Gordon Urquhart's Blog: popesarmada25.blogspot.com, page 9

September 30, 2020

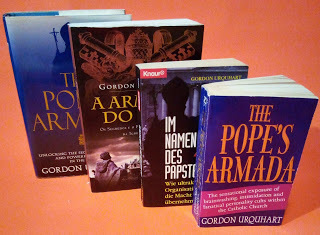

The Pope's Armada: 25 years on

'A searing attack upon three of the most energetic new movements in the

Catholic Church,' declared a Time magazine article on cults. 'A terrifying portrait of several ultra-traditionalist movements in the Catholic Church,’ said the Association for the Rights of Catholics in the Church. In the New Statesman, academic and prominent writer on religion, Karen Armstrong called it, ‘a remarkably balanced and informative account...his book is disturbing.’ Sandro Magister, leading Vaticanologist and religious affairs correspondent for the Italian weekly news magazine L’Espresso, commented that, ‘The Focolare Movement has succeeded in establishing an immaculate, glowing image of itself as an everlasting rainbow. Until today. Because today, even for them, the enchantment is about to shatter. A book by one of their former leaders, the Englishman Gordon Urquhart, published in Italy by Ponte alle Grazie paints for the first time a much less glittering portrait of the Movement which he claims to be much more accurate.’

These were some of the initial reactions reactions to The Pope's Armada when it was first published 25 years ago. Commissioned by Bantam Press in the UK, later appearing in translation in Germany (Droemer, 1996) , Italy (Ponte alle Grazie, 1997), Belgium and the Netherlands (Standaard, 1997), France (revised edition, Golias, 2001), Brazil (revised edition, Record, 2002) as well as a revised English language version in the USA (Prometheus Books, 2000), it remains the only internationally researched investigative reportage into, and analysis of, the phenomenon of vast and powerful 'new movements' in the Catholic Church and is still unique in this respect.

It focused on the three largest of these organisations, and the ones which received unqualified support from Pope - now Saint - John Paul II: the Focolare Movement, Communion and Liberation and the Neocatecumenal Way. Given the highly secretive nature of these movements, and the lack of any previous critical appraisal, the approach of the book was that of qualitative research, using primary sources such as numerous interviews in several countries, attending events held by the groups themselves in Europe and the USA, gaining access to unpublished manuscripts and secret documents never before released to the public and in some cases not even to the authorities of the Catholic Church. My own 9-year membership of the Focolare Movement (1967-76) provided a lens through which I was able to analyse and explore how these secret organisations operate: what to look for and how to look for it.

Searching out and recording common characteristics of these groups, what emerged very clearly was their similarity to cults: the use of such practices as the personality cult of the leader; a rigid but secret hierarchy; a highly efficient internal communications system; secret teachings revealed in stages; vast recruitment operations using techniques such as love- bombing; arranged marriages; operating through front organisations, often with an apparently secular identity; indoctrination of members; boundless ambition for power and influence in the church but also in politics and the media; strong pressure to exact money from members and others to swell the movement's enormous wealth; in some cases a promotion of 'ego destruction' causing depression and mental breakdown on an alarming scale.

To accuse Catholic organisations, especially those vigorously championed by the Pope, as resembling cults was strong stuff in 1995 and met with some incredulity at first. Amidst the international controversy in Catholic circles, the Archbishop of Vienna, Cardinal Christoph Schoenborn, a member of John Paul II's inner circle, decreed that it was meaningless to use the term 'cults' to descibe official Cathoilc organisations. When asked for an interview for a newspaper article, a Cardinal of the Vatican's Pontifical Council for the Laity told me that I was wrong to have written a book on the subject: such matters must be dealt with behind closed doors - an argument with a chilling ring in the wake of Catholicisim's world-wide pedophilia scandals. Interestingly, however, not a single fact presented in the book was ever challenged by the movements or other defenders. What the criticisms of The Pope's Armada - and they were ferocious - had in common, were that they were largely of the ad hominem variety, personal attacks on my character as a witness - that the book was written as revenge against Focolare, for example.

In 1995, The Pope's Armada presented a thesis which was so little-known and unexplored that, even to experts on Catholic affairs, it seemed too bizarre to be believed. A well-known English Catholic novelist actually compared it in his review to fake biographies written by anti-Catholics and militant Protestants in the nineteenth century purporting to describe the lurid horrors going on in Catholic convents and monasteries. In the past twenty-five years, however, there have been enormous changes. The movements have become larger and more powerful than ever, but The Pope's Armada's challenging assertions have become widely diffused and accepted by academics, human rights bodies and anti-cult organisations. Social media has provided opportunites for ex-members - and even current members - to share their first-hand experiences. Networks of former members of Catholic movements, clerics and academics have developed, particularly in Europe. Although the book was aimed at the general reader, in 1995 it was something of a niche subject. Mainly thanks to Dan Brown's The Da Vinci Code (2003), the topic of mysterious Catholic movements has now become mainstream - in fact The Pope's Armada was included in the 'partial bibliography' used in researching that novel.

