C.J. Adrien's Blog, page 6

February 2, 2025

Le Casque Viking de Lejre – Un Aperçu Rare de la Royauté Scandinave

Des archéologues ont mis au jour des fragments d’un casque viking rare à Lejre, au Danemark. Cette découverte renforce l’idée que Lejre était un centre de pouvoir à l’époque viking. Les casques de cette période sont rares, ce qui rend cette trouvaille essentielle pour comprendre la guerre et le statut des élites scandinaves.

L’annonce a été faite par ROMU, l’organisation muséale en charge des fouilles. Selon le communiqué de presse officiel, le casque confirme l’importance historique de Lejre. « C’est une véritable sensation archéologique, » déclare Tom Christensen, responsable de la recherche chez ROMU. « Cela confirme le rôle de Lejre en tant que siège du pouvoir et nous apporte un nouvel éclairage sur l’aristocratie guerrière de l’Âge Viking. »

Mise au Jour des Fragments du Casque de LejreLes fragments ont été découverts sur le site de Lejre, souvent associé à la légendaire dynastie des Skjöldungar. Les archéologues y ont déjà mis au jour de vastes complexes de salles, interprétés comme des résidences royales. Ce casque s’ajoute aux nombreuses preuves suggérant que Lejre était un lieu de pouvoir viking.

Le casque est actuellement en cours d’étude pour déterminer sa forme et sa conception exactes. Bien que seuls des fragments subsistent, les premières analyses indiquent qu’il s’agissait d’un équipement de grande valeur, peut-être comparable au casque de Gjermundbu, le seul casque viking complet découvert à ce jour.

Les Casques dans le Monde Viking : Un Objet Rare et PrestigieuxLes casques vikings sont extrêmement rares dans les archives archéologiques. Contrairement aux épées, retrouvées en grand nombre, les casques étaient peu fréquents dans les sépultures. Le métal étant une ressource précieuse, il était souvent réutilisé. Il est probable que les casques étaient réservés à l’élite, ce qui rend cette découverte d’autant plus importante.

Dans mon article précédent, "Les Vikings portaient-ils des casques ? Rééxamen du sujet", j’explorais la rareté des casques vikings et les raisons possibles de leur absence dans les découvertes archéologiques. Cette nouvelle trouvaille renforce l’idée que les casques étaient des symboles de pouvoir plus que de simples protections de combat.

Lejre : Le Siège de la Royauté VikingLejre est considéré depuis longtemps comme un centre de pouvoir royal. Certains chercheurs pensent même qu’il aurait inspiré le Heorot Hall de la légende de Beowulf. Au fil des années, les fouilles ont révélé des armes, des trésors et des salles monumentales. L’ajout de ce casque renforce l’image de Lejre comme bastion du leadership viking.

Si le casque appartenait à un noble ou à un roi, il s’agit d’une preuve matérielle du leadership militaire viking. Il pourrait aider les historiens à mieux comprendre comment les chefs scandinaves s’équipaient et affirmaient leur statut.

Quel Avenir pour le Casque de Lejre ?Les chercheurs analysent actuellement les fragments pour en apprendre davantage sur la conception et la construction du casque. Il y a de l’espoir qu’une reconstruction partielle soit possible. Le casque sera probablement exposé dans un musée danois, rejoignant ainsi la courte liste des casques vikings connus à ce jour.

Conclusion : Une Découverte Majeure pour l’Archéologie VikingLe casque de Lejre confirme le rôle du site en tant que centre de pouvoir viking. Il apporte une rare preuve physique de l’armement de l’élite scandinave. Cette découverte remet en question certaines idées sur la guerre et le leadership viking.

Pour en savoir plus sur la rareté des casques vikings, je vous invite à lire mon article "Les Vikings portaient-ils descasques ? Rééxamen du sujet". Chaque nouvelle découverte éclaire davantage l’Âge Viking. Le casque de Lejre est une nouvelle pièce du puzzle permettant de mieux comprendre ces guerriers qui ont marqué l’histoire.

The Lejre Viking Helmet – A Rare Glimpse into Norse Royalty

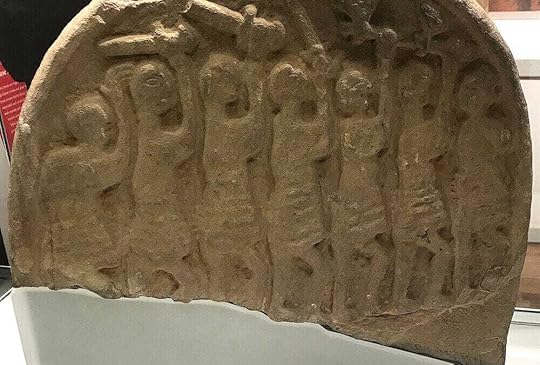

Photo credit: Kristian Grøndahl /ROMU

Photo credit: Kristian Grøndahl /ROMUArchaeologists have uncovered fragments of a rare Viking helmet at Lejre, Denmark. This finding strengthens the idea that Lejre was a center of power during the Viking Age. Helmets from this period are rare, making this discovery significant for understanding Viking warfare and the status of elite warriors.

The find was announced by ROMU, the museum organization overseeing the excavation. According to the official press release, the helmet confirms Lejre’s historical importance. “This is an archaeological sensation,” says ROMU’s head of research, Tom Christensen. “It cements Lejre’s role as a seat of power and gives us new insight into the warrior aristocracy of the Viking Age.”

Unearthing the Past: The Lejre Helmet FragmentsThe fragments were found at Lejre, a site linked to the legendary Skjöldung dynasty. Archaeologists have uncovered massive hall complexes here, believed to be royal residences. This helmet adds to the growing evidence that Lejre was home to Viking rulers.

The helmet is being studied to determine its full shape and design. While only fragments remain, early analysis suggests it was high-status armor. It may share features with the Gjermundbu helmet, the only complete Viking helmet ever found.

Helmets in the Viking World: A Rare and Prestigious ItemViking helmets are rare in the archaeological record. Unlike swords, which have been found in large numbers, helmets were not common grave goods. Metal was valuable and often reused. Helmets may have been reserved for the elite, making this find even more significant.

In my previous article, "Did the Vikings Wear Helmets? Revisited," I examined the lack of Viking helmets in the archaeological record. This discovery supports the idea that helmets were symbols of power rather than standard battle gear.

Lejre: The Seat of Viking RoyaltyLejre has long been considered a royal power center. Some believe it inspired the Beowulf legend’s Heorot Hall. Over the years, excavations have uncovered weapons, treasures, and monumental halls. This helmet adds to the picture of Lejre as a seat of Viking leadership.

If the helmet belonged to a noble or king, it provides physical evidence of Viking military leadership. It may help historians understand how Viking rulers armed themselves and displayed their status.

