The Paris Review's Blog, page 136

December 1, 2020

Redux: A Little Bedtime Story

Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

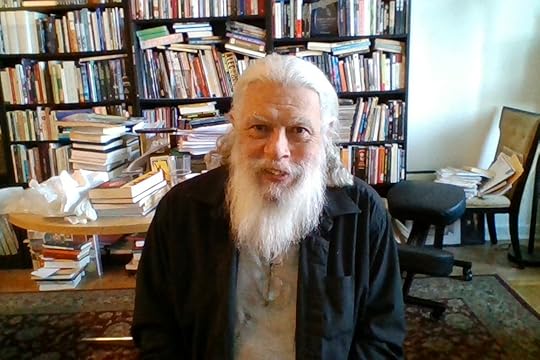

Samuel R. Delany. Photo: Samuel R. Delany. CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...), via Wikimedia Commons.

This week, The Paris Review is feeling leisurely and lethargic and embracing the idea of daydreams. Read on for Samuel R. Delany’s Art of Fiction interview, Jessi Jezewska Stevens’s short story “Honeymoon,” and Mary Jo Bang’s poem “Q Is the Quick.”

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, and poems, why not subscribe to The Paris Review? Or take advantage of our new subscription bundle, bringing you four issues of the print magazine, access to our full sixty-seven-year digital archive, and our new TriBeCa tote for only $69 (plus free shipping!). And for as long as we’re flattening the curve, The Paris Review will be sending out a new weekly newsletter, The Art of Distance, featuring unlocked archival selections, dispatches from the Daily, and efforts from our peer organizations. Read the latest edition here, and then sign up for more.

Samuel R. Delany, The Art of Fiction No. 210

Issue no. 197, Summer 2011

DELANY

Today I’m a five-o’clock-in-the-morning riser. Although I do stare at the wall a lot.

INTERVIEWER

Stare at the wall?

DELANY

I think of myself as a very lazy writer, though other people see it differently. My daughter, who recently graduated from medical school, once told me, “Dad, I’ve never known anyone who works as hard as you. You’re up at four, five o’clock in the morning, you work all day, then you collapse. At nine o’clock, you’re in bed, then you’re up the next morning at four to start all over again.”

Gide says somewhere that art and crime both require leisure time to flourish. I spend a lot of time thinking, if not daydreaming. People think of me as a genre writer, and a genre writer is supposed to be prolific. Since that’s how people perceive me, they have to say I’m prolific. But I don’t find that either complimentary or accurate.

Nicoline Tuxen, Portrait of a Woman Reading in Bed, ca. 1890, oil on canvas, 18 x 23 1/4″. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Honeymoon

By Jessi Jezewska Stevens

Issue no. 228, Spring 2019

To be fair, I can’t really say that I enjoy vacations. I’m on vacation all the time, so when I’m away it feels like work. I am a jewelry consultant at a five-star hotel, where I tend to a nook filled with gems. All week long I daydream to the sound of heels clacking across a polished marble floor. My mind melts. I could be miles away. I could be at the beach! Occasionally the phone rings, and then there’s some real excitement—a guest is placing an order for a surprise. The rest is a breeze. I take lunch twice. At two, I put a sign on the door and go for a jog. BE BACK SOON. No one seems to mind.

Photo: R-E-AL. CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...), via Wikimedia Commons.

Q Is the Quick

By Mary Jo Bang

Issue no. 186, Fall 2008

“The quick brown fox jumps

Over the lazy dog”: It was a little bedtime story

And it was only told us if we would “be quiet.”

But quiet was a difficult thing to be.

The heart makes a jump-start sound.

Each time someone comes up the steps—

Both their feet give off the white grate of shoe leather

As it meets a stair. They wanted us also to “be happy”—

Which was even more difficult

In view of the sad fact

That happiness is part of a pair called a “smug set”;

Happiness plus some other benignly self-satisfied state.

The story, once we “deserved” it, began,

“Shh, be quiet,”

Just as the quick baby was about to leap …

And to read more from the Paris Review archives, make sure to subscribe! In addition to four print issues per year, you’ll also receive complete digital access to our sixty-seven years’ worth of archives. Or take advantage of our new subscription bundle, bringing you four issues of the print magazine, access to our full sixty-seven-year digital archive, and our new TriBeCa tote for only $69 (plus free shipping!).

A Masterpiece of Disharmony

Most successful collaborations are celebrated for the near-magic synchronicity between the musicians. But when Duke Ellington, Charles Mingus, and Max Roach shared a recording studio in 1962, the result was a monument to tension and friction.

The title track of Duke Ellington’s 1962 album Money Jungle opens with a jarring, metallic sound, something between a bison call and a buzz saw, bleating alone in tripping doubles, siren-tense. It is the bassist doing something unnatural to his instrument—running his fingernail against the strings, snapping them, making them percuss. A violent sound. Five seconds of the bass bleating and the drums burst, a crisp wave of sound from the hi-hat, a parade over the lowing of the bass, cresting and dipping in preparation for the piano, and after another five seconds the piano comes in loud, bursting, a chord played with all the pianist’s strength, as if he had thrown all his weight down onto those first keys. In the wake of this opening salvo the piano flits about the bass, weaving bright circles, like a bullfighter leaning tight to the bull and swaying just out of reach—in turn the doubles of the bass become a run, the opening figure played over and over again, obsessively, the bass stamping the ground, beating its head against the wall just to touch something. When the bass finally lets up, relaxes off its single note and dips, the piano dips right behind it—a bird snatching an insect off the ground. The album, in the first thirty seconds, is less a collaboration than a tug-of-war, a tangle of thrown gauntlets and cross-purposes. For the remaining five minutes of the song the piano is in control, jumping in front of and about the bass, staying just ahead of its push.

The track ends not in explosion but in exhaustion. The bass tries one last charge, snapping the same note over and over to the limit of endurance, and soon loses its proportion, slowing to something heavy and irregular, a wounded breathing. The piano slows too, but mechanically, like a wind-up toy at the end of its string—a few soft, low plinks, and gone, scattered over the dense body of the bass. After the track was recorded, it is said, the bassist attempted to walk out of the session. The album, in my estimation, is a masterpiece.

Money Jungle had been intended as a collaboration of styles and generations—Duke Ellington, sixty-three, big-band grandee, measured and smooth, a living legend albeit slightly passé, playing around with two emissaries of sweating, jagged, hard-driving bop—the drummer Max Roach, thirty-eight; and the bassist and composer Charles Mingus, forty, a man occasionally proclaimed to be the inheritor of Duke’s mantle, a musician who named “Duke and Church” as his two influences and a volcanic personality who had previously been fired from Duke’s 1953 European touring band after only four days for fighting a fellow musician. Mingus in concert, finally, with his idol. Duke embracing his descendants, bestowing his personal seal on their lineage. And Roach straddling both styles, yoking them together in rhythm—or at least, that was the plan. In Roach’s recollection, at their sole prerecording meeting, Ellington had self-effacingly called himself “the poor man’s Bud Powell,” and had expressed a desire to play an assortment of compositions, not only his own. On the finished album, however, every track is Ellington’s.

At some point on the afternoon of September 17, 1962, at the only recording session for Money Jungle, in Sound Makers Studio on Fifty-Seventh Street, Midtown Manhattan, Charles Mingus pulled the cover over his double bass, sharp and rough, effortlessly lifted the hefty thing, and left the smoke-domed recording room, eyes on the floor and muttering to himself, cursing, stomping down the hallway toward the elevator and the canyon-intense late light pouring into Seventh Avenue. One reviewer theorizes that his exit must have come after the recording of the title track—the difference in tone between that and the following songs is simply too great. Maybe Max Roach, sitting at the drums in a silky green shirt, loose fit, had said something to Mingus, smiled horizon-flat and wide, rolled a jolly little trill on his snare drum, and Mingus stopped, covered the bass, and left. Maybe Roach slouched infinitesimally on his stool as Duke trailed Mingus out of the room, bemused but unruffled. Maybe Mingus, as the bassist Chris Wood heard, had been seething all day at Duke, watching and waiting as Duke played one after another of his own compositions, his own ideas, keeping the session entirely on his own terms. Maybe the songs Mingus had brought, expecting Duke to give them his inimitable marble lightness, were left crumpled and sweating in his pocket, and he struggled all day against the man he idolized.

