C.J. Adrien's Blog

October 17, 2025

The Aesthetic of the North: What Tolkien Helped Me See About the Vikings

Welcome to the newsletter, where history, storytelling, and inspiration come together. Every week, I share some of the fun historical research or concepts I’ve encountered while writing my novels (and other things), as well as updates on my work and journey. If you were forwarded this message, you can join the weekly newsletter here.

Today’s DispatchViking History: The Aesthetic of the North: What Tolkien Helped Me See About the Vikings.

Author Update: Teaching another course on medievalists (dot) net!

This week’s book recommendation.

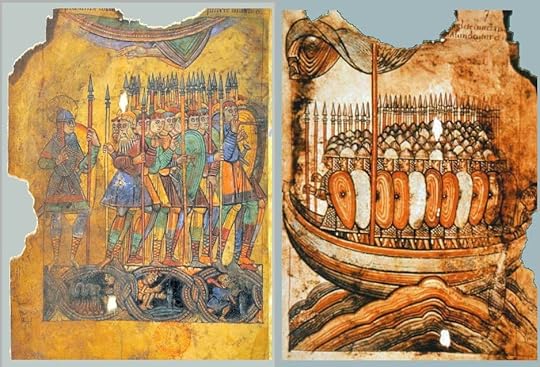

Viking HistoryThe Aesthetic of the North: What Tolkien Helped Me See About the Vikings Artwork from the Oseberg ship—a certain aesthetic.

Artwork from the Oseberg ship—a certain aesthetic.No matter where I am, be it a book fair, conference, or even in social situations with people who know what I do for a living, one question tends to come up more than any other: What do you think makes the Vikings so popular? It’s a question we’ve tackled on the Vikingology Podcast as well, but with varying degrees of success. We all have ideas about what makes them attractive to a wide, global audience, as much today as they ever did. But what is it about them exactly that we’re all drawn to?

About two weeks ago, I came across an old interview with J.R.R. Tolkien, his first and last, I believe. The interviewer asked him that tricky question they like to ask authors: Why did you write your books? His answer gave me one of those “ah-ha!” moments that make me want to jump up and down like Tom Cruise on Oprah’s couch.

He said, “One of our natural factors is wishing to create, but since we aren’t creators, we have to sub-create. Let’s say, we have to rearrange the primary material in some particular form, which pleases. It isn’t necessarily a moral pleasing, but an aesthetic pleasing.”

You can see the clip here: » Tolkien Clip «

It took me a few days of chewing over his words before the ah-ha moment occurred. I honed in on the words “aesthetic pleasing” and considered what it meant. Aesthetics, at its core, is the study of beauty—why we find certain sights, sounds, and experiences pleasing or meaningful. It poses big questions, such as what makes something beautiful, whether beauty is universal, and why humans create art in the first place. In short, it’s the branch of philosophy that explores how and why we experience beauty in the world around us.

One of the things that drew me to Tolkien was his liberal use of Norse mythology, among others. There’s a specific something about it that, when I engage with it, gives me a deep sense of satisfaction. And that’s when it hit me.

Viking art, motifs, stories, and history all share a particular aesthetic derived from the common cultural linguistic boundary of Scandinavia at the outset of the so-called Viking Age. I would describe it as rugged natural forms, intricate patterns, and a mythic fatalism that feels ancient and strangely modern.

Perhaps the reason we’re drawn to the Vikings and the Viking Age is as simple as their aesthetic pleases us. Something about it, possibly undefinable (though many have and will continue to try), speaks to us on an aesthetic level, akin to how we are drawn to striking faces or haunting melodies that we can’t quite explain.

Now, much of that aesthetic is a later invention, and that’s precisely the point. The 19th and 20th centuries saw a great deal of sub-creating, as Tolkien would call it, incorporating modern preferences into that aesthetic. That may have helped make the Vikings even more appealing.

This all led me to the ultimate conclusion that the Vikings are popular because their aesthetic pleases, and it pleases because, on some level, their world still resonates with our sense of beauty and meaning. And perhaps, as Tolkien might say, that’s all it needs to do.

Author UpdateI’ll be teaching another course on medievalists (dot) net! A battle between Bretons and Vikings from The Life of St. Aubin.

A battle between Bretons and Vikings from The Life of St. Aubin.Give the gift of a fascinating course on little-known medieval history to your loved ones (or yourself) this holiday season. Starting in January 2026, I will be teaching a course on early medieval Brittany, its struggles with its Celtic identity, against the Frankish empire, and the invasions of the Vikings.

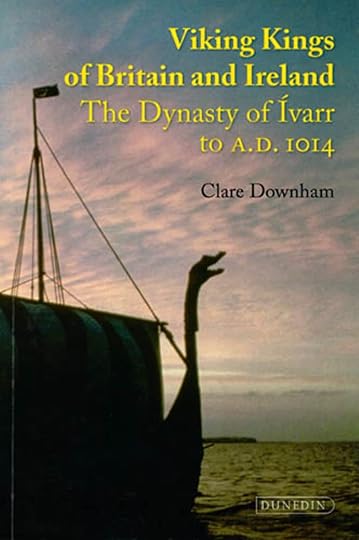

Book RecommendationsViking Kings of Britain and Ireland, by Dr. Clare Downham.

Blurb:

Vikings plagued the coasts of Ireland and Britain in the 790s. By the mid-ninth century vikings had established a number of settlements in Ireland and Britain and had become heavily involved with local politics. A particularly successful viking leader named Ivarr campaigned on both sides of the Irish Sea in the 860s. His descendants dominated the major seaports of Ireland and challenged the power of kings in Britain during the later ninth and tenth centuries. This book provides a political analysis of the deeds of Ivarr’s family from their first appearance in Insular records down to the year 1014. Such an account is necessary in light of the flurry of new work that has been done in other areas of Viking Studies. In line with these developments Clare Downham provides a reconsideration of events based on contemporary written accounts.

And, as always…Buy my novels!

October 6, 2025

What can we learn from the Vikings that will help us today?

Welcome to the newsletter where history, storytelling, and inspiration meet. Every week, I share some of the fun historical research I’ve done while writing my novels, writing reflections (and sometimes tips), and sharing updates on my work and journey. If you were forwarded this message, you can join the weekly newsletter here.

Today’s DispatchViking History: What can the Vikings teach us that can help us today?

Author Update: C.J. Adrien is featured in Ouest France! Again!

This week’s book recommendation.

Viking HistoryWhat can the Vikings teach us that will help us with our problems today?

Last week, I had the pleasure of attending a book fair at the Château de la Flocellière, where a journalist interviewed me for France’s largest newspaper, Ouest France. While the interview meandered in subject matter, the journalist posed a question at the end that gave me pause: What can we learn from the Vikings that will help us address our problems today? I could have taken my answer in several directions, such as developing critical thinking skills, understanding the progression of Western civilization, or the intrinsic pleasure of learning about a far-off time and place. My off-the-cuff answer? For me, they teach us (and indeed all historical peoples do) that our greatest obstacles today stem from the fact that we’re too comfortable and not grateful enough for it.

My Vikingology co-host, Terri, and I have tackled a related question: whether we would have liked to live in the Viking Age. Our answer—and we both agree—is an emphatic no. We enjoy our hot showers, access to modern medicine, and having survived childhood. We live today in the most privileged time in all of human history. Never before have so many people lived so long, so healthily, and so well as right here and right now (assuming you live in an industrialised nation). Childhood mortality has been so low and for so long that exceedingly few people alive today can recall any differently. It’s such an alien experience that many people have fallen for the false narratives that vaccines are a nefarious conspiracy meant to harm children. Mothers from all time periods outside the modern era, including the Viking Age, would have given anything for a medicine to prevent their children from dying from the myriad diseases vaccines now prevent.

