The Paris Review's Blog, page 139

November 9, 2020

The Brilliance of Ann Quin

Ann Quin. Photo: Oswald Jones. From the Larry Goodell Collection. Courtesy of And Other Stories.

Three is the second of the four brilliant and enigma-ridden novels that Ann Quin published before drowning off the coast of Brighton in 1973 at the age of thirty-seven. The mysterious character S—the absent protagonist or antiheroine hypotenuse of this love-triangle tale—dies in similar fashion … or perhaps she’s stabbed to death by a gang of nameless, faceless men before her body washes up onshore … or perhaps the stabbed dead body that washes up onshore is someone else… It’s difficult to tell. And the telling is difficult, too. And I would submit that it’s precisely these difficulties that make this gory story normal.

A British married couple, a dyad of faux-boho normies, provide the other two points of Three’s ménage. Their names are Ruth (sometimes Ruthey, sometimes just R) and Leonard (sometimes Leon, sometimes just L). They take up with this young woman referred to only as S, who comes to share their summer-vacation cottage and their lives, her family role ever-shifting from boarder-daughter to sister to lover.

The novel opens with the couple talking over the news of her recent death, in a conversation that flows unimpeded into the one-sided conversation of surveillance. S’s most salient remains are her journals and sundry recordings, both audio and film, which document her relationships with and impressions of R and L, who greedily read and listen to and binge-watch these artifacts in the dark and dreary mourning season that follows. In addition to these artifacts, whose contents seem constantly to rise toward narrative or plot, and then, like the tide, recede, R and L pore over their own diaries and compare their scribbled confessions with S’s: S had an abortion; R and L are trying, or claim they’re trying, to get pregnant. S had, or might have had, a drug habit; R and L prefer to lose themselves in drink, and so on. As this posthumous surveillance of S continues, R and L are themselves surveilled by stranger-neighbors, who are constantly poking their blossomed noses up against the glass.

Besides the fixed-state documents and recordings, the only constant in this world—in this over-upholstered world of inherited bric-a-brac, cats, goldfish, and tepid, tasteless suppers—seems to be confinement itself and the lack of privacy it inculcates. All else continues to change in rapid currents: the news, the anxieties, the social codes…

*

Because Three is such a frank and personal book, I will speak frankly and personally myself: like Ann Quin, and like her characters, I, too, have had problems with monogamy and realism—those two fantasies, those twinned delusions, of How to Live and Reproduce Life (monogamy) and How to Represent Life and Reproduce Its Representations (realism).

In Three, Quin tries to find solutions for these problems, or at least tries to dramatize the search for solutions, and it’s notable that she goes about doing so in opposite ways. Through S, she expands her couple into a throuple, but does so in prose that insistently contracts, in a vicious condensation of third-person description, internal monologue, and “interior”—house-bound—dialogue, none of which is isolated by conventional typography or punctuation. Instead of Victorian quotation marks or even Bloomsburyian dashes indicating speech, instead of paragraphs indicating shifts in point of view, here we have a jumble, all the modalities of the novel form set side by side like a hoarder’s secondhand sitting-room furniture. R’s speech, L’s speech, R’s writing, L’s writing, S’s firsthand documentation, Quin’s own sham-omniscient accounts all run into one another, verbiage bumping up against verbiage in a dim, narrow, junk-cluttered hall:

In the doorway he looked up, holding slippers and a book. What did you say? Boots—did you take them off before going in there? Yes yes. Still raining? Stopped. He went back into the room. She followed, picked up the cat placed his paws on her shoulders. How are your orchids? Not bad quite good really several almost seem to grow overnight but God knows what will happen to them while I’m away the boy’s so hopeless. Well I warned you didn’t I always the same you will take things on then regret the responsibility. That’s hardly the point Ruth anyway I’ve been thinking we could really spend more time down here than we do. I don’t mind the summer Leon but not the winter. Oh I don’t know can be quite cosy with all the fires going and you’re always saying how fed up you get with the parties and people in town. Yes I know but there are advantages I mean I have to see the specialist also I’ve been thinking of having an analyst. Oh not again Ruth we’ve tried all that and you know how bloody neurotic you get. But there’s a good one really quite near too anyway we’ll see.

The effect of this experiment, much like the effect of the open-relationship experiment, is to heighten the multiple claustral experiences on offer: the claustrophobia of monogamy, the claustrophobia of a cottage vacation; the stifling atmosphere of middle-class British domesticity that hasn’t yet gotten into the swing of the sixties; the stifling atmosphere of “the swinging sixties” itself, with its simultaneously entertained feelings of having gone too far and of not having gone far enough; the literal hothouse where L grows his orchids; the cramped kitchens and bathrooms and beds where R spends so much of her existence cooking, cleaning, grooming, and sleeping or trying to sleep, essentially nurturing herself or a figment of happy, successful coupledom in lieu of being able to nurture a happy, successful birth-child.

Quin’s “reproduction” of her characters’ artifacts represents perhaps her most daring attempt to break out of the straitening of both monogamy and realism. While the journal entries are presented in a fairly traditional manner—even poignantly traditional, with dates at top and discussions of weather—the nonwritten recordings, and the audio recordings in particular, are presented in a format that’s more poetry than prose, with the white space on the page made to represent silence or the hum of a tape reeling blank between utterances.

These interludes

which R. and L. listen to separately

and together

which they listen to separately-together

are based,

unlike the film recordings, which are contained by frames,

on the frameless voice “itself,”

on the rhythms of

the voice “herself” even when him,

a voice cigarette-and-booze-weakened,

hoarsened even when whispering,

and like the voices of the radio, and the voices of the characters reading the paper

aloud, they bring the news

the inner news as they break

with the breath and unspool into

sputter about, and I quote,

“Incidents dwelt on

imagination

dictates its own vocabulary.

Clarity

confusion.”

*

I don’t want to overstay my welcome so as to third-wheel you and this book, so I’ll merely close with a brief comment on Three’s number. Three was a fascination of Quin’s. The number manifests throughout her work: in Three, of course, but also in her novel Passages, the stylistic heir to Three, and, even more explicitly, in her fourth and final published novel, Tripticks. Three is the trinity of Quin’s Catholic upbringing and the governing sum of space (three dimensions) and time (past, present, future). Three troubles the scales of dichotomous, guilt-and-innocence judgment and tips the dialectic. In classical psychoanalysis, we are told that our sex problems are always created through unhealthy binaries, either between ourselves and a mother, or between ourselves and a father, and never through the always healthier trinaries of other prospective sexual partners—people we might very much want to sleep with who might also very much want to sleep with us; people with whom we might not have affirmed our sole legal, ecclesiastical, and, some would say, patriarchal fidelities.

Classical logic exists in the binary, too, and as such it describes mechanistic perfection. By contrast, trinary (also called ternary) logic describes the messiness of being human. In trinary logic, a statement can either be True or False or some indeterminate, or indeterminable, third value: ??? Quin’s brief, bleak life coincided with the development of programmable or stored-memory computing, whose binary logic has since come to master our lives by lashing our pasts and futures together through the 1/0 digitization of all of our writings and recordings. In the sixties, trinary logic, which had no obvious computational or commercial applications, was primarily a mind game played by obscure academics who, tellingly, lacked a standard notation to express their fooling with triunity—as well as by Continental artists (Situationists) such as Guy Debord and Asger Jorn (do yourself a favor and google “triolectics”).

The origins of trinary logic are to be found in Aristotle and his famous proposal—apropos to a novel that devotes so much mind to beachside brutality—about a sea battle that will or will not happen tomorrow: “It is necessary for there to be or not be a sea-battle tomorrow; but it is not necessary for a sea-battle to take place tomorrow, nor for one not to take place—though it is necessary for one to take place or not to take place.” It’s with this statement that Aristotle cast free will into doubt and introduced the problem of future contingents: How can we say that we know that something that has not yet happened, will happen? Future violence by the tideline cannot be true, it cannot be false, it can only be contingent, possible or probable. Quin’s book is the acting out of this conundrum on a more relatable stage: our marriage will last forever; we will never sleep with other people; our sleeping with other people will never affect our marriage; we will always have all the sex we want; we will always want all the sex we have; S will kill herself; S will be killed by others; we will cause S to kill herself; we will never believe, or admit to each other that we believe, that we were the cause.

