The Paris Review's Blog, page 138

November 16, 2020

The Art of Distance No. 34

In March, The Paris Review launched The Art of Distance, a newsletter highlighting unlocked archive pieces that resonate with the staff of the magazine, quarantine-appropriate writing on the Daily, resources from our peer organizations, and more. Read Emily Nemens’s introductory letter here, and find the latest unlocked archive selections below.

“We’re heading toward winter, which in the book world means prize season is upon us. There won’t be banquets and after-parties this year, but these awards do afford book lovers the opportunity to look back on something other than politics and COVID—and to reflect on books that have helped us understand and weather this tumultuous era. This past week, Souvankham Thammavongsa was named the winner of the Scotiabank Giller Prize, which celebrates the best of English-language Canadian fiction. Among its past winners are many who, like Thammavongsa, have graced the pages of The Paris Review. This week’s The Art of Distance joins in the celebration by unlocking interviews with and stories by Giller honorees as well as other notable Canadian writers. Happy reading, and stay safe.” —Craig Morgan Teicher, Digital Director

Mavis Gallant. Photo courtesy of Mavis Gallant.

Mavis Gallant, who spent much of her life in France, was very much a world citizen. But when asked about her home in the Art of Fiction no. 160, she said, “I am a writer and, of course, a Canadian.” There’s much more here about writing and traveling and the tether that binds an artist to a place.

This year’s Giller winner is How to Pronounce Knife, the debut story collection by Souvankham Thammavongsa, whose work delves deep into the immigrant experience. Her story “The Gas Station,” which appears in the book, was first published in the Spring 2019 issue.

The Nobel laureate Alice Munro has won the Giller twice, most recently in 2004, for Runaway. In the Art of Fiction no. 137, Munro explains that ideas for her stories are almost overabundant: “I never have a problem with finding material. I wait for it to turn up, and it always turns up.” Although the Review didn’t publish anything from Munro’s two Giller-winning collections, her story “Spaceships Have Landed” appeared in the Summer 1994 issue.

The Haitian-born, Montreal-based writer Dany Laferrière speaks in the Art of Fiction no. 237 about how politics has been threaded through his sense of the world from an early age and how political concerns have never been separate from his writing: “Politics are pivotal to all of us, especially those who spend their childhood under a dictatorship. My childhood had a lot to do with dictatorship, with power, with the effects of power on myself.”

Margaret Atwood’s novel Alias Grace was the 1996 Giller winner. A few years earlier, in the Art of Fiction no. 121, the ever-adventurous writer said that “every novel is—at the beginning—the same opening of a door onto a completely unknown space.” After you’ve read the interview, feel free to explore Atwood’s story “Bodily Harm,” which was first published in the Fall 1981 issue.

Sign up here to receive a fresh installment of The Art of Distance in your inbox every Monday .

To Be an Infiltrator

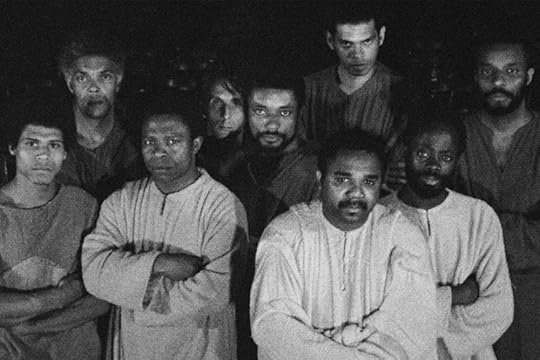

“Untitled”, 1988 by Felix Gonzalez-Torres, framed photostat, 10 1/4 x 13 inches. Published in Photostats, Siglio, 2020. Copyright Felix Gonzalez-Torres. Courtesy Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation.

Time the substantial we, / epochal and great, as only we can see it, our particular.

—Alice Notley

No one wants to be defined by history’s contingencies, by catastrophe, but attempting to ignore how they shape us would be as ludicrous as trying to stop the clock. What if instead we broke down the chain of events leading to them, undoing their fatal sequence and leaving their parts open for reassembly? Is this what’s at stake in Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s photostat works? In the book Photostats, they appear as coded messages awaiting decipherment, but they’re equally apt on gallery walls as reminders that no matter how open or walled-off any space may be, it escapes neither interconnectedness nor time’s inexorable march.

Unlike the stars, we do not write, luminously, on a dark field (Mallarmé). Yet Gonzalez-Torres’s inscriptions do act as constellations, as celestial alphabet. Events worth remembering, the count of years—they are light beams orienting us as we go on forgetting. Each cluster of dates and references displays its own oblique associative logic. The larger narrative it may or may not point to can be searingly legible or obscure to varying degrees. Regardless, those gaps between elements in each of the clusters are openings inviting us to fill in the blanks by bringing in our own associations, personal histories, and biases.

I took apart dates and historical events and remembered or discovered what occurred then that might have had a bearing on him. Let’s not forget he was a transplant, a politically minded one, who identified specifically as American but was born in Cuba and raised in Puerto Rico: two places with a complex relationship to the U.S. I wonder with whom in the art world he would’ve spoken in Spanish and how his conversations would’ve taken shape according to what he’d say in one language and not the other. Did he think of this? Am I projecting? He carefully avoided labels.

Apropos of not making art about being gay, Gonzalez-Torres said to Ross Bleckner in a BOMB interview that his work was about love and infiltration. “It’s beautiful; people get into it. But then, the title or something, if you look really closely at the work, gives out that it’s something else.” To look closely at Gonzalez-Torres’s photostats involves taking a deep dive into history’s ash heap, getting lost in the process, knowing there’s no one way to read the works. Oddly rhyming shards emerge, resonant shards that seem to prove the existence of a universe in which the future’s already happened.

*

Lest Chile become “another Cuba,” the Nixon administration encourages a military coup against the democratically elected Salvador Allende in the early seventies. Weeks after Allende’s overthrow in 1973, the Weather Underground bombs the ITT Corporation’s offices in New York and Rome for its involvement in the coup. In 1974 Hans Haacke makes an artwork exposing the Guggenheim Museum’s trustees’ ties to the Kennecott Copper Corporation and its attempts to undermine Chile’s economy after Allende’s regime expropriated its mines. In 1975, a killer shark in a film symbolizes a miscellany of sociopolitical anxieties. A Gonzalez-Torres exhibition opens at the Guggenheim in 1995.

*

In 1983, Bowie asks an MTV host: “I’m just floored by the fact that there are so few black artists being featured … Why is that?” One of 285 music videos featured that year is in Spanish: the Italian disco duo Righeira’s “No tengo dinero.” In 1985, the Organization of Volunteers for the Puerto Rican Revolution claims responsibility for shooting a U.S. Army recruiting officer: “Yankee jails are becoming filled with … our patriots; … prepare your cemeteries because we’re going to fill them with your mercenaries.” In 1987, Harvard University is awarded the first new-life-form patent for the cancer-prone, transgenic OncoMouse.

*

In 1975, Cambodia’s new leadership embarks on a gruesome path toward self-reliance and “clearing the country of the filth and garbage left behind by the war of aggression of the US imperialists and their lackeys.” In 1968, the U.S. Embassy is attacked in Rio. Student uprisings against autocratic regimes, and the sentiment leading Peruvian students to shower Vice President Nixon with garbage while on a goodwill tour a decade earlier, sweep across Latin America. In the 1987 Robocop, a cyborg is developed after a self-sufficient robot designed for Detroit’s urban pacification kills a trustee of the very corporation that created it.

*

There’s a video by Felix Gonzalez-Torres made in 1979, the year he arrived in the U.S. and portable music was born. Shirtless, he speaks to the camera in Spanish while writing on a blackboard. He remembers being put on a plane to Spain with his sister as a child. Remembers priests and not remembering his mother. He goes on half-remembering an upsetting story in which memories and stories are traps tangling him up, always the same old memories and stories tangling him up. He points to the blackboard: “See, that’s you in the middle of that jumble, all tangled up.”

*

In Bowers v. Hardwick (1986), the Supreme Court upholds Georgia’s sodomy laws criminalizing oral and anal sex between consenting adults. A public drinking citation outside Hardwick’s workplace, a gay bar in Atlanta, had turned into an arrest warrant allowing a police officer to walk into the defendant’s home and discover him engaging in oral sex with his male partner. Justice Blackmun’s dissenting opinion—one of two—is written by the openly gay clerk Pamela S. Karlan. Testifying during Trump’s impeachment trial in 2019, she would quip, “The president can name his son Barron, but he can’t make him a baron.”

*

“Untitled” (1988), 1988 by Felix Gonzalez-Torres, framed photostat, 10 1/4 x 13 inches. Published in Photostats, Siglio, 2020. Copyright Felix Gonzalez-Torres. Courtesy Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation.

At a televised press conference in 1977, the anti-gay crusader and once beauty queen Anita Bryant prays that the man who just put a pie in her face “be delivered from his deviant lifestyle.” “We can’t stand the garbage you spout,” he shouts back. The FDA licenses the first blood test for AIDS in 1985. Rock Hudson, the first celebrity to publicize his diagnosis, dies of AIDS-related illness that year. A 1949 screen test had catapulted him to stardom: “ … for thirty days and nights, we took a steady beating. More than half my platoon were killed. I never expected to come out alive.”

*

In 1952, Fulgencio Batista stages a military coup in Cuba. Recklessly corrupt, he is backed by the Eisenhower administration while the public’s discontent, which will eventually lead Fidel Castro to overthrow him, keeps mounting. The American mobster Meyer Lansky, a.k.a. the “Mob’s Accountant,” has full control of Cuba’s gambling casinos then. Batista dies in 1973, and so does Bruce Lee. Lee’s poem “The Silent Flute” was the basis of a screenplay for an eponymous film. An excerpt reads: “Now I see that I will never find the light / Unless, like the candle, I am my own fuel, / Consuming myself.”

*

Patient Zero (originally O for “out-of-California”) contracted what was considered a rare cancer in 1981. I write these words during the coronavirus pandemic. The irony of stating this isn’t lost on me; only the readers of an inconceivable future would need to be reminded that the world as we’d known it came to a halt in 2020. In various Classical texts, Pandêmos—the common to all people—serves as Eros and Aphrodite’s surname and is synonymous with sensual love. It is only just, Gonzalez-Torres’s abiding demand that we partake of a radical poiesis at the intersection of love and the public.

*

In a seventies Dick Tracy–style commercial, an orange Tic Tac’s flavor “fizzes in a rumba” on the detective’s tongue. When the American market begins calorie-counting later on, cunning replaces wit: Tic Tacs, which helped consumers “get a kick out of life” now become the “one-and-a-half calorie breath mint.” In a 1972 Monty Python sketch, Spam—ubiquitous in the UK during wartime—is undesirable no matter how it’s spun. Unsolicited email advertising is named after the sketch. The first deliberate spam for a network’s users to read is posted in 1994. Its subject: “Global Alert for All: Jesus is Coming Soon.”

*

Attorney General William Barr sends two thousand military troops to quell riots following the 1992 acquittal of the LAPD officers who’d battered Rodney King: “We’re not going to tolerate any of this stuff out in the streets.” During the 1965 Watts Riots, fourteen thousand troops descended on Los Angeles. The Insurrection Act—conceived as protection “against hostile incursions of the Indians”—is invoked again in 2020. Trump summons the National Guard to control protests after George Floyd’s murder. Immediately following, Attorney General Barr accompanies him to St. John’s Church for a photo op. Heard again throughout American cities: “No Justice, No Peace!”

*

“Untitled,” 1988 by Felix Gonzalez-Torres, framed photostat, 8 1/4 x 10 1/4 inches. Published in Photostats, Siglio, 2020. Copyright Felix Gonzalez-Torres. Courtesy Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation.

The 1988 action thriller The Dead Pool is the final installment of the Dirty Harry series, in which Clint Eastwood, a pro-gun self-declared libertarian, plays a maverick inspector. “You forgot your fortune cookie; it says you’re shit out of luck,” he snaps, as he pulls out a Smith & Wesson Model 29 to shoot a robber at a Chinese restaurant. During the American Civil War, Smith & Wesson became the most popular revolvers among soldiers of both sides using them for self-defense. During the 2012 Republican National Convention, Eastwood improvised a cringe-worthy pro-Romney speech while speaking to an empty chair.

*

In defiance of the Civil Rights Act, Alabama’s electors refuse to pledge votes to Lyndon B. Johnson in 1964, and the state’s presidential election ballot has no Democratic contender. In the fifties, when gentrification causes artists and poets to move eastward from Greenwich Village, the area once known as Little Germany that later became home to Eastern European immigrants is rebranded as the East Village. On Third Avenue and Fourteenth Street, where the Five Napkin Burger chain now thrives, there once stood, in the mid-’80s, the twenty-four-hour coffee shop Disco Donut. Above it was the lesbian bar Carmelita’s Reception House.

*

William James: “Many things come to be thought by us as past, not because of any intrinsic quality of their own, but rather because they are associated with other things which for us signify pastness … What is the original of our experience of pastness, from whence we get the meaning of the term?” car market crash smash hit big bang sudden great drop depression catastrophe collision black monday speculative dotcom bubble bankruptcy chapters steep revenue cling-clang loss economic stars recession collide crisis crack epidemic break dance financial thump-thump panic boom box bounce back behavior immunity herd cats …

Mónica de la Torre works with and between languages. Her poetry books include Repetition Nineteen (Nightboat Books, 2020) and The Happy End/All Welcome (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2017). She is the coeditor of the anthology Women in Concrete Poetry 1959–79 (Primary Information, 2020). A contributing editor to BOMB, de la Torre has also written for Artforum, Granta, and The Believer. She teaches poetry at Brooklyn College and is on the faculty of the Bard M.F.A.

Excerpted from Photostats , by Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Siglio, 2020.

November 13, 2020

What Our Contributors Are Reading This Fall

Contributors from our Fall issue share their favorite recent finds.

Tourmaline (Photo: Mickaline Thomas)

A few months ago, this essay on freedom dreaming, by Tourmaline, found me when I needed it. The whole thing is a wave of beauty. When I first read it, I thought: I see that world. I want that world. But I more than want the world it describes; I need it. Fast forward. The Nigerian government—using its police force and army—turned a peaceful protest against police brutality into the widely reported massacre we are still recovering from. Ten days after, I read this essay about abolition by Mariame Kaba. With my mind still raw from footage of live rounds ripping through the air as people screamed and then fell quiet, I was too scared and exhausted to dream that day.

But these two essays remind me of the same things: We can have more than what we have always known. We can imagine beyond everything we have ever seen. We deserve more than make-do, more than empty promises of reform. We owe the dreaming to ourselves and to each other. If the first thing about revolution is creation, as Kwame Ture stated, then our ability to create newness, to make the immaterial tangible is crucially linked to our freedom. It looks different often, but I am trying to do the daily work of ensuring that nothing—including my own rage and grief—destroys the place where my imagination is stored. —Eloghosa Osunde

Rachel Eliza Griffiths.

At a time of so much loss, what could be more necessary than an elegy turned affirmation of identity? If an elegy usually focuses on the dead, Seeing the Body, Rachel Eliza Griffiths’s latest collection of poems written after the loss of her mother, directs the elegy back toward the living self. The opening title poem asks “How does the elegy believe me?” The pulse of the book is a series of unlabeled photographs, which make up the middle section Daughter: Lyric: Landscape. In a white dress set against majestic rocks or folded nude into furniture, the poet figures herself as both ghost and geological element. Loss strips the self but it also distills the spirit. Elegy becomes self-portrait.

In a country afflicted with such a deep and ongoing history of systemic racism and racial violence, death and grief are defining aspects of Griffiths’s life and identity as a Black woman. Toward the end of the collection, “Good America, Good Acts,” a poem for Chikesia Clemons, a young mother and victim of police brutality, ends with these powerful, punishing words: “Yes, / America, you’ve done just about enough.” The book is as much a political lament as it is a personal memorial. In poems ranging formally from quick rivulets to dense meditations, there is no distinction between monumental loss and the body as monument (“Now we meet in my body… ”). Griffiths draws our attention past absence to the mirror processes of dying and grieving, both embodied (“A grief makes its own blood”).

