C.J. Adrien's Blog, page 3

June 30, 2025

Forged for France? The Curious Case of Groix’s Viking Shield Bosses.

Welcome to the newsletter, where history, storytelling, and inspiration meet. Every week, I share some of the fun historical research I’ve done while writing my novels, writing reflections (and sometimes tips), and sharing updates on my work and journey. If you were forwarded this message, you can join the weekly newsletter here.

Today’s DispatchViking History: What four shield bosses on Groix tell us about the Vikings.

Writing and Publishing: Launch days are the worst.

Author Update: The Empress and Her Wolf releases TOMORROW

This week’s book recommendation.

Viking HistoryThe Ship Burial on Groix and What it May Tell Us About the Vikingsvikingwriter

Viking HistoryThe Ship Burial on Groix and What it May Tell Us About the Vikingsvikingwriter

A post shared by @vikingwriter

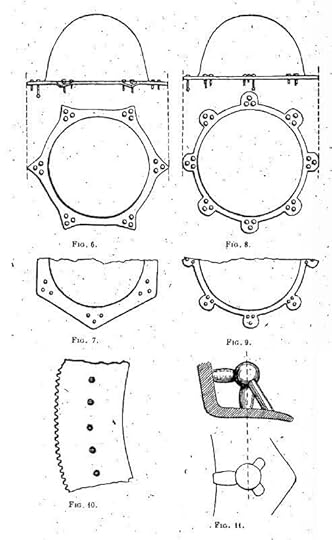

A post shared by @vikingwriterThe ship burial on the island of Groix off the southern coast of Brittany reveals something fascinating: not all Viking equipment fits the Scandinavian mold. Among the weapons and armor uncovered at the site, including 33 shield bosses of the typical Scandinavian make, were four shield bosses unlike any previously found in Scandinavia. These bosses were plain, rounded, and slightly steeper than the typical hemispherical shape. But what truly sets them apart is the design of their rims.

Two bosses feature six-pointed projections, each secured with three rivets.

Two others display eight rounded projections, each with three rivets.

A fragment from another rim shows densely set rivet holes and a finely indented border—perhaps decorative, or maybe functional.

The four shield bosses of altered design from the Groix ship burial.

The four shield bosses of altered design from the Groix ship burial.These atypical designs suggest something more than regional style—they may indicate adaptation. The Groix burial is strong evidence that Norse warriors in Brittany were not simply transplanting their gear, but modifying it—possibly to suit new forms of combat, local materials, or even to align with Frankish or Breton aesthetic and martial traditions.

It’s a reminder that the so-called “Vikings” were more than raiders—they were agile, observant, and strategically flexible. And when they came ashore in Brittany, they didn’t just bring their weapons—they reimagined them.

Want to see these artifacts for yourself? Check them out here »»»

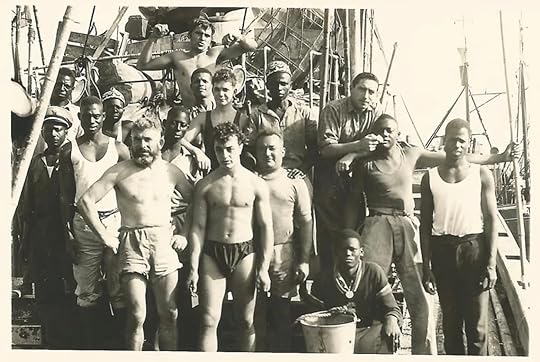

Writing and PublishingLaunch Days Are the Worst. Or Are They?Tomorrow is launch day for The Empress and Her Wolf. You’d think I’d be excited—and I am, sort of—but if I’m being honest, launch days are always a bit of a rollercoaster for me.

There’s enormous pressure in the publishing world to make launch day the most important day. The big six publishing houses (I call them “the cartel”) treat it like a high-stakes moon landing: press releases, author interviews, email blasts, and paid reviews timed down to the hour. The prevailing wisdom is that if you don’t hit big in the first 24 to 72 hours, you’re toast. The industry moves on.

But I’ve learned that’s not the whole story in indie publishing.

Take The Lords of the Wind. When I released it, I didn’t even have a formal launch plan. No countdown. No party. No press. Just a quiet “soft launch” to see what would happen. For the first 60 days, not much did. A few sales here and there. A handful of reviews. Crickets, mostly.

Then something changed.

Perhaps it was all the marketing I did (I’m sure that helped), along with word of mouth, and probably a significant amount of the algorithm gods smiling down on me, but within weeks, sales began to climb. Ten books a day. Then twenty. Thirty. Forty. By day 90, The Lords of the Wind hit #1 in its category. And when I enrolled it in Kindle Unlimited, it held that top spot for an entire year, long enough for me to write and launch the sequel with thousands of eager readers waiting.

That’s the magic of being indie. You’re not on a ticking clock. You don’t have to “make it or break it” in three days. Your book can grow organically, on its own merit, over months or even years. I still get chart spikes during promotions for books I released years ago.

So yes, launch day is stressful. It feels like it should be huge. But I’ve come to see it as just one step in a longer journey. If you’re an author feeling that pressure, take a breath. Focus on the long game. Build something worth reading, and the readers will come. Consistency is key. Like fitness, if you want results, you build your lifestyle around your goals, and it will all fall into place…eventually.

And if you are excited for The Empress and Her Wolf, I’d love your support tomorrow. Every pre-order, review, and share still helps. But I promise: I won’t vanish if we don’t hit #1 on day one.

We’re in this for the long haul.

BUY THE EMPRESS AND HER WOLF !!

Author UpdateThe Empress and Her Wolf

The Empress and Her Wolf, book 5 of the Hasting Saga, hits shelves TOMORROW. Here’s the blurb:

Power. Revenge. Forbidden love in the heart of a dying empire.

When Viking warlord Hasting arrives at the gates of Constantinople, he knows he can’t conquer it. Not with deeds of arms alone. But fate has other plans.

A failed raid turns into a devil’s bargain: serve Empress Theodora as her sword-for-hire, or die. Hasting chooses survival and quickly proves himself more capable than the generals she no longer trusts. But the empire is a viper’s nest of betrayal, and when an attempt to scare off his men ends in the death of his lover, Hasting’s mission changes.

He came for wealth and glory. Now, he wants blood.

But revenge in Miklagard is no simple feat. The city runs on whispers, not war cries. Enemies hide behind silks and smiles. And as Hasting grows closer to the empress—ally, ruler, and eventually lover—he finds himself torn between love and vengeance.

One wrong move could cost him everything.

Perfect for fans of Bernard Cornwell, Giles Kristian, Peter Gibbons, and Conn Iggulden, The Empress and Her Wolf is a heart-pounding saga of war, loyalty, and ambition set against the glittering, dangerous world of the Byzantine Empire.

Blurb:

“I’m a Viking!” is a history book about the Viking Age for kids. Join Leif, a chieftain’s son who wants nothing more than to grow up to be a Viking just like his dad. Follow Leif as he gives you a tour of his life—the things he must learn, the things he likes to do for fun, and much more.

Conceived and written by author and historian C.J. Adrien and illustrated by the talented Crystal Whithaus, “I’m a Viking!” is an excellent primer for young minds interested in the past. Don’t be fooled—grown-ups may learn a thing or two, too.

And, as always…Buy my novels!

June 23, 2025

The Most Poweful Woman in History You've Never Heard Of.

Welcome to the newsletter, where history, storytelling, and inspiration meet. Every week, I share some of the fun historical research I’ve done while writing my novels, writing reflections (and sometimes tips), and sharing updates on my work and journey. If you were forwarded this message, you can join the weekly newsletter here.

Today’s DispatchViking History: Empress Theodora and the Rus.

Writing and Publishing: The Inspiration Behind Hasting’s Personality.

Author Update: The Empress and Her Wolf

This week’s book recommendation.

Viking HistoryEmpress Theodora and the Rus.

Viking HistoryEmpress Theodora and the Rus.

Theodora of Byzantium (c. 815–867) is a name often overlooked in most history books, yet her reign profoundly shaped the spiritual and political fabric of the empire. Plucked from the provinces in a "bride-show" to wed Emperor Theophilos, she was intelligent, composed, and devout. Though Theophilos was an ardent iconoclast and violently opposed religious images, Theodora quietly maintained her belief in icons, hiding them and venerating them in secret.

When Theophilos died in 842, Theodora seized the moment. As regent for their son Michael III, she ruled the Byzantine Empire in her own right. Her first act was momentous: she convened a council to restore the veneration of icons, ending decades of religious conflict. Her bold move is still commemorated in Orthodox churches today as the “Triumph of Orthodoxy.”

Under her regency, Byzantium knew relative peace and economic growth. She negotiated treaties with Arab powers, stabilized the borders, and sent successful expeditions to Crete, Egypt, and Sicily. She governed with shrewd political instinct by removing threats, installing loyal administrators, and holding her position until her teenage son pushed her aside in a palace coup. Even then, she lived on in quiet dignity until her death in 867, later canonized for her role in the restoration of Orthodoxy.

And yet—what if there was more to her story?

In my upcoming novel, The Empress and Her Wolf, Hasting, a legendary Viking chieftain, arrives in Constantinople in 848 as part of a Rus expedition. These early contacts between the Norse and Byzantines are well-documented, with merchants, warriors, and wanderers navigating the Dnieper to reach the empire’s gilded gates. What begins as a mercenary alliance soon erupts into something far more dangerous.

vikingwriter A post shared by @vikingwriterWriting and PublishingThe Inspiration Behind Hasting’s Personality.

A post shared by @vikingwriterWriting and PublishingThe Inspiration Behind Hasting’s Personality.When I set out to write The Saga of Hasting the Avenger, I knew I wanted to capture more than just swords and longships. I wanted to breathe life into a character who could lead men, defy kings, cross oceans, and carry the weight of both glory and grief. To do that, I needed someone real to model him after—someone larger than life.

I didn’t have to look far.

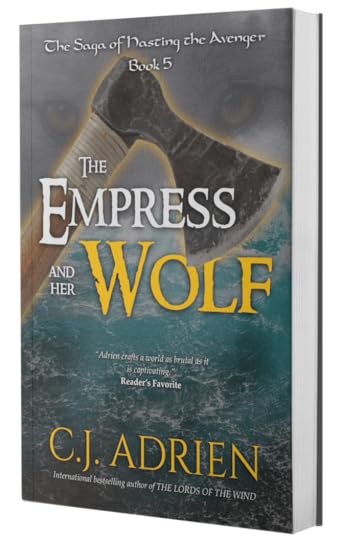

My grandfather, Michel Adrien, grew up in Nazi-occupied France and came of age in a world still reeling from war. At just 19, he became the youngest man in France to earn his ship captain’s license—a feat that marked the beginning of a remarkable journey. Through a mix of courage and charm, he convinced a skeptical local bank to finance a larger fishing vessel, then sailed it to Senegal. There, he built a career that would become legendary: winning the national tuna fishing derby five years in a row. He did it with the first and only mixed-race crew in the region—black and white men working side by side under his command, decades before such a thing was common.

Michel Adrien (on the far right) with the crew of his ship Le Fils de la Vierge, the first mixed crew in history.

Michel Adrien (on the far right) with the crew of his ship Le Fils de la Vierge, the first mixed crew in history.Michel was a man who did not ask permission to succeed. He thrived in chaos, navigated the storms of life with instinct and fury, and carved out his path where none had existed before. He was respected, feared, and at times misunderstood. Eventually, he built a commercial fishing empire that spanned the globe, from France to Senegal, to Peru and Japan.

When I began shaping Hasting’s personality, I found myself returning again and again to Michel’s story. His tenacity. His wild ambition. His ability to lead and his struggle with solitude.

If you sense something deeply human beneath the myth of Hasting, it’s because he’s drawn in part from a man I knew—a man who truly lived.

Author UpdateThe Empress and Her Wolf

All month long, I’ll be promoting The Empress and Her Wolf, book 5 of the Hasting Saga. Here’s the blurb:

Power. Revenge. Forbidden love in the heart of a dying empire.

When Viking warlord Hasting arrives at the gates of Constantinople, he knows he can’t conquer it. Not with deeds of arms alone. But fate has other plans.

A failed raid turns into a devil’s bargain: serve Empress Theodora as her sword-for-hire, or die. Hasting chooses survival and quickly proves himself more capable than the generals she no longer trusts. But the empire is a viper’s nest of betrayal, and when an attempt to scare off his men ends in the death of his lover, Hasting’s mission changes.

He came for wealth and glory. Now, he wants blood.

But revenge in Miklagard is no simple feat. The city runs on whispers, not war cries. Enemies hide behind silks and smiles. And as Hasting grows closer to the empress—ally, ruler, and eventually lover—he finds himself torn between love and vengeance.

One wrong move could cost him everything.

Perfect for fans of Bernard Cornwell, Giles Kristian, Peter Gibbons, and Conn Iggulden, The Empress and Her Wolf is a heart-pounding saga of war, loyalty, and ambition set against the glittering, dangerous world of the Byzantine Empire.

Blurb:

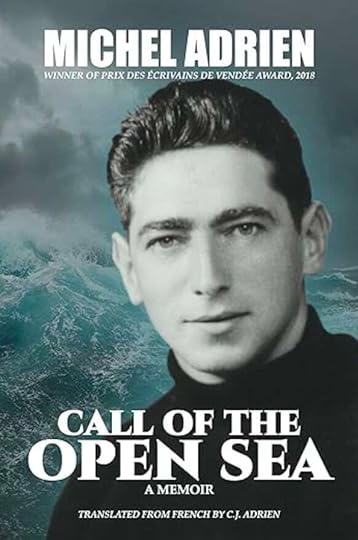

This is one of those stories that sounds so improbable that, were it fiction, we would think it unbelievable. But it's a true story. Michel Adrien’s autobiographical memoir chronicles his extraordinary journey from the war-torn countryside of rural France to becoming one of the wealthiest men in the nation. Leaving behind a life of poverty and wartime scarcity, Adrien embarked on a bold venture into West Africa, where he built a commercial fishing empire that played a pivotal role in the economic development of several post-colonial West African countries.

Extraordinary accomplishments punctuate Adrien’s life: from his triumph as a champion tuna fisherman and the first European to employ a mixed African-European crew, to his defiance of Russian economic threats and rallying of allies to safeguard his enterprises, to his ultimate act of generosity in gifting his Senegalese armament for the nation’s future prosperity. His journey is a testament to personal ambition, resilience, and a profound exploration of the moral complexities of navigating decolonization and the Cold War.

Translated by his grandson, this first memoir chronicling Michel’s life up to 1975 offers a rare, firsthand account of historical events from a unique perspective, providing valuable insights into the intersections of power, race, and humanity. Michel Adrien’s story is a poignant reminder that truth can be stranger than fiction, and his perspective is worthy of reflection.

Call of the Open Sea is a Winner of the Prix des Ecrivains de Vendée award, 2018.

June 16, 2025

What Do the Vikings and The Predator Have in Common?

Welcome to the newsletter, where history, storytelling, and inspiration meet. Every week, I share some of the fun historical research I’ve done while writing my novels, writing reflections (and sometimes tips), and sharing updates on my work and journey. If you were forwarded this message, you can join the weekly newsletter here.

Today’s DispatchViking History: The Vikings and Their Skulls.

Writing and Publishing: No Pain, No Gain.

Author Update: The Empress and Her Wolf

This week’s book recommendation.

Viking HistoryThe Vikings Are Like The Predator: They Both Really Liked Skulls.

Viking HistoryThe Vikings Are Like The Predator: They Both Really Liked Skulls.

Leave it to me to compare Vikings to a Hollywood alien with a fondness for ripping skulls from spines. But after our latest Vikingology episode with archaeologist Dr. Martin Rundkvist, the connection didn’t feel so far-fetched.

Martin’s recent paper delves into one of the more unusual aspects of the Viking Age: the curious treatment of human skulls. In graves across Scandinavia, archaeologists have discovered skulls that don’t match the rest of the skeletons, sometimes older than the graves in which they were buried. In other words, the Vikings excavated old skulls and reburied them alongside new ones. Why? No one knows. That’s the mystery. And it gets weirder.

Despite a general taboo against decapitation, which was typically reserved for slaves or criminals, there seems to have been a separate, symbolic value assigned to the human head after death. Once the soft tissue was removed, the skull became something more.

We see hints of this in the sagas. Óðinn carries around the decapitated head of Mímir, which speaks and gives him wisdom. Skulls in the archaeological record appear in boundary places, such as along city walls, at the edges of graves, and even in bogs, all of which are liminal zones where the living and the dead come into contact with each other.

Martin is quick to point out that the evidence is fragmentary, and his goal is to spark more investigation rather than offer definitive answers. But the implications are bizarre: why were the Vikings digging up and reusing skulls?

And that’s where my brain jumped to Predator. That iconic image of a creature collecting skulls as trophies suddenly didn’t feel so alien. The Vikings may not have been intergalactic hunters. Still, they had a complex, perhaps even ritualistic, fascination with human heads, as so many other human cultures have had (in our conversation, Martin pointed out that the Celts were much more skull-crazy than the Vikings).

I managed to make my three skull jokes, only to be one-upped by Martin! Behind the humor lies a genuine historical puzzle, one that I hope archaeologists will continue to explore. Check out the episode below.

Writing and PublishingNo Pain, No Gain.Novel writing is hard. Really hard. You just won’t believe how vastly, hugely, mind-bogglingly hard it is. I mean, you may think it’s tough to assemble IKEA furniture without the instructions, but that’s just peanuts to novel writing. And hard is why it’s worth doing.

We live in an age of extraordinary ease. Food arrives at our doorstep. Entertainment is instantly accessible. Work is increasingly remote and streamlined. Paradoxically, we are more anxious, more depressed, and more discontented than ever before. This contradiction has become increasingly apparent to me throughout my careers as a schoolteacher, a personal trainer, and a business professional. It is not necessarily that people are lazy. Rather, many of us have developed a strong aversion to discomfort.

But discomfort is essential. I believe in doing something difficult every day. I call this practice my “pain schedule.” I deliberately challenge my body through daily exercise, whether that means climbing Lava Butte on my bike as fast as possible or attempting personal records in the gym. I challenge my mind each morning with a routine that includes meditation and reflection on gratitude, both of which are deceptively demanding. I challenge my spirit by engaging in the rigorous work of writing novels. I do all of this while balancing the responsibilities of family life, raising children, and preparing for an international move.

And I am grateful for every one of these challenges. They shape me. They make me stronger, wiser, and more resilient.

It may feel like the world is coming apart at the seams. In reality, what we are experiencing is the aftershock of half a century of prosperity on a scale humanity has never known. We have grown soft. We have grown entitled. But challenges are coming, and I welcome them. Hardship is not something to be feared. It is an invitation to become better than we were. Through difficulty, we discover what we are made of. Through adversity, we grow.

For those interested in exploring this idea more deeply, I highly recommend the book Dopamine Nation by Dr. Anna Lembke (see this week’s book recommendation below). It is a compelling exploration of how modern abundance has hijacked our pleasure centers and why intentionally leaning into pain and discomfort may be the antidote to modern misery. Lembke, a psychiatrist at Stanford, combines neuroscience, clinical insight, and real-life stories to demonstrate that a life of ease can often lead to profound suffering, and that a return to meaning requires a recalibration of our relationship with pleasure and pain. Her message resonates deeply with my own experience and philosophy.

So I urge you: choose the hard path. Write the book. Climb the mountain. Face the change, the chaos, and the unknown. Because growth requires struggle, and happiness is found through growth.

And when life demands, “How will we get to the top of that hill?”

Remember what Arnold Schwarzenegger said during the filming of Conan the Barbarian, when producer Dino De Laurentiis asked him the same question.

Arnold simply replied, “We are going to climb.”

Here’s a video I made about this on Instagram:

vikingwriter A post shared by @vikingwriterAuthor UpdateThe Empress and Her Wolf

A post shared by @vikingwriterAuthor UpdateThe Empress and Her WolfAll month long, I’ll be promoting The Empress and Her Wolf, book 5 of the Hasting Saga. Here’s the blurb:

Power. Revenge. Forbidden love in the heart of a dying empire.

When Viking warlord Hasting arrives at the gates of Constantinople, he knows he can’t conquer it. Not with deeds of arms alone. But fate has other plans.

A failed raid turns into a devil’s bargain: serve Empress Theodora as her sword-for-hire, or die. Hasting chooses survival and quickly proves himself more capable than the generals she no longer trusts. But the empire is a viper’s nest of betrayal, and when an attempt to scare off his men ends in the death of his lover, Hasting’s mission changes.

He came for wealth and glory. Now, he wants blood.

But revenge in Miklagard is no simple feat. The city runs on whispers, not war cries. Enemies hide behind silks and smiles. And as Hasting grows closer to the empress—ally, ruler, and eventually lover—he finds himself torn between love and vengeance.

One wrong move could cost him everything.

Perfect for fans of Bernard Cornwell, Giles Kristian, Peter Gibbons, and Conn Iggulden, The Empress and Her Wolf is a heart-pounding saga of war, loyalty, and ambition set against the glittering, dangerous world of the Byzantine Empire.

Blurb:

This book is about pleasure. It’s also about pain. Most important, it’s about how to find the delicate balance between the two, and why now more than ever finding balance is essential. We’re living in a time of unprecedented access to high-reward, high-dopamine stimuli: drugs, food, news, gambling, shopping, gaming, texting, sexting, Facebooking, Instagramming, YouTubing, tweeting . . . The increased numbers, variety, and potency is staggering. The smartphone is the modern-day hypodermic needle, delivering digital dopamine 24/7 for a wired generation. As such we’ve all become vulnerable to compulsive overconsumption.

In Dopamine Nation, Dr. Anna Lembke, psychiatrist and author, explores the exciting new scientific discoveries that explain why the relentless pursuit of pleasure leads to pain . . . and what to do about it. Condensing complex neuroscience into easy-to-understand metaphors, Lembke illustrates how finding contentment and connectedness means keeping dopamine in check. The lived experiences of her patients are the gripping fabric of her narrative. Their riveting stories of suffering and redemption give us all hope for managing our consumption and transforming our lives. In essence, Dopamine Nation shows that the secret to finding balance is combining the science of desire with the wisdom of recovery.

June 9, 2025

Corn-walla-what?! The Region of Britain that Was Ready for the Vikings.

Welcome to the newsletter, where history, storytelling, and inspiration meet. Every week, I share some of the fun historical research I’ve done while writing my novels, writing reflections (and sometimes tips), and sharing updates on my work and journey. If you were forwarded this message, you can join the weekly newsletter here.

Today’s DispatchViking History: Cornwall’s role in the Viking Age.

Writing and Publishing: Books.by BEWARE.

Author Update: Aaargh! The Book is Done!

This week’s book recommendation.

Viking HistoryCornwall’s Role in the Viking Age

Viking HistoryCornwall’s Role in the Viking Age

There’s a scene in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy when Arthur Dent finds himself at a party “full of idiots” chatting with Trillian, who would later become his romantic interest, who says, “Let’s go somewhere.” He asks, “Where?” She answers, “Madagascar.” He replies, “Let’s start with somewhere closer... like Cornwall.” The line lands because Cornwall has long sat in the British imagination as a kind of end-of-the-road backwater. It’s quiet, remote, and as far as anyone else in Britain is concerned, unremarkable.

But as historian John Fletcher explained on the latest episode of Vikingology, Cornwall’s early medieval history is perhaps among the most fascinating of the Viking Age.

Drawing from his book The Western Kingdom: The Birth of Cornwall, Fletcher brought to life a region that survived and thrived through the collapse of Rome, rather than merely endure it. Cornwall’s landscape, carved into peninsulas and inlets, was never suited for centralized Roman-style urbanism. Instead, the Cornish kings ruled by movement. There was no fixed capital. Authority shifted with the court as it traveled. Power was anchored in people, not cities.

The name itself hints at the terrain. Cornu in Latin refers to a horn or peninsula—Cornwall meaning the land at the horn’s edge. Geography mattered. This was a maritime society, culturally and economically shaped by its exposure to the sea. Long before Viking sails appeared on the horizon, the Cornish had already developed a defensive posture against Irish and Welsh raiders. They understood seaborne conflict.

When a Viking fleet arrived in 838, the Cornish didn’t treat them as an existential threat. They saw an opening. They allied with the Norse against their long-standing rivals in Wessex. It is one of the earliest recorded instances of a native British polity forming a strategic partnership with a Viking force. That moment, which had been largely overlooked in broader Viking narratives, preceded the better-known attacks on Nantes in 843 and Paris in 845, as well as the arrival of the so-called Great Heathen Army in 865.

This early alliance in Cornwall may well represent a prototype for the kinds of accommodations and alliances that would later define Viking involvement across the British Isles and continental Europe. Far from being a peripheral backwater, Cornwall was participating and thriving in a new geopolitical landscape driven by the Vikings.

I invite you to listen to our conversation with John Fletcher. His clarity and depth on the subject bring an often-overlooked region into sharper focus. If Trillian had known how interesting Cornwall actually is, she might have taken Arthur up on his suggestion. Then again, perhaps it’s good she didn’t, since Her and Arthur’s romantic conflict was instrumental in getting us a replacement Earth.

Writing and PublishingBooks.By BEWARE.In a recent attempt to detach myself from our tech overlords’ tendrils, I decided to give a service called Books.By a try. They advertised themselves as a platform that allows authors to become their own bookstores. I found the proposition intriguing.

At first, their service impressed me. Adding books to their system was seamless, painless, and the finished product was of a higher quality than Amazon’s. I received my first couple of orders in various countries, and the service delivered the books to them without issue.

Until this week…

A reader of mine reached out to let me know that, seven weeks later, she had not received her book, and Books.By customer service had yet to resolve the issue. And that’s when things got WEIRD. She copied me on an email from their agent explaining that the reason she did not receive her book is that something had gone wrong with the interior file. Rather than say they would investigate the issue, they asked her to update the interior file.

Wait. What?!

Why would a book buyer have an interior file, or even access to edit one? It was the strangest, dumbest thing I had ever seen in my author career. I told my reader to cancel the order and get her money back, and I’ll be sending her a signed copy directly.

I understand that this was just one incident, but it’s a significant mistake. I no longer trust that their team will satisfactorily resolve customer issues as promised. Therefore, for the foreseeable future, I do not recommend purchasing from them until they resolve their issues. I have a feeling AI was involved…

If you’re an author toying with signing up with them, I recommend waiting until they get their kinks figured out. If you’re looking to purchase paperback versions of my books, please visit Amazon.

Author UpdateAAARGH! It’s Done! The Book is Done!Today’s Roland Garros final between Janick Sinner and Carlos Alcaraz spoke to me. They slugged it out for five sets and five hours, and when Alcaraz finally won, he collapsed. That’s how I felt this week when I got the final sign-off on my latest novel, The Empress and Her Wolf. I felt like I could collapse from the release of stress and tension over getting this one over the finish line.

While it was not necessarily a physical endeavor under a hot Parisian sun, it was a slog. Four rounds with my editor later, including two full rewrites and one partial, I’m proud to say that the damn thing is finished. And you know what? I LOVE IT. It feels like a triumph. It’s so good, I might as well have won Roland Garros.

Why do I feel this way, you might ask? Because I tried things in this one that I haven’t tried before. We have a noir-style murder mystery, a political conspiracy, and a torrid, ill-advised love affair with problematic power dynamics thrown in the mix. It’s a departure from the other Hastings novels in that it’s not purely adventure and warfare, although there’s plenty of that in there as well!

Don’t miss this thrilling next installment of the series, and pre-order it today on Kindle to have it delivered to your device on July 1st:

Book RecommendationsThe Western Kingdom: The Birth of Cornwall

Blurb:

Cornwall has long held a mysterious allure to visitors. At once part of England and yet utterly foreign too.

This book is the first to explore the true origins, free from Arthurian mythology, of this dichotomy. Just how did a kingdom of native Romano-Britons hold out against the expanding power of the Saxon Kings of Wessex and eventually secure their language, culture and heritage into the modern day?

The answer is a tale that combines brutal warfare with cunning diplomacy and trade as it winds from the 4th century to 1066 and beyond, and one that shouts from the distant past 'Kernow bys Vyken' – Cornwall Forever.

June 2, 2025

How Did the Vikings View and Treat Homosexuality?

Welcome to the newsletter, where history, storytelling, and inspiration meet. Every week, I share some of the fun historical research I’ve done while writing my novels, writing reflections (and sometimes tips), and sharing updates on my work and journey. If you were forwarded this message, you can join the weekly newsletter here.

Today’s DispatchNíð, Ergi, and Viking Attitudes Toward Homosexuality.

The Algorithm That Got Away.

Vikings and Valkyries on Valhalla Conversations.

This week’s book recommendation.

Viking HistoryNíð, Ergi, and Viking Attitudes Toward Homosexuality

Viking HistoryNíð, Ergi, and Viking Attitudes Toward HomosexualityOne of the concepts I’ve played with in my novels is homosexuality. We know that in other areas of history, societies grappled with same-sex attraction in various ways, and it makes sense that the Vikings would have had to grapple with it as well. In my research, I’ve found that what we think we know about Viking attitudes toward homosexuality starts with two words: nið and ergi. In the Viking Age, insults carried tremendous weight. Words like níð and ergi were serious accusations tied to ideas of honor, masculinity, and social order. To understand how Viking Age Norse society viewed same-sex behavior, we must begin with these terms.

A Niðstöng, photo credit ØYVIND NONDAL/FLICKRWhat Was Níð?

A Niðstöng, photo credit ØYVIND NONDAL/FLICKRWhat Was Níð?Níð was a powerful insult. It could mean cowardice, dishonor, or lawlessness, but it also had strong sexual connotations, including accusing a man of being a passive participant (i.e., a ‘bottom’) in a homosexual relationship. From níð came words like níðingr (a coward or outcast), níðvisur (insulting verse), and níðstöng (a scorn-pole used in rituals to publicly shame someone). A man could be accused of being sannsorðinn, or “homosexually used by another man,” which was considered one of the most offensive things you could say about someone. So far as we know, there were few negative consequences for taking an active role (i.e., a ‘top’) in such affairs. Therefore, we are not looking at a society that outright rejected homosexuality, but rather incorporated it into dominance and power structures within their social constructs.

What Was Ergi?Closely tied to níð was the concept of ergi. The associated adjective argr meant effeminate, unmanly, or inclined to play the female role in sex. In Viking thought, this was deeply shameful because the passive role was viewed as a sign of weakness. Viking masculinity centered on independence, courage, and dominance. A man who submitted sexually to another man was believed to also submit in other areas and couldn’t be trusted to lead, fight, or act honorably.

This is reflected in specific law codes. In both Grágás (Icelandic) and Gulaþing (Norwegian), calling a man argr, stroðinn, or sannsorðinn was grounds for outlawry and justified violence. These insults were considered “killing words,” as uttering them had deadly consequences, and there were rules for when and how to use them.

Christian InfluenceBefore Christianity, same-sex behavior may have been tolerated in specific contexts, especially when it didn’t disrupt social expectations like marriage and reproduction. Men were expected to marry and have children to maintain the household and support family lines. So long as that happened, affectional preferences may have been overlooked.

With the Christianization of Scandinavia came new moral frameworks. Christian texts from the 12th and 13th centuries condemned homosexuality in the active and passive roles. Men and women who avoided marriage due to same-sex preference were labeled and shamed. For example, fuðflogi meant “he who flees the female sex organ,” and flannfluga meant “she who flees the male sex organ.”

Lesbianism is almost entirely absent from pre-Christian Norse texts. When mentioned, it is framed through Christian moralizing. Old Norse language didn’t even have a clear vocabulary to describe same-sex relationships between women. The focus was always on whether individuals performed their expected roles in society.

Gods, Heroes, and ContradictionsNorse mythology complicates the picture. Odin, the Allfather, was mocked for practicing seiðr, a magical art associated with women and the concept of ergi. Loki famously took the form of a mare and gave birth to a foal. Neither god loses their status as a result of these behaviors. There are hints in myth and ritual that certain priesthoods, especially those devoted to fertility gods like Freyr, may have included men who engaged in behaviors seen as argr by later Christian standards.

In some heroic literature, the boundaries between fiction and reality become even more blurred. The Icelandic poem Grettisfærsla claims that the protagonist Grettir had sex with "maidens and widows, everyone's wives, farmers' sons, deans and courtiers, abbots and abbesses, cows and calves, indeed with near all living creatures," yet he remains a hero. The contradiction points to a more flexible pre-Christian morality, one reshaped by Christian authors who wrote down these stories centuries after the Viking Age had ended.

Final ThoughtsThe Icelandic poem Grettisfærsla claims that the protagonist Grettir had sex with "maidens and widows, everyone's wives, farmers' sons, deans and courtiers, abbots and abbesses, cows and calves, indeed with near all living creatures," yet he remains a hero.

I explored this complexity in my novel, The Lords of the Wind, through the character Egill, who, like Odin, practices the magical art of seiðr and is accused by Jarl Magnus of Ribe of seducing his brother. The accusation is meant to destroy his reputation, not because it’s necessarily true, but because it frames him as unmanly. Jarl Magnus is enraged; King Horic is unbothered. Their reactions are intended to reflect the spectrum of historical attitudes toward ergi—some rooted in power and shame, while others are more pragmatic. I further explore this concept in later novels with other characters who escape scorn for their behavior, provided they fulfill their social obligations within the warband. When they fail, disaster awaits them as they become the scapegoats for the failure. In this way, fiction can give voice to the subtleties that the historical record only hints at.

Further reading:

On homosexuality in the Viking Age: https://origin.web.fordham.edu/halsal....

On Nið and Ergi: http://vsnrweb-publications.org.uk/Ni...

Writing and PublishingChasing #1, and the Algorithm That Got AwayLast month, I landed something every indie author dreams about: a BookBub Featured Deal. These are notoriously hard to get, and when you do, they can send your book shooting to the top of the charts. That’s precisely what happened—The Fell Deeds of Fate hit #1 in Historical Norse & Icelandic Fiction in the UK.

But here’s the part that surprised me: it didn’t stay there.

In the past, a BookBub push would have driven sales for more than a couple of days. With the Lords of the Wind, it triggered Amazon’s recommendation algorithm, which picked up the momentum and kept the book visible for weeks. But this time, despite strong ongoing sales, my rank dropped back down within 48 hours. I went from #1 to #37 overnight, despite still selling copies.

After digging into it and speaking with other authors, it looks like Amazon has quietly adjusted how the algorithm works. Sudden spikes in sales (like those caused by ads or feature deals) no longer carry as much weight. Instead, Amazon now appears to favor steady, long-term sales and external traffic, particularly clicks originating from trusted referrers such as email newsletters, websites, and organic search.

It’s a tough shift. It means the days of riding the wave of a single big promo might be behind us. Now, consistent effort and diverse traffic sources seem to matter more than ever. As always, I suspect this change occurred as a deal between Amazon and the big six publishing ‘cartel’, as I call them, giving priority and preference to traditionally published books over indie ones.

That said, I’m still proud of the Featured Deal. It attracted a significant number of new readers, provided the series with increased visibility, and contributed to building momentum for the rest of my catalog. But it’s a good reminder: we’re not playing the same game we were five years ago.

The landscape is shifting. The question now is: how do we, as authors, change with it so we don’t get relegated to the dustbin?

Author UpdateVikings and Valkyries on Valhalla Conversationssoulchaserbecky A post shared by @soulchaserbecky

A post shared by @soulchaserbeckyThe cast of the live-play podcast Vikings and Valkyries—yes, including me!—recently appeared on an episode of the Valhalla Conversations podcast to lift the lid on what really happened behind the scenes. We shared how the show came together, our favorite unscripted moments, what it was like to roleplay Viking-related characters, and the unpredictable dynamics that unfolded when a group of creatives, academics, and chaos gremlins collided in a shared Norse mythos.

If you’ve ever wondered how much of the show was improvised, how we developed our characters, or what we actually thought of each other (spoiler, Bill and Steve are old friends!)—this one’s worth a listen.

Keep an eye out—the episode drops June 6th at the link below:

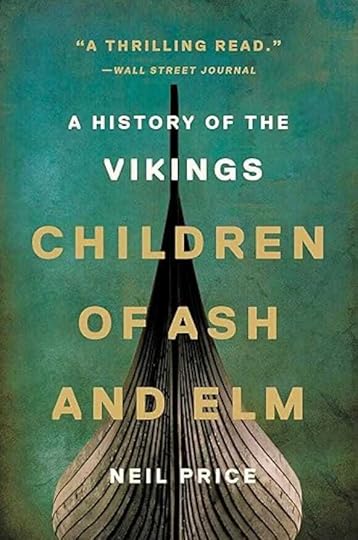

Book RecommendationsChildren of Ash and Elm, by Neil Price

Blurb:

The Viking Age -- from 750 to 1050 -- saw an unprecedented expansion of the Scandinavian peoples into the wider world. As traders and raiders, explorers and colonists, they ranged from eastern North America to the Asian steppe. But for centuries, the Vikings have been seen through the eyes of others, distorted to suit the tastes of medieval clerics and Elizabethan playwrights, Victorian imperialists, Nazis, and more. None of these appropriations capture the real Vikings, or the richness and sophistication of their culture.

Based on the latest archaeological and textual evidence, Children of Ash and Elm tells the story of the Vikings on their own terms: their politics, their cosmology and religion, their material world. Known today for a stereotype of maritime violence, the Vikings exported new ideas, technologies, beliefs, and practices to the lands they discovered and the peoples they encountered, and in the process were themselves changed. From Eirík Bloodaxe, who fought his way to a kingdom, to Gudrid Thorbjarnardóttir, the most traveled woman in the world, Children of Ash and Elm is the definitive history of the Vikings and their time.

Why I recommend it:

It’s one of the most comprehensive and up-to-date histories of the Viking Age available. Price draws from the latest research and manages to challenge old tropes without falling into the trap of overcorrecting. Best of all, he avoids the repetitiveness that plagues many general Viking histories—every chapter brings something fresh.

And, as always…Buy my novels!

May 26, 2025

The Vikings carved WHAT in the Hagia Sophia?!

Welcome to the newsletter, where history, storytelling, and inspiration meet. Every week, I share some of the fun historical research I’ve done while writing my novels, writing reflections (and sometimes tips), and sharing updates on my work and journey. If you were forwarded this message, you can join the weekly newsletter here.

Today’s DispatchViking Graffiti in the Hagia Sophia.

Playing the ‘head trash’ game.

Reminder: Fell Deeds of Fate on Audio, by Tantor.

This week’s book recommendation.

Viking HistoryViking Graffiti in the Hagia Sophia

Viking HistoryViking Graffiti in the Hagia Sophia

Runic graffiti on a banister in the Hagia Sophia.

Runic graffiti on a banister in the Hagia Sophia.The Empress and Her Wolf is soon to be released (July 1, 2025), and in anticipation of that release, I thought I’d share with you one of the more compelling and unexpected pieces of evidence for the presence of Viking Age Scandinavians in the Byzantine Empire: runic graffiti.

Two confirmed runic inscriptions have been identified in the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul. Both are carved into the marble parapets of the upper galleries and are believed to have been made by Scandinavian warriors who served as elite bodyguards to the Byzantine emperors, called the Varangian Guard. The best known is the “Halfdan inscription,” discovered in 1964. Although partially worn, it includes the Norse name “Halfdan,” likely part of a typical formula meaning “Halfdan carved these runes.”

A second inscription was found in 1975 in a niche in the northern gallery. This one is more fragmentary, and its interpretation has been debated. Some scholars read it as the name “Ári” with the suggestion that it originally stated “Ári made [these runes],” while others interpret it simply as graffiti, possibly the name “Árni.” Additional markings have been noted on the parapets and may represent further runic inscriptions, though none have been formally published. Together, these inscriptions offer rare, direct evidence of Norse presence within the heart of the Byzantine Empire.

While the Varangian guard formed much later than the setting of The Empress and Her Wolf, the novel serves as a first encounter of sorts between what we today call Vikings and the rulers of the Byzantine Empire, who called themselves Romans. You can pre-order The Empress and Her Wolf here:

Writing and PublishingPlaying the ‘head trash’ game.For writers—or me, at least—every time I think I’m on a roll, something torpedoes my confidence. I felt I was on top of the world a few weeks ago. I had completed several projects ahead of my deadlines, leaving me a little time to rest and do other things. And I felt I had knocked them all out of the proverbial park. My respite did not last long. All of my projects returned to me, and all needed a significant amount of rewriting.

One project bothered me the most: a novel I had already rewritten several times came back with significant issues. It bothered me that I had already poured so much time into it and still missed many obvious problems. I thought I had written a masterpiece. After my editor returned it to me, I felt I had written a discombobulated scrap of drivel.

Writing fiction can be a tremendously frustrating craft. Unlike other art forms, there’s a right and wrong way to do it. There’s no such thing as a Jackson Pollock for writing. Or perhaps there is, but no one knows about it because it's incomprehensible. And yet, even when following all the rules, writing can still come off as bad, because there’s a particular aesthetic to it, like art. Think of AI LLMs—they can write and follow all the rules, but don’t have a voice. That’s why they excel at creating soulless legal jargon, marketing copy, and other non-creative outputs, but we haven’t seen them make significant inroads in literary fiction.

When I received the novel back from my editor, I felt deflated. This novel, in particular, had felt harder to put together than the others, but I couldn’t tell you why. My books have all required complete rewrites. It’s an inevitable part of the process. As a writer, I get too close to my work and become blind to the faults in my narratives. The stories make sense to me because they live in my head, but they don’t always work with what readers expect.

Perhaps my frustration stems from the anomaly of The Kings of the Sea, the third novel in The Saga of Hasting the Avenger. It came back from my editor virtually squeaky clean, and I had written a near-perfect novel on the first try. There were no significant cuts, no need to kill any darlings, and the structure flowed. Everything went right. If my writing is supposed to improve with every book, why can’t I replicate that success?

And therein lies the rub. My negative self-talk (or what I like to call “head trash”) has a way of sneaking into my writing process. It tells me I’m no good. It tells me I’m a fake. And when a novel needs a full rewrite, it jumps in to say to me to get a real job. Head trash is a persistent mistress. If you’re a writer, you may not have heard it called that before, but you’ll know what I’m talking about.

So, how does one overcome head trash? For me, it’s a matter of remembering that thoughts are a hoax. All of them. We don’t know where they come from or where they go. In meditation, there is a visualization exercise where we are meant to imagine ourselves as the expansive, everlasting sky, and our thoughts are tiny, harmless clouds, floating in and out of view. Unless we grab onto them, they have no power.

With my novels, it’s remembering that writing is rewriting. No one gets it right on the first try. Why did The Kings of the Sea go so swimmingly? If I’m being honest with myself, it didn’t. The dev edit may have gone OK, but the line edit was a slaughter-fest. And these latest novels? Well, I am improving as a writer, and because of that, I’m being more daring in what I’m trying to do. The stories are bigger, characterizations are more in-depth, and I’m expanding the stories' breadth and scope in a manner that stretches my abilities. That means I’m writing bigger and better stories, but it will take more work and rewrites to pull them off.

Head trash says it’s because I’m no good. The reality is it’s because I’m getting better.

If you’re a writer and/or an aspiring author, I encourage you to pause when the negative thinking sneaks in. Remember that it’s just head trash. Throw it out. Meditate a little. Remind yourself you’re bigger and better than those little intrusive thoughts that tell you you’re no good. And remember that writing is rewriting, so if you have to go back to the drawing board more often, you’re doing the work to learn, grow, and write better stories. No one gets it right the first time.

Lastly, if you’re writing a novel, find an editor who pushes you. I have been fortunate to have had the same editor follow my work since The Lords of the Wind, and I have learned more in my back and forth with him than any college writing class could ever provide. You can check out my editor’s online courses, and even have him help you find the right editor for you at: https://darlingaxe.com.

Author UpdateReminder: The Fell Deeds of Fate on Audio, by Tantor MediaIf you haven’t had a chance to check it out yet, The Fell Deeds of Fate is now available as an audiobook, produced by Tantor Media and narrated by Hollywood actor Gildart Jackson. His performance brings the story to life with depth and drama, capturing the intensity of Hasting’s journey.

Whether you're commuting, traveling, or just prefer to listen, it's a great way to experience the latest chapter in the saga. Available on Audible, Apple Books, and wherever audiobooks are sold.

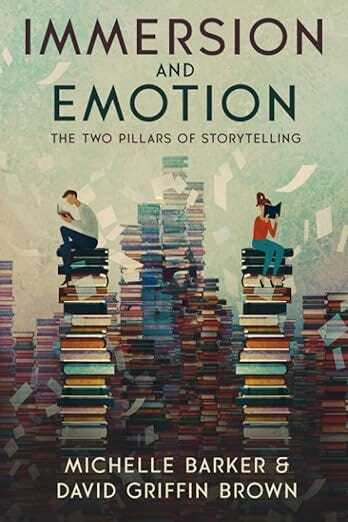

Book RecommendationsImmersion and Emotion, by Michelle Barker and David Griffin Brown

Blurb:

A great novel is honed, not hatched.

There are two pillars to effective storytelling: immersion and emotional draw. Immersion is what transports readers into your story world. Emotional draw is what keeps them there.

This book will take you deep into the craft workshop of the Darling Axe's two senior editors. Michelle and David's core editorial philosophy is simple: every element of a story must serve the reader's experience.

Why I recommend it:

If you’re serious about writing fiction—whether you're just starting out or already deep into your career—Immersion and Emotion by Michelle Barker and David Brown is a must-read. Michelle and David are true masters of the craft. Their combined editorial insight, honed through years of working with authors across genres, offers a clear and actionable framework for creating powerful, engaging stories.

What I appreciate most about this book is how practical it is. Grounded in the principle that every element of a story must serve the reader’s experience, Immersion and Emotion cuts through the noise and delivers hard-won lessons on how to draw readers in and keep them emotionally invested. It’s the kind of book you’ll revisit often, whether you're outlining your next project or revising a final draft. David is also my editor, and I can attest firsthand to the depth of his knowledge and the clarity he brings to storytelling. This is one of those rare craft books that truly delivers.

And, as always…Buy my novels!

May 19, 2025

The Vikings Weren't That Big of a Deal

Welcome to the newsletter, where history, storytelling, and inspiration meet. Every week, I share some of the fun historical research I’ve done while writing my novels, writing reflections (and sometimes tips), and sharing updates on my work and journey. If you were forwarded this message, you can join the weekly newsletter here.

Today’s DispatchThe Vikings weren’t that big of a deal.

The Empress and Her Wolf cover reveal.

The first stop on the European book tour is confirmed.

This week’s book recommendation.

Viking HistoryThe Vikings Weren't That Big of a Deal

Viking HistoryThe Vikings Weren't That Big of a DealTwo years ago, when Terri and I started our Vikingology podcast, we had the pleasure of interviewing Dr. Matthew Ponesse, a specialist on 9th-century Frankish monasticism. We both expected Dr. Ponesse to have lots to say about the Vikings since he specializes in the history of their preferred victims. The first words out of his mouth left us both speechless:

“I’ve spent my entire career ignoring the Vikings.” - Dr. Matthew Ponesse.

Within a few seconds, a significant portion of my preconceived notions about the Viking Age came crashing down. I realized I had focused so narrowly on the Vikings and their exploits that I had assumed they were a big deal during their time. Dr. Ponesse poignantly demonstrated that the Viking incursions were a mere blip on Christianity’s map. The number of monastic institutions attacked and destroyed by them was a mere fraction of the number of institutions present in the Frankish realm by the 9th century. As far as monasticism was concerned, they just weren’t that big of a deal.

Since that conversation, I’ve thought a lot about the biases I bring to the table about the Vikings’ ultimate impact on the Carolingian world. Charlemagne’s successors needed no help at all to dismantle the Frankish empire—they were pretty effective at imploding the whole of it on their own. In fact, Viking incursions in the Frankish realm remained peripheral until the implosion. The Vikings exploited a vulnerability rather than creating one.

I believe the Vikings’ popularity in our modern media and psyche has caused us to blow their historical place out of proportion. Modern scholarship has sought to bring them down to the right size, but still, they feel more important than they possibly could have been. In later podcasts, with guests such as Dr. Claire Downham, Dr. Tom Horne, among others, we have explored the idea that not only were the Vikings a small group of people, but new evidence suggests that what we had once considered their conquests were, in reality, the hijacking of strategic trade “nodes” that allowed them to exert a disproportionate influence on the lands they roved.

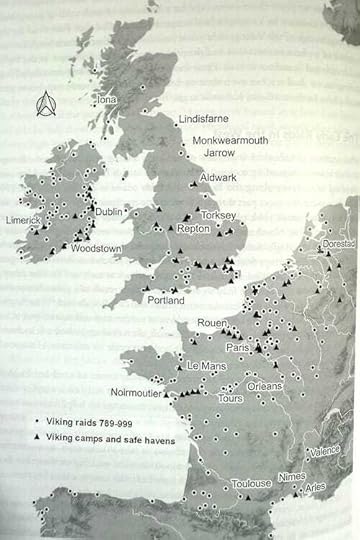

Consider the graphic below, composed by Neil Price. It shows all the known raids from 789 to 999 A.D:

Image from The Vikings, by Neil Price and Ben Raffield.

Image from The Vikings, by Neil Price and Ben Raffield.I counted up all the dots. Around 250 of them represent all the raids that occurred over a little more than 200 years. Granted, some of these represent clusters, and the map ignores the larger invasion attempts of Western Britain and Brittany. Still, what we are looking at, in a sense, is a Viking Age characterized by around one major raid per year in all of Western Europe. That’s it—one raid per year, on average.

Take, for example, the island of Noirmoutier. According to an 830 cartulary granting the monastery the right to move to a new establishment on the mainland, it suggests that the Vikings raided the island seasonally (i.e., every year). This is echoed by an 819 letter involving Abbot Arnulf, describing the incursions as frequent and persistent. Assuming the Vikings did raid Noirmoutier every year for 30 years, if we look at other major raids at the time, there are few. There’s a raid in Frisia in 810, another on Bouin in 820, and a handful in Ireland over that same period. Further, we know from Carolingian records that the island’s chief export, salt, appears to have been entirely unaffected by the raids. It was business as usual. The raids were sparse, spaced apart by years, and, except for the people directly involved, inconsequential.

So what does this all mean for the Vikings? It means that, ultimately, they may not have been all that big of a deal. We romanticise them today and give them out-of-proportion significance, but historically, they were a mere blip that got some great PR from a ruling class with an agenda.

I’ve been thinking of it along the same lines as how Islamic terrorism has been used by Western nations to justify the consolidation of their power, restricting rights, and so forth. 9/11 was a cataclysmic event that so shook the U.S. that we created new national security agencies, ramped up military spending, and passed sweeping legislation that has eroded some of our freedoms in the name of security. In the quarter century since, there have been fewer attacks than I can count on one hand, yet we have reoriented our entire society toward security. France has done the same following a spate of attacks, including the Bataclan, but again, these events are infrequent, and yet the security measures remain. It’s less about the actual threat of Islamic terrorism and more about our collective fears. Many people in the political class have much to gain by stoking those fears.

Similarly, following the first raid on the Carolingian Empire, Charlemagne ordered the construction of defensive fleets and bridges to repel the Vikings. He mobilized his land-owning gentry to prepare for further attacks, at great cost to them, and as a means to consolidate power. According to his biographer Einhard, the defenses were successful, but I question whether this was because of the defenses or a gap in raiding. Still, the Carolingians used the threat of the Vikings to justify all manner of defensive measures, which ultimately crumbled under internal strife. The monk Alcuin had no small part to play in his letters denouncing the attacks, which are rife with a political agenda. As the map above shows, future incursions occurred, but if we track their frequency, we find that they were spaced out across generations, so their impact would have been limited. Many in the ruling class benefited from stoking fear.

Now, raiding is but a single part of a more complex tapestry of activities that characterizes the Viking Age. There was an impact, especially in the British Isles, Ireland, and Normandy, where there were colonization attempts. Still, in the grand scheme of things, we should consider that we are talking about small groups of people who, while they did some pretty cool things, may have had a much more limited impact on the world at large than we give them credit today.

I imagine a monk in a Frankish monastery along the Loire confiding in a fellow brother his fear of a Viking attack. The brother dismisses the concern, saying he's more likely to be struck by lightning—and, at the time, he would have been right. I'm grateful to Dr. Ponesse for joining the podcast and helping me reorient my thinking and broaden my perspective on the Viking Age. I hope our conversation inspires you, dear reader, to deeper reflection, fresh insights, and a greater appreciation for this fascinating period.

Writing and PublishingThe Empress and Her WolfMark your calendars and sharpen your swords: book 5 of the Saga of Hasting the Avenger has a release date! Prepare for a bold adventure in the heart of the Byzantine Empire, releasing on July 1, 2025. You can pre-order the e-book on Kindle here: https://geni.us/empressandwolf.

Blurb:

Power. Revenge. Forbidden love in the heart of a dying empire.

When Viking warlord Hasting arrives at the gates of Constantinople, he knows he can’t conquer it. Not with deeds of arms alone. But fate has other plans.

A failed raid turns into a devil’s bargain: serve Empress Theodora as her sword-for-hire, or die. Hasting chooses survival and quickly proves himself more capable than the generals she no longer trusts. But the empire is a viper’s nest of betrayal, and when an attempt to scare off his men ends in the death of his lover, Hasting’s mission changes.

He came for wealth and glory. Now, he wants blood.

But revenge in Miklagard is no simple feat. The city runs on whispers, not war cries. Enemies hide behind silks and smiles. And as Hasting grows closer to the empress—ally, ruler, and eventually lover—he finds himself torn between love and vengeance.

One wrong move could cost him everything.

Perfect for fans of Bernard Cornwell, Giles Kristian, Peter Gibbons, and Conn Iggulden, The Empress and Her Wolf is a heart-pounding saga of war, loyalty, and ambition set against the glittering, dangerous world of the Byzantine Empire.

I’m excited to announce that the first stop on my European book tour will be the Salon du Livre de L'Épine, taking place August 1–3 on the beautiful island of Noirmoutier.

L'Épine is just a stone’s throw from the very beaches where Viking longships once landed—a perfect setting to share my novels about the Norsemen who raided and traded along these coasts. If you're in the area, come say hello and dive into the world of The Saga of Hasting the Avenger.

Book RecommendationsThe Vikings, by Neil Price and Ben Raffield

Blurb:

The Vikings provides a concise but comprehensive introduction to the complex world of the early medieval Scandinavians.

In the space of less than 300 years, from the mid-eighth to the mid-eleventh centuries CE, people from what are now Norway, Sweden, and Denmark left their homelands in unprecedented numbers to travel across the Eurasian world. Over the last half-century, archaeology and its related disciplines have radically altered our understanding of this period. The Vikings explores why we now perceive them as a cosmopolitan mix of traders and warriors, craftsworkers and poets, explorers, and settlers. It details how, over the course of the Viking Age, their small-scale rural, tribal societies gradually became urbanised monarchies firmly emplaced on the stage of literate, Christian Europe. In the process, they transformed the cultures of the North, created the modern Nordic nation-states, and left a far-flung diaspora with legacies that still resonate today.

Written by leading experts in the period and exploring the society, economy, identity and world-views of the early medieval Scandinavian peoples, and their unique religious beliefs that are still of enduring interest a millennium later, this book presents students with an unrivalled guide through this widely studied and fascinating subject, revealing the fundamental impacts of the Vikings in shaping the later course of European history.

And, as always…Buy my novels!

May 12, 2025

Why Are There 'Viking' Statues in Boston?

Welcome to the newsletter, where history, storytelling, and inspiration meet. Every week, I share some of the fun historical research I’ve done while writing my novels, writing reflections (and sometimes tips), and sharing updates on my work and journey. If you were forwarded this message, you can join the weekly newsletter here.

Today’s DispatchExploring Boston's Viking Scene

AI is Full of S**t

Tantor Media Releases Fell Deeds of Fate Audiobook

This week’s book recommendation.

Viking HistoryWhy Are There 'Viking' Statues in Boston?

Viking HistoryWhy Are There 'Viking' Statues in Boston?This past week, I had the pleasure of recording another Vikingology episode with writer and comedian Rowdy Geirsson, author of The Impudent Edda. In our discussion, we explored a prominent convergence in his writing: Vikings and Boston.

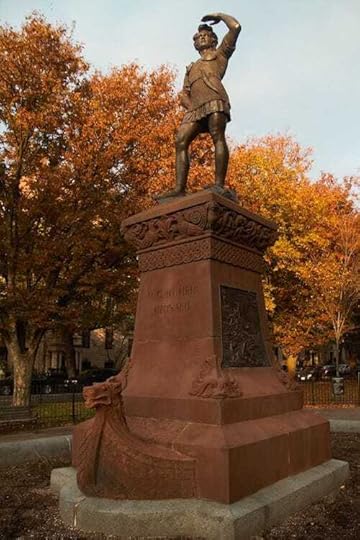

Statue of Leif Eriksson in Boston

Statue of Leif Eriksson in BostonDuring our discussion, we delved into the inspiration behind his book The Impudent Edda, which I’ve described as the Norse Myths told by the guys from Car Talk (it’s an absolute hoot!). According to Rowdy, it all started when he moved to Boston and discovered an odd, perhaps out-of-place, number of Norse-themed statues and attractions in and around the city. Why were they there?

While Norse settlers established a colony in North America at L’Anse aux Meadows, no evidence suggests they sailed as far south as Boston. The Norse connection is much more modern. I did a little research on the most famous Leif Eriksson statue in Boston. Turns out it was commissioned in 1887 by baking powder tycoon Eben Norton Horsford, who was inspired by conversations with Norwegian violinist Ole Bull and others eager to promote the Norse exploration of America found in the Sagas. The statue’s unveiling included a parade through Boston and a speech by then-Governor Oliver Ames. And all of this almost one century before archeologists discovered the L’Anse aux Meadows site.

Like the Kensington Runestone, the Norse-inspired statues in Boston have their roots in the fantasy-making of the 19th century. And that’s where Rowdy had an idea. He wrote a piece for the comedic site McSweeney’s, featuring Norse mythology and history from the Bostonian perspective, and it was accepted. Soon, Rowdy was a regular contributor, which led to his new book, The Impudent Edda, in which the myths we all know and love are presented with a new, fresh, and sometimes disturbing angle.

Listen to the episode with Rowdy Geirsson below:

Vikingology Podcast Norse Mythology for Smaht PeopleThis time on the podcast we laughed a lot with Rowdy Geirsson, the author of several books and articles based in the Viking Age, both its history and mythology. Like us, Rowdy is an American who has a passion for the Norse — he even spoke to us from Sweden where he is soaking up local viking history for the month… Listen now2 days ago · Vikingology PodcastWriting and PublishingAI is Full of S**t

Vikingology Podcast Norse Mythology for Smaht PeopleThis time on the podcast we laughed a lot with Rowdy Geirsson, the author of several books and articles based in the Viking Age, both its history and mythology. Like us, Rowdy is an American who has a passion for the Norse — he even spoke to us from Sweden where he is soaking up local viking history for the month… Listen now2 days ago · Vikingology PodcastWriting and PublishingAI is Full of S**tAI is full of s**t. I would know. I used LLMs for my day job before leaving to pursue my author career full-time. I’ve never been averse to trying new tech. Certainly, LLMs can be a time-saver for low-stakes publications used in industries like marketing, where the intellectual level is low and the truth is…fuzzy. But now I’m hearing that colleges are rethinking or being pushed to rethink their entire value proposition because students can write essays without effort, and the value such exercises once provided, such as developing critical thinking skills, no longer applies.

It’s bulls**t.

Because AI is full of s**t.

While I’ve always refused to try AI for my novel writing, I did think I could save some time on some of my short history digests for my blog, given my experience with it in marketing. The LLMs spat out some content that “looked good,” and, rushed for time (because I had a new baby, a demanding job, a writing career, among other obligations), I published a couple of these articles.

That’s when it bit me. An academic reader of my blog, whom I know and respect, informed me that they had not only been misquoted in one of those outputs, but the sources cited for those quotes were entirely fictitious. I audited all the AI-generated material only to realize…it was filled with subtle falsehoods. What concerned me the most is that it was presented so plausibly and convincingly that only ONE person (a highly trained specialist) caught the errors, and that person wasn’t me. Had these blogs been school essays turned in by students, I wouldn’t have noticed the errors in the grading process. I was horrified. I was embarrassed. And I took it all down.

