The Paris Review's Blog, page 145

September 30, 2020

A Modernist Jigsaw in 110 Pieces

Aerial view of the Munich Residenz after bombings, 1945. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Wolfgang Koeppen’s novel Pigeons on the Grass, first published in 1951 as Tauben im Gras, is among the earliest, grandest, and most poetically satisfying reckonings in fiction with the postwar state of the world. What have we done to ourselves? What may we hope for? Is life from now on going to be different? Is it even going to be possible? These are the unasked and unanswerable questions that hover around this great novel composed in bite-size chunks, a cross section of a damaged society presented—natch!—in cutup. I once described it as a “Modernist jigsaw in 110 pieces,” but it is as compulsively readable as Dickens or Elmore Leonard. The form catches the eye, but the content is no slouch either. It must be one of the shortest of the universal books, the ones of which you think, If it isn’t in here, it doesn’t exist.

The setting is Munich, a place to which Koeppen had first come toward the end of the war. It is where, in his own words, he “lay low and made himself small,” where he met Marion Ulrich, his much younger wife (they were married in 1948), and where he lived until his death in 1996, at the age of almost ninety. More to the point, it is “the little town out of which death sprawled over the classroom map,” as Joseph Brodsky calls it, the epicenter of the developments that an Austrian corporal and failed watercolorist had initially set in train with the Munich Putsch of 1923, developments that, it is calmly suggested near the end of the novel, might be on the point of getting going again. Amid the destruction and the rebuilding, the novel, set in that same 1948, is looking for early signs of a pattern. Is the cycle of violence, exhaustion, and resentment about to get going again, as happened after World War I (as Koeppen, born in 1906, knew very well from personal experience); or is there some higher meaning in it, as Mr. Edwin the visiting poet-intellectual would have us believe; or is there perhaps no meaning at all, is it all random patternlessness, “pigeons on the grass,” as Gertrude Stein wrote, or, as she is ignorantly—and rather well—paraphrased by Miss Burnett, the visiting Massachusetts schoolmistress: “the birds are here by chance, we are here by chance, and maybe the Nazis were here by chance, Hitler was a chance, his politics were a dreadful and stupid chance, maybe the world is a dreadful and stupid chance of God’s, no one knows why we are here, the birds will fly off and we will walk on”?

Into this place and this time, caught as we have been almost entirely since—with the small exception of the nineties, when the world briefly promised to be “unipolar” and history to have “ended” (with whatever different hellish consequences that might have had)—between hope and despair, divided in two or more armed camps, enduring or soliciting occupation of one kind or another, engaged in small-scale conflicts or preparing for the Big One, blithely or grimly minding our own business or sleepless with fear and disgust, Koeppen introduces his dramatis personae of Germans and Americans, of soldiers and civilians, white people and Black people, women and men, young and old, celebrities and nonentities, greater and lesser villains. (Who is “good” here? Maybe Hillegonda, maybe Washington, maybe Philipp? But nothing is made of it—it’s not an interesting category. We are crooked timbers. We crash singly, we crash together, and we crash en masse.) Elsewhere, Koeppen writes of the same period and the same atmosphere:

In those days, war and peace hung in the balance, only we didn’t know. We didn’t hear about the cataclysm that threatened us until much later, in newspapers that hadn’t yet been printed. Whoever could, ate well. We sipped our coffee and our brandy; we worked hard to earn money, and if the circumstances were favorable, we slept with one another.

Recollecting London at much the same time and in much the same condition, the painter Frank Auerbach has remarked: “There may be some feeling of that turmoil and freedom in those pictures that there was in London after the war. There was a curious feeling of liberty about because everybody who was living there had escaped death in some way. It was sexy in a way, this semi-destroyed London. There was a scavenging feeling of living in a ruined town.” Metaphorically, or in microcosm—and, coincidentally or not, there is just such a scene in Pigeons on the Grass—we are standing at a set of lights—probably, come to think of it, a rather recent development for 1948—waiting for it to be “our turn.” “Fates, conspire,” says John Berryman.

After that, it is just a matter of threading and linking incident, cueing the pieces, plotting the entanglements, devising the superconducting phrases or tropes that will end a passage and—via a misunderstanding, it has been pointed out, in some different sense, almost homonymically—begin the next one. People live their lives, confront or ignore their difficulties, head off toward—another phrase from Koeppen’s later novel Death in Rome—“the next fraudulent little transaction.” (The condition of civilization is too rudimentary for honesty to be a policy at all.) Some of these have more carry, more scale, more applicability, some less; but to the characters, and to the book, they are all there is, they all come alike, and they are all the same size. There is not a central plot and flanking subplots, a principal figure and subsidiaries; everything is in equal measure major, everyone gets their moment in the book’s light and dark, its night and day. In their sum, they are the totality of existence. Everything teeters and winks, dangling its binary yes/no. It is in the balance. It will come about, or it won’t. Fates, conspire: Frau Behrend wanting her coffee and her groceries; Ezra the stray dog; Alexander the “great actor” a little peace; Washington a life somewhere with Carla and their baby carried to term; Hillegonda salvation; Emilia a sale; Susanne a night to remember, or at least not to forget; the astonishing narcopathic Schnakenbach his magic formula; Josef the price of a drink; Mr. Edwin (who seems maybe three parts T. S. Eliot and one part Auden or Spender) the success of his talk and a piece of rough trade afterward. And so on, and so on.

The book is a panopticon (much like Dylan Thomas’s Under Milk Wood from 1953), and it tells the stories of people in all their myriad circumstances wanting love, or maybe to be comforted. Koeppen is effortlessly all-seeing, all-knowing. Nothing human is alien, et cetera. Everyone is an everyman (or everywoman). Love and death stand at the exits. The future shyly intimates, the past unpredictably looms. Back in the day, Amerika Haus is a Fascist building, the American visitors are beguiled by the Nazis’ favorite Badenweiler March, the Hofbräuhaus takes all comers, Odysseus Cotton and Susanne (“since she was Circe and the Sirens and maybe also Nausicaa”) fall into their timeless, mythic roles. The book is full of repurposed locations, make-do-and-mend, second acts, moving parts, old situations, old signals.

*

A great mystery to me, and maybe what draws me to Koeppen more than anything else, is how he can write some sentences that are verbless stubs, and others that go on for dozens or scores of lines, and it all sounds like him, and it all is him. It is not style because style changes, and he comes in different styles—but it is perhaps distance or tone, compounded from coldness, information, certitude, indifference, a certain propensity to label, to repeat, to talk up or slang down. Susanne, who in this book successively appears in a lesbian floor show, steals some perfume, possibly kills Josef, picks up, robs, and rescues Odysseus, is likened to a Homeric figure; the boy Ezra sees everything from the vantage point of his own personal fighter bomber; Philipp, shy and ineffectual as he is, is indestructible; Emilia’s groping pawnbroker Unverlacht is styled as a frog. The prose is sumptuous and cadenced, built to be read aloud; the sentences begin briskly, purposefully, then they are distractible, suddenly ferocious, briefly learned, encounter a mantra, loop and repeat, work themselves free. Then a run of nothing but curt blurts. It is as though Koeppen unites in himself the virtues of wildness and sleekness. These are not books the reader makes; they are written with uncommon decisiveness.

*

Koeppen was himself far too impulsive and unorthodox a character to have done such a thing on purpose, or to have planned it thus far in advance, but Pigeons on the Grass turned out to have been the first part of a novel trilogy. In 1953, he published a second part called The Hothouse, in 1954, the third called Death in Rome. All three books are set at the time they were written—they are all “live.” Together, they are known as the “postwar trilogy.” They were the last novels he wrote in his life. He lived another forty years and wrote no others. Now, you may say, nothing easier than to have written three novels and then call them a trilogy, or five and a quincunx, or ten and a decalogue. “What’s that when it’s at home?” my skeptical friend Paul Muldoon might quip; I would probably once have been dubious, too. I don’t like poems in parts, or paintings in parts either. But having long been inside all three books myself, I have to say I am positively in awe of their parallelisms and congruencies.

First, there are no major overlaps among the books: no shared characters, no internal references, nothing like that. The first is set in Munich, the second in Bonn, the small town on the Rhine that had recently pipped Frankfurt to become the capital of the Western half of the divided Germany, the third in the Eternal City, Rome. Pigeons on the Grass is a polynarrative, numerous turning cogs and wheels, like a piece of clockwork; The Hothouse is a monodrama, the story of a Social Democrat member of the Reichstag on the day of a big rearmament debate; Death in Rome brings the four members of a German family, two brothers-in-law and their respective sons (representatives of four great German trades: murder, bureaucracy, theology, and music), to an unintended reunion. The first book is impersonal (we guess Philipp is our point of identification, but we’re not told, and he certainly has no privileges); the second is all personal, with Keetenheuve imagining his decisions and actions reflected in headlines, in italics; in the third, the artist figure, Siegfried Pfaffrath, is given a monopoly on the first person, but only in his sections. So it’s not the setting or the conception or the machinery of the books that are shared. What is it? First, it’s that in each book a public event is trailed, and built up to, and takes place: in Pigeons on the Grass, it’s Mr. Edwin’s talk; in The Hothouse, Keetenheuve’s speech in the debate; in Death in Rome, it’s the concert of new serial music composed by Siegfried. Each book observes the unities of time and place; the first two happen within twenty-four hours, Death in Rome in the space of two days and a night.