And herein lies the crux of my answer to the journalist: what I take away from studying the Viking Age is that most, if not all, of our modern problems are essentially problems of our own making. We have it too easy. So easy, in fact, that our physiology, designed to endure the hardships of subsistence and survival in an unpredictable and unforgiving world, is working against us.

I’ve often asked aloud, “Is anyone else bothered that we’re destroying the planet so we can all be fat, sick, and miserable?” It’s a question that stems from my observation that our lives, filled with abundance and excess, have become unmanageable, and for no good reason. We’re anxious, depressed, and angry, not because our lives are hard—a Viking’s life was objectively hard—but because our lives are too easy. That has made us self-centered, self-seeking, selfish, fearful, inconsiderate, angry, and overall maladapted to a world where our every need is accessible to us at the push of a touchscreen button.

These traits are also making us less social. The so-called loneliness epidemic we’re living in is none other than the luxury of not having to cooperate with people we don’t agree with. What a privilege to be able to self-isolate! In the Viking Age, those traits would have risked our expulsion from our community, and exile was a death sentence. Community was life.

A recent book by Dr. Anna Lembke, called Dopamine Nation, has done much to bring this issue to light. Her central argument is that our brains evolved to balance pleasure and pain in a world of scarcity. Our reward circuits are designed to help us overcome starvation, being eaten, and to compete for scarce mating opportunities. In today’s society, our brains are overwhelmed by abundant sources of pleasure, from drugs to food to sex to myriad others.

Dr. Lembke describes the issue using what she calls “The gremlin theory of addiction.” She likens our reward pathways to a teeter-totter. On one side, we have pleasure gremlins, and on the other side, pain gremlins. When we seek out pleasures, it tilts the teeter-totter, and so the brain has to add more gremlins to the pain side to balance it out. But, remove the sources of pleasure, and the balance tilts back toward pain. And voilà! The brain makes us miserable to counterbalance all the pleasure. I’ll let her explain in more detail below:

The Viking Age—and I’ll focus on the Viking Age, even though what I have to say applies to most historical periods—was one of subsistence. Viking Age Scandinavians didn’t ‘betake themselves a-Viking’ because they thought it would be a fun adventure. They did it because the alternative was death. Every day was a struggle for survival. I’ve often said that Vikings were opportunists in the extreme (which I borrowed from Terri). They couldn’t go to the grocery store to top up on yogurt and ice cream. There were no doctors to treat their kidney stones. Recent studies have shown that their oral health was likely terrible. A majority of children died before adulthood. And to top it all off, even if you survived the day-to-day, there was a persistent threat that someone nearby might run out of food and come to take yours by force.

Dr. Lembke’s solution, and it’s one that I embrace, is deliberate exposure to pain and abstinence from (some) pleasures to balance out our dopamine reward system. This can take many forms, including abstaining from vices, engaging in regular exercise, fasting, and exposure to heat or cold, among others. They’re not a cure, per se, but a start to help regulate the body’s natural reward system.

Putting the effects of excess and abundance on the individual aside, there’s also the effect of a collective of people who all feel miserable. We see it today in our political discourse. The people who represent us feed into the anxiety, anger, and sadness of their constituents to great advantage. Their vitriol further enflames the discontent of the masses, and in a vicious feedback loop, misery continues to escalate.

Climate change. Authoritarianism. Disparity of wealth. War. On the surface, they seem insurmountable because we can’t seem to get along. But the ability to focus on these problems at all is a tremendous privilege in and of itself. In the Viking Age, people didn’t have the luxury of worrying about anything except their next meal and whether one of their children was going to die from a fever that night.

I am grateful to be alive today. And gratitude is the main lesson here, I believe. How terribly lucky that the people I love don’t have to die of plague, that we don’t have to fear being burned alive in our house tonight, that we have a grocery store for food, hot showers, interior plumbing, clean water, electricity, and books and movies! And how lucky that I don’t have to sail weeks on end on an open-decked longship across frigid seas just so I can scrounge enough silver together to get married! There’s an app for that now!

I’m grateful I don’t have to kill anyone just to survive.

It’s so easy to get swept up in the news and rage-baiting of the algorithms, to spiral on the state of the world, and to reach for that next dopamine hit like a baby crying for a baba to make it all better. Because we have it so good, we are all waiting for the other shoe to drop, and we’re all looking for that other shoe. That makes it harder to work together, to meet halfway in arguments, to compromise, and to otherwise keep this beautiful, perfectly imperfect wonder of a world we’ve created moving forward. I believe that a good dose of gratitude, acceptance, and exercise can go a long way in calming our minds and, perhaps, bringing us back to sanity.

To me, studying the Viking Age and being constantly reminded of their struggles gives me another perspective to frame my own challenges properly and reminds me to practice gratitude for my good fortune of living in our time, to stay focused on the here and now that I can control, and to remember that no matter what problems I face in this age of ease, they pale in comparison to the people who left home to rove. If those people (the Vikings) could make it work, then so can I.

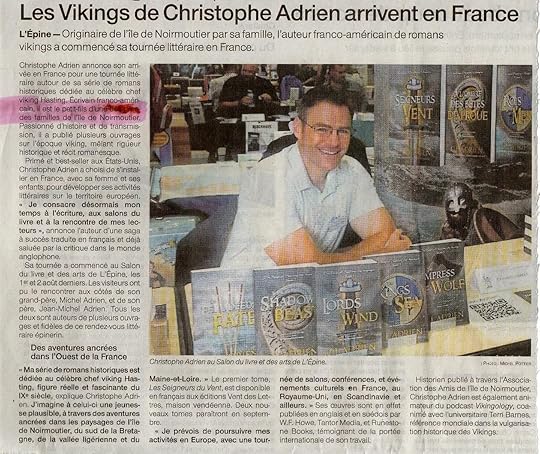

Author UpdateFeatured in Ouest France!

I had the privilege of being featured in Ouest France for the second time in as many months. My day at the Château de la Flocellière was excellent. I met many wonderful people. Thank you to Dominique Théard for organizing the whole thing!

Book RecommendationsDopamine Nation

Blurb:

This book is about pleasure. It’s also about pain. Most important, it’s about how to find the delicate balance between the two, and why now more than ever finding balance is essential. We’re living in a time of unprecedented access to high-reward, high-dopamine stimuli: drugs, food, news, gambling, shopping, gaming, texting, sexting, Facebooking, Instagramming, YouTubing, tweeting . . . The increased numbers, variety, and potency is staggering. The smartphone is the modern-day hypodermic needle, delivering digital dopamine 24/7 for a wired generation. As such we’ve all become vulnerable to compulsive overconsumption.

In Dopamine Nation, Dr. Anna Lembke, psychiatrist and author, explores the exciting new scientific discoveries that explain why the relentless pursuit of pleasure leads to pain . . . and what to do about it. Condensing complex neuroscience into easy-to-understand metaphors, Lembke illustrates how finding contentment and connectedness means keeping dopamine in check. The lived experiences of her patients are the gripping fabric of her narrative. Their riveting stories of suffering and redemption give us all hope for managing our consumption and transforming our lives. In essence, Dopamine Nation shows that the secret to finding balance is combining the science of desire with the wisdom of recovery.

September 30, 2025

Legendary, Semi-Legendary, and Historical Vikings: What's the Difference?

Welcome to the newsletter where history, storytelling, and inspiration meet. Every week, I share some of the fun historical research I’ve done while writing my novels, writing reflections (and sometimes tips), and sharing updates on my work and journey. If you were forwarded this message, you can join the weekly newsletter here.

Today’s DispatchViking History: The difference between legendary, semi-legendary, and historical figures.

Writing and Publishing: Book Fairs Are Worth It.

Author Update: A Viking tour of Western France, anyone?.

This week’s book recommendation.

