C.J. Adrien's Blog, page 5

April 7, 2025

Exciting News: I'm Now a Full-Time Author (and Why I'm Leaving Amazon)

Hello friends and readers,

Big news from my end! I'm officially going full-time as an author. Yes, you heard right—no more juggling writing alongside other jobs, side hustles, or whatever else kept me away from my keyboard. I'm all in, ready to dive deeper into the worlds of history, Vikings, and everything else that inspires my storytelling (and, let's be honest, my occasional nerdy ramblings).

But that's not all. I've decided to stop exclusively selling my books on Amazon. Why? Let's just say Amazon and I had a good run, but like many relationships, we grew apart. I'm excited to announce my new partnership with Books.by, a platform that lets me connect directly with you—without the algorithms, hidden fees, or middlemen trying to play matchmaker between us.

Here's what's in it for you:

Easy and direct access to my books.

Exclusive behind-the-scenes updates (aka the good stuff).

Special offers, signed editions, and book bundles you can't get anywhere else.

I'm also thrilled to share that I'll soon be relocating to France! This move will enable me to be on-site for deeper research (and maybe even pursue that PhD I've been considering). I've signed on with Vent-des-Lettres, my fantastic publisher in France, and will attend book fairs this summer in Guerande, Noirmoutier, and several other locations. I've recently signed a contract with W.F. Howe to publish my books in Swedish, which is opening exciting new opportunities.

Speaking of book fairs, I'm planning to attend events in Edinburgh, Reykjavik, Frankfurt, and more over the next six months, so there's a good chance we'll cross paths somewhere!

One quick favor: If you've enjoyed my books, please share them with anyone you think might also like them—friends, family, coworkers, your dentist... anyone! Your recommendations help more than you know.

If you'd like to support my work further, please consider becoming a patron by signing up for my Substack Founders Plan for $500. This support will go a long way toward helping me continue my writing career, and as a thank you, you'll receive signed copies of "The Fell Deeds of Fate" and the complete "Saga of Hasting the Avenger," AND (if you’re up for it) I’ll write you in as a character in a future book. Not you, exactly, but a fictionalized version of your likeness. You may choose the gruesome manner of your own death in the story.

Thank you all for your support. Check out my new author page at BooksBy:

Cheers,

C.J. Adrien

This Substack is reader-supported. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

April 3, 2025

Vous Pensez Vouloir Être un Viking ? Cette Étude sur Leurs Dents Pourries Devrait Vous Faire Changer d’Avis

Pendant des années, les historiens ont cru que la santé bucco-dentaire n’était pas si mauvaise avant l’introduction du sucre de canne. On supposait que les premières populations avaient des dents relativement solides et moins de caries sans les aliments transformés modernes. Il existait même une loi dans l’Angleterre médiévale selon laquelle une femme pouvait divorcer de son mari s’il avait une mauvaise haleine, preuve que l’hygiène dentaire était importante, du moins à cette époque.

De nouvelles recherches suggèrent que les Scandinaves de l’ère viking avaient leur lot de problèmes dentaires bien avant que le sucre ne devienne un coupable majeur. Une étude récente utilisant la tomodensitométrie (scanner CT) sur des crânes datant de l’époque viking, retrouvés à Varnhem, en Suède, révèle une vérité choquante : les Vikings — du moins ceux de cette région — souffraient de graves problèmes dentaires, notamment d’infections, de caries et de troubles de la mâchoire qui rendaient la vie quotidienne misérable.

Révéler la Santé des Vikings Grâce à l’Imagerie CTLa recherche archéologique s’est longtemps appuyée sur l’analyse ostéologique traditionnelle, c’est-à-dire l’examen des os à l’œil nu sous une lumière intense, pour comprendre les populations du passé. Cependant, l’imagerie par tomodensitométrie (CT) offre une vue non invasive et extrêmement détaillée des restes squelettiques, révélant des informations au-delà de ce que l’on peut voir à l’œil nu.

Dans une étude exploratoire publiée le 18 février 2025, des chercheurs ont analysé 15 crânes provenant d’un site chrétien de l’époque viking à Varnhem, en Suède (Xe–XIIe siècle apr. J.-C.). L’objectif était de déterminer si l’imagerie CT pouvait révéler des pathologies cachées échappant aux méthodes d’examen traditionnelles.

Réalisée par des spécialistes en radiologie orale et maxillo-faciale, l’étude a mis en évidence toute une gamme de troubles orofaciaux et squelettiques suggérant que ces individus vivaient dans un inconfort important, voire une souffrance constante. Parmi les découvertes clés :

1. Problèmes Dentaires et AlvéolairesCaries dentaires : présentes chez 27 % des individus, ce qui indique un régime alimentaire contenant des glucides, probablement du pain ou de la bouillie.

Maladie parodontale (des gencives) : observée chez 66 % des individus, en particulier sur les molaires.

Infections apicales (à la racine des dents) : pas moins de 80 % des crânes présentaient des signes d’infections profondes qui auraient causé douleurs et enflures.

Perte de dents : plusieurs individus avaient perdu des dents avant leur décès, dont un complètement édenté (plus une seule dent !).

2. Troubles de l’Articulation Temporo-Mandibulaire (ATM)Plus de la moitié des individus montraient des signes de dégénérescence articulaire, notamment :

Formation d’ostéophytes (excroissances osseuses)

Aplatissement du condyle (érosion de l’articulation de la mâchoire)

Perte de l’os cortical

Sclérification (durcissement de l’os mandibulaire)

Ces symptômes suggèrent des douleurs chroniques, de l’arthrite ou une usure due à la mastication fréquente d’aliments coriaces.

3. Sinusite Chronique et Infections de l’OreilleTrois individus présentaient des signes de sinusite, probablement liés à des infections respiratoires, dentaires ou à des facteurs environnementaux comme les foyers enfumés.

Un individu présentait une sclérification du processus mastoïdien, indiquant un historique d’otites chroniques — une affection qui, non traitée, pouvait être mortelle.

4. Autres Pathologies : Traumatismes, Infections et Réactions OsseusesDes signes d’infections non traitées suggèrent que certains individus ont souffert de douleurs aiguës, voire de complications systémiques potentiellement mortelles, à une époque sans antibiotiques.

La détérioration des articulations et le remodelage osseux laissent penser que certains vivaient avec des affections similaires à l’arthrite, probablement aggravées par le travail physique et l’alimentation.

Pourquoi Cette Étude Est-elle Importante ?Si les problèmes dentaires et squelettiques observés dans les crânes vikings peuvent sembler dérangeants, le véritable objectif de l’étude n’était pas simplement de les recenser. Ces pathologies étaient déjà connues grâce à des recherches antérieures.

L’étude visait plutôt à déterminer si la tomodensitométrie (CT scan) pouvait offrir des aperçus plus profonds sur des affections que les méthodes ostéologiques et radiographiques traditionnelles pourraient manquer.

En scannant 15 crânes de l’ère viking à Varnhem, les chercheurs ont évalué la capacité des CT scans à révéler des changements structurels cachés, des infections internes et d’autres conditions invisibles à l’examen standard.

Les résultats montrent clairement que les scanners CT permettent une analyse plus fine, révélant des signes d’infections profondes, de remodelage osseux et de dégénérescences subtiles difficiles, voire impossibles, à détecter autrement. Cela confirme que l’imagerie CT est un outil non invasif précieux pour faire progresser l’étude des restes anciens, offrant aux archéologues et aux chercheurs médico-légaux une fenêtre plus claire sur la santé des populations du passé.

L’Étude Ne Portait Pas sur des Dents Pourries… Mais Elle Les a Bien Mises en LumièreBeaucoup de gens m’ont demandé si je voulais vivre à l’époque viking, ou si j’aurais aimé y vivre. Nous avons répondu à cette question dans le podcast Vikingology. Certains reconstituteurs et passionnés d’histoire répondent oui, mais cette étude montre pourquoi c’est une idée terrible.

Quatre-vingts pour cent des crânes présentaient des maladies dentaires sévères. Infections, abcès, maladies des gencives, détérioration de la mâchoire — ces gens étaient rongés par la douleur.

Beaucoup souffraient de douleurs chroniques, sans autre solution que des extractions rudimentaires ou le silence. Certains avaient des infections osseuses pouvant entraîner des complications mortelles.

Imaginez-vous vous réveiller chaque jour avec une rage de dents violente, sans espoir de soulagement ni de traitement.

Personnellement, je n’ai aucune envie de remonter le temps. Sans la médecine moderne, je n’aurais même pas survécu à l’enfance.

J’adore étudier l’ère viking, mais je préfère rester ici, avec mes antibiotiques, mes dentistes et mes antidouleurs.

This Substack is reader-supported. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

April 2, 2025

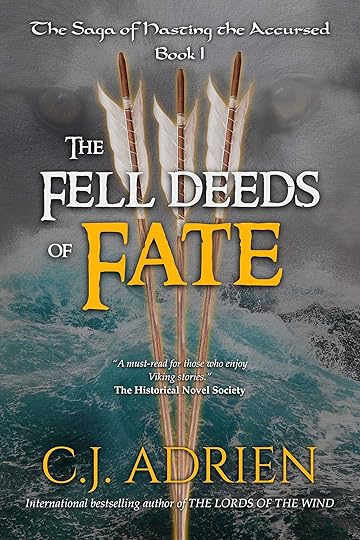

Available for Pre-Order: The Fell Deeds of Fate on Audiobook

Hello, my ravenous seekers of knowledge! I come to you bearing tidings of great events soon to pass. The Fell Deeds of Fate, my fourth novel with the Viking Hasting as the protagonist, has just become available for pre-order on Audible. It is due to release on May 6th, so sound the gjallarhorn and take your place among the daring warriors seeking to conquer Constantinople alongside one of the most notorious Vikings of them all.

About Gildart Jackson

About Gildart JacksonGildart Jackson is a British actor and acclaimed audiobook narrator known for his distinctive voice and masterful storytelling. He has appeared on hit TV shows such as Charmed, Supernatural, and The Bold and the Beautiful, bringing a charismatic presence to every role. As a narrator, he has lent his voice to hundreds of titles, captivating listeners with his refined delivery and rich character work. Gildart previously brought the entire Saga of Hasting the Avenger to life, earning praise from fans for his immersive performance. Now, he returns to narrate The Fell Deeds of Fate, continuing his collaboration with C.J. Adrien to deliver an unforgettable Viking adventure.

From the Inside Flap:For Hasting the Avenger, fame and glory were supposed to last forever.

Two years after the legendary sack of Paris, Hasting remains haunted—not by his triumph but by the bitter twist of fate that Ragnar’s name made it into the songs of the Skalds and not his. Drowning in resentment and drink, he has become a shadow of the Viking warrior he once was. When his wife divorces him, strips him of his wealth, and takes his son, Hasting’s world collapses around him.

Then, a chance reunion with his old comrade Bjorn Ironsides sparks an audacious idea. He will outdo Paris by accomplishing something so grand and unforgettable that the world will never again question his legacy. His target: Miklagard, the Great City of Constantinople.

Driven by a desperate need to prove his worth, Hasting embarks on an epic journey across roiling seas, icy rivers, and untamed lands, rallying old allies and clashing with powerful new rivals. To succeed, he must confront the root of his obsession with immortality and the cost it demands, not only of himself but of those who follow him.

The Fell Deeds of Fate is the first book in The Saga of Hasting the Accursed, a bold, gripping new Viking trilogy that welcomes new readers and fans of C.J. Adrien's award-winning series Saga of Hasting the Avenger. Whether you're starting fresh or continuing Hasting's story, this Viking epic promises a tale of courage, redemption, and the battles we fight within ourselves.

C'MON, PRE-ORDER IT ON AUDIBLE

Praise for the Fell Deeds of Fate:Kirkus Reviews: "Richly developed fictional adventures of a real Viking on an epic journey through Europe. Our verdict: Get it!"

The Book Commentary: "The Fell Deeds of Fate is richly detailed, conveying the harsh truths of Viking life and the visceral landscape of Northern Europe. From fierce ocean battles to intimate moments of domesticity, Adrien creates a world where the elements play an integral role in shaping the characters' fates, reflecting the brutal yet vibrant nature of the Viking Age. The prose is delectable, and the overall writing is cinematic."

Reader's Favorite Book Reviews: "The Fell Deeds of Fate is a masterful blend of historical fiction and mythological undertones, making it a must-read for fans of Viking tales and epic sagas. Adrien crafts a world as brutal as it is captivating...highly recommended."

Johanna Wittenberg, author of The Norsewomen series: "Fell Deeds of Fate is a thrilling action tale that leads us through the eastern Viking lands, leaving us breathless by the end."

Ian Stuart Sharpe, author of The Vikingverse: "CJ Adrien's Fell Deeds of Fate is a riveting journey through time, delivering a Viking Age saga for the ages. A masterwork filled with thrilling encounters and dramatic twists that holds you captive till the very last page."

J.M. Gillingham, author of the Ten-Tree Saga: "C.J. Adrien has laid forth another saga worthy of the heroes of old. With many narrative tie-ins and continuations from Adrien's The Saga of Hasting the Avenger trilogy, new and old fans are in for a ravens-feast of sharpened steel, shining silver, and long-hidden secrets!"

SERIOUSLY, JUST PRE-ORDER IT ALREADY!

PRAISE FOR C.J. ADRIEN

"C.J. Adrien places the reader into the thick of the tale...A must-read for those who enjoy Viking stories." - The Historical Novel Society

"C.J. Adrien packs a full force of realistic history and excellent knowledge into his novels." - Reader's Favorite

"C.J. Adrien steeps us in period detail and political backbiting in a richly imagined world." - Kirkus Reviews

March 31, 2025

New Viking Age Discovery Is Largest Hall Ever Found in Britain

In the quiet fields of High Tarns Farm, tucked into the Solway Plain of Cumbria, archaeologists have made a discovery that may add a significant piece to the puzzle of Viking Age Britain. A monumental timber hall has come to light, stretching 50 meters in length and 15 meters in width. Radiocarbon dating places the structure between the years 990 and 1040, placing it squarely in the late Viking Age. According to Grampus Heritage and Training, the organization behind the excavation, this is the largest Viking Age building ever found in Britain.

Archeologist Mark Graham (upper left) and volunteers at the dig site. Photo credit: The Grampus Heritage Foundations. Click the photo to see more.

Archeologist Mark Graham (upper left) and volunteers at the dig site. Photo credit: The Grampus Heritage Foundations. Click the photo to see more.The discovery's scale is significant. It may help illuminate the social and economic structures of early medieval northwest England and provide a fresh perspective on the influence and organization of Scandinavian culture in the region during a time of great transition.

Want more Viking-related discoveries, new research, and unique perspectives? Get this newsletter direct to your inbox —>

The story of the discovery began in late 2022 when researchers from Grampus Heritage were reviewing open-access aerial photographs of the Tarns area. They were searching for crop marks—changes in vegetation that often signal archaeological features hidden beneath the soil. Their goal was to locate signs of a grange farm linked to Holme Cultram Abbey, which was established nearby in the twelfth century. Instead, they noticed an extensive, rectangular outline that didn’t match the usual layout of a monastic site.

In the spring of the following year, a geophysical survey confirmed anomalies worth exploring. With help from the West Cumbria Archaeological Society, the team conducted magnetometry and resistance surveys. This effort led to a full excavation in the summer of 2024, funded by a grant through the Farming in Protected Landscapes program. More than 50 local volunteers joined the dig.

Two trenches were opened. In the first, they uncovered a series of large postholes arranged in a pattern that matched the crop mark seen from above. These postholes outlined a timber hall with a triple-aisle design and ten distinct bays. Radiocarbon samples taken from one of the main support posts returned a date range from the turn of the eleventh century, confirming its place in the Viking Age.

The second trench, dug a short distance to the south, revealed a well-built grain dryer. The structure included access steps, stone-lined walls, a clay and cobble drying chamber, and the remains of an arch over the stokehole. Archaeologists also uncovered a charcoal production pit within the same trench that predates the kiln. The grain dryer was dated to the middle of the eleventh century, while the charcoal pit had a broader range stretching back into the tenth century.

These features suggest the presence of a manor farm, a type of estate often found in Viking Age Denmark. The term refers to a large hall and a rural complex tied to agricultural production, social hierarchy, and land management. Though the excavation did not yield artifacts like coins or tools, the structural evidence alone may offer insight into the lives of those who lived and worked here.

The absence of cultural material was expected. The soil conditions at High Tarns are not kind to organic preservation, and years of plowing have erased many of the upper occupation layers. Ironically, this lack of surface debris made the crop mark visible and led to the site's discovery.

Even without artifacts, the find is an important addition to what we know of Anglo-Scandinavian culture in this part of England. Cumbria is already known for its Scandinavian place names and dialect influences. Hogback stones found in churchyards across the region depict longhouse-style buildings and are often thought to represent elite Viking halls. The hall at High Tarns may be one of those buildings.

Mark Graham, the project manager from Grampus Heritage, emphasized how rare it is to find tangible evidence from this period in the region. Holme Cultram Abbey and other institutions were built atop older settlements, and this layering of history tends to hide what came before. Discoveries like High Tarns offer a glimpse into a time before the Norman conquest when Scandinavian influence was still strong in the area.

What stands out most about this story is not just the scale or age of the building but also the way it was discovered. More than fifty volunteers from the local area took part in the excavation. They dug in poor weather, sifted through gravel, and uncovered each posthole with care and determination. This is a shining example of citizen archaeology at its best. When local communities are given the chance to participate in research, incredible things can happen.

The contrast with much of the rest of Europe is also worth noting. Archaeological work is heavily restricted and tightly controlled in countries like France, Germany, and Poland. While these rules ensure professional oversight, they also tend to limit community involvement and slow the pace of discovery. How many Viking Age halls remain hidden in the countryside of Normandy or Pomerania because there’s no system to allow for this kind of grassroots investigation? We discussed this issue in two recent Vikingology Podcast episodes with Leszek Gardela and Tom Horne.

In England, the steady stream of extraordinary finds—hoards, longships, burials, and now this hall—reflects a national policy that encourages public engagement. When professionals and passionate volunteers come together, history has a way of revealing itself. The hall at High Tarns may have stood in silence for a thousand years, but now it speaks again—thanks in no small part to a community that cared enough to dig.

Want more Viking-related discoveries, new research, and unique perspectives? Get this newsletter direct to your inbox —>

March 29, 2025

From Birka to Disney+: The Rise of the Viking Warrior Woman

I finally got around to watching Viking Warrior Women, the 2019 National Geographic documentary now streaming on Disney+. The film, hosted by Ella Al-Shamahi, explores the increasingly compelling evidence that some women in Viking Age Scandinavia took on martial roles.

It centers on the now-famous Birka warrior grave in Sweden. It also investigates similar high-status female burials in Denmark and Norway—each containing weapons and clues that challenge our assumptions about gender roles in the Viking world.

A Strong Start

A Strong StartAl-Shamahi is an engaging and charismatic presenter, and the film is visually stunning. It moves at an appropriate pace while highlighting some of the most exciting discoveries in Viking archaeology in recent years.

I especially appreciated the segment with Leszek Gardeła—a friend of the Vikingology Podcast—who analyzes the axe found in the Danish grave. He confirms it's a war axe, not a domestic tool, which is a significant distinction. The implication that this woman was at least partially engaged in martial activity is fascinating and worth further investigation.

Where It StumblesWhile Viking Warrior Women succeeds in drawing attention to overlooked stories in the archaeological record, it does suffer from a persistent flaw: a tendency to jump to conclusions that aren't fully supported by the evidence.

Al-Shamahi, while passionate, seems too eager to confirm her preexisting beliefs. She repeatedly states what she “believes” to be confirmed before presenting the data and then frames the evidence to support those beliefs—often ignoring more nuanced or cautious interpretations. She even says at one point, “I choose to believe,” in offering her conclusions about the grave site in Norway.

As a further, more emblematic example, the documentary ends with a facial reconstruction of the Birka warrior woman, whose skull bears a healed cranial injury. This moment is framed as a triumphant “proof” that she saw battle. The so-called “battle wound” on the Birka skull is treated uncritically as proof of combat experience, despite the fact that such an injury could just as plausibly have resulted from domestic violence or an accident.

Similarly, the sequence at Repton with Dr. Cat Jarman implies that female remains in a military burial automatically equates to female warriors. Yet Jarman’s own book clarifies that many women likely accompanied the Great Heathen Army as part of family groups and that Viking armies often traveled with entire households.

The documentary misses a valuable opportunity to clarify the distinction between the evidence and the presenters' beliefs, which adds to a growing tendency to treat possibility as proof.

The TakeawayAll said, the broader implications of the archaeological findings are thought-provoking. For instance, the osteological analysis of the Birka skeleton revealed that spinal and shoulder wear is consistent with a life of archery. That kind of evidence is hard to ignore.

Taken together with weapon burials, grave prominence, and new typologies of martial objects, we're beginning to see a clearer picture: at least a few women in the Viking Age appear to have taken on roles traditionally associated with men.

This doesn’t mean Viking society was egalitarian or that shieldmaidens were the norm. But it does mean that the social roles available to women may have been more flexible than previously thought—and that’s incredibly exciting.

Final ThoughtsIn the end, Viking Warrior Women is a compelling watch. Despite its flaws, it shines a spotlight on an important and evolving field of study. Just don’t take all its conclusions at face value. It is, after all, entertainment.

March 19, 2025

A History Teacher’s Perspective on America’s Swing Toward Oligarchy—And How It Might Tip Into Authoritarianism

For decades, American politics has been shaped by a deep fear of authoritarianism, particularly the kind associated with state-controlled economies like the Soviet Union and Maoist China. Policymakers and economists warned that too much government intervention in the economy could lead to political oppression, just as it had in past communist regimes. In response, the U.S. took a dramatically different approach: deregulation, privatization, and a commitment to free markets. These policies were meant to protect individual liberty by limiting the state's power.

While the U.S. successfully avoided the left-wing authoritarianism of centralized socialism, it may have paved the way for a different kind of autocracy—the rise of right-wing authoritarianism through economic oligarchy. Over time, the same economic policies designed to prevent tyranny have created a new ruling class: a small group of ultra-wealthy elites with disproportionate influence over government, elections, and public policy.

This phenomenon can be explained through the Horseshoe Theory, a political concept suggesting that the far left and far right, despite their differences, often arrive at the same outcome: authoritarian rule. This article explores how unchecked power, whether in the hands of the state or private elites, leads to the same fundamental problem: the erosion of democracy and concentration of control in the hands of a few.

To understand this, we’ll first look at the work of key political thinkers—such as Robert Michels, James Burnham, and Friedrich Hayek—who warned about how socialism and unregulated capitalism can lead to oppression. Then, we’ll examine how Marxism and extreme libertarian capitalism share a key flaw: the belief that societies will "self-regulate" without centralized control. Finally, we’ll explore historical examples of authoritarianism emerging from both left-wing and right-wing systems before turning to the U.S. experience where deregulation that began in the Reagan era has led us toward economic oligarchy and, potentially, a new form of authoritarian rule.

If history has taught us anything, it’s that power, once concentrated, is seldom given up willingly. By fearing one form of tyranny, the U.S. may have unknowingly set itself up for another.

Disclaimer:

Who am I to write this article? Usually, I write about Vikings and historical fiction. Still, before I was a novelist, I was a history teacher—and before that, I wrote my bachelor’s thesis on Russian political culture during the Bolshevik Revolution. While my academic focus has primarily been on medieval history, studying past societies—how they functioned, collapsed, and wielded power—offers invaluable lessons about the present. As I’ve heard said before: history does not repeat itself, but it rhymes. And I see troubling echoes of past authoritarian shifts in today’s political landscape.

Beyond my professional background, I’ve always been a political junkie. I decided to write this article because I frequently hear people across the political spectrum make misguided and historically inaccurate claims about authoritarianism, capitalism, and socialism. These misconceptions are frustrating and they reveal a widespread lack of education on how power consolidates, regardless of ideology. Given my history, teaching, and political analysis background, I felt a responsibility to step outside my usual writing topics and offer a historian’s perspective on what I believe is happening today.

