C.J. Adrien's Blog, page 8

November 26, 2024

Vikings and Valkyries: When the Wolf Comes to Life

Fellow adventurers and saga-seekers, I am thrilled to announce my latest creative venture: Vikings and Valkyries, a live-action role-playing game podcast that melds the grandiosity of Norse myth with the rich storytelling of Ian Stuart Sharpe’s When the Wolf Comes. Imagine the captivating drama of Critical Role, but instead of the world of Exandria, we embark into the Vikingverse—a parallel timeline where the Norse gods still reign, and their people have ascended to the stars.

Helming this journey is none other than Ian Stuart Sharpe himself, the creator of When the Wolf Comes and our masterful game master. With his encyclopedic knowledge of Norse mythology and razor-sharp wit, Ian crafts a saga that is as enthralling as it is unpredictable. Under his guidance, we navigate the apocalyptic twilight of the Vikingverse, where every choice feels monumental, and every encounter teems with peril and opportunity.

In this epic saga, I have the honor of embodying Grjotgarð the Magnificent, a flamboyant Jöfurr whose larger-than-life personality is a cross between Lazlo Cravensworth’s eccentric vampiric charm and Zaphod Beeblebrox’s galaxy-sized ego. Grjotgarð isn’t just a leader; he’s a spectacle, a schemer, and a peacock in the most literal sense.

What Is When the Wolf Comes?If you’re new to this world, let me set the stage. When the Wolf Comes takes place in a Vikingverse where Ragnarök is an ever-looming shadow, threatening to unravel the cosmos. Players adopt roles as heroes—or anti-heroes—struggling to carve their destinies amidst gods, machines, and the enigmatic Yggdrasil, a sentient World Tree. The game blends traditional Norse mythology with science fiction, creating a world where ancient traditions clash with futuristic technology in an apocalyptic saga of fate and survival.

At its heart, When the Wolf Comes is about wrestling with the inexorable pull of fate, crafting tales of courage, tragedy, and triumph. The game’s mechanics encourage deep roleplay, collaborative storytelling, and moments of moral ambiguity—perfect for a podcast designed to entertain, provoke thought, and immerse listeners in a world of infinite narrative possibilities.

Meet Grjotgarð the MagnificentGrjotgarð is not your average Jöfurr. While most of his kin are known for their stoic honor and resolute leadership, Grjotgarð takes the path less traveled—or more accurately, the path most flamboyantly danced upon. Towering over most mortals (and some Jötnar), he is so massive that no horse can bear his weight, a fact he compensates for with a peacock-worthy wardrobe that ensures his entrance is always unforgettable.

Though he has no formal profession, Grjotgarð’s education is impeccable, and his tongue as sharp as his wit. A paragon of contradiction, he is equal parts intellectual and jester, delivering philosophical musings with the same gusto as he does his dramatic proclamations.

Grjotgarð’s crowning achievement (in his eyes) is winning the silver medal in the Toga Honk (Viking tug-o-war) at the All-Asgard Games. Though his second-place finish was technically marred by what some called "excessive preening," Grjotgarð himself prefers to attribute it to an unfair alignment of the Norns’ threads.

Grjotgarð the Magnificent’s journey begins (in episode 3) with a mission of utmost importance—or so he insists. He seeks a rogue Dvergar automaton rumored to contain information that, if revealed, could wreak havoc on... certain delicate matters of legacy. Enlisting the help of Err and Lomi, who claim to know the droid’s whereabouts, Grjotgarð’s plans are derailed when the trio is cursed by a mysterious Jötnar woman. Now bound by misfortune, they must uncover who ordered the curse—and why—all while Grjotgarð remains suspiciously vague about his true motives, deflecting questions with theatrical flair and dramatic sighs.

The character is a joy to play, blending the theatrical flair of Lazlo Cravensworth (What We Do in the Shadows) with the audacious confidence of Zaphod Beeblebrox (The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy). Beneath the feathers and bravado lies a genuine desire to protect and uplift his companions—though naturally, he prefers they thank him in sonnets and sagas afterward.

Meet the Cast of Vikings & ValkyriesSound the Gjallarhorn! The epic saga of Vikings & Valkyries has arrived, bringing together a dynamic cast of creators, historians, and storytellers. Each week, a revolving band of adventurers takes up their battle rifles and ventures across the World’s Edge, exploring the Thought & Memory Saga. With a mix of wit, grit, and occasional chaos, the choosers of the fallen (and their dice rolls) decide the fate of our ever-changing cast.

Music by: Table Top Audio

The Core Crew:Bill Hopkins (MagicLudi): A professional GM-for-hire on StartPlaying, Bill brings a wealth of experience to the table, running immersive campaigns with flair. You can find him on Facebook, Twitch, and YouTube to sample his style.

Steve Madill: A prolific science fiction and fantasy author, Steve has penned over a dozen books spanning three captivating series.

C.J. Adrien: An award-winning author of Viking historical fiction and co-host of the popular Vikingology podcast. Known for weaving history and myth with engaging narratives, C.J. takes the Vikingverse to new heights.

Special Guest Stars:J and his bandmates in Oba, who just dropped their debut single Could Have. Check it out on YouTube and Spotify.

Mike Foucher: The mastermind behind Shift, an app-integrated power browser that changes the game.

Joseph Aleo: Creator of the epic Vikings vs Samurai comic series, where legends clash in a battle for supremacy.

Joshua Gillingham: Fantasy author, game designer, and editor of the acclaimed trilogy The Saga of Torin Ten-Trees and the Althingi game.

Rebecca Hill: A dedicated Norse enthusiast, book blogger, and YouTuber with her channel Valhalla Conversations.

Sam Flegal: The creative force behind Fateful Signs, a collection of stunning Norse illustrations.

Jordan Stratford: Producer, author, and screenwriter celebrated for the Wollstonecraft Detective Agency series.

Each member of this ensemble brings their own perspective and talents, enriching the Vikings & Valkyries experience with humor, drama, and mythic storytelling. Join us on this saga as we explore the Vikingverse together—where heroes are forged, legends are made, and only the bold survive.

Why a Podcast?The medium of a live-action role-playing podcast allows us to bring this rich setting to life in a way that’s both intimate and expansive. The collaborative storytelling format lets the personalities of the players shine, while the episodic nature ensures a steady stream of cliffhangers, character growth, and dramatic encounters.

Through Vikings and Valkyries, Ian Stuart Sharpe orchestrates a world alive with gods, monsters, and star-faring Vikings. Together, we aim to transport listeners into the Vikingverse, where every decision ripples across the Nine Worlds. Will we stave off Ragnarök, or will our hubris hasten its arrival? The only certainty is that the path will be paved with glory, sacrifice, and the occasional ill-advised drinking contest.

Why Listen?If you’ve ever been captivated by the sagas of old or the theatrical storytelling of shows like Critical Role, Vikings and Valkyries promises to deliver an experience worthy of the mead halls of Valhalla. Whether you’re a seasoned gamer or new to role-playing, there’s something for everyone: intricate plots, dynamic characters, and a hearty dose of humor. Available everywhere podcasts are.

And, of course, there’s Grjotgarð—Magnificent by name, magnificent by nature.

July 12, 2023

The Vikings: An English Teacher’s Worst Nightmare?

Have you ever wondered why the English language seems to delight in breaking its own rules? It’s a puzzle that leaves both parents and teachers scratching their heads, while children often find themselves unsatisfied with the explanations they receive. As we delve deeper into the fascinating history of the English language, a surprising revelation emerges: the Vikings, those fierce warriors from Scandinavia that have modern popular culture enraptured, did far more than raid, pillage, and steal women. They also turned the English language on its head.

The Vikings: A Linguistic Tasmanian DevilPicture this: it’s the 8th Century A.D., and the Vikings, known for their daring voyages and plundering ways, set foot on the British Isles. What began as opportunistic raids soon turned into something more transformative. The Vikings gradually shifted their focus from pillaging to conquering, establishing dominance over a substantial portion of England. This period, known as the Danelaw, witnessed the widespread application of Norse laws to the local population. Remarkably, remnants of these laws can still be found in remote areas today. But the Vikings didn’t just leave their mark through their conquests; they also imparted their language upon the inhabitants of the British Isles.

The Vikings, hailing primarily from Norway and Denmark, introduced their linguistic traditions to the English-speaking populace, creating a melting pot of words and expressions. As a result, the roots of modern English began intertwining with Norse influences, forever altering the linguistic landscape. Moreover, the Vikings etched their names into the fabric of the British Isles through the distinctive place names they bestowed upon the land.

French-Speaking “Former Vikings” Turn the Language On Its HeadIn the year 1066 A.D., a new chapter unfolded in the saga of the English language. The Normans, descendants of the Vikings who had settled in a region called Normandy in France, launched an audacious invasion of England. Led by the renowned warlord William the Conqueror, the Normans brought a strict legal code known as Norman Law, executed in the French language. The French tongue introduced many new words and an entirely different grammatical structure to English. However, the Normans’ need to establish legitimacy among their subjects was what set the Norman conquest apart. To achieve this, they swiftly learned the local language, just as they had done with French. Within a few generations, a unique language emerged from this linguistic fusion.

The impact of these conquests reverberates through the English language to this day. Multiple words sprouted for the same objects and concepts, offering speakers a range of options for expressing themselves. Take, for instance, the humble pig. In its farming state, it was called “pig” or “swine” in the Anglo-Saxon tongue. Yet, once transformed into a savory dish, it assumed the name “pork,” borrowed from the French word “porc.” This linguistic phenomenon extended to numerous other examples, such as “chicken” and “poultry,” “deer” and “venison,” “snail” and “escargot,” and “sheep” and “mutton.” The Normans’ societal position resulted in French-rooted words becoming associated with the upper class. At the same time, Anglo-Saxon terms remained linked to the lower class. Consequently, the usage of fancier words in English often leans toward their French origins, although exceptions exist.

Not only did the Vikings and Normans introduce new vocabulary, but they also left an indelible mark on English grammar. The amalgamation of the more Germanic Anglo-Saxon language with the Latin-based French gave rise to the quirky grammatical exceptions that torment students today. At the close of the Middle Ages, a transformative event called the Great Vowel Shift occurred, bringing about further disparities in spelling and pronunciation.

But, Where There Are Challenges, There Are Also OpportunitiesEnglish, with its intricate tapestry of influences, presents an intriguing challenge. Yet, within this challenge lies its greatest strength. Its adaptability and flexibility make it one of the most versatile languages in the world. This malleability has allowed major industries, such as technology and science, to forge new vocabularies to describe their groundbreaking innovations. We owe a debt of gratitude to the Vikings for their part in shaping this linguistic wonder that we call English.

May 2, 2023

Where Did the Greenland Norse Get Their Timber? A New Study Points to North America.

Introduction: The Search for Timber in Viking SettlementsIcelandic archaeologist Lísabet Guðmundsdóttir from the University of Reykjavik Has Found Evidence the Greenland Norse Imported Timber from North America.

In 985 AD, the first settlers from Scandinavia arrived in Greenland, as told in the Saga of Erik the Red and other historical sources. These settlements, located on Greenland’s east and west coasts, endured harsh living conditions until they eventually disappeared around the 15th century. One of the biggest challenges the settlers faced was finding suitable timber for building houses and boats. According to the 13th-century Norwegian text Kongespeilet (King’s mirror), all iron and wood had to be imported to Greenland.

Investigating Timber Origins in Greenland’s SettlementsIcelandic archaeologist Lísabet Guðmundsdóttir from the University of Reykjavik sought to answer the question of where the Greenlanders got their timber by examining wood samples from various well-known settlements in Greenland. The study, published in the journal Antiquity, focused on sites such as Gården under Sandet (the farm beneath the sand) and the Eastern Settlement. The results confirmed that timber was imported from Norway, Northern Europe, and North America.

CONTINUE READING ON SUBSTACKApril 18, 2023

How Salt May Have Motivated the Vikings’ Westward Raids

Theories abound on what may have caused the Viking Age. From economic causes to social and political ones, historians and archeologists worldwide have put a great deal of energy into answering the question of why the Viking Age began. One of those theories centers on the idea that the Vikings left home in search of specific resources, such as enslaved people, wine, and salt, to remain competitive in a shifting economic landscape at home. No one argues that acquiring portable wealth–defined as easily transportable goods of value–was the end goal of those who left Scandinavia to rove in the early Viking Age. What is less clear is what kinds of portable wealth they valued the most and how much certain kinds of portable wealth might have motivated them to take the risk of sailing to faraway places to acquire it.

The Salt Hypothesis proposes that the Vikings’ early westward expansion–defined as the first thirty or so years of Viking activity in Western France and the British Isles–was driven mainly by one particular form of wealth that motivated them to travel farther and take greater risks than the others. As the title suggests, that form of portable wealth was salt. Unlike silver, enslaved people, and wine, which the Vikings could acquire closer to home, high-quality salt had to be acquired in southwestern France since the inland salt mines at Saltzburg were unattainable due to the Carolingian embargo on trade with Scandinavia.

In the following article, I will lay out the case for salt as a motivating factor for the westward diaspora. I will start by establishing the Viking Age Scandinavian need for, and lack of access to, salt. I will then explore the not-so-coincidental correlation between the Vikings’ earliest raids and the monastic trade networks present in France and the British Isles. Finally, I will discuss new research on establishing the herring trade in the baltic states that has breathed new life into the Salt Hypothesis and bring all the research into a cohesive narrative of salt’s role in the genesis of the so-called Viking Age.

As a former school teacher, I feel compelled to provide the following disclaimer for this article: This is not an academic paper; it’s a blog. While the material will feel academic (because I do publish academic papers) and is inspired by academic research, this article is meant for public consumption and entertainment. If you are a high school or college student looking to cite some of the material in this article, please get in touch with me first so I can help you with the material and citations you are looking to use. Those of you looking to dive deeper into this topic will find the bulk of my citations for my research in my selected bibliography.

History of The Salt Hypothesis

History of The Salt HypothesisAround 1946, the salt producers of the island of Noirmoutier in France went bankrupt. Soon, the entire industry collapsed. Today, that same salt production has seen a revival of sorts by local artisans looking to make a quick profit off tourists, but the commercial exports of the past have ceased to exist. Why did the salt industry in one of the most lucrative salt-producing parts of the world collapse in the middle of the twentieth century? Because Scandinavia, their primary market, developed refrigeration.

The sudden evaporation of the salt industry in the Southern Brittany region of France ushered in the end to two millennia of violent, bloody history over a resource that, until seventy-five years ago, was considered one of the most precious commodities in the world. Since Roman times, the island of Noirmoutier, though remote and hard to access, interested the various emperors, kings, clerics, and chieftains who controlled the region not for who lived there but for what they could make there. One such party was the Vikings.

The idea that salt may have attracted the Vikings to the region is well known. French historians have searched for decades for evidence to show that salt played a vital role in the Viking invasions of Western France and Brittany. Unfortunately, the dearth of archeological and textual evidence for a direct link between the salt trade and the Vikings has left them wanting. Although plenty of circumstantial evidence does exist, the absence of anything substantive has relegated the entire topic to the reliquary of Viking Age curiosities.

“10th century Vikings may have been attracted to the area [Noirmoutier] by the salt.”

Bergier, Jean-François, Une Histoire du Sel. Fribourg, Switzerland: Office du Livre, 1982. Pg. 116.

The Salt Hypothesis has its roots in a yet unsolved mystery. In 799 A.D., according to the monk Alcuin, the islands of Aquitaine—which includes the island of Noirmoutier—were attacked by pagans. Historians have debated ad infinitum whether these so-called pagans were Vikings or if they might have been Saracens from Spain. The modern consensus is that the pagans were Vikings, further reinforced by testimony from the monk Ermentaire, who chronicled the attacks in a later text. Thus started what the Breton historian Jean-Christophe Cassard called the Century of the Vikings in Brittany. For the next thirty years, the Vikings repeatedly raided the island of Noirmoutier for its monastery, Saint Philibert.

A letter written in 819 by Abbott Arnulf of Saint Philibert complained of “frequent and persistent raids.” They occurred so frequently that the monks who resided there fled to a satellite priory on the continent every spring and summer before returning in winter. Nowhere else in Christendom did the Vikings return at such regular intervals, which has begged the question: Why? What did they find so alluring about the island? Especially after the monks started to abandon it in spring, taking their portable wealth with them?