What’s Next for the Lejre Helmet?Researchers are analyzing the fragments to learn more about the helmet’s design and construction. There is hope that enough remains for a partial reconstruction. The helmet will be displayed at a Danish museum, adding to the small collection of Viking-era helmets known today.

Conclusion: A Monumental Find in Viking ArchaeologyThe Lejre helmet confirms the site’s role as a Viking power center. It provides rare physical evidence of elite Viking armor. This discovery challenges assumptions about Viking warfare and leadership.

For a deeper look at Viking helmets and their rarity, read my article, "Did the Vikings Wear Helmets? Revisited." With each new find, the Viking Age becomes clearer. The Lejre helmet is another step toward understanding the warriors who shaped history.

Don’t forget to buy my books!

January 25, 2025

Walking in Viking Footsteps: The Millennia-Old Secret Behind Modern Winter Traction

Horse ice grips from the Viking Age. (Photo: Olav Heggø / Museum of Cultural History)

Horse ice grips from the Viking Age. (Photo: Olav Heggø / Museum of Cultural History)Winter is upon us again, bringing a daily dance with icy sidewalks and snow-slicked roads for countless Americans. If you find yourself slipping microspikes or crampons over your boots, you might be intrigued to learn that you’re stepping into a longstanding tradition that includes the Vikings. Recent findings from Norway suggest that Vikings and early medieval Norwegians were using iron crampons, not unlike ours, to keep their footing firm on treacherous winter terrain.

Tested and True: Viking-Era Crampons in ActionA Science Norway article, “The Vikings also used crampons to avoid slipping on ice,” spotlights archaeologist and museum educator Espen Kutschera, who tested reconstructed Viking-age crampons in real-life conditions. Kutschera’s experiment was simple but effective: by strapping these spiked contraptions onto his shoes, he found that they made a clear difference on icy ground. Through these first-hand tests, he gained practical insight into how Vikings might have managed daily life in a much colder climate that might have been even more unforgiving than modern Norwegian winters.

The heart of these findings is that humans living in the Viking Age weren’t merely braving the elements without any aid. On the contrary, they had specialized gear that adapted to local conditions. According to Kutschera, it shouldn’t be surprising that traction aids appear in numerous Viking Age graves, revealing just how ubiquitous these devices may have been. The message is clear: crampons were your best friend if you needed to get around on ice during the Viking Age.

What Did Viking Crampons Look Like?We tend to picture Vikings with swords and ships, but these crampons, often small iron frameworks designed to be lashed to leather shoes, remind us of their more mundane and quotidian realities. While modern crampons frequently have multiple pointed spikes set into a steel or aluminum frame, Viking-era crampons could be more straightforward, with two or four carefully forged spikes. Some were shaped like small arches of iron designed to cradle the foot, while others may have been less uniform, reflecting local blacksmiths' skill (and style).

These iron devices could be tied or strapped under a traveler’s shoes. The exact placement of the spikes, as well as how snugly they fit, would have determined their effectiveness on ice. Modern testing (like Kutschera’s) suggests the historical models worked quite well, albeit with a bit of a learning curve for first-time users.

Ice, Snow, and Wooden BoardwalksDespite the typical stereotype of Vikings as perpetual raiders at sea, they spent much time traveling over land across mountains, along winding forest trails, and through towns that might have had wooden planks for walkways. In winter, those log walkways became as slippery as an ice rink. The newfound artifacts fill gaps in our understanding of how Norwegians coped with their rugged environment.

In many Viking Age settlements, wooden boardwalks or rough-hewn log paths were meant to keep pedestrians out of mud and slush when the weather was mild. Yet, these same surfaces became a hazard once temperatures dipped below freezing. It’s easy to see why the Vikings would have turned to iron crampons: just as we spread salt and sand on our streets today, they found methods to counteract ice. Fastening spikes beneath one’s shoes helped keep feet on the ground and bodies off it.

A Common Need, Even for HorsesThe Science Norway article also underscores that traction wasn’t solely a human necessity; Vikings also needed safe travel for their animals. Horses, critical for transporting goods and people, would have faced the same peril on icy terrain. The presence of traction aids in some archaeological contexts points to adaptations for horse hooves, mirroring the logic behind studded or spiked horseshoes. This practical reality stresses how important secure footing was not only for farmers and traders but for entire communities dependent on efficient, safe transportation of goods.

A Glimpse into Viking MindsetsSeeing these crampons appear in graves from the Viking Age underscores their significance. Objects placed in graves often held special meaning, sometimes to display a person’s social status and sometimes to ensure they had what they needed in the afterlife. The presence of crampons could imply that safe travel, even on the slickest surfaces, was woven into the fabric of Viking identity. It might also signal that these spikes were common and important enough that burying them alongside their owners made symbolic sense.

We don’t typically think of everyday survival gear as “treasured” artifacts, but their inclusion in burial contexts suggests that these seemingly mundane items were highly valued. After all, if an object helps prevent falls in a climate where a broken bone could be disastrous, it’s more than just a tool—it’s a lifesaver.

Bridging History and TodayFor those currently contending with icy sidewalks, knowing that Vikings faced and solved similar challenges may feel oddly comforting. Our modern crampons, fashioned from lightweight steel and designed with convenient straps or chains, may look more refined than the blacksmith-forged iron arcs of old. Yet the principle remains the same. Whether crossing a slick parking lot or traversing a frozen fjord, a few well-placed spikes can mean the difference between sure-footed progress and an unfortunate tumble.

While marveling at the Vikings’ sailing prowess or awe-inspiring raids is easy, examining something as practical as crampons reveal their broader ingenuity. The Vikings understood their environment, adapting to nature’s obstacles with resourceful inventions. We might joke that “people back then must have slipped a lot,” but artifacts like these show they weren’t content to let winter immobilize them, and they improvised and innovated.

Safe Travels this winterAs you head out in the cold this season, pulling on microspikes, Yaktrax, or any other traction aid, consider the long legacy you’re joining. Vikings and early medieval Norwegians faced harsh winters just as we do, and they tackled the ice head-on with their brand of technology. These excavated crampons, tested by experts like Espen Kutschera, speak volumes about the day-to-day ingenuity that has echoed through the centuries.

In a world that often focuses on monumental battles and epic voyages, it’s refreshing to zoom in on a humbler aspect of Viking life: staying on one’s feet in winter. From wooden boardwalks frozen solid to the slippery slopes of Norwegian fjords, the ancient Norse found ways to move forward safely—just as we do now with our traction gear. Whether then or now, the desire to walk without fear of falling on the ice remains universal—and the Viking-age crampons unearthed in Norway prove practicality can be just as impressive as any longboat adventure.

To check out the original article by Science Norway, CLICK HERE.

Don’t forget to buy my books:

January 20, 2025

The Viking Raid at Lindisfarne: An Inside Job?