I’ve also found a general aversion to broaching this topic. Why are we, Americans, so unwilling to talk openly about it? One of the main reasons I believe we seldom discuss the rise of right-wing authoritarianism through economic oligarchy is the long-standing American tendency to conflate capitalism with freedom. A significant portion of the population believe that free markets inherently guarantee political liberty, even when economic power becomes concentrated. Compounding this issue is the fact that U.S. political discourse has been dominated by the fear of left-wing authoritarianism. From McCarthyism to the Reagan era and beyond, the specter of socialism has been repeatedly invoked to justify deregulation and privatization, reinforcing the idea that big government is the greatest threat to democracy. At the same time, the dangers of corporate monopolization and economic capture of the state have been ignored. Finally, there is a deep-seated reluctance to acknowledge systemic failure in a country built on the ideals of liberty and self-governance. Recognizing that the United States is not immune to the same authoritarian patterns that have emerged elsewhere forces Americans to confront uncomfortable realities about who holds power, how policies are shaped, and whether democracy has already been eroded. Many would rather cling to the myth of American exceptionalism than acknowledge the warning signs staring them in the face.

The History of Horseshoe Theory: How Both Ends Swing Toward AuthoritarianismThe Horseshoe Theory challenges the conventional idea that political ideologies exist on a simple left-right spectrum, where democracy holds the center, and extremism resides at either end. Instead, it proposes that when political movements reach their most extreme forms, they bend toward each other, like the ends of a horseshoe, arriving at a shared destination: authoritarian control. Despite their differences in rhetoric and economic policy, radical left-wing and right-wing ideologies have historically produced strikingly similar methods of governance, characterized by centralized power, suppression of dissent, and the concentration of authority in the hands of a small ruling elite.

This theory is not merely a product of modern political analysis but has been explored for over a century. One of the earliest thinkers to describe how democratic and socialist movements evolve into oligarchies was Robert Michels, a German-Italian sociologist who in 1911 published Political Parties: A Sociological Study of the Oligarchical Tendencies of Modern Democracy. Michels observed that all large organizations, regardless of their ideological foundations, eventually become dominated by a small elite class. His work introduced the Iron Law of Oligarchy, a principle that has since shaped political science and organizational theory.

Michels argued that democratic movements, including socialist parties, start with an egalitarian vision but require structure and leadership to function as they grow. The individuals who take on leadership roles develop specialized knowledge, control access to decision-making, and, over time, become self-perpetuating elites. Even in organizations claiming to represent the working class or "the people," these leaders inevitably prioritize maintaining their influence. Michels saw this pattern unfold in European socialist parties, where revolutionary ideals gave way to rigid party hierarchies that functioned much like the governing elites they initially opposed. His work laid the foundation for later theories that examined why all systems, left or right, tend toward concentrated power.

Three decades later, in 1941, political theorist James Burnham expanded on this idea in The Managerial Revolution. Burnham had been a committed Marxist but grew disillusioned with communism and came to believe that both capitalist and socialist systems ultimately led to the rule of a managerial elite. In his view, neither economic system distributed power among the people. Instead, in capitalist societies, corporate executives and financiers dominated economic and political life, while in socialist systems, bureaucrats and central planners occupied the same role. The outcome was the same: a select group of decision-makers controlled society, leaving ordinary citizens little influence.

Burnham’s predictions resonated with the realities of the Soviet Union and Western democracies in the mid-20th century. While the USSR was ostensibly a workers’ state, it had become a rigid one-party system where power rested with Communist Party officials rather than the proletariat. At the same time, in the United States and Western Europe, economic decision-making was increasingly dominated by a professional managerial class—corporate leaders, policymakers, and financial elites who dictated economic policies in ways that often ignored the general population's interests. Burnham’s work reinforced the idea that, regardless of whether a system was built on state control or free markets, power remained in the hands of a small group at the top.

Not long after Burnham, economist Friedrich Hayek, in his 1944 book The Road to Serfdom, offered a different but complementary warning about the dangers of centralized power. Hayek’s concern was that when governments exercise excessive control over the economy, they inevitably restrict political freedoms. He argued that state-directed economies require coercion, as authorities must enforce production goals, redistribute wealth, and suppress economic competition. The result, he warned, was an expanding bureaucracy that gradually eroded civil liberties.

Although Hayek’s primary focus was the risks of socialism, later critics pointed out that his warnings applied just as much to unchecked capitalism. If left entirely unregulated, market economies tend toward monopolization, where wealth and power are concentrated in the hands of a few corporations. These entities, in turn, begin exerting control over government policy, the media, and even public discourse, mimicking the centralized power of a totalitarian state. In this way, Hayek’s argument about state control leading to political oppression could just as easily be applied to corporate monopolies capturing political institutions, demonstrating yet another way Horseshoe Theory plays out in real-world governance.

While thinkers like Michels, Burnham, and Hayek laid the groundwork for understanding how power consolidates across different political systems, Jean-Pierre Faye, a French philosopher, formally coined the term Horseshoe Theory in the 1970s. Studying extremist movements in Europe, Faye noted that radical left-wing and right-wing groups often mirrored each other in their structure, rhetoric, and methods of control. Despite claiming to be ideological opposites, these movements engaged in the same tactics of mass propaganda, censorship, and political purges, all justified in the name of “protecting the people” or “defending the revolution.” This process is playing out in France’s current political crisis, where the far-right and far-left parties joined forces to win a vote of no confidence against the current centrist government. It appears they have taken to heart that they share the same goal, albeit wish to reach via differing routes.

Faye’s research demonstrated how both communist and fascist regimes relied on scapegoating enemies to consolidate power—whether it was capitalists and aristocrats in communist revolutions or ethnic and ideological minorities in fascist takeovers. Both sought total control over society, eliminating political opposition and suppressing free speech in the name of national or class unity. His work solidified the idea that when political movements become too extreme, their primary concern shifts from governance to control, erasing the ideological distinctions that initially set them apart.

In recent years, scholars like Niall Ferguson and Nassim Nicholas Taleb have revisited these ideas, arguing that the modern world is seeing a new kind of power consolidation that transcends traditional political labels. Ferguson has pointed out that corporate monopolies, particularly finance and technology, now wield as much power as nation-states. Governments, once intended to act as a counterweight to economic power, are increasingly co-opted by corporate interests, leading to what he describes as a new form of oligarchy, where business leaders hold the same unchecked influence once associated with authoritarian rulers.

Conversely, Taleb has taken a more behavioral approach, arguing that modern institutions lack accountability among elites. Whether in government or business, those who hold power increasingly do so without facing the consequences of their decisions. It is a phenomenon that enables corruption, cronyism, and authoritarian governance. His critique aligns with the broader theme of Horseshoe Theory: the problem is not ideology itself but the concentration of power, which, once entrenched, inevitably leads to the suppression of democracy.

The historical record overwhelmingly supports this conclusion. Whether through state control in left-wing regimes or corporate dominance in right-wing systems, extreme ideologies have repeatedly produced authoritarian rule by a privileged elite. The key takeaway from more than a century of political thought is that unchecked power, in any form, is the real enemy of democracy. The following section will examine how this pattern has played out in history, providing concrete examples of nations that have followed both paths—toward left-wing totalitarianism and right-wing autocracy alike.

Marxism vs. Libertarian Capitalism: The Flawed Assumption That Society Will “Self-Regulate”Despite their stark ideological differences, Marxism and libertarian capitalism share a fundamental goal: the eventual abolition of the state. Marxists envision a future where class distinctions disappear, private property is abolished, and the state “withers away,” giving rise to a stateless, classless society where workers collectively own the means of production. Libertarian capitalists, on the other hand, seek to remove all forms of government intervention, arguing that the free market, unrestricted by state control, is the best mechanism for organizing society.

Both ideologies rest on the same flawed assumption: that society will naturally self-regulate once the state is removed. In Marxist theory, after the overthrow of capitalism, a transitional phase known as the "dictatorship of the proletariat" would be necessary to dismantle existing power structures and redistribute resources. This stage was intended to be temporary, leading eventually to full communism, where state control would become unnecessary as class distinctions disappeared. However, history has demonstrated that this “temporary” phase never ends (because, you know, humans!). Instead, the ruling party solidifies its control, the government expands rather than withers, and a new bureaucratic elite emerges that is more entrenched than the capitalist class it replaced.

In practice, Marxist revolutions have never resulted in a stateless society but heavily centralized regimes ruled by an elite few. The Soviet Union, Maoist China, and Castro’s Cuba all followed this trajectory: power became concentrated in a single party, which justified its rule by claiming that “true communism” had not yet been achieved. In each case, the ruling elite held total control over economic and political life, suppressing opposition to maintain the revolution.