Viking HistoryThe difference between legendary, semi-legendary, and historical figures. Bishop Gohard was slain by Vikings in 843, allegedly by the Viking Hasing.

Bishop Gohard was slain by Vikings in 843, allegedly by the Viking Hasing.When the History Channel started promoting their show called Vikings, they made us a promise: that it was based on real history and would offer a rare glimpse into the Viking Age, free from the tropes that had plagued it for so long. No sooner had the opening episode introduced the protagonist, Ragnar, than I knew they had not told the whole truth. While the show opened with a strong pilot and gave the appearance of historical authenticity, Ragnar was not a historical figure. He’s a legend.

And so, because of that show, my work, and indeed the history I love to learn and teach, has been plagued by this pesky mythological figure from the sagas, and he refuses to go away. This past month, I attended three book fairs in France, where, while promoting my books about a real historical figure from the Viking Age, Ragnar kept coming up. “Ragnar attacked Paris,” many folks said. “And he did that ruse to get into the city.” All wrong.

I get it. It’s not their fault. A very popular TV show that promised historical authenticity made Ragnar the protagonist in many Viking Age stories in which he was not. Not unlike the Ragnar of the Sagas, History Channel’s Ragnar was an amalgamation of figures from the Viking Age, combined into one character to tell a compelling story.

Not unlike the Ragnar of the Sagas, History Channel’s Ragnar was an amalgamation of figures from the Viking Age, combined into one character to tell a compelling story.

The trouble is that Ragnar Lothbrok is not a historical figure. His story resides in a liminal place beyond the reach of verifiable history, one that historians have come to call ‘legendary figures.’ Indeed, there are three categories: Legendary, semi-legendary, and historical.

Legendary Viking FiguresStaying with Ragnar Lothbrok as a prime example, he is considered a legendary figure primarily due to his prominent place and role in saga literature. He figures prominently in the Saga of the Volsungs, with his own subsection titled "The Saga of Ragnar Lothbrok." These sagas tell of his conquests in England and his ultimate demise in a pit of snakes. It’s compelling storytelling.

Legendary figures are so-called for their place in legends. The figures who figure in the sagas are all legendary, meaning they are the product of no small amount of mythmaking. Could some of these stories hold a kernel of truth? Of course, and we have seen examples across history of these. However, I believe we are all far too quick to use that as an excuse to make the unreal real without ample evidence. Ragnar is a prime example.

The reason Ragnar is often considered historical is due to the numerous works by historians and amateur historians attempting to prove his existence. These works have attempted to link him to several historical figures who are mentioned in chronicles and charters of the time. A certain Reginherus, who led the fleet that sacked Paris in 845 A.D. (as attested in the Annales Xantenses, Miraculi Sancti Richarii, and the translation of St. Germain of Paris), is often evoked as having been Ragnar Lothbrok. The trouble is that the story of the sack of Paris and its aftermath (where Reginherus dies of dissentary two weeks after the attack) differs so much in form from the sagas that no concrete link can be made except to say that the man’s name was likely Ragnar. Ragnar may have been a common name.

Other figures have been suggested as perhaps inspiring Ragnar, such as Rorik of Dorestad, Turgesius of Dublin, and even Hastings himself, but none have been proven. The most likely explanation is that Ragnar is indeed entirely legendary, and the tales of many others inspired his story.

A more well-known historical parallel to illustrate the emergence and role of these legendary figures is that of King Arthur. Arthur, most of us will agree, is a myth, and the product of medieval literature more than anything else. And yet, serious efforts have been made over the years to prove that there may have been a real person who inspired the story. Most of these claims stem from Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia Regum Britanniae, which mentions a potential candidate—a Roman soldier—whose story may have later inspired Wace, Chrétien de Troyes, and others. Again, the trouble is that none of these links can be confirmed. Furthermore, the story of Arthur we know and love today is the product of the collective imagination of the society in which his story circulated. The same is true of Ragnar and the other legendary figures of the Viking Age.

Semi-Legendary Viking FiguresAs we say in French, “les choses se compliquent” (things get more complicated) when we enter the semi-legendary space. Semi-legendary figures are those who appear in sagas considered more historical (such as the Sagas of the Icelanders), are attested in saga literature and historical sources, have some archaeological support, or a combination of all of these.

Leif Eriksson is a notable example of a semi-legendary figure. He appears in the Sagas of the Greenlanders, which were considered, for many years, to be part fabrication with a kernel of truth from oral storytelling, and then, surprisingly, confirmed, at least in part, by the archaeological find of a Norse settlement in Newfoundland. Now, whether Leif Eriksson existed in the flesh is up for debate—he’s not mentioned in any contemporary sources, nor did he leave us any written testimony of his own. Herein lies one of the issues with Viking figures: they did not write anything down, making the work of historians all the more frustrating.

Undoubtedly, there are people who will argue that Leif Eriksson is a historical figure. The argument is that his name was transmitted through oral tradition. While this is true in many cases, the issue with oral tradition is that, although it occasionally provides us with evidence, it is, on the whole, unreliable. This unreliability is further exacerbated by the fact that those oral traditions were written down by people who did not necessarily practice them. And so we are left with the frustrating middle ground of leaving these historical figures to semi-legend.

Leif Eriksson joins a long list of these figures, including most of the earliest kings and jarls of Viking Age Scandinavia, who are attested in sagas such as the Ynglinga Saga (also known as the Saga of the Yngling Dynasty, or the kings of Norway).

Historical Viking FiguresHistorical figures are those whose existence can be confirmed through contemporary sources. They are those Vikings whose names made it into the annals, diplomas, charters, and cartularies of those people who had the ability and willingness to write down the stories of their deeds in the time that they did them. A single source will not do. As we discussed above, what cannot be confirmed lives in the semi-legendary realm. Historical figures can be confirmed through cross-referencing of sources, with multiple mentions of them within a narrow timeframe and specific geographical location.

That they are historical does not mean they have escaped the tendency of mythmaking by later chroniclers and historians. In fact, many of these figures took on larger-than-life proportions over the twelve centuries since their deeds were recorded. What’s important is that we can confirm their existence through contemporary sources.

My favorite example (because, of course!) is the Viking warlord Hasting (also spelled Hastein, Hastæn, and Alsting). In contemporary sources, he first appears in the Chronicle of Nantes for the year 843, allegedly having assisted the Bretons to defeat the Franks before moving on to sack the city. While the chronicle of Nantes has been questioned for some of its obvious fabrications, the events of that year it describes are confirmed in large part by the Annales d’Agoulême and the Annales de Saint-Bertin.

Later, Hasting reappears in the 860s in a flurry of mentions by the Chronicles of Regino Prüm, confirmed by the Annales de St. Bertin, the Annales de St. Vaast, and a handful of diplomas—including a land grant for Chartres—as a fidelis of King Charles.

Hasting was such an active force of chaos that later medieval historians featured him prominently in their histories. He is a tidal force of nature in the Gesta Normanorum, receiving no fewer than 150 epithets to describe his villainy. In the Gesta Danorum, he joins Bjorn Ironsides on a legendary adventure in the Mediterranean. And perhaps the most curious of these medieval histories is that of Raoul Glaber, who claimed to have worked from contemporary sources now lost to history to put forward a narrative that places Hasting at all the major raids in Nantes, Angers, Orléans, Tours, and even Paris through the 840s, 850s, and 860s. Short of finding the sources he used to verify his claims, his narrative remains in question.

Hasting was a real Viking whose exploits were recorded enough for us to say that he was a historical figure.

Why this mattersThe Viking Age has fallen victim to modern mythmaking to a much greater extent than most other historical periods. This could partly be due to the mythmaking they themselves did, and that their victims later did to them. It’s essential, however, to understand where the line between fact and fiction lies because ignoring it means ignoring the truth you can hold in your hands and opening yourself to believing all sorts of silly ideas. It’s an exercise in critical thinking to look at narratives about the past and to question them, and to put in the effort to understand what’s real and what’s myth. Good critical thinking skills are essential to survive in today’s madhouse of a media landscape, where fact and fiction swirl together like the Tasmanian devil’s tornado.