The most current and accepted theory is that Vikings were interested in the whole region, and the monastery of Saint Philibert was a convenient place to raid. Later, when the Vikings established a foothold on the outskirts of the city of Nantes in 853—a camp on the river island of Betia on the Loire—that may have been true. However, in the first thirty years of raiding, leading up to the definite abandonment of the island by the monks of Saint Philibert in 836, the Vikings had made little effort to raid inland. Hence, I argue, the monastery of Saint Philibert was likely a—if not the—target.

The Salt Hypothesis proposes that the Vikings returned to the island in spring and summer to raid for salt. They timed their raids to arrive in the peak salt-producing months to export it back to Scandinavia. The Salt Hypothesis further proposes that the Vikings’ need for salt significantly contributed to their westward expansion. Salt, the theory argues, was one of the significant contributing factors that shaped the genesis of the Viking Age.

Of course, attempts to define a single catalyst or trigger event for the genesis of the Viking Age have all proved unfruitful. The archeologist James Barrett called such attempts “unrealistic” in a 2010 paper. He proposed that the start of the Viking Age could only be defined by combining numerous factors into a broader, more general theory. The Salt Hypothesis does not claim that the exploitation of salt in France was anything close to a catalyst but rather a phenomenon that emerged within the context of other longue-durée causes. To learn more about these longue-durée causes, check out my article titled What Caused the Viking Age.

Trouble Brewing in the EastWhile Anglo-centric historians have defined the Viking Age as having started roughly in 793 with an event in England, recent scholarship has accepted that the Viking Age started much sooner in the East. A treasure trove of silver coins from the Muslim world found at Lake Ladoga gives us some idea of when contacts may have begun. As a standard practice in the Muslim world, coinmakers imprinted minting dates on their coins, and the coins at Lake Ladoga date to the 780s.

Primary sources for the early societal structure, culture, and activities of the Swedish Vikings, known as the Rus, are practically non-existent. They did not leave us any written sources besides disparate runes carved into wood planks or stones. One mention in the Annals of St. Bertin tells us of a diplomatic delegation from Constantinople that visited Louis I in Aachen in 839 that included Rus. Still, we have no other historical sources predating that mention. Thus, we must turn to archeological evidence.

Combined with further archeological evidence of pre-Viking Age colonies on the eastern shores of the Baltic, such as the Grobin colony in what is now Estonia, trade contacts between Sweden and the Middle East appear to have begun several decades before the Danes and Norwegians launched their first raids against the British Isles and France. Those early contacts appear not to have been violent, either. The earliest graves from the Grobin colony (pre-800s) include women and children, signaling a peaceful colonization effort, whereas later graves (mid-800s and later) contain fighting-aged men and their weapons.

Why the eastward expansion transitioned from trading to raiding remains a complex question with no precise answer. However, they may have been victims of their own success. Of all the longue-durée causes that contributed to the genesis of the eastward expansion and, by extension, the westward expansion, Søren Sindaebek’s synthesis on the role of the silver economy, urbanism, and the movement of durable goods as primary drivers perhaps has the best grasp on solving the mystery. Sindaebek and other historians have stressed at length the importance of the social bonds of the nuclear family, as well as the value of establishing familial ties, leading to a silver economy attached to the cultural practice of the bide-price. As Sindaebek wrote in a 2010 essay:

“My suggestion is, then, that a major motivation or affluent Scandinavian peasants to engage in long-distance exchange – and thus to enter into a silver economy – was that products acquired in this way could ease some of the most controversial issues of their social networks: the negotiations over the longterm status and personal property with which spouses, women in particular, entered into marriage. The incentive for trade and raids alike, I suggest, was ultimately driven by the hubs of family relations: by marriage and the negotiations or the families connected with it.”

Sindbæk, S. M. (2016). Urbanism and exchange in the North Atlantic/Baltic, 600–1000 ce. The Routledge Handbook of Archaeology and Globalization. T. Hodos, A. Geurds, P. Lane et al. Abingdon, Routledge.

If silver was a fundamental linchpin in the proper functioning of cultural practices that held together nuclear families, silver’s value was paramount to the fabric of society. Value, as economists insist, depends on supply and demand. Therefore, the amount of silver in circulation and its demand had dire consequences for the stability of Viking Age Scandinavian society. Where the supply and demand for silver had remained more or less constant in the two centuries leading up to the Viking Age, an increase in trade in the East threatened to unravel the delicate balance of pre-Viking Age Scandinavia.

Like the economic woes of the 16th century that resulted from the inflationary effect of Spain’s imports of gold from the New World, the influx of Islamic silver may have had a significant inflationary effect on the value of silver in Scandinavia. That effect would have had far-reaching consequences even in the most rural settlements. Given the role of silver in early Viking Age Scandinavian society, a sudden shift in the value of silver across Scandinavia may have threatened the most fundamental ties of the nuclear family.

In simpler terms, the bride price got too expensive (like housing today).

Following the Salt TrailIn the grip of rampant inflation, the amount of silver needed to afford the bride price may have grown out of reach for most men and their families–at least until the silver economy stabilized. Either these men had to find more silver or something of value to take its place—something valuable to the Rus, who, for obvious reasons, would not have wanted to trade silver for silver. Sindaebek further noted in his essay:

“The desires and ambitions, which led to the Viking expansion, were developed through generations of travel to distant markets, in search of things that would reset social balances and make social bonds more durable.”

Sindbæk, S. M. (2016). Urbanism and exchange in the North Atlantic/Baltic, 600–1000 ce. The Routledge Handbook of Archaeology and Globalization. T. Hodos, A. Geurds, P. Lane et al. Abingdon, Routledge.

When the first Viking raid occurred in England in 793 A.D., they had as their target a monastery. Monasteries were remote and ill-defended, and they owned precious metals such as silver. Historians have classically assumed the Vikings struck monasteries for their silver, which aligns with the silver hypothesis proposed by Sindaebek. Except, the closer we examine the early progression of Viking raids, the less sense it makes that silver was their intended bounty.

That first crew who raided Lindisfarne undoubtedly stole away with plenty of silver and portable goods, including enslaved people (as described by Alcuin and Simeon of Durham). Nevertheless, they never returned to that site, presumably because they understood the monastery would not likely replenish their silver for fear of a repeated raid. Alternatively, perhaps the Vikings did not acquire what they had hoped. Anglo-Saxon England was not silver-rich like the Byzantines and Islamic worlds, so the amount of silver they stole in the first raid may not have made economic sense. There is no way to prove it except to follow the trail of where they raided next.

Two years later, the monastery on the island of Iona, an island between Ireland and the island of Britain, succumbed to a Viking raid. Iona stands in contrast to Lindisfarne insofar as the Vikings did raid it again, but decades later. Again we have a case of a raid that did not lead to anything more than terrorizing the monastic world. Four years later, the Vikings made a straight shot for Saint Philibert on the island of Noirmoutier, off the coast of France. The progression seems curious. Ireland and, indeed, the whole of the British Isles had copious amounts of ill-defended and remote monasteries to raid. Why would a Viking expedition risk sailing so much further to France to raid the same thing?

Perhaps the Vikings thought a monastery in the Carolingian Empire might have more silver to plunder. If that were the case, we would expect to see that the first raid had remained an isolated incident. The problem is, we know that in that small corner of the Carolingian Empire, the Vikings returned time after time, almost annually, as related to us by the monk Ermentaire. Silver is not a renewable resource, and a monastery plagued by repeat attacks would have learned to keep their silver somewhere else, somewhere safe.

More curious, the chronicles tell us that after the monks abandoned the island in 836, the Vikings used it as a wintering base, and from detailed analysis of the salt trade in the Carolingian empire, we know salt production increased after they occupied it. The historian Michael McCormick, who specializes in the Carolingian salt trade, wrote in a 2001 article:

“Salt and bread were basic to life and to Carolingian commerce. The indispensable condiment and preservative is unequally distributed across Europe and has always figured prominently in early exchange systems connecting different ecological zones…Efforts of Carolingian institutions to buy the salt they needed help us to see it traveling by the boatload up the rivers of Frankland, and by the wagonload over its roads. Indeed, the thrifty archbishop of Sens decided to buy inland at Tours one year: rainy weather had driven up the price at Sens of salt from his usual supply source on the Atlantic coast, several hundred kilometers away.”

McCormick, M., F. G. P. M. H. M. McCormick and C. U. Press (2001). Origins of the European Economy: Communications and Commerce AD 300-900, Cambridge University Press. Pg. 698.

Hence, silver does not appear to be the focus of Viking raids and invasions in that part of the world (though they acquired plenty along the way). Their interest in the island of Noirmoutier persisted after the monks abandoned it, and the local production of salt continued to increase under their occupation. Given this evidence, salt looks to be the top candidate for what attracted the Vikings to southwestern France.

Establishing Demand for SaltThe Salt Hypothesis has had a major hurdle in demonstrating a demand for salt in Viking Age Scandinavia important enough to have made salt a primary motive for the Vikings’ westward expansion around the north of the British Isles, through the Irish Sea, and to Southern Brittany in France. As previously discussed, the inflationary effect of the influx of silver from the East required seeking out portable wealth to re-stabilize the economy and, more importantly, close social family bonds. Historians have traditionally cited monastic silver as the Vikings’ primary target and enslaved people as a secondary resource.

The problem with the idea that the Vikings sailed across the sea to loot for silver and enslaved people is that they could have done so with far less risk and much closer to home. We know they raided the Obrodites, the Frisians, and Slavs to the east as early as the 780s. Something else must have driven them further West, something they could not produce readily at home or acquire from their direct neighbors; something they needed more than enslaved people or silver—not for wealth, but for survival.

Since the dawn of civilization, salt has been a crucial resource. It is not a stretch to say there was likely a demand for salt in Scandinavia at the outset of the Viking Age. The question is whether a demand was strong enough to have inspired the first major raids in the British Isles and Western France. For that to have been the case, we would need to demonstrate a critical, life-sustaining need for salt far greater than the mere demands of day-to-day life.

Food preservation presents an enticing prospect for demonstrating a need for salt strong enough to spur the early Viking diaspora forward. Except, the primary fish they caught, so scholarship has insisted to date, was cod, which the Vikings dried. Hence, a greater commercial demand for salt to preserve their primary food staple hits a stumbling block. If the Vikings dried their fish, they did not need salt in the same quantities as they would need it in the later medieval period, which they used to preserve herring.

If Viking Age Scandinavians did not need commercial quantities of salt to preserve their food, what other activity might have driven its demand? Looking to the East, the Viking expansion up the freshwater river systems of Eastern Europe to Constantinople may offer us the justification we need. An obscure mention in the Saga of St. Olav gives us a clue that may help to demonstrate a high demand for salt. In the saga, St. Olav died in the land of the Rus and was preserved in a barrel of salt until his retainers could transport his body back to Scandinavia. The mention of a barrel of salt stands out.

The Vikings moving East, therefore, carried with them salt, ostensibly to preserve perishables while they navigated up the freshwater Volga and Dnieper rivers. Suppose the Rus moving East needed significant quantities of salt for their travels. In that case, their demand might have exceeded the production capabilities of Scandinavia at the time, requiring imports to meet their needs. The Carolingians, however, controlled all the major salt mines in continental Europe—most importantly, Saltzburg—and they restricted trade with Scandinavia starting in the 780s. We know from the sword trade that a black market moved goods across borders between the Carolingians and the Danes, but a black market salt trade may not have satisfied the demands of the Rus.

To this point, the Salt Hypothesis hits the ceiling. This is where it has lived since historians first started exploring the idea more than a century ago. It is where I have parked it since I started researching the topic over a decade ago. In speaking with other historians, I was advised to move on. And move on, I did. Until…

Cutting Down the Tree with a HerringA recent study out of Norway has given the Salt Hypothesis new life. In fact, it may have given the Salt Hypothesis the teeth it needs to stick in academia. The study concluded that the herring trade started around 800 rather than 1200, as previously thought. The implications of the study are dramatic. As previously discussed, the major hurdle the Salt Hypothesis had to clear was establishing clear commercial demand on a level that necessitated a westward expansion to satisfy it. Moreover, the study looked at sites on the baltic that would have belonged to the Rus and concluded that they traded significant quantities of herring in the east.

The sites the study surveyed dot along the eastward expansion of the Rus, denoting a high demand for the fish in Rus territories. Analysis of the herring bones strongly indicated the herring was caught in Norway and Denmark and made its way east by trade. It could be that the herring trade began as the commodity the Danes and Norwegians needed to balance out the influx of silver from the East. Except, they needed salt to make it work. Herring is a fattier fish than cod, meaning it cannot be preserved by drying but by salting. If the herring trade began at the outset of the Viking Age, the demand for salt it would have created would have far exceeded Scandinavia’s salt production capabilities at a time when the Carolingians restricted trade.

“The herring industry of the Baltic Sea supported one of the most important trades in medieval Europe,” Barrett says. “By combining the genetic study of archaeological and modern samples of herring bone, one can discover the earliest known evidence for the growth of long-range trade in herring, from comparatively saline waters of the western Baltic to the Viking Age trading site of Truso in north-east Poland.”

Atmore, L. M., Makowiecki, D., André, C., Lõugas, L., Barrett, J. H., & Star, B. (2022). Population dynamics of Baltic herring since the Viking Age revealed by ancient DNA and genomics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119(45), e2208703119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2208703119

It was a perfect storm. Islamic silver brought in by the Rus inflated the value of silver. Other groups, such as the Norwegians and Danes, had to exploit a new type of fish to offset the economic imbalance from the influx of silver. That new fish needed salt to preserve it. Scandinavia’s neighbor, the Carolingians, cut off trade to their salt mines. The next natural step is for the Vikings to go looking for salt.

It is unsurprising, given this context, that when the Vikings burst onto the scene in the West, they quickly and intentionally narrowed in on the salt-producing regions of western France and made a business of returning there year after year to exploit a resource they needed to keep their society together.

Returning to Sindaebek’s silver economy hypothesis, the phenomenon of seeking out salt would only have lasted as long as it took to stabilize the silver economy at home. Therefore, we should expect to see the interest in salt wane by the mid-800s and wane it did. The character of Viking activity in Western France–and indeed the Western world–took a dramatic turn in the middle of the century, shifting from sporadic, isolated raids to full-blown invasion attempts. A fresh set of economic, political, and social conditions motivated later expeditions and are not part of this article’s synthesis. The focus here is on the first thirty years of Viking activity in Western France and the British Isles.

The Monastic Trade NetworkAs previously discussed, the island of Noirmoutier has produced high-quality salt from water evaporation pools since Roman times. After the fall of the Roman Empire, Europe experienced several critical transitions. Among them, one of the most critical was the conversion of the Merovingians — a dynasty of Frankish warlords who conquered much of Gaul by the end of the 6th century — to Christianity. Their charismatic leader, Clovis, recognized the advantages of allying with the church and obligated his subjects to join him. The scene of his baptism stands as one of the most celebrated moments in French history. With Clovis on their side, the church expanded quickly across Western Europe and established abbeys and monasteries in every conceivable place the Merovingians would allow. Many of the monks who later earned sainthood lived during this period, including the namesake of the monastery and church at Noirmoutier-en-l’Île: Saint Philibert.

Saint Philibert grew up in the town of Vic in Southern France. His father was a well-respected magistrate and adviser to King Dagobert I. As was common then, his father convinced the king to find a place for his son at the royal court. Little information exists to describe Philibert’s time among the Merovingian nobility, but according to his biographer Ermentaire, he felt dissatisfied with his time among them and chose instead to dedicate his life to God and join the church as a monk. Perhaps he did feel the need to answer a higher calling, or perhaps he fell out of grace with others in the king’s entourage, a fact his biographer might have omitted on purpose. Whatever his reasons, Philibert received approval for his decision from Dagobert and sold all of his material possessions. For the next decade, he worked in various monasteries and, as far as we know, stayed out of trouble.

Around 650 A.D., Philibert had earned enough respect and clout within the religious community to set out on a long journey to study the teachings of other notable monks, including (as they are called today) Saint Basil, Saint Macaire, Saint Benoit, and most importantly, the Irish monk Saint Colomban. Philibert had, of course, as his intent to establish his own monastery and holy order of monks based on the accumulated wealth of their teachings, inspired by, and intent to embody the principles of Irish monasticism. By 654, he received a royal charter establishing his first abbey at Jumièges. As the first abbot of Jumièges, he imposed a particularly severe doctrine of austerity known as the Colomban Tradition. During his tenure, he fell out of grace with the Maire of the Palace of Neustria, Ebroïn, and had to flee for his life. Luckily, the bishop of Poitiers, Ansoald, who had admired Philibert’s work at Jumièges, offered him refuge in return for evangelizing his diocese in the St. Colomban tradition. Philibert evidently did fine work, and Ansoald rewarded him with land grants at Déas, in Herbauges, and on the island of Noirmoutier, then called Herio. On the island of Noirmoutier, Philibert founded the monastery that would take his name, and he died there on August 20, 684.

The religious order that took root after his death did not find its footing for several decades. During Charlemagne’s reign, it experienced at least two reorganizations ordered by the church and the Carolingians. It also never achieved full autonomy from the mainland nor developed into a leading intellectual center in the Irish monastic tradition as its founder had hoped. Various bishops, abbots, and other local lords sought to influence the monastery, some going as far as to live there semi-permanently to assert control. If the order had failed to gain dogmatic traction and ritualistic stability, why did it attract so many powerful figures? As is the case today, the main interest lies in the resource it controlled. By the late 8th century, Herio had grown into a major exporter of salt, a resource in high demand in the early medieval period. It is no surprise, therefore, that the lords of the surrounding region and religious leaders across the Christian world sought to capitalize on the island’s potential for wealth. Ansoald, it appears, did not fully appreciate the value of the land he had given to Philibert—or perhaps he did.

Philibert’s biography, Ermentaire’s Miracula (miracles), tells us of the widespread appeal of the island’s salt. Numerous mentions of ships from Brittany, Nantes, and, more importantly, Ireland indicate a thriving trade network that spanned the Western sea routes. A church document from the seventh century tells of a ship loaded with Noirmoutier salt destined for a monastery in Ireland. Given the heavy influence of the Saint Colomban tradition, the monks of Saint Philibert kept in contact with other monasteries in the British Isles founded on the principles of Irish monasticism. Those contacts would have included liturgical exchanges as well as moveable goods.

If salt from Noirmoutier had made its way to Lindisfarne, how would it have gotten there? It would have followed the monastic trade network from the island of Noirmoutier to Ireland, Iona, then over the top of the British Isles to Lindisfarne. If we follow that same trajectory in reverse, it mirrors the trajectory of the first Viking raids.

Telling the Story of the Salt HypothesisNorway, 793 A.D.

A small fishing village on the western coast receives a visitor. It is a trade ship from Gotland looking for salted herring to trade to the Rus. The village has herring but laments to the traders that they do not have the salt to preserve it. The merchant who supplied them with salt never showed (the Carolingians cut off trade with the Danes, putting him out of business). Soon, the Swedish ship moves on, disappointed. The village chieftain, Oskar, is disappointed, too, because he needed the silver from the trade to afford the bride price for the neighboring chieftain’s daughter to marry off his son.

Since the Rus started bringing back hordes of silver from the east, the bride price tripled. Oskar does not understand how or why that is, but he does know they use that silver to buy herring. If he cannot afford the bride price by the next time a Gotland ship arrives to trade, the neighboring chieftain may marry off his daughter to a rival, bringing him a risk of war. The chieftain, desperate to secure the social bonds to preserve peace, organizes an expedition to acquire wealth abroad.

Arrived in Lindisfarne, the chieftain finds a barrel of salt with large crystals indicative of an evaporation pool technique unavailable in Scandinavia. He questions the monks and takes some as slaves. Over time, one of those slaves learns the language, and the chieftain keeps him as an advisor. While the wealth from Lindisfarne more than afforded the bride price, the chieftain sees an opportunity. He organizes another expedition, this time with the guidance of his enslaved monk, who takes them along the monastic trade route, and raids Iona. Again, they find salt, leading the chieftain to ask where to find its source. The chieftain knows that if he can secure a steady import of salt to prepare his herring, he would make his people rich trading with the East. In 799, he finds Saint Philibert and its salt. From there, he starts the century of Vikings in Brittany, establishing a shipping lane back to Norway to supply the herring fisheries and, by extension, the eastward expansion of the Rus.

Concluding Remarks:The idea that salt was essential to the causes of the Viking Age is alluring. It helps to explain some of the enduring mysteries of Viking activity in southwestern France and Brittany, such as the frequency and persistence of the early raids.

Still, more work must be done to prove the connection between the Vikings’ early westward expansion and salt. Chief among those: more work needs to be done to show the movement of salt within the monastic trade network, which we don’t have.

Furthermore, while the herring bones found in the baltic have proven interesting, they would need to have been found with salt demonstrably from southwestern France for the Salt Hypothesis narrative to stick. Perhaps one day, the same team who discovered the herring trade started in 800 will look for signs of the salt used to preserve it.

There are other holes in this story, as I am sure several of you will be more than happy to point out in the comments section. But, the recent study on herring has helped reinvigorate my research and push forward this idea I have wanted to prove or disprove for so long.

A few years ago, I was invited to participate in a pitch for the Salt Hypothesis for a TV show. Below you will find a link to the video. It shows that I have been on this salty trail for some time, and the new evidence may help to bring the project back to life. At least, that is my hope. Thank you to those who have read this far. You are patient as saints! And until my next blog, cheers!

Link to the video VIKING ISLAND.

March 30, 2023

The 10 Best Viking History Books For Newbies

As a published historian, teacher, and author of historical fiction novels about the Vikings, I am often asked what books I recommend for people who want to start learning about the Vikings and the Viking Age. Here is a list of ten highly recommended history books about the Vikings, aimed at a general audience and perfect for those just starting to learn about the Viking Age.

Before diving into the world of Viking history books, it is essential to understand the context and significance of the Viking Age. The Viking Age, spanning from around 793 AD to 1066 AD, was a crucial period in European history, marked by the expansion and exploration of the Norse people from Scandinavia. Their legacy continues to captivate historians, archaeologists, and general readers alike.

During the Viking Age, these fierce warriors, skilled traders, and master shipbuilders sailed across the seas, reaching as far as North America, North Africa, and Central Asia. They established settlements, engaged in trade, and formed alliances with various societies, ultimately impacting the regions they encountered.

Viking history books offer readers the opportunity to explore this captivating era, uncovering its complexities and nuances. While the popular image of Vikings as ruthless raiders is indeed a part of their history, it is only a fraction of their story. Viking history books delve into a wide range of topics, from their extraordinary seafaring abilities and advanced shipbuilding techniques to their complex social structure, religious beliefs, and artistic expressions.

The study of Viking history also provides valuable insights into medieval Europe’s political and cultural landscape. As the Vikings interacted with diverse societies, they influenced and were influenced by the people they encountered. This exchange led to the spread of ideas, technologies, and cultural practices, shaping the development of Europe in significant ways.

By reading Viking history books, you will gain a deeper understanding of the Viking Age and discover the interconnectedness of the broader historical narrative. The Viking Age serves as a fascinating reminder of human societies’ resilience, ingenuity, and adaptability, showcasing the indelible mark left by the Norse people over the course of history.

So, whether you are a history enthusiast, a curious reader, or someone with a keen interest in the Viking Age, this list of Viking history books is the perfect starting point for your journey into the captivating world of the Vikings.

Viking History Books List“The Vikings: A History” by Robert Ferguson is a comprehensive account of the Viking Age, exploring their culture, society, and impact on Europe. This is my top pick for people just starting out on the subject.“The Age of the Vikings” by Anders Winroth is an engaging book that provides an overview of Viking history, focusing on the intricacies of their society and the factors that led to their rise and eventual decline.“The Norsemen in the Viking Age,” by Eric Christiansen, is an accessible albeit heady book that examines the overall impacts of the Viking Age on Scandinavia and the rest of Europe, emphasizing the thorough evaluation of the scholarly work that has informed our narrative for what happened.“The Children of Ash and Elm: A History of the Vikings” by Neil Price is a fascinating examination of Viking life, culture, and beliefs, shedding light on their rich and complex society.“Men of Terror,” by William Short and Reynir Oskarson, is an entertaining and informative guide to the mindset, beliefs, and battle tactics of the Vikings, offering an immersive look at their world.“Vikings: The North Atlantic Saga,” edited by William W. Fitzhugh and Elisabeth I. Ward, is a collection of essays and articles covering various aspects of Viking history, culture, and exploration, providing a comprehensive and engaging overview.“The Oxford Illustrated History of the Vikings,” edited by Peter Sawyer, is an illustrated volume that offers a detailed look at Viking history, with contributions from leading scholars in the field.“The Viking World,” by James Graham-Campbell, is a well-illustrated and accessible introduction to the Viking Age, providing an overview of their history, culture, and accomplishments.“The Penguin Historical Atlas of the Vikings,” by John Haywood, is an atlas that combines informative text with detailed maps and illustrations, offering a visual and engaging journey through Viking history.“The Norse Myths: A Guide to the Gods and Heroes,” by Carolyne Larrington, is a captivating exploration of the myths and legends of the Vikings, providing valuable insights into their beliefs, values, and worldview.These books offer a solid foundation for understanding the Viking Age, providing a range of perspectives on their history, culture, and society. They cater to a general audience, making them accessible and enjoyable for readers just starting out in their exploration of a time and place so often mythologized and misunderstood.

If you would like to learn more about the Vikings in other mediums, check out my podcast channel Vikingology: The Art and Science of the Viking Age.

July 7, 2022

Did the Vikings Wear Helmets?

It is a well-established fact among historians and archeologists that the Vikings did not wear horns on their helmets. There is no consensus, however, in regards to whether they wore helmets at all. A curious gap in the archeological record has led to a frustrating controversy in academia and reenactment circles alike. Until 2009, only one Viking Age helmet had ever been found, whereas archeologists have discovered countless swords, axes, shield bosses, and even ships. That so few helmets have ever been found begs the question: did the Vikings wear helmets? If they did, what happened to them all?

Two divergent camps have formed over the question of whether the Vikings wore helmets. There are those who believe the Vikings did, in fact, wear helmets, and that the gap in the archeological record is a fluke. The other camp finds the lack of evidence in the archeological record telling. Perhaps the Vikings—the early Vikings, at least—wore no helmets at all. The following are the arguments for and against.

The argument against Viking helmets:To date, archeologists have only recovered one Viking Age helmet in Scandinavia (pictured below). It dates to the 9th century and is named the Gjerbundu helmet. It is the most popular style of helmet reproduced for historical reenactment, and for good reason—it has no real competitors. Other items such as swords, axes, various articles of clothing, ships, and even maille have been more commonly found in Viking Age burials and dig sites, which has led many to question whether helmets were ever commonly worn by the warrior class of the time.

The Gjerbundu Helmet

In 2009, a mass grave in Weymouth, England thought to contain the remains of a massacred Viking army was advertised by the museum that put together the collection as having revealed a well-preserved helmet with an eyepiece uncharacteristic of Anglo-Saxon headgear. While the helmet has made the rounds on the internet as evidence of another example of a Viking helmet found in England, it turns out the helmet was a fabrication to put a jawbone into context. So, the only other Viking helmet ever found is a fake.

In the last few decades, a spattering of helmet fragments have been found, but they are too incomplete to be helpful in the discussion. Some will argue that helmets were re-smelted and reused for other things, which might explain their rarity. This argument holds little merit considering the metal from many other commonly found metal artifacts would make for much easier repurposing, but we still find plenty of those in the ground. The fact that helmets are such a rare find is a strong indication that, at the very least, iron helmets were not commonly made or utilized. Until more artifacts are found, the presumption should be that Viking Age Scandinavians did not commonly wear helmets.

The argument for Viking helmets:The lack of archeological specimens of helmets does not necessarily indicate that they were not commonly used. Metal was in high demand in the Viking Age, and even more so later in the medieval period. Quality metals, such as those found in helmets, may have been melted down, refined, and repurposed, which may help to explain the lack of helmets in the archeological record.

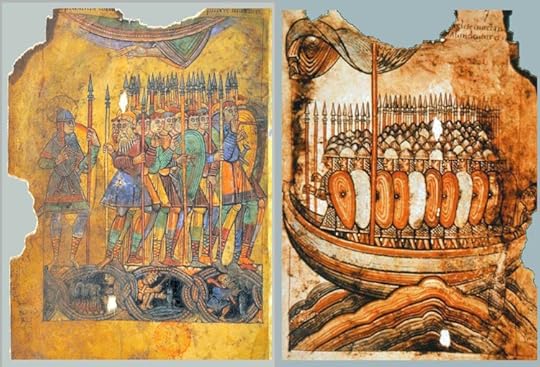

There is evidence in the historical record, such as in the representation of a Viking attack on Guérande in the Miracles of St. Aubin (pictured below), that the Norsemen did wear helmets. Helmets are also mentioned in the sagas as being important and valuable possessions for warriors.

Vikings attack Guerende, from the Miracles of St. Aubin

Vikings attack Guerende, from the Miracles of St. AubinA couple of picture stones from the Viking Age also appear to show warriors in helmets. The Stora Hammars Stone in particular represents men with conical heads, which many believe to show helmets.

We also know that helmets were commonly used in Scandinavia before the Viking Age. Archeologists have found several helmets from the Vendel period in Sweden, around the 6th century, which bear a striking resemblance to the Sutton Hoo helmet dated to the same period. It is unlikely that Scandinavians of the Viking Age would have regressed so far as to give up on helmets. The technology was there and coupled with the artifacts we do have, and the historical and hagiographic record, we can say that the Vikings, at least the wealthy ones, did wear helmets.

Who is right?

There is not enough information to give a definitive answer. A lack of helmets in the archeological record poses a particularly perplexing argumentative problem because it neither proves nor disproves the widespread use of helmets by the Vikings. Those who argue against the widespread use of helmets will never be able to prove they weren’t used. This problem is further compounded by artistic representations by chroniclers from the time whose artwork may or may not be accurate. Short of a lucky find of a mass grave containing numerous helmet-clad warriors, we may never know for sure. Thus, for now, all we can really say is that we don’t know, but one person in Gjerbundu, Norway, at least, wore a helmet!

June 24, 2022

Did the Vikings Raid in Spain? A Brief History of the Spanish Experience of the Viking Age.

The Vikings traveled far and wide. No place in Europe with a coast or river, it seems, escaped their influence. While most media focuses on the English experience of the Viking Age–the Anglophone world tends to be anglo-centric, after all–we have a great deal more we can learn by looking at the other areas the Vikings roved. Spain’s experience of the Viking Age stands to teach us a great deal because Muslims occupied the Iberian peninsula and their chroniclers offer us a fresh perspective on the Vikings and their raids.

Spain During the Viking AgeIslam spread quickly across the southern Mediterranean Basin during the life of its prophet Muhammad and even faster after his death. Under the Umayyad Caliphs, their territorial expansion created an empire that bordered China in the East and the Atlantic Ocean in the West. The Abbasid Caliphs, who rose to power to replace the Umayyads, took a particular interest in the arts and sciences, with an immense fascination for Hellenistic (i.e., Ancient Greek) and Persian history and culture. Their infatuation led to a cultural revolution, which influenced the writings of the leading Islamic scholars of the day. Significant scientific advancements in cosmology and mathematics occurred throughout the 7th and 8th Centuries.

The Islamic empire had an advanced postal system to relay information across the vast expanses of their territory. It connected the empire’s furthest reaches with its administrative center, Baghdad. The Islamic world kept track of the lands they conquered through the postal system. One group of people, in particular, gave them cause for concern and feature prominently in the primary sources. These were the Vikings. Arabic writings of the time referred to the Vikings by two names: ar-Rus and al-Madjus.

The name ar-Rus described the Swedish Vikings who navigated the Dnieper and Volga rivers and whom the Muslims encountered on the shores of the Black Sea. The name al-Madjus described the Vikings in the West, those who terrorized the coasts of Ireland, France, and Spain. Arab scholars used the name al-Madjus to describe the culture of the Vikings as they perceived it: a culture of fire-worshipers. They likened the al-Madjus to the Persian Zoroastrians, both of whom cremated their dead. The thirteenth-century chronicler Ibn Said explained, “nothing seems more important to them than fire, for the cold in their lands is severe.”

The Muslim Sources and Some of Their ChallengesContemporary Muslim sources present a similar challenge to their Christian counterparts. The sources historians have to work with are a mosaic of reconstructed documents written decades and centuries after the fact. The first chroniclers, such as the historian Ahmad al-Razi, his son Isa-ibn-Ahmad, and the scholar Ibn al-Qutyyia, have no surviving works to draw upon for study. We know their names and their stories because later chroniclers reference them. As historians must do with Christian sources with the same problems, they must cross-reference any referencing to the Vikings and their activities with other disparate sources.

The two most authoritative surviving works about the early attacks on Spain were written by the 10th-century scholars Ibn Al Qutiyya and Ibn Hayyan’s Al Muqtabis. Christian sources, chiefly the Annales Bertinian from the Carolingian Empire and the Asturian Chronicles from Galicia complement the Muslims’ testimony. Additional sources from Christians include Dudo of Saint Quentin, William of Jumièges, the Annals of St-Bertin, the Chronicle of Regino de Prüm, and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle.

Further complicating things, the Muslim sources lack the consistency of nomenclature in referring to the Vikings. The earliest sources tell us that the Muslims of the 9th and 10th Centuries understood that they were dealing with a single people, whether they encountered them on the shores of Spain, the Mediterranean, or the Eastern Steppes. The historian al-Yaqubi, for example, did not differentiate between the Vikings in the East and West. In one of his works, he claimed that “the Madjus, who are called the Rus,” attacked Seville. We know the Rus did not attack Spain, so the nomenclature mistake, while frustrating, is telling.

The First Wave of Vikings in SpainAlthough some evidence suggests earlier incursions into Iberia by the al-Madjus, the currently accepted historical start of Viking raids in Spain date to the attack on Seville in 844 A.D. Using a mixture of Christian and Muslim Chronicles to track the Vikings’ movements, historians have pieced together a reasonably coherent narrative of the Iberian experience during the Viking Age.

The sources tell us that a fleet of ships that had raided the Carolingian Empire sailed from the Bay of Biscay into Northern Spain. There they raided a few settlements before encountering a large force of Asturians under the command of King Ramiro I. The Vikings suffered a crushing defeat and retreated to an island base on the French coastline. There is much debate over the base’s location, but it may have been as close as Bayonne.

A few months later, a larger fleet of eighty ships appeared off the coast of Lisbon, where they fought and won three sea battles against Muslim ships. They then headed south to the mouth of the Guadalquivir, made their way inland, and sacked the city of Seville, which they occupied. The attack was so unexpected that Cordova, the administrative center of Islamic Spain, called al-Andalus, lacked a response. It took them weeks to muster an army to drive out the Vikings from the city. Following the Vikings’ bold incursion into his lands, Emir Abd al-Rahman II ordered the construction of a new fleet of ships to counter al-Madjus raids.

The Emir sent a Moorish ambassador, al-Ghazal, to learn about their new enemy. His account tells of his voyage to a splendid island with lush, flowering plants and abundant streams leading to the ocean. For years historians struggled to gather consensus on where he had traveled. Some believe he visited Ireland, while others believe he visited Denmark. The source for al-Ghazal’s embassy to Ireland is a document by Abu-l-Kattab-Umar-ibn-al-Hasan-ibn-Dihya, born in Valencia in Andalucia, about 1159 A.D. The facts and anecdotes in the story were derived from Tammam-ibn-Alqama, vizier under three consecutive amirs in Andalucia during the ninth century, who died in 896. Tammam-ibn-Alqama had allegedly learned the details directly from al-Ghazal and his companions. The only manuscript of ibn-Dihya’s work has d at the British Museum since 1866. It is titled Al-mutrib min ashar ahli’l Maghrib, which translates as An amusing book from poetical works of the Maghreb.

Al-Ghazal’s testimony offers a glimpse into how the Muslims viewed the Vikings. His story speaks of a vast moral gulf regarding sexuality, fidelity, and loyalty. During his stay, he claims, he had an affair with the chieftain’s wife, and he commented at length about her privileged position and power within the community, which stood in contrast to the Muslim view of how women should behave. Historians take his testimony with great caution–his evident bias undermines his credibility, and it is uncertain whether some of his remarks were inserted by later writers.

Al-Ghazal was not the only ambassador to travel north to meet the Vikings, although he is thought to have been the only Muslim ambassador to have launched from Spain. Others, such as Ibn-Fadlan, visited the Rus in the East and studied them in detail. Ibn-Fadlan’s account is one of the most universally known and well-studied documents about the Vikings produced by a Muslim.

The Second WaveWe have no record of any other attacks by the al-Madjus from 844 until 859, when an ambitious man named Hasting made an infamous incursion into the Mediterranean. With the help of his close friend Bjorn Ironside, a supposed son of Ragnar Lothbrok, Hasting sailed to Iberia on his way to the Mediterranean, hoping to gain fame and fortune by pillaging Rome. At first, the expedition did not fare well. The Asturians of Northern Spain fought them off, forcing the expedition to continue southward without loot. They successfully pillaged coastal settlements until they arrived at Gibraltar, where a storm blew them off course. They landed in North Africa and raided for slaves before resuming their original intended course.

According to the chronicler Dudo of St. Quentin, Hasting was ambitious and sought to sack Rome itself. So the story goes, the walls of the city were too tall and well-fortified. Thus he hatched one of the more notorious plans to take the city by creating a ruse to trick the “naïve” Christians. They arrived at the city and sent a messenger to inform the bishop that their leader had been mortally wounded and, in his dying moments, wished to be baptized so that he might reach salvation. The bishop took pity on him and organized the ceremony. The next day, the Norsemen returned to the city to inform the bishop that their chieftain had died and that he had requested burial in the city. Again, the bishop took pity on them and organized the funeral. They placed Hasting’s body on a bier and carried him inside the city. A gathering of noblemen and clergypersons joined them to begin the ceremony when Hasting rose from the dead, snatched the sword beside him, and cut down the bishop.

The ruse proved successful. They sacked the city and loaded their ships with loot. As they sailed from the city, they realized they had made a navigational error. The city they had sacked was not Rome but a smaller settlement called Luna, some two hundred miles north of their intended target. Nevertheless, Hasting ordered a return to his base on the Loire. However, as they attempted to sail past Gibraltar, a Muslim fleet intercepted them, destroying a significant portion of the Viking fleet with Greek Fire. Their chieftain survived and returned to his base on the island of Herius (today called Noirmoutier) with twenty ships, a mere third of the ships he had departed with three years earlier.

The Third WaveArabic sources tell of a third wave of attacks beginning in 966 A.D., over 100 years after the conclusion of Hasting’s expedition. Where this fleet came from is not entirely clear, but there is strong evidence to suggest they launched from Normandy after having helped Duke Richard I suppress a rebellion in his duchy. They arrived in Galicia and did what they are known best for: they pillaged. In response to the attack, the bishop of Santiago de Compostela, an important pilgrimage site, gathered an army to fend them off. By sheer bad luck, the bishop took an arrow to the neck and died during their second battle. Devastated, his troops retreated, and the Vikings continued terrorizing the surrounding countryside. For three years, they attacked and plundered Galicia. Historians disagree over why their long-term presence did not turn into a settlement as it had in Ireland, Britain, and Normandy. Nevertheless, in 972, they made one last major push for plunder, and returned home.

The Fourth WaveBeginning in the year 1008, a new threat emerged from the north with its sights on Galicia. Again, regular seasonal raids struck terror in the hearts of the Spaniards. In 1038, a renewed raid struck the town of Tui, led this time by Olav Haraldsson, heir to the throne of Norway. They captured the bishop and held him for ransom, though the sources do not give us much detail on this interaction. Olav’s chroniclers, Sigvat and Ottar, heavily reference their patron’s successes in Galicia, earning him the name “the Galician Wolf.”

A Small but Significant ExperienceUltimately, Spain experienced the more minor brunt of the Viking Age compared with areas such as Ireland, Britain, and France. However, both the Christian kingdoms and Muslim territories in Iberia suffered terrible wounds from the raids. Arguably, the Viking attacks on al-Andalus encouraged the Muslims of Spain and North Africa to fortify their seaborne fleets, which helped the Islamic world maintain naval supremacy in the Mediterranean over Christendom until the high middle ages. This may have directly affected the course of the crusades and, indeed, the course of history in Europe. Spain is not often the focus of Viking Age events, but their experience is crucial to understanding the Viking Age.

June 18, 2022

Did Vikings Attack the Island of Noirmoutier in 799 A.D.?

Most modern history books on the Vikings tell us that the monastery of St. Philbert on the island of Noirmoutier succumbed to an attack by Vikings in 799 A.D. To most, it is a fact. Recent scholarship has called into question whether the Vikings were to blame for the attack and whether the monastery of St. Philbert was the target. Did Vikings Attack the Island of Noirmoutier in 799 A.D.? Here I will discuss both sides of the debate and which side has the upper hand.

Why do we think the Vikings attacked Noirmoutier in 799?What we know about the attack comes to us by a letter from the theologian Alcuin—who also wrote about the attack on Lindisfarne—to the bishop Arno of Salzburg. He described an attack by Paganae, or pagans, in the insulas oceani partibus Aquitaniae, or islands of Aquitaine. While the testimony proves light on details, historians have traditionally co-referenced Alcuin’s letter with concurrent mentions of Viking activity on the Western coast of France produced by the Carolingians.

The first mention appears in the Two Lives of Charlemagne by the biographer Rimbert. In or around 800, emperor Charlemagne encountered a fleet of Viking ships off the coast of Aquitaine. So says Rimbert, when they learned the emperor had taken up residence in the coastal village they had intended to raid, they turned tail and sailed away.

A second mention in the biographical Vita Karoli Magni by the biographer Einhart also places Charlemagne in Aquitaine in or around the year 800, emphasizing that part of the reason for the visit had to do with the fact that Northmen had infested the area (Nordmannicis infestum erat).

Two later documents further confirm that Vikings had carried out the attack and that the monastery of Noirmoutier had been a target. A letter by the abbot of St. Philbert in 819 complained of frequent raids, and a later account by the monk Ermentarius written in the 830s mentions the first raid, although the account gives few details.

Why Some Historians Now Question If Vikings Attacked Noirmoutier in 799.The historian Simon Coupland first questioned whether Vikings or someone else had carried out the raid on Noirmoutier. He cited the monk Ermentarius’ testimony of a Moorish raid attempt, telling us that the Moors were active in the area at the time. Further, he cites another letter by Alcuin describing Muslims as paganae, denoting a tendency by our primary source to conflate the different groups of people raiding in and around Aquitaine at the turn of the century.

Some historians have seen enough cause to dismiss the 799 raid altogether, placing the first major Viking incursions into Western France ten to fifteen years later, consistent with our primary testimony from St. Philbert monks.

Who is right?It is essential in the study of history to hold claims to scrutiny. The renewed scrutiny over whether Vikings attacked the island of Noirmoutier in 799 A.D. puts conventional wisdom to the test and reminds us that so little is certain in the study of the Viking Age. My opinion–and I take this position rather strongly in my own research–is that the attack was indeed carried out on Noirmoutier, ile D’Yeu, and ile de Rez in 799 A.D by Vikings. While the prospect of a Moorish raid intrigues me, the Carolingians placed far too much emphasis on the growing threat of the Vikings in too broad a breadth of concurrent sources for the opposite to have been true.

The raid on Noirmoutier also fits in well with the westward progression of Viking raids across the west. First, Lindisfarne in 793, Iona in 795, and St. Philbert in 799. Coupled with the repeated alarm-sounding by Charlemagne’s biographers of the looming Northman threat, I believe we have a solid case in favor of the Vikings.

January 25, 2022

The Blood Eagle: A Gruesome but Possible Execution?

In a new study published in the journal Early Science, researchers theorized that the “blood eagle” may have been an actual execution method used by Vikings. The gruesome act involves cutting open the victim’s back, pulling out their lungs, and then stretching them across their wings like a bloodied eagle. The article says that there is evidence that Vikings were feasibly capable of performing the act. So what does saga literature say about the blood eagle? Furthermore, was it put into practice?

What was the Blood Eagle, and Where is it Mentioned in Medieval Writings?The Saga of Ragnar Lodbrok first mentions the Blood Eagle, mentioning that Viking king Aslak Hane was executed in this way. The saga also mentions that Vikings would sometimes cut off their enemies’ heads and hang them on poles to warn others. Interestingly, there is no mention of the blood eagle as an execution method until after the death of Aslak Hane. Some scholars have theorized that this may be because the act was so gruesome that it was only used as a last resort.

The blood eagle was later used to torture and eventually kill four powerful male figures—Halfdan Haleggr, King Ælla of Northumbria, Lyngvi Hundingsson, and Brúsi of Sauðey. The accounts in Old Norse literature span from the 11th to the 13th centuries. The eight Old Norse texts contain the phrase “to carve/cut/mark an [blood] eagle,” which also appears in the Gesta Danorum, a Latin source, which describes how the perpetrators “commanded that the image of an eagle should be etched onto his back.”

Despite their comparable appearance, the sources have no agreement on what exactly constituted the blood eagle. The victim is taken captive following armed conflict and subsequently has an eagle carved or cut into his back in all nine of the recorded instances.

A New Study Argues in Favor of the Anatomical Possibility of the ActThe notorious blood eagle ritual has long been a source of debate: did Viking Age Nordic people torture one another to death by cutting away their ribs and lungs from their spine, or is it all a misunderstanding of some perplexing verse? Previous research focused on the accuracy and completeness of ancient texts describing the blood eagle, with advocates for or against its historicity. The study of the anatomical and socio-cultural restrictions within which any Viking Age blood eagle would have had to be carried out has thus far not been addressed. The new study evaluates medieval descriptions of the ritual with a contemporary anatomical understanding. It contextualizes specific reports with recent archaeological and historical scholarship on elite culture and the ritualized mutilation of the human body in the Viking Age. The study argues that even the most complete form of the blood eagle described in textual sources was feasible but difficult. They concede that the practice would have resulted in the victim’s death early on in the procedure.

The study can be found at:

-Early Science: Volume 21, Issue 01, 2018 – “On the Wings of Eagles? A Reconsideration of the ‘Blood Eagle'” by Søren Sindbæk and Alexander J.C. Thomas

C.J. Adrien’s TakeAs I tend to do with new studies that make bold claims, I will address this one with caution. The tendency in academia today is to create clickable headlines for articles because attention and reach equal funding. Of course, the study authors are established scholars, and I have no reason to doubt they did their due diligence in researching the topic. However, this study does have the look and feel of attention-grabbing. Hence, while I agree with their conclusions based on the thorough evidence they proposed in their study, I find the conclusions lacking in impact. While the new study provides a convincing argument for the Blood Eagle’s feasibility, there is still no solid evidence that it was put into practice. We may never know whether or not the Vikings carried it out.

With that said, I do still think the Blood Eagle may have been a literary device. Where the sources are concerned, we must remember these were written decades and centuries after the events they chronicle by authors who were neither present nor involved. Yes, archeological finds have confirmed a few elements from the sagas, but that does not mean they are entirely reliable sources. Their historicity remains dubious at best.

As an author of historical fiction (and not just a historian), I would also like to add that the Blood Eagle is an attractive element that would spice up any story. While it may not be particularly good history, it certainly makes for good fiction. For me, that idea alone is telling. Writers have an audience in mind, and we know from many medieval sources that inserting fantastical elements for the benefit of readers was commonplace. Anatomical feasibility is a far cry from hard evidence of the practice. In my opinion, I do not think the Blood Eagle ever took place, but rather it showed up in later sources as a literary device.

October 9, 2021

Curious About the Current State of Viking Age Research? A New Paper from Denmark Overviews Viking Research “Hot Spots”