C.J. Adrien's Blog, page 9

August 21, 2021

Viking Age Amulets May Have Represented Ritual Costumes, Not Gods and Heroes, A New Study Concludes

Denmark – A new study from Pieterjan Deckers, Sarah Croix & Soren Sindbæk released this month has proposed Viking Age amulets and figurines, once thought to have represented gods and heroes, instead express ritualistic costuming. The study authors analyzed various objects uncovered by archeologists in a Viking Age ceramics workshop found in the town of Ribe in Denmark.

As the study authors propose: “By highlighting iconographic and stylistic parallels with the tapestries of the Oseberg ship burial, we apply a novel perspective to the discussion of the armed woman motif and other Viking-Age figurative art. We argue that the common theme of the images is not the portrayal of heroic or mythological beings, but is instead ritual performance, in which women played a central role.”

While most of the amulets and figurines have not survived, the workshop in Ribe contained an assortment of molds that revealed the kinds of iconography produced there when examined with the help of advanced 3D scanners. Researchers discuss the iconography of a riderless steed, an armed woman, and a gripping man among the figures. All three share stylistic particularities that, when considered together, point to shared ritualistic use. The researchers’ conclusions are as follows:

“When viewed as an ensemble, the images from the Ribe moulds suggest themes of ritual rather than mythology. This conclusion is sustained by the stylistic and iconographic correspondence to depictions like the Oseberg tapestries. It is in this light that we should understand the apparent inversions in the images: the man gripping locks of his hair and the woman bearing weapons and armour, along with the full cast of miniature accoutrements: swords, shields, steeds and wagon wheels. As amulets and as part of female formal dress, these trappings harnessed the potency of ritual actions involving the transgression of social — especially gendered — norms. Depicting ‘ordinary men and women in extraordinary situations’, they highlight the central role of women in communal ritual and the importance of this prominence for female status and identity.

In remodelling inherited Nordic representations, the craftspeople of Ribe could draw inspiration from the heritage and visual culture of the Mediterranean past, which increasingly reached Northern Europe both in terms of the recycling of materials and in the re-appropriation of ideas borrowed from Classical myth, Christian legend and migration-period heroic tales. The urban networks of these emporia and the intersections between Scandinavia and the wider world of post-Roman Europe can be seen in the trade materials and adopted craft technologies arriving in Ribe. They were equally at the heart of the iconographic transformations revealed by the imagery of its amulet casting moulds.”

Read the full study here: Assembling the Full Cast: Ritual Performance, Gender Transgression and Iconographic Innovation in Viking-Age Ribe

C.J. Adrien’s TakeMy suggestion for you when reading the study is to pay close attention to the analysis of the armed woman. The researchers discuss the use of a helmet with cheek guards that, as far as we know, was not a style of helmet in use during the production of the amulets. The discussion also draws parallels to—and suggests a connection with—Roman iconography that, if correct, opens a whole host of possibilities as to the production and ceremonial use of the amulets.

The most important implication of this research is the conclusion on the role of women in ritual. Though the study authors make no direct connections between their hypothesis and the broader discussion of Viking Age warrior women, their conclusions support the idea that other archeological finds claiming to have found warrior women—or shield maidens/Valkyre—may not be what they seem. In particular, the so-called warrior woman from Birka that made headlines a few years ago may have been buried in a ritual style of dress akin to that represented in these amulets rather than as an indication of her living profession. Such an assertion is supported by the fact that the woman’s bones showed no signs of trauma common to the bones of male warriors, indicating she likely did not live a warrior lifestyle despite being buried with weapons and armor.

I look forward to seeing how this new study withstands peer review and where it may steer the discussion on the role of women in ritual and warfare in the future.

August 9, 2021

Recent Study Suggests A Grave in Suontaka, Finland Contained A Gender Non-Binary Viking Warrior

If you thought the discovery of a female Viking warrior a few years ago was controversial, wait until you hear about the gender non-binary warrior from Finland. An individual presumed to be a Viking Age Finnish warrior discovered more than 50 years ago in Suontaka, Finland, recently underwent new genetic tests to solve the decades-long mystery of why he was buried in women’s clothes. The tests revealed the individual had a rare genetic condition called Klinefelter’s syndrome. In Klinefelter’s syndrome, men have an extra X chromosome, sometimes giving them female physical features. Given the test results, the fact that the grave contained both female clothing and a warrior’s weapons, and the fact that the person buried must have held an important position in the community (such graves were reserved for the elite), the study authors have suggested the individual in questions may have been gender non-binary and accepted as such in their community.

A grave that raised eyebrows from the start

A grave that raised eyebrows from the startThe 1969 excavation of Suontaka uncovered a number of fascinating finds, including the now-famous bronze-hilted sword thought to have belonged to the person interred in the tomb. Archeologists also found a ring sword with silver inlays, a sheathed hunting knife, and a sickle placed on the body’s chest, objects indicative of a man’s grave. What caused them to scratch their heads was the additional discovery of a small penannular brooch, two oval-shaped turtle brooches with strands of woolen fabric, and a double-spiral chain, objects indicative of a woman’s style of dress.

