C.J. Adrien's Blog, page 4

April 28, 2025

Did the Carolingians Really Embargo Trade with the Vikings?

When we think of early Viking raids, we imagine raw violence crashing against the shores of a wealthy and unsuspecting Europe. But in reality, the first Viking attacks unfolded against growing economic hostility — a slow, deliberate tightening of trade access by the Carolingian Empire. The evidence shows a clear progression, not through one sweeping decree, but through decades of increasingly restrictive policies that pushed outsiders to the margins of Frankish economic life.

The first signs of tension appear in the Capitulary of Herstal (779), issued under Charlemagne. Rather than targeting foreign trade directly, this document focused on internal matters: regulating tithes, upholding moral behavior, and standardizing justice. There is no mention of restricting trade with pagans or foreigners. However, around the same time, the lesser-known Capitulary of Nijmegen (c. 779–782) introduced the requirement that foreign merchants obtain warrants and submit to tolls (telonea) at royal markets. These measures suggest early attempts to supervise and constrain foreign access to the Carolingian economy.

By the time of the Capitulary of Frankfurt (794), imperial concern with economic control had sharpened. New rules governed coinage purity, weights, and merchant protections. Jewish merchants, critical intermediaries in international trade, received special attention and measures, indicating that long-distance commerce was increasingly centralized under royal oversight. Yet even here, there was no explicit embargo; the Carolingians sought control, not exclusion.

That changed in the early ninth century. The Capitulary of Diedenhofen (805) ordered that foreign merchants could only enter the empire through specific ports, where royal officials could inspect and tax them. This effectively erected economic checkpoints at the empire’s frontiers. While trade was not outlawed, it became significantly harder for outsiders, including Scandinavian traders, to move goods inland or operate freely along the Rhine and Seine.

The trend continued under Louis the Pious. The Capitulary of Aachen (817) reaffirmed and expanded earlier restrictions, imposing severe penalties on anyone caught selling arms or horses to pagans. The military logic behind these measures is obvious, but they also constricted Norse access to the tools and goods they needed to integrate peacefully into Carolingian markets.

Historians like Michael McCormick (Origins of the European Economy) have shown that the Carolingians did not seek to eliminate trade, but rather to control it tightly to consolidate royal authority. By regulating ports, markets, coinage, and merchant activity, the Carolingian court aimed to channel commerce through official avenues that reinforced imperial power. Archaeological evidence from sites like Dorestad and Quentovic reveals that foreign trade persisted well into the ninth century under centralized and supervised conditions. Christian Cooijmans (Monuments of Piracy) has further argued that the mounting restrictions, combined with local enforcement and the growing perception of outsiders as threats, made peaceful trade difficult for early Viking groups.

Yet even as the Carolingians sought to restrict and control access to their markets, circumstances eventually forced a more pragmatic approach. By the mid-ninth century, Frankish rulers were granting formal charters to Viking groups to establish regulated markets of their own. One notable example is the Viking settlement granted a trading charter on the island of Betia, near Nantes, around 850. Rather than expelling Norse traders entirely, the Carolingians shifted toward selectively legalizing their presence — a striking reversal that underscores the complexity of early medieval economic policies.

Rather than a sudden embargo, the Carolingian world erected a slow, uneven wall of economic hostility. And when the doors to legitimate commerce began to close, it may have seemed natural for some Scandinavian merchants to take by force what was no longer available by negotiation.

If you found this glimpse into the Carolingian world interesting, I'd love to hear your thoughts! Why do you think efforts to control trade so often lead to conflict? Were the Vikings simply responding to a closed door, or would they have raided anyway?

Share your thoughts in the comments — I'm always eager to hear your take on how history unfolds.

Works CitedCapitulary of Herstal (779), in Monumenta Germaniae Historica Capitularia Regum Francorum, vol. 1, ed. Alfred Boretius (Hanover: Hahn, 1883), 53–58. Link

Capitulary of Nijmegen (c. 779–782), in Monumenta Germaniae Historica Capitularia Regum Francorum, vol. 1, ed. Alfred Boretius (Hanover: Hahn, 1883), 86–88. Link

Capitulary of Frankfurt (794), in Monumenta Germaniae Historica Capitularia Regum Francorum, vol. 1, ed. Alfred Boretius (Hanover: Hahn, 1883), 100–111. Link

Capitulary of Diedenhofen (805), in Monumenta Germaniae Historica Capitularia Regum Francorum, vol. 1, ed. Alfred Boretius (Hanover: Hahn, 1883), 127–129. Link

Capitulary of Aachen (817), in Monumenta Germaniae Historica Capitularia Regum Francorum, vol. 1, ed. Alfred Boretius (Hanover: Hahn, 1883), 253–265. Link

McCormick, Michael. Origins of the European Economy: Communications and Commerce, A.D. 300–900. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

Cooijmans, Christian. Monuments of Piracy: Understanding the Viking World through its Raiding Practices. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2024.