Most interesting of all - and an important incentive behind this blog - are recent changes in how the Vatican sees the movements. Clearly, the Pope of the book's title is John Paul II, though it could equally refer to Pope Benedict XVI, the former Cardinal Ratzinger, John Paul's most faithful henchman who deemed the new movements 'the one good thing to emerge in the Church since the Second Vatican Council.' Pope Francis, on the other hand, judging by recent actions, documents and pointed addresses to members of these movements, has a clear idea of some of their dangers, as will be thoroughly demonstrated in forthcoming posts.

Have my views changed? Rather they have been confirmed by the many examples I have since had access to - mainly from numerous readers who have contacted me over the years. The only change, perhaps, is that in the case of Focolare, I find it a great deal weirder than I did when I wrote The Pope's Armada in 1995.

In The Pope's Armada 25, my aim is to examine these changes through posts, podcasts and interviews. Please contact me if you feel you have something of interest to share on these issues.

May 2, 2012

My Mother's Passing

As with everything in her life, she had a unique approach to the Focolare Movement when I became involved with it in the 60s and 70s. She was extremely generous to the Movement, lending it substantial sums of money, interest free for many,many years, and financing the education of the brother of an African focolarino - although she was far from wealthy herself. At the same time, she subjected the Focolare Movement to the unflinchingly honest appraisal which characterised her approach to life. I will be away for a few days, but my next post will be on my mother's views on the Focolare Movement and its teachings.

February 29, 2012

Papal favour is no guarantee of authenticity

The Legionaries of Christ and Regnum Christi were highly favoured by John Paul II, so highly favoured in fact that numerous accusations of child abuse against the founder of these organisations, the late Mexican priest Father Marcial Maciel Degollado, were hushed up by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith - then headed by Cardinal Ratzinger - until after John Paul's death. This story - and the compelling evidence provided to the Congregation and Ratzinger - is recounted in detail in the book Vows of Silence by Jason Berry and Garald Renner (Free Press 2010). It makes sobering reading. Maciel not only systematically abused seminarians of his order over many decades, but he absolved them from the acts (such as fellatio) he forced them to commit with him; absolution under these circumstances is an offence which, under canon law incurs automatic excommunication for the priest. He also used these young followers of his to procure the prescription medication he needed to feed his substance addictions. The order capitalised on the Vatican's silence to issue strenuous denials of the charges against their beloved Father.

Ratzinger pursued the matter as soon as he became Pope. But this is not greatly to his credit as it only goes to show that he believed the accusations were true but failed to act on them earlier under some misguided belief that disciplining a favourite of the late Pontiff would somehow be disrespectful to the papal office or the person of John Paul. Surely this reveals what a cockeyed system of values prevails in the Vatican: a far cry from the teachings of Jesus who reserved his strongest condemnation for those who corrupt the young and innocent, and had no time for puffed-up religious authorities.

Once the facts about Maciel's history of abuse began to come out, it seemed that what had previously emerged was only the tip of the iceberg. Maciel's voracious sexual appetite not only included young boys but also several women with whom he fathered three children (at least to date - I have also heard the estimate set at six!). Cases of Maciel's abuse of seminarians have been estimated at between twenty and a hundred. Although the CDF did investigate Maciel after John Paul's death, its final decision, with the blessing of Pope Benedict, was to close the case without any canonical action due to Maciel's advanced age and frail health. He was required to renounce every public activity, including his position as the Superior of the Order, and pursue a life of prayer and penance. Father Marcial Maciel died in 2008.

In 2009 Pope Benedict authorised an Apostolic Visitation to investigate all branches of Maciel's organisation - both the Legionaries of Christ and the male and female branches of Regnum Christi. Since then, members have left in droves. Between 200 and 400 of almost a thousand consecrated women of Regnum Christi have left the movement since the facts about Father Maciel emerged. Then, on 17th February 2012, the leader of the women of Regnum Christi, Malen Oriel, announced that she was leaving the organisation with thirty other women. The Oriols are a wealthy and influential Spanish family who played an important role in the development of Legionaries of Christ and Regnum Christi. Four of Malen's brothers who were priest members of the Legionaries of Christ have already left the order. On 27th Febraury, it was announced that Oriol has started a new organisation called Totus Tuus (the motto of John Paul II) based in Chile with the thirty women who left with her. It has been approved by the Vatican and has the blessing of Pope Benedict. Some observers believe that this could be the start olf the unravelling of the entire organisation.

Orders have survived the disgrace of their founders before. One of the founders of Capuchin branch of the Franciscans became a Calvinist and married. It remains to be seen whether Maciel's can do the same. One beneficial effect of the Maciel affair is the Vatican's questioning of the excessive power of charismatic founders of new movements and congregations. A meeting was held on 13th June last year between the heads of the Vatican congregations and Benedict XVI at which the Secretary of State Cardinal Tarcisio Bertone read a paper on this question, pointing out that these leaders often demanded greater loyalty to themselves than to the Church.. How seriously this will be taken remains to be seen; Bertone was a great admirer of Chiara Lubich and presided at her funeral mass. One thing is for sure though, papal approval can no longer be regarded as a guarantee of anything!