Writing and PublishingBook Fairs Are Worth It.This past month, I attended three book fairs in a row, first at the Domaine de Roiffé, then at the Salon de Noirmoutier, and most recently at the Chateau de la Flocellière. I was able to learn a great deal about how book fairs work in France, their value to authors, and where they will fit in my ‘author business plan’ moving forward.

Book fairs are great for meeting readers.At the salon de Noirmoutier, I was overjoyed by how many people came just to see me and meet me. In 2019, I gave a lecture to the community about the Vikings and sold some 1,000 copies of the French version of The Lords of the Wind. Many people remembered me and, despite my long absence during and after Covid, still came out to see me again and chat about Vikings, writing, and other things. The support from readers was a big boost to my morale as an author.

Book fairs are great for meeting other authors.The book fair at the Domaine de Roiffé was a dud. A dozen or so people showed up in total, so it was a slow day. Still, I spent the day networking with other authors, learning about their works, inspirations, and goals, and it was a pleasure to start building a community of like-minded people. I had not had many opportunities to meet other authors before, and so this was a delightful part of my book fair experience.

Book fairs are not a great sales channel.I would be remiss if I omitted mentioning that I was disappointed by the sales volume. At each fair, I sold the most books of any other author there (because Vikings sell!!!), but that volume was much lower than I had anticipated. Still, people bought, so it wasn’t a total loss. However, I was forced to reframe book fairs in my author business plan.

But they are great for marketing.Get known. That’s rule #1 of marketing. And these book fairs were not only great for local exposure, but also an opportunity to create content for my online channels. What a privilege it has been to travel through France and visit so many amazing historical sights along the way! I’ve created many videos of my travels, inviting my readers to share in this journey. TikTok seems to be the most interested. If you have a chance, check out my TikTok, Instagram reels, etc, to see the tremendous sights I’ve had the privilege of visiting.

Stay tuned for more book fairs to come. I’ll be at Barbatre end of October, Riantec in November, and Noirmoutier again for the Christmas market in December.

Author UpdateA Viking Tour of Western France, Anyone?I am starting to put together a ‘Viking Tour of Western France’ tour group for summer 2026 and am looking for 20 individuals who are interested. Thanks to some wise advice from fellow author Octavia Randolph, who does tours of Gotland, I plan to bring her same mix of travel, history, and literary intrigue to my region of France. You’ll get to visit these important sites with me as your guide. The goal will be to follow Hasting’s journey (loosely) from Noirmoutier to Paris (books 1-3).

Here is a tentative itinerary of spots we would visit:

Start in Noirmoutier at the castle and the church of St. Philbert (for the crypt).

Go sailing on the Viking ship Olaf D’Olonne in Les Sables D’Olonne.

Visit the 1,200-year-old priory at St. Philbert de Grand Lieu.

Visit the Château de Nantes.

Visit the Cathedral of Nantes.

Learn about Namborg (Viking Nantes) from a local Viking reenactment group.

Visit le Puy du Fou (to explore modern interpretations of the Vikings in France)

Visit the Viking fort in Brittany.

Visit the Viking village in Normandy.

Move inland to Rouen.

End in Paris at the foot of the wall the Vikings climbed in 845 A.D.

If you are interested in joining my waiting list, please email me at author@cjadrien.com to express your interest, and I will add you.

Thank you!

Book RecommendationsThe Oxford Illustrated History of The Vikings

Blurb:

With settlements stretching across a vast expanse and with legends of their exploits extending even farther, the Vikings were the most far-flung and feared people of their time. Yet the archaeological and historical records are so scant that the true nature of Viking civilization remains shrouded in mystery.

In this richly illustrated volume, twelve leading scholars draw on the latest research and archaeological evidence to provide the clearest picture yet of this fabled people. Painting a fascinating portrait of the influences that the “Northmen” had on foreign lands, the contributors trace Viking excursions to the British Islands, Russia, Greenland, and the northern tip of Newfoundland, which the Vikings called “Vinlund.” We meet the great Viking kings: from King Godfred, King of the Danes, who led campaigns against Charlemagne in Saxony, to King Harald Bluetooth, the first of the Christian rulers, who helped unify Scandinavia and introduced a modern infrastructure of bridges and roads. The volume also looks at the day-to-day social life of the Vikings, describing their almost religious reverence for boats and boat-building, and their deep bond with the sea that is still visible in the etymology of such English words as “anchor,” “boat,” “rudder,” and “fishing,” all of which can be traced back to Old Norse roots. But perhaps most importantly, the book goes a long way towards answering the age-old question of who these intriguing people were.

September 24, 2025

The Fell Deeds of Fate is a 2025 Reader's Favorite Awards Winner!

The Fell Deeds of Fate is a 2025 Reader’s Favorite Awards Winner!

The Fell Deeds of Fate is a 2025 Reader’s Favorite Awards Winner!The saga of Hasting the Avenger has reached new heights. The Fell Deeds of Fate, Book IV in C.J. Adrien’s internationally acclaimed Viking series, has officially been named a 2025 Reader’s Favorite Award Winner!

For those unfamiliar, Reader’s Favorite is one of the most respected international book award contests in the industry. With thousands of entries from over a dozen countries each year, their panel of judges—composed of publishing professionals, authors, and avid readers—recognizes the best books across genres. To rise from the sea of competitors and seize victory is no small feat. This is a mark of quality, honor, and recognition that few books earn.

But the glory doesn’t end there. The Fell Deeds of Fate was also highly praised by Kirkus Reviews, one of the most prestigious and notoriously discerning voices in publishing. Kirkus rarely gives high commendation, and when they do, readers know it means the work is something special.

So what makes this novel stand apart? In The Fell Deeds of Fate, the indomitable Viking chieftain Hasting turns his eyes toward Constantinople, the heart of empire, where the clash of swords meets the clash of destinies. It’s a tale of ambition, power, and the peril of chasing immortality—crafted with the grit, blood, and thunder that true Viking sagas demand.

If you crave shield-walls and storm-tossed seas, if you hunger for tales as sharp as a battle-axe and as fierce as Odin’s wrath, then this book belongs in your hands.

⚔️ The Fell Deeds of Fate has claimed its laurels. Now it’s time for you to claim your copy. Join the shield-wall—buy the book today! 👇September 15, 2025

Comment un monastère est devenu une forteresse face aux raids vikings.

Château de Noirmoutier, supposé avoir été construit à la base pour repousser les Vikings.

Château de Noirmoutier, supposé avoir été construit à la base pour repousser les Vikings.La semaine dernière, nous avons étudié l’exemption de péage accordée en 826 par Pépin Ier, un aperçu révélateur de la manière dont la politique royale s’adaptait à la pression croissante de l’activité viking le long de la Loire. Cette exemption montrait clairement qu’au milieu des années 820, les raids scandinaves étaient suffisamment perturbateurs pour justifier d’accorder aux moines de Saint-Philibert un allègement financier. Cela venait s’ajouter à la charte de 819, qui avait donné à l’ordre de Saint-Philibert le droit de construire et de se réfugier chaque année, pendant la saison des raids, dans un prieuré satellite plus en retrait, appelé Déas.

Cette semaine, nous avançons de quelques années, jusqu’en 830, lorsque la situation est passée de concessions fiscales à une tentative de fortification physique. Un diplôme royal daté du 2 août 830 indique que les moines de Saint-Philibert avaient fortifié leur maison insulaire sur Herio et reçu la permission impériale d’y poster des hommes pour garder le castrum. Le même acte rapporte que, malgré cette fortification, la communauté quittait encore l’île chaque été pour se réfugier à Déas. Il souligne même les difficultés de ce déplacement : transporter les biens de l’église était ardu et le service divin cessait sur l’île en leur absence. Une forteresse, une garnison et un départ saisonnier programmé témoignent d’un risque ordinaire et récurrent, et non d’une urgence ponctuelle.

