The Paris Review's Blog, page 141

October 26, 2020

The Art of Distance No. 31

In March, The Paris Review launched The Art of Distance, a newsletter highlighting unlocked archive pieces that resonate with the staff of the magazine, quarantine-appropriate writing on the Daily, resources from our peer organizations, and more. Read Emily Nemens’s introductory letter here, and find the latest unlocked archive selection below.

“Below, we offer the fourth and final installment of ‘Marie,’ by Edward P. Jones, originally published in the Review in 1992. Over the past month, we’ve read along as Jones explores the frustrations of government bureaucracy, the balm of friendship, and the consequences of a strong, open-palmed slap. The story examines what happens when society overlooks and underappreciates the elderly, and what can come to pass when those same elders are acknowledged and embraced. I will hold on to the lines that closed last week’s installment of ‘Marie’ for a long time: ‘She thought that she was hungry and thirsty, but the more she looked at the dead man and the sleeping woman, the more she realized that what she felt was a sense of loss.’ So many have felt a sense of loss this year; that grief can take on a more visceral sensation, an emptiness or need. But I will also remember Jones’s recollection of what inspired him to write ‘Marie’ and the other stories of his first collection, Lost in the City. In his Art of Fiction interview, he explains that after grad school, he moved to Northern Virginia and all but stopped writing. ‘I just went back to living my life, you know, but I was thinking about the stories. I felt, partly, that I wasn’t really ready or able to do them. Then, in the late eighties, two guys died whom I had worked with … They had both wanted to be writers. And I thought, Here I am, still alive, in good health … It seemed a shame to continue like that, so I started working on the stories.’ I don’t posit that every loss can encourage someone to take up a torch—life’s correlation is nowhere near that neat. But I don’t want to forget that the two can exist alongside one another, loss and inspiration, the missed opportunity and the realized one. With that, enjoy the conclusion of ‘Marie,’ and have a safe week.” —EN

P.S. If you haven’t already, be sure to read part 1, part 2, and part 3 of “Marie.”

Photo: Ben Franske. CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Two days later, the Social Security people sent her a letter, again signed by John Smith, telling her to come to them one week hence. There was nothing in the letter about the slap, no threat to cut off her SSI payments because of what she had done. Indeed, it was the same sort of letter John Smith usually sent. She called the number at the top of the letter, and the woman who handled her case told her that Mr. White would be expecting her on the day and time stated in the letter. Still, she suspected the Social Security people were planning something for her, something at the very least that would be humiliating. And, right up until the day before the appointment, she continued calling to confirm that it was okay to come in. Often, the person she spoke to after the switchboard woman and before the woman handling her case was Vernelle. “Social Security Administration. This is Vernelle Wise. May I help you?” And each time Marie heard the receptionist identify herself she wanted to apologize. “I whatn’t raised that way,” she wanted to tell the woman.

George Carter came the day she got the letter to present her with a cassette machine and copies of the tapes they had made about her life. It took quite some time for him to teach her how to use the machine, and after he was gone, she was certain it took so long because she really did not want to know how to use it. That evening, after her dinner, she steeled herself and put a tape marked “Parents/Early Childhood” in the machine.

… My mother had this idea that everything could be done in Washington, that a human bein’ could take all they troubles to Washington and things would be set right. I think that was all wrapped up with her notion of the gov’ment, the Supreme Court and the president and the like. “Up there,” she would say, “things can be made right.” “Up there” was her only words for Washington. All them other cities had names, but Washington didn’t need a name. It was just called “up there.” I was real small and didn’t know any better, so somehow I got to thinkin’ since things were on the perfect side in Washington, that maybe God lived there. God and his people … When I went back home to visit that first time and told my mother all about my livin’ in Washington, she fell into such a cry, like maybe I had managed to make it to heaven without dyin’. Thas how people was back in those days …

The next morning she looked for Vernelle Wise’s name in the telephone book. And for several evenings she would call the number and hang up before the phone had rung three times. Finally, on a Sunday, two days before the appointment, she let it ring and what may have been a little boy answered. She could tell he was very young because he said hello in a too loud voice, as if he was not used to talking on the telephone.

“Hello,” he said. “Hello, who this? Granddaddy, that you? Hello. Hello. I can see you.”

Marie heard Vernelle tell him to put down the telephone, then another child, perhaps a girl somewhat older than the boy, came on the line. “Hello. Hello. Who is this?” she said with authority. The boy began to cry, apparently because he did not want the girl to talk if he couldn’t. “Don’t touch it,” the girl said. “Leave it alone.” The boy cried louder and only stopped when Vernelle came to the telephone.

“Yes?” Vernelle said. “Yes.” Then she went off the line to calm the boy who had begun to cry again.

“Loretta,” she said, “go get his bottle … Well, look for it. What you got eyes for?”

There seemed to be a second boy, because Vernelle told him to help Loretta look for the bottle. “He always losin’ things,” Marie heard the second boy say. “You should tie everything to his arms.” “Don’t tell me what to do,” Vernelle said. “Just look for that damn bottle.”

“I don’t lose noffin’. I don’t,” the first boy said. “You got snot in your nose.”

“Don’t say that,” Vernelle said before she came back on the line. “I’m sorry,” she said to Marie. “Who is this? … Don’t you dare touch it if you know what’s good for you!” she said. “I wanna talk to grandaddy,” the first boy said. “Loretta, get me that bottle!”

Marie hung up. She washed her dinner dishes. She called Wilamena because she had not seen her all day, and Wilamena told her that she would be up later. The cassette tapes were on the coffee table beside the machine, and she began picking them up, one by one. She read the labels: Husband No. 1, Working, Husband No. 2, Children, Race Relations, Early D.C. Experiences, Husband No. 3. She had not played another tape since the one about her mother’s idea of what Washington was like, but she could still hear the voice, her voice. Without reading its label, she put a tape in the machine.

… I never planned to live in Washington, had no idea I would ever even step one foot in this city. This white family my mother worked for, they had a son married and gone to live in Baltimore. He wanted a maid, somebody to take care of his children. So he wrote to his mother and she asked my mother and my mother asked me about goin’ to live in Baltimore. Well, I was young. I guess I wanted to see the world, and Baltimore was as good a place to start as anywhere. This man sent me a train ticket and I went off to Baltimore. Hadn’t ever been kissed, hadn’t ever been anything, but here I was goin’ farther from home than my mother and father put together … Well, sir, the train stopped in Washington, and I thought I heard the conductor say we would be stoppin’ a bit there, so I got off. I knew I probably wouldn’t see no more than that Union Station, but I wanted to be able to say I’d done that, that I step foot in the capital of the United States. I walked down to the end of the platform and looked around, then I peeked into the station. Then I went in. And when I got back, the train and my suitcase was gone. Everything I had in the world on the way to Baltimore …

… I couldn’t calm myself down enough to listen to when the redcap said another train would be leavin’ for Baltimore, I was just that upset. I had a buncha addresses of people we knew all the way from home up to Boston, and I used one precious nickel to call a woman I hadn’t seen in years, cause I didn’t have the white people in Baltimore number. This woman come and got me, took me to her place. I ’member like it was yesterday that we got on this streetcar marked 13TH AND ONE. The more I rode, the more brighter things got. You ain’t lived till you been on a streetcar. The further we went on that streetcar—dead down in the middle of the street—the more I knowed I could never go live in Baltimore. I knowed I could never live in a place that didn’t have that streetcar and them clackety-clack tracks.

She wrapped the tapes in two plastic bags and put them in the dresser drawer that contained all that was valuable to her: birth and death certificates, silver dollars, life insurance policies, pictures of her husbands and the children they had given each other and the grandchildren those children had given her and the great-grands whose names she had trouble remembering. She set the tapes in a back corner of the drawer, away from the things she needed to get her hands on regularly. She knew that however long she lived, she would not ever again listen to them, for in the end, despite all that was on the tapes, she could not stand the sound of her own voice.

Read Edward P. Jones’s Art of Fiction interview, which is free for a limited time. And don’t forget that as a subscriber, you can unlock “Marie” in its entirety today, along with many, many more stories.

The Ghosts of Newspaper Row

Newsboys and newsgirls on Newspaper Row, Park Row, NYC. Photo by Lewis Wicks Hine from Library of Congress

The reporters would pant up five flights of stairs to reach their dingy, dim newsrooms, where light eked through the dirt-cloaked windows and the green shades over the oil lamps were burned through with holes. They wended through hobbled tables piled high with papers, walked past cubbies so chaotically stuffed with scrolled proofs no outsider could guess the system. The reporters reeked of five-alarm smoke, or had coat pockets bulky with notes and a pistol from the front, or were tipsy from a gala ball, or dusty from a horse race. If they held important news in those notebooks, a copy boy would crowd by their elbow as they wrote, snatch the ink-wet sheets from their hands, and rush them off to the copyholder to “put them into metal.”

The center of news in the nineteenth century lined the streets around City Hall Park, only a short sprint to Wall Street, close to the harbor. News sailed in on the wind. Newspaper schooners cut through the waves and fog to land their men onboard the arriving European steamers before the less affluent New York newspapers could get out there with their rowboats.