P.S. Enjoying these deep dives into Viking and Carolingian history? I share even more research notes, early access chapters, and bonus articles for my paid subscribers. If you'd like to support my work — and dive deeper — you can join here.

April 24, 2025

It’s the [Viking] Economy, Stupid!

In 1992, James Carville, political strategist for Bill Clinton, famously boiled down the campaign’s messaging to a single phrase: “It’s the economy, stupid.” It worked because it cut through the noise to address what everyone really cared about—economic survival. Turns out, the Vikings weren’t much different.

While writing In the Shadow of the Beast, the second book in my Hasting saga, I deliberately slowed things down to emphasize the economic realities of the Viking Age. Gone were the raids and flaming monasteries of book one. This was the after. The messy, uncertain next step of a fledgling chieftain trying to build an economically viable empire (or business) in a faraway land.

A reviewer recently criticized the book with this gem:

“Not so much Hasting the Scourge of the Loire, more Hasting the inept salt farmer.”

I didn’t laugh. I jumped for joy.

They meant it as a knock, but to me, it meant they got it, with flying colors. That line captured the entire heart of the book: it’s about what happens when the sword is sheathed and a leader has to trade blood for bread. And yes—Hasting is an inept salt farmer. That’s the point.

In the novel, he tries to build wealth by controlling a vital resource and trade route. But he fails. He tries to enslave workers to operate his salt mashes and fails again. Then, he has to call on an old friend to help, dragging him into more local politics than he ever wanted. I’ll spare the spoilers, but let’s say the cost of survival isn’t always paid in silver or lives, but in humility.

When the Vikings raided Noirmoutier in 799, it was a salt-producing island and an essential node in the Carolingian economy. After the monks abandoned the island, salt production increased. Someone had to be operating the marshes.

Michael McCormick, one of the foremost scholars of the Carolingian economy, notes in a 2001 article that ‘salt and bread were basic to life and trade in the Carolingian world.’ This assertion underscores the significance of salt as a driving force in economic and political developments during that era. McCormick's research supports the notion that the increase in salt production and exports from Noirmoutier following the monks' departure was not coincidental. The Carolingian administration's continued receipt of salt from the island, and in greater quantities, suggests that another organized group had taken over operations. This aligns with the portrayal of Hasting in my narrative, who, recognizing the island's economic value, manages its salt production. Such a scenario is consistent with the broader historical pattern of Vikings integrating into local economies when profitable opportunities presented themselves.

This idea of Viking economic intent isn’t speculative. In Viking Market Kingdoms, historian Tom Horne argues that Viking expansion in the British Isles wasn’t random raiding but strategic occupation of key trade and production sites. He describes how Norse leaders deliberately seized control of “market nodes”—river mouths, harbor towns, salt-producing islands, and overland junctions—not to dominate vast territories, but to control the flow of goods and wealth. These weren’t warlords building kingdoms in the traditional sense—they were entrepreneurs shaping proto-commercial empires. That framework supports I wrote Hasting’s struggle in Book 2: not as a failure of leadership, but as a rough, very human attempt to do precisely what real Viking leaders did: to build an economy, and with it, a legacy.

Christian Cooijmans, in Monarchs and Hydrarchs, builds on the idea of Vikings as strategic occupiers of economic nodes by reframing their leadership model entirely. He argues that Viking warlords weren’t kings in the traditional territorial sense, but monarchs of mobility, ruling over ships, warriors, and what he calls floating capital. Their power wasn’t tied to the land they held, but to their ability to extract wealth, forge alliances, and command loyalty through opportunity. That concept profoundly shaped how I wrote Hasting’s arc in In the Shadow of the Beast. His salt farming venture was his first attempt to shift from raider to regional economic actor and stake a claim in a critical resource node like Noirmoutier.

But unlike the seasoned leaders in Cooijmans' analysis, Hasting fails because he’s one of the first to try it and is woefully inexperienced. He can fight like the best, but to run a salt farm? It’s like putting your berserkers in charge of logistics. Chaos was inevitable. What I believe makes the book compelling is that I give readers a front row seat to the emerging Viking playbook that would make them successful for over 300 years, and an intimate look at one of the men who wrote it.

So yes, I slowed down Book 2 on purpose. My editor even warned me about it. “This middle part’s a bit quiet,” he said. But I stuck with it because it matters. The trade, the failures, the attempt to build something, including himself—that’s the real bridge to The Kings of the Sea.

And to be clear, In the Shadow of the Beast isn’t all planning and politicking. It starts with the death of a king, includes a holmgang, and ends with bloody conflict against the Franks. There’s plenty of action. But I wanted readers to feel the weight of what came between as Hasting walked the path of his destiny to become one of the most notorious Vikings of them all.

If you came for carnage, you’ll get it—just not on every page. If you came for a historically grounded story about what it meant to be a Viking trying to hold territory, you’ll appreciate the salty bits.

And to the reviewer who gave me that glorious line: thank you. Hasting was an inept salt farmer. That’s exactly what I wanted him to be.

