Jonathan Chait's Blog, page 135

December 29, 2010

Is the Favorite to Replace Larry Summers Too Close To Wall Street?

[Guest post by Noam Scheiber:]

If you’ve spent much time talking to Treasury officials over the past two years, you’ve probably heard them joke that Gene Sperling, a counselor to Secretary Tim Geithner, is the department’s in-house populist. What makes this funny (insofar as wonk humor can be funny) is that Sperling isn’t exactly your classic pitch-fork wielder. He was director of Bill Clinton’s National Economic Council (NEC) in the late ‘90s, a period when the White House got pretty good marks for its understanding of business and the broader economy. But as Sperling often speaks up for the little guy in internal deliberations—he was one of the administration wonks most concerned about executive pay, and he argued passionately for saving Chrysler—there’s certainly enough truth to the label to make it stick.

Sperling’s record has suddenly become highly relevant because, depending on who you talk to, he’s either a leading candidate or the leading candidate to replace Larry Summers as head of Obama’s NEC. In light of the forgoing, you might also think he’d be a liberal favorite for the job. But Sperling has recently taken some lumps in the Huffington Post for his alleged sympathy for bankers and his ties to former Clinton Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin. “By appointing Sperling,” one of the pieces begins, “the president would fuel perceptions that his administration is overly close to Wall Street, installing a policymaker who has not only overseen monumental deregulation of the financial sector, but has also collected hefty paychecks from its leading firms.”

Which of these images better fits the man who could become Barack Obama’s chief economic policy broker? As it happens, Sperling’s name has come up in a number of conversations I’ve had with admnistration officials while reporting an unrelated piece these last few months. I think I can offer some insight.

The Huffington Post bases its concerns about Sperling on two broad data points. The first is that he made over $1.5 million in consulting fees from various financial services companies in the 13 months beginning in January of 2008, including almost $900,000 from Goldman Sachs. The second is that he was NEC director while the Clinton administration helped deregulate the financial sector in the late ‘90s.

I don’t know a ton about Sperling’s consulting work, though it’s worth pointing out that the Goldman gig involved creating a program to teach business skills to poor women in the developing world (and is widely regarded as a success). Granted, Goldman obviously wasn’t doing this out of the goodness of its heart—the $100 million it committed was a lot for a charitable cause, but a bargain for a company with billions in profits looking to buff its image. The point is just that running an education program—however lucrative it may be for everyone involved—is somewhat different from hawking dodgy mortgage securities, or whatever comes to mind when you hear the word “Goldman.”

As for Sperling’s experience in government, this seems to be a much more useful topic for exploration, but the Huffington Post piece adds little to our understanding. For example, while it’s true that Sperling was NEC director when the Clinton administration ushered in some unfortunate deregulatory changes, pretty much every account I’ve either read or heard from people involved confirms that the Clinton Treasury Department had enormous autonomy on the issue; Sperling was a marginal player at best. (A more apt critique would ask whether we should worry about Sperling ceding authority over a major issue like this in the future, but that’s not the concern the Huffington Post pieces raise.)

Of course, that only tells us what Sperling wasn’t involved in. What about his instincts when he did work on issues of interest to Wall Street? This is the question my recent reporting has shed some light on. Sperling turns out to be the Treasury official who was most influential in helping persuade Geithner to embrace a fee on large financial firms to make the government whole after TARP, the vehicle for its various bailouts. The president unveiled the 10-year, $90 billion fee in January of 2010. Wall Street promptly howled.

The whole process began late in the summer of 2009, when Sperling seized on the fact that that the law establishing TARP required the government to recoup any un-repaid funds by 2013. His view was that, rather than put off the moment of reckoning and hope it went away, Treasury should demonstrate its commitment to holding Wall Street accountable. The added beauty of a fee leveled annually for 10 years is that it could create both a precedent and an infrastructure for a tax on big banks—which would help discourage them from ballooning in the first place, something most impartial observers agreed was useful. This, and not just the money itself, was presumably what got Wall Street so exercised.

There’s one other element of this that came up in my conversations with several administration officials: As the administration fleshed out the idea during the fall of 2009, the economic team focused on two basic approaches. The first was to levy the tax on certain bank liabilities—basically, their debt. The second was to levy it on profits (along with compensation above a certain threshold—the idea being to prevent banks from finagling a lower tax by converting profits into compensation).