Amid recent renovations on Park Row, construction workers discovered artifacts of news reporters inside the walls—papers and typewriters. Who knows what ghosts might lurk there still?

“Journalism is the real Minotaur,” nineteenth-century reporter Stephen Fiske remarked, looking back on his career. “It demands every year a fresh supply of young men and women: devours them, destroys them, and is ready for another batch of tender victims from colleges or country towns.” He had begun as a columnist at age twelve. Other reporters jumped in audaciously in their twenties, such as Henry Villard, a German immigrant who rapidly taught himself English so as to cover the Lincoln–Douglas debates.

They were almost entirely anonymous. Inherited British etiquette dictated that to claim a byline would be immodest. It would risk encouraging flamboyance, even spark recklessness. Instead, they represented their team: the New York Times, the New-York Tribune, the New York Herald, and on. Like a priest of the same era forbidden to use I, reporters denied themselves the honor of possessing their writing. They seeded their identity into the words themselves.

They wrote well to impress the reporter seated next to them, or rivals at the other papers. They strove to create in words the moving image of an event or the quirks of an important person. Photographic evidence was scant at that time. Reporters needed to be the eyes for those too far away to see. They wrote well to lasso in the readers who constantly strayed. Three-quarters of a newspaper’s customers faded away each year, and newspapers needed to lure fresh ones.

The reporters wrote fast. They fed the street-level, steam-driven presses that each inked some fifty miles of paper each day. They wrote to feed the conveyor belt of hooks that ran along the ceiling, from the editor to the foreman to the typographer. Stories hung like cow carcasses headed to butchery. “The fevered pencil flies, every nerve is strained, every brain-cell is clear,” wrote one reporter of that time. “Comment, description, reminiscence, dialogue, and explanation flow upon the impatient sheets in short paragraphs, like slivers of crystal,” wrote Julian Ralph, a British reporter who worked in New York City, in 1893.

They focused even amid the clicking of the telegraph, the shouting of the editors, the joking of the office boy, and the copy cutters pressing their deadlines. The only relief came when the Associated Press marked the final delivery of the day’s breaking news. “Over the wires and at the end of the last sheet of flimsy has come the welcome message, ‘Good-night,’ ” one editor, Melville Philips, recalled.

The reporters mixed among the rich for sources or dared to knock at the most squalid crime dens. They heard out their critics; one tall, thin writer bent like a hook to politely listen to the manager of the theater whose production he had unflatteringly dissected, begged repetition (indicating bad hearing), and then, having failed to make out the tirade a second time, asked again and again, until wrath had withered.

They competed to file. News lay out in distant towns and the reporter would pluck it like a giant’s eye and race back with the prize to send over the closest telegraph. Julian Ralph remembered competing with a Tribune man when out on assignment. “We had to run three miles over a plain that was one great glare of ice. He was the faster runner and appeared to have everything his own way, but suddenly he slipped and rolled down the side of a gully to fetch up at the bottom badly hurt. The tearing of his clothes and peeling of his face did not bother him, but his ankle was sprained and he could not walk without help. ‘I give up,’ said he. ‘Will you help me to the village?’ ‘I don’t know,” I replied. “Is the wire mine?’ ”

Though readers rarely knew who wrote what, the reporters knew each other well. Journalists scuffled in the streets, smacked each other with canes. They celebrated in private gathering spots. A few might be sufficiently bohemian enough to share a beer at Pfaff’s on Broadway near Bleecker with Walt Whitman, the former editor of the Brooklyn Eagle, or have angled into respectability at the Lotos Club. But they more likely visited the Bread and Cheese Club on Broadway and Reade Streets or the Sketch Club.

They understood how to dowse for a story, to identify the vibrating image that could stir emotion. A reporter remembered a day with nothing but fourth-rate news unfolding, when he scanned every line of the afternoon paper with the managing editor, hunting for the next day’s feature. The managing editor yelled out, “I have it!” A tiny baby girl had been found buried in Harlem. “The only uncommon item was that the infant was richly dressed.”

The managing editor gave the orders: “See the place where the baby was found, the policeman who found it; follow it to Matron Webb’s room in the police headquarters, where all foundlings are first taken, and get a long full account from the matron of … the most remarkable, the strangest, most pathetic, moving or stirring experiences she has had… Then … go to the asylum where these babies are brought up, and to the Potter’s Field where they are buried.”

William Cullen Bryant, editor at the Evening Post and a poet, hung on the newsroom wall his “Index Expurgatorious” for writers, his commandments for striking out words that failed to chime the way others could: “Jeapordize should not be used.” “Gratuitous means ‘without payment.’ ” “Jewelry for jewels.” Don’t use “bulls and bears” for Wall Street.

They sacrificed human comforts, like Gerald Hallock who stayed in the city to run the Journal of Commerce while his family lived in New Haven. He collapsed onto a cot in the office each night, took lonely dinners in restaurants, and “slept on his arms,” the image of a man devoted to his desk. When reporting a fire, he fell into a newly dug cellar in the dark streets. “I sat down on the curbstone to rub myself, and, seeing the light of the fire brighten up, I started for it,” he told a friend.

Julian Ralph remembers the wealthiest man in the country, baffled, observing to him after an interview: “You mastered the intricacies of financial matters in hours and yet you persist in this profession with no pecuniary gain unless one’s aim is to run a paper?” Ralph had no satisfactory answer. His desire to use his intellect to fill newspaper columns was inexplicable except as a relationship with fellow journalists and the dead ones.

Because of their anonymous voices, we know about the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, and Lincoln’s sorrows, and the draft riots, when violent white mobs beat passersby, lynched and mutilated Black people, and torched homes. The anonymous journalists reported those incidents including peculiar details, such as expensive pianos smashed with pickaxes, mirrors shattered by stones. “One fellow appeared at a window with a picture of the President, spat on it, split it over his knee and hurled it into the street, where it was quickly trampled into atoms. Then, in a half a dozen places at once, the flames burst forth. So rapidly did they spread that some of the plunderers in the house had to escape from the windows by means of ladders.”

They covered the heat wave of 1896 during which fifteen hundred New Yorkers perished. “The spot that was perhaps hottest of all was the glaring asphalted pass in front of the City Hall. A man threw up his hands and fell there shortly before noon. A thermometer on the steps at the time held mercury that was at the 112-degree mark.”

Or those that survived: “The close structure of the lower part of the Third Avenue Elevated Railroad was a boon to the east side all day. Under it was real shade and were it not for the humidity the shelter would have been perfect. Hundreds of boys sat along the curbs, too listless for play or mischief. Men came out of the broiling sun above Canal Street or below the City Hall and stopped to rest and breathe beneath the rumbling trains.”

They climbed the inner scaffolding of the Statue of Liberty before it was clad with copper, describing the experience in the third person. “He looked downward, and the earth seemed further than the sky. The rounds of the ladders had disappeared and there seemed to be nothing by which to descend but the iron beams of the framework. The swaying of the treetops beneath unnerved him as much as the sweeping movement of the long arm above… Just as he got to the forearm a triumphant shout reached his ears. The [cartoon] artist had both his hands clasped on Liberty’s wrist and was ‘feeling her pulse.’ He was the first that ever burst into that dizzy spot except the workmen. No such glorious view of New York bay was ever obtained before. The air was clear and there was no limit upon the human sight except human frailty. Great ships looked like sloops, schooners like sailboats, men like moving sticks. Even the Brooklyn Bridge seemed a thing of the earth’s surface, which could be touched with the hand by any one sailing under it.”

All writers contribute to humanity’s intellectual compost, nourishing future ideas, but few do so more plainly than those anonymous writers. As Edward G. P. Wilkins wrote about one of his gifted colleagues, “his writings are buried in the files of ‘The Herald,’ ‘The Saturday Press,’ and ‘the Leader,’ and they are buried forever.” Those reporters did not cherish the silly illusion that their names would echo through the ages. They skipped the stage of “I’ve never heard of him” to immediately become what might be valued forever: their words.

In the Cypress Hill Cemetery in Queens, on a hilltop at the “brow of a small hill, commanding a beautiful view of the country for many miles around, with Jamaica Bay and ocean in the distance,” is a graveyard, acquired in 1871 by the New York Press Club, originally for 360 graves for “friendless journalists.” The space was intended for newspaper people who “die in the city without means or inclination to be buried elsewhere.” At an 1887 ceremony, thousands gathered to dedicate a thirty-eight-foot obelisk inscribed NEW YORK PRESS BURIAL PLOT. Under sunny skies, Chauncey Depew, the railroad president and sought-after orator, honored the fallen: “The reporter, with no incentive but his duty, outdoes the soldier, and telegraphs to his paper an account that electrifies the world, but bears no signature.”

An 1866 obituary for a newspaperman expressed the writer’s fervent hope of what such people might earn in the afterlife: “There he shall be able to see the immense masses of mind he has moved, all unknowing and unknown as he has been, during his weary pilgrimage on earth. There he will find all articles credited—not a clap of his thunder stolen; and there shall be no horrid typographical errors to set him in a fever.”

