their peace is unwillingly broken by household life faults.

'Octavia dear… what's happened?'

Sunlight gleamed two mirrored streaks of streaming tears on Octavia’s- much older looking- face, cranked back in her office chair and swinging idly from side to side, using the momentum to rock her child who slept in her lap.

'I cut his hair yesterday, and when I kneeled down to look at him I saw-'

'Matías?'

What a dear was poor little Octavia. The weight of the burden of her lament for her husband seemed to grow and press on her as the child did.

'No, I didn't. I couldn't think of anything but myself. All this time I've been acting like I'm not a mother at all.'

'You wanted to be strong for me, for your husband. I saw that in you.'

Octavia shook her head again. Ana was at a loss, and showed it with an exaggerated shrug, ‘Well?’

'I did it because I wanted to deny it, that he's been here.'

‘Why?’

Octavia’s eyes glared fiercely.

'This child’, her voice graver, 'He's Juan's.'

Ana scoffed in exasperation.

'When?'

'Soon after Lalia passed. I haven't learned how to comfort people in other ways, it was the only thing I thought I could do to help. I think that… Without my looks, what do I have? Dusty old books, stupid little anecdotes, I don't know how to be kind. All these airs of culture, style, nothing. If I can't get the basic stuff right, then who cares!'

Through years of her son’s silly pranks, brutally injured knees, almost deliberately hideous teenage years, Ana’s mothering skills were honed.

'Stop all of this. Nobody's punishing you, you've been up here doing that to yourself, and no one's better than punishing you but you. Whatever heartache you think you deserve, you've already had. Let that weight off, will you?'

Octavia’s sobs stopped, and filled the room with silence. Then, they came back louder and harder, tears of pure happiness in celebration of forgiveness. She lifted her son and placed him down on her bed, and flew over to Ana, giving her so tight a hug a vertebra popped back into place.

'What about Matías? What do I tell him?'

'You tell him the truth, when he comes back. You tell him the truth.'

'I don't know if I-'

'You think you know my son better than me because you fell in love with him and lived happily for a while, but querida, I’m his mother. I know him better than you do, okay? In Matías is more forgiveness than you’ve ever seen.’

'You mean it?'

'Try him, dear.'

Octavia pushed Ana back by the shoulders so she could get a good look at the eyes of the woman who made her float inside herself, losing all the weight, until she was not a mother but a little girl again, in awe.

'Thank you so much. Thank you so much!'

Ana heard whooping coming from down the street and peered out in horror to see a group of looters on horseback riding down the street. They were dressed as soldiers, their horses tired and emaciated. How did they get past the wall? How far had they come to get there, how many had they killed? Ana drew the curtains and walked briskly over to Octavia.

'Hide yourself in the shed. There are men outside and they will enter our house.'

Octavia asked no questions, and raised herself quickly, clutching her son and gently jogging towards the back door. Ana put her hands over her face and inhaled deeply, then confidently strode out the front door.

'Gentlemen!' she called.

The men looked at her in surprise. The leader of the four men trotted his horse over to her.

'Do you know who we are?'

'I know enough. Please take what you need and be on your way. In return you will not disturb my neighbours.'

The man lowered his head and peered at Ana with dull grey eyes pausing for a moment before turning to his men who had stoic faces.

'Okay then.'

With no further words exchanged, they dismounted and were led by Ana into the house. The leader clicked the safety of his πPistol and pressed it to her head. Ana stopped for a moment, then carried on walking in the same direction into the house. The man directed Ana to the couch by forcing her head with the gun, before pushing her on the shoulder to get her to sit down. The soldiers were walking around her house, heading upstairs, poking boxes and opening cupboards. Octavia heard nothing, crouched down in the shed, whisper-singing little songs she knew to her child.

'Tell me then what you have that is worth me sparing your neighbours.'

'Supplies. I have much more rations than the others.' It was a painful bluff.

'What else?'

'I have some jewellery in my bedroom upstairs. You can take it all. The only thing I ask is that you do not touch the rum or cigars in the cupboards.'

There was a fire in the man’s eyes, and Ana was getting a little too nervous. The soldiers could tell. They stopped what they were doing and turned to her.

'Rum and cigars, for us. How nice.'

'No, please don't-'

He placed the πPistol to her temple, and fired a πBullet into her head, and when she fell she landed on grass and looked up to see a wall of soldiers, all crying for her. ‘So sorry,’ said Gustavo and ‘I’m really sorry’, said Cesar, and as she rose to her feet on the grass the soldiers swarmed around her and gave her the best and most enveloping hug from all angles, and she felt comfortable enough then to let out an enormous wail. When the hug was over an eternity later, Marco emerged from behind the huddle with a kettle and a cup of yerba mate with the special straw. She had so many questions, but as she opened her mouth to speak, Marco, who was pouring water from the kettle into the cup said ‘Shh, take a big drink of this first, then you can ask’, and he had the kindest look on his face, one of pure sympathy. She took the steaming cup of leaves from his hand and took a warm, familiar sip.

'Where are my friends?' she asked.

'Well, Lalia is here, you can see her soon enough.'

'I did always like that girl. She really should have settled down properly though… I feel like there should be someone else.'

'Who else do you know that died?'

'Well, what about your sons?' said one of the soldiers, and the rest of them gave him a stern look, but it was too late.

'My poor sons! Are they dead?'

