The Paris Review's Blog, page 133

December 21, 2020

Losing Smell

We’re away until January 4, but we’re reposting some of our favorite pieces from 2020. Enjoy your holiday!

My mother, a classically trained dancer, didn’t stop dancing all at once. When she moved to America, she still performed, still taught. She stopped teaching when I was little. Still, she would sometimes be called into action, choreographing dances for the school plays my brother and I were in. A couple decades later, she stopped doing even that. Now, I know, she doesn’t even dance by herself, in her kitchen, as I remember her doing when I was a child. “I could give up dancing,” she told me once. “It wasn’t as if I was going to die. Only, it felt like the color went out of the world.”

Burn Something Today

This is the final installment of Nina MacLaughlin’s column Winter Solstice.

It’s dark. I am up early enough to see the stars. The porch light on the house across the street shines bright enough to bring shadows into the room. The neighborhood is still. The rattling newspaper delivery truck has not yet been by, the morning news not yet tossed on stoops. Frost not dew, the grass is stiff; a woman scrapes ice off her windshield and I feel it in my teeth. Mothwinged darkness opens itself widest now. Today is the shortest day of the year.

Wasn’t it just summer?

Or was summer a thousand years ago?

Was summer?

Now it’s now. Here we are. The Winter Solstice. The close of the year, the opening of a season—welcome, winter—the longest night, and light gets born again. Today is tied with its twin in the summer for the most powerful day of the year. Light a fire. Light a fire on this day. Let something burn. That is what the solstices are for. Summer flames say, Keep the light alive (it’s never worked, not once). In winter, a more urgent message: Bring light back to life (it’s worked every time so far).

The summer solstice scene is loose and dewy, flower-crowned crowds in debauch around the bonfires. People leaped over flames and the tongues of flame licked up high into the night. In winter: private fires. Home hearths. These fires “have such power over our memory that the ancient lives slumbering beyond our oldest recollections awaken with us …revealing the deepest regions of our secret souls,” writes Henri Bosco in Malicroix. The Yule log didn’t start as a cocoa confection with meringue mushrooms on the top. It was oak burned on the night of the solstice. Depending where one lived, the ashes of the solstice fire were then spread on fields over the following days to up the yield of next season’s crop, or fed to cattle to up fatness and fertility of the herd, or placed under beds to protect against thunder, or sometimes worn in a vial around the neck. The ancient cults cast shadows in our minds, shift and flicker, their fears are still our fears, down in the darkest places of ourselves.

We’re on the edge, teetering toward the other side of something. But what? Winter? It’s more than that. On the solstice, all the oppositions are alive, not in tension, but melting together, joined in the rolling-tolling ring of things. Tonight, there is space for all of it at once, the irreconcilables, the rival forces, the great dualities. Tonight, it’s not either-or, but both and and and. Light and dark and night and day and winter and summer and love and love and beginning and end and pleasure and punishment and tension and relief and abundance and lack and fear and fear and union and despair and stillness and revolution and illness and health and endlessness and end and tenderness and anguish and creation and destruction and flame and snow and thinking and doing and nothing and all and here and gone.

For some moments at the end of the year, space inside expands. Cupped hands hold all of it and we are brought outside ourselves. To watch a flame is to see something inside happening on the outside; the fire makes visible the force we feel in ourselves, and it makes visible the force in the silent sweeping stars above us. Gaston Bachelard writes of “intimate cosmicity,” and of uniting “the outside cosmos with an inside cosmos.” With fire, in this potent hinging moment of the year, we’re granted access to the inner cosmos and outer cosmos, the “chaosmos” as James Joyce puts it, our chaosmos—it’s inside of us and we’re inside of it. Such is what flame offers. Such is the charge of this day of the year.

It’s a dark charge. As anyone who’s grabbed a fistful of snow barehanded knows, the cold burns, too. As Inger Christensen writes:

Every child knows that snow and fire are no longer opposites. Not in a radioactive world.

So. It’s snowing. The snow is no longer snow, but it’s still snowing.

We’re now so fearful that we’re not even fearful anymore, but the fear is spreading anyway, and the closest word for it is sorrow.

She is writing of living under the threat of nuclear annihilation, but her words resound right now. We’re so fearful it no longer registers as fear, but it continues to move inside us and between us, reverberating across this country and around this whole globe. “Though in many of its aspects this visible world seems formed in love,” writes Herman Melville in Moby-Dick, “the invisible spheres were formed in fright.” What we can see is born of love; what we cannot is born of fear. What’s born of both? Could fire be the result of the friction between the two sticks of love and fear? Visible, swaying on the candlewick, dancing in the hearth. Invisible, the warmth, the burning heat that lives inside and glows unseen between.

A strain of fear has lived in us this year, we’ve spread it, not intentionally, we’ve absorbed it from the people closest to us and from strangers, from the blizzard-static crackle of the atmosphere. Over time, the fear has mutated, grown to something one barely recognizes, shifting into something other than it was and, as Christensen said, the closest word for it is sorrow. This is the season we’ve entered and there is no telling how long it will last. “Snow would be the easy / way out—that softening / sky like a sigh of relief / at finally being allowed to yield. No dice,” writes Rita Dove. Simple winter, the way snow softens a day, not this time. No dice, not yet, and even when we are finally allowed the sweetness of the yield, the sorrow won’t take its crumbling leave of us so soon.

Darkness, silent envelope, hold this sorrow.

We are in the fire now. We are moving through it and it is changing us and we don’t know how we’ll look or who we’ll be out the other side. Metamorphic symptoms “may look like breakdown or derangement,” writes M. C. Richards. “Ordeal by fire is ordeal by all the holy sparks that multiply.” The holy spark of each moment. The holy spark inside every person you love. The holy spark inside every person, all of us, burning with and for each other.

I have been trying to figure out if there’s an opposite of fear. The easy answers come too quick and aren’t correct: hope, comfort, calm, love. One can hope and fear at once; one can feel comfort or calm and the black snarl of fear still trills at the back of the skull. Love and fear are bedmates. The opposite of fear—maybe it’s stupidity.

It feels mean-spirited to say it, or a way of patting the back any of us who’ve felt an unfamiliar wavelength of darkness and unknown, who, in unsleeping night, have wondered, Are we going to be okay? Or, more accurate and more grave, Are we going to survive?

In this way, right now, on this winter solstice, perhaps the glowing strands that connect us to who and what has come before glow brighter now than usual. In this dark season, we are more kindred with the long-gone farmers, lighting their fires, collecting the ash, trying to bring light and warmth back to the land to keep the human scene around, there on their mountainsides, their desert camps, their swamps, hills, plains, forest glades, wherever they were, shivering with cold and the chill of not knowing: are we going to make it out of this alive?

The answer, no matter what, is no.

That’s always the answer but it’s been harder to press it between the cushions, to bury it into the shadows. That answer comes whiteblinding out these days. Let it. Let it light the dark. Here you are. Here you are! In pain, confused and frightened, and lit from within.

Come. Come closer. What now on this longest night? What now as Holly King surrenders and Oak King takes charge? What now as the wheel of the year tips to its lightening side? What now in this season of sorrow? What now as the solstice fire opens a doorway to our secret souls? The soul is thicker in winter, stretched between mind and body, which are, we kept getting told, by MDs and mystics alike, the same thing after all.

What now? Now it’s now it’s now it’s now and we are burning. Light the fire. We move through flames. We clutch hope in our palm like a tiny burning globe of snow. It’s painful, the flame of the snow of the hope that you will be okay and I will be okay and we will be okay, we will be here to see another season, to see, second by second, the light return to the world. In this small city where I am, today, the shortest day, light lives for nine hours, four minutes, twenty-nine seconds. Tomorrow, darkness begins to exhale. One two three seconds more of daylight.

We stand in the dark with strands of light between us. Feel the warmth, the heat, the glow, it’s yours to know. I want to give it name and say it to you, but I don’t know if I know the words. The soul doesn’t let us know, not all the way. We flail and give name to simpler needs. Here, sit. Get warm.

On a bridge I used to cross, a bit of graffiti in small neat letters read: Look at it all, it is all end full. The river and the coats and the fruits with all their colors. The bookcases and the blankets and the branches on the trees. The cardinal, shoulders, the moon. Look at it all. The brothy golden glow of the kitchen in winter with a soup on the stove. Every embrace. Every spoon. The fire and the frost. It is all end full. Everything that hurts and everything that makes our hearts soar. The evenings, the mornings, the weather, all the shifting weather. Look at it all. All the hellos and see you soons, brothers laughing. Look at it all. The oceans and the shovels and the milk. The naked press with another body, wanting, baths, bridges, feathers, fear and love and all the different kinds of light. Look at it all. Look at it all.