Elizabeth Mitchell is the author of Lincoln’s Lie: A True Civil War Caper Through Fake News, Wall Street, and the White House (October 2020/Counterpoint Press).

October 23, 2020

Staff Picks: Splorts, Seers, and Sentences

Brian Dillon.

I would have been happy to read Brian Dillon’s Suppose a Sentence at any time, but that the book came out in this overwhelming, apocalyptic year made it particularly welcome. The focus here is narrow—twenty-seven essays about twenty-seven discrete sentences by twenty-seven different writers—and entirely idiosyncratic: he offers no “general theory of the sentence” and no advice or suggestions about writing a good or great or beautiful one. He examines sentences that interest or move him and writes, as he says, not necessarily about them but toward them. The book has a lot of what I can only call pleasure—of the kind that I imagine athletes or dancers experience when they are doing what they do, which is then communicated to those watching them do it. I share with Dillon some misgivings about general theories and overarching ideas, but in thinking about the writing I enjoy most, this quality feels like the one constant: that the author takes some pleasure in using these muscles and finding them capable of what they are asked. That delight is evident both in the sentences Dillon looks at and in those he writes himself. —Hasan Altaf

Last week, I had to laugh when I came across Cameron Awkward-Rich’s Dispatch in a way that felt peak 2020: a recommendation over Zoom private messages. I rushed to respond before the meeting ended and the messages disappeared—yes, I knew Awkward-Rich’s earlier work, and yes, I’d check out his latest book—and then, still laughing, I bought the collection. Rogue beginnings aside, I have been making an effort to dive into the full collections of poets I used to know one poem at a time, whether in anthologies or on the internet. It has been a good exercise, sitting with the voice and thoughts of one writer, especially with such an embodied body of work as this. Dispatch is a collection worth reading in full, preferably in one sitting, and then coming back to again, which I have already done only a week removed from my first visit. The world according to Awkward-Rich is not a happy thing. But it’s not entirely a sad thing either. The poems in this collection offer a way to live. In “The Cure for What Ails You,” there is the desire for comfort, but none comes. Awkward-Rich writes: “Like a child I just want / someone to touch me with cool hands / & say yes, you’re right, something is wrong / stay here in bed until the pain stops.” The whole collection is contained within this unfulfilled wish to have the wrong thing if not righted then at least recognized. But what does it mean to be recognized, the poet asks, and who gets to be seen with good intentions? Dispatch delivers on the promise of its title: it is a message sent onward. And it’s the process of moving forward, as the final poem ends, “until we are all free.” —Langa Chinyoka

Elfriede Jelinek. Photo: G. Huengsberg. CC BY-SA 2.5, via Wikimedia Commons.

There’s no writer quite like Elfriede Jelinek. From the first work of hers I ever read—the 1989 novel Lust—I’ve been fascinated with her formally adventurous, always acidic explorations of power, gender, money, and politics. Her latest work to appear in English, the 2017 play On the Royal Road: The Burgher King (translated from the German by Gitta Honegger), is no exception. As the pun in the title suggests, this is a work about greed; written in the three weeks after Donald Trump’s 2016 election, it’s a monologue told from the perspective of a female seer who takes the form of Miss Piggy, her eyes blinded and bloodied à la Tiresias. The king that she describes sounds eerily similar to the U.S. president, down to the wall, the debts, and the crown of hair. Frankly, Jelinek is better at writing about the present moment in U.S. politics than most American writers; she understands that we exist in a time typified by its dishonesty and that America is no exception to the rules. The truth, the seer observes, can be bought “on credit, like everything else.” I haven’t the vaguest idea what will happen in the next week and a half before the U.S. presidential election—I’m no seer—but at least I have Jelinek’s sharp insights into contemporary capitalism and the global rise of right-wing populism beside me. —Rhian Sasseen

Emily Wilson’s English translation of the Odyssey—the first ever by a woman—has been greatly celebrated. Her criticism, it transpires, is no less captivating. In the October 8, 2020, issue of the London Review of Books, Wilson reviews three new translations of the Oresteia. She makes quick work of the elite academic hand-wringing that is taking a small eternity elsewhere. “Many published ancient Greek and Roman translations, by women as well as men, share a pedestrian, archaizing, clunky style–regardless of the stylistic diversity of the original texts. Conversely, it is quite possible, in theory, for elderly white men to offer original ideas and fresh perspectives. But in this particular case … ” I’ll imagine for a second that those words aren’t the pulse quickener for you that they are for me. But Wilson’s review presents the full roster of muses that the best LRB reviews do. There is poetry: “Whatever’s burned and poured and wept on alters.” There is history. There is drama: “Clytemnestra bares her breast to remind [her son] that the body he threatens to kill is the source of his life.” There is also politics. Wilson proposes that the Oresteia is about “the subordination of female to male, of moral right and wrong to the making of expedient speeches and the passing of laws for what Plato would later call the ‘advantage of the stronger.’ ” If this is the season we look, clear-eyed, at our monuments—and I hope it is—I would like to have Wilson as a guide. —Julia Berick

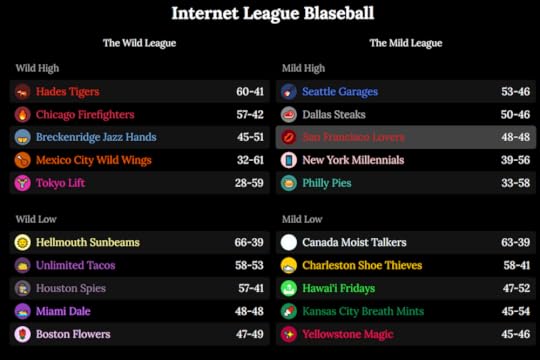

My latest obsession is perhaps one of the most difficult works I’ve had to explain. Blaseball is essentially an absurdist fantasy baseball league where its creators and fans alike collaborate to shape a fictional world. Part game, part social experiment, part existential horror, and entirely bizarre, Blaseball simulates a season of baseball every week at a rate of a game per hour. At the end of the week, the top teams move on to a postseason, and a champion emerges. Although that all might sound fairly standard, keep in mind that some of the weather conditions under which the games take place include “blooddrain,” “reverb,” and black holes. The players have ridiculous names like Blood Hamburger and Peanut Bong, blood types like “grass,” and numbers of fingers that usually amount to far more than ten. This is entertaining enough on its own, but the real magic of Blaseball comes from its community, which aims for equal parts chaos and delight. Because Blaseball itself is almost entirely text-based, fans regularly give visual manifestation to the various players and write their backstories, only for the creators of Blaseball to turn around and incorporate the fan material into the league’s canon. It’s a collaboration unlike anything I’ve ever seen. This push-and-pull between the producers of Blaseball and its audience creates some spectacular moments, such as when a group of fans exploited the in-universe rulebook to exercise necromancy and bring a dead player back to life, only for that player (named Jaylen Hotdogfingers) to in turn claim the lives of four opponents as recompense for her resurrection. You see, Blaseball is a deadly “splort” (the official term). Season 11 is coming to a close this weekend, and the Grand Siesta (a short hiatus for the producers) is set to begin. But when Blaseball returns, I can’t recommend it enough. Born out of the absurdity of quarantine in a year like 2020, Blaseball is the most entertaining and unique event on the internet right now. —Carlos Zayas-Pons

The league standings as of Season 11, Day 97 of Blaseball.

