The Paris Review's Blog, page 140

November 2, 2020

We Must Keep the Earth

In his new book Earth Keeper: Reflections on the American Land , N. Scott Momaday relays stories from his childhood, recounts Kiowa folktales, and entreats readers to take a deep interest in protecting and revering the natural world. An excerpt appears below.

N. Scott Momaday, Rock Tree.

I am an elder, and I keep the earth. When I was a boy I first became aware of the beautiful world in which I lived. It was a world of rich colors—red canyons and blue mesas, green fields and yellow-ocher sands, silver clouds, and mountains that changed from black to charcoal to purple and iron. It was a world of great distances. The sky was so deep that it had no end, and the air was run through with sparkling light. It was a world in which I was wholly alive. I knew even then that it was mine and that I would keep it forever in my heart. It was essential to my being. I touch pollen to my face. I wave cedar smoke upon my body. I am a Kiowa man. My Kiowa name is Tsoai-talee, “Rock Tree Boy.” These are the words of Tsoai-talee.

*

Near Cornfields I saw a hawk. At first it was nothing but a speck, almost still in the sky. But as I watched, it swung diagonally down until it took shape against a dark ridge, and I could see the sheen of its hackles and the pale underside of its wings. Its motion seemed slow as it leveled off and sailed in a straight line. I caught my breath and waited to see what I thought would be its steep ascent away from the land. But instead it dived down in a blur, a vertical streak like a bolt of lightning, to the ground. It struck down in a creosote bush. After a long moment in which there was a burst of commotion, the great bird beat upward, bearing the limp body of a rabbit in its talons. And it was again a mote that receded into nothing. I had seen a wild performance, I thought, something of the earth that inspired wonder and fear. I hold tight this vision.

*

The night the old man Dragonfly came to my grandfather’s house the moon was full. It rose like a great red planet above the black trees on the crooked creek. Then there came a flood of pewter light on the plain, and I could see the light ebb toward me like water, and I thought of rivers I had never seen, rising like ribbons of rain. And in the morning Dragonfly came from the house, his hair in braids and his face painted. He stood on a little mound of earth and faced east. Then he raised his arms and began to pray. His voice seemed to reach beyond itself, a long way on the land, and he prayed the sun up. The grasses glistened with dew, and a bird sang from the dawn. This happened a long time ago. I was not there. My father was there when he was a boy. He told me of it. And I was there.

*

On the short-grass prairie where I was born, and where generations of my family were born before me, grasshoppers are innumerable in the summer. In the shimmering waves of August heat they make a dense green and yellow cloud above the red earth. It is slow in motion, and sometimes hesitant, like an ascending swarm, and it is irresistible. You walk along, and you are constantly struck by these bounding creatures. If you catch one and hold it close to your eyes, you see that it appears to be very old, as old as the earth itself, perhaps, and that its tenure is as original as your own.

*

I dream of Dragonfly, and always in my dreams I am young and he is old. When I see his face it is drawn and wrinkled, the face of a holy man, and there are faint stains of red and yellow paint on his cheeks and about the mouth, made from powdered berries and pollen. His hands have pronounced veins, and the fingers are long and bent from a lifetime of use. He is thin, and his skin is weathered, burned by the sun and wind. His voice, too, is thin, and his speech is carefully measured. He speaks of things that are the most important to him, spiritual things. He keeps the earth, and he has belonging in my dreams.

*

There was a tree at Rainy Mountain. It was Dragonfly’s tree. Beneath this tree Dragonfly spoke to Daw-kee, the Great Mystery. There the holy man was made holy. He was told that every day he must pray not only to witness the sun’s appearance, but indeed to raise the sun, to see to it that the sun was borne into the sky, that each day was made by the grace of Dragonfly’s words. This was a great responsibility, and Dragonfly carried it well. And at the holy tree he was told of the earth.

*

We humans must revere the earth, for it is our well-being. Always the earth grants us what we need. If we treat the earth with kindness, it will treat us kindly. If we give our belief to the earth, it will believe in us. There is no better blessing than to be believed in. There are those who believe that the earth is dead. They are deceived. The earth is alive, and it is possessed of spirit. Consider the holy tree. It can be allowed to thirst. It can be cut down. Worst of all, it can be denied our faith in it, our belief. But if we speak to it, if we pray, it will thrive.

*

N. Scott Momaday, Celebrant.

When we dance the earth trembles. When our steps fall on the earth we feel the shudder of life beneath us, and the earth feels the beating of our hearts, and we become one with the earth. We shall not sever ourselves from the earth. We must chant our being, and we must dance in time with the rhythms of the earth. We must keep the earth.

*

I am an elder, and I keep the earth. I am an elder, and I am a bear. When I was a child I was given a name, and in that name is the medicine of a bear. I speak to the bear in me:

Hold hard this infirmity.

It defines you. You are old.

Now fix yourself in summer,

In thickets of ripe berries,

And venture toward the ridge

Where you were born. Await there

The setting sun. Be alive

To that old conflagration

One more time. Mortality

Is your shadow and your shade.

Translate yourself to spirit;

Be present on your journey.

Keep to the trees and waters.

Be the singing of the soil.

*

The story from which my name comes is also the story of my seven sisters, who were borne into the sky and became the stars of the Big Dipper. The story is very important, for it relates us to the stars. It is a bridge between the earth and the heavens. There is no earth without the sun and moon. There is no earth without the stars. When we die, Dragonfly says, we go to the farther camps. Death is not the end of life. There is life in the farther camps. The stars are fires in the farther camps.

In the making of my song

There is a crystal wind

And the burnished dark of dusk

There is the memory of elders dancing

In firelight at Two Meadows

Where the reeds whisper

I sing and there is gladness in it

And laughter like the play of spinning leaves

I sing and I am gone from sorrow

To the farther camps

*

The waters tell of time. Always rivers run upon the earth and quench its thirst. Bright water carries our burdens across long distances. Without water we, and all that we know, would wither and die. We measure time by the flow of water as it passes us by. But in truth it is we who pass through time. Once I traveled on a great river though a canyon. The walls of the canyon were so old as to be timeless. There came a sunlit rain, and a double rainbow arched the river. There was mystery and meaning in my passage. I beheld things that others had beheld thousands of years ago. The earth is a place of wonder and beauty.

N. Scott Momaday was born in 1934 in Lawton, Oklahoma. A poet, novelist, playwright, teacher, and painter, his accomplishments in literature, scholarship, and the arts have established him as an enduring American master. He is the recipient of numerous awards and honors, including the Pulitzer Prize for his novel House Made of Dawn, a National Medal of Arts, the Academy of American Poets Prize, the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award for Lifetime Achievement, and the Dayton Literary Peace Prize Ambassador Richard C. Holbrooke Distinguished Achievement Award.

From Earth Keeper: Reflections on the American Land , by N. Scott Momaday, published this week by Harper. © 2020 by N. Scott Momaday.

October 30, 2020

Staff Picks: Witches, Glitches, and Governesses

Anne Serre. Photo: ©Sophie Bassouls/Leemage and New Directions Publishing.

Anne Serre’s The Governesses (translated from the French by Mark Hutchinson) is like someone else’s feverish vision, something you shouldn’t be seeing. The tightly crafted prose keeps the hallucinatory qualities in check, and Serre’s coy delivery means nothing is easy to pin down. Monsieur and Madame Austeur hired the three young governesses to enliven their home, but they have since become more than employees; not quite like family, they are mysteriously unshakable fixtures in the domestic realm. So much about this fairy tale of voyeurism moves in strange ways, the plot unfolding in little discrete episodes: the governesses hunting strangers, entertaining suitors, planning a party, teasing the old man across the street. The whole thing has a sense of humor about it, though it’s hard to be sure whom the joke is on. There are no real conflicts, and while you could easily sink your teeth into the nuanced presentations of gender and sexuality, the smooth structure also gives you permission to delight in this eerie novella as much as it delights in itself. —Lauren Kane

I love a good spooky podcast. A couple of years ago, I was addicted to The Black Tapes, a sort of fictional cross between Serial and The X-Files. This year, I’ve started listening to Radio Rental, an anthology series from the creator of the true crime podcast Atlanta Monster. Radio Rental features Rainn Wilson as a man named Terry Carnation who owns a video rental store filled with a variety of mysterious tapes. (I’m sensing a theme in the world of scary podcasts.) Each tape features a real-life horror story or unsettling experience told by the person who lived it, culled from various internet forums. As a person who has spent a lot of time reading websites devoted to the paranormal, it’s fun to hear someone recount a tale I’ve already read on, say, the Glitch in the Matrix subreddit. Are these encounters real? Perhaps. If nothing else, Radio Rental offers an opportunity to experience digitally the old campfire favorite of telling ghost stories. And it wouldn’t be Halloween without a rewatch of “Anything Can Happen on Halloween,” as performed by Tim Curry in the bizarre 1986 adaptation of The Worst Witch, which my sister and I watched every single year of our childhoods. —Rhian Sasseen

Still from The Devil’s Backbone. Courtesy of the Criterion Collection.