In our over-recorded, interminably reproducible, and self-interested age, S becomes a martyr. For nowadays there is nothing more rare and valuable and even holy than the unknown, the unknowable, the third-way open and forever contingent.

Joshua Cohen was born in 1980 in Atlantic City. He has written novels (Moving Kings, Book of Numbers), short fiction (Four New Messages), and nonfiction for the New York Times, Harper’s Magazine, n+1, the London Review of Books, The New Republic, and others. In 2017 he was named one of Granta’s Best of Young American Novelists. He lives in New York City.

Ann Quin’s Three , originally published in 1966 by Calder & Boyars, has been brought back into print by And Other Stories with a new introduction by Joshua Cohen. The new edition is published in the U.S. on November 10, 2020.

November 6, 2020

Staff Picks: People, Places, and Poems

Kevin Young. Photo: Melanie Dunea.

The making of history is on everyone’s mind this week. And while it’s hard to look away from that history as it unfolds in real time on our screens, in Delaware and Washington and vote-counting centers around the country, I’ve been glad to have at hand another kind of history, recently made: a new anthology of American poetry. African American Poetry: 250 Years of Struggle & Song, edited by Kevin Young, is a doorstop at north of a thousand pages, but with Library of America’s signature bible-thin paper stock, this inspiring span of American poetics—from Phillis Wheatley to Jamila Woods to Juneteenth of this year—can somehow still fit comfortably in one’s hand. Because I am a stubbornly linear person, my impulse is to start at the beginning and move steadily toward the end, and the thoughtful chronological delineations of Struggle & Song encourage that impulse. But during weeks like this week, in years like this year, being able to enter this volume midstream and explore it in smaller sessions is a welcome thing. Particularly, I’ve found myself reading the sixth section, Blue Light Sutras (1976–1989), and a group of poets whom Young describes as writing “in personal ways about history and its many musics.” Here are Rita Dove and Cornelius Eady, Yusef Komunyakaa and Nathaniel Mackey. And in the Mackey selection—from “Song of the Andoumboulou: 31”—I found a moment that felt like it could be speaking to this moment. There, Myth “wondered where the we we / were after would come / from, awaited what rush / we were told awaited / us.” —Emily Nemens

Between refreshing all the same pages as everyone else I know, I read poetry—single poems, often all my old favorites. I sift through the piles on my bedside table and the bookmarks on my phone for comfort. “I’m too sad to read says the daughter” in Richard Siken’s “Journal, Day Three,” a poem about “Weakness, Truth, Swearing, Precision, More Lies, and the Social Contract.” Like with all Siken poems, in “Journal, Day Three,” every word is a revelation, and there always seems to be a world of bad outside, encroaching, and bad feelings inside that we try our hardest to suppress. What remains in the space between is a constant meditation on distance and detail, the central tension of all his work. “Journal, Day Three” is especially concerned with semiotics, a subject I can only really wrap my head around in poetry. Siken says we are “surprisingly bigger and more vast than these words on the page,” which reminds me of when Robert Hass, in “Meditation at Lagunitas,” writes, “There are moments when the body is as numinous / as words,” and for a moment, I feel bigger than the maps on the screen, the slow percentages. For a moment, I remember I have a body, that I’m not just a formless mass of stress dreams and sadness. The bad world and bad feelings become something precise, something tenable and tied together in “connections we had always felt but only now could see,” like a poem. —Langa Chinyoka

Ashleigh Bryant Phillips. Photo: Missy Malouff.

Imagine you are on a trip through the Carolinas. Strangers at bus stations, breakfast counters, roadhouses all tell you stories, some long, some short, some lucid, some loony. This is the experience of reading Ashleigh Bryant Phillips’s debut collection, Sleepovers. Narrators confess, reminisce, and gossip with an openness and assumed absolution rarely found outside of nameless encounters. Phillips’s way of swooping in and out of the lives of so many people (the table of contents clocks twenty-three stories, one of which you can read in the Spring 2020 issue) is energetic: a man considers infidelity on his way home from a fishing trip; a sex worker imagines reincarnation as a deer; a young woman returns to her country home after moving away to a city. Humming under everything is a darkness, a violence, that the characters themselves cannot fully see, and often you want to pull the veil back further. But being at the mercy of a storyteller is the joy of listening to strangers while waiting for a bus—and so it is here. —Lauren Kane

This has been an exhausting week. Impulsively piping different news sources into each ear, I’ve found myself with next to no energy for reading. One thing that has helped bring me out of this rapid-fire, anxious stupor is an Ilya Kaminsky poem that’s been floating around social media: “We Lived Happily during the War.” It’s not a happy poem; it’s rather dour, actually. But it’s a beautiful piece that demands better of this country, regardless of what happens. —Carlos Zayas-Pons

I have been trying, for the past few days, to find some sort of shelter—in Middlemarch, in music, in food—and I can’t imagine I am the only person for whom nothing has worked. Whatever happens in the near future, something is truly, terrifyingly broken in the United States, and while the degree of brokenness and who is in charge of repair efforts obviously matter, at this moment all comforts seem cold. And so I have ended up back with a writer who makes little attempt to offer comfort. In Joan Didion’s work (the ability to focus or concentrate is long gone, so in between mental Electoral College math exercises, I have been picking up books at random and flipping through to find a sentence that will hold for a second) something is always broken, a person or a place or a system; her writing hems it in and controls it, watching without giving in to the chaos. But if you look closely, the language itself is stretched taut, one turn of the screw from shattering, and that is about how I feel right now. —Hasan Altaf

Joan Didion. Photo: Brigitte Lacombe.

November 5, 2020

Our Interminable Election Eve

William Eggleston, Mississippi, 1976 © Eggleston Artistic Trust

On the eve of the 1976 election, William Eggleston traveled to Plains, Georgia, to photograph the hometown of Jimmy Carter. The landscapes he captured were overgrown yet restrained, rusting shacks and crooked tombstones. As he travels along the road from Mississippi to Georgia, the quiet buzz of anticipation grows. In Sumter, a car driving down the highway emerges from behind a small shack with advertisements painted on the side. In front, stalks of ryegrass bend with the wind. Every piece of the landscape, from its residents to the trees, is both fluid and static. The photographs in Election Eve emit an eerie quiet—a town on the precipice of transforming from a provincial backcountry to a presidential hometown.

Just months before, Eggleston had exhibited a controversial series of color photographs at the Museum of Modern Art that documented what one critic called the “perfectly banal” lives of white Southerners. It is likely that after seeing the exhibition at the MoMA, an editor at The New York Times Magazine asked Eggleston to photograph Carter’s hometown of Plains, Georgia. While the piece never materialized, the photographs he took on the trip were eventually collected in Election Eve, Eggleston’s first published work.

William Eggleston, Sumter, 1976 © Eggleston Artistic Trust

The editor who assigned the piece likely hoped that Eggleston’s interest in the growing prominence of white Southerners would result in colorful portraits of the residents of Plains. But, almost pointedly, human subjects rarely make an appearance in Election Eve. Flickers of life materialize in the background—a dog turning its head, skid marks and soda cans left in the dirt. These traces of human presence remind us that Plains is not a ghost town. Its residents linger just out of sight, frozen, as they await the outcome of the election that, regardless of the result, promised to fundamentally alter their identities and redefine what it meant to be a Southerner.

William Eggleston, Mississippi, 1976 © Eggleston Artistic Trust

The disquiet in Eggleston’s photographs reflects the stakes of the 1976 election. If Carter won (and he did), he would be the first Democrat to break apart the Republicans’ Southern strategy, as well as the first president from the Deep South since before the Civil War. For Southerners, Carter was the great unifier and his election a sign that the South had truly, finally rejoined the Union. The next morning, Carter would appear in Plains for his victory speech, where he stressed unity and a “common devotion to this country.”

William Eggleston, bank parking lot, Plains, 1976 © Eggleston Artistic Trust

But when Eggleston visited Plains on Election Day, the outcome was still unknown. In his photographs, there’s very little to suggest that there even is an election, let alone that he is in the hometown of one of the candidates. In contrast to the cluttered landscape of Trump signs greeting drivers in the Deep South this year, the landscapes in Election Eve are noticeably stark. In fact, Carter’s name appears only once in the collection—on a bumper sticker crammed into the corner of the photograph. The residents of Plains seem hesitant to make their allegiances known, nervous that a show of faith in Carter would be a tacit admission of how much was on the line.