Griffiths reconsiders her own birth and her mother’s birth (while filling out her death certificate), and in one of the most powerful poems, she depicts her own rebirth as the labor and delivery of language: “Examine the fontanelles / of syllables, pressing / & striking / the echoes of her voice / until I scream & shriek / inside the lonely gauze / of my rebirth.” The impulse of poetry is physical. Both the poems and photographs function as illuminating fragments of the poet and her mother (“We break mirrors inside of each other / to see again.”). The distance of death is shattered by exquisite intimacy. Alive with pain, rage, and desire, this kind of grief has knuckles. As someone for whom grief and motherhood are inextricable, I am invigorated by Griffiths’s vision in Seeing the Body. Beyond memory and ritual, we have the power to incorporate our dead. —Elizabeth Metzger

I couldn’t have wished for better reading during the pandemic than a new manuscript by Maureen Gibbon. I was transported from our insane world into that of Manet during his last years. Delving into a story about the great painter’s syphilis managed to distract me from the pandemic. I decided to reread Gibbon’s first novel, Swimming Sweet Arrow, an all-time favorite, which I first read when it came out in 2000. The novel is sharp, deep, and direct. I’d never before read a woman’s coming-of-age, both sexually and emotionally, told in such a straightforward, unpretentious manner. Gibbon, with reverence but without sentimentality, presents us with the life of a working-class girl as she learns about drugs, sex, and men. The opening of the novel is one of the best first sentences ever:

When I was eighteen, I went parking with my boyfriend Del, my best friend June, and her boyfriend Ray. What I mean is that June fucked Ray and I fucked Del in the same car, at the same time.

I think Maureen Gibbon is criminally underrated. She’s able to create worlds where someone else’s everyday becomes my own. —Rabih Alameddine

Jack Dylan Grazer and Jordan Kristine Seamón in We Are Who We Are. Photo: Yannis Drakoulidis / HBO.

For the last eight weeks, I’ve been awash in Luca Guadagnino’s sublime We Are Who We Are. The cultural reframing of American families transplanted to a military base in Italy becomes, in Guadagnino’s hands, a study of a cross section of U.S. citizens suddenly forced to externalize “American values.” Against this backdrop, Guadagnino trains his lens on the emotional lives of teenage children, exploring their protean desires, rage, melancholy, and their emerging and still amorphous sexual identities. Guadagnino’s range and insight reels in the subtle tonal shifts of the interstitial as well as in the high points of raw Dionysian energy. He displaces and upturns most of our visual expectations for the interior lives of the young. His gaze is both tender and unrelenting, picking apart complex relationships and the multiple ways they manifest across the jagged spectrum of eros. I recognize something similar in the lush tonality of American artist Jesse Mockrin’s work. Mockrin re-creates key details from paintings of the Rococo and Baroque eras to depict the cycling of myth and narratives through time. Her paintings transform and invert the expected horror vacui of the images from these periods by using elision, where the subjects fall out of the frame. This in turn highlights the energeia of the minutiae—the central act and the hands that guide the act. The negative space in her paintings is compounded and given a potent psychic charge by this sense of disorientation brought about by what is left outside the frame. —Rohan Chhetri

Sufjan Stevens. Photo courtesy of Asthmatic Kitty Records.

I’ve long been a Sufjan Stevens fan. The second album I bought was Seven Swans. The tone and lyrics on that collection brought me fully up to speed on Stevens’s unironic use of Christian allusion, story, and dogma. Wait—a highly gifted singer-songwriter who was plainly a believer, but not part of Christian rock? How can this possibly be?

As soon as it was available, I got Stevens’s newest album, The Ascension. It is what I think is called electropop, and it has the catchy hooks and the highly processed synth sounds one might expect from such a category. I am not finished listening, but at this point I can say that even though I don’t respond strongly to every cut on the album, the many I do respond to represent an advance. The album is a passionate reexamination of Stevens’s faith, one that includes the doubt that is part of any fully aware Christian’s journey. The strategy brings to mind the Songs of Solomon (as well as literature, such as Kabir and Rumi, from other traditions) in their blurring of the borders between eros and theos. There is also a kind of Old Testament exhortation to the lyrics—Stevens does not shy from complaining, vehemently, to God about His hiddenness, His apparent lack of presence, particularly in our current historical moment.

Some songs gloss Stevens’s frustration at being either reviled or deified for his faith: “I don’t wanna be your personal Jesus / I don’t wanna live inside of that flame.” And it may be that my recommendation also leans too heavily on the religious angle. I assure you, the album continues and extends Stevens’s musical explorations. His sound is, as always, eccentric, melodic, and unique. But the most subversive and idiosyncratic element in The Ascension, as in all Stevens’s work, is his faith. And I am most grateful for that. —Jeffrey Skinner

One of the most transformative literary experiences of my past few months has been a podcast called Literature and History, which is written, researched, performed, sound-engineered, and everything-elsed by one incredibly talented guy, Doug Metzger. It was first introduced to me by my partner, Steve Potter, who’s also a writer; he stumbled across it after we’d been longing for a survey course that could orient us to all the literature we’d half-forgotten or that we wish we’d read. In Literature and History, Metzger led us on a comprehensive and generous march through Anglophone literature’s lineage of influence—not just the white-washed Greek and Roman classics, but a very intentional widening of the canon that includes work once influential to English-language traditions but is rarely studied now, like Mesopotamia’s creation epic and the lower-class folktales of Ancient Egypt. Metzger focuses on one piece or genre of literature at a time, and he offers a lyrical and moving summary before moving on to historical context, discussing everything from how the work was received at its making and how it has been received over time, to its influence on later writing, to what we find problematic with it in a modern context. Metzger is a careful and thoughtful reader and historian, and over the many, many hours I’ve now spent with this podcast, I’ve learned to really trust the deft way he incorporates gender, race, class, and time into the discussion. Besides being very informative, Literature and History is also unabashedly punny and delightful to listen to; I once spit out lukewarm mocha in the car when Metzger referred to Olympic wrestlers in Hesiod’s time as “well-oiled—or maybe we should just say well Greeced.” I was initially skeptical about the episodes’ concluding comedy songs, but they are more often than not a pedagogical, musical, and linguistic joy. While listening, my partner and I often bet on what he’ll choose as a topic. Babylon’s gods sing about how much they love beer; the heroes of Greece and Troy engage in an epic rap battle; Orestes and Electra share a bluegrass hoedown. The podcast embraces silliness but is, in its research and context, incredibly serious. I can’t recommend it highly enough for anyone seeking a deeper understanding of the ancient literature that influenced today’s. —Emma Hine

Still from Soleil Ô. Courtesy of Janus Films.

On September 29, the Criterion Collection released the latest box set of Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Project. Founded in 2007, the World Cinema Project started as an extension of Scorsese’s Film Foundation, as a means of preserving cinema from countries outside of Americentric and Eurocentric traditions. Of the six films released in the latest box set, Soleil Ô (1970), by Med Hondo, from Mauritania has made quite the indelible impression on me as an expansion of the oeuvre of postcolonial, Africa-centered films. Like other postcolonial films, such as Touki Bouki (1973), by Djibril Diop Mambéty, or Ousmane Sembène’s 1966 film Black Girl, Hondo’s film takes on the question of African identity, the effects of colonialism, and the inheritance of trauma. What sets Soleil Ô apart is the protagonist’s voice as he chronicles his travels through Paris until his descent into madness. The audience is fully enmeshed in the psychosis of the protagonist as he attempts to make sense of his humanity, or lack thereof. The fourth wall is intentionally broken throughout the film. There are no extras, because everyone is a spectator. Spectators in the film are as much an audience as the people watching the film. Often, spectators look to the camera or gawk at the protagonist without being cued. Hondo shows us how Blackness becomes theatrical in the imagination of white people. The juxtaposition of the white gaze within the film and the film as an artistic object with an exterior audience shows how two-fold this violence is, how it happens in real time for the protagonist. I have seen this movie a couple of times now and the protagonist’s descent into madness resonates with me, as I think of the camera that is always present. The protagonist has no private space. As an audience, our last act becomes to witness him, and to confirm his descent by imposing our gaze until the film’s end. —Cheswayo Mphanza

Not only am I happy when I’m watching the YouTube video of the Commodores singing “Nightshift,” I’m only happy when I’m watching this video. Like anything by Mozart or George Eliot or Van Gogh, it has unfathomable depths, but first it pulls you in with its surface. On its surface, it’s a training film: if you’re not cool, the video will teach you how to be cool, and if you’re cool already, it’ll teach you to be cooler. Watch the guys groom before the concert. Watch them as they sway on stage, not in a choreographed way but the way people do when the music skips past the cerebral cortex and goes directly to the hips and feet. Then the good stuff kicks in: tributes roll out to Marvin Gaye and Jackie Wilson, monumental figures who are celebrated so casually that you feel you’re listening not to a bunch of associate professors of musicology taking a break at a scholarly conference, but to five guys in a parking lot who’re just getting ready to start the night shift.