In dire need of a spooky film for this week’s staff picks, I turned to Guillermo del Toro’s The Devil’s Backbone (currently streaming on the Criterion Channel), his first feature to tackle the horrors of the Spanish Civil War. Being a longtime fan of del Toro’s work, I came into this film expecting a traditional ghost story subverted, and I knew that just as he did in his masterpiece Pan’s Labyrinth, del Toro wouldn’t shy away from the brutality that stems from the scars of a civil war and the callous greed of fascism. But despite knowing what I was getting myself into, I was floored by the deftness with which The Devil’s Backbone weaves its plot. No image or symbol goes wasted. Even though the film takes place almost entirely in the middle of nowhere, it never forgets to demonstrate how the pressures of the Spanish Civil War haunt the country. When the question that lingers over the entire film—“What is a ghost?”—reappears at the very end, del Toro presents a number of answers. But the clearest answer in my mind, especially considering our current moment, is that history is a ghost. Its haunting isn’t necessarily good or bad but instead something we can learn from to avoid repeating the mistakes of the past. I hope we can let ourselves be afraid for the right reasons. Ghosts may be scary, but fascism is scarier. —Carlos Zayas-Pons

Helen Oyeyemi’s Gingerbread is fantastic in two senses: it is both a stunning achievement and a feat of fantasy. With an eye for strangeness and a skill for suspense, Oyeyemi has been called a modern Edgar Allan Poe, but her interest in fairy tales makes her work distinctly enchanting. And although Gingerbread is a take on “Hansel and Gretel,” it is not a mere reiteration of the familiar tale. The opening lines are almost a declaration of this: “Harriet Lee’s gingerbread is not comfort food. There’s no nostalgia baked into it, no hearkening back to innocent indulgences and jolly times at nursery.” Like the titular treat, Gingerbread is not an exercise in nostalgia; it feels more like a strange dream than a lilting story to send you off to bed. In the spooky spirit, I’ve spent the latter half of October sitting inside this novel. It is a dynamic, energetic read that demands your full participation: you must take its leaps and bounds yourself, feeling what the characters feel, seeing what they see, and experiencing everything as they do. What a delight, to almost smell the sweetness coming off the page. While ambitious and whimsical, the book remains grounded in its story of a mother and daughter who feel almost close enough to touch. Gingerbread is a masterful display of the fantastic, rooted in characters and themes that feel present and charming and real. —Langa Chinyoka

The Witch is a story about unmooring from authority, set amid the heavy skies, barren fields, and drab homespun of seventeenth-century New England. What could be spookier? A group of religious dissenters leaves the old country to live like apostles in the wilds of America. One man dissents from them and is banished from the settlement along with his wife and children. They creak off in an oxcart, tall hats swaying, and pursue the true Gospel from a dim thatch-roofed cabin at the edge of a very dark forest, into which an infant son disappears. Born into exile and thus unbaptized, he is presumed hellbound. Also missing: an heirloom silver cup, the last souvenir of home. Thomasin, the family’s teenage daughter, is blamed by her mother for both losses, and she spends much of the film trying to regain that parent’s favor—the only arbiter of goodness she has left, since England is practically papist, the elders in town are false, and she’s gone and called her father a hypocrite (thereby enacting a timeless teenage rite of passage). With hope of maternal approval fading, Thomasin finds herself alone in a lawless wilderness—which, as Mother well knows, is where the devil will tempt you. —Jane Breakell

Still from The Witch.

Cooking with Gabrielle Wittkop

Please join Valerie Stivers and Hank Zona for a virtual wine tasting on Friday, November 13, at 6 P.M. on The Paris Review’s Instagram account. For more details, or scroll down, or visit our events page.

Stuffing for a squab: pancetta, sage, and its own heart and liver. Photo: Erica MacLean.

On Halloween, when many people abandon themselves to the linked joys of sugar and horror, we more literary types decide to dine from transgressive fiction. I have at hand two books by the French writer Gabrielle Wittkop (1920–2002): Murder Most Serene (translated by Louise Rogers Lalaurie) and The Necrophiliac (translated by Don Bapst). The former, set in Venice between 1766 and 1797, is a murder mystery in which the wives of a nobleman named Alvise Lanzi keep dying from poison. Perhaps the killer is his mother, Ottavia, whose basement cellar for Nebbiolo wine also hides “flasks and phials”; or it could be her cicisbeo, who is also a spy; or the maid, Rosetta Lupi, in her “apron edged with lace”; or Alvise’s jilted lover Marcia Zolpan, a “fine-looking girl” with “a very short neck.” It could even be Alvise himself. The setting is one of grotesque, end-of-empire decadence. Elaborate feasts are the norm. The other book, The Necrophiliac, is the diary of a man in Paris who, as the title suggests, has sex with the dead. It might be the most disgusting and challenging book in the alternative canon. We cannot understand Wittkop without it, but fortunately, in the parts I could bring myself to read, there wasn’t any food.

Wittkop is an elusive and legendary figure in European letters, but her work has been slow to appear in English. Biographical information about her in this language is scarce. She was born in Nantes, France, in 1920; she married a Nazi deserter named Justus in Paris during the occupation and later moved with him to Germany. In her afterword to Wittkop’s Exemplary Departures, the translator Annette David describes Justus as a “German essayist” and reveals that he was gay. Both Justus and Gabrielle died by suicide—separately, seventeen years apart—when faced with terminal illnesses. Gabrielle Wittkop wrote travelogues, arts coverage for the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, and novels that were popular in France and Germany. She was influenced by E. T. A. Hoffman, Edgar Allan Poe, Marcel Proust, Miguel de Cervantes, and Joris-Karl Huysmans, though her first and foremost love was the Marquis de Sade. She must have seen horrors in occupied and postwar Paris, but we can only speculate on how they influenced her worldview. Her preoccupation with death began, she said, in childhood. The narrator of Murder Most Serene offers this justification: “Why this obstinate dwelling over a corpse’s pluck?… Simply because it is there inside us all, day and night.”

I used squid as a substitute for cuttlefish, a popular mollusk in Venice. Photo: Erica MacLean.

Transgressive writers tend to dwell on the connections between sex and death, beauty and decay, eroticism and horror. Wittkop is no exception. Her prose is stylized and exquisite no matter what she’s describing. A picnic lunch in Murder Most Serene begins, “Shelling her plate of slipper lobsters, Ottavia offers a wicked commentary in classical Greek on the filthy tales told her by an abbot, gorged like a sponge on the effluvia of the bathhouses.” Slipper lobsters (I googled them) are small, camel toe–looking crustaceans, now endangered but once a speciality of the Venetian lagoon. What is contained in “the effluvia of the bathhouses,” I can only imagine. The scene continues:

The party indulges in moleche, edible crabs that shed their shells when molting and are thrown alive into boiling oil. The party honors a Breganze Bianco with a fragrance of fresh hay and the color of buttercups … Mario Martinellei helps himself to more baby cuttlefish, and a Mezzetino cuts open the pate, which, disemboweled, spills forth its calf sweetbreads and kidneys in a thick vapor of entrails. Abandoning some chunk of half-nibbled carrion under a bush, green flies descend on the nectar. An Inferno of exceptional vintage, matured to the morbid sweetness of walnuts, accompanies buntings served with polenta, suckling lamb, and riso in cagnone. Reclining on one elbow, a Dottore declaims a sophism for public consumption, then whispers in the ear of a Colombina who lifts her mask to reveal the face of a very beautiful young man.

It’s a lot of fun.

Biscotti are referred to several times in Wittkop’s work. My favorite recipe uses vegetable oil and has a secret ingredient: self-rising flour. Photo: Erica MacLean.

The fun is maintained throughout the poisoning and death scenes. A woman on her descent toward eternity vomits “great lengths of silvery, acrid mucus.” An autopsy is performed. “Sawn open, the cranium is a casket like any other. The flesh is both flaccid and marmoreal, singularly compact and tight, like frozen fat.” A later wife goes out like this: “Each morning Rosetta administers a clyster to Teresa, who has always had a tendency to constipation. And though she suffers now from diarrhea the clysters are continued. On Sunday night, despite a high fever, she wishes to take her bath, and falls asleep in it. On Monday she is rather better, eats a lettuce soup and half a pigeon. That night she is gripped by a violent fever, vomits, and suffers alternate bouts of extreme cold and burning heat.” The careful description of symptoms runs on in this vein through the eighth day, when Teresa dies.

It’s baroque and wonderful, and I enjoy this vein of aestheticized gore—as many of us do, if we judge by our television programming—but I have never found transgression persuasive as theory. I comprehend the intellectual connection between sex and death, but on the daily, lived level where most of what matters takes place, the two experiences are pretty different—perhaps so different that they’re more meaningful when addressed as separate topics. Work like this also tends to claim that it will shock you out of your bourgeois preconceptions or, as Murder Most Serene’s introduction says of Wittkop’s novels, “invite us to jettison our moral baggage.” That seems incoherent in literary criticism, as it would be undesirable in life.

The pigeon that appears in Teresa’s death scene is probably a squab (young pigeon), like this one. Photo: Erica MacLean.

And then I read The Necrophiliac (the parts of it I could bear) and decided that perhaps I’d just never read anything transgressive enough. In The Necrophiliac, Wittkop pushes the glee of horror and the choice of aesthetics over morality to the extreme. The protagonist’s descriptions of his many loves—“my boyfriends with anuses glacial as mint, my exquisite mistresses with gray marble bellies”—are so taboo that they actually made me giddy. Here is the comparatively mild beginning of one of his more acceptable relationships:

I celebrate the New Year in good company, that of a concierge from rue de Vaugirard, dead of an embolism. (I often learn this sort of detail during the course of a burial.) This little old woman is certainly no beauty, but she is extremely pleasant, light to carry, silent and supple, agreeable despite her eyes that have fallen back into her head like those of a doll. Her dentures have been removed, which causes her cheeks to sink in, but when I strip off her awful nylon blouse, she surprises me with the breasts of a young woman: firm, silky, absolutely intact—her New Year’s gift.

A translation of anything from this book into reality would, of course, be an atrocity. Nor could there be a made-for-TV version. As art, it’s defensible as freedom of expression, though I suspect its publishers would have trouble if anyone were paying attention. Moreover, “we can say it, so we should” is a thin justification. Yet I find the book intellectually and artistically fascinating, and I’m glad it exists. For me, the redeeming element of The Necrophiliac is that through extraordinarily skilled and beautiful writing, humor, daring, and glee, Wittkop seizes life from the jaws of death, pleasure from horror, and transforms her material into art. It couldn’t be done without her technical mastery, but she has done it, and it’s a kind of triumph.

Reading Murder Most Serene, I thought often of the human suffering Wittkop surely must have seen in Paris during and after World War II. How could anyone who lived through that possibly make light of death? It’s pure speculation, but after reading The Necrophiliac, I wonder if such work came about not despite but because of what she saw. Sometimes we appropriate horror to transform it, re-create things in our own words to make them safe, role-play trauma to rewrite it. Even Halloween has something of that spirit.

Lettuce soup is basically broth and lettuce blitzed with an immersion blender. Photo: Erica MacLean.

Thus inspired, I channeled the books’ sense of daring, thrills, decadence, and transgression when choosing my menu. I made the lettuce soup from the death scene in Murder Most Serene, mostly because “lettuce soup” sounded disgusting and I wanted to know if it could possibly be good. (No.) I researched all the items from the picnic scene above and discovered that cuttlefish are another lagoon speciality, buntings are ortolans, and riso in cagnone is a rice with cheese, similar to risotto. Cuttlefish were unavailable, so I opted for squid, a near cousin, and planned to clean it, remove the beak and bones, and stew it in its own ink. This was a challenge and thrill because I’m slightly squeamish when it comes to instructions like “make a firm cut directly beneath the eyeballs” and “sort through the innards to find the ink sac.”

Ortolans are a protected species, so I substituted a different little bird to top my polenta—the pigeon from the death scene (squab, very pricey at $25 a head from D’Artagnan). Following a Marcella Hazan recipe, I stuffed the squab with sage, pancetta, and its own heart and liver. Lastly, because there was a specific instruction to dip biscotti in the “warm, heavy amber of Tuscan Vino Santo,” I made biscotti with the Italian flavorings of almond and blood orange. Biscotti recipes vary widely; mine is from an Egyptian cookbook, and I consider it to make perfect, foolproof, not-too-sweet, crunchy cookies, something I’ve been waiting to share.

Wine makes many appearances in Wittkop’s prose, as when “women gorged with venom burst like wineskins.” Photo: Erica MacLean.

Wittkop was nearly as lavish with her descriptions of wine as she was with food and gore. Her references are period-authentic, too, according to my spirits collaborator, Hank Zona, and reflect the politics of the time. The “Inferno” wine mentioned in the picnic scene above comes from a subregion of the northernmost wine producing region in Italy, Valtellina, which in the late eighteenth century was still a part of the Venetian Empire. It is called Inferno because the job of growing its grapes on nearly vertical terraced vineyards is hellish. Inferno, made from Nebbiolo grapes, was the precise wine suggested by Wittkop to go with my squab-and-polenta dish, and its acidic bite and aroma of roses provided a needed counterbalance to the bird’s rich, livery flesh.

Later in the same scene, Wittkop mentions that “everyone holds to the ruby red Valpantena.” That’s a wine from a subregion of the larger region of Valpolicella, Zona explained. From a favorite biodynamic winemaker in Valpolicella, he suggested a light red that he thought would go well with my squid. This pairing was the surprise standout of the meal. The fresh squid was sweeter and more tender than any I’ve tasted, and the rich, unctuous black sauce, flavored with tomato paste and garlic, was magical with the acid and black-fruit flavor profile of the wine. Ideally, you eat this dish as a stew on day one, then toss the leftovers over pasta on day two.

Breaking down my own squid is something I’ll do again. There’s no comparison for freshness and flavor. Photo: Erica MacLean.

The squid success was all the more satisfying because I’d had some trepidation about cleaning it and getting the ink. In the end, the cleaning (and skinning and debeaking!) process was pretty easy, though I did have some misadventures with the ink sacs. The squid I bought in Chinatown during a trial run had sacs, but they seemed dried out by the time I tried to use them. The farmers market squid pictured in the photographs came whole and uncleaned, but both sacs were broken or empty. I ended up using canned cuttlefish ink as a backup, though I’ve read that it’s a faint imitation of the real thing. Overall, in fact, freshness is preferred with squid. The dish I loved on the day of the photo shoot made for some creepy, inky-black, tentacle-laden leftovers for the next day’s lunch. My slight revulsion felt appropriate to Wittkop, but the meal was even more unappealing after I warmed it up in the microwave.

Unlike her heroines, though, I’ll live and learn.

Photo: Erica MacLean.

Lettuce Soup

Adapted from Leite’s Culinaria .

2 tbs butter

an onion, chopped

a medium potato, peeled and chopped

4 cups chicken or vegetable stock

salt and pepper (to taste)

a head of Bibb, Boston, or butter lettuce (5 cups)

1 cup fresh herbs (I used 3/4 parsley and 1/4 lovage)

fresh sunflowers or other cute shoots (for garnish)

Photo: Erica MacLean.

Melt the butter. Add the onion, and sauté until glossy and translucent, around ten minutes. Stir in the potato, then cover and cook on medium-low for ten minutes, stirring from time to time so it doesn’t stick.

Add the stock, and season with salt and pepper. Bring to a boil, cover, and gently simmer until the potato is tender, about fifteen minutes. Add the lettuce and herbs to the pan, and cook until the lettuce has just wilted. Turn off the heat, and let cool slightly. Puree with an immersion blender.

Photo: Erica MacLean.

Squid Cooked like Venetian Cuttlefish over Pasta

Adapted from Tina’s Table .

2 lbs uncleaned, 1 lb cleaned squid

olive oil

three cloves garlic (ideally black garlic, if you can find it)

1/2 cup white onion, chopped

1 tsp squid or cuttlefish ink (just in case)

3/4 cup white wine

1/2 tsp chicken Better Than Bouillon

1 tbs tomato paste

salt and pepper (to taste)

1 lb spaghetti, cooked and drained

1/4 cup parsley, finely chopped

Photo: Erica MacLean.

Clean and slice your squid following the method of your favorite online tutorial, reserving the ink sacs. (I especially enjoyed the soothing voice of the man on this one.)