The Viking Raid at Lindisfarne: Who Attacked the Monastery?

The Viking Raid at Lindisfarne: Who Attacked the Monastery?For centuries, the 793 A.D. raid on Lindisfarne has been shrouded in an air of terrifying immediacy: monks caught unawares, precious relics seized, and the blood of holy men staining an island sanctuary. Traditionally, this nightmare vision is pinned on marauding Vikings—Danes or Norwegians sailing across the stormy North Sea. Yet, as we comb through the sparse and often contradictory sources, another question emerges: what if the real plotters were not the foreign “heathens” but those with motives closer to home? In this article, I examine both the familiar narrative and the shocking possibility that Lindisfarne may have fallen prey to an “inside job,” revealing how one of the most iconic events in the dawn of the Viking Age remains far more mysterious than most realize.

What Happened at Lindisfarne:The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle notes:

“793. Here, terrible portents came about over the land of Northumbria and miserably frightened the people: these were period flashes of lightning, and fiery dragons were seen flying in the air. A great famine immediately followed these signs, and a little after that in the same year on 8 January the raiding of heathen men miserably devastated God’s church in Lindisfarne island by looting and slaughter.”

The speed at which the Vikings are said to have arrived caught the monks entirely by surprise. Reconstructions in past years have estimated that on a clear day, a ship might only be seen as far as 18 nautical miles, a little over an hour’s journey for a longship with the wind at its back. If the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is to be believed, the Vikings did not arrive on a clear day, and the monks did not appear to have had an hour to flee.

The monk Alcuin, a leading theologian of his day who was from York but resided at the court of Charlemagne, wrote a reply to his colleague Bishop Higbald of Lindisfarne to lament the event. The letter from Higbald to Alcuin, which we believe described the raid in detail, has not survived today, so Alcuin's reply is all we have to know precisely what happened. In his letter, he wrote:

“We and our fathers have now lived in this fair land for nearly three hundred and fifty years, and never before has such an atrocity been seen in Britain as we have now suffered at the hands of a pagan people. Such a voyage was not thought possible. The church of St. Cuthbert is spattered with the blood of the priests of God, stripped of all its furnishings, exposed to the plundering of pagans – a place more sacred than any in Britain.”

Alcuin’s description suggests that the clergy at Lindisfarne did little to flee their attackers. The Vikings may have arrived so suddenly that the monks had no time to prepare. That Higbald survived the attack, however, tells us the raid was not an outright massacre, and at least some monks escaped.

Although helpful in piecing together the events of the raid on Lindisfarne, Alcuin's letter offers nothing regarding who carried out the attack. Perhaps Higbald's letter contained more information that may have given us more clues, but we are not lucky to have his letter. The question remains: Who were the men who raided the island? Where did they come from?

The Case for the Danes:

The Case for the Danes:The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle lists an entry from the year 787 A.D., six years before Lindisfarne, describing ‘Danes’ who arrived at the port of Portland. It recounts a brief encounter in which the port authority was killed for attempting to levy a tax on “Danish men.” The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle reads:

“A.D., 787. This year King Bertric took Edburga the daughter of Offa to wife. And in his days came first three ships of the Northmen from the land of robbers. The Reve then rode thereto and would drive them to the king’s town; for he knew not what they were, and there was he slain. These were the first ships of the Danish men that sought the land of the English nation.”

The entry tells us the Danes had begun to eye the British Isles as early as six years before the raid at Lindisfarne. Given their proximity and relationship with Christendom, it would make sense that the Danes attacked the monastery in 793.

The political climate between the Danes and the Carolingians may have also contributed to inciting the first raid. In 792 A.D., Emperor Charlemagne moved to suppress a Saxon rebellion under the leadership of Widukind. His action was decisive and bloody. During the battle on the banks of the Elbe River, the Franks captured thousands of Saxon prisoners. As a means to send a message to the rest of the region, Charlemagne ordered the prisoners to be baptized in the river. There, the priests recited their benedictions as the Frankish soldiers held their victims underwater until they drowned.

The event, known as “The Massacre of Verden,” was entirely in line with Charlemagne’s tactics to subdue pagan tribes. Widukind, the leader of the Saxons, was brother-in-law to the king of the Danes, Sigfred. News of the massacre undoubtedly reached the Danish court, and word of Charlemagne’s acts of violence would have spread across Scandinavia. It was yet another brutal, violent display of power by the Carolingians, the latest in a long series spanning decades.

From what historians can tell from the sources, Danish raids along the coast of Frisia intensified almost immediately after the massacre, leading to an infamous attack on Dorestad in 810, to which Charlemagne supposedly bore witness if we are to believe the account given by the chronicler Einhart in his biography Two Lives of Charlemagne. Lindisfarne may have been a target precisely because of its importance in the Christian world. A source about the attack by the twelfth-century English chronicler Simeon of Durham, who drew from lost Northumbrian annals, described the events at Lindisfarne with precise details:

“And they came to the church at Lindisfarne, laid everything to waste with grievous plundering, trampled the holy places with polluted steps, dug up the altars and seized all the treasure of the holy church. They killed some of the brothers, took some away with them in feers, many they drove out, naked and loaded with insults, some they drowned in the sea..."

Some historians have taken this last passage to mean that the Vikings purposefully took priests to the water to drown them to demonstrate their retaliation against Christendom's encroachment on Denmark. Other historians have disputed this as a mere coincidence. If true, it might mean that the men who attacked Lindisfarne were indeed from Denmark.

The Case for the Norse (Norwegians):The evidence that leads historians to consider Norwegians were the ones to raid Lindisfarne resides in Alcuin's letter to Higbald. In it, he writes that the raid was a product of "a voyage not thought possible." Danes had already traveled to the British Isles, so the implication from Alcuin is that the ‘pagani’ who sacked the monastery had traveled from much farther away.

A late 10th-century chronicler, Aethelweard, who drew from lost contemporary documents, added a clue to the mystery. He suggested that the men who arrived at the port of Portland in 787 introduced themselves as men from Halogaland, Norway. His suggestion contradicts the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, which described the visitors in Portland as Danish men, but we must remember both histories were written long after the fact. Which chronicle is correct? It is difficult to say, but Aethelweard is widely considered unreliable as a source due to the strange and often incomprehensible structure of his Latin. Therefore, most historians believe the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle over Aethelweard's Chronicon.

The ‘Inside Job’ Theory:Although some light evidence suggests the Danes or Norwegians raided Lindisfarne, it is impossible to know who carried out the attack. It just as easily could have been a church conspiracy—an inside job—to incriminate the ‘heathens’ for a barbaric act to spur more considerable efforts to convert Scandinavia. One could say that Alcuin’s inconsistencies, such as his assertion that “such a voyage was not thought possible,” despite knowing that Norsemen had already visited Portland, point to a cover-up and overt effort to demonize them. Perhaps Alcuin, who was residing in Charlemagne’s court at the time, was the architect of a political hit job, and Lindisfarne was sacked by Frankish raiders under his orders—all so he could convince Charlemagne of the need to invade Jutland and force their conversion as had been done in Saxony.