The unusual combination of grave goods led archeologist Oiva Keskitalo to propose the grave had belonged to two people—a couple—rather than a single person. Keskitalo admitted the idea had a significant problem because the tomb had room enough for a single body. For lack of a better hypothesis, the double-grave idea stuck in academia. Still, detractors in the field asserted the tomb had contained a single body. Given the women’s clothing discovered therein, the tomb proved to many that women might have fought as warriors during the Viking Age.

A new Finnish study published on July 15, 2021, at Cambridge University Press has challenged both ideas.

Tests reveal the Suontaka Warrior may have had Klinefelter’s Syndrome.While most of the individual’s body had decomposed, archeologists did recover two small pieces of hip bone that they preserved for later study. A new group from Finland has put the bones to the test to determine the Suontaka warrior’s gender. What they found has created quite a stir in the academic community. The DNA tests, carried out in the archaeogenetic laboratory of the Max Planck Institute in Germany, revealed the individual buried in the Suontaka tomb might have had a rare chromosomal condition called Klinefelter’s Syndrome.

Each cell typically contains a pair of sex chromosomes—XX for women and XY for men—which determine a person’s sex. In Klinefelter’s Syndrome, men are born with an additional X chromosome. Most of the time, symptoms of the syndrome are so subtle that affected individuals do not know they are affected. In others, prominent feminine features such as gynecomastia (development of female breast tissue) and hairlessness develop. Affected individuals can also exhibit hypospadias (malformation of the penis), atrophy of one or both testicles, and delayed puberty.

“Based on current data, it is likely that the individual found in Suontaka had XXY chromosomes, although the DNA results are based on a minimal data set,” said Elina Salmela, post-doctoral fellow at the University of Helsinki and co-author of the new study.

The study authors suggest the Suontaka Warrior may have been gender non-binary.Given the mixed grave finds in the Suontaka’s tomb and the finding that the individual interred there was anatomically male but suffering from Klinefelter syndrome, the study authors have proposed the Suontaka Warrior may have been gender non-binary. Moreover, that the individual received such an elaborate burial denotes a person of importance within the community. Not only was this person potentially gender fluid, but they appear to have been accepted for it. The idea flies in the face of historical evidence that Viking Age Scandinavians were intolerant of people who did not fit the gender-role mold.

“If the features of Klinefelter syndrome had been evident on the person, they might not have been considered strictly female or male in the community. The abundant collection of objects buried in the grave is proof that the person was not only accepted but also valued and respected,” said Ulla Moilanen, a co-author of the study.

Because swords and jewelry cost a considerable amount of money, the authors agree that: “The individual may have been a respected member of the community because of his physical and psychological differences from other members of the community; but it is also possible that the individual was accepted as a non-binary person because he or she already had a distinctive character or obtained a position in the community for other reasons; for example, by belonging to a relatively wealthy and influential family.”

My take on the study’s findingsLike what we saw with the woman warrior’s grave in Birka, I see tremendous potential for the findings of this latest study out of Finland to appeal to modern audiences for modern cultural reasons. Claiming that the Suontaka Warrior may have been non-binary is a bold statement and incredibly biased toward our modern cultural lens. Of course, bias is inevitable. However, we must proceed with caution when making claims that so obviously cater to current cultural issues—in this case, gender issues.

Calling the individual gender non-binary or gender-fluid risks conflating the findings into something they are not. Was the individual considered non-binary (a term and concept that did not exist at the time), or just a man better in touch with his feminine side? Until a broader breadth of historians can examine the findings and interpret them within the broader historical context, we should be careful to avoid too much speculation.

The findings of the study are intrinsically fascinating. While the study authors admit their test samples were too small to make an absolute conclusion, their methodology was on point, so I believe it is fair to say primarily conclusive. It is a unique find that may help broaden historians’ perspectives on gender and social roles within Viking Age Scandinavian society. Now that the study has been published, it is up to leading historians in the field to work out the actual implications of the findings. That will take time, and until then, we should treat the study as it is: an exciting discovery with implications that are not yet fully known.

Read more about the study at the following links:

https://www.livescience.com/medieval-grave-non-binary-warrior-finland.html

July 27, 2021

Les Bátar, A French Group, to Build the Fastest Longship in the World to Sail to New York

Vikings are popular. Really popular. So hugely, immensely, unreasonably popular that their name (which isn’t even a word they used) and likeness (which is generally misrepresented) get tossed around in all manner of ways. People from Norway to France to the US have gravitated toward the Vikings and made them their own. A group in France who call themselves Bátar are no exception.

Bátar is a group of what I would call Viking enthusiasts who have made it their mission to build replica longships and sail them all over Europe. They are not the first such enterprise. Similar groups have emerged over the last century in Scandinavia, England, France, and even North America. Bátar’s first attempts at building longships were successful and took them to Denmark and Norway. Their new mission: to build the fastest longship in the world and sail it to New York.

Let’s start with the name of the group. Bátar is the Norse word for boats, plural. Those of you out there who know a smidge of French will recognize the name is a play on words. Batar in French means bastard. The group’s Twitter handle, “Les Bátars,” leaves no doubt the double entendre is intentional. Right off the bat, the group represents themselves in a semi-comedic fashion. When I first read about them, I thought they were a joke.

Looking into them further, I understood they have actually been quite successful in reaching their goals. Their comedic flare makes for good marketing, which has helped them raise the funds necessary to complete their projects. Several of the people on their team have academic backgrounds. The ships they have built to date are close approximations to the real longships of the Vikings. Against my initial suspicion, the group checks out as legitimate.

Bátar’s new mission—to sail from Toulouse to New York—has created a great deal of buzz in France. The group president has estimated the project will require more than two million euros to complete, and they are aggressively fundraising to make it happen. Will they succeed? Their track record says they have a good chance. I, for one, am rooting for them. Learn more about their mission on their website: https://www.batar.fr

Check out their latest promo video below:

July 2, 2021

How Did the Vikings Wear Their Hair?

Few images haunt the imaginations of schoolchildren more than the discovery in their history books of the Vikings’ mysterious longships, with carved dragon heads mounted on their prows, emerging from a morning fog on a desolate coast or river to prey on a still-sleeping village. The popular portrayal of the men aboard these ships harkens to a more primal likeness of humanity, one in which weather-beaten marauders with long, flowing locks of unkempt hair and immensely dense beards unleashed unimaginable ferocity on their victims for no greater purpose than to enrich themselves and to satisfy their carnal desires.

Modern revisions to Viking history have painted a starkly different picture of what life may have been like for Scandinavians during the Viking Age to the image popular culture has retained. We have since learned that they were cleanliness-oriented, bathed weekly, and paid particular attention to their appearance. We know that women decorated their clothes with colorful beads, jewelry, brooches, and hairpins, among other personal accouterments. The men groomed their hair and beards daily and may have worn eyeshadow. With all of this new information available to us, the question stands: how did the Vikings wear their hair?

Contrary to popular belief, long hair and a thick beard were not universal among those who betook themselves a-Viking. Long hair was a hazard during combat and challenging to keep clean during long sea voyages. Some historians have noted that short hair may have been reserved for slaves (more on that below). However, there is evidence to show that styles varied considerably among free individuals. Notable figures, some of them kings, chose to cut their hair short. Evidence from the archeological record, including statues, statuettes, and picture stones, shows men with various hairstyles. It appears that, precisely as it is today, hairstyles were likely a form of self-expression.

What is most important to understand is that the Viking Age lasted for over three centuries. In that time, fashion and hairstyles changed. Early in the Viking Age, the evidence does point to long hair and thick beards as the popular style. As time progressed, hairdos evolved, along with numerous other parts of Scandinavian culture.

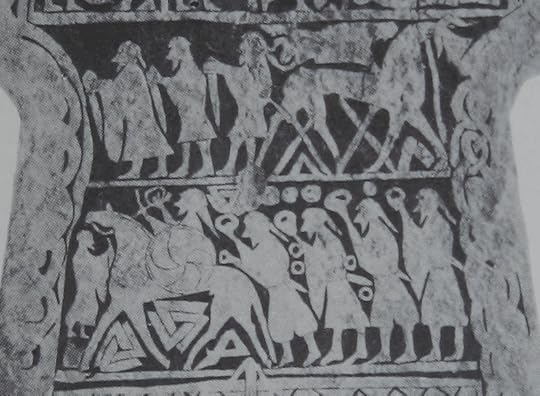

Early HairstylesThe evidence for early hairstyles points to variety. For example, the Tängelgårda stone (pictured below) depicts men with long hair and beards. Taking a closer look, a man on the lefthand side, below the horse, appears not to have long hair and is presumably a slave (although his actual status remains unclear).

the Tängelgårda stone

the Tängelgårda stoneThe Stora Hammers Stone (pictured below), one of the most famous relics of the Viking Age, also depicts different hairstyles. Some have long hair and beards, others short, and for others, it is unclear. Damage to the stone has obscured some of what we can see.

The Stora Hammers Stone

The Stora Hammers StoneA head carving from the Oseberg Ship Burial (pictured below), dating to the mid-9th Century, shows a man with a well-trimmed beard and a well-fitting coif, indicating that, for that man at least, long hair and a free-flowing beard were not his first choice.

A head carving from the Oseberg Ship BurialMid-Viking Age Evidence

A head carving from the Oseberg Ship BurialMid-Viking Age EvidenceBelow is a silver coin from Ireland depicting king Sihtric of Dublin, a notorious Viking who, on the coin, neither has long hair nor a beard. Oddly, Sihtric carried the name “Silk-Beard,” indicating he had, at one time, worn a well-kept beard but changed his style later in life (this assumes the nickname was a commentary on his beard, and not, as often was the case, a play on words).

a silver coin from Ireland depicting king Sihtric of DublinLate Viking Age Evidence

a silver coin from Ireland depicting king Sihtric of DublinLate Viking Age EvidenceBy the end of the Viking Age, the Christianization of Scandinavia lead to the imposition of rules around vanity. These rules may have contributed to the end of the varieties of hairdos among Scandinavians (for a while). Shifts in the Vikings’ military organization may have also played a role. The Bayeux Tapestry shows us that military men during this period wore short hair, particularly in the back (pictured below), without much variety.