Sperling and several administration economists favored the latter, which had the advantage of simplicity (the IRS could calculate it relatively easily), but which was likely to provoke an even harsher reaction from Wall Street. The administration eventually went with the liabilities approach, which required regulators to make a relatively complex calculation, but was a bit more narrowly targeted at the behavior you'd hope to discourage (i.e., taking on a lot of debt to fuel growth) and would be an easier sell to foreign governments, with whom it would be important to coordinate. It’s worth noting that, once Geithner decided to go this route, Sperling, who was overseeing the process internally, shifted gears and helped get the proposal out the door quickly—the kind of quality you’d want in an NEC director.

Long story short: This hardly strikes me as the profile of a man out to do the banks’ bidding. Sperling may not be the kind of populist who makes the average HuffPo reader swoon. But I doubt his record as a policymaker inspires much chuckling on Wall Street.

Noam Scheiber is a senior editor for The New Republic and a Schwartz Fellow at The New America Foundation.

WHITE HOUSE WATCH >>

Zombie Lies Try To Eat Krugman's Brain

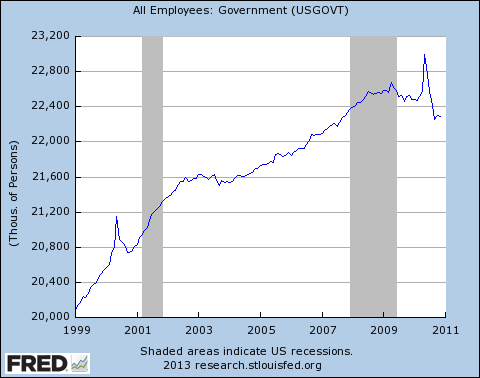

A couple weeks ago, Tim Pawlenty accused President Obama of creating a massive upsurge in government jobs while private sector job growth has dwindled:

{G]overnment, which, thanks to President Obama, has become the only booming "industry" left in our economy. Since January 2008 the private sector has lost nearly eight million jobs while local, state and federal governments added 590,000.

Paul Krugman pointed out that this was totally false. Government employment has fallen. Pawlenty was citing a figure from June, but even that reflected a temporary spike due to Census hiring, not anything Obama did:

That spike from last year parallels the 2000 Census-related employment spike. So Pawlenty was using a number that was no longer true, and was deeply misleading even during the brief window when it was, in order to support a false claim about Obama's record of government jobs.

Now Veronique de Rugy -- whose post for Andrew Breitbart turns out to be the source of Pawlenty's false data -- goes after Krugman with a new post at National Review. I realize that interceding on Krugman's behalf in an intellectual spat with Veronique de Rugy is a bit like Nato sending troops to aid the American invasion of Grenada. But the sheer comedy of de Rugy's argument makes me unable to resist. She writes:

Of course, we can argue over how much the government grew during the recession or whether Obama is technically responsible for the shrinkage or growth of some or all parts of government. However, it is reasonable to say that, in contrast to the private sector, government employees have been relatively sheltered since January 2008: Only a small portion of local governments’ workforce lost their jobs and federal and state employment grew. It is also reasonable to say that for almost a year-and-a-half, while the private sector was shrinking, the government was growing. These are the points I think governor Pawlenty was trying to make.

Nothing in this passage, or in any part of her post (read it!) contradicts anything Krugman wrote. She leaves untouched the fact that he cited a statistic that was not true, and that even during the brief period when it was true, his interpretation of it (Obama created lots of government jobs) was completely false. Instead she argues that Pawlenty "was trying to make" the case that government jobs shrunk less rapidly than private sector jobs. If Pawlenty actually wrote this, which he didn't, it would be a meaningful point if there were some fixed pool of unemployment, and any new government job subtracts a private sector job, which of course is not true, either. She also writes that Pawlenty was "trying" (without evident success) to make the point that at one time government employment had risen while private employment had fallen. Apparently somebody hacked into his computer to add the implication that this resulted from Obama's insatiable thirst for big government rather than the decennial Census that he had no role in authorizing.

The Most Attention Money Can Buy

Politico reported the other day that Wall Street is upset at the Obama administration. It seems to me as if the hurt feelings of this tiny (albeit very rich) segment of society has received enormous attention in the media. After all, there are a lot of groups in this country at least as numerous as CEOs and with no less cause for grievance, and yet we hear about their wounded egos far less often.

I asked intrepid Reporter-Researcher James Downie to tabulate how many times Politico alone has run some version of the "business upset at Obama" story.

Then answer turns out to be, a lot of times:

“Class warfare returns to DC,” by Jeanne Cummings, 2/26/09

“Bankers to Obama: stop trashing us,” by Victoria McGrane, 2/27/09

“Inside Obama’s bank CEO meeting,” by Eamon Javers, 4/3/09

“Regulation War: business in crosshairs,” by Jeanne Cummings, 5/26/09

“Has anything changed on Wall Street?” by Eamon Javers, 9/13/09

“President Obama: recovery continues,” by Eamon Javers, 9/14/09

“Chamber of Commerce hits President Obama on financial reform,” by Victoria McGrane, 10/13/09

“Donohue: I’m trying to be very positive,” by Jim Vandehei and Mike Allen, 10/26/09

“Execs disinclined to fall into line,” by Eamon Javers, 12/16/09

“Chamber chief attacks Obama agenda,” by Lisa Lerer, 1/12/10

“The Wall Street-Washington divide,” by David Rogers, 4/29/10

“Valerie Jarrett: Business is really not a partisan issue,” by John F. Harris and Eamon Javers

“Derivatives sour Wall Street on Obama,” by Ben White, 5/22/10

“Wall Street plans payback for reg reform,” by Ben White, 7/6/10

“White House seeks to flip anti-business rep,” by Ben White, 7/8/10

“Few from Wall Street attend bill signing,” by Ben White, 7/21/10

“Obama’s words sting CEOs” by Ben White, 7/22/10

“New business plan: crushing Dems,” by Jeanne Cummings and Chris Frates, 7/28/10

“Wall Street donations drop for Dems,” by Erika Lowely, 9/8/10

“Foreign firms: quit bashing us,” by Jeanne Cummings, 9/28/10

“White House hopes for business help,” by Mike Allen, 9/29/10

“Chamber: Dem regulations onerous,” by Chris Frates, 10/6/10

“Wall St. cash flow imperils Democrats,” by Chris Frates and John Maggs, 10/12/10

“Business: Barack Obama’s Outreach Not Enough,” by Ben White and Jeanne Cummings, 11/26/10

“Obama and business: December thaw?” by John Maggs, 12/9/10

“Republicans beat President Obama to the boardroom,” – by John Maggs, 12/11/10

“Obama to CEOs: Let’s talk,” by Abby Phillips and John Maggs

“Obama and Wall Street: Still Venus and Mars,” by Ben White, 12/28/10

National Review Denounces Republican Health Care Plan

Daniel Foster has an item at National Review headlined:

Early Word: Obamacare High-Risk Pools Unpopular, Expensive

It links to a story showing that state-level high risk health insurance pools, which cover people with preexisting conditions, are attracting few takers and costing more than expected per person. What does this mean? Here's what. During the health care reform debate, Republicans consistently advocated for high risk pools. Here's some commentary from National Review:

"GOP lawmakers can immediately provide much-needed help for the uninsured who have preexisting conditions by providing full funding for state-run high-risk pools (preferably in combination with offering long-overdue tax-breaks for the uninsured, as Ross Douthat advocates). Obamacare would address the problem of covering those with expensive preexisting conditions by mandating that insurers offer them coverage in the regular market, at artificially low rates...[T]he high-risk-pool approach makes colossally more sense."

James Cepretta and Thomas Miller:

"A better alternative, and one much less disruptive to current policyholders, would be to provide adequate and sustainable funding of high-risk pools. Today, most--but not all--states have subsidized high-risk pools that are intended to reduce premiums in the individual marketplace for people with expensive preexisting conditions. They are the most common way for states to comply with HIPAA's requirement that workers leaving group plans have access to the individual market."

“Obamacare is supposed to establish high-risk pools to help people with preexisting conditions — as a short-term measure until the new entitlement and regulations kick in. Republicans have advocated such high-risk pools, too, but as a way to help sick people without ruining private insurance.”

“[Timothy] Noah argues that subsidized high-risk pools are fine as a transition measure to be followed by Obamacare, but a terrible idea as a stand-alone. But most conservatives favor it precisely as a transition measure. They believe that if government allowed a robust market in individual insurance to develop, it would be easier for people to purchase cheap and renewable insurance policies before they got sick and the problem of “pre-existing conditions” would therefore diminish over time.”

National Review's editorial board:

"[The third part of the Pledge to America] is health care, where the Republicans...plan to work toward their own health-care reforms, including medical-malpractice reform, freedom to buy health insurance across state lines, and better-funded high-risk pools for people with pre-existing conditions...The pledge is explicitly a beginning to the lengthy task of providing conservative governance, and a very good one."

“States have conducted successful experiments with “high-risk pools.""

“After all, mandating the purchase of insurance is by no means the only way to address the problem of covering people with pre-existing conditions..[H]igh-risk pools can achieve this too, and without a mandate.”

Liberal health care wonks insisted that high risk pools tended to work very badly and were at best a stopgap solution. Democrats included some expanded high risk pools as a carryover, they-can't-hurt palliative until the full reform goes online. Obviously, they haven't done much good. But Othat hardly tells you that "Obamacare" has failed.

The Constitution Enabled Big Government

I realize I'm at risk of turning into an anti-libertarian blog, but Chris Beam falls for the conceit that the Founding fathers were libertarian:

“The Constitution was a libertarian document that limited the role of the state to society’s most basic needs, like a legislature to pass laws, a court system to interpret them, and a military to protect them."

John Vecchione corrects him:

George Washington belonged to the Established Church (Episcopalian) of the State of Virginia; he also was the chief vindicator of national power in the new republic. Thomas Jefferson determined to wage war by simply denying foreigners the right to trade with the U.S. So did Madison. What libertarian has ever thought the government could cut off trade between free individuals? Further, Thomas Jefferson and Thomas Paine supported the French Revolution. That revolution denied there was anything the state could not do in the name of the people. Jefferson never repudiated his support for that tyranny and Thomas Paine was only slightly more dismissive even after it nearly killed him. ...

If ever there was a libertarian document it was the Articles of Confederation. There was no national power. The federal government could not tax. Its laws were not supreme over state laws. It was in fact, the hot mess that critics of libertarians believe their dream state would be… and it was recognized as such by the majority of the country and was why the Constitution was ratified. The Articles of Confederation is the true libertarian founding document and this explains the failure of libertarianism.

Gordon Wood's review essay about the ratification of the Constitution adds a lot of historical depth to this point. The original debate over the Constitution bore eerie parallels to the current debate, with populists in the heartland distrustful of central authority pitted against coastal elites:

The great irony, of course, is that the Anti-Federalist ancestors of the Tea Partiers opposed the Constitution rather than revered it.

The Insufferably Pompous Senate

The Washington Post reports that Scott Brown ruffled feathers in the Senate:

After his election, he turned some senators off by exhibiting a swagger unbecoming a freshman and flipping closed the briefing books that colleagues read from in the chamber.

Good heavens! Swagger! Flipping closed the sacred briefing books! He has violated the hallowed rites of discipline and obedience:

December 28, 2010

Lanny Davis and Ivory Coast, Ctd

[Guest post by Isaac Chotiner]

Last week, I wrote an item criticizing Lanny Davis for representing the government of the Ivory Coast. That government has recently been accused of ignoring election results and clinging to power illegitimately. Davis sent TNR the following in response to my post:

I am responding to a factually inaccurate assertion in an opinion commentary posted by Isaac Chotiner on this blog last week.

Mr. Chotiner never called me to check the accuracy of his use of the word “shilling,” which is defined in dictionaries as “promoting” with “duplicity” or as a “decoy.” It is an embarrassing error by him, since I was available to him and everyone for calls. Had he called me, I could have directed him to the public (and posted on the Internet) statement from press conferences held December 20 and December 21, which directly contradicted the word “shilling.” That statement said, in part:

I have not been asked by the Ivorian government to try to prove to the world community who won the election in the Ivory Coast, or who is right or who is wrong.

My willingness to “present” the evidence to the media of voter fraud in the north of the Ivory Coast as perceived by the government of the Ivory Coast, without validating the truth of those assertions, does not contradict the above sentence, which I have repeated many times. This is precisely what I stated in the above statement.

In fact, other sections of my statement, as well as the rest of the quotes in the New York Times article of December 23, 2010 (Mr. Chotiner quoted one sentence from that article but not all the others), make clear that my major role is to assist in finding a peaceful solution to the crisis, avoiding human rights abuses and bloodshed. As I stated on December 20 and 21, 2010:

…I am counseling the Government in order to peacefully resolve the crisis in a spirit of reconciliation, transparency, and through mediation, recognizing the concerns of the international community.

…I have further advised the Government that they should seek the assistance of an outside mediator of acknowledged integrity and objectivity, such as former South African President Mbeki, who successfully mediated the accords that helped resolve conflict in the Ivory Coast in 2005, or some other similar world leader who is acceptable to all parties, so this crisis can be resolved without any further violence or instability.

As the Times quoted me saying on December 23 (again, a quote omitted by Mr. Chotiner and thus not read by the readers of his commentary): “[Mr. Davis] viewed himself not as an advocate but as a ‘conveyor belt’ to pass information about Mr. Gbagbo to the administration and the world.”

I also note President Gbagbo’s speech in the Ivory Coast that he will not tolerate violence and abuses and condemns them, that he has called for a full investigation by objective authorities into reports of abuses, and for anyone responsible to be prosecuted to the fullest extent of the law.

A commentator is entitled to his opinion, even when he engages in personal attacks and schoolyard name-calling (I must admit to being curious as to how he can accurately describe my role in defending President Clinton as a counsel and friend as that of a “Clinton-era hack”). But according to most editorial page editors I have consulted over the years, responsible journals do not permit personal attacks based on false or misleading assertions of fact.

I wish I could describe further what I have been doing night and day for the last week and with whom I have been working and talking throughout this period in order to try to bring a peaceful solution without further bloodshed. Maybe someday all the facts can be told concerning my role. But I can assure readers of TNR as well as all others that my role has been consistent with my terms of engagement with the Ivory Coast government and my statement of December 20 and 21—indeed, without my engagement by the government, I could not have been doing what I am now doing.

Davis says he does not intend to prove who won the election in the Ivory Coast, and yet in the original New York Times piece that I quoted, there appears the following:

Mr. Davis, who helped defend President Clinton against impeachment, registered with the Justice Department earlier this month as an agent for Ivory Coast who would be paid $100,000 a month to “present the facts and the law as to why there is substantial documentary evidence that President Laurent Gbagbo is the duly elected president as a result of the Nov. 28 elections.”

As far as I am aware, Davis has never directly disavowed this statement. Moreover, even if Davis is not saying “who is right or who is wrong,” that open-mindedness stands in contrast to the United Nations and numerous human rights groups who have declared President Gbagbo’s opponent the legitimate victor, and are asking Gbagbo to step down.

Davis is entitled to argue that he is merely acting as a peacemaker (albeit one taking a large fee), but I think the world can do better than a peacemaker who blindly accepts President Gbagbo’s absurd statement about refusing to tolerate violence, as Davis does in his response to me. As we speak, opposition activists are being detained, and there are credible reports of political murders.

Finally, it is worth noting that this is not Davis’s first time working for a government accused of serious human rights violations. Earlier this year, according to The New York Times, Davis accepted a contract of one million dollars from Equatorial Guinea’s government. The president of Equatorial Guinea, Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo, who has “served” for three decades, is also accused of serious violations of political and human rights. In that case as well, Davis presented himself as someone who was merely trying to improve the situation by counseling a government to do the right thing. In both Equatorial Guinea and Ivory Coast, I would question whether someone being paid by people accused of serious human rights violations is the best messenger for peace.

Paul Ryan And Ayn Rand

Another part of Christopher Beam's piece on libertarianism that caught my interest was this bit about Paul Ryan and his deep affinity for Ayn Rand:

Representative Paul Ryan, also of Wisconsin, requires staffers to read Atlas Shrugged, describes Obama’s economic policies as “something right out of an Ayn Rand novel,” and calls Rand “the reason I got involved in public service.”

Earlier this year I wrote about Ryan and his deep devotion to the philosophy of Rand, particularly her inverted Marxist economic-political worldview:

Ryan would retain some bare-bones subsidies for the poorest, but the overwhelming thrust in every way is to liberate the lucky and successful to enjoy their good fortune without burdening them with any responsibility for the welfare of their fellow citizens. This is the core of Ryan's moral philosophy:

"The reason I got involved in public service, by and large, if I had to credit one thinker, one person, it would be Ayn Rand," Ryan said at a D.C. gathering four years ago honoring the author of "Atlas Shrugged" and "The Fountainhead." ...

At the Rand celebration he spoke at in 2005, Ryan invoked the central theme of Rand's writings when he told his audience that, "Almost every fight we are involved in here on Capitol Hill ... is a fight that usually comes down to one conflict--individualism versus collectivism."

The core of the Randian worldview, as absorbed by the modern GOP, is a belief that the natural market distribution of income is inherently moral, and the central struggle of politics is to free the successful from having the fruits of their superiority redistributed by looters and moochers.

Ross Douthat furiously objected, dismissing Ryan's relationship as him having "said kind words about Ayn Rand," as if he had merely offered pro forma praise at a banquet. I think at this point trying to deny Ryan's attachment to Rand is pretty hard to sustain. He's not requiring his staffers to read Ran because he thinks they need a good love story. And given that it's not just a teenage fascination but the continuing embodiment of his public philosophy, it's worth noting again that Rand is a twisted, hateful thinker.