Libertarian capitalism, while ideologically opposite in its rejection of state control, suffers from the same structural flaw. It assumes a wholly unregulated market will naturally prevent corruption, inefficiency, and monopolization. Yet history repeatedly demonstrates that markets do not remain competitive indefinitely without government oversight. Instead, more prominent players outcompete or absorb smaller ones, consolidating power into a handful of monopolies or oligopolies. Once economic power is sufficiently concentrated, corporate entities begin influencing, then effectively controlling, the government itself.

Modern Russia provides a compelling example of this process. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, the country rapidly transitioned to an extreme form of free-market capitalism characterized by mass privatization and deregulation. Rather than leading to a decentralized, competitive economy, this process allowed a small group of oligarchs to seize control of key industries, especially oil, gas, and banking, which gave them outsized influence over politics and media. Over time, the political system adapted to serve the interests of these economic elites, culminating in the consolidation of power under Vladimir Putin, an authoritarian leader who maintains control through the backing of Russia’s wealthiest business figures. The transition to market-driven democracy resulted in an oligarchic autocracy, where corporate and political power became the same.

Marxism and libertarian capitalism fail to account for one of the most consistent patterns in human history: power vacuums do not stay empty. When the state is dismantled or rendered ineffective, it does not lead to a utopian system of self-governance; it simply allows a new ruling class to emerge. Whether that ruling class consists of party officials or billionaire capitalists is irrelevant. The result is the same: a small elite monopolizes control. At the same time, the broader population is left without real power or influence.

The key takeaway is clear: unchecked economic or political power is always exploited.

Strongmen, the Left-Right Spectrum, and the Nature of Authoritarian RuleThroughout history, strongmen leaders have emerged from across the political spectrum, seizing power under the guise of national renewal, economic revival, or protection from internal and external enemies. While their ideological justifications vary, their methods are similar: cultivating a cult of personality, dismantling democratic institutions, suppressing dissent, and consolidating control over the military, media, and economy.

Understanding where these figures fall on the left-right spectrum requires distinguishing between economic theory and political theory. Economic systems, such as capitalism, socialism, and communism, deal with how wealth is produced and distributed, while political systems, such as democracy, authoritarianism, and totalitarianism, determine how power is exercised. A regime’s economic policies do not necessarily define its political structure, which is why authoritarianism can emerge from both socialist and capitalist systems.

Fascism provides a key example of how these forces interact. Initially, early fascist movements in the 1920s and 1930s contained elements of left-wing economic populism, such as opposition to financial elites, calls for state intervention in the economy, and appeals to workers. Benito Mussolini had been a socialist before breaking with the left. However, once in power, he aligned himself with conservative and corporate elites, using nationalism and militarism to suppress socialist and communist opposition. As a result, fascism, though having some leftist economic roots, became associated with extreme right-wing nationalism, racial hierarchies, and authoritarian governance.

This pattern repeats itself across history. Adolf Hitler’s Nazi Party initially appealed to working-class Germans by promoting state-led economic recovery but quickly turned into an ultra-nationalist, militarized dictatorship that crushed leftist movements. On the other hand, Joseph Stalin’s Soviet Union, while maintaining a state-controlled economy under Marxist ideology, functioned as a deeply authoritarian one-party regime that purged political rivals, controlled information, and employed mass surveillance—methods indistinguishable from right-wing autocrats. In China, Mao Zedong’s rule combined communist economic policy with ruthless political centralization, eliminating opposition in ways that mirror right-wing strongmen.

Even in recent decades, strongmen have appeared in various forms, from Vladimir Putin’s oligarchic autocracy in post-Soviet Russia to Jair Bolsonaro’s far-right populism in Brazil and Hugo Chávez’s left-wing authoritarianism in Venezuela. Despite differences in rhetoric and economic policy, these leaders follow the same authoritarian playbook by expanding executive power, curtailing freedoms, and ensuring their own dominance through force, propaganda, and institutional manipulation.

By examining these figures, it becomes clear that authoritarianism is not inherently left or right. It is a political structure that can arise under any economic system. While left-wing authoritarian regimes justify their control through class struggle and state economic control, right-wing regimes often do so under the banner of nationalism, corporate-state partnerships, and militarization (think, the military-industrial complex). In both cases, the result is the same: a concentration of power in the hands of a ruling elite, the suppression of opposition, and the erosion of democratic governance.

This distinction is crucial in understanding what is happening in the United States today. Many Americans are quick to recognize the dangers of left-wing authoritarianism, as seen in historical communist regimes, but they are far less willing to acknowledge the emergence of right-wing authoritarianism through corporate oligarchy and executive overreach. The refusal to recognize this threat allows it to take root unchecked, leading the country down a path that has played out too many times in history.

Historical Examples of Authoritarianism Emerging from the Far-Left and Far-RightThroughout modern history, nations have attempted radical shifts in governance, seeking to build societies based on ideological purity. These have taken the form of collectivist, state-controlled economies or deregulated, market-driven systems. However, the pattern from left-wing and right-wing revolutions is strikingly similar. Instead of achieving political or economic freedom, these systems produce authoritarian regimes ruled by a small elite. Whether under the banner of communism or fascism, both extremes have led to centralized power, suppression of dissent, and a monopolization of control that undermines democracy.

The Soviet Union is one of the most telling examples of how a workers' revolution can transform into an entrenched oligarchy. When the Bolsheviks seized power in 1917, they claimed to be establishing a society where the proletariat would rule, dismantling the old capitalist hierarchy in favor of collective ownership. However, what followed was not the dissolution of state power but its unprecedented expansion. The Communist Party, originally a vehicle for empowering the working class, quickly consolidated authority in the hands of a small political elite. Under Joseph Stalin, this authoritarian shift deepened, with state-controlled media, mass purges, and political repression becoming defining features of the regime. The institutions meant to ensure equality became tools of control, and the promised “withering away of the state” never materialized. Instead, the government became more powerful than ever, dictating every aspect of economic and social life.

A similar trajectory unfolded in Maoist China. After the Communist Party took control in 1949, Mao Zedong’s government launched massive state-driven economic projects like the Great Leap Forward, which led to widespread famine and suffering. To maintain control in the face of these failures, the regime turned to extreme political purges and cultural re-education campaigns, such as the Cultural Revolution, which sought to eliminate dissenters and consolidate Mao’s authority. The result was a totalitarian system where political loyalty was enforced through fear, surveillance, and ideological indoctrination. Instead of achieving a classless society, China became a state where a small group of party officials controlled all wealth and decision-making.

Russia also happens to be one of the best examples of how swinging too far in the other direction can land you in the same place. Like no other country in the world, they have experienced the full scale of horseshoe theory end-to-end. Following the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, the country rapidly transitioned from a state-controlled economy to an aggressively deregulated capitalist system. This shift was initially celebrated as a move toward democracy, but it enabled a handful of oligarchs to seize control of the country’s most valuable industries. Without strong institutional safeguards, these oligarchs accumulated immense economic power and used their wealth to influence politics, control the media, and silence opposition. Over time, this consolidation of economic control paved the way for Vladimir Putin’s autocratic rule.

Under Putin, the government has become deeply intertwined with corporate interests, ensuring that political power remains in the hands of a small elite. Opposition figures are routinely arrested or exiled, independent media has been dismantled, and democratic institutions have been hollowed out, all under the guise of national stability and economic strength. What began as an attempt to embrace free-market capitalism ultimately resulted in a corporate-backed dictatorship, where economic monopolization led directly to political authoritarianism.

The historical record is clear: whether a system starts from state control over the economy (far-left) or deregulated capitalism (far-right), the concentration of power inevitably leads to authoritarian rule. In both cases, power vacuums emerge, and rather than resulting in self-regulating freedom, these vacuums are filled by an entrenched ruling class that consolidates wealth, suppresses dissent, and ensures its continued dominance.

The following section will examine how the United States, in its effort to prevent left-wing authoritarianism, may have unknowingly set itself on a course toward right-wing oligarchy—one that mirrors the authoritarian models it sought to avoid.