February 16, 2012

Tragic Death of Marisa Bau

Official statements on the Focolare Movement website accept this possibility. Marisa Bau's family, however reject this explanation on the grounds that suicide would conflict with her Christian beliefs. Prior to the discovery of the body, a high profile appeal for information on the missing woman, spear-headed by the Focolare's official website, seemed to suggest that the movement's leadership was convinced that, whether Bau had left voluntarily or not, she would be found alive. At first the appeals insisted that she had been in good spirits at the time of her disappearance, but gradually there were hints that maybe she had been troubled in some way. She had just returned from a journey to Brazil and was jet-lagged and complaining of a severe headache. While hardly an explanation for suicide in themselves, as the Focolare's official website seem to suggest, short-term disorientation could have aggravated an existing state of mind. If indeed this was suicide - and, if so, circumstances would suggest a firm intention, rather than a cry for help - one can only guess at the depth of despair and isolation she felt. Yet there seems to be no indication that those closest to her were aware of what would have been a profoundly disturbed mental state.

Those unfamilair with the inner workings of the Focolare Movement, might conclude that this would rule out suicide. The final results of the autopsy will not be available for a few weeks and so, for the moment, any explanations must be speculative. Yet from my own experience of leaving the movement, after a number of years as a celibate focolarino with vows, I would suggest that suicide is certainly a possibility despite the lack of obvious motivation.

Like other similar 'New Movements' in the Catholic Church, Focolare encourages an 'angelistic' approach. Whatever extremes of personal anguish they may be feeling, members are encouraged to maintain an impression of smiling serenity, the hallmark of the focolarini, which strikes some observers as attractive and others as zombie-like. Thus even their immediate colleagues might remain unaware of personal problems - which might only be revealed to higher authorities such as the 'capizona', the regional leaders.

Although my exit from Focolare was carried out in agreement with the movements' superiors and through the official channels, right up to the day I left I was still expected to lead meetings. I remember translating recordings of Chiara Lubich's talks and feeling my mind almost literally split in two. The only way I could describe this schizoid state was that it was as though there were a sheet of glass dividing my brain - on one side was my Focolare self, on the other was the self waiting with bated breath to escape. The mental strain was immense.

I know how alone it is possible to feel when you reach a point where to stay in the movement would destroy you, yet outside there appears to be no hope or even damnation, a concept that is ceaselessly drummed into members. To leave the movement would mean betraying and losing all your friends (anyone who has been in the movement for many years has long since forfeited or deliberately cut off any friendships outside its confines) but you also feel that you would be betraying your family by being a bad example and putting the movement in a bad light and you are therefore reluctant to seek their support. For this reason it is highly unlikely that family members would have the least inkling of any problems. Hearing of the long and tragic experiences of others who have left the movement, I consider myself lucky; I had only been 'inside' for 9 years and was only 26 at the time of my exit and therefore still flexible enough to adapt to a new way of life and a new way of looking at the world. Although I never had suicidal feelings, I can remember moments of personal crisis during my time in the movement when I felt on the brink of madness and my behaviour was bizarre and out of character. I can understand that for someone like Bau who had been in the movement for 25 years, failure to measure up to expectations could appear to be unutterable desolation.

Extremes of depression and desperate actions could be possible in such unbalanced moments.

Marisa Bau had been based at the Focolare's village in Montet for the past fifteen years. The atmosphere at these centres is even more intense than in the small Focolare houses based in towns and cities where you at least have contact with the outside world. In these self-sufficient villages or 'towns' of the Movement, members are required to be 'up', in the jargon of the movement, at all times. When I was at Loppiano, the movement's 'town' in Tuscany, I would sometimes wonder if the illusion was not sustained by the suppressed anguish of all the inhabitants. Chiara Lubich herself once said that Loppiano could be a paradise or a terrible prison depending on ones state of mind. Bizarrely, the Focolare authorities sometimes used these centres - whose main purpose was a 'novitiate' for full-time members - as a kind of prison for members with 'problems'. The fact that generally these centres were in physically isolated locations, made them ideal for this purpose. I remember one focolarino at Loppiano at the same time as me - although some years older - who, we were told, was suffering from depression and was tormented with suicidal thoughts. What no one seemed to realise was that Loppiano was probably the last place he should be, with its pressure-cooker atmosphere, likely to aggravate his mental state and any feelings of despair or worthlessness.

When the Vatican were having problems with the African Archbishop Milengo a few years ago, they appointed the focolarini as his 'gaolers' - and very good they were at it too, according to Vaticanologist Sandro Magister of the Italian news weekly L'Espresso. One of the places they took the Archbishop was O'Higgins, the Argentinian equivalent of Loppiano, probably the remotest of all the Focolare centres, in the midst of the pampas, miles away from anywhere. It is easy to see how the intensity and isolation of such an atmosphere could trigger serious depression.

It was also my experience that the shock of leaving this rarified atmosphere even for a short period such as a holiday or visiting family - and Bau had just been on a trip to Brazil on Focolare business - could trigger a sudden crisis, or the flaring up of repressed problems. One was highly susceptible to the 'temptations' of the outside world. Manifestations of sexuality in posters, on television or in films, for instance, which the general population are so used to that they hardly notice them, could have an overwhelming impact on such 'innocents abroad'. Despite the fact that focolarini are exorted to practise 'custody of the eyes', in today's world you would have to walk around blindfolded to do this effectively. Thoughts and feelings which most people would consider normal, could be deeply disturbing and unbalancing for those used to a very sheltered environment.