October 22, 2020

Scenes from a Favela

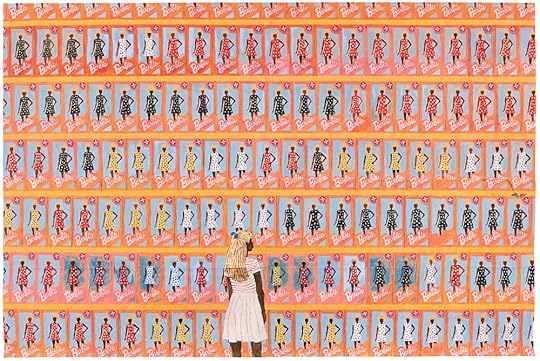

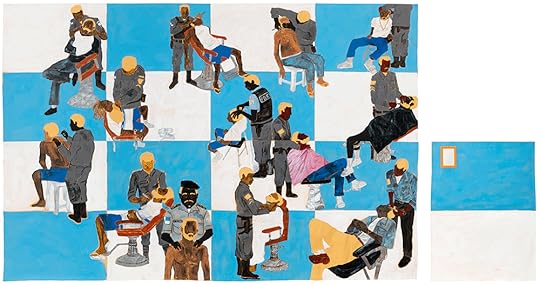

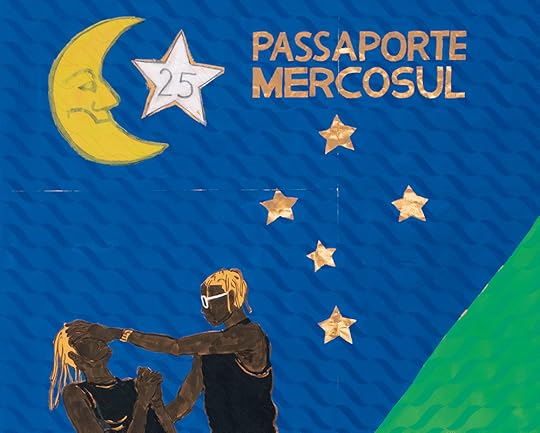

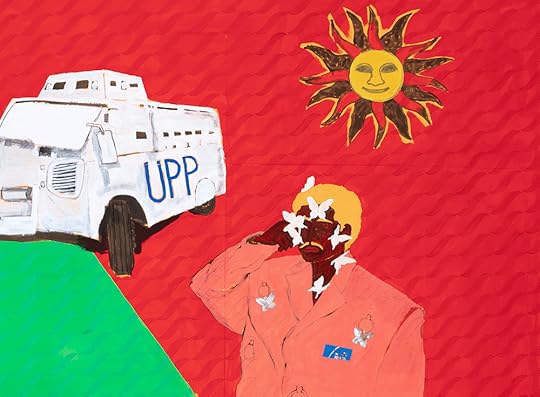

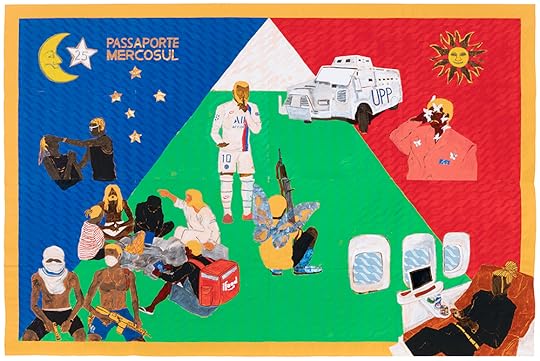

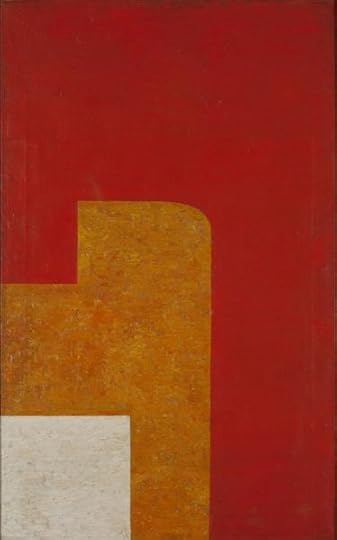

Maxwell Alexandre’s sprawling, colorful paintings sing odes to Rocinha, the Rio de Janeiro favela where he was raised and currently lives. His work has a sort of Where’s Waldo? quality to it, presenting rich fields of figures huddling, sweating, texting, fighting, living alongside one another. In Close a door to open a window, a person reclining in a luxurious plane cabin sits directly across from two masked men clutching firearms. In Pisando no céu, a girl stands before a wall of Barbie dolls. Dalila retocando meus dreads depicts a barbershop run by police officers, the state holding a literal razor to citizens’ necks. Alexandre’s first show in the United Kingdom, “Pardo é Papel: close a door to open a window,” will open at David Zwirner’s London gallery on November 12 and remain on view through December 19, 2020. A selection of images from the exhibition appears below.

Maxwell Alexandre, Pisando no céu, 2020. © Maxwell Alexandre. Photo: Gabi Carerra. Courtesy the artist, A Gentil Carioca, and David Zwirner.

Maxwell Alexandre, If you could die and come back to life, up for air from the swimming pool (detail), 2020. © Maxwell Alexandre. Photo: Gabi Carerra. Courtesy the artist, A Gentil Carioca, and David Zwirner.

Maxwell Alexandre, Dalila retocando meus dreads, 2020. © Maxwell Alexandre. Photo: Gabi Carerra. Courtesy the artist, A Gentil Carioca, and David Zwirner.

Maxwell Alexandre, Close a door to open a window (setail), 2020. © Maxwell Alexandre. Photo: Gabi Carerra. Courtesy the artist, A Gentil Carioca, and David Zwirner.

Maxwell Alexandre, Close a door to open a window (detail), 2020. © Maxwell Alexandre. Photo: Gabi Carerra. Courtesy the artist, A Gentil Carioca, and David Zwirner.

Maxwell Alexandre, Close a door to open a window (detail), 2020. © Maxwell Alexandre. Photo: Gabi Carerra. Courtesy the artist, A Gentil Carioca, and David Zwirner.

Maxwell Alexandre, Close a door to open a window, 2020. © Maxwell Alexandre. Photo: Gabi Carerra. Courtesy the artist, A Gentil Carioca, and David Zwirner.

“Pardo é Papel: close a door to open a window” will be on view at David Zwirner’s London gallery from November 12 through December 19, 2020.

The Lesbian Partnership That Changed Literature

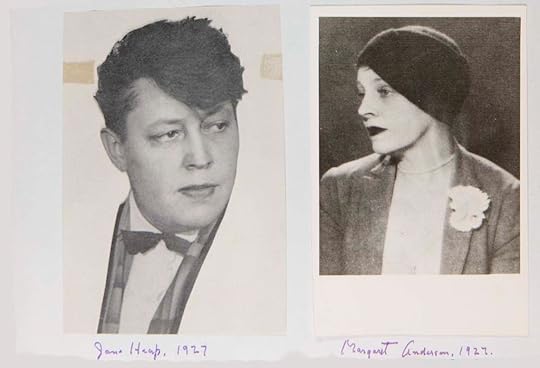

Jane Heap and Margaret C. Anderson, 1927

In the early thirties, for a certain clique of Left Bank–dwelling American lesbians, the place to be was not an expat haunt like the Café de Flore or Le Deux Magots. Nor was it Le Monocle, the wildly popular nightclub owned by tuxedoed butch Lulu du Montparnasse and named for the accessory worn to signal one’s orientation. According to the writer Solita Solano, the “only important thing in Paris” was a study group on the philosophies of the Greek-Armenian mystic George Ivanovich Gurdjieff, held at Jane Heap’s apartment. Heap, a Kansas-born artist, writer, and gallerist, was Gurdjieff’s official emissary, a rare honor. Under her supervision, the group engaged in intense self-revelation, narrating the stories of their lives without censoring or embellishing. As the author Kathryn Hulme explained in her memoir, Undiscovered Country: A Spiritual Adventure, the goal was to uncover the real I and thus escape being “a helpless slave to circumstances, to whatever chameleon personality took the initiative.”

Among those who gathered in Heap’s small sitting room were Janet Flanner, the New Yorker Paris correspondent and Solano’s lifelong partner; the journalist and author Djuna Barnes; and the actress Louise Davidson. One attendee, Hulme noted, would enter the room “like a Valkyrie” and “knew how to load the questions she fired at Jane, how to bait her to reveal more than perhaps was intended for beginners.” The Valkyrie was Margaret Caroline Anderson, founder of the trailblazing Little Review, with whom Heap had first encountered Gurdjieff in New York in the early twenties. Heap and Anderson, whose friendship outlasted a love affair and a professional partnership, were kindred geniuses with an exclusive affinity. When Barnes, after a fling with Heap, marveled at her “deep personal madness,” Anderson replied: “Deep personal knowledge—a supreme sanity.” Heap called Anderson “my blessed antagonistic complement.” Via their shared endeavors and the cross-pollination of their ideas—artistic, literary, and spiritual—these two remarkable women left an indelible imprint on avant-garde culture between the wars.

Margaret C. Anderson

They first met one afternoon in February 1916, when Heap dropped by the The Little Review’s office in the Fine Arts Building on South Michigan Avenue in Chicago. She was thirty-two, with cropped dark hair, a long straight nose, strong cheekbones, and a strikingly androgynous style. A typical outfit was a men’s frock coat, a high-necked shirt, and a tie. In winter, she added a Russian fur hat, and she always wore bright red lipstick. Anderson, three years her junior, had gone through a tomboy phase but was now exquisitely feminine, with a knack for projecting flawless chic despite never having any money. “Her profile was delicious,” Flanner recalled in a posthumous tribute for The New Yorker, “her hair blond and wavy, her a laughter a soprano ripple, her gait undulating beneath her snug tailleur.” Anderson set great store by looks and charm, and believed her conversation improved when she felt attractive. To an earnest young short-story writer who came to her for advice, she said: “Use a little lip rouge, to begin with. Beauty may bring you experiences to write about.”

Heap’s handsome face, Anderson wrote in her memoir The Fiery Fountains, resembled Oscar Wilde’s “in his only beautiful photograph.” And yet, “when Jane talked you were conscious of only one feature—her soft deep eyes, in which you could watch thought take form … thought that was always clearest when she talked of the indefinable, the vast, or the unknown.” An unusual childhood had cultivated Heap’s questing, expansive mind. Her English father was a warden at the Topeka State Hospital, and he lived with his family in the hospital grounds. Young Jane roamed the place, lonely and thirsty for knowledge. Adults were poor sources of enlightenment, she found, except for the patients, who seemed to possess an authentic truth and authority that others lacked. The asylum, Heap wrote in a 1917 Little Review piece, “was a world outside of the world, where realities had to be imagined…Very early I had given up everyone except the Insane.” She dreamed of one day meeting those ultimate imaginers of reality, artists. “Who had made the pictures,” she wondered, “the books, and the music in the world?”