'No, not yet, but…'

'The Pombero.'

Ana took a deep breath, closed her eyes and straightened her shoulders.

'I think I always knew.'

That was okay, though. No hug, not from a thousand soldiers, was worth the hug of one son.

Let’s take two twins, and call them Juan and Matías. Both of them start off on earth, in Paraguay, then Juan gets on a spaceship which travels close to the speed of light (three-fifths the speed gives a nice round calculation later), leaving Matías behind. Even although the two twins were born at almost exactly the same time in the same location, it can now be said that they are no longer in similar frames of reference with respect to space-time, and will experience time differently. Since Juan, relative to Matías, is accelerating away at a speed close to light, he will experience time slower, and Matías will experience time faster. So, should Juan’s spaceship turn around and head back to earth, accelerating at a similar speed, when Juan and Matías meet each other again, Matías will be much older.

Now, we have called this a paradox, but it does follow directly from Einstein’s Theory of Special Relativity.

If Juan’s acceleration is treated as constant across the whole period of interest (such that we eliminate the time it takes for Juan’s ship to reach its acceleration, the time taken for the ship to turn around again and slow down upon approaching earth). At his acceleration of three-fifths the speed of light, it can be calculated from Einstein’s theory and simple Pythagoras that for every 4 years of Juan’s life, Matías will age 5 years.

So the question remains: if Juan should return to Earth, what age will Matías be?

March 5, 2014

Findesferas Part 7

The marshal was squatted on a wooden crate, haunches flat and swollen like pancakes on the wood, and he was gnawing on a large chicken leg. Juan was sat in front of him, legs together and back straight, sitting like a soldier might, muscles strained to keep him from his usual slouch. Not that he had wanted to before, but suddenly Juan felt that he couldn’t turn around, and was tensing his muscles not to spin his torso in the opposite direction and mess up, finding his brother and watching the war end and sorting everything out; a stack of thoughts was forcing his grey matter into a large marble. The background noise of laughing men in feigned revelry might as well have been the churning of a piston, the hiss of an engine. They were the well-oiled force of the marshal’s, not men. The incessant piston-churn of laughter increased the silence between the marshal and his new guest, as they struggled to forge a conversation. The marshal smiled and his cheeks distended from their regular soft ovals to meaty apples.

'Look at my men. Are they not impressive in number? I'd wager you haven't seen such a large army in quite a while. How have we managed to stay so many? Because we started off even larger. There must be two hundred of us left, but before we met you we were twenty thousand at Humaitá.'

Juan rested his hands in his lap and tilted his head as the marshal settled into a story.

'Dear Humaitá, soft vernal leaves shaking in the breeze, familiar heat, feet pressing into the warm and yielding earth, and yet the air was soaked with dread. Still, we were well positioned, back to the river, wonderful place to be at such a time, Rio Paraguay, the very home of the country. Surely you know the story of the foreign explorer, the first outsider to meet the natives of this great land? They told him it the river was Paraguay in their native tongue, and so Paraguay it became: “The river flowing to the ocean”. With turmoil all around, where better to reside than the very site that your homeland came to be?

'Never once all those years ago when the war began did I think I would see my men so starved with hunger that they voraciously drank gun oil, ate poisonous berries and claim it the greatest delicacy they had ever consumed before dropping dead in front of my eyes; that I would not see them dare to kill and eat their horses until, tears running down my sunken cheeks, I had given them the order to do so. And yet, where else would we have rather been? We knew that place like nowhere else on the earth, nowhere else would we rather starve. You see my soldiers much better fed now: they have a much greater hope of surviving. No, it doesn't say much, but I know them to be saddened to leave Humaitá. Maybe we brought a curse on Paraguay when we left, humiliated, and with half the country no longer ours- yes, half is gone.'

Juan leaned in, eyebrows raising to a point in the centre of his face, hope slowly sapping away.

'The Brazilians were the first to try it, back when my men had more than an ounce of fat between them, when the supplies from the raid of Mato Grosso kept us sated and I made myself that charming necklace of ears. News was brought to us from Encarnación that they had entered the country, when it was still ours, mind. When Encarnación was Paraguay's, No! don't think… don't think it. We scoffed, nudged each other, Brazilians take Humaitá? Never! I posted men by the marshes, had bags of sugar sat at their side, and so they stayed for days on end at the edges of the land, their new home. It was so pleasant to see the soldiers joking with each other on the frontline, tossing chunks of sticky sugar into their mouths, and even sleeping there, not fearing the eventual attack of the Brazilians. And when they finally arrived we wanted to welcome them, with such good humour did we meet those twenty thousand monkey eyes, dared them to approach our earthy haven, running playfully through the trees, and they all but throwing themselves into the thick marshland and to their deaths, how we laughed then.

'No! It wasn't the Argentinians that broke us. I will kill anyone who says so! It was time. The resources dwindling, and we, ashamed to grow weary of the town that was our home for two years, the salutes became slower, the skin cracked and the lines deeper, the teeth fewer, the uniforms tattered, so when we heard there was an Argentine camp to the south we rejoiced, given purpose once again to our inhabitance of that great town. These silly men, Argentinians, Brazilians all, and please, I could have batted off the assault of the Uruguayans with one hand. What did they know of our land? How dare they, how dare they think they could take it but they did take it and…'

The marshal looked up to dancing embers and scratched at his beard, losing track of his ramble.

