The Paris Review's Blog, page 142

October 19, 2020

The Art of Distance No. 30

In March, The Paris Review launched The Art of Distance, a newsletter highlighting unlocked archive pieces that resonate with the staff of the magazine, quarantine-appropriate writing on the Daily, resources from our peer organizations, and more. Read Emily Nemens’s introductory letter here, and find the latest unlocked archive selection below.

“We are halfway through October and halfway through Edward P. Jones’s ‘Marie.’ (If you haven’t already, be sure to read part 1 and part 2 of the story.) In this week’s installment, Marie worries about the consequences of her outburst at the Social Security office and meets a surprise visitor who has come to hear the story of her life. Marie also pays a visit of her own to an ailing acquaintance as Jones offers community as an antidote to bureaucracy. Don’t forget that subscribers to the print magazine need only link their account for digital access to this whole story right now, in addition to a treasure trove of other stories, poems, landmark interviews, art portfolios, and more. May this week’s The Art of Distance offer you a brief respite from the intensities of election season and the anxieties of the pandemic.” —Craig Morgan Teicher, Digital Director

Photo courtesy of Evan-Amos / Wikimedia Commons.

For days and days after the incident she ate very little and asked God to forgive her. She was haunted by the way Vernelle’s cheek had felt, by what it was like to invade and actually touch the flesh of another person. And when she thought too hard, she imagined that she was slicing through the woman’s cheek, the way she had sliced through the young man’s hand. But as time went on she began to remember the man’s curses and the purplish color of Vernelle’s fingernails, and all remorse would momentarily take flight. Finally, one morning nearly two weeks after she slapped the woman, she woke with a phrase she had not used or heard since her children were small: You whatn’t raised that way.

It was the next morning that the thin young man in the suit knocked and asked through the door chains if he could speak with her. She thought that he was a Social Security man come to tear up her card and papers and tell her that they would send her no more checks. Even when he pulled out an identification card showing that he was a Howard University student, she did not believe.

In the end, she told him she didn’t want to buy anything, not magazines, not candy, not anything.

“No, no,” he said. “I just want to talk to you for a bit. About your life and everything. It’s for a project for my folklore course. I’m talking to everyone in the building who’ll let me. Please … I won’t be a bother. Just a little bit of your time.”

“I don’t have anything worth talkin’ about,” she said. “And I don’t keep well these days.”

“Oh, ma’am, I’m sorry. But we all got something to say. I promise I won’t be a bother.”

After fifteen minutes of his pleas, she opened the door to him because of his suit and his tie and his tie clip with a bird in flight, and because his long, dark brown fingers reminded her of delicate twigs. But had he turned out to be death with a gun or a knife or fingers to crush her neck, she would not have been surprised. “My name’s George. George Carter. Like the president.” He had the kind of voice that old people in her young days would have called womanish. “But I was born right here in D.C. Born, bred, and buttered, my mother used to say.”

He stayed the rest of the day and she fixed him dinner. It scared her to be able to talk so freely with him, and at first she thought that at long last, as she had always feared, senility had taken hold of her. A few hours after he left, she looked his name up in the telephone book, and when a man who sounded like him answered, she hung up immediately. And the next day she did the same thing. He came back at least twice a week for many weeks and would set his cassette recorder on her coffee table. “He’s takin’ down my whole life,” she told Wilamena, almost the way a woman might speak in awe of a new boyfriend.

One day he played back for the first time some of what she told the recorder:

… My father would be sitting there readin’ the paper. He’d say whenever they put in a new president, “Look like he got the chair for four years.” And it got so that’s what I saw—this poor man sitting in that chair for four long years while the rest of the world went on about its business. I don’t know if I thought he ever did anything, the president. I just knew that he had to sit in that chair for four years. Maybe I thought that by his sitting in that chair and doin’ nothin’ else for four years he made the country what it was and that without him sitting there the country wouldn’t be what it was. Maybe thas what I got from listenin’ to father readin’ and to my mother askin’ him questions ’bout what he was readin’. They was like that, you see …

George stopped the tape and was about to put the other side in when she touched his hand.

“No more, George,” she said. “I can’t listen to no more. Please … please, no more.” She had never in her whole life heard her own voice. Nothing had been so stunning in a long, long while, and for a few moments before she found herself, her world turned upside down. There, rising from a machine no bigger than her Bible, was a voice frighteningly familiar and yet unfamiliar, talking about a man whom she knew as well as her husbands and her sons, a man dead and buried sixty years. She reached across to George and he handed her the tape. She turned it over and over, as if the mystery of everything could be discerned if she turned it enough times. She began to cry, and with her other hand she lightly touched the buttons of the machine.

Between the time Marie slapped the woman in the Social Security office and the day she heard her voice for the first time, Calhoun Lambeth, Wilamena’s boyfriend, had been in and out of the hospital three times. Most evenings when Calhoun’s son stayed the night with him, Wilamena would come up to Marie’s and spend most of the evening sitting on the couch that was catty corner to the easy chair facing the big window. She said very little, which was unlike her, a woman with more friends than hairs on her head and who, at sixty-eight, loved a good party. The most attractive woman Marie knew would only curl her legs up under herself and sip whatever Marie put in her hand. She looked out at the city until she took herself to her apartment or went back down to Calhoun’s place. In the beginning, after he returned from the hospital the first time, there was the desire in Marie to remind her friend that she wasn’t married to Calhoun, that she should just get up and walk away, something Marie had seen her do with other men she had grown tired of.

Late one night, Wilamena called and asked her to come down to the man’s apartment, for the man’s son had had to work that night and she was there alone with him and she did not want to be alone with him. “Sit with me a spell,” Wilamena said. Marie did not protest, even though she had not said more than ten words to the man in all the time she knew him. She threw on her bathrobe, picked up her keys and serrated knife and went down to the second floor.

He was propped up on the bed, surprisingly alert, and spoke to Marie with an unforced friendliness. She had seen this in other dying people—a kindness and gentleness came over them that was often embarrassing for those around them. Wilamena sat on the side of the bed. Calhoun asked Marie to sit in a chair beside the bed and then he took her hand and held it for the rest of the night. He talked on throughout the night, not always understandable. Wilamena, exhausted, eventually lay across the foot of the bed. Almost everything the man had to say was about a time when he was young and was married for a year or so to a woman in Nicodemus, Kansas, a town where there were only black people. Whether the woman had died or whether he had left her, Marie could not make out. She only knew that the woman and Nicodemus seemed to have marked him for life.

“You should go to Nicodemus,” he said at one point, as if the town was only around the corner. “I stumbled into the place by accident. But you should go on purpose. There ain’t much to see, but you should go there and spend some time there.”

Toward four o’clock that morning, he stopped talking and moments later he went home to his God. Marie continued holding the dead man’s hand and she said the Lord’s Prayer over and over until it no longer made sense to her. She did not wake Wilamena. Eventually the sun came through the man’s Venetian blinds, and she heard the croaking of the pigeons congregating on the window ledge. When she finally placed his hand on his chest, the dead man expelled a burst of air that sounded to Marie like a sigh. It occurred to her that she, a complete stranger, was the last thing he had known in the world and that now that he was no longer in the world. All she knew of him was that Nicodemus place and a lovesick woman asleep at the foot of his bed. She thought that she was hungry and thirsty, but the more she looked at the dead man and the sleeping woman, the more she realized that what she felt was a sense of loss.

Want to keep reading? Subscribers can unlock the whole story today. Otherwise, tune in next Monday for the conclusion, and meanwhile, check out Edward P. Jones’s unlocked Art of Fiction interview.

The Spirit Writing of Lucille Clifton

LUCILLE CLIFTON. PHOTO: RACHEL ELIZA GRIFFITHS.