The U.S. Shift Toward Oligarchy and Right-Wing AuthoritarianismFor much of the 20th century, the United States positioned itself as the global champion of free markets, limited government, and individual liberty in opposition to communism. During the Cold War, American policymakers, business leaders, and intellectuals warned that government intervention in the economy was the first step toward totalitarianism. This fear of creeping socialism led to a dramatic shift in economic policy, favoring deregulation, tax cuts for the wealthy, and expanding corporate power. While these policies were designed to prevent a left-wing authoritarian state, they created the conditions for a different form of autocracy, in which economic elites hold outsized political power and democratic institutions erode.

This transition began in earnest during the Reagan administration in the 1980s, when the federal government slashed taxes for the highest earners, eliminated regulations on industries such as finance, telecommunications, and healthcare, and promoted the idea that "big government" was the primary obstacle to economic growth. Reagan’s policies, rooted in neoliberal economic theory, were based on the assumption that reducing government oversight would lead to greater financial freedom and prosperity for all. Instead, deregulation allowed corporations to consolidate power, weaken labor protections, and dominate markets with little oversight.

The trend toward deregulation did not slow under the Clinton administration in the 1990s. Despite being a Democrat, Clinton embraced globalization and Wall Street-friendly policies, continuing many of Reagan’s deregulatory measures. Under Clinton, Glass-Steagall was repealed, allowing commercial banks and investment firms to merge, which laid the groundwork for the 2008 financial crisis. Meanwhile, media consolidation accelerated, with telecommunications giants merging to control vast portions of news and entertainment, limiting independent voices and increasing corporate influence over public discourse. By the turn of the century, a handful of corporations controlled the largest industries, from finance to healthcare to information technology.

The 21st century saw these trends accelerate, culminating in an economic order where corporate power dominates government policy. The 2008 financial crisis was the most glaring consequence of unchecked deregulation. The collapse was caused by banks engaging in reckless speculation, fueled by the assumption that the government would bail them out if things went wrong. When the crisis hit, it devastated the working and middle classes, yet the institutions responsible were rescued and became even larger and more powerful in the aftermath. This deepened the concentration of wealth, exacerbating the growing divide between economic elites and the rest of the population.

At the same time, the rise of technology monopolies—such as Google, Amazon, and Facebook—created new forms of concentrated power that now shape public discourse and political outcomes. These companies control access to information, communication, and digital marketplaces, making them more potent than many national governments. Their influence is economic and political, as tech billionaires fund candidates, shape election narratives, and suppress dissenting voices through algorithmic manipulation.

These policies have resulted in a staggering level of wealth concentration. Today, the wealthiest 1% of Americans control more wealth than the bottom 90% combined. Economic mobility has stagnated, and corporate lobbying has become so entrenched that elected officials answer more to donors than voters. Elections are increasingly dictated by billionaire-funded Super PACs, ensuring that policy decisions serve corporate interests rather than public needs.

As economic elites gain control over governance, the path toward right-wing authoritarianism becomes clear. Corporate consolidation leads to a captured state, where regulations are written by and for the wealthiest individuals and businesses. With control over the economy, media, and political system, the ruling class can shape public perception, suppress opposition, and legitimize policies that entrench their power. Dissent is neutralized not necessarily through violence, as in traditional authoritarian regimes, but through economic control, censorship, and political gatekeeping.

This erosion of democracy creates the conditions for populist strongmen to emerge, positioning themselves as anti-establishment figures who promise to “fix” the system. However, rather than dismantling oligarchic power, these leaders often consolidate it further, weaponizing nationalism, corporate influence, and media control to cement their rule. The result is a right-wing autocracy, where democracy exists in name only, and political power remains firmly in the hands of a minor, unelected elite.

The irony of this trajectory is stark. In its effort to prevent a left-wing authoritarian state, the United States has paved the way for an oligarchy that increasingly mirrors the autocratic systems it once opposed.

A Path to Authoritarianism, No Matter the RouteHistory has shown us that authoritarianism is not the exclusive product of one ideology or another. It is the inevitable result of concentrated wealth and power. Whether a society begins with state-controlled socialism or unregulated capitalism, the outcome is the same: a small ruling class monopolizes political and economic control, suppressing opposition and reshaping society to serve its interests. The Soviet Union, Maoist China, fascist Europe, and modern Russia all illustrate how the path to dictatorship is paved not simply by ideology but by the unchecked accumulation of wealth and power.

The fear of left-wing authoritarianism has long dominated political discourse in the United States. Throughout the 20th century, Americans were conditioned to believe that the greatest threat to democracy was state socialism—a system where government intervention in the economy inevitably leads to political repression. This fear, deeply ingrained in U.S. political culture, shaped economic policy for decades, leading to deregulation, privatization, and the erosion of government oversight. The result, however, was not a free and open society but the emergence of an economic oligarchy, where corporate elites wield as much, if not more, influence than elected officials.

Yet, this reality remains largely unspoken. Unlike the clear and present dangers of totalitarian socialism, which are widely condemned in American discourse, the creeping rise of right-wing authoritarianism through economic monopolization is rarely discussed in mainstream politics. The very idea that the U.S. system, structured around free markets and democratic elections, could lead to the same outcome as the systems it once opposed is an uncomfortable truth—one that many are unwilling to confront. Instead, discussions of authoritarianism remain fixated on the left, reinforcing the belief that only socialist policies lead to state control and suppression.

This unwillingness to acknowledge the dangers of corporate authoritarianism has allowed it to flourish unchecked. The concentration of wealth among a small elite has corrupted democratic institutions, captured regulatory agencies, and turned elections into contests of financial influence rather than public representation. Those in power, whether in government or the private sector, benefit from this arrangement and have little incentive to change it. Meanwhile, the public remains distracted by the boogeyman of socialism, unaware that an equally dangerous (if not identical) threat has been rising from the other side.

What can we do about it? Or is it too late? I recently finished Neil Howe’s The Fourth Turning is Here, and the central thesis is that all that is happening today is part of a repeating pattern, and we have arrived at the part called “The Crisis.” Think of it as an inevitable renewal of society, where social, political, and economic upheaval reach a critical mass, and the whole thing more or less blows up. If we look at the current swing of the U.S. and several other first world countries toward the right, it appears we are repeating a defined process.

The only way to prevent authoritarian rule is to strike a balance between the economy and governance. The Ancient Athenians understood this by saying, “There is no wealth without the Polis (the state), and there is no Polis without wealth.” Unfortunately, they, too, succumbed to authoritarian regimes. History is not full of stories of how democratcies managed to balance out without some major cataclysim. It could be that these are times and themes we cannot defy. Perhaps the proper response is to get ready to stand up—as our forebears did during the American Revolution, the Civil War, and World War II—when the time is right to help build what comes next.

What did you think of this content? Want to see more of it? Should I put a sock in it and stick to Vikings? Let me know in the comments below!

February 21, 2025

Think You’d Want to Be a Viking? This Study on Their Rotting Teeth Should Change Your Mind

For years, historians believed oral health wasn’t all that bad before the introduction of cane sugar. Early populations were assumed to have relatively strong teeth and fewer cavities without modern processed foods. There was even a law in medieval England where a woman could divorce her husband for having bad breath, so we know dental hygiene was important, at least by that time. New research suggests that Viking-era Scandinavians had their fair share of dental woes long before sugar became a major culprit. A recent study using computed tomography (CT) scans on Viking-age skulls from Varnhem, Sweden, reveals a shocking truth: Vikings—at least the ones in that region—suffered from severe dental problems, including infections, decay, and jaw issues that would have made everyday life miserable.

Unveiling Viking-Age Health Through CT ImagingArchaeological research has long relied on traditional osteological analysis, or examining bones with the naked eye under intense light, to understand past populations. However, computed tomography (CT) imaging provides a non-invasive and highly detailed view of skeletal remains, offering insights beyond what can be detected through visual inspection alone.

In an exploratory study published on 18 February 2025, researchers analyzed 15 skulls from a Viking-era Christian settlement in Varnhem, Sweden (10th–12th century AD). The goal was to determine whether CT imaging could reveal hidden pathological conditions that traditional examination methods might miss.

The study, conducted by specialists in oral and maxillofacial radiology, found a range of orofacial and skeletal conditions that suggest these individuals lived with significant discomfort if not outright suffering. Among the key findings:

1. Dental and Alveolar ConditionsDental caries (cavities) are found in 27% of individuals, highlighting a diet that included carbohydrates, possibly from bread or porridge.

Periodontal disease (gum disease): Present in 66% of the individuals, particularly affecting molars.

