Gordon Urquhart's Blog: popesarmada25.blogspot.com

August 23, 2025

Focolare Movement: Vatican's Secret Service

Archbishop and Mrs Milingo

Archbishop and Mrs MilingoThis blog is possibly the first time that the fascinating story of the African former Catholic archbishop and thaumaturge Emmanuel Milingo has been revealed in full. Famous for his spectacular services of exorcisms and healings in Africa, and later in Rome, he was born in 1930 and - amazingly, given his controversial and stormy life - is still alive. It is a story that made the headlines worldwide and could be the basis of a John Le Carré or Ian Fleming novel. But its most compelling - and so far little known -aspect is the role played by the Focolare movement.

In 2001, Rev. Sun Myung Moon, founder of the Unification Church (better known as the ‘Moonies’), together with his wife Hak Ja Han Moon, conducted the marriage of Archbishop Milingo to Maria Sung ‘a 43-year-old matronly Korean acupuncturist’ (Milingo was 71 at the time). But then, after three months, heeding the call of Pope John Paul II, Milingo left the Moonies and returned to Rome. Here, the Vatican placed him secretly in the care of the Moonies' most suitable Catholic opponents, also esteemed by the Vatican as excellent jailers (according to Vaticanologist Sandro Magister, then working for L'Espresso ) and with James Bond-like secrecy skills.

Following the Pope's summons, for a year Milingo disappeared completely from public and media attention. His grand return to public life merited a most interesting article - Return of the Prodigal Son - in the independent English newspaper, The Guardian [1]. Milingo, The Guardian reports, along with representatives of the Vatican, appeared on RAI's Porta a Porta, interviewed by Bruno Vespa. But Milingo was not present in the studio. He spoke from ‘a secret location in the Roman hills’ - accompanied by ‘an ecclesiastical henchman’. According to The Guardian, 'Archbishop Milingo has just emerged from a year spent in penitential prayer and meditation in Argentina at a Capuchin monastery at a place called O'Higgins.' Along with the announcement of Milingo's return, the RAI program was also an opportunity to launch Milingo's new book, an interview with 'the Italian journalist, Michele Zanzucchi.'

Many details, but the essential one is missing. A secret place in the Roman hills? Centre of the focolarini. An ecclesiastical henchman? One, or a squad, of focolarini. O'Higgins? It may have been a Capuchin monastery long ago, but for decades it has been a Mariapolis of the Focolare movement. Now called Mariapolis Lia, it is surrounded by miles of open countryside in the middle of nowhere and therefore a perfect prison. Italian journalist Michele Zanzucchi? Born into a focolarino family and now a Focolare big shot. In short, behind the scenes, the whole story of Milingo's attempted conversion was orchestrated by focolarini - and, of course, as befits those masters of secrecy, all on the sly.

This is the whole truth. But the story fed to the media, as reported in The Guardian, was a version of the truth, but also - as it did not mention the perpetrators of these events - a pack of lies.

Unfortunately, despite this spectacular favor to Church and Pope by the focolarini, showcasing all their skills as prison guards, experts in undercover operations and public relations, in 2006 Milingo fled Italy and founded the group ‘Married Priests Now!’ After ordaining four married men as bishops, also in 2006 in America, he was excommunicated by the Vatican and in 2009 laicized.

Everyone who knows the Focolare movement from the inside knows it is a web of secrets, especially in its history. Milingo's secret is now revealed - thanks to those who can decipher it. But this begs the question: how many other astounding stories are there in Focolare history that outside the movement no one knows?

[1] https://www.theguardian.com/world/200...

Focolarini: Servizio Segreto del Vaticano

Arcivescovo e Signora Milingo (Maria Sung)

Arcivescovo e Signora Milingo (Maria Sung)

Questo blog e possibilmente la prima volta che sia raccontata in pieno la storia affascinante del ex-arcivescovo cattolico e taumaturgo africano, Emmanuel Milingo - famoso per i suoi funzioni spettacolari di esorcismi e guarigioni (nato nel 1930 e - incrediibilemte, vista la sua vita controversa e tempestosa - ancora vivo!) E una storia che potrebbe essere un romanzo di John Le Carré o Ian Fleming. Ma l'aspetto piu avvincente - e finora poco conosciuto - e il ruolo svolto in questa trama dal movimento dei Focolari.

In 2001, Rev Sun Myung Moon, fondatore del Unification Church (meglio conosciuto come i 'Moonies'), insieme a Signora Moon, hanno condotto lo sposalizio di Arcivescovo Milingo - con Maria Sung ‘una matronale acupunturista coreana’ 43-enne (Milingo aveva 71 anni allora). Ma poi, dopo tre mesi, ascoltando l’appello di Giovanni Paolo II, Milingo ha lasciato i Moonies ed e tornato a Roma. Qui, di nascosto, il Vaticano l’ha messo in cura dei più abili avversari cattolici dei Moonies, anche stimati dal Vaticano come carcerieri eccellenti (secondo esperto del Vaticano Sandro Magister, allora dell'Espresso) e con abilità di segretezza di James Bond.

Dopo l'appello del Papa, per un’anno Milingo e sparito completamente dalla vista del pubblico e dei media. Il suo grande ritorno alla vita pubblica ha meritato un articolo interessantissimo - Ritorno del Figlio Prodigo - nel giornale indipendente inglese, The Guardian [1]. Milingo, racconta The Guardian, insieme a rappresentanti del Vaticano, e apparso su Porta a Porta della RAI, intervistato da Bruno Vespa. Ma Milingo non era nello studio in persona. Si parlava da ‘un luogo segreto nelle colline Romane’ - accompagnato da 'un scagnozzo ecclesiastico’.

Secondo The Guardian, ‘L'arcivescovo Milingo e appena uscito da un anno passato in preghiera di penitenza e meditazione in Argentina presso un monastero cappuccino in un luogo chiamato O’Higgins.’ Insieme all'annuncio del ritorno di Milingo, il programma della RAI era anche l'opportunità di lanciare il nuovo libro di Milingo, un’intervista con ‘il giornalista italiano, Michele Zanzucchi.'

Molti dettagli, ma mancano quelli essenziali. Un luogo segreto nelle colline Romane? Centro dei focolarini. Un scagnozzo ecclesiastico? Uno o una squadra di focolarini. O'Higgins? Forse era un monastero cappuccino molto tempo fa, ma ora, come sappiamo bene, da decenni e una Mariapoli focolarina. Ora chiamato Mariapoli Lia, circondato da chilometri di campagna aperto nel bel mezzo del nulla e perciò una prigione perfetta. Giornalista italiano Michele Zanzucchi? Nato in una famiglia focolarina ed ora un pezzo grosso focolarino. Insomma, dietro le quinte, tutta la storia della tentata conversione di Milingo e stata orchestrata dai focolarini - e, naturalmente, tutta di nascosto come si addice a quei maestri della segreto.

Questa è - finalmente - l'intera verità. Ma la storia fornita ai media, come riportata dal Guardian, era fino a un certo punto “la verità”, ma anche - poiché non menzionava gli autori di questi eventi - un mucchio di bugie.

Purtroppo, nonostante questo favore spettacolare a Chiesa e Papa dai focolarini, mettendo in mostra tutte le loro abilità di guardie carceriere, esperti di operazioni sotto copertura e relazioni pubbliche, in 2006 Milingo e scappato dall’Italia ed ha fondato il gruppo ‘Married Priests Now!’ (Preti Sposati Subito!). Dopo aver ordinato quattro uomini sposati come vescovi, anche in 2006 in America, e stato scomunicato dal Vaticano ed in 2009 laicizzato.

Tutti quelli che conoscono il movimento dei Focolari dal di dentro sanno che e un grande mucchio di segreti, sopratutto nella sua storia. Il segreto di Milingo e ora svelato - grazie a quelli che sanno decifrarlo. Ma viene la domanda: quanti altri episodi stupefacenti ci sono nella storia focolarina, che fuori il movimento nessuno sa?