It all began one night in 1976, when the poet Lucille Clifton was lightheartedly using a Ouija board with two of her daughters. The board began to spell out the name of Clifton’s mother, Thelma. At first, Clifton was incredulous, but as she received more messages, she came to believe that they were truly from her mother’s spirit. Later, Clifton wrote that “There was no point, no single statement that said unequivocally ‘this is she.’ It was/is the accumulation of things, the pattern of her self. Which is how we know anyone.” According to Clifton’s first-born daughter Sidney, over the years Clifton “evolved from the Ouija board” to automatic writing to, eventually, a spiritual state in which she could directly access the spirits without the need for writing. In the seventies and eighties, the Clifton’s Baltimore home became a spiritual way station through which a wide assortment of spirits apparently passed.

Despite her fame as a poet, Clifton’s trajectory as a self-described “two-headed woman” is a little-known part of her legacy. “Two-headed woman” is a traditional African American term used to describe women gifted with access to the spirit world as well as to the material world. Clifton’s unpublished spirit writing is housed at the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library at Emory University. These materials range from past life regressions to treatises on Black astrology to pages of unbroken cursive detailing the histories of Atlantis and Egypt. In many of Clifton’s documents, Blackness and the Black body are decentered by the concept of reincarnation. When she asks her spirit interlocutors about her previous incarnations, she is surprised to learn that in many of them, she was not a woman at all. Clifton’s spirit writing, while ostensibly fitting into a race- and gender-blind New Age tradition, should be read as an important contribution to Black feminist theories of embodiment. Clifton’s spirit communications foreshadow contemporary global issues like climate change and the rise of the far right, and they position Black women at the vanguard of addressing these issues.

In August and September of 1978, for example, Clifton received a series of dire warnings about the fate of the human world from a mysterious group of spirits she called “the Ones.” The Ones did not assume the personality of a departed human, and they did not weigh in on day-to-day affairs. They spoke of things of cosmic importance: the deep past of human civilization (for instance, the origins of Atlantis and demystifications of ancient Egyptian civilization) and its tenuous future. They returned “to remind human beings that they are more than flesh,” and in 1978 they warned Clifton:

If the world continues on its way without the possibility of God which is the same as saying without Light Love Truth then what does this mean? It means that perhaps a thousand years of mans life on this planet will be without Light Love Truth It is what we were saying indeed that there will be on Earth that place which human beings describe to the world of the spirits Hell Now there is yet time but not very much your generation Lucille is the beginning of the possibility and your girls generation is the middle etc.

The Ones, characterized by their mythic tone and liberal use of a royal we, peppered their messages with a line they repeated like a refrain: “There are so many confusions so many potential dangers in the world of the Americas.” It was a strange way of phrasing it, given that the fate of the entire world, not just the Americas, seemed to be in the balance. These spirits seemed to espouse a kind of post-racial universalism, yet they located “the Americas,” and their increasing globalization, as a place of unique evil. The spirits tell Clifton, “America is not a country where things sounding right are taken as right,” and say that this resistance to the truth is destroying the world. According to the Ones, the generation born at the end of the twentieth century would be the last to have the possibility to avoid an earth turned to Hell, making now the time to act on their message.

In the loneliness of the two-headed woman, the burden of saving the world falls disproportionately on Black women. In popular culture, the figure of the Black woman medium fulfills a deep social need for white people to see Black people as channels to a past they otherwise pretend to ignore. In the 1990 film Ghost, the psychic character played by Whoopi Goldberg asks, in dismay, when the ghost of Patrick Swayze’s character first speaks to her, “Are you white?” She already knows her body will be used as a surrogate for white people to connect with the afterlife they otherwise pretend not to believe in. In a society that consumes yet ridicules the supernatural abilities of Black women, Clifton sidesteps these narratives by emphasizing her own Blackness as a gift both linked to and on par with her supernatural abilities. Despite the heaviness of her role as a medium, Clifton regards it as a privilege of her present incarnation as a Black woman. An untitled poem in Clifton’s 1980 poetry collection Two-Headed Woman reads:

the once and future dead

who learn they will be white men

weep for their history. we call it

rain.

To be born a white man, despite its material benefits, is here represented as a kind of cosmic misfortune, a sullying of the soul with all the dirty deeds of white men’s history. If a soul’s incarnation as a white man is cause for weeping, then it follows that a soul’s incarnation as “both nonwhite and woman” should be cause for something akin to celebration.

Two-Headed Woman is her first published work to narrate her spirit communication. It begins, however, not with the story of Clifton’s spirit visitations, but with a series of oft-quoted homages to various aspects of her body: “homage to my hair,” “homage to my hips,” and “what the mirror said.” The latter poem ends with the exhortation:

listen,

woman,

you not a noplace

anonymous

girl;

mister with his hands on you

he got his hands on

some

damn

body!

This poem both reveals the interchangeability of the Black woman’s body and challenges it. The anonymity of “somebody” is interrupted by the emphatic imposition of an admonitory “damn.” Clifton’s emphasis on her body in a poetry collection that describes the demands of the spirits is not accidental. Clifton asserts the preciousness and integrity of her body in the draining work of spirit communication. In an untitled poem in her 2004 collection Mercy, Clifton describes the Ones chiding her with, “your tongue / is useful / not unique.” Her embodied poetry is itself a rejoinder to the spirits’ insistence that she is “not unique.” Just as Frantz Fanon famously ends his philosophical meditation in Black Skin, White Masks with an appeal to his body—“O my body, make of me always a man who questions”—Clifton similarly enshrines the importance of the body in questions of the spirit. When read together, Clifton’s poetry and her spirit writing represent a both/and reality, one in which race is merely earthly, profane, and temporary, and yet the racialized body matters in this realm.

Clifton’s spirit interlocutors view race in interesting ways, neither disavowing its existence nor inflating its importance in the afterlife. They are post-body but not post-racial. In 1977, Clifton put out an open call to the spirit world for celebrity spirits who would like to take part in an anthology of sorts, which she titled “Lives/Visits/Illuminations.” By asking the spirits questions like “What was the experience of death like for you?” and “Would you like to clarify anything about your life for our world?”, Clifton hoped to bring them peace and closure through a discussion of the lessons they had learned since their deaths, and sought to serve spirits and humankind by allowing them to share their experiences in their own words. The resulting replies were a strange, rollicking, and deeply moving compilation of voices, often speaking against racism and the human tendency to hierarchize physical differences. Of the twenty spirits who volunteered, many of them would today be recognizable as important historical figures, but Sidney Clifton emphasizes that the lessons of the afterlife made their messages more important than their worldly identities and accomplishments. The spirits seem to have learned a gentle disregard for human markers of difference. For instance, when Clifton interviews one spirit, who was a religious leader in his life, and asks what he looked like, he replies somewhat dismissively, “Shall we deal in statistics?” But he concedes that he had brown hair, brown eyes, and was of medium height. A spirit who lived in eighteenth-century Germany, when asked whether it was true that he was of African descent, replies, “Yes. Yes, Grandfather, yes. Of course in the old days in my country we would never admit it. Silly.” Another spirit insists that she does not want to be reincarnated, “Not for awhile, till things get better. I want to come back when I can go anywhere and be a Negro and nobody notices.” Spirits who had been secretly queer in their previous incarnations returned to say that they “didn’t hurt a soul and didn’t corrupt no children” and to warn the living that in their time to be queer was to be “like a [sic] animal, a dog, worse than a dog – DON’T BE LIKE THAT PEOPLE. Don’t make somebody miserable.” All of these answers strip back class, race, gender, and sexuality, revealing them as the changing weather of a soul’s journey, not the journey itself. Certainly, these were not the most valued aspects of the spirits’ incarnations on earth. When asked what things still attract them to our world, the spirits’ answers are simple: trees, autumn, “sparkly places,” children, happy families, laughter, singing, running around.

In her writing, Clifton adopts an ethereal stance in which “the soul survives bodily death, has survived numerous bodily deaths, will survive more. There is some One in each of us greater than the personality we manifest in any life. The soul does not merely select her own society, the soul is her own society. And love is eternal, is God. Is.” And yet, while impermanent, she does not view the Black woman’s body as a halfway house on the way to more fortuitous incarnations. Like the soul, the body is its own society with its own values, lessons, and codes. Although the spirits admonish Clifton for her fixation on earthly matters of race and gender—“you wish to speak of / black and white […] have we not talked of human”—she maintains a delicate balance between the idea of a raceless soul and her incarnation as a Black woman. In her view, it is no accident that her body and its specificities became a channel for the spirits. In her writing, being a Black woman is a way of listening, a radical form of receptiveness to the lessons that history teaches. And as her daughter Sidney puts it, “I think her actual gift was her openness and ability to hear.”