Ce document s’inscrit dans une série d’indices qui décrivent déjà la menace comme répétitive. En 819, l’abbé Arnulf avait obtenu l’autorisation d’utiliser Déas comme refuge face à des incursions fréquentes. Le ton des sources ne se relâche pas dans les années 820. Le prologue des Miracles d’Ermentarius — Ermentarius de Noirmoutier était un moine du IXᵉ siècle et prétendu témoin oculaire de certaines attaques vikings ; il nous a laissé l’une des premières sources narratives dans ses Miracles de Saint Philibert — se plaint des perturbations constantes causées par les Normands, surtout pour les familles liées au service du monastère, et mentionne les habitants des îles fuyant avec leur seigneur. Plus tard, le Livre II situe le comte Renaud d’Herbauge combattant les Vikings tout en défendant le castrum. Que cet affrontement ait eu lieu exactement en 835 ou une année voisine importe peu : il confirme que la forteresse avait été construite pour faire face à un problème durable.

Cet élément est essentiel pour raconter l’histoire de la Loire avant que les grandes annales ne prennent le relais. Le diplôme de 830 implique que la fortification avait déjà eu lieu et que l’évacuation estivale était devenue une habitude. En d’autres termes, la « fréquence et l’intensité » des raids scandinaves mentionnées en 819 ne s’étaient pas atténuées au cours de la décennie suivante. Elles se sont poursuivies durant les années 820 et, en 830, avaient engendré une politique permanente sur Herio : construire, garder et, quand la saison change, partir.

Si les premières parties de cette série s’interrogaient sur le fait de savoir si 799 marquait un début et si le rythme s’était maintenu, cette entrée fournit la preuve administrative. Une charte qui autorise la mise en garnison est une réponse gouvernementale à une menace connue et répétée. Lue parallèlement au témoignage d’Ermentarius et à la mention des combats au fort, l’image est claire : des raids scandinaves réguliers le long de la basse Loire sont déjà attestés avant les notices mieux connues des grandes annales.

Aujourd’hui, en visitant le château de Noirmoutier, les visiteurs découvrent son histoire, notamment comment il fut construit pour repousser les Vikings et reste le plus ancien château de France. Bien que rien ne prouve que le château actuel descende directement du castrum édifié contre les Vikings, une chose est certaine : moins de trois décennies après le début des trois siècles que l’on appellera « l’Âge des Vikings », ces derniers avaient déjà un impact.

L’idée du castrum est un élément central de mes romans. Dans le deuxième tome, À l’ombre de la Bête, mon personnage principal, Hasting, s’empare du castrum et du monastère pour en faire sa base d’opérations dans la région.

Si tu ne veux pas attendre la semaine prochaine pour découvrir la prochaine phase de l’expansion viking dans le royaume carolingien, vis-la dès maintenant dans ma série La Saga d’Hasting le Vengeur, qui culmine avec la bataille épique sur l’île de Noirmoutier entre une armée franque et le plus célèbre chef de guerre viking de tous les temps : Hasting.

Sources (via Cartron, p. 34, n. 12) : Diplôme du 2 août 830 (éd. L. Maître, Cunauld, son prieuré, ses archives, 250–253), avec confirmations dans les Annales Engolismenses (MGH SS XVI, a. 834, 485) et le Chronicon Aquitanicum (MGH SS XVI, a. 830, 252) ; Ermentarius, Miracula I, Prologue ; Miracula II, c. XI.

Si vous ne voulez pas attendre la semaine prochaine pour en savoir plus, plongez-vous dans mon premier roman, Les Seigneurs du Vent, qui culmine avec l’épopée de la bataille de l’île de Noirmoutier entre une armée franque et le plus célèbre chef de guerre viking de tous, Hasting.

Et comme toujours…Achetez mes romans !

Was Noirmoutier Used as a Viking Wintering Base?

Bishop Gohard being slain by Hasting at the sack of Nantes, 843

Bishop Gohard being slain by Hasting at the sack of Nantes, 843It all starts with the entry for the year 843 in The Annals of St. Bertin, which relays to us the sack of Nantes in 843 as follows: “Northmen Pirates attacked Nantes, slew the bishop and many laypeople of both sexes, and sacked the civitas…finally, they landed on a certain island, brought their households over from the mainland and decided to winter there in something like a permanent settlement.”

The fall of Nantes shocked the entire empire, with one chronicle describing it as an apocalypse. Ermentarius relays that they sailed up the Loire with 67 ships, and the Annals of Angoulême suggest they were Vestfaldingi, or men from the Vestfold region of Norway. More intriguing to our purpose here is the mention in the Chronicle of Nantes, which was composed using earlier manuscripts, that directly references the island of Noirmoutier (then called Herio) as a wintering base for the Vikings.

The Annals of St. Bertin, along with the Chronicle of Nantes, seem to confirm Noirmoutier as a Viking base. However, there is an issue. Although the Chronicle of Nantes is recognized as a medieval document, it has been questioned for including later embellishments, such as the mention of Charles the Bald as king of France in 843. Therefore, we must approach its information with great caution. Whether Noirmoutier was used as a wintering base remains uncertain. As a result, we need to consider two other pieces of evidence that, when combined with the Chronicle of Nantes, support the theory.

First, the Annales of Angoulême tell us that a large fire erupted on the island in 846, destroying any settlement there. Several historians see this as evidence of a permanent settlement on the island, which was then destroyed after about ten years. Second, we have a report from a slightly farther source—from Andalusian Spain—by the envoy al-Ghazal, who traveled north with the Vikings who sacked Seville in 844 to learn more about them, as had been agreed with Emir Abdu al-Rhaman. Al-Ghazal describes that the fleet stopped on the French coast to resupply, where the Vikings had built a beautiful, prosperous port town before moving on to what historians believe was Ireland. Again, the island of Noirmoutier is not explicitly mentioned, but given the context of references in the Annals of St. Bertin, the Annals of Angoulême, Ermentaire, and the Chronicle of Nantes, the timing and location of al-Ghazal’s account seem to possibly confirm the base.

Like many aspects of the Viking Age, we can't definitively say that Noirmoutier served as a wintering base based on our current sources. However, we do have one more piece of evidence to add to the puzzle: the later pattern of how the Vikings conducted their raids in the region as they moved inland. Noirmoutier marked the start of over a century of Viking activity in the area. Beginning in the 840s and into the 850s, a clear strategy emerges. The Vikings established wintering bases in the lower Loire River Valley, starting with Nantes in 853, Mont-Glonne in 854, and further upriver in 856 and 866, each location bringing them closer to key targets like Angers, Tours, and Orléans, which they repeatedly sacked. Adrevald, a monk who wrote the Miracles of St. Benoît, notes that the Northmen built cottages as wealthy as a ‘Bourg’ (or wealthy trade town).

The establishment of bases across the Loire River Valley sets a precedent for the strategy used by the Vikings, making the base on Noirmoutier even more believable. If Nantes was their primary target, it makes sense they would have set up a settlement nearby to receive, sort, and ship their loot. However, as their targets moved inland, they shifted their bases accordingly, even using their former target of Nantes as a new base. As the Annals of St. Bertin tell us, in 853, “Danish pirates from Nantes heading further inland brazenly attacked the town of Tours and burned it.”

We have strong indications from the sources that Noirmoutier was used as a wintering base by the Vikings, although a clear ‘smoking gun’ remains elusive. By piecing together various partial mentions and establishing a pattern of behavior consistent with such activity, I believe we can make a solid case for Noirmoutier being a Viking settlement for at least ten years.

The settlement of Noirmoutier, its destruction, and the sack of Nantes are all pivotal events in my series, The Saga of Hasting the Avenger.

Did you enjoy this article?

And, as always…Buy my novels!

September 9, 2025

L’exemption de péage de Pépin en 826 et ce qu’elle peut nous dire sur l’activité viking durant une décennie « silencieuse ».

A coin of Pépin I of Aquitaine.

A coin of Pépin I of Aquitaine.La semaine dernière, nous avons étudié l’attaque viking sur l’île de Bouin en 820 dans le contexte de la charte de 819, qui avait ordonné le transfert du monastère de Saint-Philbert à Déas pendant la saison des raids. Après cela, les sources se raréfient. Les Annales de Saint-Bertin ne commencent qu’au cours des années 830, de sorte que la côte ligérienne dans les années 820 se situe dans une zone de silence documentaire. C’est là qu’une charte conservée reprend le fil.

Le 18 mai 826, à Pierrefitte, Pépin Ier d’Aquitaine confirma un précepte antérieur de Louis le Pieux et accorda à Saint-Philbert six bateaux exempts de péage sur ses fleuves. Le texte ressemble à une mesure de politique visant à maintenir une économie fragilisée en mouvement. Le monastère de Saint-Philbert partageait alors sa vie entre Herio (Noirmoutier) au large et Déas, sur le continent près du lac de Grand-Lieu ; les bateaux reliaient ces deux pôles.

Le document est clair sur son objet et sa portée :

« … immunes ab omni teloneo … per alveum Ligeris, Helerium, Carim … per caetera diversa flumina ob necessitates ipsius monasterii fulciendas. »

« exempts de tout péage … sur la Loire, l’Allier, le Cher … et sur d’autres rivières afin de pourvoir aux besoins du monastère. »

Il interdit aussi des exactions désignées « en langue vulgaire », ces petites taxes qui s’accumulent à chaque escale :

« Nullus … teloneum, quod vulgari sermone dicitur ripaticum aut portaticum aut salutaticum … »

« Que nul n’ose prélever un péage appelé en langue vulgaire … »

Et il fixe la règle d’usage en énumérant les fleuves :

« cum eisdem sex navibus libere ire et redire sive per Ligerem, Helarium, Carim, Dordoniam, Garonnam… »

« avec ces mêmes six navires libres d’aller et revenir sur la Loire, l’Allier, le Cher, la Dordogne, la Garonne… »

Le commerce est autorisé si nécessaire :

« Quod si mercandi vel vendendi gratiam … facient, … nihil … ab eis exigi praesumatur. »

« S’ils ont besoin d’acheter ou de vendre, ils peuvent le faire, et rien ne doit leur être exigé. »

Que nous apprend ce document ? La production économique de l’île importait à Pépin. Laisser Saint-Philbert dépérir aurait étouffé les biens et revenus dont il dépendait. Il intervint donc pour sauver l’abbaye afin que sa valeur ne s’effondre pas. L’objectif est explicité dans le texte : « pourvoir aux besoins du monastère. » Des besoins, pas des luxes.

C’est ici que le vide narratif nous oblige à raisonner par contexte. Nous avons 820 (Bouin) comme événement-choc. Nous avons 819 comme adaptation institutionnelle avec le transfert à Déas à cause des « incursions fréquentes ». Puis 826 comme soulagement fiscal. La charte ne mentionne jamais les « raids » ni le « sel ». Elle n’énumère pas de cargaisons, n’offre aucun registre comptable. Et pourtant, la politique correspond bien à une abbaye cherchant à maintenir ses lignes d’approvisionnement dans une décennie où la violence et les péages fragilisaient les déplacements. Certains historiens, dont les travaux portent sur les pérégrinations des moines de Saint-Philbert à l’époque viking, considèrent cette charte comme révélatrice. L’image qui s’en dégage est celle d’une organisation sous tension, en raison de perturbations économiques antérieures ou continues causées par les raids vikings.

Il existe toutefois d’autres lectures à garder à l’esprit. Les souverains accordaient parfois des exemptions de péage pour des motifs non liés à une crise : pour remercier une abbaye de l’aide apportée dans une affaire spirituelle, pour expier une faute, ou par simple piété déguisée en politique. Certaines expressions de la liste des péages varient selon les copies. Les noms des fleuves présentent de légères différences d’orthographe. Il faut reconnaître ces coutures.

Même avec ces réserves, la structure tient. Si l’on efface le silence narratif des années 820, on distingue une suite de mesures pragmatiques : se déplacer vers l’intérieur pour plus de sécurité, protéger les bateaux qui transportent les biens, réduire les frais qui rendent chaque voyage déficitaire. En bref, l’acte de 826 est un outil destiné à maintenir les flux financiers et les approvisionnements pendant que la côte restait instable.

Lorsque les annales reprennent dans les années 830, on voit que ce répit n’était sans doute que de plume, et que les eaux au large de la Bretagne et de l’Aquitaine grouillaient de requins d’Odin. C’est là que nous reprendrons la semaine prochaine : avec le drame des incursions répétées sur l’île de Noirmoutier et la décision exceptionnelle de Pépin de leur accorder une charte pour construire un castrum afin de se défendre.

Si vous ne voulez pas attendre la semaine prochaine pour en savoir plus, plongez-vous dans mon premier roman, Les Seigneurs du Vent, qui culmine avec l’épopée de la bataille de l’île de Noirmoutier entre une armée franque et le plus célèbre chef de guerre viking de tous, Hasting.

Et comme toujours…Achetez mes romans !

September 8, 2025

The First Domino: The Fall of Noirmoutier to the Vikings

The battle of Noirmoutier, 835; by Dall-E.

The battle of Noirmoutier, 835; by Dall-E.Last week, we examined the monastery of St. Philbert’s attempts in 830 to defend itself against what had been described as early as 819 as ‘frequent and persistent raids’ by the Vikings. This week, we will move forward a few years—though how many precisely is up for debate—to a most spectacular clash between the Franks and the Vikings. The episode shines a light on the difficulties the Carolingians faced in defending key economic nodes while the empire descended into political turmoil.

The castrum constructed in 830, along with the soldiers hired to defend it, did not appear to provide the monks with sufficient confidence to remain on the island of Noirmoutier during the raiding season. Instead, they appear to have continued their annual migration to their satellite priory on Grand-Lieu Lake. While the record on what happened thereafter is sparse, by 830, we start to see the chroniclers pick up where the cartularies, letters, and diplomas we relied upon for information up to then left off. Most pertinent among these for our exploration of the events of 835-836 are three primary sources that, together, give us an indication of the dire situation the monks of Noirmoutier faced.

First, we have the Annals of St. Bertin, which begin in 830 with a record of the challenges Emperor Louis the Pious faced with his sons. Louis was determined to bring the region of Brittany, then in open rebellion, back under the Frankish yoke. But his nobles refused to muster on his behalf. The chronicle continues to focus on the internal political turmoil that ensued until the entry for the year 836, when it mentions an attack by Northmen on the port city of Dorestad and the surrounding areas. The chronicler appears determined to highlight what a shock this event was to the Carolingian world, and a shock it was. Except, read on its own, we seem to be given the impression that this attack happened as a singular event.

The year 836 was a consequential one for Viking raids. Ermentaire of Noirmoutier recalls in his Life of St. Philibert witnessing a battle between the Franks and the Northmen on his island that summer. His testimony is confirmed by the Annals of Angoulême, which relay to us that the count of Nantes, Renaud, whose name is written as Rainald in the Annals of St. Bertin, mobilized an army to defend the island in 836. While there is a disagreement in the dates for the event, we can say with a certain degree of certainty that the events evoked took place.