And what is the night shift? Here it’s the bardo, the Tibetan Buddhist state between this life and the one we’ll be reborn into. As in George Saunders’s novel Lincoln in the Bardo, in which the president walks among the shades as he searches for his dead son, Willie, here the living musicians commune with the dead ones: “You found another home,” they say, “you’re not alone,” and “we’ll be there at your side.” There’s an air of happy exhaustion throughout the whole piece, starting with that Jamaican dancehall beat and ending with the band looking as though they’ve showered after work and are now wearing Romulan navy uniforms out of a forgotten Star Trek episode, ready to party before they have to go to work again. The YouTube video of the Commodores singing “Nightshift” is the best short film of 1985, the year the song was released, and every year thereafter, which is why I’m going to stop writing and go watch it again after making one final point, which is that if more people smiled like William King (the Commodore in the red shirt), there would be no more wars. —David Kirby

November 12, 2020

Notes on the Diagram

This is the third, previously unpublished version of “an endlessly revised essay” that Amy Sillman started in 2009 during a residency at the American Academy in Berlin. The first version was published in the O.-G., v. 1, “Zum Gegenstand / Das Diagram” (2009), which Amy Sillman elaborated in parallel with her solo exhibition “Zum Gegenstand” at CarlierGebauer, Berlin, May 2–June 13, 2009. The second version appeared in the O.-G., v.1–2, “American Edition” (2009), published on the occasion of a presentation of drawings by Sillman at the Sikkema Jenkins booth, Art Basel Miami Beach, 2009.

In this sense, a subject is “a nothingness, a void, which exists.” (Lacan)

—Slavoj Žižek, Organs without Bodies

A virtual particle is one that has borrowed energy from the vacuum, briefly shimmering into existence literally from nothing.

—David Kaiser, American Scientist magazine

The Higgs boson is apparently the most powerful particle on Earth, but it has never been seen.

—2009 Wikipedia article on the Higgs boson

Look who thinks he’s nothing.

—Punch line of a joke about a priest and a Jew

One paints when there is nothing else to do. After everything else is done, has been “taken care of,” one can take up the brush.

—Ad Reinhardt, “Routine Extremism”

I can swim like everyone else, only I have a better memory than them. I have not forgotten my former inability to swim. But since I have not forgotten it, my ability to swim is of no avail and in the end I cannot swim.

—Franz Kafka

What happens next? Of course, I don’t know. It’s appropriate to pause and say that the writer is one who, embarking upon a task, does not know what to do.

—Donald Barthelme, “Not-Knowing”

In 2009, I got a grant to live in Berlin, arriving with barely any German language under my belt. An old friend, who seemed in the know, warned me: “German is a spatial language.” I have no sense of space, so it sounded ominous. I got what she meant fast at my first German lesson, when they said that in German you can’t just ask “where?”—you have to specify where to or where from. And German grammar went on from there, a thicket of specificities. And German history was a veritable morass. I was an American: I hadn’t read Hegel or Schlegel! But once I got into it, I went into an accelerating state of diagram fever, going a little crazy thinking about how everything in the world is a diagram. I took a seminar on diagrams at the Freie Universität with Danish diagram expert Frederik Stjernfelt; I got new diagram study-buddies, my mind stretched out with increasingly dizzying interconnectivity; everything started to make a weird kind of sense, and I got it: everything was related to everything else. The Enlightenment, Romanticism, Symbolism, modernism, Bad Painting, it was all locatable on one big map. I also sheepishly realized that I was probably the last person to figure this out—that this diagram thing had already been laboriously theorized by many others. But thinking about the diagram liberated my work. Abstraction itself suddenly seemed like one big diagram of moving time and space. The process of making something go away from “realness” to abstraction seemed like a big memory-diagram—things seen and then registered in the mind’s eye undergoing a process of being stripped clean, or becoming a bit tattered and distorted as they move off into your past. I was planning an art show at the time, and I also thought, if everything is everything, then why not hang things all together: satirical diagrams next to figure studies next to abstract paintings? I would just need some way to explain it all, a kind of translation device. And what is a zine if not a slapdash chance to present one’s own epiphanies? And what is a diagram but a way of holding disparate ideas together?

So I began planning my exhibition with everything in it, from abstract paintings to comical seating diagrams, to figure drawings to a zine on a table. Let jokes be paintings, paintings be memories, and memories be meaning. I decided to write an essay about diagrams for my first zine (and I’ve been slowly adding to it ever since).

*

Diagrams are great because you can put anything in them. No wonder they have been so useful for generations of kooks, mystics, Cubists, ecstatic poetics, Dadaists, Futurists, and weird scientists. A diagram is a perfect visual schema for posing impossible things, invisible forces, enigmas like the future—all posed as perfectly plausible vectors. The diagram even outdid the camera as the early twentieth century’s best new thing because it could depict things in the universe that exceed the eye, like particles, waves, and quarks. A diagram’s scale is endless. It can indicate how dwarfed we are by the universe, or how busy the microscopic world is, all mapped out on the back of some envelope. Tides, black holes, white dwarfs, red rings around Saturn, crazy particles, the waves of the Big Bang, all teleporting around in unstable ways, all this stuff and how it interacts can appear equally on the diagram, democratically, like the pedestrians in Times Square or the people in a Saul Steinberg cartoon all walking around together. The diagram’s arms, its vectors, embrace everything at once. Parts are not distinct from wholes, and divisions between aesthetic formats don’t have to exist. Diagrams aren’t medium-specific: everything is a continuum; everything is relational. In this sense a diagram is utopic, showing how things should or might go, reenvisioning things expansively, not merely describing them categorically. It can include contradictory grammars, fragments, part-objects, nouns and verbs, acts and objects. As a painter, I was on solid ground, then, because I already knew that paintings are both things and events. And one of the first things artists learn is that scale and size are different. Scale is relational, whereas size is just measurement. Likewise, a mere page in a notebook, a flimsy joke, a drag act, can change the world. My own life was altered definitively by the aesthetic detonating charge of a confessional 16 mm George Kuchar film, Hold Me while I’m Naked (1966), in which an erstwhile filmmaker from Queens tries in vain to complete a porn film. It affected me way more than beholding the majesty of the Pergamon Gate, or beholding the Mona Lisa. (Likewise, in Freud’s famous diagram, the idea of a Baby holds the same valence as Shit!) Any little thing, impure as can be, can change your life.

My favorite diagram thinking was about painting and language: Gilles Deleuze, Charles Olson, David Joselit. In Deleuze’s book on the painter Francis Bacon, The Logic of Sensation, the very concept of the diagram is an action, not a thing but a moment, a moment of transformation. Perhaps inspired by the visual portals, stages, and furniture that Bacon sets his figures against, Deleuze’s “diagram” is his way to describe the action of Bacon’s figures as they transform agonistically. David Joselit’s essay “Dada’s Diagrams” describes diagrams as a kind of container, a come-one-come-all structure for representing the polymorphous perversity, the rupture, of the early twentieth century: “Far more important than [Francis] Picabia’s adoption of a vocabulary drawn from industry in his ‘machine drawings’ is the model of polymorphous connectivity between discrete elements that these works deploy in order to capture the uneven economic and psychological transformations and the jarring disequilibrium characteristic of modernity.” The poet Charles Olson’s manifesto from 1950, Projective Verse, also describes a kind of spatial diagram of action. He imagines language as a set of something like arrows—utterances as projectiles that ride out of the poet’s mouth and land in the world, demarcating a sort of invisible forcefield. This kind of invisible language-force might be subtle but it’s big: the relational aesthetics of language as a force.

I always felt that what made the painter Ad Reinhardt great wasn’t the otherworldly clarity of his abstract paintings (I wasn’t really that into the religious way that people would gasp when they finally saw the colors); it was the fact that alongside his austere experiments with pure color and structure were his diagrams about the art world, which included puns, mockery, and sarcasm. It was the split of his greater whole, the parts mapped together, neither his solemnity nor his jokes but the passage between such states (and, in between those two, his deadpan slideshow presentations of shape-forms). When I realized the larger diagram of his work, I realized that what was great was his circulation system, an economy of high and low parts given equal value. I had never been able to resolve the two coasts of my own sensibility, my love of cartoons with my love of serious-minded abstraction. But diagrams made me realize that they were related, constituted precisely by the interactions between them. All the good funny Modern art (like Daumier, Guston, Reinhardt, Beckett) was tragicomic. Making art came from the same psychic pneumatics that Freud mapped out as the origin of jokes: distillation and compression. The joke work, the dream work, the art work: all of these were ways to cope. Ways for the mind to grasp what it has seen, moving it from the optic nerve to the mind’s eye as it moved from the present to memory, via abstraction. Jokes were the bailiff of high art, getting it out of its cramped quarters, and providing skepticism so you didn’t love it too much.

*

At first I was in this love affair with diagrams. Weren’t they wonderfully inclusive models of multiplicity, contradiction, and change? Weren’t they democratic? That was before I read Benjamin H. D. Buchloh’s sobering essay on Eva Hesse, “Facing the Diagram.” In his more critical eyes, the diagram was also a manifestation of social conditions, a state of quantification, surveillance, and bureaucracy. Diagrammatic works like Duchamp’s Network of Stoppages (1914) or Hesse’s drawings from 1966–67 therefore also registered “the total subjection of the body and its representations to legal and administrative control.” This diagram was not my protagonist! Was the diagram also a form of violence? Was the flip side of the feeling of the “authentic” body always bounded by the “externally established matrix” of conditions? Was the body even possible without the conditions surrounding it? Oh god, Buchloh was probably right—I had been filled with euphoria, but the diagram and painting were linked, and in the bad sense: the same problematics that I had faced in painting were back to haunt me with the diagram.

Postwar painting, which I loved, was riddled with the same problems. It was the same sentimental stuff that Ad Reinhardt was attacking with his diagrams, with his stubborn refusal to be boxed in. When I first learned about AbEx painting as a student, I had felt liberated by it, not oppressed—the way it located thinking as something you do with your body—the way that by including the body in intelligence, you were attacking something. I felt that gesture painting was done with a kind of political body, maybe akin to the poets and their projective verses. I went for the idea that gesture painting was a form of expression lying between language and image, an utterance that implicates the maker, along the lines of “the personal is political.” I got out of the AbEx-by-genius-men problem by seeing how many women painters there were, how many great painters of color there were, and thought the problem wasn’t the art but the art history. Art history was wrong. Critical theory didn’t seem wrong but I got out of the commodity problem by focusing on drawing, not painting. Could I also get out of the diagram-as-control problem by thinking about the way a diagram makes you think? Could emancipatory possibilities exist in new thinking? Could instrumentalization be defeated? Could diagram-thinking/studio practice/painting go “beyond control”? I felt intuitively that the answer had to be located in some way in something messy: accidents, negations, a spill, some excess found on the floor, some physical inexplicability, the idea of desire, urges, pleasure, which I thought was exactly bound up with the not-knowing part of the art-making process, the drawing process as entirely separate from value-formation. This was not utopian, it was just practical: thinking and hoping that exactly where those arrows of Projective Verse land is where something like being and life can be felt. As in Emily Dickinson:

I am alive—I guess—

The Branches on my Hand

Are full of Morning Glory—

And at my finger’s end—

At finger’s end, beyond the graph, off the chart, in the realm of not-knowing, lay the weird unformed excess, the chora, not information. The fact that I don’t know what word will come out of my mouth next, exactly, when speaking a sentence, or what jerky motion I’ll make when taking a step, or whether I’ll continue living past the bus stop at all, made me turn to the idea of improvisation as a kind of conscientious reminder of how fragile everything is, how unstable and unknowable. The diagram’s best form, painting’s best aspect, seemed to lie in its unknowns, its silence, its way of not working out, or being at risk, a matter of fate, ruin, or possible resuscitation. Painting was dead, but it surprised me. So, isn’t there an end zone, an offstage in the theater? The painter Charles Garabedian said making a painting is like purposefully stumbling around in a fog near a cliff. It’s a mess of unknowns, beyond diagrammable. So it seemed like the very idea of knowing was where the problem lay, maybe. The diagram only shows us the stuff arrayed in a space. The diagram doesn’t consider its errors. Therefore, comedy, accident, mistake, is the corrective for the diagram, because it includes everything the diagram can’t even hope to establish as a solid: spasms, screwups, sabotage, refusal, stupidity, the saggy droop between the vector showing “what you did” and what really resulted. Whatever is incalculable, including the feeling of a mistake. I’d like to see the diagram of that. Failure and dread. That’s why I still loved abstraction, because we knew it didn’t work, that it was a failure, a paradox, a realm of both potential and unchartability. David Joselit wrote that the “act of reconnection does not function as a return to coherence, but rather as a free play of polymorphous linkages which … remains a central motif of modern (and postmodern) art.” Diagrams are failures, paintings are failures, and life is a failure. The diagram can only do so much. The rest is as Donald Barthelme asks, “What happens next?” And then the answer is, “I don’t know.” That’s what a good diagram indicates: that there are things beyond control.

Based in New York City, Amy Sillman is an artist whose work consistently combines the visceral with the intellectual. She began to study painting in the seventies at the School of Visual Arts and she received her M.F.A. from Bard College in 1995. Her work has been exhibited internationally, including at the Whitney Biennial in 2014; her writing has appeared in Bookforum and Artforum, among other publications. She is currently represented by Gladstone Gallery, New York.

Excerpted from Faux Pas. Selected Writings and Drawings. , by Amy Sillman, published by After 8 Books and distributed by Artbook | D.A.P.

U Break It We Fix It

Sabrina Orah Mark’s column, Happily, focuses on fairy tales and motherhood.

I am inside U Break It We Fix It holding my sons’ shattered iPad. “Hello,” I call out. No one answers. The counter glows white, and the walls are empty. “Hello? Hello?” I wait a few minutes before calling out again. “One minute,” says a raspy voice from the back of the store. Hope swells in my chest. Here We comes. We will fix it.

A man in rumpled clothes emerges. I put the shattered iPad on the counter. “Don’t put it there,” We says. I quickly lift it off the counter. We sprays sanitizer on the spot I touched and wipes it dry with a paper towel. I hold up the broken screen so We can see It, and a little shard of glass drops to the floor with a plink. “Yeah, no,” We says. “Yeah no, what?” I ask. We says the soldering work required would cost more than a new iPad. We says it would take weeks. “Possibly months.” To be sure We asks me to read the serial number off the back of the iPad. I read the numbers, and We silently types them into a computer. “Yeah,” We says. “It isn’t worth it.” I just stand there. “But if I break It, it says We fix It.” I point to the sign that is the name of the store. Even if We has to send it far, far away. Even if it takes the handiwork of one hundred mothers with long white beards and God inside their fingertips, We should fix it. We promised. Even if all We ever do is just try to fix It, We should try. But the man is gone. He has already disappeared into the back of the store.

The next week, I return to U Break It We Fix It with a whole entire country. It’s heavy, but I manage to carry it through the parking lot leaving behind a trail of seeds and the crisp scent of democracy and something that smells like blood or dirt. Across it is a growing crack. A child, too young to be alone, is out in front holding a broken country, too. “Store’s gone out of business,” says the child. I shift the country to one arm and try to peer in, but it’s shuttered and dark. “Told you,” says the child. “Out of business.” I text my husband: “U Break It We Fix It is closed. I’ve come here for nothing … again.” When I look up the whole parking lot is full of children holding countries. “Is this U Break It We Fix It?” they ask. “It once was,” says the first child, “but now it’s closed.” The children hold their countries closer, like a doll or an animal. I want to drive them all home but they’re all holding countries and there are far too many of them. “I’m sorry,” I say too quietly for any of the children to hear. I don’t ask them where their mothers are or how they got here or how they will get home. Instead I walk quickly back to my car. A little shard of glass falls out of my country with a plink. I pick the shard up and hold it to the sunlight. A rainbow, just for a second, falls over the children. Plink! Plink! Plink! Shards of glass are falling out of the children’s countries, too. It sounds like an ice storm, but the sky is blue and the children are dry as bones. I don’t want to stay to see what happens next. I drive away. I leave the children cradling their broken countries. I have no idea where any of them live, or how to fix anything, or what to do with this shard of glass. At a red light, I put the shard in the glove compartment and forget about it for days.

In Exodus, the first set of ten commandments (broken by Moses) is not buried but placed in the Aron Hakodesh (the holy ark) beside the new, unbroken tablets, which the Jews carry through the wilderness for forty years. I imagine the broken tablets leaning against the unbroken ones telling them secrets only broken things know. I imagine the weight of the broken tablets, and the heat, and the thirst, and the frustration. Why didn’t we just leave the broken tablets behind? What good is all this carrying?

To know your history is to carry all your pieces, whole and shattered, through the wilderness. And feel their weight.

“Mama,” say my sons one thousand times a day, “can you fix this?” Hulk’s head has fallen off, or the knees of a favorite pair of pants are torn, or the bike chain has snapped, or there is slime on Eli’s favorite polar bear, or the switch is stuck, or the spring broke off, or Superman’s cape is hanging by a thread, or … “What even is this?” “Oh, that?” says Noah, my nine-year-old. “It’s where the batteries are supposed to go.” “But for what?” I ask. Noah and I study it for a whole entire minute. “I have zero idea,” he says.

What breaks most often in fairy tales are spells, and when a spell is broken the world is restored. The beast turns back into a prince, the kingdom wakes up, and a girl’s tears dissolve the shards of glass in a boy’s cold heart. I look up the word “spell.” It means the letters that form a word in correct sequence, and it means a period of time, and it means a state of enchantment. All of these things bind. But there is one last definition I catch, at the bottom. Spell also means a splinter of wood. What binds is also what cracks off. A spell is also what strays from the whole. This splinter of wood feels like a clue to a mystery I hope to never solve. I add the splinter (that is, a spell) to the shard of glass in my glove compartment. I leave them there together in the dark.

We are knee-deep in broken things. I wade through the kitchen, and the news, and our yard. The dryer is making a sound. The country is divided. Tree limbs are everywhere. “How did the switch break off the lamp?” I ask Eli, my seven-year-old. He shrugs. “It’s like a miracle,” he says.

In Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Snow Queen,” a demon makes a mirror in which the image of whatever is good or beautiful dwindles to almost nothing, while the image of anything horrible appears even more horrible: “In the mirror the loveliest landscapes looked like boiled spinach, and the kindest people looked hideous or seemed to be standing on their heads with their stomachs missing.” The demon’s disciples travel all over the world with the mirror until there is not “a single country or person left to disfigure in it.” Then they fly to heaven to distort God and the angels, but the mirror shakes hard with laughter and shatters into a “hundred million billion pieces.” The air fills with mirror dust, and the glass blows into the eyes and the hearts of people everywhere. Each shard has the exact same power as the whole entire mirror. Whoever gets mirror in them is cursed with a hardened heart, and with seeing the ugliness of everything.

In Jewish mysticism there is a phase of Genesis called Tsim Tsum that is like the inside-out version of this fairy tale. The glass is not from a demon, but from God. According to the cabalists, in order to give the world life, in order to effect creation, God must depart from the world God created. The creator must always exile himself from the creation for the creation to breathe. God contracts to make space so that the world can exist. But right before the departure, God (like a mother) stuffs divine light into vessels that will be left behind. The vessels cannot contain God’s light, and burst, and shards of light are scattered everywhere. Gershom Scholem explains that we spend our lives collecting the offspring of this light. We spend our lives trying to make what once was broken whole again. This, according to the cabalists, begins the history of trauma.

In “The Snow Queen,” the good widow crow wraps a bit of black woolen yarn around her leg to grieve her dead sweetheart. I feel I should wrap something around my leg, too. It is almost the middle of November. I grieve for the past four years. They were such sick and tired years and so much fell to pieces. There is so much mirror dust in our eyes. “Move on,” texts my mother. “Up and out,” texts my mother. I get up and go to my car. I open the glove compartment. The shard is in the shape of a country that seems vaguely familiar, and the splinter is long and sharp like a tongue. I should’ve stayed with the children and helped them pick up the pieces. Maybe if we had put all our pieces together the pieces would’ve spelled something. Maybe it would have been a word we need, and now we’ll never know. I drive back to U Break It We Fix It. Someone has painted over the sign but the words are still legible like a body under a thin sheet. The store is still dark and shuttered and the parking lot is empty except for a crow who has a bit of black woolen yarn around her leg. The crow stares at me. “Hi crow,” I say. I notice something shiny in her beak. She drops it at my feet. It’s a shard of glass that fits with my shard of glass perfectly. When I put the two pieces together it looks like a transparent hand reaching out to help someone up. I want to jump for joy. We have only one hundred million billion pieces to go.

In exchange, I give the crow the splinter. She picks it up in her beak where a tongue begins to grow. “Sit down,” says the crow. And I sit down in the middle of the parking lot. Just me and the crow on a soft autumn night. “Listen,” says the crow. And I listen. And she tells me a fairy tale I’ve never heard before about a whole entire country that almost disappeared.

Read earlier installments of Happily here.

Sabrina Orah Mark is the author of the poetry collections The Babies and Tsim Tsum. Wild Milk, her first book of fiction, is recently out from Dorothy, a publishing project. She lives, writes, and teaches in Athens, Georgia.

November 11, 2020

Inside the American Snow Dome

Dear Reader,

Do you know what a snow dome is? I believe you do not so I will tell you. It is this: a snow dome is an object, dome-like in shape, resting on a flat piece of material that is fitted to it and sealed perfectly to its base. The entire structure is made of a material that is easily shattered. Inside, the dome is filled about three quarters of the way up with water. Scenes of one kind or another are created and fixed to the bottom of the dome. Flakes of something white made to resemble snow are settled at the bottom of the dome, and when the dome is shaken, as it often is by a playful hand passing by, the flakes rush up in a flurry around the scene that has been fixed to the bottom of the dome. All the figures and objects are lost in a blur of the pretend snow, they are consumed by it, and for a moment, it seems as if this will be the new forever: they will never be seen clearly again. Then the false snow slowly settles back to the bottom of the dome and everything returns to the way it was. The scene remains just as it was before, fixed, fixed, and fixed! The snow dome is usually found at the destinations of grim family vacations: Disneyland, the Bronx Zoo, the Empire State Building, the Statue of Liberty, the area of airports near the gates of departure, places you very well might never visit again because you never wish to visit these places again. Such is the existence of the snow dome.

For the past four years, starting sometime in early November 2016, I have been living in a snow dome that resembles the United States of America. I have been a figure in this snow dome. The color of the water in it was sometimes orange, sometimes a rage red, and the color of the snow was never white. It has been a shameful experience. I have been trapped here. The United States of America is to me the most wonderful country in the world, and it really is, but only if while you live there you attach yourself to the best people in it and the best people in it are Black people, African American people. If, when you go to the United States, you attach yourself to the group of people who call themselves “White” you will consign yourself to misery and minor and major transgressions against your fellow human beings and also greediness and everyday murder. And more. Here’s how you live in America: your children must go to the best schools and the best schools are always for white children and you’ll completely forget the best schools have never helped anybody be a good person (see George W. Bush, just for a passing reference). With the exception of most likely John Adams (second president of the United States for one term) and most certainly Barack Hussein Obama, all the presidents of the United States of America were racists and their racism was especially and particularly directed at Black people of African descent. The great Abraham Lincoln, a president I am so deeply attached to I grow roses named in his honor in my garden, was a racist but he abhorred slavery and that’s good enough for me, being that I am most blessedly descended from the enslaved (I say blessedly but I really mean accidentally because blessings are so random, they are in fact accidents). The United States of America, before it even became such a thing as the United States of America, was a roiling unsettling snow dome of transgression, and from the beginning that transgression was caused by people immigrating from Europe.

Perhaps this land has been inside a snow dome since August 3, 1492, but right now, let me look at the one I am in that appeared in early November 2016. All at once the open skies under which I lived in the state of Vermont closed up, which was very odd, for in September of 2001, which was a time of darkness, the open sky in the state of Vermont under which I lived couldn’t have been more open, more blue, more inviting and welcoming. But now, or then, however I want to regard it, the sky above me in 2016, that November, grew dark: words do change the color of things. Shortly after November of 2016, the people who were not allowed to come into the United States of America could trace their exclusion to the America of the slave states, which, after they were defeated, found a way to rise again. That particular snow globe is the one most of us are in. To make groups of people feel they are less than who they are, to make groups of people feel they are more than who they might be, to make groups of people teeter between more or less is an American idea, an American aspiration. But nothing is permanent, even in a snow globe, for sometimes a stray arm will knock it off its shelf (the shelf is the permanent home of the snow globe). There was the ban on people from “Islamic” countries. But what countries were those? In the Elizabethan era, after the defeat of Spain, Catholics more or less became racialized; when I was growing up as a little girl on a British-ruled island in the Caribbean, I was told that Catholics—that is, people from Italy and Spain and places like that—were not really white people and that idea was so strong in me that when I came to the United States, and met so many people who said they were white (Italians, Spaniards, just about anyone Catholic), I lost any fear I might have had of white people. This was a great comfort for me personally: I met plenty of racism but usually the people directing it toward me, I knew them to have had their own difficult encounters with the permanent impermanence of the snow globe. And so the people from countries where Islam was the dominant belief were like Catholics and also they were like Black people in America: segregation is an American ideology. Only African Americans/Black Americans instinctively understand this and that is why we are the true Americans. It is also why many immigrants to America try to get as far away as they can from identifying themselves with African Americans (the Irish, the fair-skinned immigrant from India, the fair-skinned immigrant from China, Korea, Japan): because the African American is American for the long haul, there is no America without the African American/Black people. Everyone loves what Black Americans are and do, they just don’t want to be them. The American obsession with freedom is simply because we have lived so intimately with people we made “not free.” We know very well the situation of the “not free.” The African American is the definition of the “not free.” America is a peculiar place: it has fifty states, half of them are named after the Native people who inhabited the land called America; it goes from Alabama to Wyoming. The American national motto could easily be “kill the people, keep their names.”

On a morning over this past weekend, in early November 2020, someone passed by the table where the snow dome I have been living in for four years lies and just deliberately knocked it to the floor. It shattered into many pieces, the water disappeared, soaked into the wooden floor. The phony snow did not melt of course, but all the figurines were broken. I picked up the pieces of the good ones, myself included (yes, it’s my snow dome and I get to decide). I would mend them back and try my best to make them whole again. I then took a hammer, one I use in the garden to hammer stakes into the earth, and I ground and ground the rest of them into dust.

The writer, novelist, and professor Jamaica Kincaid’s works include Annie John, Lucy, The Autobiography of My Mother, Mr. Potter, A Small Place, My Brother, and See Now Then. Her first book, the collection of stories At the Bottom of the River, won the Morton Dauwen Zabel Award from the American Academy and Institute of Arts and was nominated for the PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction. Professor of African and African American studies in residence at Harvard, Kincaid was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters. She has received a Guggenheim Award, the Lannan Literary Award for Fiction, the Prix Femina Étranger, Anisfield-Wolf Book Award, the Clifton Fadiman Medal, and the Dan David Prize for Literature.

This essay originally appeared in Swedish in the newspaper Dagens Nyheter.

November 10, 2020

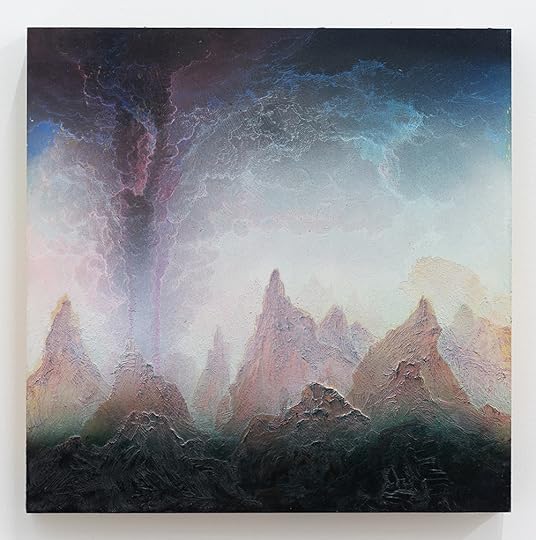

Joan Nelson’s Landscapes

For nearly four decades, Joan Nelson has made it her mission to upend the male-dominated tradition of landscape painting. Rather than commit herself to straightforward reproductions of the natural world, Nelson paints reality with a fabulist’s brush. Using such unconventional materials as mascara, nail polish, and burnt sugar on sheets of plexiglass, she merges landscapes real and imagined to present scenes that can be encountered only within the infinite expanse of art. “New Works,” Nelson’s third exhibition with the gallery Adams and Ollman, will be on view through December 19. A selection of images from the show appears below.

Joan Nelson, Untitled, 2019, spray enamel and acrylic ink on acrylic sheet, 24 x 24″.

Joan Nelson, Untitled, 2020, spray enamel, oil, and acrylic ink on acrylic sheet, 24 x 24″.

Joan Nelson, Untitled, 2020, spray enamel and acrylic ink on acrylic sheet, 20 x 20″.

Joan Nelson, Untitled, 2020, spray enamel, acrylic ink, marker on acrylic sheet, 24 x 24″.

Joan Nelson, Untitled, 2018, spray enamel, acrylic ink, and mascara on acrylic sheet, 12 x 12″.

Joan Nelson, Untitled, 2019, spray enamel and acrylic ink on acrylic sheet, 24 x 24″.

Joan Nelson, Untitled, 2020, spray enamel and acrylic ink on acrylic sheet, 24 x 24″.

Joan Nelson, Untitled, 2020, spray enamel, acrylic ink, marker, and burnt sugar on acrylic sheet, 20 x 20″.

“New Works” will be on view through December 19 at Adams and Ollman in Portland, Oregon.

Redux: The Feeling of an Airplane Crashing

Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

Kurt Vonnegut, ca. 1972. Photo: PBS.

This week, The Paris Review is thinking about Veterans Day. Read on for Kurt Vonnegut’s Art of Fiction interview, M. F. Beal’s short story “Veterans,” and Jim Carroll’s poem “Traffic.”

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, and poems, why not subscribe to The Paris Review? Or take advantage of our new subscription bundle, bringing you four issues of the print magazine, access to our full sixty-seven-year digital archive, and our new TriBeCa tote for only $69 (plus free shipping!). And for as long as we’re flattening the curve, The Paris Review will be sending out a new weekly newsletter, The Art of Distance, featuring unlocked archival selections, dispatches from the Daily, and efforts from our peer organizations. Read the latest edition here, and then sign up for more.

Kurt Vonnegut, The Art of Fiction No. 64

Issue no. 69, Spring 1977

VONNEGUT

I said, By God, I saw something after all! I would try to write my war story, whether it was interesting or not, and try to make something out of it. I describe that process a little in the beginning of Slaughterhouse Five; I saw it as starring John Wayne and Frank Sinatra. Finally, a girl called Mary O’Hare, the wife of a friend of mine who’d been there with me, said, “You were just children then. It’s not fair to pretend that you were men like Wayne and Sinatra, and it’s not fair to future generations, because you’re going to make war look good.” That was a very important clue to me.

INTERVIEWER

That sort of shifted the whole focus …

VONNEGUT

She freed me to write about what infants we really were: seventeen, eighteen, nineteen, twenty, twenty-one. We were baby-faced, and as a prisoner of war I don’t think I had to shave very often. I don’t recall that that was a problem.

Veterans

By M. F. Beal

Issue no. 98, Winter 1985

She settled back in her seat. It was accidental, this trip. Ross had been working on a neighbor’s caterpillar tractor and the gear slipped, lowering the blade onto his knee. Nothing broken, but after a few days the bruise turned into a puffy swollen redness which began to throb. Ross could go to a V.A. hospital for treatment; the neighbor was uninsured. Ross had done some work for her, too, not long after her husband died, and one day he brought her a dozen dark red roses. Some nights he stayed over in the bunkhouse instead of driving his old gas-guzzler to his sister’s, in return for helping her with some of the heavier chores.

Traffic

By Jim Carroll

Issue no. 45, Winter 1968

I was a young pilot in World War I, remember?

do you know the feeling of an airplane crashing the water’s edge?

we’ve just traveled 600 miles, and the only person

we know is sleeping under the wet almond tree.

there is nothing left but this meadow which smells of blood …

And to read more from the Paris Review archives, make sure to subscribe! In addition to four print issues per year, you’ll also receive complete digital access to our sixty-seven years’ worth of archives. Or take advantage of our new subscription bundle, bringing you four issues of the print magazine, access to our full sixty-seven-year digital archive, and our new TriBeCa tote for only $69 (plus free shipping!).