Clifton’s theory of spirit does not succumb to fatalism. When one considers the trials Clifton’s mother Thelma faced —poverty, epilepsy, a philandering husband, death at forty-four years old—there is some comfort in this expansive view of the soul. Thelma’s spectral return represents a Black woman’s soul unbound by the structural misfortunes of her life. She bears witness to these trials but is not erased by them. Lucille Clifton’s spirit writing makes the pangs of my own embodiment as a Black woman easier to bear amid constant reminders of the perils of Black embodiment. There is solace in the idea that this brown skin and these wide hips were made for listening to the voices that could not be erased by time, history, or death. Oh my body, make of me always a woman who listens.

Read Lucille Clifton’s poetry in our archives.

Marina Magloire is an assistant professor of English at University of Miami and a Public Voices fellow with the Op-Ed Project. She is currently writing a spiritual history of Black feminism and Afro-diasporic religion. Sidney Clifton, whose help was invaluable in writing this essay, is an Emmy-nominated producer and the president of the Clifton House, an artists’ and writers’ workshop project designed to honor the legacy of Lucille and Fred Clifton. Inquiries about the Clifton House can be directed to cliftonhousebaltimore@gmail.com

William Gaddis’s Disorderly Inferno

William Gaddis. Photo: Jerry Bauer. Courtesy of New York Review Books.

Sixteen years like living with a God damned invalid sixteen years every time you come in sitting there waiting just like you left him wave his stick at you, plump up his pillow cut a paragraph add a sentence hold his God damned hand little warm milk add a comma slip out for some air pack of cigarettes come back in right where you left him, eyes follow you around the room wave his God damned stick figure out what the hell he wants, plump the God damned pillow change bandage read aloud move a clause around wipe his chin new paragraph God damned eyes follow you out stay a week, stay a month whole God damned year think about something else, God damned friends asking how he’s coming along all expect him out any day don’t want bad news no news rather hear lies, big smile out any day now, walk down the street God damned sunshine begin to think maybe you’ll meet him maybe cleared things up got out by himself come back open the God damned door right there where you left him …

—William Gaddis on writing a novel

A magnificent example of rant. A perfect example really. The Recognitions, William Gaddis’s first novel, was seven years in construction. J R, his second, took more than twice that long. In each case the invalid miraculously arose and, with commanding vigor, transformed and transforming, entered the realm of great literature.

Back in 1957, Malcolm Lowry kept trying to deliver his enthusiasm for The R through a mutual friend, David Markson. “It is a truly fabulous creation, a superbyzantine gazebo and secret missile of the soul.” Mr. Gaddis did not respond. He had not read Under the Volcano (“It was both too close and too far away from what I was doing … ”). On the other hand, he wrote a letter to J. Robert Oppenheimer and even sent him a copy of The R and never received a reply.

The R sank like a stone in the sea upon publication. The scholar and excellent biographer Joseph Tabbi notes dryly that critics were “unprepared” for it. Some of the reviews are parodied (though not by much) in J R:

… so ostentatiously aimed at writing a masterpiece that, in a less ambitious work, one would be happy to call promising, for such readers as he may be fortunate enough to have …

… nowhere in this whole disgusting book is there a trace of kindness or sincerity or simple decency …

… a complete lack of discipline …

But Mr. Gaddis wasn’t keen on even the occasional good reaction. He disliked the Stuart Gilbert quote the publishers put on the back cover comparing him to Eliot and Joyce:

… long though it is, even longer than Ulysses, the interest, like that of Joyce’s masterpiece and for very similar reasons, is brilliantly maintained throughout …

He felt this gave reviewers an “escape hatch” and protested that “my Joyce is limited to Dubliners and a few letters.” He maintained throughout his life that he had never read Ulysses. He merely seemed to have read everything else. And as Ezra Pound said when an acquaintance showed him her copy of The R: “You should tell your friend [Gaddis] that Joyce was an ending, not a beginning.” The R with its thickets of allusions and transcendental questing was all ravishing encyclopedic ambition. It was new. J R was even newer. It employs none of the fictive habits, the prompts and crutches and connective tissue of narrative. Time slips around like an eel. Place is bulldozed. Characters have no identity save for the words they speak and they speak the speakable with tireless abandon. There is no communion, no closure. There are rants. Mad soliloquies. Offended ripostes, offensive parries. Almost everyone accounted for is indignant, baffled, enraged, duplicitous, misunderstood, or misunderstanding. There are dozens of players and voices—composers, writers, teachers, lawyers, politicians, financiers, deadbeats, and frauds. And it never lets up. Even the end is poised to start all over again. It is a riotous dizzying discomfiting success beholden to nothing that came before save for its elusive, more elegant daddy, The R, which was beholden to no one.

In 1956, nineteen years before the publication of this second novel, Mr. Gaddis wrote a registered letter to himself to protect his idea for it from copyright infringement:

In very brief it is this; a young boy, ten or eleven or so years of age ‘goes into business’ and makes a business fortune by developing and following through the basically very simple procedures needed to assemble extensive financial interests, to build a ‘big business’ in a system of comparative free enterprise employing the numerous (again basically simply encouragements (as tax benefits &c) which are so prominent in the business world of America today …

This boy (named here ‘J.R’) employs as a ‘front man’ to handle matters, the press &c, a young man innocent in matters of money and business whose name (which I got in a dream) is Bast. Other characters include Bast’s two aunts, the heads of companies which JR takes over, his board of directors, figures in a syndicate which fights his company for control in a stockholder’s battle, charity heads to whom his company gives money, &c.

This book is projected as essentially a satire on business and money matters as they occur and are handled here in America today; and on the people who handle them; it is also a morality study of a straightforward boy reared in our culture, of a young man with an artist’s conscience, and of the figures who surround them in such a competitive and material economy as ours. The book just now is provisionally entitled ‘SENSATION’ and ‘J.R.’

What a surprisingly unpromising précis! This letter to self gives not the slightest hint of the manner in which the earnest Bast, who just wants to compose music, the less than winsome J R, and “the figures who surround them” will be presented, which is in 770 pages of unattributed, intercepted, interrupted dialogue, in “speech scraps, confetti like wiggles of brightly colored cliché” (William Gass, admiringly), the occasional lyrically peculiar description:

For time unbroken by looks to the clock the only sound was the chafing of an emery board, and the clock itself, as though seizing the advantage, seemed to accomplish its round with surreptitious leaps forward, knocking whole wedges at once from what remained of the hour.

snatches of advertisements, radiospeak, and news fragments:

——selection from Bruckner’s eighth symphony brought to you by …

——like sending your mouth on a vacation …

——homes in America, many were trees …

and even the class paper J R wrote in cursive on Alaska:

Alsaka … There is about a hundred billion barrells of oil in Alsaka waiting these millions of years locked in the earth for the hand of man to release it in the cause of human betterment …

But mostly there is dialogue. Dinner is served in dialogue. Here is the unhappy diCephalis family. Dan diCephalis is a psychometrician at J R’s school; Ann, his deeply frustrated wife. They are both so miserable and distracted in their marriage that they harbor a flatulent drifter in their home, both thinking he is the other’s father. The children are Nora and Donny:

— … Nora I said get Donny for supper … Here, sit Donny here and you …

—But Mama Donny has to sit where the plug is so he …

—All right, my God it’s probably too late for a psychiatrist anyhow, we should take him to the electrician … stop talking and eat …

—What is it.

—What do you mean what is it, it’s your supper. What does it look like.

—It looks like lingam.

—Like what?

—Like a lingam.

—Like a lingam! How do you know what a lingam looks like.

—Because it looks just like this.