[1] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2002/oct/02/worlddispatch.italy

July 2, 2025

Facciamo un giudizio sobrio su Maria Voce, ex-presidente dei focolarini

Maria Voce - la defunta ex-presidente del movimento dei Focolari

Maria Voce - la defunta ex-presidente del movimento dei FocolariPrima di cantare le lodi, stile Focolari, sulla defunta ex-presidente del movimento, meditiamo su alcuni stralci di articoli di Pope's Armada 25 (fra poco 30!):

Il presidente del movimento dei Focolari: attacco furioso alle donne prete (Testo completo) (15 marzo 2021)In un'intervista del 2017 per La Stampa, il giornale italiano (vedi link sotto per l'intervista completa - disponibile in italiano e inglese), Maria Voce, allora Presidente del movimento dei Focolari, fece una dichiarazione straordinaria. Alla domanda sulle donne cattoliche che sentono la vocazione al sacerdozio, Voce rispose: "Diventa ossessivo. Secondo me è una malattia psicologica voler per forza diventare prete quando sei donna!". Si può comprendere che, come la sua predecessora, Chiara Lubich, fondatrice del movimento dei Focolari, possa trovare abominevole l'idea del sacerdozio femminile. Ma molti teologi cattolici di alto livello e membri della gerarchia cattolica prendono molto sul serio la possibilità del sacerdozio femminile, che è stata rimossa dall'"Indice" in cui era stata inserita da Giovanni Paolo II. Sentire la leader di un'importante organizzazione cattolica usare argomenti ad hominem così estremi per mettere a tacere gli "oppositori" fa pensare. È questa una forma di espressione accettabile da parte di una persona che ricopre una grande responsabilità nella Chiesa - che ha un importante presenza in altre chiese non-cattoliche?

Guardando alla storia della Chiesa, due delle quattro donne dottoresse della Chiesa – Santa Caterina da Siena e Santa Teresa di Lisieux – hanno entrambe sentito la vocazione al sacerdozio. Soffrivano forse di una "malattia psicologica"? Anche le numerose donne sacerdoti (e perfino vescove) nella comunione anglicana sono spinte da una "malattia psicologica"? O Vescova anglicana Jo Bailey Wells, per esempio, che Papa Francesco ha invitata a collaborare con i suoi cardinali consiglieri sul ruolo della donna nella Chiesa - anche lei soffre di "una malattia psicologica". L'impressione è piuttosto che il ministero delle donne in altra chiese e stato un immenso successo. In ogni caso, il modo di esprimersi della Voce e molto esaggerato ed un insulto a persone di buona fede.

Il Movimento dei Focolari, forse il più grande e potente dei "movimenti ecclesiali" fondati nel XX secolo, che annovera tra i suoi membri sacerdoti, religiosi, vescovi e cardinali, è stato fondato da una donna e, secondo i suoi statuti, approvati da "San" Giovanni Paolo II, deve sempre avere una donna come guida. Questo fatto è spesso citato come esempio del progresso delle donne nella Chiesa, persino di una specie di femminismo. Data la virulenta antipatia per le donne prete espressa da Maria Voce durante la sua presidenza dei Focolari, è necessario un attento studio di quale sia esattamente la vera concezione del Movimento in materia di sessualità, genere e ruolo delle donne nella Chiesa. Non e un'esempio dell'indietrismo del quale paralva Papa Francesco?

Una donna tedesca che ha trascorso molti anni come segretaria di uno dei massimi dirigenti (prete) dei Focolari ed era stata spesso presente alle visite ufficiali di Chiara Lubich in Germania, una volta mi ha fatto notare che la Lubich si assicurava che non ci fossero altre donne nelle fotografie ufficiali che la ritraevano circondata da uomini – sacerdoti, vescovi e cardinali. Cosa suggerisce questo riguardo alla visione dei Focolari sul ruolo delle donne nella Chiesa? Riflette perfettamente, pero, il mito che regnava nel movimento che Chiara Lubich era la Madonna incarnata (Vicaria di Maria) nella Chiesa cattolica oggi, che perfino aveva l'autorita di commandare a vescovi e cardinali di 'fare unita' con il papa. L'ho visto con i miei occhi nei casi di Cardinal Suenens e Archbishop Helder Camara, due giganti del Concilio Vaticano II, in balia della Lubich a Loppiano o Centro Mariapoli a Rocca di Papa davanti ad un pubblico entusiasta di centinaia di focolarini.

https://www.lastampa.it/vatican-insid...

Stralcio da Chiara Lubich: culto della personalita (13 January 2021)

In un programma di fine anno.. realizzato dal movimento dei Focolari nel dicembre 2020, disponibile anche su Vimeo (https://vimeo.com/focolareorg/review/... - 43 minuti e 30 secondi), Maria Voce, successore di Chiara alla presidenza del Movimento, definisce i tre momenti salienti dei suoi dodici anni di presidenza, che ora volge al termine: 1) il funerale di Chiara (vedi il post precedente "Gesù pianse") in cui uno sconosciuto in visita {a San Paolo fuori le mura0 scoprì il Movimento, dimostrando così che Chiara vive ancora; 2) vedere Chiara viva in tutti i membri del Movimento che fanno del bene agli altri in tutto il mondo negli ultimi dodici anni; 3) la vista di Papa Francesco che firma l'enciclica Fratelli Tutti, che, secondo Voce, significava "il massimo che Chiara potesse desiderare: che un Papa promulgasse al mondo intero il suo sogno [di Chiara]". A quanto pare, i Focolari sono ora più chiaracentrici che mai.

Stralcio da: Focolarini, omofobi selvaggi per ottant'anni, compresa fondatrice Chiara Lubich, fonda un ramo LGBTQ (3 marzo 2023)

Recentemente degli ex-membri LGBTQ - esclusi per il loro orientamento sessuale - hanno cercato di stabilire relazioni con i focolarini. Uno ha ricevuto una reazione apparentemente simpatica dall'ex-presidente Maria Voce (presidente 2008- 2021). Lei gli ha consigliato di mettersi in contatto con un certo focolarino. Allo sgomento di questo giovane gay, la persona indicata da Maria Voce voleva sottoporlo alla terapia di conversione (contro la legge in molti paesi).

I documenti storici dovrebbero concentrarsi sui fatti e non sui miti, un aspetto che il movimento dei Focolari non riesce ancora a comprendere.

June 20, 2025

Lubich versus Dante - Jesus or Satan in Hell?

L'Enfer, Alberto Zardo

L'Enfer, Alberto ZardoEternal Crucifixion? But wasn't the crucifixion once and for all, while the Resurrection is eternal? According to Chiara Lubich, who, according her most fanatical followers including bishops, cardinals and theologians should be declared a Doctor of the Church, the answer is "No!"

Without doubt, he most famous description of Hell is that of Dante in his Divine Comedy (the second, perhaps that of Milton in Paradise Lost). This how, in his Inferno, Dante describes Satan:

"The Emperor of the kingdom dolorous

From his mid-breast forth issued from the ice; And better with a giant I compareThan do the giants with those arms of his; Consider now how great must be that whole, Which unto such a part conforms itself.Were he as fair once, as he now is foul, And lifted up his brow against his Maker, Well may proceed from him all tribulation."From The Divine Comedy by Dante Alighieri, translated by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Therefore, according to Dante, Satan is a frozen giant, eternally imprisoned at the lowest point of Hell. But hang on a second, in her 'visions' she called 'Paradise of '49' the self-styled visionary Chiara Lubich claims to have seen in her 'Inferno', not Satan but Christ Crucified as a giant frozen and immobilized for all eternity:

"On this side of Paradise, Hell will remain. A great J.F. (Jesus Forsaken) suspended and dead and empty and cold and hard. It will remain like matter without life (…) even J.F., who became Hell to give us Paradise, believed himself at that moment to be without purpose in life and death, deluded, a failure”. (…) (p.18)“Between heaven and hell there will be perfect unity and this through Jesus Forsaken. He made sin was made nothing. In Him nothing is so united with everything: God (…) that is, nothing becomes everything: Jesus Forsaken is God, Jesus-sin is God, Jesus-nothing is God, Jesus-Hell is God. Therefore the Father wherever he sees nothing sees J.F. : that is, he sees himself: God and therefore everywhere he sees Heaven (p.20)If we see Hell with the eye of God we do not see it. God cannot see non-being, or rather he sees it in its nothingness, in its true being of non-being. He, God, sees Jesus Forsaken down there and that is Jesus-sin or Jesus-Hell. But Jesus Forsaken is always God. Therefore God in hell sees himself, the Word... Here is the unity of the Afterlife: All God, all Heaven, all Jesus. And Hell will be for God (listen how beautiful!) the perennial cry of Jesus Forsaken, the cry of Jesus Forsaken will be eternalized. And that is, for God, Hell will be the greatest love; the love of loves, unity, God, the new song”. (p.41)