In a medium saucepan, sauté the garlic and onion in a glug of olive oil for about three minutes until the onion is just translucent, then add the squid, and toss to combine. Add the squid ink (mash the sacs up with a spoon first if you’re using fresh ones; use about a teaspoon if you’ve opted for the canned variety). Toss to combine. Add the wine, bouillon, and tomato paste, and stir. Add more wine if you think you need more to cover the squid. Cover, turn the heat to medium-low, and cook at a simmer for twenty-five to forty minutes, checking regularly, until the squid is soft. Season to taste with salt and pepper. Toss with pasta and parsley to serve.

Photo: Erica MacLean.

Pot-Roasted Squab with Polenta

Squab adapted from The Classic Italian Cookbook, by Marcella Hazan. Polenta adapted from How to Eat a Peach, by Diana Henry.

For the squab:

a squab

6 sage leaves

a strip of pancetta

salt and pepper (to taste)

1 tbs butter

1 tbs vegetable oil

1/2 cup white wine

For the polenta:

1/2 cup whole milk

1 cup water

1/2 tsp salt

scant 1/2 cup coarse cornmeal

2 tbs unsalted butter

3 tbs Parmesan cheese

Photo: Erica MacLean.

To make the squab, remove all the organs from the inside of the bird. Reserve the liver and heart, but discard the gizzard. Wash the squab in cold running water, and pat dry thoroughly inside and out. Stuff the cavity of the bird with two sage leaves, a strip of pancetta, the heart, and the liver. Season the outside of the bird liberally on all sides with salt and pepper.

In a pot just large enough to hold the squab, heat the butter and oil over medium-high heat. When the butter foam subsides, add the remaining sage leaves and then the squab. Brown the squab evenly on all sides. Add the wine. Turn the heat up to high, allowing the wine to boil briskly for thirty to forty seconds. While the wine is bubbling, turn and baste the squab, then lower the heat to medium-low and cover the pot. Turn the bird every fifteen minutes. It should be tender and done in an hour.

Transfer the squab to a warm dish. If you’re serving half a bird per person, halve it with a knife or poultry shears. Tip the pan and draw off most of the cooking fat with a spoon. Add two tablespoons of warm water, turn the heat to high, and scrape up any loose cooking residue in the pan while the water evaporates. To serve, place the squab on a bed of polenta, and drizzle with the sauce.

Photo: Erica MacLean.

To make the polenta, put the milk in a large, heavy-based pan with the water and half a teaspoon of sea-salt flakes. Bring to a boil. Add the polenta, letting it run in thin streams through your fingers, whisking continuously. Stir for two minutes until it thickens.

Reduce the heat to your lowest setting and cook, mostly covered, for forty minutes, stirring every four to five minutes to prevent the polenta from sticking. When it’s done, it should be coming away from the sides of the pan. You might need to add more water; it shouldn’t get dry and stiff but should be thick and unctuous. Stir in the butter and Parmesan, tasting for seasoning.

Photo: Erica MacLean.

Blood Orange Biscotti with Almonds

Adapted from The Taste of Egypt , by Dyna Eldaief.

3 eggs

1/4 tsp vanilla

1/2 cup sugar

1 tsp blood orange zest

3/8 cup vegetable oil, plus extra for greasing

1 1/2 cup flour

1 1/2 cup self-rising flour

1/4 tsp baking powder

1/2 tsp cinnamon

1/4 cup milk

1/2 cup candied blood orange peel, chopped

1 cup slivered almonds, toasted

Photo: Erica MacLean.

Preheat the oven to 325. Place the eggs and vanilla in a large bowl, and beat together. Add the sugar, blood orange zest, and oil, and beat until well combined. Sift the flours, cinnamon, and baking powder together. Add the milk to the egg mixture, then add the flour slowly, stirring until still lumpy and just combined. Use only as much flour as required to make the dough just come together.

Lightly grease a baking tray with oil, and use a spoon to place two rectangular logs of dough, about three inches wide and an inch high, on the tray. Transfer to the oven, and bake for fifteen to twenty minutes, then remove. Cut the half-baked cookies into half-inch slices and place them on a baking tray lying on their sides. Reduce the oven temperature to 300, and bake for a further fifteen minutes. Turn off the oven, but leave the cookies in the oven to dry.

Photo: Erica MacLean.

Wine!

Please join Valerie Stivers and Hank Zona on Friday, November 13, at 6 P.M. for a virtual literary wine tasting on The Paris Review’s Instagram account. We will be discussing the many wines mentioned in Wittkop’s work and how to pair them with food.

The wines seen in the story are Musella Valpolicella Superiore 2017, Nino Negri Inferno Valtellina Superiore 2017, and Felsina Vin Santo del Chianti Classico 2008. We encourage participants to source their own bottle and taste with us. Valpolicellas should be available in any good wine store; the designation “superiore” represents a higher quality. Particular bottles from the Musella biodynamic winery are available at some stores in Brooklyn and Manhattan. To find a bottle similar to the Nino Negri Inferno, ask for a Nebbiolo from Lombardy or Piedmont, which should also be widely available. But first check if the store has an Inferno—it might. Vin Santo is a dessert wine and is more expensive at $30 to $50 a bottle, but it’s carried in all quality stores. Felsina is an excellent maker of Vin Santo at a mid-range price.

Anyone who would like more specific advice on how to find these wines near them can email us (hank@thegrapesunwrapped.com).

Photo: Erica MacLean.

Valerie Stivers is a writer based in New York. Read earlier installments of Eat Your Words .

October 29, 2020

How Horror Transformed Comics

The History of EC Comics tells the story of one of the most infamous and influential forces in twentieth-century American pop culture. Founded in 1944, EC Comics quickly rose to prominence by serving up sharp, colorful, irresistible stories that filled an entire bingo card of genres, including romance, suspense, westerns, pirate tales, science fiction, adventure, and more. Perhaps most crucial to the company’s success, however, was its pivot to horror. In the following excerpt, Grant Geissman chronicles the origins of such gruesome, bone-chilling series as Tales from the Crypt and explores how the relationship between two key figures—the artist, writer, and editor Al Feldstein and the company’s publisher, Bill Gaines—acted as an engine that propelled EC Comics to the forefront of the industry.

Detail from the cover of Three Dimensional Tales from the Crypt of Terror No. 2, Spring 1954. Art by Al Feldstein. Copyright: TM & © William M. Gaines Agent, Inc.

With Bill Gaines and Al Feldstein both working and hanging out together, Feldstein had the boss’s ear. On their car rides to and from the office, Feldstein began to chide Gaines for playing follow-the-leader. “You’re taking Saddle Justice and turning it into Saddle Romances because Simon and Kirby came out with a romance book and it’s doing well,” the ever-ambitious Feldstein said to Gaines. “We’re gonna follow them and get clobbered when it collapses, just like the teenage books collapsed. Why don’t we make them follow us? Let’s start our own trend.”

Gaines and Feldstein had talked about the old radio dramas they had loved as kids, shows like Inner Sanctum, The Witch’s Tale, and Arch Oboler’s Lights Out. Inner Sanctum and The Witch’s Tale both featured hosts who introduced the tales—the former by “Raymond,” a spookily sardonic punster, and the latter by “Old Nancy,” a cackling witch. Feldstein recalled that as a kid he used to climb down the stairs to sneak a listen, and was happily terrified by them. Gaines had similar recollections. Feldstein kept pushing for that, and Gaines finally said, “Okay, we’ll try it.” This was, in fact, a somewhat similar concept to the one the artist Shelly Moldoff had pitched on the aborted Tales of the Supernatural comic. Gaines was apparently mum about the situation with Moldoff, and Feldstein later said that he knew nothing about it at the time.

An untrimmed press proof of Johnny Craig’s cover to Crime SuspenStories No. 3 (February–March 1951). Copyright: TM & © William M. Gaines Agent, Inc.

So with the December 1949–January 1950 issues of Crime Patrol (no. 15) and War against Crime! (no. 10), EC introduced what was billed on the covers as “an Illustrated Terror-Tale from the Crypt of Terror!” and “an Illustrated Terror-Tale from the Vault of Horror!” Feldstein wrote and illustrated both stories.

The story from the Crypt of Terror was hosted by The Crypt-Keeper, and the story from the Vault of Horror was hosted by The Vault-Keeper, both inspired by the hosts from the old radio shows. Hedging the bet, “The Crypt of Terror” appeared in the last position in Crime Patrol. (However, “The Vault of Horror” story occupied the first slot in War against Crime!) The covers of both comic books were done by Johnny Craig, who had done all of the previous covers for both titles.

Johnny Craig’s Christmas cover of The Vault of Horror No. 35, February– March 1954. Copyright: TM & © William M. Gaines Agent, Inc.

Gaines liked the experiment well enough, because the next issues of both books (Crime Patrol no. 16 and War against Crime! no. 11, both February–March 1950) contained further installments, with the stories in the same positions as before. Craig again contributed the cover art for both books.

Gaines and Feldstein liked doing these stories, and it did seem like they were onto something. Back then the wholesalers employed “road men,” guys who checked the newsstands to see how things were selling. When they sent back the “ten-day check-ups” indicating strong sales for the experimental issues of Crime Patrol and War against Crime!, Gaines and Feldstein went all in for horror. And a New Trend was ushered in at EC.

Bill Gaines and Al Feldstein in the EC office in late 1950, with a rack of their latest comic books. Copyright: TM & © William M. Gaines Agent, Inc.

With the seventeenth issue they changed Crime Patrol to The Crypt of Terror, and with the twelfth issue they changed War against Crime! to The Vault of Horror. Both comics were April–May 1950. A month later they changed Gunfighter to The Haunt of Fear. (They changed the title of The Crypt of Terror to Tales from the Crypt three issues later, after “the wholesalers made some noise,” according to Gaines.) All three books continued the numbering from the previous titles, Gaines’s usual ploy to avoid paying the fee for a second-class mailing permit on a new title. (He got away with this on the first two titles, but on The Haunt of Fear they had to change the numbering, starting with the fourth issue, and pay for a new permit.)

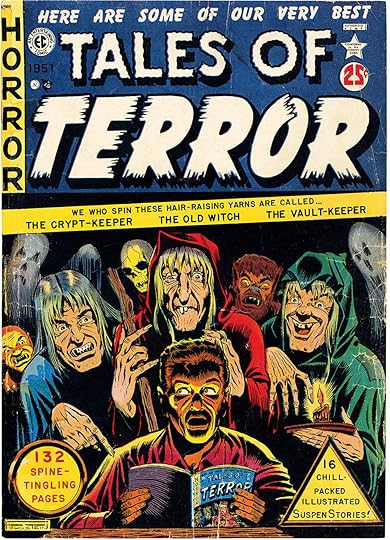

With the second issue of The Haunt of Fear (no. 16, July–August 1950), Gaines and Feldstein also added a third horror host, The Old Witch, and the unholy trio of hosts was complete. The Three GhouLunatics—as the three horror hosts came to be called—would appear at the beginning and end of each story and offer up punny, smart-alecky commentary. EC’s new horror comics were pretty much an instant hit with readers, and Gaines, Feldstein, and Craig all shared that enthusiasm. EC’s business manager, Frank D. Lee, was not as enthused. When asked how he liked a new cover or story, Lee responded, “I don’t like it.” Feldstein said that Lee was “pretty grumpy” about EC’s new comics and openly expressed his dislike for them. Lee wasn’t the only naysayer. Sol Cohen, who had been advising Gaines, declared “the ship is sinking,” and bailed sometime in 1949 for a position as a comic book editor at Avon.

Detail from the cover to The Vault of Horror No. 18, April–May 1951. Art by Johnny Craig. Copyright: TM & © William M. Gaines Agent, Inc.

Johnny Craig illustrated the covers for the first several issues of all three of the horror titles, and also illustrated the cover of every subsequent issue of The Vault of Horror. A fine—but very slow—craftsman, Craig told Roger Hill: “I was supposed to do three stories a month. I was lucky if I did one.”

Playing with the “A New Trend” blurbs on the covers of EC’s new comics, collectors began to refer to the comics published before that as “Pre-Trend” comics, and the term stuck. Not all that many Pre-Trend artists managed to jump into the New Trend. Graham Ingels continued to work on the company’s “love books,” but he soon turned out to be the quintessential horror artist. Bill Gaines said: “In the early days of EC we had Graham typecast into the western books, and when we started the love books we used him there for a few stories, but he didn’t seem to fit. When we started the horror titles, we didn’t use Graham because we thought he’d be good at it, we used him because whenever an artist came into the fold we had to use him for something. So we stuck him in the horror books, and it didn’t take us very long to realize what had happened—that Graham Ingels was ‘Mr. Horror’ himself.” Gaines and Feldstein started calling him “Ghastly Graham Ingels” in the letter columns in 1950, and the name stuck. Ingels started signing his work with the pen name “Ghastly,” and began specializing in what Bill Gaines’s biographer, Frank Jacobs, once famously referred to as “cadaverous inkings.” Ingels’s horror tableaux are fetid, swampy, decaying, and oozing, and when depicting a rotting, shambling corpse, he was second to none. As the horror comics developed, Ingels also became known for his interpretation of the grinning visage of The Old Witch.

Tales from the Crypt No. 28, February–March 1952. TM & © William M. Gaines Agent, Inc.

Feldstein wrote (and drew) all of his earliest EC horror stories on his own, and the rest of the stories in the early horror comics came from outside scriptwriters like Gardner Fox and Ivan Klapper. Within a very short time Gaines started bringing in snippets of ideas to be fleshed out into complete stories. At the time, the perpetually chubby Gaines was taking a prescription appetite suppressant that contained Dexedrine, which affected his sleep. Gaines would stay up half the night reading pulps and collections of horror and science-fiction stories. He scribbled plot ideas on scraps of paper he called springboards, and brought them to Feldstein the next morning. (Gaines also worked with Johnny Craig on stories in a similar fashion.)

It was a frantic schedule. Four days a week, Gaines and Feldstein hammered out plot ideas from Gaines’s springboards, with Feldstein always mindful of which artist they were plotting the story for that day. If Feldstein didn’t think a particular plot could be made into a script that would fit a particular artist’s style, he would pass on it, and Gaines would have to pitch another idea. Gaines said: “Al and I would sit down, and I would have to sell Al on one of my springboards. That’s what it amounted to. After he had rejected the first thirty-three on general principles, he might show a little interest in number thirty-four. I’d then give him the hard sell and he’d get going. He’d run into the next room and start working out the plot.” Although many of these springboards were inspired by existing stories, the duo invariably changed and improved upon the plots, in some cases making a far better yarn than was told in the original source.

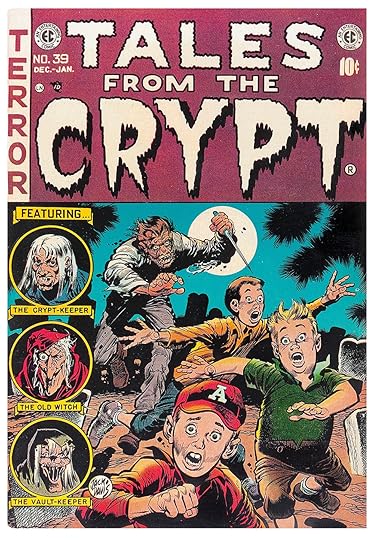

The cover of Tales from the Crypt No. 39. December 1953–January 1954. Copyright: TM & © William M. Gaines Agent, Inc.

Once they had set a plot, the two might work on some “fill,” fleshing out the plot a bit further. By then, it would usually be lunch time, and Gaines and Feldstein (and often Craig, along with any artists who might be in the office picking up or dropping off a job) would go to lunch at a nearby Italian place called Patrissy’s, where, Feldstein recalled, “we all got fat. They had great Italian food.” After lunch, Gaines would do paperwork and so forth, and Feldstein would write the actual story. (There was never a typed script; Feldstein would write the stories directly onto the art boards.) Gaines often had a nervous stomach at this point, because “I never knew if and when Al would come bursting back in and say ‘I can’t write that Goddamn plot!’ ” Then the pair would have to start the process all over again, because, said Gaines, “we must have a story by five o’clock.”

The horror stories Feldstein and Gaines came up with were all designed to have twisty, O. Henry–type endings, with the protagonist virtually always exacting a well-deserved measure of poetic justice against the antagonist, even if the protagonist had to somehow return as one of the walking dead to exact his revenge. This was Old Testament, an-eye-for-an-eye–style retribution, with the irony being that Gaines was an atheist. The EC horror stories were gory and many went way over the top, but this was fantasy, remember. Gaines said: “The old EC stories were largely sick humor. Almost every one of those horror stories was tongue-in-cheek. That stuff was strictly fantasy, and in the field of fantasy I’ll go as sick as you want. But if I see real blood, I’ll faint.”

The cover of one of the three issues of the Tales of Terror annuals, issued in 1951. Cover art by Al Feldstein. Copyright: TM & © William M. Gaines Agent, Inc.

Grant Geissman is one of the world’s leading experts on EC Comics and Mad magazine, and the author and designer of four books on the subject. He is also an Emmy-nominated guitarist and composer who cowrote the music for the hit television series Two and a Half Men and Mike & Molly.

Excerpted from The History of EC Comics . Text copyright © 2020 by Grant Geissman. Published by TASCHEN.

The Corporate Feminism of NXIVM

Like everyone on Twitter, I have been transfixed by the HBO documentary series The Vow, about the self-improvement cult/pyramid scheme/sex trafficking ring known collectively as NXIVM. The organization’s leader, Keith Raniere, was found guilty on seven counts of racketeering and sex trafficking in 2019, and this week, on October 27, he was sentenced to a hundred and twenty years in prison. The most sensational headlines of the case are about the former teen actress Allison Mack’s involvement in a secret sadomasochistic group within NXIVM known as DOS (“dominus obsequious sororum,” a phrase in a language that could at best be described as Latin-esque that supposedly meant “lord over the obedient female companions”) in which she and other “masters” recruited other women as “slaves,” some of whom were made to have sex with Raniere. Grotesque details abound in this story, particularly of slaves being branded with a soldering iron near their crotches with a symbol containing both Mack’s and Raniere’s initials.

The Vow follows former high-ranking members within NXIVM as they leave the group. It also attempts to answer why anyone would be caught up in something so heinous, what the filmmakers call the love affair before the betrayal. I suppose that’s why the first episode seems oddly positive in its depiction of Executive Success Programs (ESP), the personal growth seminars that were most people’s entrees to NXIVM. Former members talk about being amazed by the “technology” that Raniere had invented to help them overcome their fears and limiting beliefs, and how happy they were to have found such a welcoming, understanding community.

This technology, in reality, is nothing more than a proprietary blend of therapeutic methods cribbed from cognitive behavioral therapy, Scientology, Ayn Rand’s theory of objectivism, multilevel marketing sales techniques, and, most notably, neurolinguistic programming (NLP), which NXIVM’s cofounder, Nancy Salzman, was practicing when she met Raniere in 1998. NLP, a kind of hypnotherapy, has been derided as pseudoscience, and of course none of Raniere’s methods were, as he often bragged, “mathematically reproducible.” What is more telling is his reliance on Salzman to form the basis of his self-improvement regime. Members said Salzman “downloaded” information from Raniere in order to create ESP’s educational modules. If this is true, she seems to have extrapolated liberally from Raniere’s ideas in her creation of a practical curriculum. Unlike L. Ron Hubbard, the founder of Scientology, Raniere has never written a NXIVM scripture or treatise or even workbook; he didn’t teach or manage money or answer emails. There were women for that.

In The Vow, Raniere appears as the laziest and least charismatic cult leader of all time. “What this show teaches me,” I told my husband midway through the first episode, “is that anyone can start a cult.” Raniere slept all day and spent all night either going on long walks or playing in the midnight NXIVM volleyball games he insisted on. He exercised control through the myth he created of himself, based on lies or half truths: he was the smartest man alive, with a 240 IQ, had taught himself calculus at the age of twelve, was a judo champion and a concert pianist. He had his acolytes disseminate this information about him to every recruit, so in person he could appear humble.

To the naked eye he seems remarkably stupid—the only books I can find plausible evidence that he has read are Atlas Shrugged and How to Win at Gambling, the latter of which he’s seen reading in a widely published and very weird picture, lying on a bed in his underwear. For years members of NXIVM videotaped, recorded, and transcribed everything he said, writing their own Gospel of Keith, but the philosophy we hear him drone on about in The Vow is full of anodyne platitudes, some of which seem to actually be taken from Hallmark cards. In one episode, a former girlfriend shows a card he once gave her for her birthday. “Dance like nobody’s watching. Sing like no one can hear you,” it says, perhaps the most overused inspirational cliché there is. “I think of you every time I read this,” Raniere wrote, with all sincerity.

What Raniere knew was mostly how to sell, having learned persuasion techniques as an Amway salesman in the eighties, and he pitched his contradictory, Randian idea of ethics to just the right people. (It is hard not to put scare quotes around ethics, just as it is hard not to put them around basically every word that Raniere twisted for his own purposes.) Since it was devised as an executive coaching program, riding a trend for such services in the late nineties, the ESP curriculum teaches its members that personal business success is the only thing that can create a happier, more peaceful world. “I pledge to ethically control as much of the money, wealth, and resources of the world as possible within my success plan,” members recited in their twelve-point mission statement. This was appealing to the organization’s entertainment industry recruits, who were often desperate for a formula for professional success, even as they said they came looking for personal fulfillment and a way to change the world. “I had some idea that I would become a famous actor and use my celebrity to help people,” says Sarah Edmondson, one of the former NXIVM executives featured in The Vow, echoing the wishful thinking of many people who were drawn to NXIVM. Theirs was a well-meaning selfishness that was validated by Raniere’s me-first humanitarianism.

This was even truer for the one-percenters who went through ESP. Sara and Clare Bronfman, the heiresses to the Seagram’s liquor fortune, bankrolled NXIVM for twenty years to a comically lavish degree: buying the organization a private jet, funding litigation against ex-members, covering sixty-five million dollars Raniere lost in the commodities market, buying an island in Fiji to use for retreats, and pulling strings with massive donations to convince the Dalai Lama to visit Albany in 2009. It seems that the most profound teaching Clare Bronfman gained from ESP was that her masses of wealth were not something to be ashamed of. “I thought that money made people bad,” Clare told Vanessa Grigoriadis in the New York Times magazine in 2018. “Money’s money. And people are people. So rich people can do good and bad, poor people can do good and bad.”

Raniere and NXIVM exercised a unique hold on its super-wealthy members by offering them teachings that were a mix of what they wanted to believe and what they most feared. Your money is a good thing, they were told, but you are blowing your chance to use it to help people. The only way they could do that, of course, was to give as much of it as possible to NXIVM. If you look closely, these ideas about privilege and complacency are laced through all of NXIVM’s teachings, including the way that women were recruited for DOS. As time went on, Raniere’s teachings became more misogynist, particularly in NXIVM’s women’s retreat, Jness, that started in 2006. There Raniere taught that women were naturally emotional, where men were rational; this difference made women dishonest, disloyal, unreliable, and lazy. Echoing sexists since Aristotle and before, Raniere continued to have zero original ideas. The other fundamental difference was that women were protected their whole lives, never facing humiliation or discomfort, thus making them rely on men instead of themselves. In this way, as Raniere and his lieutenants sought to break their female students with a form of tough love, they could claim they were doing it for the women’s own empowerment.

This reasoning is obviously completely false: humiliation is arguably a fact of life for women far more than it is for men, not least because our bodies are considered public property for anyone to ogle, touch, or comment on. But this story of a sheltered upbringing is true for some women, and I can imagine that for the child actors and heiresses in NXIVM, when Raniere derided women as “spoiled princesses,” it felt personal. “Coming from a family where I’ve never had to earn anything before in my life, [it] was a very, very moving experience,” Sara Bronfman said of being promoted in NXIVM in Forbes in 2003. “It was the first thing that I had earned on just my merits.” (Although Clare Bronfman has never disavowed Raniere, even after the revelations about DOS and her own conviction on crimes relating to NXIVM, there is no evidence the Bronfmans were involved with DOS.)

This is one answer to the question that plagues the conversation around DOS and NXIVM: how were over a hundred women convinced to join a secret organization where from the beginning they were called slaves, forced to collateralize their commitment with naked photos and secret confessions, and vowed loyalty to their masters for life? One answer is that many of these women had already internalized the belief that they were weak and spoiled, with no ability to work for anything. Their indoctrination at the Jness retreat would only have reinforced these beliefs. DOS was described as a “badass bitch boot camp” that would steel their commitments and help them achieve their goals, but more than that, they were told it was the only way they could help the cause of women, preventing nightmares like the election of Donald Trump from ever happening again. Yes, that’s right. This brutal sex cult, where young women were dogged by their masters to stay on starvation diets so they’d be more attractive to Raniere, was pitched as a sort of Pantsuit Nation, a secret group advancing the cause of feminism.

*

Raniere’s most persuasive evidence that his goal with NXIVM was to empower women, despite the despicably misogynist sentiments that came out of his mouth, were the women who ran every aspect of his business, from his cofounder, Nancy Salzman, on down. These women helped to sanitize his message and explain away misgivings students might have had, while also acting as his enforcers, particularly as the Bronfmans pursued legal vendettas against ex-members. It is significant that women recruited other women for DOS, since it would probably have been a much less appealing prospect had Raniere himself posed it to them. The women high up in NXIVM could make legitimate claims on empowerment, although they paid a high price for it: Raniere’s five codefendants, all of whom pled guilty rather than stand trial with him, were women.

Raniere’s female deputies were caught in the same bind as his hero, the author Ayn Rand. In her view, in order for women to be totally free, they had to devalue traditionally feminine work, communication, and ways of knowing, subjecting themselves to the punishing dominion of logic and ambition. As Sam Anderson wrote of Rand in New York Magazine in 2009, Rand saw herself as “a machine of pure reason, a free-market Spock” who claimed “that she could rationally explain every emotion she’d ever had.” This triumph of stereotypically masculine values seems to be linked directly with the emphasis both NXIVM and Rand put on the righteousness of achieving success within the capitalist system. If you believe that time is money, and money is necessary for doing good in the world, then it follows that emotions, instincts, and physical needs would be subordinated to a numb efficiency and all-consuming self-discipline and self-denial.

In this way, NXIVM was a distillation of all the failures and lies of corporate feminism. Often exemplified by Facebook CEO Sheryl Sandberg’s book Lean In, corporate feminism emphasizes the ingenuity required for an individual woman’s success in the workplace, instead of questioning the systemic barriers to women’s economic advancement and the unchecked nature of corporate power. One of the key aspects of the NXIVM story is how the right hand didn’t know what the left was doing when it came to the interlocking web of businesses that made up the NXIVM consortium, which was comprised of numerous companies including an acting studio and experimental preschool. This was for legal reasons, to ensure Raniere would be able to continue his work even if authorities shut down one of the organization’s branches. But it was also his way of hiding his worst abuses and beta-testing fringier ideas. He took a more overtly apocalyptic tone with his outreach in Mexico, where students were taught, according to the New York Times, “that Mr. Raniere had developed a sophisticated mathematical formula to predict that the world would end within 15 years.” When Salzman said at the first Jness retreat in 2006 that women were naturally monogamous while men were naturally polygamous, Susan Dones, who was at the time the head of NXIVM’s Seattle center, said she recognized that “they were introducing the idea of polygamy, but with a soft sell, laying the groundwork.”

In addition to the secrecy and confusion built into its arcane corporate structure, surely the self-interest the group preached kept members from asking questions about the way the organization was run. People who were trained to focus monomaniacally on their goals had little time to question the ethical pitfalls of pyramid selling, the organization’s regressive views of gender, and the exploitation of women Raniere was committing before their eyes. Salzman, Raniere’s closest deputy and collaborator, reportedly had no idea about DOS, even though her own daughter was one of Raniere’s first-line masters, as federal prosecutors described them in court. This blindness predictably had disastrous consequences for the organization’s most vulnerable targets. Some of Raniere’s trial’s most horrifying details came from the testimony of an anonymous Mexican member called Daniela, who moved to Albany when she was sixteen to work with NXIVM. She started having sex with Raniere when she was eighteen and facilitated Raniere’s sexual relationship with her underage sister, whom he called “the virgin Camilla.” At one point, Raniere convinced Daniela and her older sister, who was also sleeping with Raniere, to go to bed with him at the same time. Later, Raniere had Daniela’s parents confine her to her room for two years for what he called “an ethical breach”: her admission that she was attracted to a man other than him. All of this abuse was compounded by the fact that Raniere had helped Daniela enter the country illegally. “I was without a doubt a captive from a moment I was illegal in the country,” she said at trial.

It is no surprise that NXIVM’s Mexican members received its most extreme teachings and bore its most egregious violence. In all of the frenzied reporting on Mack’s involvement with DOS, many have missed that five of the eight first-line masters in DOS were Mexican. Despite the wealth of the Mexican contingent’s most high-profile members, which included the children of two Mexican presidents and the daughter of Mexico’s most powerful newspaper publisher, white supremacy and American chauvinism meant they had a subordinate position in the NXIVM power structure. All of this is intimately linked to the perverted corporate feminism the group preached, which held that the success of elite women would trickle down to more marginalized women, all the while ensuring that the opposite was true. Corporate feminism is one brand of white feminism, and they are both the close confreres of postfeminism, an enfeebled feminist marketing that gained ascendance in the nineties by emphasizing consumer freedom, lifestyle choice—especially the choice to conform to traditional gender norms—and success for women within a capitalist framework. It was in no way interested in the intersection of oppression, systemic change, or class critique, and was in fact designed to defang feminism as a radical political movement, distracting women with the attractive lie that what the feminist cause needed was more women making lots and lots of money and doing whatever the hell they wanted.

*

This is the way I’ve come to see the NXIVM story: as one of the horsemen of the broader postfeminist apocalypse, a sign of how far degraded feminist rhetoric has become. DOS was, for one thing, the horror-movie version of a multilevel marketing company, or MLMs, which have received more attention in recent years on social media, YouTube, and podcasts as fraudulent get-rich-quick schemes specifically targeting women. (I can picture the Blumhouse B movie about Tupperware sex parties now.) MLMs use individual salespeople to sell makeup, leggings, essential oils, and a million other consumer products directly to their friends and family for a small commission. The real money is not in selling but recruiting other salespeople who stand below you on the pyramid and will attract other recruits, all of whom will owe you commission. Raniere ran his first illegal pyramid scheme in the early nineties through his first MLM, Consumer’s Byline, and signed a consent order with the attorney general of New York to never run another multilevel marketing company. He broke this order almost immediately, starting an MLM called Innovative Network where members received discounts on “top-grade health products,” and, shortly after, in 1998, starting Executive Success Programs, where in order to move up the ranks, members had to aggressively recruit other students to take the ESP intensives, which were by invitation only. All of NXIVM’s programs were extortionately expensive, with five-day intensives costing between $2,000 and $10,000, and students were pressured constantly to re-up, often going deep into debt. The only exception to this was DOS, which was, at least on the face of it, free—members could join for the low, low cost of naked pictures and a lifetime vow of submission. But they were still expected to recruit their own slaves, preferably women who were young, thin, and single.

Raniere knew what he was doing when he used the MLM model for every venture he ever undertook, even enlisting a harem of sex slaves. Considering his beliefs about women, who could be surprised that he was drawn to an industry that targeted women’s vulnerabilities and subordinated them to the imperial apex of the pyramid scheme (him)? At least ninety-nine percent of MLM sellers lose money, but these companies still recruit with the promise that prospective salespeople can grow their own business in their spare time. This sales pitch is particularly attractive to women who have trouble working otherwise, often because they are taking care of children, and takes advantage of the kinship networks women build of friends, neighbors, and relatives. (Expect an avalanche of new MLM scams as the COVID-19 pandemic becomes a feminist nightmare, with 865,000 women dropping out of the workforce in September alone.) Just as Raniere did with DOS, these companies are sure to couch their predation in the language of feminism, marketing themselves as empowering a new class of #girlbosses, even as they prey on women’s economic precarity.

Raniere’s sentencing coincides with the entrance of another postfeminist horseman in the form of Amy Coney Barrett, the ultraconservative judge Donald Trump nominated to replace Ruth Bader Ginsburg on the Supreme Court. She was sworn in as a Supreme Court justice on October 26, the apotheosis of Senator Mitch McConnell’s campaign to reinvent the American judiciary as a conservative political engine. In her short time as an appeals court judge, Coney Barrett has argued for expanding gun rights and restricting abortion rights, couching all of her contradictory convictions in that great conservative judicial fantasy: total adherence to the original intent of the framers of the Constitution. Since the outset, when her law professor at Notre Dame secured her a clerkship with Justice Antonin Scalia, Coney Barrett’s career has been paved by men who saw her as a useful political tool. In a profile in the New York Times, Elizabeth Dias writes how Coney Barrett benefitted from a Republican initiative “to cultivate female and minority candidates for the courts to help counter the perception that the party was interested mainly in promoting white men.” Trump had planned for years to nominate Coney Barrett in the event of Ginsburg’s death, setting up an obvious, if cheap, comparison between the two female judges. Democrats’ opposition to her nomination has of course been met with Republican whining about how women should support women, with the Republican senator Martha McSally saying, “You would normally have the feminists on the left lining up to defend her. So we’re asking, where are those women?”

As Ellen Willis wrote in 1979 about the pro-life movement, “Its need to wrap misogyny in the rhetoric of social conscience and even feminism is actually a perverse tribute to the women’s movement.” The same is true now: as Coney Barrett becomes the right’s greatest hope of overturning Roe v. Wade, we are told that feminists are being hypocritical in our opposition to her. In truth, conservatives’ clumsy use of feminist rhetoric is an instinctive appeal to something more basic than the formalized women’s movement. They are calling on women’s powerful loyalty to one another, thus recognizing it as feminists’ most potent tool. When the pro-life movement became ascendant in the late seventies, it was because of its brilliant methods of undermining that loyalty, most often by reframing abortion not as “as a political issue affecting the condition of women,” as Willis writes, but “as an abstract moral issue having solely to do with the rights of fetuses.”

Coney Barrett belongs to a charismatic Catholic sect called the People of Praise who famously used to call their women leaders “handmaids,” though they stopped after the Hulu started airing its series A Handmaid’s Tale, possibly seeing it as a little on the nose. All members are assigned a male “head” who counsels them spiritually and practically; married women are “headed” by their husbands. If Coney Barrett managed to pursue a career that is mostly foreclosed to women in her religious group, particularly those who have seven children, there is no reason to believe she sees economic opportunities for women as something worth fighting for. Her solidarity with other women has been thoroughly eroded by both her conservative and religious indoctrination and her adventures in leaning in. According to the New York Times, “[The People of Praise] is almost entirely run by men in part because it ‘communicates to all men their shared responsibility for the life of the community,’ ensuring men do not leave family and community matters to women.” This statement also nods toward feminism, with its emphasis on men pitching in with domestic duties. But it can also be interpreted as a radical rejection of the high status of women in even many conservative church communities, where they can gain positions of authority and influence through teaching, volunteering, and music ministry. As MLMs exploit close-knit networks of women for their buying power, conservative Christianity has been seeking to cut those networks off at the root, making women ever more directly beholden to men. But when you look at all this manipulation up close, something startling becomes clear: would the corporate and political systems be trying so hard to stop women from organizing if we didn’t pose a threat? As Rep. Alexandria Ocasio Cortez captioned an Instagram post about the squad, herself and three other progressive congresswomen who have become the conservative movement’s favorite villains: “When your sisterhood is so powerful the President of the United States can’t stop thinking about it.”

*

There is an unsettling symmetry to the Amy Coney Barrett hearings, an echoing dread many women will feel even if they don’t examine it. The last confirmation hearings for a Supreme Court justice were a notably ugly moment in the Donald Trump presidency, amid a stream of ugly moments. At Brett Kavanaugh’s hearings, Dr. Christine Blasey Ford testified before the judiciary committee for four hours, calmly describing how Kavanaugh had sexually assaulted her when he was seventeen and she was fifteen. When it was Kavanaugh’s turn to testify, he threw a disturbing tantrum where he cried, yelled that he liked beer, and whined that he may never be able to coach children’s sports again. And still he was confirmed by a 52–48 vote in the senate, with the moderate, pro-choice Republican Susan Collins giving a mealy-mouthed speech on the floor of the Senate defending her yes vote by saying that Kavanaugh had assured her that he would not vote to overturn Roe v. Wade. I can’t be the only who felt this like a blow to the chest. It was the feeling that Kavanaugh’s confirmation was the end of the #MeToo movement as we knew it.

Now, along with Kavanaugh, Coney Barrett is poised to make life harder for millions of women, threatening abortion rights, the availability of contraception, and most immediately, the health care of families that rely on the Affordable Care Act. This confirms something we may have suspected, which is that the #MeToo message had been muddled and undermined. Despite all efforts, the connections were not clear, the message was not heard: there is a larger system keeping women on the margins of American life, of which sexual violence is only one tactic of enforcement, and for which justice against individual abusers is only a salve and not a cure.

We might have also suspected that #MeToo did not go far enough in its demands at the height of its cultural power. Since then, #MeToo seems to have devolved into a circular conversation about celebrity cancel culture, abandoning exactly the women who need defending most, those at the intersection of race, class, and gender oppressions who are not only the most likely to be sexually harassed and assaulted on the job, but who suffer most from abortion bans, the lack of childcare and paid parental leave, and the assault on affordable health care. In other words, when there was a national conversation around gendered violence, there was a failure to overtly integrate it with the other issues at the heart of the feminist cause. There were barriers to this, of course, mostly that the movement’s power was in its ad hoc coalition united by the barest of feminist demands: stop harassing us; stop raping us. Anonymous hotel workers and Fox News anchorwomen were gathered, uncomfortably and temporarily, under the same banner. If some of us saw the inconsistency in fighting for women to be able to safely spew hatred on Fox News, it still seemed like a net good, not to mention a source of delectable schadenfreude, to see Roger Ailes go down in flames.

This is clear evidence of how the organized feminist movement has deteriorated in this country, even as calling oneself a feminist has become more socially acceptable. We dare demand only safety, never security. Solidarity will only take us so far—we need theory, infrastructure, diversity, and nuance in fighting the forces of revanchism that seem to strike with more violence after any moment of feminist progress. The evangelical movement, corporate interests, and far-right forces have mounted a massive backlash against women’s equality since the seventies, comprised of many mini backlashes, of which the Trump presidency is only one. #MeToo was just a start to building back what has already been eroded. The fact that many people cannot differentiate between postfeminist “empowerment” and real feminism is a victory for those forces that have systematically opposed real gender equality. (Confusing the issue is a classic move in the conservative playbook: the greatest enemy of the Equal Rights Amendment was the empowered woman Phyllis Schlafly.) Postfeminist rhetoric has caused tangible harm, playing an active part in perpetuating the widespread sexual abuse that women until #MeToo were told they had to learn to live with. We are trained to believe that being a girl boss means persevering and not playing the victim. As the ESP mission statement says, “There are no ultimate victims; therefore, I will not choose to be a victim.”

NXIVM is also a #MeToo story: high-profile serial abusers like Harvey Weinstein led authorities to take the case against Raniere more seriously. There had been newspaper stories as early as 2012 detailing NXIVM corruption and accusing Raniere of violence and statutory rape. But when former DOS slaves took their story to the New York Times in 2017, they were told that it wasn’t necessarily newsworthy at the same time that the FBI told them that the branding of their flesh was consensual. After #MeToo, the tide turned quickly against Raniere, with an exposé in the Times, the exodus of dozens of members from NXIVM, and, soon enough, federal charges.

But, of course, defeating Raniere does not destroy the cultural forces that allowed him to belittle, control, and indoctrinate women through NXIVM for two decades, and broader #MeToo activism doesn’t either. A notable thing about DOS is the way that women’s relationships with other women were leveraged against them. Women were afraid if they left, not that they would lose access to Raniere, but that they would lose the close friendships with women that the group had forged. When recruiting for DOS, Allison Mack invited women to join her “women’s group,” and women with the same “master” often called each other sisters. Women still need sisterhood. There is no reason not to start more formal women’s groups like those who read, organized, commiserated, and raised their consciousnesses together as the decentralized structure of the women’s liberation movement during feminism’s second wave, and whose vacuum DOS, MLMs, church groups, social media communities, and group texts have made their feeble and/or sinister attempts to fill. Antiwoman forces tell us we should be satisfied with takedowns for people like Raniere, with our chance for a woman to replace a woman on the Supreme Court, no matter who she is. We know better. Interpret NXIVM as a new fairy tale, with Raniere as a particularly pathetic Bluebeard, and take its lesson to heart. Any women’s movement that does not demand justice for the most marginalized, that does not threaten the status quo, will eventually contribute to our oppression. In materials from the first Jness, Nancy Salzman said, “Welcome to the first women’s movement started by a man.” She seems to be foreclosing this as a criticism, but also to be pitching it as an improvement on all of those previous, irrational movements led by emotional women. This is a lesson of the NXIVM story, too: the way a false women’s movement can be taken down by a real one.

Alice Bolin is the author of Dead Girls: Essays on Surviving an American Obsession.

October 28, 2020

The Best Witch Novel Is One Nobody Talks About

On a visit to the UCLA Library, the author and scholar Maryse Condé found herself lost in the stacks. A library can be a spooky place. It is little wonder that they are so often listed among haunted buildings. The whispering shuffles of paper, the eerie quiet, the echoing click-clack heel-toe of shoes on cool linoleum floors. The impatience of a long-shelved book awaiting a reader might be the only thing to rival that of a spirit biding her time until the perfect audience appears. Says Condé of the inspiration for her novel I, Tituba … Black Witch of Salem, “I got lost in the huge building and found myself in the history section in front of a shelf full of books about the Salem witch trials. Looking through them, I discovered the existence of Tituba, whom I had never heard of before.”