—Maybe she, maybe she saw that book you had …

Death, too, happens (of course) but is delivered at a remove:

—Jack look you’re spilling that all over the …

—I’m not spilling, it’s spilling. I’m not …

—Damn it just let me pour it will you!

—But about Mister Schramm is he, he’s all right isn’t he? I mean, where is he …

—Down the hall there look, he had an accident Bast he …

—I know it yes I was, you mean another one?

—Yes he, wait listen don’t go in there now!

or in the case of the unfortunate Mr. Glancy:

—Yes no go ahead Vern come in Mister ahm Major that was Gottlieb down to the Cadillac agency, he thinks he can put the financing on the car right into your name without repossessing it from Glancy’s estate to handle it like ahm, like a used car sale that is to …

—What was that about a smell.

—No well of course it was used since Glancy did use it to ahm, I think the Cadillac people prefer to say previously owned yes and he’d only driven it seven miles but of course he’d been in it for a week when they found him down in the woods there and apparently they’ve been unable to remove the, to restore the smell of a new car interior that is to …

We are … swept along. Mr. Gaddis confessed that he wanted us to be, in this flow of unremitting talk—“might miss a lot but that’s what life is, after all? missing something that’s right before you?” His characters can’t or won’t communicate in any meaningful way. “Can’t drive and I won’t ride,” pronounces Jack Gibbs, the stalled writer who is forever sifting through his boxes and boxes of paper, his research, his notes, his material, for his all-consuming impossible to complete definitive Spenglerian “work.” Gibbs is a churlish mess, it is the composer Bast, “a young man with an artist’s conscience,” who possesses a bit of pummeled purity. He so wants to create magnificent oratorios but the closest he comes to a commission is writing “zebra music” for the stockbroker/big game hunter Crawley who wants to make a film about African wildlife in the hopes that the government will import game—prey and beasts of prey—for use in National Parks.

— … wake up some people down in Washington to the idea of stocking our public lands with something more suitable than a lot of trailers and beer cans.

The reader enters J R not as through a dark wood but by way of the churning flush of the Big Commode—American capitalism. J R himself, a bright and slovenly boy, is all canny greedy play, affecting everyone, the good, the bad, and those simply not paying attention. He grasps the capitalistic model perfectly (Mr. Gaddis said he was fascinated by the concept of big business as a fairly childish affair), doing what he does “because that’s what you do!” Here he is in a phone conversation with the “general counsel,” a Nonny Piscator, he has acquired for his J R Corp Family of Companies:

— … see if it’s got any of these minerals in it we should get to take this here percentage depletion allowance the whole … I mean if we can get some tax benefit off depleting something why shouldn’t we … Okay so with these here futures I’m not telling you to do something illegal … I mean what do you think I got you for! I mean if I want to do something illegal what do I want with a lawyer I mean holy shit where do you think we are over at Russia? where they don’t let you do anything? These laws are these laws why should we want to do something illegal if some law lets us do it anyway …

Mr. Gaddis’s manner of composing his novels was amassment and rearrangement. He collected all matter of stuff, paper stuff, heard stuff. “Though I weep for order I still live in a world of scrawled notes on the backs of envelopes,” he admitted. Many of the scraps, fragments, musings, quotes made their way from book to book. A line from Thomas Wolfe’s Look Homeward, Angel that he fancied—“the unswerving punctuality of chance”—appeared in all four novels as well as the novella Agapē Agape. He preserved an enormous amount of source matter, “barells and barells” stored in food and liquor boxes and now archived in the Special Collections at Washington University in St. Louis.

——homes in America, many were trees …

There was so much! There could be no end to it, to its possible significance or soulful worth (or lack of it). He well knew the entropy that chaos brings. He believed that America itself was a “grand fiction” exacting not only taxes from its people but more critically a continuing faith, or at least the suspension of disbelief, in its own existence. In a 1973 letter to the theologian Thomas Altizer, he wrote:

… it is this question what is worth doing? that has dogged me all my life, both in terms of my own life and work where I am trying now again in another book to fight off its destructive element and paralyzing effects; and in terms of America which has been in such desperate haste to succeed in finding all the wrong answers. In this present book satire comic or what have you on money and business I get the feeling sometimes I’m writing a secular version of its predecessor …

During all the years he worked on J R, he was dutifully laboring for a paycheck from the corporate machine—Kodak, Ford, IBM, Pfizer (“an operation of international piracy”)—writing ad copy and position papers, managing to stay employed though his efforts were sometimes found wanting. An executive chided one of his industry film scripts as “a little too profound and needed reshaping in a manner that would be informative at a shallower depth.” He knew the cant of marketing well and was ever alert to systems of speech, of persuasion, of obfuscation, seeing and portraying the American way of waste—the waste of nature, talent, energy, the waste that markets, systems, management demand for growth.

A great deal has been written about the works and intentions of Mr. Gaddis, much of it alarmingly erudite yet still interesting in its sort of meanly excluding way. Many are the ways he is perceived and read. Shortly before The R was published, Jack Kerouac met him in a bar and described him as “ironic looking, sporting a parking ticket in his coat lapel.” I picture him at the age of five when he was sent off to a “strict” boarding school, already Mr. Gaddis in my imagination, though small. Intelligent, neatly attired, comporting himself with all the seriousness a suppressed hilarity allowed.

In 1976, J R won the National Book Award—chance arriving with unswerving punctuality. As judges, Mary McCarthy and William Gass were instrumental in awarding it. The other judge, whoever and whatever his opinion, was deeply, deftly ignored. McCarthy found the novel “horrid and funny” and referred to it as Junior. The award provided a respectable amount of fame and increased readership, though not as much as might be expected for J R is not for the faint of heart and mind or the weak of concentration. J R is a rude demanding complex riotous uncomfortably edifying novel, a howling maelstrom of voices, a grabby talky disorderly inferno of the spirit. It is also remarkably knowing about the American character.

Somewhat early on (page 204!), a young boy appears for the first and only time. This is Francis. He has many questions and a few cautious opinions.

—You know what I used to think Mama? if I didn’t talk now, if I kind of saved it up and didn’t talk, that then I’d be able to talk after I’m dead.

How intriguing! But if true we would be unable to experience the figures of J R there (as we have so thoroughly, appallingly, enjoyably experienced them here) for how would we recognize them?

Joy Williams is the author of four novels, five story collections, and the book of essays Ill Nature. She’s been nominated for the National Book Award, the Pulitzer Prize, and the National Book Critics Circle Award. She lives in Tucson, Arizona, and Laramie, Wyoming.

From J R, by William Gaddis, published by New York Review Books this week. Introduction copyright © 2020 by Joy Williams. William Gaddis’s first novel, The Recognitions, will be published by New York Review Books next month.

October 16, 2020

Staff Picks: Trail Mix, Safe Sex, and Conversation

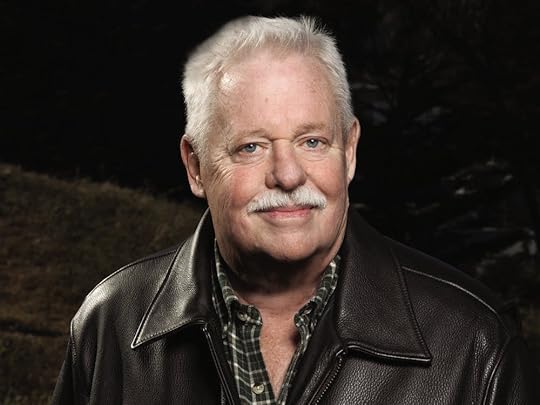

Armistead Maupin. Photo: Christopher Turner. Courtesy of Harper Perennial.