[From 107 pages of "Chiara Lubich's Comments on her pages of Paradiso 49" for the European Zone Leaders, 1974, translation by the author - numerical references to pages of 'Paradise '49']For decades, the text of the 'Paradise of '49' was kept secret by the Focolare movement's leaders because it was feared that the Church would use it as a reason to suppress the entire movement. Now it seems that all they want to do is flaunt it as publicly as possible. Although in the perspective of the Catholic Church, Lubich's 'visions' are private revelations that can make no claim to being believed by anyone, even by the focolarini themselves, within the movement they are practically sacred scripture. Since Lubich's death, her visions have been increasingly promoted by the Focolare Movement, in a flood of books, articles and videos, culminating in a recent (February 2021) statement by newly re-elected co-president Jesus Moran brazenly claining that Chiara Lubich's 'visions' are not private revelations:"It must be said that Chiara has always thought and transmitted to us... that this mystical experience is the essence of the mentality of anyone who wants to be a source of unity today in the Church and in society - and also of those who accept the charism of the Movement. Therefore, Chiara's experience is not private or particular."http://www.settimananews.it/ministeri... Lubich's musings on Hell, we find a doctrine very distant from what already exists in scripture and the Fathers of the Church.It must be remembered that Lubich was what we call in English 'a glutton for punishment', she had a taste for suffering that does not appear normal. Even Jesus prayed let this cup pass me by. But for Chiara Lubich, it is rather a case of 'It's never enough'; is it possible that her personal neuroses influenced her 'vision'?The Creed includes the phrase 'He descended into hell', but this is interpreted in the New Testament and by the Fathers of the Church as a moment of passage. But how does one reconcile this idea of a Christ who is eternally 'Sin' and 'Hell' with the words of St. Paul: 'Christ, once resurrected from the dead, can no longer die. Death no longer has dominion over him. By the death he suffered, he died to sin, and the life he lives, he lives in God.' (Rom., 6: 9-11)According to a secret document of the movement, "From this interpretation, according to Chiara, will be born - a new doctrine, a new theology, a new philosophy." Of this there is no doubt. But the fundamental question is: can this new doctrine claim to be orthodox?'

Lubich contro Dante: Satana o Gesu nell'Inferno?

L'Enfer, Alberto Zardo

L'Enfer, Alberto ZardoCrocefisione Eterna? Ma la crocefessione non era una volta per sempre mentre la Risurrezione e eterna? Secondo la teologia di Chiara Lubich, invece, che da alcuni/e dei suoi seguaci piu fanatici, compreso vescovi, cardinali e teologi, dovrebbe essere dichiarata Dottore della Chiesa, la risposta e "No!"

Il piu famoso descrizione dell'Inferno e sicuramente quello di Dante nel suo Divina Comedia (la seconda sarebbe probabilmente quello di Milton nel Paradiso Perduto): cosi descrive il Diavolo:

“Lo ’mperador del doloroso regno

da mezzo ’l petto uscia fuor de la ghiaccia;

e più con un gigante io mi convegno,

che i giganti non fan con le sue braccia:

vedi oggimai quant’esser dee quel tutto

ch’a così fatta parte si confaccia.

S’el fu sì bel com’elli è ora brutto…”

(Dante Alighieri, La Divina Commedia: Inferno Canto XXXIV 28-34)

Perciò, secondo Dante, Satana e un gigante ghiacciato, prigioniero eterno al punto piu basso dell'Inferno. Ma, aspetta un attimo: nelle sue 'visioni' conosciute come 'Paradiso di '49' la sedicente visionaria Chiara Lubich pretende di aver visto nel suo 'Inferno', non Satana ma Cristo Crocefisso, anche Lui come un gigante ghiacciato e immobilizato per tutta l'eternita:

“Al di qua del Paradiso rimarrà l’Inferno. Un grande G.A. (Gesu Abbandonato) sospeso e morto e vuoto e freddo e duro. Rimarrà come la materia senza la vita (…) anche G.A. fattosi Inferno per donare a noi il Paradiso si credette in quel momento senza scopo nella vita e nella morte, illuso, fallito”. (…) (p.18)

“Tra paradiso e inferno si sarà perfetta unità e ciò per mezzo di Gesù Abbandonato. Egli fatto peccato fu fatto nulla. In Lui il nulla è tanto unito al tutto: Dio (…) cioè il nulla diventa tutto: Gesù Abbandonato è Dio, Gesù peccato è Dio, Gesù nulla è Dio, Gesù Inferno è Dio. Dunque il Padre dovunque vede un nulla vede G:A: cioè vede sé stesso: Dio e quindi dovunque vede Paradiso (p.20)

Se noi vediamo l’Inferno con l’occhio di Dio non lo vediamo. Dio non può vedere il non essere, o meglio lo vede nella sua nullità, nel suo vero essere di non essere. Egli, Iddio, vede laggiù Gesù Abbandonato e cioè Gesù-Peccato o Gesù-Inferno. Ma Gesù Abbandonato è sempre Dio. Per cui Dio all’inferno vede sé stesso, il Verbo. Vede il Paradiso per cui è tutto Paradiso...

Ecco fatta l’unità dell’Aldilà: Tutto Dio, tutto Paradiso, tutto Gesù. E l’inferno sarà per Iddio (senti che bello!) il perenne grido di Gesù Abbandonato, sarà eternizzato il grido di Abbandonato. E cioè per Iddio l’Inferno sarà il più grande amore; l’amore degli amori, Gesù l’unità, Dio, il cantico nuovo”. (p.41)

Da 107 pagine del 1974 "Commenti di Chiara Lubich alle sue pagine del Paradiso 49" per i CapiZona europei

Per decenni, il testo del 'Paradiso di '49' e stato tenuto segreto perche si temeva che la Chiesa avrebbe bocciato il movimento a causa di queste affermazioni (e tante altre). Oggi sembra che i focolarini non vogliono fare altro che sbandierarle al mondo intero. Anche se nelle prospettive della Chiesa cattolica, le 'visioni' di Lubich sono rivelazioni private che non hanno nessuno pregio di essere creduti dai fedeli cattolici - e neanche dai focolarini stessi - dentro il movimento sono praticamente sacra scrittura.

Dopo la morte della Lubich, le sue visioni sono state promosse con sempre più forza dal Movimento dei Focolari, in un fiume di libri, articoli e video, culminati in una recente (febbraio 2021) affermazione del neo ri-eletto co-presidente Jesus Moran che le rivelazioni di Chiara Lubich non sono rivelazioni private:

"Bisogna dire che Chiara ha sempre pensato e ci ha trasmesso... che questa esperienza mistica è l'essenza della mentalità di chiunque voglia essere fonte di unità oggi nella Chiesa e nella società - e anche di chi accetta il carisma del Movimento. Perciò l'esperienza di Chiara non è privata o particolare".

http://www.settimananews.it/ministeri...

In questa messa in scena di Gesu Crocefisso eternamante nell'Inferno c'e una dottrina molto distante da quello che esiste nella scrittura e i Padri della Chiesa.

Bisogna ricordare che la Lubich era un tipo che chiamiamo in inglese 'glutton for punishment' (ghiottona di punizione), aveva un gusto per la sofferenza che non appare normale. Perfino Gesu ha pregato, 'Lascia che questo calice mi manchi.' Ma per Chiara Lubich, e piuttosto un caso di 'non ne ho mai abbastanza'; puo essere che questa nevrosi personale influenza le 'visioni'.

Il Credo include la frase 'discese agli inferi', ma questo e interpratato nel Nuovo Testamento e i Padri della Chiesa come un momento di passaggio, quando Gesu libera dall'Inferno le persone buone nate prima della Sua venuta. Ma come si riconcilia questa idea di un Cristo eternamente 'Peccato' e 'Inferno' con le parole di San Paolo: 'Cristo una volta risuiscitato dalla morte non puo piu morire. La morte non ha piu dominio su di lui. Attraverso la morte che ha subito, e morto al peccato, e la vita che vive, la vive in Dio' (Rom., 6: 9-11)?

Secondo un documento segreto del movimento, "Da questa interpretazione, nascerà, secondo Chiara, una nuova dottrina, una nuova teologia, una nuova filosofia." Di questo non c'e dubbio. Ma la domanda piu fondamentale e: questa nuova dottrina e ortodossa?

