The Paris Review's Blog, page 146

September 23, 2020

When Murakami Came to the States

In his rigorous new book, Who We’re Reading When We’re Reading Murakami, David Karashima examines how Haruki Murakami came to be one of the most beloved writers on the planet. The excerpt below chronicles the U.S. publication of Murakami’s first book to appear stateside, A Wild Sheep Chase.

The original Japanese and American covers of Haruki Murakami’s novel Hitsuji o meguru bōken (A Wild Sheep Chase).

On May 10, 1989, Haruki Murakami’s editor at Kodansha International, Elmer Luke, sent Murakami a fax reporting on the sale of U.S. paperback rights to A Wild Sheep Chase (to Plume for fifty-five thousand dollars) and asking him to take part in the promotional activities that were scheduled in New York that fall. Murakami declined. Several months later, Luke and Murakami met in person for the first time in Tokyo (together with another editor from KI), and on August 14, just three days before a copy of A Wild Sheep Chase arrived at the Murakamis’ home, Luke again asked Murakami to join him in New York. Murakami once again declined. On September 24, Luke asked again, saying that Murakami’s translator Alfred Birnbaum had become unable to attend, and that they had also managed to arrange an interview with the New York Times. Murakami finally relented.

Murakami and his wife, Yoko, landed in New York on October 21, and Luke and Tetsu Shirai, the head of Kodansha’s New York offices, picked them up at the airport. Shirai remembers handing Murakami a copy of that day’s New York Times folded open to a story in the arts section about him and A Wild Sheep Chase. The headline, “Young and Slangy Mix of the U.S. and Japan,” was followed by a tagline: “A best-selling novelist makes his American debut with a quest story.” “Of course, it was something that had been in the works,” Shirai tells me, “but I was surprised by how well the timing worked out.”

Shirai and Luke had chosen a hotel on the Upper East Side, thinking Murakami, an avid runner, would like to be near Central Park. Ten years later, Murakami would write in an essay for the women’s magazine an an that, while he preferred the Village and SoHo with its many bookshops and secondhand record stores, he ends up staying uptown in New York because “the appeal of running in Central Park in the morning is too great.”

Of the boutique hotels close to Central Park, the team at KI decided on the Stanhope Hotel. Luke says that he suggested the Stanhope, “which might seem odd (uptown, old-world-ish, maybe even stuffy, not hip or cool),” because it was the setting for The Hotel New Hampshire, by John Irving. When Murakami had visited the U.S. in 1984 at the invitation of the Department of Defense, he had interviewed Irving while jogging through Central Park with him. Two years later he had also translated Irving’s debut novel, Setting Free the Bears, into Japanese.

Murakami spent eleven days promoting his book in New York. Many of the interviews were conducted in KI-U.S.A.’s new office, which had a large poster of the cover of A Wild Sheep Chase on one of its walls. Anne Cheng, the publicist for KI-U.S.A., says that her most vivid memory of working on the book was “me trying to get this huge, glossy, bigger than life, poster reproduction of the book cover—that startling peacock blue background and the sheep in the foreground—to hang in our beautiful glass offices, next to the fresh ikebana arrangement that Mr. Shirai ordered for the entryway every week. There were a bunch of logistic and mundane details, but when the poster (almost five feet tall) was finally hung up, it was breathtaking and felt like a symbolic tribute to a book that was also larger than life.”

At the time, Murakami was already known for avoiding media attention. But during his time in New York, he agreed to an interview with Asahi Shimbun/Aera in which he told the reporter that he wanted to publish English translations of three of his novels, Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World, Norwegian Wood, and Dance Dance Dance, “at the rate of one book every year” as well as “short stories in magazines.”

In addition to individual interviews, Cheng thinks that there may also have been a book party at the Helmsley Palace Hotel. “I may not be getting the details right … I seem to remember—please double check with Mr. Shirai—we had a row of seven sushi chefs making exquisite fresh sushi to order. It was a wonderful event.”

Shirai has no recollection of the Helmsley Palace event, but tells me it may simply have been that he hadn’t attended and that KI-U.S.A.’s business manager, Stephanie Levi, would have a better idea. Levi says that she does remember a big party at the Helmsley Palace, but isn’t sure either whether it was for A Wild Sheep Chase or not. When I ask Luke about this, he laughs. “No way! Really? Would be amazing if it were true. True, they could have had it and I wasn’t there. I mean, the Helmsley Palace was a pretty big deal back then. If Gillian [Jolis, marketing director for KI-U.S.A.] were alive, she’d be the one to know. The Seven Sushi Chefs. Sounds like a parody of a Japanese film.”

A private party was also held at the Levis’ apartment, attended by the Murakamis, Kodansha staff, and researchers from Columbia, as well as the editor Gary Fisketjon and the literary agent Andrew Wylie, who, according to Stephanie’s husband, Jonathan Levi, were “the only two Americans [he] knew who had heard of Murakami” and who were “both very keen to work with him.” One guest recalls coming back into the living room after being given a tour of the Levis’ apartment to find Andrew Wylie still talking to Murakami. The Murakamis left the party early, saying they had plans to go to a jazz club.

Luke also accompanied the Murakamis on visits to bookstores. A Wild Sheep Chase, he says, was prominently displayed in Three Lives, “a terrific independent store in Greenwich Village that was my favorite—and that, many years later, would host midnight opening parties on publication dates of Murakami books.” Luke says that Murakami may have signed books, but that no public events were planned. It would be another couple of years before Murakami would do his first ever public event with Jay McInerney at the PEN America Center.

“Haruki was excited, though guardedly, not effusively, in his Haruki way … We (KI) were careful about overdosing him with publicity, and he was a bit shy about availing himself, but he was willing to participate. Not as guarded as he is now.”

In the afterword of his 1990 collection of travel writing, Tōi taiko (Far-off Drums), Murakami shared his impressions of the New York trip, writing that although it had been some time since he had last visited the city, he “did not feel especially out of sorts,” and that while he would never want to live in New York, the fact that people were direct “in some ways made it less uncomfortable than Tokyo.” Nearly thirty years later, Murakami tells me that he “remembers the response in New York being especially big.” When I show him the New York Times review with his photo on it, he laughs and says, “I was a lot younger back then.”

*

The New York Times review that appeared on the day of the Murakamis’ arrival in the city had been written by Herbert Mitgang, who had been at the paper since immediately after World War II. Mitgang wrote that A Wild Sheep Chase was a “bold new advance in a category of international fiction that could be called the trans-Pacific novel.” He continued:

This isn’t the traditional fiction of Kōbō Abe (“The Woman in the Dunes”), Yukio Mishima (“The Sailor Who Fell From Grace With the Sea”) or Japan’s only Nobel laureate in literature, Yasunari Kawabata (“Snow Country”). Mr. Murakami’s style and imagination are closer to that of Kurt Vonnegut, Raymond Carver and John Irving.

Mitgang also emphasized that “there isn’t a kimono to be found in ‘A Wild Sheep Chase.’ ” Actually, a kimono does appear in the novel, when the protagonist visits the Boss’s residence and an “elderly maid in kimono entered the room, set down a glass of grape juice, and left without a word.” But there is a chance that Mitgang was influenced by the description on the book jacket: “The setting is Japan—minus the kimono.”

Mitgang concludes by stating that “what makes ‘A Wild Sheep Chase’ so appealing is the author’s ability to strike common chords between the modern Japanese and American middle classes, especially the younger generation, and to do so in stylish, swinging language. Mr. Murakami’s novel is a welcome debut by a talented writer who should be discovered by readers on this end of the Pacific.” After Mitgang’s review appeared, Yomiuri Shim-bun—the Japanese broadsheet with the largest circulation in the world—published an article headlined “US Newspaper New York Times Lauds Haruki Murakami.”

Mitgang’s was the first of many reviews that placed Murakami in contrast to the “Big Three” postwar writers in Japan: Yasunari Kawabata, Yukio Mishima, and Jun’ichiro Tanizaki. In the Washington Post, the novelist and journalist Alan Ryan wrote, “Readers who treasure the refined sensibilities of Kawabata and Tanizaki, the grand but precisely etched visions of Mishima, or even the dark formalities of Kōbō Abe, are in for a surprise when they read Murakami,” and went on to say that he was not surprised to learn that Murakami had translated authors such as F. Scott Fitzgerald, Paul Theroux, Raymond Carver, and John Irving. Ryan also suggests that “Murakami echoes the state of mind of the ordinary Japanese, caught between a fading old world and a new one still being invented, willing to find magic but uncertain where to look.”

Not everyone was thrilled by Murakami’s arrival on American shores. One of the least enthusiastic reviews was by another Japanese novelist. Foumiko Kometani had received the Akutagawa Prize (an award for emerging writers that Murakami was short-listed for twice but never won) in 1986 for Sugikoshi no matsuri (translated into English by the author as The Passover). In her Los Angeles Times review, “Help! His Best Friend Is Turning Into a Sheep!,” Kometani criticized the narrative voice of A Wild Sheep Chase for “sound[ing] more like a black Raymond Carver or a recycled Raymond Chandler or some new ghetto private eye than a contemporary Japanese novelist” and suggested that his readers in Japan are “people who have taken their places sheep-like on the conveyor belt of Japanese society as salaried men and housewives, but still like to harbor images of themselves as cool and hip and laid-back, sophisticated and aware, and, yes, above all, Western.”

Kometani was a translator herself (she translated not only her own novel into English but also her husband’s nonfiction books into Japanese), and her otherwise scathing review is kind to the translator: “Not that Alfred Birnbaum’s excellent translation has not gotten Murakami’s sentences down exactly right.”

Many of the other reviewers were also complimentary about the translation. In the New York Times, Mitgang noted that “the novel is racily translated from the Japanese by Alfred Birnbaum.” Ann Arensberg went further in the New York Times Book Review: “Without question, [Murakami] has help from Alfred Birnbaum, who seems more like his spiritual twin than merely his translator.” When I ask Birnbaum what his initial reaction had been on reading these positive reviews, he says, “Disbelief, but I more keenly remember one bad review that cited ‘Birnbaum’s tin ear.’ ” (I was unable to locate this particular review, but a review in the Washington Post stated that “Alfred Birnbaum’s translation constantly jars with its odd sentence structures, punning chapter titles, colloquial Americanisms, Britishisms, and at least one Boston-ism.”)

One review seemed almost to predict what lay in store for Murakami. In The New Yorker, the novelist and poet Brad Leithauser wrote that the book “lingers in the mind with the special glow that attends an improbable success” and that “[i]t is difficult not to regard A Wild Sheep Chase as an event larger even than its considerable virtues merit … Many years have elapsed, after all, since any Japanese novelist was enthusiastically taken up by the American reading public—and this may soon be Murakami’s destiny.”

Leithauser, who has published eight novels and six poetry collections with Knopf and is currently a professor at Johns Hopkins, had lived in Kyoto in the early eighties. He tells me that he “wasn’t terribly surprised” by Murakami’s success. “It seemed clear to me from the first that he was bringing something new to Japanese literature. There’s a peculiar lightness in what he’s doing that should not be confused with any lack of seriousness … I think to Western eyes Japanese literature is apt to seem light in another sense—in its sparsity. This is certainly true of Kawabata. And this sparsity is for me one of the great appeals of Japanese literature. But I’m talking here of a different kind of lightness, an antic and lyrical and sunny quality. I tend to love writers who have this quality. Calvino (one such writer) is much more articulate than I’m being in his essay on lightness versus heaviness. I’m thinking he (Calvino) would have admired him (Murakami).”

David Karashima has translated a range of contemporary Japanese authors into English, including Hitomi Kanehara, Hisaki Matsuura, and Shinji Ishii. He coedited the anthology March Was Made of Yarn: Writers Respond to the Japanese Earthquake, Tsunami, and Nuclear Meltdown and is the coeditor of Pushkin Press’s Contemporary Japanese Novellas series and Stranger Press’s Keshiki series. He is an associate professor of creative writing at Waseda University in Tokyo.

Copyright © 2020 by David Karashima, from Who We’re Reading When We’re Reading Murakami . Excerpted by permission of Soft Skull Press.

September 22, 2020

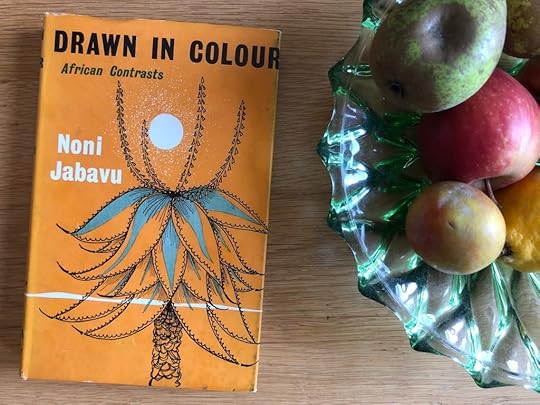

Re-Covered: An Unconventional South African Novel

In her column, Re-Covered, Lucy Scholes exhumes the out-of-print and forgotten books that shouldn’t be. This month, she examines a South African writer whose unconventional work has often been left out of the canon.

Photo © Lucy Scholes

When, in 1961, the long-running English literary magazine The Strand relaunched as The New Strand, it made newspaper headlines across the world. Although the London-based periodical had an illustrious history—founded in 1891, it counted the likes of Arthur Conan Doyle (whose Sherlock Holmes stories debuted in its pages), Agatha Christie, and P. G. Wodehouse among its contributors—its reinvention was hardly breaking news. What was, though, was the identity of its new editor: Noni Jabavu, the Black, South Africa–born writer, journalist, and broadcaster. A woman editor would have been surprise enough, but appointing a Black woman was unheard of at the time. Ernest Kay, joint proprietor of The New Strand (with the crime novelist John Creasey), defended this “bold and imaginative” choice in the press. “Miss Jabavu has led such a varied life that she will bring a completely fresh outlook to the magazine,” he told Ebony in April 1962. “She couldn’t be conventional if she tried.”

Jabavu’s life had certainly been anything but orthodox. She was born Helen Nontando Jabavu, in 1919, in Middledrift, a small town in the Eastern Cape, into a Bantu Christian family. Like her father before her, Jabavu was educated in Britain. From 1933, she attended the Mount (the famous Quaker boarding school in York, which counts another subject of this column, Margaret Drabble, among its alumnae), and afterward the Royal Academy of Music in London. But instead of then returning to South Africa like her father had, Jabavu remained in England. By the time she started at The New Strand, she had been based in the UK for over two decades. She was the mother of a teenage daughter (from her first marriage, to an RAF man killed in World War II); the wife of an upper-class, white Englishman (the film director Michael Cadbury Crosfield); and an established broadcaster and writer, newly famous for her book Drawn in Colour: African Contrasts (1960). The fact that this had been published by John Murray (one of the UK’s most established and respected publishing houses) to both rave reviews and impressive sales (it was reprinted five times in its first year) was all the more noteworthy because Jabavu was the first Black South African woman to publish a book in the UK. In 1962, both Italian and American editions appeared, and the following year Jabavu published a sequel, The Ochre People: Scenes from a South African Life. Drawn in Colour’s notoriety turned Jabavu into a “public literary figure,” explained the poet Makhosazana Xaba in The Johannesburg Review of Books last year: “The case of a black African woman, a British citizen by marriage, being published by a mainstream publisher so long before the advent of a distinct, feminist British women’s press that only began in the eighties was certainly an oddity for many a Briton.”

“This honest, searching analysis reveals to us the Africa still largely hidden to European eyes,” said The Tablet, recognizing that Jabavu’s bicultural identity was central to Drawn in Colour’s success. “I belong to two worlds with two loyalties,” Jabavu explains in the author’s note: “South Africa where I was born and England where I was educated.” As such, she was the perfect cultural mediator for her white British readers—lest we forget that this was the audience to which the book was marketed. She eloquently explains, for example, that isiXhosa is a language of emotion—“expressive, forceful, not Biblical as some writers lead you to think, more like Elizabethan English; words are pliable, can be manipulated and therefore impregnated with subtle, often startling shades of meaning; and ‘from the shoulder’ yet poetic in allusion and illustration”—or perceptively ponders “how profoundly custom—isiko—is based on psychological need.”

Despite its sensational beginnings, Jabavu’s editorship at The New Strand was ultimately short-lived. Discovering that she was much happier as a writer than as an editor, she resigned after only eight months. Afterward, she returned to her globe-trotting life, not settling in South Africa until 2002, by which time she was eighty-three years old. Jabavu was an anomaly in many ways. Everything about her—from her upbringing to her achievements, even the way she lived her life—transgressed so much of what was understood by the terms “African” or “Western/European.” As the academic and writer Athambile Masola notes: “Jabavu drifts in and out of the South African grand narrative of what it means to be a black woman anything. Jabavu drifts in and out of the identity politics that seeks to homogenise what it means to be black in South Africa.”

*

Drawn in Colour is an account of Bantu culture, as seen through the eyes of someone who straddles the line between insider and outsider: a native daughter who finds herself back in the bosom of her family after an absence of over twenty years. It is not a didactic compendium, though; instead, as the blurb on the dust jacket says, it’s “a personal story about the author’s family.” Today we’d classify it as travel writing or memoir. In elucidating episodes in the present, Jabavu dips into the past in the form of recollections of her childhood, stories about extended family members, or broader observations about the customs, languages, and history of the continent of her birth. Nevertheless, the narrative is tightly structured around a central event: the trip home that Jabavu made, in March 1955, on the occasion of her brother Tengo’s murder. He was twenty-six years old and a medical student in the final year of his degree at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg when he was shot dead by gangsters. Jabavu attends the funeral, thereafter spending the requisite period of mourning in seclusion with her family, after which she travels north, to visit her married sister, who lives in Uganda with her husband and their baby and was unable to attend Tengo’s funeral. As various family members explain to Jabavu before sending her on her way, it’s her duty to help her sister “re-live every phase of our tragedy … It will be only if you, eldest of the umbilical cord, properly fulfil your function that your sister will find the peace that we have found through these traditional rites.”

In Drawn in Colour, the racism of the country jolts through Jabavu the minute she arrives in Johannesburg:

As soon as I stepped out of the plane with its relaxed international atmosphere, I could feel the racial atmosphere congeal and freeze round me. The old South African hostility, cruelty, harshness; it was all there, somehow harsher than ever because Afrikaans was now the language. You heard nothing but those glottal stops, staccato tones; saw only hard, alert, pale blue eyes set in craggy suntanned faces.

But as the narrative continues, its only one of many threads. Jabavu wasn’t penning the kind of South African protest literature that would soon become prominent. As Masola notes, Jabavu is often omitted from lists of prominent Black South African women who wrote in exile during apartheid. And yet, though her exile might not have been strictly “political,” as was the case with some of her peers—contrast her with Miriam Tlali, another previous subject of this column, for example—Jabavu was writing and publishing in Britain during a period when it would have been impossible for her to do the same in South Africa, and her marriage to Crosfield would have broken the country’s miscegenation laws.

Jabavu takes an instructive tone, or quietly appeals to the reader’s humanity. Take her account of her widowed father’s second marriage, which takes place after the mourning period for Tengo is over. The ceremony is a small affair conducted by a magistrate in a nearby settlement where, despite the significance of the occasion and the elegance of their dress, Jabavu and her new stepmother are forced to “walk to a deserted part of the town close by and squat in the short grass,” because the lone public lavatory for women is for “Europeans”—whites—only. Rather than directly express her anger, Jabavu simply lets the jarring image shock the reader. Later, while Jabavu is traveling through Rhodesia, a white woman behind the counter in a chemist’s refuses to sell her sanitary towels, telling her to “Go ’n get whatever you people use in yer own native shops, go on, get out.” Jabavu points out, “This is a matter that should hardly figure in one’s story. But some readers may not realise the levels at which the colour bar is liable to make itself felt if you are black.” The academic Alice A. Deck draws comparisons between Drawn in Colour and Zora Neale Hurston’s Dust Tracks on a Road (1942), arguing that they’re written with a similar aim: “To demonstrate the basic humanity of their peoples to an audience of readers living outside of the particular communities under scrutiny.” In both, Deck explains, “cultural explication and personal narrative intertwine in such a way that either discourse may subordinate the other at any given moment.” One of the things that makes Drawn in Colour so compelling is precisely this calibration; namely, the ease and perspicacity with which Jabavu switches between impassive eyewitness and emotionally engaged filtering consciousness.

Jabavu’s sojourn in Uganda functions as a further point of comparison against which she can assess her own culture. She and her fellow Southerners have, we learn, always thought of their Northern brothers and sisters with reverence—“those of our people who were fortunate enough to be beyond the reach of racialistic Boers seemed blessed creatures indeed.” These are Africans who own their own land and are in charge of their own lives. “Go you now therefore and look on our behalf,” her uncle tells her. “And when you write, uplift us with eye-witness reports of civilised Africans, for they are said to be all that we here in the South are not.” What she finds, however, is a culture of such “disparate social observances and manners” that life in Uganda actually seems significantly more “primitive” than that which Jabavu is used to. In contrast to Southern Bantu culture, she is surprised by Ugandan attitudes to polygamy, concubinage, and what’s considered incest; and in contrast to her Western mores, she is surprised by the lack of modern hygiene and the proliferation of disease and malnutrition. “I thought how one hated, in South Africa, to see rough local ‘Europeans’ in their dealings with other races,” she writes.

I was not to know then that before much longer in the country my sister had married into, I too alas, would be compelled to adopt the hectoring manner when dealing with “the natives,” a terrible inevitability arising out of people not beginning to understand or identity themselves with one another or appreciating different habits of life.

Jabavu’s uncomfortable inspection of her own beliefs could be read as a clever means of bringing a white reader face-to-face with their own prejudices, or it could be read as a dangerous validation of those intolerances. “This whole business of feeling impelled to try to ‘like’ and ‘be nice to those natives I knew’ was a dilemma,” Jabavu continues. “To my dismay I saw I was now in the same boat as those whom we Southerners call slightingly ‘liberals,’ meaning white people whose brain and sense, education and conviction tell them there’s no reason not to like us blacks; but whose emotions are rooted, as evidently mine were too, in an instinctive revulsion from a way of life more primitive than their own.” Reviewers in both the UK and the U.S. praised Jabavu’s candor: “It may be a wry comfort to those Westerners who have found Africa dismaying and disappointing,” wrote Thomas Lask in the New York Times, “to learn that it can be equally so to Africans.”

It’s perhaps worth noting, though, that Jabavu’s notions of what was considered “primitive” and what was considered “civilized” had long been colored by her composite bicultural identity, the roots of which actually lay much deeper than in the British citizenship she adopted as an adult. As Masola explains it, Jabavu’s heritage “reveals an interesting nexus of family connections and the tale of African modernity and colonialism in the nineteenth century,” and to fully understand her beliefs, one must understand her life.

*

The world Jabavu describes growing up in, not to mention that to which she returns in the mid-’50s, is perhaps best described by Deck as “Xhosa–British Victorian.” Jabavu’s grandfather was a teacher turned journalist who, in 1894, became the editor and owner of the first African newspaper, Imvo Zabantsundu (Black opinion). His son, Jabavu’s father, was a professor of Latin, Bantu languages, and social anthropology, and a founding member of the academic staff at Fort Hare, the college for higher education that his father had helped lobby for. Jabavu’s mother, meanwhile, was a prominent social worker and organizer, and her sisters (Jabavu’s maternal aunts) were equally impressive: one was the first Black registered nurse in Africa, and the other the first Black woman to work as a journalist. “Like so many so-called Westernised Southern Bantu families,” Jabavu explains in Drawn in Colour,

we were bound to behave in a proper manner, according to the dictates of the life old and new, the essence of our African life which outsiders tend to interpret as “spoilt by Europeanisation.” In fact it is neither spoilt nor improved, it is simply different from what it used to be because of the elements from English and Boer life which have impinged on us.

Jabavu’s identity was complicated: “We were not ‘black Europeans,’ yet I saw how we were not ‘white Bantu’ either.”

Nothing about Jabavu was conventional. And as a consequence, she was both privileged and on the periphery. As Masola asks:

What does it mean for Jabavu to leave South Africa in 1933 as a 13-year-old and move to Britain … to study further? What does it mean to be married to an upper-class Englishman as a black woman in the 1950s? What does it mean to work as a writer, BBC presenter and film technician at that time? What does it mean to come home to an apartheid South Africa in 1977 to discover you are a foreigner in the country you call home?

Despite their initial success, both Drawn in Colour and The Ochre People have fallen out of print in the UK and the U.S. This is the unfortunate yet unsurprising fate of a great many excellent books. It’s much more of a travesty that Jabavu’s books have never been widely available in South Africa, the country whose literary awards body recognized her accomplishments by presenting her, in 2005 (only three years before she died, in 2008, at the age of eighty-eight), with a lifetime achievement award.

In the late seventies, Jabavu was given a brief visiting fellowship at Rhodes University; she’d returned to South Africa to research a biography of her father (which sadly remains unpublished). While there, she also began writing a weekly column for the Eastern Cape newspaper the Daily Dispatch, under the title Noni on Wednesdays. “By the end of the year,” Xaba explains, “Noni was a household name: her readers’ letter box was overflowing and her 3 months fellowship at Rhodes University had caught the curiosity, imagination and interest of many.” Yet despite Jabavu’s fast-growing fame, neither of her books was available in the country. Raven Press would eventually publish The Ochre People, five years later, in 1982 (two whole decades after it first appeared), but somewhat astonishingly, Drawn in Colour has yet to find a South African publisher. Thanks to the tireless work of both Xaba and Masola, this could soon change. Not only is their recent scholarship bringing Jabavu to the attention of a younger generation, they’ve joined forced to produce Noni Jabavu: A Stranger at Home—a collection of Jabavu’s much loved Daily Dispatch columns, along with an introduction to her extraordinary life and work—which will be published in February 2021. As Masola astutely writes, “Jabavu’s work isn’t significant because she’s one of ‘the firsts’; her work is relevant because it continues to ask difficult questions about what it means to be human beyond the limitations and impositions of identity.”

Read earlier installments of Re-Covered here .

Lucy Scholes is a critic who lives in London. She writes for the NYR Daily, The Financial Times, The New York Times Book Review, and Literary Hub, among other publications.

Redux: Each Rustle, Each Step

Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

W. H. Auden.

This week at The Paris Review, we’re walking, both alone and with friends. Read on for W. H. Auden’s Art of Poetry interview, Jamaica Kincaid’s short story “What I Have Been Doing Lately,” and Mary Szybist’s poem “Walking in Fast-Falling Dusk What Is between Us Besides.”

After you’re finished, mark your calendar for our forthcoming Fall issue launch, on September 23 at 6 P.M. (ET). This free virtual event will feature several Fall issue contributors reading from their work: Rabih Alameddine, Lydia Davis, Emma Hine, and Eloghosa Osunde. For more information and to RSVP, please visit our events page.

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, and poems, why not subscribe to The Paris Review? Or, to celebrate the students and teachers in your life, why not gift our special subscription deal featuring a copy of Writers at Work around the World for 50% off? And for as long as we’re flattening the curve, The Paris Review will be sending out a new weekly newsletter, The Art of Distance, featuring unlocked archival selections, dispatches from the Daily, and efforts from our peer organizations. Read the latest edition here, and then sign up for more.

W. H. Auden, The Art of Poetry No. 17

Issue no. 57, Spring 1974

Later, I realized, in constructing this world which was only inhabited by me, I was already beginning to learn how poetry is written. Then, my final decision, which seemed to be fairly fortuitous at the time, took place in 1922, in March when I was walking across a field with a friend of mine from school who later became a painter. He asked me, “Do you ever write poetry?” and I said, “No”—I’d never thought of doing so. He said: “Why don’t you?”—and at that point I decided that’s what I would do. Looking back, I conceived how the ground had been prepared.

Photo: User:Fb78. CC BY-SA 2.0 DE (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...).

What I Have Been Doing Lately

By Jamaica Kincaid

Issue no. 82, Winter 1981

What I have been doing lately: I was lying in bed and the doorbell rang. I ran downstairs. Quick. I opened the door. There was no one there. I stepped outside. Either it was drizzling or there was a lot of dust in the air and the dust was damp. I stuck out my tongue and the drizzle or the damp dust tasted like government school ink. I looked north. I looked south. I decided to start walking north. While walking north I decided that I didn’t have any shoes on my feet and that is why I was walking so fast. While walking north I looked up and saw the planet Venus and said, “It must be almost morning.”

Image from the Nationaal Archief, the Dutch National Archives, via Wikimedia Commons.

Walking in Fast-Falling Dusk What Is between Us Besides

By Mary Szybist

Issue no. 227, Winter 2018

this sharpness of pines, this gravel loose

beneath us, faltering with each rustle, each step, with what we’re not

saying to each other—Now your flashlight’s beam angles

into the thickness, dead petals the color of light honey

unfasten from their coppery centers, dark berries shine

clustered above twig tips, above forked edges of leaves, above

everything unnamed between us I have

not forgiven—still overflowing toward us while still

arrested, suspended, in all the shadows

of everything I don’t know how to feel …

And to read more from the Paris Review archives, make sure to subscribe! In addition to four print issues per year, you’ll also receive complete digital access to our sixty-seven years’ worth of archives.

Editing Justice Ginsburg

An editor recalls the experience of working with Justice Ginsburg to bring an unpublished memoir to print.

Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States. Photographer: Steve Petteway

“I would like to be helpful,” Ruth Bader Ginsburg wrote me on February 1, 2002. “The problem is time.” She said she would be away from Washington for eight days. “We could discuss your request the following week.”

The “request” was that she write an introduction to a book I was publishing a few months later. I was a youngish editor at Random House, overseeing the Modern Library, our classics imprint. The book had come to me because of her. With her letter she enclosed two lectures she had written, one given three years earlier; the other she would deliver during her upcoming travels. “Perhaps a Random House editor could suggest a way to draw from the talks to compose an introduction.”

Of course I volunteered myself.

In 1999 Justice Ginsburg delivered the Supreme Court Historical Society’s annual lecture. “The rooms and halls of this stately building are filled with portraits and busts of great men,” she said, according to the prepared remarks she sent me. “Taking a cue from Abigail Adams, I decided, when asked to present this lecture, it was time to remember the ladies.”

Ginsburg focused her lecture on the wives of four supreme court justices from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, an idea first proposed by a former law clerk, Laura Brill. Researching the topic with the help of the Library of Congress, Ginsburg and Brill came upon an unpublished memoir by Malvina Shanklin Harlan, the wife of Justice John Harlan, member of the court from 1877 until his death in 1911.

Justice Harlan, who came from a Kentucky family with a long history of enslavement, is now best remembered as the lone dissenter in Plessy v. Ferguson, the 1896 decision that codified the separate-but-equal doctrine that would undermine and terrorize the daily lives of Black Americans until the civil rights movement of the sixties. Malvina Harlan witnessed her husband as he deliberated over this and other momentous opinions, recording with keen observation these turning points in the life of her family and her nation. Her manuscript, completed in 1915, was about two hundred typescript pages, edited and annotated by hand, suggesting to Ginsburg that Malvina Harlan had hoped to find a publisher. She called her book Some Memories of a Long Life, 1854-1911.

“Malvina’s memoirs are full of anecdotes and insights about contemporary politics and religion, the Supreme Court, and the Harlan family,” Ginsburg said in her lecture to the Historical Society. “They provide an informative first-hand account of the life of a judicial spouse in the closing decades of the 1800s. Sadly, no publishing house considered Malvina’s Memories fit to print.” Ginsburg would later write that she was drawn to the manuscript as a chronicle of the country before, during, and after the Civil War “as seen by a brave woman of the era.”

Like Malvina Harlan before her, Justice Ginsburg hoped to see Some Memories published. Ginsburg spent many months trying to find a publisher—“to no avail.” (I still wonder who rejected her.) She turned to the Supreme Court Historical Society’s Journal, circulation six thousand, which devoted its Summer 2001 issue to publishing the memoir in its entirety. Shortly after, Linda Greenhouse wrote about Malvina Harlan, and Justice Ginsburg’s efforts to bring attention to her life and writings, on the front page of the Sunday New York Times.

I was in my apartment in Manhattan when I read that story. I recall the mental buzz every editor experiences when encountering something he or she wants to publish. I rode my bike seventeen blocks north to the Random House office in an electrified state. Almost ninety years after Malvina Harlan had hoped to see her memoir in print, I wanted to be her publisher. I saw it as an opportunity not only to work with Justice Ginsburg, but to shed light on a historical figure who pressed as close to the seats of American power as her society and the laws of the time would allow. I’ve long been interested in the unjustly ignored or forgotten, those whose lives were so far ahead of their day that only the future could resurrect them. I hunted the internet for a fax number at the Supreme Court and wrote Justice Ginsburg. (Sending RBG a blind email seemed impossibly forward; as I would later learn, she didn’t use it.)

A few days later a medium-size cream envelope landed in my mail slot. On the back flap: “Chambers of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg.”

“Glad to know of the Modern Library’s interest,” she wrote, putting me in touch with the Historical Society. Not long after, Random House acquired the publishing rights from Malvina Harlan’s descendants.

On a conference call with the justice to discuss the publication, I said how much I admired Harlan’s manuscript and her skills as a chronicler. “Yes,” she said. I commented on Justice Harlan’s unlikely evolution from a family of enslavers to the lone dissenter in Plessy. “Yes.” The more enthusiasm I expressed, the louder Justice Ginsburg’s silence. I turned to the schedule and other publication details. “Fine,” she said. “That should be fine.” I was still finding my way as a book editor—my own long career at Random House lay ahead of me. I wondered if I was making a fool of myself, or had said something to offend her. In fact, I was experiencing Justice Ginsburg’s intense, now famous, listening. At the end of the call she thanked me and said everything sounded fine. Later I would learn this was her adjective of appreciation.

Since Ginsburg’s death, like so many others I have reflected on her far-reaching impact—on women’s rights, American jurisprudence, and our society more broadly. I’ve also thought of another aspect of her legacy: her words. Yes, the words from the bench that have become familiar—her scathing line about “skim-milk marriage” when listening to arguments against marriage equality, for example. Or the must-reads of her dissents, such as in Ledbetter v. Goodyear. But I’m also thinking of the words she wrote outside the court that might give us a glimpse into how she viewed her own long life, set against the context of her era.

Justice Ginsburg crafted an introduction out of those two lectures. I gave her some notes, “suggesting a way,” but she had written her talks with such certainty of purpose that almost any editor would know what to do with the material. On the page her voice is the same as the one Americans came to know and revere, and that we now mourn: precise, concise, unyielding; fearless, factual, and so often focused on the marginalized. Justice Ginsburg used her voice to create opportunities for millions—this is one reason her death is painful for many of us. We reflect on those opportunities and are fearful some might close up as a result of her absence.

Justice Ginsburg also created opportunity for Malvina Harlan. Ginsburg viewed Harlan not merely as a spouse at the court’s periphery, but as someone whose own experiences and interpretations we should value, alongside but also separate from those of her husband. If not for Ginsburg, Malvina Harlan’s written work would remain all but unknown; the manuscript would be curling in the dim depths of the Library of Congress. It fascinated me that Justice Ginsburg sought to elevate Malvina Harlan’s life and recognize her contributions. It’s similar to much of Ginsburg’s legal career, both at the bar and on the bench—she never stopped trying to assign value to the lives American systems and institutions had long diminished.

In one of the lectures she sent me to edit, Justice Ginsburg tells us about Sarah Grimke, a South Carolina feminist and abolitionist who visited the Supreme Court in December 1853. The court wasn’t in session that day and Grimke boldly sat in the chief justice’s empty seat. “As I took the place,” Grimke recalls in a letter to a friend, “I involuntarily exclaimed: Who knows, but this chair may one day be occupied by a woman. The brethren laughed heartily[.] [N]evertheless, it may be a true prophecy.”

A prophecy, Ginsburg writes, “I believe will indeed prove true.”

Some Memories of a Long Life was published in May 2002, with Justice Ginsburg’s introduction. When I sent her the finished copies, she wrote in a fax, “Thank you for today’s special pleasure—the chance to spend some time with one of the first copies of Malvina Shanklin Harlan’s memoir.”

For writers and editors, it’s a profound, almost spiritual moment when you hold a new book for the first time. It is the physical manifestation of years of work and struggle, carrying with it many blows and scars. It’s also, in many cases, an artifact of a fight that has been won, or at least not lost. It is hope made tactile via ink and paper. I thought of the hope Malvina Harlan must have felt as she worked on her manuscript in her final years. I thought of the vast changes in society for women since her day, represented here in the words of the wife of a nineteenth-century Supreme Court justice, and in those of her introducer, our country’s second female justice.

Then every editor’s nightmare.

“I noticed a small slip,” Ginsburg continued, “which perhaps can be corrected in later copies. At page 209, 6 lines from the bottom, the second word should be ‘school’ not ‘firm.’”

We didn’t meet until the book party at the Supreme Court in honor of Some Memories and the spouses of the justices. Justice Scalia greeted folks at the reception door with a drink in his hand. I made my way over to Justice Ginsburg. She was wearing black lace gloves and I recall the webby feeling of lace as I shook her hand. You already know how small she was. How muted the voice. You already know how certain she was of herself, while also seeming to be shy.

I said I hoped many people would read Some Memories. She said she hoped they would, too. I said none of this was possible without her—a fact so obvious her only response was a humble nod. Then I said what I had wanted to say for many months, and that I assume many had said to her before and would say to her for years to come: I hoped one day she would write her own memoir.

Over the next days and weeks, months and years, many words about Justice Ginsburg will come forth, but the words I most want to read today are hers. She must have had many memories of a long and historic life, and I wish we could read them now in her own telling. The rigorous thinking, the exactness of language, the empathy, the humility, the sprinkles of irony and wit—I wish she had applied her linguistic gifts to her own story, just as Malvina Harlan had to hers.

“Have you ever thought of writing a memoir?” I asked clumsily at the party.

Justice Ginsburg didn’t answer directly. Instead, she smiled vaguely, but also coyly, with a flash in her eye. I’ve never forgotten that gleam. I’ve held onto it as a promise. Since then I have often wondered if another unpublished manuscript is waiting for us somewhere. If the typescript pages have been edited and annotated by hand, anticipating their moment. I hope so, as unlikely as it sounds. But if no memoir exists, Justice Ginsburg has already left us with what we want to know, perhaps not about her but about ourselves. History is made individually and collectively, she instructed, and even in this ill year the choice about our future remains ours.

David Ebershoff is a writer and editor. At Random House he edited books that won the Pulitzer Prize in fiction, biography, and history. His novels include The Danish Girl, which was adapted into an Oscar-winning film, and the New York Times best seller The 19th Wife, which was adapted for television.

September 21, 2020

The Art of Distance No. 26

In March, The Paris Review launched The Art of Distance, a newsletter highlighting unlocked archive pieces that resonate with the staff of the magazine, quarantine-appropriate writing on the Daily, resources from our peer organizations, and more. Read Emily Nemens’s introductory letter here, and find the latest unlocked archive pieces below.

“It’s back-to-school time. This year, of course, that doesn’t mean everyone is actually going back to school. Many students and teachers are attending class from one side or another of the same screen that for months has been their primary aperture on the wider world. Some schools and universities are still completely remote; others have managed to bring students back in some capacity. And so this new school year begins with a roiling mix of excitement, trepidation, anxiety, and hope, for students, parents, teachers, and staff. No matter the situation, it’s not the same as a bunch of students sitting together in a room, carefree enough to focus solely on what they’re learning. But I like to think there are some aspects of education that can be practiced no matter where and with whom one finds oneself. Literature can offer deep, reflective engagement with the thoughts and feelings of others; a kind of call-and-response across space and time that is not unlike conversation; and opportunities to (safely) visit near and faraway places. In that spirit, this week’s The Art of Distance features interviews that celebrate education. ‘Singing school,’ as W. B. Yeats called it, is always open and available to all. May you find these interviews as enriching, enlightening, and sociable as a good school day. And let’s meet up by the lockers after third period.” —Craig Morgan Teicher, Digital Director

Photo: Douglas P Perkins. CC BY (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...).

Unsurprisingly, writers have high regard for education, though also, nonconformists that they are, great ambivalence about it. But all the writer-teachers of this asynchronous virtual master class believe strongly in the dialectic encounter that can take place in a classroom or in conversation with a text. Please raise your hand if you have any questions.

Early in his writing life, the Nobel laureate Kenzaburo Oe set himself a kind of lifelong homeschool curriculum, as he explains in the Art of Fiction no. 195: “When I was in my twenties, my mentor Kazuo Watanabe told me that because I was not going to be a teacher or a professor of literature, I would need to study by myself. I have two cycles: a five-year rotation, which centers on a specific writer or thinker; and a three-year rotation on a particular theme. I have been doing that since I was twenty-five. I have had more than a dozen of the three-year periods.”

Toni Morrison explains, in the Art of Fiction no. 134, the high bar she sets for her students: “When I teach creative writing, I always speak about how you have to learn how to read your work; I don’t mean enjoy it because you wrote it. I mean, go away from it, and read it as though it is the first time you’ve ever seen it.”

In the Art of Fiction no. 52, Bernard Malamud attests to the two-way street of education: “Schools meant a lot to me, those I went to and taught at. You learn what you teach and you learn from those you teach.”

“One of the things I love about teaching at Syracuse,” says George Saunders in the Art of Fiction no. 245, “is that you meet class after class of talented young people, and it makes you an optimist. And you get to give that kind of student a sort of lineage advice—you get to pass on to them ideas like, Yes, you are responsible for every single line. You are. No one else will be.”

Finally, there’s Robert Hass, who in the Art of Poetry no. 108 acknowledges problems with higher ed but professes his love for the academic life: “There are many things wrong with the university as an institution, but it’s been the place for me. I love the idea of people studying everything and experimenting in labs with everything. To be part of that enterprise has always seemed to me like a gift.”

Sign up here to receive a fresh installment of The Art of Distance in your inbox every Monday .

First Mothers

What if instead of a singular hero, we had many?

Queen Nanny as she appears on Jamaica’s $500 bill

I have been fascinated by Queen Nanny of the Jamaican Maroons for years. In fact, I have been trying to write about her since I graduated from college. The Maroons were communities of fugitive slaves and free Black people, some who, after the British took the island from the Spanish in 1655, fled to the mountains, and others who later escaped British plantations to join them. They resisted for eighty-four years. The Leeward Maroons, led by Cudjoe, and the Windward Maroons, led by Nanny, waged the first Maroon War from 1728 to 1739. Despite their small numbers and lack of military equipment, they raided plantations for supplies, liberated enslaved people to reinforce their ranks, and killed more white people than were able to kill them. The Maroons successfully prevented the British from expanding into Jamaica’s interior until they negotiated a peace treaty and land allotments to each of the different factions on the island. The free towns they established at the end of the First Maroon War still exist today.

Nanny was declared a national hero in 1976. Her face was put on the Jamaican $500 bill. I had a rudimentary understanding of her story growing up, but the first time I saw her depicted in fiction was in Michelle Cliff’s novel, Abeng, which I read as an undergrad. Nanny’s story is part of a buried history of Jamaica that the heroine, Clare Savage, a light-skinned and middle-class Jamaican, isn’t taught. As a consequence of that ignorance, Clare is raised to uphold a system of colorism and white supremacy. Cliff takes the beginning of Nanny’s story directly from Maroon legend: “In the beginning there had been two sisters, Nanny and Sekesu. Sekesu remained a slave. Some say this was the difference between sisters. It was believed that all the island’s children descended from one or the other.” Unlike Sekesu, Nanny “carried the secrets of magic into slavery,” which she used to free herself and others. Cliff confers a moral purity on Nanny that she denies Sekesu.

Cliff describes Nanny preparing for war, cowrie shells in her hair. Later, when Nanny meets with the leader of the Leeward Maroons, the “only decoration was a necklace fashioned from the teeth of white men.” Nanny was known for being a military strategist and though in legend she emerged from the kingdom of the Ashanti, in Cliff’s telling Nanny draws her knowledge of battle from the “Dahomey Amazons,” the Mino of Benin, an all-female army in the Kingdom of Dahomey. Nanny was known for being a powerful spiritual leader, an “obeah woman,” and Cliff describes her as a master of disguise who stuns soldiers with her spells. She even recounts a popular legend where Nanny is known to have stopped bullets with her ass.

But Cliff’s Nanny never speaks. She never becomes a fully realized character. So I thought, I could do that. And then later I thought, Who am I to think I can write this? Still, I’ve tried over the years, picking up the project and abandoning it. Nanny is a historical figure of huge proportions, but the written record about her is minimal. In Cliff’s version, after being betrayed by Cudjoe, who refuses to join forces, she is killed by William Cuffee, a “Black shot,” hired by the British to fight in Black militias against the Maroons. It is documented that Cuffee tried to claim a reward for her murder in 1733, but there is no other mention of her death in written texts. In fact, there are three more written references to Nanny in the seven years that follow and they demonstrate that she was still alive.

Though I haven’t lived in Jamaica since I was five, the allure of Nanny feels personal. Her story provides a reprieve from the nearly constant theater of Black pain and suffering that is the history of the Americas we’re taught. At a time when Black women on the island were seen as easy prey for white men (such as, for example, Thomas Thistlewood, a plantation manager and owner who recorded every slave woman he raped over a thirty-seven-year period in his diaries), Nanny was a woman who became famous for terrorizing white people.

Like Clare Savage in the novel, I’d been taught to react to acts of injustice with politeness. My mother would scold me if I spoke badly of my father, even behind his back, even though my anger was because I’d seen him beat her. What did it even look like for a woman to rebel with violence? Part of my interest in that question and in Nanny was stirred when I took a trip to Jamaica in college. I went to their rural town in the mountains to meet my paternal grandparents for the first time. Like the Maroons, they still lived as subsistence farmers. Their part of town had no streetlights. I had never experienced such suffocating darkness, but my grandparents could move around without even a flashlight. During the day, I saw my grandmother, who was rail thin and diabetic, disappear into areas of dense vegetation holding a cutlass and emerge with something for me, bananas or a piece of sugarcane. I had a vision, then, for Nanny. The drawings of Nanny I’d seen looked more like my grandmother, with her hair always tied with a plain white headwrap, than like Cliff’s Dahomey Amazon warriors.

On that same trip, I met a cousin whom I hadn’t seen since I was a child, but who had since been disfigured by a vat of acid thrown on him by his wife. He later forgave her; they’re still together to this day. I listened to adults talk about him as if he were mad and about her as if she were evil. Later, when I saw her in person, I noticed some relatives were polite to her face but whispered about her when she was out of earshot; others shunned her outright. I never found out what my cousin did to stir her anger, but I had witnessed men do unspeakable things. And I had been expected by the women around me to be quiet and forgive them for it. In Jamaica, I kept seeing glimpses of the matrilineal society in which Nanny lived, quickly obscured by misogyny. Sekesu was the victim; I knew her well. Nanny was the hero who I wanted to be. But I didn’t know how, so I started imaging her.

After college I worked at a public defender’s office doing fund-raising, but also paralegal tasks like answering letters from prisoners seeking a lawyer to handle their appeals. The letters were desperate and described a level of brutality that haunted me. One of the first letters was from a woman who said she was being raped by prison guards and punished for speaking out by being locked in a solitary housing unit. I started writing about Nanny as a way to counteract feelings of complete helplessness. I didn’t save any of my early drafts. I learned later that for me to connect to characters that I’m writing, I need to put a real piece of myself into each of them. But back then, I was writing about Nanny because she was everything that I wasn’t.

On my trip to Jamaica, the year before, I had read excerpts from Karla Gottlieb’s biography of Nanny, The Mother of Us All, in a bookstore in Norman Manley International Airport in Kingston while waiting for my flight home. I skimmed through and landed on the description of Nanny that Philip Thicknesse, a British captain who fought in campaigns against the Maroons, had written in his memoir. He called her the “Old Hagg,” and described her as wearing “a girdle around her waist … with nine or ten different knives hanging in sheaths.”

In my version I had her carry a cutlass for protection and foraging, but I didn’t believe the version of her that Thicknesse described. Gottlieb had deemed it an exemplary piece of “exotica,” a style of writing typically used by white men at the time to write about nonwhite people. Still, even the version I wrote of Nanny didn’t feel quite human. What I had learned about obeah growing up centered around fear, never liberation. My most superstitious aunt taught me to track the hair I shed, my nail clippings, even to count my underwear because all of it could be stolen and used by your enemies to work spells against you. But obeah was instrumental in resistance to slavery and its practice was outlawed on plantations. I didn’t understand Nanny’s version of obeah, but in my writing, it became Nanny’s tool for violence. I didn’t employ the kind of magical realism I would later use in my first novel. Nanny was just magical. Bullets were shot at her, as in legend, but they didn’t pierce her flesh. She could make trees shift and move, use magic to generate a kind of piercing noise that made only white men’s ears bleed. In reality, her power came from her knowledge of guerrilla warfare, tactics like forest camouflage. Her incantations were more likely blessings that fortified her people’s courage as they went into battle. In historical accounts, the Maroons reportedly used noise to disorient and intimidate British troops while attacking them—yelling, banging on drums, blowing horns like the abeng (made from a cow horn). But my version drew from legends about Nanny’s exceptional ability rather than from corroborated historical accounts and oral histories. My Nanny was flat, a representation of all the violent things I wanted to do in this world because I felt weak.

*

When the pandemic began, I found it hard to focus on the novel I’d been writing, set in a present day that no longer exists, so instead I tried to write about Nanny again. I ordered Karla Gottlieb’s The Mother of Us All and read it in its entirety. According to Gottlieb’s research, in 1740, the British granted Nanny and her people land. William Cuffee couldn’t have killed her in 1733. Cudjoe did sign a peace treaty on behalf of the Leeward Maroons, but so did Quao, a leader of the Windward Maroons who in some oral histories is Nanny’s brother and was described in Thicknesse’s memoir as having deferred to Nanny’s orders. Both treaties specify that the Maroons have to hunt down and return escaped slaves, as well as fight alongside the British in the case of a slave rebellion.

After the treaty, the Maroons became enforcers for white slave owners. Michelle Cliff includes this truth in her novel but absolves Nanny from blame by declaring her dead. But the land granted as a result of the treaty in 1740 was written to “Nanny a free Negroe and the people under command.” The real story blurred the line between the two sisters in the legend—Sekesu, who accepted her own slavery and the doctrine of white supremacy, and Nanny, who because of her exceptional abilities supposedly rejected it outright. I was no longer sure if I wanted to write a book about a figure like Nanny, who was inspiring but also deeply problematic. I thought that it was the end of my project.

I’ve lost the urge to put all my faith in a single hero. Throughout the uprisings this summer, I’ve watched a mass movement of people fight to dismantle white supremacy, together, as a collective force. In her book, Gottlieb suggests a possibility that there might have been more than one Nanny. The name is an anglicized version of the Ashanti word nana, a title of respect given to leaders and elders, and the word ni, meaning “first mother.” In British Jamaica, Nanani became Nanny. William Cuffee might have in fact killed one Nanny, only to have another rise up and become more powerful. In Thicknesse’s memoir, he described seeing the Windward Maroons’ “Obea women,” multiple women, wearing the teeth of dead British soldiers strung together as “ankle and wrist bracelets.”

I’ve decided to write about more than one Nanny; the one who died in 1733 and the one who lived. I’m writing about another woman, Akua, who in oral history was elected by other slaves as the “Queen of Kingston,” and was one of the architects of Tacky’s War, a slave rebellion in 1760 that the Maroons were instrumental in suppressing. What strikes me most about all of these women is not how exceptional they were, but how, together, they exposed how weak white supremacy was. British forces on their own weren’t strong enough to defeat the Maroons. They needed “Black shots,” like William Cuffee, and when they failed, they tried importing Miskito Indians from Central America. People from both companies kept deserting to join the Maroons, making their ranks even stronger. The planters and slave masters who encroached on Maroon territory lived in fear. Nanny became our hero, but even when she failed, other women kept resisting. The idea that there is a beginning and an end, a single leader and a single traitor to a movement, is an illusion. Even Sekesu may have resisted. Female slaves resisted exploitation by men like Thomas Thistlewood by running away whenever they had the chance, when they couldn’t fight. “Nanny” could have acted like a protective cipher, a label for a moving target, while the many women who struggled to bring forth the empire’s collapse went about their work, unnoticed but no less powerful for it.

Maisy Card holds an M.F.A. in Fiction from Brooklyn College and is a public librarian. Her writing has appeared in Lenny Letter, School Library Journal, Agni, Sycamore Review, Liars’ League NYC, and Ampersand Review. She is the author of These Ghosts Are Family.

The Now

Photo: Jim Pickerell. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

When I was a teenager I was, like most teenagers, preoccupied with the idea that somewhere on the horizon there was a Now. The present moment came to a peak out there; it achieved a continuous apotheosis of nowness, a wave endlessly breaking on an invisible shore. I wasn’t quite sure what specific form this climax took, but it had to involve some concatenation of records, poems, pictures, parties, and behavior. Out there all of those items would be somehow made manifest: the pictures walking along in the middle of the street, the right song broadcast in the air every minute, the parties behaving like the poems and vice versa. Since it was 1967 when I became a teenager, I suspected that the Now would stir together rock ’n’ roll bands and mod girls and cigarettes and bearded poets and sunglasses and Italian movie stars and pointy shoes and spies. But there had to be much more than that, things I could barely guess. The present would be occurring in New York and Paris and London and California while I lay in my narrow bed in New Jersey, which was a swamplike clot of the dead recent past.

At the time I had been in the United States less than half my life and much about it was still strange. I constantly found myself making basic errors about social practices and taboos. My parents certainly couldn’t help me—they understood even less. There wasn’t really anyone I could ask who would answer my questions and not make fun of me. Through force of necessity I had become adept at amateur anthropology, deducing the ways and habits of the Americans from the semiotic clues they threw off in their relentless charge through the twentieth century. I read every piece of paper I could get my hands on. I became a big fan of mimeographed bulletins, local advertising circulars, political campaign literature, obsolete reference books, collections of antediluvian Broadway wit, hobbyist newsletters, charity solicitations, boys’ activity books from the thirties, travel magazines entirely cooked up in three-room office suites on Park Avenue South, and the Legion of Decency ratings in the weekly newspaper of the Archdiocese of Newark.

Every month I devoured Reader’s Digest, paying particular attention to the rubrics devoted to humorous anecdotes submitted by readers, because I was intent on figuring out how humor worked. I also pricked up my ears every time I heard Americans laughing, because it meant I might be able to glean a story that would earn me five bucks. (I never did, which in itself taught me an enormous amount about humor.) While I hated Catholic school, I treasured the reading matter the nuns threw at us: Dick and Jane books, missionary propaganda, gruesome martyrologies, slim collections of poetry edited and published by the Sisters of Charity. They were gold mines of data. Some of our textbooks were thirty or forty years old, with pictures that showed boys wearing plus fours and girls with oversize bows in their hair, and they were interestingly territorial. I particularly relished the story of Johnny, who had Protestant friends who goaded him constantly about his faith and were determined to get him to eat a meat sandwich on a Friday. Johnny finally succumbed, and on the way home he was run over by a streetcar.

Gradually I built up my store of knowledge. I was beginning to get a feel for the way people used language as a tool to pound nails with, and I dimly began to comprehend power relations and kinship patterns and the yawning gaps between ideal and actuality in the American project. Not that I could have accounted for those things in so many words, of course. It would be decades before I understood power relations as they affect just two people sitting at a breakfast table—and actually I’m not sure how much I understand them even now—but at least I could begin to arrange large color-coded bins in my head into which I could toss sundry items from the surrounding culture as they crawled across my purview.

Then, all of a sudden, came the Now. I discovered the Now at a specific time, in seventh grade, but it didn’t come from anywhere in particular. It arose from the ground. It was maybe hormonal. It was exciting and a little frustrating, because a whole new continent had lain under my nose for years without my getting wise, while sundry doofuses were all over it—anybody who had an older sibling was hep from on back. Before I had even begun to think about it they already had the clothes, the moves, the music. In order to catch up I went so far as to ride the chartered bus to Asbury Park in the snow for an away basketball game just to observe them in the field. But the scene was depressing and the gleanings scant. I wouldn’t make the same mistake twice. Henceforth I would stick to primary sources.

And for me that meant printed matter. I had to locate the parish bulletins of the Now, and the very first item I found seemed to answer to that description. In the local musical-instrument store lay a stack of Go magazine, free take one. Go was a grimy newsprint tabloid with color covers underwritten by record companies. It was strictly a booster sheet, very likely much of it cut-and-pasted from Billboard and Cashbox. It recorded, for example, the professional excitement aroused by the signing of four high school graduates from Marquette, Wisconsin, doing business under a name that made them sound vaguely British, to a record company in Pittsburgh with a name that made it sound vaguely familiar. That happened to be nearly the last point when the market was sufficiently porous to allow a chance at the big show to such collections of hopeful nonentities from nowhere, some of whom occasionally did make good, if briefly, and then their picture might appear in an advertisement that covered some portion of a page in Go. With its antenna turned at least in part toward the small-time, Go was in a position to educate me in certain detailed ways, chiefly concerning nomenclature and image. Of course, some of the information I derived from Go I could have gotten from Tiger Beat, but didn’t because that was for girls. I became familiar with photographic conventions that required teenage hoodlums and seasoned lounge lizards alike to pose as if in a perp lineup, sandwiched uncomfortably between grinning rack jobbers and promo men, while the caption alleged that they were in fact taking a break from their busy schedule. Go, founded and edited by Robin Leach, later of Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous, was as resolutely chipper as it was fundamentally cold, but even though it might as well have been chronicling supermarket openings or innovations in the automatic garage-door industry, it managed to convey some particle of the Now.

I had no money to speak of in that period—my weekly allowance had been frozen some years earlier at fifty cents—so my sources had to be gratis, via promotional handouts, shoplifting, the public library, or else Center Stationers, with its heavily laden magazine rack partly concealed from the cash register by a display of pipes, so that I could stand there and read things cover to cover as long as I kept an eye in the back of my head. I hadn’t yet encountered George Orwell’s observation that the contents of a small newsagent’s shop provide the best available indication of what the mass of people really feels and thinks, but I sensed something of the sort. The display contained magazines for every conceivable interest, it seemed, every hobby, every political affiliation, every affinity group. But there were no magazines targeting forward-looking young people who lived in or at least aspired to the Now.

There weren’t, that is, until a day early in 1968 when I spotted the first issue of Eye. This was no skimpy, low-budget rag with murky pictures, but rather a glossy, brilliantly colored coffee-table object nearly the size of Life. It was put out by Hearst, which knew a thing or two about marketing. They knew, for example, to include a poster in each issue, as well as plenty of send-in-the-coupon offers to obtain delightfully Now items absolutely free. I surreptitiously tore out a few of those coupons from the issues at Center Stationers, and thus was able to receive in the mail, after a four- to six-week interval, a 45-rpm flexidisc on which the Yardbirds touted the merits of an instant-milkshake powder, for instance. In this way Eye commanded my loyalty, so that I was barely disconcerted by the rest of the magazine. What Hearst knew about magazines had been gleaned from years of laboratory experiments at its Cosmopolitan franchise, which meant that Eye involved much lifestyle advice, many photographs of lissome young models of both sexes engaged in groovy leisure-time activities—flying kites, say—and covers studded with numerals: “10 Student Rebels Explain Their Cause”; “Test Your Mind’s 9 Electric Dimensions”; “Add 5 Sexy Years to Your Face With a Mustache.”

In September 1968 I began commuting to New York City every day, since I’d gotten a scholarship to a boys’ high school run by the Jesuits on the Upper East Side. Suddenly I was on the threshold of the infinite. It did not take long before I started wandering though the city, after school at first and then, increasingly, during times when I should have been in class. I once got off the train at Bleecker Street because I had heard its name in a song, but nothing much seemed to be happening. Then I walked along Eighth Street, MacDougal Street, St. Mark’s Place, Second Avenue, looking into the numerous poster shops and head shops and record shops and bookstores. There were leatherware shops and health-food restaurants and people’s clinics and a place that served ice cream flavors named after types of marijuana, and featured a long row of Hell’s Angels bikes parked outside. In between all those places were pork stores and bakeries and haberdasheries and shoe repairs where the normal business of the neighborhood went on as usual, involving people who were not young and assumed it would all go away eventually. I passed the Electric Circus and the Fillmore East, and people stopped to try and sell me drugs that I was pretty sure were fake. I wore a jacket and tie and carried a briefcase.

I had a million questions I couldn’t even frame as questions, which resolved into a single glowing orb of curiosity. My only recourse, as ever, was printed matter. In New York, this presented a challenge of its own. I was familiar with compiling information from scraps; here I was faced with a glut, a mountain of newsprint in a bewildering variety of forms. The newsstand huts that stood on seemingly every other corner, more or less identical at first glance, turned out to display sometimes wildly varying stock. Some sold academic journals; a number dealt in porn; you had specialists in foreign languages or hobby publications, in dream books or the rags of sundry left factions; a string of them sold underground newspapers. Those papers looked different even from a distance, often gaudy, often chaotic, often amateurish, and they made the newsstands jump with carnival colors. They only cost a quarter or thirty-five cents, so I began checking out the titles from all over the country that appeared irregularly, one month the Chicago Seed, the next month the LA Free Press, another the Berkeley Barb, this in addition to the local papers, the East Village Other and Rat.

When I actually started leafing through them I was nonplussed. It wasn’t that I had any problem with the ham-fisted layouts, the rough-and-ready typesetting, the photographs that invariably looked nine generations removed from the original image, the contrast between the thirties-infused comix and the aspirationally psychedelic illustrations, the nudity that I knew would cause me to have to abandon the paper on the train since my mother regularly searched my room, or even the occasional random use of color, such as printing whole patches of text in yellow, making it unreadable against a white background. The trouble was that I couldn’t read them anyway. The papers were written in a foreign language as far as I was concerned. I understood politics only in a visceral way—I was firmly against the war and in favor of the revolution, but I couldn’t have told you why beyond the fact that the first was odious and the second sounded like fun, although perhaps I had already absorbed the phrase “historically inevitable.” I could read the underground papers insofar as I could scan a page and herd the items under headings: over here was Vietnam, across the page was police brutality, down at the bottom was pot, or “dope” as it was called then. Beyond that, my vaunted text-mining skills abandoned me.

Yet I had seemingly arrived at the very gates of the Now. You could not possibly get more Now than those papers, published by rebel youths who had cut all ties to the mainstream, who ate and drank and slept revolution, who were the harbingers of that new world that would be coming around as soon as the entire demographic wave turned twenty-one. But the contents of the papers bore little resemblance to what I was led to expect by my preliminary investigations into the Now. The world they depicted was nothing at all like the psychedelic pleasure garden I had nebulously imagined. There were no glamorous personalities and no girls in floral minidresses; there was no music in the air and no spontaneous poetry on street corners. But I had started commuting to New York City a mere week after the Chicago Democratic convention, and whatever the mood may have been a few months earlier, by the middle of September it was very dark. “Resistance” was beginning to outpace “revolution” as a key word. A few correspondents were signing off with the phrase “armed love.” It was a run-up to the apocalyptic phase that began a year or so later, and it appeared that already there were people acquiring weapons, preparing for stand-offs. Were the pigs poised to make blanket raids on communities? Had internment camps been secretly built in the Mojave desert? People were starting to flee the cities in little groups, moving to abandoned farms, aiming for self-sufficiency. The ones who remained would soon be getting ready for war.

I was able to take the temperature of the papers I looked at, but my reading skills lagged principally because there was so little that matched up with my experience of life. What I most readily understood were the windiest bursts of rhetoric, which gave an unfortunate impression. But the hard news with its figures and acronyms might as well have been algebra, and approaches to practical matters appeared before my eyes as impenetrable blocks of gray text. What could a fourteen-year-old make of legal counsel, however sound and clearly articulated? And what about the medical advice? References to crabs and yeast infections just sounded vaguely culinary and not at all serious. But then even the food columns were beyond my ken. The very helpful section in the Seed that listed all the food options you could get for a dime, and the addresses of the markets where they could be procured, held no more meaning for me than if it had been written in Polish. My parents, who were grooming me as best they could for an adulthood they hoped would be very different from theirs, had taken care to shield me from knowledge of life’s exigencies.