Why did I sleep on the Tales of the City television reboot? Maybe my 2019 self knew that her October 2020 counterpart would desperately need to hear one of her favorite fictional characters, Anna Madrigal (played by the incomparably sympathetic Olympia Dukakis), declare to a doom-mongering millennial documentarian: “We’re still people, aren’t we. Flawed. Narcissistic. Doing our best.” I write now to recommend the show, but with the caveat that you must read all of the books first (start here), and it’s not a bad idea to watch the previous television adaptations, either. Go ahead, immerse yourself in the five-decade epic of Mrs. Madrigal, a San Francisco landlord who resembles a fairy godmother (imagine!), and the eclectic tenants of her hilltop home as they navigate friendship, romance, and gender identity. Armistead Maupin’s Tales series found me when I was about twenty-four, and it gave me both an escape from my own situation and an education about the wider world. Like Dickens, Maupin writes for the masses, and he originally published the first five books of the Tales in serial. He gives characters names like Anna Madrigal, DeDe Halcyon, and Mary Ann Singleton; Michael Tolliver, the boy looking for love at the center of it all, is surely an outright nod. And like Dickens, Maupin is both an operatic storyteller and a documentarian of contemporary social issues, though he doesn’t judge or preach. The Tales were where I first met and loved transgender characters and where I learned about AIDS as it was experienced personally and over decades by gay men, rather than as a distant reason for high schoolers to practice safe sex. The books were, sad to say, revelatory for me even in the early aughts—but when they were first published, in the seventies and eighties, they were revolutionary. Beyond the candid treatment of then-taboo subjects, each book interweaves juicy personal stories and a dark secret that the gang works together to uncover—a stand-in for the real danger in their lives and a nudge that living honestly is the best policy. But these are cozy mysteries: whether you’ve recently broken up with your person or you’ve just found out they’re a psychopath, you can always go home to Barbary Lane, where Mrs. Madrigal will roll you a joint and affirm your human value. Now that things are feeling scarier than ever, what a godsend it is to revisit Maupin’s clear-eyed yet somehow still hopeful world. —Jane Breakell

The A24 Podcast returned this week with a conversation between the composer Nicholas Britell and the actor Nicholas Braun, both of Succession fame—a show that supposedly shouldn’t fill one with nostalgia for their childhood but, for me, somehow does. But even if I weren’t waiting patiently for the third season of Succession, relishing my coworkers’ tales of Kieran Culkin sightings around Manhattan, I still would have clicked that podcast notification with the same eagerness. I treat most podcasts like trail mix—picking out the M&M’s, making time only for the titles that feature names I already know—but The A24 Podcast (and The Paris Review Podcast, I am obliged to add!) is not one of those. Each installment manages to surprise me—a commendable feat for any interview, let alone podcast. Even predictable pairings such as Jonah Hill and Michael Cera don’t go where I expect; their conversation includes Hill’s advice for living unselfishly, and anecdotes about Prince at parties. I am reminded each time I listen that what I seek, maybe, is the emphasis on caring for the craft, whatever it may be. Often, I feel the urge to return to the podcast’s first episode, “All the Way Home with Barry Jenkins & Greta Gerwig.” In California, I used to listen to it on the long weekday walks I took to feel like a New Yorker again in that strange desert town with its unwalkable sidewalks, its uncrossable roads. Recently, playing the episode for the first time while fixed in place—my kitchen, as I did my silly little tasks, made a meal, cleaned my mess—I was struck by what Gerwig says about times of stillness as times of growth. The year having gone the way it has, I nodded my head solemnly as she spoke, surprised at having found something new here since my previous revisitation in February. “These moments where what looks like being lazy or a fallow period or like you haven’t done anything, a lot of important work can get done there, when it doesn’t look like anything is happening on the surface,” she tells Jenkins. “By the time you were making Moonlight, you had stored up a lot.” And we’re probably not all stockpiling the stuff that would make us each a Moonlight, but there’s something here in the stillness nonetheless. —Langa Chinyoka

Marie NDiaye. Photo: © Catherine Hélie. Courtesy of Knopf Publishing Group.

I cannot think of a novelist who has been so consistently recommended to me with unfettered enthusiasm as Marie NDiaye. This week I began reading her with The Cheffe (translated from the French by Jordan Stump), the work of a masterful prose stylist calmly and elegantly assembling layers of psychological realism with the same precision and focus her titular character might use to prepare one of her famous dishes. The story of the Cheffe is told by way of an unnamed narrator’s lovesick memories, a clever and impressive construct that presents a portrait of a woman who is both mystic and artist. The narrator’s reverent tone lends the novel a hagiographical quality as it examines artistic obsession and devotion with a grace that, to me, inspires enthusiastic recommendation. —Lauren Kane

At only fifteen minutes in length, the 2018 short film Blood Orange brews up a bizarre and cruel ambience with the lightest of touches, creating a viewing experience that is equal parts concerning and charming. Despite the ableism, murder of pets, and other violent ends, this little Australian film feels somber only when removed from the context of the delightful narration that bookends the story. The whimsical piano tune and the Wes Anderson–esque voice-over gave me space to enjoy the film’s craft rather than wallow in its darkness, thereby creating a fiendishly pleasant dark humor that I wish we saw more of in film. —Carlos Zayas-Pons

I picked up the poet Choi Seungja’s Phone Bells Keep Ringing for Me, translated by Won-Chung Kim and Cathy Park Hong, because she was an influence on Kim Hyesoon, whose collection Autobiography of Death (translated by Don Mee Choi) I haven’t been able to stop thinking about since I read it in 2019. Choi first started publishing in 1979 and has since then become, as Hong explains in her preface to the book, “one of the most influential feminist poets in South Korea.” The work included in this collection is stark in its examination of the power differentials between men and women. Loneliness, the politics of the twentieth century, and the body all appear as topics in poems such as “Toward You” (“I will come to you. / Like syphilis germs flowing through veins, / like death gripping life”) and “The End of a Century” (“The 1970s were a horror / and the 1980s a humiliation. / Now, what stigma will the end of this century stick with me?”). I’m in awe of how bracing these poems can be, how critical and clear-eyed Choi is about the destructive elements of consumerism, patriarchy, and heterosexual love. —Rhian Sasseen

Choi Seungja. Photo: Sinyong Kim. Courtesy of Action Books.

The post Staff Picks: Trail Mix, Safe Sex, and Conversation appeared first on The Paris Review.

October 15, 2020

The View Where I Write

Read John Lee Clark’s poem “Line of Descent” in our Fall issue.

Vladimir Nabokov wrote standing up, scribbling on index cards while snacking on molasses. Lucille Clifton said that she wrote such short poems because that’s how long she could hustle during her children’s naps. Truman Capote famously described himself as a “completely horizontal author,” writing longhand in bed or on a couch, with cigarettes and coffee handy. Maya Angelou often rented a room at a nearby hotel, by the month, and had the staff take out the paintings and any bric-a-brac. Charles Dickens liked changing venues but required that his traveling desk and the same ornaments be arranged just so. Agatha Christie puzzled out her murder stories in the bathtub while munching on apples. Victor Hugo abolished distractions by locking himself in a room without any clothes, for fear they would tempt him to go out. What he did permit himself was what many writers have: a view.

I am no different. Where I write, on the twenty-fifth floor of an apartment building in downtown Saint Paul, I possess a most breathtaking view. Directly below me is a thick circular grove of—what shall I say?—soft-branched willow trees. A short distance due west lies a pond in the shape of a bear claw. I can see the reeds at its bottom and the cattails dancing around it. Due east across a field of tall grass, warm sunlight bathes over a series of clumps—perhaps houses?—and a long knoll crammed with fuzzy flowers.

I never tire of tracking the snaking strip of beach that frames my vista. To the far west is a cape, the northeast a bay, and farther east swells out a peninsula. Strangely, there are no boats. Neither are there any cars. Not as far as I am able to observe, at any rate.

My sighted friends tell me that the panorama outside my home office windows is wonderful. I smile politely. Once they’ve left I hurry to my desk, which faces a wall, to write and delight in the real landscape—the rug under my desk. As my fingers begin pounding away at the keys or surfing the dots of my Braille display, my feet go a-roving. The rug is unlike any other. A dear friend, the artist and philosopher Erin Manning, made it using different patterns, shapes, and fibers. She employed varying thicknesses and lengths, ranging from tall tufts to the untufted woven base of the rug.