Between the two testimonies, we may deduce that a Frankish army indeed traveled to the island during raiding season and successfully made contact with a Viking fleet. They fought a battle in front of the castrum, and the Franks won the day. According to Ermentaire, his patron saint assisted the Franks in the fight by frightening the Northmen in a ghostly form, allowing the Franks to rout their enemy with no casualties on their side. The Annals of Angoulême provide a dryer account, but support the idea that the battle was an overwhelming victory for the Franks.

Victorious, the Franks returned to Nantes, assured that the Northman scourge had been neutralised. Except, it hadn’t. Both sources report that another fleet arrived in the autumn and retook possession of the castrum. The monks fled once more, but this time, they never returned. Ermentaire writes for the year 836 that the order of St. Philbert definitively abandoned the island.

What do the raid on Dorestad and the battle on Noirmoutier have to do with one another? Perhaps nothing. But together they may paint a broader picture of Viking activity in France in the early 830s, and even the 820s. The raid on Bouin happened after the fleet that sacked it had been repelled in Frisia. Is it a coincidence, then, that the battle on Noirmoutier and the raid on Dorestad occurred around the same time? Or are we seeing the continuation of a pattern ratcheting up in intensity?

Current scholarship does not yet connect the two. They are both considered to have been part of Lucien Musset’s proposed first phase of Viking expansion, termed ‘sporadic raiding,’ implying that there was no discernible pattern behind the raids other than finding a gap in the Carolingians' defenses. While this notion is true to a significant degree, I believe the confluence of these two events supports the idea that the Vikings were much more organized and intentional about their approach to the Frankish realm than previously recognized in the first three decades of the so-called Viking Age. See my article on the Vikings and salt.

In any case, the year 836 marks the beginning of the ‘established’ timeline for Viking activity in the Carolingian empire. As we will see next week, once Noirmoutier fell, so too did the gates of Hel (mispelling intentional) open for the Franks.

The final act of my novel, The Lords of the Wind, is, in fact, based upon the battle of 835-836.

Did you enjoy this article?

Author Update: An Award-Winner Once More!

The Fell Deeds of Fate, the fourth installment in my Saga of Hasting the Avenger, just won a bronze medal with the Reader’s Favorite Book Awards 2025! This comes on the heels of The Fell Deeds of Fate becoming a top-recommended book through Kirkus Reviews.

It’s days like these that I think maybe, just maybe, I’m doing something right.

This is my second Reader’s Favorite Award. The Lords of the Wind took home the gold medal in 2020.

And, as always…Buy my novels!

September 1, 2025

How a Monastery Became a Fortress in the Face of Viking Raids.

Châteaux de Noirmoutier, allegedly first built to fend off the Vikings.

Châteaux de Noirmoutier, allegedly first built to fend off the Vikings.Last week, we looked at Pépin I’s toll exemption of 826, a revealing glimpse into how royal policy adapted to the growing pressure of Viking activity along the Loire. The exemption made clear that by the mid-820s, Scandinavian raids were disruptive enough to justify granting Saint-Philibert’s monks financial relief. This was in addition to the charter from 819, which had given the order of St. Phiblert the right to construct and flee to a satellite priory, called Déas, further inland each year during raiding season.

This week, we move forward just a few years to 830, when the situation had escalated from fiscal concessions to an attempt at physical fortification. A royal diploma dated 2 August 830 says the monks of Saint Philibert had fortified their island house on Herio and received imperial permission to post men to guard the castrum. The same act reports that, despite the fort, the community still left the island each summer for Déas. It even notes the headaches of that move: transporting church goods was hard, and divine service on the island stopped while they were away. A fort, a garrison, and a scheduled seasonal withdrawal point to an ordinary risk that returned year after year, not a single emergency.

The document sits in a line of evidence that already casts the threat as recurring. In 819, Abbot Arnulf obtained approval to use Déas as a refuge in the face of frequent incursions. The tone in the sources does not relax in the 820s. The prologue to Ermentarius’ Miracles—Ermentarius of Noirmoutier was a ninth-century monk and alleged eyewitness to some Viking attacks, and he left us one of the earliest narrative sources in his Miracles of Saint Philibert—complains about constant disruptions by the Normans, especially for the families attached to the monastery’s service, and mentions inhabitants of the islands fleeing with their lord. Later, Book II places Count Renaud of Herbauge fighting the Vikings while defending the castrum. Whether that clash occurred exactly in 835 or another nearby year, it confirms that the fort was built to address a problem that would not go away.

This matters for how we tell the story of the Loire before the big annals pick up the narrative. The 830 diploma implies that fortification had already taken place and that the summer evacuation was already a habit. In other words, the ‘frequency and intensity’ of Scandinavian raids noted in 819 did not fade during the decade that followed. They persisted through the 820s and by 830 had produced a standing policy on Herio: build, guard, and when the season turns, leave.

If earlier parts of this series asked whether 799 began something and whether the rhythm continued, this entry provides the administrative proof. A charter that authorizes guards is a government response to a known and repeated threat. Read alongside Ermentarius’ testimony and the notice of fighting at the fort, the picture is clear. Regular Scandinavian raiding along the lower Loire is already visible before the better-known entries in the major annals.

Today, when visiting the castle of Noirmoutier, visitors can learn about its history, including how it was built to repel the Vikings and stands as the oldest castle in France. While the evidence is lacking to show that the castle that stands there today is in any way derived from the castrum intended to fend off the Vikings, one thing remains certain: not three decades into the three centuries that would become known as ‘The Viking Age’ the so-called Vikings were already having an impact.

This idea of the castrum is a central component of my novels. In the second tome, In the Shadow of the Beast, my main character Hasting takes the castrum and monastery over to use as his base of operations in the area.

If you can’t wait until next week to hear about the next phase of Viking expansion in the Carolingian realm, live it in my series, The Saga of Hasting the Avenger, which culminated in the epic battle on the island of Noirmoutier between a Frankish army and the most notorious Viking warlord of them all, Hasting.

Sources (via Cartron, p. 34, n. 12): Diploma of 2 Aug. 830 (ed. L. Maître, “Cunauld, son prieuré, ses archives,” 250–253), with confirmations in the Annales Engolismenses (MGH SS XVI, a. 834, 485) and the Chronicon Aquitanicum(MGH SS XVI, a. 830, 252); Ermentarius, Miracula I, Prologue; Miracula II, c. XI.

Author UpdateFor those of you curious to follow my new adventures on the book circuit in France, I have a few updates to share with you. First, I am ecstatic that I was the one author at my last show chosen to be featured in Ouest France:

I was also on the local radio with NovFM earlier this month. If you’d like to hear me speaking in French, you can access the clip here: Les Vikings S’Invitent A Noirmoutier. NovFM has invited me back for a longer form interview later this month.

I was also invited for an interview on RCF Radio. We recorded this past week, and the show will air in September:

September is shaping up to be an exceptionally busy month. I have a show in Dompierre-sur-Yon on the first weekend, a show at the Châteaux de Roiffé the next, Le Salon de Noirmoutier on the third weekend of the month, and finally a book fair at the Château de la Flocellière on the last weekend in September. You read that right—two of my shows are going to be in CASTLES. How cool is that??

Bref, things are going well. Thank you to everyone who is following my journey and has read my books, and if you support what I’m doing and want to help out, consider purchasing a premium subscription on Substack. Every one goes a long way to help keep this dream of mine alive! Thank you 🙏

And, as always…Buy my novels!

August 31, 2025

Les Vikings à Bouin : le deuxième raid le plus ancien en France (prétendument)

The Viking Raid on Bouin, 820, in the style of Peter Nicolai Arbo. Image by Dall-E.