August 9, 2024

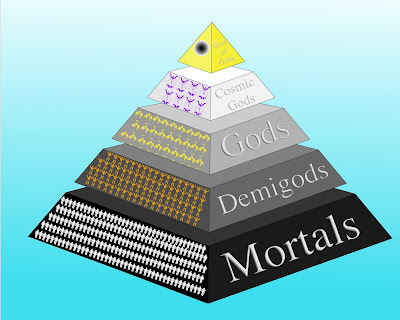

Can there be love without empathy?

'Hierarchies have a famously damaging effect on empathy, where people at the top tend to lose their empathic abilities (even if their trait empathy was high when they came into the hierarchy) while people at the bottom often need to develop hyper-empathy as a kind of counterbalance (and to keep themselves safe).' *

I recently discovered this statement on the website of Psychology Today. Having written extensively on the rigid monolithic hierarchy within Catholic movements and in particular, the Focolare Movement, it certainly confirmed my findings. Emotions are considered highly suspect within the Focolare culture - they are seen as deceptive, as 'attachments' and therefore in the 'bad zone' of Focolare's dualistic Manichean world view. They are 'human' rather than 'supernatural', bearing in mind that for Focolare foundress, Chiara Lubich, 'human' was - bizzarely - a negative term, signifying 'worldly'.

Even when I was a full-time member of Focolare (1967-76), I was often shocked by the harsh manner in which people were cancelled or dumped by the movement in a peremptory manner - especially by those in authority. People were judged starkly in terms of how useful they were to the movement - even people who had contributed generously in time, effort and materially - goods, services,money. From its origins, Focolare 'cultivated' (this word is used internally to denote recruitment) wealthy people. Even those in the UK who had provided the movement with the free use for many years of valuable properties in Central London, for example, were criticised for not giving more.

Those who left the movement were written off even more harshly. When Trudi, the former leader (capozona) of the female section of the Focolare movement in Germany, left the movement to marry in the early 1970s, her replacement, Bruna Tommasi, (one of Chiara Lubich's so-called 'first companions' - tiny but of fearsome appearance), told a German member, 'We cannot mention her name because she has betrayed God.' I experienced this personally when, after I had left the movement, but responding to their invitation, I attended the presentation of the Templeton Award for Progress in Religion to Lubich by the Duke of Edinburgh, at the Guildhall in London in 1977. When, after the ceremony, I approached another of Lubich's 'first companions', who I had known for many years, Doriana Zamboni, (sugary-sweet in appearance but tough as old boots in character), I understood for the first time what the phrase 'she looked straight through me' actually means. When I greeted her out of politeness, it was as though I was invisible, as her eyes worked the room for someone 'useful'. I left the event in a state of shock. In my career, I have worked with many important people, some world-famous in the arts and entertainment fields, but I have never encountered such bad manners as on that occasion.

The stated aim of the Focolare movement is love of others. Yet how can there by love without empathy? As a Catholic, I would propose that empathy is a God-given gift which encourages us to love others because that is what we are created to do, it is essential to being human. But showing spontaneous emotion does not compute with the kind of love Chiara Lubich and Focolare preach. Before Lubich's funeral, her longtime secretary/promoter, Giulia (Eli) Folonari, ordered that there should be no tears at the funeral (broadcast live on Italian television station RAIUNO) to prove that the members of the movement believed she was in Heaven so there was nothing to cry about. Yet Jesus wept over the death of his friend Lazarus. (See: https://popesarmada25.blogspot.com/p/...) In the nine years I spent in the Focolare movement, I never heard the word 'compassion' (= to feel with) used by a member or leader of the movement. Yet Saint Paul says, 'Rejoice with those who rejoice; weep with those who weep.' And Pope Francis frequently uses the term 'tenderness' to express the nature of Christian love, emphasising its humanity, and its connection to the emotions.

When I was at Warwick University in the 1960s, I remember a maths lecturer, an Anglican, referring to Mormonism as a 'homespun' religion. I think this is an accurate description of Focolare, many of whose interpretations of the New Testament which are fundamental to the way members are expected to live out their everyday lives are grossly over-simplified and mistaken. One example is their interpretation of Jesus' statement, when he speaks of kindness to others, that, 'in so far as you did this to one of the least of these brothers or sisters of mine, you did it to me.' (Matt. 25:40) Chiara Lubich's interpretation is that 'we should see Jesus in others' (her phrase, not the gospel's), i.e. we should project an image of Christ on to others and that should motivate us to be kind and generous. There are two problems here. The first is that this - like many other aspects of Lubich's interpretations of the gospel - is a mechanistic, Pelagian approach - going though the motions without any inspiration from God's grace (a subject Pope Francis has frequently addressed, particularly in the document Gaudete et Exsultate, 2018). This approach, Pelagianism, named after its British proponent Pelagius, was condemned by the Church as a heresy in the Sixth century because it implies that simply by doing the 'right things', going through the motions, we can save ourselves without any help from God. Secondly, 'seeing Jesus in others' eliminates completely the concept of empathy and even reduces the value and individuality of every human being in herself or himself: they are only worth loving if you 'see Jesus in them'. This is an insult to God's creation. According to Lubich, what is important is doing things for the 'right' reason, humanity and empathy play no part in this interpretation of the gospel teachings.

The hyper-empathy referred to in the final sentence of the quotation at the beginning of the article, refers to the total subservience of those at the bottom of the hierarchy, necessary 'as a counterbalance and to keep themselves safe', another feature which was very evident in the blind obedience required of the underlings, which in Focolare is called 'making unity'.

*Psychology Today,

Karla McLaren M.Ed.

July 24 2024

Ci puo essere l'amore senza empatia?

Le gerarchie hanno notoriamente un effetto dannoso sull'empatia: le persone in cima tendono a perdere le loro capacità empatiche (anche se il loro tratto di empatia era alto quando sono entrate nella gerarchia), mentre le persone in fondo hanno spesso bisogno di sviluppare un'iper-empatia come una sorta di contrappeso (e per tenersi al sicuro)." *

Ho scoperto di recente questa affermazione sul sito web di Psychology Today. Avendo scritto per molti anni sulla rigida gerarchia monolitica all'interno dei movimenti cattolici e, in particolare, del Movimento dei Focolari, ha certamente confermato le mie conclusioni. Le emozioni sono considerate molto sospette all'interno della cultura dei Focolari - sono viste come ingannevoli, come “attaccamenti” e quindi nella “zona negativa” della visione dualistica manichea del mondo dei Focolari Sono “umane” piuttosto che “soprannaturali”, tenendo presente che per la fondatrice dei Focolari, Chiara Lubich, “umano” era - sorprendentemente - un termine negativo, che significava “mondano”.

Anche quando ero membro a tempo pieno dei Focolari (1967-76), ero spesso scioccato dalla durezza con cui le persone venivano “cancellate” o scaricate dal movimento in modo perentorio - soprattutto da parte delle autorità. Le persone venivano giudicate in modo netto in termini di utilità per il movimento, anche quelle che avevano contribuito generosamente con tempo, fatica e con soldi. Fin dalle sue origini, il movimento dei Focolari ha “coltivato” (questa parola e usata internamente per indicare il reclutamento) persone ricche. Persino coloro che nel Regno Unito hanno fornito al movimento l'uso gratuito per molti anni di proprietà di valore nel centro di Londra, ad esempio, sono stati criticati dietro le quinte per non aver dato di più.

Coloro che hanno lasciato il movimento sono stati criticati ancora più duramente. Quando Trudi, l'excapozona della sezione femminile dei Focolari in Germania, lasciò il movimento per sposarsi all'inizio degli anni '70, la sua sostituta, Bruna Tommasi (una delle cosiddette “prime compagne” di Chiara Lubich - minuta ma dall'aspetto temibile), disse a un membro tedesco: “Non possiamo dire il suo nome perché ha tradito Dio”. L'ho sperimentato personalmente quando, dopo aver lasciato il movimento, rispondendo a un invito del movimento, ho partecipato alla consegna del Templeton Award for Progress in Religion alla Lubich alla Guildhall di Londra nel 1977. Dopo la cerimonia, mi avvicinai a un'altra delle “prime compagne” della Lubich, che conoscevo da molti anni, Doriana Zamboni, (dolce e zuccherosa nell'aspetto, ma dura come un vecchio stivale nel carattere). Quando l'ho salutata per educazione, mi ha ignorato come se fossi invisibile, mentre i suoi occhi si muovevano nella stanza alla ricerca di qualcuno “utile”. Ho lasciato l'evento in stato di shock. Nella mia carriera ho lavorato con molte persone importanti, anche di fama mondiale nelle arti, ma non ho mai sperimentato tanta maleducazione come in quell'occasione.