A topological marvel, the rug’s outline is map-like and the intentional hole is a revelation. My right heel often nestles in the circular grove, while any number of my left toes may be taking a dip in the hole. The rug is the beginning of a new world. We in the Protactile movement have been laying foundations dealing with the most basic human requirements—language, co-presence, space, navigation, and even art—but little did I know how much decoration could offer.

So much out there in the world, and here in my home, is tactilely monotonous. Floors, walls, surfaces—all tyrannies of uniform texture. It turns out that our mental health demands forests, mountains, valleys, flowers, animals, waterfalls, and crashing waves! Be it a rug that’s also a work of art or cheapo, freebie swag, we need to populate our environments. We need a mess, a storm, a cacophony.

I regret to say that I am, deep down, a selfish man. I won’t share my view! But even deeper down burns my love for our future. Thankfully, Erin made two rugs for me. The other, bigger, even more specular view hangs on a wall, to receive our hands or shoulders or cheeks or noses or lips as we pass by or, frequently, stop. It is easy to take down should friends desire to have our feet discover its wonders while we converse, or to drape it over our laps for us to gaze upon it together, whispering and exclaiming, with our hands.

Read John Lee Clark’s poetry in our archives

John Lee Clark is a National Magazine Award–winning writer based in Saint Paul, Minnesota. A member of the inaugural class of Disability Futures Fellows, he is at work on his debut collection of poems and second collection of essays.

The post The View Where I Write appeared first on The Paris Review.

Escaping Loneliness: An Interview with Adrian Tomine

Adrian Tomine. Photo: Susan De Vries.

Adrian Tomine and I were both English majors at UC Berkeley in the nineties. We undoubtedly roamed the corridors of the English department in Wheeler Hall at the same time, along with the future actor and fellow English major John Cho. We were all dreaming of telling stories or being in stories, and I wish there were some alternate past in which we all hung out and encouraged one another and said, Go for it, dude!

I would have been a fan of Tomine’s work back then, given how much of a fan I’ve been of his work since his early Optic Nerve comics. I have all of his books, which is more than I can say for almost any other writer. He’s a natural storyteller who brings together a clean line in his drawing to fit the spare lines of his stories. He’s also a master of the short form, from anecdote to short story and short novel. As someone who has suffered through writing a collection of short stories, I can testify that simply because a form is short does not mean it is easy. If anything, short forms are harder because the storyteller has to be concise and must know what to leave out as much as what to leave in.

Tomine knows what to leave out. The absences in his work, from what is not drawn and what is not said, make the presences stand out even more vividly. One thing absent from much of his earlier work was his status as an Asian American, which he begins to gesture at in his midcareer efforts, such as the story “Hawaiian Getaway” and the hilarious Shortcomings. What is refreshing about his approach to Asian Americans is his lack of sanctimony. Instead, he treats Asian Americans with his trademark astringency and satire. I’m all for it. I love my fellow Asian Americans, but our necessary convictions and beliefs can easily turn into pompousness and a painful lack of self-awareness. As someone who is both inside and outside of Asian America, Tomine sees through and draws from these blind spots, mixing sympathy with skepticism in just the right dose.

Now, in The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist , Tomine returns with the storytelling style his fans have come to expect, but here he foregrounds his own Asian American life. Not that being Asian American exhausts the meanings of his life or his art—far from it—but it is one meaning, and he extracts a lot of humor from it, the way a dentist extracts a tooth. There’s some numbness and pain involved, but if there’s blood, you, the patient, and now the reader, don’t see it. This is the terrain of microaggression, sublimated response, and understated ambition that Tomine explores with the precise touch of a dentist gazing perpetually into a mouth, doing the crucial work of the quotidian. It’s lonely work, indeed, but by dwelling for so long and so thoroughly in the loneliness of his art, Tomine brings us close, terribly close, to the halitosis of being human, to the emotions we might prefer to keep at a distance.

INTERVIEWER

What do you like to be called as an artist?

TOMINE

I’d probably say “cartoonist.” But if I’m meeting my wife’s extended family and they want to say, Oh, we heard you’re a graphic novelist, then I’d happily go along with it.

INTERVIEWER

In a review of your previous book, Killing and Dying, Chris Ware said you write comics for adults. There’s still a lot of misunderstanding about the work you engage in. Is that frustrating?

TOMINE

Compared with how frustrating it used to be, it feels like we’re living in a fantasy world. Even ten years ago it was so different. Now there’s a pretty good chance that if I meet someone and tell them I’m a cartoonist or a graphic novelist, they’ll be interested and polite, as opposed to being confounded or put off or, like, protecting their children. The most interaction I have with random people is through my kids’ school. And in Brooklyn, it’s almost a boring, conservative job, like, Oh, he’s a graphic novelist? Well my dad’s a full-time protestor—or something like that.

INTERVIEWER

There’s a funny episode in The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist where you’re the dad at your kids’ school getting asked to do show-and-tell about your work. And you do a poop sketch. But some brat tells the story to their parents, and then you’re humiliated by this email to all parents saying, “There was an incident today … ”

TOMINE

I probably made it sound much worse than it really was.

INTERVIEWER

Well, Loneliness is a very funny book. I think it’s probably your funniest work to date, as well as your most explicitly autobiographical. And yet in one interview, you mention how too much, perhaps, is made of artists and their relationship to their work, how sometimes it veers into self-promotion, and you have an ambivalent relationship with that. So why did you do Loneliness, which seems like a very autobiographical work?

TOMINE

When I say I think there’s maybe too much of an interest in figuring out the relation between artist and art, I’m speaking as a self-conscious artist who sometimes feels intruded upon. But as a reader, I’m just as guilty of that as anyone else. And for whatever reason, I personally respond to art where I feel the artist is telling me something about their specific life through a fictional story. I’ve been trying to do that, to some degree, with every comic of mine that’s ever been published. Especially in the corner of the medium that I exist in, there’s this long tradition of the confessional, autobiographical comic. It’s something I’ve always connected with and been a fan of but also been a little apprehensive about doing myself. After I finished Killing and Dying, I didn’t want to just immediately put out another book of that same exact kind of material. So I made a conscious choice to try to do something different in terms of art style, tone, and focus.

INTERVIEWER

It seems like cartoonists often draw and write about their anxieties as cartoonists—the difficulty of the work, the neglect they experience. Is difficulty a preoccupation for cartoonists?

TOMINE

I think there’s a little bit of a generational divide. It’s tapered off quite a bit. I think the cartoonists who are older than me tend to have a preoccupation with difficulty. They were deeply impacted by the underground comics movement that started in the sixties, and that’s where a lot of the focus on the artist’s own anxieties and whatnot blossomed. That type of work made such a profound impact on the medium for people of the right age—which is totally different from people younger than me who, in some cases, feel no connection to and are actually kind of disdainful of that material. I’m totally prepared for a reaction from younger readers of like, Stop whining, how hard can your life be, look at what you have, being a cartoonist is fun.

INTERVIEWER

Is writing and drawing together harder than just doing one or the other?

TOMINE

The easiest way for me to create art or to express myself, really, is through making comics. The times when I’ve given myself the challenge of isolating one element and just creating an image or just writing have always been more of a struggle. I think that has to do with how I learned to process the world. From a very early age, I was always thinking of the world in terms of comics.

INTERVIEWER

Early in Loneliness, you depict yourself as a little boy in a Fresno classroom, discussing your early artistic ambitions and your take on comics, and you’re focusing on superhero comics at this time. At what point did you shift from wanting to do superhero comics to doing what you do now?

TOMINE

I was about ten when I realized I had become a comic book collector and not a comic book fan. Out of a sense of ritual and obsessiveness, I would still go to the comic book store every week, and they would hand me the new comics I’d requested, and I would just blindly pay for them. And then I would go home and kind of joylessly flip through them out of obligation. I was fortunate enough to have access to a comic book store that also had a different section, one that I had never ventured into because I thought it wasn’t for me or it was scary. But nothing was stopping me. So I was able to just walk over there, and instantly, my life changed. I discovered Love and Rockets, which was the perfect gateway drug. I could sense that the Hernandez brothers grew up loving the same stuff that I did, and so I recognized some of their inspirations and influences. But I could also see that their work was much cooler, and much more “mature” than the superhero comics I’d been reading, and that really excited me. Love and Rockets led me to so many other great comics and artists I’d never heard of before. After that, I made a complete shift in my taste and started exclusively buying comics that were probably a little over my head, a little too adult. But I’m grateful that I had parents who trusted my judgment because those comics are completely responsible for where I am now.