Now I want to hear from you—what do you think? Does a Viking saga need nonstop action, or is there value in showing what it took to actually build something in the chaos of the 9th century? Hit reply or leave a comment. I’m curious where you land.

April 23, 2025

When Vikings Saved Lives: How a DNA Project Uncovered a Hidden Health Crisis

Photo of Shetland by Ronnie Robertson - Gulberwick IMG_3157, CC BY-SA 2.0

Photo of Shetland by Ronnie Robertson - Gulberwick IMG_3157, CC BY-SA 2.0In a remote corner of Scotland’s northern isles, an ambitious genetics project set out to explore Viking ancestry. What it uncovered may have saved several lives.

The Viking Genes Project, led by the University of Edinburgh, began as a way to explore how Norse ancestry influenced the gene pool of Shetlanders and Orcadians—two island populations with deep Viking roots. But while collecting DNA data, researchers stumbled upon something unexpected: multiple carriers of a rare BRCA2 gene variant (c.517-2A>G), concentrated among people with ancestry from Whalsay, Shetland.

This particular mutation significantly increases the risk of breast, ovarian, and prostate cancers. For one participant, the discovery of this variant during the study led to early intervention and treatment—a life potentially saved not by modern medicine alone, but by an investigation into the genetic echo of the Viking Age.

As Professor Jim Wilson, one of the study’s lead authors, explains:

“In this small and genetically distinct population, we’re seeing drifted variants that have become relatively common. By identifying these founder mutations, we’re not just learning about history—we’re creating real opportunities for preventative healthcare in these communities.”

The study, published in the European Journal of Human Genetics, found that over 90% of pathogenic BRCA alleles in the Northern Isles could be traced to just two founder mutations. This strongly suggests a shared genetic legacy dating back over 200 years, likely tied to small, interrelated communities descended from Norse settlers. Thanks to this research, the local health board is now exploring population-wide genetic screening in the Isles—a proactive step that could prevent countless future cancer cases.

My TakePeople often ask me, “Why study the Viking Age?” The implication, of course, is that it's a dusty corner of history best left to academics and cosplay enthusiasts. But this is one more powerful answer to that question. When we study the past, we don’t just look backward—we often find ourselves peering into the future.

Just as studying the cosmos has yielded innovations in GPS, weather forecasting, computers, electronics, and even the cameras in our smartphones, studying the past can transform modern life in unexpected ways.

I recently wrote about a study in Sweden that used cutting-edge CT scanners to examine the teeth and skulls of Viking-era remains. The scans revealed not only detailed information about Viking dental hygiene and health (spoiler: it wasn’t great) but also highlighted how the testing of medical imaging tools on ancient remains could drive innovation in diagnostic technology. When we push the boundaries of exploring history, we also expand the limits of what science and medicine can do.

The takeaway is simple: when we push the boundaries of how we explore the past, we also expand what’s possible in the present.

This is why I believe so strongly in interdisciplinary research. Genetics, archaeology, radiology, epidemiology—when these disciplines collide over questions about the past, the ripple effects can change modern lives, and even save them. They already have.

So here’s to the Vikings—bringers of fire, lore, and, now, preventative cancer care. Let’s keep pushing those boundaries.

ReferencesWilson, James F., et al. “Two Founder Variants Account for over 90% of Pathogenic BRCA Alleles in the Orkney and Shetland Isles in Scotland.” European Journal of Human Genetics, April 2025. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41431-024-01704-w.

Devlin, Kate. “How a Viking DNA Study May Save the Lives of Shetland Islanders.” The Times, April 9, 2025. https://www.thetimes.com/uk/scotland/article/how-a-viking-dna-study-may-save-the-lives-of-shetland-islanders-0s0p7mbkq.

And don’t forget to buy my books (If you haven’t already):

April 22, 2025

Trade or Die: A Very Viking Vicissitude

Pre-Viking Age Scandinavians trading whetstones, in the style of Peter Nicolai Arbo (generated by AI)

Pre-Viking Age Scandinavians trading whetstones, in the style of Peter Nicolai Arbo (generated by AI)When Alcuin of York lamented in his letter to Higbald that "the pagans have desecrated God's sanctuary" and described the North Sea crossing as "a voyage not thought possible," he framed the Viking raid on Lindisfarne as a terrifying, unprecedented breach. It’s a line that helped define the popular imagination of the Viking Age: sudden, savage, and foreign. But Alcuin was wrong.

A recent geological study of eighth-century whetstones excavated in Ribe—Denmark’s oldest town—tells a very different story. These stones, quarried in the rugged mountains of Trøndelag, Norway, arrived south in massive quantities well before the Viking raids began. The whetstones were economic breadcrumbs and tangible proof of extensive trade networks stretching from Arctic Scandinavia to the southern North Sea decades before the first recorded raid. Far from being isolated warriors who burst onto the scene in a storm of steel, early Scandinavians appear to have already been embedded in the world they would later terrorize.

This blog article is not another attempt to pin down what started the Viking Age—I’ve written on that before ad nauseum—but rather, a closer look at the strange and subtle shift from trade to raid, as told through a simple and surprisingly informative object: the whetstone.