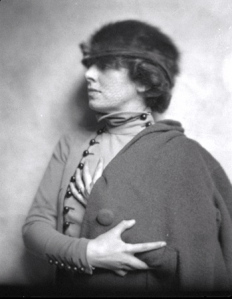

Man Ray, Jane Heap, c.1926

Heap studied at the Art Institute of Chicago, and she returned to the city after spending a year in Germany with her first serious girlfriend. During her twenties she taught art, designed theatrical sets, acted in plays, and fell in and out of love. “I believe in living a little more than necessary,” she wrote at age twenty-four, “seeing and believing life to be as one wished it to be, creating beauty where it doesn’t happen to exist.” When she met Anderson, she was nursing a broken heart and craving a grander conduit for her ambitions. At a stroke both problems were solved: she became coeditor of the two-year-old Little Review and moved with Anderson to California. They rented a ranch house in the redwood forests of Marin County and talked, nonstop, about art. “My mind was inflamed by Jane’s ideas,” Anderson reminisced in her memoir My Thirty Years’ War, “because of her uncanny knowledge about the human composition, her unfailing clairvoyance about human motivation. This is what I had been waiting for, searching for, all my life.”

Anderson grew up in Indiana, one of three sisters in a middle-class family. At age twenty-one she dropped out of a women’s college in Ohio, where she studied piano, to move to Chicago. Her bemused parents, who expected her to marry and settle down in their “country clubs and bridge” milieu, wanted to know what on earth she was seeking. Self-expression, she said, which meant “being able to think, say, and do what you believed in.” Her father retorted: “Seems to me you do nothing else.” In Chicago, Anderson became a magazine journalist and a prolific book critic. But she was always restless for her next big adventure. The Little Review was conceived when she attributed a depressed mood to “nothing inspired” happening in her life. The remedy came to her: she would launch the most interesting magazine of all time. “I knew that someone would give the money,” she wrote in My Thirty Years’ War. “This is one kind of natural law I always see in operation. Someone would have to. Of course someone did.” She had just turned twenty-seven.

Anderson’s guiding editorial principle was the superiority of artists over intellectuals. As she bluntly put it: “I didn’t consider intellectuals intelligent. I never liked them or their thoughts about life.” Merit would be her sole criteria for accepting work, with no pandering to commercialism or conservatism, or indeed to any ideology—though she had a fondness for anarchism and was an avowed feminist. Fundamental to art, Anderson insisted, was liberty. In the introduction to the March 1914 inaugural issue, she offered this impassioned address:

If you’ve ever read poetry with a feeling that it was your religion, your very life; if you’ve ever come suddenly upon the whiteness of a Venus in a dim, deep room; if you’ve ever felt music replacing your shabby soul with a new one of shining gold; if, in the early morning, you’ve watched a bird with great white wings fly from the edge of the sea straight up into the rose-colored sun—if these things have happened to you and continue to happen till you’re left quite speechless with the wonder of it all, then you’ll understand our hope to bring them nearer to the common experience of the people who read us.

During its first couple of years, The Little Review featured work by Sherwood Anderson, John Galsworthy, Rupert Brooke, Emma Goldman, W. B. Yeats, H. D., and Amy Lowell. In the March 1915 issue, Anderson herself put forth an argument for gay rights, the first lesbian to do so in print. “With us,” she railed, “love is just as punishable as murder or robbery … because it is not expressed according to conventional morality.” After Heap joined as coeditor, the magazine published Hemingway’s first short stories and the first excerpts from Ulysses; poetry by T. S. Eliot, Gertrude Stein, and William Carlos Williams; art by Picasso and Brancusi, and essays by Ford Madox Ford and André Breton. Heap introduced a new motto: “To express the emotions of life is to live / To express the life of emotions is to make art.” The magazine’s uncompromising ethos was affirmed in September 1916, when an issue was released with thirteen blank pages as a “want ad.” Too few submissions had been judged worthy of publication, and they saw no point in laboring “to perpetuate the dull.”

The Little Review couldn’t pay its contributors and had a circulation of only a few thousand. Still, its reputation for artistic radicalism attracted high-profile collaborators. Amy Lowell, who in Anderson’s opinion “had more feminine whims and humors than ten women,” lobbied to be poetry editor. In a fit of pique after being snubbed by Ezra Pound, Lowell planned to show him “who’s who in this business” and offered to subsidize The Little Review with $150 a month. Anderson was not remotely tempted, despite living in virtual penury in order to pay for printing costs: “No clairvoyance was needed to know that Amy Lowell would dictate, uniquely and majestically, any adventure in which she had a part.” Instead, Anderson engaged Pound—who was at a safer distance in London—as European editor. He set out his terms in a letter: “I want an ‘official organ’ (vile phrase). I mean I want a place where I and T. S. Eliot can appear once a month (or once an ‘issue’) and where Joyce can appear when he likes, and where Wyndham Lewis can appear if he comes back from the war.”

Intent on making The Little Review an “international organ,” Anderson moved herself, a reluctant Heap, and the magazine to New York in early 1917. They found an apartment on West Sixteenth Street, above an undertaker and an exterminator. This unpropitious location was counterbalanced by the skillful decorative stamp the couple put on all their homes. While living in their California house, they had painted the furniture and fireplace to such pleasing effect that their landlord, the local sheriff, wanted to refund more than the deposit. In New York they covered the walls, painstakingly, with Chinese gold paper and hung a blue-covered divan from the ceiling with large black chains. Here they received would-be contributors, who were sometimes beseeching, sometimes antagonistic. “We were considered heartless, flippant, ruthless, devastating,” Anderson recalled. But, soon enough, “we would stand revealed as two simple sincere people with serious ideas.”

A story by Wyndham Lewis caused The Little Review’s first disastrous conflict with the censors. In “Cantleman’s Spring-Mate,” published in the May 1917 issue, a disaffected English soldier seduces a girl before going to fight in France. She writes to tell him she’s pregnant, but he ignores her letters with the same blank ruthlessness that allows him to kill Germans without flinching. The U.S. Post Office, deeming the story both obscene and anti-war, burned the four-thousand-copy print run. If other editors might have been cowed into cautiousness, Heap and Anderson were anything but fainthearted. When Pound sent the first chapter of James Joyce’s Ulysses, he warned it could cause trouble. They didn’t care: they knew it was a masterpiece. “We’ll print it,” Anderson declared, “if it’s the last effort of our lives.” The twenty-three-part serialization began in March 1918; over the next two years, four issues were confiscated and burned by the Post Office. As Anderson wrote in My Thirty Years’ War:

It was like a burning at the stake as far as I was concerned. The care we had taken to preserve Joyce’s text intact; the worry over the bills that accumulated when we had no advance funds; the technique I used on printer, bookbinder, paper houses—tears, prayers, hysterics or rages—to make them push ahead without a guarantee of money; the addressing, wrapping, stamping, mailing; the excitement of anticipating the world’s response to the literary masterpiece of our generation … and then a notice from the Post Office: BURNED.

In October 1920, Heap and Anderson were arrested and charged with distributing obscenity over “Nausicaa,” from the April 1920 issue. In this episode Leopold Bloom, his hand in his pocket, watches a young woman reclining on a beach. Thrilling to his gaze, she lets her skirt fall above her garter belt and he brings himself to orgasm. John Sumner, head of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, believed the text would corrupt young women, and he filed a formal complaint. At court for an initial hearing, Anderson and Heap appeared with their supporters, stylishly bohemian Greenwich Village women. The British poet-artist and Little Review contributor Mina Loy observed: “We looked too wholesome in Court representing filthy literature.” The magistrate ruled that the literature was indeed filthy, and the case was sent for trial. In the next issue of The Little Review, a defiant Heap pointed out:

Girls lean back everywhere, showing lace and silk stockings; wear low cut sleeveless gowns, breathless bathing suits; men think thoughts and have emotions about these things everywhere—seldom as delicately and imaginatively as Mr. Bloom—and no one is corrupted. Can merely reading about the thoughts he thinks corrupt a man when his thoughts do not? All power to the artist, but this is not his function.

In February 1921, at the Court of Special Sessions, three literary experts were called to testify in front of three judges that “Nausicaa” was art, not pornography. When the British novelist John Cowper Powys declared it a work of beauty that posed no threat to young girls, Heap restrained herself from saying that a young girl’s mind frightened her more than anyone’s. In one farcical moment, the prosecutor asked that the court hear some offending passages. A snoozing white-haired judge perked up, contemplated Anderson in her pearls and silk blouse, and forbade that obscenities be read out in her presence. Told she was the publisher, his honor said with paternal solicitude: “I am sure she didn’t know the significance of what she was publishing.”