INTERVIEWER

In other interviews, you’ve talked about how your writing and drawing have always taken place against a sense of your own inadequacy. In Loneliness, there’s a funny episode where you’re interviewed by Terry Gross. And the result is, in your opinion, disastrous. Your inner voice tells you to jump in front of a subway train. Obviously you didn’t do that, so is the unwillingness to give up and listen to that voice what makes you a successful artist?

TOMINE

I don’t think of myself as a very determined person in any other way. In general, I’m very happy to give up if something is too difficult. But I feel like there’s something about creativity, and just making comics in particular, that I keep coming back to. For a long time I was realistic enough to think that making comics would be a hobby throughout my life, that I would have to make money with a different job and do comics when I came home at night. And I felt okay with that because I’d spent my whole life that way—I’d go to school, and then as soon as I was freed from it, I would come home and start working on comics. I don’t know where it comes from, but I feel like that’s the only aspect of myself that is surprisingly determined and resilient.

INTERVIEWER

The title of your newest book also alludes to the loneliness of the long-distance runner. Is loneliness difficult for you, or is loneliness something that you’re comfortable with—or something that’s even desirable for an artist to be able to live with?

TOMINE

One of the many things I’ve learned as a result of the past four or five months is that loneliness was the thing I hated most until it was taken away from me. Within the first week of homeschooling, I realized that this was the first time since childhood that I didn’t have an extended period of time every day by myself, in a room, being creative. I used to think of comics mainly as a way to send a message in a bottle out into the world and maybe make friends or find a girlfriend—a way of escaping loneliness. And now, at least, answering you today, I feel like loneliness is really important to me, and it’s definitely a big component of creativity, but also mental health. I guess there’s a distinction between being alone and loneliness, but I actually do miss loneliness—that sort of longing was something that drove me creatively and also motivated me to evolve as a person.

INTERVIEWER

Near the end of the book, you write, “For most of my life I felt like anything other than working on comics was a distraction and that’s insane.” Is dedication to work a kind of insanity, or could we also say it’s a kind of spirituality? Spiritual people go off and isolate, they endure loneliness, they suffer and all kinds of things. To me there’s a spirituality in an artist’s relationship to their art. They’re willing to sacrifice and endure for whatever it is they find to be beautiful.

TOMINE

I would be happy if someone said that about me, but I think the truth is that as much as I love working and being creative and having time alone, art has been a form of avoidance for me throughout my life. It was sort of a preemptive strike against personal rejection or exclusion. I grew up thinking art was the one thing that I would always be able to count on, that couldn’t be taken from me, that I wouldn’t be separated from. And unfortunately, that carried through even into my adulthood, where I’d be in a relationship with someone and somewhere in the back of my mind I’d be thinking, Well, we might break up, she might get sick of me, so I better keep my priorities straight and focus on these comics here. It’s something I try to fight even now, especially having young kids, where you feel like their lives are zipping by so quickly and you don’t want to miss too much.

INTERVIEWER

You’ve mentioned how being a father has increased your sense of empathy, reduced your sense of narcissism. Did it also change your relationship to other key elements artists have to deal with like love, life, death?

TOMINE

I really credit this stage of my career—which I would say consists of The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist and Killing and Dying—to the arrival of my kids. Even if someone didn’t know anything about my personal life, they might sense a shift from my earlier books to these current ones. The earlier work is tied to all these things that aren’t part of my life anymore. I was almost hitting a point where I felt obligated to keep up the charade. I thought, The reason people like my work is because it’s about being young and single and living in California, and I better keep pumping this stuff out. Until the kids came along, I didn’t have the confidence to say, I’m just going to start writing stories about adults. Becoming a father opened up these other parts of my brain that I didn’t know existed.

INTERVIEWER

Near the end of Loneliness, you suffer a medical emergency that makes you reflect on your life and art in a great monologue. The book almost ends with the kind of ambiguous moment for which your stories are well known—or maybe controversial, depending on the reader. But then there’s a coda that does provide a kind of closure as you turn your angst into art, which brings the book full circle. And to me, that just makes explicit what I’ve always felt about your endings, which is that even though they are typically open-ended, there was always an implicit closure about art itself. The form of the story—of the work and the drawing and the writing and the complicated pleasure it brings to the reader and maybe to the artist—is the closure. Do you think your art and its process provide the closure you need, even if it’s a closure you have to constantly renew with every project?

TOMINE

That’s a good way to put it. I think the response to my endings caught me by surprise when I was younger, because it wasn’t anything I was doing intentionally or perversely, as I was sometimes accused of. There were definitely people who seemed to imply that I arbitrarily would remove the last bit of a complete story just to be frustrating or cool or something like that. But the truth is that there’s no aspect of my work I agonize over more than the endings. None of them have ever been random, as if the curtain dropped and I just gave up. They’re all deeply considered and perhaps overanalyzed. To me, as a creator, and also in terms of work that I enjoy as a viewer or a reader, a somewhat open-ended or ambiguous or surprising ending sends a chill up my spine more than just a perfect conclusion wrapped up with a tidy bow.

INTERVIEWER

In a review of your book Shortcomings, Junot Díaz describes the power of your work as coming partly from making political or historical issues secondary to a kickass story. You’ve said you’re not interested in statements or didacticism in your work, just honesty and realism. You also have said you’re not interested in identity politics. But when the issue of being a quote-unquote Asian American artist comes up, you already are one, simply by definition of being an Asian American. So content is less important to this definition of being an Asian American artist than simply being an Asian American, right? The fact that you’re Asian American means that anything you do is implicitly Asian American.

TOMINE

The first time I heard someone make that point, it felt like a real revelation. I think it’s great to open up the notion of what it means to be a blank artist. To say that by being who you are and by creating art, you are by definition an Asian American artist—that’s really liberating. And it’s something I didn’t feel I was afforded for a long time. I could tell that there was a lot of expectation from Asian American journalists and critics for me to be more issue-oriented, to make big statements, to tackle things head on, and that anything less than that was a rejection of responsibility. That kind of had my head spinning for a long time.

INTERVIEWER

I want to ask a question that may be offensive or irritating in its assumption. You’re Japanese American, but your work thus far hasn’t dealt explicitly with Japanese American history. The answer could simply be that you’re not interested. We don’t expect all white artists to write about George Washington, for instance. But I’m wondering if another possibility is whether Japanese American history is too mired in the problem of statements and didacticism. Is it too hard for you to approach that history with the honesty and realism that could help you overcome the explicit politics that you find so uninteresting?

TOMINE

I think you’re definitely onto something. In addition to that, there’s a bit of feeling overwhelmed and not knowing if my ability and especially my chosen art form are the best way to present that material to the world. I don’t think there’s anything wrong with deciding you’re not the best person for a certain challenge, especially with a topic that needs to be handled just right. But in addition to the anxiety, there’s a part of my brain that can’t help thinking, Well, what if I did a story about a guy who didn’t go to the incarceration camps and was a fugitive? Or, What if I focused on just one day in one family’s life? I’m always thinking about a side door into the story. I can’t get my brain to work in the traditional, straightforward, solemn narrative that’s generally applied to serious, historical material.

INTERVIEWER

I think sometimes about the fact that not every Japanese American was sent to the camps. Many Japanese Americans were not on the West Coast at the time. What happened to them? No one talks about that. So the problem with this issues-and-didacticism approach is that it tries to fit a huge multiplicity of experiences into one historical experience, which they may have shared, but which doesn’t exhaust the entire possibility of their lives. And part of the issue I think might be that the mechanism of American culture and art and its reward and recognition system are designed partly to put people into these categories. So you’re Japanese American, you should be doing Japanese American history, for example. And if you do, maybe you’ll get rewarded for it in a very different way. I think about how Colson Whitehead wrote a bunch of interesting books, but when he wrote about slavery, in The Underground Railroad, he won the Pulitzer Prize. It’s a great book, but that’s what he gets the Pulitzer Prize for. But at the same time comics can grapple with this kind of history. Obviously, Maus is a great example of being its own strange thing about a difficult history.

