C.J. Adrien's Blog, page 7

January 10, 2025

The Fell Deeds of Fate: Kirkus Calls It a "Richly Developed Epic Viking Adventure"!

I’m beyond excited to share some incredible news: The Fell Deeds of Fate has received a glowing review from Kirkus Reviews! For any author, having your work reviewed by Kirkus is a huge milestone. They’re renowned for their discerning and often critical reviews, so receiving such high praise is a true honor and affirmation of the hard work and dedication that went into creating this book.

Here’s what Kirkus had to say:

“In Adrien’s series-starting historical novel, an aging Viking goes on a journey to capture a great city—and to prove himself worthy by doing so.

Viking leader Hasting has retired to a comfortable life on a small island with his wife, Reifdis, but he’s still immature at heart; specifically, he’s still smarting that he never received the recognition he believed was his due for capturing Paris in the year 845. He’s certain he can be an honorable father to his newborn boy, but Reifdis, due to his drunken ways, has no such faith and divorces him. ‘Hasting, you are, as a result of this, commanded by the queen of this land to leave and never to return,’ says the local seer. Feeling cursed but driven to prove himself, he decides to lead a mission to capture Europe’s grandest yet most impregnable city, Istanbul (which the Vikings call Miklagard). It’s an audacious plan requiring a vast fleet, so he journeys through Europe to call on friends old and new, sailing around northern France, past what is now Denmark and Sweden, and then upriver to his target. Hasting was a real historical figure who effectively disappeared from the record for several years—a gap that Adrien has filled with this fictional but plausible adventure. The novel also includes historical details regarding ships, great halls, and much more. The lengthy historical notes following the narrative show Adrien’s dedication to accuracy. Hasting’s journey is regularly punctuated by battles, captures, and escapes, making for a staccato, episodic plot, and the protagonist reveals his backstory as the narrative progresses, including prior battles and triumphs; his memories of his first love with a woman named Asa; and his childhood in Christian Ireland. As a character, he’s impulsive, arrogant and aggressive, but also clever, loyal and jovial, making him easy to root for—particularly as he slowly learns that honor can’t be won by force. Still, Adrien skillfully crafts a satisfying resolution while teeing up the next series entry.

Richly developed fictional adventures of a real Viking on an epic journey through Europe.”

This review represents everything I set out to achieve with The Fell Deeds of Fate. Kirkus’ recognition of the rich historical details, the authenticity of Hasting’s journey, and the emotional depth of his character is a testament to the care and passion I poured into every page. Acknowledging my dedication to historical accuracy, paired with the adventure and drama of Hasting’s story, makes this review even more meaningful.

Receiving such high praise from Kirkus—a name synonymous with literary excellence—feels like a milestone in my journey as an author. Their review affirms that The Fell Deeds of Fate is a compelling story and a meaningful contribution to the world of historical fiction.

I couldn’t be more excited to share Hasting’s epic adventure with readers, and I’m thrilled that Kirkus sees it as the beginning of a journey worth taking. If you haven’t had a chance to pick up The Fell Deeds of Fate, I hope this inspires you to dive into the world of Vikings, honor, and epic quests. Thank you to all my readers and supporters for being part of this incredible adventure—there’s so much more to come!

Purchase a copy of The Fell Deeds of Fate below.

January 9, 2025

Swords, Sails, and Smallpox: Were the Vikings History's Original Superspreaders?

A 1200-year-old smallpox-infected Viking skeleton found in Öland, Sweden. Credit: The Swedish National Heritage Board

A 1200-year-old smallpox-infected Viking skeleton found in Öland, Sweden. Credit: The Swedish National Heritage BoardThe Viking Age (circa 793–1100 AD) conjures images of fierce warriors, swift longships, and legendary conquests. However, recent research suggests that the Norse may also have played an unexpected and sinister role in history: the spread of smallpox. Far beyond raiding and trading, the Vikings’ extensive travels may have helped disseminate one of the world's deadliest viruses, making them inadvertent superspreaders.

Unveiling the Smallpox ConnectionSmallpox, caused by the variola virus, has long been one of humanity's most devastating diseases, claiming millions of lives before its eradication in 1980. While its origins remain murky, a groundbreaking 2020 study published in Sciences shed new light on its ancient history. Researchers analyzed DNA extracted from Viking-age human remains in Scandinavia and found evidence of an extinct strain of the variola virus. This discovery pushed the known existence of smallpox back over 1,400 years, suggesting that the disease ravaged populations much earlier than previously thought.

Crucially, the study highlighted the Vikings’ potential role as vectors. With their extensive maritime networks spanning Europe, the Middle East, and North America, the Vikings could have acted as biological conduits, carrying the virus far and wide.

Superspreaders Across ContinentsThe Vikings were uniquely positioned to spread diseases like smallpox. Their voyages were not isolated raids but formed an intricate web of interaction. They interacted with diverse populations and ecosystems by establishing trade routes and settlements. As seen in their expeditions to Constantinople, the British Isles, and Greenland, the Vikings were adept at crossing geographical and cultural boundaries.

One compelling hypothesis is that the crowded and unsanitary conditions aboard Viking longships created the perfect breeding ground for viruses like smallpox. Although the Vikings were known to carry cats on their ships to control rat populations—as I explored in my article on Viking maritime practices—this effort to reduce pests may not have been sufficient to prevent the spread of human-borne pathogens. The close quarters and prolonged exposure during voyages could have accelerated disease transmission among the crew, turning a single infected individual into a super-spreader.

Methodology Behind the DiscoveryThe discovery of smallpox in the Viking Age remains a result of groundbreaking advances in ancient DNA analysis. Researchers extracted DNA from the teeth and bones of human remains buried in sites across Scandinavia. By focusing on well-preserved samples, scientists could identify genetic traces of the variola virus, confirming its presence in Viking populations.

This study's use of high-throughput sequencing technologies is remarkable. These technologies allowed researchers to reconstruct ancient viral genomes with unprecedented precision. This approach confirmed the existence of smallpox during the Viking Age and revealed that the strains present at the time differed from the modern variola virus eradicated in the 20th century. These ancient strains likely caused milder outbreaks but contributed to the disease's long history of human affliction.

The study also employed radiocarbon dating to establish a timeline for the remains, aligning the presence of smallpox with the height of Viking activity. By correlating these findings with historical accounts and archaeological evidence, researchers were able to hypothesize how the Vikings' extensive travel networks facilitated the spread of the virus.

The Middle East Connection: Raiders Turned TradersThe Vikings’ expeditions extended well into the Middle East, where they established trade routes along the rivers of modern-day Russia and engaged with the Byzantine and Abbasid empires. These interactions may have exposed them to pathogens circulating in the densely populated urban centers of the Middle East. Rather than introducing smallpox to the region, it’s more plausible that the Vikings contracted the virus there and brought it back to Europe.

The return journey—often involving prolonged stops at trading hubs like Kyiv or Novgorod—would have allowed the virus to spread. The Vikings’ dual roles as traders and raiders further increased their contact with varied populations, amplifying the disease’s reach.

Evidence from the GraveArchaeological discoveries support the theory of Viking-era smallpox transmission. The 2020 Science study found smallpox DNA in Viking-age skeletal remains from multiple locations, including Sweden, Norway, and Russia. These findings suggest that the disease was widespread among Norse populations and likely persisted over generations.

Further supporting this are historical accounts of disease outbreaks in medieval Europe. While records from the Viking Age are sparse, later chronicles, such as those from Anglo-Saxon England and Frankish Europe, describe plagues sweeping through regions frequented by the Norse. For example, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle mentions pestilence in the 9th century, when Viking raids and settlements were prevalent. Similarly, Frankish annals recount outbreaks in territories impacted by Norse incursions, suggesting a correlation between Viking activity and the spread of disease. It’s reasonable to infer that their mobility played a role in introducing or exacerbating these outbreaks.

The Superspreader FrameworkModern epidemiology offers a valuable lens for understanding how the Vikings may have functioned as superspreaders. Key characteristics of superspreaders include high mobility, extensive contact networks, and prolonged infectious periods—all traits that align with Viking lifestyles. Their longships carried not just warriors and goods but also invisible pathogens, making every raid or trade mission a potential vector for disease.

Mitigating Factors: Hygiene and CatsDespite their role in disease transmission, the Vikings were not oblivious to hygiene. Viking culture actively encouraged cleanliness. Historical sources, including Anglo-Saxon, Frankish, and Scandinavian accounts, describe Vikings bathing at least once a week—a practice notably more frequent than that of their southern European counterparts. Archaeological finds of daily life, including intricately designed grooming kits with combs, ear picks, and tweezers, further emphasize personal grooming. Current scholarship often regards the Norse as being as clean, if not cleaner, than other Europeans of the time. This commitment to hygiene may have been partially practical, as it could enhance social interactions and reduce lice and other parasitic infestations common in medieval societies.

As noted earlier, their use of cats on ships to control rats demonstrates a rudimentary understanding of pest management. This practice likely reduced the risk of rat-borne diseases like the bubonic plague, which spread via fleas. However, smallpox—a human-specific virus transmitted through respiratory droplets or direct contact—would not have been mitigated by such measures.

Lessons for TodayThe Viking example underscores the profound impact of human mobility on disease dynamics. Much like modern air travel enables the rapid global spread of pathogens, the Vikings’ maritime networks connected distant regions, facilitating the exchange of both goods and germs. Understanding their role as superspreaders provides valuable historical context for pandemics and highlights the interconnectedness of human societies.

Conclusion: The Legacy of Viking VoyagesWhile the Vikings are celebrated for their adventurous spirit and cultural contributions, their legacy also includes the unintended consequences of their mobility. The discovery of smallpox DNA in Viking-age remains challenges us to reconsider their historical impact, not just as conquerors and traders but also as carriers of one of history’s deadliest diseases.

When I first wrote In The Shadow of the Beast (Saga of Hasting the Avenger, Book 2), I wanted to explore the external adventures of Hasting and his crew and the unintended consequences of their far-reaching voyages. In the book, Hasting’s settlement is devastated by a plague they unwittingly bring back from distant lands, a narrative decision born from my curiosity about the hidden costs of exploration. Reading studies like the one that uncovered smallpox DNA in Viking-age remains validates this storytelling choice in a way I never expected. It’s fascinating—and sobering—how these historical findings align with the fictional world I created. The idea that Vikings could act as unwitting carriers of disease reinforces the complexity of their legacy, and it makes me reflect on how fiction can sometimes intuitively echo historical truths long before they’re fully uncovered. It’s a reminder of why I love weaving history and imagination together—there’s always more beneath the surface.

By exploring how the Vikings may have helped spread smallpox, we gain a deeper appreciation for the complex interplay between human activity and disease. Whether through their longships, trade routes, or interactions with Indigenous peoples, the Norse left an indelible mark on the world that extends beyond swords and sagas to the microscopic agents of history.

Here are citations for the genetic studies on smallpox and Vikings:

Smallpox in Viking DNA

Mühlemann, Barbara, et al. "Ancient Variola Virus Genomes Reveal the Origins and Evolution of Smallpox." Science, vol. 369, no. 6502, 2020, pp. 86–91.

DOI: 10.1126/science.aaw8974

This study identified ancient strains of smallpox in Viking-age human remains, suggesting the disease was widespread in their populations.

Press Coverage on Viking Smallpox

St. John’s College, Cambridge: "Vikings Had Smallpox and May Have Helped Spread the World’s Deadliest Virus." https://www.joh.cam.ac.uk/vikings-had-smallpox-and-may-have-helped-spread-worlds-deadliest-virus

ScienceDaily: "Smallpox May Have Plagued Humans Earlier Than Thought." https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2020/07/200723143733.htm

And as always, please buy my books, you filthy heathens!

January 8, 2025

Did Vikings Have a Pocahontas? An Obscure Study's Surprising Find

The Vikings were known for their extraordinary voyages, expanding their influence as far as Baghdad in the Middle East and Newfoundland in North America. Their adventurous spirit left behind a trail of raiding, trading, and genetic legacy. Given their prolificness as progenitors across Europe, one question has intrigued me for a number of years: did the Vikings intermix with Native Americans during their explorations of North America?

This question takes us deep into the annals of Viking history, from the Greenland Norse who attempted colonization in North America to a curious genetic study suggesting a possible intermingling of Viking and Native American ancestries. Let’s dive into the evidence and unravel this fascinating possibility.

Viking Voyages to North America: The Greenland NorseThe story of Viking exploration in North America begins with Erik the Red and the Greenland Norse. Exiled from Iceland for manslaughter, Erik settled in Greenland in 985 AD. Over the following centuries, Greenland became a hub for Norse exploration, with tales of fertile lands to the west sparking voyages to what we now know as North America.

Leif Erikson, Erik’s son, is credited with leading the first expedition to these new lands. The sagas describe their discovery of Helluland (likely Baffin Island), Markland (likely Labrador), and Vinland, a region rich in timber and wild grapes. Archaeological evidence, such as the Norse settlement at L’Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland, confirms the presence of Viking activity in North America around 1000 AD.

However, the sagas also recount tense relations between the Greenland Norse and the Native Americans, whom they called Skrælings. Initial trade between the two groups led to hostilities, with the Norse abandoning their settlements due to conflict and isolation. The sagas depict the Skrælings in a highly dehumanized light, often as subhuman adversaries. This attitude is exemplified in incidents where the Greenland Norse slaughtered Skrælings with impunity, such as the account of encountering sleeping Skrælings and killing them outright. These descriptions in the sagas highlight the likelihood of a hostile and dismissive relationship, which has long led historians to doubt significant intermixing between the two groups.

The Genetic Evidence: A Surprising DiscoveryFast forward to 2011, when a team led by Agnar Helgason of deCODE Genetics uncovered intriguing genetic evidence that may shed light on this historical mystery. Published in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology, their study identified a mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) lineage, haplogroup C1e, in over 80 living Icelanders. This lineage is distinct from the known European genetic pool and resembles haplogroups in Native American and East Asian populations.

Mitochondrial DNA, passed down through the maternal line, provides a unique lens into ancestry. The presence of C1e in Iceland suggests that a Native American woman might have been brought to Iceland by Norse explorers. Further genealogical analysis traced this lineage back at least 300 years, with evidence pointing to an earlier introduction, possibly during the Viking Age.

What Does Haplogroup C1e Reveal?The researchers sequenced the complete mtDNA genome of 11 contemporary carriers of haplogroup C1e, revealing a new subclade not belonging to any of the known Native American or Asian subclades (C1b, C1c, C1d, or C1a). This subclade, dubbed C1e, is presently unique to Iceland. While a Native American origin is most likely, an Asian or European origin cannot be entirely ruled out due to the lack of comparative data.

Interestingly, the genealogical database used in the study indicated that the C1e lineage likely entered Iceland’s gene pool centuries before 1700, possibly during the era of Viking exploration. If this is true, it raises the tantalizing possibility that Norse voyages to North America led to the transportation of at least one Native American woman to Iceland. This leads us to an intriguing possibility: could there have been a ‘Viking Pocahontas’?

Historical and Archaeological ContextWhile the genetic evidence is compelling, it’s essential to consider the historical and archaeological context. Though invaluable historical sources, the sagas provide no direct evidence of intermarriage or partnerships between the Norse and Native Americans. On the contrary, they often depict the Skrælings in a dehumanizing light, emphasizing conflict rather than cooperation.

Archaeological findings at L’Anse aux Meadows and other Norse sites in Greenland show evidence of trade between the Norse and Native populations, such as the presence of butternuts that grow further south in North America. However, there is no clear evidence of long-term interaction or integration of these groups.

Could It Have Happened?Given the Vikings’ proclivity for forming relationships in foreign lands, it is not implausible that a Greenland Norseman could have taken a Native American woman as a partner during their brief sojourns in North America. Such an event, while rare, could explain the presence of haplogroup C1e in Iceland’s genetic pool. However, the lack of corroborating evidence in the sagas or archaeology suggests that if it did happen, it was an isolated incident rather than a widespread practice. Hence the reference to Pocahontas, which is a historical parallel whereby she returned to England with John Smith.

Implications and Future ResearchThe discovery of haplogroup C1e opens new avenues for exploring Viking history and their interactions with other cultures. It also underscores the complexity of genetic ancestry and the need for further research. Could additional genetic studies uncover more evidence of intermixing? Might archaeological discoveries provide new insights into Norse-Native relations?