What Do Economic And Social Liberalism Have In Common?

Chris Beam's interesting New York essay on libertarianism notes as an aside:

Libertarianism is more internally consistent than the Democratic or Republican platforms. There’s no inherent reason that free-marketers and social conservatives should be allied under the Republican umbrella, except that it makes for a powerful coalition.

Matthew Yglesias replies that, in practice, the division works reasonably well:

We should consider the possibility that the market in political ideas works is that there’s a reason you typically find conservative and progressive political coalitions aligned in this particular way. And if you look at American history, you see that in 1964 when we had a libertarian presidential candidate the main constituency for his views turned out to be white supremacists in the deep south. Libertarian principles, as Rand Paul had occasion to remind us during the 2010 midterm campaign, prohibit the Civil Rights Act as an infringement on the liberty of racist business proprietors. Similarly, libertarians and social conservatives are united in opposition to an Employment Non-Discrimination Act for gays and lesbians and to measures like the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act that seek to curb discrimination against women.

Let me refine the point a bit. The left-right division tends to center around the distribution of power. In both the economic and the social spheres, power is distributed unequally. Liberalism is about distributing that power more equally, and conservatism represents the opposite. I don't mean to create a definition that stacks the deck. It's certainly possible to carry the spirit of egalitarianism too far in either sphere. An economic policy that imposed a 100% tax on all six-figure incomes, or a social policy that imposed strict race and gender quotas on every university or profession, would be far too egalitarian for my taste. Soviet Russia or Communist China are handy historical cases of social and economic leveling run amok.

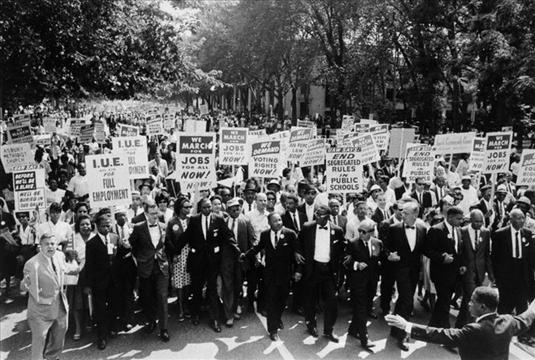

But in any case, there's a coherence between the two spheres. Liberals see a health care system in which tens millions of people can't afford regular medical care, or a social system in which gays face an array of discrimination, and seek to level the playing field. The inequality may be between management and labor, or rich and poor, or corporations versus consumers, or white versus black. In almost every instance, the liberal position is for reducing inequalities of power -- be it by ending Jim Crow or providing food stamps to poor families -- while the conservative position is for maintaining those inequalities of power.

Economic liberalism usually (but not always) takes the form of advocating more government intervention, while social liberalism usually (but not always) takes the form of advocating less government intervention. If your only ideological interpretation metric is more versus less government, then that would appear incoherent. But I don't see why more versus less government must be the only metric.

The one area where I think the liberal and conservative coalitions truly do not fit is foreign policy. I don't see any natural reason why the right should be more hawkish and the left more dovish. It's true that military expenditures compete with social programs for resources, but they also force higher taxes. Wars generally cause liberals to make the same kinds of arguments about futility and unintended consequences that conservatives make about social programs, while the reverse is true for conservatives. If you rearrange some key nouns, a Nation editorial on Iraq could be turned into a Weekly Standard editorial on health care reform, and a Weekly Standard editorial on Iraq could be turned into a Nation editorial on health care reform.

December 26, 2010

The Death Panels Are Real!

And they are spectacular:

When a proposal to encourage end-of-life planning touched off a political storm over “death panels,” Democrats dropped it from legislation to overhaul the health care system. But the Obama administration will achieve the same goal by regulation, starting Jan. 1. ...

"Advance care planning improves end-of-life care and patient and family satisfaction and reduces stress, anxiety and depression in surviving relatives,” the administration said in the preamble to the Medicare regulation, quoting research published this year in the British Medical Journal.

The administration also cited research by Dr. Stacy M. Fischer, an assistant professor at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, who found that “end-of-life discussions between doctor and patient help ensure that one gets the care one wants.” In this sense, Dr. Fischer said, such consultations “protect patient autonomy.”

Now the next step is to make them deathier:

Jonathan Chait's Blog

- Jonathan Chait's profile

- 35 followers