Whetstones as Clues to Early TradeIn the mid-700s, Ribe was bustling. Archaeological digs uncovered over 1,800 fragments of whetstones used to sharpen everything from knives to needles. Most came from quarries in central Norway, such as Mostadmarka and Eidsborg, located 1,100 kilometers away by sea. This level of transport wasn’t incidental. It was industrial. The trade scale suggests coordinated efforts, long-distance sailing skill, and peaceful exchange.

Using petrographic and geochemical analysis, researchers matched the Ribe whetstones to their Norwegian origins with high confidence. Most were made of a distinctive fine-grained schist found in the Mostadmarka region, a durable, effective, and valuable material. The volume and consistency of these finds point to structured trade routes operating decades before the Viking Age officially began.

These stones are economic indicators. Their presence in Ribe reveals the direction of trade and its regularity and scale. They tell a story of a pre-Viking Age world in which Scandinavians were already seafarers and merchants and well-connected to the British Isles and the Frankish world.

Alcuin and the Myth of the Unthinkable VoyageEnter Alcuin, whose words after the 793 Lindisfarne raid have echoed for over a thousand years. "A voyage not thought possible," he wrote. Yet that voyage had been happening for at least a century, putting the entry in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle for the year 789, describing an incident in which the Vikings killed the king's reeve at the port of Portland, demonstrating an earlier contact with Vikings than Lindisfarne in the textual evidence.

The image of the Vikings as sudden intruders belies the evidence. Scandinavians may have visited Anglo-Saxon, Frisian, and Frankish markets long before the raids began. Their trade routes—used by peaceful merchants in the 700s—likely became the highways of the Viking raids. I’ve written about how they used existing trade routes in my article on the Vikings and Salt.

The whetstone study is a stark rebuttal to the Alcuinian trope. Long-distance connections weren’t just possible; they were routine. The transition from peaceful exchange to violent incursion didn’t require a technological breakthrough or a newfound maritime skill—it needed a shift in motive.

From Trade to Raid: The VicissitudeHere lies the vicissitude: sometime between 780 and 830, the trade that linked Norway to Denmark, the Channel, and beyond began to unravel. Why? Scholars are still debating.

The authors of the whetstone study suggest one plausible cause: the consolidation of royal power in Scandinavia. As kings secured their hold over coastal territories, they cracked down on internal raiding. Once able to enrich themselves by preying on neighbors, Viking crews suddenly found themselves unwelcome at home. Meanwhile, the newly peaceful kingdoms protected trade networks and favored their merchants.

Faced with exclusion, some ship commanders may have turned their attention outward. The routes they once used for trade became opportunities for raiding, and the tools of exchange became tools of war.

Of course, this is only one strand in a tangled web of explanations. Other scholars point to social pressures, gender imbalance, political exile, climate stress, or the influx of Islamic silver. I explore these ideas in depth in an article on the causes of the Viking Age, but for now, it’s enough to say that the shift from trade to raid wasn’t sudden or total. It was an evolution—messy, complex, and very Viking.

Nantes and the Reversal: From Sack to CharterIn 843, the Vikings sacked the city of Nantes with characteristic ferocity. But what followed less than a decade later is one of the more striking illustrations of the vicissitudes of the Viking Age. Around 853, those same Scandinavians were granted a royal charter to establish a market on the island of Betia, just outside the city they had once destroyed.

In ten years, they transformed from destroyers to legally recognized market operators. This exemplifies how Viking interactions with the Frankish world were not static but fluid and often driven by mutual convenience. While this example from Nantes is especially stark, it reflects a broader pattern in other regions, where raiders became settlers, merchants, or mercenaries as political and economic tides shifted.

Then they shifted again, and in 882, a Viking fleet sailed up the Loire and sacked the city a second time.

The Real Viking Superpower: AdaptabilityThe whetstone teaches us that Vikings traded before they raided. It teaches us that adaptability was their true edge. They shifted strategies based on opportunity. They navigated the seas and the complexities of politics, economics, and culture.

The same hands that once bartered whetstones would later brandish swords and then extend them in peace, only to brandish swords again. That, in the end, is the most Viking vicissitude of all.

Article citation:

Baug, Irene, Dagfinn Skre, Tom Heldal, and Øystein J. Jansen. “The Beginning of the Viking Age in the West.” Journal of Maritime Archaeology 14, no. 1 (2019): 43–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11457-018-9221-3.

This Substack is reader-supported. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Don’t forget to buy my books (if you haven’t already)!

April 21, 2025

France: The Viking Obsession You Didn’t See Coming

When we think of Viking fandom today, three places usually come to mind: Scandinavia, where the Vikings originated; the British Isles, which bore the brunt of their raids; and the United States, where Scandinavian immigrants have passed on their heritage through generations of Norse pride. But one country rarely mentioned—yet perhaps more enthusiastic than all the rest—is France.