William Eggleston, Mississippi, 1976 © Eggleston Artistic Trust

This past Tuesday night, the South faced a new opportunity to redefine itself. As the demographics of the region move further from the white population that captivated Eggleston, so, too, do its politics shift. While the South has long been majority Black, 2020’s election shows the strides that have been made against disenfranchisement, and how far there is left to go. Georgia, which has only voted Democrat once since it elected Carter, now joins North Carolina and Florida as a swing state. For a moment, even Texas appeared to be within the Democrat’s reach.

William Eggleston, Mississippi, 1976 © Eggleston Artistic Trust

For weeks, we were told that the presidential race would not be decided on election night. The profusion of mail-in ballots will take time to count, and the results will roll in slowly, they said. While the residents of Plains spent just a day in this liminal space, now the nation endures in it for days, if not weeks. The specters of recounts and legal battles threaten to prolong this sense of in-betweenness in perpetuity. Even after this election is decided, unfounded allegations of voter fraud will leave us in a limbo nearly impossible to shake.

In the introduction to Steidl’s recent reprint of Election Eve, Lloyd Fonvielle notes that Eggleston’s gift as a photographer stemmed from his ability to reveal the “unremarked units of spatial perception by which the everyday world is unconsciously ordered.” Election Eve was not just a document of Plains as it stood on Election Day 1976—rather, Eggleston captured the uncertainty of its residents, the tremendous stakes. As we await the results of the current election, the stakes feel just as high, if not higher.

William Eggleston, Election, 1976 © Eggleston Artistic Trust

The visual and informational clutter of this election cycle obscure the underlying reason for our uncertainty. Joe Biden, like Jimmy Carter, has painted himself as a unifier of a fractured nation. His campaign redoubled on the notion that this election was a fight for the “soul of America”—that our self-image as Americans was on the ballot. Like the residents of Plains, we share an unspoken understanding that this election is a referendum on our unity, and the means by which we will define ourselves. Regardless of the results, Eggleston’s photographs are reminders of what hangs in the balance.

William Eggleston, Election, 1976 © Eggleston Artistic Trust

Jonah Goldman Kay is a writer based in New Orleans. His essays and reviews have appeared in Artforum, The Los Angeles Review of Books, and The Brooklyn Rail.

November 4, 2020

The Sky Above, the Field Below

An afternoon practice under the West Texas sun. Photo: Robert Clark.

My introduction to Texas came well before I ever set foot in the state itself. I found H. G. Bissinger’s book Friday Night Lights at a used bookstore when I was a teenager in the early aughts, drifting in the dog days of summer between my junior and senior years of high school. I had just gotten my first car, a brown Nissan Maxima with a faulty alarm and inconsistent shades of window tint. Despite the ways that an engine and four wheels can expand a geographical radius, there are only so many places you can go when you are sixteen years old. And so I spent many of my days simply driving around Columbus, Ohio, popping into stores I couldn’t afford until I worked my way down to the stores I could.

On the cover of that edition of Friday Night Lights was the now iconic black-and-white photo taken by Robert Clark: Odessa Permian football players Brian Chavez, Mike Winchell, and Ivory Christian linking hands together and walking along the sideline of a football field. I was drawn to the book because of this image first. I was a high school athlete, preparing to become a college athlete. I was still young and eager enough to buy into all of the mythologies about brotherhood and family that sports sold me. The captains on my own soccer team would walk out to the middle of the pitch before the game in this same manner: hands clasped together, forming a single chain of movement.

Left to right: Team captains Mike Winchell, Ivory Christian, and Brian Chavez walk onto the field for the pregame coin toss vs. Midland Lee High School. This now iconic image was the cover of the original Friday Night Lights. Photo: Robert Clark.

Being from Ohio, I know there are similar ways to understand the enthusiasm that can set upon an entire community as the days tick toward the weekend. In Massillon, Ohio, Paul Brown Tiger Stadium looms large within the town’s landscape. Boys born in the town are given tiny footballs in the hospital. The Massillon Tigers are among the winningest high school programs in the nation, and their rivalry with nearby Canton McKinley is one of the fiercest rivalries in all of high school sports. Even if you didn’t live near Massillon, you might make the trip up on a Friday night, just to see what all the noise was about. In this way, entering the world of Odessa through the pages of Friday Night Lights felt at least somewhat familiar, even though I was entering a different era of high school football and high school football players. And even though the physical space and concerns of the local population were all different, there was a comfort in the idea that even before I knew what football was, there was a town that revolved around a few hours on a Friday night inside of a stadium. With summer’s spiral into autumn, there was the promise of some escape waiting at the end of the week. If your job was shit or if things at home weren’t great or if you had played once and had some glory slip through your fingers, the game could become a portal to some newer, or better, dreams.

Tracy Rickerson blows up balloons and fills up her boyfriend’s pickup cab in a game-day prank before the Panthers play rival Midland Lee High School. Photo: Robert Clark.

The issue with this, of course, is that the people acting as vehicles toward those dreams are teenagers, some with dreams of their own—teenagers who are flawed, complex, and fighting through the many pressures of being alive and young while also being uniquely responsible for the contentment of their friends, family, and the other people they share a town with. Bissinger does a great job of capturing this in Friday Night Lights, even when he doesn’t paint the town of Odessa in the most generous light. There is, of course, the tragic story of James “Boobie” Miles, who succumbed to a domino effect of tragedies after blowing out his knee during the dying moments of a preseason game before his senior year—an injury that caused his pile of scholarship offers to vanish. Among a great many other things, the book turns a sharp eye to issues of race, as well as perceived usefulness once someone becomes less than a hero. There’s Mike Winchell, the starting quarterback who defied the stereotypes of starting quarterbacks on great teams as being confident, boastful, and easygoing. In the book, Winchell is portrayed as anxious, caring, deeply thoughtful, and prone to surgical self-reflection. There’s also Don Billingsley, the troubled troublemaker with a tumultuous home life, and Ivory Christian, who played middle linebacker with a singular violence, but who, off the field, was reserved and often ambivalent.

Players rest and recover during an early morning practice. The 6 A.M. workouts take place four days a week during the season. Photo: Robert Clark.

It was the generosity of Bissinger’s time and language that worked to afford these students all of their many dimensions and addressed the town as its full self, even if the people inside the town were uncomfortable with that fullness coming to light. When the film version of Friday Night Lights came out in 2004, one drawback to its success—and the subsequent revisit to the book it inspired—was that the real-life players and people from that 1988 Odessa Permian team began being referred to as “characters,” as if they were crafted specifically for this story to play itself out and were not actual people with real lives that extended beyond the ways they were immortalized in the text (a text that was made infinitely more interesting by fate: Bissinger arrived in Odessa surely not expecting a star player to have a devastating injury that would shape the narrative of the story and the narrative of the town so immensely).

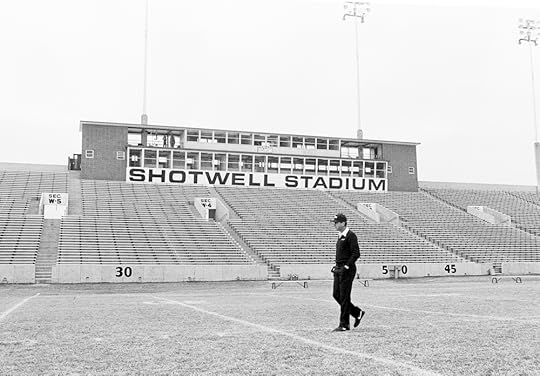

Coach Gary Gaines enjoys a moment of solitude as he walks the field before a road game against Abilene Cooper High School at Shotwell Stadium in Abilene, Texas. Photo: Robert Clark.

A corrective to this, for me, always rested in the photos of Robert Clark, collected now in the book Friday Night Lives: Photos from the Town, the Team, and After. It was his photo of the captains walking hand in hand that led me to the book, after all. In this collection of photos, you are confronted with the aesthetics of a high school football–obsessed town at the end of a decade mired in economic stagnation and decline, as an oil bust drained Odessa of one of its primary sources of work and income. The promise of the 1988 Permian Panthers and the hope placed on them show up in the town’s surroundings. In these photos, you see STATE! ’88 painted haphazardly on a white fence. On the bumper of a Ford pickup, there are stickers declaring its owner a MOJO Booster on one side, and on the other side, another sticker that reads ENDANGERED SPECIES: OILFIELD HAND.

And, of course, beyond capturing the anxieties of a town looking for excitement and emotional renewal through its high school football team, Clark’s photos also do the vital work of reminding us that the central participants in this whirlwind of a story were, at the time, young people: teenagers, who were more than just cogs in the machinery of a place and its history and its obsession. The photos taken at practices are stunning, of course. It is a gift to be able to capture the strain and exhaustion that a morning practice can inflict on a body, and how the body pushes through, no matter what. There are photos of players lifting weights reflected in a mirror, and photos of players sprawled out on the gym floor, waiting for their chance at whatever drill they are called to next. The photos of an afternoon practice translate the weight of expectation, with boosters watching from lawn chairs while players run drills with the sun sketching its heat along their faces. Some get to seek a brief reprieve from it by basking in sprays of water.

Varsity players lift weights following an afternoon practice in the Panthers weight room. Photo: Robert Clark.

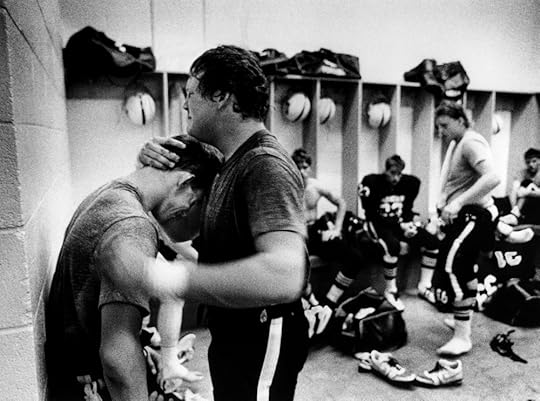

Clark’s most important work, however, is what he captures beyond the pads and helmets and watching eyes of elders: the mischief, the disappointment, the desire for players to cling to each other in moments outside of the game. On the bus to Abilene High, student managers hover around each other while a card game unfolds. I love this photo for how it allows us to see the fullness of these young people, who deserve their own escape from the pressures they were taking on simply by being adjacent to the Permian Football behemoth. In a locker room before a game, a player stands in his uniform socks and two knee braces next to his now empty cowboy boots. It’s a portrait of being, and becoming. After a loss at Midland Lee, Jerrod McDougal cries against the wall in a locker room, while outside, Don Billingsley receives a hug from a woman with tall blonde hair, and his melancholy turns into a wide smile.

Left to right: An unidentified JV football player, student trainer Steve Ward, student trainer Jeff Gasaway, and student trainer Brian Heathman play cards on the way to Abilene for the Cooper game. Photo: Robert Clark.

There are two photos of Boobie that stand out. One is from before the Abilene game. He sits in front of his locker, his face resting inside of his hands, parted into a gentle V shape. His already wide shoulders look even broader with the added bulk of his pads, contrasted with the narrow shape of his locker. A “Terminator X” towel dangles from his waist. This was the game where Boobie returned and attempted to play on his damaged knee, receiving only a handful of carries. In this shot before the game, he already looks defeated, as if he knows the attempts at recapturing his hopes for a limitless future are futile. It makes his arc even more heartbreaking—that he clung so desperately to football as a pathway, he couldn’t see anything else.

Boobie Miles meditates in the locker room before the Abilene Cooper game. Photo: Robert Clark.

The second photo is from after Boobie left the team, frustrated after a game at Midland Lee. Free from the grasp of football, which consumed him for an entire lifetime, Boobie and his beloved uncle L. V. lean into each other and laugh on a porch. It is a photo that situates Boobie as someone beyond the game he played or the injury that altered his life. He’s a kid, spending time with a person who means the world to him. The photos need each other to work. One serves as a reminder of what seemed to be a monumental loss; the other, a reminder of the entire world outside of that perceived loss.

Boobie Miles and his uncle, L. V. Boobie attempted a comeback at Ranger Junior College in Ranger, Texas, and even had a fling in semi-pro football, but his knee was never the same. L. V. was effectively Boobie’s life-support system. He adopted Boobie from his brother and was the stabilizing force in his world. L. V. passed away in 1998. Photo: Robert Clark.

I came to the story of Friday Night Lights late, years after it actually took place. At the time it arrived for me, I thought high school sports was the only thing I had to define myself. I had yet to fall back in love with reading, and so I had yet to fall in love with writing. Winning and losing games was what I knew: getting up earlier than everyone else and running on a track during long, hot summer mornings; joking around in a weight room and occasionally lifting a thing or two. It was such a massive part of my identity that I refused to see beyond it. Despite being drawn to the book by its cover, I didn’t see the photos then like I see them now, years removed from whatever small slivers of athletic glory I got to accumulate. It is funny what distance can afford. When I first read the book, I saw myself as someone entangled with these players solely through our athletic desires and the people pushing us toward them. Now, through the lens of Robert Clark, I’m reminded once again that sports are the backdrop of the story, as they often are. The story has always been about humanity, anxiety, loss, fear, and the promise of a place and the people in it.

Jerrod McDougal embraces Greg Sweatt and punches the wall in the locker room following the loss to Midland Lee. Photo: Robert Clark.

Propelled by Friday Night Lights and the photos in it, I drove to Odessa in 2004, in my early twenties. I drove from Ohio, with no real purpose other than a feeling that I needed to see the school. I needed to see the stadium. All of its mythology felt so larger than life, and I needed to be reminded that it was real, and touchable. It was a foolish trip, one buoyed by what I felt were the dying moments of my reckless youth. I stood outside Ratliff Stadium and I looked at the banners celebrating the titles of the Permian Panthers football team. This was in the month after the film was released. It was late fall, and football season had wound down disappointingly. The team had a 4–6 record, but there were still banners adorning the fences outside of the stadium, cheering the team on. I didn’t stay long, and I didn’t linger much in the town itself. It was just good to know that there was something worth seeing beyond the story that became a national phenomenon—that there were people still living with all it had given them, whether they wanted it or not. I am thankful for Clark’s photos. I am thankful for the fact that they do that same work, pouring some of the humanity back into the narrative. I hope someone younger than I am now finds Friday Night Lights in a used bookstore far from Odessa some day. And when they get the urge to make the trip to see that world for themselves, they’ll look to Clark’s photos instead.

Hanif Abdurraqib is a poet, essayist, and cultural critic from Columbus, Ohio. His next book, A Little Devil in America: Notes in Praise of Black Performance, will be published in 2021.

Excepted from Friday Night Lives: Photos from the Town, the Team, and After , by Robert Clark; foreword by Hanif Abdurraqib. Used with permission from the University of Texas Press, © 2020.

Ella Fitzgerald at the End of the World

On Amazon, there’s a used copy of the triple-disc set from 1985 for sale, the first version issued on CD, in one of those chubby old double jewel boxes. Supposedly, there’s a Verve Master Edition version from the nineties that added a fourth disc, I guess of alternate takes or rarities, but I can’t find that anywhere. On eBay, I could get the original vinyl box set from the fifties or sixties, but it’s really expensive. Plus I have the first LP already. I could try to track down the other LPs one at a time. But what I really want is that fourth CD on the Master Edition version.

This is how my nights unfold as the days get shorter and darker in these uncertain times. After the dog’s last walk, after heaving my son into bed with the Hoyer lift and attaching his CPAP, after the third time my daughter comes out of her night-lit room to share another phrase she’s come up with that contains all the vowels, but before my smoking time on the back deck, before the anxious and rambling conversation with my wife in my little book-and-record-crammed office, and certainly before the Hour of Enforced Unplugging when I finally roll into bed—I scour the web for out-of-print CDs and vinyl. They’re artifacts from a lost time when I was young, and not so poignantly terrified, or from an even more distant past I never experienced, a past that was gone long before I arrived. It’s easy to imagine that those times were simpler, better, easier than the interminable weeks of COVID-19 in Trump’s wrecked America.

Of course, last night interrupted this pattern—I gave in, like any sane person under the thumb of this insanity, and spent the hours on the opposite end of the couch from my wife, the two of us refreshing counters, screaming at virtual needles, in the thrall of our fear and hope for this election. And today, as we’d dreaded and expected, we wait, and I call on one of my time-tested coping mechanisms for, if not solace or even distraction, a kind of anxious business that might help pass the hours between now and the end of forever.

Over the last eight months, my CD and vinyl shopping has gotten seriously out of control. I am, like Theodore Roethke in his poem “In a Dark Time,” longing for a “steady storm of correspondences.” I need at least a package a day to remind me the world’s still out there, that there are things to look forward to. It’s a call for help that online merchants—not just Amazon, but indie record stores trying to survive and strangers selling off their late fathers’ record collections on eBay—are happy to answer.

Streaming threatened to destroy my favorite pastime, the obsessive quest for music (if everything is available, what is there to collect?), until I realized I could simply ignore it and pretend that I only have an album if I have it on a physical medium. Old CDs and records are cheap now; no one seems to want them but me. So I troll the web, leaping from one lily pad to the next, from liner notes to Wikipedia pages to BUY NOW buttons, artists leading me to their friends and collaborators and competitors, whose names I dig out of liner notes and nerdy online info hubs.

I am precisely, and sort of ashamedly, the cliché of the record collector, hoarding my things like T. S. Eliot: “These fragments I have shored up against my ruins.” It’s the collector’s time-honored fallacy: the talismans of this arcane knowledge are weights that keep the days and the hours from floating off into the ether.

At the moment, I’m searching for a playable copy of Ella Fitzgerald Sings the George and Ira Gershwin Song Book, the crown jewel of her songbook series for Verve, recorded from the end of the fifties through the mid-’60s. These are Ella’s most enduring and beloved recordings, on which, at the behest of her manager, producer, and label owner George Granz, she devoted an album apiece to the major composers of the Great American Songbook—the Broadway anthems and radio hits of the early midtwentieth century that became jazz standards, the soundtrack to all our great aunts’ younger days. The Gershwin set, with Ella lavishly backed by Nelson Riddle’s orchestra (see how the useless facts pile up, pinning the windblown sheet of my life in place), is fifty-three songs on several CDs or LPs or a streaming playlist. It is an undeniable masterpiece, Ella’s voice at its peak, weaving in and out of these timeless melodies, which swell and contract as the orchestra carries her like a wave back toward the depths. It’s heaven, it’s soothing, and yet all the world’s heartbreak seems to echo through these songs.

I first discovered Ella Fitzgerald as a teenager, reeling from the death of my mother when I was fourteen. I plunged, as a high school junior, into a mighty depression, one of the effects of which was that I could no longer enjoy music with words—all of that emotion seemed painfully ironic to my little heart, which, for a while, couldn’t feel anything (not unlike today). So I began to explore jazz, music that qualifies as what William Carlos Williams calls, in “The Orchestra,” “sound addressed / not wholly to the ear.” It was music I could think about, could approach without immediately springing my raw nerves. I started with the classics—Louis Armstrong and Miles Davis, and, soon enough, Ella; these words I could handle, if only because I could hear the roiling history beneath them. When I first heard Ella’s infamous live rendition of “Mack the Knife” from 1960, in which she improvises her own lyrics about the very song she’s singing because she forgot the real ones, a little pinprick of light opened (and still opens) in my darkness:

Oh Bobby Darin and Louis Armstrong

They made a record, oh but they did

And now Ella, Ella, and her fellas

We’re making a wreck, what a wreck of “Mack the Knife”

This is play, of course, but it’s also panic, an abandonment of control, a swirling, happy vortex that Ella invites her audience into. In that “wreck,” I hear a whole culture, maybe a whole planet, crawling out from under the shadow of two world wars, desperate for some entertainment, daring to hope for simple joy once again.

Don’t we all feel more than a bit cornered right now? Aren’t we desperate for some joy? What will life be after this virus? What threshold can we cross to delineate now from then? Will Trump’s infinite, blathering loop begin to fade? Will the storm of other shoes dropping finally pass? Regardless of the outcome of the election, will we remember how to spend a bit of our time in the present? Waiting for the future is the opposite of listening to music.

I don’t begrudge anyone their momentary salves, even if they are self-destructive and temporary. Better to destroy oneself than to be destroyed by Twitter. There’s nothing to do now but wait and hope and try to keep the merciless unease in check between refreshes. Ella can’t fix it all, but she’s kind company.

Soon enough this particular wave of obsession for Ella and her long career that stretched well into the heart of my childhood will pass, and I’ll be needling into something else, helpless against the gravity of John Zorn’s out-of-print box set of all the Naked City albums (going for $75 on eBay), the Naxos edition of the complete rerecorded works of Arnold Schoenberg conducted by an aging Robert Craft (available in two box sets on Amazon), or the reissue of M. Ward’s Post-War on color-splattered vinyl available only to members of my LP-of-the-month club.

The election coincides with my forty-first birthday. Time keeps yanking me along in its one damned direction, though this nether region we find ourselves in today is a hitch in the flow, an eddying place, a vortex, though not a joyful one. Can you blame me for leaning, however futilely, toward the past? Is it so lame to want, like Sylvia Plath huddling in her father’s ear in “The Colossus,” to fall asleep for eternity, or at least for the next few weeks or months or years, nestled cozily between the discs of a comforting jazz box set, the liner notes crooning like a lullaby? “I have wasted my life,” wrote James Wright. Meanwhile, we must survive the election. Can I play you something beautiful?

“Mack the Knife” from Ella’s 1960 Live in Berlin LP:

“The Real American Folk Song”:

“Don’t Worry ’bout Me” from Easy Living:

Craig Morgan Teicher is the digital director of The Paris Review and the author of several books, including The Trembling Answers: Poems and We Begin In Gladness: How Poets Progress.

November 3, 2020

Redux: A World Awash in Truth

Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

Claudia Rankine. Photo: John Lucas. Courtesy of Graywolf Press.

This week, The Paris Review is dwelling on politics, literature, and the U.S. election. Read on for Claudia Rankine’s Art of Poetry interview, Matthew Baker’s short story “Why Visit America,” and Martha Hollander’s poem “Election Night.”

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, and poems, why not subscribe to The Paris Review? Or take advantage of our new subscription bundle, bringing you four issues of the print magazine, access to our full sixty-seven-year digital archive, and our new TriBeCa tote for only $69 (plus free shipping!). And for as long as we’re flattening the curve, The Paris Review will be sending out a new weekly newsletter, The Art of Distance, featuring unlocked archival selections, dispatches from the Daily, and efforts from our peer organizations. Read the latest edition here, and then sign up for more.

Claudia Rankine, The Art of Poetry No. 102

Issue no. 219, Winter 2016

The relationship between public engagement and private thought are inseparable for me. I worked on Citizen on and off for almost ten years. I wrote the first piece in response to Hurricane Katrina. I was profoundly moved by the events in New Orleans as they unfolded. John and I taped the CNN coverage of the storm without any real sense of what we intended to do with the material. I didn’t think, obviously, that I was working on Citizen.

But for me, there is no push and pull. There’s no private world that doesn’t include the dynamics of my political and social world. When I am working privately, my process includes a sense of what is happening in the world.

Why Visit America

By Matthew Baker

Issue no. 230, Fall 2019

And yet that winter we found ourselves united by a common sentiment. We were fed up with our country. The executives were busy making donations that funded the campaigns of the politicians, the politicians were busy passing laws that protected the interests of the executives, and pretty much nothing else seemed to be getting done. We were antigovernment, we were anticorporate, but mostly we were normal people who couldn’t afford to buy an election and had come to understand that our votes didn’t mean shit.

Election Night

By Martha Hollander

Issue no. 145, Winter 1997

The first Tuesday in this warm November

brushes Long Island in a last caress

before winter repels our communities

like a storm door slamming on a windy day.

Gentle enough, in fact, for the beach.

Here to beckon to the Indian sunset

are joggers with their superb, joyful dogs,

a few rebels beating the commute,

and a pair of lovers murmuring to the crunch

of sand in the folds of their heavy leather jackets.

Change, they all desire change, a radiant

new face, or a world awash in truth …

And to read more from the Paris Review archives, make sure to subscribe! In addition to four print issues per year, you’ll also receive complete digital access to our sixty-seven years’ worth of archives. Or take advantage of our new subscription bundle, bringing you four issues of the print magazine, access to our full sixty-seven-year digital archive, and our new TriBeCa tote for only $69 (plus free shipping!).

When Waking Begins

Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo, The Procession of the Trojan Horse in Troy (detail), 1760, oil on canvas, 15 1/4 x 26 1/4″. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Glowing brighter and brighter. Slowly the eyes open. Rays fall across retinas. Drowsily they roam about and, for a brief spell, memory of reality meshes with this most current impression and the space becomes both familiar and strange. Then waking begins.

Walter Benjamin writes that every true waking is a reshaping of reality. He describes this waking as a technique: the reclamation of what is past, not as complete facts or truths but as a period of time that can be reshaped simply by making contact with the waker’s present. Benjamin’s interest is focused on sleeping and waking as collective acts. In this sense, revolution—or awakening—is to wake from a prolonged collective slumber, and Benjamin’s moment of waking is the moment in which memory is shaped anew, in which the group—the masses—gradually reclaims its self-awareness through political action and becomes capable of reformulating reality, of providing an explanation of the dream in which it was caught, and emerges from collective absence into a new reality.

In The Arcades Project, Benjamin writes, “The coming awakening stands, like the Greeks’ wooden horse, in the Troy of dreams.” Waking waits for the right moment to attack the land of sleep and liberate it. The wakers want to be freed from sleep’s grasp and the only way this can happen is to invoke the incomplete past so that it might be renewed beneath the gaze of the present moment, changing both past and present. For history is not a succession of finite moments but a chain of breaks. And waking, in Benjamin’s understanding, is memory’s rebirth at the fleeting intersection of past and present, an instant that flares like a spark: reality ceases to be a stage on which history repeats itself and becomes a living substance in which the gunpowder of history detonates.

—Translated from the Arabic by Robin Moger

Haytham El Wardany is an Egyptian writer of short stories and experimental prose who lives and works in Berlin.

Robin Moger is a translator of Arabic prose and poetry who is based in Cape Town, South Africa.

From The Book of Sleep , by Haytham El Wardany, translated by Robin Moger. Excerpted by permission of the publisher, Seagull Books. Distributed by University of Chicago Press. First published in English translation by Seagull Books © 2020.

How to Read the Air

I had planned for weeks this trip to the ocean, to think about birds. And I did go. But the night before, police officers lynched a man in my neighborhood in Philadelphia. Then came the insult of low and constant helicopters, and cops terrorizing our streets, and curfew, and troops deployed in the city, again. So maybe I did not think about birds the way I had intended—though I did think about birds, impossible not to think about birds on the ocean where they take up all the space, where even air and water they push out of the way. Laughing gulls, herring gulls, great black-backed gulls, Ross’s gulls; terns, oystercatchers, sanderlings, sandpipers, plovers. Ospreys. Brown pelicans.

Why birds? Because to make sense of things this desperate fall I have been rereading the Greeks, and the Greeks say birds tell us what is to come.

In ancient Greece and later in Rome, augurs foretold the future by interpreting the flight patterns and calls of birds. Augury, in Greek ornithomancy, from ορνις (ornis, fowl) and μαντεία (manteia, divination): reading birds for the will of the gods. Pliny the Elder says Teiresias, the seer in the court of Thebes, invented augury. (Teiresias told Oedipus that the king was his own father’s murderer.) What birds said, went. The bird-savant Calchas prophesied that Agamemnon must sacrifice his daughter in order to sail his ships to win his war at Troy, and so, by most accounts, the maiden was put to death. Taking the auspices—discerning divine will from the flight of birds—makes sense because birds fly closer to the empyrean, where gods dwell, which makes the bird’s-eye view closer to God’s.

How to read the birds this year, this fretful year pierced by planetary sorrow and the siren call of ambulances and police cars? In the American Southwest, autumn began with migratory birds falling out of the sky, dead. It could have been the West Coast wildfires that caused the birds to deviate from millennial routes and lose nurturing layover grounds, and polluted their lungs with toxins. It could have been an unprecedented swing in air temperature, a token of climate change. It could have been a combination of factors: the Anthropocene has been killing North America’s birds for some time. A year before the mass die-off in the Southwest, ornithologists reported that three billion wild birds (one bird out of four) have vanished from the continent’s air in the last fifty years.

And not only on this continent. On the last day of 2019, I pilgrimed to the wetlands of Djoudj, one of the world’s largest sanctuaries for migratory birds, many of them Palearctic, where a longtime game warden told me that fewer seasonal birds come each year to the Senegal River delta, and entire species no longer come at all. Cities and deserts swallow their habitats, men hunt their kin, pesticides poison their eggs. Climate change uncouples the timing of resources from the timing of migrations, syncopates their traveling cycles, puts the birds out of step with themselves. The birds are confused.

TEIRESIAS [to KREON]: I hear the birds they’re bebarbarizmenized they’re

making monster sounds

—Sophocles, Antigone, tr. Anne Carson as Antigonick (I am using the translator’s spelling here and below).

This September, after it rained dead birds, a Ph.D. student of ornithology and phylogenetics at the University of New Mexico collected and photographed 305 bird corpses representing six species: 258 violet-green swallows, 35 Wilson’s warblers, six bank swallows, two cliff swallows, one northern rough-winged swallow, a MacGillivray’s warbler, and two western wood pewees. Laid out on a grid and photographed from above, the birds make a pattern like a page of text, each bird a word. The breasts and abdomens of the warblers beacon a startling yellow alarm.

*

To know what is coming is to perceive control; and the mind is all about control, particularly in the cerebral, capitalist, goal-oriented Global North. We want to control, or, in neuroscientific terms, we want to exercise cognitive control, our mysterious ability to behave in accord with the goals we set. Put simply: if our cortex is informed, then (we think) we can establish a logic that can (ideally) help us predict the future so we can act in ways that (we hope) will allow us to control it—for, ultimately, humans want to control the future, or to believe that they can. We may say we like to be surprised, astonished, but we like to be surprised in a particular way that is expected or suits our projected needs. This is why children like to hear the same stories. Their predictability is something to hold onto. This is why I am rereading the classics, which I first read as a very young child: it is like worrying a rosary or a wave-grooved seashell you keep in your pocket, something familiar for the fingers to run over and over. This is why we read projections for how long the pandemic will last, or who will win the election, or whether the global uprising against racism will prevail: we want to know when those of us who survive can go back to normal. We want to project that normal.

Three kinds of people tell us the future: prophets, scientists, and writers. One could argue that writers occupy the liminal space between the other two. The writer’s impulse to draw connections, identify patterns, establish syllogisms—what cognitive psychologists call “the enormous complexity, and idiosyncrasy, of human minds, the detailed contents of which are largely unknown even to the individual concerned”—seems irrepressible, as if our neurons force us to make sense of all things, all the time. Like the bird-reading seers of ancient Greece, we cannot help ourselves.

In Islam, the concept of predestination is one of the six articles of faith, like the Oneness of God and the Day of Resurrection. Maktoob, one says—it is written. Maktoob, مكتوب, has the same root as the word “book,” kitab, کتاب; perhaps this is because books allow us to foresee (they say great writers have the gift of foresight). What, then, is a prophecy? It is what is already known. Those who can interpret the writing—prophets, scholars, poets—simply make it visible to us. Joseph Brodsky (raised, too, on plentiful Greek myths) says literature “is a dictionary, a compendium of meanings for this or that human lot, for this or that experience. It is a dictionary of the language in which life speaks to man. Its function is to save the next man, a new arrival, from falling into an old trap, or to help him realize, should he fall into the trap anyway, that he had been hit by a tautology.”

What do the birds foretell? From the shore in New Jersey I watched a murmuration of plovers skim the ocean. It stretched and compressed, tumbled, changed shape, now a horse pulling a chariot, now a goldfish flaunting a mermaid-princess tail; it narrowed into a long line that glided just above the waves like a snake, then, lifting, balled up again into a sphere. Then, one after another the birds folded their wings and plunged into the silver-banded sea. If “low-flying birds symbolize earth-bound attitude [and] high-flying birds, spiritual longing,” as Juan Eduardo Cirlot suggests in his Dictionary of Symbols, then the plovers embody how torn we are between the noble and the base. Or maybe they were simply fishing. Three pelicans sortied on their bombing raid. The pelicans are early harbingers of climate change; until the eighties they rarely showed up north of the Carolinas. To see them here at the end of October, after the first frost, tells a story of planetary-scale negligence; surely it must augur something, too, I thought. Then a coast guard helicopter droned into sight, and brought my mind back to the howling grief of Philadelphia. Walter Wallace Jr. was twenty-seven, just three and four years older than my children. I thought of his mother, who woke up with a son one morning, and the next morning, without.

*

A few days before I went to the ocean, I spent time with Cy Twombly at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Twombly painted Fifty Days at Iliam in 1977–8 after reading Alexander Pope’s translation of The Iliad; the ten large sequential canvases were bequeathed to the museum in 1989. All but the first one are exhibited in one big gallery. The first, Shield of Achilles, hangs on its own in a small antechamber that serves as a kind of a foyer. It always unnerves me the most. It is a vortex of crazy brushstrokes, a hurricane building, and its colors hold water and metal and blood, like a Greek chorus, a prophecy, a premonition.

KASSANDRA: I lose my screams they find me

again!

The dread work of prophecy buckles me

down to its BAM BAM BAM

—Aiskhylos, Agamemnon, tr. Anne Carson

Some of the canvases in the main gallery spell a mad violence of names of gods and heroes of the war at Troy. But the names of the two prophets, Cassandra and Calchas, are effaced—hers written over and over in graphite, his spackled roughly with palmfuls of white paint. The prophets are gone. Birds appear and vanish, and no one is there to interpret their flight.

KLYTAIMESTRA [of KASSANDRA]: Does she talk only “barbarian”—those

weird bird sounds?

Does she have a brain?

—Aiskhylos, Agamemnon, tr. Anne Carson

*

When I drove back from the beach a cardinal flew alongside the car for a bit, opening her wings then closing them, opening and closing, always catching herself just in time to keep going, stringing invisible scarlet swags through the autumn bush. That flight pattern, I once read, is called flap-bounding. I do not know what it means. It is very beautiful to behold.

*

The Talmud says there was in Judea a rabbi who counted among his friends the immortal prophet Elijah. During his earthly tenure, in the ninth century before the common era, Elijah had raised the dead, received nourishment from desert ravens, brought down rain and fire from the sky, parted waters with his cloak, and finally ascended to everlasting life in heaven. But from time to time he returns to earth; maybe he is lonely for mortal company. They say he fights against social injustice. So one day, about a thousand years after Elijah’s ascension, he and the rabbi took a stroll through a busy marketplace, and the rabbi asked the prophet if anyone among the people gathered there belonged in the World to Come. Elijah pointed out two brothers. The rabbi caught up with them and asked what they did for a living. We are badkhenim, they said, poet-jesters. We cheer up the sad.

The sages interpret the fable thusly: To truly pray we must first achieve a state of exultation, which means that joy, not sorrow, brings man closer to God. Poets help us make our prayers heard.

What does it mean to cheer up the sad, now? I would like to ask my badkhen ancestors, who survived dispersals and deportations and pogroms, but all the poets in my line are gone. An older writer friend tells me that the role of a writer in America today is to help the readers be less afraid. But I am also afraid. I am afraid for the lives of my neighbors in West Philadelphia, afraid for the lives of my loved ones around the globe, afraid for the health and soul of the world. Was Euripides afraid, or Sophocles? Their books do not help me feel fearless. They help me to better articulate the sorrow, not so that I can see a path ahead, but so that I can have the strength to take it. They remind me, from twenty-five hundred years back—before the Black Plague, the Middle Passage, and the Holocaust—that for the most part, with great sorrow, and with great unexpected delight, we, those of us not destroyed en route, have caught ourselves just in time to keep going.

Homer said we ride into the future facing the past. Maybe the simplest prophecy is that we have made it this far. (“Trust the hours. Haven’t they / carried you everywhere, up to now?” writes Galway Kinnell.) In Economy of the Unlost, Anne Carson’s meditation on two other lyric poets, Paul Celan and Simonides of Keos, she puts it this way: “a poet is someone who traffics in survival.”

The morning before returning to Philadelphia, I stood on the beach. A gale blew, a nor’easter, and it was raining, and all the birds sat facing the green-black sea, the way birds have done forever in the face of a storm.

*

My Fulani friends in the Malian Sahel say that if you catch a pied crow alive, and pull down its eyelids, you will find a sentence from the Quran written in Arabic on the sclera of its eyes; reading the sentence grants you one wish. But none of my friends has ever caught one. Pied crows, anyone will tell you, are very hard to catch.

Note that it is the bird’s eye that matters, not the seer’s. Many celebrated prophet-poets are or eventually became blind: Ahijah the Shilonite, Teiresias, Phineas, Homer, Surdas. Jorge Luis Borges, Robert Hayden, Audre Lorde, W. S. Merwin. It is written; they do not have to physically see the future themselves to spell it out.

*

On the last day of October there was a rally at Malcolm X Park, halfway between Walter Wallace’s home and mine. Two or three hundred people from the neighborhood, all masked because of the raging coronavirus pandemic, gathered in grief and rage and disgust. A police helicopter hovered overhead, a deranged, menacing bird basking in the cold sun of autumn. Every night after the murder, police helicopters hovered over the neighborhood. Their sustained sonic assault overlaid everything, even the metallic call of night-flying geese. It was not lost on any of us that thirty-five years earlier a police helicopter hovered above this very neighborhood and then dropped a bomb on a house full of people, five blocks away from where Wallace was murdered, killing five children, six adults, and reducing to ashes sixty-one homes. This helicopter recalls that other helicopter. Neuroscience calls this kind of memory pattern recognition. It is like predicting, except in reverse. For example, pattern recognition was why in 2003, when the United States led an attack on Iraq, every household and business in Iraqi Kurdistan kept a caged canary: people were afraid that Saddam Hussein would retaliate with chemical weapons against the Kurds, as he had in 1988, when his bombers had dropped mustard gas and nerve gas on the town of Halabja, killing five thousand people in two days. In the spring of 2003, some Peshmerga fighters even brought birds to the trenches. A war reporter, I spent those early days of the dark war with a gas mask on my belt, surrounded by trilling yellow birdsong.

If the canaries foretold the deaths of the nearly 290,000 Iraqi people that would result from that invasion, it was a prophecy none of us could read.

On the sad walk back from Malcolm X Park I saw a man with a bicycle standing on a sidewalk, looking up; I followed his gaze to a host of sparrows. There must have been more than a hundred of them. The birds spooled out of a linden tree in a long scarf that billowed and contracted, and flew across the street and settled to chitter in the branches of a golden gingko on the other side—then exploded out of the gingko, shaking down a foul-smelling hail of pink berries, and pulled across the street again, ever condensing and expanding, shape-shifting like the plovers on the seashore, their flapping wings even noisier than their hectic chirping, almost noisier than the police helicopter—then gathered to rest in a low bush near a café, but only for a second, streaming upward again toward the taller trees up the road. I laughed, and the man with the bicycle, I could hear, also laughed behind his mask.

“What are they doing?” I asked the man; maybe I took him for an augur. Maybe I hoped he was an augur.

“I don’t know,” he said. “They seem to be just going back and forth.”

Anna Badkhen is the author of six books, most recently Fisherman’s Blues. A Guggenheim Fellow, she is at work on An Anatomy of Lostness.

November 2, 2020

The Art of Distance No. 32

In March, The Paris Review launched The Art of Distance, a newsletter highlighting unlocked archive pieces that resonate with the staff of the magazine, quarantine-appropriate writing on the Daily, resources from our peer organizations, and more. Read Emily Nemens’s introductory letter here, and find the latest unlocked archive selection below.

“A biographer, a novelist, and a poet walk into a voting booth. This isn’t the setup to a joke—it’s the truth of election week in America: writers, among millions of other Americans, are casting their votes for the next president of the United States. Around the office we’ve been talking about how literature can help us understand this challenging moment and how it might help us persevere. I don’t expect literature to keep up with this week’s news cycle. Nor do I expect literature to eclipse the news: sometimes there are actions (like voting) that need to be taken away from the page. But I do believe what Charles Johnson said in his Art of Fiction interview, quoting Ishmael Reed: ‘A novel can be the six o’clock news.’ Literature can hold the truth, can assess current events and predict future outcomes with insight and nuance absent from punditry and statistical analysis. So while we’re all watching the news, I encourage you to occasionally click away from Twitter feeds and cable stations. Make space for literature this week. I think writers’ insights might be particularly valuable in the days ahead, as a clarifying lens and a countervailing force, a decoder ring and, sometimes, a balm. As Manuel Puig put it, ‘I like to re-create reality in order to understand it better.’ May we all understand the world a bit better once this week is through.” —EN

Photo courtesy Dwight Burdette / Wikimedia Commons.

Whatever your political leanings, this is going to be a complicated week. There’s no one literary mood or mode that’s right for today, so here, in addition to the unlocked interviews quoted in the GIF above (Robert Caro, Ali Smith, and Rae Armantrout), are a handful of pieces that offer passionate engagement with the past and present, and a look at the relationship between literature and politics.

“The personal is especially political when it spreads fingers out into the world,” says Grace Paley in the Art of Fiction no. 131, in which she goes far in explaining how all stories have their political dimensions.

Kevin Young’s elegy and tribute “Homage to Phillis Wheatley” speaks for and about uniquely American brands of ambivalence and passion, of a “sadness too large to name” and also “leaning, learning / to write” in the light cast by a foundational poet’s legacy.

Mary Szybist’s gorgeous “The Molten Saints inside Me Do Not Quiet” conjures a familiar sort of inner restlessness and global emergency (“the world is burning, the world is burning”), which surprisingly gives way to a kind of heartfelt abandon.

James Baldwin, in the Art of Fiction no. 70, says, “The whole language of writing for me is finding out what you don’t want to know.” He holds up many mirrors in his interview, mirrors that are as important to look into today as they were when the interview was published almost forty years ago.

The British author John Wain’s poem “The New Sun” invokes the dawn of a new era, with its attendant terrors and ecstasies, asking “how to bear the pain of renewal.” It seems like the right place to pause this little journey into the unknown.

Sign up here to receive a fresh installment of The Art of Distance in your inbox every Monday .

The Messiness of the Suburban Narrative

There are sexier identities than “writer of the suburbs.” Such spaces still call to mind images of picket fences, cul-de-sacs, and gated neighborhoods, uniformly and exclusively white. When someone asks me where I’m from—that familiar fraught question—I still catch myself saying that I grew up in Dallas, or at times the mythically vague “Texas.”

Plano, Texas, where I spent a decade of my adolescence, now boasts a quarter million residents, a quarter of whom were born in a different country. It’s the home of Pizza Hut, Frito-Lay, the bankrupt J. C. Penney, a host of global tech companies, and a recently relocated Toyota North America. And yet, there’s a cultural specificity to Plano. Its Costco sells edible bird’s nest, a Chinese delicacy that none of my family in China has had a chance to taste.

To call Plano a suburb may be a stretch when it’s bigger than cities like Orlando, Newark, and Madison. But beyond the swirl of language and music and food, a suburban state of mind persists. One can feel it acutely this year, as white-collar immigrants stay home and earn their usual salary while working-class immigrants mow the lawns, take away the trash, and maintain the roads. It’s there in the undercurrent of casual remarks: how the police are probably too scared to do their jobs now, how there’s been a horrific murder in a neighborhood like ours, how it could happen even here. Near my parents’ house in a suburb bordering Plano, a Muslim family sits in their driveway on lawn chairs, watching their kids scooter past a house with multiple Trump/Pence signs and a cute Pomeranian that won’t stop barking. Finally, the owner comes outside and snaps at the dog to be nice.

*

Suburban niceness was a product of people moving to live with the kinds of people they preferred to be nice to. In the thirties, New Deal programs helped middle-class white Americans enter the suburban housing market, while nonwhite, non-Christian, and poor people were largely denied access. Rather than curb neighborhood segregation, the federal government skewed property values by rating white suburbs at much higher grades than Black neighborhoods. Through the civil rights era to present day, suburban strategies of exclusion have endured, often taking different forms: land-use controls against affordable housing, resistance to school integration, and a lack of public transportation and social services to accommodate the growing number of low-income residents being pushed out of cities.

There’s a new wrinkle to the old narrative: since at least 2000, more than half of immigrants to the nation’s largest metro areas have settled in the suburbs. Among these immigrants are those who are university educated and upwardly mobile, beneficiaries of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965. Asian Americans, the fastest-growing racial and ethnic minority group in the suburbs, are the majority ethnicity in seven “ethnoburbs” in the Bay Area. In Plano, they make up 23 percent of the overall population. Lily Bao and Maria Tu, two first-generation immigrants from China and Taiwan, respectively, became the first Plano residents to break the “bamboo ceiling” when they were elected to the city council in 2019.

Asian Americans have reshaped the place where I grew up, but remnants of the original Levittown mindset live on in Bao’s and Tu’s platforms, namely in their resistance to apartments and high-density housing as a way to “keep Plano suburban” (Bao’s campaign slogan, with strong echoes of Trump’s current one).

And yet, there’s something about Bao’s conservatism that updates the old suburban talking points and separates her message from the polite company chatter of, say, Cheever’s Shady Hill characters. Perhaps it’s the way she leans into diversity—albeit a more exclusive definition of “diversity.” In an interview for Plano Magazine, Bao touts the benefits of welcoming highly educated and skilled workers, immigrants who love their country, drive their kids to excel in school, and receive acceptance in return. It’s a coded description, reminiscent of an observation that sociologist Noriko Matsumoto noted in the suburban New Jersey Asian American subjects in her Beyond the City and the Bridge: a “resurgence of ethnic pride” tied not only to “the growing numerical presence of Asians” but also their “visible socioeconomic success.”

“We [Asians] as ‘model minorities’ work hard and pay taxes,” Bao states, “but seldom have our voices heard.” Her call for greater Asian American representation in politics echoes those made in other areas of American life, particularly in entertainment. These calls are often raised and supported by people like me, progressives who grew up in America under vastly different circumstances than their parents, with the same justification as Bao’s: Look at how much money Crazy Rich Asians made. Asians are good business. We’ve paid our dues, and it’s time we get a seat at the table.

*

As a fiction writer, I’ve thought a lot about how Western conventions of narrative lean on differentiation and change. How does the protagonist change? How does the protagonist stand out from the rest of the characters? These are questions we learn to ask in high school English classes and creative writing workshops, ones that readers expect to be resolved. As we turn the pages, we trust characters will advance through emotional and physical terrain to end in a different place from where they began.

But as the suburban story has evolved, with new faces and entry points, so has its relationship to the narrative of change. Many newcomers to the suburbs are not only surviving but excelling. They are reshaping the story in their own image, but they are also living with the knowledge that such a story is precarious. Perhaps to preserve the new suburbs in which they finally feel at home, they also latch onto aspects of the old narrative, resisting the principles that gave them space to enter the suburban story in the first place.

I was wrestling with how a storytelling arc built on principles of change would play out with a Chinese immigrant family living in the suburbs. I wrote a novel centered on a family living in Plano in the early aughts, strangers not only to the American suburbs but to one another. A family that, in their previous life, had suffered as a consequence of standing out. More change was the last thing on their minds; they’d moved to the suburbs to avoid the very development that readers crave. Even as the cracks in their “model home” begin to show, and their status as “model minorities” collapses under pressure, the family refuses to reinvent themselves in a way that would satisfy my hopes for them. I wondered then how to sit with that tension, with characters who did not offer me any shortcuts to sympathy.

These days I find myself imagining the family beyond the page. What if they were here with us, in 2020? Maybe the parents have weathered the financial crisis, found an Asian church, made a few white friends. Maybe they dream in English. They’ve lived in the States (and Texas) longer than they lived in China. On WeChat, many of their friends who stayed in China have become increasingly nationalistic, defending the government crackdown on the Hong Kong protests and the internment of Uighurs in Xinjiang. The parents in my novel remember what they lost after war and through the Cultural Revolution: homes and possessions and loved ones, yes, but also the memories they never got to have. Everything they’ve endured in Plano, including the current pandemic, feels like a small price to pay for finding their rightful home.