There is disagreement even among the stories of the disagreement, as if the tension and disharmony of the session bled into collective memory. Producer Alan Douglas remembered, of the walkout, “That’s one of the visuals I will never forget. We were in the studio on Fifty-Seventh Street between Sixth and Seventh Avenues, and I remember leaning out the window, looking up towards Seventh Avenue and seeing Duke Ellington chasing Charlie Mingus up the street.” Yet Duke remembered stopping Mingus at the elevator, and never going into the street, recounting years later—

A funny thing happened in the middle of the session. Mingus suddenly and without warning started to pack up his bass and when I inquired where he was going and what was the trouble, he said, “Man, I can’t play with that drummer.” I said, “Why? What’s wrong?” He said, “Duke, I’ve always loved you and what you’re doing in music but you’ll just have to get another bass player.” And I said, “You mean just like that in the middle of the date—come on man, it can’t be that serious.” But he kept packing and went out of the door to the elevator, I followed him to the elevator and after he rolled off a few more beefs, I slowly and quietly said, “Mingus, my man …”

Ever the strong, aloof father, Duke does not recall noticing the steady boil of Mingus’s frustration, frustration clearly audible on the record, and clearly directed at Duke and his piano. The only agreed-upon fact is that Mingus left, and Duke followed. The centerpiece of the album is strife, both in the recording and the music.

In the Money Jungle session photos, Mingus is in short sleeves, suspenders, hatless and hulking and bottom-heavy behind his double bass, holding it delicately with thick fingers. Ellington is wearing a trilby and cardigan, trim mustache and bags under his eyes the shape of a coupe cocktail glass—the frail elegance of the newly elderly. Mingus is staring down and aslant in each photo, directly at Ellington sitting at the piano, the intensity of his gaze still alive.

A collaboration is generally assumed to be dependent on a unity between its participants—minds at least intending and attempting to move in the same direction. And indeed, one of the glories of collaborative music is listening as multiple people concurrently have the same idea, see the immediate future as a shared, coherent structure through which to communicate a path forward, extemporaneously building something complex and alive. It approaches the metaphysical, a reciprocal subsuming of egos to a larger gestalt comprising, alchemically, each player. Yet that collaborative beauty of music cannot rest on unity and harmony alone—for it to mean anything, there must be the possibility of conflict. Just as it is difficult to call a decision good if the possibility of a bad decision was not available—the category loses its meaning without the spectral presence and potential of its opposite—successful collaboration carries the shadow of its failure. It is the awareness that the player could have made a different choice, could have asserted their ego and lunged for control, that gives the moment of collaborative concordance its frisson and pleasure. If there is no residue of what has been overcome, no sense of an autonomy being renounced, the collaboration has no life.

If most great collaborations are the triumph of harmony, Money Jungle is a monument to disharmony—and it is a masterpiece for it. Mingus, throughout the session and climaxing in the recording of the title track, seems to be set on harrying Duke—bumping him, playing over him, trying to throw him off. And Duke, to the surprise of many listeners, pushes back, playing in an aggressive, angular style believed to be alien to him. One reviewer wrote, “I’ve never heard Ellington play as he does on this album; Mingus and Roach, especially Mingus, push him so strongly that one can almost hear Ellington show them who’s boss—and he dominates both of them, which is no mean accomplishment.” About Mingus’s pushiness on the title track, the pianist Uri Caine said, “Duke is being very fatherly to Mingus in the sense of saying, ‘I’m going to let you be obstreperous there; you can do your thing and I’m going to hold it down for you. Next time you do it, I’m going to go out, too.’ There’s a lot of psychology going on in this session.” Another pianist, Matthew Shipp, said of Duke’s playing on the album, “There’s nothing rote about any aspect of this album. It has none of that feel of when you’re throwing people together in the studio and you’re just going through the motions, because the tension was palpable. I find it an album of utter vitalism, unlike a lot of straightahead albums of that time.” It is a roused, rejuvenated Duke Ellington playing on Money Jungle, no longer cocooned by his stature, no longer playing in a void scaffolded by his legend. And Mingus is peculiarly rejuvenated as well, briefly returned to the adolescent stance in which every idea is fought for. The tension is the vitality.

And yet, to fight and claw coherently with another musician for an entire album requires a deep, rooted connection, a fundamental commonality in the way each sees and moves within music. The feeling of Money Jungle is that of a chess match—when Ellington and Mingus grapple, it betrays not misunderstanding but an understanding so ambient and encompassing it allows the player to see what the other is doing and consciously work against it. One begins to marvel both at the energy of the music and at the players’ ability to maintain this high-wire act, to undermine each other without falling into total disarray. Every cacophony produced is set against the euphony the musicians know they could choose and are renouncing. A multitude of possible harmonies, possible concordances, are produced like sparks from the friction of their strikes against each other, shading the music, creating an optical illusion with an absent, suggested richness. Money Jungle is a rare in vivo demonstration of collaboration—as each element of cooperation is spurned, it is made audible—and an exploration of the dissonant regions reachable by musicians who truly understand each other. Mingus storming out after the death struggle of the title track was the capstone of the session’s collaborative logic, his recognition of its completion, and his instinctual contribution to one of the central pillars of music—its end. It was his last lunge, and it was perfect.

Eventually Duke did persuade Mingus to return, and they finished the final tracks—perfectly competent, and less contentious. “Picked up the bass, came back into the studio and we recorded very happily ever after till the album was done,” Ellington recalled. Yet they had already, in the grip of the boiling disharmony, recorded the two most remarkable tracks they would play that session. The album opens with one, the title track, the apex of their disunity, and follows with the other, a demonstration of their connection—“Fleurette Africaine,” a hushed, achingly lovely song built around a simple piano figure, almost a lullaby. As Duke describes it:

One number in particular was as close to spontaneity as you can get, I believe. I explained what we were going to do, with no thought as to what they were going to do. I said, “Now we are in the center of a jungle, and for two hundred miles in any direction, no man has ever been. And right in the center of this jungle, put in the deep moss, there’s a tiny little flower growing, the most fragile thing that’s ever grown. It’s God-made and untouched and this is going to be ‘The Little African Flower.’” I started to play, and we played to the end and that was it.

The song ends with Duke’s piano repeating the figure, softer and softer, as Mingus rolls and rubs his fingers pleasantly over the bass, purring—a sound near to the anguished yelp of the title track, rotated minutely into harmony.

Matt Levin is a writer living in Uganda.

November 30, 2020

The Cold Blood of Iceland

The American artist Roni Horn first visited Iceland in 1975, when she was nineteen. Since that initial journey, she has returned to the island nation, both in person and through art, time and again; she has described Iceland as “a force, a force that had taken possession of me.” Island Zombie: Iceland Writings, which will be published this week by Princeton University Press, collects vignettes and photographs from Horn’s ongoing fascination with the country. An excerpt appears below.

Photo: Roni Horn.

I don’t want to read. I don’t want to write. I don’t want to do anything but be here. Doing something will take me away from being here. I want to make being here enough. Maybe it’s already enough. I won’t have to invent enough. I’ll be here and I won’t do anything and this place will be here, and I won’t do anything to it. And maybe because I’m here and because the me in what’s here makes what’s here different, maybe that will be enough, maybe that will be what I’m after.

But I’m not sure. I’m not sure I’ll be able to perceive the difference. How will I perceive it? I need to find a way to make myself absolutely not here but still be able to be here to know the difference. I need to experience the difference between being here and not changing here, and being here and changing here.

I set up camp early for the night. It’s a beautiful, unlikely evening after a long rainy day. I put my tent down in an El Greco landscape: the velvet greens, the mottled purples, the rocky stubble.

But El Greco changes here, he makes being here not enough. I am here and I can’t be here without El Greco. I just can’t leave here alone.

*

Photo: Roni Horn.

A sunny blue morning and I’m looking for a place to rest. On the map there’s a beach not far ahead. I leave the road and drive across a grassy field and soon I’m on a red-sand beach. The tide is out, the ocean far away. I get off the bike and wander down the shore. It’s windy and cold, but the sun is warm in a cloudless sky. The arctic terns are about, they screech and hover and swoop down at my head.

I lie down on the sand; near the earth the wind is still. I fall into a deep, brief sleep. Through my eyelids the bright light of the sun saturates my body. As though from outside, I see myself translucent and feathered red to orange at the edges of my silhouette, a science fiction. I dream of my body inanimate, prone, giving up its opacity.

As I wake I feel a weight on my chest. And there, as my eyes slowly open, is a large brown bird perched on my stomach. It casts a shadow over my face. I lift my head as the bird takes a peck at my chest and wonder is this in life or in death? I panic and the bird spreads its wings, digging its perch in a little deeper as it takes off.