It might come as a surprise, but France is home to one of the world's most vibrant, widespread, and creative Viking enthusiast communities. And it's not just confined to Normandy, the historically “Northman”-named region ceded to Viking leader Rollo in the 10th century. The Viking revival in France is happening in coastal towns and inland cities, from grassroots workshops to theatrical concert halls.

French Viking ship building is booming.Take, for instance, Les Sables-d’Olonne, a seaside town on the Atlantic coast. There, a group of volunteers led by artisan Wilfried Desfontaines is building a full-scale replica of a Viking ship named Olaf d’Olonne. It’s a community-driven project built using traditional methods, and Wilfried’s not new to this—he previously built Argwikor, a half-scale Skuldelev 3 replica, with the help of his sons.

He’s not alone. In Toulouse, the collective Les Bátar is constructing the ORKAN, a 12-meter drakkar that blends Viking design with modern, eco-conscious materials. Their long-term goal? To sail it to New York.

Meanwhile, in Normandy, the Dreknor, a replica of the Gokstad ship, has been sailing since the 1990s. In Honfleur, a major reconstruction project is underway to rebuild La Mora, the flagship of William the Conqueror. The Brittany region alone had at least three Viking ship projects launched in the 2010s, including L’Aigle d’Ogvaldr and Drakkar de l’Estran. While some are no longer active, they were part of a broader surge in Viking enthusiasm.

And the boats are only part of the story.

Historical parks are all the rage.Near Caen in Normandy, the Ornavik Historical Park has recreated an entire Viking village from the early 10th century, built using period tools and methods. Visitors can explore longhouses, watch blacksmiths at work, and speak with reenactors who live and breathe Viking-era life. It’s part living museum, part experimental archaeology, and it stands as one of the most ambitious projects of its kind in Europe.

Then there’s Le Puy du Fou, France’s most spectacular historical theme park, which features a jaw-dropping Viking stunt show complete with burning ships, theatrical raids, and full-scale combat choreography. It’s fantasy-meets-history on a blockbuster scale, and it's watched by millions each year. Across France, local festivals, historical fairs, and experimental archaeology programs continue to recreate Viking life, not for tourists but for the sheer joy of inhabiting the past.

French Viking historical reenactment is on the rise.The Idavoll website serves as the nerve center for Viking reenactment in France. This French-language hub lists 144 active reenactment groups nationwide—yes, 144! From full-costume warriors to craft specialists and ritual reenactors, the movement is thriving.

And what about that music?!Let’s not forget music. France is home to two of the most iconic Viking-themed bands in Europe: SKÁLD, whose haunting Old Norse chants have earned international acclaim, and Eihwar, whose primal, tribal beats conjure the spirit of the berserker.

France: The next place you should visit to nerd out on Vikings.So while the world looks north for modern Vikings, it might be time to glance further south. The French aren’t just watching from afar—they’re building longships, dressing the part, singing the songs, and reawakening a culture that once touched their shores. Quietly, passionately, France has become one of the Viking world’s most unexpected champions.

My novels: The Vikings in France in the early 9th Century.If traveling to France isn’t within the budget this year, you could still go there by diving into my historical fiction series about Viking Hasting and his exploits in France. Upgrade to a paid subscription to his publication, and you’ll receive the first three books in the series FREE (and support my work).

April 19, 2025

The Vikings: Even Their Poo is Interesting

In 1972, beneath the soon-to-be foundation of a Lloyds Bank in York, a construction worker spotted something unusual lodged in the dark, waterlogged earth. It was long, brown, and suspiciously… familiar. One can only imagine the first reaction—was it a prank? A sausage? Some forgotten chunk of industrial insulation?

Nope. It was exactly what it looked like: a turd. But not just any turd.

This specimen, later known as the Lloyds Bank Coprolite, turned out to be a fossilized Viking bowel movement, astonishingly well-preserved after 1,200 years in the muck. It measured over eight inches in length and two inches in width—a veritable history log. And believe it or not, this noble stool (along with other artifacts) halted construction. Archaeologists were brought in. Excavations began. Thus, the dig at Coppergate was born, uncovering some of Britain's most spectacular Viking remains.

The Lloyds Bank coprolite displayed at Jorvik Viking Museum. Photo by C.J. Adrien.

The Lloyds Bank coprolite displayed at Jorvik Viking Museum. Photo by C.J. Adrien.So yes. A Viking turd (along with other artifacts) literally stopped time—and a bulldozer—in its tracks.

What makes it even more fascinating is that this coprolite has become one of the world's most studied and oddly celebrated pieces of excrement. At one point, it was insured for hundreds of thousands of dollars.

In this article, we’ll dive—metaphorically, of course—into what this legendary log reveals about the Viking world. From their surprisingly parasite-rich diets, to their sanitation habits (or lack thereof), and even the failures of their colonies abroad, it turns out that Viking poo has quite a lot to say.

The Most Valuable Dump in HistoryLet’s get the obvious question out of the way: why is a fossilized Viking turd valuable?

Because it talks. Not literally (that would be terrifying), but scientifically. The Lloyds Bank Coprolite gives us a remarkable glimpse into the Viking diet and health. Analysis revealed that the man (yes, almost certainly a man—science can tell that too) who produced it had a diet heavy in meat and bread, but virtually no vegetables. He was also riddled with intestinal parasites, which suggests he ingested fecal matter, probably through contaminated water or poor hygiene. All told, it’s a relatively typical portrait of medieval gut health.

But what makes this specimen so exceptional is its state of preservation. Most human waste decomposes quickly. But this one had been buried in the anaerobic, oxygen-deprived muck of York, which preserved it like a relic. It’s so pristine you can practically count the sesame seeds.

This brings us to perhaps the strangest detail of all this.

The man who allegedly left us a piece of history. Photo by C.J. AdrienEnter the Paleoscatologists

The man who allegedly left us a piece of history. Photo by C.J. AdrienEnter the PaleoscatologistsYes, paleoscatology is a real field of study. It's the science of analyzing ancient feces. Somewhere, in the vast universe of academic careers, someone said, "I want to spend my life studying ancient turds." That’s a choice and a commitment.

You have to wonder how one ends up in paleoscatology. Was it a childhood dream? Did they lose a bet in grad school? Were all the dinosaur jobs taken?

I imagine a scene at the primary school teacher conferences.

Teacher: “So, Sam’s Dad, what do you do for a living?”

Paleoscatologist: “Let’s just say, my work is fairly grounded.”

All jokes aside, it’s a real and valuable discipline. Paleoscatologists are the unsung heroes of archaeology. Through ancient feces, they help us reconstruct diets, analyze parasite loads, and even trace trade goods. Seeds, bones, pollen, and fibers all pass through the human digestive system and can leave their signature in the stool like a time capsule.

Thanks to the tireless efforts of people with very strong stomachs, the Lloyds Bank Coprolite has become the poster child of paleoscatology.

Poo and Public Health: Lessons from the NorseBut poo doesn’t just tell us what individuals ate. It tells us how entire societies functioned or failed.

Take the Greenland Norse, for example. Viking settlers established a colony on Greenland’s southwestern coast around the 10th century. Harsh winters, fragile soils, and uneasy relations with the Inuit made life difficult, though not impossible. The Norse hung on for almost five centuries.

In Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed, Jared Diamond argues that their downfall was largely self-inflicted. He points to a cocktail of bad decisions: deforestation, overgrazing, refusal to adopt Inuit hunting techniques, and environmental degradation caused by misguided sanitation efforts.

Trying to replicate the waste management systems of mainland Scandinavia, the Greenland Norse dug cesspits. Greenland’s permafrost, however, prevented proper drainage, and during the summer thaws, waste seeped into the scarce freshwater sources. In short, they poisoned themselves.

It’s a potent reminder that sanitation isn't just a modern luxury, but often the dividing line between survival and extinction.

Crap, Context, and CivilizationIt’s easy to laugh at fossilized Viking turds. In fact, you should. But the Lloyds Bank Coprolite and its kin represent something profoundly important: the everyday, often-overlooked aspects of life that defined survival in the past.

Where you put waste, how you manage it, and what it contains can make or break a society. That’s as true today as it was in the Viking Age. And if future archaeologists ever dig through our trash heaps (or worse), they’ll likely say the same about us.

The Bottom LineIn conclusion, Viking poo is more than just a funny anecdote or a museum oddity. It’s a window into the past, one we never expected to open and didn’t want to smell.

So the next time you visit a museum and see a rock that looks suspiciously like a breakfast sausage, show some respect. You might be looking at one of the most critical finds in human history.

This Substack is reader-supported. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

And as always, check out my novels to explore the Viking world in a more…colorful way:

April 16, 2025

The Ballateare Burial: A Viking Mystery Unearthed

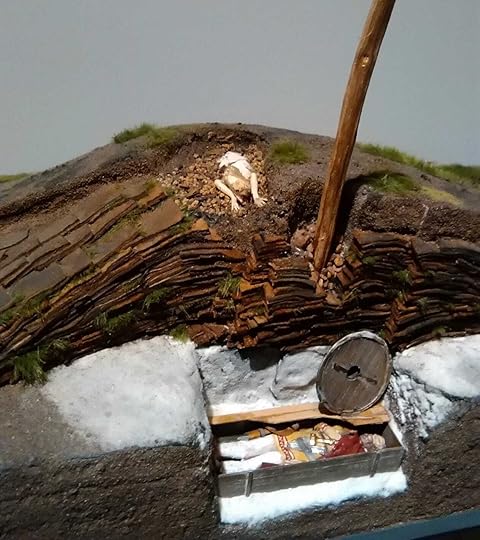

A Peter Nicolai Arbo style rendition of the “creation” of the final layer of the Ballateare Burial.

