The Paris Review's Blog, page 135

December 8, 2020

Redux: A Point of Coincidence

Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

This week, The Paris Review is celebrating the release of the Winter 2020 issue by highlighting three contributors who have appeared in previous issues. Read on for Claudia Rankine’s Art of Poetry interview, György Dragomán’s short story “End of the World,” and Arthur Sze’s poem “Streamers.”

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, and poems, why not subscribe to The Paris Review? Or take advantage of our new subscription bundle, bringing you four issues of the print magazine, access to our full sixty-seven-year digital archive, and our new TriBeCa tote for only $69 (plus free shipping!). And for as long as we’re flattening the curve, The Paris Review will be sending out a new weekly newsletter, The Art of Distance, featuring unlocked archival selections, dispatches from the Daily, and efforts from our peer organizations. Read the latest edition here, and then sign up for more.

Claudia Rankine, The Art of Poetry No. 102

Issue no. 219, Winter 2016

The question is, How do you get to an authentic emotional place? I’m often listening not for what is being told to me but for what resides behind the narrative. What is the feeling for the thing that’s being told to me? One of the reasons I work in book-length projects, instead of individual poems, is because I don’t trust the authenticity of any given moment by itself.

Photo: Ginny. CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...), via Wikimedia Commons.

End of the World

By György Dragomán, translated by Paul Olchváry

Issue no. 183, Winter 2007

Coach Gica tended to us goalies specially, he made us show up at every practice an hour early and mainly had us do speed drills, plus we had to jump a lot and dive, jump and dive, jump and dive, and he had this goalie-terrorizing machine, he came up with it himself and the workers at the Ironworks made it for him, a soccer ball was put up on the end of this long iron pipe, the ball was filled with sand, and that’s what he shot at us, the whole contraption was built onto an axle it revolved around, throwing that sand-packed ball with no mercy, and Janika and I knew that if we didn’t catch it, it would hit us in the head and break our bones, other kids had already died in Coach Gica’s hands, so they said, which is why he became a coach for the junior team, the adult players couldn’t stand his heavy-handedness, one time they caught him and knocked half his brains out, and since then he wasn’t allowed to coach the Ironworks’ adult team but could work only with us eleven and twelve year olds.

Photo: Latemplanza. CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...), via Wikimedia Commons.

Streamers

By Arthur Sze

Issue no. 116, Fall 1990

As an archaeologist unearths a mask with opercular teeth

and abalone eyes, someone throws a broken fan and extension cords

into a dumpster. A point of coincidence exists in the mind

resembling the tension between a denotation and its stretch

of definition: aurora: a luminous phenomenon consisting

of streamers or arches of light appearing in the upper atmosphere

of a planet’s polar regions, caused by the emission of light

from atoms excited by electrons accelerated along the planet’s

magnetic field lines. The mind’s magnetic field lines.

When the red shimmering in the huge dome of sky stops,

a violet flare is already arcing up and across, while a man

foraging a dumpster in Cleveland finds some celery and charred fat.

Hunger, angst: the blue shimmer of emotion, water speeding

through a canyon; to see only to know: to wake finding

a lug nut, ticket stub, string, personal card, ink smear, $2.76 …

And to read more from the Paris Review archives, make sure to subscribe! In addition to four print issues per year, you’ll also receive complete digital access to our sixty-seven years’ worth of archives. Or take advantage of our new subscription bundle, bringing you four issues of the print magazine, access to our full sixty-seven-year digital archive, and our new TriBeCa tote for only $69 (plus free shipping!).

What We Know of Sappho

Fragment of parchment preserving parts of several poems by Sappho. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

As Nebuchadnezzar II is plundering Jerusalem, Solon ruling Athens, Phoenician seafarers circumnavigating the African continent for the first time, and Anaximander postulating that an indefinite primal matter is the origin of all things and that the soul is air-like in nature, Sappho writes:

He seems to me equal to the gods that man

whoever he is who opposite you

sits and listens close

….to your sweet speaking

and lovely laughing—oh it

puts the heart in my chest on wings

for when I look at you, even a moment, no speaking

….is left in me

no: tongue breaks and thin

fire is racing under skin

and in eyes no sight and drumming

….fills ears

and cold sweat holds me and shaking

grips me all, greener than grass

I am and dead—or almost

….I seem to me.

But all is to be dared, because even a person of poverty …

Buddha and Confucius are not yet born, the idea of democracy and the word philosophy not yet conceived, but Eros—Aphrodite’s servant—already rules with an unyielding hand: as a god, one of the oldest and most powerful, but also as an illness with unclear symptoms that assails you out of the blue, a force of nature that descends on you, a storm that whips up the sea and uproots even oak trees, a wild, uncontrollable beast that suddenly pounces on you, unleashes unbridled pleasure, and causes unspeakable agonies—bittersweet, consuming passion.

There are not many surviving literary works older than the songs of Sappho: the down-to-earth Epic of Gilgamesh, the first ethereal hymns of the Rigveda, the inexhaustible epic poems of Homer and the many-stranded myths of Hesiod, in which it is written that the Muses know everything. “They know all that has been, is, and will be.” Their father is Zeus, their mother Mnemosyne, a titaness, the goddess of memory.

We know nothing. Not much, at any rate. Not even whether Homer really existed, or the identity of that author whom we for the sake of convenience have dubbed “Pseudo-Longinus,” who quotes Sappho’s verses on the power of Eros in the surviving fragments of his work on the sublime, thereby preserving her lines for future generations, namely us.

We know that Sappho came from Lesbos, an island in the eastern Aegean situated so close to the mainland of Asia Minor that, on a clear day, you might think you could swim across—to the coast of the immeasurably rich Lydia of those days, and from there, in what is now Turkey, to that of the immeasurably rich Europe of today.

Somewhere there, in the lost kingdom of the Hittites, must lie the origins of her unusual name, which either means “numinous,” “clean,” or “pure source,” or—if you trace its history back by a different route—is a corruption of the ancient Greek word for sapphire and lapis lazuli.

She is said to have been born in Eresus, or perhaps in Mytilene, in about the year 617 before our calendar began, or possibly thirteen years earlier or five years later. Her father was called Scamander or Scamandronymus, or otherwise possibly Simon, Eumenus, Eerigyius, Ecrytus, Semus, Camon, or Etarchus, according to the Suda, a highly eloquent but not very reliable Byzantine encyclopedia from the tenth century.

We know she had two brothers named Charaxus and Larichus, and perhaps a third named Eurygius, and that she was of noble birth, since her youngest brother, Larichus, was a cupbearer in the Prytaneion in Mytilene, a post reserved only for the sons of aristocratic families.

We believe her mother was called Cleïs and that Sappho had a daughter of the same name, even though the word, which she uses when addressing the beloved girl in a poem, can also mean slave.

Nowhere does Sappho refer to a husband. The name “Kerkylas of Andros Island” mentioned in this connection in the Suda has to be a smutty joke by the Attic comic poets, who undoubtedly took pleasure in ascribing to her, of all women, a husband with a name sometimes rendered as “Dick Allcock from the Isle of Man.” The legend of her unhappy, even self-destructive love for a young ferryman named Phaeon, later embellished by Ovid in his Letters of Heroines, must date from the same time.

We know from an inscribed chronicle dating from the third century before Christ that at some point—when exactly is not recorded on the Parian marble tablet—she fled by ship to Syracuse. We can conclude from another source that it was in around 596 B.C., when Lesbos’s fortunes were in the hands of the Cleanactidai clan.

Seven or eight years later, when the island was under the rule of the tyrant Pittacus, Sappho must have returned from exile and founded a women’s circle in Mytilene, which may have been a cultish community set up to honor Aphrodite, a symposium of fellow females bearing an erotic attachment to one another, or a marriage preparation school for daughters of noble birth: no one knows for sure.

No other woman from early antiquity has been so talked about, and in such conflicting terms. The sources are as sparse as the legends are manifold, and any attempt to distinguish between the two virtually hopeless.

Every age has created its own Sappho. Some even invented a second in order to sidestep the contradictions of the stories: she was variously described as a priestess in the service of Aphrodite or the Muses, a hetaera, a man-crazed woman, a love-crazed virago, a kindly teacher, a gallant lady; by turns shameless and corrupt, or prim and pure.

Her countryman and contemporary Alcaeus described her as “violet-haired, pure, honey-smiling,” Socrates as “beautiful,” Plato as “wise,” Philodemus of Gadara as “the tenth Muse,” Strabo as “a marvelous phenomenon,” and Horace as “masculine,” but there is now no way of knowing what exactly he meant by that.

A papyrus from the late second or early third century for its part claims that Sappho was “ugly, being dark in complexion and of very small stature,” “contemptible,” and “a woman-lover.”

At one time bronze statues of her were common; even today, silver coins still bear her laurel-crowned profile, a water jug from the school of Polygnotos portrays her as a slim figure reading a scroll, and a gleaming black vase from the fifth century before Christ shows her as tall in stature, holding an eight-stringed lyre in her hand as if she had just finished playing or were just about to start. We do not know how Sappho’s verses sounded in Aeolic—the most archaic and tricky of the extinct ancient Greek dialects, in which the initial aspiration was omitted from words—when they were sung at a wedding ceremony, at a banquet, or in the women’s circle, accompanied by a stringed instrument: the hushed sound of a plucked phorminx or the festive ring of the cithara, the deep tones of the barbitos or the harp-like strains of the pectis, the high tones of a magadis or the dull resonance of a tortoiseshell lyre.

All we know is that the word lyric derives from one of these instruments, the lyre, and was coined by Alexandrian scholars some three hundred years after Sappho’s death. It was they who dedicated to her an entire edition in eight or nine books, many thousands of lines on several rolls of papyrus, arranged according to meter, several hundred poems, of which only a single one has come to us intact, because the rhetorician Dionysius of Halicarnassus, who lived in Rome during the reign of Augustus, quotes it in full in his treatise On Literary Composition as an example worthy of admiration. Other than that, four consecutive stanzas were recorded by the scholar known as Pseudo-Longinus; five stanzas of another poem were successfully reassembled from three different papyrus fragments; four stanzas of another were discovered in 1937 carelessly scrawled on a palm-size potsherd by an Egyptian schoolboy in the second century before Christ; fragments of a fifth and a sixth poem were preserved on a tattered early medieval parchment, and large portions of a seventh and eighth were recently discovered on strips of papyrus forming part of the cartonnages used for the preservation of Egyptian mummies or as book covers, although the deciphering of one of the two poems still divides the throng of experts to this day.

A handful of words or isolated lines cited by grammarians like Athenaeus and Apollonius Dyscolus, the philosopher Chrysippus of Soli, or the lexicographer Julius Pollux to illustrate a certain style, a particular item of vocabulary or the meter named after her, were provided by the large-format codices of medieval scribes—the rest is nothing more than scraps: a scattering of stanzas one or two lines long, fragmentary verses, words plucked from their context, single syllables and letters, the beginning or end of a word, or a line, nowhere near a sentence, let alone a meaning.

………

and I go …

…

… immediately …

……

… for …

… of harmony …

… the chorus, …

… clear-sounding

…

… to all …

…

It is as if, in the places where the singing has faded away and the words are missing, where the papyrus scrolls are rotten and torn, dots had appeared, first singly, then in pairs, and soon in the vague pattern of a rhythmic triad—the notation of a silent lament.

These songs have fallen silent, turned to writing, Greek characters borrowed from the Phoenician: dark majuscules, carved into clayey earthenware in a clumsy schoolboy hand or copied onto the pith of the woody wetland grass by a diligent professional using a reed pen; and delicate minuscules, written on the pumice-smoothed, chalk-bleached skins of young sheep and stillborn goats: papyrus and parchment, organic materials that, once exposed to the elements, eventually decompose like any cadaver.

…

… nor …

… desire …

… but all at once …

… blossom …

… desire …

… took delight …

Like forms to be filled in, these mutilated poems demand to be completed—by interpretation and imagination, or by the deciphering of more of the loose papyrus remnants from the garbage dumps of Oxyrhynchus, that sunken town in central Egypt where a meter-thick layer of dry sand preserved these rock-hard, worm-eaten fragments—fragile, creased, and tattered from being rolled and unrolled—for nearly a thousand years.

We know that people wrote on papyrus scrolls in tightly packed columns without spaces between words, punctuation, or guidelines, making even well-preserved items hard to decipher. Divinatio, in the ancient art of the oracle, was the gift of prophesying the future by observing bird migrations and interpreting dreams. Nowadays, in papyrology, it refers to the ability to read a line where all that is visible are faded fragments of ancient Greek letters.

The fragment, we know, is the infinite promise of Romanticism, the enduringly potent ideal of the modern age, and poetry, more than any other literary form, has come to be associated with the pregnant void, the blank space that breeds conjecture. The dots, like phantom limbs, seem intertwined with the words, testify to a lost whole. Intact, Sappho’s poems would be as alien to us as the once gaudily painted classical sculptures.

In total, all the poems and fragments that have reached us, as brief, mutilated, and devoid of context as they are, add up to no more than six hundred lines. It has been calculated that around 7 percent of Sappho’s work has survived.

It has also been calculated that around 7 percent of all women feel attracted solely or predominantly to women, but no calculation will ever be able to establish whether there is any correlation here.

The history of symbols contains a number of markers of the unknown and indeterminate, of the absent and lost, of the void and the blank: the zero on the corn lists of the ancient Babylonians, the letter x in an algebraic equation, the dash used when someone’s words are abruptly interrupted.

… …………………….… ………………….…

goatherd ………….longing ………….sweat

… …………………….… ………………….…

… roses …

…

Aposiopesis—the technique of suddenly breaking off midsentence—we know is a rhetorical device that Pseudo-Longinus, too, will certainly have written about in that part of his treatise On the Sublime that has been lost owing to the carelessness of librarians and bookbinders. If someone stops speaking, starts stuttering and stammering or even falls silent, it suggests he is overcome by feelings of such magnitude that inevitably words fail him. Ellipses open up any text to that vast obscure realm of sentiments that cannot be verbalized or that capitulate in the face of the words available.

… my darling one …

We know that the letters Emily Dickinson wrote to her friend and future sister-in-law Susan Gilbert had a series of passionate passages deleted from them, prior to publication, by her niece Martha, Gilbert’s daughter, who omitted to indicate these deletions. One of these censored sentences, from June 11, 1852, reads: “If you were here—and Oh that you were here, my Susie, we need not talk at all, our eyes would whisper for us, and your hand fast in mine, we would not ask for language.”

Wordless, blind understanding is as much a firm topos of love poetry as is the wordy evocation of unfathomable feeling.

Sappho’s words, where decipherable, are as unambiguous and clear as words possibly can be. At once sober and passionate, they tell, in an extinct language that has to be resurrected with each translation, of a heavenly power that, twenty-six centuries on, has lost none of its might: the sudden transformation, as wondrous as it is merciless, of a person into an object of desire, rendering you defenseless and causing you to leave your parents, spouse, and even children.

Eros the melter of limbs (now again) stirs me—

sweetbitter unmanageable creature who steals in

We know that the categorization of desire according to whether its protagonists were of the same or different genders was a concept foreign to the ancient Greeks. Rather, what mattered to them was that, in sexual relations, the role of each of the persons involved mirrored their social one, with adult men taking an active sexual role, while youths, slaves, and women remained passive. The dividing line in this act of control and submission ran not between the sexes, but between those who penetrate and possess, and those who are penetrated and possessed.

Men are not mentioned by name in the surviving poetry of Sappho, whereas many women are: Abanthis, Agallis, Anagora, Anactoria, Archeanassa, Arignota, Atthis, Cleïs, Cleanthis, Dica, Doricha, Eirana, Euneica, Gongyla, Gorgo, Gyrinna, Megara, Mica, Mnasis, Mnasidica, Pleistodica, Telesippa. It is they whom Sappho sings about, with tender devotion or flaming desire, with burning jealousy or icy contempt.

Someone will remember us

I say

…….even in another time

We think we know that Sappho was a teacher, even though the first source to refer to her as such is a papyrus fragment dating from the second century A.D., which reports, seven hundred years after her death, that she had taught girls from the best families in Ionia and Lydia.

There is nothing in any of Sappho’s surviving poetry to suggest an educational setting, although the fragments contain descriptions of a world in which women come and go, and there is often mention of farewells. The place seems to be one of transition, which led some to interpret it as hosting the female equivalent of the more widely attested Greek practice of pederasty. This reading also conveniently enabled the undeniable presence of female eroticism in poetry to be accounted for as a form of preparation for the main focus, the undisputed culmination of that teaching, namely marriage.

We do not know the exact nature of the relationship between Hannah Wright and Anne Gaskill, whose marriage was recorded without comment in the register of marriages of the parish of Taxal in northern England on September 4, 1707, though we do know that the expression “where you go I will go,” commonly used in Christian marriage ceremonies, is borrowed from the words spoken by the widowed Ruth to her mother-in-law, Naomi, in the Old Testament.

We also know that in 1819, in the court case involving the two headmistresses of a Scottish girls’ boarding school who—a pupil had alleged—had engaged in improper and criminal acts on one another, Lucian’s Dialogues of the Hetaerae was quoted to show that sex between women was actually possible. In it the hetaera Clonarion asks the cithara player Leaina about her sexual experience with “a rich woman from Lesbos” and in particular presses her to reveal what exactly she had done with her and “using what method.” But Leaina counters: “Don’t question me too closely about these things, they’re shameful; so, by Aphrodite, I won’t tell you!”

The chapter ends at this point, the question goes unanswered, and so what women do with one another remains both unuttered and unutterable. At any rate the two teachers were acquitted of the charge, as the judge came to the conclusion that the transgression of which they were accused was not actually possible: where there is no instrument there can be no act, where there is no weapon there can be no crime.

For a long time, what women do with one another could only be regarded as sex and therefore an offense if it mimicked sexual intercourse between a man and a woman. The phallus marked the sexual act, and where it was absent there was nothing but an unmarked blank, a blind spot, a gap, a hole to be filled like the female sexual organ.

For a long time, this empty place was occupied by the concept of the “tribade,” that specter that haunts the writings of men, namely a masculine-acting woman who has sex with other women with the help of a monstrously enlarged clitoris or a phallic aid. As far as we know, no woman has ever described herself as a tribade.

We know that words and symbols change their meaning. For a long time, three dots in a row along the writing baseline designated something lost and unknown, then at some point also something unuttered and unutterable; no longer only something omitted or left out, but also something left open. Hence the three dots became a symbol that invites one to think the allusion to its conclusion, imagine that which is missing, a proxy for the inexpressible and the hushed-up, for the offensive and obscene, for the incriminating and speculative, for a particular version of the omitted: the truth.

We also know that in ancient times the symbol for omissions was the asterisk—the little star that only in medieval times took on the task of linking a place in a text to its associated margin note. As Isidore of Seville writes in the seventh century in his Etymologies: “The asterisk is placed next to omissions, so that things which appear to be missing may be clarified through this mark.” Nowadays the asterisk is sometimes used as a means of including as many people as possible and their sexual identities. The omission becomes an inclusion, the absence a presence, and the empty place a profusion of meaning.

And we know that in ancient times the verb lesbiazein, “to do it like women from Lesbos,” was used to mean “to violate or corrupt somebody” and to refer to the sexual practice of fellatio, which was assumed to have been invented by the women of the island of Lesbos. Even Erasmus of Rotterdam, in his collection of ancient sayings and expressions, renders the Greek word as the Latin fellare, meaning “to suck,” and concludes the entry with the comment: “The term remains, but I think the practice has been eliminated.”

Not long after that, at the end of the sixteenth century, Pierre de Bourdeille, seigneur de Brantôme, comments in his pornographic novel The Lives of the Gallant Ladies: “’Tis said how that Sappho the Lesbian was a very high mistress in this art, and that in after times the Lesbian dames have copied her therein, and continued the practice to the present day.” From then on the empty space had not only a geographical but also a linguistic home, although the term amour lesbien remained in common use until the modern age as a term describing the unrequited love of a woman for a younger man.

We know that the two young poetesses Natalie Clifford Barney and Renée Vivien were disappointed when, in late summer 1904, they fulfilled a long-cherished dream and visited the isle of Lesbos together. When they finally reached the port of Mytilene, French chansons were blaring from a phonograph, and both the visual appearance of the island’s female inhabitants and the crudeness of their idiom were at odds with the poetesses’ noble imaginings of this place so frequently evoked in their own poems. Nevertheless, they rented two neighboring villas in an olive grove, went for long moonlit and sunlit walks, rekindled their love that had grown cold some years earlier, and talked about setting up a school of lesbian poetry and love on the island.

The idyll ended when a third woman—a jealous and possessive baroness with whom Vivien was in a liaison—announced she was on her way, and a telegram had to be sent to stop her. Barney and Vivien separated. Back in Paris, their mutual Ancient Greek teacher served from then on as the bearer of their secret letters.

We know that, in 2008, two female residents and one male resident of the island of Lesbos unsuccessfully attempted to introduce a ban on women not originally from the island naming themselves after it or being named after it by others: “We object to the arbitrary use of the name of our homeland by persons of sexual deviation.” The presiding judge rejected the application and ordered the three Lesbians to bear the court costs.

Who, these days, is still familiar with the “Lesbian rule” alluded to by Aristotle in his Nicomachean Ethics, used in cases where general laws cannot be applied to concrete situations, following the example of the master builders of Lesbos, who used a leaden rule that “can be bent to the shape of the stone,” since it was better, in a concrete situation, to have a crooked but functioning rule than to follow an ideal that was smooth and straight but useless.

And who, these days, is still familiar with the Sapphic stanza, that four-line verse form comprising three hendecasyllabic lines of matching structure, consisting of trochees with a dactyl inserted in third place, and an adonic as the fourth line, in which each line starts directly with a stressed syllable, every line ending is feminine, and the solemn dignity so characteristic of this meter yields at the end to a sense of reassurance or even serenity.

For a long time terms like tribadism, Sapphism, and lesbianism were used more or less synonymously in the treatises of theologians, jurists, and physicians, though in some instances they denoted a perverse sexual practice or shameless custom, and in others a monstrous anomaly or mental illness.

We do not know exactly why the term lesbian love has endured for some time now, only that this expression and its associations will fade in the same way as all its predecessors.

L is an apical consonant, e the vowel expelled most directly, s is a hissing, warning sound, b an explosive sound that blasts the lips apart …

In German dictionaries, lesbisch (“lesbian”) comes immediately after lesbar (“legible”).

—Translated from the German by Jackie Smith

Judith Schalansky was born in Greifswald in former East Germany in 1980 and studied art history and communication design. Her international best seller, Atlas of Remote Islands, won the Stiftung Buchkunst (the Art Book Award) for “the most beautifully designed book of the year,” while her novel The Giraffe’s Neck, in an English translation by Shaun Whiteside, won a special commendation of the Schlegel-Tieck Prize for the best translation from German in 2015. Both books have been translated into more than twenty languages. Schalansky works as a freelance writer and book designer in Berlin, where she is also publisher of a prestigious natural history list at Matthes und Seitz.

Jackie Smith studied German and French at Selwyn College, Cambridge, and then undertook a postgraduate diploma in translation and interpreting at the University of Bradford. In 2015 she was selected for the New Books in German Emerging Translators Programme and in 2017 won the Austrian Cultural Forum London Translation Prize. An Inventory of Losses is her first literary translation.

From An Inventory of Losses , by Judith Schalansky, translated from the German by Jackie Smith. © New Directions.

December 7, 2020

The Art of Distance No. 36

In March, The Paris Review launched The Art of Distance, a newsletter highlighting unlocked archive pieces that resonate with the staff of the magazine, quarantine-appropriate writing on the Daily, resources from our peer organizations, and more. Read Emily Nemens’s introductory letter here, and find the latest unlocked archive selections below.

“As we revealed last week, the Winter 2020 issue of The Paris Review features the theater—an Art of Theater interview with Suzan-Lori Parks and excerpts of three new plays by David Adjmi, Kirk Lynn, and Claudia Rankine. Read more about the genesis of this special issue and the collaboration with guest theater editor Branden Jacobs-Jenkins in my editor’s note. This week, we hope you pick up the new issue (it’s available online now and hitting newsstands Tuesday, December 8), but in the meantime I wanted to share some earlier theatrical content from the Review. Read on for unlocked pieces from issue no. 142, the last installment of the Review with a theatrical focus, but also from another touchstone issue—no. 39, which features conversations with twentieth-century theater titans Edward Albee and Harold Pinter. For another dose of theater, RSVP for our issue launch event on December 16 at 6 P.M. ET. It will feature a live table read from Kirk Lynn’s new play, The First Line of Dante’s ‘Inferno.’ Until then, read well, stay healthy, and have a good week.” —EN

Photo: Albarubescens. CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...), via Wikimedia Commons.

Wendy Wasserstein’s Art of Theater interview includes a conversation about humor in the theater. “Humor masks a lot of anger, and it’s a means of breaking up others’ pretenses and of not being pretentious yourself.”

“A small country shop on the island of Inishmaan circa 1934. Door in right wall. Counter along back, behind which hang shelves of canned goods, mostly peas.” Step into the opening scene of Martin McDonagh’s The Cripple of Inishmaan.

Going back to 1966, Edward Albee’s Art of Theater interview begins with a question about getting panned. “I see you’re starting with the hits,” Albee replies. But even in his less popular endeavors, Albee finds grace. “I retain for all my plays, I suppose, a certain amount of enthusiasm. I don’t feel intimidated by either the unanimously bad press that Malcolm got or the unanimously good press that some of the other plays have received.”

And because what would a week be without some unlocked poetry, here are two theatrical poems: D. Nurkse’s “First Love” describes a performance of Romeo and Juliet, and Frank O’Hara’s “To John Wieners” captures the swirling energy of the theater before curtain.

Sign up here to receive a fresh installment of The Art of Distance in your inbox every Monday .

The Shadows below the Shadows

Nina MacLaughlin’s newest column, Winter Solstice, will run for four weeks, finishing on the solstice on December 21.

Vintage Krampus Postcards

December and Demeter is grieving again.

Hades cracked the earth and snatched her daughter Persephone, tugged her down to the underworld to be his unconsenting bride. In response, Demeter ceased growth. Wilt, starvation, cold. No warmth, no fruit, no fat goats whose throats to slit in sacrifice. So Zeus sent Hermes to the underworld to bring Persephone back. But Ascalaphus, Hades’s orchard minder, saw what Persephone had done, and told, rotten tattler. If you eat the food of the dead, you stay, and Persephone had swallowed six pomegranate seeds. The gardener held the fruit in his hand and the juice slipped down the private part of his wrist. Each seed, one month in Hades. She’s down there now. And we’re up here, buttoning our coats, eating carbohydrates, trying to remember to unclench our jaws.

There’s something seductive about the below, the magnetic tug of the dark. Aren’t you curious? To see how dark it gets, to see what’s down here, a little lower, a little deeper, something might get revealed, something singular, something special, I’m getting close to something true. It’s risky. I have a friend who likes to press a knife blade to his wrist. “It makes me shiver,” he says, “I feel it in all my tips.” I wouldn’t call him crazy. He’s interested in the edge. “The descent to the Underworld is easy,” Virgil cautions in The Aeneid. “Night and day the gates of shadowy Death stand open wide, / but to retrace your steps, to climb back to the upper air— / there the struggle, there the labor lies.” Sinking down is easy. But to return? No guarantees.

In Ireland, thirty miles north of Dublin near the river Boyne, there’s a mound of earth with an opening. You can enter. A tight passageway leads to a deep chamber; a tomb at one time: human bones were found there, and long-gone chiselers carved triskelion, those ancient-art triple spirals, into certain stones. The passageway extends sixty feet, almost the length of two telephone poles, and at sunrise on the winter solstice, a shaft of sunlight enters through a window above the opening you’ve entered through; the beam travels down the passageway and penetrates into the chamber, spraying light into the deep dim basin. The place is called Newgrange and it was built in 3200 B.C. It is older, by hundreds of years, than Stonehenge and the pyramids at Giza.

I entered a long time ago. It wasn’t on the solstice, but they shine a light that mimics the way the sunbeam seeks the chamber on the darkest day of the year. The hush was total, we were all the way within, and the shaft slid past our bodies and lit the deepest part of the tomb, the womb, the undermound, otherworld, and the megalithic spirals revolved across millennia. If you are someone who feels ghosts, or time, or the presence of deep-dead stone movers, peat farmers, priestesses, priests, bog queens, salmon kings, ubiquitous shape-shifters, souls who touched the stones you stand under, souls who tracked the sun and made a mound for it to enter, to join with, to bring the sunlight back to the earth, you might feel them here, as you witness the silent coupling of sun god and earth goddess. Let’s urge sun and earth to mate so that light is born on earth again. They knew the angles, five thousand years ago.

This whole earth spins tilted on its axis at 23.5 degrees. On the winter solstice, the sun at noon is directly over the Tropic of Capricorn, at 23.5 degrees south of the Equator. Capricorn, that stomping, large-horned sea goat. Is there an earthier beast than the goat? They dance on rock faces, their cloven hooves leave ash prints on soft earth, they grunt, hum, holler with the voice of man, and I felt a funny mix of alarm and delight the first time I looked one in the eye and saw its pupils were rectangular. At a farm on a hill in south-central Connecticut, buy a pack of stale wafers for a quarter to feed the three goats penned to the left. I pressed the wafer through the fence, the goat took it on its tongue, and I saw what I had not seen before. Goats with right-angled bands across the globes of their ice- or amber-colored eyes.

In Central Europe, a folklore lives in the figure of Krampus, a stomping satyr-like creature, furred animal from the waist down, furred man-goat from the waist up, with a pointed lashing long tongue and sharp fangs and great goat horns. The smell of woods and soot about him, dead-leaf tang of dark dens, half-intoxicating half-repugnant ungulate musk. I haven’t touched his fur, but maybe it’s not a thick-matted hay-coarse mess, but angel-hair lush, cashmere-y. He emerges this time of year as the dark twin to the twinkle-eyed benevolence of old Saint Nick. His night, Krampusnacht, was this past weekend, on December 5. He carries a birch switch to whip the misbehavers, and the sack or basket slung over his shoulder bears no gifts: it’s to stuff bad children in. He knots the sack and drops them into a river like a squirming litter of unwanted kittens. That, or he eats them.

It’s a way to motivate children to behave, sure. You better watch out, you better not pout, et cetera. Stop tugging your sister’s pigtails or Krampus will take you. Stop chasing the chickens or you’ll get jammed in Kramp’s sack. Be good, be right, behave, or Krampus will whisk you away forever. Motivation, and also, maybe, secret wish? A fantasy? Or perhaps this goat-horned punisher is the creatured embodiment of winter’s danger. It’s not just a chubby chuckling red-suited do-gooder in a flying sleigh who giveth but a furred fanged earthbound mischief-maker who taketh away. Here we are, back to forces of dark and light.

Fleshing the shadows is one way to know the shadows better. When fears get faced and named, aren’t they easier to encounter? When they come creeping, slithering, spidering in, as they always inevitably will, it’s better, no, to see a familiar silhouette, a recognizable cut of the jaw, that same tongue, that same staticky charge, those wild underworldly eyes, you again, we’ve met before. Still unpleasant, still frightening, but at least it slots into a taxonomy of the monstrous. It’s the formless unfamiliar, the shadow that lives below shadow, the one we sense but have not named or cannot yet name, there’s where real terror lives. And so we name our monsters. Perhaps the pull of the dark is the urge to introduce ourselves to the shadows below the shadows. Come in, come in, let me know you better, let me look upon you, I have never seen the like of you before. Maybe they all have something to offer. After all, wouldn’t we all like to live deliciously?

Saturn rules Capricorn, and Saturnalia was the ancient Roman festival honoring him. He was a child-eater himself, a scythe-holding god of the agricultural cycles. The festival took place over seven days around the winter solstice. Feasts, gifts, mischief, the rules gave way, the chains of discipline were lifted. In this kind of boundary-dissolving extendo-fest, “we throw down our burdens of time and reason,” writes Octavio Paz. Time dissolves; roles reverse; people drop into a simultaneous backward and forward. Reason gives way to something more bodily, blood-level, in a “sudden immersion in the formless, in pure being.” Ecstasy, in other words. Kerry Howley writes of “ecstatic spectacle.” History is full of it:

If you were a fourteenth-century Latvian looking to leave yourself, you might mask up and dance through the streets reveling in Rabelaisian wonder … were you a nineteenth-century Paiute Indian in the American West, you might try your hand at ritual millenarian dance … or an ancient maenad, join the other womenfolk in ripping apart a live goat in the Greek countryside.

What opportunity for ecstasy do we have right now? These twin searches: for dissolving the boundaries and exiting time; and for home, grounding, safety, the source. In rare moments we dissolve, formless, passing through the membrane into a shimmering of raw perception, into union with the All. A temporary death—an end to the limits of the self—and an emergence from it in the form of rebirth, a waking up.

And maybe that’s what the ancient farmers were up to in building Newgrange, a way of pulling the sun back from darkness, to wake it up and return it to earth. It’s long ago, and it’s right now. It’s earth and sun, and the wheel of the year spins on, like the triskelion on stones, the evergreen wreaths on doors. Mistletoe, the evergreen white-berried vine, living as it does off the ground in trees, was seen as link between earth and air, a fertility symbol, athrob with life force, its milky jewel berries full of sticky white juice. So come, kiss. Kiss. It might take you somewhere. As Sibyl tells Aeneas before his journey to the underworld: “No one / may pass below the secret places of earth before / he plucks the fruit” of the famous golden bough, “as mistletoe in the dead of winter’s icy forests / leafs with life on a tree that never gave it birth.” It’s his ticket in. It’s his ticket under.

Underworlds, otherworlds, so many passageways on this earth to elsewheres, especially during these weeks of the year. Slip out of the light and know something older. Slip into something elemental. It’s on offer, these weeks more than ever. I liked the way I felt inside the mound of earth at Newgrange. The way I felt there I have only felt there. Not underworld exactly but touched by—turned into—light and darkness, light and time. Not for long. Ten seconds of my life, likely less. I returned to the surface with the others, fat sheep made small clouds against green hills, river had sky on it, I couldn’t speak for a while. What was there to say?

The year is fading. Light is fading. Solstice means sun-stilled. We light candles and raise toasts, we smooch in doorways under strung-up plants, we hang lights along the roofline peaks, give gifts, make wishes, laugh and pray and fear. We bring the light into the earth and try to harness the great forces. It’s a wild sort of stilling, a thrashing frenzied sort of stilling, a stopping of time, a de-metering, a holding of the breath as the tension builds, as the dark expands, until it cracks and light drives in. That’s the hope. The far-off tinkling of bells you hear could be the harness of the reindeer or the bells around the neck of a goat. Hoofbeats on the roof, hoofbeats thudding in the warm and living hollow of your chest. Here in the wild quiet, something in the shadows whispers and you can’t tell if it means you good or ill. Pomegranate, holly branch, birch switch, mistletoe. We’ll leaf with life and pass below the secret places of this earth.

Read Nina MacLaughlin’s series on Summer Solstice, Dawn, Sky Gazing, and November.

Nina MacLaughlin is a writer in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Her most recent book is Summer Solstice.

December 4, 2020

Staff Picks: Mingus, Monologues, and Memes

Hannah Sullivan. Photo: Teresa Walton.

As much as there are perfectly crafted lines of poetry I think about often, there are perfect titles, too, that I find myself thinking about as much as the poems themselves. Recently, variations of the title “You, Very Young in New York,” the first in Hannah Sullivan’s Three Poems, have been at the front of my brain—looking at old photos from old summers, making future plans, bestowing this very young in New York phase of my life with the dynamic cadence of the phrase. Though corporeally I am still in a body that is still in New York, that cadence seems to belong to a past or future self that I sometimes feel I have to go back in search of or somehow move toward. Yet Sullivan’s poem dispels this notion. While it overflows with precise detail and indulges each of the senses spectacularly, the poem makes space for slowness, too. From the first page, the reader is invited to embody the second-person narrator—to hail their cabs, to wait for age to wear down a type of unwelcome innocence. Even then, “the senses, laxly fed, are self-replenishing, / Fresh as the first time, so even the eventual / Sameness has a savour for you,” which is a gorgeous comfort to imagine now. The sumptuousness of the poem, then—the vivid colors and tastes of huckleberry jam or overripe peaches “sitting with their bruises”—happens not despite the quiet moments but inside them. The second poem, “Repeat until Time,” lets the days stretch out even more. There, “days may be where we live, but mornings are eternity. / They wake us, and every day waking is an absurdity.” I’m learning from Sullivan how to thank the sameness for its savour, to wake to the absurdity as well as the sun. “‘You will know when it’s time, when the fair is over,’” says the opening stanza of the collection, and by the time the poem ends, it still isn’t over, but “through tears, you are laughing.” —Langa Chinyoka

Audacious is the word that kept coming to mind as I read Katharina Volckmer’s debut novel, The Appointment. Audacious, along with hilarious and unsettling—but unsettling in the best kind of way. The Appointment is a book about shame, of both the national and psychosexual varieties, and takes the form of a monologue from a young German woman in London to her Jewish doctor. Volckmer is quick to deflate contemporary Germany’s image of itself as a country that has dealt with its past, and she’s prone to lines that are as provocative as they are funny (“It’s possible that he also thought I was Austrian; Germans don’t usually bother with basements—they are happy to torture people on the first floor, they’re not that discreet”). This is a smart, unruly novel, one that dares to ask unexpected questions about the meaning of nation, gender, sexuality, and history. —Rhian Sasseen

100 gecs. Photo courtesy of Big Beat Records.

The first installment of Bijan Stephen’s column for The Believer concerns a year spent immersed in the worlds of video games: “Embodiment in games acts as a surrogate for travel: I go somewhere else, somewhere that doesn’t necessarily intersect with the physical plane we inhabit.” In the early months of the pandemic, I often relied on music—specifically, the act of obsessive listening—to achieve a similar effect. I would lock myself inside musical fugue states, the anxious minutes melting into hours of Neil Young, mornings marked by nothing more than the same three Charli XCX songs, and whole afternoons ticked away in the comfortable quiet of Brian Eno’s Ambient 1: Music for Airports. But more than anything else, I listened to 100 gecs, a duo perhaps best defined by their defiance of easy categorization. They make music that sounds like Crazy Frog executing a flawless breakdance routine within the confines of the Large Hadron Collider. On their 2019 debut album, 1000 gecs, 100 gecs split the atom of the past twenty years of popular music, leapfrogging from metalcore to dubstep, pop punk to hyperpop, ska to trap and back again. I may not have left my apartment much this year, but each dizzying trip through 1000 gecs jolted me out of my quarantine-induced stupor, leading me out of the physical world and into an imaginary space of ever-shifting dimensions and non-Euclidean geometry—towering walls of 808s, trees filled with digitized chirps, and everywhere the heavy gauze of autotune like a summer rain. Listening to 100 gecs can feel like literally surfing the endless expanse of the internet, gliding across the surfaces of depths both knowable and not, stumbling upon motifs and memes entirely divorced from context but constituting a landscape in and of themselves. In a stale, dark year, I find their omnivorousness—their appetite for adventure, their commitment to cultivating and then thriving within a galaxy of one’s own, as we all happen to be doing at this very moment—absolutely inspiring. —Brian Ransom

Because I’m simply obsessed with their work, I have to talk about the orchestral album that Supergiant Games has released in celebration of their ten-year anniversary. As you might have guessed thanks to my incessant praise for Supergiant, I have not stopped listening to their in-house composer Darren Korb’s divine work since the studio posted the entire album to YouTube—as they kindly do with all their music. Taking center stage are the mythical bardic ballads of Pyre and the “old-world electronic post-rock” of Transistor, which pair unexpectedly well despite their disparate genres. It’s no mystery that this is not just because of Korb’s brilliance as a musician but also Ashley Barrett’s inimitable voice work and Austin Wintory’s inspired conducting. To top it all off, the album was recorded at Abbey Road Studios. If you’re still uncertain about the legitimacy of music made for video games, please give a listen to “Paper Boats” or “The Vagrant Song”; there’s a quality of belonging to a different world that these songs not only magnify but celebrate in a way that is utterly unique. —Carlos Zayas-Pons

Charles Mingus was one of jazz’s most distinctive composers, writing musical odysseys in carefully plotted forms that leave plenty of space for dense collective improvisation. Charles Mingus @ Bremen 1964 & 1975, a new four-CD set (if you still go in for that sort of thing—you know, a thing), allows for the delicious and speculative pleasure of charting the course of a major artist’s development; it combines two live recordings made by Germany’s Radio Bremen a decade apart. The first is from 1964, at the apex of Mingus’s golden period; the other is from 1975, when his late music was at its fullest flowering. The 1964 band was one of Mingus’s best, featuring Eric Dolphy, Jaki Byard, and Johnny Coles, among others. Like Frank Zappa, my vote for his closest musical cousin, Mingus’s real instrument was not the bass but the band. His 1964 group races through what would become Mingus’s best-known music—including “Fables of Faubus” and “Parkeriana”—with all the abandon it demands. By the time of the 1975 concert, Mingus had largely left that wonderful controlled chaos behind in favor of the more polished, choreographed, and grandiose master class on jazz history that is his late music (as well as a reprise of “Faubus”). This is also, perhaps, some of Mingus’s most nakedly emotional and confessional music, if one wants to hear it that way. There’s a lot of live Mingus out there, but I’d wager no fan will regret adding this set to their shelf. —Craig Morgan Teicher

Charles Mingus, 1976. Photo: Tom Marcello Webster. CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...), via Wikimedia Commons.

Cooking with James Baldwin

Please join Valerie Stivers and Hank Zona for a virtual wine tasting on Friday, December 18, at 6 P.M. on The Paris Review’s Instagram account. For more details, visit our events page, or scroll down to the bottom of the article.

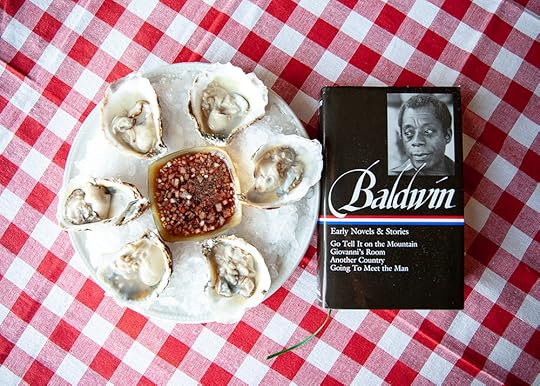

Baldwin’s characters haunted French bistros, where oysters with mignonette are a staple. Photo: Erica MacLean.

“Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.” So read the inspirational quote in the front window of my Brooklyn gourmet market the day I shopped for a meal celebrating the work and life of James Baldwin (1924–1987). These words, coincidentally but not surprisingly, are from Baldwin, who is the man of the moment again thanks to the extraordinary relevance of his writing to today’s America.

Baldwin as a novelist is perhaps best known for Giovanni’s Room and Another Country, the former a gay man’s self-reckoning and the latter a brutal and tragic wrestling with being Black in America. He is known to a lesser extent for having lived most of his adult life abroad, first in Paris and then in the Provençal town of Saint-Paul-de-Vence, though he always kept up his connection to the Harlem of his birth and was an active participant in the U.S. civil rights movement. Intense and multitalented, Baldwin was also a playwright—he loved actors and the theater—and a critic and essayist. His nonfiction collections Notes of a Native Son and The Fire Next Time have predicted the future to an astonishing degree.

My homemade baguette was imperfectly shaped and slashed, but it tasted nearly right. Photo: Erica MacLean.

One of the great Black intellectuals of his era, Baldwin posited race as the central conflict in American life—and identified the “innocence” of race as the white man’s central crime. “I can conceive of no Negro native to this country who has not, by the age of puberty, been irreparably scarred by the conditions of his life,” he writes in Notes of a Native Son. He believed that America taught Black people “with brutal clarity, and in as many ways as possible, that you were a worthless human being. You were not expected to aspire to excellence: you were expected to make peace with mediocrity.” This schooling made it impossible to love self or family, made it impossible to live as a Black person in America—Rufus, the main character of Another Country, dies by suicide. In later years, Baldwin claimed that the nation’s fundamental qualities had remained unchanged despite integration and civil rights. “Europe has not yet left Africa, and black men here are not yet free,” he writes in The Fire Next Time. These facts contain “the gravest implications for us all” because “the Negroes of this country may never be able to rise to power, but they are very well placed indeed to precipitate chaos and ring down the curtain on the American dream.”

The 2016 documentary I Am Not Your Negro juxtaposes Baldwin’s words and speeches with images of contemporary protest against police violence in places like Ferguson, Missouri, to great effect.

A character in Another Country cooks a plate of pork and rice with salad during a domestic dispute. This version is from the culinary icon Edna Lewis. Photo: Erica MacLean.

The root of the racism that defines life in America, Baldwin felt, is fear. White people, Baldwin says in The Fire Next Time, “had robbed black people of their liberty and … profited by this theft every hour that they lived.” The white man despises the Black man because doing so provides him with a feeling of superiority and he cannot face his crimes against the Black man. “A vast amount of the energy that goes into what we call the Negro problem is produced by the white man’s profound desire not to be judged by those who are not white,” Baldwin writes. Elsewhere, he says: “The crime of which I accuse my country and my countrymen, and for which neither I nor time nor history will ever forgive them, [is] that they have destroyed and are destroying hundreds of thousands of lives and do not know it and do not want to know it.”

Baldwin’s thought seems an obvious progenitor to the core ideas of contemporary racial-justice movements. I find it edifying—and a fact to which close attention should be paid—that the influence of Baldwin’s thought has lasted and grown, as a peer to, or perhaps even overtaking, the ongoing generative power of the legacies of other great figures who were his contemporaries. I Am Not Your Negro takes as its starting point an unfinished Baldwin essay on three Black leaders of his time, all of whom were assassinated—Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, and Medgar Evers—and all of whose deaths affected Baldwin profoundly. Each embraced a slightly different form of activism. Baldwin’s was through his art—and his artistic mission, as he conceived it, was to wrestle honestly, visibly, and unflinchingly with everything he saw as true in himself and in the world around him. As Baldwin’s biographer David Leeming writes, “He was born to translate the painful human experience into art.” Baldwin wrote about the church, about his homosexuality, and about race without regard for the sensitivities of anyone and despite the great difficulty and personal pain inherent in doing so. This truth telling has held tremendous power over the decades since his death.

Lewis’s technique calls for the butter and water to be heated together before incorporation with the stuffing. Photo: Erica MacLean.

I would love to know Baldwin’s thoughts on today’s issues. He was insistent that as a matter of self-preservation, Black people must neither hate white people nor give up on them (despite the manifest temptations of doing so), but very often he had white liberals in his crosshairs, memorably accusing them once of “incredible, abysmal, and really cowardly obtuseness.” If nothing else has changed, that probably hasn’t either. The Baldwin quotation at my gourmet market, for example—“Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced”—felt to me more ironic than perhaps the people choosing it had intended, since the shoppers at this particular store are predominantly white and the cashiers are predominantly Black. I was there for oysters and imported French butter and Roquefort cheese—to celebrate James Baldwin, no less—yet I doubt my awareness of race while I made my purchase changes anything. In the more sinister sense, the market’s association of itself with Baldwin probably serves to entrench the status quo.

It’s discouraging, and it can be difficult to feel much optimism for the solutions currently on offer for the ongoing problem of racism in America. Today’s objectives seem to be mostly the same ones we’ve already been attempting, just more so. Yet if Baldwin is to be believed that nothing has changed—and I do believe him—these methods already haven’t worked for half a century. It’s possible that we just haven’t tried hard enough, but it’s also possible we aren’t trying the right things. In reading Baldwin, then, I tried to learn something new by mimicking his openness as a writer with my openness as a reader. I attempted to read with the same tolerance for difficulty and complexity with which he wrote, and to encounter surprises, to find not what I expected but what I didn’t. In the end what struck me most was the power of his contention that “the price of the liberation of the white people is the liberation of the blacks—the total liberation, in the cities, in the towns, before the law, and in the mind.” I imagined all the ways the world might look if we gave up American whiteness and American Blackness both—they are linked, after all; they live and die together—and found in this exercise an arena for ongoing meditation.

The apple-herb stuffing for Edna Lewis’s crown roast of pork uses a lot of butter, but it’s so worth it. Photo: Erica MacLean.

It’s much easier to cook dinner than to provide answers, even when the dinner is an elaborate feast befitting one of our greatest writers. And while the people in Baldwin’s books are usually short on money or appetite—moral nausea has that effect—the writer found food important in a variety of ways. He risked his life on many occasions to protest segregated dining. In his bohemian youth, he was often hungry. Later, he famously became a bon vivant. Describing Baldwin’s great love, Lucien, Leeming says, “They both loved laughter, food, sex, and, above all, drink.” This might seem trivial, but it was a central part of Baldwin’s philosophy: he thought that our fear of sensuality was a fear of ourselves and that without loving ourselves, we would not be able to love others. In one oft-quoted passage of The Fire Next Time, Baldwin writes of this American fear and the importance of overcoming it in our liberation:

To be sensual, I think, is to respect and rejoice in the force of life, of life itself, and to be present in all that one does, from the effort of loving to the breaking of bread. It will be a great day for America, incidentally, when we begin to eat bread again, instead of the blasphemous and tasteless foam rubber that we have substituted for it. And I am not being frivolous now, either. Something very sinister happens to the people of a country when they begin to distrust their own reactions as deeply as they do here, and becomes as joyless as they have become.

Thus emboldened, I started out with the mission of re-creating a meal from the culminating pages of Another Country, when the Black heroine, Ida, is making a dinner of rice and “tomatoes and lettuce and a package of pork chops” for her white lover, Vivaldo, while they say terrible things to each other. The scene is full of precise cooking instructions, like the way Ida “walked to the table and opened the meat. She began to dust it with salt and pepper and paprika, and chopped garlic into it, near the bone.” But Vivaldo and Ida eventually abandon the dish—“Come away from the stove, I can’t eat now,” Vivaldo says—and I thought its simplicity was not in the spirit of Baldwin’s sensuality. To truly channel him, I had to go at least partially French. For that, I had a scene from Giovanni’s Room in which the self-denying gay hero, David, first and doomfully falls in love. David’s Paris is Baldwin’s Paris, and I imagine it being a scene from Baldwin’s life when the two men go to a working-class bar in Les Halles to consume “white wine and oysters,” which Giovanni says “is really the best thing after such a night.” Eating them, “Giovanni sat in the sun, his black hair gathering to itself the yellow glow of the wine and the many dull colors of the oyster where the sun struck it.”

Photo: Erica MacLean.

My efforts to combine these elements achieved a really exciting serendipity. I served a plate of oysters on a restaurant-style bed of crushed ice with a homemade mignonette, paired with a Where’s Linus? Sauvignon Blanc made by the Black American winemaker Chris Christensen. My spirits collaborator, Hank Zona, suggested this wine as a dry, crisp, citrusy option that “goes nicely with fresh shellfish” and is “like the squeeze of lemon on the raw oyster.” Where’s Linus? is a collaboration between Christensen and the boutique distributor Jenny & François Selections; it’s more widely available than Christensen’s own, also highly recommended, line of Bodkin Wines.

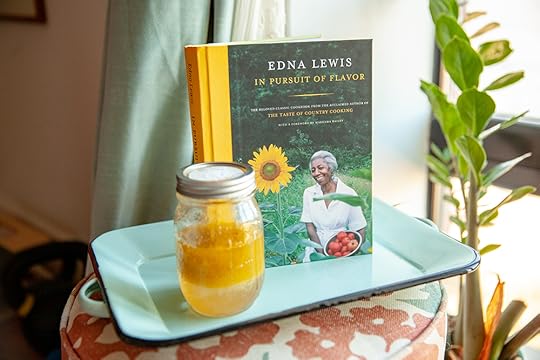

I next made baguettes from scratch, following the injunction from The Fire Next Time to eat better bread, and served them with Roquefort cheese mashed together with fancy French butter, as Baldwin believed was proper. I riffed on the pork chops, rice, and salad by making them from the pages of Edna Lewis, an icon of the kind of Black Southern cooking that influenced the Harlem of Baldwin’s youth. My salad follows Lewis’s loving descriptions of how to mix different greens and how to make a dressing, including shaking it up in a pint Mason jar. My rice is her red rice, the secret ingredient of which is the rice itself—either Carolina or “popcorn” variety. Once baked, this mild, creamy, small-grain variant makes jewellike little clumps, and the balance of pepper, smoke, and sweetness is exquisite. Lastly, I’d read a Saveur magazine article by a woman who’d dined with Baldwin at a restaurant owned by a friend of his in the South of France—the kind of long, legendary afternoon meal the writer was known for. For dessert they’d eaten fresh pineapple, and Lewis happens to have a recipe for a spectacular, show-stopping crown roast of pork garnished with pineapple and stuffed with a glazed-apple-and-herb bread mixture. This is far from the simple chop that Ida made, but its unabashed gustatory wow factor seemed right. Zona paired it with a Maison Noir OPP Pinot Noir, from the Oregon winemaking operations of Andre Mack, a Black restaurateur and vintner based in Brooklyn. The OPP Pinot Noir is less ripe and fruity than the California styles of the same grape, but it still has “plenty of that cherry fruit flavor that goes well with pork,” Zona said, along with notes of herb and spice to match my stuffing.

This crisp, lemony sauvignon blanc from the Black American winemaker Chris Christensen is the ideal pairing for oysters. Photo: Erica MacLean.

The Frenchness and the Black Americana fit perfectly together. Lewis is more Alice Waters than country cook, and every one of her recipes I’ve tried has been revelatory. Even my baguettes, which were denser and chewier than I think proper, were fresh homemade bread, which is never bad. The crown roast of pork was not difficult in terms of technique and seems like something everyone should be doing for a holiday table. I’d make any one of these dishes again, and I highly recommend them as an entire spread, complete with the wines.

To speak of our holiday tables: that we all ought to sit down together and eat—that we can do better—was something Baldwin believed, though fitfully and with difficulty. I can only hope he’ll be right about that, too, as he has been about so many things. In the meantime, at least we have his books to learn from.

Photo: Erica MacLean.

French Bread with Roquefort Cheese and Butter

Adapted from a King Arthur Baking Company recipe.

For the starter:

1/2 cup cool water

1/16 tsp yeast

1 cup flour

For the dough:

all of the starter

1 1/2 tsp yeast

1 cup and 2 tbs lukewarm water

3 1/2 cups flour

1 1/4 tsp salt

Photo: Erica MacLean.

Note that this recipe takes twenty hours and needs to be started the night before.

To make the starter, mix everything together to create a soft dough. Cover and let rest at room temperature for about fourteen hours; overnight works well. By then, the starter should have expanded and become bubbly.

To make the dough, mix and knead everything together—by hand, mixer, or bread machine set on the dough cycle—to make a soft, somewhat smooth dough. It should be cohesive, but the surface may still be a bit rough. If you’re using a stand mixer, knead for about four minutes on medium-low speed (speed 2 on a KitchenAid). The finished dough should stick a bit at the bottom of the bowl.

Place the dough in a lightly greased medium-size bowl, cover the bowl, and let the dough rest and rise for forty-five minutes. Gently deflate the dough, and fold its edges into the center, then turn it over in the bowl before letting it rise for an additional forty-five minutes, until it’s noticeably puffy.

Turn the dough out onto a lightly greased work surface. Gently deflate the dough, and divide it into three equal pieces.

Round each piece of dough into a rough ball by pulling the edges into the center. Cover with greased plastic wrap, and let rest for at least fifteen minutes (or for up to an hour, if that works better with your schedule).

Working with one piece at a time, flatten the dough slightly, then fold it nearly (but not quite) in half, sealing the edges with the heel of your hand. Turn the dough around, and repeat: fold, then flatten. Repeat this whole process again; the dough should have started to elongate itself.

With the seam side down, cup your fingers, and gently roll the dough into a log. The recommended length is sixteen inches. However, that made a baguette that was too long to fit on my cookie sheet. Measure your baking surface before you embark, and adjust accordingly. Taper each end of the log slightly to create the baguette’s typical pointy end.

Place the logs, seam side down, into the folds of a heavily floured cotton dish towel or onto a lightly greased or parchment-lined sheet pan. Cover them with lightly greased plastic wrap, and allow the loaves to rise until they’re slightly puffy. The loaves should look lighter and less dense than when you first shaped them, but they won’t be anywhere near doubled in bulk. This should take about forty-five minutes to an hour at room temperature.

Toward the end of the rising time, preheat your oven to 450 with a cast-iron pan on the floor of the oven or on the lowest rack. Start to heat three cups of water to boiling.

If your baguettes have risen in a dish towel, gently roll them, seam side down, onto a lightly greased or parchment-lined baking sheet. Using a bread lame or a very sharp knife held at about a forty-five-degree angle, make three to five long lengthwise slashes in each baguette.

Load the baguettes into the oven. Carefully pour the boiling water into the cast-iron pan, and quickly shut the oven door. The billowing steam created by the boiling water will help the baguettes rise and give them a lovely, shiny crust.

Bake the baguettes for twenty-four to twenty-eight minutes, or until they’re a very deep golden brown. Remove them from the oven, and let them to cool on a rack. Or, for the crispiest baguettes, turn off the oven, crack it open about two inches, and allow the baguettes to cool completely in the oven, until both the baguettes and the oven are at room temperature.

Serve with Roquefort cheese at room temperature, mashed together chunkily with about two tablespoons of high-quality butter, also at room temperature.

Photo: Erica MacLean.

Oysters with Mignonette

For the mignonette:

4 tbs red wine vinegar

1 tbs shallot, finely minced

1/4 tsp freshly ground black pepper

For the oysters:

12 oysters

about 4 cups crushed ice

lemon wedges (for garnish)

Photo: Erica MacLean.

To make the mignonette, combine all the ingredients in a small decorative dish, and stir.

To serve the oysters, prepare a plate of crushed ice, and place it in the freezer. Open the oysters using your method of choice, making sure to reserve as much liquid as possible in the shell. Place each opened oyster on the ice in the freezer as you go along. Serve immediately with the dish of mignonette and lemon wedges for garnish.

Photo: Erica MacLean.

Edna Lewis’s Red Rice

From In Pursuit of Flavor, by Edna Lewis.

5 or 6 slices of good-flavored bacon, cut into half-inch pieces

2/3 cup chopped onions

1 tsp dried thyme leaves

a green pepper, seeded and chopped

2 small round hot peppers, seeded and chopped

2 cups fresh tomato puree

1 tbs brown sugar

2 cups cold water

2 cups Carolina or popcorn rice

1 cup or more small pieces of cooked ham or fish

salt

freshly ground black pepper

Photo: Erica MacLean.

Cook the bacon in a heavy-bottomed saucepan until crisp. Remove the bacon pieces from the pan, and set aside. Pour off half the bacon fat, and heat the remaining fat over medium-high heat. Add the onions, stir, and simmer for a few minutes. Stir in the thyme, and then add the green and hot peppers. Mix well, and add the tomato puree and brown sugar. Add the water, and stir in the rice.

Preheat the oven to 350.

Cover the pan, and let the mixture simmer on a low burner for about fifteen minutes, until the rice begins to cook. Add the bacon pieces and the ham or fish. Season with salt and pepper to taste. Stir well, and spoon the mixture into a casserole or rice steamer. Cover tightly, and bake in the oven for forty-five minutes to an hour, until the rice is tender. Keep warm until ready to serve.

Photo: Erica MacLean.

Crown Roast of Pork with Herb Dressing, Garnished with Pineapple

From In Pursuit of Flavor, by Edna Lewis.

For the glazed apples:

2 tbs butter

3 medium-size green apples, cored and quartered

1/3 cup light brown sugar

1/4 tsp salt

1/2 tsp freshly grated nutmeg

For the herb dressing:

7 cups diced white bread cubes, a day or two old

1 cup finely chopped onions

1 1/2 cups chopped celery

1/3 cup chopped celery leaves

1 tsp salt (or more to taste)

1 tsp freshly ground black pepper

2 tsp crumbled dried sage leaves

1 tsp dried thyme leaves

1 tbs Bell’s Seasoning

1 1/2 cups cold water

2/3 cup butter

For the crown roast:

a 6 to 8 lb crown roast of pork

2 garlic cloves, peeled and cut into slivers

ground ginger

salt

freshly ground black pepper

For the pineapple garnish:

a fresh pineapple

a small one-inch round cookie cutter (or equivalent) to core the pineapple

4 tsp butter

1 tbs brown sugar

Photo: Erica MacLean.

Preheat the oven to 350. Be sure to adjust the oven racks so the roast has ample headroom.

To glaze the apples, heat the butter in a skillet until it foams. Add the apple quarters, brown sugar, salt, and nutmeg. Cook over moderate heat, stirring occasionally, until the apples are tender and well glazed. Set aside.

To make the herb dressing, put the bread crumbs, onions, celery, and celery leaves in a large bowl, and toss. Add the salt, pepper, sage, thyme, and Bell’s Seasoning, and mix with your hands. (Lewis specifically recommends using dried herbs instead of fresh here for the slightly different flavor they impart.) Heat the water in a small saucepan; when it is hot, add the butter, and let it dissolve. Pour this over the crumb mixture, and mix well with your hands or a wooden spoon. Gently stir in the apples. Cover the dressing until you’re ready to fill the crown roast.

To prepare the roast, make slits in the meat with the point of a sharp knife and insert the garlic slivers. (Being fairly aggressive with the knife makes this easier.) Liberally cover the roast on the inside, bottom, and all sides with ginger, salt, and pepper. Spoon the dressing into the center of the roast, pushing it down with your hands as best you can. (I had a fair amount of extra dressing; how much you need will depend on the amount of room inside your roast.) Place a sheet of tinfoil in the roasting pan, set the roast on top of it, and shape the foil up around the bottom of the roast.

Place in the oven, and bake for two and a half to three hours, until the meat is tender and completely cooked. You may have to cover the bones of the roast and the filling with foil during roasting to prevent drying. Test the roast for doneness with a meat thermometer or by inserting a cake tester or small skewer into the meat, piercing the inside of the roast through the dressing. If the tester goes into the meat easily, it is done.

To prepare the garnish, cut the spiny rind from the pineapple with a large knife. Slice the pineapple into six slices, each about half an inch thick. Use a small cookie cutter to cut out the core in a neat circle. Melt the butter in a wide, heavy skillet until foaming, and sauté the slices for a few seconds on each side. Sprinkle the pineapple with brown sugar, flip, and continue to fry until browned.

When the roast is done, lift it from the pan and, being careful to prevent the stuffing from falling out, slide the roast off the foil and onto a large serving plate. Garnish with the pineapple slices. Serve the roast by cutting between the ribs to cut off whole loin chops.

Photo: Erica MacLean.

Edna Lewis’s Green Salad

From In Pursuit of Flavor, by Edna Lewis.

For the dressing:

1/2 cup cider vinegar

1 1/2 tsp salt

1/2 tsp freshly ground black pepper

1/2 tsp sugar

1/2 tsp dry mustard

1 tsp scraped onion

1 clove garlic, peeled and cut in half

2/3 cup olive oil

For the salad:

1 good-quality tomato, cut into wedges

4 cups any mixture of high-quality greens (Lewis recommends combining different greens, “some bitter, some sweet,” and particularly likes “arugula, Bibb and Boston lettuces, early romaine, black-seeded Simpson, purslane and cress”)

Photo: Erica MacLean.

To make the dressing, put all the ingredients together in a pint jar with a lid, and shake until the salt is dissolved. Remove the garlic. Shake again just before dressing the salad.

To serve the salad, toss all the greens together with the tomato and dressing to taste. Serve at the end of the meal, “after the main course but before dessert,” Lewis says. “I like to put a good goat cheese and bread on the table, too, and perhaps open another bottle of wine.”

Photo: Erica MacLean.

Wine!

Please join Valerie Stivers and Hank Zona on Friday, December 18, at 6 P.M. for a virtual literary wine tasting on The Paris Review’s Instagram account. We will be discussing food in the work of James Baldwin, the culinary legacy of Edna Lewis, and recommended wines from Black-owned wineries such as Maison Noir.

The wines seen in the story are the Where’s Linus? Sauvignon Blanc from Jenny & François Selections and the Maison Noir OPP Pinot Noir, which is widely available in stores and on wine.com and drizly.com.

Anyone who would like more specific advice on how to find these wines near them can email us (hank@thegrapesunwrapped.com).

Valerie Stivers is a writer based in New York. Read earlier installments of Eat Your Words .

December 3, 2020

Authentic Gaddis

I once visited the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia with someone who was convinced that the entire place was filled with fake art: not forgeries or wrongly attributed masterpieces, but “museum quality” reproductions. The basis for this wild claim was a painting from Cézanne’s series The Card Players, of which there are two very similar versions, one in the Barnes, and the other in the Met. Not only was she sure she had seen this painting before, she was certain that at that very moment, the real version was hanging in its rightful place in New York, which meant that the Philadelphia version had to be a fake. The history and layout of the Barnes allowed this theory to quickly gather steam: one of the largest collections of Modernist and Impressionist art in America, it was originally housed in the billionaire philanthropist Albert C. Barnes’s mansion in Pennsylvania and arranged according to esoteric principles that came to be known as the Barnes Method. Rather than having all the Cézannes in one wing, you might see, for example, a peasant woman by Cézanne, with a girl in a pink bonnet by Renoir hanging above it, and a medieval door latch between them. The idea is to observe closely and forge your own metaphoric connections between object and image. But there were too many vaguely familiar Picassos, too many Van Goghs stuffed between rusty sconces, too many corners jammed with Restoration armoires. It was just the sort of thing, my companion said, that an American industrialist who made his fortune selling antiseptic creams would do: build a mansion in the middle of nowhere and fill it with copies of his favorite European things. (This dovetailed nicely with her initial impression that Philadelphia itself was a lesser copy of New York.) Apart from feeling momentarily insane, and at the same time realizing I would probably end up marrying this woman, it occurred to me that it’s not such a bonkers idea when you consider the Met Cloisters, the mishmash of actual convent buildings from Catalonia and southern France that were reassembled in Upper Manhattan by John D. Rockefeller Jr. and filled with an array of Old European Things like sarcophagi, tapestries, and illuminated manuscripts. In any case, it’s a theory that would likely have interested William Gaddis, whose novel The Recognitions, reissued in November by NYRB Classics, is full to bursting with forgers, fakes, thieves, and liars, all in search of an authentic experience of art and life.