*

Photo: Roni Horn.

There are no reptiles here. No snakes, no crocodiles or alligators. No lizards, turtles, or frogs. No mammals that could hurt you, either. The people are rarely criminal and only occasionally violent, and almost never toward a stranger. There are no serial murderers here, maybe a few crimes of passion here and there, but no decapitated women or otherwise mutilated bodies. Essentially there is no violence. No irrational threats. No intimidating predators. No cold-blooded animals. All the things that aren’t here resolve what is. Relief from fear is freedom.

But there’s something else here: the weather. The weather is here instead—a Freudian slip of ecology. As though weather was wittily and mercilessly substituted for reptiles. Weather, a natural force magnified by island circumstance, is the cold blood of Iceland. Weather with its amoral, wanton violence is lethal here.

Weather moves rivers and makes them, too. Weather blows roads away or turns them into mud. It washes the rocks out of the mountains and dams the roads. The weather is one thing here and fifty feet away something else. Cars are blown off roads, frequently in some places, and people are picked up or knocked down by sudden gusts. In the interior, near the glacier for example, the winds can get so bad you must crawl on the ground to get through. Sandstorms stop visibility a foot in front of your face; this is a way of being lost without having gone anywhere. When the glaciers begin to melt the earth trembles at the gushing vehemence of engorged rivers. Water is thrashed out of the ocean and thrown in the air, whole fields of water are blown out of lakes. Waterfalls are smashed into fine spray and blown back up into the clouds.

Changing weather can strand you quickly. Just around the bend a whiteout might erase the world entirely. Sometimes briefly, sometimes not. Rivers can turn into lakes, and so can fields. When a field becomes a lake it’s intimidating just standing near. These instant lakes have properties unpredictable and unmapped. Encountering these new bodies of water presents a unique form of being lost. You are lost not because you don’t know where you are but because where you are is not what it is.

*

Photo: Roni Horn.

I’d been living on the bluff only three weeks when I ran out of reading material. I searched the lighthouse for possibilities. Up in the tower I found the repair manual for the electric generator (good over breakfast, but not more) and True Life, Unsolved English Murder Mysteries. It would be hard not to read the mysteries, I thought. I spent the better part of the evening resisting. But then … I succumbed—hideous, detailed descriptions of wives cut into pieces and sent around town or stashed under bridges by their husbands, often doctors.

In the room overlooking the bluff, I sat and read. The mood was intensified by the thick fog that was presently enveloping the bluff and obscuring the view. I was dreading the moment I would finish. My only option, I knew, was to keep reading and rereading, and just not stop.

Though I lingered purposefully over each criminal act, savoring the occasional and extraordinary detail, I finished quickly. These terrible images—headless women, body parts washed up on the Thames, disemboweled torsos—populated the bluff. The lighthouse diminished in size, a claustrophobic energy entered the building.

I sat still, very still, listening to the late-night silence of the room. It was loud and tiring. I waited for a break, a way out, a pause in the feeling of terror that filled me. It came quickly when the electricity shut down and the building went dark. Seconds later the electric generator exploded into action, a twisted parody of my fear and helplessness. It was unbearably loud and intense. I laughed and laughed and then I froze. My muscles strained with immobility.

I sat in the dismal bare-bulb light staring into the darkness, into my reflection in the glass. Intermittent bursts of white swept past the window and over the bluff, racing around the room and washing over my face.

*

Photo: Roni Horn.

I’m standing on the mountain Kerlingarfjöll, high up in the interior of Iceland. A warm, sunbaked evening fills the air. The atmosphere is a lens, focusing the view into vivid and stunning clarity. The air is thin and transparent, so much so, it feels new. Things far away are as visible as those that are near. There’s little distinction between the two.

Looking around I can see the ocean way out there, in all directions. With a sense of omnipotence, I can also see everything in between. No haze, no dirt, no trees, nothing obscures the view. I am seeing all that is visible in each direction, as far as that direction goes. Only the curvature of the earth diminishes and eventually removes the most distant part of each view.

To the east the view is briefly interrupted by the mountain I’m standing on. But every little thing on the mountain stands out in magnified clarity too. The blades of grass, the grains of sand, the perfect pebbles, each rock, and every flower, and every part of every flower are brilliantly visible. I can see the smooth, rough, and granulated textures of all things: the earth, vegetation, and rocks. I see this simultaneously and without hierarchy. Every road, lava field, lake, and river, every glacier, mountain, boulder, and bridge, each holds its place in the view.

Provided it’s the right arctic atmosphere, you can stand almost anywhere on this island, not necessarily high up, and experience these deep views. The terrain is an ocean of expanse; an expanse interrupted only occasionally by a mountain or a glacier. And only rarely do buildings or vegetation interfere, and trees never do.

There are no trees in Iceland. Their absence brings out the remarkable nature of this landscape. The views here are the trees of Iceland. In other places no trees creates a vacuum, obscuring the view with longing and desire.

Iceland is young; some of the island is less than thirty years old. Surtsey was cooling its molten mass into the Atlantic Ocean within months of John F. Kennedy’s assassination in 1963. Iceland’s so young erosion hasn’t yet obscured the origin of things.

Youth and no trees reveal things rarely seen anywhere. Like how a place comes to be, continuously.

How the landscape takes shape.

How the lava flows and where it stops. And how many times it flows here or there, because each flow is a layer, looking like a single step in a staircase.

How these layers and steps now laminated into a solid mass tilt this way or that.

How the water emerges from underneath a lava field and forms a wall of waterfalls.

How the earth splits open in a miles-long, straight, v-shaped canyon.

How molten lava rides the rivers out to sea.

How boiling water spontaneously jumps out of the earth.

How basalt cools into accordion walls of architectural clarity and scale.

How lava flows over wet earth and becomes a field of breasts and cones that together create an undulating and sexy horizon.

How fjord mountains stop happening way up in the air like the blades of upturned knives and how these sharp mountains form a row of pinnacles like the teeth of a comb.

How a lava flow becomes a maze.

How a mountain breaks down into particles that settle into vast slopes in dazzling angles of repose.

How, precisely, tectonic plates—enormous pieces of global crust, come together exactly as one might expect the edges of some enormous crack to do.

The hows build up everywhere, forming a landscape of infinite depth and transparence. Each how takes you one step deeper, beyond appearance, beyond the simple visibility of things.

No trees. No trees introduces something as complex and necessary as trees themselves. But when this absence combines with the right atmospheric conditions, Iceland grants omniscience to the visitor free of superior forms.

Roni Horn is an artist and writer whose books include Another Water, Wonderwater (Alice Offshore), Weather Reports You, and Roni Horn aka Roni Horn.

Excerpted from Island Zombie: Iceland Writings , by Roni Horn. Copyright © 2020 by Roni Horn. Reprinted by permission of Princeton University Press.

Inhale the Darkness

Nina MacLaughlin’s newest column, Winter Solstice, will run for four weeks, finishing on the solstice on December 21.

Hilma Af Klint, The Swan (No 17), 1915-1914

Two boys strung the lights onto houses in Ohio. When nighttime arrived in the afternoon, they climbed their ladders. One held the loop and fed the cord to the other who reached and fastened, line of lights between them. This way they did their festive work, strung bulbs under gutters, rimmed front porches, edged the roofline trim—there they were at the peaks, making arrow-tips of light aimed at the big black night sky. They helixed little lights around lampposts, around and around the oak tree and the evergreen, passing the lights between them, breathing in pine needle, branches catching the collars of their coats, pitch sticky at the tips of their work gloves. Some bulbs were sharp and thorny, others round-fat egg drops. They looped the lights around the trees, lights dripped and draped as though the constellations themselves had gotten caught in the net of branches. When they finished the job, they’d knock on the door, bring the family out into the cold, ready?, and they’d flip the switch, ta-da!, and sometimes kids would leap and cheer and turn around at their parents smiling, eyes glittering, to see if they saw, too. And sometimes the parents made a sound, joy, relief, firework glow on their faces like summer. But it wasn’t summer, it was coming on Christmas, as Joni Mitchell sings, and the boys saw their breath as they worked, lighting up the darkness.

Last day of November and the dark this year is darker. We’re moving into winter. Henri Bosco describes the moment in his fevered novel Malicroix:

It was already the end of November … a time of extreme balance between the seasons, a miraculous moment when the world was poised on pure ridge. From there it seemed to cast a glance back at the aging autumn, still misty with its wild moods, to contemplate deadly winter from afar.