The Bayeux TapestryHow did the Vikings Wear Their Hair?

The Bayeux TapestryHow did the Vikings Wear Their Hair?How did the Vikings wear their hair? The evidence points to a culture that allowed self-expression. Styles appear to have varied over time and across geographic regions. However, due to the sparseness of the evidence, we cannot say much more than that. Some had long flowing hair and beards. Others had short hair and shaved faces. Others still had all manner of varieties in between.

July 1, 2021

Did the Vikings Wear Makeup?

“Dear C.J., When I was little, my family stayed at a warrior reenactment camp, and one of the sections of the camp was a family who went ‘a-Viking. The woman was talking to me about her makeup. At the time, there was only discovered a brief mention that a woman or women had on what we today would call makeup. As a historian, she had to infer the rest to do this role-playing/reenactment. It would be cool to read about makeup and decorative flourishes worn and revered by people of that time.” – Rachel from Facebook.

Dear Rachel,

Where it concerns what we know about Viking Age Scandinavian personal styles and decorations, we can only speak with a relative amount of certainty to those things which have come up in the archeological record. Hard, durable items made of metal—such as brooches, necklaces, hairpins, and other personal items—survive the test of time far better than soft, organic materials. Makeup falls under the latter category. To complicate matters, the Vikings did not have an advanced writing system and are silent in the historical record. If all we had was evidence the Vikings left behind, we would have little in the way of evidence to answer the question of whether the Vikings wore makeup or not.

Fret not. Extrinsic evidence does exist, albeit peripherally.

To answer whether the Vikings wore makeup, we must first explore the broader topic of personal hygiene among Scandinavians of the time. In general terms, we know hygiene played an important role in the daily life of Viking Age Scandinavians; so much so that various sagas allude to a bathing day, which stands in stark contrast to the Christian cultures of the West at the time (an anonymous medieval cleric once wrote ‘the smellier we are, the holier we are’). Christian chroniclers in close contact with the Danes in England also allude to their cleanliness practices. John of Wallingford, prior to Saint Fridswise, expressed discontentment in his writings about how the Danes combed their hair, bathed every Saturday, and regularly changed their clothes.

On the other side of the European continent, the Arab chronicler Ibn Fadlan, who met the Rus (Swedish Vikings) on the Volga river, made a variety of interesting albeit odd observations about their hygiene habits:

“Every day they must wash their faces and heads and this they do in the dirtiest and filthiest fashion possible: to wit, every morning a girl servant brings a great basin of water; she offers this to her master and he washes his hands and face and his hair — he washes it and combs it out with a comb in the water; then he blows his nose and spits into the basin. When he has finished, the servant carries the basin to the next person, who does likewise. She carries the basin thus to all the household in turn, and each blows his nose, spits, and washes his face and hair in it.”

Historians generally discount the testimony at least in part due to the apparent negative bias infused by the author. However, the account does show that even on a long voyage so far from home, the Vikings still practiced some form of self-care and grooming.

Here is where Ibn Fadlan’s account gets interesting: he mentions men wearing eye makeup to make themselves appear more fearsome. If left alone, the detail might not inform us of much, but as luck would have it, it accompanies another element. Ibn Fadlan claimed they also wore blue tattoos. The topic of tattoos is controversial because, like makeup, skin does not preserve well in the archeological record. However, another chronicle from a wholly separate time, place, and culture confirms the observation. The Annals of Fulda describe Viking warriors who launched an invasion attempt on Aachen as having tattoos from head to toe.

Within the historical record, Ibn Fadlan’s testimony is the best evidence we have. It alludes to the use of eye shadow (but says nothing of women). But it does tell us that the Rus at least may have worn makeup. Thankfully, the historical record is not all we have.

Among the items uncovered in the considerable breadth of ship burials across Scandinavia and Western Europe, archeologists have found numerous household items we would recognize today but might not think of as ancient inventions: scissors, tweezers, brass washbowls, combs, ear spoons (not quite as comfortable as a Q-tip), among other personal grooming tools. In fact, the assortment of personal grooming items lends to the idea that Viking Age Scandinavians spent a great deal of time grooming and decorating themselves.

The Swedish National Museum’s collection has some of the more intriguing artifacts regarding the makeup question. The “grooming kit,” a collection of personal grooming items, includes a mortar that, with testing, showed a residue whose contents point to one thing: makeup.

Swedish National Museum Grooming Kit

Swedish National Museum Grooming KitWhile we cannot say with certainty that the use of makeup was widespread among Viking Age Scandinavians, we do have some evidence to suggest the practice existed among at least a portion of the population. As with most questions in regards to the Viking Age, we have here a maybe-probably-could-have-been answer. I think it was wise of the woman in the reenactment group to describe her use of makeup with caution. Both historical and archeological evidence is light at best, making for a somewhat anachronistic inclusion as part of her costume.

June 27, 2021

Buzz about Viking “Reunion” is Just That: Buzz.

It is always difficult to tell what new findings in Viking studies will make the rounds in mainstream media. Some of the most significant and impactful studies on our understanding of the Viking Age never leave the academic journals in which they are published, while other far more meaningless stories leap into headlines. A recent report about two supposed Viking relatives reunited as skeletons in Denmark shows there is often little rhyme or reason for why one story makes the headlines and others do not.

The story in question centers around a recent genetic test that revealed two skeletons from the Viking Age, one discovered in England and one in Denmark, belonged to the same family. One of the men died in his 20’s as part of a presumed massacre. Archeologists discovered his skeleton in 2008 at St John’s College at the University of Oxford as part of a supposed mass grave. The other appears to have died in Denmark in his 50’s in less violent circumstances.

The finding, while intriguing, offers little in the way of expanding our knowledge and understanding of population movements between Scandinavia and the British Isles in the late Viking Age. And yet, several major news outlets have reported on the findings citing Dr. Rane Willerslev, director of the National Museum of Denmark, as saying, “We thought that Vikings had left Denmark to live in Britain, but we were not certain. Now we had the evidence that they were kin.” Let us hope Dr. Willerslev’s statement was taken out of context.

The reality is that overwhelming evidence already exists to support the current consensus that significant population movements occurred between Denmark and the British Isles during the Viking Age, including modern DNA surveys, place names, and a wide breadth of historical and archeological findings.

What is more, the precise relationship between the two skeletons is unknown. The researchers admit that they have no idea if the two men were grandfather and grandson, uncle and nephew, or second cousins. They cannot even tell if they were alive in the same period or lived within overlapping generations. If the finding that the two men were “relatives” were our only basis for confirming Danes migrated into the British Isles at the end of the 10th and beginning of the 11th century, it would be dubious evidence at best.

All this is not to say the findings of the mass grave in Oxford are without interest or impact on our understanding of the Viking Age. That researchers discovered a mass grave of Danes in England promises all manner of potential findings on its own. But why does finding out that one of the skeletons happened to be loosely related to another skeleton in Denmark make it more newsworthy? We already knew the men in the mass grave in England were Danes. We’ve learned nothing new.

I understand the folks working at the National Museum of Denmark and their excitement. It is one more fun fact to add to the skeletons’ plaque to illustrate the broad impact of Scandinavian expansion into the British Isles. In no way do I want to minimize the importance of the finding to them. However, in terms of substance and newsworthiness, I find the whole story light on substance. It’s a fluff piece. Perhaps more about the two men will come to light in the future, and we may yet learn something new and profound from them. Until then, they remain a curiosity more than anything.

June 10, 2021

Two New Ship Settings Found on the island of Hjarnø, Denmark

An article recently published in The Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology by a group of researchers from Flinders University has proposed discovering two new ship settings at the Kalvestene grave field on the island of Hjarnø, Denmark. Researchers used medieval textual witness testimony of the gravesite by a man named Ole Worm to identify the new ship settings. The findings both affirm Ole Worm’s credibility as a historical source and opens the door to more potential finds at the site.

What is a ship setting?A ship setting is a style of burial that was popular in the early Viking Age in Scandinavia. Rather than bury a ship in the ground, as became standard later on for the wealthiest individuals, the dead had the likenesses of ships outlined with rocks around their graves. The image below of the two largest stone ships at Anund’s barrow in Sweden illustrates the scope and size some ship settings attained in a dramatic way.

Ole Worm’s 17th Century Drawings of The Kalvestene

Ole Worm’s 17th Century Drawings of The KalvesteneOle Worm’s 17th-century drawing of The Kalvestene (which translates roughly to “calf stones”) grave field included representations of more than twenty stone settings. Curiously, archeologists have found fewer than a dozen, leading many to question Ole Worm’s testimony. However, the recent study successfully used the drawings to find two more settings, opening the door to the possibility that, hidden in the ground, several more remain. It is a delightful confirmation that Ole Worm is, for the most part, a reliable source and an exciting proposition for archeologists who will continue to hunt for additional stone settings not previously found at the site.

Erin Sebo, lead author of the study, wrote of the discovery: “Our survey identified two new raised areas that could in fact be ship settings that align with Worm’s drawings from 1650. One appears to be a typical ship setting and the second remains ambiguous, but it’s impossible to know without excavation and further survey.”

If you want to read more about the study, CLICK HERE.