At least the Focolare Movement has not tried to hush up the facts of Bau's death - which would have been difficult in view of the publicity. Even though they are forbidden to watch TV or buy newspapers, the news would inevitably filter down to internal members. But the response of Maria Voce, the successor to Chiara Lubich as President of Focolare, while sympathetic, is ambiguous and could be understood to deflect blame from the movement. She says that with Bau's death 'we see the Movement more than ever identified with the dramas of humanity today'. The implication could be that somehow Bau was contaminated by 'the world', rather than aknowledging that somehow the demands of the movement could have pushed her over the edge. When I first told the male Focolare leader in the UK that I was gay, his main concern was that I shouldn't blame the movement, an idea that had never entered my mind. There was a knee-jerk reaction to safeguard the institution first and foremost.

If indeed this was a tragic suicide, those closest to Bau, and the leadership of the movement, must surely feel compelled to examine ways in which they may have failed to meet her needs in this crucial moment of personal crisis. Many people both inside and outside the movement, including Bau's family, the civil authorities and - one would hope - the Catholic hierarchy will be asking far-reaching questions. On this occasion, smokescreens of fine spiritual words will not suffice. The one positive thing that could emerge would be an extensive enquiry into the circumstances leading up to Bau's death, including questioning structures and internal procedures as amongst possible causes, and that the results of this enquiry should be made public. If the Focolare Movement does not do this, then hopefully the civil or religious authorities will. In facing up to Marisa Bau's demons, perhaps the Focolare Movement might face up to its own.

November 28, 2011

Papal Document on New Evangelisation Imminent

November 14, 2011

Rebooting Vatican II - The Movementisation of the Church (Part 2)

October 2012 marks the 50th anniversary of the start of the Second Vatican Council. Pope Benedict has recently announced two closely-linked events to celebrate that date. On 17th October 2011, he issued a motu proprio entitled Porta Fidei - the doorway to faith - announcing that 11 October 2012 will be the start of a Year of Faith for the whole of the Catholic Church, echoing a similar event launched by Paul VI in 1967 to mark the end of the Council. The second event is the Synod on 'The New Evangelisation for the Transmission of the Christian Faith' to be organised by the newly formed Pontifical Council for Promoting New Evangelisation.

As I reported in my last post, given the key role both Benedict and his predecessor have given to the Movements in the New Evangelisation, one of the aims of the Synod will be to encourage the reception of the charisms of the Movements by the Church as a whole. Addressing an international meeting of bishops in Rome in 2008, Pope Benedict extolled the New Movements as 'a gift of the Lord, a valuable resource for enriching the entire Christian Community with their charisms.' Just as they were for his predecessor John Paul II, for the Pontiff, they are the embodiment of the New Evangelisation with their 'vigorous missionary impetus, motivated by the desire to communicate to all the precious experience of the encounter with Christ, felt and lived as the only adequate response to the human heart's profound thirst for truth and happiness.'

The New Evangelisation is also to be a basic theme of the Year of Faith which, according to the Pope's motu proprio, is to have a strong missionary impetus: 'Today too there is a need for stronger ecclesial commitment to new evangelisation in order to discover the joy of believing and the enthusiasm for communicating the faith.' He calls for the kind of public demonstration at which the Movements excel: 'All ecclesial bodies old and new are to find a way, during this year, to make a public demonstration of the Credo.' Gargantuan events such as the World Youth Day and the Holy Father's Meeting with Families, inspired and animated by the Movements, have become landmarks of the New Evangelisation. No other organisations in the Church can compete at this level: the Year of Faith will offer them opportunities for such high-profile events on a global scale, compressed within a relatively short time-frame. They will grab the headlines and dwarf the efforts of more traditional Catholic groups such as religious orders and parishes.

But what has this got to do with the Second Vatican Council? Vatican II was an epoch-making event in the history of Catholicism. No matter how much of an embarrassment its liberal tone might be to the Vatican's present incumbents, they could hardly afford to ignore this anniversary. But Pope Benedict, who has been outspoken in his criticism of the Council's reforms and its negative influence, has gone one better. With the Synod and the Year of Faith, he is rebooting the Council and making the celebrations into the launching pad for the project closest to his heart - spreading the 'Movement effect' to the whole Church.

Pope Ratzinger is certainly well acquainted with what the Council was all about. He attended as a peritus or expert theological adviser to Cardinal Frings of Cologne. At that time, he was part of the liberal majority. Since then, due to a number of personal and historical factors, his career and views have followed the classic trajectory of the neo-conservative - from forward-looking liberal to backward-looking traditionalist. But he has managed to salvage one positive element from the car-crash of the Council. By some strange alchemy, in Benedict's mind, the New Movements and the Second Vatican Council have become inextricably linked. 'The Ecclesial Movements and New Communities are one of the most important innovations inspired by the Holy Spirit in the Church for the implementation of the Second Vatican Council,' he told the bishops in 2008. 'They spread in the wake of the Council sessions especially in the years that immediately followed it, in a period full of exciting promises but also marked by difficult trials. Paul VI and John Paul II were able to welcome and discern, to encourage and promote the unexpected explosion of the new lay realities which in various and surprising forms have restored vitality, faith and hope to the whole Church.'

In fact this is a re-writing of history because none of the New Movements was actually inspired by the Council. Of the largest and most influential of these organisations, Focolare began in the forties, CL had its roots in the fifties with the Gioventu Studentesca movement of CL founder Don Giussani, and the Neocatechumenate was started in Madrid in the early Sixties while the Council was still in mid-session. Opus Dei, which denies being a movement but which strongly resembles those organisations, actually began in Spain as far back as the twenties and reflects the Catholicism of that era. What all these Movements have in common is their proud boast that they are precursors of Vatican II, that in some way they foresaw it. Unlike the traditional religious orders, therefore, that recognised the need for radical self-examination and reform in the spirit of the Council, the New Movements complacently decided that had no need to change in the Post-Conciliar period.

It is well known that, as Cardinal Ratzinger, Benedict saw the reforms that followed Vatican II as excessive, even erroneous. In the reign of John Paul II, he spear-headed a process of Restoration, turning back the clock on some of the Council's key reforms and certainly on its spirit of openness to the world and other Christian denominations. So bitter were his feelings towards the Council that in one notable interview he pronounced the New Movements 'the only good thing to come out of the Council'.

In reality Benedict's principal concern is to stem the tide of secularisation in the countries of Europe which have been traditionally Christian. On many occasions he has declared that the rot set in with the Enlightenment - two centuries ago. This world-view has more in common with that of the First Vatican Council rather than the Second. The Council of Pio Nono was called to supply 'an adequate remedy to the disorders, intellectual and moral, of Christendom', which sounds very much like what Benedict is seeking today. The orientation of the Second Vatican Council of Pope John XXIII on the contrary explicitly set out not to condemn but to find common ground with, and look for the good in, the modern world - of which Pope John saw a great deal such as the desire for peace, equality and tolerance, and such values as freedom of speech and conscience. To suggest that the conservative New Movements which, together with Benedict XVI, view the modern world, and Europe in particular, as a moral wasteland, are the first fruits of Second Vatican Council is to stand the true meaning of that historic event on its head.

'How is it possible,' Benedict XVI pointed out to the bishops in his 2008 speech, 'not to realize...that [the] newness [of the Movements] is still waiting to be properly understood in the light of God's plan and of the Church's mission in the context of our time? The important task [is to promote] a more mature communion of all the ecclesial elements, so that all the charisms, with respect for their specificity, may freely and fully contribute to the edification of the one Body of Christ.' This is Pope Benedict's goal. The not-so-hidden agenda of the Synod on 'The New Evangelisation for the Transmission of the Christian Faith' and the Year of Faith to be held in its wake, therefore, is a nothing other than a more sweeping Movementisation of the Church?

The Year of Faith - The Movementisation of the Church (Part 2)

October 2012 marks the 50th anniversary of the Second Vatican Council. Pope Benedict has recently announced two closely-linked events to celebrate that date. On 17th October 2011, the Pontiff issued a motu proprio entitled Porta Fidei, the doorway to faith, announcing that 11 October 2012 will be the start of a Year of Faith for the whole of the Catholic Church, echoing a similar event launched by Paul VI in 1967 to mark the end of the Council. The second event is the Synod on 'The New Evangelisation for the Transmission of the Christian Faith' to be organised by the newly formed Pontifical Council for Promoting New Evangelisation. As I reported in my last post, given the key role both Benedict and his predecessor have given to the movements in the new evangelisation, one of the aims of the Synod will be to encourage the reception of the charisms of the Movements by the Church as a whole.

Addressing an international meeting of bishops in Rome in 2008, Pope Benedict extolled the New Movements as 'a gift of the Lord, a valuable resource for enriching the entire Christian Community with their charisms.' Just as they were for his predecessor John Paul II, for the Pontiff, they are the embodiment of the new evangelisation with their 'vigorous missionary impetus, motivated by the desire to communicate to all the precious experience of the encounter with Christ, felt and lived as the only adequate response to the human heart's profound thirst for truth and happiness.'

But what has this got to do with the Second Vatican Council? In Benedict's mind, the New Movements and the Second Vatican Council have become inextricably linked. 'The Ecclesial Movements and New Communities are one of the most important innovations inspired by the Holy Spirit in the Church for the implementation of the Second Vatican Council,' he told the bishops in 2008. 'They spread in the wake of the Council sessions especially in the years that immediately followed it, in a period full of exciting promises but also marked by difficult trials. Paul VI and John Paul II were able to welcome and discern, to encourage and promote the unexpected explosion of the new lay realities which in various and surprising forms have restored vitality, faith and hope to the whole Church.'