The Viking Raid on Bouin, 820, in the style of Peter Nicolai Arbo. Image by Dall-E.La semaine dernière, j’ai écrit au sujet du prétendu raid viking contre Noirmoutier en 799, un événement débattu par les chercheurs mais central pour comprendre les débuts de la pression scandinave sur l’Empire carolingien. Cette semaine, tournons-nous vers un autre raid précoce : l’attaque contre Bouin. Les sources ne s’accordent pas sur la date exacte — certains parlent de 813, d’autres de 820 — mais dans tous les cas, l’événement éclaire la présence des Vikings en Aquitaine au début du IXe siècle. Avec d’autres indices épars, il suggère que les Scandinaves ont peut-être été plus actifs sur la côte atlantique sous Charlemagne et Louis le Pieux que ne le laissent entendre les maigres traces écrites conservées.

Une île disparueAujourd’hui, si vous partez de Nantes en direction de Noirmoutier, vous traverserez de vastes terres gagnées sur la mer, des champs plats ponctués de marais salants et d’oiseaux. Une route file droit vers l’île de Noirmoutier, célèbre pour ses plages, son sel et ses pommes de terre. Mais en chemin, vous passez par Bouin, une petite ville tranquille qui semble enclavée. Difficile d’imaginer qu’au début du IXe siècle, Bouin était entourée par la mer, et qu’elle fut l’une des premières communautés de France à ressentir le choc des raids vikings.

Au IXe siècle, Bouin se trouvait dans la baie de Bourgneuf, une île basse face à Noirmoutier. Toutes deux faisaient partie d’un paysage maritime dominé par les chenaux, les marais et la production de sel. Pour des raiders scandinaves sondant les côtes franques, Bouin et Noirmoutier étaient des cibles tentantes : riches, accessibles par bateau, et faiblement défendues.

Depuis, la géographie a changé. À partir du XVIIe siècle, des ingénieurs hollandais asséchèrent les marais du Marais breton-vendéen, érigeant digues et polders qui rattachèrent les îles au continent. Aujourd’hui, Bouin n’est plus une île, mais une bourgade sur la route de Noirmoutier. À l’époque viking, pourtant, elle était ceinturée par les eaux, ses marais salants et ses réserves de poisson et de bétail représentant une proie idéale pour des hommes en drakkar.

813 ou 820 ?Alors, quand les Vikings frappèrent-ils Bouin ? Ici, les sources divergent. Certains récits secondaires donnent 813, mais la preuve la plus sûre concerne 820.

Les Annales royales franques (Annales Einhardi), rédigées peu après les faits, rapportent qu’en 820 une flotte viking, après des raids infructueux en Flandre et à l’embouchure de la Seine, descendit vers l’Aquitaine. Là, ils « dévastèrent complètement un vicus appelé Bundium [Bouin] et rentrèrent chez eux avec un immense butin. »

Mais même si l’attaque que nous pouvons dater avec certitude eut lieu en 820, les indices suggèrent que Bouin et ses voisins furent harcelés bien avant.

« À cause des incursions fréquentes »Un an plus tôt, en 819, l’empereur Louis le Pieux émit un diplôme royal pour l’abbé Arnulf de Noirmoutier. Celui-ci autorisait la fondation d’un monastère satellite à Déas (aujourd’hui Saint-Philibert-de-Grand-Lieu), plus à l’intérieur des terres. La raison est explicite : il était nécessaire « à cause des incursions des barbares qui ravagent fréquemment le monastère de Noirmoutier. »

Ce n’est pas une plainte de moine rédigée des années plus tard, mais bien un document administratif ferme (ah, l’administration française !). Avant même la mention de 820 dans les annales, les moines de Saint-Philibert subissaient déjà une pression constante et durent déplacer leur communauté à l’intérieur des terres pour survivre. Le raid de Bouin en 820 ne fut donc pas un incident isolé, mais une étape d’un harcèlement répété dans l’estuaire ligérien.

Charlemagne et les hommes du NordLes signes de cette pression remontent encore plus loin. Éginhard, le biographe de Charlemagne, rapporte dans sa Vie de Charlemagne que l’empereur avait organisé des défenses côtières contre les hommes du Nord, comme il l’avait fait contre les raids musulmans au sud. Même si Éginhard reste avare de détails, il montre que la menace maritime était déjà reconnue du temps de Charlemagne.

L’anecdote la plus célèbre vient toutefois de Notker le Bègue, écrivant plus tard au IXe siècle. Il raconte que Charlemagne, dans une villa du littoral de la Gaule narbonnaise, reçut la nouvelle de la présence de navires nordiques au large. L’empereur se leva de table, regarda par la fenêtre, et vit les bateaux fuir « avec une rapidité merveilleuse ». Les Francs ne purent les rattraper — leurs navires étaient trop rapides. Charlemagne pleura, disant qu’il avait « le cœur malade », non par crainte pour lui-même, mais parce qu’il prévoyait les destructions que ces ennemis feraient subir à ses descendants.

Le récit de Notker, considéré comme apocryphe par la plupart des historiens, est teinté de rétrospective et de leçon morale. Mais cette scène saisit une vérité : la mémoire de navires vikings sur la côte aquitaine existait déjà du temps de Charlemagne, et même le grand empereur ne pouvait les arrêter.

Pourquoi Bouin ? L’hypothèse du selPourquoi les Vikings s’acharnèrent-ils sur ces îles en particulier ? La réponse se trouve sans doute dans la géographie et le commerce.

Noirmoutier et Bouin étaient des îles productrices de sel. Or, le sel était l’agent de conservation indispensable du monde médiéval, et il aurait pris une importance croissante au début du IXe siècle avec l’essor de la pêche au hareng dans la Baltique. Selon ma théorie, les marchands scandinaves avaient besoin de grandes quantités de sel pour conserver le poisson destiné à l’exportation vers les marchés de l’Est. Si l’on prend au sérieux le diplôme de 819, qui parle d’« incursions fréquentes et persistantes », alors il suggère que les Vikings visaient une ressource essentielle pour eux.

C’est le cœur de ce que j’ai appelé l’hypothèse du sel : l’acharnement des Vikings sur des lieux comme Noirmoutier et Bouin s’expliquerait en partie par le besoin d’un approvisionnement sûr en sel pour le commerce.

Dans cette perspective, le raid de Bouin en 820 témoigne d’une demande structurelle qui a alimenté l’activité viking plusieurs décennies avant les grandes campagnes fluviales des années 840.

Ce que l’on sait… et ce que l’on ignoreComme souvent avec l’histoire des débuts de l’ère viking, le tableau reste frustrant d’incomplétude. Les annales nous donnent quelques points fixes, mais elles sont laconiques et parfois contradictoires. Les chartes monastiques et les anecdotes comblent certaines lacunes mais sont marquées par leurs agendas. Nous pouvons affirmer avec certitude que Bouin fut attaqué en 820, que Noirmoutier subit des raids répétés auparavant, et que Charlemagne mit en place des défenses en réaction à ces menaces vers la fin de son règne (des mesures que j’ai abordées dans l’épisode précédent).

Ce que nous ne pouvons pas dire, c’est combien d’autres raids sont passés sous silence, ou comment les communautés locales vécurent la pression au fil des années. Pour chaque mention conservée, il a pu y avoir plusieurs étés de tension qui n’ont laissé aucune trace écrite.

ConclusionL’attaque de Bouin peut sembler une note de bas de page comparée au spectaculaire sac de Nantes en 843. Pourtant, elle mérite l’attention car elle ancre la toute première phase de l’activité viking sur le littoral atlantique franc. C’est la deuxième étape d’une progression implacable des raids en France de l’Ouest qui allait durer plus d’un siècle.

La semaine prochaine, nous plongerons dans les années 820, une décennie qui révèle à quel point les moines de Noirmoutier étaient sous pression. Les chartes royales de cette période laissent entrevoir l’importance économique de leur sel et les mesures extraordinaires qu’ils prirent pour se protéger des incursions vikings.

Et, comme toujours…Achetez mes romans ! (en Français)