But what I am talking about is more inward than that. Each novel seems to be rendered from the postwar atmosphere; it is as though impalpable things—as I say, atmosphere—have concretized themselves or been precipitated against cold glass. (Hence, in part, I think, the title The Hothouse.) Either that, or three different mosaics have been assembled—bricolaged—from the same rubble. The same ingredients make three dishes; the same breakage makes three different books. Everything is real, but we are having three go-arounds on a ghost train as well, which means they are metaphysical, and devices. A bewildering number of the same things, properties, Maguffins, recur in all three: Cars, big luxury cars. Showers—for Alexander, for Frost-Forestier, for Judejahn. Newspaper criers and newspapers. Newspapers, magazines, and radio. Dictaphones or recorders for Philipp, for Frost-Forestier, for Siegfried. Onions. Beer. The books kill off and pair off, bring unexpected deaths and asymmetrical loves. Fast food: Weisswürste in one—“white veal sausages. Klett the hairdresser peeled the skin off the whitish filling with his fingers and popped it in his mouth. Candy-I-call-my-sugar-candy. Klett smacked his lips and grunted contentedly”—meatballs in another—“there was Helen, envied, reviled, eating her meatballs and mashed potatoes with the head of the working group on agricultural land degradation”—hamburgers in the third—“The waiter brought food. The men must have ordered it. Fried onions sizzled on large meat patties. They ate. They stuffed themselves. The men liked the onions. Judejahn liked the onions.”

Cheese. Wine. Buildings. Tunnels and bridges. Cats and dogs. A room above the city, for sex. Ruins. Male prostitutes. Gangs of children. Tribades. The cinema. The German forest. History. Mythology. Literary references, ringing the horizon of all the books: Gertrude Stein (the title of Pigeons in the Grass), Kafka (the ending of The Hothouse from The Judgment), Thomas Mann (title and ending of Death in Rome from Death in Venice). Fish. “How much Edwin would have liked otherwise to discuss the Physiologie-du-gout with the chef and watch the pretty kitchen boys shucking gentle gold-gleaming fish.”—“The matjes was a longtime inmate of salt barrels.”— “They brought him a plate of sea creatures fried in oil and batter. He gulped them down; they tasted like fried earthworms to him, and he felt nauseated. He felt his heavy body turning into worms, he felt his guts squirming with putrescence, and in order to fight off his disintegration, and in spite of his nausea, he polished off everything on the plate.” These things—and I have no doubt there are dozens of others—are deliberately deployed. They have a deteriorating tendency that suggests forward planning—I don’t know how Koeppen did it. He had never been to Rome before a chance invitation in 1954; his Bonn book he wrote in Stuttgart. They don’t deplete or detract from the realism of the books, they are merely a further formal challenge for the author, and a complicating, delaying, enriching thing for the reader. After all, everything that resists limits extends the life of a book, toward infinity, where it belongs.

The poet Michael Hofmann is widely regarded as one of the world’s foremost translators of works from German to English. He lives in London. Read his Art of Translation interview.

From the introduction to Pigeons on the Grass , by Wolfgang Koeppen, translated from the German by Michael Hofmann. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp .

What Would Shirley Hazzard Do?

What responsibility might a novelist have to use their gift to directly engage political debate? Shirley Hazzard’s authorized biographer examines her life for one potential model. For more, read an unpublished story by Shirley Hazzard in our Fall issue.

SHIRLEY HAZZARD. PHOTO: © NANCY CRAMPTON.

In 1990, Shirley Hazzard published Countenance of Truth: it was not the long-awaited novel, successor to her 1980 masterpiece The Transit of Venus, but a dry monograph, in which she revealed in excoriating detail the mendacity of the United Nations and its former head, Secretary-General Kurt Waldheim. She chose for its title a phrase from one of the lesser works of the poet John Milton, whom she paraphrased as lamenting the need to set aside poetry to address the urgent evils of his day; in his case, corruption in the clergy. “I have a work that I love as a poet—as if I would turn away from that bright countenance of truth to mix up with antipathetic matters of this kind if I didn’t feel that I could not forbear to do it.”

Hazzard was drawing attention to the vexed question of when and how writers and artists should participate in the public world. While there might be a sense that writers have some particular responsibility to inform and contribute, or simply to add their voice to debate or their body to protests, such actions are themselves at odds with the practice of writing; they signal a kind of torsion, a split or division in the writing self. In 2020, our world of rolling, global emergencies seems to throw out, endlessly and daily, such challenges. As readers, writers, citizens, we are asked, compelled, it sometimes seems, to inform ourselves and to contribute something. And while, say, a presidential election that offers stark choices, or cataclysmic climate events, or the devastating death of a Supreme Court judge “of historic stature” might engage our time because the consequences and the stakes seem clear and pressing, the decisions, political entities, and structures sitting behind those large-scale public events are often less absorbing, less urgent, and the torsion comes to seem less workable.

By 1990, Hazzard had been writing about the United Nations for two decades, and throughout these years, she weighed and lamented the cost of political writing, anxious always about “not getting on with my novel.” Back in the sixties, she had written to Alfred Kazin about the conflicts of public involvement: “I feel as you do about protests etc—that they are a dreary and thankless business for artists to have to involve themselves in and that the maximum influence still rests in one’s work, however far it may seem from the context at that particular mo. However, an occasional lifting of the head seems necessary, just to show it is not bowed on these matters.”

At first Hazzard directed her efforts toward effecting change at the UN, but she quickly became resigned to a different level of influence and participation. As she explained in an interview:

Well, I had information about the UN just by the circumstance of having worked there, and as years go by with nobody else doing it, I feel some obligation. But I can’t go on with it. If this book doesn’t make any immediate impression, at least it’s on the record of history, and I suppose the ultimate reason for writing is to tell the truth. In the beginning I hoped to change things, but one loses that expectation. I think that a truth set out takes on a life of its own. These aren’t private truths, they belong to everybody, although they always come back to personal conduct. People talk in categories; even I have to use this phrase “the leadership of the UN,” but these are single men—we can use the word “men” because there are so few women in the leadership—human beings who should be answerable for their actions.

The writer’s responsibility, as she understood it, was in the service of truth. In her somewhat dated sense of the enactment of public responsibility—with its solemnity and sense not only of occasion but also of the inherent significance of the writer who might speak out on such matters—Shirley Hazzard provides, perhaps, an exemplum, or at least a perspective, for readers and writers today as they contemplate the newly urgent question of public debate. Even in her own time, her actions had seemed somewhat histrionic. For one thing, her knowledge of the institution had been gleaned while she worked at the United Nations as a lowly administrative assistant (or as former Undersecretary General Sir Brian Urquhart observed dismissively, “She was in clerical”). She spoke without formal authority, in the voice of a private citizen. But there was something indecorous about her fervor. In his New York Times review of her first UN book, Defeat of an Ideal—which detailed iniquities at the UN, most prominently the breach of its own charter from its earliest years, through undue and improper influence of member governments, particularly the U.S. and USSR—Christopher Lehmann-Haupt characterized it as “a lover’s quarrel,” an unseemly, overblown, impassioned engagement:

It’s like being at the dullest of cocktail parties—a United Nations reception perhaps—with clichés dripping all around you … when suddenly a voice rises above the others … a finely modulated voice, speaking with rising passion. And you stop what you’re saying to listen in utter fascination … and turn to see this dark handsome woman advancing on this fat, carbuncled blubber of a man, cursing him, befuddling him with scorching wit, flaying him bloody with lashes of rhetoric, backing him into a corner of the room and laying it on without mercy, until all conversation in the room has stopped, and all the guests are staring horrified at this woman cursing and this fat old man, weeping now. And you wonder why this is happening. Until you realize … she loves him…

The scenario of the impassioned woman speaking truth to power (speaking too loudly or passionately, staging a private battle in a public space) suggests we are in the domain of melodrama; not melodrama in the simple pejorative of excess and exaggeration, but rather in terms of what writers such as Peter Brooks have identified as a form representing the secular drive to virtue in the world, which draws subjects into a conflict between good and evil playing out “under the surface” of things. It is Hazzard’s commitment to an underlying truth that justifies the moral force and energy of her political writing: the desire to expose and account for the truth, holding political institutions to task and refusing compromise. Further, melodrama provides a speakerly ethos of critique and articulates a path forward that is bound up with the importance of the word; that is to say, it propels us into the terrain of a literate and literary authority. The impulse of melodrama is toward truth and goodness, toward imposing, as Brooks puts it, “the moment of revolutionary suspension—where the word is called upon to make present and to impose a new society, to legislate the regime of virtue.”

Melodrama enacts a certain bodying of the private self, a self that is importunate, unaccommodated in public institutions, and called forth into the world through hyperbolic performance. This figure bears an obligation to truth and a hope of transformation. And Hazzard reminds us that this figure is itself the business and the matter of the writer: “The writer’s vigilance over language and attention to language are themselves an assumption of responsibility. When, with the Renaissance drama, men and women began to speak—through literature—with individual voices, rather than as types … there was a humanistic assumption of personal accountability for what was uttered. And so we have continued, in theory at least, to regard it. Our words, whether in literature or in life, are accepted as a revelation of our private nature, and an index of the measure of responsibility we are prepared to assume for it.”

Hazzard was always aware of disruption of “public themes” to her work, lamenting to her friend, the Australian writer Elizabeth Harrower, the “lethal effect” of UN writings “on real work.” Nonetheless, she would continue to commit herself, over and again, to producing nonfiction, almost all of it directed at the UN. Her commentary was welcomed at the time by some UN employees (or former employees), but has had scant effect on the institution itself nor more widely on public debate around it. A measure of this apparent failure might be seen in the fact that while she was the first writer to air publicly, as early as 1980, the claim that Kurt Waldheim had concealed substantial wartime connections with the Austrian Nazi Party, a claim investigated by U.S. congressman Stephen Solarz and falsely denied by Waldheim himself, the story only became news when it was picked up and investigated by a journalist some six years later. Hazzard’s role in its disclosure was for the most part overlooked.

Shirley Hazzard’s UN writings are today primarily of historical interest. She will be remembered rather for her novels and stories: for their complex interweaving of moral and erotic dramas, and for their shimmering prose. She understood sharply the relative importance of the two kinds of writing, and she lived as a writer their divergent energies. But her focus was always on the point where they met, on the labor and responsibility of writing and of reading: “There is at least one immense truth which we can still adhere to and make central to our lives—responsibility to the accurate word… In the words of Jean Cocteau, the good and rightful tears of the reader are drawn simultaneously by an emotion evoked through literature, and by the experience of seeing a word in place.”

Read an unpublished story by Shirley Hazzard in our Fall issue.

Letter from Shirley Hazzard to Alfred Kazin, currently collected in The Alfred Kazin Papers. Copyright © by Alfred Kazin, used by permission of The Wylie Agency, LLC.

Brigitta Olubas is Shirley Hazzard’s authorized biographer and the editor of her Collected Stories and a volume of essays, We Need Silence to Find Out What We Think.

The Alien Gaze

The last time I watched the stars, I was sheathed in the silence of Joshua Tree, California, that southern desert whose titular trees raise their spiny tentacles to the sky. It was a moonscape, beguilingly strange, the Joshuas huge as gentle aliens. This was in July. I’d left—fled—my home in San Francisco for the same reason generations of restless Californians have made pilgrimage to the desert: escape, disconnection from daily life. All around were lone tents and isolated houses, meditators and sound bathers and people floating up to the sky as acid dissolved under their tongues. As a debut author with a book younger than California’s shelter-in-place orders, I’d spent the past few months rubbed raw by attention, uncannily watched. I looked up and thought the usual stargaze thoughts: how large the universe, how small our worldly concerns. I thought about extraterrestrial sightings in Joshua Tree and the annual “Woodstock of UFOs” conference. I thought, as I often do, of alien life—not the scary body snatchers variety, but the reassuring fantasy that even if we fuck up this world, at least there are others out there, doing it right.

I didn’t know that this was one of the last nights I’d see the stars in California.

Two days later, a brush fire crackled through the dry scrub of San Bernardino National Forest, forty miles east of our rented house near Joshua Tree. This was the Apple Fire (33,324 acres, 95% contained), innocuously named. The same sky that had so perfectly framed the stars became a screen on which a horror movie played out on a massive scale, doom rolling in on thick gray clouds. The air was shot through with that particular sick, yellow light of fire country. We drove back north, cutting our trip short.

Less than a week later I woke again, this time in my San Francisco apartment, to the same yellow light creeping over my feet. This was the CZU Lightning Fire (86,509 acres, 100% contained) that crunched through redwoods in Big Basin, seventy miles south. The country’s oldest national park erupted into flame. It was a different fire and yet, it seemed, the same.

A month later we moved north, slipping out from under the choking press of smoke. One night of reprieve on the border of California and Oregon, the sky clear and star-spangled—and then, a week later, the fires (Pearl Hill Fire, Evan Canyons Fire, Cold Creek, Sumner, Fish, too many to list, 790,000 acres, seemingly uncontainable) reached our new northern home.

The West is connected once again, this time not by highway or train track, not by Elon Musk’s futuristic Hyperloop. Fire strings together the future of these states, California and Oregon and Washington and Idaho and Wyoming and Colorado, hundreds of miles of flaming red wound. The injury will never quite heal if things continue as they have: the hottest August on record in six states, the atmosphere growing ever more arid with climate change. The wound will rip open again and again, year after year, as it has for the last four years.

To take these fires personally is the height of narcissism and humility both. In the West, come dry season, we can no longer look up at the stars in order to disconnect from our world; we’ve razed that possibility to the ground and there remains no clearing, no flat rock, no forest seat, no campground, no stargaze without its corresponding gaze into oncoming destruction. Climate change is here and real and so close we choke on it. I can turn off my phone, log out of my email, but I cannot ignore my lungs’ desperate pinging for oxygen. What is not already afire is tinder of our own making. We are connected and we are connected and we are connected.

The six million acres burning in the West are visible from space. I hate to be watched and yet, there is gravity in the idea of that other gaze. I don’t expect alien saviors, not when 1.33 million Joshua trees ignited in the Dome Fire (43,273 acres, 95% contained), those extraterrestrial shapes felled, spiny tentacles smoking in the dust. No. If we’re being watched, then better to think of the watchers as our own future generations, still alive to take to the skies. What will they think of what we do next? We must be humble enough to admit that this is our fault; we must be narcissistic enough to think that we are the only ones who can fix it. It’s time to stop trying to outrun the smoke, which has blown as far as New York. It’s time to vote for candidates who believe in climate change and to boycott corporations that disproportionately contribute to it. Six million burned acres, visible from space. It’s time to look at where the stars used to be, and take responsibility.

C Pam Zhang is the author of How Much Of These Hills Is Gold, which was recently long-listed for the Man Booker Prize. Her writing has appeared in The Cut, McSweeney’s Quarterly, The New Yorker, and The Pushcart Prize Anthology. Zhang is a National Book Foundation 5 Under 35 Honoree.

September 29, 2020

Redux: Leaves Fall Off of the Trees

Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

Ali Smith, with Leo, in Cambridge, 2003.

This week at The Paris Review, autumn has arrived. Read on for Ali Smith’s Art of Fiction interview, Robert Walser’s work of fiction “From the Essays of Fritz Kocher,” and Evie Shockley’s poem “ex patria.”

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, and poems, why not subscribe to The Paris Review? Or, to celebrate the students and teachers in your life, why not gift our special subscription deal featuring a copy of Writers at Work around the World for 50% off? And for as long as we’re flattening the curve, The Paris Review will be sending out a new weekly newsletter, The Art of Distance, featuring unlocked archival selections, dispatches from the Daily, and efforts from our peer organizations. Read the latest edition here, and then sign up for more.

Ali Smith, The Art of Fiction No. 236

Issue no. 221, Summer 2017

INTERVIEWER

Were you pleased to see Autumn referred to as “the first serious Brexit novel”?

SMITH

Indifferent. What’s the point of art, of any art, if it doesn’t let us see with a little bit of objectivity where we are? All the way through this book I’ve used the step-back motion, which I’ve borrowed from Dickens—the way that famous first paragraph of A Tale of Two Cities creates space by being its own opposite—to allow readers the space we need to see what space we’re in.

Michał Gorstkin-Wywiórski, Park in autumn, ca. 1900. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

From the Essays of Fritz Kocher

By Robert Walser

Issue no. 205, Summer 2013

When autumn comes, the leaves fall off of the trees onto the ground. Actually, I should say it like this: When the leaves fall, autumn is here. I have to work on improving my style. Last time the teacher wrote: Style, wretched. It’s upsetting but there’s nothing I can do about it.

Arkhip Kuindzhi, Autumn, ca. 1883. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

ex patria

By Evie Shockley

Issue no. 228, Spring 2019

(quattro stagioni: primavera, estate, autunno, inverno)

a mythology can ask why is autumn so beautiful and why is winter, blight-stricken as it is, so arresting? a mythology, as opposed to a young person, can find autumn and winter much more striking than summer, sun-bleached summer, so legibly the scene of happiness that nothing else can really happen there. a mythology can see the blood in spring, the stages of growth a kind of violence the body does to itself, it will never be this way again yet it can’t get on to the next moment fast enough.

And to read more from the Paris Review archives, make sure to subscribe! In addition to four print issues per year, you’ll also receive complete digital access to our sixty-seven years’ worth of archives.

September 28, 2020

The Art of Distance No. 27

In March, The Paris Review launched The Art of Distance, a newsletter highlighting unlocked archive pieces that resonate with the staff of the magazine, quarantine-appropriate writing on the Daily, resources from our peer organizations, and more. Read Emily Nemens’s introductory letter here, and find the latest unlocked archive pieces below.

“In the before times, we’d celebrate the arrival of the new issue with a party at the office. I’d greet attendees by shouting from atop the pool table (barefoot to protect the felt), and I’d invite a contributor up to share the shortest of readings before the party got back underway. This past week, we gathered online instead of on Twenty-Seventh Street, and I (still barefoot) welcomed readers from my Alphabet City living room. Sure, I missed the mingling, the hugs and hellos, but at the same time I was grateful for the extra space and attention our new format offered, for both our writers and our readers: no one was shouting over bar sounds and, importantly, proximity to the A train wasn’t requisite for attendance. And as I told that night’s featured contributors—Eloghosa Osunde (calling in from Nigeria), Emma Hine (reading from Denver), Rabih Alameddine (speaking to us from San Francisco), and Lydia Davis (reading from upstate New York)—while it had been a joy to read (and edit) their pieces, I found it truly exceptional to hear those works read by their makers. The office parties were known to get a bit crowded, but on Wednesday, the room was fuller than ever, with hundreds of attendees across several continents. If you weren’t able to attend, have no fear: a recording of the program is available below, and we’ve unlocked several pieces related to the event. Another thing I said Wednesday that is worth stating again and again as this new normal takes shape: it is a welcome relief and a small joy to know that while so much is in flux, there is still literature, and it is within our reach to celebrate that writing, to embrace existing traditions and to create new ones.” —EN

Read along while you watch the complete event on YouTube now!

Eloghosa Osunde’s “Good Boy” follows the journey of an unnamed protagonist as he builds a chosen family of queer friends in contemporary Nigeria. “I believe that the world we live in was first made, right?” Eloghosa says. “A big part of imagining other ways to be starts with the imagination, starts with what we write, starts with story.”

Emma Hine’s poems “Cassandra” and “Young Relics” are about families and homes. “My relationship with domestic spaces and objects is very talismanic,” she explains. “I have a lot of trouble separating the feeling of a memory from its location.”

Rabih Alameddine writes about Beirut and a family in crisis in “The July War,” a story he first drafted more than a decade ago, about the 2006 war in Lebanon. In discussing why he returned to the story this spring and why it felt relevant in 2020, he says: “What it had, and what I hadn’t concentrated on, was how people behave during crisis … how people react and behave when encountering sudden loss. How do we grieve? That story took on a new significance to me.”

Lydia Davis reads two stories, “An Incident on the Train” and “The Left Hand.” Listen to those, and then stick around for her conversation about cat literature.

Sign up here to receive a fresh installment of The Art of Distance in your inbox every Monday .

Feminize Your Canon: Alice Dunbar-Nelson

Our column Feminize Your Canon explores the lives of underrated and underread female authors.

Alice Dunbar-Nelson

In April 1895, the up-and-coming poet Paul Laurence Dunbar, whom Frederick Douglass had dubbed “the most promising young colored man in America,” saw a poem by a young writer, Alice Ruth Moore, accompanied by a photograph in which she appeared stylish and beautiful. He wrote to her immediately at her home on Palmyra Street in New Orleans, expressing his admiration, and they began an intense epistolary courtship that lasted two years. Six months in, Paul was declaring. “I love you and have loved you since the first time I saw your picture.” He called Alice “the sudden realization of an ideal!” She combined beauty with literary talent and the feminine accomplishments appropriate to an upper-class young woman of the day: “Do you recite? Do you sing? Don’t you dance divinely?” They modeled themselves self-consciously after Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning, another pair of lovers and writers whose romance began by letter. Paul referred to “This Mr. and Mrs. Browning affair of ours,” and Alice, after they’d married, reflected on her role as a wife who was at once muse, colleague, and practical support: “We worked together, read together, and I flattered myself that I helped him in his work. I was his amanuensis and secretary, and he was good enough to write poem after poem ‘for me,’ he said.” The Dunbars embodied the aspirational ideal of the educated, cultured African American, allowed access to the white halls of fame and power as long as they were willing to remain, flattened and fixed, in the roles of representatives of their race.

Such a role did not allow for physical passion and disorder. When the couple met in person, the refinements of their written courtship became scrawled over with violence. In November 1897, in what Paul described as “one damned night of folly,” he raped Alice, leaving her with internal injuries. Five months later, the couple eloped. The marriage lasted four years, and ended as violently as it had begun, with a drunken beating. Alice left, and never returned. Paul tried to woo her back with letters, but she answered only once, with a single word delivered by telegram: No. When he died of tuberculosis in February 1906, at the age of thirty-three, she found out by reading a notice in the newspaper. Yet despite their estrangement, Alice worked hard after Paul’s death to keep his reputation and his work alive, reading his poetry in public and, in 1920, editing The Dunbar Speaker and Entertainer, a hefty anthology of “the best prose and poetic selections by and about the Negro race,” including many selections by Paul, but also her own poetry and selections by writers from James Weldon Johnson to Abraham Lincoln, with the “Caucasian” writers denoted by an asterisk. (Alice’s portrait, rather than Paul’s, appears as a frontispiece.)

Brief though it was, Alice Moore’s marriage to Paul Dunbar has tended to overshadow her achievements as a writer, even though she outlived him by three decades and married twice more. For many years, according to Katherine Adams, Sandra A. Zagarell, and Caroline Gebhard, the editors of Recovering Alice Dunbar-Nelson for the Twenty-First Century, a 2016 special issue of the women’s literature journal Legacy, her marriage was “the only thing making her visible and the primary thing obscuring her from view.” That ironic combination, a spotlight partially covered, is a fate she shares with many talented wives of famous men. The variety of names she adopted—Alice Ruth Moore, Alice Dunbar, Alice Moore Dunbar, Mrs. Paul Dunbar, Alice Ruth Moore Dunbar, Alice Dunbar Nelson, Aliceruth Dunbar-Nelson, and Alice Dunbar-Nelson—reflects the basic tension between a woman’s marital identity and her declaration of herself as an author. Highly educated, with a strong belief in her own talent and determination to make her own living, Dunbar-Nelson was a New Woman, that protofeminist figure who dominated American culture at the turn of the twentieth century, yet she also recognized and embraced marriage as essential to a woman’s social standing. “It is not marriage I decry, for I don’t think any really sane person would do this,” she wrote in “The Woman,” a story in her first collection Violets and Other Tales, published in 1895. But despite this declaration, the same piece contains voluminous arguments in favor of the single life. Critics who have wanted to pin her down to one identity, one genre, or one set of beliefs about race or gender, have struggled to do so. Appreciating the variety of her work requires a nuanced attention to the many layers of her life.

Alice Dunbar-Nelson was born on July 19, 1875, in New Orleans. For a writer who otherwise documented her life meticulously, and whose diary, correspondence, and reams of unpublished writing exist in an extensive archive, she was mostly silent about her early life. In one letter to Paul, her distress is palpable when he presses on the sore point of her origins: “Dearest—dearest—I hate to write this—How often, oh how painfully often, when scarce meaning [to] you have thrust my parentage in my face.”

As a light-skinned Black woman operating within the blunt racial binary of post–Civil War America, that silence signifies both shame and strategy. In her hometown of New Orleans, Dunbar-Nelson had a third option for a racial identity. Before the Civil War, the city’s population was divided between whites, enslaved blacks, and free gens de couleur, light-skinned Creoles of French or Spanish descent, who were a powerful and elite social group. This was the identity Dunbar-Nelson claimed for herself, and the figure who dominates her early short stories. She likened the “true Creole” to “the famous gumbo of the state, a little of everything, making a whole dilightfullly [sic] flavored, quite distinctive, and wholly unique.” It was also a status that carried little weight outside New Orleans, in a world where the color line was brutally policed. In several stories, Dunbar-Nelson explored the anxiety of passing and the pain of colorist prejudice. Her short story “The Stones of the Village,” dramatizes the bullying and exclusion that her light-skinned hero endures from both the black and white boys of his village. But instead of trying to claim a place among his own people, the boy decides to pass as white. The story traces his Dickensian journey from his grandmother’s village to a job working for an elderly book dealer in New Orleans, and then via a legacy in the old man’s will to college, law school, and eventually marriage to a white woman and a position as a respected judge. Throughout his career his fear of being exposed drives him to overt and virulent racist treatment of “Negroes.” Eventually he learns that an up-and-coming African American lawyer knows his true identity but agrees to keep it quiet in exchange for fair treatment in court. Her unpublished story “Brass Ankles Speaks” hews closer to Dunbar-Nelson’s own experience, narrated by a speaker who describes herself as “white enough to pass for white, but with a darker family background, a real love for the mother race, and no desire to be numbered among the white race.” Her anger throughout the piece is directed at darker-skinned Black people who tease and ostracize her, resenting both her ability to pass and her decision not to.

Eleanor Alexander, the author of Lyrics of Sunshine and Shadow, a biography of the Dunbar marriage, detects in Alice’s status anxiety and her flashes of contempt for her much darker husband an attitude of internalized racism, or at least classism and colorism, that caused her to distance herself from the designation “Negro.” But other critics make the point that she proudly declared herself a “race woman” and that her identity as African American was never “masked” or concealed from readers. “This is a writer who embraced and labored incessantly on behalf of black people, including herself, and understood that work to require an interrogation of belonging—a refusal to make a piety of it,” write Adams, Zagarell, and Gebhard. Dunbar-Nelson grew up in an era preoccupied with questions of racial belonging and definition, which included a campaign to capitalize the word “Negro” as a question of dignity. She seems, however, to have resisted the idea that race was reducible to labels or symbols, exploring it instead as a variable, and highly individual, lived experience.

According to Alexander, although Dunbar-Nelson saw the category “Negro” as denoting a formerly enslaved person and thus distanced herself from it, her own family history was more closely embedded with slavery than with free Creole society. On the scraps of evidence afforded by birth certificates, name changes, and city records, Alexander pieces together the origins of Alice Moore as the daughter and granddaughter of women who were formerly enslaved. Her father’s identity is uncertain, as is the question of whether he was married to her mother, or whether Alice and her older sister had the same father—either way, he was not part of her life. Alice’s mother, Patsy, and grandmother, Mary, worked as servants and washerwomen, as many Black women did: part of a huge labor force that helped clean and clothe the upper classes. Together they made sure that Alice and her sister, Leila, were shielded from this work and kept away from their employers’ homes—a common protective strategy by servants, who knew the sexual exploitation and violence that routinely went on in those homes. Instead, Patsy and Mary worked to consolidate a class status for Alice and Leila by giving them an education they themselves had not received. Alice was first sent away as a young teenager to Southern University in Baton Rouge, and graduated from the prestigious Straight (now Dillard) University in New Orleans in 1892 with a teaching qualification. Teaching offered a route into elite society for African American women, who dominated the profession (in Washington, D.C., a few years before Alice moved there with Paul, women made up more than 80 percent of the city’s Black schoolteachers).

Alice’s first book was published in 1895, when she was barely twenty years old. Violets and Other Tales was a multigenre collection of poetry, stories, sketches, and essays rooted in New Orleans Creole society—“pieces of exquisite art,” as Paul, who was courting Alice when the book was being published, described them. Its reception in the press is a reminder of how absolute the division was at this time between works by Black and white artists. In the African American press, the book and its author were effusively praised, as much for what they represented—the “best of the race”—as for the specifics of the work. The Daily Picayune, the city’s white-run paper, denounced it as “slop”—which Gebhard argues was punishment for “having crossed the color line by presuming to submit it for review at all.” Interestingly, Dunbar-Nelson used the same pejorative years later when reassessing her early collection, which is undeniably sentimental, as was the style of its era. But its themes would linger into her next, and today best-known, collection, The Goodness of St. Roque, and Other Stories (1897), even though she left New Orleans for good the following year at the age of twenty-one.

In 1897, Alice moved to New York City, where she worked with writer and activist Victoria Earle Matthews at the White Rose Mission, a settlement home for working-class Black girls on East Eighty-Sixth Street. She continued to write, working on an unpublished collection of stories about the new community in which she found herself. She was a clubwoman, the main arena for African American women’s activism at the time, and an active supporter of women’s suffrage. In 1902, when her marriage to Paul Dunbar ended, Alice moved to Wilmington, Delaware, and began to work as a teacher at Howard High School, where she had an intimate friendship with the (considerably older) school principal Edwina B. Kruse, one of several important relationships with women over the course of her life. She stayed at Howard until 1920, when she was fired for her political radicalism. For Dunbar-Nelson, teaching was both a creative outlet and a form of political engagement: she wrote plays for her students to perform, and shared with her friend W.E.B. Du Bois a belief in the transformative power of the classroom for African Americans, and the importance for Black children of stories that centered Black characters—lamenting in her essay “Negro Literature for Negro Pupils” that “for two generations we have given brown and black children a blonde ideal of beauty to worship, a milk-white literature to assimilate, and a pearly Paradise to anticipate, in which their dark faces would be hopelessly out of place.” In her diary, which she kept daily for most of her life, she also recorded less lofty reactions to the daily grind of the classroom, as in this outburst from 1897: “Exhausted? I feel like a dishrag. 62 untamed odoriferous kids all day… Fiends, just fiends pure and simple.”

Throughout her time in Delaware, Dunbar-Nelson’s activism continued. She wrote for Du Bois’s The Crisis on women’s suffrage and became a field organizer for the campaign in Pennsylvania. In 1916, she married Robert J. Nelson, a journalist and politician, and together with him edited and published a progressive newspaper, the Wilmington Advocate.

In her diary, she also detailed the romantic relationships she had with women, including the Los Angeles–based activist Fay Jackson Robinson and artist Helene Ricks London, in entries that are sometimes tortured, but often frank and celebratory. They reveal a woman who, in private, was not afraid to cast off the constraints of respectability. In 1928, she described an evening with a group of women who were, like herself, married clubwomen: “We want to make whoopee… Life is glorious. Good homemade white grape wine. We really make whoopee… Such a glorious moonlight night.” Selections from her diary were edited and published in 1984 by Dunbar-Nelson’s literary champion Akasha Gloria Hull as Give Us Each Day, a landmark in Black feminist literary history and a vibrant glimpse into the writer’s inner life, now unfortunately out of print.

In the twenties, the cultural and political explosion of the Harlem Renaissance swept Alice Dunbar-Nelson up in its trail, even though she had not lived in New York for many years and was still based in Delaware. Her poetry, much of it written earlier, was rediscovered through its appearance in journals and collections like The Crisis, Opportunity, and the 1927 collection Ebony and Topaz. She was friends with most of the leading lights of the era, especially Du Bois and the poet Georgia Douglas Johnson, but she had her differences with them, too. She critiqued the novelist Jessie Redmon Fauset’s generally well-received novel Plum Bun, rejecting the “injudicious laudation” that she worried was coming to a Black writer purely on the basis of race. She wanted a bigger frame, and laid claim to a white literary canon that was as much her heritage as any other, writing a scholarly dissertation on Wordsworth, with whom she shared a love of nature. One of her best-known poems celebrates the natural beauty of a violet in nature by contrasting it with the artifice of its copy in an urban setting, where the idea of the flower calls to mind: “florists’ shops, / And bows and pins, and perfumed papers fine; / And garish lights, and mincing little fops / And cabarets and songs, and deadening wine.”

Despite her early reputation as a poet, during the twenties Alice Dunbar-Nelson found her voice more and more as a journalist. She wrote a syndicated column, Une Femme Dit, and contributed a wealth of reviews and essays to newspapers and magazines. She was an in-demand speaker and although she was rarely paid well for it, she recognized the importance of maintaining a public profile against the twin forces of gendered and racial erasure. In her diary she was open about her constant struggle for money, lamenting in 1931: “the depression hit my royalties!” But she also blamed herself for her inability to find a stable footing in a field dominated by white men. Her work was so often uncredited, unpaid, or both. “Damn bad luck I have with my pen,” she wrote in her diary. “Some fate has decreed I shall never make money by it.” Yet in her energy and appetite for life’s pleasures, from the literary to the human to the natural, Alice Dunbar-Nelson celebrated beauty and freedom to the end of her life. Thanks to the scholars who’ve fought to resurrect her legacy, she may finally have the broader recognition she deserves, as a prolific, politically engaged writer whose poetry is only the beginning.

Read earlier installments of Feminize Your Canon here.

Joanna Scutts is a cultural historian and critic, and the author of The Extra Woman: How Marjorie Hillis Led a Generation of Women to Live Alone and Like It.

September 25, 2020

Staff Picks: Monsters, Monuments, and Miranda July

Evan Rachel Wood as Old Dolio Dyne in Miranda July’s Kajillionaire. Photo courtesy of Focus Features.

In California, you’re always waiting for the Big One. This shaky ground serves as the foundation for Miranda July’s latest film, Kajillionaire, in which the Big One could be either an earthquake or a windfall for an oddball family of three who get by pulling scams and living in the leaky office of a bubble factory. But that’s how they like it, the patriarch claims, saying, “Everybody wants to be a Kajillionaire. I prefer to just skim.” His twenty-six-year-old daughter, Old Dolio, has never known anything but this perpetual absence of money, comfort, and so-called tender feeling. Along comes Melanie, who tries to show Old Dolio a world beyond her parents. Small earthquakes anticipate Old Dolio’s reckoning, interrupting moments of potential intimacy. But little tendernesses urge her to crawl out from the bubble factory basement or the gas station bathroom stall. Even the simplest acts of affection are transcendent, surprising: getting her hair brushed, the word hon. Fans of July’s work will not be surprised by the strangeness—the intricate motions of the bodies, the strange encounters, the role-playing—but they might not expect the sense of resolution. This ending is hard earned, though. The cinematography brings out the precious moments of softness as the screen suddenly is overtaken by a sunspot and the soundscape swells. “I’m lucky … I won’t miss my life,” Old Dolio says when she thinks the Big One has come. She knows this is it, she says, because she’s always been told that when it comes, “it will be all dark all around.” Then she opens the door to blinding light. —Langa Chinyoka

Opinions abound about what to do with monuments that raise up perpetrators of slavery and colonialism. Toppling or otherwise removing them seems elegantly simple and increasingly likely. The British artist Hew Locke, on the other hand—or rather at the same time—uses monuments to portray a more complex history of the men memorialized, the eras they inhabited, and the legacy that present-day viewers inherit. By layering paint and objects over large-scale photographs of statues, Locke adds weight and depth to hollow-cast figures. Thus, a Pilgrim’s iconically austere costume is bedazzled with lacy gold, jet beads, buffalo coins, and delicate but unmistakable chains. George Washington has cowrie shells in his hair, coins on his waistcoat, and shackled humans hanging from his wrists. The British slave trader and philanthropist Edward Colston looks pensive in his statue, which was recently thrown into Bristol Harbor by Black Lives Matter activists, but under Locke’s treatment, covered in gold, jewels, coins, and trading currencies, he appears to be huddling beneath the covers of his ill-gained wealth. This work acknowledges the indelibility of individual lives and acts—the subjects’ and the sculptors’—in all their tangled, tragic truth. Serendipitously, because Locke has never been allowed to execute his vision directly on the statues themselves—only on photo prints—his pieces may well outlast them. —Jane Breakell

Abdellah Taïa. Photo: Abderrahim Annag. Photo courtesy of Seven Stories Press.

The Moroccan writer Abdellah Taïa’s novel A Country for Dying (translated from the French by Emma Ramadan) depicts a Paris distinct from the stuff of Anglophone fantasies. The story follows three characters: Zahira, a forty-year-old Moroccan sex worker in love with a man who does not return her feelings; Zahira’s friend Zannouba, who undergoes gender confirmation surgery and reflects on questions of trauma and identity; and Mojtaba, a gay Iranian revolutionary who by chance stays with Zahira for the month of Ramadan. Taïa, who came out as gay in Morocco, where homosexuality is illegal, in 2006, poignantly portrays the lives of immigrants in a city and country that is frequently hostile to them, and openly questions France’s perception of itself and its immigration policies. —Rhian Sasseen

Art museums are opening, but who among us has not wandered alone the cavernous galleries of the Met wishing they’d taken those art history electives? Whither the visiting lecturers, the docents? The Frick Collection’s YouTube channel is here for our untrained eyes. Each installment of the Cocktails with a Curator video series spends about twenty minutes on a close reading of a painting, the perfect amount of time both to feel versed in the work and to treat oneself to the suggested drink pairing: Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’s Portrait of Comtesse d’Haussonville gets an absinthe concoction, called the Jaded Countess, with a potency that matches the subject’s expression. Regarding Vermeer’s Officer and Laughing Girl, the curator Aimee Ng says, “When I look at a Vermeer painting up close, I always get the sense that if I could just peel back this top layer of the craqueler, the natural cracking that happens to paintings … if I could only get past that layer, then I could see with absolute precision what was painted there.” For me, Cocktails with a Curator does exactly this. Other series on the channel include Travels with a Curator and What’s Her Story?, which focuses on women such as Audrey Munson, “America’s first supermodel,” whose likeness graces statues and sculptures across New York City. They also have the real meaty stuff, full lectures recorded in the time of auditorium gatherings (these are organized nicely on the Frick Collection’s website). It’s a collection unto itself, an energetic effort in art education and appreciation where the casual visitor can lose themselves to what’s on view. —Lauren Kane

At last, the new title from Supergiant Games, one of my favorite developers, has been released in full. Hades has you don the blood-red laurels of Zagreus—son of the Greek god Hades and prince of the underworld—as he tries to flee his father’s wretched domain. Along the way, Olympian gods and various other classical figures such as Sisyphus and the Furies offer you their help or scorn. But in fighting your way through battle-ready shades, skeletons, and monsters, you quickly realize that any escape attempt at this point will end in death. You’re already in the underworld, though, so what does death really mean? It means a return to the bloody pool of souls in your father’s house, where he awaits to reprimand you for your foolishness. But the hacking and slashing are so fun, and hell is so infernal, that you might as well try again. And again. And again. Maybe you make it a bit farther this time, maybe you come up short that time, but there’s less exasperation in death than a strange joy in knowing you’ll get to talk to the fascinating characters in your father’s court once again, pet Cerberus one more time, and make yourself stronger for the next run. And once you’ve settled into the combat, you’ll soon find yourself engrossed in the classical drama unfolding among Zagreus, Hades, and the rest of the underworld. Between the gorgeous artwork and the phenomenal voice acting, you’ll also get sucked into the personal comedies and tragedies of each figure you meet along your journey, from Orpheus to a bashful Gorgon head named Dusa. And lastly, there’s the soundtrack, perhaps the most artful dimension of any Supergiant game—though everything else comes close. The studio’s in-house composer, Darren Korb, crafts a distinctive sound that brings the whole panorama together. In each of Supergiant’s previous works—Bastion, Transistor, and Pyre—the final ballad brought me to tears. I’ve yet to finish Hades, but I have no doubt Supergiant will do it again. —Carlos Zayas-Pons

Still from Hades. Photo courtesy of Supergiant Games.

September 24, 2020

Ramona Forever

I returned to Ramona Quimby for nostalgia. What I found was even better: a mystery.

Beloved Portland, Oregon, author Beverly Cleary wrote the Ramona books over four decades, from Beezus and Ramona (1955) to Ramona’s World (1999). Set on leafy Klickitat Street in Portland, the eight-book series follows the adventures of spunky Ramona Quimby, her sister Beezus (and, later, her baby sister Roberta), her cat Picky-picky, her parents, friends, and neighbors. Seeing images of Portland in tear gas, under an orange sky, I’ve felt enraged, terrified, and helpless. I’ve wanted to escape to Ramona’s Portland, with invisible lizards and makeshift sheep costumes and beloved red rubber boots.

And then, escapism turned into an enigma. Cleary writes in Ramona Quimby, Age 8, “Ramona had reached the age of demanding accuracy from everyone, even herself.” As it turns out, this isn’t exactly true. The Ramona series has many tiny pinpricks of the uncanny—and each is a delight.

Ramona and Her Father, the fourth book, opens with Mr. Quimby bringing home a little bag of candy as a present for Beezus and Ramona. “His daughters pounced and opened the bag together,” writes Cleary. “‘Gummybears!’ was their joyful cry. The chewy little bears were the most popular sweet at Glenwood School this fall. Last spring powdered Jell-O eaten from the package had been the fad. Mr. Quimby always remembers these things.”

But there’s something wonky in the state of Oregon. How does Ramona know what gummy bears are? Ramona and Her Father was published in 1977, but gummy bears didn’t hit American stores until at least 1981. In the twenties, German factory worker Hans Riegel, founder of the candy company Haribo, produced the first bear-shaped gummy candies, and they quickly became a beloved confection in Riegel’s home country. In the sixties and seventies, military service members introduced the candies to their families, and German teachers started bringing the bears to American classrooms. But it wasn’t until the eighties, when gummy bears started getting mass-produced for the U.S., that they became a huge hit, inspiring TV shows (The Adventures of the Gummi Bears) and earworms (“The Gummy Bear Song”). So how were gummy bears the confection du jour in Portland, Oregon, in 1977? Ramona and Beezus aren’t in German class, and Mr. Quimby, who procures the candies for them, isn’t in the army. Plus, the flavors are all wrong. They call the red bears “cinnamon,” which, as any Haribo (or Trolli or Black Forest) fiend knows, is never the red flavor.

As Ramona and Beezus carefully organize the candies by color, they overhear their father and mother in a tense discussion, and they realize something is not right. The gummy-bear scene marks the division between a fundamentally stable world and one that can wobble off its axis, with lasting repercussions. Mr. Quimby has lost his job, throwing him into the sort of funk that anyone who’s, say, been stuck in their house for six months can relate to: he listlessly pushes a vacuum around, smokes, stares at the television, and hovers over the phone, waiting for prospective employers to return his calls.

More unsolved details emerge. “Taxes are due in November,” Mrs. Quimby frets as she tries to calculate how the family can stretch the budget. Taxes are due in April; quarterly taxes are due in September or January. To what government do the Quimbys owe money? Eventually, much to the Quimby family’s relief, Ramona’s father gets a job at ShopRite. There’s no mystery in ShopRite’s timeline: the name “ShopRite” emerged in 1951, and hundreds of these stores exist. But ShopRite has only ever served six states: Connecticut, Delaware, Maryland, New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania. So where does Ramona’s father work?

Images from The Art of Ramona Quimby, by Anna Katz (with illustrations by Louis Darling, Alan Tiegreen, Joanne Scribner, Tracy Dockray, and Jacqueline Rogers)

When we turn to the illustrations for the book, the incongruities multiply. Though Beezus and Ramona only age six years over the course of the series, the author aged four decades while writing them, and the illustrators had to grapple with the balance of keeping Ramona accurate while making sure each decade’s young readers could still relate to her. As Anna Katz chronicles in her warm new book, The Art of Ramona Quimby, each of her illustrators presents a different Ramona aesthetic, from Louis Darling’s original jazzy pen-and-ink cartoons, to Alan Tiegreen’s scribble-inspired doodles, to Tracy Dockray’s gray watercolor shades, to Jacqueline Rogers’s fast sketchbook energy—not forgetting Joanne Scribner’s hyperrealistic, resin-layered cover art. Details get updated: strolling ladies wear fifties-era tea dresses in Darling’s depiction and full-on athleisure in Rogers’s. So which Ramona is the real Ramona: a spiky-haired fifties toddler in dungarees, or a grinning nineties child in bangs and slogan T-shirts?

Spread from The Art of Ramona Quimby, by Anna Katz

According to Cleary’s winsome autobiography, A Girl from Yamhill, Cleary wanted to write the kind of books that kids could see themselves in, so she told stories based on her own childhood. Cleary wrote to Darling in 1967, when he was working on Ramona the Pest, about kindergarten fashions: “Sashes are Out in kindergarten. Mean old boys yank them… Girls always wear dresses with bobby socks or sometimes knee socks… All boys in rain gear look exactly alike. They wear brown boots, yellow rain coats that are usually too long and the kind of rain hat that has a visor and comes down over the neck and has a sort of hlf[sic]-moon space from which they peer out like little animals looking out of burrows.” Though Ramona isn’t from any one particular time period, she has to feel real at the moment she’s being read, and to do that, even the smallest details have to ring true to her readers. So even though Ramona looks anachronistic in her newer iterations, it’s these very inaccuracies that make her all the more real.

My favorite Ramonas are the ones where we see her as she sees herself. Near the end of Ramona and Her Father, Tiegreen’s Ramona peers into a Christmas-tree bauble, and the portrait in a convex mirror gives us Ramona through Ramona’s eyes: distorted face, huge nostrils blooming at the center of the curved surface, exaggeratedly drooping eyes melting into her cheeks.

I slipped deep into my nostalgia, wishing that mysterious gummy-bear precognition was still the weirdest thing going on in Oregon. But when I returned to Ramona’s world, I didn’t find the comforting bubble I craved from Klickitat Street. Instead, I discovered a Ramona I could easily picture grappling with 2020, just the way her illustrators have always brought her to new life for each generation. As Katz points out, Ramona has always been reimagined to meet her world. I pictured Mrs. Quimby sewing Ramona an ill-fitting mask out of some hideous leftover fabric scraps from the neighbors, Ramona vowing that she would scowl every time she had to wear it, even if no one could see her grimace. Mr. Quimby would be an essential worker, making the whole family terrified every morning. He might even have to quarantine in the new extra bedroom, prompting Ramona to start drawing the Q in “Quarantine” with cat ears and whiskers, the way she adorns her own initial.

Ramona taught us how to look for the weirdness in the everyday, and the everyday in the scariest moments. When she wears a particularly gruesome witch costume in Ramona the Pest (“the baddest witch in the world!,” she declares), she begins the day delighted with her anonymity, but ends terrified by the greatest fear of all: no one will know who she is. So, she carries a huge poster with her name on it, presumably beaming under the warty disguise. The mask itself isn’t scary—disappearing, anonymity, being forgotten is what’s most frightening of all. I remembered Ramona’s fear that she’d lose the limelight to the newborn when Ramona’s mother reveals her pregnancy in Ramona Forever, but what I didn’t remember was that Ramona actually does, albeit briefly, have to leave her family. Immediately after baby Roberta is born, Ramona isn’t allowed to see her mother in the hospital, because children under twelve might carry contagious diseases. Alone in the waiting room, Ramona starts to itch, working herself into a psychosomatic lather. A passing doctor proclaims she has “siblingitis” and writes her a prescription. Finally, Mr. Quimby emerges, reads the scrip, gives her a hug, and the itching disappears. Even in isolation, Ramona’s loved ones refuse to let her be forgotten—and neither will we.

Adrienne Raphel is the author of Thinking inside the Box: Adventures with Crosswords and the Puzzling People Who Can’t Live without Them.

David Hockney’s Portraits on Paper

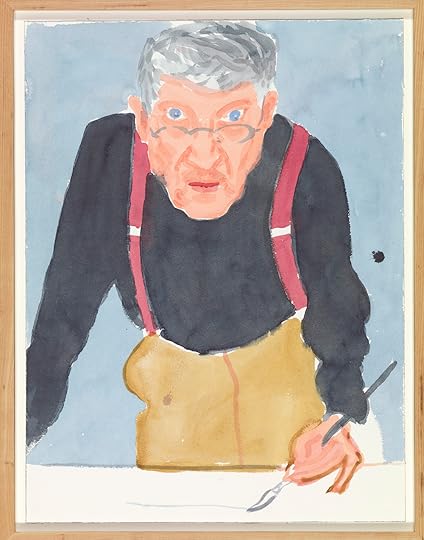

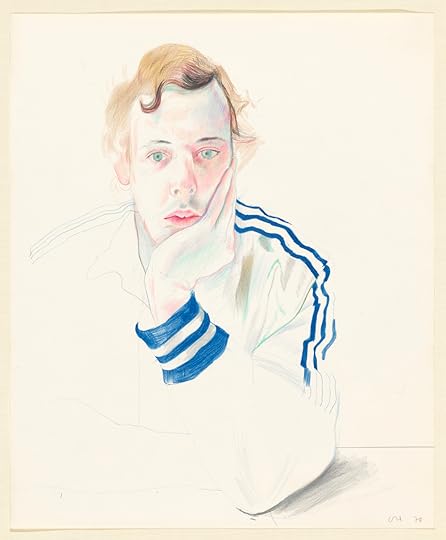

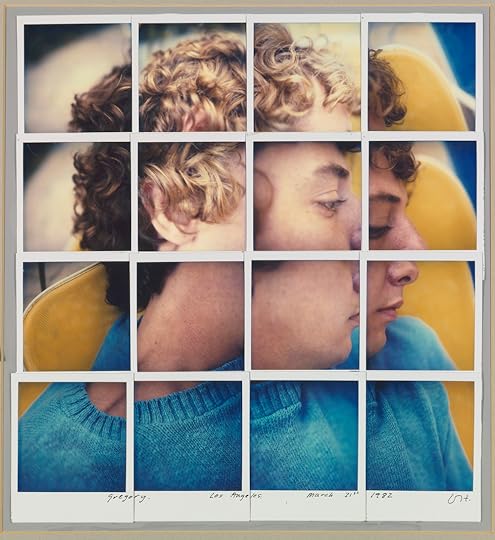

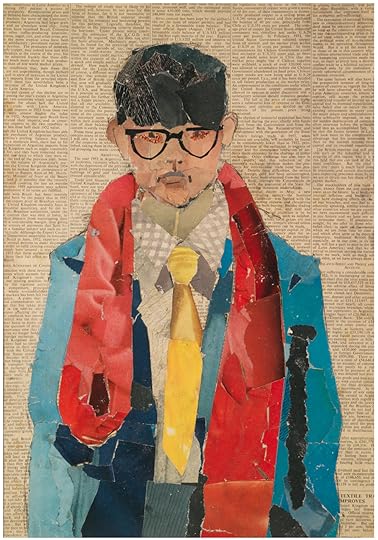

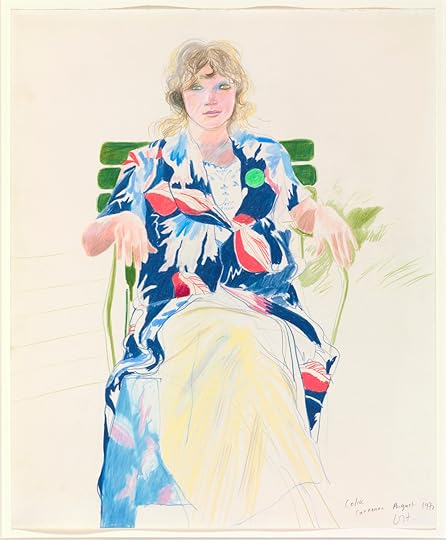

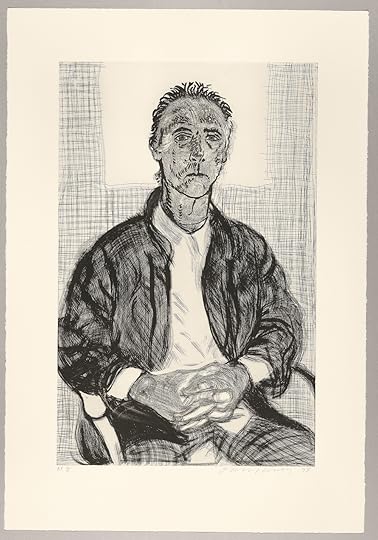

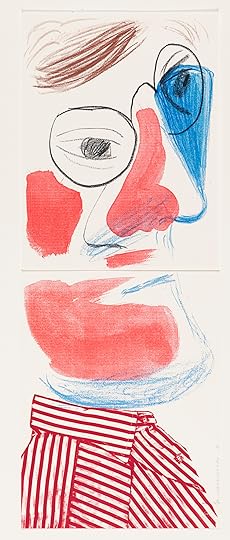

Opening next week at the Morgan Library & Museum, “David Hockney: Drawing from Life” is the first major exhibition to focus on the artist’s portraits on paper. Spanning more than half a century, the works showcased in “Drawing from Life” see Hockney returning again and again to some of the individuals he holds dearest: the designer Celia Birtwell, his friend and former curator Gregory Evans, the printer Maurice Payne, his mother, and himself. Evident everywhere is Hockney’s mastery of color and his devotion to capturing the subject at hand. A selection of images from the show appears below.

David Hockney, Self Portrait with Red Braces, 2003, watercolor on paper, 24″ x 18 1/8″. © David Hockney. Photo: Richard Schmidt.

David Hockney, Gregory, 1978, colored pencil on paper, 17″ x 14″. © David Hockney. Photo: Richard Schmidt.

David Hockney, Gregory. Los Angeles. March 31st 1982, 1982, composite polaroid, 14 1/2″ x 13 1/4″. © David Hockney. Photo: Richard Schmidt.

David Hockney, Self Portrait, 1954, collage on newsprint, 16 1/2″ X 11 3/4″. © David Hockney. Photo: Richard Schmidt.

David Hockney, Celia, Carennac, August 1971, 1971, crayon on paper, 17″ x 14″. © David Hockney. Photo: Richard Schmidt.

David Hockney, No 1201, 2012, iPad drawing, 37″ x 28″. © David Hockney.

David Hockney, Maurice 1998, 1998, etching, 44″ x 30 1/2″. © David Hockney. Photo: Richard Schmidt.

David Hockney, Study for My Parents and Myself, 1974, crayon on paper, 14″ x 17″. © David Hockney. Photo: Richard Schmidt.

David Hockney, Self Portrait, July 1986, 1986, homemade print on two sheets of paper, 22″ x 8 1/2″. © David Hockney.

David Hockney, Mother, Paris, 1972, colored pencil on paper, 17″ x 14″. © David Hockney. Photo: Richard Schmidt.

“David Hockney: Drawing from Life” will open on October 2, 2020, at the Morgan Library & Museum. The show will run through May 30, 2021.

September 23, 2020

Dear Building Residents

Dear Building Residents,

I grew up underneath you. Some of you made a show of knowing my name, would call to me and wave if you passed me in the lobby. Some of you didn’t even know your building superintendent had a daughter. My father, when he was still your super, used the computer in our basement apartment to write you letters a little bit like this one—notices telling you to please be advised about upcoming hot-water outages and elevator-maintenance work, which always ended with an apology for any inconvenience and a note of thanks for your patience and cooperation. He would often tell me there were lots of worse jobs out there. But last year, when he announced at sixty-six that he was leaving the job, one of you, surprised, asked him why. You thought he’d stuck around the building for over thirty years because he loved being a residential super, or working for you, or the Upper West Side location.

Please be advised: he was mostly there because he wanted health insurance.

Spelled out like that, it all sounds a bit underwhelming. In fiction-writing textbooks, there’s often a passage urging fledgling writers to ask, What does this character want? “Access to affordable health care to protect his family” lacks narrative oomph—despite the fact that affordable health care is what so many people want, need, and increasingly don’t have. That access, or lack thereof, has bent the course of my parents’ own stories in ways that may not have been cinematic but have always been high stakes. You don’t know about these contours, which is partly why I want to tell you now. It seems strange to me, in a late-capitalist-end-times way, that I can know your life from your garbage—the garbage room was right next to our apartment—yet you don’t know the way the health insurance industry shaped my family’s life.

When I was a kid, every year on my birthday (celebrated beneath your very feet!) my mother would tell the story of how my parents were between paychecks on the day she went into labor with me, six weeks before the due date. “We had to borrow twenty dollars from a neighbor for a cab to the hospital,” she’d say. My parents were broke when I was born, but not for any of the reasons that we see often in movies and books (drugs, alcohol, fallen-from-grace genteel poverty, et cetera). Rather, my mother had developed an autoimmune disease in her late twenties that forced her to leave her job. She paid for health care as needed out of pocket. With my mother only able to work sporadically, the savings my parents had vanished. And the money from my dad’s job meant no Medicaid, either.

Are these technical details about health care access boring? Thank you for your patience while the building staff works to tell you this necessary story as efficiently as possible.

When my parents decided to have a child, my father found a new job doing building maintenance, which was supposed to offer insurance after my dad had worked there for six months. After the six months passed, my mother became pregnant with me. The health care company deemed my mother’s pregnancy a pre-existing condition and said my father would have to work there a year before my family would become eligible for pregnancy benefits. Outraged by this, my father’s boss at the time, Jerry (a man my mother described, whenever she told me this story, as “a complete gangster”), paid for my mother’s health care out of pocket. The system failed us, but we were briefly protected by this individual’s simultaneous anger and compassion. “For a little while, I worried we’d have to name you Jerry,” my mother told me over birthday cake, “though we decided against it.”

Is this information, my inclusion of the birthday cake detail and my mother’s voice, too personal for comfort? A reminder: Please do not store personal property in the hallway, including but not limited to scooters, bikes, and strollers. These are fire hazards.

I’m thankful that Jerry had the financial power to back up his outrage. I’m thankful that my father’s job as a residential super gave all three of us health insurance when I was growing up (even though we had to go through a three-month trial period at the beginning of my father’s employment, during which time my parents had to pay for our private health insurance out of pocket; even though our insurance from the building never included pharmaceutical benefits). And I’m enormously thankful my parents were able to get on Medicare last year and that my father doesn’t have to be a sixty-something-year-old essential worker in the city right now. I’m thankful that after years of hard work and paying into this system, my parents won’t have to rely on the luck of meeting people like Jerry. Is this a thank you letter after all? To whom? So often, when writing to someone with more resources, more power, my expression of gratitude seems to creep in on just the other side of lack.

When I’ve told others that I grew up in a rent-free basement apartment of an increasingly upscale building in Manhattan, they often assume that I wished I was one of you, the residents to whom my father wrote neutrally worded letters. Dear building residents: I do not require access to your residential units or your lives. While I certainly envied how your apartments got natural light, I liked my life and I didn’t want to be you. I heard your arguments in the hallways, your calls of complaints, and knew you were just people. Sometimes it seems to me that we’re unconsciously subscribing to one very limited story about inequality—the nonrich aspiring to be like the rich—over and over. But I’ve experienced a second story: that of the nonrich aspiring simply to live. Working a lifetime, just so as not to get screwed over by a health care industry that can easily eat away any savings and bankrupt them without any real social safety net in place.