All In Good Fun:Of course, the ‘inside job’ narrative is ridiculous, but it’s useful insofar as it showcases the nature of the study of the Vikings. Many significant events that marked that period—even well-documented and ubiquitously known events such as the raid at Lindisfarne—are based on light evidence and sparse, often unreliable primary sources. Therefore, to answer the question of who attacked Lindisfarne, all we can say is it was probably Danes, maybe Norwegians, but ultimately, we do not and cannot know for sure.

January 18, 2025

From Rusty Rivets to Digital Wonders: How Vikings Are Revolutionizing Archaeology

Archeologists using ground-penetrating radar

Archeologists using ground-penetrating radarVikings have long captured the imagination with their daring voyages, complex societies, and rich mythology. Yet, as we uncover more of their world, a surprising story emerges—not just about the Vikings themselves but how studying them transforms archaeology. By pushing the boundaries of traditional methods, Viking studies are driving cutting-edge innovations, with the excavation of the Gjellestad Viking ship standing as a prime example.

The Challenge of Fragile HistoryThe Gjellestad ship, discovered in southern Norway in 2018, is one of the most significant Viking finds in recent years. Using ground-penetrating radar, archaeologists located the remains of a Viking ship buried under a field. However, excitement quickly gave way to concern. The boat was in a severe state of decay, with wood and metal fragments so fragile that traditional excavation techniques risked destroying it.

Faced with this dilemma, researchers turned to technology to preserve and document what remained. The solution? Micro-computed tomography (µCT) is a noninvasive imaging technique that uses X-rays to create detailed 3D models of objects and their internal structures. For the Gjellestad excavation, this method marked a revolutionary step forward in archaeology. A groundbreaking new paper describes how the technique works.

How Micro-CT Works in ArchaeologyTraditional excavation methods often involve removing artifacts from their contexts, which can lead to damage or loss of critical spatial information. With µCT, archaeologists instead extracted soil blocks containing rivets and organic remains. These blocks were scanned to reveal their contents without disturbing the materials inside.

The µCT scans produced high-resolution 3D images, allowing researchers to examine the rivets, surrounding soil, and any additional artifacts embedded in the matrix digitally. This method preserved the objects and their precise positions, enabling digital reconstructions of the ship.

Additionally, the scans uncovered hidden details that would have otherwise been lost. For instance, previously undocumented rivets and structural elements emerged during analysis, contributing to a more complete understanding of the Gjellestad ship’s construction and layout.

Digital Reconstruction with GeoreferencingOne of the most innovative aspects of this project was the integration of µCT data into 3D GIS (Geographic Information Systems). Each soil block was georeferenced, meaning its exact location and orientation within the ship could be digitally mapped.

Using this data, researchers reconstructed the ship’s spatial relationships, rivet by rivet, in a virtual environment. As pieces came together, the form of the Gjellestad ship began to take shape, providing invaluable insights into its design and function. This digital model allows for "virtual re-excavations," enabling researchers to revisit the site without disturbing the physical remains.

Why Vikings Are Leading the WayThe Vikings’ enduring appeal is key in driving these technological advancements. High-profile discoveries like Gjellestad receive significant attention and funding, creating opportunities for experimentation with new methods. But the benefits extend far beyond the Viking world.

Non-Destructive Documentation: Techniques like µCT preserve fragile artifacts and materials for future study.

Revolutionizing Conservation: Digital models offer conservators a baseline to monitor the deterioration of artifacts over time.

Broader Applications: The methods pioneered at Gjellestad can be applied to other archaeological contexts, from ancient shipwrecks to burial sites in different cultures.

Impacts Beyond ArchaeologyThe Gjellestad project underscores how the study of Vikings influences fields beyond archaeology. Forensic science, for example, uses similar imaging techniques to analyze delicate evidence, while paleontology employs µCT to study fossils without damaging them. This cross-disciplinary exchange of ideas is shaping a future where technological innovation becomes the norm in cultural heritage preservation.

Moreover, digital reconstructions and open-access datasets democratize archaeology, making research available to scholars and the public. Imagine virtually exploring the Gjellestad ship from anywhere in the world or educators using these models to teach students about Viking history and technology.

The Future of Digital ArchaeologyThe Gjellestad excavation demonstrates that archaeology's tools are evolving. µCT, georeferencing, and 3D GIS are just the beginning. Emerging technologies like machine learning, augmented reality, and blockchain-based data storage could further enhance the precision and accessibility of archaeological research.

This is particularly exciting for Viking studies. From mapping burial sites to uncovering long-lost settlements, these innovations are shedding new light on one of history’s most intriguing cultures. In doing so, they remind us that the study of the past is as much about the future as it is about history.

Conclusion: Vikings as Catalysts for ChangeThe Vikings may have been early explorers, but today, they’re inspiring a different kind of voyage—one into the digital age of archaeology. Projects like the Gjellestad excavation showcase how cutting-edge technology is overcoming the challenges of preserving fragile history while opening new doors for research and education.

As we continue to study the Vikings, it’s clear that their story isn’t just about their daring exploits and longships. It’s also about how they’re leading the way in transforming archaeology, ensuring that the past remains a part of our future.

Don’t forget to buy my books!

January 17, 2025

Debating Harald ‘Bluetooth’: Are New Theories Dismissing the Dental Explanation?

Harald Bluetooth - Artist Interpretation

Harald Bluetooth - Artist InterpretationHarald “Bluetooth” Gormsson, King of Denmark (and, at times, parts of Norway) in the late 10th century, stands as one of the most notable Scandinavian monarchs of the Viking Age. While his political and military accomplishments receive due attention in medieval sources and modern scholarship, his epithet—“Bluetooth” (Old Norse Blátǫnn or Danish Blåtand)—continues to captivate the public imagination. Indeed, in a recent conversation with my co-host of the Vikingology Podcast, Terri Barnes, we discussed some intriguing new ideas that her students have brought up in class that they found circulating on the internet, which prompted this article. Over the centuries, various theories have emerged regarding its meaning, including a literal interpretation of a discolored tooth, a possible Gaelic-language connection through his father, Gorm, and the notion that “Bluetooth” may have referred to a weapon rather than Harald himself. This article examines these theories through a brief analysis of the primary and secondary sources, shedding light on the historical context and the scholarly debates surrounding Harald’s famous moniker.