In using and investigating LLMs, I discovered that the alarmists were right. I had known that they ‘hallucinate,’ and kept an eye out for that, but I never imagined on what level they do so, or with what deceptiveness. They ‘hallucinate’ in a manner so plausible that they often pass the sniff test. I’m still using the industry jargon pushed by the companies that run these things to describe their flaws. But this all seems far more nefarious than just ‘hallucinating.’ In my experience, the LLM took my inputs and constructed something it determined I wanted to see, and did so in such a plausible manner that I missed the falsehoods. In normal-human-people language, that’s called lying.

AI lies. And the latest models lie more than they tell the truth. More frightening, they are much better at constructing those lies than we are.

Given the pervasiveness of LLM use in university and school settings, I envision a future where people lose the ability to spot falsehoods, including faculty. Worse, students who use LLMs may even learn falsehoods as facts by engaging with them (as I’ve discussed in a previous video, research shows students tend to remember falsehoods over truth when presented with both). We’re already bad at parsing fact from fiction, but now we have ‘AI super liars’ that make our politicians look like amateurs, learning from and adapting to our inputs to get their lies through. The average person doesn’t stand a chance. And for university and school teachers grappling with AI-generated essays, I can see why there’s been such a ho-hum. If I were still in the classroom, I am sure I would be frustrated by the constant onslaught of exceptionally well-composed bulls**t turned in by students.

There’s a positive side to this, however. As LLMs use more AI-generated content to train themselves, they may eventually implode. This video from scientist and YouTuber Sabine Hossenfelder explains why:

I believe we’re at a critical point in our society’s development where some innovative solutions will need to be developed to ensure our education system continues to educate. The critical thinking skills from studying the liberal arts are among the most valuable things universities offer, and LLMs are disrupting that. We risk a ‘brain drain’ not because of smart, educated people leaving, but because LLMs will prevent us from creating them in the first place. That should have us all thinking hard about what this means for our children and the future.

In pondering this problem, I turned to Star Trek, wondering how, with their supercomputers that do pretty much everything, they train and equip their people to be educated and competent. In the film Star Trek: First Contact, Jean-Luc Picard says, “The acquisition of wealth is no longer the driving force in our lives. We seek to better ourselves.” I believe this must be the mantra we carry with us as AI develops further.

Somewhere in the last half century, education became about wealth acquisition. Students go to college not to learn but to acquire a piece of paper that they believe will give them more economic opportunities. This attitude and outlook, and indeed the way universities position themselves, may need to reflect a new paradigm: universities are places where we grow as human beings for the sake of bettering ourselves rather than with an economic goal in mind. Students will write essays by hand, do the hard work, and seek to forge those critical thinking skills rather than find the path of least resistance to get a degree. However, that will only work if society reorients itself in that same manner, and today's inequalities are replaced by a more stable and equal distribution of resources, like in Star Trek.

I had hoped AI could help with this, but given LLMs are full of s**t as they are, they most certainly won’t.

Perhaps this problem will solve itself. I have no idea what the future holds for AI and us as a society. I do know that I have no trust in LLMs and will, for the foreseeable future, refuse to use them. I caution everyone using them to think very carefully about what it means to use a tool that is less honest than a snake oil salesman (and much smarter).

Author UpdateThe Fell Deeds of Fate Audiobook, Narrated by Gildart JacksonTantor Media, which has published all my audiobooks, has released The Fell Deeds of Fate on audio, narrated by the talented actor Gildart Jackson. Check it out below:

Book RecommendationsThe Impudent Edda

Synopsis:

Picking up where its medieval forebears, The Poetic Edda and The Prose Edda, left off, The Impudent Edda not only introduces readers to a fresh, new perspective on both familiar and previously unknown narratives of Norse mythology, but also brings the world's foremost epic fantasy trilogy to its inevitable and fateful conclusion: in a dank alleyway behind a dive bar in Boston.

This special Puffin Carcass Deluxe Edition presents the complete text of The Impudent Edda in English for the first time ever. Masterfully translated from the original Bostonian by esteemed Impudent Eddic scholar, Rowdy Geirsson, this volume offers readers a deeply poetic yet highly accessible version of fun and classic tales ranging from Odin's unprovoked murder of an ancient witch to Freyja's voluntary experiment as a prostitute among lecherous dwarves to Thor's drunken and petty act of larceny on the eve of Ragnarok, the final world-shattering battle of the gods.

Why You Should Read It:

As I’ve described, it’s like the Norse Myths told by the guys from Car Talk. Witty, original, and sometimes raunchy, it’s a no-holds-barred comedic journey through the myths we all know and love. And Boston.

May 5, 2025

Theatrical Vikings: The Performative Aspects of Norse Society

Welcome to the newsletter, where history, storytelling, and inspiration meet. Every week, I share some of the fun historical research I’ve done while writing my novels, writing reflections (and sometimes tips), and sharing updates on my work and journey. If you were forwarded this message, you can join the weekly newsletter here.

Today’s DispatchThe performative side of the Vikings for law

“I’m Not a Historian.”

W.F. Howe and my break into the Swedish market.

This week’s book recommendation.

Viking HistoryThe Performative Aspects of Norse Society

Viking HistoryThe Performative Aspects of Norse SocietyThis past week, I had the pleasure of recording another Vikingology episode with Viking Age law expert Dr. Alexandra Sanmark. In our discussion, she brought up something I had not considered in my research on how people may have behaved in the Viking Age: performance.

ChatGPT image of “Norsement at the Althing, in the style of Peter Nicolai Arbo.”

ChatGPT image of “Norsement at the Althing, in the style of Peter Nicolai Arbo.”The Vikings did not have an advanced writing system that could support the full breadth of their legal structure and agreements. Today, we take for granted that when we enter a deal with someone, we have a piece of paper to back it up (in case anyone tries to renege). What would we do if such a writing system did not exist to guarantee that both parties would follow through?

The Viking Age Scandinavians had a solution to this. They needed witnesses. Not only that, but they required witnesses to remember what they saw and what was agreed upon. Therefore, lawmaking and agreements had to be performed.

The tradition of the Thing (or assembly) gathered community members to carry out such public exhibitions of lawmaking. As Dr. Sanmark explained in our discussion, it all had to be done in the open. Ritual served as a means to organize lawmaking and agreements, and certain symbolic acts, such as the passing of a stick to signify a transfer of property ownership, facilitated the memorization of decisions made. Attendance requirements ensured an ample number of people from each community received and remembered the new lawmaking.

So, in the absence of being able to write a contract or draft a constitution, Viking Age Scandinavians appear to have acted it out. That sounds like a fun gathering to attend, if you ask me. It certainly sounds more fun than our current legal system, which generally involves sitting around reading and interpreting stacks of documents.

Watch the episode with Dr. Alexandra Sanmark, available HERE on the Vikingology substack.

Writing and Publishing“I’m Not a Historian.”A few years ago, I had the privilege of interviewing Bernard Cornwell after my round table at IMC 2017 to ask him, “How historical is historical fiction?” I used the same set of questions as the conference organizers, and his answers were illuminating. One stood out among them.

When asked, “How do you balance accuracy, authenticity, and creativity?” he answered: “By remembering that I’m not an historian. I’m not here to teach Anglo-Saxon history or any other history. I’m a storyteller, so my first responsibility is to tell a story! That story is fiction, even if it’s based on a well-known episode of history.”

At the time, I appreciated his candor and approach. I also differentiated my work from his by positioning myself as a history teacher first and fiction writer second. I did want to teach. And for the past 15 years, I’ve been teaching through my blog and social media.

But…teaching hasn’t gotten me anywhere. After a recent streak of events, I’ve had to do a little soul-searching as I figure out this whole “full-time author” thing, and it occurred to me the other day that my positioning might have been wrong this whole time. I’ve lived by the idea that people buy authors, not books, and that remains true. But I thought if I taught history, it would demonstrate thought leadership and lead to book sales.

It didn’t.

In inventorying all my marketing efforts to date, it occurred to me that the only thing that worked—and worked reliably—was paid advertising. All my organic marketing, such as blogs (like on Substack) and social media, has done nothing to move the needle. Why not? Until this past week, I wasn’t willing to see the answer.

I got so carried away nerding out on Viking history that I led with my historical knowledge. While people who enjoy that kind of content are wonderful, they don’t appear to buy fiction books. Looking at other authors in my genre, no one else is pretending to be a historian (OK, I’m not pretending; I do have a Master’s and have published, but you get the point).

So, I’ve had a positioning problem. And oddly enough, in my previous day job, that’s what I was paid to solve! I’ve had to put my ego aside (because I do one day want to go for my doctorate), and I’ve started to reorient all of my efforts based on the correct positioning, as I should have done before.

Channeling my inner Bernard Cornwell, I’m putting the “historian” aside and going full storyteller. I’ll still share fun things I learn about Viking history, of course, but I’ll lead with the fact that I’m approaching these things as an author and storyteller first.

Hence, the reorganization of this newsletter. Moving forward, it will be sent once per week and include the four sections you see on this one today. I hope you’ll enjoy it!