The Paris Review's Blog, page 131

December 29, 2020

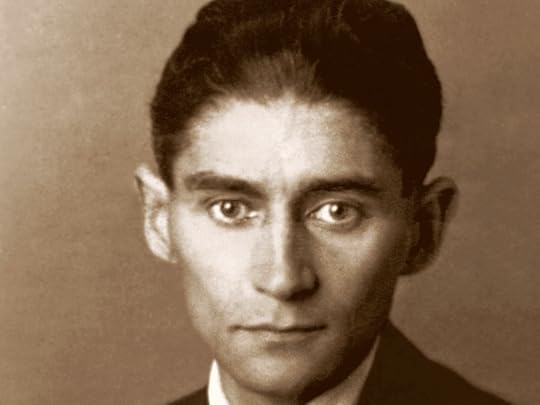

The Pleasures and Punishments of Reading Franz Kafka

We’re away until January 4, but we’re reposting some of our favorite pieces from 2020. Enjoy your holiday!

Franz Kafka. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Reading the work of Franz Kafka is a pleasure, whose punishment is this: writing about it, too.

In Kafka, no honor comes without suffering, and no suffering goes unhonored.

Being asked to write about Kafka is like being asked to describe the Great Wall of China by someone who’s standing just next to it. The only honest thing to do is point.

Once, a student approached Rabbi Shalom of Belz and asked, “What is required in order to live a decent life? How do I know what charity is? What lovingkindness is? How can I tell if I’ve ever been in the presence of God’s mercy?” And so on. The Rabbi stood and was silent and let the student talk until the student was all talked out. And even then the Rabbi kept standing in silence, which was—abracadabra—the answer.

Having to explain the meaning of something that to you is utterly plain and obvious is like having to explain the meaning of someone. Providing such an explanation is impossible and so, a variety of torture. One of the lighter varieties, to be sure, but torture nonetheless. It is a job not for a fan, or even for a critic, but for a self-hating crazy person.

Lost Libraries

We’re away until January 4, but we’re reposting some of our favorite pieces from 2020. Enjoy your holiday!

I was a student in the University of Cape Town’s English department when the Ransom Center acquired J. M. Coetzee’s papers. This was in 2012, when to be a student in the English department at UCT was to be required to hold a strong, fluently expressed opinion on J. M. Coetzee, his life, his work, the position he held within the South African academy, and whether or not there was a “fascinating contrast” between that position and the one he held overseas. Extra points if you could get all this off while referring to him at least once as “John Maxwell Coetzee” in an ironic and weary tone of voice. I never really got to the bottom of why people liked that so much, saying “John Maxwell Coetzee” and then looking around proudly, sometimes with the nostrils a bit flared. I’d managed to discharge the obligation to have an opinion on Coetzee by having a strident opinion on Nadine Gordimer instead, and so never learned why it was hilarious to refer to him by something other than his initials.

I did learn to smile knowingly when it happened, which was very often. No smiling about the Ransom Center acquisition though, a subject that was discussed with such bitterness that for a while I thought “Ransom Center” was departmental shorthand for American rapaciousness, something to do with rich U.S. institutions holding the rest of the world to ransom, riding roughshod over questions of legacy and snatching up bits of history to which they had no rightful claim. The Harry Ransom Center is of course a real place, situated on the University of Texas campus, containing one of the most extensive and valuable archival collections in the world. One million books, five million photographs, a hundred thousand works of art, and forty-two million literary manuscripts. Highlights of the collection, according to the center’s unusually user-friendly website, include a complete copy of the Gutenberg Bible, a First Folio, and the manuscript collections of Capote, Carrington, Coetzee, Coleridge, Conrad, Crane, Crowley, Cummings, and Cusk, looking at just the c’s. James Joyce’s personal library from when he lived in Trieste is in there, as well as the personal libraries of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Don DeLillo, and Evelyn Waugh.