TOMINE

If you nose around at the bookstore a little bit, you’ll see that for every Maus or Persepolis, there’s like a hundred hideous books about a historical event or social protest moment or something that should be treated with great reverence, and it’s disgusting—like it actually denigrates the subject matter with its horrible aesthetic.

INTERVIEWER

I totally agree. I can’t get over history in my own work, and I find your not dealing with history to be really liberating. Or it may not be that you’re liberated from history so much as you’re working through your own obsessions, and history just doesn’t happen to be one of those.

TOMINE

I think there’s something to be said about the privilege of being a fourth-generation Japanese American growing up on the West Coast. Of course my parents and my grandparents were directly, horribly affected by the camps, but for whatever reason, I still don’t think the topic of race was as much of a presence in my life as it might’ve been for other kids. It’s possible that my family had been so deeply affected by issues of race that they instinctively insulated me and my brother from it to a degree, and strove to give us a carefree life, at least in that regard.

INTERVIEWER

In Loneliness you discuss the various microaggressions you’ve endured personally, which you treat with honesty and realism but also a lot of humor—Frank Miller refusing to say your name at an awards ceremony, a rejected stalker who calls you “an overrated Chinese asshole,” an unnamed comics artist who mistakes you for a computer repairman at Daniel Clowes’s house, a famous writer you approach whose response is to tell you he loves jujitsu. You’ve dealt with race before, but you’ve only recently started to deal with this issue of racial microaggressions in your life and career autobiographically. Is that because it was difficult to write about, or is it that you just didn’t have the right project to talk about these things?

TOMINE

I think that for me to use that raw material in something other than this book, I would have had to devise some fictional premise where it’s like, There’s an Asian American ballet dancer and when he goes to the ballet convention, a more famous … To construct a whole world where those same jokes and those same experiences could be used seemed unnecessarily complicated. So I think I was holding onto them for when I could just actually say, These particular things happened to me, especially because they are so odd and bizarre that it seemed important to me that the reader approaches it knowing that it’s essentially nonfiction, rather than just some weird thing that I invented.

INTERVIEWER

You don’t actually respond with anger to any of the incidents in Loneliness except when a random stranger harasses you and your family and lectures you about your parenting. You explode in anger and say, “I’ll spank YOUR ass!” Is anger a hard emotion for you to deal with autobiographically?

TOMINE

Not just in my work but in real life. It’s a point of contention in my marriage to a degree because my wife is from an Irish family from Brooklyn, and they are very openly expressive in both positive and negative emotions. I think my tendency is to internalize and minimize what I call anger, what my wife would call rage. She senses that it’s in me, and it annoys her that I would be stifling it to such a degree. But to be clear, I didn’t edit any acts of rage out of the book. It’s not like in reality the guy said “I love jujitsu” and then I screamed in his face and threw my glass on the ground or something. I really did just stand there awkwardly for a few minutes before shuffling away.

INTERVIEWER

In the New York Times Book Review, Ed Park said that “rage and fragility” are characteristic of your work. If you can’t express your rage explicitly, do you think that suppressed feeling is part of what gives energy to your work?

TOMINE

I think so. That’s definitely the case with a lot of my favorite cartoonists! Also, I think this book in particular would be a lot less palatable if it were infused with extreme rage throughout. And it wouldn’t be representative of me. There’s a way of reading this book that makes it seem like I’ve just been seething with pent-up hostility about all these experiences, and this is my way of getting back at those people. There might be like one degree of truth to that. But it’s also that time has affected my perception of these things. Many of the critical remarks that I quote from other people or from sources, I agree with now. I guess it just depends on how you read the work. But in the end, at least to me, the person I’m most critical of in the book is myself.

INTERVIEWER

Although you haven’t dealt with Japanese American history, you have touched on Japan in your work, and you’ve also written introductions for American reprints of manga by Yoshihiro Tatsumi. Can you talk about your relationship to Japan?

TOMINE

It was a constant background presence throughout my childhood, but I never visited as a child. However, there was never any doubt that that was my family’s background, that that was the culture we loved the most, sometimes in competitive ways. The one time I did go to Japan was for two weeks in 2003, and much to my surprise, it was one of those experiences where I landed and had this feeling I didn’t believe was possible, a feeling of belonging and connection and ease. Family members told me, People are going to spot you as an American from a mile away, no one’s going to speak Japanese to you, they’re going to come up and try out their English on you, they’re going to hand you the tourist menu when you sit down at a restaurant. And that turned out not to be the case at all. People just started speaking to me in Japanese and then probably thought I had brain damage or something when I couldn’t respond with more than a few simple words. I just felt like any kind of affinity or connection to the culture that I might have imagined was exponentially increased with the real experience of being there.

INTERVIEWER

Chris Ware, in his review of Killing and Dying, talked about the difficulty of adult comics achieving a certain level of critical recognition from the non-comics world. He said that in the comics world, nonfiction has been more successful at achieving wider recognition—I’m thinking of Maus and Persepolis. But he said Killing and Dying might be the first book of fiction to achieve that level of recognition for comics. Do you agree?

TOMINE

I think Killing and Dying definitely didn’t penetrate the public consciousness in the way that Maus or Persepolis did—you could just look at the Amazon rankings and see that—but I appreciate the compliment. It means a lot to me. And of course it would be nice if it were true in some way, but I understand why it’s not.

INTERVIEWER

I, as an outsider to the comics world, thought it did. One of the reasons I love your work is that you’re a great creator of comic books, whatever you want to call them, but also literature. I await your books with a great degree of anticipation because I think they achieve what great art is supposed to do, which is to deliver what John Updike called “the human news” in whatever format that it needs to arrive in. The culture simply hasn’t caught up with your work. Eventually that will happen! In the interim, you’ll have more material to draw from in this idea that you’re an artist maybe just a step ahead of your time.

TOMINE

Thank you. That’s nice of you to say. We’ll see. I don’t know. I don’t feel like I’ve been cheated or I’ve missed out on some audience that I just haven’t been able to reach. I’ve been able to do exactly the kind of work I wanted to, and to be honest, I’ve actually been surprised by the reception I’ve received. So I don’t want to make it sound like I’m sitting around thinking my work should be as popular as Maus. I don’t think that at all. I think it’s reached an appropriate readership.

Viet Thanh Nguyen is the author of the Pulitzer Prize–winning novel The Sympathizer and its forthcoming sequel The Committed (March 2021).

Images from The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist , © Adrian Tomine, courtesy of Drawn & Quarterly.

The post Escaping Loneliness: An Interview with Adrian Tomine appeared first on The Paris Review.

October 14, 2020

The Art of Distance No. 29

In March, The Paris Review launched The Art of Distance, a newsletter highlighting unlocked archive pieces that resonate with the staff of the magazine, quarantine-appropriate writing on the Daily, resources from our peer organizations, and more. Read Emily Nemens’s introductory letter here, and find the latest unlocked archive selection below.

“This week we continue our serialization of Edward P. Jones’s ‘Marie,’ a timely story from our archive about a tough-minded woman who seeks connection while facing the challenges of aging and bureaucracy in Washington, D.C. If you missed part 1, you can read it here and then scroll down for the next installment of the story. We’ll post parts 3 and 4 in the coming weeks. Don’t forget that subscribers to the print magazine need only link their account for digital access to a treasure trove of stories, poems, landmark interviews, art portfolios, and more. As ever, we wish you a safe and sane week and hope that this story provides focus, calm, and a bit of relief. Read on for part 2 of ‘Marie,’ by Edward P. Jones.” —Craig Morgan Teicher, Digital Director

Photo: © Peter / Adobe Stock.