Periapical inflammatory disease (tooth root infections): A whopping 80% of the examined skulls showed evidence of deep infections that would have caused pain and swelling.

Tooth loss: Several individuals had lost teeth before death, with one completely edentulous individual (no teeth left!).

2. Temporomandibular Joint (TMJ) DisordersOver half of the individuals exhibited signs of joint degeneration, including:

Osteophyte formation (bone spurs)

Flattening of the condyle (jaw joint erosion)

Loss of cortical bone

Sclerotization (hardening of the jawbone)

These findings suggest chronic pain, arthritis, or wear from frequently chewing tough foods.

3. Chronic Sinusitis and Ear InfectionsThree individuals had sinusitis indicators, which could have been linked to respiratory infections, dental infections, or environmental factors like smoky indoor fires.

One individual showed sclerotization of the mastoid process, indicating a history of chronic ear infections (otitis media)—a condition that, untreated, could have been life-threatening.

4. Other Pathologies: Trauma, Infections, and Bone ReactionsEvidence of untreated infections suggests that some individuals may have suffered from painful, even deadly, systemic infections in an era without antibiotics.

Joint deterioration and bone remodeling suggest that some may have lived with arthritis-like conditions, likely exacerbated by physical labor and diet.

Why Does This Study Matter?While the dental and skeletal issues found in the Viking skulls may be unsettling, the true aim of the study wasn’t to catalog these conditions. They were already known from previous research. Instead, the study sought to determine whether computed tomography (CT) scans could provide deeper insights into pathologies that traditional osteological and radiographic methods might miss. By scanning 15 Viking-era skulls from Varnhem, Sweden, researchers aimed to assess whether CT imaging could reveal hidden structural changes, internal infections, and other conditions that might not be detectable through standard examination techniques.

The results strongly suggest that CT scans allow for a more detailed analysis, uncovering signs of deep infections, bone remodeling, and subtle degenerative changes that would have been difficult or impossible to observe otherwise. This confirms that CT scanning is a valuable non-invasive tool for advancing the study of ancient remains, giving archaeologists and forensic researchers a clearer window into the health of past populations.

The Study Wasn’t About Rotting Teeth, But It Certainly Shined a Light On ThemMany people have asked me if I want to go back to the Viking Age or if I wish I had lived there. We answered this on the Vikingology podcast. Some reenactors and history buffs say yes, but this study proves why that idea is terrible. Eighty percent of the skulls showed severe dental disease. Infections, abscesses, periodontal disease, and jaw deterioration plagued these people. Many suffered from chronic pain, with no way to treat it beyond crude extractions or suffering in silence. Some had bone infections that likely led to life-threatening complications. Imagine waking up daily with a raging toothache, knowing there was no cure, relief, or end. I have no interest in traveling back to that time. Without modern medicine, I would not have survived childhood. I love studying the Viking Age, but I will stay right here with my antibiotics, dentists, and painkillers.

February 6, 2025

New Discoveries Reveal the True Power of the Viking Great Army

Viking artifacts from Aldwark, North Yorkshire, amassed by US collector Gary Johnson. Photograph: Daniella Segura

Viking artifacts from Aldwark, North Yorkshire, amassed by US collector Gary Johnson. Photograph: Daniella SeguraThe Viking Great Army, or the "great heathen army" as recorded in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, was far more than a ruthless band of warriors ravaging Anglo-Saxon England. Newly uncovered sites and artifacts have revealed a more complex reality: the army was a diverse community of men, women, children, craftworkers, and merchants who transformed English society in ways previously underestimated.

A New Look at the Viking Presence in EnglandLeading experts from York University, Professors Dawn M. Hadley and Julian D. Richards, have traced the archaeological footprint of these Scandinavian invaders, identifying around 50 new sites associated with the Viking Great Army. By analyzing previously overlooked finds, such as ingots, gaming pieces, dress fittings, and Islamic dirhams, they’ve provided a clearer picture of how the Vikings operated and interacted with Anglo-Saxon England.

Hadley notes, "The finds reflect that the great army was not simply a military force but a community of men, women, children, craftworkers, and merchants. The new evidence reflects the wide range of activities undertaken at the camps, from creating metalwork to minting coins to engaging in trade."

Richards and Hadley’s research has uncovered strong evidence of Viking settlements beyond temporary military encampments. By comparing artifacts found across England to those from two major Viking camps—Torksey in Lincolnshire and Aldwark in North Yorkshire—they have mapped out key routes and transshipment points used by the Viking Great Army.

Artifacts Telling a StoryOne of the most fascinating discoveries includes gaming pieces believed to have been first manufactured at Torksey, later found at key Viking movement points more than 100 miles away. These pieces belonged to a strategic board game similar to chess, suggesting Vikings raided, fought, and engaged in leisure and intellectual pursuits.

The artifacts studied include dress fittings such as strap ends, exchanged bullion in the form of silver, gold, and copper-alloy ingots, and Islamic dirhams—coins acquired through trade with the Middle East. These finds demonstrate the Vikings’ extensive trade networks stretching from Ireland to the Islamic world.

A particularly striking discovery was made in Yorkshire, where a cross-shaped mount perfectly matched another half unearthed in Lincolnshire. This suggests that Viking warriors divided up the loot among themselves, each taking their share of the spoils of war.

Richards explains, "Many of the sites have not previously been published as Great Army sites by us or anyone else. Some of these suggest short periods of Viking activity, but in others, we argue that the Great Army started a period of enduring Scandinavian settlement."

The Great Heathen Army’s LegacyThe Anglo-Saxon Chronicles recorded the arrival of the Viking Great Army in 865 AD. Over the next 15 years, they waged war across East Anglia, Northumbria, Mercia, and Wessex, overthrowing kings, looting monasteries, and ultimately reshaping England. Over time, Viking leaders adopted Anglo-Saxon styles of kingship, converted to Christianity, and engaged in political diplomacy, leaving a permanent mark on the fabric of English society.

The new evidence challenges the traditional view of the Viking Great Army as merely a plundering force. Instead, it shows that many Vikings stayed, settled, and integrated into the local culture, leaving behind a legacy that still fascinates historians today.

Life in the Viking Great Army: Raiders, Traders, and Settlers – A Must-Read for Viking EnthusiastsFor those eager to dive deeper into this fascinating chapter of history, Professors Hadley and Richards have compiled their groundbreaking research into a forthcoming book, Life in the Viking Great Army: Raiders, Traders, and Settlers, set to be published by Oxford University Press in January. The book will feature many newly discovered sites and artifacts, including a fragment of scrap lead from Aldwark depicting Fenrir, the monstrous wolf of Norse mythology, and fittings from harnesses and sword belts.

In addition, previously unseen finds will be unveiled at the Yorkshire Museum’s new Viking display, opening in July 2025. The exhibition will showcase artifacts from an American collector, Gary Johnson, who has built a substantial collection of Viking-era items, including trade weights and Islamic silver coins. Johnson, who has generously loaned items for public display, remarked, "It’s fascinating to be holding something in your hand that’s 1,100 years old, knowing that it’s from Ragnarsson’s great heathen army. What more Viking-sounding phrases are there than the ‘great heathen army’?"

This new book and the upcoming exhibition will offer an unparalleled glimpse into the lives of the Vikings who transformed medieval England. Readers and museum visitors alike will be able to appreciate the breadth of Viking activities—from warfare and governance to craftsmanship and trade—showing that the Great Heathen Army’s impact was far more significant than previously imagined.

For more information and pre-ordering Life in the Viking Great Army: Raiders, Traders, and Settlers.