In fact this is a re-writing of history because none of the New Movements was actually inspired by the Council. Of the largest and most influential of these organisations, Focolare began in the forties, CL had its roots in the fifties with the Gioventu Studentesca movement of CL founder Don Giussani, the Neocatechumenate was started in Madrid in the early Sixties while the Council was still in mid-session. Opus Dei, which denies being a movement but which strongly resembles those organisations, actually began in Spain in the twenties. What all these Movements have in common is their proud boast that they are precursors of the Second Vatican Council, that in some way they foresaw it. Unlike the traditional religious orders, therefore, that recognised the need for radical self-examination and reform in the spirit of the Council, the New Movements complacently decided that had no need for any change.

It is well known that, as Cardinal Ratzinger, Benedict saw the reforms that followed Vatican II as excessive, even erroneous. In the reign of John Paul II, he spear-headed a process of Restoration, turning back the clock on some of the Council's key reforms and certainly on its spirit of openness to the world and other Christian denominations. So bitter were his feelings towards the Council that in one notable interview he pronounced the New Movements 'the only good thing to come out of the Council'.

In reality Benedict's principal concern is to stem the tide of secularisation in the countries of Europe which have been traditionally Christian. On many occasions he has declared that the rot set in with the Enlightenment - two centuries ago. This world-view has more in common with that of the First Vatican Council rather than the Second. The Council of Pio Nono was called to supply 'an adequate remedy to the disorders, intellectual and moral, of Christendom', which sounds very much like what Benedict is seeking today. The orientation of the Second Vatican Council of Pope John XXIII on the contrary explicitly set out not to condemn but to find common ground with, and look for the good in, the modern world - of which Pope John saw a great deal such as the desire for peace, equality and tolerance, and such values as freedom of speech and conscience. To suggest that the conservative New Movements which, together with Benedict XVI, view the modern world, and Europe in particular, as a moral wasteland, are the first fruits of Second Vatican Council is to stand the true meaning of that historic event on its head.

The New Evangelisation is to be a theme of the Year of Faith which, according to the Pope's motu proprio is to have a strong missionary impetus: 'Today too there is a need for stronger ecclesial commitment to new evangelisation in order to discover the joy of believing and the enthusiasm for communicating the faith.' He calls for the kind of public demonstration at which the Movements excell: 'All ecclesial bodies old and new are to find a way, during this year, to make a public demonstration of the Credo.'

'How is it possible,' Benedict XVI pointed out to the bishops in his 2008 speech, 'not to realize...that [the] newness [of the Movements] is still waiting to be properly understood in the light of God's plan and of the Church's mission in the context of our time? The important task [is to promote] a more mature communion of all the ecclesial elements, so that all the charisms, with respect for their specificity, may freely and fully contribute to the edification of the one Body of Christ.' This is Pope Benedict's goal. Could it be that the not-so-hidden agenda of the Year of Faith, therefore, is a more sweeping Movementisation of the Church?

November 11, 2011

Ad Hominem attacks - the weapon of weakness

Fear of what? Physical reprisals? Unlikely. Attempts to silence them by threats or persuasion? Possibly.

I believe, however, that the roots of this fear reach far deeper - it is a nameless, irrational horror cultivated in members of the fate awaiting those who fall away. I remember how, when ex-members - especially those who had been in authority - left the movement, they would be spoken of in hushed tones as lost. They were the rotten apples, in foundress Chiara Lubich's words, that would infect the barrel. Lurid tales were told of how low they had sunk. The ultimate success of oppression is when the victims internalise it - self-hating gays, women who submit to laws that subjugate them, those who are downtrodden by caste or class systems and connive with their oppressors. This is evident in those who leave the movement and secretly retain the belief fed to them in their years inside that all outside it are somehow lacking and those who leave are evil or even damned.

But there is a more concrete weapon that Focolare and other similar Catholic movements employs against ex-members who go public with their criticisms, as I learned when The Pope's Armada was published. It is that form of character assassination know as the ad hominem argument, when the character of the messenger is attacked rather than the message. Apart from being fallacious, this is the argument of weakness - the last resort of those who know they are unable to counter criticism.

In my case, the first sign of what was to come occurred even before The Pope's Armada was published. The British weekly newspaper The Catholic Herald ran a front page story announcing that a critical book on the New Catholic Movements was about to be published in the United Kingdom and I was its author. Immediately, my mother received a phonecall from an English focolarina who I had encountered both socially and professionally long after leaving the movement (we both worked in the media) and who knew that I was gay and had met my partner. Anyone who knows the internal workings of Focolare would realise that this would be done with the backing of the highest authority. She quizzed my mother about the contents of the book - fruitlessly, as my mother knew nothing at that time - and then repeatedly asked her, 'Is Gordon still with *****?' As at that time I had not yet come out to my mother (she was still recovering from years of serious depression), this caused her great distress. At best this was pointless mischief-making, at worst a kind of blackmail - as if signaling what the movement was prepared to do to blacken my name. It must have come as a shock when they read the book and found that I was totally open about being gay. I had anticipated such attacks and decided that the best weapon was complete openness for my story to make sense and indeed my sexuality was central to the account of my mistreatment at the hands of the movement. I had rightly decided that the best way to counter such an organisation - which thrives on secrecy - was to go public, withholding none of the salient facts.