Heap and Anderson were, nevertheless, found guilty under the Comstock Laws and each fined $50. Anderson regretted paying it; had she gone to jail, she reasoned, the publicity might have been greater. As it was, neither the New York Times nor any New York newspaper came to the women’s defense. It would be another thirteen years before Ulysses was legally published in the U.S. When critics began lauding it (while often misunderstanding it, Anderson thought), they typically neglected to cite The Little Review as the first publisher.

The Ulysses debacle strained Heap and Anderson’s already fraying relationship. For five years, they had been inseparable: moving from place to place, putting all their financial and emotional resources into The Little Review, and tolerating each other’s foibles. Anderson idolized Heap, but she was not an easy person to live with. Prone to dark depressions, she regularly threatened suicide. “The light is too brutal for me here,” she would say. “I am going back to the grave from which I came.” She kept a revolver in a trunk; Anderson lived in fear while feigning nonchalance. “I don’t know what poor human being first discovered the fact,” she later mused, “that the surest way to hold people’s interest is to subject them to torment.” She inflicted her own torments by dallying with other women. Heap was her one true love, she assured her. There was no need to be jealous. But to brooding, romantic Heap, casual infidelity was incomprehensible. “If I loved anyone as she says she loves me,” she lamented in a letter to a friend, “it would make me go into a long illness to be as free as she is now of me.”

Yet it was Anderson whose mental equilibrium, her preternatural ability to show no weakness, collapsed. She’d had enough of “publishing drudgery” and wanted to close The Little Review. “I argued that it had begun logically with the inarticulateness of a divine afflatus and should end logically with the epoch’s supreme articulation—Ulysses.” But Heap was determined to keep it going. She was also determined that their relationship continue unchanged, despite simmering acrimony and ebbing passion. Then, into this tense household, came Anderson’s young nephews, Fritz and Tom Peters. Her sister Lois had been hospitalized with a nervous breakdown, and the boys had nowhere else to go. Anderson, who didn’t have a maternal bone in her body, felt trapped in all directions and suffered her own nervous breakdown.

Anderson found happiness again in a new relationship, with the French soprano and actress Georgette Leblanc. They met through a mutual friend, the pianist Allen Tanner, and for both women it was love at first sight. Leblanc, who was eighteen years Anderson’s senior and reaching the end of a celebrated performing career, said: “There is something perfect in her soul.” Eager to begin a new chapter, Anderson at last renounced her Little Review responsibilities. Heap was, of course, hurt by this double defection. But she remained committed to the magazine, over which she assumed editorial control. She also set up the Little Review Gallery on East Eleventh Street, specializing in European Dadaists and surrealists such as André Masson, Hans Arp, Kurt Schwitters, and Hannah Höch. And while Anderson and Leblanc enjoyed a romantic idyll in a rustic New Jersey mansion, Heap adopted Fritz and Tom. Perhaps she wanted, even if subconsciously, a permanent tie to Anderson.

Their fates would remain entwined for another reason: a mutual and unending fascination with the doctrines of Gurdjieff. In this diminutive middle-aged esoterist with a shaved head and a black handlebar mustache, they saw, in Anderson’s words, “a messenger between two worlds … a seer, a prophet, a messiah?” In early 1924, the mystic visited New York on a promotional tour. That summer Anderson, Leblanc, Heap and the boys, and other friends all moved to France to study at Gurdjieff’s Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man in Fountainebleau, outside of Paris. A former Carmelite monastery set in forty-five acres of land, it housed around sixty men and women, who listened to talks, participated in sacred dances, and worked in the gardens and kitchens. The Modernist writer Katherine Mansfield spent her final days there, very happily. Just weeks before her death from tuberculosis in 1923, she wrote to her husband, the writer John Middleton Murry: “There is certainly no other spot on this whole planet where one can be taught as one is taught here.”

Gurdjieff hailed from the South Caucasus, part of the Russian Empire, where he was born to a Greek father and an Armenian mother. Around the turn of the twentieth century, he left home to travel the world, visiting monasteries, temples, and other holy places. The various spiritual disciplines he encountered were adapted into his cosmology, what he called The Fourth Way, The Work, or The System. Most people, he believed, exist in a state of “waking sleep,” their dormant souls trapped by their personalities and their lives buffeted by external forces. He taught that to uncover one’s authentic self, or “essence,” and gain free will, it is necessary to consciously, and with effort, observe the self and learn which of the three mechanical centers—physical, emotional, or mental—dominates. In no small part thanks to Heap and Anderson’s endorsement, these ideas spread through the interwar bohemia of New York and Paris. Kathryn Hulme remarked that while no one seemed to know Gurdjieff, “his reputation loomed in Left Bank conversations in a persistent hush-hush way.”

Gurdjieff found a true disciple in Heap, and over the subsequent years, she attained a high enough expertise in The System to teach it. Absorbed with this new purpose, she published the final issue of The Little Review in May 1929. Heap’s parting words in that issue were forceful: “Self-expression is not enough; experiment is not enough; the recording of special moments or cases is not enough. All of the arts have broken faith or lost connection with their origin and function.” The transcendence she had hungered for as a lonely little girl, wandering around the insane asylum, was no longer art’s sole dominion.

In 1935, Gurdjieff sent Heap to London to teach. She moved with her girlfriend, Elspeth Champcommunal, a fashion designer. Without a leader, the longstanding Paris study group was bereft. They decided to seek out Gurdjieff himself, and the group re-formed under his supervision. Its members grew to include Anderson, Leblanc, Solano (who also became Gurdjieff’s secretary), Hulme, her friend Alice Rohrer (a milliner from San Francisco), Louise Davidson, and Elizabeth Gordon—an unmarried Englishwoman and the only heterosexual, introduced into the group by Gurdjieff. He likened their “inner world journey” to a high mountain climb where they must be roped together for safety: hence they called themselves The Rope. They met daily, sometimes twice; anyone who sought to join them was curtly rebuffed. They shared meals, performing rituals around food and alcohol, all in the service of learning “how to act, rather than be acted upon.” The meetings went on for only about two years, but the women had formed what Hulme called an “exalted” lifelong bond: “Our work with Gurdjieff had created an inner-world intimacy, a kind of caring for the soul of another such as I had never experienced before in any human relationship.”

Heap and Anderson kept up a correspondence in the late thirties and during the war, when Anderson and Leblanc retreated to Le Cannet, north of Cannes in the unoccupied zone. In October 1941, Leblanc died of cancer, aged seventy-two. Sending her condolence, Heap wrote: “Georgette will never perish. Die all we must, but we can hope that none of us who has ‘eaten’ of Gurdjieff’s food will ever perish.” Heap settled permanently in London, living with Champcommunal in St John’s Wood and conducting Gurdjieff study groups until her death in 1964, at age eighty. Anderson died in 1973, aged eighty-six, and was buried next to Leblanc in Cannes.

In 1962 Anderson published The Unknowable Gurdjieff, a memoir of The Rope and Gurdjieff’s teachings. The book was dedicated to Heap. A fitting epitaph to these lives of peerless nonconformism is Anderson’s affronted reaction, in the late sixties, to questions about The Little Review’s selection process: “Mon Dieu, did I have any standards? I had nothing but…”

Emma Garman has written about books and culture for Lapham’s Quarterly Roundtable, Longreads, Newsweek, The Daily Beast, Salon, The Awl, Words without Borders, and other publications. She was the first writer of the Daily’s Feminize Your Canon column.

October 21, 2020

Five Films Enrique Vila-Matas Is Watching in Quarantine

PHOTO © OLIVIER ROLLER (DETAIL); MANUSCRIPT IMAGE COURTESY OF GALAXIA GUTENBERG

“The writing of Enrique Vila-Matas,” Adam Thirlwell writes in his introduction to the Art of Fiction interview in our current Fall issue, “is marked by a dazzling array of quotation, plagiarism, frames, self-plagiarism, digressions and meta-digressions: an intense and witty textual delirium that has made him one of the most original and celebrated writers in the Spanish language.” Vila-Matas has not only written in nearly every genre, blending fiction, essay, and biography into a single form, he is also the director of two short films, Todos los jóvenes tristes and Fin de verando, as well as a former film columnist for the magazine Fotogramas. We asked him to tell us what he has watched during these past few months of isolation.

Les Misérables

Malian-French director Ladj Ly realizes a tense and impressive X-ray analysis of a Paris banlieue weighed down by an infinite number of problems.

Uncut Gems

A fantastic film from the Safdie brothers (Benny and Josh, filmmakers with a grand future) that places us in the insanely fast-paced shoes of a Jewish jeweler in New York City.

Arrival

Based on Story of Your Life, a perfect novella by Ted Chiang, this film directed by Denis Villeneuve confirms that we ourselves are science fiction.

Roma

A poetic and subversive film from Mexican director Alfonso Cuarón brings us into the world of Cleo, a servant to a family in Mexico City’s Colonia Roma at the beginning of the seventies.