C.J. Adrien’s TakeIn the study of the Vikings, nothing is for certain. Contemporary sources pose all manner of problems for modern historians, and their credibility is often in question. Therefore, the work of historians is primarily to evaluate textual sources for their credibility and cross-reference information with other contemporary sources to confirm the likelihood of any one source’s authenticity. In the case of Ole Worm, we have here confirmation that his drawings are, most likely, a close representation of the gravesite in his time. In my opinion, the discovery is a more significant win for historians than for archeologists, as we have here a confirmation of a historical source’s credibility in conjunction with the archeological discovery of new ship settings.

April 1, 2021

Newly Discovered Icelandic Saga Confirms Contact with American Bigfoot

Reykjavik, Iceland, April 1, 2021

Ari Olafsson had no idea his family had kept an original Icelandic Saga book all these years. “It feels surreal. My grandfather never showed me this,” Mr. Olafsson says. “We think we have them all, but I guess there might be some others here and there, in people’s garages.”

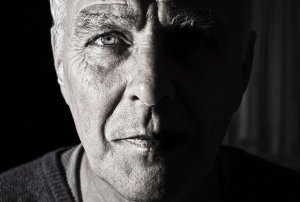

Ari Olafsson

Ari OlafssonOlafsson, appointed the executor of his grandfather’s will, made the discovery while sifting through a storage unit of the deceased’s belongings. Seeing the age and style of the document, he immediately submitted a request to the National Museum of Iceland to verify its authenticity. Museum curator of ancient texts, Magnus Magnusson, spent two weeks analyzing the artifact and concluded it is a lost Icelandic Saga.

At first, I thought it was a fake, but when the aging analysis returned and confirmed it was produced in the 13th century, we knew we had something special in our hands.

“It’s an exciting discovery,” Magnusson says. “At first, I thought it was a fake, but when the aging analysis returned and confirmed it was produced in the 13th century, we knew we had something special in our hands.”

Magnus Magnusson

Magnus MagnussonWhile a newly discovered Icelandic Saga is cause for celebration enough, what Magnusson found in the text proved even more exciting. The story told in the document speaks of a voyage to Vinland, in America, and of something so unusual, it caused the entire team of analysts pause.

“You know, we heard before in one document about the dark-eyed and hairy natives of Vinland, but we always thought it was about people,” Magnusson says. “In this story, they describe a man-like beast, half man and half bear, who lurks in the forest and steals children.”

When asked what creature he thinks the Saga is referencing, Magnusson said, “American Bigfoot.”

But then I read it, and it was there, clear as day. The Vikings saw Bigfoot.

“I don’t believe it,” says historian Bjorn Kjartansson at the University of Reykjavik. “Bigfoot? It feels like a joke. But then I read it, and it was there, clear as day. The Vikings saw Bigfoot.”

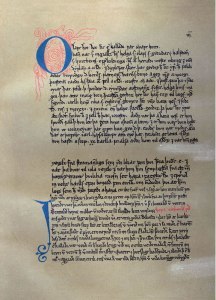

Newly Discovered Saga

Newly Discovered SagaMagnusson read for us the passage in question: “They roam the forests and watch us from the trees. They are not bears, and they are not Skraellings. The skraellings fear them and worship them, and they call them The Great Ones. The Great Ones have stolen two of our children, we believe to devour them. At night they howl like wolves to the moon. Some nights, they throw stones at our houses. Bjarni saw one clear enough one day. He saw a beast tall as a mountain and eyes black as night, with hair like a wolf’s mane covering its whole body. So horror-stricken was he, Bjarni took his family and his ship, and sailed from this place.”

“There’s more,” Magnus says, “but the translation needs work.”

When asked for further comment on the discovery, and whether his ancestors had seen the American Bigfoot, Ari Olafsson said, “I don’t really care, as long as I can make some money off of it.”

The implications of the new document are astounding. Did the Vikings encounter the famed Bigfoot in North America? Is Bigfoot to blame for the failure of the Vinland colony? Does it really steal children to eat them? Magnusson has vowed to continue his research and hopes to answer all these questions.

Article originally published on APRIL FOOL’S DAY!!!

The post Newly Discovered Icelandic Saga Confirms Contact with American Bigfoot appeared first on C.J. Adrien.

December 31, 2020

10 Viking Artifacts You Didn’t Know Existed

Most of the artifacts we encounter online and in history books focus on war: swords, shields, helmets, and other artifacts of warfare. Less focus is placed on everyday items, such as, interestingly enough, tweezers. Yet, everyday items offer us a far better glimpse into life in Viking Age Scandinavia than their weapons. The breadth of tools and items the Vikings used that mirror today is astounding. As far as we think we have progressed in 1,000 years, many things, such as telling our children not to run with scissors, have not changed. Here are 10 Viking artifacts you never knew existed.

Bronze Buddha

Trade was an essential part of Scandinavian civilization during the Viking Age. Objects from all over the world made their way back to Scandinavia, including this bronze statue of Buddha discovered in Sweden. Archeologists have dated the figure to the 6th century and believe it came from northern India.

Viking Age artifact found in Sweden of a Buddha statue from India. Photo credit: The Swedish History Museum.