One exciting prospect is the potential for ancient DNA analysis of skeletal remains from Norse sites in Greenland and Iceland. Such research could confirm whether Native American ancestry existed in these populations during the Viking Age.

Conclusion: A Singular Connection?The evidence for Viking-Native American intermixing remains inconclusive but intriguing. The discovery of haplogroup C1e in Iceland suggests that such a connection is possible, albeit rare. Future research will answer whether this represents a singular event or the tip of a historical iceberg.

As a writer of historical fiction, I find the implications of these genetic findings endlessly intriguing. The potential for stories that weave together the lives of Norse explorers and Native Americans opens the door to a largely unexplored narrative frontier. What might it have been like for a Native American woman to journey to Iceland, leaving her homeland behind to navigate a vastly different culture and climate? How would such an encounter have shaped the lives of the Greenland Norse? These questions ignite the imagination, begging for the careful exploration and humanization that only historical fiction can provide. I would love to see a skilled storyteller bring this possibility to life, crafting a compelling narrative that bridges these worlds and sheds light on what history might not have recorded.

For now, the saga continues, blending history, archaeology, and genetics into a fascinating narrative that reminds us of the Vikings’ enduring legacy—not just as explorers and settlers but also as agents of cultural and genetic exchange.

References and Further Reading:

Ebenesersdóttir, S. S., et al. (2011). "A new subclade of mtDNA haplogroup C1 found in Icelanders: Evidence of pre-Columbian contact?" American Journal of Physical Anthropology. Link to study

Don’t forget to buy my books!

January 7, 2025

Hook, Loom, and Plough: The Viking Life They Don’t Show in TV Series and Films

While perusing recent archaeological findings, an article titled "Viking Settlers in Orkney 'Preferred Fishing to Fighting'" caught my attention. The piece challenged the stereotypical image of the Vikings as relentless raiders and warriors, presenting instead a portrait of a society rooted in craftsmanship, trade, and sustenance. This unexpected glimpse into the everyday lives of Viking settlers in Orkney prompted me to reflect on the often-overlooked contributions of Viking trades to their society and economy. These silent crafts—from fishing to shipbuilding and textile production—shaped the Viking Age just as much as their more infamous exploits.

The findings in Orkney paint a vivid picture of Viking settlers who adapted to their environment, prioritizing fishing and farming over raiding and conquest. Archaeologists unearthed tools and remnants of a thriving local economy, including evidence of fishing nets, hooks, and bone implements for catching fish in the surrounding waters. Additionally, remains of drying racks and fish processing sites suggest that preserved fish was a significant trade commodity. This focus on subsistence and trade rather than pillaging highlights the pragmatic ingenuity of Viking communities, particularly in regions where resources were abundant and violence unnecessary.

The bold claim that these Vikings "preferred fishing to fighting" is rooted in the absence of substantial evidence of raiding activity in the region during this period. Archaeologists have found little in the way of weapons or defensive structures—artifacts that typically indicate a focus on conflict. Instead, the prevalence of fishing equipment and agricultural tools suggests that their energies were directed toward peaceful pursuits. While it is possible that these Vikings engaged in both raiding and subsistence activities, the archaeological record leans heavily in favor of the latter.

As the Orkney article suggests, fishing was a cornerstone of local trade networks. Coastal and deep-sea fishing provided ample food, while preserved fish could be traded with inland settlements. The Viking settlers’ ability to extract sustenance from the sea demonstrated an advanced understanding of their environment and a deep integration into the natural world. This harmonious relationship with nature was mirrored in other crafts, such as comb-making, textile production, and ship carving, integral to the Orkney settlement’s economy.

Consider the artistry of Viking comb-making. Combs crafted from reindeer antlers were functional tools and intricately designed artifacts that showcased the skill and creativity of their makers. These items, discovered in European archaeological sites, were valuable trade goods. The craftsmanship required to produce them highlights a sophisticated understanding of material properties and design.

Textile production, another vital trade, was primarily driven by women using upright looms. Viking women spun wool and wove cloth, producing garments for practical use and trade. Woolen textiles in Orkney suggest that this labor-intensive craft played a crucial role in the settlers’ lives, serving local needs and broader trade networks. The process required significant skill and patience, from preparing raw wool to creating intricate patterns, underscoring its importance in the community’s economic and cultural fabric.

Ship carving epitomizes the ingenuity and ambition of the Viking Age. The longships that carried Norse explorers across oceans and rivers were feats of engineering and artistry. Carved from oak and adorned with intricate designs, these vessels were practical symbols of power and mobility. In Orkney, evidence of shipbuilding underscores its vital role in facilitating trade, travel, and cultural exchange, connecting the settlement to the broader Viking world.

The cumulative impact of these trades on Viking society cannot be overstated. They were the backbone of a thriving economy that extended from Scandinavia to the far reaches of the known world. Viking artisans’ ability to create functional and beautiful goods ensured their products’ desirability across Europe and beyond. This demand facilitated the establishment of extensive trade networks, connecting Viking settlements to diverse cultures and economies. As goods traveled along these routes, so did ideas, technologies, and cultural practices, enriching both Viking and foreign societies.

Archaeological findings reveal that the peaceful focus of the Orkney settlers offers a compelling counterpoint to the narrative of Vikings as marauding raiders. Instead, it highlights their adaptability and the centrality of trade and craft. This nuanced understanding of Viking society allows us to appreciate the interconnectedness of their world, where raids were but one aspect of a complex and multifaceted culture.

When I research for my books, I often find myself delving into these details—the daily routines, the tools, the processes that formed the fabric of Viking life. Understanding how textiles were spun, fish were preserved, or ships were carved allows me to create a richer, more immersive world for my readers. I try to imagine what it might have felt like to stand in a smoky longhouse, hear the clatter of a loom, or smell the brine from drying fish. These sensory elements anchor the past, making it tangible. But even with all this research, the focus of my novels often pulls me back to the archetypal Viking warrior.

My protagonist, Hasting, is very much the stereotypical fighter. His world is raiding and survival, of strategic cunning and martial prowess. He’s not one to sit and reflect on the intricacies of fishing nets or the beauty of a carved comb. He exploits people like the craftsmen and settlers described in the Orkney article, taking what he needs to sustain his journeys. While this focus aligns with the demands of storytelling, I sometimes wish there were more room to explore the quieter aspects of Viking life. Yet, I recognize that daily life, as crucial as it was, doesn’t always make for exciting narrative arcs. Hasting’s perspective is one of action, not introspection, and through him, I explore a very different side of the Viking Age.

The contrast between the lived realities of Viking settlers and the roving life of a warrior like Hasting underscores the diversity within Viking society. The Orkney findings remind us that history is rarely as one-dimensional as it seems. While my novels may focus on the stormy seas and bloody battles, the silent crafts and the rhythms of daily life truly shaped the Viking world. Though often relegated to the background, these details offer a glimpse into the ordinary lives that sustained the extraordinary feats of the Viking Age.

January 6, 2025

Anglo-Saxon Warriors in Byzantium: A Connection Stranger than Fiction?

History is often stranger—and more exciting—than fiction. A recent study exploring connections between Anglo-Saxon Britain and the Byzantine Empire has brought new evidence that early medieval warriors from Britain may have served in Byzantine armies. This discovery reshapes our understanding of early medieval Europe and resonates deeply with themes in my novels, The Fell Deeds of Fate and the upcoming The Empress and Her Wolf. As a writer who loves blending history and imagination, I’m thrilled to see how this research validates my creative liberties in exploring these connections in my stories.

Let’s explore this study's fascinating findings, its historical context, and how it connects to the adventures of Hasting and his crew in my books.