Bande à part

A marvelous Anna Karina, and a memorable film from the seventies that I have returned to once again to invigorate myself. The director, Jean-Luc Godard, described it as “Alice in Wonderland meets Kafka.”

Read our Art of Fiction interview with Enrique Vila-Matas in our Fall issue.

The Digital Face

As I was finishing my book Stranger Faces, a new app took social media by storm. It was called FaceApp and it allowed you to age your face, to see what you would look like at fifty or at eighty years old. I never downloaded it, but from the screenshots that appeared on my timeline, the versions of one’s face it spat forth seemed startlingly vivid, without falling on either side of the uncanny valley—neither too cartoonish nor too realistic. Within days, conspiracy theories cropped up. The company was Russian; the app was a cover; nobody was reading the terms and conditions; FaceApp was collecting faces. These fears may have been exaggerated, but they were not unfounded. The problem of the twenty-first century may well be the problem of the digital face.

It began with Facebook, founded in 2004 and named for the analog paper book that Harvard students used to identify one another, ostensibly to put together study groups, but actually for dating or, more likely, hooking up. The first version of the app, Facemash, was a “Hot or Not” ranking system for photos scanned from a set of online “face books” from different Harvard residential houses. This binary hot/not, yes/no model has continued to pervade the sociality of internet technology, from the thumbs up/thumbs down to the swipe left/swipe right.

Facebook’s relationship to the book has faded—the visual logic of photographs and videos has taken over the site—but its relationship to the face seems to have intensified. Over the last couple of years, users have reported being asked to “upload a photo of yourself that clearly shows your face,” purportedly to prove that you’re not a bot. Many suspect that there is, again, data harvesting afoot here, as facial recognition programs are being tested by companies like Google, Microsoft, and IBM. The worry is that this data will be used to surveil or target specific people. We have already seen facial recognition technology being used this way—in China, for example. News about the protests in Hong Kong that began in 2019 emphasized the various measures protestors are taking to prevent being identified—from scattering lasers to knocking down cameras.

Privacy concerns aside, the political problems with facial recognition abound. Your face can be used to “dox” you—to locate you and disseminate information about your address, your job, and your affiliations. Your face can be stored and run through programs that adjust its expressions and speech patterns—even for words you’ve never uttered. Perhaps worst of all, your face could be misidentified, especially if you don’t fit the data set on which these algorithms were built. Recent studies show that “when the person in the photo is a white man, the software is right 99 percent of the time. But the darker the skin, the more errors arise—up to nearly 35 percent for images of darker skinned women.” Facial recognition technology, for instance, can mistake black men for each other, black women for black men, and black people for gorillas. The power of the Ideal Face doesn’t just sway our cultural preconceptions; it actually sorts people into hierarchies enforceable by law and physical force. Police are already using facial recognition technology to identify suspects; U.S. security agencies are developing it for airports and borders.

What is most disconcerting about this perhaps inevitable slide toward a surveillance state based on the face is that we, the people, have chosen it. Self-selected identity has become state-sponsored identification. Your elective profile is now used to profile you. To a certain extent, none of this is new: consumer culture, popular culture, and high art have all historically co-opted our fusiform area to their advantage. Sex sells; faces sell. What interests me is how this reiteration of age-old tensions about the face—look at me/don’t look at me—changes once that face becomes digital currency. What sorts of play become available or precluded? Beyond political efforts to thwart it, how have we adapted, aesthetically, to facial profiling technology?

*

In one sense, responses to this technology, both positive and negative, have revolved around an old and familiar model of the Ideal Face: the idea that it represents identity, authenticity, transparency, truth. In an era of “fake news” and anonymous trolls, putting your face to your name and your words is seen as worthy, “say it to my face,” the ultimate rejoinder. But I find it fascinating, then, that this idea of the digital face—as proxy for a real face—has emerged at the same time as a panoply of technologies designed to take “playing with faces” to another level.

Apart from the emoji, which, as I’ve described, we prefer to keep opaque and love to stack and stagger, we now have the capacity to apply a whole range of filters to digital images of our own faces. You can add or remove hair or makeup; you can change gender; you can layer your face with animal features, both realistic and cartoonish; you can merge your face with another person’s; and most popular on the FaceApp, you can time travel by aging yourself.

Jia Tolentino argues that we are now in the Age of Instagram Face, a cyborgian amalgam forged by social media, plastic surgery, and the app FaceTune:

It’s a young face, of course, with poreless skin and plump, high cheekbones. It has catlike eyes and long, cartoonish lashes; it has a small, neat nose and full, lush lips. It looks at you coyly but blankly, as if its owner has taken half a Klonopin and is considering asking you for a private-jet ride to Coachella. The face is distinctly white but ambiguously ethnic—it suggests a National Geographic composite illustrating what Americans will look like in 2050 … “It’s like a sexy … baby … tiger,” Cara Craig, a high-end New York colorist, observed to me recently. The celebrity makeup artist Colby Smith told me, “It’s Instagram Face, duh. It’s like an unrealistic sculpture. Volume on volume. A face that looks like it’s made out of clay.”

This face might seem to be the contemporary reductio ad absurdum of the Ideal Face. But the shadows of stranger faces lurk here, in the Instagram Face’s figural hybridity, racial ambiguity, clay-like sculptural thingness, animal features, blank sublimity, eerie layeredness, and, of course, in its origin point and favored playground: the internet.

Some of these new face technologies handily work to mask or disguise the face—people use them to protect themselves from being identified by the state or by employers. Others seem suited to certain changes in how we engage with celebrity culture. But for the most part, they simply represent the apotheosis of my overarching claim in Stranger Faces: we love to play with faces, to make them into art.

The digital face that I find the most interesting in this regard is the GIF. The Graphics Interchange Format was invented in 1987. While it originated as an image format with a set of shifting colors in a palette, we mostly think of it now as a brief, looping clip of film or animation. It is a matter of some debate how to pronounce the acronym GIF—its inventors lean toward a soft g like the peanut butter brand Jif, but lay users seem to prefer a hard g. The oscillation between the two seems fitting for this oscillatory form. Apps like Vine and TikTok have advanced and perpetuated its use, but its natural habitat is on social media: Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

The standard GIF usually depicts a human face in motion: whether turning toward or away from the “camera,” changing expression, shifting very slightly, or erupting—into a smile, into laughter, with a spit-take. These so-called reaction GIFs often accompany or are accompanied by text; they supplement a post or are captioned with language. They can feel like punctuation or ejaculation—an exclamation point, a question mark, the “snigger point” that Ambrose Bierce proposed or the “special typographical sign for a smile” that Vladimir Nabokov suggested.

Unlike the emoticons or emoji that emerged to fulfill those needs, a poster tends to use one GIF at a time, rather than stacking them up. The GIF does lend itself to a long, dialogic conversation, however. You’ll find on Twitter entire threads made up of GIFs, some echoing each other, others offering opposed or qualifying reactions (“more like____”). Without the original post to which they are reacting, these alternating flickers of emotion can feel redundant or baffling. A GIF isn’t more efficient than language. Indeed GIFs often induce flurries of interpretation or questions about whose face it is, or how and where it can be found.

To me, more than the emoji, more than even a filtered image of your own face, the GIF represents the furthest thing from the Ideal Face. The GIF isn’t singular but plural, a kind of language, yet much less fixed than the alphabet of emoji for which additions must be petitioned. It is rarely a frontal view and is often in motion, distorted, exaggerated, sometimes animalistic. You do not address the face of the GIF, because rarely does a person use a GIF of their own face. Rather, it serves as a temporary mask, a momentary avatar for the person who posts it, who can be of a different race, ethnicity, class, gender, and ability entirely. And yet it is an encounter, a daily aesthetic experience that compels repeated watching—not just in the iterative instance of the click, but in any popular GIF’s continued distribution and longevity as a recognizable meme over time. It is a supremely pleasurable form of face play.

*

The supposed glow, transparency, and distance from animality in the Ideal Face connote racial whiteness. In this, too, the GIF is its polar opposite. Sianne Ngai argues that “exaggerated emotional expressiveness” can “function as a marker of racial or ethnic otherness in general.” As Lauren Michele Jackson notes in an article on “digital blackface,” this manifests in a particularly gendered way for GIFs:

[Internet GIF search engine] Giphy offers several additional suggestions, such as “Sassy Black Lady,” “Angry Black Lady,” and “Black Fat Lady” to assist users in narrowing down their search. While on Giphy, for one, none of these keywords turns up exclusively black women in the results, the pairings offer a peek into user expectations. For while reaction GIFs can and do [evoke] every feeling under the sun, white and nonblack users seem to especially prefer GIFs with black people when it comes to emitting their most exaggerated emotions. Extreme joy, annoyance, anger and occasions for drama and gossip are a magnet for images of black people, especially black femmes.

Black femmes tend not only to carry the weight of emotional labor online, but also to serve as the vents for the expression of emotions, from happiness to sadness and everything in between. To signify affect isn’t necessarily to command respect or earn capital. And as Jackson explains, this trend follows uncomfortably from a long history of blackface in America—its appropriative violence and perpetuation of stereotypes.