A Peter Nicolai Arbo style rendition of the “creation” of the final layer of the Ballateare Burial.On the Isle of Man, archaeologists uncovered one of the most disturbing Viking burials in the British Isles. At Ballateare, a team led by Gerhard Bersu excavated a mound that held the remains of a richly armed male warrior. He lay with his sword, grave goods, and the honors expected of a Norse chieftain.

But someone else shared his grave.

A sword found at Ballateare.

A sword found at Ballateare.Above him, buried without offerings, lay the body of a woman. Someone struck her skull with such force that it crushed the bone while her brain tissue remained intact, proving the fatal blow landed while she still lived, or moments after. Yet her cause of death tells only part of the story. Her body position created the real mystery.

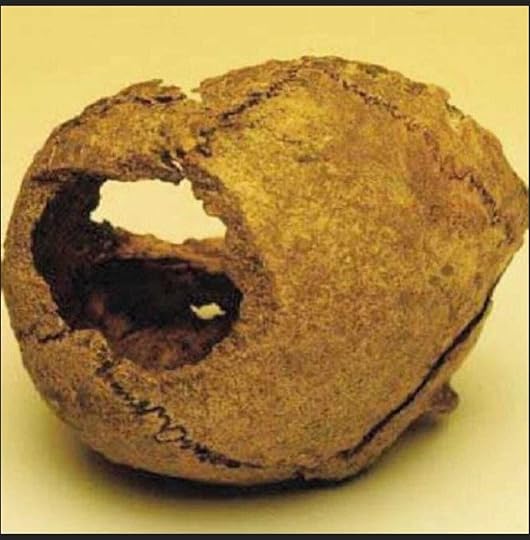

The skull of the woman buried in the upper layers.

The skull of the woman buried in the upper layers.She lay on her back, her legs extended, but her arms reached straight upward at ninety degrees. Her posture defied gravity. It defied explanation. Dr. Clare Downham recently revisited the case, sharing her observations on Bluesky. She asked the questions that keep scholars awake: Why did her body remain in this position? What happened in those final moments?

Some believe her arms froze in rigor mortis. That process can begin within two hours of death and last for more than a day. If someone tied her upright—perhaps to a central post—rigor mortis may have locked her arms in place. If they buried her soon after cutting her down, her body may have kept that posture.

Sections through the mound, showing the woman’s location in the upper layer.

Sections through the mound, showing the woman’s location in the upper layer.Others suggest a darker possibility. If her killers left her body exposed, gases from decomposition might have forced her arms into that unnatural position. Dr. Downham noted another grim detail: the layer of cremated animal bone that covered her may have failed to conceal her fully. Her hands might have reached through the ash, grasping toward the final layers of turf that sealed the mound.

This image chills the blood.

A cross-section of the mound setup, displayed at the Manx National Heritage Museum.

A cross-section of the mound setup, displayed at the Manx National Heritage Museum.The excavators found no sign of a second burial event. No tools or treasures marked her resting place. While the warrior received honor and wealth in death, she received nothing. Many interpret this woman as a ritual sacrifice. Perhaps someone killed her to accompany the man in the afterlife. Perhaps her death served another purpose—punishment, revenge, or a display of control.

Dr. Downham raised yet another idea. The wound to her skull may have resulted from a botched execution. The strike landed on the top of her head, not at the base where executioners aim to kill quickly. Did she resist? Did someone fumble the blow? Or did the killer strike after death as part of a ritual?

The Ballateare mound offers no answers. It gives us fragments of a story frozen in time: violence, ritual, and mystery.

Now I ask you: What happened on that hill? Why did her arms reach upward from the earth?

Share your theory in the comments. I want to hear your take!

April 14, 2025

⚔️ Viking Spring Recruitment – 20% Off Paid Subscriptions Now Through May 4th!

Fellow traveler,

The longships are ready, and the Viking Spring Recruitment has begun—with a special offer:

🔥 Get 20% off all paid subscriptions now through May 4th 🔥

If you’ve enjoyed my books, my articles, and the research behind the sagas, now’s the time to join the crew.

Paid subscribers get:

📚 A free download of The Saga of Hasting the Avenger box set (Books 1–3)

🧠 Full access to my research and bibliography—the historical foundations of the series

🙏 My eternal gratitude for helping keep this work independent and thriving

Want to go even further?

Join the Raving Fans or Patrons tiers and receive:

A signed hardcover of The Fell Deeds of Fate

Paperback editions of the first three Hasting books

A personal thank-you from me for being part of this journey

🛡️ Don’t miss out—the 20% discount ends May 4th

No, Vikings Didn't Drink from Skulls. What They Did Do Was Weirder.

Short on eggs this easter? Try painting a skull instead, like a Viking.

Short on eggs this easter? Try painting a skull instead, like a Viking.A new archaeological review published in Praehistorische Zeitschrift caught my attention this week. It catalogs 34 manipulated human skulls from 18 different Viking Age sites across Sweden and Denmark, all dating to between AD 750 and 1050—the heart of the Viking Age.

But these weren’t just ordinary burial finds. These were isolated skulls, often altered, sometimes prominently displayed, occasionally retrieved from older graves, and in several cases, deposited in wetlands.