Harald’s Place in HistoryHarald Bluetooth was the son of Gorm the Old (d. c. 958) and his queen, Thyra. He is credited with consolidating power in Denmark, extending influence over areas in Norway, and playing a significant role in the Christianization of his realm. Primary sources that discuss Harald include runic inscriptions—most notably the Jelling stones (often referred to as “Denmark’s birth certificate”)—and the writings of Saxo Grammaticus (12th–13th century), although Saxo’s Gesta Danorum can be interpretive and literary rather than strictly factual (Saxo, Gesta Danorum, c. 12th–13th century). Adam of Bremen (11th century) also provides information about Danish kings of the period but does not dwell extensively on Harald’s epithet.

The “Blue/Discolored Tooth” HypothesisA common and straightforward explanation posits that Harald had an unusually colored tooth—described as blue, dark, or otherwise discolored—that earned him the nickname “Blåtand.” The literal meaning is reinforced by the Old Norse and Danish words for “blue/dark” (blå/blár) and “tooth” (tand). This line of reasoning aligns with other Viking Age nicknames thought to refer to physical traits, such as Harald Fairhair (Haraldr hárfagri) or Eric Bloodaxe (Eiríkr blóðøx). However, historians have noted that such nicknames were not always as literal as they might appear (Sawyer 2000, pp. 84–85). For example, the sobriquet “Hairy-Breeches” associated with Ragnar (Ragnarr loðbrók) is highly contested; it may signify fur trousers or be a metaphor for some distinctive personal habit. Likewise, “Ivar the Boneless” (Ívarr inn beinlausi) presents a range of interpretive challenges, from physiological differences to metaphorical connotations of flexibility or cunning (Roesdahl 1987, pp. 150–151). In this respect, while Harald’s “Bluetooth” may indicate a physical characteristic, uncertainty persists.

The Gaelic Connection: Gorm = BlueThe father of Harald, known as Gorm the Old, bears a name that, coincidentally, resembles the Gaelic word gorm, meaning “blue” or “dark blue” (Old Irish, Scottish Gaelic). While this lexical overlap has fueled speculation—suggesting a Gaelic pun or a familial tendency toward “blue” designations—most scholars maintain this resemblance is fortuitous (Sawyer 2000, pp. 54–55). In a Norse context, Gorm was a relatively common personal name; the Gaelic meaning is likely incidental. Nevertheless, the correspondence between Gorm and gorm lends itself to modern interpretations that weave a possible Gaelic layer into the story of Harald’s nickname.

The Sword TheoryA less common hypothesis proposes that “Bluetooth” may have referred to Harald’s sword—potentially one with a notable bluish steel sheen or a distinctive name. Viking and medieval sources (e.g., Egils saga, Grettis saga) often mention swords with proper names—“Leg-Biter,” “Gram,” and “Skofnung”—and these weapons could themselves attain legendary status. However, no direct evidence exists in Gesta Danorum, the runic inscriptions, or other extant medieval sources that “Bluetooth” designated a sword (Roesdahl 1987, pp. 112–113). Historians who have surveyed Old Norse literature and material culture, such as Else Roesdahl and Birgit Sawyer, and contributors to the journal Viking and Medieval Scandinavia, do not attribute Harald’s epithet to a named weapon. Thus, while creative speculation persists, it remains unsubstantiated by primary sources.

The Role of Technology and Modern PopularityHarald’s name re-entered global lexicons in the 1990s when engineers developing a new wireless standard codenamed their project “Bluetooth.” Project participants chose the moniker because Harald united parts of Scandinavia, just as this technology aimed to unite different digital devices (Kardach 2008, IEEE, anecdotal references). The now-familiar Bluetooth logo merges the runes for H (Hagall) and B (Bjarkan) to visually reference Harald’s identity.

ConclusionHarald Bluetooth Gormsson’s epithet is a testament to the complexity of Viking Age nicknaming practices and the persistent allure of medieval history in popular culture. While many accept that a discolored tooth inspired the nickname, alternative explanations—such as the Gaelic overlap in his father’s name or the possibility of a famously “blue” sword—indicate the ongoing debates and fragmentary nature of medieval sources. Ultimately, the widely accepted viewpoint remains that “Bluetooth” referred to something about Harald personally, most likely a distinctive tooth. Yet, just as his father’s name, Gorm, presents a linguistic curiosity, Harald’s epithet continues to invite scholarly scrutiny and public intrigue alike.

ReferencesAdam of Bremen. (c. 1070). Gesta Hammaburgensis Ecclesiae Pontificum. Various editions.

Kardach, J. (2008). “Tech History: Creating the Bluetooth Name and Logo,” IEEE Global History Network(Anecdotal references).

Roesdahl, E. (1987). The Vikings. Penguin.

Sawyer, B. (2000). Medieval Scandinavia: From Conversion to Reformation, Circa 800–1500. University of Minnesota Press.

Saxo Grammaticus. (12th–13th c.). Gesta Danorum. Various editions.

Viking and Medieval Scandinavia (journal by Brepols Publishers). Various articles on Viking Age history, nomenclature, and culture.

January 15, 2025

Did the Vikings Really Make It as Far as Baghdad?

It’s a tantalizing idea: the fierce Norse adventurers who left their icy northern homelands to raid, trade, and explore, journeying to the heart of the Abbasid Caliphate—Baghdad. Imagine Viking merchants navigating the glittering bazaars of the Islamic world's greatest city, haggling over silks, spices, and silver under the golden domes of a metropolis renowned for its wealth and knowledge. It’s a story that captures the imagination and has been repeated in countless forms, from scholarly discussions to popular media. But did it happen?

The claim that the Vikings reached Baghdad hinges on intriguing evidence—written accounts, archaeological discoveries, and trade connections stretching across continents. Yet, as with many aspects of Viking history, the truth is unclear. Let’s dive into the evidence and unravel whether these legendary seafarers truly made it to one of the medieval world’s most dazzling cities—or if their connection to Baghdad is merely a myth woven into the tapestry of history.

The Case for Vikings Reaching BaghdadThe idea that the Vikings may have made it as far as Baghdad is rooted in both historical accounts and archaeological findings. While there is no direct evidence of Vikings in Baghdad, the circumstantial case is compelling enough to fuel speculation.

The Written EvidenceThe primary historical sources for Viking interactions with the Islamic world come from Arab writers who describe the activities of the Rus. The Rus are widely believed to be a group of Norse traders and settlers who established themselves along the river systems of Eastern Europe. These rivers, particularly the Volga, connected the Baltic Sea to the Caspian Sea, providing a direct route to the Abbasid Caliphate, whose capital was Baghdad.

One notable source is Ibn Khordadbeh, a 9th-century Persian geographer. He described the trade practices of the Rus, noting their journey from Northern Europe to the Caspian region. According to his account, these merchants transported furs, slaves, and other goods by river and overland routes, sometimes disguising themselves as Christians to facilitate their passage through Muslim lands. However, Ibn Khordadbeh does not explicitly state that the Rus reached Baghdad.