We’ll contemplate this deadly winter from right close up, we’re already almost in it.

I’m listening to sycamore leaves rustle down the sidewalk in front of my apartment. It’s somewhere in the forties. The wind’s voice has changed and the leaves are at their loudest now, last rattle before long quiet. The river I live near turns black in November. A recent midday on its banks, first snow—early—of the season, the river black and the fat flakes fell and the sky was the thick almost-white of the sky when it snows, which is one of my favorite things of being alive, seeing the sky almost-white when it snows. From the west, a pair of swans appeared, flying above the river, white above black, white against almost-white, and close enough to hear the thwap of their wide wings against the air and a guttural croaking from their throats, more amphibious than avian. A mental stillness as they flew by, a feeling of such luck, then a churn of associations—the swan’s position in alchemy as an initial confrontation with the soul; Leda and a swan-beak speculum; the ten-starred constellation Cygnus caught glittering in galactic branches.

And the swans of the artist and mystic Hilma af Klint, a white swan against a black background in mirror image with a black swan against a white background, beak to beak and wingtips touching at the black-white horizon line between them. Dark and light, warm and cold, underworld and Eden. Not one without the other, when it comes to the major forces of this world. Somehow Han Kang echoes the image in her wintery The White Book: “that first white cloud of escaping breath is proof we are living … Cold air rushes into dark lungs, soaks up the heat of our body, and is exhaled as perceptible form … out into the empty air.” Out of darkness, perceptible form, great swans of breath.

Dark makes its annual inhale of light. It seems night all the time now, and it’ll keep getting nighter as we spin toward the solstice on December twenty-first. If you follow the meteorological calendar, tomorrow, December one, is the first day of winter. If you follow the astrological calendar, calibrated by the position of the sun, winter begins at eight thirty in the morning on December twenty-first, when the earth’s northern hemisphere is tilted farthest away from the sun, when we’re delivered the longest night of the year. These are lampposts to string your lights around, ways of managing your time, systems to agree and believe in. There are other winter signals.

What’s the start of the season for you? Is it: the first time you see your breath; the first potato-chip crisp of ice on a puddle; the first snow; tinsel; Menorah; mistletoe; mug of hot chocolate; when the river freezes; when you hear a Christmas carol in CVS; see a wreath on a neighbor’s door; a candy cane; a persimmon; a pomegranate; eggnog in the dairy aisle; scarf around your throat; a certain pair of socks; the changed quality of blaze in sunset sky? Is it a creeping spider of malaise? A vague and frightening fuzz-edged feeling of hopelessness when the sun starts to sink too soon, a bottom giving way beneath you? A shadow at the back of the brain that, if you find yourself in too quiet a moment, gives an electric sizzle of static you can almost hear? A snarled black nest of fear in your chest and the upped urge to have another drink? The first fire? The first frost?

Loss is in the air. Summer’s juicy verdure gives way to something crisped and husky. The colors dull and the plants fuzz, release last seed, go black. There’s something cruel about it. On a plane some years ago, the stranger strapped in next to me talked about winter in Chicago. “You never been to Chicago in winter?” he said. “I’ve never been to Chicago,” I said. “Well we got a wind so cold we call it the hawk,” he said. It sounded like a mean thing.

Heat slips off, chased by the hawk, and the smolder has to come from within. Winter makes us know the hollows. Darkness creeps in from both sides and pushes us to that pure ridge, all the way exposed. Peer over, scope the abyss. The fear is ancient, part of our human-animal inheritance, the surging fury of survival: will I be warm enough, will I have enough to eat, will it keep getting darker, will the darkness swallow me, will it swallow us all together?

The gap this year feels wider, the fear pulsing at a different frequency. Loss has been the dominant condition for months now. “In a world of facts, death is merely one more fact,” writes the poet Octavio Paz. And we lump it in with the rest. The full moon in December is the Long Nights Moon; strings of incandescent mini lights strung around a porch rail use 408 watts of energy; the snow-white sap of the milkweed pod is toxic to most creatures, but not to monarch butterflies; you, I, they, brothers, sisters, parents, pals, children, strangers, loves, God bless us every one, one day all of us will not be anymore. One more fact in a world of facts. Turn around while I press it down between the cushions here.

What’s death in a world of stories? Is it merely one more story? Maybe in a world of stories, there’s a door that leads to the possibility of a different ending. Maybe in a world of stories, death is infinite potential, just another means of moving on. And on we go, absorbed into the wet, warm belly of eternity, back here as a robin or a wren, a pelvic bone in someone else’s skeleton, riding the underside of a cloud.

No matter what, it’s scary, yes?

Here you are. And you’re confused and frightened like the rest of us, angry maybe, too, but that’s just the fear again. A little mixed up about where you are, dangling between two eternities like a drop about to fall from the faucet. Grab a beer. There’s wine on the counter and glasses on the shelf. You’re looking backward to a source, you’re looking forward (but not too far), you’re looking for the warmth of understanding, the warmth of being understood.

The opposites are right now in tension, twinned and twined, the great cosmic tug. The tug is never stronger than in this moment, as we sink into the deepest part of darkness. A bashing against, a blurring with, a pulling away, and a drawing in. The boundaries are beginning to dissolve. Khaos emerged at the birth of the universe, preceding the rest of the primeval gods. A state of disordered darkness, a void where nothing was named. Her name meant gap, chasm, yawn. Absence. Form was exhaled from the lung of the darkness. Right now, darkness takes a deep breath in. Hold tight. We’re riding the backs of the swans. There’s no flying without land, no emptiness without an edge. What world are we living in? And yet:

Here you are.

Here you are, the winter tells us.

An offer and a fact.

Read Nina MacLaughlin’s series on Summer Solstice, Dawn, Sky Gazing, and November.

Nina MacLaughlin is a writer in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Her most recent book is Summer Solstice.

November 25, 2020

Remembering Jan Morris

“To be writing about a place you’ve got to be utterly selfish,” said the legendary travel writer Jan Morris in her Art of the Essay interview. “You’ve only got to think about the place that you’re writing. Your antenna must be out all the time picking up vibrations and details. If you’ve got somebody with you, especially somebody you’re fond of, it doesn’t work so well.” Although Morris, who died Friday at the age of ninety-four, preferred to travel alone, her writing radiates the qualities of an ideal companion: knowledgeable, witty, relaxed, and always up for an adventure. If you pricked a globe with pins indicating the places she explored throughout her work—Venice, Hong Kong, wide swaths of South Africa and Spain, and, of course, Wales, where she lived for much of her life with her wife, Elizabeth—it would never stop spinning. Morris was nearly as adventurous in her literary endeavors as she was in her travels, publishing more than forty books of history, memoir, essays, diaries, and even fiction. In a foreword to the expanded edition of Morris’s novel Hav, Ursula K. Le Guin writes, “Probably Morris, certainly her publisher, will not thank me for saying Hav is in fact science fiction, of a perfectly recognizable type and superb quality.” Morris was also responsible for a groundbreaking account of her own gender confirmation surgery, Conundrum (1974). A tremendously insightful writer till the end, she in recent years published a selection of her diaries, an excerpt of which appeared in the Summer 2018 issue of The Paris Review. In these personal accounts of her days, Morris writes about walking her “statutory thousand daily paces up the lane,” keeping a frayed copy of Montaigne’s essays in her old Honda Civic, and spending days in the garden. One entry consists simply of a poem about her life with Elizabeth:

In the north part of Wales there resided, we’re told,

Two elderly persons who, as they grew old,

Being tough and strong-minded, resolute ladies,

Observing their path toward heaven or hades,

Said they’d still stick together, whatever it meant,

Whatever bad fortune, or good fortune, sent.

They’d rely upon Love, which they happened to share,

Which went with them always, wherever they were.

And if it should happen that one kicked the bucket,

Why, the other would simply say “Bother!”

(Not “F— it!” for both were too ladylike ever to swear .… )

Below, three of Morris’s longtime colleagues remember her charm:

Jan Morris.

My fondest memories of Jan Morris are of my visits to her home in North Wales. She and her wife, Elizabeth, lived for many years in a plas, a big house, and when this became too big they renovated the stable block and moved in there.

Wales mattered to Jan. In midlife, and at more or less the same time as her gender reassignment, she embraced what she called Welsh Republicanism. Her home, Trefan Morys, is in a remote area near the town of Criccieth. You leave the main road, take a long, rutted drive, negotiate the narrow entrance in a high stone wall, and you are suddenly in an enchanted space. Elizabeth was the architect of the garden and Jan the interior designer. You enter the house through a two-part stable door (Jan always greeting you with the words, “Not today, thank you”), into a cozy kitchen, and then the main downstairs room. The walls are lined with eight thousand books, including specially leather-bound editions of Jan’s own. Up the stairs there is another long room, with an old-fashioned stove in the middle. Here are more books, but this space is given over mainly to memorabilia and paintings. Pride of place is given to a six-foot-long painting of Venice, done by Jan, in which every detail of the miraculous city is rendered (including tiny portraits of the two eldest sons, who were very young at the time Jan painted it). Model ships hang from the ceiling, and paintings of ships adorn the walls. Jan loved ships from the time she spied them, as a child, through a telescope as they passed through the Bristol Channel near her family’s home.

In the bedroom, on the inside of a wardrobe door, is a full-length portrait of someone called John “Jackie” Fisher. Fisher was a legendary admiral-in-chief of the Royal Navy in the early part of the twentieth century. Fisher presented a haunting combination of “the suave, the sneering and the self-amused.” Jan wrote a book about him, Fisher’s Face, in which she stated that she would like either to have been Jackie Fisher or to have had an affair with him. She hoped to be able to have that affair in the afterlife, and now that she is gone, I’m sure she will. Jan loved to invite visitors into the bedroom, open the wardrobe door with a flourish, and stand next to her hero’s image. It was one of her many self-dramatizing but also self-mocking gestures.

The only portrait of Jan herself is a sculpted bust of her head, done by a friend, which stands on the deck outside the bedroom in one corner, and in the other is a bust of, yes, Jackie Fisher. The impression of egotism, benign and self-deprecating yet nonetheless very powerful, is evident throughout Jan’s house. Equally strongly expressed is Elizabeth’s modesty and self-effacement. Elizabeth always represented the safe haven that Jan could return to after her adventures. She is still alive, but when she dies their gravestone will read: “Here lie two friends, Jan and Elizabeth, at the end of one life.”

Jan was one of the great writers of her time, a wonderful exponent of English prose who fashioned a distinctive style that was elegant, fastidious, supple, and, at times, gloriously gaudy. It’s hardly an exaggeration to say that she imposed her personality on the entire world. I don’t think there will ever again be anyone quite like her.The story of her gender reassignment and the stories of her exploits as an ace journalist are fascinating, but in the end she was a writer.

—Derek Johns, Jan Morris’s literary agent for two decades, and the author of Ariel: A Literary Life of Jan Morris

Five years ago, when Jan was, I think, eighty-nine, I met her in Wales, and she drove me to lunch. She was a fantastic driver—impressively fast and skillful, not at all what you might imagine from an intensely thoughtful, softly spoken elderly woman. Along the way she told me an anecdote about her mother that was so funny and outrageous I am still not sure whether it was true, or whether she made it up on the spot to entertain me. Either way it is probably not printable. She was perhaps the best person I have ever met. Her spirit and ethos have guided and comforted me since before that drive, and they do still.

—Sophie Scard, an agent at Jan Morris’s literary agency

When I started working at Faber in 2000, as an editorial assistant, one of the first books I really got to work on was Jan’s masterful Trieste and the Meaning of Nowhere. We somewhat fancifully billed it at the time as her final book (this may be apocryphal, but I’m pretty sure I remember Jan saying, with a smile, that it would be good for publicity). One year later I helped go through all of her work to compile A Writer’s World—her greatest hits, if you like, of fifty years of journalism and travel writing. Quite aside from delivering one of the greatest scoops of all time—successfully coding the news of Hilary’s conquest of Everest back to the Times in London to run on the morning of the Queen’s coronation—here was a writer who witnessed and reported on the Eichmann trial, the Suez Crisis, the fall of the Berlin Wall, the Lewisham riots, and the handover of Hong Kong, among so many other landmark moments of the latter half of the twentieth century.

More recently, I was lucky enough to acquire and edit her final books—two volumes of diaries, In My Mind’s Eye and Thinking Again. Started in her ninetieth year, these not-quite-daily missives are quintessentially Jan Morris in tone—at once beautifully melancholic and delighted with life, with all its absurdities and blessings. They really are wonderful, written with her keen-eyed observation and acceptance of the fact that despite being one of the most traveled people in the world she wouldn’t be traveling beyond her own village again. There is also something else at play, lurking between the lines, a glint-in-her-eye quality that was ever present in her writing, from Coast to Coast in 1956 to Thinking Again sixty-four years later. I remember this quality well from real life, too, as anyone who met her or saw one of her memorable live readings may also. The last time I saw Jan in person was when her long-term agent, Derek Johns, and I visited her and Elizabeth at their home in Wales to deliver a finished copy of In My Mind’s Eye. We went out for dinner that night to her local pub, and on the way she said delightedly that they did the best homemade marmalade and she was going to treat me to a jar. When we arrived and she asked the landlord for two he informed her there was, sadly, only one left. “Sorry,” she said, taking the jar and turning to me with a smile, “this one’s mine, you’ll just have to come and visit again.”

—Angus Cargill, Jan Morris’s editor at Faber

Read Jan Morris’s Art of the Essay interview in our Summer 1997 issue

Read excerpts from Jan Morris’s diaries in our Summer 2018 issue

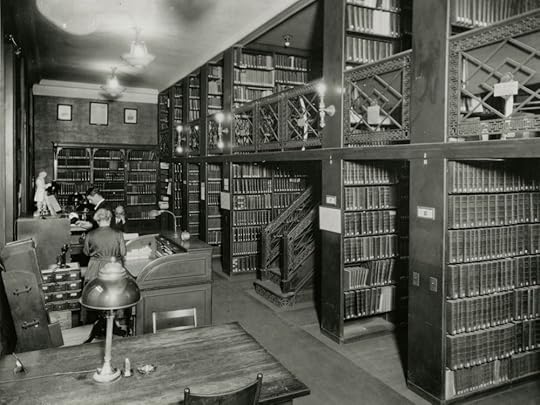

The Libraries of My Life

The Chemists’ Club library in New York, New York, ca. 1920. Photo courtesy of Science History Institute. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

I was thirteen and wanted to work. Someone told me that you could get paid to referee basketball games and where to go to find out about such weekend employment. I needed income to bolster my collections of stamps and Sherlock Holmes novels. I vaguely remember going to an office full of adolescents queueing in front of a young man who looked every inch an administrator. When my turn came, he asked me if I had any experience and I lied. I left that place with details of a game that would be played two days later, and the promise of 700 pesetas in cash. Nowadays, if a thirteen-year-old wants to research something he’s ignorant about, he’ll go to YouTube. That same afternoon I bought a whistle in a sports shop and went to the library.

I wasn’t at all enlightened by the two books I found about the rules of basketball, one of which had illustrations, despite my notes and little diagrams, and my Friday afternoon study sessions; but I was very lucky, and on Saturday morning the local coach explained from the sidelines the rudiments of a sport that, up to that point, I had practiced with very little knowledge of its theory.

My practical training came from the street and the school playground. My other knowledge, the abstract kind, stood on the shelves of the Biblioteca Popular de la Caixa Laietana, the only library I had access to at the time in Mataró, the small city where I was brought up. I must have started going to its reading rooms at the start of primary school, in sixth or seventh grade. That’s when I began to read systematically. I had the entire collection of The Happy Hollisters at home, and Tintin, The Extraordinary Adventures of Massagran, Asterix and Obelix, and Alfred Hitchcock and the Three Investigators at the library. Arthur Conan Doyle and Agatha Christie were devoured in both places. When my father began to work for the Readers’ Circle in the afternoons, the first thing I did was buy the Hercule Poirot and Miss Marple novels I hadn’t yet read. That’s probably when my desire to own books began.

The Biblioteca Popular de la Caixa Laietana acted as a surrogate nursery. I don’t think children today have to write as much as we did in the eighties. Long, typed-out projects on Japan and the French Revolution, on bees and the different parts of flowers, projects that were a perfect excuse to research in the shelves of a library that seemed, then, infinite and boundless; much greater than my imagination, then anchored in my neighborhood and still restricted to three television channels and the twenty-five books in my parents’ tiny library. I did my homework, researched for a while, and still had time to read a whole comic or a couple of chapters of a novel in whatever detective series I happened to be enjoying. Some children behaved badly; I didn’t. The twenty-five-year-old librarian, a pleasant, rather custodial type, who was tall, though not overly so, kept an eye on them, but not on me. I’d go to him when I needed to find a book I couldn’t track down. I also began to hassle Carme, the other young librarian, who saved us from her older, pricklier colleagues with clever bibliographical questions: “Any book on pollen that doesn’t just repeat what all the encyclopedias say?”

I mentioned my parents’ micro-library. “Twenty-five books,” I said. I should explain that Spain’s transition from dictatorship was led by the savings banks. Municipal governments, busy with speculation and urban development, delegated culture and social services to the banks. Mataró was a textbook case: most exhibitions, museums, and senior centers, as well as the only library in a city of a hundred thousand inhabitants, depended on the Laietana Savings Bank. At the beginning of this century, during my (now real) research into Bishop Josep Benet Serra for my book Australia: A Journey, Carme, who has since become an exceptional librarian in Mataró, opened the doors of the Mataró holdings to me. I wasn’t then aware of that defining metaphor, the 2008 economic crisis hadn’t yet revealed the emperor’s nakedness: Mataró’s document holdings, its historical memory, wasn’t in the municipal archive, wasn’t in the public library, but in the heart of the Laietana Saving Bank’s People’s Library. During the Spanish transition to democracy, the so-called duty to look after culture was assumed by the savings banks without anyone ever challenging them; it only became evident when one of them published a book, which they sent to all their customers as a free gift. I have one in my library that I inherited or purloined from my parents’ house, Alexandre Cirici’s Picasso: His Life and Work. The title page says: “A gift from the savings bank of Catalonia.” It is the only institutional message. Although it’s hard to credit, there is no prologue by a politician or banker. There was no need to justify a gesture that was seen as natural. Over half of my parents’ books were gifts from banks.

Years later, a childhood friend of my brother died in a traffic accident. Consumed by grief, his mother told mine that there was a woman in her support group who carried a newspaper cutting in her purse. She took it out. She read it aloud. Those words made her feel proud of her son, whom she’d so missed since the accident had killed him, his wife, and their two children. Those words helped her to live without her grandchildren, the children of a librarian disguised as a friendly policeman. Those words, partly erased by all those I’ve written since, were mine for a short while: now they belong to newspaper libraries that are gradually disappearing, because it’s likely that, even for that mother, who will have partially overcome her grief, they are simply a memory. I’m not sure whether, in that obituary, I evoked those Saturday afternoons in a school playground, when I’d left the Mataró library for the library of the Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona, where the friends of the not-so-young librarian and my friends and I played basketball together.

*

The other day I went down to the library of the university where I work to look for a copy of André Breton’s Nadja, which I needed for a class, and which I couldn’t find in my own library. There it was, in the same place it must have been in 1998, when I read all the surrealist books I could find, interested as I was in their theories about love (and my practice of it): Mobile by Michel Butor. But I didn’t see it then. I did see it seven years later, in the University of Chicago Library, when I had the whole winter ahead of me to read. I sense that bookshops display the books in their possession in a seductive, almost obscene, manner because they want to sell them to you; conversely, libraries hide or at least camouflage them, as if they were content just to hoard. But it’s also true that it’s your gaze that scans the books’ spines, that it’s your attentiveness or whim that determines whether the titles and authors are revealed or go unnoticed.

The Pompeu Fabra University Library was very new when I started my first year in humanities. It was so young its sections didn’t even have names. As a library matures, it begins to house donations, collections, archives, each bearing the name of a donor, a scholar, or someone retired or dead. In relation to a library, we associate the verb “to exhaust” with Borges. I am someone who exhausts bookshops and libraries; I love to spend hours looking at sections, shelf by shelf; the books, spine by spine. I have done this on rainy days in many of the world’s cities. On snowy days, only in one: Chicago. I have never felt so lonely as in those weeks at the beginning of 2005. I came to spend twelve or thirteen hours in that enormous library. Before I discovered the interlibrary loan system that gives you access to any book in any library in the United States, I spent many hours in the Spanish literature section, in search of travel books and essay collections you can only find in that way, via the pre-digital google of meandering around a labyrinth of books. My Ariadne’s thread: all those titles and pages, their secret disarray. Loneliness; there is no worse minotaur.

Using a neophyte library like the one at my university, Chicago’s—and before that, the University of Barcelona’s—alerted me to a key cultural concept: holdings. That possible memory of a particular state of culture and the world. That fragment you will never fully know of a whole that can never be reassembled. Holdings are often bottomless pits, places where unpublished manuscripts and the most important letters can exist without being seen (or worse, read) by anyone. At the pit bottom of the University of Chicago’s history, or simply on the foundation stone of its book collection, we find the first of many names to come: William Rainey Harper. His erudition and pedagogical experiments reached the ears of Rockefeller, who promised him $600,000 to create a center for higher education in the Midwest that could compete with Yale. In the end, $80 million came the University of Chicago’s way, because, in addition to writing Greek and Hebrew textbooks, Harper was spinning strategies so that the poor, and those who worked full-time, could get access to higher education. He was an excellent manager. He created the university press that survives to this day. On the other hand, the William Rainey Harper Memorial Library was closed in 2009. The message on LibraryThing couldn’t be starker:

University of Chicago—William Rainey Harper Library

Status: Defunct

Type: Library

Web site: www.lib.uchicago.edu/e/harper/

Description: On June 12 2009, the William Rainey Harper Memorial Library was closed, and its collections transferred to Regenstein Library.

Defunct library. The demise of a library as the final death of an individual who survived almost a century after his actual death. It makes you think there’s no word more pretentious than university.

In one of his now forgotten articles about literature, which I finally read the other day in the humanities library of the university where I work, Michel Butor writes: “a library offers us the world, but offers us a fake world, sometimes there are cracks, and reality rebels against books, through our eyes, a few words or even certain books, something strange that points to us and triggers the feeling that we are shut in.” I think he is right: a bookshop gives material form to the Platonic, capitalist idea of freedom, whereas a library is often more aristocratic and can sometimes be transformed “into a prison.” In our homes, thanks to, or through the fault of, bookshops, we imitate the libraries we have visited from childhood and construct our own bookish topography. Butor says: “By adding books we try to re-construct the whole surface, so windows appear.” In reality we add centimeters of thickness to the walls of our own labyrinth.

*

Until now I had often been unable to find dispensable books, ones you could almost do without, on my own shelves; but the day I couldn’t find Nadja, one of those novels I have regularly dipped into over more than ten years, like Don Quixote, Heart of Darkness, Julio Cortázar’s Hopscotch, Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain, or David Grossman’s See Under: Love, I was forced to start worrying. In his famous essay “Unpacking My Library: A Talk about Book Collecting,” the urban nomad Walter Benjamin says that any collection oscillates between order and disorder. The like-minded Georges Perec sets out, in Thoughts of Sorts, an unarguable principle: “A library that is orderly, becomes disorderly: it’s the example I was given to explain entropy and I have verified it several times experimentally.” I must admit that in the four-and-a-half years that have passed since I moved to a flat in the Barcelona Ensanche I have accumulated books, and the odd set of shelves, without reordering my library’s overall structure. And now everything is horribly chaotic.

The world’s logic is mimetic. Everything works by imitation. The originality of our personality is but a complex combination of options we have borrowed from various models over time. My library is a response to the void of my parents’ house: there are traces of all the public libraries I’ve visited since childhood. The other day I came across some photocopied pages of Paul Bowles’s diary, pages that bore the Caixa Laietana stamp. I also hoard the books I’ve bought from the University of Chicago Library, which periodically gets rid of books in a fleeting—weekend—conversion of the library into a second-hand bookshop. When I last moved house, I arranged my library by language tradition and remoteness of interest. I keep next to my desk books about literary theory, communication, travel, and the city. Two feet behind those books is Spanish literature, in alphabetical order. Opposite them, three or four feet away, world literature. You must walk to the adjacent room, the dining room, to access historical, film, and philosophical essays, biographies and dictionaries (made even more distant by their online versions). I keep comics and travel books in the passageway. And in the guest room, finally, Catalan literature, essays on love, my books on Paul Celan, several hundred Latin American chronicles, as well as two copies of each of the books I have written or contributed to. Logic and caprice intertwine in a library that has occupied different spaces as the number of books grows and visits to Ikea are made. The bookcases in the study are solid wood: my parents, who still believe in solidity, bought them with my money to house the prototype of this library when I went traveling in 2003. But the rest of the apartment is filled with Billy shelves bent under their load, and gradually coming apart as a result of my lack of dexterity, which condemned them to degeneration the moment I screwed them so poorly together; I may be a more or less competent reader, but I’m a hopeless DIYer. My childhood toys included a microscope, mineral and physics kits, as well as a toolbox: I hardly need to say I didn’t end up specializing in carpentry or the sciences.

“Every collection is a theatre of memories, a dramatization and staging of individual and collective pasts, of a childhood remembered and a souvenir after death,” Philipp Blom wrote in To Have and to Hold: An Intimate History of Collectors and Collecting, adding: “it is more than a symbolic presence: it is a transubstantiation.” All those books that surround me every day allow me to feel near to myself—to what I was, to that reader who kept growing, changing, adding layers—and to the information and ideas they contain. Or that they only suggest. Or that they only hyperlink: many of my books are planets orbiting around thinkers, writers, and historical figures I don’t know firsthand, but that are friends of friends, involuntary accomplices, shifting pieces in a complex system of potential knowledge.

Friends, acquaintances, future contacts. Those are the three labels around which I’m going to organize my library, I decide as I finish writing this essay, when we rearrange the house next month for happy, familial reasons. I will dismantle it in order to reinvent it. I shall place near me only those writers and books with which I enjoy a more or less close friendship. These will stay in (or will enter) the study. They’ll surround me, as their memory already does, or that of their authors. I will keep acquaintances in the dining room, the ones I respect and feel fondly toward. Most of the books I haven’t read, and that I don’t know if I ever will, will be given away and sacrificed; those that remain, in the passageway, will await their turn, patiently, distantly, like people you don’t know, whom you may never know.

Aby Warburg, founder of the twentieth century’s most fascinating library, placed a single word over the entrance: “Mnemosyne.” His books and prints moved and migrated according to dynamic relationships of affinity and sympathy, creating provisional collages and leaving it to readers to imagine the links between them. As far as he was concerned, a library’s only reason to exist was as a place where one could stroll and wander. In the stroller’s gaze, images and texts fired invisible arrows at each other, neuronal synopses: the electricity nourishing the history of form and art. “It’s not merely a collection of books, but a collection of problems,” said Toni Cassirer, the wife of German philosopher Ernst Cassirer, after paying it a visit: a library only has meaning if it soothes as much as it disturbs, if it resolves, but above all, poses riddles and challenges. Cohabiting with a personal library means that you’re not surrendering, that you will always have fewer books read than books left to read, that books that keep company with one another are chains of meanings, mutating contexts, questions that change according to tone and response. A library must be heterodox: only the combining of diverse elements, of problematic relationships, can lead to original thought. Many of those who saw Warburg’s library described it as a labyrinth.

In his introduction to Warburg Continuatus: The Description of a Library, Fernando Checa writes: “As a theatre and arena of the sciences, the Library is also a real ‘theatre of memory.’ ” Which is what this essay has attempted to be. “There will never be a door,” wrote Borges in a poem precisely entitled “Labyrinth,” “You are inside / and the castle encompasses the universe / and has neither obverse nor reverse, neither external wall nor secret centre.”

—Translated from the Spanish by Peter Bush

Jorge Carrión’s Bookshops: A Reader’s History, published by Biblioasis in 2017, was universally acclaimed and has appeared in thirteen languages. He is the author of three novels, including Los muertos, which won the 2011 Festival de Chambéry. Carrión’s journalism appears in the Spanish-language edition of the New York Times and many other newspapers in Europe and the Americas. He lives in Barcelona, where he is the director of the creative writing program at Pompeu Fabra University.

Peter Bush’s recent translations include Teresa Solana’s The First Prehistoric Serial Killer and Other Stories, his selection of Barcelona Tales from Cervantes to Najat El Hachmi, and Leonardo Padura’s Grab a Snake by the Tail. In press are Josep Pla’s Salt Water and Quim Monzó’s Why, Why, Why?; in process, Balzac’s The Lily in the Valley and a selection of Salvador Dalí’s letters. He lives in Oxford, UK.

Excerpted from Against Amazon and Other Essays . Used with the permission of the publisher, Biblioasis. Copyright © Jorge Carrión, 2019. Translation copyright © Peter Bush, 2020. Reprinted by permission of Biblioasis.

November 24, 2020

Redux: A Dining Room Deserted

Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

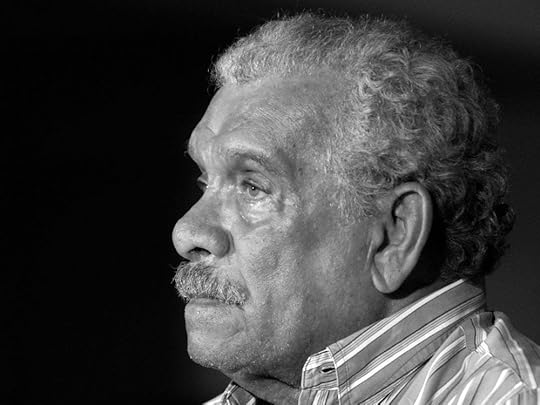

Derek Walcott, ca. 2012. Photo: Jorge Mejía Peralta.

This week, The Paris Review approaches this strange and lonely holiday season with a feeling of gratitude. Read on for Derek Walcott’s Art of Poetry interview, Nick Fuller Googins’s short story “The Doors,” and Pablo Neruda’s poem “Melancholy inside Families.”

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, and poems, why not subscribe to The Paris Review? Or take advantage of our new subscription bundle, bringing you four issues of the print magazine, access to our full sixty-seven-year digital archive, and our new TriBeCa tote for only $69 (plus free shipping!). And for as long as we’re flattening the curve, The Paris Review will be sending out a new weekly newsletter, The Art of Distance, featuring unlocked archival selections, dispatches from the Daily, and efforts from our peer organizations. Read the latest edition here, and then sign up for more.

Derek Walcott, The Art of Poetry No. 37

Issue no. 101, Winter 1986

Ultimately, it’s what Yeats says: “Such a sweetness flows into the breast that we laugh at everything and everything we look upon is blessed.” That’s always there. It’s a benediction, a transference. It’s gratitude, really. The more of that a poet keeps, the more genuine his nature. I’ve always felt that sense of gratitude. I’ve never felt equal to it in terms of my writing, but I’ve never felt that I was ever less than that.

Photo: Aaron Burden. CC0, via Wikimedia Commons.

The Doors

By Nick Fuller Googins

Issue no. 228, Spring 2019

Niko is a natural. With his help the beginners improve their line by leaps and bounds for instance facing the front most of the time now and usually remembering to hold the railing on the stairs. I teach him my modified sleeper hold. Double-teaming the beginners we have them snoring by one thirty every afternoon sometimes even earlier. Then we sit in the quiet nap-time darkness and guard against Nightworld and yes it is true that I would not mind if Niko thanked me for taking him under my wing but I realize that I never thanked him for taking me under his wing. And maybe our mutual gratitude is a silently understood kind of mutual gratitude but then again what if it is not?

Thanks brother, I say whispering so as not to wake the beginners.

For what? he whispers back.

For everything, I say.

Don’t say that, he says.

But I mean it, I say.

So do I, he says.

I don’t push him. The gymnasium lights are dim but not so dim that they don’t reflect a little watery in his eyes.

Melancholy inside Families

By Pablo Neruda

Issue no. 39, Fall 1966

I keep a blue bottle.

Inside it an ear and a portrait.

When the night dominates

the feathers of the owl,

when the hoarse cherry tree

rips out its lips and makes menacing gestures

with rinds which the ocean wind often perforates—

then I know that there are immense expanses hidden from us,

quartz in slugs,

ooze,

blue waters for a battle,

much silence, many ore-veins

of withdrawals and camphor,

fallen things, medallions, kindnesses,

parachutes, kisses.

It is only the passage from one day to another,

a single bottle moving over the seas,

and a dining room where roses arrive,

a dining room deserted

as a fish-bone: I am speaking of

a smashed cup, a curtain, at the end

of a deserted room through which a river passes

dragging along the stones. It is a house

set on the foundations of the rain,

a house of two floors with the required number of windows,

and climbing vines faithful in every particular …

And to read more from the Paris Review archives, make sure to subscribe! In addition to four print issues per year, you’ll also receive complete digital access to our sixty-seven years’ worth of archives. Or take advantage of our new subscription bundle, bringing you four issues of the print magazine, access to our full sixty-seven-year digital archive, and our new TriBeCa tote for only $69 (plus free shipping!).

Notes from the Bathysphere

William Beebe and Gloria Hollister inspect the bathysphere. © Wildlife Conservation Society. Reproduced by permission of the WCS Archives.

I’m writing from the outskirts of the small town of Tarapoto, in northeastern Peru. My ostensibly short trip here last March intersected with the declaration of a state of emergency: complete shutdown of domestic travel, strict curfew, international borders sealed. There were expensive “humanitarian flights” requiring government permission to travel to Lima; otherwise, it was impossible to move. This was meant to keep the virus out. By midsummer the situation improved elsewhere while Peru was suddenly in the global epicenter, and lockdown was meant to keep the virus in. Now the situation is reversing again, travel restrictions are loosening, and after eight months, I’m faced with the option of heading home.

Before the pandemic, I was living in Harlem, teaching at City College, and working on a book about the writings that remain from the bathysphere dives—strange, poetic texts that constitute the first eyewitness account of the deep ocean. The bathysphere was a four-and-a-half-foot steel ball fitted with circular, three-inch quartz windows, the first vessel that could go far underwater. Launching from the small island of Nonsuch, in the Bermuda archipelago, in 1930, the ball was winched off a vessel called the Ready and lowered on a steel cable. It eventually sunk to below three thousand feet, exponentially deeper than any previous dives.

Folded up inside the ball was William Beebe, a zoologist and popular nonfiction writer. When the dives began, he was already famous for his research on pheasants and his account of a recent trip to the Galápagos, where he’d witnessed the eruption of a volcano. His 1934 book on the bathysphere, Half Mile Down, straddles science writing, history, and a kind of secular mysticism, rich with observation but oriented toward the failure of language, the inexpressibility of experience.

I spent much of last winter in the basement of the Firestone Library in Princeton capturing Beebe’s personal papers—decades of his journals, correspondence, unpublished writings, notes and diagrams, fan mail from Rudyard Kipling (who prophesies submersible drones that stream video) and Arthur Conan Doyle (who wonders if Beebe has discovered Atlantis). Throughout most of the ensuing year, I sorted through these files, trying to make some order at a time when the world, and my life, were in disarray.

I’ve waited out this strange period in a little riverside lodge in the Amazonian Andes, a walled garden of hummingbirds and tamarin monkeys, tarantulas and poisonous ants. Along with the two owners and three staff members, I’ve lived mostly with four other New Yorkers: a molecular biologist, an ad agent, a psychotherapist, and a firefighter. We’ve had access to good food and decent Wi-Fi, and on hot, rainless days we could splash around in the river. As the viral outbreak and vile government wrought havoc in the U.S., we felt lucky to be here. Then, when police violence brought about mass protests, we wished we could march, too. By now it feels like this patch of high jungle is simply where we live, and the prospect of heading home is disconcerting. What are we going back to?

Among Beebe’s late-career notes, made in Trinidad, is a sheet that reads: “New type of Society. That of Wind.” He describes insects and other flying animals that aggregate on the lee side of a ridge during a gale: hawks and wasps and spiders, disparate creatures that otherwise do not spend time together, forced into partnership “by the blow which wrecks their attempts to fly.”

And I think: that’s us—locked down together until we form a family, immobile in the windblown shadow of a rock.

The walled garden in Peru. Photo: Brad Fox.

My first contact with Beebe’s writing was a fragment from Half Mile Down in which he describes one of the bathysphere’s first deep dives. He writes of his delight in witnessing bioluminescence—this was the first time anyone had seen the deepwater effects of animal light. He was thrilled to see so much life, so many unfamiliar species or species he’d only seen dragged up in a dredge.

But as much as his zoologist’s mind was taken with this sighting of marine animals, he was even more stunned by the effects of light and color. As he descended and the reds and oranges, all the warmer hues of the spectrum, were absorbed, the cool blue of the sea seemed to permeate his being. The bathysphere approached two thousand feet, the depth beyond which sunlight does not reach, and the blue seemed to intensify rather than fade into darkness. He was sure he could read by its light, until he glanced at a page and found it perfectly opaque.

This counterintuitive phenomenon bewildered Beebe. He sunk into a world seemingly created “of a single vibration.” Crawling out of the ball after surfacing, the scientist found himself once again in the familiar light of day. But the yellow of the sun, he wrote, “can never hereafter be as wonderful as blue can be.”

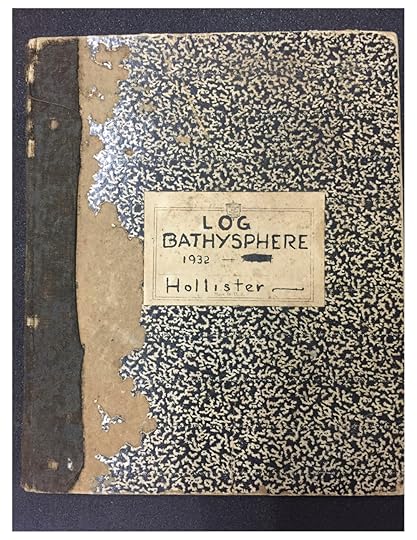

It was this sense of visionary encounter that inspired me to spend time with the bathysphere logbooks, three canvas-bound notebooks now stored in the basement of the Bronx Zoo. They contain the notes written by Beebe’s colleague Gloria Hollister, an accomplished scientist herself, who had developed a method of dyeing fish so as to see their internal structure without dissection. Hollister also made record-breaking dives in the bathysphere, but during most of the expeditions, she was aboard the Ready, listening to Beebe through a simple telephone, doing her best to note his faltering descriptions of what appeared outside the ball’s quartz windows:

1050 ft. blacker than blackest midnight yet brilliant

1150 beam of light showing clearly—light on.

1200 Idiacanthus. Two Astronesthes.

1250 Fish 5-inch-long shapes like Stomias

3-inch shrimps absolutely white

positive saw Argyropelecus in beam of light

2 luminous jelly pale white

1300 About 6 or 8 shrimps around

50 or 100 lights like fireflies

small squid in beam of light

seems to have no lights gone down for fish.

Cyclothones. Two-inch shrimps.

1350 Light very pale

temp. 72

1400 Looking straight down very black

black as hell

For Beebe, to look into the depths below, with the beam off, when there were no bioluminescent creatures to flash and display themselves, was to contemplate a darkness for which such words were inadequate. As he describes it in Half Mile Down, the blackness called all surface-world comparisons into question. As he sank, sometimes he simply repeated the word rhythmically to Hollister: “black, black, black, black.”

When he turned on the beam of the bathysphere, it shone a distinct yellow. At times he sat simply soaking in that color, trying to draw it into his being. But the moment the light switched off, it was as if it had never been. There had never been daylight, no streaks of illuminated clouds in twilight, or any relative darkness of a midnight in the jungle.

If the blue he encountered on the first dives was so blue as to permanently alter the yellowness of the sun, here was a black so black it called his very existence into question. This fecund and hungry vacuum split logic into impotent flagella, detached from the bodies they were meant to move. The comparisons of the human mind, its clawing after orientation, evaporated.

At such times he again remembered that he was alive, that barring an accident he would return to the surface, and that the only other humans who had entered these abyssal depths were the decomposed bodies of drowned sea-goers. He was truly on a trip through the underworld, an idea that had haunted humans for thousands of years. Now it was done, and reasoning about it, even talking about it, was useless.

But then a glow floated into view and pulsed with strange light. Stranger than anything he could have conceived. And in this illumination, the contour of a body emerged. A shape with fins or pulsing membranes, eyes or teeth or threadlike networks of tissue. And in his perplexity, he experienced the simple thrill of spotting a new species. He attempted to render it in language as best he could—“a Punch-and-Judy head, with a face which is no face”—before it swam away or drifted out of view. These sightings lit up his scientist’s brain with delight.

But still, he saw the frailty, even absurdity of his situation: the Ready rocking on the surf south of Nonsuch, a strand of steel and wire leading down through the vanishing reds and yellows to his lonely perch, sealed against the crushing pressure of the water, like a capsule in distant space about to be extinguished by a galactic explosion.

When he thought about it later, he concluded that his only contribution to science and literature was that he’d been able to testify: “At a depth of a quarter of a mile. A luminous fish is outside the window.”

The 1932 logbook for Beebe and Hollister’s bathysphere expeditions. © Wildlife Conservation Society. Reproduced by permission of the WCS Archives.