L'obiettivo dichiarato del movimento dei Focolari è l'amore per gli altri. Ma come può esserci amore senza empatia? Come cattolico, proporrei che l'empatia è un dono di Dio che ci spinge ad amare gli altri perché è ciò per cui siamo stati creati, è essenziale per essere umani. Ma mostrare emozioni spontanee non si concilia con il tipo di amore che Chiara Lubich e i Focolari predicano. Prima del funerale della Lubich, la sua segretaria/promoter di lunga data, Giulia (Eli) Folonari, ha ordinato che non ci fossero lacrime al funerale (trasmesso in diretta da RAIUNO) per dimostrare che i membri del movimento credevano che la Lubich fosse in Paradiso e che non ci fosse nulla da piangere. Eppure Gesù pianse per la morte del suo amico Lazzaro. (https://popesarmada25.blogspot.com/p/...) Nei nove anni trascorsi nel movimento dei Focolari, non ho mai sentito usare la parola “compassione” (= sentire con) da un membro o da un leader del movimento. Eppure San Paolo dice: “Rallegratevi con quelli che gioiscono, piangete con quelli che piangono”. E Papa Francesco usa spesso il termine “tenerezza” per esprimere la natura dell'amore cristiano, sottolineando la sua umanità e il suo legame con le emozioni.

Quando frequentavo l'Università di Warwick negli anni '60, ricordo che un docente di matematica, anglicano, si riferiva al mormonismo come a una religione “casalinga”. Credo che questa sia una descrizione accurata dei Focolari, molte delle cui interpretazioni del Nuovo Testamento, fondamentali per il modo in cui i membri dovrebbero vivere la loro vita quotidiana, sono grossolanamente semplificate e sbagliate. Un esempio è la loro interpretazione dell'affermazione di Gesù, quando parla di gentilezza verso gli altri, che “in quanto avete fatto questo a uno dei più piccoli di questi miei fratelli o sorelle, l'avete fatto a me” (Mt 25,40). L'interpretazione di Chiara Lubich è che “dovremmo vedere Gesù negli altri” (frase sua, non del Vangelo), cioè dovremmo proiettare un'immagine di Cristo sugli altri in modo quasi ossessiva, e questo dovrebbe motivarci a essere gentili e generosi. Qui ci sono due problemi. Il primo è che questo, come molti altri aspetti delle interpretazioni del Vangelo della Lubich, è un approccio meccanicistico, pelagiano, che consiste nel ripetere certe azioni come un cane addestrato senza alcuna ispirazione dalla grazia di Dio (un tema che Papa Francesco ha affrontato spesso, in particolare nel documento Gaudete et Exsultate, 2018). Questo approccio è stato condannato dalla Chiesa come eresia nel VI secolo perché implica che semplicemente facendo le “cose giuste” possiamo salvarci. In secondo luogo, elimina completamente il concetto di empatia e riduce persino il valore e l'individualità di ogni essere umano in se stesso: vale la pena di amarlo solo se si “vede Gesù in lui”. Questo potrebbe essere visto come un insulto alla creazione di Dio. Secondo la Lubich, l'importante è fare le cose per il motivo “giusto”, l'umanità e l'empatia non hanno alcun ruolo in questa interpretazione degli insegnamenti evangelici.

L'iper-empatia a cui si fa riferimento nella frase finale della citazione all'inizio dell'articolo, si riferisce alla totale sottomissione di coloro che si trovavano in fondo alla gerarchia, necessaria “come contrappeso e per tenersi al sicuro”, un'altra caratteristica molto evidente nell'obbedienza cieca richiesta ai subalterni, che nei Focolari viene chiamata “fare l'unità”.

*Psicologiaoggi,

Karla McLaren M.Ed.

24 luglio 2024

June 8, 2024

THE SWEETEST OF TYRANNIES - A REINTERPRETATION OF THE FOCOLARE MOVEMENT’S ‘EARLY DAYS’

Sylvia Lubich picking alpine flowers in the Dolomites

Sylvia Lubich picking alpine flowers in the Dolomites and planning the future of the Focolare movement...

This review of La casetta: Silvia Lubich and some of her companions in the 'early times' (autumn 1944 - summer 1948) by Michele Zanzucchi, (Citta Nuova, Rome, 2023) is published here in English for the first time by kind permission of Tomáš Tatranský. It reveals some startling new material on the history of the Focolare movement and the arguably abusive techniques of control introduced by foundress Chiara Lubich in the 'early days', which later became the very foundations of the Focolare system. In addition to selecting key passages from the book, Tatranský adds many valuable insights on the significance of these additions to the movement's history, never before available except to the movement's founding figures and inner circle. This review will be followed by further articles analysing the connection between these new historical insights and the Movement that was to come and as it stands today.

By Tomáš Tatranský

You will never find the truth,

unless you can accept what you did not expect.

Heraclitus

We are now living in the times of ‘creative fidelity’ (or ‘dynamic’) of those who, while being part of the Focolare Movement, try to distinguish the (allegedly) ‘pure’ divinely inspired charism from the - shall we say - imperfect elements, linked to the person of the foundress [Chiara Lubich], to her humanity influenced by the circumstances of her time: a very difficult task, given the very strong personality cult of Lubich, well rooted and encouraged in the movement for several decades.

Michele Zanzucchi’s book La Casetta, 2024, Citta Nuova, Rome,* proposes fundamentally the following: re-interpreting the founding period - the famous ‘early days’ - not just according to the official narrative of the movement, but enriching it with an alternative, complementary and, to some extent, decidedly different one.

This new critical re-reading is based in particular on the hitherto unpublished documents of Raffaella Pisetta (1914-2009)**, one of the first three companions who decided to live with Chiara Lubich [in the first Focolare]. Raffaella Pisetta and Bianca Tambosi (the third companion was Natalia Dallapiccola) suffered historically a real damnatio memoriae.

In this review of the book, I will focus on this critical aspect that reveals a somewhat disconcerting profile of Chiara Lubich (born Silvia), who has been considered by many not merely a perfectible human being, but an almost angelic creature, an immaculate and absolutely docile ‘paintbrush’ in God’s hands, the mystical presence of Mary on earth etc.

Let us begin with a few preliminary remarks. In the introductory pages, Zanzucchi states that he wants to contextualise not only the behaviour of Lubich, but also of Father Casimiro, a Capuchin and her spiritual director (Chiara Lubich and her first companions, including Raffaella Pisetta, were, in fact, all tertiaries, members of the Franciscan Third Order). He intends to contextualise behaviour that ‘today might be considered reprehensible or completely unacceptable’ (p. 9), and ways of doing things that ‘today may appear bordering on authoritarianism, even abuse’ (ibid.). According to Zanzucchi, with due contextualisation, these excesses are to be judged as ‘completely normal’ (ibid.) typical of the time, as ‘absolutely normal in the Capuchin, Franciscan and religious environment’ (ibid.) in a Trent that was as Catholic as it was provincial, in the 1940s, a good 20 years before the Second Vatican Council.

It would almost seem perfectly reasonable, were it not for the fact that, later in the book, Zanzucchi contradicts himself. For example, he recounts how Lubich and her first companions wore cilices [barbed strips used under clothing as penitential devices] ‘with iron points that stuck into the flesh’ (p. 94). In this regard Zanzucchi points out: ‘as chance would have it, Chiara happened to have the one with the sharpest points: sometimes she lent it to her companions as something particularly precious’ (pp. 94-95). When some people not closely connected to the ‘Little House’ (later renamed ‘the first Focolare’) discovered that these girls practised corporal penance in this extreme manner, they reacted with alarm and ‘it took all of Father Casimiro's authority to prevent the scandal from becoming public’ (p. 95). Furthermore, Zanzucchi admits that the tertiaries' existence at the Casetta was not what one might call serene. Observed from the outside, it could have been considered a house of ‘mad women’ (a term that Lubich herself sometimes used). Raffaella Pisetta wrote in her diary: ‘We led a weird existence: we were in an atmosphere of collective madness’ (p. 122). Finally, Zanzucchi writes that the outcome of the diocesan enquiry initiated by the archbishop of Trento, Mons. Carlo de Ferrari, about the orthodoxy of the nascent movement created around Chiara ‘was “odd”, as de Ferrari himself defined it. Don Heppergher (one of the two priests in charge of the enquiry) was unfavourable to the two accused (Chiara and Father Casimiro, accused, among other things, of having broken the secret of confession), and, on the contrary, the other priest, Don Zorer, was in favour of the Casetta’ (p. 184). Even if the archbishop's final decision was positive (although the dossier of accusations was sent to the Vatican for further investigation), it seems inaccurate to use, as Zanzucchi does, terms such as pure or absolute normality. (p. 9)

Continuing the introductory remarks, it must be reiterated that Zanzucchi - as a good focolarino - tries, to some extent, to water down a little of the ‘poison’ he perceives in some of Raffaella Pisetta's opinions. He also tries to interpret Lubich's behaviour and decisions mostly in a positive light. An example, regarding the already mentioned damnatio memoriae: ‘The silence that has so far accompanied the affair of Raffaella was determined primarily, it must be said, by Lubich's desire to avoid “a single word” being spoken against her [against Raffaella Pisetta]’ (p. 10). But are we really so sure? Isn't the hypothesis that Chiara actually forbade everyone to speak or write about Raffaella more plausible? In other words, that Chiara commanded that Raffaella Pisetta be completely erased from history, because she feared embarrassing, or even scandalous, things could emerge about Chiara herself?