A more famous account comes from Ahmad ibn Fadlan, a 10th-century envoy from Baghdad who encountered the Rus’ during his journey to the Volga Bulgars. His observations of their customs, including the infamous description of a Viking funeral, provide invaluable insights into their way of life. Yet, like Ibn Khordadbeh, Ibn Fadlan does not place the Rus’ in Baghdad but documents their presence in territories north of the Islamic heartlands.

The Archaeological EvidenceArchaeology also supports the idea of trade connections between the Vikings and Baghdad, though not necessarily direct contact. The most significant evidence comes from the discovery of Abbasid silver coins, known as dirhams, in Viking-age Scandinavia. Thousands of these coins have been unearthed in hoards across Sweden, Denmark, and Norway, testifying to extensive trade between the Islamic world and the Norse.

Some of these coins date back to the 9th and 10th centuries, aligning with the height of the Viking Age. The sheer volume of dirhams found suggests that the Vikings played a significant role in the flow of goods and silver between East and West. However, the presence of these coins does not necessarily indicate that Vikings personally traveled to Baghdad. It is equally plausible that the coins changed hands multiple times through intermediaries before reaching Scandinavia.

Other artifacts, such as a ring inscribed with Arabic script found in a Viking burial at Birka, Sweden, hint at cultural exchanges. The inscription, which translates to "for Allah," is a tantalizing clue about Viking interactions with the Islamic world. But again, it does not confirm that Vikings ever stepped foot in Baghdad.

The Case Against Direct ContactDespite the suggestive evidence, there are reasons to be skeptical about the idea of Vikings in Baghdad. The most significant challenge to this claim is the lack of direct evidence. No Viking artifacts have been found in Baghdad, nor have contemporary records explicitly mentioned Vikings in the city.

The most likely scenario is that the Vikings operated as part of a broader trade network, with intermediaries—such as the Khazars, Volga Bulgars, and other regional powers—facilitating the exchange of goods between Northern Europe and the Abbasid Caliphate. These intermediaries may have carried goods to Baghdad on behalf of the Vikings or traded items that eventually found their way north.

Additionally, while the Rus’ are often identified as Vikings, the term encompasses a diverse group of people who may not have all been Norse. For example, the Rus’ of Ibn Fadlan’s account was a mix of Scandinavian traders, Slavic locals, and other regional inhabitants. This complicates the assumption that Vikings conducted all Rus’ trade activities.

The Romanticization of Viking JourneysThe notion of Vikings reaching Baghdad has been perpetuated partly by the popular fascination with their far-reaching travels. From their raids on monasteries in Britain to their settlement in Greenland and expeditions to North America, the Vikings have become synonymous with exploration and adventure. Adding Baghdad to their list of destinations fits this narrative neatly but risks oversimplifying their trade networks' historical realities.

So, Did the Vikings Really Make It to Baghdad?In the end, the answer remains elusive. The evidence suggests that the Vikings were deeply connected to the Islamic world through trade, and their goods indeed reached as far as Baghdad. However, the question of whether the Vikings physically traveled to the Abbasid capital remains unanswered due to the absence of direct evidence.

We cannot say they made it to the city without archaeological discoveries in Baghdad that can be definitively linked to the Vikings or explicit mentions of Viking travelers in contemporary Abbasid records. We know that the Vikings were active participants in a complex web of trade that spanned continents, and their interactions with the Islamic world were undoubtedly significant.

For now, the image of Vikings wandering through the bustling bazaars of Baghdad remains a tantalizing possibility—but one that, like many aspects of Viking history, is shrouded in mystery.

Want to read about Vikings traveling to the Middle East? Check out my latest novel:

January 14, 2025

Did the Vikings Create Trade Networks, or Just Steal Them?

Silver denier of West Frankish king Charles the Bald (AD 840-77) was found in Puddington. Photo Credit: Claire Downham.

Silver denier of West Frankish king Charles the Bald (AD 840-77) was found in Puddington. Photo Credit: Claire Downham.The discovery of three silver deniers from the reign of Charles the Bald in regions around the Irish Sea—Puddington in Cheshire, Llanbedrgoch in Anglesey, and the famed Cuerdale Hoard in Lancashire—may provide crucial evidence of a trade connection between the Irish Sea and the Bay of Biscay by the 840s, well within the Viking Age. Minted in Melle, France, these coins are tangible markers of a trade network that may have extended across disparate regions. Notably, the presence of one of these coins in the Cuerdale Hoard—a massive collection of Viking silver—strongly implies that this trade network would have at least been in part under Viking control by this period. This prompts an essential question: Did the Vikings establish this trade or co-opt an existing system that preceded their involvement?

We must examine the evidence for preexisting trade routes and cultural links to answer this. Irish-tradition monasteries, which spread from Ireland to northern France in the 6th and 7th centuries, played a pivotal role in early medieval contacts and commerce. These monastic centers, connected by a shared religious heritage and economic activity, may have served as hubs for exchanging goods such as manuscripts, wine, salt, and silver. Such a network would have predated Viking involvement, particularly in the Bay of Biscay region. These monasteries may not have been simple centers of faith but integral nodes in a more extensive trade system.

This context offers a plausible explanation for one of the Viking Age’s earliest mysteries: why the Vikings, after their initial raid on Lindisfarne in 793 and Iona in 795, leaped from the Irish Sea to the Bay of Biscay as early as 799. Noirmoutier, an island off the western coast of France, was the site of one of the first recorded Viking raids outside the British Isles. Why bypass closer and potentially richer targets, such as Frisia or Normandy? The answer may lie in the existing trade connections between Irish-tradition monasteries in Ireland and those in the Bay of Biscay. The shared monastic culture and their well-established trade network would have provided the Vikings with a clear roadmap, leading them directly to Noirmoutier, a significant hub for salt production and trade.

By targeting Irish-tradition monasteries, the Vikings may have exploited a preexisting network that was both economically valuable and geographically expansive. The raid on Noirmoutier in 799, just six years after Lindisfarne, may demonstrate that the Vikings were not merely raiding at random but strategically following well-trodden trade and communication paths. These same paths may have guided their raids and expansions deeper into France and beyond.

By the 840s, as evidenced by the coins found around the Irish Sea, the Vikings had gone beyond merely exploiting this network—they had co-opted it entirely. They integrated into the existing trade systems, controlling and profiting from the movement of goods such as silver, salt, and other high-value commodities. The silver deniers of Charles the Bald serve as markers of this transformation, revealing how the Vikings transitioned from raiders to power players in the economic systems of the early medieval world.

This reexamination of the evidence reframes the Viking Age as not solely an era of disruption but also an opportunistic adaptation. The Vikings did not build their trade networks in isolation; instead, they tapped into and eventually dominated systems laid down by others—particularly the Irish monastic communities. Their early raids on Lindisfarne, Ireland, and Noirmoutier highlight this strategic approach, where violence and commerce intersected to reshape the medieval world. The silver coins unearthed around the Irish Sea provide a glimpse into this complex and evolving relationship, marking the Vikings’ transition from outsiders to integral participants in a preexisting exchange network.