Want more Vikings? Buy my books! Click the image below:

February 3, 2025

La Querelle des Pierres de Jelling : La Norvège Défie l’Héritage Viking du Danemark

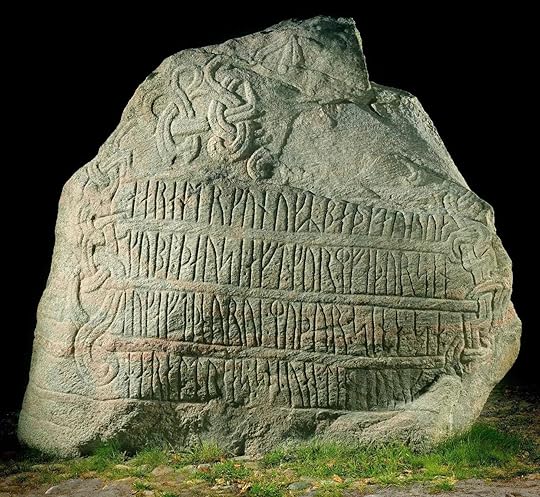

(Photo: Roberto Fortuna / National Museum of Denmark CC-BY-SA)

(Photo: Roberto Fortuna / National Museum of Denmark CC-BY-SA)Les pierres de Jelling, souvent appelées le "certificat de naissance" du Danemark, comptent parmi les artefacts les plus précieux de l’Âge Viking. Ces pierres runiques monumentales, érigées par le roi Gorm l’Ancien et son fils Harald à la Dent Bleue au Xe siècle, symbolisent la transition du Danemark vers le christianisme et l’unification du royaume. Elles sont classées au patrimoine mondial de l’UNESCO et constituent une source de grande fierté nationale.

Mais une nouvelle théorie de l’archéologue norvégien Håkon Glørstad a jeté une hache viking dans le récit officiel. Il affirme que l’une des pierres de Jelling ne date peut-être pas de l’Âge Viking mais aurait été commandée bien plus tard, au XIIe siècle. Cette déclaration a provoqué l’indignation des chercheurs danois, et le runologue Michael Lerche Nielsen a qualifié cette idée d’"absurde". Alors que les universitaires danois et norvégiens s’affrontent sur leur héritage, cette querelle autour des pierres de Jelling dépassera-t-elle le cadre académique ?

Le Défi Norvégien : La Théorie de Håkon GlørstadL’archéologue norvégien Håkon Glørstad remet en question l’appartenance de la grande pierre de Jelling à l’Âge Viking. Il propose que, plutôt que d’avoir été gravée à la fin des années 900, la pierre ait été commandée dans les années 1100 dans le cadre d’un effort médiéval de construction nationale.

Glørstad fonde son argumentation sur trois observations :

Orientation Horizontale du Texte : Contrairement à la plupart des pierres runiques de l’Âge Viking qui comportent un texte vertical, l’inscription de la grande pierre de Jelling est horizontale. Ce style était plus courant dans les inscriptions médiévales.

Éléments Stylistiques : Le résumé des réalisations du roi Harald sur l’inscription ressemble davantage aux dalles funéraires du XIIe siècle qu’aux gravures vikings traditionnelles.

Matériau et Iconographie : Le matériau de la pierre et la représentation d’un lion suggèrent une influence des motifs européens du XIIe siècle, une période où de telles images étaient plus typiques chez les monarques norvégiens et danois.

Glørstad reconnaît que sa théorie remet en cause des récits historiques bien établis, mais il insiste sur le fait que réexaminer les artefacts historiques est essentiel pour faire avancer la recherche archéologique. Pour lui, l’histoire ne doit pas être traitée comme un mythe national figé mais comme un domaine d’étude en constante évolution.

La Réplique Danoise : La Contre-Attaque de Michael Lerche NielsenLe runologue danois Michael Lerche Nielsen a contesté les affirmations de Glørstad. Sa réponse a été directe et sans appel, qualifiant la théorie d’"absurde d’un point de vue runologique".

Nielsen présente trois contre-arguments solides :

Analyse de la Langue Runique : Le langage de l’inscription est incontestablement de l’Âge Viking. Les évolutions linguistiques entre cette période et le XIIe siècle rendent improbable une création postérieure.

Contexte Historique : Alors que Glørstad cite l’orientation horizontale du texte comme preuve d’une date plus tardive, des découvertes récentes montrent que des pierres runiques de l’Âge Viking avec des inscriptions horizontales existent.

Preuves Archéologiques : Des décennies de recherche placent fermement les pierres de Jelling au Xe siècle. L’importance du site et son rôle dans la christianisation du Danemark par Harald à la Dent Bleue correspondent à cette datation.

Pour Nielsen, l’idée qu’un évêque du XIIe siècle ait pu commander la pierre de Jelling est historiquement inexacte ; elle remet en question des décennies de recherches archéologiques et linguistiques qui ont validé l’origine viking de la pierre.

Une Rivalité Nordique RavivéeÀ la surprise de certains (dont moi-même), les discussions en ligne autour de cette affaire semblent avoir ravivé la vieille rivalité culturelle entre le Danemark et la Norvège. J’ai moi-même été entraîné dans cette querelle en répondant aux commentaires de mon article Quelle était la différence entre les Vikings danois, norvégiens et suédois ?. Un commentateur norvégien est même allé jusqu’à m’accuser d’être danois ! (Je ne le suis pas, je suis français.) Les deux pays entretiennent une longue histoire de compétitions amicales (et parfois moins amicales) sur leur héritage viking. La Norvège cherche souvent à revendiquer son rôle dans l’histoire viking, remettant en question certaines affirmations danoises sur des artefacts et des récits historiques clés.

Les pierres de Jelling sont essentielles à l’identité danoise. Si la théorie de Glørstad devait gagner en crédibilité, le Danemark devrait reconsidérer un élément fondateur de son histoire nationale. Étant donné la forte opposition des chercheurs danois, cette théorie ne risque pas d’être largement acceptée de sitôt.

Cependant, ce débat pourrait faire avancer l’étude de l’Âge Viking. La popularité croissante de cette affaire pourrait attirer davantage d’attention sur le domaine et favoriser de nouvelles recherches. Si un holmgang (duel rituel viking) semble improbable, un affrontement académique pourrait renforcer l’image du domaine et offrir un aperçu fascinant de la manière dont nous établissons nos connaissances historiques.

Pourquoi Ce Débat Est ImportantBien qu’il puisse sembler s’agir d’une simple querelle académique autour d’un vieux rocher, la controverse sur les pierres de Jelling a des implications plus larges :

Interprétation Historique : Elle souligne la nature évolutive de l’archéologie et de la recherche historique. Même des faits établis peuvent être remis en question et réévalués.

Identité Nationale : Les pierres de Jelling sont plus que de simples artefacts. Elles représentent les fondations de l’histoire danoise, et en modifier la chronologie aurait un impact sur le récit national du Danemark.

L’Avenir des Études Vikings : Ce débat pourrait encourager de nouvelles recherches sur les pierres runiques, les inscriptions médiévales et l’histoire scandinave, approfondissant ainsi notre compréhension de l’Âge Viking et de ses répercussions.

La Pierre de Jelling Reste Debout Pour l’InstantLa pierre de Jelling a traversé un millénaire d’histoire et semble prête à résister à cette nouvelle controverse. Bien que la théorie de Glørstad représente un défi académique intéressant, les chercheurs danois y ont opposé des réponses solides, étayées par des preuves linguistiques et archéologiques. La grande pierre de Jelling restera un trésor viking du Danemark. Mais comme l’histoire l’a montré, aucun débat académique n’est jamais définitivement clos. Attendez-vous à de nouvelles discussions, recherches et confrontations nordiques dans les années à venir.

The Jelling Stone Feud: Danes and Norwegians Spar Over Viking Heritage.

(Photo: Roberto Fortuna / National Museum of Denmark CC-BY-SA)

(Photo: Roberto Fortuna / National Museum of Denmark CC-BY-SA)The Jelling stones, often called Denmark’s "birth certificate," are among the most treasured artifacts of the Viking Age. These monumental runestones, erected by King Gorm the Old and his son Harald Bluetooth in the 10th century, symbolize Denmark’s transition to Christianity and the unification of the kingdom. The stones hold UNESCO World Heritage status and are a point of immense national pride.

But a new theory from Norwegian archaeologist Håkon Glørstad has hurled a Viking Age axe into the narrative. He argues that one of the Jelling stones may not date to the Viking Age but was commissioned much later, during the 12th century. This claim has ignited outrage among Danish scholars, with runologist Michael Lerche Nielsen dismissing the idea as "absurd." As Danish and Norwegian academics spar over their heritage, will the debate over the Jelling Stones become more than an academic dispute?

The Norwegian Challenge: Håkon Glørstad’s TheoryNorwegian archaeologist Håkon Glørstad has questioned whether the large Jelling stone belongs to the Viking Age. He proposes that instead of being carved in the late 900s, the stone was commissioned in the 1100s as part of a medieval nation-building effort.

Glørstad’s argument is based on three observations: