The Paris Review's Blog, page 134

December 15, 2020

Redux: Morning Full of Voices

Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

Stephen Sondheim. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

This week, The Paris Review is humming a little tune. Read on for Stephen Sondheim’s Art of the Musical interview, Sigrid Nunez’s “The Blind” (the first chapter of her novel The Friend), and Eamon Grennan’s poem “Musical Interlude.”

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, and poems, why not subscribe to The Paris Review? Or take advantage of our new subscription bundle, bringing you four issues of the print magazine, access to our full sixty-seven-year digital archive, and our new TriBeCa tote for only $69 (plus free shipping!). And for as long as we’re flattening the curve, The Paris Review will be sending out a new weekly newsletter, The Art of Distance, featuring unlocked archival selections, dispatches from the Daily, and efforts from our peer organizations. Read the latest edition here, and then sign up for more.

Stephen Sondheim, The Art of the Musical

Issue no. 142, Spring 1997

Some lyrics read well because they’re conversational lyrics. Oscar’s do not read very well because they’re colloquial but not conversational. Without music, they sound simplistic and written. Yet it’s precisely the hypersimplicity of the language that gives them such force. If you listen to “What’s the Use of Wond’rin’ ” from Carousel, you’ll see what I mean.

Photo: British Library. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

The Blind

By Sigrid Nunez

Issue no. 222, Fall 2017

Last night, in the Union Square station, a man was playing “La vie en rose” on a flute, molto giocoso. Lately I’ve become vulnerable to earworms, and sure enough the song, in the flutist’s peppy rendition, has been pestering me all day. They say the way to get rid of an earworm is to listen a couple of times to the whole song. I listen to the most famous version, by Edith Piaf of course, who wrote the lyrics and first performed the song in 1945. Now it’s the Little Sparrow’s strange, bleating, soul-of-France voice that won’t stop.

Photo: British Library. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Musical Interlude

By Eamon Grennan

Issue no. 154, Spring 2000

Cragflower. Music of the sea.

…….The flower still standing

in its tormented place.

Morning full of voices. Mourning too.

…….Mahalia singing On My Way

and making it to Cay-nen Land.

On a rock, sit, listen to Bjorling

…….sing Only a Rose

over your friend’s ashes …

And to read more from the Paris Review archives, make sure to subscribe! In addition to four print issues per year, you’ll also receive complete digital access to our sixty-seven years’ worth of archives. Or take advantage of our new subscription bundle, bringing you four issues of the print magazine, access to our full sixty-seven-year digital archive, and our new TriBeCa tote for only $69 (plus free shipping!).

December 14, 2020

In Winter We Get inside Each Other

Nina MacLaughlin’s column, Winter Solstice, will have its final installment next Monday, December 21, on the solstice.

Paul Cezanne, Leda and the Swan, c. 1882

The sledding hill in the town I grew up in was on the grounds of an institution for the criminally insane. Hospital Hill, we called it. Or Mental Mountain. It was a great place to sled.

A huge hill, a real wallomping mound of earth, a sledder’s heaven, there at the southern edge of the asylum, steep, long, with a stretch of flat at the bottom long enough that your ride could run its course without crashing into the barrier of brush and trees, or out into traffic on Route 27 beyond. At the top, asylum to our backs, we took our running starts then flung ourselves, belly flopping onto our inflated snow tubes, and whished down the hill. Or sometimes sitting upright on the tube, someone behind you, parent or pal, put their hands at your shoulder blades, started running, pushing, building speed, until gravity took over and the hill pulled faster than the push, and hands disappeared from your back, and you were released, hovering over the snow, cold air in your ears, tang of blood on the tongue from a chapped lip, mittens gripping the handles, the high-pitched purr of rubber on snow, snow that had been packed by ride after ride, it was you and the movement, and it never felt crazy to cry out, there by yourself, going faster and faster, in your own private moment of fear and glee. Is that what made the lunatics yell inside their white-walled cells? Some same combination of soaring down a mountainside unstoppable, I’m happy, I’m afraid, I feel too much, I have to let it out? So we surrender. “This is the Hour of Lead—” writes Emily Dickinson:

Remembered, if outlived,

As Freezing persons, recollect the Snow—

First—Chill—then Stupor—then the letting go—

The walk back up the hill took a while, we’d be panting, ready to shed a layer, and the brick buildings of the hospital loomed into view near the top, bars on all the windows. The hospital was closed in 2003, all the windows boarded up with wood painted red. I can feel right now the hands disappearing from my shoulder blades. And I can hear the sound of the alarm when someone escaped from the hospital. Not the blaring tin of a car alarm or wheeeuuuu whirl of an ambulance or clattering clang of grade school fire drill. More foghorn, deep, soul-stilling moan, as though the bulkhead door to the basement of Hell was being pried open again and again.

One of the snowiest albums I know bows to Dickinson and her letting-go lines. The energy of The Letting Go, the 2006 record by Bonnie “Prince” Billy, is the energy of being in the woods as light fades, some hut somewhere in the distance with a glowing hearth to find—but will you find it, or lose your way in the swirl of snow? On that wintery album, the song “Then the Letting Go” is the wintriest of all, a duet dialogue between Will Oldham and the snow-wraith-voiced Dawn McCarthy. It begins in innocence:

There was someone a long time age

(Come follow me here and then we’ll go)

Who played with me whenever it snowed

A snow-based companionship brings to mind what poet Mary Ruefle wrote: “Every time it starts to snow, I would like to have sex … I would like to stop whatever manifestation of life I am engaged in and have sex, with the same person, who also sees the snow and heeds it.” Snow as ultimatum, as signal, you and I, our time. Ruefle’s poem closes with union: “when it snows like this I feel the whole world has joined me in isolation and silence.” A different sort of joining happens at the end of Oldham’s song. His companion returns after a long absence, lays her wet head on his feet, says nothing, and falls asleep. The song ends:

In the quiet of day, well, I laid her low

(You a fire, me aglow)

And used her skin as my skin to go out in the snow

In winter, we get inside each other. The erotics of the dark, cold season differ from that of summer—not the flirty, sundressed frolic, not sultry August sweat above the lip, not tan lines or sand in shoes or voluptuous tulips. It’s a different sort of smolder now. Quilted, clutching, we wolve for one another, ice on the puddles and orange glow from windows against deepest evening blue. In summer: lust and laze, days are loose and lasting. In winter: time tightens, night’s wide open, the hunger says right now. In winter: the flash of wet light reflected in another’s eye, close to yours, half closed in the dim. That eye shining in the dark, that blurred wet glaze and shine, everything else in shadow, form and heat, that light for a flash as lid closes or head shifts, that is a mysterious and singular light. That is the burning animal inside trying to run through the walls of its pen. I see in that flash the burning animal inside you. I feel my own there, too. This winter feels not like the rest. It’s not ease that drives us in these dark days, but fear. The dark and the cold settle at the back of your skull and tell you secrets of the longer, longest, endless dark and cold to come. Grip tight, press hard. Such is winter love.

We’re one week away from the solstice and until then, darkness will inhale a little more light each day. But its lungs are filling. It’ll take twenty-six seconds of light today, twenty-two tomorrow, shallower pulls until it can take in less than one second on the solstice itself. Remember: winter hasn’t even started yet. Has it snowed where you are? Did you sled as a child? Do you remember the last time you sled? Winter invites a turning in, a quieting, an upped interiority, but this time around we’re coming on months of it already—will we be able to find our way back out? Time will tell. For now, here we are. An assertion—a reminder—of aliveness. Or as Issa puts it:

Here,

I’m here—

the snow falling.

The snow falling. Here, falling, crystal quiet. It’s a quiet that’s captured in the documentary Into Great Silence, about a Carthusian monastery in the French Alps. The film is close to three hours long; there are almost no words. The camera focuses on a large farmhouse sink. The light that washes in through the window is snow light. A large metal mixing bowl tilts to dry. The camera closes in. A droplet collects on the lip of the bowl. It swells. It rides the ridge down and hangs off the edge of the bowl. It is white and blue and gray, a translucence, a fluidity. The tension begins to build. You come to know, with a startling amount of pain, at some point this drop will fall. It will drop to the basin and splash into hundreds of tinier drops. When will it fall? The suspense becomes awful. You want it to fall, to relieve you, to let you feel like you can take a full breath again. But also, look at how beautiful it is, the pearl bottom, its perfect, uncorrupted smoothness. A shape that takes on the feel of time. With its beauty comes the agitation, the confusion, the uncomfortable suspense of its end. And you want it to end, drop, please. And you want it to last forever, to swell and swell so it spills through the screen, absorbs you into it, swallows the whole world, warm and full, with space enough for everything and light like no other light. The drop hangs between its two intervals, its accumulation and its end.

It falls. Something inside collapses. On the lip of the large metal bowl, another drop takes form. Tiny drops collect to make a larger drop, together in isolation and silence. Like the monks of this monastery who devote their time on this earth to prayer.

“The primary application of vocation is to give ourselves to the silence and solitude of the cell,” states Carthusian Statute 4.1. Not every moment though. The film shows one wrenching, beautiful scene: a group of the monks on the mountain, eight of them, white-robed figures ascending a steep and snowy hillside, stony crags above them, camera at a distance, we see human forms but not faces. A meditative stroll, maybe. Get the blood moving in the winter months. But look, two monks sit down and slide down the sweep of mountain! And then more, some sitting, some skidding down on their feet, two almost crash into each other, they tumble, roll down the hill in the snow in their white robes. Down they go! And all you hear is their laughter and their whoops. Crying out as they pick up speed, the child in all of us, hands letting go.

Today, in the city where I live, there are nine hours, six minutes, and seven seconds of daylight. Sunset lasts all day. Pressing old December dark sweeps its way across the city. It sweeps its way across the river, the forests, the towns with their driveways and church parking lots, the silent ponds, the mountains, the wide flat fields, the hills, the hospitals. Cry out. Cry out! We’re hurtling down the hill, and there isn’t any stopping. Cry out, it is not lunatic, not right now. In wild joy, in thrashing pleasure, in heaving grief, in fear, in all of it at once. Small drops, all of us, slipping down the lip of a bowl.

Read Nina MacLaughlin’s series on Summer Solstice, Dawn, Sky Gazing, and November.

Nina MacLaughlin is a writer in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Her most recent book is Summer Solstice.

The Art of Distance No. 37

In March, The Paris Review launched The Art of Distance, a newsletter highlighting unlocked archive pieces that resonate with the staff of the magazine, quarantine-appropriate writing on the Daily, resources from our peer organizations, and more. Read Emily Nemens’s introductory letter here, and find the latest unlocked archive selections below.

“ ’Tis the season of gift giving. Whether you celebrate Hanukkah, Christmas, something else, or nothing in particular, you’re probably finding yourself engaged this month in the process of wrapping and unwrapping presents. For some, gift wrapping is an exercise in achievable perfection—neat corners, perfect creases, tasteful bits of tape in all the right places, a gorgeously appointed bow to top it off. For others (I include myself in this group), it is torture, a comedy of errors that begins with forgetting to measure before cutting the wrapping paper and ends with a finished gift that looks like a lumpy quilt sewn by a baby. But it’s the thought that counts, right? Below, you will find many such thoughts in a series of stories and poems that touch upon the gift-giving season. Read on for fantastical presents, perfect presents, and wrapping disasters. These are gifts that keep on giving, and there is something, I hope, for everyone. Speaking of the gift that keeps on giving, I would be remiss if I didn’t mention that a subscription to The Paris Review (for yourself or someone else) and TPR merchandise also make great gifts, and while it may be too late to deliver them by Christmas, we have this elegant gift card that you can print out and put under the tree—or wherever you lay your gifts. Happy holidays, happy reading, and stay safe.” —Craig Morgan Teicher, Digital Director

Photo: Tomasz Sienicki. CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...), via Wikimedia Commons.

Joel Stein’s poem “A Gift for You” offers some things that everyone needs but that are very difficult to give.

Andrew Martin’s “With the Christopher Kids” is about, among other things, the trials and tribulations of gift wrapping—“I need paper, tape, and scissors.” Things get more challenging from there.

Ben Okri’s “The Dream-Vendor’s August” only glances at the season of gift giving, but that may be enough for many of us, and what could be a better gift than the correspondence course in this story, which promises to show students how to “Turn Life into Money”?

The narrator of Stephen Dixon’s story “Gifts” goes a bit over the top with his giving …

What’s given in Roberto Bolaño’s poem “My Gift to You” is unusual—“an instant of emptiness and joy”—but is, perhaps, the kind of gift one would expect from a poet.

Finally, I’ll leave you with Susan Stewart’s poem “Pine,” with its hauntingly beautiful image of “The Christmas tree, nude and fragrant, / propped as pure potential in / the corner with no nostalgia for / ornament or angels.”

Sign up here to receive a fresh installment of The Art of Distance in your inbox every Monday .

December 11, 2020

Staff Picks: Monsters, Monarchs, and Mutinies

Still from Symbiopsychotaxiplasm Take One. Courtesy of the Criterion Collection.

There’s a gently anarchic spirit to William Greaves’s 1968 experimental documentary Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One, which follows Greaves and his crew as they attempt to film two actors staging a breakup scene in Central Park. This description barely scratches the surface of what’s really going on: Greaves himself is playing a role, that of the bumbling director—but he’s the only one in on it. The script is melodramatic; the actors—mostly a middle-class white couple, but other actors of different ages, backgrounds, and races are swapped in and out—overact; the crew—instructed to always have three cameras going, on the scene, the crew, and the park itself—stages a mutiny. Unbeknownst to Greaves, they film their grievances and critiques and present them to him once it’s all over (these make up three major sections of the movie). As one crew member remarks, this is a movie about power. But as it turns out, that was the conceit all along: at one point, Greaves explains that he was hoping they’d call him out on the bad script and provide some lines of their own. (The edits suggested by one crew member are equally terrible, to my ears, but in a kind of charmingly sixties way clearly born out of the sexual revolution.) Toward the end, they stumble across a man who claims to be homeless and living in the park; the last vestiges of an old New York bohemianism, he gives a flamboyant speech about all that’s wrong with the world. As I watched the crew wander again through the park while the credits rolled, something reminded me of A Midsummer Night’s Dream—a merry band of revelers, role reversals, the breakdown of hierarchies, that summertime feeling of possibility. Immediately, I queued up Greaves’s 2005 follow-up: Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take 2 1/2. —Rhian Sasseen

Earlier this year, I discovered Lindsay magazine, and I’ve been making my way through their backlog ever since. Lindsay’s articles are rooted in culture and place, so reading from their global contributors feels like something resembling travel. I’ve absconded into stories about free diving in Australia and mud-brick buildings in Morocco, recipes from Lebanon. This week I’ve been thinking about the magazine’s 2019 interview with the writer Sisonke Msimang. Stories, in Msimang’s experience, are transformative, and the telling of them creates intimacy, community. But still, she says, they are insufficient. There is no call to action in stories, so while they can be a tool for social change, they are not the change themselves. It felt potent to read this now, as I try to come to new understandings about stories and what they can do, and writers and what they feel like they have to do. She says she no longer calls herself an activist, just a writer, and others fill in the rest on her behalf. Beyond the burden of those labels, self-imposed or otherwise, Msimang finds freedom: “This helps storytellers to not feel the burden of people’s expectations and it also helps us to not have big egos. My story is just the story I’m going to tell and people may or may not do something with it.” There’s an agency here for the writer but also the reader: there is no call to action, but there is always the choice. —Langa Chinyoka

Still from the video game Risk of Rain 2. Courtesy of Hopoo Games.

I’ve barely been able to tear myself away from the ever-shifting alien terrains and howling electric guitars of Risk of Rain 2. In this indie game, you play as an astronaut trying to survive an endless onslaught of monsters and scrambling to escape an increasingly hostile world. As you collect items, unlock new characters, and advance the difficulty progression of the game merely by existing, you will die repeatedly. But when you don’t die, you’ll get into a groove: your fights start lining up perfectly, too perfectly. Instead of feeling the jumpy anxiety of the first few areas, you’ll start rampaging through all of these creatures thoughtlessly. And odds are, it’ll be incredibly satisfying. But then one of two things must eventually happen: you will die, or you will win, and flee this dying world. In death, you’re left with the emptiness of what could have been; you once held so much power, but now you’re forced to start from zero once more. If you win, though, the tainted lens of the game falls away to reveal something more sinister—how, in succeeding, you have become the invading force of this world, the extraterrestrial destroying everything in its path. But the game has continued to pull me back in because before the emotional vacuum of either outcome, there’s the romp of getting there. After all this fighting that is routine in many video games, Risk of Rain 2 makes you look back on why you enjoy it, all while indulging you time and again. —Carlos Zayas-Pons

I got into Dirty Projectors through my record-of-the-month club, which sent me a lovely double-vinyl reissue of the band’s seminal Bitte Orca on clear LPs with swirls of red and blue. They were yet another band from the aughts that I missed because I was looking the other way, but I was instantly hooked by David Longstreth’s wiry and willowy and wandering guitar work, the dynamic ups and downs of his songwriting, and the band’s utilization of various male and female vocalists. Their new record, 5EPs (first released separately over the course of 2020 and now collected as an album), features five sets of four songs sung by different band members. Each set has its own mood and sound. My favorite is the first, Windows Open, sung by Maia Friedman, which includes “Overlord,” a catchy and sparely arranged pop song that is to die for. For some reason my family’s puppy, Cashew, hates the second group, entitled Flight Tower—she barks and whines through all four songs. There must be some supersonic overtone in Felicia Douglass’s voice that I can’t detect; I think it’s lovely. Overall, these twenty songs are lighter fare than the band’s previous albums, but playing through all of them, I feel a sense of renewal, as if the seasons are changing with each EP. I’m pretty desperate for renewal these days, so I’m a fan. —Craig Morgan Teicher

We seem to love television that catches the wave of the twentieth century, the way history serves to bolster and electrify the lived banality of ad men and affectless monarchs. Derry Girls, an Irish show about a group of teenagers (four girls and one haplessly misplaced English boy) in Northern Ireland during the nineties, rejects any easy metaphors. In season 2, Erin Quinn—a stand-in for the show’s creator, Lisa McGee—writes a hokey poem that she explains is “about the Troubles, in a political sense, but also about my own troubles, in a personal sense,” to which her teacher flatly responds, “I understand the weak analogy.” Instead of becoming entangled, the foibles of everyday life separate from civil conflict like water from oil, allowing characters to maneuver underneath the fire. Unrest is sometimes literally a backdrop, TV news playing as the Quinn family hypothesizes that Gerry Adams’s voice has to be censored because it’s too “seductive” for the English (“apparently he sounds like a West Belfast Bond”) and comments that John Hume is “really dyin’ for peace-like, isn’t he? It’s all he ever goes on about. I hope it works out for him.” A plot to get after-school jobs spirals into the staging of an IRA robbery, which results in a lifetime ban from their favorite chip shop; an integration youth program, Friends across the Barricade, is an opportunity to make out with (Protestant) boys. Derry Girls skirts flippancy—season 1 wraps with a moment of sweetly deployed poignancy—but articulates with sharp wit how to live, happily, in an abnormal normal. —Lauren Kane

Still from Derry Girls.

The Politics of Louise Fitzhugh

In the autumn of 1974, one month shy of the publication of her new novel, Nobody’s Family Is Going to Change, Louise Fitzhugh pulled the emergency brake. Authors rarely invoke such a costly and disruptive eleventh-hour freeze, but Fitzhugh persuaded her publishers at Farrar, Straus and Giroux that her book about a Black family in New York City was incomplete.

Stopping the presses is a rare request for any author, but for Fitzhugh, the forty-six-year-old writer of the wildly popular children’s book Harriet the Spy, it was a radical measure entirely in keeping with her practice of telling the truth about children. When Fitzhugh said that she wrote for kids in order to do something good in “this lousy world,” she meant, this misogynist, racist, and homophobic one. As a writer of books for young readers, Fitzhugh wasn’t interested in fairy tales. Nor did she want her newest novel to simply reflect reality, she wanted her readers to be confronted and shocked by the undiluted fact that children were murdered by the police because they were Black in America.

Eighteen months earlier, in April 1973, Fitzhugh had been drafting a version of Nobody’s Family Is Going to Change when she read on the front page of Sunday’s New York Times that Clifford Glover, a ten-year-old Black child, had been shot in the back by a plainclothes police officer in Jamaica, Queens. Fitzhugh saw such incidents of unchecked police brutality as a nauseating throwback to the systemic racial violence of her youth in segregated Memphis, Tennessee. Born to a wealthy family in 1928, Fitzhugh would come to repudiate the white supremacist world of her childhood. By 1950, she’d settled in Greenwich Village. As a young lesbian artist, her first response to just about any assertion of supremacy—white, male, heterosexual, abstract expressionist, or just garden-variety pomposity—was typically to oppose it.

According to the news reports, Clifford Glover sometimes accompanied his stepfather, Add Armstead, to a local auto salvage yard where Add worked and Clifford—who was five feet tall and weighed ninety pounds—helped run errands. Clifford even had his own little wrench, perfectly sized for his fourth-grader’s hand. Soon after dawn on April 27, 1973, two white undercover cops, Thomas Shea and Walter Scott, jumped out of an unmarked Buick Skylark with guns drawn. As one of the police shouted, “You Black sons of bitches!” Clifford and Add ran. Officer Shea followed Clifford and shot three bullets into the little boy’s back, murdering him. Standing above the dead child, Officer Scott was heard exulting into his walkie-talkie, “Die, you little bastard!”

During the subsequent investigation and trial for homicide, Officer Shea insisted that he had seen a revolver in Clifford’s hand. “I was very, very scared,” he said.

Shea’s acquittal in June 1973, was followed by days of protests in Jamaica, Queens. When Fitzhugh learned Shea had been found not guilty, she wanted to use her power as a writer with a large audience to say and do something meaningful. At the time, she was still working on the final revisions for Nobody’s Family Is Going to Change. She wanted people to remember Clifford Glover, and to incorporate his name into her novel, but she wasn’t yet sure how.

Nobody’s Family Is Going to Change is set in the same Uptown Manhattan milieu as Harriet the Spy. It’s about a Black, middle-class family divided by competing perceptions of art and status. The brilliant, cantankerous, eleven-year-old heroine Emancipation (Emma) Sheridan considers her father a “male chauvinist pig,” and shouts things like, “I’m sick of male images, armies, uniforms, salutes kowtowing. I’m sick of males altogether.” Emma joins a secret revolutionary Children’s Army whose salute—given with a raised fist—is “children first.” The Children’s Army’s organizing principle is rescuing children from “stupid” adults whose actions, whether through ignorance or malice, put children in harm’s way.

A year and a half after Clifford Glover’s murder and Thomas Shea’s acquittal, when Nobody’s Family Is Going to Change was almost at the press, Fitzhugh learned of yet another senseless and racially charged murder of a Black teenager. On September 15, 1974, in Brownsville, Brooklyn, fourteen-year-old Claude Reese had been decorating a basement for a friend’s birthday party when NYPD officer Frank Bosco charged in, ostensibly following a suspect. Claude Reese ran away into a nearby courtyard, where Bosco shot him in the head. Bosco later claimed he mistook the handsaw Claude Reese was holding for a gun. After an internal investigation, Bosco was suspended and made to surrender his weapon, but he remained on the force.

The month after Claude Reese’s murder, as protests demanding justice erupted in and around Brooklyn, Fitzhugh decided that it was time to make her views, which had always been implied in her novels, explicit. She stopped production to add a paragraph to memorialize the names of Clifford Glover and Claude Reese.

As eleven-year-old Emma Sheridan enters an empty warehouse in an alley off Seventy-Ninth Street, she finds an enormous room where hundreds of kids are milling around. Harrison Carter, the teenage leader of the Children’s Army, begins the meeting with the new invocation that Fitzhugh stopped the presses to insert:

“The first thing today is a minute of silence in memory of two innocent victims, Clifford Glover and Claude Reese, shot down in the streets by policemen when they were only ten and fourteen.”

“We will never forget.”

Fitzhugh didn’t join street protests, but her books had broad commercial reach and the potential to shape social consciousness. She would not live to see if her finished book had the desired effect. She died suddenly from an aneurysm, just a week before Nobody’s Family Is Going to Change was published. Her novel was met with mixed notices, and not a single reviewer mentioned the two murdered youngsters.

About four years after Fitzhugh’s death, Audre Lord published a poem about Clifford Glover, in which Lord declares she is “trying to make power out of hatred and destruction.” For years, the intertwining stories of Clifford Glover and Claude Reese have ebbed and flowed beneath the surface. It’s not hard to imagine a version of young Emma Sheridan today, in the streets, still demanding action against the murder of so many schoolchildren, still demanding that we say their names.

Leslie Brody is the author of the biography Sometimes You Have to Lie: The Life and Times of Louise Fitzhugh, Renegade Author of Harriet the Spy, and other books. She lives in Redlands, California.

Freedom Came in Cycles

Pamela Sneed. Photo: Patricia Silva.

Uncle Vernon was cool, tall, hazel-eyed, and brown-skinned. He dressed in the latest fashions and wore leather long after the sixties. Of all of my father’s three brothers, Vernon was the artist—a painter and photographer in a decidedly nonartistic family. To demonstrate his flair for the dramatic and avant-garde, his apartment was stylishly decorated. It showcased a faux brown suede, crushed velvet couch with square rectangular pieces that sectioned off like geography, accentuated by a round glass coffee table with decorative steel legs. It was pulled together by a large seventies organizer and stereo that nearly covered the length of an entire wall. As a final touch, dangling from the shelves was a small collection of antique long-legged dolls. This was my uncle and memories of his apartment were never so clear as the day I headed there with my first boyfriend, Shaun Lyle.

It was the eighties, late spring, the year king of soul Luther Vandross debuted his blockbuster album, Never Too Much, with moving songs about love. If ever there was a moment in my life that I felt free, unsaddled by life’s burdens, and experienced, in the words of an old cliché, “winds of possibility,” it had to be the time with Shaun Lyle heading upstairs to my uncle’s house as Luther Vandross blared soulfully out from the stereo, “A house is not a home.”

Of course Shaun was not the first or last person with whom I’d experienced feelings or sensations of unbridled freedom. Like seasons, freedom came in cycles, like in fall, in college with no money, chumming around with my best friend and school buddy Michael. We spent late afternoons wandering Manhattan’s East and West Village, searching for cheap drinks and pizza at happy hour specials, ecstatic in our poverty. Michael was a blond Irish Catholic punk rocker from Boston. We met when I was an RA at the New School’s Thirty-Fourth Street dorms at the YMCA. They were narrow, tiny rooms like closets and some floors served as a hostel for homeless men. Punk music blared from Michael’s room. I would knock on the door, commanding, “Turn it down.” Eventually, we united over the fact that he put a towel under the door to block the smell of weed smoke that frequently leaked from his room into the hallway. Michael and I were both writers, astute critics, and teacher’s pets. In fiction-writing class, we formed a power block. No piece of writing done by another student escaped our scathing critique. Professors deferred to us. “Michael, Pamela, what do you think?” We sat next to each other with arms crossed. A friend confessed to me later, “I was terrified of you two.” We were obsessed with Toni Morrison. I will never forget the last lines of Toni Morrison’s novel Sula, which Jane Lazarre, our fiction teacher, made us read out loud as a class together.

Suddenly Nel stopped. Her eye twitched and burned a little. “Sula?” she whispered, gazing at the tops of the trees. “Sula?” Leaves stirred; mud shifted; there was the smell of overripe green things. A soft ball of fur broke and scattered like dandelion spores in the breeze. “All that time, all that time, I thought I was missing Jude.” And the loss pressed down on her chest and came up into her throat. “We was girls together,” she said as though explaining something. “O Lord, Sula,” she cried, “girl, girl, girlgirlgirl.” It was a fine cry—loud and long—but it had no bottom and it had no top, just circles and circles of sorrow.

Jane’s eyes welled up, as did mine, and the whole class cried. Sula is the story of women bonding and friendship and longing and loss. “It’s a truly feminist novel,” Jane would declare. Feminism was her favorite topic. She was a straight woman with kids. She had gray hair and admitted she smoked pot. She was so cool, she’d write things on the board and say out loud, “Oh, I can’t spell.”

Michael and I were both work-study students. We covered for each other. He would call me after a night of drinking and partying and say, “I just can’t do it. I can’t go in. Will you go?”

“Sure,” I’d say.

One day Michael and I skipped school and hung out near the entrance of Seventy-Second Street and Central Park West. I stared at a figure across the street in a café. “There she is,” I said.

“Who?” Michael asked.

“Toni Morrison, and beside her is June Jordan,” I said.

“You’re crazy,” he said. “No way. That can’t be them. How can you see that?”

“Yes, it is.” We investigated. Sure enough, sitting beside a low fence of the café was Toni Morrison with June Jordan in dark sunglasses. I approached. Michael lagged behind, astonished. “I love your work, Ms. Morrison,” I said. At the time I wasn’t such a huge fan of June Jordan. I’m not sure if the reason I disliked her had to do with the fact that she had tried to pick up my girlfriend Cheryl while visiting/lecturing at the New School, or perhaps I wasn’t ready for her message. Knowing what I know now—if only I could go back through time and tell her how much it meant for me to hear her in person. Long after she would die of cancer and write the words in dialect “G’wan, G’wan!” telling us, a new generation, to go on. Long before the collapse of the twin towers, before the massacre of so many gay men from AIDS, wars against Brown bodies in Iraq, Harlem, and Afghanistan, before the growing epidemics of cancer, rape, police violence, domestic violence, mass incarceration, depression, demise of our pop stars, she said to a class at the New School, speaking of the U.S. in the true form of a prophet: “This country needs a revolution.”

Maybe it was June Jordan, like Audre Lorde, who taught me the power of what words could do. In retrospect, she opened the doors and flung open the windows to my consciousness, like when I heard Maya Angelou’s poem “Still I Rise” when I was nine years old. It awakened me. Just recently, with the terrible results of the 2016 presidential election, with Donald Trump elected, I could see June Jordan in sweet, smiling profile, reciting, as resistance, “Poem about My Rights.”

The poet, professor, and performer Pamela Sneed is the author of Sweet Dreams, Kong, and Imagine Being More Afraid of Freedom than Slavery. She was a visiting critic at Yale and at Columbia University’s School of the Arts, and she is online faculty at Chicago’s School of the Art Institute teaching human rights and writing. She also teaches new genres at Columbia’s School of the Arts in the Visual Dept. Her work is widely anthologized and appears in Nikki Giovanni’s The 100 Best African American Poems. She has performed at the Whitney Museum, Brooklyn Museum, MoMA, Poetry Project, New York University, Pratt Institute, Smack Mellon Gallery, the High Line, Performa, Danspace Project, Performance Space, Joe’s Pub, the Public Theater, SMFA, and BRIC. She lives in Brooklyn, New York.

Reprinted from Funeral Diva , by Pamela Sneed, with permission from City Lights.

December 10, 2020

Clarice Lispector: Madame of the Void

Clarice Lispector with her dog Ulisses and some chickens. Rio de Janeiro, 1976. [Lêdo Ivo Collection / Instituto Moreira Salles]

Translator’s Note:Today marks the one hundredth anniversary of the birth of iconic Brazilian writer Clarice Lispector, born on December 10, 1920, in the Ukranian village of Chechelnik, where her family had stopped while fleeing the nightmarish violence of the pogroms in the wake of the Russian Revolution. After a long journey through Europe, the refugees arrived in northeastern Brazil in 1922, where most of them adopted new Brazilian names; the youngest daughter, Chaya, meaning “life” in Hebrew, became Clarice.

I wanted to share the following essay as a tribute to Clarice on her birthday, and an offering to her growing number of readers outside Brazil. My translation is a shortened version of a piece originally published in 1999 by Brazilian journalist and writer José Castello, in his essay collection Inventário das sombras (Inventory of Shadows). I first read it a few years ago at the New York Public Library, while tracking down the source of a quote that has circulated vigorously in Claricean circles: “Be careful with Clarice. It’s not literature. It’s witchcraft.” I had been fact-checking my own essay about translating Lispector’s Complete Stories and was surprised, and delighted, to discover that Castello was the source of several well-known anecdotes from the lore surrounding Clarice (as she’s known in Brazil).

The tender and comical first half of the essay recounts the young journalist’s awkward encounters with the famous writer in the seventies, which reads like a horribly botched series of Paris Review Art of Fiction interviews. Nevertheless, Castello’s vivid memories of Clarice give wonderful insights into a writer associated with so much mystery.

The second half of the essay unfolds in the nineties, nearly twenty years after the writer’s death, of ovarian cancer on December 9, 1977. I find it most compelling for the way it threads crucial questions about her work through encounters with some of her most devoted readers: What is it that Clarice wrote? Is it literature, or does it partake of some other force, whether witchcraft or philosophy, connected to her singular talent for turning language inside out, as the French feminist theorist Hélène Cixous asserts? Why does Clarice inspire a kind of mutual possession with her reader?

Translating Castello’s recollections another twenty years later, amid the recent wave of Lispectormania, I am struck by how they can offer new readers a sense of solidarity with earlier generations as they figure out how to approach this daunting yet spellbinding writer. The girl on the bus at the end of the essay recalls Clarice’s observation, in her only televised interview, that a high school literature teacher said he couldn’t understand The Passion According to G.H. even after reading it four times, while a seventeen-year-old girl shared that it was her favorite book. “I suppose that understanding isn’t a question of intelligence but rather of feeling, and of entering into contact,” the writer concluded. The episodes that follow raise the prospect that the best way to read Clarice is to live her.

—Katrina Dodson

Rio de Janeiro, November, 1974. At the age of twenty-three, just embarking on my career as a journalist, I secretly start trying my hand at fiction. Painstaking exercises, in which I progress at a faltering pace, unsure of what direction to take.

During this time, there’s a book I can’t stop reading: The Passion According to G.H., by Clarice Lispector. I discovered it one day by chance on my sister’s bookshelf. I started reading without much conviction and was immediately jolted by its tumultuous, agonizing spirit. I pushed on. I couldn’t put it down.

Attempting to unite the two experiences, I mail one of the short pieces I’ve just written—no more than a confession, really—to Clarice Lispector’s apartment in the Leme neighborhood. I include my address and phone number, in the hopes that someday she might respond. Days go by, and my hope fades. I go back to G.H.

*

Christmas Eve. The phone rings and a low, raspy voce identifies itself. “Clarrrice Lispectorrr,” it says. She gets right to the point. “I’m calling to talk about your story,” she proceeds. The voice, faltering at first, now grows firm: “I have just one thing to say: you are a very fearrrful man”—and the r’s of that “fearrrful” claw at my memory to this day. The deafening silence that follows leads me to believe that Clarice has hung up the phone without even saying goodbye. But then her voice reemerges: “You are very fearrrful. And no one can write in fear.”

Afterward, Clarice wishes me a Merry Christmas—and her voice sounds far away, indifferent, like an ad on TV. “You too, ma’am,” I say, dragging out my words, which catch in my throat, lacking the courage to make their way out. Then comes another silence, and again I think she’s hung up. Betraying the full extent of my fear, I say, “Hello?” Clarice is laconic: “Why are you saying hello? I’m still here, and you don’t say hello right in the middle of a conversation.”

We have nothing else to say to each other, and she says goodbye. It was a quick call, but left me with a series of intimate after-effects that even now, more than twenty years later, I still haven’t fully digested. I could say, just to feel sorry for myself, that she paralyzed me. I could say the opposite: that she helped me access something I hadn’t known. To this day, I cannot write—articles, personal letters, travelogues, fiction, biographies—without thinking of Clarice Lispector. It’s as if she’s looking over my shoulder, repeating her warning, “No one can write in fear…”

*

May, 1976. Word spreads through the newsroom of O Globo, the newspaper I write for, that Clarice Lispector has decided she’ll never talk to the press again. Reason enough to assign me an interview with her. Journalists have a boundless attraction to obstacles; we’re constantly trying to get past roadblocks, open doors, cross borders, wear down all forms of resistance. That’s not my natural temperament, but it’s a practice the profession has required me to hone.

Reluctantly, I call Clarice. A voice asks me to hold on a moment, but yet again, I must face a long silence. Finally, Clarice comes to the phone. Absolutely certain I’m intruding on her, I state my request and await her refusal. To my surprise, Clarice agrees to see me.

I arrive at the building where Clarice Lispector lives, on Rua Gustavo Sampaio in Leme, and identify myself. I still have that feeling of being an invader. A white-haired man seated at the reception desk asks me, looking annoyed, “Where are you going?” I say the apartment number Clarice gave me on the phone. He hesitates. Then starts leafing through a black notebook, darts a sidelong glance at me, and says nothing else.

“I have an appointment,” I insist. “She’s expecting me.” The doorman looks at me again. I get the feeling, however, that his thoughts are elsewhere, that he’s moving just to cover up what he’s thinking. He clears his throat, shuts the notebook, and says, “Dona Clarice’s not home.” And because my surprise makes him jumpy, he adds, “She just left. Something came up.”

I decide I’m not giving up. As if time is breaking down, my mind replays every step of the path I took to get here. I discovered Clarice by chance. I made it through G.H., always on the verge of giving up, then ultimately finding what I hadn’t been seeking. No way was this doorman taking away what was now mine.

I put my foot down: “But she promised she’d be home. Can’t you ask again, sir?” The man draws me back into his weariness, and, lowering his voice, tells me, “Dona Clarice’s home, but she asked me to say she’s not.” He seems genuinely relieved to tell the truth.

I ask him to try just once more. The doorman picks up the intercom phone, presses a button, then says, “Dona Clarice, it’s that young man. He insists on going up.” Another contradiction: Clarice, without further discussion, grants me permission to go up. Maybe she wanted to test my determination.

As I step into the elevator, the light seems dim, and I imagine some kind of electrical glitch. The elevator moves at an unusual speed, as if it could give out at any moment and start moving sideways instead of up, repeating a nightmare that haunted my childhood. I peer at myself in a mirror—my image appears fluid; what I see doesn’t resemble a reflection, so much as a shadow. All right, I’m scared.

Fleeting, outlandish scenarios seize my imagination. Clarice could call the police. She could snap and start hurling insults at me, thus shattering my image of the brilliant writer. Afterward, I’d reluctantly write an article full of disappointment. Maybe it was better to turn back and save her from what was about to happen. But I knew that wasn’t it. Clarice led me down a path I hadn’t expected to find, but now there I was, letting the road drag me onward. She knew the whole truth.

Still in the elevator, I rehearse the words I should say to flatter her, but when she opens her apartment door, I go mute. Once again I encounter an immense silence, which is now inside me. I see a woman in a turban, barely dressed, almost letting herself go. Her lipstick is outrageous, veering past her lip line. Her skin is pale and sickly, milk-white, as if faded. She’s a tall woman, or at least she looks down at me. She’s standing there, waiting for me to say something.

I say, “We have an appointment.” She answers, “I told the doorman not to let anyone up herrre,” and there is that voice from the phone, now incarnated into a woman, dragging its tail made of r’s. “But, since you’ve come up…,” she corrects herself, and here comes another silence, ending in: “Come in, then.” It isn’t a choice, apparently. She doesn’t want to get upset, doesn’t have the energy to fight, so she’s decided to see me. I come in.

Clarice seems to inhabit another sphere, one situated beyond the human, as if the person standing here is represented only by a mask. She takes me into a stifling living room with questionably modern furniture and a jumbled group of paintings on the walls. It dawns on me that several of them are portraits of the writer signed by renowned painters. I feel like I’m in a museum and wonder whether Clarice herself is a painter, too. She points to a couch and says, “So you want an interview.” Well, that’s the excuse.

“Yes, an interview,” I reply, certain that she’s starting to understand. Clarice studies me ever so slowly, trying to locate in me, perhaps, some sign that she can trust what I say. Seemingly satisfied, she remarks, “Well, you’re here now.” But immediately after, she gently delivers a blow: “So you’re the author of that story.” The “author” here is her; I’m just a reporter, so this observation shocks me. Still, puffed up with pride, I say yes. “It’s me.” There I am, trying to take her observation as a compliment, when she smites me down: “I didn’t like your story. You’re too fearful to be a writer.”

We sit. I try to recover from the blow by turning back to my questions. I pull a small tape recorder from my briefcase and absentmindedly set it on the coffee table. As soon as she sees it, Clarice starts screaming. “Ah, ah, ah!” She’s letting out these long wailing cries, stripped of all meaning, and I can only make out one word: “No.” My eyes race around the room looking for the threat she’s trying to get away from. I can’t find it.

Clarice gets up and paces around the room. Looking for a way out but not finding it, she starts wailing even louder. “Ah, ah, ah!” she goes on, and I stare at her. I’m determined to find the source of that scream—what if the living room is being invaded by some stranger or a fire has broken out somewhere—some sign of tragedy to which it might correspond. I don’t see a thing. Clarice keeps screaming in circles in a senseless dance, arms flailing like propellers, flung about by some invisible wind, her face a wreck. “What’s wrong?” I shout. She can’t respond.

A woman appears in the living room from who knows where and throws her arms around Clarice. An ambiguous embrace that’s simultaneously a forceful blow, like those feints boxers use to shut down their opponents. They remain in this embrace a long time. Then getting hold of herself, Clarice points at the tape recorder. “Get it out of here!” she says, finally. “I don’t want that here!” She reaches out her arms, and her hands start writhing, wanting to grab while also trying to flee. Her eyes, more beautiful than ever, are seasick with despair.

“Get it away right now.” I look at my poor tape recorder, a beat-up, unreliable machine, and I still don’t get it. “What do you mean, it?” I ask. The other woman answers, still hugging Clarice, sounding like a nurse, “My friend is referring to your tape recorder. Put it away, please.” I move toward it, but Clarice acts first and commands, “Here, give it to me.” Without thinking, I hand her the recorder. She holds it by her fingertips, full of disgust, and pauses for a few seconds, controlling her breath. Then she turns and disappears down a dark hallway, followed by the woman.

I sit there alone in the living room, across from those walls full of paintings, full of Clarices watching me, wondering what I’m supposed to do. Do I leave without saying goodbye? Do I wait patiently for her to return? Do I follow them? I’m still weighing these options, all of which seem useless, when Clarice returns empty-handed. “Now we can talk,” she says in a milder tone, adding, “I’ll give that back to you at the end of the interview.” Rarely have I heard a word as monstrous as her “that.”

Calmer now, she finally manages to notice that I’m shaken up, too. “I locked it in my closet,” she says, showing off the key with a triumphant look that reminds me of those photographs of hunters next to their victims. And in that bureaucratic voice of doormen and receptionists, she adds, “Don’t worry. I’ll return it on your way out.” She signals she’s ready to chat. “Well then?” she says, indicating that she’s waiting for my barrage of questions.

She sits. Unsure of myself, I decide to start the conversation with general topics. Classic, impersonal questions that will open the door to any kind of answer, mere civilities disguised as real questions.

The interview is tense, full of suspicion and misunderstandings. Unable to forget her screams, and unable to think straight, I ask questions like an amateur. Clarice tries to be patient, but answers in terse phrases, clearly in a bad mood. The conversation goes nowhere. I know that my interview is a failure.

“Why do you write?” I ask, in one of my worst moments. Clarice’s face frowns in displeasure. She gets up, makes like she’s headed into the kitchen, but stops and says, “I’m going to answer you with another question: Why do you drink water?” Then she glares at me, ready to end our conversation right there.

“Why do I drink water?” I ask, stalling for time. And answer myself, “Because I’m thirsty.” I should have held my tongue. Then, Clarice laughs. Not a laugh of relief, but of barely contained irritation. And she says to me, “You mean you drink water so you won’t die.” Now she seems to be speaking only to herself, “Well, me too. I write to stay alive.” And with a mocking look, she hands me a glass of Coca-Cola.

I never imagined that I could fail like this. The interview, which has hardly begun, is basically over, since what else can I ask after that? But I carry out my duty, since I’ve got to make a living, after all. I ask the appropriate questions, and she answers, always with a certain disdain. Clarice also knows that the interview was over with that first disastrous question; the rest is just going through the motions. And she tolerates me until the very end.

Afterward, when I think she’s about to shoo me away, she asks me to come into the kitchen. “Let’s have a piece of cake,” she declares. She takes a frosted cake from the fridge, covered in swirls of merengue and stale fruit. She cuts generous slices and sets them on cheap plates. The legs of the Formica table are a little loose, and it wobbles. She doesn’t touch the cake, only drinks. “Lately, all I can drink is Coca-Cola,” she says. And downs two, three tall glasses, taking long sips.

I’m not expecting anything else, when Clarice says, “I like you.” Seeing that this declaration takes me by surprise, she explains herself, “You know just as well that this is all nonsense.” I’m not sure if that was the word, nonsense. She wanted to tell me that, in the end, what we had tried to do together was insignificant. “Do you like living?” she asks me. It is a very sad time in my life, but I feel that I have to lie. Stabbing gently with her fork, she reduces her slice of cake to crumbs.

We return to the living room. Clarice has me wait, and soon comes back with my tape recorder. She carries it with her arms held out like a sleepwalker, holding it with her fingertips, as if it awakened in her an immense nausea. I put it away. “There we go,” she says. “I don’t like machines.” Then she walks me to the door. “Come back and visit,” she says, “but never bring that again.”

As soon as I set foot on the sidewalk of Rua Gustavo Sampaio, I feel my skin prickling, like after a violent shock. “Clarice is a compulsive, who keeps on writing the same book,” declares a friend—and respected psychoanalyst—a few days later, as I’m telling him about my adventure. “She’s an obsessive, not a writer.” This shocks me, and I distance myself from the friend, who wasn’t very close to begin with. Clarice is nearer to me.

I could not separate the woman on one side (unbalanced, hypersensitive, aggressive) from the work (brilliant) on the other. There must have been some tether that kept them in a state of connection. That visit to Clarice’s apartment had shown me that the two sides were linked. She wrote in search of something. She once defined that something like this, “What’s behind the back of thought.” She used words to try to reach beyond words, to surpass them. She wrote to destroy words. That’s why she wasn’t interested in her image as a writer.

I remember her telling me, “I write because I need to keep searching.” And what made everything all the more complicated was that she never managed to define the object that she sought. It’s possibly the prevision of that object without a name that made her “go crazy.” Clarice wrote to reach the silence, she manipulated words to reach beyond them, she used literature the way we use a fork. My own thoughts frightened me. I’d never imagined a project so radical.

*

Time passes, and we run into each other on the street. Clarice is standing still in front of a shop window on Avenida Copacabana and seems to be looking at a dress. Embarrassed, I approach her. “How are you?” I say. It takes her a long time to turn around. At first she doesn’t move, as if she hadn’t heard a thing, but then, before I get the nerve to say hello again, she turns slowly, as if searching for the source of something frightening, and says, “So it’s you.” In that moment, horrified, I realize that the shop window contains nothing but undressed mannequins. But then my horror, so ridiculous, gives way to a conclusion: Clarice has a passion for the void.

I ask if she wants to get coffee. She says she won’t have anything; she’ll just keep me company. “It’s so hot,” she remarks. “I don’t handle the heat very well.” It’s only then that I notice how pale she is, and that trickles of sweat are tracing strange shapes on her forehead. I ask if she’s feeling all right. She doesn’t answer. “Have you gone back to writing?” she asks. I admit that I haven’t, and I want to say that her comments, rather than encouraging me, have paralyzed me, but I can’t do it. “You’re still afraid,” she says, and I don’t really know what she’s talking about. “You haven’t defeated it yet.”

Now I can’t hold back . “What do you think I’m afraid of?” I ask. “Well, of words, isn’t that it?” Clarice says, adding to my confusion. Her eyes rest on an old man drinking coffee at the other end of the counter. I keep quiet. “Why is that old man old?” she asks suddenly. “Well, because he must be all of seventy,” I answer, always stuck on that mania for facts that marks journalists.

She laughs for the first time. Then corrects me, “You’re still getting caught up in numbers. You just can’t write that way.” I sit there waiting for an answer to the question she posed. I assume she’s not going to give me one, until she says, “That old man is old because he’s afraid of what he is.” I don’t know if that’s exactly what she said, but it was something like this: the old man was afraid of being old, and that was precisely why he was old. It struck me as an enigma.

We walk down Avenida Copacabana. Clarice hails a cab and says goodbye. Intrigued, I go back to the empty shop window. There are the mannequins, in their elegant poses, but with no elegance whatsoever. Threads, cardboard boxes, a broom, light switches, a bucket. Staring at the void, I begin to understand that Clarice sees things the other way around. She sees what’s behind things.

I went back to visit her three or four times. These were difficult encounters, in which she seemed more interested in listening to me than in talking, which produced in me a strange mix of vanity and despair. In the kitchen, she served me cake and soda. She’d ask a lot of questions, which I’d answer cautiously. She’d make brief observations, full of dangling conclusions and additional queries. I could no longer read Clarice without that scratchy voice interfering, wafting with cake and Coca-Cola. It would be years before I could touch any of her books again.

*

Time passes, and Clarice falls gravely ill. She’s hospitalized. News comes that the cancer has spread. I consider visiting her in the Lagoa Hospital, but I don’t know if she’ll want to see me. I don’t even know if she can have visitors. She’s right: I am very fearful.

Clarice dies. I board a crowded, cockroach-infested bus and ride through the summer heat of Rio to get to the Israelite Cemetery in Caju to attend her burial. I stand clutching a seat back, eyeing those oblong creatures, flat as coins, crawling up the walls of the bus, and I think of G.H., who devoured a roach one day to taste life. Unfamiliar with Jewish tradition, I am surprised to find the casket sealed. Clarice’s not dead, that’s what this tells me. Her body’s not in there, the coffin is empty. They’re getting ready to bury just an empty outer shell. In disgust, I think about how roaches are the ones with an outer shell.

On the way home, trying to evoke the fragile moments we spent together, I recall a terrible phrase she’d told me that I’d forgotten: “There’s one thing I understand. Writing has nothing to do with literature.” But was that really what she’d said, or could it have been merely what I’d gleaned of what she hadn’t been able to say? And how could this be? If not writing, what would literature be? What fissure was this that Clarice, filling me with courage, was opening beneath my feet?

*

July, 1991. In a little bar in the Leblon neighborhood, I’m drinking whiskey with the writer Otto Lara Resende, who’s giving me invaluable information for my biography of the poet Vinicius de Morais. That one always leads us to women, and among several, we come around to Clarice Lispector.

When I speak the name of Clarice for the first time, Otto takes a deep breath, as if something were dragging him far away from there, and he’s got to focus hard not to lose himself. Then he says to me, “You’d better be careful with Clarice. It’s not literature. It’s witchcraft.” And urges that whenever I read her books, I proceed with utmost caution.

This declaration, uttered by Otto the skeptic, takes on a serious dimension. I hold on to it as another enigma, one among many that my proximity to Clarice Lispector has provided me, and that someday, who knows, I’ll finally decipher. It’s true that for a long time now, Clarice’s image has been associated with witchcraft. At the start of the seventies, she ended up as the guest of honor at the International Congress of Witchcraft held in the Santa Fe district of Bogotá.

Aware that the mystery wasn’t hers, but something inherent to her writing, Clarice accepted the invitation but refused to give a speech. All she did was read “The Egg and the Chicken,” one of the most obscure texts she’s ever written. Witches, warlocks, and sorcerers listened in silence.

Otto avoids talking about Clarice, who seems to disturb him. I insist. “Let’s talk about Vinicius,” he pushes back. Later on, another woman’s name comes up: Claire Varin. Otto is referring to a Canadian literature professor from Montreal who’s written two books on Clarice Lispector. Mysteriously, he warns, “It’s not an intellectual attraction, it’s a possession. Claire is possessed by Clarice,” he says. He gives me Claire’s address, but urges me to be careful. “They’re witches,” he says. “Don’t let them fool you.”

I can only respond to Otto’s remarks as an exaggeration. He smiles and, maintaining an air of mystery, takes a long sip of his drink. “Maybe it’s the whiskey,” I muse, to calm down. But after we part ways, and I take a cab home, I can tell that I’m still unsettled. Now it’s Otto’s words that continue to hold sway over me. Maybe he was the witch.

*

Curitiba, December, 1995. I receive a package containing a copy of Langues de feu (Tongues of Fire), a collection of essays on Clarice Lispector recently published by Claire Varin. Turns out Otto had gone ahead and sent her my address. Around the same time, I happen to buy Claire’s other book, Clarice Lispector: Rencontres brésiliennes (Brazilian Encounters), at a bookstore in Copacabana. The pieces were falling into place, without my having done a thing.

Claire has a doctorate in literature, but her books aren’t the work of a specialist. They’re works of passion. I still have her phone number in Montreal that Otto gave me. Now is the time.

Claire answers the phone effusively. We talk for over an hour with the intimacy of two strangers from opposite hemispheres who nevertheless share the same secret. At a certain point, she asks if she might evoke something rather discomfiting that Otto once said to her: “Be careful with Clarice. It’s not literature. It’s witchcraft.” Exactly the same phrase.

Poised to decipher Clarice’s oeuvre, Claire had taken this sentence as a point of departure and developed what she calls a “telepathic method.” Its basis is as simple as it is disorienting: one can only read Clarice Lispector by taking her place—by being Clarice. “There’s no other way,” she assures me.

I ask whether this method could in fact work. Claire answers by reading a passage from one of Clarice’s crônicas, brief literary sketches collected in Discovering the World: “The character of ‘reader’ is a curious character, a strange one. While completely individual with particular reactions, the reader is also terribly linked to the writer, since, in fact, the reader is the writer.” Clarice had already taken it upon herself to inform us.

Claire Varin rails fiercely against all rational interpretations of Clarice’s work. She asserts that they can only lead to what is alien to it, and thus to failure. “The reader must become a medium, through which Clarice incarnates herself,” she declares. This is the basis for her “telepathic method,” a process in which intuition is more important than understanding.

After hanging up, I keep trying to resist Claire Varin’s ideas. “They seem lifted from a treatise on esoterism,” I tell myself. But everything leads me in the opposite direction. Everything makes me believe Claire. I go into my bedroom and come across a copy of Água Viva on the bed. It conjures a scene from a few years earlier, when the young rockstar Cazuza told me in an interview that Água Viva was his favorite book. For a long time he couldn’t fall asleep without reading at least a few paragraphs. Every time he got to the end, he’d draw an X on the inside cover. He’d already read Água Viva one hundred and eleven times. How many more times did he read it before his death two or three years later? I’ll never know.

Only those who enter into harmony with Clarice’s writing, those who manage to oscillate, like her, between the word and fright, can keep going. They aren’t stories that you read, and about which you can think afterward, “First this happened, then that.” We can’t even be sure that we’re reading a narrative. In Água Viva, Clarice brings her aesthetic of the fragment to paroxysms, to utter shock. It’s hard to say what it is we’re reading—and it’s impressive to think that it was another person, her intimate friend Olga Borelli, alone with her treasure, who “put together” the chaos that Clarice would jot down on napkins, paper towels, newspapers, prescription labels. When Clarice could no longer organize what she wrote, Olga would guide her. And without meddling with what she was reading, she would eke out a path, a direction in which to funnel that storm.

Olga has recounted this: how Clarice would hand over a heap of fragments, which her friend would patiently divide into dozens of envelopes, then put in a box, like pieces of a puzzle. Without being conscious of writing a book, Clarice would write a book. Now her readers are charged with that same freedom. Freedom to push forward blindly, only to understand much later.

When it comes to Clarice, critics always repeat one word, epiphany. It’s a term taken from religion, referring to the apparition or manifestation of the divine. Clarice, however, doesn’t speak of god, but of the “it”—that is, the thing. Past critics rushed to consider her alongside phenomenology. They started saying that Clarice Lispector had written “philosophical novels.” This might be a way out, but I don’t know where it leads. One thing’s for certain—very far from Clarice.

There’s a woman in Paris, Hélène Cixous, who never wavers in her assertion that “Clarice is a philosophical author. She thinks, and we do not have the habit of thinking.” I hold up Hélène’s statements alongside Claire’s and wonder how many Clarices can fit inside one woman. Because each of us reads in our own way, each of us is Clarice in a way. Clarice, then, makes me encounter my own.

*

Porto Alegre, August, 1995. As we stroll down Rua da Praia, the writer Caio Fernando Abreu recalls some of his encounters with Clarice Lispector, who was a close friend. One day, Caio went to a book signing by Clarice. She made him sit next to her and while signing books, kept repeating softly, “You’re my Quixote, you’re my Quixote.” Caio was always gaunt and had a big goatee back then.

Another time, while walking together down the same Rua da Praia, the two stopped for coffee. Clarice, with her datebook full of literary engagements, had been in Porto Alegre nearly a week. Stirring her coffee casually, she turned to Caio and asked, “What city are we in again?”

Caio quickly got used to Clarice’s intimate relationship with imprecision. With the pulsations that surround the facts, and aren’t facts. With miasmas, rather than with reason. He read her ceaselessly for years on end. One day, he felt he had to stop. “If I didn’t stop, I wouldn’t be able to write anymore,” he asserts. Even the closed-off Caio felt invaded by Clarice at certain moments. Not by the discreet, elegant woman whom he so admired, but by her writing.

Claire Varin’s thesis seems to be confirmed in this way: when a reader falls in love with an author, the reader becomes the writer. The gaunt, dreamy figure of Caio made Clarice think of Cervantes’s Quixote. But for a long time, Caio was afraid to look in the mirror and see Clarice Lispector.

“I don’t know if what Clarice made is only literature,” he tells me. He can’t help but laugh when he says “literature.” The word doesn’t seem adequate. It doesn’t seem to say everything. “Something gets left out,” he tells me. Before I have the chance to ask, he adds, “I don’t know what.”

He had to distance himself. There comes an irremediable moment in which there’s no choice: either the reader distances himself from the writer and goes back to being himself, or else he’ll be lost. Caio knew how to recognize that moment and distance himself in time. He started writing “against” Clarice—battling with the writer who had invaded him. Maybe Clarice was right: reading is likely the most intense way of writing.

*

Paris, September, 1996. As a reporter for O Estado de São Paulo newspaper, I arrive at the apartment of the writer Hélène Cixous, hailed as the most important European expert on the work of Clarice Lispector. So very far from Brazil, my hope is to meet someone who can decipher her. A disciple of Jacques Lacan, confidante to Michel Foucault, and close friend of Jacques Derrida, Hélène is a typical Parisian intellectual. She never met Clarice in person, but, from an early age, even without knowing what she was waiting for, she’d awaited this encounter. “I felt fully formed as a writer, but always thought there was some other woman I was lacking,” she says. Derrida was her male other. She lacked the female one. “Yet I believed that I’d never find her,” she says.

Hélène offers a theory about the power of seduction in Clarice’s writing. “Every writer writes rigorously in her own language,” she says. “I, for example, write in Cixous. Clarice writes in Lispector.”

“Some even say that what Clarice did was witchcraft, not literature,” I venture to recall. At first Hélène refuses to consider this hypothesis. “Brazil is a very archaic country,” she says, and I feel a bit offended, but try to control myself. “But if witchcraft is a metaphor, I can accept it,” she reflects afterward. And concludes, “It’s not witchcraft. It’s knowledge of language.”

The thing is, Hélène notes, we talk all day and night, endlessly—but always in an unconscious state. We have no notion of language, of using a language, nor of what gets retained in words. Clarice, on the contrary, had a kind of hyperconsciousness when it came to language. She felt it all the time, and she knew that the entire language is at play in every word.

I leave Hélène’s apartment carrying a declaration that I find hard to take in: she asserts unwaveringly that Clarice is the greatest twentieth-century writer in the West and that her oeuvre is comparable only to Kafka’s.

Kafka, who had no homeland, might serve as a reference. Born in Ukraine, Clarice came to Brazil when she was still a baby. She married a diplomat, the father of her two sons. She finished writing her second book, The Chandelier, in Naples. The third, The Besieged City, was written in Bern, Switzerland. Several of the stories in Family Ties were written in London. The Apple in the Dark was written in Washington, D.C., between 1953 and 1954. Clarice was a writer who was always displaced from her center, or rather, who had no center.

A writer without a land. Clarice, Hélène convinces me, inhabited language—she inhabited Lispector. Brazil, where her family emigrated from the Black Sea, was merely a biographical accident. When she was nine years old, she lost her mother, and with her the foreign, Ukrainian voice that she inhabited. She used to say, much later, that her rolling r’s were just an effect of a tongue-tie condition from birth. Maybe that alone wasn’t it. But her difficulty with language was evident—and her greatness as a writer is, in large part, a result of this difficulty. Only a person who doesn’t adapt to language, who turns it inside out, who doesn’t trust it, can write a body of work like Clarice Lispector’s.

*

Curitiba, December, 1997. I take a bus and happen to sit next to a thin young lady with long fingers, a broken nose, and pale forehead, who’s immersed in reading The Passion According to G.H. I spy on her reactions—slight movements, ever so subtle, but that bestow her with a special dignity. The open pages are filled with notes, scribbles, arrows in red. The spine is bent, and the cover tattered. The rhythm of her reading is curious: the girl skips from one page to the next, then back to an earlier page, reads a little further ahead, then goes back again. She seems frozen by what she reads. I look at her: hair tied in a blue ribbon, almond-shaped eyes, freckles scattered across her youthful face, and a solemn expression, which could be taken as affectation but is no more than fright. Clarice would say that girl is what she reads. She is Clarice.

—Translated from the Portuguese by Katrina Dodson

Born in 1951, in Rio de Janeiro, José Castello is a Brazilian writer based in Curitiba. From 1971 to 1990, he worked as a journalist for various Rio news outlets, before leaving to pursue his long-deferred dream of writing books, while continuing a career as a books columnist. Castello went on to become a three-time winner of Brazil’s top literary prize, the Prêmio Jabuti, for a biography of poet Vinicius de Moraes (Vinicius de Moraes: o poeta da paixão, 1994), his novel Ribamar (2010), and a young adult novel based on the artist Arthur Bispo do Rosário (Dentro de mim ninguém entra, 2016). In addition to this essay on Lispector, from his 1999 essay collection, Inventário das sombras, Castello edited Clarice na cabeceira (2011), a volume of selections from Lispector’s nine novels.

Katrina Dodson is a writer and literary translator living in Brooklyn. Her 2015 translation of Clarice Lispector’s Complete Stories was awarded the PEN Translation Prize. She conducted the Art of Translation interview with Margaret Jull Costa for The Paris Review’s Summer 2020 issue. Dodson’s translation of Mário de Andrade’s 1928 modernist classic, Macunaíma: the Hero With No Character, is forthcoming from New Directions in 2022.

My Spirit Burns Through This Body

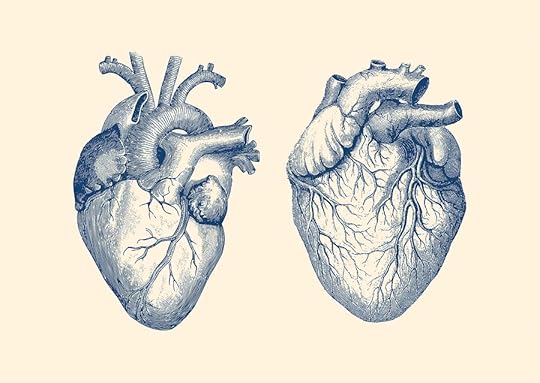

Human heart, dual view, vintage anatomy print

It is storming in Dar es Salaam, thunder belting through the sky and rain slamming against the roof for over twelve hours, until the roads are drowned in swells of water and everyone is stuck in traffic. I am lying under a mosquito net, aged white tulle draped over a four-poster, as the rain seeps under the door to pool on the tile. Kathleen and I catch it with towels and listen to the wind while the right side of my torso goes into convulsions.

It starts with my arm jumping, rippling from the shoulder down to my wrist, then it escalates until I’m watching my fingers flex and claw on their own, watching my elbow slam against my side, flaring my forearm out in spasmodic jerks. My shoulder blade lifts off the mattress, the muscles seizing their own control as my sternum scrambles toward the ceiling. My head snaps so violently to the side that it feels like my neck is being torn by the force. I wouldn’t let just anyone see me like this, but Kathleen is family. She sits next to me and holds my hand and I try not to tense my body to stop the convulsions, to control this treacherous flesh. “Let it go,” she says, and my speech slurs and stutters when I try to respond, nerves glitching in my mouth. We get me sitting up against the headboard and the convulsions seep down into my arm, leaving my head and neck mercifully alone for a bit. Kathleen brings me muscle relaxants and painkillers. I throw the pills down with bottled water, wincing at the taste. We talk about how scary this is, and then I make a joke about popping and locking as my arm carves severe and involuntary shapes into the air. We both laugh because it is better than being afraid.

When I was packing for this trip, I didn’t bring enough clothes; I was so focused instead on not forgetting any of my medications. I’d sat next to my suitcase with orange bottles scattered around me: three different muscle relaxants, two different painkillers, one for neuropathic pain, my antidepressants, my antianxiety meds, my acid-reflux meds that work together with my asthma meds so I can breathe at night, my migraine meds, my inhalers. Seeing them gathered together hurt. Three years ago, my flesh didn’t need all this, but my stress levels have climbed so high that my muscles have run out of space to hold all the tension, so they release it in flamboyant spasms. My somatic therapist says this is my body processing complex trauma, and we talk about the ways in which my flesh is desperately trying to keep me alive.