The Coin Finds: Mapping the NetworkThe silver denier discovered in Puddington, Cheshire, was unearthed in 1993 and is currently held at the Grosvenor Museum in Chester. This coin provides tangible evidence of the far reach of Carolingian silver into what is now northern England. Similarly, the discovery of an identical coin at Llanbedrgoch in Anglesey, found during excavations in the 1990s, is held by the National Museum of Wales. Llanbedrgoch is known for its Scandinavian connections, making this find particularly significant in linking the Irish Sea trade to broader networks. Finally, the inclusion of similar coins within the Cuerdale Hoard, discovered in 1840 along the River Ribble in Lancashire, now housed in the British Museum, adds another layer to this narrative. The hoard is one of the largest Viking-era silver hoards ever found, containing over 8,000 items, including ingots and coins.

Theories surrounding these findings suggest that the circulation of Melle-minted coins reflects robust trading activity between the Irish Sea and the Bay of Biscay during the Viking Age, likely centered on high-value commodities like wine, salt, and precious metals. These coins also hint at the integration of Viking trade into earlier networks established by monastic communities. While they do not directly prove monastic trade before the Viking Age, their presence strongly suggests a continuation and expansion of these routes, which Vikings may have exploited for commerce and raiding.

The Monastic Trade Network: Bridging the Bay of Biscay and the Irish SeaLong before Norse longships plied these waters, the Irish monastic network had laid the foundation for transregional exchange. Irish monasteries, known for their scholarship and missionary zeal, were among the most influential institutions in early medieval Europe. These religious centers spread Christianity and facilitated trade, acting as hubs of economic activity.

One key player in this network was the Monastery of St. Philbert on Noirmoutier, a small island off the coast of western France. Founded in the early 8th century by St. Philbert, this monastery was deeply rooted in the Irish monastic tradition of St. Columban. It thrived on salt production, a valuable commodity that became central to its trade activities.

Irish Monasticism and Its SpreadThe Columban tradition of monasticism, named for St. Columban, originated in Ireland and emphasized asceticism, scholarship, and missionary work. Irish monks, driven to spread Christianity, established monasteries across Europe. Luxeuil Abbey in present-day France was a notable center founded by Columban in 590. From Luxeuil, the Columban tradition radiated outward, influencing the foundation of numerous monasteries, including St. Philbert’s.

Irish monks brought with them not only their faith but also a culture of trade. Monasteries exchanged manuscripts, relics, wine, and other goods. The connection between Ireland and France was further cemented through these networks.

St. Philbert and the Irish ConnectionSt. Philbert’s story epitomizes the deep connections between Irish and Frankish monasticism. Born in the Frankish kingdom, Philbert followed the Columban tradition at Rebais Abbey, a monastery influenced by Irish practices. Inspired by Columban’s teachings, he established his monastery on Noirmoutier, blending Irish asceticism with Frankish monastic customs.

Noirmoutier’s salt production became a key economic driver. The Vita Philiberti, the saint’s hagiography, even records an instance of a ship laden with salt departing from Nantes, destined for Ireland. This small detail underscores the reality of trade between Noirmoutier and Irish monasteries, where salt was essential for preserving food and supporting local economies.

The Vikings and the Monastic NetworkBy the late 8th century, Viking raids began disrupting this network, but there is a strong argument to be made that the Norsemen initially followed the paths laid out by Irish monks. Monastic sites, rich in wealth and centrally located, were natural targets for Viking raiders. However, it is equally plausible that these routes guided the Vikings. The path from Lindisfarne to Ireland and then to the Bay of Biscay could have been discovered by Norse traders in the years preceding the first raids or followed by raiders, offering them access to established trade networks and resources such as Noirmoutier’s salt.

The raid on Noirmoutier in 799, just six years after the infamous attack on Lindisfarne in 793, suggests that the Vikings were not randomly targeting isolated locations but following a well-established trade and communication network instead. This early use of monastic trade routes may have given the Vikings a strategic advantage in their subsequent raids and expansions.

Rediscovering a Forgotten NetworkThe connections between the Irish Sea and the Bay of Biscay may not have been created by the Vikings but by Irish monks and their Frankish counterparts. These early medieval pioneers may have established a network that spanned seas and cultures through trade, scholarship, and missionary work, laying the groundwork for the interconnected world that the Vikings later exploited and expanded.

The silver deniers of Charles the Bald, the monastic salt trade from Noirmoutier to Ireland, and the spread of Irish monasticism all point to a vibrant exchange between these regions. By exploring these links, we can better understand the Viking Age and the centuries that preceded it.

As we continue to study these networks, it may come to light that many Viking trade routes may have been inherited (or stolen) from their monastic predecessors. It is a topic worthy of further exploration and one that figures prominently in my research, the precis of which I have shared in the article titled

The Viking Island.

January 12, 2025

Why Are There So Few New Viking Finds in France Compared with the UK and Scandinavia?

A recent conversation on the Vikingology podcast with Dr. Christian Cooijmans, author of Monarchs and Hydrarchs, raised an intriguing question: why are new archaeological finds related to the Vikings so rare in France compared to the UK and Scandinavia? Despite its rich Viking history, particularly in regions like Brittany and Normandy, France has yielded fewer discoveries than the U.K. and Scandinavia in recent decades. This disparity reflects historical differences and modern cultural and legal factors that shape archaeological practices.

Viking Activities in FranceThe Viking Age left a profound mark on France, particularly in the ninth and tenth centuries. Brittany, a region with deep cultural and linguistic ties to the Celtic world, became a frequent target for Viking raids due to its strategic coastline and access to key trade routes and resources (such as salt). Norse raiders established temporary bases and, at times, more permanent settlements, interacting with local populations in ways that influenced both groups. The Breton resistance to Viking incursions, as well as occasional alliances, adds complexity to this history. Normandy, named after the Norsemen, is the most well-known example of Viking integration, but Brittany’s role in this narrative is equally significant and remains underexplored archaeologically. In no uncertain terms, the experience of these regions of the Viking Age is no less than in neighboring England. Yet, there exists a significant disparity in the frequency of new finds.

France’s Archeological PotentialOne of the great strengths of France’s archaeological potential lies in its abundance of historical sources. Medieval chronicles, such as those by Dudo of Saint-Quentin, monastic records, and royal annals, offer detailed accounts of Viking raids, settlements, and interactions with local populations. In contrast to the UK and Scandinavia, which rely on fewer written sources often supplemented by oral traditions, France’s rich documentary history should theoretically guide archaeologists to more frequent and precise discoveries. Yet, despite this advantage, new finds remain elusive. This disconnect suggests that something beyond the availability of historical records prevents discoveries, pointing to modern practices and regulations—such as France’s strict limitations on metal detecting—as potential factors hindering progress.

