The Paris Review's Blog, page 144

October 6, 2020

Painting with a Moth’s Wing

Agnes Pelton was overlooked during her lifetime, but her paintings are eternal. Deeply abstract and yet grounded in shape and line—she has a predilection for looming landmasses, jellyfish-like veils, rings of light, and the alignment of planets and stars—her work lays bare the workings of the universe. She once described her process as “painting with a moth’s wing and with music instead of paint.” These are cosmic visions projected from the sleeping desert floor. The first retrospective of her work in more than two decades, “Agnes Pelton: Desert Transcendentalist,” is on view through November 1 at the recently reopened Whitney Museum of American Art. A selection of images from the show appears below.

Agnes Pelton, Future, 1941, oil on canvas, 30 × 26″. Collection of Palm Springs Art Museum, seventy-fifth anniversary gift of Gerald E. Buck in memory of Bente Buck, best friend and life companion.

Agnes Pelton, Messengers, 1932, oil on canvas, 28 × 20″. Collection of Phoenix Art Museum; gift of The Melody S. Robidoux Foundation.

Agnes Pelton, Orbits, 1934, oil on canvas, 36 1/4 x 30″. Oakland Museum of California; gift of Concours d’Antiques, the Art Guild of the Oakland Museum of California.

Agnes Pelton, Day, 1935, oil on canvas, 25 1/4 × 23 1/2″. Collection of Phoenix Art Museum; gift of The Melody S. Robidoux Foundation.

Agnes Pelton, Departure, 1952, oil on canvas, 24 x 18″. Collection of Mike Stoller and Corky Hale Stoller. Photo: Paul Salveson.

Agnes Pelton, The Blest, 1941, oil on canvas, 37 1/2 x 28 1/4″. Collection of Georgia and Michael de Havenon. Photo: Martin Seck.

“Agnes Pelton: Desert Transcendentalist” will be on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art through November 1.

Something to Hold On To: An Interview with Rumaan Alam

photo credit: David A. Land

Leave the World Behind was written in the before times. It was written before the pandemic, the recession, and the deaths of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd. It was written before wildfires burned more than four million acres of the American West and before skies halfway across the globe were made blurry with smoke. And yet it feels, in a way, like the first novel to be written about our new world. This is not only because it centers around a group of people quarantined in a house together during a crisis (though it does), but because it offers a clear-eyed, if deeply unsettling, portrait of what emerges when our shared reality is bent, cracked, and forever altered.

The novel follows Amanda and Clay, a white couple from Brooklyn, who, following the seductive command of the novel’s title, go on vacation to a rural area on the East End of Long Island with their teenage children, Archie and Rose. But after a few indulgent days of hamburgers, sex, and drinking wine by the pool, the homeowners, a Black couple named G. H. and Ruth, arrive one night unannounced. They bring with them news that there has been a blackout in New York City, and, panicked, they have come to stay. It is an awkward, fraught moment that seems to set up a story about race and hypocrisy and misjudged expectations. Without giving too much away—Alam should teach a master class on the suspenseful withholding of information—the novel quickly spirals into something entirely different. Over the next twenty-four hours, a series of terrifying and inexplicable events befall the household. The internet and phone service go out; Archie comes down with a bad fever; flamingos land in the swimming pool; and the air is rent by a series of massive, deafening sounds. Overnight, the world becomes unrecognizable, and the strangers form a tense, unlikely union. Alam plays his cards close to the chest, explaining very little about the nature of the crisis. And in a way, uncertainty itself becomes the novel’s primary subject. Alam attends to the contours of that uncertainty with devastating precision.

At a time when focus has not come easily to me—my attention flickers restlessly between impossible headlines, bottomless news feeds, and the same four walls I have occupied since March—I was held still by the urgency, beauty, and uncanny familiarity of Alam’s world.

The author of two previous novels, Rich and Pretty (2016) and That Kind of Mother (2018), Alam’s writing has appeared in the New York Times, New York Magazine, and The New Republic, where he is a contributing editor. He also cohosts two podcasts for Slate. Leave The World Behind is a finalist for the National Book Award for Fiction.

I spoke to Alam by phone in late September. He was at home with his husband and kids in Brooklyn, where he has spent most of the past seven months since the pandemic began. He spoke softly, he explained, because his children were attending online school in another room.

INTERVIEWER

In your new novel, strangers are stuck in a house together as the world undergoes a mysterious and unidentified disaster. You wrote the book long before the pandemic began, but it’s almost impossible to read it or discuss it without acknowledging the eerie resonances it has with our current moment.

ALAM

Yes, totally. And, of course, in a very simple way, it’s just a strange coincidence. The fact that I fixed on the metaphor of isolation and the device of people trapped in a house, without knowing that we, American readers, would all be people trapped in our houses, was just an accident of timing. But the novel is also grappling with things that I think have been in the cultural atmosphere for a long time. It’s talking about technology and our strange dependence on it. It’s talking about race and the very complicated ways in which race defines people in our country and in our culture. These are not new ideas. These are things that have been in the air for a long time.

It’s inevitable that the cultural and political context of a given moment will determine how we understand art, right? But art isn’t necessarily a reflection of that immediate context. It’s usually the product of an earlier moment. A painting takes time. A film takes time. A book takes time. It’s an understandable impulse to try to make sense of art through the lens of the current moment. And this current moment—I’m talking particularly about the coronavirus—is so heightened. It’s so strange and unusual that it has really dramatically affected how we understand art. There are so many relics of the recent past that already feel irrelevant. When I say that, I am thinking about a reality TV show that I happen to be watching. It was filmed before the pandemic, and it just feels like it’s from a million years ago. But I don’t think that that’s necessarily a fair way to consider art. It has to have a longer or a broader purpose than simply to riff on something in the moment. In many ways, I would be very suspicious of a work that emerged right now—a film, a book, even a short story—that aimed to talk about what is happening right now … whether that is the coronavirus or the 2020 election, because it’s still happening. You need a little context, a little distance.

INTERVIEWER

That makes a lot of sense.

ALAM

A while ago, I posted a related question on Twitter. I was trying to solve this problem intellectually and I asked around to see if anyone thought there was a really good novel about 9/11. I don’t mean a novel that depicts 9/11, but a novel that distills what that moment felt like in our cultural and political life, in our individual psyches, in our collective psyches. A novel that really got at what that moment was. And a friend of mine responded, very wisely I think, that they felt it took until Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried for the culture to digest in literature the Vietnam War. And that book didn’t come out until like two decades after the war ended. I think that is a very astute statement. It takes time to digest something in a work of art. If my book was, in a way, an attempt to digest current uncertainties, they were pre-pandemic, pre–Donald Trump existential uncertainties. We are going to see much more art that wrestles with this question.

INTERVIEWER

That said, I think people are hungry for art that speaks to the bizarre moment we are in. And it’s been interesting to see the novels and films, some of which are decades old, that have a renaissance right now. Is there a particular book or film that you have gone back to during the pandemic?

ALAM

The book that I always recommend, that no one ever reads, is The Magic Mountain, which is, to my mind, one of the best books ever written. The way that it talks about isolation and solitude—both a literal solitude and also, more profoundly, the solitude of all people—is astonishing.

INTERVIEWER

Leave the World Behind employs a somewhat conventional thriller or horror narrative structure, at least in the first few chapters. Everything is going along fine, and then there is a knock on the door. Strangers appear, and there is tension. But then the book pivots, disrupting the typical horror tropes and becoming … something else entirely. Why did you choose this mode of storytelling? What was compelling to you about disrupting the boundaries of the genre?

ALAM

That’s a nice way of putting it. In a way, the novel is constructed out of convention layered upon convention. At first, this was very helpful to give the story a shape that felt recognizable. The book begins with the narrative of an upper-middle-class family going on vacation, and with the suggestion that the change in geography will occasion a change in life—there are so many books like that. Another convention is the knock on the door, right? The strangers. Maybe with menace. Maybe with horror. And they are Black strangers, which sparks discomfort. Because it also echoes and reveals the prevailing narratives about race in our culture. Guess who’s coming to dinner? The surprise guest revealed to be a race you don’t expect.

I just love those layers. I love seducing the reader into thinking that she is going to get one kind of book, or one kind of storytelling experience. I imagine she reads the first fifty pages and thinks, Okay, I understand this book. It is a middle-class novel of manners. It’s a book about rich white people, and it’s established that there’s going to be some kind of investigation into the couple’s marriage or what it means for them to be parents or how they have reconciled their professional ambitions with their parental responsibilities. But none of that really happens because it is interrupted by a knock on the door. The reader adjusts her experience and thinks, Okay, this is going to be a story about race. It will be a story about uncomfortable confrontations. For a moment, she thinks it might even be a story about crime. But then that script gets flipped, too. It’s not a trick, exactly, but a kind of feint, a way of leading the reader to what I hope is a wholly different, or more exciting, book than she might have expected. What I hope emerges at the end of the book is that the product of all this artifice is, counterintuitively, realism—because that’s what it is to live in reality. Reality is like a mystery novel where we don’t know the ending.

INTERVIEWER

The book is enormously suspenseful. Can you talk a little bit about how you approached creating that suspense, on a craft level?

ALAM

I didn’t study widely how to do it, but I did read Pet Sematary while I was revising this book. When I think about Stephen King, I think of his particular ability to hold the reader in his hands. Which he has done across so many books. And when I read that book, I looked at it not so much as a reader, but, like you said, as a craftsman. That book is written with such extraordinary confidence. When it first starts, it’s recognizable. And then very quickly, about forty pages in, the whole thing has gone totally off the rails. It’s presented as reality, but, of course, it’s absolutely insane. That book is terrifying and crazy, and it just keeps getting further and further from any recognizable universe. Reading that, I realized that I had to be confident in what I was doing, and I had to do it very quickly.

I tried to strike a very delicate balance in Leave the World Behind, where the opening section lingers just long enough to trick you into thinking it’s one kind of book but not so long that you misunderstand the reading experience you’re about to have. One of the things that helps accomplish that is the whole book takes place over just a few days, and most of the real action happens in just a few hours. It’s an extremely compressed timeline, which makes it all feel very urgent. As to the question of why… Well, it’s an act of seduction. It’s a way of making palatable something that is very unsettling. It made a lot of sense to me to use this form to tell an unsettling story. It makes you uneasy.

INTERVIEWER

I don’t often read mysteries or thrillers, and I was surprised by how dramatically the tension and suspense of the book worked on me physically. When Rose and Archie go walking into the woods alone, for instance, my stomach quite literally churned with anxiety—the way it would while watching someone open a basement door in a horror movie. I rarely experience that kind of fear with a novel. Is this something you have experienced as a reader? Is it part of what attracted you to the genre?

ALAM

It’s not a genre I read very much in my current life, but I certainly did when I was young. I read a lot of mysteries, a lot of thrillers—closer to horror than to science fiction. And it made a big impression on me. I really admire the genre. When well practiced, it’s an extremely efficient narrative tool. I guess that’s a dumb thing to say, because the same is true no matter what form you’re talking about. A sonnet or a short story can be incredibly efficient, too, of course. But I think there is a prevailing snobbery about writing horror or thriller, “genre fiction,” that it’s fundamentally less serious. I don’t think that’s true. Because, in the end, it’s really about building a very efficient machine in order to achieve a very specific goal. The author wants to make you quake. He wants to make you shiver. He wants to terrify you. Literary fiction is a genre all it’s own, with its own expectations and conventions, and the aim is less often to elicit that emotional response. It’s more often about doing something compelling on the level of language or style—it’s a different kind of endeavor. But I don’t think that means one is better than the other.

INTERVIEWER

Here, permit me a slight spoiler—I’d like to be able to talk about the book as a whole. Unlike a classic mystery novel, the book never really offers a solution for the mystery at hand. The disaster at the center of the book remains vague, and the characters’ theories are merely speculative. The narrator does offer several cryptic clues about what might be going on in the outside world—it seems to be an environmental disaster of some kind, though there are plane crashes and geopolitics and flamingos involved. Possibly some kind of nuclear conflict. While you were writing, did you have a specific concept of what exactly was taking place? And can you talk a little bit about the decision to leave the catastrophe unnamed? Did that allow you a kind of authorial space that you might not have had otherwise?

ALAM

Agatha Christie novels are satisfying because they give you an explanatory ending. But that’s the one thing that life can’t give you. So for me, in wanting to make this book realistic, I felt strongly that I needed to decline that kind of closure.

Yes, there are little glimpses. But they are almost completely impossible to reconcile with one another. You hear about a television star being hit by a car on the Upper West Side, and then you hear about a plane crash in the Midwest. Those two things could be related, or they could be unrelated. That misdirection was intentional. It sort of turns readers into Claire Danes in Homeland, standing with their backs against the wall, trying to make sense of the chaos. But I think that’s very effective, because it’s like life. I mean, look around. This is just how it is. This is what it feels like. You only ever get glimpses of a larger picture. You try to make sense of them. You think that you have, but you haven’t really.

Don’t get me wrong—I don’t mean to imply that I am some conspiracy theorist. I’m not someone who doubts the objectivity of reality. In fact, I think one of the biggest issues we’re facing in our culture at the moment is that many people do. But I don’t think that any individual can ever grasp the whole of what is going on in the world around them. To me, that is a fact. But it’s also truly unsettling. So, to answer your question, no, I don’t really know what happens. I hope that the way the novel is built allows each reader to have his or her own projection of what might be happening. I have a friend who said to me, “It’s all a fever dream, right? None of this is actually happening. They just got carried away.” I think that’s an interesting reading.

INTERVIEWER

Yes, I also wondered at times whether it was all just paranoia.

ALAM

It doesn’t feel like my place to say whether that’s right or not, but there is evidence that supports that particular reading. I have heard some other people say that the book operates as a metaphor for climate change or for parental love. I think each reading betrays the reader’s own biases and the predilections in their mind. In a way, it’s an act of authorial control to withhold information, but I also see it as an utter evasion of authorial responsibility. I just sort of hand the system over to the reader and say, I don’t know what this means, but I’m out of here. Sure, I have my own feelings about what I am interested in investigating emotionally. But, in the end, my intention doesn’t matter.

INTERVIEWER

I’m curious about this idea that we are never able to completely make sense of everything going on around us. As you mentioned before, the characters in the novel are totally cut off from the world. Their phones don’t work, the internet is down, they have no access to information. But they seem to believe that if they could just read the New York Times and learn more about what’s happening in the world, they’d be better off. G. H. in particular wishes for this, believing knowledge will be an antidote to his fear. This is an idea that a lot of people have, I think. Certainly in the early days of the pandemic, nearly everyone was reading the news obsessively. Staying informed feels comforting, especially in a crisis. But the novel seems to challenge the idea that information is always useful. At a certain point, I began to wonder what practical difference it would make for the characters to know what was happening. Would it simply frighten them more? Would it change the fact that they are all stuck in a house together? Would it help them survive? It made me reflect on how often information offers only the delusion of control.

ALAM

Absolutely. The book questions the comfort of information in a couple different ways. For one, in the first section, it interrogates and mocks the onslaught of information that is modern life, and the ways in which almost all of the information we receive from our phones and from the internet is just monumentally unhelpful. It makes us think we know so many things that we actually don’t. And I am really suspicious of the idea that more information is always a good thing. For example, if you knew you were going to get hit by a car in May of 2023, would that information really be helpful to you? Would that information help guide how you were going to live in a meaningful way? I don’t know if it would.

The characters in the novel lack information about their world, but so does the reader. The reader is missing many, many pieces of the puzzle about the fictional world they are inside, and my hope is that this encourages them to consider that information isn’t always salient or useful. In that way, the book mirrors the world at large. This is what real life feels like. You don’t have all the information. You will never have all the information. You have some of it. You’re trying to do the best with what you have, and you’re living according to hunches and ethics and intuition and an understanding of the world that’s totally imperfect. You’re just trying to do the best you can, and you’re often failing. I think that is how we all feel all the time. I think anything else is just hubris. It’s not unrelated to our dependence on our phones and technology. We are totally helpless without them, though that is a difficult thing to admit.

INTERVIEWER

For a book that is frequently terrifying and satirical, it also contains moments, particularly toward the end, that feel deeply earnest and hopeful. One line that stuck out to me as especially resonant in the current moment was, “You demanded answers, but the universe refused. Comfort and safety were just an illusion. Money meant nothing. All that meant anything was this—people, in the same place, together.”

ALAM

I don’t think it’s a book without hope. It’s dark, but it’s not wholly pessimistic. I think the novel’s optimism lies really in that one idea, in communion. The simple, human reality of occupying space together. I’m glad that feels resonant right now. I hope that the novel can be good company in that way. This is a moment that is so baffling and extreme that any insight into the way we are supposed to behave or what we are supposed to do feels really lovely and helpful. Personally, I tend to get more of that from visual art than I do from books, and it has been an added complication of the past few months that I haven’t been going to see any art. I haven’t been to a museum, even though they have reopened in New York. It just feels a little too scary and risky. But I’m really missing it. That moment of interaction with a work of art offers something that even the most comprehensive understanding of the headlines will never be able to provide. It gives us something to hold on to.

Cornelia Channing is a writer from Bridgehampton, New York. She is a copy editor at New York Magazine.

October 5, 2020

The Art of Distance No. 28

In March, The Paris Review launched The Art of Distance, a newsletter highlighting unlocked archive pieces that resonate with the staff of the magazine, quarantine-appropriate writing on the Daily, resources from our peer organizations, and more. Read Emily Nemens’s introductory letter here, and find the latest unlocked archive selection below.

“We’re trying something new with The Art of Distance this month. Over the next four weeks, we’re serializing a story in four parts. Deciding what to share was no easy task. We have more than a thousand stories, novel excerpts, and other permutations of storytelling in the magazine’s archive. (I’d be remiss not to remind you that subscribers to the print magazine just have to link their account to get digital access to those stories in their entirety—and to more than four hundred Writers at Work interviews and north of four thousand poems as well.) That being said, Edward P. Jones’s “Marie,” which originally appeared in issue no. 122 (Spring 1992), felt like a natural choice for this moment. (The story later appeared in Jones’s PEN/Hemingway Award–winning debut collection, Lost in the City.) Here is a story about the possibility—and the frustrations—of Washington, D.C., about ageism and bureaucracy and the importance of listening to each other. So without further ado, please enjoy part 1 of “Marie,” by Edward P. Jones.” —EN

P.S. Today also happens to be Jones’s birthday—happy birthday, Edward!

Every now and again, as if on a whim, the Federal government people would write to Marie Delaveaux Wilson in one of those white, stampless envelopes and tell her to come in to their place so they could take another look at her. They, the Social Security people, wrote to her in a foreign language that she had learned to translate over the years, and for all of the years she had been receiving the letters the same man had been signing them. Once, because she had something important to tell him, Marie called the number the man always put at the top of the letters, but a woman answered Mr. Smith’s telephone and told Marie he was in an all day meeting. Another time she called and a man said Mr. Smith was on vacation. And finally one day a woman answered and told Marie that Mr. Smith was deceased. The woman told her to wait and she would get someone new to talk to her about her case, but Marie thought it bad luck to have telephoned a dead man and she hung up.

Now, years after the woman had told her Mr. Smith was no more, the letters were still being signed by John Smith. Come into our office at Twenty-First and M Streets, Northwest, the letters said in that foreign language. Come in so we can see if you are still blind in one eye. Come in so we can see if you are still old and getting older. Come in so we can see if you still deserve to get Supplemental Security Income payments.

She always obeyed the letters, even if the order now came from a dead man, for she knew people who had been temporarily cut off from SSI for not showing up or even for being late. And once cut off, you had to move heaven and earth to get back on.

So on a not unpleasant day in March, she rose in the dark in the morning, even before the day had any sort of character, to give herself plenty of time to bathe, eat, lay out money for the bus, dress, listen to the spirituals on the radio. She was eighty-six years old and had learned that life was all chaos and painful uncertainty and that the only way to get through it was to expect chaos even in the most innocent of moments. Offer a crust of bread to a sick bird and you often draw back a bloody finger.

John Smith’s letter had told her to come in at eleven o’clock, his favorite time, and by nine that morning she had had her bath and had eaten. Dressed by 9:30. The walk from Claridge Towers at Twelfth and M down to the bus stop at Fourteenth and K took her about ten minutes, more or less. There was a bus at about 10:30, her schedule told her, but she preferred the one that came a half hour earlier, lest there be trouble with the 10:30 bus. After she dressed, she sat at her dining room table and went over yet again what papers and all else she needed to take. Given the nature of life—particularly the questions asked by the Social Security people—she always took more than they might ask for: her birth certificate, her husband’s death certificate, doctors’ letters.

One of the last things she put in her pocketbook was a knife that she had, about seven inches long, which she had serrated on both edges with the use of a small saw borrowed from a neighbor. The knife, she was convinced now, had saved her life about two weeks before. Before then she had often been careless about when she took the knife out with her, and she had never taken it out in daylight, but now she never left her apartment without it, even when going down the hall to the trash drop.

She had gone out to buy a simple box of oatmeal, no more, no less. It was about seven in the evening, the streets with enough commuters driving up Thirteenth Street to make her feel safe. Several yards before she reached the store, the young man came from behind her and tried to rip off her coat pocket where he thought she kept her money, for she carried no purse or pocketbook after five o’clock. The money was in the other pocket with the knife, and his hand was caught in the empty pocket long enough for her to reach around with the knife and cut his hand as it came out of her pocket.

He screamed and called her an old bitch. He took a few steps up Thirteenth Street and stood in front of Emerson’s Market, examining the hand and shaking off blood. Except for the cars passing up and down Thirteenth Street, they were alone, and she began to pray.

“You cut me,” he said, as if he had only been minding his own business when she cut him. “Just look what you done to my hand,” he said and looked around as if for some witness to her crime. There was not a great amount of blood, but there was enough for her to see it dripping to the pavement. He seemed to be about twenty, no more than twenty-five, dressed the way they were all dressed nowadays, as if a blind man had matched up all their colors. It occurred to her to say that she had seven grandchildren about his age, that telling him this would make him leave her alone. But the more filth he spoke, the more she wanted him only to come toward her again.

“You done crippled me, you old bitch.”

“I sure did,” she said, without malice, without triumph, but simply the way she would have told him the time of day had he asked and had she known. She gripped the knife tighter, and as she did, she turned her body ever so slightly so that her good eye lined up with him. Her heart was making an awful racket, wanting to be away from him, wanting to be safe at home. I will not be moved, some organ in the neighborhood of the heart told the heart. “And I got plenty more where that come from.”

The last words seemed to bring him down some and, still shaking the blood from his hand, he took a step or two back, which disappointed her. I will not be moved, that other organ kept telling the heart. “You just crazy, thas all,” he said. “Just a crazy old hag.” Then he turned and lumbered up toward Logan Circle, and several times he looked back over his shoulder as if afraid she might be following. A man came out of Emerson’s, then a woman with two little boys. She wanted to grab each of them by the arm and tell them she had come close to losing her life. “I saved myself with this here thing,” she would have said. She forgot about the oatmeal and took her raging heart back to the apartment. She told herself that she should, but she never washed the fellow’s blood off the knife, and over the next few days it dried and then it began to flake off.

Toward ten o’clock that morning Wilamena Mason knocked and let herself in with a key Marie had given her.

“I see you all ready,” Wilamena said.

“With the help of the Lord,” Marie said. “Want a spot a coffee?”

“No thanks,” Wilamena said, and dropped into a chair at the table. “Been drinkin’ so much coffee lately, I’m gonna turn into coffee. Was up all night with Calhoun.”

“How he doin’?”

Wilamena told her Calhoun was better that morning, his first good morning in over a week. Calhoun Lambeth was Wilamena’s boyfriend, a seventy-five-year-old man she had taken up with six or so months before, not long after he moved in. He was the best-dressed old man Marie had ever known, but he had always appeared to be sickly, even while strutting about with his gold-tipped cane. And seeing that she could count his days on the fingers of her hands, Marie had avoided getting to know him. She could not understand why Wilamena, who could have had any man in Claridge Towers or any other senior citizen building for that matter, would take such a man into her bed. “True love,” Wilamena had explained. “Avoid heartache,” Marie had said, trying to be kind.

They left the apartment. Marie sought help from no one, lest she come to depend on a person too much. But since the encounter with the young man, Wilamena had insisted on escorting her. Marie, to avoid arguments, allowed Wilamena to walk with her from time to time to the bus stop, but no farther.

Want to keep reading? Subscribers can unlock the whole story today. Otherwise, tune in next Monday for part 2, and meanwhile, check out Edward P. Jones’s unlocked Art of Fiction interview.

Memory Haunts

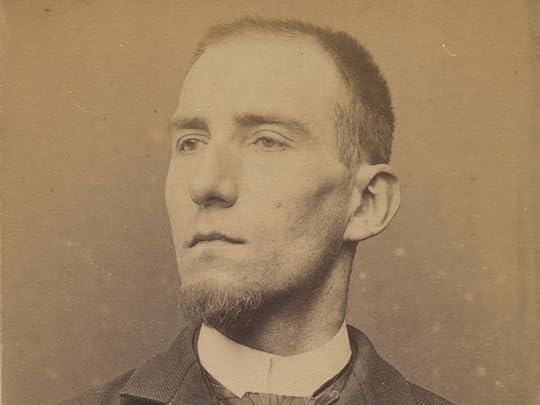

John Edgar Wideman on the campus of the University of Pennsylvania, 1963. Photo: Jim Hansen for LOOK magazine. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

These ruins. This Black Camelot and its cracked Liberty Bell burn, lit by the same match that ignited two blocks of Osage Avenue.

—John Edgar Wideman, Philadelphia Fire

Neighbors were warned to clear out of the area before nearly five hundred police officers arrived at the house, 6221 Osage Avenue, on May 13, 1985. Electricity and water were shut off. The police speaker boomed. Tear gas was lobbed, gunfire returned, a melee of back and forth. Then the home was bombed. A conflagration erupted and spread wildly. Eleven residents died; sixty-five homes were destroyed. It was an unprecedented tragedy in the city of Philadelphia.

This is the event that John Edgar Wideman takes on in Philadelphia Fire, first published in 1990. As a writer, Wideman is inextricably connected to Pittsburgh, his home city. But this is a Philadelphia book, set in the city where Wideman attended college and later taught. In its pages, the geography of Philadelphia streets and the political fabric that was laid upon them is precise and exacting. In a sense, Philadelphia Fire is not just a map of the city but of the nation and our collective condition.

The first part of the book is a fictionalized account of the historic event. Cudjoe, a writer, is threading together the story of May 13, 1985, when the city of Philadelphia bombed the home of members of the MOVE political organization. MOVE, not an acronym but an imperative, as in “on the move,” is a Black liberation organization first founded in 1972. From the outset, they were distinguished among numerous peer organizations for their environmentalism, cooperative living, and strong advocacy of animal rights. Based in Philadelphia, MOVE raised the ire of the city establishment and many members of the surrounding community for their vociferous political announcements and unconventional domestic habits. They’d had prior run-ins with the notorious police chief Frank Rizzo. Still, the retaliation against MOVE by the city leadership sent shock waves through the surrounding community for decades to come.

Though fictionalized, the realpolitik of the city pulses on every page of Philadelphia Fire. The rise of a Black political machine in the city, capstoned by the first African American mayor, is set against the residual presence of a radical Black political organization in Ronald Reagan’s America. Desire, patriarchy, and poverty swirl around the cast of Black men and boys as Cudjoe looks for a child survivor who cannot be found. The lost child and the theme of lost childhood echo through the entire work.

The second part of Philadelphia Fire is a step back. Wideman allows us to see the ways in which his and Cudjoe’s biographical details overlap. Cudjoe is a fictionalized version of the author at work, returning to the city of his college years, where he first escaped Pittsburgh and then later served as a faculty member at the University of Pennsylvania. Wideman intersperses details from his own life, as is characteristic of his writing. The ever-present grief of his brother’s and son’s incarcerations, and the interstitial space of the Black creative intellectual, both a member of the elite and speaker of the dispossessed, are cogently and powerfully rendered. Though Philadelphia Fire is more grammatically conventional than some of his other books, Wideman is as inventive and architecturally sophisticated here as always. He moves in and out of moments of fictionalization and commentary in a manner that makes the novel as much a lesson in craft as a work of art. How does one tell a story that is important because it deals with matters of life and death? The question is asked and answered.

For Wideman, interior anguish is both separate from and intrinsically connected to the depths of American racism. There are personal matters: dusk on a basketball court, the difficulties of marriage, the aging body and raging yearnings. And there are social ones: What happened to the sixties? What happened in the eighties? What was coming in the nineties? Each confronted decade comes with a riffing soundtrack. The sixties are punctuated with an animated James Brown, a country boy like Mayor Wilson Goode, navigating the urban terrain of Black Philadelphia. The eighties are sign-posted with the classic Aretha Franklin song “Who’s Zoomin’ Who,” turned from a ditty of lover’s play to a tale of political power; and the nineties with the pastiche of hip-hop, fragments of a broken past glued back together in order to hold something. Wideman has a gentle hand with his citations, leaving it to the reader to unearth how masterfully layered the text is. And underneath it all, Wideman consistently reminds us that this is also the city that the most important Black intellectual of the twentieth century, W. E. B. Du Bois, depicted in The Philadelphia Negro, a landscape for escape from the brutal South (made plain by his artful reference to Robert Hayden’s classic runaway poem, “Runagate Runagate”) and place of captivity in the ghettos of the cruel North.

Fate teases even further back as Wideman intersperses the story of a teacher who attempts to stage Shakespeare’s The Tempest with actors who are Black children in West Philadelphia. This Elizabethan comedy about colonialism is both an ironic and cutting example of the persistence of dispossession and displacement in Philadelphia but also across the globe when it comes to the people who Du Bois described as living “behind the veil.”

In the intervening years since the publication of Philadelphia Fire, its relevance has heightened. Documentaries and scholarly works have been produced that detail and depict the tragedy of the bombing. Mumia Abu-Jamal, a journalist and former member of the Black Panther Party who sympathetically covered the MOVE organization, was convicted of killing a police officer in 1981 and has remained incarcerated since. Jamal has become an internationally known political figure and remains associated with MOVE. The profound irregularities in his trial have also served as a symbol of both the racial injustices endemic to mass incarceration and the targeting of Black radical organizers in the seventies. Between 2018 and 2020, six members of MOVE, Debbie, Janine, Janet, Eddie, Delbert, and Chuck, all bearing the last name Africa like the organization’s founder, John Africa, were released from prison after forty-plus years, time they served for convictions related to a 1977 shoot-out that left a police officer dead. Others, Merle and Phil Africa, died while in prison.

Philadelphia Fire’s opening is particularly prescient. Wideman starts on a Greek isle, where his fictional alter ego, Cudjoe, is an apprentice to history and literature in the form of a man named Zivanias. In retrospect, we know that Birdie Africa, the child who ran from the flames, his body covered in burns, and only one of two survivors of the bombing, was found dead onboard a Caribbean cruise ship in 2013. Water, like fire, is a textual trope that both overwhelms and crystallizes.

And there is a timelessness to certain passages that make the book at once instructive history and immediately poignant. One in particular stands out as speaking to our collective moment, though Wideman is speaking directly to his son Jacob, who has spent most of his life incarcerated. He writes:

I’m not looking to give you consolation. I wish I was able. What I’m trying to do is share my way of thinking about some things that are basically unthinkable. I cannot separate myself from you. Yet I understand we’re different. I will try to accept and deal with whatever shape your life takes. I know it’s not my life and try as I might I can’t ease what’s happening to you, can’t exchange places or take some of the weight for you. But I believe you have the power in your hands to do what no one can do for you. Live your life strongly, fully, moment by moment. Make do. Hold on.

Philadelphia remains the poorest major city in the United States. Its Black communities are still, as Philadelphia Fire depicts, economically devastated and yet filled with intensive political and creative energy that takes almost as many paths as there are people. On any given weekend, you can return to the place Cudjoe went looking for a story to tell: Clark Park. On any given Saturday at Forty-Third and Baltimore, there are families and ballers, players and gentrifiers. There is also a quiet humming detente between the haves and the have-nots, between the old and new. You can see the ones who have hardscrabble living, sustaining themselves on a shrinking territory and living in the along. From that vantage point it is easy to understand that Wideman’s guidance to hold on, make do, and live strongly is an essential, ancestral wisdom. I don’t suppose a community easily forgets being set ablaze or drowned in grief any more than they forget the plantation, the migration, the segregation, and the deindustrialization. Memory haunts. And there, thirty-seven blocks to the west of where the Liberty Bell is held behind glass for tourists to admiringly behold, you’ll find a place where its cracks are actually felt.

Imani Perry is the Hughes Rogers Professor of African American Studies at Princeton University and the author of six books, including the award-winning Looking for Lorraine: The Radiant and Radical Life of Lorraine Hansberry and Breathe: A Letter to My Sons.

Excerpted from Philadelphia Fire , by John Edgar Wideman. © Imani Perry. Reprinted by permission of the author.

The Eleventh Word

The sky was a slate of electric indigo. We were sitting in the bath, my year-and-a-half-old son and I. My wife popped her head in the door. He looked at her, giving her a smile I will never get, and then pointed to the painting of a magenta fish on the wall.

“Sheesh,” he said.

“Fish?” She said.

“Sheesh!” He said.

It was, perhaps, his eleventh word. He had dog and ball and duck and bubble and mama and (mysteriously in our lesbian household) dada and nana (for banana) and vroom vroom (for cars) and hah-hah (for hot) and (the root of so many of our evils) what’s dat? What’s dat? What’s dat?

And then, there it was: fish.

It should have been a tragic moment for me. I, of all people, should have sensed the danger in it. I had just spent the last ten years of my life working on a book called Why Fish Don’t Exist, arguing that the word “fish” is symptomatic of our human inability to see the world as expansively as it is. In short, scientists recently discovered that many of the creatures we typically think of as “fish” are in fact more closely related to us than to each other. And when you accept this fact you will see that the category of “fish” is a bum category—an act of gerrymandering we perform over nature to make it line up with our intuition. But it’s a lie, this category of “fish,” a mistake, a meaningless group that hides incredible nuance and complexity.

And “fish” is just one glaring example of this thing we do all the time—group things together that do not belong under one label in the name of maintaining our convenience, comfort, power. My book, in large part, is a plea to approach the world with more doubt—more doubt in our categories, more doubt in our words, more curiosity about the organisms pinned beneath our language. The reward, as I promise in the book, is a more expansive world, “a wilder place,” where nothing is what it seems, where “each and every dandelion is reverberating with possibility.”

And so, as the word “fish” rolled off my son’s tongue for the very first time, I should have felt that hot burst of fricative air as a puncturing of his innocence—sheeesh. His fall from grace in real time, his ejection from a Garden of Eden I had just spent a decade trying to hack a path back into. I should have squeezed my palm to his lips and pressed hard so no more words could spill out.

Instead, I tested him. I pulled up a photograph of a goldfish on my phone. “Sheesh.” A salmon. “Sheesh.” A mottled blue coelacanth, fleshy and finned. “Sheesh.”

“Yes!” I squealed in the highest octave I could reach, cementing the mistake with my glee.

*

Over the next few weeks, he revealed to me that fish were everywhere in the city of Chicago. Fish along the mosaicked wall of the pedestrian underpass to Lake Shore Drive, now barricaded with yellow tape to prevent the spread of COVID-19. Fish inside the library books we could no longer return. Fish in the windows of the shuttered nursery school on Clark. Sheesh, sheesh, sheesh, he would point his little scepter-finger, stunning the former confusion into mastery. In his care, a snake was also a fish; a turtle, a fish; and one morning as we opened the window to let an April breeze roll through the apartment, the potted banana palm became a fish, her fins suddenly paddling the air.

As our world was closing in, his seemed to be exploding. The word “fish” turned out to be a sacred key, one that granted him access to the entire animal kingdom. Suddenly, no creature was unknown to him. If a dog walked by, it was “dog.” If a bunny hopped by, it was also “dog.” The cows, bears, zebras, kangaroos, giraffes, and elephants stuffed inside our children’s books—all “dog” to him. As for birds—the robin roosting on our porch rafter, the cardinal in the bush, the pigeons flying with a new woodblock elegance across the quieted sky—all “duck.” Everything else was “fish.”

It was Aristotle’s same system of classifying animals into three groups—land, sea, or air. One morning, he called an ant a dog. His chest began to puff just a little bit. Mine did, too. I did not yet sense the threat.

In late April, we learned of one of the few nature preserves still recklessly open and we plunged in. We walked through archways of naked underbrush, brambles holding in their buds, carpets of moss stealing the show. “Dirt,” our son said. “Yeah! Dirt!” We said, pointing to the infinitely complex swirl of mineral, mycological, entomological, and electrical matter beneath our feet. That very same day came “wawa,” for the small creek at the end of the hike and, later, for rain and baths and thirst. Next was “stick.” “Yellow” bloomed for one day, then left us. The tiny black dogs that crawled along the cracks in our porch became “bug,” then “ant.” We cheered with every word—two women waiting upon the doorstep, giddy to welcome him into our world of language.

And then, five weeks after he first said the word “fish,” it happened.

We shouldn’t have gone to see my in-laws. But … they’re young. Not even sixty. They don’t play tennis, but they could.

We wore our masks and sat at the other end of a long rectangular table. They served mushroom risotto, cooked in an instant pot. Mango and strawberry and yogurt in tiny crystal glasses, because why not. We put our son to bed in their guest room.

Around 10 P.M., we were all still up, still chatting, when our son started screaming. Not crying. Screaming. It was a sound we’d never heard. My wife went up, but after a few minutes, the volume had not lowered. I leaped up the carpeted stairs, worried he was sick, worried he had a fever, worried he had—but my wife shook her head, puzzled, “He isn’t hot,” she whispered. I tried to take him into my arms, sure I could settle him, but he recoiled. He looked up at me with no recognition.

We tried everything. Rocking him, showing him a book, the one with the penguins who like each other so much. We tried warmed milk. Nothing. Finally my wife took him over to a framed photograph of Coptic tapestries. Various trees birthing goat-like creatures with curling horns, and snail-like creatures with spiraling shells, and maybe snakes and definitely vines all coiling into one another in such a hallucinatory way that it would have caused me to have a psychotic break if I’d been as disoriented as my son. My wife got him up close to the glass and started whispering the names of what she thought she saw. “Goat,” she said, tapping the glass. “Flower. Snail. Duck.” Thud. Thud. Thud. And slowly, through shaking inhalations, he settled enough for us to pack him up and drive home.

*

Once upon a time there was a German psychologist whose name I am forgetting—which will, itself, become relevant in just a moment—who argued that when you don’t name a thing it stays more active in your mind. Specifically, he found that you have better recall for the details of an unsolved task, an unfinished puzzle, an unnamed psychological phenomenon, than a solved or labeled thing. “Loose ends prevail” could have been the name of his law, but it was—I’m checking my notes—the Zeigarnik effect. The man’s name was Zeigarnik and he was Russian, not German. But still. It has stayed with me, this idea with a hard-to-remember name about how unnamed ideas are easier to remember. This rabid little law that suggests that unlabeled things gnaw and tug at you with more vigor, their parts and powers somehow more alive when they are left to roam wild, outside of the confines of our words.

With the name comes a kind of dormancy. The name, in this metaphor, is a trap. It’s the lid on the jar that extinguishes the firefly.

*

The next morning, our son was fine.

My wife and I weren’t.

“What was that?” We said to each other, shaking our heads over coffee prep and neglected dishes, glancing back at him, merry in his high chair.

My wife went into work that morning at the hospital where she is a psychologist to kids who have come into contact with Chaos’s whims—amputations and paralyses and premature birth. She took her supervisor aside and asked if she had any thoughts on a night terror like the one we’d seen. Her supervisor told her not to worry, said it was a common occurrence around eighteen months, a by-product of all the neurological growth that happens around that time. I pictured a lightning bolt discharging from the growing ion storm of his mind.

I had done my own half-hearted investigating. Some fruitless googling and a serendipitous phone call with a colleague who mentioned that his toddler had had her first night terror the very same night. We joked that there must have been something in the air. “That’s reassuring!” I heard myself saying, un-reassured.

*

I left them for five days. My book tour had been canceled. I needed nature. I needed something. I drove to West Virginia. I hiked on a ridge trail and saw a lady’s slipper orchid, whose name I only learned weeks after I saw her. This, well, vagina on a pedestal that lives on mountaintops. She was covered in dewdrops, she had pastel veins. I thought I was hallucinating. I missed my wife.

I listened to Alan Watts’s The Wisdom of Insecurity on tape while I hiked. He told me that the root of all our problems is the desire to hold onto anything. Life is inherently flowing and our grasp to possess it makes us sick. I nodded and tried desperately to capture each beautiful thing I saw: I took a picture of the mist, of a toad, of a cairn; I took a time-lapse of a sunset, an audio recording of a grouse bleating for her chicks, six photos of the lady’s slipper orchid; I ripped up a tiny bouquet of meadow flowers—purple, yellow, and white—and stuffed them in an envelope to mail home.

I returned home to new words: apple and help. To the killing of George Floyd. To a city-wide curfew. I awoke one night to my wife saying, “Lulu. Out. Now.” She beelined down the hall to get our son. Our bathroom window was sunset-orange with fire outside.

“This is a communication,” I thought as I wondered what to take. I chose our laptops. And the scrapbook I have been making of my son’s life—his inky footprints, his finger paintings, his words.

The garage one plot over from us was razed. It was declared arson. No one was hurt. My son’s eyes gleamed at the fire trucks, five of them, the best night of his life. I thought about everything he didn’t yet know. I wondered how on earth we could raise him to be a good white man, to not think of himself as sitting on top of the hierarchy society continues to maintain for him.

In June, he began saying the word “up.” He began rejecting his beloved blueberries, throwing them on the floor. And I would—what would I do?—pick them up.

In July, we visited our sperm donor, a close friend who we’ve decided to call “uncle.” Our son’s face is his face but he has no word for him yet. His new word that month was “bus.”

In August, a tornado pushed through Chicago. Flying saucers of roots rose from the cement as the tree trunks fell. I sat in the bath with my son. The thunder was so loud it shook the car alarms awake. My son looked at me with “WTF?” eyes. I said, “Thunder.” “Hummer!” He said. And, I said, “Yeah. Hummer.”

In September, the wind rolled through, bearing cicadas and a chill. He turned two. His hot grew its t, his banana its b. He spoke his name out loud for the very first time. And no and corona.

And now it is October. The mysterious white creature I hung from the porch, my son quickly learned to call “ske-le-tah.” He calls the giant orange orb sitting below it “apple” and tries, in vain, to bite into it. Over the ridge of this month lies a greater unknown than we’ve seen in a while. How will the votes get counted, will the votes get counted, and if the president loses, will he stay? Will he even be there to refuse to step down? Will the social order hold, and wouldn’t that actually be the worse fate of all—if it did? Will there even be a month called November?

I am alone again. My wife and son are both asleep. I slip out onto the balcony. I can’t see the stars between the breaks in the clouds but I trust that they are there, because I have been told they are there. In honor of a more expansive world, in paving the path to progress through doubt, I let myself consider, for a moment, that there are no stars. I try to slip the word “star” off the stars, or to unscrew it, leaving just the sockets somewhere above me. I try to take down the word “above,” and consider that the stars might be below, or inside me. I roll my eyes at myself, while trying not to all the same.

Suddenly, the words of this essay melt into paint. Or maybe to felt. To wooden waves of green and blue. The colors are muted but deep. The fish curl into the stars, which curl into the wind, which forms a kind of tornado, at the center of which, you can see, is the soul, engulfing the earth, re-engulfing the soul. There is the sound of laughter. Which is rendered as a tiny bouquet of droplets off the tip of Antarctica. The word “Antarctica” is crossed out. The word “Antarctica” was never there. Ice melts from the brass pole around which the globe spins, then freezes. Then sublimates.

I would like to stay here. In the wordless place. After all these years looking closely at words, I have come to mistrust them. So often they are used as the sober blades to scale selves away from the group—its protection, its warmth, its assurances of justice. But something desperate in me still wants to hurl a handful of them out into the air, still believing that they could catch and tame a terrible thing.

“With a rising sense of mastery comes the fear of the unknown” is the pompous phrase I want to toss out into the night.

That night, back in April, when my son screamed out in terror, one might theorize that the reason for his fear was that he had awoken to an unfamiliar room, my in-laws’ guest room, and had become disoriented and afraid.

And yet, prior to lockdown, we had dragged that child all over the place. In his short life, he’d lived in three different homes, two different states. He’d awoken to countless unfamiliar rooms, inside friend’s homes and hotels (remember those?) and cars and bars and tents, and never before had it frightened him.

So what was different about that night? It was the first time he had awoken to an unfamiliar setting after the advent of words. For 569 days before that, he had lain with the unknown each night and it had never bothered or frightened him. Instead he had curled into her, this hulking, formless shoal of uncertainty and confusion, because it was all he knew.

It was only with the advent of words, with the illusion that he could name the whole world, every last corner of it labeled and known, that the unknown became an enemy, became a threat.

She’s flexing her wings this year, the unknown; she’s showboating around. She’s waving from the horizon in a coat of flames, she’s lingering on metal surfaces. There’s the same amount of her there always is, of course, but she’s making herself felt. Her presence can be seen in the whittling down of our teeth, the spikes in suicides, the surge in demand for therapists. Uncertainty, it has been shown, is more painful than certain physical pain. For some reason, the neurologists say, we are wired to fear the unknown. There is a thumbnail-size soldier in the brain, they explain, who they’ve named the Locus Coeruleus, who is charged with tracking uncertainty. He’s useful for a bit, they say; when faced with uncertainty, he puts the brain into a fluid state so it can better run through strategies to keep you safe. But when the uncertainty won’t let up, that fluid state starts to wear on the body; such extended vigilance leads to exhaustion, to a measurable increase in stress. “The strongest kind of fear is fear of the unknown,” declared H. P. Lovecraft, nearly a century earlier.

But what if they’re all wrong? What if we are not, in fact, fated to fear the unknown? What if that fear only starts with the advent of words, with the false belief that a named thing is a known thing? Perhaps it is our words that transform the hulking unknown from friend to foe.

It is a tidy theory.

It allows me to explain away the fear that something’s wrong with my child, that his anguish is unsolvable, unknowable. If I can name it, I can swat that haunting look in his eyes—when he no longer knew who I was—away forever.

*

With fish came every last creature on earth. The ducks are still ducks, but now owls are hoo-hoos. Both curbs and boulders are stone. He’s got fern and mushroom and umbrella and bus-truck. His chalk is cock, and the neighbors can’t stop laughing. The porpoises of the sea have all sprouted ruffled collars. “Doll-fish,” he says, animating the world with his wrongness, shaking them all temporarily awake.

A few weeks ago, I sat in the park, under a heavy beam of wood that could kill me in an instant. But I trusted it wouldn’t, because I had named that thing branch. In that same park, I watched a man, face twisted, run hard in my direction. But I trusted he would not kill me, was not running from a thing that might kill me, because I named him jogger. In that same park, dozens of ten-ton death machines whizzed by. I named them truck. I named the flat ribbon of asphalt road, and in road I trusted. With each word comes a false set of assurances. That now you know how it will behave.

“We have [the coronavirus] totally under control,” said the president the day after the first case was discovered in the U.S.

My friends, who are nurses, and married to each other, once told me a story about a woman who lay down in a hammock and felt the cinder block into which the hammock hook had been drilled slip out from its wall and land on her face and kill her.

With fish came the entire animal kingdom. Maybe I was wrong. Maybe there are a few left. He’s still got no word for cicada. He’s never named a firefly.

That night in the bath, so many moons ago—the same moon ago—the light gave off its last sparks of day, and he spoke his eleventh word. I heard it only as a mother. I clapped at all the finned creatures he had just caught in one syllable. I believed that he was drawing closer, each word a stepping stone thrown to walk him nearer, nearer to me. And yet the truth I knew even then, maybe, is that each word was another brick in the wall being erected between us. An experience named instead of shared.

I pulled the plug and watched as he watched, delighted, the water drain away. By the time it was gone, it was night. I wish, now, that I had lingered just a little longer, in the warmth of the water, in the waning days of wordlessness, when confusion was still everywhere, when confusion was still nothing to fear.

Lulu Miller is the co-host of Radiolab, the co-founder of NPR’s Invisibilia, and author of the book, Why Fish Don’t Exist. Her writing has appearing in The New Yorker, VQR, Orion, Catapult, and beyond.

October 2, 2020

Young, Queer, and Lonely in Paris

Sophie Yanow’s work of autofiction The Contradictions paints a portrait of the artist as a young, queer, lonely wanderer on a study-abroad trip in Paris. In the excerpt below, Sophie attends student orientation, drinks wine, and, based on a series of cues that feed into one another with the airtight logic of a geometric proof, zeroes in on potential companions.

Sophie Yanow is an artist and writer based in the San Francisco Bay Area. The Contradictions is her first book with Drawn & Quarterly, the web comic of which won an Eisner Award and was nominated for the Ringo and Harvey awards. Yanow is also the author of What Is a Glacier? and War of Streets and Houses. Her comics have appeared in The New Yorker, the Guardian, the Los Angeles Review of Books, and The Nib. She has been a MacDowell Fellow, and her translation of Dominique Goblet’s Pretending Is Lying received the Scott Moncrieff Prize for translation from French. Yanow has taught at the Center for Cartoon Studies, the New Hampshire Institute of Art, and The Animation Workshop in Denmark.

The Contradictions , by Sophie Yanow, was published in September. Excerpt courtesy of Drawn & Quarterly.

Staff Picks: Haiku, Hearts, and Homes

The writers featured in Two Lines Press’s Home: New Arabic Poets hail from Egypt, Lebanon, Palestine, Syria, and elsewhere, and all write with one eye turned toward the personal, the everyday, and the other toward the political. The result is unbelievably exciting, the kind of writing that makes you want to sit down at your desk and get to work. From Mohamad Nassereddine’s “Dogs,” translated by Huda Fakhreddine (“I want to write you / a love poem. / I search for language / for a tender word. / But words line up like trained dogs”), to Riyad al-Salih al-Hussein’s “A Marseillaise for the Neutron Age,” translated by Rana Issa and Suneela Mubayi (“We live in the neutron age / The age of quick kisses in the streets / And being utterly vanquished in the streets”), these are poems to read and reread, repeating the lines as though they were a secret between yourself and the page. —Rhian Sasseen

In the director Merawi Gerima’s debut feature, Residue, the anticipated anxieties of returning to one’s childhood home are pushed aside by a neighborhood made unrecognizable. Jay, the movie’s protagonist, is a filmmaker who is trying to write about home. But when he finds himself back in D.C., he discovers that he’s not the only one who has changed. Of all the things he felt unsure about, his neighborhood he expected to be the same. Jay attempts to reconcile his memories of home with the disorientation of a newly gentrified reality, the seemingly hostile takeover. The film is quiet, reserved, as if it knows better than to give too much. I can’t help but compare it with Joe Talbot’s The Last Black Man in San Francisco; both movies are about gentrification, community, and Blackness, but each is distinct. Less romantic than The Last Black Man in San Francisco, Residue asks essential questions about ownership and belonging. If you were the one who left, can you still be betrayed by the loss? —Langa Chinyoka

Laura Marling. Photo: Justin Tyler Close. Courtesy of Partisan Records.

Yet another musical train I am late to board is the one driven by the British singer and songwriter Laura Marling. People hipper than I am knew about her years ago, but I received her excellent seventh album, Song for Our Daughter, from my LP-of-the-month club, and I am just blown away. Marling is at least the second musician I have compared to Joni Mitchell (who is the keeper of, to paraphrase the poet James Richardson, the heart beneath my heart) in a staff pick, and she seems to be directly channeling the utterly exposed confessional lyricism and even the emotional aura of Joni’s music. On “Alexandra,” Marling sounds more like Ladies of the Canyon–era Joni than any artist I can think of, and that’s a really good thing. The songs are subtle and airy, full of soaring and plummeting melodies, and motored by delicious, clever percussion that takes up quiet residence in one’s hips, especially the danceable “Strange Girl.” The title track is a wary and hopeful ballad that will make any parent of a daughter—as well as any daughter—feel less alone. In this era of info flooding in through multiple inputs at once at all times, I’m grateful that people are still writing songs like this. —Craig Morgan Teicher

Natalia Ginzburg’s newly translated set of novellas, Valentino and Sagittarius, grapples with the struggles of having a difficult family and what loving them looks like in spite of their rudeness, idleness, or judgmental disposition. Imperfect marriages, bouts of fury, and superficiality never take away from the essential tenderheartedness of Ginzburg’s characters. In arguing for the necessary coexistence of our deepest humanity and our deepest flaws, these novellas gave me a renewed appreciation for those loved ones who are stuck with me throughout this pandemic. —Carlos Zayas-Pons

Most evenings around ten, when the work (or at least that day’s allotment of it) is done and the supper dishes are clean, I give myself an hour of free reading. It’s a category that might’ve previously been called pleasure reading, but given that this week I’ve been toggling between dystopias (Diane Cook’s disturbing, compelling The New Wilderness and the New York Times’s coronavirus coverage), the emotion is not quite delight. However, I have been pleased to recently encounter several intersections of bummer news and bright art. The Chronicles of Now may have been conceived before the news cycle became the raging dumpster fire we call 2020, but its model—short stories inspired by the news—is perhaps better suited than a CNN pundit is to helping us sort through this year. Meanwhile, the writer Etgar Keret and the choreographer Inbal Pinto have taken the cable news talking head and made it new: the dance between the isolated broadcaster and the equally lonely (and commendably loose-limbed) protagonist of the short film Outside is a canny response to the emotional landscape wrought by quarantine. And just in case we thought we were being novel in making art from news, I was glad to be reminded that Félix Fénéon was doing this 114 years ago in the Paris daily Le Matin: his collected Novels in Three Lines (translated and introduced by Luc Sante) demonstrates the artful possibility of the news with the economy of a haiku. Things might be bleak out there, but sometimes, they can also be beautiful. —Emily Nemens

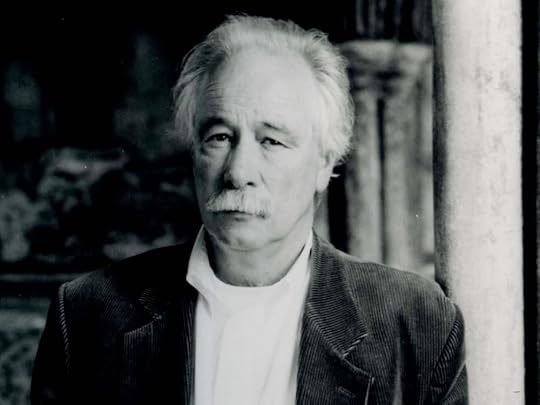

Félix Fénéon. Photo: Alphonse Bertillon. Public domain, via the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

October 1, 2020

The Later Work of Dorothea Tanning

Dorothea Tanning, Birthday, 1942. © ADAGP, Paris. Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Last week, I had the opportunity to visit the archive of the painter Dorothea Tanning, with whom my wife, the poet Brenda Shaughnessy, had had a twenty-year friendship, and who I had gotten to know toward the very end of her life. Dorothea, who died at a hundred and one in 2012, was profoundly intelligent, funny, mischievous, and in possession of her full creative powers almost until the very end. In her late eighties, when her hands were no longer steady enough to paint, she switched to poetry and published two extraordinary collections in her nineties. Her archive is housed in the Destina Foundation offices in downtown Manhattan. As I visited the space and spent some time with the work, I had a socially distant conversation with Dorothea’s archivist, Pam Johnson, who showed me some of the late works on display.

First a little background on Dorothea. She was born in Galesburg, Illinois, in 1910, and first gained notoriety in the early forties with what is still her most famous painting, the self-portrait Birthday. She made her way to New York as a young woman and fell in with the European surrealists who had fled the Nazis. One of them, Max Ernst, visited her studio in 1942 and was astounded by Birthday. That was the start of their thirty-four-year relationship and marriage, which would take them from New York to Sedona, Arizona, and to France, before Dorothea settled in New York after Ernst’s death in 1976. She began as a surrealist, as Birthday, with its winged monkey, endless doors opening into the distance, and botanical dress, makes clear, but the late paintings and fabric sculptures on view in her archives were ample evidence that she moved far beyond her beginnings, into realms for which I’m not sure there’s a handy label.

I’m not going to get into the scholarship around the paintings or say too much to contextualize them in terms of art history—for that, you might look to Dorothea Tanning: Transformations, a new book by scholar Victoria Carruthers, which surveys Tanning’s life and work and is filled with excellent reproductions.

Dorothea Tanning, Woman Artist, Nude, Standing, 1985-1987. © ADAGP, Paris. Photo by Bruce White.

Instead, I want to share what it felt like to be so close to Dorothea’s art, to come so close to the brushstrokes I could almost touch them with my eyelashes; to stand back and take in whole vast canvases. Dorothea was a painter whose ambition and achievement were not sufficiently recognized, and these late works are among her most formidable and distinctive. The bodies she depicted—distorted, sexual, fantastical, blending and dissolving into and emerging out of their charged surroundings—were always visionary, but she grew into an artist just as interested in the materials themselves. In these late paintings paint becomes corporeal, inseparable from the limbs, torsos, and disguised faces that hover across her canvases, like a vaporous imagination released into the atmosphere of a room.

Woman Artist, Nude, Standing, detail. Photo by Craig Morgan Teicher.

While she had her signature subjects (nude bodies, young women, dreamlike landscapes filled with symbolic objects and architecture), Dorothea was above all else an artist who never stopped growing. The works, like Birthday, for which she is best known are characterized by an almost photo-realistic surrealism, akin to the work of Ernst or Dali, and rooted in a kind of Pre-Raphaelite Romanticism. Over the course of her long career, her imagination merged with her medium, yielding unprecedented creations as much about the paint itself as about what she painted.

Dorothea Tanning, On Avalon, 1987. © ADAGP, Paris. Photo by Phoebe d’Heurle.

On her website, Dorothea is quoted explaining that the bright orbs in this painting “may have been flowers but also novas, tears, omens, God knows what, contending or conniving with our own ancestral shape in a place I’d give anything to know.” I love how this painting blends a kind of longing with a sense of ritual and work and nightmarish uncertainty.

Dorothea Tanning, On Avalon, detail. Photo by Craig Morgan Teicher.

Look at all that paint! Those brushstrokes flashing and undulating. It seems to me Dorothea accomplishes everything the abstract expressionists set out to do, but adds human (and animal) form and narrative, without giving anything away.

Dorothea Tanning, Door 84, 1984. © ADAGP, Paris. Photo by Phoebe d’Heurle.

This is a major work in her oeuvre, another late painting, on a large canvas. Two young women strain to keep a door closed—well, one strains, while the other … sits with resolve. A miasma roils around them, which I can only characterize as externalized inner life.

Dorothea’s work had always been obsessed with textures. In earlier periods, abstract textures were rendered with photo-realistic detail, arching and sinewing throughout the canvases. But in her later work, the paint itself, glopped and glomming, overtakes the will to depict: the painting and its subject are synonymous.

Dorothea Tanning, Tweedy, 1973. © ADAGP, Paris. Photo by Craig Morgan Teicher.

Dorothea also did a great deal of fabric sculpture. And she loved dogs, painting them often. Despite the obvious seriousness of her work, it’s also full of humor. I think this may be the funniest thing she made, though that may have something to do with the fact that my family recently got a puppy. My eight-year-old daughter cracked up when I showed it to her.

Dorothea Tanning, Evening in Sedona, 1976. © ADAGP, Paris. Photo by Bruce White

This painting was, in part, an elegy for Ernst, a depiction of Dorothea’s grief, of a sense of the world that was left. It’s a pretty apocalyptic vision, though it’s not without a certain kind of dark levity. Here her dogs are talismans, caretakers, and also the very environment in which the figure resides; she is inseparable from them, an aspect of them as much as they are an aspect of her. Again, the imagination is externalized, and the boundaries between bodies and surroundings are in the process of dissolving.

Dorothea Tanning, Evening in Sedona, detail. Photo by Craig Morgan Teicher.

What intrigues me most in this painting is the bit in this detail: the lightning etching its way out of or into the paint, the craggy mountains, a sort of castle, all of it merging with the fabric of the rest of the painting. What we feel, what we remember, what we want, what we need: inevitably, that’s what we see, and then try to see beyond, with more and less success, trapped by the imagination that frees us.

Craig Morgan Teicher is the digital director of The Paris Review and the author of several books, including The Trembling Answers: Poems and We Begin In Gladness: How Poets Progress.

Notes on Notes

August Müller, Liebesglück – der Tagebucheintrag (Detail), ca. 1885, oil on canvas, 12 3/4″ x 10 1/2″. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

When I think of books or works I love that reference the “note” in their titles, I begin to realize that it’s not the note as such that is the defining feature of these books, but the preposition that accompanies the word: Notes OF a Native Son; Notes ON Camp; Notes FROM Underground. In the first case, the weight falls on the particular subject position of the writer. What makes the note signify is the “Native Son,” James Baldwin, whose notes these are. In the second case, the phrase deflects our attention away from polemic even though the essay overflows with assertions. There is a certain authorial insouciance that becomes possible when I deign to publish my “notes on” anything, as if to say one can only claim such indefinite a phrase for a title if one is feeling very definite about oneself. But, then, to combine the “note” with “camp” is to ironize the note itself, decked out as an Oscar Wildean aphorism, and Sontag’s “notes on,” in this case, is more audacious than strictly philosophic. In the case of the marvelous Dostoyevsky title (and I have to say I don’t know how it sounds in the original Russian), the place from which the notes issue takes top billing, and this requires that we heed the type of notes these are (like those secreted in a bottle or furtively slipped through the chink in a wall); their intended recipient (surely not me, not you, but some accidental or imagined Other); and the ambiguity of their authorship (are they those we’d rather suppress, sent from unconscious to conscious? those scripted in a hand not our own but issuing through us? those that will tarnish the minute they hit the light of day or the piercing eye of the wrong recipient?).

Notes are never neutral.

Take the “extreme literary empiricism” of Georges Perec’s post-Holocaust, post–May ’68 An Attempt at Exhausting a Place in Paris (translated by Marc Lowenthal) alongside Dziga Vertov’s post–Bolshevik Revolution manifestos on the camera eye as an exceptionally attentive note taker. Both projects are underscored by a distinctive politics of noting, in the first instance of the “infraordinary,” or as Lowenthal describes it, “the humdrum, the nonevent, the everyday—‘what happens,’ as [Perec] puts it, ‘when nothing happens other than the weather, people, cars, and clouds,’” and in the second instance, of what Vertov calls “life caught unawares.” The constraint that Perec gave to himself was to return to the same Parisian locale over the course of three days, and to record “that which is generally not taken note of, that which is not noticed, that which has no importance.” A fastidiously observed record of quotidiana, the book erupts into a subtly divined poetry of all that slips past the surveying gaze of the omnipresent police.

Perec is always working within and against the de-realization of the Holocaust and its diabolic inventories. In this, I am reminded of Osip Mandelstam and how those few who survived him (at least fifteen hundred writers died under Stalinism between 1924 and 1953) held fast to the belief that someone had scrawled onto a labor camp wall a line from one of his poems, even though it was never clear where and when exactly Mandelstam died. That sentence read: “Am I real and will death really come?” Like Vertov working in a much earlier period, Perec’s hyperrealism is never hard-edged—it matches atrocity with ebullience, playfulness, and even laughter. For a politics of noting, there was none better than Vertov, whose dedication to visual phenomena only accessible to the camera eye had as its self-expressed aim “so that we not forget what happens and what the future must take into account.”

We come into the world handled, carried, and, it is hoped, caressed, passed from hand to hand to hand, and gaze to gaze, a life-giving relay that yields in time a painstaking and laborious self-configuration arrived at via endless forms of representation, all of them historically grounded and politically imbued; we learn, if you will, to see, and by extension, to know, think, and feel. Imagine having the audacity to try to alter characteristic modes of perception and discourse by way of your notational art as Perec, as Vertov, did, convinced that this is where political change begins.

Imagine how this requires that we do some noting about noting, that we study our relationship to how and what we note. To do that, let’s put to one side all the things we know about notes—for example, that they range in registers of mere mention to emphases, from enumerations to underscores—then climb a winding stair of counterintuitions, like:

that notes are the minima that constitute a life

that in the notebook everything is plagiarized and nothing is

that a note will never tell us if it aims to finish a thought or begin one, only that it wishes neither to complete nor conclude