But despite this troubling history, let us not dismiss the cultural dominance of the black femme face. A vast flock of black femme faces flutters across the field of the internet: GIFs of The Real Housewives of Atlanta, Whitney Houston, Mariah Carey, RuPaul, Angela Bassett, Naomi Campbell, Viola Davis, Rihanna, Beyoncé, Keke Palmer. And of course, the black woman with the greatest affective range, plasticity, nuance, and exposure to her face—and the longest history of taking on American affective burdens—is Oprah Winfrey. Oprah turns and opens her hands (“what did I tell you?”); Oprah leans back into someone, the barest flinch reflecting her pleasure in what she’s watching; Oprah spreads her arms, her yelling mouth wide with joy; Oprah dabs her eyes with white tissue; Oprah looks skeptical—a narrowed eye, a blink, a frown. Oprah is our reigning queen of the GIF.

My ham-handed descriptions of these GIFs are more mnemonic, more generic than their actual use, which is quite various and as subject to the play of irony—both dramatic and semantic—as that of any language. The GIF’s relationship to an actual person is attenuated, if not irrelevant: people become known as Blinking GIF Guy, or And I Oop Girl. Add filmic effects—a rapid zoom in, a shuddering blur, a visual distortion—and these strange faces become stranger indeed.

One of my favorite GIFs—I had to do an internet search to replicate it below but I chose not to hunt for its biographical origin, which seems beside the point—is of a black woman with her eyes rolling back in ecstasy:

Omg Melt GIF from Omg GIFs

At some point, someone—again, I don’t know who—elected to add a trippy filter to it to intensify the intended effect, which is, per the GIF’s name, “Omg Wow Yes.” This is a twenty-first century Impressionist portrait, continuously looping from two to three dimensions.

This woman’s beauty; her race, gender, class, or ability; her availability for a face-to-face interaction; her relationship to me and to the world; the time between now and whenever this clip was recorded, made into a GIF, and distorted for emphasis—none of this really matters to the effect of my encounter with it. Though I’ve never actively used this GIF as a reaction online, I see this woman’s face all the time—a one-way gaze, as I doubt she’s seen mine. This face isn’t a mirror of my soul or a window into hers. It’s a face set in motion by the force of a specific feeling, a specific moment—a punctum. It will never perfectly map onto whatever I’m feeling, nor does it pretend to. Rather it resonates with me, reverberates with an affective intensity set free from its bodily source. This strange, stranger’s face can’t be profiled or co-opted—not even by its original bearer, whom it just happened to flutter over, ripple through, with a deep and unaccountable pleasure.

Namwali Serpell is a Zambian writer and professor of English at Harvard University. She’s a recipient of a 2020 Windham-Campbell Prize for fiction and the 2015 Caine Prize for African Writing. Her first novel, The Old Drift (Hogarth, 2019), won the 2020 Anisfield-Wolf Book Award for fiction, the 2020 Arthur C. Clarke Award for science fiction, and the Los Angeles Times’s 2020 Art Seidenbaum Award for First Fiction, and was named a New York Times Notable Book of 2019.

Excerpted from Stranger Faces . Used with the permission of the publisher, Transit Books. Copyright © 2020 by Namwali Serpell.

October 20, 2020

Death’s Traffic Light Blinks Red

Choi Seungja. Photo: Sinyong Kim. Courtesy of Action Books.

Choi Seungja is one of the most influential feminist poets in South Korea. Born in 1952, Choi emerged as a poet during the eighties, a turbulent and violent decade that saw nationwide democracy movements against the authoritarian government. During that era, South Korean poets were predominantly populist, writing “people’s poetry” that protested authoritarian rule. These poets were also mostly men. But during that time, a new wave of feminist poets emerged, such as Kim Hyesoon, Ko Jung-hee, Kim Seung-hee, and Choi herself. When Choi first started publishing in 1979, her provocative poetry was dismissed by the male literary establishment who expected women to write quiet, domestic poems. As the translator and poet Don Mee Choi writes in the anthology Anxiety of Words, Choi’s language and content were “attacked for being too rough and vulgar for a female poet.”

Born in the small rural town of Yeonki, Choi Seungja attended Korea University, devoting her studies to German literature, and afterward made a living as a translator of German- and English-language books. In 1979, she was the first woman poet to publish in the prestigious journal Literature and Intellect. Despite her growing success as a poet over the following decades, Choi mostly lived alone in near poverty. In 2001, she experienced a mental illness that kept her in and out of hospitals. A community of poets came to her financial aid; the poet Kim Hyesoon, for instance, collected money each month to support Choi, and the press Munhakdongne gave her a writing space in their office so she had a place to write and translate.

Choi’s stripped-down poetry is breathtaking and frightening. Her poems are uncompromising because she will stare into the infinite dark tunnel of her solitude and not break that stare. She writes, with terrifying alacrity, the existential despair of living in a hierarchical society where free will is a joke. While it has been changing, South Korea was a paternalistic and Confucian society, where the individual was subsumed by their family unit, especially for a woman, whose worth was measured by her husband and children. When a woman marries, her name is no longer used. She is called “so-and-so’s wife” or “so-and-so’s mother.” Because Choi was a single woman, she was an aberration. The I in her poems is often abjectly alone. The phone in her home is so silent day after day that when it finally rings, she is frightened. Instead of the timeline of a traditional Korean woman who measures her milestones by marriage and children, she has only death to shadow her as she ages. In her poem “Thirty Years Old,” Choi writes, “Death’s traffic light blinks red / in my two eye sockets / my blood is jelly, my fingernails sawdust, / and my hair wire.” In the poem “Already I,” Choi contends:

Already I was nothing:

mold formed on stale bread,

trail of piss stains on the wall,

a maggot-covered corpse

a thousand years old.

Nobody raised me.

I was nothing from the beginning,

sleeping in a rat’s hole,

nibbling on the flea’s liver,

dying absentmindedly. in any old place.

So don’t say you know me

when we cross paths

like falling stars.

Idon’tknowyou, Idon’tknowyou,

You, thou, there, Happiness,

You, thou, there, Love.

That I am alive

is no more than an endless

rumor.

Metonyms of the body as waste pervade her poetry: the piss, shit, and vomit that the body rejects and that we recoil from because the emissions remind us of our own mortality. The barren womb is also a central motif, evoking the disgrace she feels as a childless woman in a society where a woman is the sum of her children. It is also a metaphor of the motherland whose soul has become corrupted by capitalism. Capitalism has become the only logic that rules her nation, where all human relationships are mediated by money. The citizen does not act but is acted upon. In the poem “The Portrait of Mr. Pon Kagya,” the salaryman Mr. Pon Kagya does not sit on the chair but the chair sits on him; the pen grips him; the pay envelope thrusts him in his pocket. Objects have become subjects who have their way with this salaryman, who is powerless. While Choi’s poems may be despairing, they are simultaneously liberating because she writes in a language both ruthlessly direct and strangely surreal. She does not obfuscate her despair with elegant metaphors but confronts it with nightmarishly strange imagery. In her brutal investigation of her own pain and agony, she cries out for an alternate way of life.

Choi took a hiatus from poetry in 2001 because of her mental illness, but her reputation as a formidable poet in South Korea has only grown. She has published eight books of poetry: Love in This Age (1981), A Happy Diary (1984), The House of Memory (1989), My Grave Is Green (1993), Lovers (1999), Alone and Away (2010), Written on the Water (2011), and Empty Like an Empty Boat (2016). Choi has also translated many books into Korean, including Friedrich Nietzsche’s Thus Spake Zarathustra, Max Picard’s The World of Silence, Paul Auster’s The Art of Hunger, and Erich Fromm’s The Art of Being. In 1994 she participated in the International Writing Program at the University of Iowa. She has received the Daesan Literary Award (2010) and Jirisan Literary Award (2010) and is now regarded as one of the most important poets in Korea.

Cathy Park Hong is the author of the essay collection Minor Feelings, as well as three books of poems, most recently Engine Empire. She is the poetry editor of The New Republic.

From Cathy Park Hong’s preface to Phone Bells Keep Ringing for Me , by Choi Seungja, translated from the Korean by Won-Chung Kim and Cathy Park Hong. © Action Books, 2020.

Redux: Sightseer in Oblivion

Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

Truman Capote, 1957. Sketch: Rosalie Seidler.

This week at The Paris Review, no one wants to get out of bed. Read on for Truman Capote’s Art of Fiction interview, Shruti Swamy’s short story “A House Is a Body,” and Thomas Lux’s poem “Sleepmask Dithyrambic.”

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, and poems, why not subscribe to The Paris Review? Or, to celebrate the students and teachers in your life, why not gift our special subscription deal featuring a copy of Writers at Work around the World for 50% off? And for as long as we’re flattening the curve, The Paris Review will be sending out a new weekly newsletter, The Art of Distance, featuring unlocked archival selections, dispatches from the Daily, and efforts from our peer organizations. Read the latest edition here, and then sign up for more.

Truman Capote, The Art of Fiction No. 17

Issue no. 16, Spring–Summer 1957