In other words, something strange was going on.

Modern pop culture loves the idea of Vikings quaffing mead from the skulls of their enemies—a trope that appears everywhere from death metal lyrics to TV shows. It’s mostly poetic license, drawn from a mistranslation of Skaldic verse (they likely drank in honor of the slain, not from them).

But let’s be honest—they were still doing some seriously weird stuff with skulls.

Even if they weren’t tipping back blood-red brews from hollowed-out craniums, they were altering them (perhaps even decorating), hoisting them on palisades, tossing them in bogs, and digging them up to mark sacred spaces. If anything, reality might be stranger—and more complicated to explain—than fiction.

Heads Without BodiesThe study suggests that Viking Age Scandinavians had a complicated relationship with the human head. While decapitation itself was considered shameful and something reserved for slaves or criminals, there was something potent and magical about the head once removed from the body.

The skulls analyzed turned up in some unusual places:

At the edge of grave pits, suggesting funerary decapitations, possibly of slaves or attendants sacrificed to follow a chieftain into death.

On palisades around proto-urban settlements, like grim trophies or public warnings.

In wetlands and bogs, which, as we know from Iron Age ritual sites, were often associated with offerings to the gods.

Reburied or reused—including one example tied to the inauguration of an assembly platform, a ritual act that may have carried legal or spiritual significance.

Most intriguingly, there’s evidence that skulls were sometimes taken from older graves and manipulated (perhaps even decorated). Whether for magic, memory, or macabre ritual, we can only guess.

Why the Skull?The Old Norse literary tradition gives us a clue.

Despite the shame of decapitation, the head was seen as a vessel of power and knowledge. The god Óðinn carries around Mímir’s decapitated head, which continues to offer him counsel. This isn’t just a poetic invention. It reflects a deeper cultural motif: the head retains its essence. It’s sacred. Perhaps even dangerous. Oh my!

That might explain why skulls appear in boundary places, at the edge of graves, on city walls, or liminal spaces like bogs. These weren’t just corpses. They were symbols. Warnings. Offerings. Anchors to the divine.

Ultimately, we aren’t sure of their precise meaning and significance, but this new study, combined with literary sources, gives us a clue.

What About Norway?Interestingly, the study found no comparable skulls from Norway. The study authors note that it’s not because they didn’t exist but because soil chemistry in much of Norway is notoriously bad for bone preservation. So, we shouldn’t assume Norwegians were less inclined toward these practices. They just didn’t leave us much to dig up.

My TakeThis study offers intriguing new clues about Viking ritual behavior, but like much of what we uncover from the Viking Age, it raises more questions than it answers. We’re left with a pattern of activity—burials, displays, bog deposits, and reuse—but no clear explanation for what it all meant to the people who did it.

In short, we still don’t know what they were doing with all those skulls.

And maybe—just maybe—we should be cautious about asking.

This Substack is reader-supported. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

April 9, 2025

Did the Fall of the Roman Empire Cause the Viking Age?

For generations, the Viking Age has had a definitive start date: 793 AD, the year of the infamous raid on the monastery at Lindisfarne. But what if that moment was merely a symptom of a much deeper, longer historical process? In a recent episode of Vikingology, I sat down with Alex Harvey to explore a growing body of academic discourse that pushes the origins of Viking activity much farther back—potentially to the waning days of the Western Roman Empire.

In that conversation, we explored the idea that the social, economic, and environmental shifts at the end of the Roman period may have laid the groundwork for what would eventually be recognized as the Viking phenomenon. This includes the emergence of trade networks in the North Sea, the fragmentation of power structures across Europe, and long-term cultural exchanges between Scandinavia and the British Isles well before the first recorded raid.

This year, a newly published study in Nature added a fascinating layer to that theory. The research analyzed more than 1,500 ancient genomes and found that individuals with clear Scandinavian ancestry were present in Britain as early as the Roman era. This challenges the long-held assumption that Scandinavian migrations into Britain only began with Viking raids, suggesting an earlier, more gradual movement of peoples.

📄 Read the full study: Nature – Population genomics of post-Roman Britain

Of course, genetics alone can't tell us what those early Scandinavians were doing in Britain—whether they were traders, settlers, mercenaries, or something else entirely. However, their presence provides at least one indication that the Viking Age may have roots farther back than the 8th century. It lends weight to the argument that Scandinavian mobility and influence were part of a broader continuum rather than an explosion of violence and seafaring prowess.

This fits into a more longue-durée shift in how historians and archaeologists are beginning to view the early medieval period: not as a series of disconnected episodes but as overlapping waves of cultural and population change. The idea that there were “forgotten Vikings”—pre-793 Scandinavians shaping the cultural landscape of Britain—is gaining traction, and with it, a need to rethink the story we've long told about how the Viking Age began.

History is, as ever, messier than the textbooks suggest. But that makes it worth revisiting—especially when new science and old stories combine to reveal a bigger, more complex picture of the past.

This Substack is reader-supported. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.