Some Past Archaeological Finds of NoteFrance has produced notable archaeological finds, though discoveries in other regions often overshadow them. For instance, the ship burial site on the Île de Groix, excavated in June 1906 by archaeologists Louis Le Pontois and Paul du Chatellier, offers evidence of a broader and more permanent Norse presence. Similarly, the Camp de Péran, located in Plédran, Côtes-d'Armor, is a significant archaeological site in Brittany with a history of multiple occupations, including during the Viking era. The site, known locally as "Pierres Brûlées," was first studied between 1820 and 1825 by A. Maudet de Penhouët and F. Duine. It features remnants from the Iron Age, the Gallo-Roman period, and the Middle Ages, with notable fortifications attributed to Viking settlers. The site's strategic location and defensive structures suggest it served as a fortified settlement during the Viking occupation of the region. Despite these fascinating sites pointing to a wealth of potential discoveries beneath the surface of the French countryside, discoveries are infrequent, often constrained by a centralized and bureaucratic approach to archaeology.

French Archaeological Culture vs. the UKFrench archaeological culture contrasts significantly with the UK and Scandinavia, where private and public institutions often collaborate to fund and conduct digs. In the UK, archaeology benefits from a decentralized system that allows for a more flexible and responsive approach to exploration. Public engagement is also more pronounced, with initiatives encouraging amateur involvement. France, by contrast, centralizes archaeological oversight under state institutions such as INRAP (Institut national de recherches archéologiques préventives). While this ensures rigorous standards and heritage protection, it can also slow the pace of exploration and limit opportunities for non-professionals to contribute.

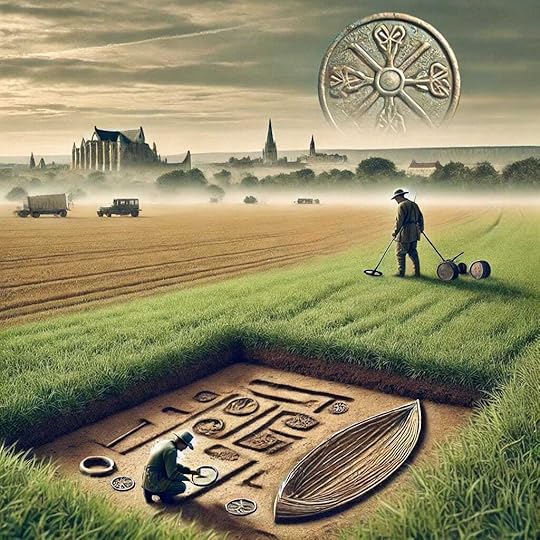

How Metal Detecting Has Bolstered Finds in the Anglophone World and ScandinaviaOne of the most striking differences lies in the role of metal detecting. In the UK and Scandinavia, metal detecting has played a transformative role in uncovering historical artifacts. Enthusiasts armed with metal detectors have made some of the most significant discoveries in recent decades, including hoards of Viking silver and Anglo-Saxon treasures. These finds often result from partnerships between amateur detectorists and professional archaeologists, creating a dynamic that blends citizen science with academic rigor.

During a visit to the island of Noirmoutier in 2019, I witnessed firsthand how modern tools like metal detectors and ground-penetrating sonar can complement traditional archaeology. A team sponsored by the local historical heritage group L’Association des Amis de Noirmoutier (of which I am a member) investigated whether anything new could be found at an existing Gallo-Roman villa site. Although the effort yielded no new artifacts, the potential was palpable. If regulated effectively, such technological approaches could open new avenues for discovery in France. Unfortunately, amateur metal detecting is illegal there.

Why Metal Detecting Is Illegal in FranceIn France, metal detecting is highly restricted. A 1941 law prohibits using metal detectors without explicit authorization, reflecting concerns about looting and the destruction of archaeological context. While these concerns are valid, the law has also stifled potential discoveries. France’s strict legal framework prioritizes heritage protection but limits public engagement in archaeology, leaving fewer opportunities for grassroots discoveries. All attempts to amend this law have come up short despite vocal groups' efforts to tap into France’s archeological potential.

What Can Be Done to Increase Finds in FranceSeveral measures could be considered to increase archaeological finds in France. Allowing regulated metal detecting, similar to systems in the UK, could harness public interest while safeguarding historical sites. Increased public funding for targeted digs, particularly in underexplored regions like Brittany, would address gaps in the current research. Educational initiatives promoting citizen archaeology could also cultivate a broader support base for archaeological projects. Finally, fostering international collaborations would bring fresh perspectives and methods to French archaeology, aligning it with international best practices.

ConclusionFrance’s Viking heritage remains an untapped reservoir of archaeological potential. Its historical depth, combined with modern advancements in technology and methodology, presents an opportunity to reexamine the region's Viking activity narrative. The disparity in discoveries between France, the UK, and Scandinavia is not merely a reflection of history but a result of how each country approaches the study of its past. France could uncover new chapters in its Viking story by balancing preservation and exploration, enriching our understanding of this fascinating era.

The conversation with Dr. Cooijmans reminds us of the value of interdisciplinary dialogue in revitalizing interest in archaeology. With a concerted effort, France could bridge the gap and reclaim its place as a center of archaeological discovery. Doing so would not only shed new light on the Vikings but also demonstrate how the past continues to inform and inspire the present.

January 11, 2025

Did the Vikings Wear Helmets? Revisited

The Gjerbundu helmet, found in Norway.

The Gjerbundu helmet, found in Norway.When I first tackled the question, “Did the Vikings wear helmets?” in a previous article over ten years ago, I explored whether Vikings wore helmets at all, given the surprising scarcity of Viking helmets in the archaeological record. The quick and easy answer from academia as to why there are so few helmets is and has been that they must have been items reserved for the elite. However, that proposition raises a significant question: if helmets were indeed reserved for elites, why are they so poorly represented when other elite items, like swords and ornate jewelry, are relatively abundant? Even among weapons, we have evidence of over 100 Ulfberht swords, allegedly forged by a single person and renowned for their advanced crucible steel construction. Yet, only two near-complete helmets from the entire Viking Age have survived. This striking disparity continues to challenge our understanding of Viking material culture, prompting debates about the near absence of helmets compared to the wealth of other war-related artifacts.

Two divergent camps have formed over whether the Vikings wore helmets. Some believe the Vikings did wear helmets and that the gap in the archeological record is a fluke. The other camp finds the lack of evidence in the archeological record telling. Perhaps the Vikings—the early Vikings, at least—wore no helmets. This article revisits the topic in light of renewed discussions and explores whether our understanding of Viking helmets has changed in the past decade.