Re-Covered: Living Through History

A woman sips a cup of tea after her street is struck by a German bombing raid, 1940

Since the beginning of lockdown, I’ve sought refuge in sagas set during the Second World War. There is something deeply comforting about reading stories in which people are trying to live their lives against the backdrop of an intense global crisis, not least because it’s given me a much-needed sense of perspective. It’s so easy to become caught up in the myriad horrors of the contemporary moment, one sometimes forgets that the darkest days of the Second World War would have been just as depressing and desperate as the period we’re living through right now.

Of the many books on the subject I read, Blitz Spirit: Voices of Britain Living Through Crisis, 1939–1945—a brilliant new compendium of extracts from wartime diaries compiled from the Mass Observation Archive by the anthologist, editor, and literary agent Becky Brown—has stuck with me. Mass Observation (MO) was set up in 1937 by the anthropologist and polymath Tom Harrison, painter and filmmaker Humphrey Jennings, and poet and journalist Charles Madge. It’s aim, Brown explains, was “to tell a truer, fuller version of events than was available in the newspapers or recorded in the history books,” or, as the founders themselves put it, to collate an “anthropology of ourselves.” Central to the project was the five-hundred-strong National Panel of Diarists, volunteers from all walks of life living across the UK, who kept a daily personal journal that they then submitted each month. So many of the films and books from or about this period are, Brown explains, “bathed in the golden glow of ‘Blitz Spirit’,” yet this is nowhere near the full story. “This alleged wartime phenomenon has little space for twenty-first-century human frailties such as succumbing to unnecessary trips to the shops, or hugging your grandmother,” she continues, invoking the deprivations of the current pandemic. “We are used to hearing about ‘Blitz Spirit’ as psychological bunting that festooned the national mind, a one-size-fits-all utility suit that the nation donned for The Duration, allowing every person to dig their way to victory with a song and a smile.” Instead, she argues, what makes the MO Archive “so valuable and so poignant,” is that these are accounts written in real time and by real people, thus “riddled with fear and defeat.” Take, for example, this entry written by a widowed housewife and voluntary worker from London on September 1, 1941:

Life at present offers for my taste a damn sight too little active pleasure to set against the unaccustomed displeasure of work—what with friends scattered & busy, & the lack of petrol, & the shortage & monotony of food & drink, & now the beastly long blackouts creeping in again. Everything seems reduced to a vast, drab boringness.

Change a few minor details—swap rationing for quarantine and isolation, for example—and this could have been written only yesterday.

I’ve read some masterpieces on the period, Olivia Manning’s Balkan Trilogy and Elizabeth Jane Howard’s five-volume Cazalet Chronicles among them, but the one that mirrored the real-time realism of Brown’s Blitz Spirit most clearly was Bryher’s novel Beowulf, which its author wrote during the height of the relentless Nazi bombing raids on the British capital. “It is not difficult to write during a Blitz, there is nothing else to do, but merely uncomfortable,” she explained after the fact.

Although it was first published in France in 1946, and then in America in 1956, Beowulf is only now being made available in the UK, in a new edition recently published by Schaffner Press. In The Days of Mars: A Memoir, 1940–1946, Bryher describes her earlier book as “a documentary, not a novel, but an almost literal description of what I saw and heard during my first six months in London,” (Schaffner has given it a subtitle, A Novel of the London Blitz, perhaps to distinguish it from the significantly more famous Anglo-Saxon poem of the same title). She arrived in the city at the end of September 1940, having reluctantly left her home in Switzerland, to rejoin her lover, the imagist poet H. D. In its commitment to verisimilitude, rather than that “golden glow” that Brown refers to, Beowulf is steeped in fear, danger, and, above all, absolute exhaustion. It’s the anti–Mrs. Miniver, if you will, which is precisely what made it unpublishable in postwar Britain. “The English refused to publish Beowulf,” Bryher explains in The Days of Mars, “they had had enough of war.” Yet reading the book today, it feels urgent and absorbing. Despite the glaring differences between a nation at war and one fighting a deadly virus, Beowulf makes for especially timely reading right now, proof of a surprising number of similarities, parallels, and echoes between the past and the present.

*

The book takes its title from the name that one of its protagonists, Angelina, gives a plaster statuette of a British bulldog—“almost life size, with a piratical scowl painted on his black muzzle”—that she buys in a salvage sale. She displays the bulldog in pride of place in the Warming Pan, the London tea shop that she runs with her friend Selina. This small, rather inconspicuous establishment, with its now “stinted and miserly” supply of cakes, is the hub around which the action of the novel takes place. It “fulfilled a need in the neighbourhood […] a cross between a village shop and the family doctor,” somewhere for people to meet a friend for a cup of tea, stop by for lunch during a day of shopping in town, where a shop girl can get a hot meal, or, in the case of Horatio Rashleigh—the elderly, impoverished painter who lives alone in a small, cold flat in the attic of the same building—just while away the long, lonely hours. The Warming Pan was a real tea shop, situated just around the corner from H. D.’s flat in Lowndes Square in London’s Belgravia, as were its proprietors. Bryher and H. D. frequented the Warming Pan for their meals, and they became extremely fond of the real-life Angelina and Selina, too. “My dear, dear Selina,” Bryher writes in The Days of Mars. “She was a symbol to me of the essential soul of England.” Beowulf, the ironically named bulldog statuette, takes on this role in the book: he stands in pride of place in the tearoom’s empty fireplace, a symbol of “common sense” and of the British people’s bulldog spirit, the tenacity and courage they display even during the country’s darkest hour.

Bryher and HD, Still from Kenneth Mcpherson’s film Borderline, 1930

Despite having published prolifically—Bryher’s work includes memoir, poetry, nonfiction, and novels—few of these volumes remain in print today. Instead, it is the author’s relationships with others for which she remains best known; as H. D.’s lover, but, more generally, for her association with other expat writers, artists, and intellectuals who made Paris their home in the twenties. She was friends with Ernest Hemingway, James Joyce, Gertrude Stein, Alice B. Toklas, and Sylvia Beach and her lover, Adrienne Monnier, who was also the proprietor of La Maison des Amis de Livres. (Beowulf is dedicated to Beach and Monnier.) Bryher had deep pockets—her father had made a fortune from his shipping business; on the occasion of his death in 1933, he was said to be the richest man in England—thus she acted as a generous patron to many other writers as well as publishing her own work.

Born Annie Winifred Ellerman in 1894, she later adopted the more androgynous-sounding Bryher, naming herself after her favorite of the Scilly Isles, that remote and beautiful archipelago off the Cornish coast. The wild isolation of these heath-covered islands spoke to her desire to reject convention, particularly its gendered norms. “Her one regret was that she was a girl,” explains Nancy, the protagonist of Development, the first of Bryher’s pioneering three-volume fictionalized autobiography—which continues in Two Selves and West—that details her gender dysphoria:

Never having played with any boys, she imagined them wonderful creatures, welded of her favourite heroes and her own fancy, ever seeking adventures […] She tried to forget, to escape any reference to being a girl, her knowledge of them being confined to one book read by accident, an impression they liked clothes and were afraid of getting dirty. She was sure if she hoped enough she would turn into a boy.

Bryher met H. D. in July 1918. From the get-go, theirs was an unconventional coupling. H. D., who was at the time married to Richard Aldington, was pregnant from an affair with the composer Cecil Gray, at whose Cornish home she’d fled to for comfort while Aldington pursued an adulterous affair of his own. As Susan McCabe explains in her introduction to the new edition of Beowulf, H. D. and Bryher “finessed their relationship by burying it in plain sight.” Bryher married Robert McAlmon in 1920, after which her father funded McAlmon’s Paris-based Contact Press, which published, among others, Joyce, Stein, Djuna Barnes, H. D., and Bryher during the twenties. Bryher divorced McAlmon in 1927, and married the filmmaker, photographer, and critic Kenneth Macpherson instead. Shortly after, the two of them legally adopted H. D. and Gray’s daughter, Perdita, whose care Bryher had been responsible for since her birth. Macpherson, meanwhile, was also H. D.’s sometime lover, and thus the four of them—Bryher, H. D., Macpherson and Perdita—forged a happy if unconventional family unit. Macpherson and Bryher built a house together in Switzerland, where Bryher remained after H. D. and Perdita returned to London in November 1939, after the outbreak of war. Bryher had begun to use her money and contacts to help Jewish refugees flee Europe as early as 1933, and she continued this work until she herself left Switzerland in 1940, making the arduous journey to London via Barcelona and Lisbon. She arrived at her partner’s flat at midday on September 28, while H. D. was out having lunch at the Warming Pan.

*