It is all end full.

Read Nina MacLaughlin’s series on Summer Solstice, Dawn, Sky Gazing, and November.

Nina MacLaughlin is a writer in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Her most recent book is Summer Solstice.

The Second Mrs. de Winter

We’re away until January 4, but we’re reposting some of our favorite pieces from 2020. Enjoy your holiday!

Illustration for a Rebecca paper doll by Jenny Kroik for The Paris Review

“The sexiness of [Rebecca] is maybe the most unsettling part, since it centers on the narrator’s being simultaneously attracted to and repulsed by the memory and the mystery of her new husband’s dead wife.” —Emily Alford, Jezebel

NB: This essay contains all of the spoilers for Rebecca.

Rebecca had good taste—or maybe she just had the same taste as me, and that’s why I thought it was good. She loved a particular shade of vintage minty turquoise. The kitchen cabinets were all this color. As were the plates inside. The cups and bowls were white with dainty black dots on them. Not polka dots—a smaller, more charming print.

I loved them. I might have picked them out myself. It made me feel sick that I loved them.

I imagined Rebecca had picked out these cups and plates when she moved into this house, but the cupboards I was investigating, and the very lovely dishes inside them, now belonged to her ex-husband, my boyfriend. Rebecca lived fifteen minutes away.

Of course, her name wasn’t really Rebecca. But grant me a theme. We’ll call him Maxim.

December 18, 2020

The Paris Review Staff’s Favorite Books of 2020

Don Mee Choi. Photo: © SONG Got. Courtesy of Wave Books.

It’s a cliché to say that reading transports you, but in a year in which I spent most of my days indoors, shuffling between my bedroom and my living room, the books I read really were a lifeline, a portal to an outside world. In the weeks before New York shut down, I luxuriated in my subway reading, laughing aloud at Alma Mahler’s antics in turn-of-the-century Vienna in Cate Haste’s biography Passionate Spirit, savoring the deceptively calm sentences of Amina Cain’s fabular Indelicacy, and texting photos of paragraphs from Abdellah Taïa’s sharp exploration of immigration, colonialism, and sexuality, A Country for Dying (translated by Emma Ramadan), to everyone I knew. I spent an exhilarating week attending a retrospective of the films of Angela Schanelec, a director whose work frequently features writers, including her early short I Stayed in Berlin All Summer, which contains a defense of fragmentation, of not making sense, that became something of a personal manifesto for my 2020. Nothing about my life or my country made sense once March hit, and I stayed indoors reading Annie Ernaux’s painful memoir about adolescence and abandonment, A Girl’s Story (translated by Alison Strayer); Iron Moon: An Anthology of Chinese Migrant Worker Poetry (edited by Qin Xiaoyu and translated by Eleanor Goodman), which should be required reading for anyone who owns an Apple product or a fast-fashion clothing item; and Marlen Haushofer’s peculiarly relevant dystopia, The Wall (translated by Shaun Whiteside). Kate Zambreno’s novel Drifts, which follows her narrator’s attempts to finish writing a novel, mirrored my own quarantined state of fitfulness, boredom, and bouts of obsession.

As the weather grew warmer, I kept thinking about the title story of Ho Sok Fong’s Lake Like a Mirror (translated by Natascha Bruce) and the precision with which it portrays contemporary Malaysian politics. Grenade in Mouth: Some Poems of Miyó Vestrini (translated by Anne Boyer and Cassandra Gillig) electrified me, while Lyonel Trouillot’s Street of Lost Footsteps (translated by Linda Coverdale) proved haunting. Elisa Gabbert’s essay collection The Unreality of Memory sent me down a thousand Wikipedia rabbit holes. And I was delighted to read an early novel of Marie NDiaye’s, That Time of Year (translated by Jordan Stump), with its questions of surveillance and insiders versus outsiders.

Autumn came, and in my insomnia leading up to the November election, I turned to Haytham El Wardany’s The Book of Sleep (translated by Robin Moger), with its meditative look at sleep, revolution, and writing, and Elfriede Jelinek’s incisive Trump-themed play, On the Royal Road: The Burgher King (translated by Gitta Honegger). The poems collected in Choi Seungja’s Phone Bells Keep Ringing for Me (translated by Won-Chung Kim and Cathy Park Hong) shook me up with their raw criticisms of consumerism and love, as did the essays on publishing and immigration in Dubravka Ugresic’s The Age of Skin (translated by Ellen Elias-Bursać). Don Mee Choi’s poetry collection DMZ Colony stayed with me long after it was over. And now it is somehow winter; now it is almost time to flip the calendar forward. In a year marked by a pandemic, nothing made sense to me, least of all the passing of time. —Rhian Sasseen

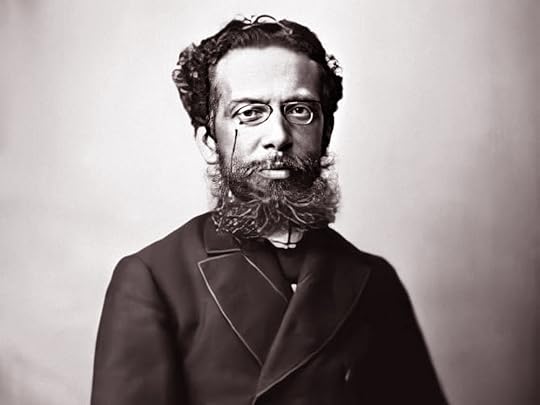

Joaquim Maria Machado de Assis. Photo: Marc Ferrez. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

The clock and the calendar were both our allies and our enemies this year. I believe the books that stand out from my 2020 do so in part because they take an interest in this troubled relationship between time and our finite experience of it. The first of these is Machado de Assis’s 1881 novel Memórias Póstumas de Brás Cubas, translated by William Grossman in 1952 as Epitaph of a Small Winner. (Two new translations of the book arrived this year: one by Flora Thomson-DeVeaux, the other by Margaret Jull Costa and Robin Patterson, both bearing the title The Posthumous Memoirs of Brás Cubas.) In Grossman’s rendering, the story is a picaresque retelling of Dante’s Commedia with a wicked sense of humor. Rather than contemplating greatness and immortality, as Dante did, Brás Cubas reflects on his rather middling achievements, anecdotes brilliantly interwoven with hallucinatory digressions and philosophical meandering. Pale Colors in a Tall Field, by Carl Phillips, is a more demure ode to the passage of time, a rich and sensual book of poems that filters bucolic moments through memory’s nostalgic lens. How sharp that is at the end of this year, when memories of even the most miserable subway rides seem fit subjects for poetic attention. —Lauren Kane

Danez Smith. Photo: Tabia Yapp. Courtesy of Graywolf Press.

How many ways can I split 2020 in half? Recently I’ve been trying it, cataloguing my before-and-afters, counting the year’s different selves by each major event. What a heavy year, to be remembered in fractures. The most obvious break happened in March, but there are other shifts that feel significant, too—my virtual college graduation, my soon-setting tenure as an intern here at The Paris Review. Leaving college, for example, meant I no longer spent most of my hours immersed in twentieth-century fiction, making my way through the canon. I dove into a more contemporary backlog: only this year did I finally read Sally Rooney’s Normal People, Bryan Washington’s Lot, and Cameron Awkward-Rich’s Dispatch. And this year, too, I sought the comfort of old favorites: Richard Siken’s War of the Foxes, Miranda July’s No One Belongs Here More Than You, Hilton Als’s White Girls.

Starting at the Review was another shift. Though virtual, my time here has immersed me in the deep waters of contemporary fiction. The past few months have felt like the most fruitful game of catch-up ever played, in which even transcribing interviews and filling in spreadsheets led me to some of my favorite reads of the year. Wasn’t it over Zoom that I was compelled to read Bryan Washington’s Memorial, a patient, deft novel that left me awash with tender feeling? Wasn’t it for the Daily that I read Yaa Gyasi’s Transcendent Kingdom, a meditation on personhood, and a confrontation with my own tendency to hide, to burrow away, to withhold?

Each split, then, has come with a seeking feeling, and what I loved in the wake of June and November was work that felt immediate—an invocation of place, a celebration of who we are, where we are. Nothing I read this year carries that vital cadence more than Danez Smith’s Homie. A collection by one of my favorite poets that includes “dogs!,” one of my favorite poems, was bound to make this list, but Homie, an ode to Blackness and community, was everything I needed in a year defined by sadness, stress dreams, and skin hunger. The poems become weapons in “my poems” but turn to tributes in “acknowledgements” and are maybe both all the time. “this ain’t about language,” Smith says in the title poem, “but who language holds.”And if Homie centers me in the present, then Black Futures, edited by Kimberly Drew and Jenna Wortham, feels like being held by a future self, one happier and more healed. Black Futures arrived earlier this month as the universe’s apology for the harshness of the year preceding—here, have an anthology of beauty, of joy. The book is an immaculately edited collection of old and new favorite writers and artists encased in gorgeous glossy pages I’ve pored over for hours. In the section titled “JOY,” Hanif Abdurraqib appears, as does Danez Smith, as does Ziwe Fumudoh. And just looking at it, the black hardback cover adorned with the iridescent block letters that read BLACK FUTURES, gives me happiness and hope, makes me feel inspired, excited, alive alive alive—which I think we need. —Langa Chinyoka

Karen Russell. Photo: Dan Hawk.

Within the first ten pages of Joel Townsley Rogers’s bonkers whodunit The Red Right Hand, reissued this year in Otto Penzler’s American Mystery Classics series, the surgeon Dr. Henry Riddle says he must “set the facts down for examination.” On page 190, forty from the end, he declares, “I have got all the facts down.” To the character’s credit, his situation requires a bit of set-up. The task at hand is to explain everything leading up to the moment a Cadillac with a crazed devil of a drifter behind the wheel and a well-dressed dead man in the passenger seat supposedly screamed past him on a narrow dirt road before disappearing. The only problem is that Riddle never actually saw the car go by; he learned about the incident from the handful of other characters who populate that lonely stretch of New England countryside. Further, his own car was blocking the road at the time the murderer allegedly passed. This is the kind of book that, though brief, stretches its limbs like a cat in the August sun, padding slowly around the action, allowing only glimpses of the truth, all the while setting the reader’s crackpot theories to boiling. It’s a neat structural trick, one that invites the creation of a mental corkboard cataloguing suspicions and coincidences. The exposition accumulates in drifts, never quite cohering into an easy solution, and the author fills out his corner of the Connecticut woods with a memorable cast: the dorky, loquacious Postmaster Quelch; the sequestered surrealist Unistaire; the cranky retired Professor Adam MacComerou, who literally wrote the book on murder; and a portrait in negative of Corkscrew, the hitchhiker behind the wheel, with his “scalloped hat,” red eyes, and murderous cackle. By the time the final pages swing by, snapping out of the expository slackness to deliver a series of revelations that completely upend the story, the reader is liable to feel as though they’ve been taken for a ride in that Cadillac themselves. But it’s well worth the bewilderment; the desperate calculations and dogged attention I paid The Red Right Hand culminated in the most enjoyable reading experience of my year.

Elsewhere, I had trouble sticking to one book. Collections helped. I’ve greatly enjoyed my time with Karen Russell’s latest batch of stories, Orange World, which sparkles with the caliber of sentences most writers spend decades hoping to summon. In Russell’s capable hands, I let reality dissolve around me like a meringue, blanketing myself instead in her rich, unmistakable voice. Each of the pieces I read in Lydia Davis’s Essays One grounded me—a welcome feeling. Her essays are like little pinned butterflies, pristinely preserved behind glass. In a year of painful ambiguity, it was a joy to rattle around inside the head of someone so certain and clear. And to the books I missed this time around: I’m sorry. Better luck next year. I know I’m certainly counting on it. —Brian Ransom

Elisa Gabbert. Photo: © Adalena Kavanagh.

I read Elisa Gabbert’s The Unreality of Memory in May, when we were all uncertain and pretty scared of what the pandemic was about to do. The prescience of the book unnerved me in a way that heightened the reading. It’s a wonderful collection of essays—I’ll have to return to it at a different time and see how I respond.

“Since that moment,” writes Zadie Smith in Intimations, “one form of crisis has collided with another.” This book was one of the first sustained literary engagements to emerge from the crises of 2020—certainly it was the first that I read—and, though slight, it began the process of assembling our collective troubles into a cogent and familiar form. The book isn’t really a direct engagement with the pandemic or with the Black Lives Matter movement; rather, it’s a setting of Smith’s thoughts within the context of those realities. “Talking to yourself can be useful,” she writes. “And writing means being overheard.”

But most often, rather than engage with the uncertainty of this year, I allowed it to lead me back to familiar titles for comfort and comradeship. A lot of my reading this year has been rereading. Recently, though, I was consoled to find Richard Holloway’s latest, Stories We Tell Ourselves, waiting for me on the doormat. His is a reassuring voice. A former Bishop of Edinburgh who fell out of love with his church and with God, he is good company on the page. I read him for his doubts and insecurities, for his willingness to acknowledge both the starkness of life with God and the starkness of life without. But mostly I read him because I hear the accent and cadences of home in everything he writes. To borrow from Smith, I enjoy overhearing him talk to himself. —Robin Jones

Gina Apostol. Photo: Margarita Corporan.

This year I read and watched and listened to the news in a way that would make my junior high civics teacher very proud, even yelling at the television like my dad does. But while the sensitive stoicism of reporters was a kind of cool comfort, the feat or miracle of imagination, craftsmanship, and perseverance known as the novel was cause for genuine, happy hope. Early in the year I had my mind exploded by Gina Apostol’s Insurrecto, the kind of book that makes one think, You can do that? That is, tell one story from so many divergent, imaginative points of view that the reader is left with a feeling of infinity, toss linear time to the winds, and talk frankly about the act of storytelling without sacrificing the joy of it. Yes, if you are Gina Apostol, you can do this, and it is beautiful. I read Insurrecto like some dogs destroy a stuffed toy; it was my favorite thing to do. In other words, it expanded the possibilities of the form—but this isn’t to discount the form’s preexisting possibilities. I loved, too, Brandon Taylor’s classical ideal of a novel Real Life. Every scene, every dialogue, fits perfectly over a hall-of-famer first sentence (“It was cool evening in late summer when Wallace, his father dead for several weeks, decided that he would meet his friends at the pier after all.”)—delicate interlocking layers of story that build satisfyingly up and out around Wallace, his father, and his friends. In autumn, I settled into Claire Messud’s essay collection Kant’s Little Prussian Head & Other Reasons Why I Write, the through line of which is that writing, in that it enables one human being to understand the experience of another, is magic. Each successful sentence, Messud asserts, is “a seizing of power away from fear and desire.” Of course she’s right. In this year that has seemed like it might actually end all years, books are medicine for the human condition. —Jane Breakell

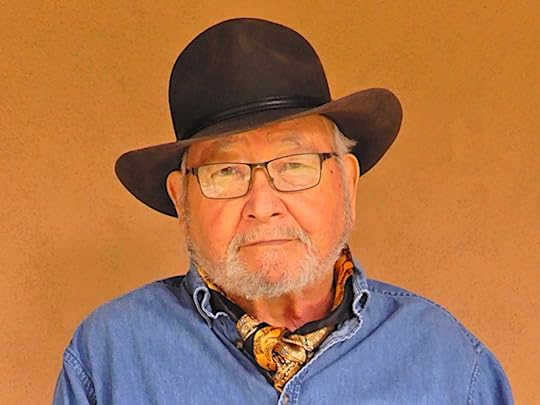

N. Scott Momaday. Photo: Darren Vigil Gray. Courtesy of HarperCollins Publishers.

Considering the first half of 2020 was my last semester of undergrad, much of my reading this year was retrospective. Michel Foucault, Saint Augustine, and Carlos Monsiváis acted as the theoretical lenses for my school work while Mexican films, Graham Greene, and Flannery O’Connor formed the meat of my research, all while I inhaled Paradise Lost, John Donne, and Edward Said through Zoom classes after quarantine began. Upon graduating, I still found myself looking back in my reading. I reread Between the World and Me and The Sound and the Fury while checking out Northanger Abbey, Sula, Tommy Orange’s There There, and Kiese Laymon’s Heavy for the first time; I found myself floored by each one. But upon joining The Paris Review, I immediately felt my reading horizons expand with the plethora of new books constantly being thrown my way. As I’ve discussed before, F*ckface, by Leah Hampton, made me sick with longing for the Appalachia of my undergrad, in all its humor and tragedy. Later, César Aira’s Artforum (translated by Katherine Silver) drew me back into the theory to which I dedicated so much time last year, but all with a smooth, smart satire that made for an effortless read and an intellectual earworm at the same time.

Most recently, I finished N. Scott Momaday’s latest collection of poems, The Death of Sitting Bear, which, frankly, took me some time to process and appreciate. It’s a delicate book that draws from a tradition dynamically opposed to the hyperintricate wordplay and referentiality of the contemporary poetry with which I most often engage. Instead, The Death of Sitting Bear loads its lines with a heritage and history that commune with the body and the soil of the planet, invoking a sort of contemplation that points away from the bare bones of language and into the lifeblood that is memory. In particular, Part III of the book, which recounts the life of Sitting Bear, contextualizes the collection as an exercise in remembrance.

Now I’ve started Yaa Gyasi’s excellent novel Transcendent Kingdom, and I find myself—after a year in which much of my reading was slow and distracted—fully enthralled by Gifty’s narrative and all the intricacies of how she relates to the world. As I extend myself into more contemporary works than those of my undergrad, I find it all pleasantly circular. Every book I read feeds back into what I’ve read before and how I’ll read what’s next. That’s growth. And even if it’s stunted by the insanity of 2020, I think that’s still something to be proud of. —Carlos Zayas-Pons

Jenny Erpenbeck. Photo: Nina Subin.

This has been a strange year for reading, and I am not sure what I will remember most when I look back on 2020, or even what I was looking for in the books I read when I could pull myself away from the news. Machado de Assis’s Posthumous Memoirs of Brás Cubas, translated by Margaret Jull Costa and Robin Patterson, brought me more joy than anything else I read this year; a sparkling stiletto of a book, its deftness and light touch leave you open to its blade. Magda Szabó’s Abigail, translated by Len Rix, came out in January, but I returned to it more than once as the year went downhill—not just for a retreat into the past and a foreign land, but also for its simplicity, the uncomplicated black and white of its morality. Azadi, a collection of very recent essays by Arundhati Roy, was the one that shook me, a reminder that while after a disaster we have the chance to improve on what was there before, doing so is an effort that requires work and imagination. But ultimately, in this year of storms, the book that gave me what I needed, even if it wasn’t something I knew to look for, was Jenny Erpenbeck’s Not a Novel, translated by Kurt Beals. Perhaps because it is a memoir, in which ultimately the center is one person and that person’s relationship with herself, it felt to me like an eye-of-the-hurricane book: aware of what has just passed, aware that more is on the horizon, but standing in the momentary stillness and reassembling itself to face whatever is coming next. —Hasan Altaf

Dan Gemeinhart. Photo: Kathryn Denelle Stevens.

As the pandemic fell heavy upon us this spring, I thought, Finally, the opportunity has arrived to read those long books for which life rarely affords the time. I came up with a scheme: I would alternate between two series. And so over the past several months, I tackled Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels, cleansing my brain after each Ferrante with one of Rachel Cusk’s Outline trilogy books. I am unduly proud to report that just this week, I finished my Herculean task and have now read seven books! All by myself! I found Ferrante utterly mesmerizing, and Lena and Lila were essential company during these dark months. I must admit less enthusiasm about Cusk’s cast of unpleasant characters, though I always found myself grateful for the kind of replacement consciousness that Cusk provides.

I read a few other books this year, but I will recommend only one more at this juncture: The Remarkable Journey of Coyote Sunrise, a middle-grade novel by Dan Gemeinhart, which my wife, my daughter, and I read aloud together before bedtime over a few weeks. It is, truly, an incredible book, the harrowing and funny story of a girl and her father, who, following the death of the girl’s mother and two sisters, take to the open road and live in a modified school bus. The book is full of misadventures, including but not limited to an interval in which a goat becomes a fellow passenger. Near the end of the book, at its emotional climax, my wife and I found ourselves subject to a veritable orgasm of sweet sorrow—the two of us cried mightily with our bewildered daughter between us. If you would like to have your heart’s guts scraped out and replaced with … better guts, I highly recommend this book, which will indeed leave you purified and changed. Despite this description, I assure you it is a great family read. —Craig Morgan Teicher

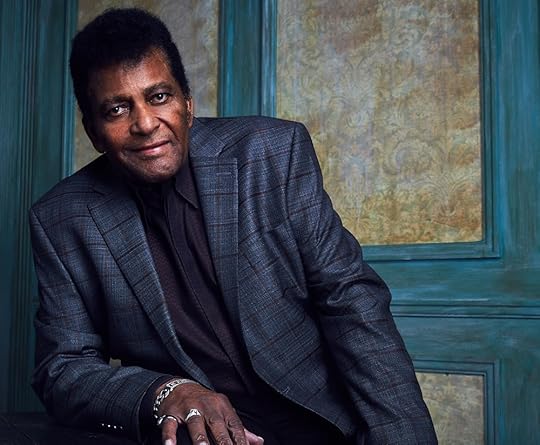

Desus Nice and The Kid Mero. Photo: Greg Endries / Showtime.

I used to love a production. Force-feeding my gentleman New York soundstage classics like Guys and Dolls near the beginning of quarantine reminded me that reality never had a chance. There’s gotta be lights and music, dance and costumes. I wanted the right book for 2020 to come leaping through the air bathed in spotlight, to land in my hands, sing a little tune, and open things right up for me. But there’s a reason I strayed from musical theater: real life doesn’t follow such a tidy grand jeté. Many books arrived when I needed them this year, almost none of them new or undiscovered. I read Barbarian Days, William Finnegan’s Pulitzer Prize–winning surf memoir, which reminded me that even New Yorkers can feel small beside the ocean and that many, many men before me have married the sea. I read Joan Didion’s The White Album, which can indeed be read as social criticism on whiteness, though that is not the whiteness to which the title refers. I read Milkman on the recommendation of an advisory editor for this magazine. It was so stupefyingly original and sharp that I wanted it to win the Booker all over again. I bought several magazines off of the newsstand. The New Yorker always has something—how is that? I lingered on Vanity Fair’s beautiful September 2020 issue, which was guest edited by Ta-Nehisi Coates, and its December 2020 issue, which features a galvanizing interview with Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, a woman so smart she need only wash her face in the morning to set the patriarchy quaking. And then there were Desus and Mero. They’ve written a book, God-Level Knowledge Darts: Life Lessons from the Bronx, and I recommend it, but everything this duo touches turns to comedy gold. The gents go by Desus Nice and The Kid Mero, friends from the Bronx who tell stories in a way that made me rethink comedy and the 2 train. Often Desus leads the narrative while Mero gets into character, but in a way that is so subtle it resists analysis, transcends being a bit, and gets me laughing till I’m physically exhausted on days I have no business even cracking a smile. I’m not saying it’s a vaccine; all I’m saying is I have the feeling that Desus and Mero are peeling 2020 off the ground, one scalding pepperoni slice at a time. —Julia Berick

Jill Lepore. Photo: Stephanie Mitchell / Harvard University.

At the start of the year, filled with big plans for my new self, I began a list in the back of my journal with small annotations on each book I read. Next time I have to write about my favorite books of the year, I thought, I’ll be prepared. That list, of course, ends abruptly in March. An addiction to breaking news alerts frayed my attention span so completely that the thought of finishing a novel became laughable. I was unable to get lost in fictional worlds when the real one had become so surreal. Reading was the thing that had once brought me the most joy, but for much of this pandemic, not to mention that moment when it felt like we might be on the brink of civil war, not to mention the months when America’s fundamental white supremacy rushed to the fore, I could not pick up a book. When it came time again (how?) to put this list together, I thought seriously about simply writing in, “I was supposed to read books this year?!?!” But the truth is, despite myself, I did. Garth Greenwell’s Cleanness, which I read back when I still knew how, gives the act of sex the attention it has always deserved from a great novelist, unfurling across whole chapters what usually happens in the jump cut. Anna Burns’s Little Constructions, which I was reading in mid-March, turns the darkness of humanity into the best joke you’ve ever heard. Her morbid surrealism is perfect for our times, but in this book all the characters have essentially the same name, and when my mind went, so did my ability to follow hers. Lily King’s Writers and Lovers and Kate Reed Petty’s True Story were able to remind me of the pleasure of reading when I was certain I had lost it forever. Both are that surprisingly hard-to-find gem, books I will stay up all night for, books that will make me forget where I am, and yet the sentences are also nice, and the mind behind them very sharp. For a long time the only thing I could read, and very slowly, was Jill Lepore’s brilliant These Truths, a history of America I desperately needed, and almost unfairly, overwhelmingly, eloquently told. Now, finally able to read normally again, I find myself immersed in Vigdis Hjorth’s Will and Testament, the perfect book for a cold winter month in which all you want to think about are, please, just let me focus here, the small interpersonal dramas of a dysfunctional family. —Nadja Spiegelman

Joy Harjo. Photo: Shawn Miller.

As history is being made, it feels important to also acknowledge history built—and this year, that (re)construction of our nation’s literary past came in the guise of two remarkable anthologies: When the Light of the World Was Subdued, Our Songs Came Through, a collection of Native nations poetry edited by Joy Harjo with LeAnne Howe and Jennifer Elise Foerster, and African American Poetry: 250 Years of Struggle and Song, edited by Kevin Young. Of course, brilliant new work was published this year, and for this reader the bleakest of years was made better by encountering Natalie Diaz’s Postcolonial Love Poem, Cathy Park Hong’s Minor Feelings, Gabriel Bump’s Everywhere You Don’t Belong, Diane Cook’s The New Wilderness, and Ayad Akhtar’s Homeland Elegies, to name a few authors whose writing grabbed me firmly by the shoulders. But to step out of the news cycle (and I include book press in that), to contextualize today by looking beyond the contemporary moment’s triumphs and injustices (an accounting slanted steep toward the latter this year), is akin to opening a door from a small room into an infinitely larger one. I found myself exploring these histories with the guidance of generous, adept editors—but also feeling sufficiently equipped by their thoughtful methodologies that I could develop my own path through. This idiosyncratic wayfinding led me to remarkable line and language, and each page affirmed the injustice and exclusion of earlier versions of American poetic history. But I found myself perhaps most drawn to the narratives herein, gripped by their potency. Here, too, was triumph and injustice, both inextricably bound to what we call America. Here was history and a version of possibility unique to this land. And here, within the struggle, was hope. As Peter Blue Cloud’s “Rattle” begins: “When a new world is born, the old / turns inside out, to cleanse / and prepare for a new beginning.” —Emily Nemens

December 17, 2020

Fear Is a Three-Thousand-Pound Bell

A series of small elevators takes me up the Gloria in Excelsis Tower of the National Cathedral, where balconies overlook the highest views in Washington, D.C. To one side is Sugarloaf Mountain; to the other is the Washington Monument. People kiss in the Bishop’s Garden below and I dangle my arms above them. I peer over the stone balcony while several women behind me ring the bells in patterns I don’t understand. They tell me there’s a six-month learning curve before I could play.

From the ceiling, ten ropes hang above a circular platform on which the ringers stand. The ceiling protects our hearing; above it are the bells. The rest of the ringing chamber is filled with odd end things—a chalkboard for writing out methods, a miniature model bell, novelty clocks, and a drawer filled with copies of Dorothy L. Sayers’s The Nine Tailors, a British novel that features stolen emeralds and the world of change ringing.

*

Change ringing is an intellectual sport. It involves a set of ringers, one per bell, taking turns to together perform a series of memorized patterns. The result isn’t melodic, like carillon bells, but something far more transfixing, like a pulsing code, the slow collapse of a bridge, marbles being dropped down the face of K2. Ringers mark weddings, funerals, federal holidays, and crises, or sometimes do what’s called a “peal attempt,” which involves ringing thousands of possible permutations on a set of bells, and can take hours without pause.

I heard about change ringing from a friend, whose parents met and fell in love at a tower in college. They’ve been ringing together for decades. The friend described change ringing as “religious adjacent”—historically, those who didn’t care for Sunday mass would ascend the tower to ring and drink. Contemporary ringers come from varying professions but often have backgrounds in math or music. Famous ringers include Sir John Betjeman, poet and defender of Victorian architecture; Jon Shanklin, discoverer of the hole in the ozone; Kate Barker, economist; John Bunyan, author of Pilgrim’s Progress; Paul Revere, silversmith.

My curiosity in the bells was immediate and inextinguishable, as though I’d found a possible sound that could make up for all my silences.

*

To get started on handling skills, I attend a beginning intensive practice. There are four other newcomers, and we appear quiet and giddy. We hold packed lunches like kids.

After pairing off with ringing instructors, we each stand at a rope. We learn two motions—the handstroke and the backstroke, which together complete a whole pull of the bell. It’s an unfamiliar movement, a body brainteaser. I’m calm and confident until the rope begins to bounce unpredictably, like something come alive. I maintain my grip, pretending not to panic, until I get rope burn. I let go. The ringing instructor shouts. Feeling hot, as I always do when I’ve done something wrong, I look at my pink hands. The instructor catches hold and explains a scenario in which the rope, uncontrolled, could whip around the room like a snake, lashing and snapping. This memory sticks with me for the next few months. When I forget the things that hold me in place, my error fuels the fright.

*

There are stories of inexperienced ringers getting knocked out of towers, the rope launching them into the air, lacerations, near hangings. A sign in the bell chamber reads: A STANDING BELL IS LIKE A LOADED GUN. IT ONLY TAKES ONE JERK TO KILL YOU. The lightest bell at the National Cathedral is 608 pounds, and the heaviest is 3,588. I look at an illustration of a ringer getting struck by lightning. I remember the extreme heights in Black Narcissus, the bell tower in Vertigo. My boyfriend sends me a tweet: “Robert de Honiton, died 1301. On New Year’s Eve he went up into the tower of St. Michael’s to help ring the bells and fell through a trapdoor.”

*

The first few months require a bit of coaxing. I ascend the tower feeling like a magnet in reverse.

Despite this, I am drawn to the magnificence of the bells. I believe that if I can learn how to ring, then I can stand up to other terrifying things, like depression and restlessness—but that if I can’t, then those things will somehow remain.

At practice, I can’t see the bell, but I feel where it is through the tension of the rope. I try to pull the rope in consistent, full strokes and then trust that what should happen, will. If I don’t cooperate, the bell always wins. I watch the experienced ringers, how they seem at peace, nodding to each other, murmuring, joking. Fumbling and straining, I get a soreness in my armpits throughout the week, in muscles I didn’t know I had.

*

A ringer suggests we take the stairs after practice, which I’ve never done. It is winter, the sun is down, and the stairs are a single-file spiral corkscrew that goes on for stories. I am surrounded by the stone innards of a dark empty tower. I sit on the steps for a moment, dizzy, the other ringer far below.

*

A variation of an analogy my mother used to tell me:

Fear is a three-thousand-pound bell. Three kinds of people ring it.

The first knows she will be fine, because she has rung the bell before, and knows that it can be done. She lives by truth.

The second has never rung the bell before, but sees the first person ring it and holds on to truth’s example. She lives by faith.

The third has rung the bell before and failed, and looks to the past, always expecting the same to occur. She lives by experience.

*

One Tuesday evening I am emboldened. We’re practicing “raising,” a skill I have not yet attempted. To “raise the bell” involves bringing it from a downward position to a mouth-upward position, where it rests on a wooden support, and from which you can ring. First, the rope is coiled in your hand, then you slowly gain momentum by pulling and gradually letting out rope for the bell to swing higher like a pendulum.

I step out of the elevator into the tower and approach one of the ropes before an instructor asks me to. I say I’m ready, though inside I’m rattled. It takes forever, and I need assistance, but I raise the bell. I leave elated, snow falling outside the Metro; I buy a single square of chocolate from the market and eat it slowly on the way home.

*

I’ve stepped out of an airplane and felt completely calm, but playing a Rachmaninoff prelude for an audience has made my entire body shake. I like corners, small enclosures, privacy curtains. Years ago I began writing small stories. I wrote them smaller and smaller. A brief story doesn’t overstay. In this way, I never disappeared completely.

Perhaps it’s easy to live by experience, to expect the worst to happen based on the past. Fear propels a hiker out of the way of a boulder rolling down the path but becomes detrimental when the hiker thinks of the boulder long past its appearance, even once the hiker is back home, staring anxiously out the window at the grassy hill and expecting the boulder to find them. Doom is not a boulder, the bells, or another person. Doom is something inside me. What’s worth believing in is that—despite past failure and the inescapable guarantee of future failure—life can still be full of usefulness and joy.

*

I begin to handle the ropes with a clear head. I learn how to ring with others, and control exactly when the bell is rung. The fear flashes back, but with a softer hold, easier to shake.

Eventually COVID-19 closes the Cathedral, so we have our practices online. We go over ringing apps, theory, virtual towers, learning methods at home. We watch parts of documentaries on a shared screen. I click, instead of pull, a rope to sound a weightless bell. Everything I’ve ever been afraid of about the bells is gone, reduced to twinkling sounds on a screen that I hold in my hand.

I was drawn to the magnificence of the bells, and online the magnificence of the bells was hard to find. Much like everything else—friendships, work, desire—the thing itself was replaced with an elusive outline, mathematical and ghostly, and I became afraid of it again. This time, it wasn’t easy to shake. Now I wait for the day to ascend the corkscrew staircase, and ring the heaviest bell in the tower.

*

A storm approached one evening when we were still meeting in the tower. I could see it all the way in Virginia, creeping steadily like a gray cloak. Wind whipped through the windows, and in smaller towers, you could feel the chamber sway. I watched as the storm got closer and closer. A fellow ringer told me it happened all the time, nothing to worry about. How it was, to be wrapped up by a thick churning sky, loud and booming, and riding on a promise to emerge unharmed. Someone eating a pastry in the Bishop’s Garden ran for cover. Briefly, they looked up. My arms dangled, I waved out.

Nicolette Polek is the author of Imaginary Museums, published by Soft Skull Press earlier this year. Her stories can be found in New York Tyrant, Lit Hub, Electric Literature, Chicago Quarterly Review, and elsewhere. She is the recipient of a 2019 Rona Jaffe Foundation Writers’ Award.

Variations on a Few Sentences by Can Xue

The following is Scholastique Mukasonga’s foreword to Can Xue’s Purple Perilla, the latest from isolarii, a series of “island books” released every two months by subscription. Rather than an author’s biography, isolarii forewords provide entry points to the world of the work, emotional tools, and generative reactions. Using three excerpts from the text as inspiration, Mukasonga places Purple Perilla within the current context of digital labor, isolation, and the climate crisis.

Can Xue.

I

(Fay) received a love letter: she didn’t know who had sent it.

This love letter wasn’t much like a love letter.

This morning, like every other morning,

I don’t expect any letters.

No use running to the mailbox,

there won’t be any letters,

no love letters,

not even one love letter,

one anonymous love letter.

No one writes me letters,

no one these days writes letters,

not even anonymous letters,

especially not a love letter.

I stay in front of my computer.

I’m leaning over my computer screen,

I press a key: the emails scroll by,

from bottom to top.

That’s all emails do, scroll from bottom to top,

scroll endlessly,

nothing can stop them.

A love email,

a billet-doux,

a declaration of passionate love,

the pain of love, mad love,

impossible over email,

it will immediately wind up in the spam folder,

in spam hell

mixed in with the horrific spam,

pornographic,

pedophilic,

evangelical,

satanist

nudist

conspiracy-theorist

Islamist

love spams burn in the deepest circle of spam hell.

I’m overtaken with sudden rage. Brusquely I shut the computer. The eye of light goes out. I am completely alone without emails.

I’ll open the drawer of the old writing desk. There’s still—who left it here?—a stack of notepaper. I pull out a sheet. It’s yellow, it has a nice thickness. I caress the grain. I search for a pen. Is there still a pen? Yes, in this drawer that I haven’t opened in years, there’s a Bic, a vestige from the time of writing, and I taunt the dark screen. I write from top to bottom and from left to right across the entire page:

I LOVE YOU I LOVE YOU I LOVE YOU I LOVE YOU I LOVE YOU I LOVE YOU

It’s dangerous to stray from one’s computer for too long, that’s the implacable law of remote work. I return as quickly as possible to the abandoned screen.

Tomorrow, I’ll find an envelope somewhere. I’ll fold it carefully, end to end, my anonymous love letter. I’ll find the courage to leave my attic. I’ll descend the never-ending staircase (the elevator is, of course, out of commission). I’ll go to the end of the street. I’ll choose a mailbox, if mailboxes still exist, with a nice first name: Charles, Robert, Edouard, Yvon, Jean-Luc … I’ll throw my letter in the box. I won’t expect a response.

II

Don’t belittle this ants’ nest. Underneath it is a large amusement park.

Carrying my travel authorization form, I venture to the skylight of my studio on the top floor. The raised window carves out a rectangle of sky. The sky is empty. It’s been a long time since the city pigeons vanished and the last gulls, rumor has it, found refuge on a few guano islands. The sky is empty. The long-haul airplanes don’t emit their cottony trails anymore. And even today, the sky has no clouds. The clouds that the wind pushes where it likes. Where are the clouds, stranger, your marvelous clouds?

The world is confined to the rectangle of the skylight, which carves out a rectangle of impeccably blue sky, without birds, without planes, without clouds.

Perhaps by leaning out of it, one might see the street below. And at the bus stop, a little girl who might be waiting for the bus. Who in the old days would wait for the bus. Who when the bus stops buys a ticket to the terminal. The last stop before the depot. The last stop, it’s already basically the countryside. The bus is full of children like me. It’s a public holiday. I know where they’re going. They’re going, like me, to Insect Park, they say with a laugh, the Entomological Institute for Adults. The school teacher planned a lesson on the animals from before. When there were animals like we see today on the TV. Lions, elephants, cows … The teacher said that there were also little animals that were called insects. There were loads of them, millions of species, said the teacher, who always exaggerates when he talks about things from before. Apparently they’ve been preserved in this park. So that the visitors, especially the children, can better see these bugs that are often quite tiny, the scientists who are capable of everything have enlarged a few specimens.

It’s true that the park insects, if we compare them to the ones they first showed us pinned in display cases, are much fatter and much bigger, big enough to scare you. But, said the teacher, there’s no need to fear these engorged bugs: they’re beneath large domes of unbreakable plastic, they can crash into the walls as much as they like, they won’t break the barrier.

“Let’s enter,” says the teacher, “we have passes to cut the line, stamped, validated, I bought the tickets.”

All the children let out cries of horror when they discovered the spectacle on display beneath the immense transparent domes.

In a discordant concert of buzzes, screeches, and drones flutter swarms of mosquitos with bloody trunks, wasps with tiger fur, hairy bumblebees with shaggy mustaches. Asian hornets chase dragonflies whose wings look like fine enamel and cloisonné jewelry, like queens in savage times used to wear, says the teacher. An eruption of multicolored butterflies falls into the nets held by spider acrobats. On the ground, in a landscape of dunes and reddish rocks, spiky stag beetles with jaws in the form of spears, spades, halberds, scythes, and javelins with barbed points all fight in perpetually recommencing jousts. Columns of black and red ants rush to transport the cadavers to the labyrinths of their underground cities. They cross the comings and goings of the dung beetles who, like Sisyphus, push their balls of carefully molded fecal matter up a steep hill of short grass.

The teacher was eager to show us what he called “the showstopper,” the park’s most spectacular and most popular attraction: the meal of the cannibal praying mantis who devours her husband. The mantis is like a very long blade of grass, neon green, reared on spindly legs that end in hooked pincers. Her little head resembles a grandmother’s bonnet with two fat bulging eyes that look like pompoms. She holds her tiny husband in her clutches. Diligently she butchers him, dismembers him, dislocates him. She ingests him little by little. “Perhaps he is hard to swallow, the dear husband,” the teacher jokes, “especially because the loving wife has no teeth.”

The children are frightened, the young ones fight to hold back their tears, they mustn’t cry in front of the adults.

“But,” interrupts a little girl, “my grandmother told me that before, there were bees that made honey. She even tasted it when she was little. She told me it was good.”

“Don’t listen to your grandmother. Our synthetic honey is much better, it lowers your cholesterol.”

“But,” worries a boy, “if one day those insects escaped from the amusement park … ”

“Have no fear, my little one, don’t tell anyone, but these are not exactly insects like before, they have a little chip inside them, they’re being controlled, and if there’s a glitch, boom! They explode.”

My computer screen shakes. I have to get back to the remote work that’s been assigned to me, as to every good citizen. The doctors and psychologists specializing in remote work strongly recommend against letting ourselves be carried off by memories. Besides, the insect amusement park hasn’t existed for a long time. Those neo-insects became too dangerous. And boom! It all exploded.

I close the skylight. It’s not good to breathe in the outside air for too long. I resume my place before the computer. And boom! Back to real life.

III

Wolves won’t come out in the daylight.

The wolves have entered the town.

That’s what they said tonight on the news. It didn’t come as a great surprise. We’ve been waiting for the announcement. For a year the alerts have multiplied. We hadn’t paid attention at first. Who still cares about wolves? They live in fairy tales. And that’s where they’ll stay. Leave the wolves to our grandmothers. But then the alerts multiplied. One a month, one a week, one a day, one every hour.

WOLF ALERT! WOLF ALERT!

The last wolves had been confined at the very tops of the mountains. Surveilled, surrounded. Prohibited from procreating above quota. Only enough to maintain a vestige of the species. A telltale pair. So how had they multiplied to this extent? Had the wolf hunters been negligent? Had they turned a blind eye to illegal couplings? A successful documentary had denounced the strange mores of certain peoples of the Altai: the mothers gave their firstborns to the she-wolves to be nursed and turned into fierce warriors, leaders of unsparing and cruel clans. But the children played for too long with the cubs. It turned them into wolf children. There was perhaps something true in those stories of werewolves. They were, confirmed certain politicians, the wolf-men who had become leaders of the pack.

Countless packs of wolves descended from the mountains, from the Urals, the Carpathians, the Abruzzos … First comes winter. The wolves are the children of winter. A glacial wind announces the arrival of their gray ranks. Then, little by little, the howls of wolves blend into the whistling of gales in the blizzard. The snow buries the countrysides and the towns. The trees gleam with frost sequins. Here come the wolves.

The wolves wait for night. Night is the domain of wolves. During the day, the wolves hide in their dens. The police search for their lairs, the army patrols the terrain, the drones fly over the suspected areas. The wolves are invisible in the light of day.

The wolves come out at night. It renders them invincible. The weapons of men turn on those who wish to use them. The drones refuse to obey. The war against the wolves is useless. Better to negotiate. The wolves are reasonable beings. An agreement can be reached. The negotiations are successful. The accords are signed. An equitable division is found. The wolves will have total sovereignty over the night. The day will be left for men.

Night has fallen on the town. All the lights must be extinguished. An order from the municipality. It is forbidden to go out once the sun has set. The curfew must be strictly obeyed. We are even encouraged to close the blinds and draw the curtains. We must resist the temptation to glance out the window.

But the temptation is too strong. Many succumb to it. They go out in the streets. The wolves entice them. The eyes of the wolves shine in the darkness. The beauty of wolves is fatal. The reckless ones vanish. Some say they’re devoured by the wolves, others that they become wolves. In the end, maybe it’s the same thing.

—Translated from the French by Emma Ramadan

Scholastique Mukasonga was born in Rwanda in 1956 and experienced from childhood the violence and humiliation of the ethnic conflicts that shook her country. In 1960, her family was displaced to the polluted and underdeveloped Bugesera district of Rwanda. Mukasonga was later forced to flee to Burundi. She settled in France in 1992, only two years before the brutal genocide of the Tutsi swept through Rwanda. In the aftermath, Mukasonga learned that thirty-seven of her family members had been massacred. Her first novel, Our Lady of the Nile, won the 2014 French Voices Award and was short-listed for the 2016 International Dublin Literary Award. In 2017, her memoir Cockroaches was a finalist for the Los Angeles Times’s Christopher Isherwood Prize for Autobiographical Prose. In 2019, her memoir The Barefoot Woman was a finalist for the National Book Award for Translated Literature. Her latest work to be translated into English is Igifu, which was published by Archipelago in September.

Emma Ramadan is a literary translator based in Providence, Rhode Island, where she co-owns Riffraff, a bookstore and bar. She is the recipient of an NEA fellowship, a PEN/Heim grant, and a Fulbright for her translation work. Her translations include Anne Garréta’s Sphinx and Not One Day, Virginie Despentes’s Pretty Things, Ahmed Bouanani’s The Shutters, Marcus Malte’s The Boy, and, with Olivia Baes, Marguerite Duras’s Me, and Other Writing.

From the foreword to Purple Perilla, by Can Xue. Purple Perilla is the third work in isolarii, a series of “island books” released every two months by subscription.

The First Christmas Meal

Edward White’s column, Off Menu, serves up lesser-told stories of chefs cooking in interesting times.

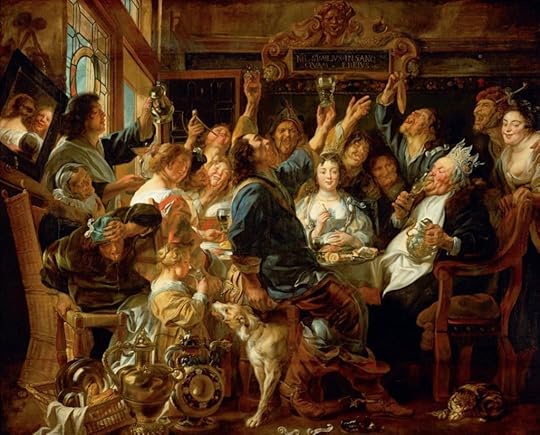

David Teniers the Younger, The Twelve Days of Christmas No. 8, 1634-40

These days, British and American Christmases are by and large the same hodgepodge of tradition, with relatively minor variations. This Christmas Eve, for example, when millions of American kids put out cookies and milk for Santa, children in Britain will lay out the more adult combination of mince pies and brandy for the old man many of them know as Father Christmas. For the last hundred years or so, Father Christmas has been indistinguishable from the American character of Santa Claus; two interchangeable names for the same white-bearded pensioner garbed in Coca-Cola red, delivering presents in the dead of night. But the two characters have very different roots. Saint Nicholas, the patron saint of children, was given his role of nocturnal gift-giver in medieval Netherlands. Father Christmas, however, was no holy man, but a personification of Dionysian fun: dancing, eating, late-night drinking—and the subversion of societal norms.

The earliest recognizable iteration of Father Christmas probably came in 1616 when, referring to himself as “Captain Christmas,” he appeared as the main character in Ben Jonson’s Christmas, His Masque, performed at the royal court that festive season. Nattily dressed and rotund from indulgence, he embodied Christmas as an openhearted festival of feasts and frolics. But by the time he appeared on the front cover of John Taylor’s pamphlet The Vindication of Christmas, in 1652, Father Christmas had grown skinny, mournful, and lonely, depressed by the grim fate that had befallen the most magical time of year. The days of carol singing and merrymaking were over; for the past several years Christmas across Britain had been officially canceled. The island was living through a so-called Puritan Revolution, in which the most radical changes to daily life were being attempted. Even the institution of monarchy had been discarded. As a ballad of the time put it, this was “the world turned upside down.”

The prohibitions on Christmas dining would have particularly aggrieved Robert May. One of the most skilled chefs in the land, the English-born, French-trained chef cooked Christmas dinners fit for a king—a doubly unwelcome skill in a time of republicanism and puritanism. May connected the medieval traditions of English country cooking with the early innovations of urban French gastronomy, and was at the height of his powers when the Puritan Revolution took effect. During those years, he compiled The Accomplisht Cook, an English cookbook of distinction and importance that was eventually published in 1660. In more than a thousand recipes, May recorded not only the tastes and textures of a culinary tradition, but a cultural world that he feared was being obliterated—including the Christmas dinner, an evocative sensory experience that links the holiday of four centuries ago with that of today.

*

Pretty much the only things we know about Robert May come from the biographical section that introduces The Accomplisht Cook. According to that, May was born in Buckinghamshire, in the south of England, in 1588, during the reign of Elizabeth I. At the time of May’s birth, his father was cook to the Dormers, a prominent Catholic family closely connected to Spanish ruling elite. At the age of ten, May was sent to France where he performed a five-year apprenticeship in the best kitchens in Paris, before returning to England where he honed his skills cooking for a number of the most prominent Catholic families in the country. Since the days of Henry VIII, Catholics had been a persecuted minority in England, but the ascension of the Stuart dynasty when James I took the throne upon the death of Elizabeth I in 1603 heralded decades of relative tolerance. Wealthy Catholics were able to spend lavishly on food and entertainment, allowing May to thrive.

The young May’s experiences abroad hint at the changes occurring in English food culture of the time, especially among the social elite. During the late Tudor and Stuart eras, numerous foodstuffs, including potatoes, tea, coffee, chocolate, and tobacco, arrived from the Americas and established themselves as staples of the national diet. The Accomplisht Cook is replete with non-English influences, giving us a vivid idea of what new fashions entered his kitchen in the early 1600s. May drew heavily from Spanish and Italian recipes, and his book includes thirty-five dishes for eggs that he took from the pioneering French chef François Pierre La Varenne. Despite this, May’s food was quintessentially English. The Accomplisht Cook laments that French chefs “have bewitcht some of the Gallants of our Nation with Epigram Dishes” in favor of the sturdy traditions of English cooking. The Englishness of May’s approach is palpable in his suggestions for Christmas dinner, dominated by roast meats and featuring a mince pie. Today’s mince pies—a Christmas institution in Britain and Ireland—are filled with a sickly-sweet concoction of dried fruit, fortified wine, mixed spices, and mounds of brown sugar, but before the Victorian era they also contained meat. May suggests numerous cuts of beef (including tongue, buttock, and intestine) or hare, turkey, and mutton, among others. In his recipes for a veal-based mince pie, he recommends mixing it with more familiar ingredients such as dates, orange peel, nutmeg, and cinnamon, flavors that are still powerfully evocative of what many of us would consider a “traditional” Christmas.

May’s bill of fare for Christmas Day is huge: forty dishes split across two courses, with additional oysters and fruit. Partly this reflects the nature of May’s experience in the service of some of the wealthiest people in the country, and partly the Stuart approach to dining. The diaries of May’s contemporary Samuel Pepys detail the meat-heavy, gut-busting dinners he hosted each year on the anniversary of his kidney stone operation (that the procedure worked and didn’t kill him was, in the seventeenth century, truly a cause for celebration). For a party of six, Pepys once served a salmon, two carp, six roast chickens, ox tongue, and cheese. May’s Christmas dinner has a similar feel. For the first course the mince pie is served alongside nineteen other dishes, including a roast swan, sweetbreads, a boiled partridge, a roast turkey infused with cloves, mutton with anchovy sauce, and “a kid with a pudding in his belly.” As was customary for the era, these would arrive on the table in one grand exhibition of food, in an ostentatious display of hospitality; surely there was no expectation that all this food would be consumed. The historian Liza Picard sums it up bluntly: “everything got cold, and there was a shocking amount of wasted food at the end.”

Jacob Jordaens, The Feast of the Bean King, 1640-1645

The spirit of abundance, indulgence, and generosity communicated by May’s menu was the very cornerstone of Christmas at the start of the seventeenth century, a time of year that, then as now, was tied to food and drink. For the observant, there were three church services on Christmas Day. The first took place before dawn, immediately after which it was time to break the ritual abstemiousness of Advent with a breakfast rich with dairy and meat. This was the official start of twelve days in which the bounty of that year’s harvest was enjoyed to its fullest extent. For many the festive highlight was Twelfth Night, traditionally honored with very boozy parties and Twelfth-cake, a fruit cake made with liberal amounts of sherry.

The sorts of Christmas dinners cooked by Robert May were beyond the means of most families. Even acquiring the ingredients for a Twelfth-cake could be difficult and expensive. Pepys spent the costly sum of twenty shillings for the cake that his maid Jane baked for one of his Twelfth Night parties. And yet throughout the medieval and early modern period it was common for rich landowners to put on great spreads and entertainments for those in their community. For a few days each year, even many of the poorest people had the chance to eat rich, sweet, fatty foods, to drink plentifully, and to experience the exquisite pleasure of a warm fire in the depth of winter. This wasn’t seen as a charitable custom so much as a social obligation. Mirroring the moment in the Nativity when the three kings bowed down to a baby born in a stable, Christmas was a time when the usual repressive social order was, in brief but thrilling ways, flipped on its head. As the historian Diane Purkiss explains this was a season of “licensed openness with a careful structure.” It was universally understood that as soon as the magical twelve days of Christmas were over, the usual order would be restored.

In some towns and villages, a Lord of Misrule was appointed during Christmastide to direct the revelry, with freedom to cause irreligious havoc. There were also beloved traditions such as mumming, a sort of trick-or-treat ritual of costuming and performing, sometimes involving cross-dressing or mockery of important people. Similarly, wassailing involved groups of singers going to the doors of the rich in expectation of food and drink. Wassailing was not begging, but one half of an unspoken social contract; to withhold one’s hospitality would be an egregious breach that could result in violence. The remnants of wassailing, and the attitude that underpinned it, is still found in the carol “We Wish You a Merry Christmas,” in which the faintly obnoxious verse of “We all like figgy pudding, so bring some out here” is followed by the unambiguously menacing “We won’t go until we’ve got some, so bring some out here.” This was not the Christmas of our post-Dickens world, a time associated with children and domestic coziness. To Robert May’s generation, Christmas was much more about the adult experience of the world—and it crackled with potential danger.

Throughout England and Scotland, there was a growing section of society who decried Christmas as popery. Such sentiments were common among Protestant zealots opposed to the injudicious rule of Charles I, who inherited the thrones of England, Scotland, and Ireland in 1625, and who some suspected of wanting to re-establish Catholicism. The religious tensions metastasized into a political crisis. In 1642, civil war broke out in England between the Crown and Parliament, the start of horrendous bloodshed that swallowed most of the next decade. By and large, Catholics supported the royal cause, with the more radical Protestants on the side of the Parliamentarians. The main period of war raged for seven years, claiming roughly two hundred thousand lives, somewhere between two and three percent of the population. It seems that Robert May continued to work in the kitchens of wealthy homes, but as food became scarce and opportunities to prepare opulent meals dwindled, his income must surely have been diminished.

As the war raged, the religious extremists who controlled Parliament attempted drastic reforms of English life. First, the Puritans struck festivals and saints’ days from the calendar on the basis that they did not feature in the Bible. Then, in 1647, the observance of Christmas was officially banned. From now on, it was decreed, there were to be no special church services, all shops must remain open, and no special activities undertaken to acknowledge the date.

The ferocity of the public backlash was inevitable. Riots broke out in towns such as Canterbury and Ipswich in December 1647, and when apprentices marched in London the following spring shouting “Now for King Charles!” resentment over the abolition of Christmas was understood to be part of their grievance. By this point, Charles had been captured by Parliamentarian forces and was staring at humiliating defeat. His court had been famous for its Christmas indulgences. But during Christmas 1648, even his request for the simplest festive pleasures of mince pie and plum pottage were denied him. A month later, he was tried, convicted, and executed of crimes against his own people. Soon after, the monarchy was disbanded and Oliver Cromwell became Lord Protector, a dictator in all but name. In these staggering circumstances, unthinkable just a few weeks earlier, the Puritan assault on tradition widened and accelerated. By the early 1650s, it seemed there was not a church open anywhere in England on December 25, and that Christmas had succumbed to an eternal winter.

Pieter Claesz, Tabletop Still Life with Mince Pie and Basket of Grapes, 1625

This, at least, was the surface impression. As Ronald Hutton has shown, the Puritan Revolution managed only “to strip the festival of its public aspect and (ironically) much of its Christian content.” Cromwell’s regime could—and did—tear down community decorations, force shops to open and churches to shut, and puncture any merriment on the streets, but eradicating the rituals being observed within the home was far harder. So much of the meaning of Christmas was manifest in food and drink, and so Christmas was kept alive in kitchens throughout the land. It’s true that in London and other parts of the country, soldiers had the authority to enter premises where the cooking of celebratory food was suspected. But Cromwell’s regime had no chance of rooting out every mince pie, every bowl of plum pottage, or every Twelfth-cake being quietly enjoyed in ordinary homes.

Indeed, Hutton suggests that during Cromwell’s time in power the very wealthiest households still spent generously on Christmas food supplies and paid for the services of itinerant entertainers. It was in the homes of such rich and well-connected people that May continued to work throughout the 1650s. We know little of his experience of cooking in the thick of the Puritan Revolution but it’s likely that he carried on preparing Christmas meals, albeit in less joyous circumstances, and on a more modest scale. Ever since the Reformation, England’s recusant Catholics—the community in which May had learned his craft—had grown used to honoring their faith in quiet, discreet ritual. Now, along with all but the most zealous Protestants, each December they attempted to keep Christmas alive in their hearts by means of what they put in their bellies.

*

Had the ban on Christmas lasted for many more years it’s possible the festival would have permanently disappeared from British shores, and therefore from the lands of its burgeoning empire. As it was, the Puritan Revolution sputtered to an end when Cromwell died in September 1658. Absent its totemic strongman, the experiment in republican government collapsed. In 1660 the old king’s son, Charles II, was put on the throne.

The collapse of the monarchy had engendered a wave of nostalgia for the “good old days” before the war. During Cromwell’s tenure eight new cookbooks—a substantial number at the time—were published, tapping into a public fascination with the habits and customs of the old aristocracy. One of May’s former employers, Elizabeth Grey, Countess of Kent, was responsible for one such book, A True Gentlewomans Delight, in 1653. Another, The Queens Closet Opened, in 1655, promised to share the secrets of the old royal household, including its kitchen.

May’s own book, The Accomplisht Cook, was published in 1660, the year the monarchy was restored. It differed from previous English cookbooks in that it was aimed unapologetically at those who wished to be chefs at a grand establishment, more in keeping with books that were beginning to be seen on the continent. Yet, in his introduction May explained that this was also intended as a work of cultural continuity, a celebration not only of great cooking but of the exuberant hospitality that the war and the revolution had stymied—a time “before good House-keeping had left England” in his own wistful turn of phrase. He advises, with relish, on how to create a theatrical centerpiece of a stag made from pastry filled with claret, a nod to the old aristocratic pastime of hunting. He also instructs how to make joke pies full of live frogs and birds that will escape the very moment the crust is cut. He assures us that this never fails to “make the Ladies to skip and shreek,” and it’s for their amusement that he recommends removing the yolk and albumen from eggs and replacing them with rosewater, at which point the host should “let the Ladies take the egg-shells full of sweet waters and throw them at each other,” like water balloons.

The carnival antics might have played well at one of his Christmas banquets, replete with its exotic delicacies, mountains of rich meats, and dishes of sweet jellies, steaming pies, and creamy custards. His entry for Christmas food is only a small proportion of the thousand or so recipes, yet with knowledge of the times he lived through, its presence was a pointed reminder: the world was back on its axis; the new normal was, at last, the old normal.