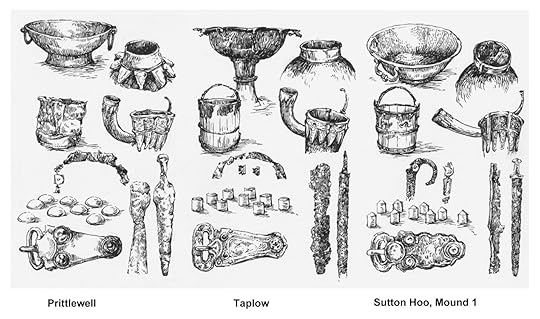

Figure 6. Similarities between princely burials. A selection of objects found at Prittlewell, Taplow, and Sutton Hoo mound 1.Treasures in Anglo-Saxon Graves: Clues to a Byzantine Connection

Figure 6. Similarities between princely burials. A selection of objects found at Prittlewell, Taplow, and Sutton Hoo mound 1.Treasures in Anglo-Saxon Graves: Clues to a Byzantine ConnectionThe study begins with a mystery: How did exotic Byzantine artifacts—such as intricately crafted spoons, basins, and flagons—find their way into the graves of Anglo-Saxon elites? These items, unearthed in famous burial sites like Sutton Hoo and Prittlewell, are not only rare but seem to have been acquired directly in the Eastern Mediterranean. This raises the tantalizing possibility that the individuals buried in these graves might have traveled to Byzantium.

Take, for example, a copper-alloy flagon found in the Prittlewell grave. Decorated with imagery linked to the cult of St. Sergius in Syria, this object wasn’t a mass-produced export. Its presence in an Anglo-Saxon burial suggests it was brought back by someone who had been to the region. Similarly, a large silver spoon inscribed with Greek lettering and a basin thought to have originated in Egypt or Constantinople further support the idea of direct contact between Britain and the Byzantine world.

These artifacts offer more than just aesthetic value; they are tangible evidence of a far-reaching network that connected early medieval Britain to the Mediterranean. But who were the people who traveled such vast distances, and why did they make these journeys?

Anglo-Saxons in the Byzantine MilitaryThe answer may lie in the Byzantine Empire’s military recruitment campaigns during the late 6th and early 7th centuries. At this time, the Byzantines were engaged in a prolonged conflict with the Sasanian Empire, a rivalry that stretched their resources thin. In response, the emperor launched large-scale recruitment efforts across Western Europe, enlisting warriors from Francia, Germania, and potentially even Britain.

These recruits may have served as elite cavalry, fighting on the empire’s northeastern frontier in places like Armenia and Syria. Known for their equestrian skills, these soldiers would have been well-equipped and well-paid, returning home with both wealth and stories of their adventures in one of the most powerful empires of the time. Historical accounts even hint at the presence of “Britons” in the Byzantine military, suggesting that Anglo-Saxon warriors might have joined this cosmopolitan force.

This idea aligns with the material evidence from Anglo-Saxon graves. The exotic goods found in these burials weren’t just rare—they were new when interred. This freshness suggests that the items weren’t passed down through generations or acquired secondhand but were brought back by individuals recently traveling to the Byzantine world.

A Cosmopolitan Equestrian EliteThe study also highlights the broader cultural context of early medieval Britain, portraying its equestrian elite as a remarkably cosmopolitan class. They were not isolated tribal leaders but influential figures with connections that spanned kingdoms and continents. Their graves, adorned with imported goods and equestrian symbols, reflect their status as part of a wider network of power and prestige.

This interconnectedness is evident in the exotic items buried with them and in the shared aesthetic and cultural practices across early medieval Britain. From the architecture of great hall complexes to the design of horse harnesses, these elites displayed a unified cultural idiom that connected them to the broader European and Mediterranean worlds.

Why This Study MattersThis study is more than just an academic finding—it’s a reminder of how interconnected the medieval world was. It challenges the notion of early medieval Britain as an isolated island on the fringes of Europe. Instead, it places it firmly within a network of cultural and military exchanges that spanned continents.

Connecting History to Fiction: Hasting and the ByzantinesAs I read this study, I couldn’t help but think of my work. In The Empress and Her Wolf, I explore the theme of Viking warriors serving in the Byzantine Empire, focusing on Hasting and his crew navigating Constantinople's political and military complexities. While the historical Varangian Guard wasn’t formalized until the 10th century, I took creative liberties by imagining Hasting and his men as early mercenaries in the service of Empress Theodora during the 9th century.

At the time, I wondered if this was a bit of a stretch. But this study shows that Anglo-Saxons or other Northern Europeans serving Byzantium centuries earlier isn’t far-fetched. The evidence suggests that such exchanges were part of a long tradition, making my portrayal of Hasting’s adventures plausible and deeply rooted in historical possibility.

For me, this is one of the most exciting aspects of historical fiction: weaving together imagination and scholarship to bring the past to life. Hasting’s journey to Constantinople in The Fell Deeds of Fate and his service to Empress Theodora in The Empress and Her Wolf reflect his quest for redemption and the broader cultural and historical dynamics of the time.

As I continue to write about Hasting’s adventures, this study serves as both validation and inspiration. It shows that the themes I’ve explored in my novels—cultural exchange, personal ambition, and the bonds forged through shared experiences—are not just speculative fiction but reflections of historical realities. The Anglo-Saxon warriors who may have served Byzantium remind us that history is not a static collection of dates and facts but a dynamic, interconnected web of human experiences.

This is an exciting time for fans of history and historical fiction alike. As discoveries come to light, they deepen our understanding of the past and open up new possibilities for storytelling. Whether you’re uncovering artifacts in a burial mound or following Hasting’s adventures in Constantinople, the journey is always one of discovery and wonder.

So here’s to the shared adventure of history and fiction—and to the stories that connect us across time. Check out The Fell Deeds of Fate, available now:

January 5, 2025

Unveiling the Hidden Genetic History of the Viking Age: A Revolutionary Study Kicks Off 2025

A cartoon representation of “Viking DNA”

A cartoon representation of “Viking DNA”The genomic history of early medieval Europe is as complex and intriguing as the period itself. In a study published on January 1, 2025, in Nature, researchers have shed new light on this era, particularly the Viking Age, by analyzing over 1,500 ancient genomes using an innovative computational tool called Twigstats. This groundbreaking approach has allowed scientists to trace populations' migrations, interactions, and transformations with unprecedented precision. A tapestry of ancestry emerges, woven together by the movements of peoples across Europe, with Scandinavia playing a central role.

Key Findings: Scandinavian Influence Across EuropeThe study revealed two significant waves of Scandinavian-related ancestry spreading throughout Europe. The first wave, beginning in the early centuries of the first millennium CE, saw groups from Scandinavia expanding southward into central and eastern Europe. These migrations predate the Viking Age but laid the groundwork for the cultural and genetic diversity that would characterize the period. The second wave came around 800 CE, coinciding with the start of the Viking Age. During this time, Scandinavia experienced an influx of ancestry from groups related to central Europe, marking a dynamic exchange of peoples and ideas. This genetic flow underscores the Vikings’ connections to their neighbors as raiders, settlers, and participants in a broader European network.

Regional variations in ancestry further highlight the complexity of this period. In Poland and Slovakia, early medieval populations displayed strong ties to northern Scandinavian ancestry, suggesting significant movement from Scandinavia into these regions. Meanwhile, in southern Scandinavia, evidence of admixture with central European populations painted a different picture, reflecting local interactions and integration. This regional diversity underscores the rich, multifaceted nature of Viking society, challenging any notion of homogeneity among these northern seafarers.

The study also demonstrated that genetic distinctions between populations were becoming increasingly blurred by the early medieval period. This process of ancestry homogenization, particularly during the transition from the Iron Age, reflects extensive admixture across Europe. These findings provide a more nuanced view of the Viking Age and prompt us to consider the deep roots of this genetic diversity, stretching back centuries before the Vikings set sail.

Twigstats: A New Tool for Genomic AnalysisThe researchers' methodological approach was as innovative as the findings themselves. The Twigstats tool uses time-stratified genealogical analysis, focusing on recent genetic events to enhance the resolution of ancestry models. This technique significantly reduces noise in the data, allowing for more accurate reconstructions of genetic history. By incorporating genealogical information into traditional population genetics, Twigstats offers a fresh lens through which to view the past.

Weaknesses in the MethodologyAs impressive as this method is, it is not without its limitations. The study relied on a dataset of over 1,500 genomes, but this representation was uneven, with certain regions like central Europe underrepresented. This scarcity of data limits the ability to capture the full scope of genetic interactions and can lead to incomplete or skewed conclusions. Furthermore, the technique depends on high-quality ancient genomes. When samples are degraded or poorly sequenced, they can introduce biases, affecting the reliability of ancestry estimates. The assumptions underlying the genealogy-based models—such as mutation rates and population structures—add another layer of uncertainty. Misjudgments in these areas could distort interpretations of historical events.

Why These Limitations MatterThese limitations matter because they remind us of the provisional nature of such findings. Historical narratives based solely on genetic data risk oversimplifying complex processes. For example, the genetic shifts observed in Scandinavia before the Viking Age suggest pre-existing diversity that complicates the idea of Vikings as a monolithic group. Yet, these genetic patterns remain a single piece of the puzzle without corroboration from archaeology, linguistics, or cultural studies. To build a more complete picture, we must integrate these disciplines, ensuring that genomics enhances, rather than narrows, our understanding of the past.

Implications for Understanding the Viking AgeDespite its limitations, the study offers tantalizing insights into the Viking Age. It reaffirms the Vikings’ remarkable mobility, not only raiding but settling and intermingling with local populations. This blending of cultures and genes was far-reaching, stretching from Britain to the Baltic and beyond. It also reveals the deep connections between Scandinavia and central Europe, which were well-established before the Viking Age but became even more pronounced during it. These findings prompt us to rethink the Viking Age not just as a period of conquest but as one of exchange and integration.

Perhaps most importantly, the study hints at how the Vikings themselves were shaped by the genetic and cultural flows they participated in. The influx of central European ancestry into Scandinavia before the Viking Age suggests that their maritime ventures were not the starting point of their interactions with the broader world but a continuation of long-standing relationships. This perspective enriches our understanding of the Viking Age, situating it within a wider historical context of mobility and transformation.

The Future of Genomic Research in HistoryAs impressive as this study is, it should be viewed as a stepping stone rather than a final word. The field of paleogenomics is still evolving, and its potential for historical research remains vast but untapped. We need more extensive and more geographically representative datasets to build a comprehensive picture of historical migrations. This will help fill gaps and provide a more balanced view of history. Combining genetic data with archaeological, linguistic, and historical evidence can provide a richer and more nuanced understanding of the past. Continued innovation in genome sequencing and computational tools will improve the accuracy and resolution of genetic analyses, opening new doors for historical research.

Conclusion: A Cautious but Promising OutlookThis study offers a fascinating glimpse into the genetic history of early medieval Europe and the Viking Age. Its findings highlight the Vikings’ far-reaching influence and underscore the complexity of their interactions with other populations. However, the limitations of the methodology remind us that these conclusions are not definitive.

In my opinion, more studies like this are essential to deepening our understanding of history. As genomic technologies advance, they will provide sharper tools for reconstructing the past. However, we must be cautious about drawing firm conclusions until we have more data and refined methods. History is a vast, intricate mosaic, and genomics is just one piece of the puzzle—albeit a powerful and promising one.

I hope you enjoyed this article. If this is a subject that interests you, please consider supporting my work by purchasing my books:January 4, 2025

Viking Cats: Uncovering the Viking Diaspora Through Feline DNA

The Viking Age (793–1066 CE) was a period marked by extensive maritime exploration, trade, and settlement, defined by the movement of people, goods, and cultural practices across vast territories. While much is known about Viking activities through archaeological evidence and historical records, recent research into the DNA of domestic cats provides a novel perspective. These studies reveal how cats, carried aboard Viking ships as pest controllers, were unwitting agents of Viking expansion. The genetic footprints of these feline companions further illuminate the extent and intricacies of Viking trade and settlement patterns, contributing a unique and (dare I say) cute dimension to the understanding of the Viking diaspora.

The Function and Symbolism of Cats in Viking Society

Cats played a critical role in Viking life, both practically and symbolically. On Viking ships and within settlements, cats were vital for controlling rodents, which threatened food supplies like grain and dried fish. Their utility aboard longships made them essential for seafaring Norse communities. Cats may have been must-haves in regard to preparing a ship for a long sea voyage.

Beyond their practical value, cats also held cultural and mythological significance. In Norse mythology, Freyja, the goddess of fertility, love, and war, was said to drive a chariot pulled by two large cats, perhaps alluding to their critical role in travel. The discovery of cats buried alongside humans in Viking graves further supports the notion that these animals were valued companions and possibly seen as protectors in the afterlife

Genetic Evidence: Tracing the Movement of Cats

Recent genetic research has provided compelling evidence for the movement of cats during the Viking Age. By analyzing mitochondrial DNA from ancient cat remains found at Viking sites, scientists have traced the dispersal of domestic cats alongside Viking expansion. One striking discovery is the presence of cats with Egyptian mitochondrial DNA in Hedeby, a major Viking Age trade hub. These findings indicate that cats of Near Eastern origin traveled through established trade routes, eventually arriving in Scandinavia, and may point to the Vikings having trade ties with Northern Africa.

The genetic markers of these cats reveal a second wave of feline dispersal. The first wave, associated with the spread of agriculture in the Neolithic period, saw cats expand their range alongside early farming communities. The second wave, driven by maritime cultures like the Vikings, facilitated the further spread of cats across Europe and the North Atlantic. This second wave underscores the Vikings’ role in disseminating goods, animals, and cultural practices across vast distances.

Cats as Indicators of the Viking Diaspora

The Viking diaspora refers to the spread of Norse people, culture, and influence beyond Scandinavia. While this phenomenon is traditionally studied through human remains, artifacts, and settlement patterns, the genetic analysis of cats offers a complementary lens. The deliberate transport of cats by Vikings highlights their integration into Norse life and provides tangible evidence of Viking movements and trade networks.

The presence of cats with shared genetic markers in Scandinavia, the British Isles, Iceland, and Greenland demonstrates that these animals were deliberately introduced into Viking colonies. Their survival and proliferation in harsh environments such as Greenland reflect their adaptability and the efforts of settlers to recreate familiar elements of home in new lands.

Insights into Viking Connectivity and Trade Networks

The genetic diversity of cats found at Viking sites underscores the extensive connectivity of the Viking world. Major trade hubs like Hedeby and Birka were central to the exchange of goods, ideas, and biological resources, linking the Norse to distant regions such as the Mediterranean and the Near East. The introduction of Egyptian-lineage cats into Scandinavia exemplifies the long-distance trade networks that the Vikings actively participated in.

These findings also illustrate how Viking trade networks were not solely focused on material goods like silver and textiles but also involved the exchange of living organisms. Cats, as part of these networks, provide a unique perspective on the movement of biological resources and the integration of foreign elements into Norse culture.

Cultural and Ecological Implications

The spread of cats by the Vikings carries both cultural and ecological significance. As introduced species, cats likely influenced local ecosystems, particularly in insular environments like Iceland and Greenland. While their primary role was pest control, their presence may have had unintended consequences for native wildlife populations, mirroring modern discussions about the ecological impacts of species introduction.

Culturally, the integration of cats into Viking settlements reflects their symbolic and emotional importance. Cats’ presence in burial sites suggests that they were considered not only functional animals but also valued companions. This relationship highlights the human dimension of the Viking diaspora, emphasizing the personal and cultural motivations behind Viking expansion.

Methodological Contributions to Viking Studies

The use of animal DNA to reconstruct aspects of human history represents a significant methodological innovation in archaeology and history. The genetic analysis of cats complements traditional approaches to studying the Viking Age, offering new insights into Norse activities and their interconnected world.

By integrating genetic data with archaeological evidence, researchers can reconstruct trade routes, settlement patterns, and cultural practices with greater precision. This multidisciplinary approach enriches the study of the Viking diaspora, highlighting the complexities of Norse life and their interactions with other societies.

Reassessing the Viking Diaspora

The dissemination of domestic cats by Vikings provides a framework for reevaluating the nature of the Viking diaspora. While Vikings are often characterized as raiders and conquerors, the movement of cats emphasizes their roles as traders and participants in extensive cultural and economic networks. This perspective aligns with contemporary scholarship that seeks to portray the Vikings as multifaceted actors engaged in both violent and peaceful exchanges.

The transport of cats also reflects the human need to maintain continuity in new environments. By bringing familiar animals with them, Vikings sought to recreate aspects of their home life, demonstrating a blend of practicality and emotional attachment. These findings add depth to our understanding of Viking expansion as a dynamic process shaped by both external pressures and internal motivations.

Conclusion: Feline DNA as a Historical Tool

The study of Viking cats offers a unique and innovative perspective on the Viking Age. By analyzing the genetic markers of these animals, researchers have uncovered new evidence of Viking trade routes, settlement patterns, and cultural practices. These findings contribute to a broader understanding of the Viking diaspora, emphasizing the interconnectedness of human and animal histories.

Cats, as both functional and symbolic companions, played a vital role in Viking life. Their presence aboard ships and in settlements underscores their importance to Norse society, while their genetic legacy provides tangible evidence of the Vikings’ far-reaching influence. By examining the movement of cats, we gain not only a better understanding of Viking expansion but also a richer appreciation for the complex relationships between humans and animals throughout history.

References

• “Viking Sailors Took Their Cats With Them.” ScienceNordic, 2016. Read more.

• “Cats Sailed With Vikings to Conquer the World, Genetic Study Reveals.” ScienceAlert, 2016. Read more.

January 3, 2025

I think I Solved the Vikings of Namborg Mystery.

The Viking presence in Nantes, France, which the Vikings called Namborg, presents a historical enigma that has long perplexed scholars. When Alain Barbetorte, a Breton nobleman, reconquered Brittany from the Vikings and retook Nantes in 937 A.S., he found a largely derelict city almost abandoned. This discovery remains puzzling. According to Lucien Mucet’s phases of Viking expansion and the similarities between Nantes and Jorvik in the British Isles, Nantes should have developed into a bustling trade hub like Jorvik. Why this disparity occurred remains unresolved, but I believe I have uncovered a key factor that explains it.

This mystery came up during a conversation on the Vikingology podcast with my co-host, Terri Barnes, and our guest, Dr. Tom Horne. Dr. Horne, a renowned scholar on Viking history, shared his research on the Great Heathen Army in Northern England, which sparked an intriguing discussion about Viking settlement strategies. Dr. Horne’s concept of the “nodal system” posits that the Vikings did not seek to conquer large territories but instead focused on controlling specific trade centers, or “nodes,” that acted as hubs of economic activity. This theory challenges the conventional view of Viking expansion as a widespread conquest of land and people. Dr. Horne’s insights inspired me to rethink the nature of Viking influence in Britain and continental Europe.

I questioned whether the prevailing narrative of the Danish conquest and population replacement in what became the Danelaw was an oversimplification. This theory, which explains the proliferation of Norse place names in England, suggests that the Danes intermixed with and often displaced the local Anglo-Saxon populations. However, was Dr. Horne suggesting an alternative interpretation? Could Norse control over the economy, rather than mass settlement, lead locals to adopt Norse as a lingua franca for trade? If this were the case, the proliferation of Norse place names would not result from population replacement but rather a product of cultural and economic exchange.

I considered a historical parallel with pre-Roman England. Before the Romans arrived, the inhabitants of Britain were not Celts, yet they had adopted the Celtic language and culture of Gaul through trade. Could Viking place names in England similarly reflect the impact of trade and language rather than the remnants of large-scale conquest?

In a previous Vikingology podcast episode, Dr. Claire Downham suggested that Norse had become the language of trade in the British Isles. This theory complements the idea that Viking place names did not necessarily signify territorial conquest but instead marked the influence of Norse traders over the region’s economy. Trade, not settlement, may have driven the spread of Norse language and culture. In no uncertain terms, the Vikings acquired that control through force, but they were strategic about allocating their resources given their small numbers.

Supporting this hypothesis, I recall a study from the early 2000s that investigated the presence of Norse DNA in modern English populations. The study concluded that the genetic makeup of Anglo-Saxons and Danes from the Viking Age was too similar to distinguish between them. This result led some scholars to question the extent of Viking genetic influence in England. But could this conclusion be based on a misunderstanding of the Viking impact? What if the Vikings did not leave a significant genetic legacy in England because they did not settle in as substantial numbers as previously thought? Instead, their influence might have been primarily cultural, transmitted through trade and language rather than biological exchange. This would explain the relatively low genetic impact despite the abundance of Viking place names.

Turning back to the mystery of Nantes in Brittany, the Viking occupation lasted approximately 30 years, yet the region lacks the abundance of Viking place names found in England. In fact, they have none. This raises a critical question: why did the Viking presence in Nantes fail to produce the same economic and cultural results as Jorvik? Previous scholarship has suggested the Vikings did not have the numbers they did in the British Isles, limiting their ability to impact the region. However, if force of numbers did not lead to the wealth of place names in England, that cannot be the answer. If trade and language played a critical role in the legacy of Norse place names in the British Isles, what prevented it from accomplishing the same in Nantes?

Linguistic differences provide a crucial clue. Breton and Frankish, the languages spoken in Nantes and broader Brittany, would have been far more distinct from Old Norse than Anglo-Saxon. The Vikings and Anglo-Saxons, scholars believe) could understand each other’s languages with relative ease, facilitating using Norse as a lingua franca for trade. In contrast, the linguistic gulf between Norse and the languages of Brittany and France would have made it far more difficult for Norse to become a common language of commerce. This linguistic barrier could explain why the Vikings in Brittany did not have the same long-term cultural influence as they did in England. They took over the nodes, such as the city of Nantes, but the local population did not buy into making Norse the defacto language of trade.

Moreover, the nature of Viking trade in the British Isles differed significantly from that in France. In England, much of the Viking trade flowed back to Scandinavia, creating a continuous economic exchange that reinforced the use of Norse as a trade language. In Brittany, however, the Vikings traded primarily with the Franks, establishing markets under royal charters and securing tax exemptions, as we had discussed with Christian Coojimans in a previous episode of Vikingology. For instance, salt producers on Noirmoutier were granted tax exemptions in 828 amid an alleged Viking occupation, and a market was set up on the island of Betia (near Nantes) in 853 by royal charter. The trade structure in Brittany did not facilitate the same kind of economic integration with Scandinavia that occurred in the British Isles, where Jorvik became a hub for the exchange of goods and culture across Britain and Scandinavia. As a result, Nantes did not become the vibrant trade center that Jorvik was, and the lack of a lingua franca like Norse further hindered the Vikings’ ability to exert lasting influence.

In conclusion, the mystery of Nantes and the Viking presence in Brittany challenges our conventional understanding of Viking expansion. Rather than seeing the Vikings as large-scale conquerors, it seems more plausible that they controlled key economic nodes through trade and language. The Vikings’ impact on place names in England likely stemmed from their control of trade rather than widespread settlement or conquest. This theory also helps explain why genetic studies have failed to uncover a significant Viking legacy in England—the Vikings’ influence was primarily cultural, transmitted through trade and language rather than biological exchange. By examining the Viking experience in Nantes, we gain new insights into how the Vikings shaped the economies and cultures of the regions they interacted with, and we begin to see the Viking Age not as a period of conquest but as an era of profound cultural and linguistic exchange.

OK, but there was a good amount of conquering. ;)

Entertained? Consider supporting my work. Or, in Viking-speak: buy my books, you filthy heathens!

December 20, 2024

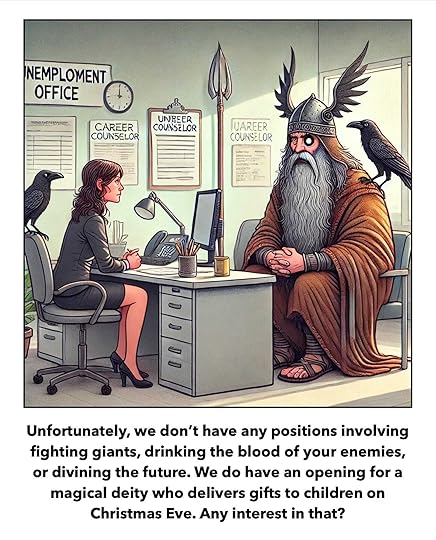

Is Santa Claus Really Odin?

A persistent meme has circulated on the internet for years, claiming that the Norse god Odin inspired today’s Santa Claus. With his flowing white beard, gift-giving tendencies, and supernatural mount, Odin, the All-Father of Norse mythology, certainly shares some surface-level similarities with the modern Christmas figure. But how valid is this claim? Let’s examine the roots of this intriguing theory, review the evidence, and explore why the historical Santa Claus ultimately owes little to the Norse god.