'I sent my men down to Tuyuty in the night. It gave me great pleasure when I thought of accompanying them but some of my generals rightly advised me otherwise. I heard that the two trenches were taken with such swiftness and precision that the camp didn't even wake, that when the men strode towards the tents and threw open the flaps, that the allies ran off with such a start that they left their guns, horses, meat and salt. How I clapped my hands together joyfully with a force that jarred my bones when I saw the parade back to our soft town, weary men struggling with sacks of food. And there were prisoners too! Oh yes, our pleasure multiplied while they watched, we danced and sang. A soldier died in ecstasy head plunged ostrich-deep into a sack of salt. And could you believe what they brought with them! Copper pots, cigars, gold watches, rifles, horses, silver lighters, carpets, handkerchiefs…

'Perhaps I do not even need to recount what happened next, for I think you could deduce it with some accuracy. With no stable way to keep ourselves supplied with food and medication, our morale, health and all the rest that make a man went into decline. The moaning, day and night, was unbroken when dysentery struck down my soldiers. With no vegetables and no salt, the recovery, if it was not replaced with death, was slow and agonising. All we had was horse meat, which the men were not yet used to, and turned out to be the worst thing for them but the alternative was nothing. I tried to send out a group of my men on horseback for more supplies, but it seemed that the horses were sick to the nerves, and could not travel far. I never saw those men again, but they threw themselves screaming into my thoughts ever after.

'Humaitá was all we had, and we defended her with what pitiful strength we had amongst us. I had batteries of guns stretched across the river, but our weaponry was lacking and we could only defend such small stretches of the Rio Paraguay that we could easily take out any boat that would be small enough to reach the guns before they had the chance to get there. I sent my men out at night in canoes, to find enemy camps and see if they could not find more of those monstrous sacks of sugar. The men were tired, hungry, feverish, paranoid, and they travelled far from the camp, or so they thought, slipping around on the water in wide circles until one boat would pass another, and both men would jump madly into the river, so afraid that they had crossed canoes with an ally.

'Soon again we welcomed the attack of another wave of Argentinians, but the second time was not so rewarding. My soldiers were desperate, arms bobbing up and down with the weight of their weapons. The fight was done in a veil of smoke, shells spiralling through the air and I raised my arms up like some conductor in the sweetest passage of a symphony as the smoke danced through the sky and made the air thick, this my finest moment, so beautiful a sight that I did then kneel upon one knee and thought it would be a great honour to be crowned by a percussive smash of those majestic shells. I was not quite so fortunate as you can see, but still very lucky that I lost so few of my soldiers in that second battle, and invited the generals back to my private quarters where we spent the night drinking champagne, smoking cigars and singing songs of joy that we were all still alive. That could have been a mistake. Rumours spread through the camp, and as I passed the soldiers the bows became much more slovenly- they thought me an idiot, a poor leader when it was thanks to my leadership that they were still alive! So I started shooting them, son, every one in ten, you know, for sake of appearances, and that sure straightened their backs. One of my dear generals did not take kindly to my new style, tried to shoot himself in the head, twice. Luckily for me he did not die and I had the pleasure of executing him. Then I heard that a deserter fled the camp, and collapsed at a village a few miles from our position so I sent another man after him, to travel the same distance, on foot, a good lad, didn't dare disobey, told him to find the offending soldier and wish him a speedy recovery so that I may shoot him myself.

'After all that, even I couldn't handle that same town, those same dreary broken men day after day, and with a sorrow in my heart, after two fruitless years of tiresome waiting and vicious battle, I gave the order to abandon Humaitá. I cried for the poor lost town that day. My troops knew I was making the right decision, told me so with a look of resignation on their hollow faces. We crossed the Rio Paraguay, more than six thousand less than when we arrived at the town, uniforms bleached and ragged, red of the shirt, if it was still intact, now a sorry tired pink. The carpets became rigid ponchos, leather boots of the allies were cut up for makeshift loincloths, anything to guard from the relentless beating of the sun, crueller than the battles and the hunger, and I lost many more men before we made it to Atyrá.

'Juan, I fear that the war will be lost. I am humiliated to bear the news, and a conspiracy has been brewing against me for quite some time, such that my expulsion from this life eclipses whatever trivial fate may wait for you. Still, so long as I live, so shall Paraguay, for I… I am Paraguay.

Yes, I am Paraguay and I am cursed. Do not think I would dare lead these men to their deaths without reason, for my fate would be much worse. Since I have existed, I have felt every death. Every screaming loss of a soul from this land that left without redemption did not travel so far, but entered my mind and there resided for as long as I have had thoughts. They plague me, cruel angry spirits make me claw at my skull to desperately give them peace, give myself peace. So many unsatisfied souls swimming around, such a volume of rage and grief that you should certainly not think it strange if my skull imploded. I know what they want: retribution, vengeance, what is rightfully theirs. I am Paraguay, cursed and forgotten. Were someone to spin a globe and absentmindedly stop it with their finger on the very site we know Paraguay to be, finding an empty space, to suddenly know that Paraguay was not a land of culture, love, but now nothing, that someone might at best shrug their shoulders and walk away. But I am Paraguay and while we both are alive I will make us live, live hard and fight and love and exist so hard that the world will know that we were Paraguay once, shake in fear that we were Paraguay, and with our lives we will defend.