Glass Pearl Necklaces

Personal style took a central role among Viking Age Scandinavians. Particularly in regards to jewelry, Viking Age finds have revealed a myriad of valuable objects, including this glass pearl necklace found in Gotland, Sweden. Glass was not readily made in Scandinavia at the time, and so the beads to make the necklace were likely imported.

Glass pearl necklace found in Gotland, Sweden. Photo credit: The Swedish History Museum.

Keys

With so many valuable objects, Viking Age Scandinavians devised many ways to protect their wealth. Locks and keys were common, and often resembled this key, found in Sweden. The key is made of bronze, a sturdy metal that does not rust like iron or steel.

Viking Age Bronze key displayed at the Chateau des Ducs de Bretagne exhibit. Photo credit: C.J. Adrien.

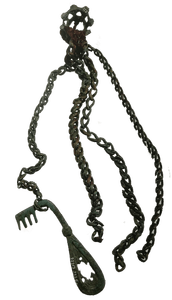

Keychains

With so many keys and no locksmiths a phone call away, Viking Age Scandinavians made keychains to organize and store their keys. Pictured here is a keychain attached to a brooch, which would have been worn by the head of the household. Women ran the home, and so they held all the keys.

Bronze keychain attacked to brooch. Photo credit: The Swedish History Museum.

Jewelry Boxes

Keys must open something. Pictured here is a jewelry box found in Gotland, Sweden. What makes this jewelry box so interesting is that it combines several motifs, including a combination of pre-Christian and Christian iconography. The box dates to the latter part of the Viking Age.

Viking Age jewelry box with Christian and pre-Christian motifs. Photo credit: The Swedish History Museum.

Iron Neck Collars

Slavery was central to Viking Age Scandinavian society. Proof of the use of slaves abounds, including this iron neck collar thought to have been used to keep a slave. Slaves were captured from all over the world and sold at markets across Scandinavia to allow farmstead owners to boost their labor supply.

Viking Age Iron Neck Collar as displayed at the exhibit at the Chateau des Ducs de Bretagne, Nantes, France. Photo credit: C.J. Adrien.

Urns

Funeral practices in Viking Age Scandinavia crucially differed from their Christian neighbors: where Christians buried their dead, Scandinavians cremated them. Except for the super-wealthy elite who could afford a ship burial, most of the dead were cremated and their remains stored in urns. Pictured below is an urn found in Sweden in which the ashes have (partially) remained preserved.

Viking Age Urn and Ashes. Photo credit: The Swedish History Museum.

Bronze Weathervane

Ships harnessed the wind to sail the seas, and no tool has helped sailors more over the centuries than weathervanes. Weathervanes help sailors determine the direction of the wind to help them set the sail correctly. Pictured is a bronze weathervane that would have been placed atop the mast of a longship. The weathervane shows Viking Age Scandinavian motifs and was likely made somewhere in Sweden.

Viking Age Bronze Weather Vane found in Sweden. Photo credit: The Swedish History Museum.

Scale

A crucial part of the Viking Age was trading, and part of the trade was currency. Most people are familiar with the more popular artifacts of Viking Age trade, such as Arabic coins, hack silver, and buried hordes. Wealth, however, had to be measured, and like other civilizations of the time, precious metals held their value by their weight. Pictured is a scale (without its plates) used to weight silver and gold.

A Viking Age scale (without its plates) used to weight silver and gold. Photo credit: The Swedish History Museum.

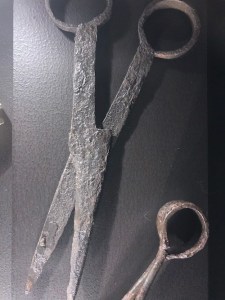

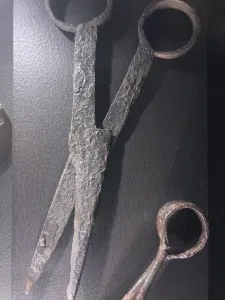

Scissors

Making clothes meant utilizing the various tools of the textile industry. Scissors were essential to cut fabric and to work over a variety of materials. Pictured are scissors found in Sweden and displayed at the recent exhibit at the Chateau des Ducs de Bretagne in Nantes.

Viking Age Scissors as displayed at the Chateau des Ducs de Bretagne in Nantes, France. Photo Credit: C.J. Adrien.

Bonus item: Grooming Kit

Grooming was paramount to Viking Age Scandinavians, and among all the things they used for personal care – combs, brushes, scissors, etc. – they also had tweezers for plucking unwanted hair and ear scoops to clean their ears. Pictured is a personal care display featuring many items from the Viking Age, including a pair of tweezers that are similar to those we use today (lower left), an ear scoop (lower right), and a few other items you might expect, such as a bronze bowl, combs, a brooch, and a makeup container.

The post 10 Viking Artifacts You Didn’t Know Existed appeared first on C.J. Adrien.

December 12, 2020

10 Viking Artifacts You Didn’t Know Existed

Most of the artifacts we encounter online and in history books focus on war: swords, shields, helmets, and other artifacts of warfare. Less focus is placed on everyday items, such as, interestingly enough, tweezers. Yet, everyday items offer us a far better glimpse into life in Viking Age Scandinavia than their weapons. The breadth of tools and items the Vikings used that mirror today is astounding. As far as we think we have progressed in 1,000 years, many things, such as telling our children not to run with scissors, have not changed. Here are 10 Viking artifacts you never knew existed.

Bronze Buddha “Archeologists have dated the figure to the 6th century and believe it came from northern India”

“Archeologists have dated the figure to the 6th century and believe it came from northern India”Trade was an essential part of Scandinavian civilization during the Viking Age. Objects from all over the world made their way back to Scandinavia, including this bronze statue of Buddha discovered in Sweden. Archeologists have dated the figure to the 6th century and believe it came from northern India.

Viking Age artifact found in Sweden of a Buddha statue from India. Photo credit: The Swedish History Museum.

Glass Pearl Necklaces

Personal style took a central role among Viking Age Scandinavians. Particularly in regards to jewelry, Viking Age finds have revealed a myriad of valuable objects, including this glass pearl necklace found in Gotland, Sweden. Glass was not readily made in Scandinavia at the time, and so the beads to make the necklace were likely imported.

Glass pearl necklace found in Gotland, Sweden. Photo credit: The Swedish History Museum.

Keys

With so many valuable objects, Viking Age Scandinavians devised many ways to protect their wealth. Locks and keys were common, and often resembled this key, found in Sweden. The key is made of bronze, a sturdy metal that does not rust like iron or steel.

Viking Age Bronze key displayed at the Chateau des Ducs de Bretagne exhibit. Photo credit: C.J. Adrien.

Keychains

With so many keys and no locksmiths a phone call away, Viking Age Scandinavians made keychains to organize and store their keys. Pictured here is a keychain attached to a brooch, which would have been worn by the head of the household. Women ran the home, and so they held all the keys.

Bronze keychain attacked to brooch. Photo credit: The Swedish History Museum.

Jewelry Boxes

Keys must open something. Pictured here is a jewelry box found in Gotland, Sweden. What makes this jewelry box so interesting is that it combines several motifs, including a combination of pre-Christian and Christian iconography. The box dates to the latter part of the Viking Age.

Viking Age jewelry box with Christian and pre-Christian motifs. Photo credit: The Swedish History Museum.

Iron Neck Collars

Slavery was central to Viking Age Scandinavian society. Proof of the use of slaves abounds, including this iron neck collar thought to have been used to keep a slave. Slaves were captured from all over the world and sold at markets across Scandinavia to allow farmstead owners to boost their labor supply.

Viking Age Iron Neck Collar as displayed at the exhibit at the Chateau des Ducs de Bretagne, Nantes, France. Photo credit: C.J. Adrien.

Urns

Funeral practices in Viking Age Scandinavia crucially differed from their Christian neighbors: where Christians buried their dead, Scandinavians cremated them. Except for the super-wealthy elite who could afford a ship burial, most of the dead were cremated and their remains stored in urns. Pictured below is an urn found in Sweden in which the ashes have (partially) remained preserved.

Viking Age Urn and Ashes. Photo credit: The Swedish History Museum.

Bronze Weathervane

Ships harnessed the wind to sail the seas, and no tool has helped sailors more over the centuries than weathervanes. Weathervanes help sailors determine the direction of the wind to help them set the sail correctly. Pictured is a bronze weathervane that would have been placed atop the mast of a longship. The weathervane shows Viking Age Scandinavian motifs and was likely made somewhere in Sweden.

Viking Age Bronze Weather Vane found in Sweden. Photo credit: The Swedish History Museum.

Scale

A crucial part of the Viking Age was trading, and part of the trade was currency. Most people are familiar with the more popular artifacts of Viking Age trade, such as Arabic coins, hack silver, and buried hordes. Wealth, however, had to be measured, and like other civilizations of the time, precious metals held their value by their weight. Pictured is a scale (without its plates) used to weight silver and gold.

A Viking Age scale (without its plates) used to weight silver and gold. Photo credit: The Swedish History Museum.

Scissors

Making clothes meant utilizing the various tools of the textile industry. Scissors were essential to cut fabric and to work over a variety of materials. Pictured are scissors found in Sweden and displayed at the recent exhibit at the Chateau des Ducs de Bretagne in Nantes.

Viking Age Scissors as displayed at the Chateau des Ducs de Bretagne in Nantes, France. Photo Credit: C.J. Adrien.

Bonus item: Grooming Kit

Grooming was paramount to Viking Age Scandinavians, and among all the things they used for personal care – combs, brushes, scissors, etc. – they also had tweezers for plucking unwanted hair and ear scoops to clean their ears. Pictured is a personal care display featuring many items from the Viking Age, including a pair of tweezers that are similar to those we use today (lower left), an ear scoop (lower right), and a few other items you might expect, such as a bronze bowl, combs, a brooch, and a makeup container.