The Odin-Santa Connection: A Closer Look

The Odin-Santa theory largely stems from several striking parallels between the two figures:

Appearance: Odin is often depicted as an old man with a long, white beard who wears a cloak and hat, a description that resembles the traditional image of Santa Claus. He has also been depicted wearing festive colors associated with Christmas, such as gold, green, and red.

Gift-Giving: In Norse myths, Odin rode his eight-legged horse, Sleipnir, during the Wild Hunt, a supernatural event that took place in winter. Some interpretations suggest that children left offerings of food for Sleipnir, and in return, Odin provided small gifts, a practice similar to leaving cookies and milk for Santa Claus.

Flying Mount: Odin’s Sleipnir could cover great distances and even fly, much like Santa’s reindeer, which pull his sleigh through the skies on Christmas Eve. Some have even proposed a connection between Sleipnir’s eight legs and Santa’s eight reindeer.

All-Seeing Nature: Odin was recognized as a god of wisdom and knowledge, frequently observing the world. This omniscience parallels Santa’s purported ability to know whether children have been naughty or nice.

Evidence for Norse Influence on Christmas Traditions

The argument that Odin influenced Santa Claus is part of a broader narrative about how pagan traditions have merged with Christian holidays over time. The Norse Yule festival, celebrated during winter, featured feasts, toasts, and gift-giving. Some scholars argue that elements of Yule were incorporated into Christmas traditions as Christianity spread through Scandinavia and northern Europe.

Furthermore, Father Christmas, a precursor to Santa Claus in England, was sometimes portrayed as a bearded, cloaked old man. This description might have evoked memories of the Anglo-Saxon equivalent of Odin, Woden, or other folkloric figures.

The True Origins of Santa Claus

Despite these intriguing parallels, the notion that Odin directly inspires Santa Claus breaks down under closer examination. The contemporary Santa Claus has a much more straightforward and traceable origin, rooted in historical figures and folklore.

Saint Nicholas: The historical Saint Nicholas, a 4th-century Christian bishop from Myra (in present-day Turkey), is the basis for Santa Claus. Renowned for his generosity, especially toward children and the less fortunate, Saint Nicholas’s compassionate deeds inspired tales that spread throughout Europe. In the Netherlands, he became known as Sinterklaas, who later became Santa Claus through Dutch settlers in America.

The American Evolution: The modern portrayal of Santa Claus owes much to 19th-century American writers and artists. In 1823, Clement Clarke Moore’s poem “A Visit from St. Nicholas” (commonly known as “The Night Before Christmas”) solidified many of Santa’s characteristics: a cheerful demeanor, a sleigh pulled by reindeer, and the tradition of delivering gifts down chimneys. This version of Santa Claus was further popularized by political cartoonist Thomas Nast, whose illustrations from the late 1800s established the red-suited, plump figure we recognize today.

Commercialization and Coca-Cola: In the 20th century, Santa Claus emerged as a global icon, partly due to advertising. The Coca-Cola Company’s holiday campaigns in the 1930s, portraying Santa Claus as a jolly, plump man in a red suit, cemented his image in popular culture.

Breaking Down the Odin-Santa Myth

While it is tempting to draw connections between Odin and Santa Claus, historical evidence suggests that Santa’s development was influenced more by Christian traditions, folklore, and commercialization than by Norse mythology. Let’s examine the specific claims:

Appearance: The image of Santa Claus as an elderly, bearded man in a red suit or cloak is more likely derived from Saint Nicholas and later artistic interpretations than from Odin. Odin’s depiction varies significantly across different sources, and his appearance as a bearded wanderer is not exclusive to Norse mythology.

Gift-Giving: The connection between Odin’s gifts during the Wild Hunt and Santa’s presents is weak. There is little evidence to suggest that Odin’s mythical journeys involved anything similar to the widespread and structured gift-giving associated with Santa Claus.

Flying Mount: Sleipnir’s ability to fly is an intriguing parallel, but flying mounts are a common motif in mythologies worldwide. The idea of flying reindeer pulling a sleigh is a much later invention and has no direct connections to Norse mythology.

Omniscience: Santa’s ability to know about children’s behavior is more likely influenced by Christian concepts of divine omniscience and judgment than by Odin’s wisdom and attentiveness.

Conclusion: A Blend of Traditions

Like horns on a helmet, the notion that Odin directly inspires Santa Claus is a modern myth and not a historical fact. While Christmas traditions have absorbed elements from various cultural practices, including Norse Yule celebrations, the figure of Santa Claus is primarily a product of Christian sainthood, 19th-century American literature, and modern commercialism.

Odin’s presence in the meme-ified version of Santa Claus reflects our collective fascination with linking modern traditions to ancient roots. However, it’s essential to approach such claims critically, recognizing the rich tapestry of influences that shape our holidays without overstating any single source. Ultimately, Santa Claus is born not of Asgard, but of human imagination, molded by centuries of storytelling, adaptation, and cultural exchange.

While Santa is not Odin, that does not mean you shouldn’t treat yourself to something nice this holiday season. Give yourself the gift of Vikings and download my latest Viking historical fiction novel The Fell Deeds of Fate.

Purchase The Fell Deeds of Fate

December 1, 2024

The Fell Deeds of Fate - The Viking Hasting's boldest adventure yet!

🌊⚔️ Embark on the Viking adventure of a lifetime! ⚔️🌊

✨ PRAISE FOR THE FELL DEEDS OF FATE ✨

The Book Commentary: "The Fell Deeds of Fate is richly detailed, conveying the harsh truths of Viking life and the visceral landscape of Northern Europe. From fierce ocean battles to intimate moments of domesticity, Adrien creates a world where the elements play an integral role in shaping the characters' fates, reflecting the brutal yet vibrant nature of the Viking Age. The prose is delectable, and the overall writing is cinematic.

Reader's Favorite Book Reviews: "The Fell Deeds of Fate is a masterful blend of historical fiction and mythological undertones, making it a must-read for fans of Viking tales and epic sagas. Adrien crafts a world as brutal as it is captivating...highly recommended."

Ian Stuart Sharpe, author of The Vikingverse: "CJ Adrien's Fell Deeds of Fate is a riveting journey through time, delivering a Viking Age saga for the ages. A masterwork filled with thrilling encounters and dramatic twists that holds you captive till the very last page."

J.M. Gillingham, author of the Ten-Tree Saga: "C.J. Adrien has laid forth another saga worthy of the heroes of old. With many narrative tie-ins and continuations from Adrien's The Saga of Hasting the Avenger trilogy, new and old fans are in for a ravens-feast of sharpened steel, shining silver, and long-hidden secrets!"

✨ PRAISE FOR C.J. ADRIEN ✨

🔥 “C.J. Adrien places the reader into the thick of the tale... A must-read for those who enjoy Viking stories.” – The Historical Novel Society

🔥 “C.J. Adrien packs a full force of realistic history and excellent knowledge into his novels.” – Reader's Favorite

🔥 “C.J. Adrien steeps us in period detail and political backbiting in a richly imagined world.” – Kirkus Reviews

For Hasting the Avenger, fame and glory were supposed to last forever.

Two years after the legendary sack of Paris, Hasting remains haunted—not by his triumph but by the bitter twist of fate that Ragnar’s name made it into the songs of the Skalds and not his. Drowning in resentment and drink, he has become a shadow of the warrior he once was. When his wife divorces him, strips him of his wealth, and takes his son, Hasting’s world collapses around him.

Then, a chance reunion with his old comrade Bjorn Ironsides sparks an audacious idea. He will outdo Paris by accomplishing something so grand and unforgettable that the world will never again question his legacy. His target: Miklagard, the Great City of Constantinople.

Driven by a desperate need to prove his worth, Hasting embarks on an epic journey across roiling seas, icy rivers, and untamed lands, rallying old allies and clashing with powerful new rivals. To succeed, Hasting must confront the root of his obsession with immortality and the cost it demands, not only of himself but of those who follow him.

THE FELL DEEDS OF FATE, CHAPTER 1 EXCERPT: SELFISH AND WICKEDIt is true what they say, that I was cursed the day I sacked Paris. Fame, glory, and great wealth should have been mine, but they were stolen. Another took my place among the skalds and scribes. By a cruel twist of fate, the name the Franks remembered from my meeting with Charles was that of my ally Ragnar, who no more propelled us to victory than the goats we kept for food. I conquered Paris. It was mine. And it was I who should have been remembered.

Embittered by the usurpation of my deeds, I resigned myself to my island. I would start a family with my new wife, Reifdis, the daughter of my former ally, Jarl Thorgisl, and I hoped I might find respite. At first, she inspired in me a desire for peace, to raise a family, and to let the world’s woes pass us by. We had a Royal Charter signed by the Celts and the Franks to own the land we cultivated and a hirð at our call to defend us. The gods gave us many blessings, but they always collect on their debts. Peace was not my fate. No, the beast in my heart beckoned. It called to me. My restlessness made me irritable and discontented, and my behavior drove Reifdis mad.

On the day the gods decided our first child should join us in this world, two years after I returned from Paris, distant sails dotted the pale blue horizon to the west. It was a clear spring day. Flowers sprang up in the fields, the birds sang their songs, and Reifdis’ moans of agony rang out across our village as the men donned their arms and armor and readied for battle.

I stayed with Reifdis in our bedchamber as long as I could while her midwife worked to relieve her pain. My wife stood in the corner of the room, her hands pressed against the wood-planked walls, standing over the mud her water had made when it hit the ashen floor. I had fought countless battles and witnessed many horrors, but none had prepared me for the fear I felt watching Reifdis fight for her life to create a new one. And yet, as much as I wanted to stay with her to see it through, the wider world drew me away with a forceful knock at the door.

“Fuck—off!” Reifdis roared.

The fury of her growl gave me pause. I slipped out of the room to find my húskarl, or head warrior, Bjarki, dressed for war and ready to set sail. He was an older man with a broad face, striking red hair, and a thick beard braided with Frankish glass beads.

“The men are ready, Hasting,” he said.

“The baby is close,” I said.

“The men are waiting,” Bjarki insisted.

He was right. As much as I wanted to witness my child’s birth, I had a duty to my people. I nodded and slipped back into the bedchamber.

“I have to leave now,” I said.

“Go,” she groaned between labored breaths. “If there’s one thing you’re good for, it’s fighting. If by some luck I survive this hell, I don’t want my baby to be killed by Danes or Saracens.”

She let out a reckless laugh, but her pain gripped her and brought her back down. Her courage and grit shined through even in this most dangerous of times, and despite her cutting words, I admired her for it. I tried to kiss her on the cheek, but she swatted me off, and I fled.

Bjarki and I marched with all due haste to our ships. Mine was a warship with thirty-two oarlocks named Sail Horse. She had a prow carved in the likeness of the serpent Nidhog and a checkered sail of blue and yellow—the colors of my house. I inherited her from my first captain, Eilif, who died at the Giant’s Throne, and I had owned her for over ten years. She had been my most reliable and faithful companion.

Bjarki boarded his ship, which he had named Oak Raven. She was a larger warship than Sail Horse, with sixty oarlocks and a simple post for a prow. He had offered her to me since it was the largest of our ships, but I could not part with mine. Our third ship, Riveted Serpent, looked identical to Sail Horse except for the simple post for a prow. She belonged to one of our other hirðmenn named Ake. Ake was, like Bjarki, an older man, perhaps in his fifties, with greying black hair and a narrow jawline under a hooked nose. He had served Reifdis’ father in Ireland before joining our hirð out of loyalty to her.

I stepped up to the prow, riding Sail Horse like a steed over the water. A cool breeze brushed back my long, curly brown hair, and the waves crashing against our hull sprayed the air with salt. It brought me back to when I first rode the ship’s prow with my friend Asa. We were children then. It had been my first journey to the coast of Armorica, which I now called my home, and I had fallen in love with the richness of its land and sea from the moment I first saw them.

Sail Horse crashed into a rogue wave, jolting me out of my memory and back to the task at hand. Closing in on our prey, my crew lowered our sails and set our oars to water. The shift in the ship’s tilt lurched me forward, forcing me to catch myself on the gunwale. Toward the horizon, the shapes of hulls and sails lurked like shark fins over the waves. They had three long and narrow ships with two triangular sails overhead. When they saw us lower our sails, they steered out of the wind and in our direction, using their oars to gallop at us. It was a bad sign.

Bjarki steered Oak Raven up beside us, close enough so we could speak. He had donned his maille shirt over a wool overcoat, with a gold-tipped leather belt tied around his waist. He leaned over his gunwale, sloped in the shoulders, and shouted, “They’re galleys.”

Galleys are warships, or at least the most common warships sailed by the Franks, the Celts, and the Moors. They have long and slender hulls, not unlike our ships, but they are built by laying the planks edge to edge and sealing them with caulking. It makes their hulls strong but inflexible and heavy. Our ships overlap the planks—or strakes—making them far faster, more flexible, and able to navigate in shallower water. Galleys have a large sail at the center and a smaller one in front of it, and like our ships, they use oars to maneuver in close quarters. But unlike ours, one cannot tell how many men they carry by how many oars they put into the water. Their fighting men do not row as ours do.

These galleys flew a black flag, the symbol of Moorish raiders. And the Moors had a vendetta against our kin. Moorish raids in Francia had started long before the Danes and the Northmen arrived, but the frequency with which they betook themselves north from Al-Andalus had increased tenfold since we had sacked their capital, Seville. I had no small part in that raid. My head would have made a fine prize for their captain. In fact, I had a sneaking suspicion that’s what he was after—not loot, not slaves, but my head.

“Strike fast and strike hard.” I pointed to the galley at the center. “The one flying the black banner and the smaller gold one underneath it, that’s their leader. Tell Ake that we all strike him first. We’ll take them down one by one.”

“Just like last time,” Bjarki said with a smile.

“Just like last time,” I replied.

Bjarki nodded and returned to face his men and barked orders. With the wind at our back, we hoisted our sails again to give us a speed advantage. The galleys loosened their formation to give room for their oars, giving us the room we needed to sail through. Bjarki led his ship into battle first. His men lifted their shields over their shoulders and steered themselves at full sail between two galleys. Their ship thundered as it dashed through the narrow space between the Moorish ships and broke dozens of their oars. A swarm of arrows clattered across Oak Raven’s deck. Halfway through the gap, the galley oars halted Oak Raven. Bjarki’s men dropped the sail and threw hooks at the ship in the center and pulled themselves close enough to board her.

“Shields up!” I commanded as Sail Horse charged at a gallop to do the same on the other side.

We crashed through oars, took two volleys of arrows, and hooked ourselves to the center ship as Bjarki had done. An arrow had found its way through our shields and pierced someone’s flesh, spattering the deck beside me with hot red blood. I followed the trail to see who had taken the hit. It led to my leg. I marveled at it, wondering why I had not felt its sting. Its iron head had passed clean through and struck far enough away from the groin that I did not fear bleeding out. So long as I left it in place, I could still fight.

I unsheathed my sword, brandished it over my head, and cried out, “With me!”

I leaped over the gunwale onto the enemy deck. They met me with spears, pole blades, and curved swords. My shield repelled them long enough for my men to leap aboard and force them back. Bjarki’s men had already cut their way through half the ship, swarming the Moorish fighting men like enraged bees. My men pressed forward and met our allies in the middle.

Where our ships had a single deck, galleys had two. They housed their fighting men on the top deck, and below, slaves powered their oars. Once we had cleared the top deck, I felt confident we had eliminated the threat. Slaves do not raid on their own accord. But they would make a good prize for us. We would be able to convince many to settle on the island—our salt farms needed the extra hands.

“Where is Ake?” Bjarki asked.

Ake’s ship had not kept pace with us. He had steered around in too broad a circle, and one of the galleys had maneuvered to aim its bronze ram at Riveted Serpent. How he had allowed it to happen, I am not certain. Before the Moors could catch him, his sail filled, and he dashed out of danger. At that moment, my leg started to ache.

“Damn,” I muttered.

“Damn is right,” Bjarki said. “Ake is too old and slow. I told you, Hasting. I told you.”

One of our men interrupted us, pointing in the opposite direction. “My king, look!”