'I'm sorry, son, I don't bore each and every one of my soldiers with rhetoric when first I meet them, but… there's a memory of mine in your eyes. When I look at you, I think about playing chess with Venancio in the back garden. We had these large, painted wooden pieces that my father made for us that we placed on the grass, marking out the squares with string. Venancio taught me how to play and in that first game I lost so terribly that I would not let him leave all day. We kept playing chess, sometimes I won and sometimes I lost, but each victory or loss had no effect on me anymore, nothing took away that bitter taste of failure. We came back day after day. Sometimes I broke the wooden pieces in anger, throwing them out into the street for which I would be punished but my father always made more so we could play again and again until I completely wore my brother out and he would never play. What is it I see in you that takes me back to that garden?

'Well we made it to Atyrá, and here we've staked our claim. The citizens don't bother us, and we don't bother them in turn- no, we don't. We constructed this nice sooty convoy of ours. Let me tell you, those blasted little microbes could eat through all the coal we've hoarded too but keep the coal dry and they sure as hell don't like that. As long as we've got coal, we've got power my good man, and if we've got power so do you. What chance that you came here! Well, you won't slip away from us as easily, I mean that.'

There was a fire in the marshal’s eyes. Juan laughed to fill the silence and drank deeply, the sipping giving him the opportunity to think of a way to keep the conversation going.

'So, what's the plan? Are we going to camp out in Atyrá until everything dies down?' That sounded more like Juan's plan than the marshal's.

'No no, don't worry, nothing as dull as that, not at all. As we've stayed put for a good while, we've managed to relay messages back and forth to a battalion at the Rio del Plata. They promise us that the route from Atyrá to the coast is mostly secure.'

'Mostly?' said Juan, timidly.

'Yes, son, have to expect a bit of a lark these days, you know that. You've joined us just in time to go and meet the battalion. Why, a week later and there would have been almost no one here.'

'So what do you plan to do when we reach this battalion?' said Juan to keep him talking while off daydreaming about how horrible the journey would be, 'and what's there?'

'The end, Juan. The end of the war. Our last chance.' That got him listening again.

'Are we really enough people?'

'War's been long: you can streamline the manpower needed quite nicely.'

No, surely not. This would be tough, but with one final big uncomfortable push from Juan, maybe it could be over, maybe they could survive. Depending on how long the battles lasted, perhaps he and Matías could be back in Asunción with their favourite women in a matter of weeks. Juan inhaled deeply, his head rolling gently from side to side in thought.

'Okay. I want this to end.' Juan looked on with a weird, nervous conviction.

‘Pues vamos a luchar en la puta Guerra hasta la ultima!’

Matías

The balloon was small, and took little effort at first for Matías to trail it behind him, but as the miles wore on he had to clip both his hands onto the basket and marched forth with his remaining might in a triangle of effort. He wasn’t sure from what distance he would be able to light up the metal colander of coal, but no distance was an option in the night, the Brazilians would instantly spot the fire, and he needed at least a head start to get the blouses filled and billowing. Day it was then.

He sat down on the lip of the basket and leaned his head back looking up at the cool night. He placed his hand, fingers spread, palm flat on front of his neck and dragged it downwards, feeling the bristles of his maturing pointy stubble and sighing with agitation, running his hand around to the nape and noting the rubbery friction of dry skin on dry skin. He collapsed into a rather pleasant heap on the basket floor, there to rest until morning.

His dreams were plagued with Octavia. Juan had always mentioned how crazy his dreams were. ‘No less crazy than those thoughts of yours when you’re awake’, said Matías. Matías’ dreams were firmly rooted in truth, and his steely exterior during the day was often a function of how exhausted this made him. Any of this, any of what was going on was less painful, but Octavia no… He was entering withdrawal from the thing he still was, the reason free from passion to Juan and Octavia’s passion free from reason: they were a singular operational unit like no three people should be, split apart, aching to be together, cursed with the lack of ability to live as individuals.

During the end, when they were fighting every day, snapping at each other and mental faculties empty, couldn’t remember one from the other, somehow… she never lost her beauty to him. That smirk of hers, there was a truth behind it, a tangible secret of the Universe that she kept not in her or in him, just around them, that smirk had grown with both of them, it was theirs, together. Curation was scraping the bills and Matías couldn’t find a job that he didn’t hate and seemed to think that was a decent reason not to have one. Octavia had earned the right to stay at home with their child, what child? Matías clearly couldn’t have any, not that they ever checked, nor was Octavia pregnant after two years. Who knew for sure which one of them it was but finding out would only have added fuel to the arguments. The notion that one of them could be superior to the other was the problem and they knew it and hated themselves for it but it didn’t go away that nagging feeling that they could do better than one another, deserved better people, better lives. They spent so many years together that they couldn’t differentiate the big problems of adult life with the big problems that they as individuals brought to each other, and the effect was caustic.

She was flirty, drank a little too much, talked a little too much about herself. He wasn’t fun, didn’t share, a walking heat sink draining the fun out of every situation and if they dared to change, not change habits, no these were not habits, but deep facets of who they were they had decided, if they changed as people wouldn’t that be terrible! A loss of dignity as if the daily humiliations of being together were any kind of a victory. The anger was addictive like a magnet drawing them back to the same discussions time and again. Part of them thought they were having fun, using each other as a vent for all the frustrations of everything else going on in their lives.

Now that she was far away, not geographically but in time between now and the end of the war, God! He couldn’t wait to get back, he would sort it all he promised, forget those years of silliness. Now they were behind them they could stay there. He could forgive it all, be the best husband but no more of this.

Anything could be chasing him here ready to attack but one thing disturbed his sleep. He awkwardly pulled out Octavia’s letter. It was too dark to read but it didn’t matter; he had a picture perfect image of all the words:

My dear husband,

I can still call you that, can I not? I am still your wife.

Are we really so terrible at being honest with each other that this is what it takes to keep us apart? We tried desperately to survive off of one another, sucking out all the spiritual nutrients that we needed until we were both left hollow while the world blossomed outside without us. And we had more than enough opportunities to step back but we were worn down. I don’t know what more can be said about it.

Is it any use finally writing all of this down? Am I communicating anything to you that you didn’t already know? I guess not.

So please bear that in mind, please, when I tell you that Juan and I slept together.

He was so sad, alone, vacant after her death and I went to visit him to take him for a walk, see if we could name some flowers, sit in the park, look at the sky and wonder why, try to get him to see the world like a child again after what happened, but he needed some deeper level of comfort, so I offered him my body and I did not enjoy it and I cried because just like in our marriage I realised that I had learned to sacrifice too much of myself, too much of who I am and I was not the person I was before, and he cried because I was not his wife and that passion was gone forever and it was hideous and disgusting and pathetic and irreparable and I cannot tell you the morbid list of things that ran through my head that I would rather have done. Our child is no miracle.

Matías, you are a beautiful man, a sensitive, fantastic, passionate, enduring, understanding person that I have had the pleasure of spending time with, laughing with, feeling at peace and completely safe with, and in those best moments we shared together I felt that I finally understood everything, if for a few brief seconds I was staring at the reason to be then it was normal again like an experience we passed through put behind us and carried on, and beyond that snapshot of pure beauty it was crushingly mundane. But that experience is not like time, forever in the past, it is something we can have again, and if we hold the memories of when we looked in each other’s eyes and saw that reason to live, we can remember why we were ever together.

The choice to be made is not completely yours. You are not alone in this decision. I want you to know that if you want, we can try and repair this marriage, and I will support us in doing so. I have the greatest respect for you and I will hear any way you want this to go ahead.

Please return.

With all the love I can give you,

Your wife, Octavia

X

After some subconscious adjustment he slept curled up in the basket, cradling the coal like a pet dog, contorted into a jagged C.

Octavia

Octavia hadn’t seen Ana all day. It could have been longer. They couldn’t look at each other without that reflection of what they both knew had to happen. Octavia almost caught herself praying for Juan and Matías to die in the war, sure that she couldn’t live with the guilt if the Pombero came to take them. Yet these wild wiry thoughts of hers spun around in her head ever fiercer without company, and so she found herself forced to spend time with Ana.

Octavia crept up the staircase, old dried beams creaking even under her delicate weight, trembling hand tickling the banister. She looked at the crack under Ana’s closed door, devoid of the strong sunlight outside, a dim flittering grey movement. She reached the upper floor and turned the handle, finding more dim within, and the hazy outline of Ana’s shadow by the closed blinds.

Ana turned around, her dark watery eyes filled with fear. Octavia felt the need to offer an explanation for her intrusion.

'It's that I hadn't seen you all day, I wondered…'

'Were you about to leave for the rations?'

'Of course, I hadn't forgotten-'

'Well don't, we have plenty here.'

'What? It's no problem, the whole thing with Paulo…'

'It's not about that: don't leave the house.'

'But if I don't leave we won't have enough food.'

'I've only been eating half of my share. We have more than enough for a few days.'

Octavia moved towards the window and sure enough, a gaunt shadow filled Ana’s hollow cheeks. Octavia folded her arms tightly across her chest.

'But I don't understand.'

'Then I'll show you.'

Ana took Octavia forcefully by the arm, drawing up the blinds. She winced, trying to work out what she was supposed to see. Ana looked at the margin of her book, turned shiny grey by endless tally marks in pencil. She ran a finger down the page.

'There's a soldier about six foot tall with dark curly hair, walking to the left.'

'Yeah, how did you know that?'

'I've been here watching them. I figured it out.'

'But why? Ana, come downstairs, let me get you something to eat.'

'They know what you tried to do and now they're planning something.'

Octavia moved her head away from the window to look Ana squarely in the eyes.

'Do you think they believe all that ancient bullshit? If Paulo was stupid enough to tell the other soldiers that he came here, they'll think I'm some sad old housewife driven mad with loneliness. Stop this and come downstairs to eat while I'm out.'

Ana clutched her head, ‘No! You can’t.’

'Stay focused.'

'You're the only two that I have now and I can't let you be in danger. I've lost two sons, Octavia, I've lost them.'

A loud thud, followed by a child crying. Octavia flew down the stairs and out the front door and found the source of the screaming in a little heap in the tall, dry grass. She kneeled down beside him and checked the red, grassy knee he was clutching. Well, he hadn’t broken anything. She sat cross-legged on the ground, picked him up and brushed his hair with her closed hand, whispering ‘Shh, shh.’ The passing guard moved towards her but she shook her head, embarrassed and holding her son with crushing love, rocking back and forth. She heard ‘I need you alive, I need you alive, I need you alive’, but what she didn’t know was why: her son would be worth much less as a spiritual bargaining tool if he were dead. Octavia, unable to bear her own thoughts, started crying with greater volume and much more furiously than her surprised little son, whose own emotional rapture began to drown out.

March 3, 2014

Findesferas Part 6

Juan

'Ooohhh Atyrá, place of love and lauuuughter…' Juan was in ultimate boredom mode, inventing a song without knowing where it was going.

'Land of hope and justice, we will meet lots of soldiers and carry Paraguay to victoreeeeee!'

If Matías were with him he would say ‘Oh, come on, Juan! If you’re going to start that crap at least make an effort to get it rhyming. The tune will have to go as well, it’s no good.’

'Um… Ooohhhh Atyrá… Ok. Let's try… Atyrá's where I live, I live there all the day.'

Atyrá was on the brain because it was right in front of him, along the tree-lined streets, there within the hour.

A pleasant breeze kept him away from madness, and he sauntered along the street listening to the birdcall.

He came up to the city entrance. A broken, soot-clogged sign had been hanging up by two strings, but one of them had broken and the sign swung around in the breeze, obscured by the dirt:

"BIENV IDO A YRA

dad limp , sal able y pr uctiva”

Welcome to Atyrá, a clean, wholesome and productive city.

Atyrá used to be the cleanest city in the whole country, but it didn’t look that way anymore. Little houses were caked in thick soot, the pavements black and dirty. The warmth of the streets could be felt through the ever-thinner soles of Juan’s boots. The air was as thick as in Ypacaraí, but this did not feel like a city going about its business. There was no one around. Dead. So much for finding other soldiers and getting back to it. Juan was relieved. One day alive, another day alive. He gravitated towards the church, the highest building around, not saying a word. There was a scent of flowers and dry grass drifting up from the house gardens, friendly and familiar. With no flag atop the church to signify safety, he couldn’t relax yet. Juan spotted a man patrolling the roof, and hid himself in the shade of the tree. Another man appeared on the roof. They waved to each other. They were striking up a friendly conversation, talking away for some time, and Juan began to feel less threatened, but still he observed from his hiding place. One of the men on the roof looked puzzled, and Juan shuddered when he pointed directly at where he hid behind the tree.

'Shit! What do I do?' said Juan to himself, so used to having his brother by his side to give him advice, 'I'll stay here for a while… but they clearly know I'm here, he pointed right at me…but I'm going to wait… how will that help? I could…'

’Hey!’ shouted one of the men from the roof, ‘I can see you, there’s no point in hiding. You’re a soldier, right?’

Matías would have stood up and walked into the street. Juan would have to be his own Matías for now.

'Yes, I'm fighting for Paraguay. I came here because the rest of my troop died, and I lost my brother. I'm looking to get back out there.'

'You're fighting for Paraguay? But which side?'

'Which side are you on?'

'…I can't remember.'

'Well when you do, I'm fighting for that side.' They were both getting lightheaded from the need to keep shouting to each other.

'Nice try. You'll have to meet the field marshal first, he'll decide what to do with you.'

'The… the field marshal's here? Can you take me to him?'

'No need. He's probably coming to you now. For your own good, do not let him see your back. If he decides that you’re okay, see you later.’ The man reduced his volume as he spoke, such that the “later” was addressed to someone not two inches from his face. He turned around and disappeared over the brim of the rooftop. The other man on the roof had his arms crossed. He was smiling and shaking his head. He had been doing so for the whole conversation. He started whistling two notes, over and over, like a lullaby. There was a loud rumbling from the top of the street, the sound of a chainsaw or an engine, but how was this possible? The sound turned into a noise which grew to cacophonous proportions as a train of strange wooden carts with what looked like furnaces on top came round the corner, and the sound reverberated through the ground and shook the trees. On the carts were a huge number of soldiers, steely-eyed and serious browed, but haggard looking: all the fat had been chiselled out of them. The petals that gave off such a pleasing smell shook back and forth and began to fall to the floor. A portly man was posing on the front of the first cart, in Napoleonic attire, arm raised in salute. As the train approached, Juan returned to the tree trunk for support, slinking down, hands pressed against his ears, pushing the arms of his glasses into the sides of his head, eyes fiercely closed.

'Welcome!' growled the portly man. Black smoke puffed out of the many furnaces, a fierce heat glowing inside. The sound was insidious. It wheedled through Juan's hands and shook his eardrums. The train of carts stopped right in front of his feet, and the man peered down at him.

'Oh yes, a new soldier yes, is that what's happening is it? How many of you is there, young man?'

'Just me.'

'Right then. Paraguayan?'

'Yes.'

'For which side?'

'Paraguay.'

'It's like that is it?'

The man stared at him, drinking in his unflinching features, Juan desperately trying not to twitch as the marshal looked him up and down as if to say ‘Who do you think you are?’ He held onto a wooden pole on the cart and leaned dangerously off the front, about to fall, bringing himself closer to Juan, the rest of the soldiers looking straight ahead, not noticing what was happening.

Juan was close enough to smell whisky on the man’s breath as he said ‘Good. Just how we like it here. Splendid! One more is it? Fantastic! Then we’ll be two hundred and one, why not? I think it a fine number!’

He hopped off the cart and grabbed Juan’s hand in his, shaking it vigorously. Juan was shocked, dusted off his trousers with his free hand and squinting out the sunlight through his glasses.

'My name is Juan. Nice to meet you sir.'

'Juan! Fine name indeed for a fine gentleman. I'm the field marshal, and these are my soldiers.'

The marshal continued to shake Juan’s hand, beaming his smile.

'Right, hop on a cart and we'll take you back to the base. Oh and do make sure and meet my family, we've got my mother Juana, brother Venancio and my sisters Inocencia and Rafaela back there, love them dearly so I do, get yourself acquainted young man.'

'His family were with him? With all these soldiers?' thought Juan. He doubted the marshal's mother was a fighting woman, and thought it a bit dangerous to take civilians along.

The marshal jumped up onto his cart and nodded at one of his soldiers to start up again. The soldier tugged on a lever and the furnace blazed hotter. Another soldier was at the back of the cart, pulling with all his strength on a lever to change the direction, and the sound of the furnace made the effort heard. The marshal now shielded his eyes from the sun and peered around, like a brave captain on the front of a ship, fit for painting. One by one, the carts started to turn around, and by the way the soldiers looked at Juan, he didn’t feel like jumping onto any of the carts. He tried to see how far the connected carts stretched back, then snapped his gaze back to the marshal in case he had accidentally shown the man his back. He started to get nervous until the last cart turned around, and he noticed the space left for him, jumping on without great difficulty.

As the cart began to shift, Juan adjusted his balance, and embarrassingly grabbed at one of the soldiers to steady himself over a particularly large bump in the road. Behind him were large cages, like those of a travelling circus show for the prisoners of war. A chain of people sat in a semi-circle in the first cage, staring up at him meekly. Juan caught the eyes of an older woman, and jerked his head away, not wanting to engage. What were they, Argentinian? They didn’t look like Brazilians. He spied at them out of the corner of his eye. The marshal was quizzing him about his allegiance, so they could be rogue Paraguayans, but… wait, there were… three women, one man… meet my… mother, brother… They looked about the right age…

'Are you the marshal's family?' said Juan. The mother smiled at him.

'Yes dear, that's us. What's your name, son?'

She had a thin, wrinkly face, kind eyes, grey hair flat and dragged down. In her traditional Paraguayan dress, delicate lace but dirt-stained, she looked like a doll, tired and small on the floor of the cage.

'I'm Juan.' He withstood the impulse to offer her his hand through the bars.

'Nice to meet you, Juan.' The rest of the family looked glumly at the floor, ashamed.

'So… are you all imprisoned?'

'That's right.'

'Why is that?'

'My son thinks we've been conspiring against him, but…' she was obviously pained, 'He's our family, I'm…' she composed herself, rolled her shoulders back and sat up straight.

'I was so proud of him.'

The last of Juan’s boldness was drained from all the new interactions, so he nodded at the family, and slowly turned around to face the direction of the train, thinking about how easy it would for him to fall out of favour with the marshal.

Findesferas

Two large grey circles elegantly overlapped a little like a colourless Venn diagram. The doorway was a rounded lower case m shape: then he had arrived. Juan was about to enter the captain’s office, meet the man who ran this whole vast ship of unknowable proportions, father of the nervous chattery girl who blabbered away their lunch hours, but unbeknownst to him, sang their praises in her free time. It would be great to have the captain on his side, but Juan was already resigned to his meek impression on men of that… importance, those men who were men and not some pale spirit in the body that could biologically be indentified as a man, for that was Juan, and people tended to see it. What they didn’t often see were the other qualities he had to offer, deep compassion and a sparkling emotional sensitivity, but men who were men didn’t want these things, so they thought. Men who were men conquered things and ate big chunks of meaty things, they couldn’t find space for the qualities of Juan, so he thought. But as the Venn slid apart, and Juan gingerly paced through the ‘m’, he was entering the domain of a man who was to be of great importance in the shaping of Juan.

There was a heady scent of strong aftershave, which made Juan question the last time he had even smelled anything on the ship: cold, industrial extractor fans whisked away any trace molecules of odour in every room. There were none here, which heightened the pleasantness of the captain’s smell. Blinding strip light filled the room, but the bulbs were nowhere. The light blasted the captain’s back, and his felt uniform looked like a painting in the harsh contrast. His salt and pepper pomaded hair was pulled into a rigid short ponytail, and as he swung around and the artificial gravitational force acting on his wide chest had a second delay on the turn, before swinging notably like a pendulum, Juan wrinkled his nose to think of the word ‘corpulento’, a word so fitting yet so unpleasant, because it reminded him of cuerpo, corpse.

Juan was met with a beaming smile and an overzealous handshake: ‘Ah, so here’s the man! Here he is! A pleasure my man, a pleasure to meet you!’

Juan accepted the handshake with one hand and gingerly pushed his glasses up his thin, sharp nose. ‘Yes, it’s… it’s nice to meet you too, sir.’

The handshake stopped, the captain froze. ‘Sir… Sir! Oh, I like that. Yes, you’ll go far my dear boy, you’ll go far…’ he strode over to a stainless steel cabinet, and started moving some objects around in it, unseen to Juan. ‘So tell me. What’s your situation? Who’s here with you?’

Juan’s hands fell into a loose clasp behind him. ‘Well, it’s just myself and my sister-in-law, Octavia.’

'Sister-in-law,' the captain was talking into the cabinet, clinking some glasses together, 'and where's the brother?'

'In Paraguay, with the rest, fighting the good fight and all that', said Juan, with a recognition of how trite the story was beginning to sound, but not without a familiar tinge of sadness. The captain emerged once again, with a whiskey glass half-full of a thick black liquid on ice. Juan thought it strange that he hadn't been offered a drink, but at the look of it he wasn't all that thirsty anyway.

The look on the captain’s face was of that intense stern consideration that is sometimes seen in the faces of older gentlemen, an exaggerated perplexity out of respect for the complicatedness of someone’s situation. ‘Yes, well it’s true, we’re all making sacrifices. Just me and Juliana here, very lucky we can spend so much time together… Unless she’s with you and Octavia, then she isn’t to be disturbed.’

'That's actually why I wanted to meet with you. You don't happen to know where she is?'

'Of course I do! I saw her yesterday, don't you worry about her, she can't stay away from you, she'll be back before long.'

'Oh? We always got the impression we were boring her, I don't know why she would want to hang out with us, don't think we're very cool…'

'No, no, she's told you that so she isn't embarrassed. She's very fond of you both, always telling me “They get it, they totally get it.”’ The totally was drawn out in an Americanised manner, illustrating that the captain himself did not “get it”. The room was taking on a strange odour, like dust, rubber and burning plastic, and as a result Juan was trying hard to maintain his look of soft politeness, nose twitching a bit too much.

'Well, that's very kind of her to say. Very insightful girl is Juliana, packed full of ideas.'

'She is that, yes, but they do seem to spill out of her. Got no focus. Never found an outlet for it all back on the planet. I don't fret about it too much though, I know she'll be put to good use soon.'

'No doubt.'

Small talk on The Findesferas was a very different deal. There was no weather to discuss after all, and everyone ate pretty much the same thing apart from Juliana. All the hobbies a person could have were limited too, so talk had to get bigger and faster. The most common form adopted was “future kindness”: someone would speak about his or her plans for the future, and the listener would say nothing about the hopelessness of having a plan at all. People became much closer on the ship very quickly. It was… Juan made the connection with the odd smell in the room and the swirling of the captain’s thick crystal tumbler, and saw him drinking in the smell before taking a murky sip.

'Do you mind me asking… what is that you're drinking?'

Absent-mindedly, the captain let out a ‘Hm?’ then eyes lit up with a ‘Oh, it’s um… it’s crude oil, Juan.’

Perhaps it was a bit early to get this man’s sense of humour? Or was it an old man drink Juan was unfamiliar with?

'Crude oil, sir?'

'Yes, you know, crude oil.'

'But isn't… I mean it isn't… should you be…? Isn't that bad for your health? In fact I'm pretty sure you'll die if you keep drinking that.'

The captain strode round his desk of glass and steel, bolted to the floor, look on his face like he was holding in a snicker, strode round to stand not a foot away from Juan.

'Juan, my boy, don't you worry about me!' He raised his eyebrow haughtily. 'You know, my wife used to bathe in the stuff like Cleopatra, and take it from me, it kept her mighty young.' Craning over the desk, he articulated very slowly, 'I'll die when the oil does.' One of those winks where the cheek pulls up to meet the eyebrow.

'Right, sir, well… you know yourself. Pleasure to finally meet you. Best get back to Octavia, she'll be wondering where I am.'

'Do that, Juan, you head back. Great to get a little chat on the go. You and Octavia are welcome to drop by here when you can. I do have a lot of duties, mind, but I'll make space for friends of Juliana. There's a lot on my mind you know.' His eyes narrowed, 'I'm thinking of some ways we can help each other out. Do come back soon.'

'I… I will do, captain. Goodbye for now.' Juan was confused about the etiquette, gave an awkward staggered half-bow and tried not to turn around for as long as possible as he side-stepped back towards the circular door, and when he heard the swishing sound of the two metal circles sliding open on either side, he turned away and headed out. He could still here the clinking of the ice in the glass of crude oil, and feel the captain's eyes like burning lasers on the back of his head. There was still room for surprises in The Findesferas, it seemed.

Juan went back to his room. He tried to write but came up short every time. He felt too guilty, and re-read the same stanza over and over, trying to make some sense of the words, scratching his pencil across the scrap paper so many times that it became silvery with long holes torn through it. Without knowing he had been holding his breath, Juan released a large gasp and slouched down, head touching the paper on the desk. The door slid open, and there she was. He held his finger to the person at the door so that they dared not break his inspirational streak, He raised his head and turned in surprise and embarrassment to see Octavia there, large grey streak imprinted on his forehead. She would definitely not stand for such an action. Luckily for him, she was on a peacekeeping mission.

'Hello, Juan, good to see you're getting back into poetry.'

'Well, once you get over the eternal loneliness, bleakness, darkness of space, there's actually a lot of beauty to it. And if not, there's still the bleak dark things to write about.' He smiled kindly, and deftly readjusted his shirt collar, which had slipped into his v-neck as the result of hours of sitting in a slovenly spine-crunching position. Such was the physical price of inspiration.

Octavia noticed a small note on thick cream paper sitting on the desk beside Juan, and picked it up:

You can’t ever save me. Clear your head, for your own sake. You can do it.

J

She frowned, turned it over.

167…3…9

'What's this?'

Juan snatched it back from her, ‘Oh don’t worry about that.’

She bowed her head a little, brushed the hair on the back of her head. It was no good, she was too curious now. 167…3…9.