Be that as it may, Zanzucchi seems to me all in all quite balanced in his interpretations, at least in the sense that he does not seem to want to substantially distort Raffaella Pisetta's point of view. I would say that one of the book's main theses is Zanzucchi's conviction that ‘it must be accepted that the two human microuniverses of Lubich and Pisetta simply did not meet’ (ibid.). And again: ‘The inspiration for Chiara had to come from mysticism, for Raffaella from humanity’ (p. 131).

Let us now look again at some salient points of the ‘counter-narrative’ of Raffaelle Pisetta who, Zanzucchi freely admits, was a smart, generous, balanced girl, endowed with common sense as well as a marked sensitivity both to social problems and to the arts, especially poetry. Incidentally: it was Raffaella Pisetta who in 1944 managed to find stable accommodation - the ‘Casetta’, a flat at No.2 Piazza Cappuccini - for her fellow tertiaries. It was in her name. But not only that: Raffaella Pisetta financially supported the very first group with board and lodging for at least a year, since she was the only one to receive a regular salary.

Raffaella was not a ‘disciple’ of Lubich, but a tertiary, attracted by the Franciscan ideal, who began to live with Chiara, Natalia Dallapiccola and Bianca Tambosi, as she said, ‘almost for fun, as a logical consequence of the difficult times, of not knowing where to sleep, eat...’ (p. 179). It was spontaneous for all of them to share everything, including money. So ‘Chiara also wanted the income, and not only the outgoings, to be managed by herself, even though she was not yet fully considered by Father Casimiro as the community leader [i.e., to be exact, the Third Order's “novice mistress”]. There was still, in fact, a certain equality between Raffaella and Chiara' (p. 107). ‘Father Casimiro,’ Zanzucchi continues, ‘often arrived laden with sacks of flour or rice, packages of jam, oil, tinned fish: they were for the poor. On the list of the poor was the Lubich family (...). Those supplies sometimes ended up with Luigi [Chiara Lubich's father] and his family. Here and there, those supplies were also used for the everyday running of the Little House, even though Raffaella and Bianca, the oldest and most experienced, did not approve. Nor did they when Chiara gave everything away to the poor, as if it all belonged to her and it was her right to do so. In April 1945, Father Casimiro gave Raffaella an earful because she continued to use the money she earned for household needs, and still felt like the ‘mistress of the house’. He therefore urged Pisetta to hand over her entire salary to Chiara. Which Raffaella did, somewhat unwillingly to tell the truth. Moreover, according to Pisetta, Lubich wanted the envelope to be delivered into her hands, not placed in the money drawer as her companion did' (ibid.).

‘A delicate chapter’, Zanzucchi notes, ‘was also that of the unequal treatment Chiara reserved for her family, favoured, privileged and even revered, whose members had permanent access to the Casetta, compared to the other girls who did not have the same privileges: they had to forget family ties “so as not to be attached to human affections” ’ (p. 126). And again: ‘As for housework, again according to Raffaella Pisetta, Chiara was not interested in it, nor did she want to deal with it. “I can't waste time on these things,” she said, “because my mission is of an entirely different nature”. As much as she tried to put up with it herself, Raffaella asked Father Casimiro one day: “Why, Father, do you use double standards, one for Chiara and the other for me? Why do you find it natural that Chiara, although she’s at home all day, does no housework, and that I, although going to the office, also do household chores?” The answer was simple: “Daughter, Chiara is not used to it, poor thing. All she is capable of doing is talking, not doing chores”. Thus Raffaella often pointed out the inconsistency of the guest who, in a house that did not belong to her, demanded to be served and obeyed. But it was not only she who demanded obedience: according to Raffaella, the Lubich family also had “the same arrogance”, having “address, accommodation and source of supplies” at No.2 Piazza Cappuccini’ (pp. 146-147).

Another aspect that is highlighted in the book is Lubich's inability to handle dissent calmly, even in the smallest matter. Faced with criticism, Chiara never engaged in a sincere and open dialogue; she seemed unable to understand that even a moment of discord could become an opportunity to grow and improve together, to perhaps correct an obsolete or ineffective way of doing things. No, Chiara demanded from her disciples adherence, indeed total and blind obedience, without ‘ifs’, without ‘buts’: she was the sole bearer of the truth - or rather, she deluded herself into thinking she was. Some of her companions, then (especially Natalia Dallapiccola), were astonished whenever anyone dared to oppose their teacher par excellence. When faced with criticism Chiara would withdraw, become sad, cry, or even sink into ‘nights’ (Zanzucchi calls them ‘black holes’: cf. pp. 135-139), or (what were believed to be) spiritual trials, often linked to situations of psychosomatic exhaustion, sometimes lasting several months.

In short, Chiara - according to Zanzucchi - adopted ‘a more or less Manichean vision of life’ (p. 124). She felt invested with ‘a great authority in her mission, or even, according to the expression later used by Archbishop de Ferrari himself, to exercise among the tertiaries “the sweetest of tyrannies” (...). Raffaella went on to note: ‘Absolute authority, which Chiara termed “of love”, but which was in fact despotism, could only exist on one condition: the utter loss of will and judgement’’ (ibid.). ‘Love itself,‘ adds Raffaella Pisetta, ‘was perceived, in Chiara's mystical vision, as something divine, detached from, indeed opposed to all that is human, to reason: reason was contrary to love, judgement was demonic’ (p. 123).

The relationship between Chiara and Father Casimiro was sensitive and complex. I will highlight just one aspect of it here. One day Raffaella Pisetta asked Father Casimiro ‘why Chiara Lubich possessed that “prerogative” whereby she believed she was always right. He had no direct answer. She gave him an example: one day Chiara wept for a long time (according to Raffaella that was her trick to wear down other people’s resistance, especially with Father Casimiro), because he would not accept her [Chiara's] thesis that a saint, would, by his very nature, automatically become a great poet, an excellent painter, an incomparable sculptor, not to mention the saint's ability to solve any problem, whether philosophical or theological’ (p. 146).

On the subject of Lubich's yearning to assume every beautiful and/or divine power, indeed to identify herself, by virtue of a pseudo-mystical fusion with these realities (thta is, not through unity therefore, which at least in Christian theology safeguards distinction and otherness) we quote another very significant passage from the book, which speaks of Lubich's ‘tendency to identify herself with the object of her contemplation, using the first person: “I am the Father”; “Today I am the Son”; “I find myself being the Mother” and so on. Raffaella Pisetta again points out: “God had given her a great mission (’so great that no one will understand me‘) and by identifying herself in the Son, in the ‘light’, in the ‘truth’, in the ‘mouth of the truth’; she referred the words of Jesus’ Testament to herself, instead of to God. In fact, unity was not ‘being one’ in God, but one ‘in her’, who alone had the truth, who alone represented the divine will, who alone possessed not ‘an ideal’ but ‘the Ideal’ that would save the world” ‘ (p. 127).

Not submitting to Chiara (or doing so, but not 100%) therefore meant ‘breaking unity’: ‘The idea of “breaking unity” played a major role at the Casetta. But what did it mean? According to Raffaella Pisetta, breaking unity meant “not showing the required enthusiasm by giving little cries of delight [at the words of Chiara]; not makiing the grotesque effort to be as infantile as possible [in fact, Chiara called her companions pope: which means ‘little girls’ in the Trentino dialect]; being serious and a bit distant when Chiara recounted her illuminations; not being anxious to run after Chiara and staying as close to her as possible; behaving less ridiculously and more appropriately in public rather than following the requirement of going into a huddle and competing with each other to crowd around her, listening to her endless outpourings” ‘ (p. 126).

Moreover, even expressing a truth that Chiara found uncomfortable counted as breaking unity. According to Raffaella, Lubich's favourite saying was, ‘’any lie, as long as it was covered by a veil of intended charity, was OK’ (p. 181).

Anxiety, therefore, was encouraged - that is, scrupulous striving for holiness or perfection. The result of this tension was certainly considerable stress and a chaotic existence marked by hyperactivity. ‘Chiara was known for her constant twists and turns, as Pisetta observes: “She made plans, changed them, re-made them; drew up lists of people divided according to the ‘results’ they produced. She called meetings, retreats, gatherings, and at the last moment changed her mind on the time, on the convenience of inviting these or those, on the place of the meeting... A continuous doing and undoing, with great agitation of orders and counter-orders‘’ ‘ (p. 125).

It should be noted that the nights were not exactly quiet either: ‘there was a further nocturnal practice: we would wake up at midnight to scourge our backs with special chains, during the recitation of a Salve Regina. Chiara would always do it first, then wake Natalia, who in turn would beat herself with those chains and then wake Doriana, and so on, until morning. It was not easy for the girls, after that practice, to go back to bed with a flayed back' (p. 95). Other forms of penance were ‘sleeping on hard boards, on the floor, without a mattress’ (ibid.); chewing bitter wormwood leaves, keeping absolutely silent for one or more days (cf. ibid.).

It is hardly surprising, in this extreme context, that any break in unity was fundamentally interpreted as the work of the devil (cf. p. 165). But there is more: Chiara went so far as to affirm that those who did not correspond to the vocation to unity - to unity seen as a fusion that destroyed the personalities of those who allowed themselves to be fused - would burn eternally in hell. This is clearly stated in a letter that Lubich addressed to Raffaella in 1947, after the latter left the Casetta (which, let us remember was, by law, her own home) simply because she could no longer cope after more than two years of cohabitation with Chiara: ‘’It seems to me,' Chiara wrote to her, ’that you are a victim of disunity. As long as everything was going smoothly, you were happy with all the others; when the pains of unity began, which must always be there because we have to die to our personality in order to fuse, then you moved away. (...) The Lord allowed this time of trial to see who was in unity for the love of God or for the love of self. However, you are free to do what you want, because to be saved it is not necessary to be in unity, unless this was a vocation for you to which you had to correspond’ (pp. 164-165).

Here, Chiara did not expressly state whether Raffaella would end up in hell, but she did a few months earlier, as Zanzucchi writes: ‘Raffaella forced herself to ask Father Casimiro for permission to leave (...). She would rather join an enclosed convent than remain “in this kind of life so lacking in dignity”. Father Casimiro tried to dissuade her, but it shook him. The Capuchin spent the rest of the morning in conversation with Lubich, and then they both told Raffaella that her vocation was not the convent but unity. Indeed, not only unity, but life in common with Chiara. “On pain of damnation,” Raffaella reported (p. 147).

To summarise and conclude, I leave it again to Zanzucchi: ‘In the “doctrine” that was being developed, it was fundamental to renounce expressing oneself in a “human” way, in order to behave “supernaturally”, a distinction that today's theologians would have difficulty endorsing. It would have been simpler if one had used the terms “human” and “divine” -, given that Christ himself made humanity his own. For Chiara “human” was often synonymous with “subhuman”, and “supernatural” with “superhuman” ‘ (p. 123).

I would ask Zanzucchi: are we just talking about today’s theologians’? I have my doubts: in fact, if we take into consideration the famous principle that goes back to the great figures of medieval scholasticism, according to which gratia supponit naturam, non destruit, sed perficit eam (Grace builds on nature; does not destroy it, but perfects it), we immediately see how much Lubich's distorted mysticism diverges from sound Christian tradition.

Some focolarini, as Michele Zanzucchi tries to do, would like to purify the Focolare message - what they call the ‘charism of unity’ - from what links it to the historical epoch and the times of its foundation. I wonder if the task is not rather to purify this message from what was linked to the person of Chiara Lubich herself.

------

* The little house - Silvia (Chiara) Lubich and some of her first companions (autumn 1944 - summer 1948). Michele Zanzucchi - Città Nuova Editrice 2023: ‘An updated history of the early years of the Focolare Movement. The story of Silvia ‘Chiara’ Lubich and her first companions in Trento, northern Italy, in the 1940s describes a charism at the service of unity that bore so much fruit for the Church and for the whole of humanity in the following decades. Almost eighty years later, the consultation of documents and a series of interviews make it possible to trace the history of those early days with new details and new perspectives, thus enriching the story of the foundation of the Focolare Movement with hitherto unknown information’. Zanzucchi is a consecrated focolarino, scholar and writer, former editor of the Focolare magazine Città Nuova.

** Raffaella Pisetta (24 September 1914-18 April 2009) was a journalist, writer and poet, committed to social work and politics. In the 1950s she worked in Milan as editor of the magazine Gioia published by Corriere della Sera. She was a municipal councillor in Trento during the 1960-1964 legislature. She was Provincial president of the CIF (Italian Women's Centre). In the 1960s and 1970s, she collaborated in the national association of SOS Children's Villages in Italy and was a member of the promotion committee and the first boards of the SOS village in Trento. She contributed to various newspapers and magazines with literary and informative articles. She was a successful poet.

November 27, 2023

Shakespeare (in HAMLET) explains the Focolare movement's 'Old Man'

When I met the Focolare Movement in 1967, I was 17 years old and had very clear ambitions: to be a writer and film maker. I had already written two 70,000-word children's novels and made films using standard 8 equipment, which at the time was difficult and very expensive, unlike today with all the digital possibilities readily available. I had won various writing competitions, including, at age 16, the first prize of a two week trip to Rome in an international essay competition. At first, in my enthusiasm to become a fulltime member and continue to follow my creative ambitions within the Focolare movement, I did not realise that Focolare members are only lay persons in appearance. In fact they are required to renounce all personal ambitions and talents as 'attachments' and instead become available as vessels to be used by the movement, in particular to further the ambitions of the foundress Chiara Lubich - most of which I now see as verging on the megalomaniac. Within a few months, I was swept away by the love-bombing I was subjected to and had not only shelved my artistic ambitions but destroyed the novels that, with remarkable discipline for a teenager, I had spent months slaving over , and which my mother had spent long hours after work typing up to be sent to publishers.

While I was a member of Focolare, without fully understanding it, I realised that the movement's key to intelligence, culture and creativity was censorship. I remember one particularly striking example was when I was at Loppiano. One of the first focolarini, Giorgio Marchetti, but rebaptised by Chiara Lubich as 'Fede', then head of all the male focolarini in the world, was visiting and in the course of a casual conversation with a small group of us solemnly proclaimed, 'Shakespeare was a great expert on the Old Man.' The term 'Old Man', borrowed from St Paul, was frequently used in Focolare to describe mankind's - or an individual's - negative aspects. The reference to Shakespeare was, of course disparaging, suggesting that his work was of little value because all he knew about was the bad aspect of humanity. Probably 'Fede' made the comment as a dig at me, since I was the only English person present. I wasn't really shocked at the time, because it was common for leaders in the movement to dismiss virtually everything in the 'World'. 'World' and even 'human' had a negative sense in focolare-speak.

A few days ago I came across a passage, referring to the 1964 Soviet film version of Shakespeare's Hamlet, singling out the 'flute scene' as one of the great director Grigori Kozintsev's finest achievements. Watching the scene, I realised that 'Fede' was partly right - at least in the sense that Shakespeare 'was a great expert on the "Old Man"' of the Focolare Movement and the focolarini. You can find the scene in glorious 4K black and white widescreen on Youtube here (I would recommend to all cinephiles that they should watch the whole film) : (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OzN1i...

This is the text of the 'flute scene':

Hamlet: Act 3, Scene 2:

Innokenty Smoktunovsky as Hamlet and Anastasiya Vertinskaya as Ophelia in Grigori Kozintsev's 1964 film of Shakespeare's HamletFor Russian audiences in 1964, Kozintsev's filkm of Shakespeare's Hamlet, probably the all-time great filmed version of a Shakespeare play, must have made a colossal impact, packed as it is with subtext. Fortunately, the powers that be in the USSR - as is usually the case for censors - were too dumb to pick up on subtle subtexts, but audiences weren't. From the start of the film, Elsinore is shown as a prison, its great portcullis falling behind Hamlet as he enters it shortly after the opening credits. Audiences knew, for example, the torments endured by the composer of the monumental score for the film, Dimitri Shostakovitch, and the translator of the text, Boris Pasternak, under the Soviet authorities. How relevant this scene was to them: the Soviet powers had tried to 'play' them just as Hamlet believes he is 'played' in this scene. In one sense or another, the whole population was being 'played'. It is worth analysing carefully Hamlet's last speech: the line 'you would/pluck/out the heart of my mystery' is devastating and so true for those who have experienced it - who knows the echoes it must have inspired in the hearts of Shostakovitch and Pasternak.

But how relevant this scene is also for all those who were internal members of the Focolare movement. Doesn't it sound familiar? Weren't we 'played' too? Forced to do jobs that we did not choose and that served the needs of the movement? Forced to marry against our will someone with whom we were not in love? Forced even to 'convert' from our natural, God-given sexuality? They tried to do all three to me: seeing my writing abilities, they made me editor of the Focolare magazine New City in the UK; they wanted to 'convert' me from my natural sexuality as a gay man and arrange a heterosexual marriage with who knows who. Thank God, I managed to escape, and eventually build a happy life as a gay man, succeed as a film director and writer by profession (kalamos.org). So, after all, 'Fede' was right - at least in this case of 'playing people'. Shakespeare was familiar with at least one form of 'Old Man', one of the many forms practised by the Focolare movement: the attempt to 'play' people as if they were an instrument to be used for the movement's megalomaniac powers. Fortunately, they did not always succeed.

November 24, 2023

Shakespeare (in AMLETO) spiega 'l'Uomo Vecchio' dei Focolarini

Fede (Giorgio Marchetti) e Chiara Lubich: esperti di Tutto

Fede (Giorgio Marchetti) e Chiara Lubich: esperti di Tutto

Quando ho conosciuto il Movimento dei Focolari, nel 1967, avevo 17 anni e ambizioni molto chiare: diventare scrittore e regista di film. Avevo già scritto due romanzi per ragazzi di 70.000 parole ciascuno e realizzato film con l'attrezzatura standard 8, che all'epoca era difficile usare e molto costosa, a differenza di oggi con tuitte le possibilita audiovisivi digitali. Avevo vinto diversi concorsi di scrittura, tra cui, a 16 anni, il primo premio di un viaggio di due settimane a Roma in un concorso internazionale di saggistica.

All'inizio, nel mio entusiasmo di diventare focolarino e continuare a seguire le mie ambizioni creative all'interno del movimento dei Focolari, non mi ero reso conto (anche perche era nascosto) che i membri interni dei Focolari sono laici solo in apparenza. In realtà, devono rinunciare a tutte le ambizioni e ai talenti personali come "attaccamenti" e diventare invece disponibili come vasi da utilizzare per il movimento, in particolare per promuovere le ambizioni della fondatrice Chiara Lubich - la maggior parte delle quali, a mio avviso, rasentano la megalomania. Nel giro di pochi mesi, sono stato travolto dal "love-bombing" a cui sono stata sottoposta e non solo ho accantonato le mie ambizioni aristiche, ma ho distrutto i romanzi su cui avevo passato mesi a sgobbare, con una disciplina notevole per un'adolescente, e che mia madre aveva trascorso lunghe ore dopo il lavoro a battere a macchina per inviarli alle case editrici.

Durante i nove anni che ero focolarino, senza comprenderlo appieno, mi resi conto che la meta del movimento verso l'intelligenza, la cultura e la creatività era la censura (per l'intelligenza, piuttosto l'eliminazione totale). Ricordo un esempio particolarmente eclatante quando seguivo il corso biennale di formazione a Loppiano, in Toscana (ora lo ricordo come il mio "inferno toscano"). Era in visita uno dei primi focolarini, Giorgio Marchetti, ma ribattezzato da Chiara Lubich "Fede", allora capo di tutti i focolarini maschi del mondo. Nel corso di una conversazione casuale con un piccolo gruppo di noi, proclamò solennemente: "Shakespeare era un grande esperto del 'Uomo Vecchio' ". Il termine "Uomo Vecchio", mutuato da San Paolo, era una frase molto usata nei Focolari per descrivere gli aspetti peggiori dell'umanità o di un individuo. Il riferimento a Shakespeare era ovviamente denigratorio, suggerendo che la sua opera era di scarso valore perché conosceva solo il lato peggiore dell'umanità. Puo darsi che 'Fede' ha fatto il commento a posta come una frecciata contro di me, dato che ero l'unico inglese presente. All'epoca non mi scandalizzai più di tanto, perché era consuetudine per i pezzi grossi del movimento rifiutare praticamente tutto ciò che si trovava nel "mondo", cioè al di fuori del movimento. Il termine "mondo" e persino "umano" avevano un senso negativo nel linguaggio 'focolarese'.

Qualche giorno fa mi sono imbattuto in un brano, riferito alla versione cinematografica del 1964 dell'Amleto di Shakespeare, che individuava nella "scena del flauto" uno dei maggiori successi del grande regista Grigori Kozintsev. Il film è certamente nella mia personale 'top five' dei film di tutti i tempi. Rivedendo la scena, mi sono reso conto che "Fede" aveva in parte ragione, almeno nel senso che Shakespeare "era un grande esperto del "Uomo Vecchio"" del Movimento dei Focolari e dei focolarini. Potete trovare la scena in glorioso 4K widescreen bianco e nero su Youtube qui: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OzN1i...

Ecco il testo della "scena del flauto":

Innokenty Smoktunovsky (Amleto) and Anastasiya Vertinskaya (Ofelia) nel film Amleto (1964) di Grigori Kozintsev

Innokenty Smoktunovsky (Amleto) and Anastasiya Vertinskaya (Ofelia) nel film Amleto (1964) di Grigori KozintsevPer il pubblico russo del 1964, il film di Kozintsev dell'Amleto di Shakespeare, probabilmente la più grande versione cinematografica di tutti i tempi su un'opera di Shakespeare, deve aver avuto un impatto colossale, ricco di sottintesi [subtext]. Fortunatamente, le autorità dell'URSS - come di solito accade per i censori - erano troppo stupide per cogliere questi sottintesi, ma il pubblico sovietico non lo era. Fin dall'inizio del film, Elsinore viene mostrata come una prigione, la cui grande saracinesca cade alle spalle di Amleto quando vi entra poco dopo i titoli di testa. Il pubblico conosceva, ad esempio, i tormenti subiti dal compositore della monumentale colonna sonora del film, Dimitri Shostakovitch, e dal traduttore del testo, Boris Pasternak, sotto le autorità sovietiche. Quanto era importante questa scena per loro: le potenze sovietiche avevano tentato di "suonarli" proprio come Amleto crede di essere 'suonato' in questa scena. In un senso o un altro, tutta la popolazione veniva 'suonata'.

Ma quanto è importante questa scena anche per tutti coloro che sono stati membri interni del movimento dei Focolari. Non lo riconosciamo? Non siamo stati anche noi suonati? Costretti a fare lavori che non avevamo scelto e che servivano alle esigenze del movimento? Costretti a sposarsi contro la nostra volontà con quaklcuno/a col quale non eravmo inamorati? Costretti persino a "convertirci" dalla nostra sessualità naturale, data da Dio? A me hanno cercato di fare tutti e tre: vedendo le mie capacita come scrittore, mi hanno fatto direttore della rivista focolarina New City nel Regno Unito; volevano 'convertirmi' dalla mia sessualita naturale di uomo gay e organizzare un matrimonio combinato eterosessuale con chissa chi. Grazie a Dio, sono riuscito a scappare, e eventualmente costruire una vita felice da uomo gay, riuscire come regista di film e scrittore di professione (kalamos.org) Quindi, dopo tutto, "Fede" aveva ragione - almeno in questo caso di 'suonare le persone'. Shakespeare conosceva bene almeno una forma di "Uomo Vecchio", una delle tante forme praticate dal movimento dei Focolari: il tentativo di "suonare" le persone come se fossero uno strumento da usare per i poteri megalomani del movimento. Per fortuna, non sempre riuscivano.

popesarmada25.blogspot.com

- Gordon Urquhart's profile

- 8 followers