Interestingly, a Vatican Cardinal, when asked if he would allow me to interview him for an article I was writing, told me that he had been 'very disappointed' in The Pope's Armada. My criticisms, he opined, should have been limited to the private sphere, within the confines of the Catholic Church. Such advice now sounds hollow, even sinister after all the paedophile coverups of recent years. But it illustrates the mind-set of Rome - don't hang out your dirty linen in public. There is another reason why the Cardinal's remark was disingenuous: the Vatican deliberately ignores the evidence of ex-members of organisations. Some years ago I interviewed the postulator of the cause of Saint Jose Maria Escriva, founder of Opus Dei. The postulator was a priest member of Opus Dei (one of the changes Pope John Paul II had made to speed up the canonisation process was not to have an independent postulator and also to abolish the Devil's Advocate, whose task was to do his best to oppose the candidate's canonisation). This priest told me he had been 'very frightened' (his words) that ex-members might come forward with evidence against Escriva. He breathed a sigh of relief when the Cardinal who presided over the Congregation for Canonisations informed him that they had a policy of ignoring the evidence of ex-members.

The reaction of Focolare to the publication of The Pope's Armada lacked the refinement of the Vatican. They forbade members of the movement from reading it, backing up the ban with unrestrained ad hominem attacks, designed to undermine my credibility. They were told that I was a homosexual, had been to see a psychiatrist and was divorced. The majority of the population, at least in western society, would probably respond, 'So what?' For the sheltered members of the Focolare Movement, however,these accusations would be deeply shocking. The irony, however, was that all these points were mentioned by me in the book. Indeed, I had been sent to see a psychiatrist by my superiors in the movement in the hope that they could change my sexual orientation and that marriage had been their suggested solution to my sexual orientation - so they were to some extent implicated in my divorce as well! Subsequently, these accusations have been elaborated into libelous allegations such as one that I read in a comment on focolare.net that I had 'abandoned' my wife and 'three' children ( I have two, as far as I am aware, and still enjoy a close and rewarding relationship with them). Of course, none of these accusations have any bearing on the truth or otherwise of The Pope's Armada.

Such attacks were aided and abetted by traditionalist Catholic journalists. When The Pope's Armada was first published in the UK, it had the misfortune of being reviewed in two quality daily newspapers by prominent Catholic writers well to the right of the Catholic spectrum. One, a novelist and traditionalist Catholic, compared me to ex-nuns and monks in the 19th century who wrote salacious, largely fictional, accounts of their supposed experiences in Catholic religious orders. These accounts were probably the work of militantly anti-Catholic Protestants. The implications was that my book was also a work of fiction written with a similar purpose. I don't think any self-respecting journalist would attempt a trick like this today, but at that time the New Movements were largely unknown, even among Catholics. Nevertheless, this was just a more subtle, seemingly erudite, version of an ad hominem attack and equally weak as it did nothing to counter the facts revealed in the book. Obviously these rather over-zealous right-wing Catholics were anxious to defend Pope John Paul II - who had been such a keen supporter of the movements - and avert scandal.

Most critical reviews of exposes written by ex-members of Catholic Movements (eg Opus Dei) employ the same argument: ex-members are not to be believed because they are just settling old scores This was dramatically disproved in the case of Vows of Silence which exposed the crimes of Father Maciel, founder of the Legionaries of Christ - indeed it opened a can of worms and the truth turned out to be much worse. I believe this is the case with the New Movements. They are so impenetrable, only ex-members have had access to the evidence. The Pope's Armada also opened a can of worms and since I wrote the book I have heard many more stories, all much worse than anything that appeared in the original British edition of the book. It is important that these stories should be told in full and without fear. I can understand that for many ex-members the thought that their most intimate secrets, confided to groups or individuals while they were members, might be made public would be a source of concern. But I am convinced that the best weapon of those who have suffered at the hands of the Movements and experienced their worst aspects is total openness - ultimately far stronger than their weak, cowardly and, above all, deeply un-Christian ad hominen attacks.

November 2, 2011

'A Giant Awakens - The Movementisation of the Church (Part 1)

Given that Cardinal Ratzinger had been a vocal supporter of the Movements as John Paul II's theologian-in-chief, even to the extent of hailing them as the only good thing to come out of the Second Vatican Council, it was always on the cards that consolidating their position within the structure of the Church would be the keynote of his reign as Benedict XVI. Unlike John Paul's 'charismatic' and rather piecemeal approach to his various enthusiasms, Benedict's moves have been slower and more considered, but likely to have more impact in the long run (and of course a traditionalist like Benedict is well aware that the Church thinks and acts 'in centuries'). With his latest pronouncements, it can be said that the Movementisation of the Catholic Church is becoming a reality, confirming what the Pontiff once suggested - also while still a Cardinal - that today belonging to a Movement is the most effective way - not to say the only way - to be a Catholic.

On 17th and 18th October, the new Council held a meeting in Rome which brought together members of 33 episcopal conferences with 400 representatives of New Movements and ecclesial communities. Numbers were swelled by 10,000 younger members of the Movements. The Pope met briefly with the delegates on the first afternoon of the event and the next day for mass, hailing them as the 'new evangelisers'. The President of the Council, Archbishop Fischiella briefed the gathering on the new organisation's aim of countering secularistion both inside and outside the Church - even among the clergy! - via an explicit proclamation of the gospel. In his speech on 17th October, Benedict reiterated his desire that the primary field of mission should be the traditionally Christian countries - i.e. 'de-Christianised' Europe.

Leaders of the Movements - including Kiko Arguello, founder of the Neocatechumenate, Father Julian Carron, leader of Communion and Liberation, Adriano Roccucci of San Egidio, and Salvatore Martinez of Renewal in the Spirit - had a high profile at the event, addressing the delegates and greeting the Council's initiative enthusiastically. A report on the conservative website Zenit, bullishly entitled its report on the meeting, 'A Giant is Awakening - New Evangelisation Flows Out of Rome'.

The establishment of the new Council has been followed by an even more significant papal pronouncement - that next years Synod of Bishops will have as its subject 'New Evangelisation for the Transmission of the Christian Faith'. Speaking of the aims of the Synod on the first anniversary of the new Council last July, its President, Archbishop Fisichella, said 'We must try to give a unity to all this...listening to all these ecclesial realities - old and new - that, in these last years, have rolled up their sleeves and really implemented these methodologies of new evangelisation with great results.'

It is above all the effectiveness of the methods of the New Movements that has endeared them to Rome. The Vatican has already learned a few lessons from these organisations and imitated their methods with spectacular success. The vast World Youth Days and the Meeting of the Holy Father with Families were inspired by Focolare's Genfests and Familyfests respectively, both of which John Paul II experienced first hand, and have been hailed as quintessential examples of the new evangelisation. More recently, Benedict XVI cited Focolare's business venture, the Economy of Communion as an example to be followed in his encyclical Caritas in Veritate. He has also recently called for dialogue with non-believers, another concept borrowed from Focolare. The first practical initiative of the new Council will be the Metropolis Mission, which will target 11 major European cities during Lent 2012. This draws directly on the experience of the New Movements which have shown themselves particularly effective in urban settings. As Archbishop Fisichella has emphasised, the 'new evangelisation cannot be carried out...without new evangelisers' - ie the Movements.

This is stage one of Rome's plans for mobilising the Movements as its front line in the battle against secularisation. In my next post, I will outline stage two.

October 25, 2011

Rome must respect its own laws

For years, the Vatican swept aside well-documented accusations from former priests and seminarians of the Legionaries who claimed to have been sexually abused by Maciel. Not only did these prove to be well-founded, but it was also established that he had fathered children by at least two women, while masquerading as the saintly Founder of the order. (See Vows of Silence: The Abuse of Power in the Papacy of John Paul II by Jason Berry and Gerald Renner) Maciel's chief protector was John Paul II who was a great admirer of the priest and his traditionalist order and lay association. Benedict XVI, who as Cardinal Ratzinger headed the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith to whom the complaints had been addressed, was fully aware of the serious accusations and the compelling evidence to back them up but took no action during John Paul's lifetime. Apparently offending the Pope or his favourites outweighed the horrific wrongs that had been done to generations of boys and young men who had joined the Legionaries of Christ in good faith. Clearly it was felt that the good done by these organisations outweighed any wrong-doing and there was a danger of harming their reputation. To give Benedict his due, one of his first actions in office was to take action against Maciel personally and later to authorise the Apostolic Visitations of the Legionaries of Christ and Regnum Christi.

Given the gravity of the accusations and the publicity they had received - particularly through the book Vows of Silence - and the high profile of the Legionaries and its close association with the late Pontiff, Rome could hardly justify delaying such an investigation any longer. Furthermore since this particular scandal involved the abuse of children, an issue which has convulsed the Church worldwide and severely damaged the Church's credibility, it had to be addressed sooner or later. Other New Catholic Movements have also been the subject of complaints to Rome, often from authoritative figures such as local bishops, but, as they concerned less controversial and high-profile issues such as divisions in parishes and families , alleged brain-washing, secrecy, unreasonable demands for money etc., it was easier for Rome to sweep them under the carpet and indeed pressurise the local churches into accepting the Movements. It would be fascinating to see what aberrations a Vatican enquiry would unearth in these other organisations. One complaint that was levelled at Regnum Christi by the Apostolic Visitation, for example, was that superiors pressurised members into manifesting their consciences, that is into revealing secrets that properly belong in the context of confession. This is in direct contravention of article 630 of Canon Law which states that 'Superiors...are forbidden in any way to induce the members to make a manifestation of conscience to themselves'. In my experience this was the norm in the Focolare Movement and indeed, in the process of leaving the movement I was expected to do so with a number of authority figures to my considerable distress. In a more recent case, a member of Focolare who confessed to a superior that he had homosexual experiences in the past was summoned before a kind of kangaroo court at the Centre of the Movement in Rome and bombarded with questions on the nature of his sexual feelings and temptations. I have heard from members of the Neocatechumenate that this kind of public examination on intimate matters of conscience is commonplace.

It would be interesting to put together a dossier of just how common this practice is within the New Movements and I would welcome any experiences that former members would be willing to share. Identities would, of course, be safeguarded where necessary.

popesarmada25.blogspot.com

- Gordon Urquhart's profile

- 8 followers