A friend who went to UT told me that the Ransom Center is an ordinary-looking building, big and brown, and that it would be easy to walk past and have no idea what was in there. She said that undergraduates do it every day. I have confirmed this description by looking at photos online, but it doesn’t sit right with me on a symbolic level. It should be bigger, surely, resembling more of a compound or fortress. It should emit some kind of low humming sound, or glow. Forty-two million manuscripts! A million books! Kilometers of archival holdings in climate-controlled rooms, all wrapped up in sheaves and purpose-built cardboard boxes, lovingly tended to by armies of well-compensated grad students. This same friend was doing some work in the archives when they received Norman Mailer’s manuscripts. Great jubilation heard throughout the Center, she said. A week of celebrations culminated in a party where all the attendees were given little boxing-glove key rings.

December 28, 2020

I See the World

We’re away until January 4, but we’re reposting some of our favorite pieces from 2020. Enjoy your holiday!

© robert / Adobe Stock.

It begins in this way:

It’s as if we are dead and somehow have been given the unheard-of opportunity to see the life we lived, the way we lived it: there we are with friends we had just run into by accident and the surprise on our faces (happy surprise, sour surprise) as we clasp each other (close or not so much) and say things we might mean totally or say things we only mean somewhat, but we never say bad things, we only say bad things when the person we are clasping is completely out of our sight; and everything is out of immediate sight and yet there is everything in immediate sight; the streets so crowded with people from all over the world and why don’t they return from wherever it is they come from and everybody comes from nowhere for nowhere is the name of every place, all places are nowhere, nowhere is where we all come from …

The Fabulous Forgotten Life of Vita Sackville-West

We’re away until January 4, but we’re reposting some of our favorite pieces from 2020. Enjoy your holiday!

Vita Sackville-West

How preposterous is it that Vita Sackville-West, the best-selling bisexual baroness who wrote over thirty-five books that made an ingenious mockery of twenties societal norms, should be remembered today merely as a smoocher of Virginia Woolf? The reductive canonization of her affair with Woolf has elbowed out a more luxurious, strange story: Vita loved several women with exceptional ardor; simultaneously adored her also-bisexual husband, Harold; ultimately came to prefer the company of flora over fauna of any gender; and committed herself to a life of prolific creation (written and planted) that redefined passion itself.

Take as a representative starting point the comically deranged splendor of Vita’s ancestry. Her grandfather Lionel, the third Baron Sackville, fell in love with Pepita, the notorious Andalusian ballerina, and by her fathered five illegitimate children. When Lionel became the British minister in Buenos Aires, he sent those children to live in French convents. Upon transferring to the British Legation in Washington, DC, he summoned his nineteen-year-old eldest daughter to serve as his diplomatic hostess. Vita’s mother charmed Washington senseless with her bad English and so-called gypsy blood, receiving alleged marriage proposals from the widowed President of the United States Chester A. Arthur, Pierpont Morgan, Rudyard Kipling, Auguste Rodin, and Henry Ford. Somehow, from among these suitors, she chose to marry her first cousin, another Lionel. She returned to England and gave birth to their only child, Vita Sackville-West, on March 9, 1892.

By the age of eighteen, Vita had written eight full-length novels and five plays. She describes her childhood self in a diary as “rough, and secret,” frequently punished for “wrestling with the hall-boy,” fondest of her pocketknife, and inspired to start writing at age twelve by Cyrano de Bergerac. Still, when she formally entered society at age eighteen (“four balls a week and luncheons every day”), she was seen as a refined beauty, and took after her mother in attracting various glossy admirers. First among the failed wooers stood Lord Henry Lascelles, Sixth Earl of Harewood and first cousin of Tommy Lascelles, everybody’s favorite right-hand mustache in the Netflix series The Crown (when Vita rejected Lascelles, he married the Princess Mary, sister of King George VI).

But Vita wasn’t dazzled by men of great heritages or homes. She grew up at Knole, the Sackville estate, built in 1455 on a thousand acres and said to contain fifty-two staircases. More saliently, she was already smitten: with Rosamund Grosvenor, “the neat little girl who came to play with me when Dada went to South Africa.” Vita’s son Nigel (more on Nigel later—I have the utmost respect for Nigel) learned of this affair and many others when, after Vita’s death, he opened a locked gladstone bag in her sitting room and discovered her sensational written confessions.

We Tell Ourselves Stories in Order to Die

We’re away until January 4, but we’re reposting some of our favorite pieces from 2020. Enjoy your holiday!

Still from Gore Verbinski’s The Lone Ranger (2013)

I took one English class in college. The theme was contemporary fiction and, dutifully enough, we read DeLillo, Nabokov, Zadie Smith, Beckett, Coetzee, and—this last author was not like the others—Marilynne Robinson, whose novel Housekeeping appeared midsemester like a kind of anachronism. It was markedly domestic, reserved, inflected with lyricism, not self-serious but definitely sincere in its wonderment. At its first appearance, in 1980, spellbound reviewers praised its humble poetry, its interest in the ephemeral, the fidelity to small-town life.

Housekeeping, now nearing its fortieth anniversary, has returned to me throughout my writing career. Like those enraptured critics, in my first encounters I read for language, for voice, for craft. I loved this book. In graduate school, in a seminar on the literature of travel and trains, my professor recited the opening line to the class with a kind of disgusted glee: “My name is Ruth.” What kind of beginning was this? How had such an otherwise beautifully written book gotten away with it? The declaration—harsh, direct—is perhaps more shocking in the context of the rest of the novel, which proceeds with the gentle indifference of understatement. That opening chapter describes a mass drowning as no more upsetting than an exploratory dive: a train “nosed” into a lake, Ruth tells us, as calmly as a “weasel,” claiming all the passengers within as the water “sealed itself” over their souls. The scene is so soft, so seductive, it may as well have been narrated by a ghost. I remember we spent the remaining hour of that class discussing whether drowning truly was the most romantic way to die. I wonder now if perhaps parting from one’s body becomes more appallingly beautiful when alibied by the suggestion of an afterlife.

December 25, 2020

A Brief History of Word Games

We’re away until January 4, but we’re reposting some of our favorite pieces from 2020. Enjoy your holiday!

Paulina Olowska, Crossword Puzzle with Lady in Black Coat, 2014

When I began to research the history of crosswords for my recent book on the subject, I was sort of shocked to discover that they weren’t invented until 1913. The puzzle seemed so deeply ingrained in our lives that I figured it must have been around for centuries—I envisioned the empress Livia in the famous garden room in her villa, serenely filling in her cruciverborum each morning. But in reality, the crossword is a recent invention, born out of desperation. Editor Arthur Wynne at the New York World needed something to fill space in the Christmas edition of his paper’s FUN supplement, so he took advantage of new technology that could print blank grids cheaply and created a diamond-shaped set of boxes, with clues to fill in the blanks, smack in the center of FUN. Nearly overnight, the “Word-Cross Puzzle” went from a space-filling ploy to the most popular feature of the page.

Still, the crossword didn’t arise from nowhere. Ever since we’ve had language, we’ve played games with words. Crosswords are the Punnett square of two long-standing strands of word puzzles: word squares, which demand visual logic to understand the puzzle but aren’t necessarily using deliberate deception; and riddles, which use wordplay to misdirect the solver but don’t necessarily have any kind of graphic component to work through.

Murder Most Foul

We’re away until January 4, but we’re reposting some of our favorite pieces from 2020. Enjoy your holiday!

P. D. James. Photo: Ulla Montan.

“Death seems to provide the minds of the Anglo-Saxon race with a greater fund of innocent enjoyment than any other single subject.” So wrote Dorothy L. Sayers in 1934. She was, of course, thinking of murder; not the sordid, messy and occasionally pathetic murders of real life but the more elegantly contrived and mysterious concoctions of the detective novelist. To judge, too, from the universal popularity of the genre, it isn’t only the Anglo-Saxons who share this enthusiasm for murder most foul. From Greenland to Japan, millions of readers are perfectly at home in Sherlock Holmes’s claustrophobic sanctum at 221B Baker Street, Miss Marple’s charming cottage at St. Mary Mead, and Lord Peter Wimsey’s elegant apartment in Piccadilly. There is nothing like a potent amalgam of mystery and mayhem to make the whole world kin.

The Secret of the Unicorn Tapestries

We’re away until January 4, but we’re reposting some of our favorite pieces from 2020. Enjoy your holiday!

Original illustration by Jenny Kroik

This puzzling quest is almost at its end. —James Rorimer, 1942

Nobody knows who made the Unicorn Tapestries, a set of seven weavings that depict a unicorn hunt that has been described as “the greatest inheritance of the Middle Ages.”

Without evidence, the La Rochefoucauld family in France asserted that the tapestries originate with the marriage of a family ancestor in the fifteenth century. The tapestries did belong to the La Rochefoucauld in 1793, before they were stolen by rioters who set fire to their château at Verteuil. The family regained possession sixty years later, when the tapestries were recovered in a barn. The precious weavings of wool, silk, gold, and silver were in tatters at their edges and punched full of holes. They had been used to wrap barren fruit trees during the winter.

In late 1922, the Unicorn Tapestries disappeared again. They were sent to New York for an exhibition, which never opened. A rich American had bought them and transferred them to his bank vault before anyone else could see them. In February 1923, John D. Rockefeller Jr. confirmed from his vacation home in Florida that he was the American who had acquired the tapestries for the price of $1.1 million. The tapestries were transferred to Rockefeller’s private residence in Midtown Manhattan.

Fourteen years later, Rockefeller donated the tapestries to the Cloisters, a new medieval art museum he had funded as a branch of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The mysterious works were to be on regular public display for the first time in their five-hundred-year history. James Rorimer, the first curator of the Cloisters, had the intimidating task of interpreting them.

December 24, 2020

A Collision with the Divine

We’re away until January 4, but we’re reposting some of our favorite pieces from 2020. Enjoy your holiday!

© Jana Behr / Adobe Stock.

The deer drift in and out of the trees like breathing. They appear unexpectedly delicate and cold, as if chill air is pouring from them to the ground to pool into the mist that half obscures their legs and turning flanks. They aren’t tame: I can’t get closer than a hundred yards before they slip into the gloom. I’ve been told these particular beasts are fallow deer of the menil variety, which means their usual darker tones have been leached by genetics to soft cuttlefish and ivory, and they’re the descendants of a herd brought here in the sixteenth century as beasts of venery, creatures to be pursued and caught and cooked. The look of the estate hasn’t changed much since then. It’s still an extensive patchwork of pasture and forest—except now the M25 runs through it, six lanes of fast-moving traffic behind chain-link fence threaded with stripling trees. The mist thickens, the light falls, the deer appear and disappear, and the deep roar of the motorway burns inside my chest as I walk on to the bridge that spans it. This bridge is grassed along its length, and at dusk and dawn, I’ve been told, the deer use it as a thoroughfare from one side of the estate to the other. I know my presence will dissuade them from crossing so I don’t want to stay too long, but I linger a little while to watch the torrent of lights beneath me. For a while the road doesn’t seem real. Then it does, almost violently so, and at that moment the bridge and the woods behind me do not. I can’t hold both in the same world at once. Deer and forest, mist, speed, a drift of wet leaves, white noise, scrap-metal trucks, a convoy of eighteen-wheelers, beads of water on the toes of my boots, and the scald of my hands on the cold metal rail.

America’s First Connoisseur

We’re away until January 4, but we’re reposting some of our favorite pieces from 2020. Enjoy your holiday!

Seth Gilliam as James Hemings in Jefferson in Paris (1995)

Among his many claims to distinction, Thomas Jefferson can be regarded as America’s first connoisseur. The term and the concept emerged among the philosophes of eighteenth-century Paris, where Jefferson lived between 1784 and 1789. As minister to France he gorged on French culture. In five years, he bought more than sixty oil paintings, and many more objets d’art. He attended countless operas, plays, recitals, and masquerade balls. He researched the latest discoveries in botany, zoology and horticulture, and read inveterately—poetry, history, philosophy. In every inch of Paris he found something to stir his senses and cultivate his expertise. “Were I to proceed to tell you how much I enjoy their architecture, sculpture, painting, music,” he wrote a friend back in America, “I should want words.”

Ultimately, he poured all these influences into Monticello, the plantation he inherited from his father, which Jefferson redesigned into a palace of his own refined tastes. More than in its domed ceilings, its gardens, or its galleries, it was in Monticello’s dining room that Jefferson the connoisseur reigned. Here, he shared with his guests recipes, produce, and ideas that continue to have a sizable effect on how and what Americans eat.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers