The Paris Review's Blog, page 128

January 15, 2021

Staff Picks: Heaven, Hearing Trumpets, and Hong Sang-soo

Still from Hong Sang-soo’s Woman Is the Future of Man. © Arrow Films. Photo courtesy of MUBI.

I’m a big fan of the films of Hong Sang-soo, and something about them—their long, lingering scenes in bars, the conversations that trip over art and love and the differences between the sexes—feels particularly right for this moment when many of us are stuck indoors. Luckily, MUBI is running a series dedicated to his work, including 2014’s Hill of Freedom (a personal favorite, which follows a Japanese man as he wanders through Seoul trying to find a lost love, but is really about the unreliability of narrative) and 2004’s Woman Is the Future of Man (which I had never seen before), his first film to open theatrically in the U.S. Hong’s films are deceptively simple, seemingly a series of variations on a basic theme—romantic drama, alcohol, unreliable narrators—but there are always a few formal twists, a playful approach to the concept of linear time, to keep the viewer on their toes. —Rhian Sasseen

Hello! It’s good to see you again. But why are you reading staff picks when you could be watching the all-star panel Community Bookstore organized to celebrate the NYRB Classics reissue of Leonora Carrington’s The Hearing Trumpet? By no means do I intend this as a knock against staff picks; as usual, my colleagues have delivered excellent recommendations, and I encourage you to read (and act upon) each and every one of them. But with a lineup like this—Chloe Aridjis, Kathryn Davis, Danielle Dutton, and Merve Emre, all brought together by the globe-flattening power of Zoom—perhaps you’ll understand the urgency of my question. I’d greatly appreciate if you considered, at the very least, opening the discussion in another tab of the internet browser of your choice; this can be done at no cost to you beyond the paltry fraction of a calorie burned in the action of a click. —Brian Ransom

Eimear McBride. Photo: © Jemma Mickleburgh.

Long ago, I picked up Eimear McBride’s A Girl Is a Half-Formed Thing based on the title alone and got only a few pages in before setting it down. I was in those preteen years when you suddenly start thinking of yourself as a capable, mature adult and are always desperate to prove it—or maybe that was just me, using words I half-understood, reading experimental literature. Despite my trying, the prose remained elusive. I had overestimated myself as a reader, I realized, and could not parse the dense stream-of-consciousness narrative enough to make sense of it. Recently, though, inspired by the dynamism of Sarah Crossan’s experimental novel Here Is the Beehive (and emboldened by my grasp of it), I found A Girl Is a Half-Formed Thing on my shelf and made a new attempt. Eschewing the familiar rules of punctuation, grammar, and sentence structure, McBride doesn’t make the reading easy, but without the constraints of convention, such gorgeous syntax is allowed to emerge, which makes the perplexity more than worth it. Phrase after phrase both challenged and enamored me, an intricate negotiation I was not ready for all those years ago. Structurelessness and Joycean experimentation aside, I’m not surprised I couldn’t decipher McBride’s novel when I was younger. After all, it’s a coming-of-age story, and what did I know of that back then? —Langa Chinyoka

In the 2019 short film Men of Vision, a failing veteran inventor and a quietly brilliant new inventor cross paths thanks to a shared mentor. This period piece has plenty of jokes about inventions relating to the shortsightedness of human beings and our inability to anticipate the future. As a child, I would dream up contraptions and mechanisms with little use or value outside my own little world, but I never took any steps to actualize them. Dreaming about possibility is natural, I suppose. But Men of Vision warns about the narcissistic hunger born out of egotism and possibility. Instead of majestic flying trains, our fixations may lead us to magnetic candles. —Carlos Zayas-Pons

I wonder if there’s something about Texas that makes memoirists of its writers. Emerson Whitney’s Heaven begins in “Old Texas like in the movies … where dip tins make circles in everybody’s back pocket.” Thematic comparisons could be made to the work of Mary Karr, but Whitney stands as a deft executor of their own unique style. Like a patchwork quilt, Whitney sews memories tightly together with Maggie Nelson, the DSM, and etymology. But for being so learned, the book is never didactic, and for being peripatetic (we do leave Texas), it feels solid, is emotionally even-keeled even across the stormiest subjects. Whitney is a writer who guides with an intuitive vulnerability and honesty, and at its core, Heaven is an examination of the body as an inherited thing. —Lauren Kane

Emerson Whitney. Photo courtesy of Nectar Literary.

January 14, 2021

No One Belonged Here

In 1974, Bette Howland (1937–2017) published her first book, W-3, which details her stint in a Chicago psychiatric ward. In the ensuing decade, Howland would release two more books and receive a MacArthur Fellowship. Soon, however, like many brilliant women of her era, she fell out of print. Thanks to the efforts of A Public Space Books, Howland’s work has resurfaced for contemporary readers; 2019 saw the publication of Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage: The Selected Stories of Bette Howland, and this week marks the reissue of W-3. An excerpt from W-3 appears below.

Bette Howland. Photo courtesy of A Public Space Books.

Iris had posted herself in the lounge with her cigarettes, emery boards, and stationery, writing letters on a silk-trousered knee. One hand fanned and fluttered the while, drying her nail polish. She was new to W-3; arrestingly tall, white faced, with frosted gray bangs and a black Nehru jacket buttoned to her chin. But her eyes were smeared; her pasted lashes sank like weights. In other words, like the rest of us, she seemed untidy. We were looking for such signs, of course: What’s wrong with her? Why is she here? “Here” being the small psychiatric ward of the sprawling university hospital.

On the windowsill there would be some withered, dusty plant, long dead, still wrapped in bows and silver foil from the florist’s: inmates received them rarely. Magazines accumulated all over the place, discarded heaps, old Times and Newsweeks mostly; no one read them. The cupboard was crammed—boxes of puzzles, games protruding from every angle. All those boxes would have tumbled down at once if anyone ever attempted to disturb them. No one ever did.

The manifestation, therefore, of a stylish middle-aged woman in lounging pajamas, dashing off her correspondence and doing her nails, should have been tip-off enough; this was no place for such ordinary pursuits. But it seemed, after all, normal. Supremely.

Iris described herself as a “manic-depressive of twenty-seven years’ standing.” This, the first thing next morning at community rounds when, as a new patient, she was called upon to introduce herself to the group. For most, such a request could only come as a shock—at least it had for me. But in Iris I detected no hesitation and no irony either.

“Do I stand?” was all she asked.

No, she could sit. She straightened her shoulders, cleared her throat, and launched promptly and forcefully into an account of her life from age twenty-one—her first diagnosis. Her voice was strong, imposing, like her presence. She was counting on the platinum tips of her fingers. It was plain that she meant to begin at the beginning and to leave nothing out.

This was not the customary response. This was a power play. Iris was claiming seniority, like a bird in a barnyard. Too bad other patients—less seasoned—were too inexperienced to appreciate it. But it wasn’t aimed at us, other inmates, anyway; this was directed at the doctors. Iris was not taken in by all this community stuff, the illusion—successfully maintained with a good many of us—that it was our relationship with other patients that was of importance to us, that was going to help us. She had been around long enough to know that her survival in a mental ward depended upon her status with the doctors. They were the ones who doled out the pills, the passes, and finally, the discharges. She knew the score and she was letting them know.

She was stately, strikingly erect. Her eyes were an indelible cosmic blue. She ticked off her fingers, arching them backward. Twenty-seven years to go! But we were glad to let her talk; it meant we wouldn’t be called upon, wouldn’t draw fire; we could be safe, we could be private, even, while Iris told us the story of her life.

We had many meetings. Patients’ meeting—our own self-government with duly elected officials—two nights a week; team meeting, a smaller, more intimate group, one or two afternoons; and this one, community rounds, the first thing after breakfast every morning except Sunday.

Rounds—that’s a hospital word, part of the doctors’ daily routine, checking up on all their patients. But this occurs to me only just now—obviously I didn’t figure these things out right away. You figured nothing out; you accepted. At first these words, names—everything seemed to be named—had a brash strangeness, the strangeness of the surroundings. The brashness perhaps in the mind, a bright, stunned state; everything rang out audaciously, like solid brass. If you have swallowed a lethal dose of sleeping pills, your experience moves from the plane of the particular to the general. I didn’t understand this yet. Still, the surroundings were strange, all the same. Meetings? Why meetings? In this place?

This was the situation I had found myself in, my first morning on W-3; a newcomer, just delivered, sitting in the lounge and waiting for rounds to begin, clutching to my lap a little flat gray box of tissues—boxes distributed liberally all over the ward. Weeping was mightily encouraged here. I did not much feel like weeping, but wasn’t so sure either that a sudden cloudburst might not overtake me. The prevailing winds being uncertain. I felt doubtful and uncertain about my appearance, too. My arms and legs were covered with sinister bruises and my hair had been clipped—shorn, skinned practically—like when I used to have lice as a child and got my head dunked in kerosene. I was wearing a short bunchy housecoat of faded terry cloth, and a pair of wide—gaping—pink slippers. They were several sizes too large to begin with and already well stretched with wear. Whose wear? I didn’t know where these items had come from, but they were all I seemed to have; and I had been forewarned: on W-3 all inmates were expected to wear “clothes.” This had me worried. But it meant, apparently, anything that was not hospital garb—no uniforms.

That did not make the disorderly assortment I saw around me any less drab. Patients in nightgowns, pajamas, robes, wigs, wraithlike in towels heavily draped over their heads, with sleepy, hanging faces, were finishing breakfast and reluctantly dragging chairs across the dining hall into the lounge. The plastic armchairs and sofas were already filling up; doctors were seating themselves, parting the tails of their long white coats. While we waited, I contemplated my feet resentfully in the loose pink slippers.

Perhaps once a month an inmate turned up with a voice like mine; invariably an attempted suicide who had spent several days in a coma in the intensive care unit before being transferred. Everyone knew what it meant. The coughing machine with its snorkels and seething mists rolled down the corridors, seeking me out. The coughing must have sounded like terminal agonies—like my voice. But inmates who had been around long enough recognized and accepted these peculiarities immediately. They nodded as soon as I opened my mouth: Zelma had had “that voice”; she had been trailed about by “that machine.” Zelma had been released only a few days before I came—though she had promised to return. And now there was me.

I should explain right away that I didn’t belong here. But that goes without saying, no one belonged here. That was the ordinary, the average, you might say the normal, reaction. On W-3 you encountered the terrible force of a generalization, and it had to be resisted, the self had to be exerted. Anything to deny this grim, inert, collective state.

The first thing I noticed was the uniformity of appearance, the carelessness of expression, dress. Everyone looked essentially the same—peculiar. Peculiar was what I expected everyone to be. So that seemed to be the explanation for these first impressions. I didn’t understand that we were all in the same straitened circumstances. You don’t get much notice for a trip to a place like W-3; there’s no chance to pick and choose, to pack your bags and powder your nose. All of a sudden your number is called, you are claimed; you pick yourself up and come as you are.

There was another, more powerful, explanation for the general aspect of negligence—and that was the drugs. Drugs were far and away the most pervasive fact of life on W-3, but I didn’t know that yet. I was not put on drugs automatically because of the medication I was still taking for my lungs. (I had a touch of pneumonia, not an uncommon occurrence here either.) So I was seeing them in action—a rare privilege, for a patient. But I could not account at first for the slurred voices, thick-tongued faces, the strange, uniform shrugging indifference. It horrified me. I thought it was the inmates themselves I was seeing, and that these people must be very different from me.

What if suicide is a sin? That is, to die benighted, in a state of total ignorance? If so, I had almost committed the sin, for I had come very close to dying—unhousel’d, unanointed, unanneal’d, no reckoning made but sent to my account with all my ignorance upon my head. That was the real truth of my condition, stripped to its essentials. I sat there, gripping my Kleenexes and gazing into my lap.

The room fell silent. Community rounds was about to begin. I looked up, ready and willing to pay attention; all this was new to me, and I was wondering what the meeting was going to be about. At once a freckled nurse with a blond ponytail and sweater sleeves knotted about her shoulders called upon me. Would I introduce myself? Would I tell everyone what I was doing here? This was a surprise! My neck was still craning with curiosity, but now, it seemed, I was to be the curiosity. Heads were turning, everyone was discovering me. The nurse, apparently presiding, was smiling at me encouragingly—indicating my whereabouts with an outstretched arm. She was doing this to make sure I knew who was meant: no one else was in doubt. All those other faces had turned on me like a shot. Raised without expression. Some fifty faces in a circle several rows deep. Some of these faces I had already encountered walking about the ward—fixtures of the place. So they had seemed. They now for the first time took on a dimension of recognition, familiarity.

An old fellow, a wizened black man with a fringed bald head, had swung his chair around and sat facing backward, looking away from the center of the room. I had noticed him earlier, at breakfast, smoking in the same way with his back to the table. “That’s poor old Jesse.” His long, powerful-looking arm moved across his chest, feeling in his shirt for matches; tufts of cotton stuck out of his ears. A small coppery-skinned black girl in a pink peignoir was curled up sleepily in an armchair, plucking large pink hair curlers from her head and dropping them into her lap. Deronda. I looked toward Deronda, hoping for a cue.

She yawned, cat’s slits, behind a fist of Kleenex. She knew what it was like. I would have to find out for myself. These faces, waiting, conveyed no information: they didn’t care one way or another whether I answered or not—just so long as, whatever I did, it took up enough time.

I didn’t feel like telling this bunch of strangers how greedily I had wolfed down a whole bottle of sleeping pills; or about the considerable time I had spent in livid imagination, laying my cheek to the greasy doors of cold gas ovens. I didn’t feel like telling them anything. I could explain, all right, but it would take too long. It would take my whole life. I could sense it behind me, cold, submerged, like an iceberg.

I declined to speak, on account of my voice.

“What’s the matter with her voice? Can’t she speak up?” A pair of long blunt sideburns; a compact, forceful body in a white lab coat. This was Dr. Lipman, the head of the ward; most patients called him “Lipton.”

“Is that why you’re here? You can’t talk? There’s something wrong with your voice?” Cigar smoke irritably surrounded him. He seemed to think this hoarseness was a symptom! But the voice was extremely characteristic; even other patients, in the midst of their own preoccupations, had grasped my situation without any difficulty. How come he, a doctor, didn’t know?

It never occurred to me that this was a ploy. I had had no experience to speak of with the psychiatric sector before; and anyway I felt new—tender. I think I was expecting some sort of moratorium at first. For things to be more gradual, or some sort of exemption to be made in my case. But moratorium, armistice, truce, respite—that was what you never got on W-3. You plunged right in, in medias res, and life went on twenty-four hours a day. This was the hardest thing to get used to. Since this life was so plainly arbitrary and unreal, it often seemed to me that there would be no harm in it if every once in a while the pretenses were dropped, the flag was waved, the truce declared. But that never happened.

I tried to explain: there was nothing “wrong” with my voice, I just didn’t have any.

“I can hear you,” the freckled nurse insisted, ever prompt. Ever cheerful. This mode of pursuit was to become very familiar.

“Well I can’t, dammit!” said Dr. Lipman, his starched coat scraping audibly as he shifted in his chair. His gruffness at least seemed more genuine; it really was impossible to hear me.

“Oh! I can hear her perfectly well! How about you people back there?” The blond ponytail spun about. “Back there,” the rows of faces nodded. It didn’t matter, they didn’t need to listen. Forty-five minutes had to be used up, one way or another—that was all that mattered.

These are not impressions after the fact; then and there I grasped the essentials. It was early yet, no one else seemed moved to speak; I could not be let off so easily. Time was our common oppressor.

“Why don’t you stand up?” the nurse suggested.

By this time I had already revealed anything anyone really needed to know about me. It never mattered what you said you were doing here. Some outward sign, some characteristic peculiarity, something all the rest could recognize right off—that’s what mattered, that’s what you were doing here. A certain point had been reached; no one had to hear how.

I must have seemed the only inquisitive person left in the room as I got—somewhat gropingly—to my feet, feeling for my Kleenexes, with my head poked to one side.

“There!” the nurse said. “Now everyone can hear you.”

Hear me! Hear me! But the voice that was coming from me was not my own voice! How could they hear me?

*

Each of us had a story—as long, as involved, as hoary as Iris’s—though few had the wind to launch into it. But Iris was overwhelming. After ten or fifteen minutes she was still strongly holding forth, her shoulders upright, her neck as stiff as ever in her black silk collar—still counting on her fingertips. And she hadn’t used up the first hand yet!

I looked around the room. Guz had folded his arms—white to the elbows with tape—and gone back to sleep, his big, deep, trustful body collapsed in the chair. His feet were sticking out in bloody socks. Simone stuck her hands above her bowed head, catching up on her prayers. Her long black fingers rippled with bones. This was always unsettling. At such times it seemed to me that she was the only one who had any real grasp of our situation. But one thing was clear: Iris was crating no tension, no interaction. Our “community” was suffering a relapse.

Night and day we were a “community”; the fact was relentless. THIS UNIT IS NOT TO BE USED AS A THOROUGHFARE—the sign on the thick glass door spelled it out. Though the ward was locked, our doors must be at all times open. Patients must have roommates; except for those in isolation (and they were envied for it, and for their locked doors), we were not to be alone. The little rooms with their dormitory bunks, colored bedspreads, plastic desk lamps were not to be a refuge. We were expected to be out, out in the communal areas of the ward: in the rec room, lounge, occupational therapy; gathered round the piano or pool or Ping-Pong tables (the eternal triumvirate of psychiatric wards); active, participating, colliding with life—life that was to be found somewhere out there and not in ourselves. Demonstrably not. The faces at our meeting were lifeless enough. Faces: present and accounted for. We were faces, not bodies and souls.

Dr. Lipman interrupted Iris at last, pulling on his glowing cigar: “We’ll get back to this next time.” “Next time,” Iris was put on lithium and fell silent. Disheveled bangs flopped on her brow—very distracting as she bent over her boxes of stationery, scribbling away. Her great smeared eyes were blank and cloudy, like cosmic dust.

Bette Howland (1937–2017) was born in Chicago. She was the author of three books: W-3, Blue in Chicago, and Things to Come and Go. She received a MacArthur Fellowship in 1984, after which she did not publish another book. A posthumous collection of her stories, Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage, was published in 2019.

Excerpted from W-3 , by Bette Howland, published this week by A Public Space Books. Copyright 1974 Bette Howland. Reprinted by permission of A Public Space Books

We Didn’t Have a Chance to Say Goodbye

Sabrina Orah Mark’s column, Happily, focuses on fairy tales and motherhood.

The Plague Doctor (Photo: Sabrina Orah Mark)

“I can’t find my plague doctor.” “Your what?” says my mother. “My plague doctor.” “I don’t know what that is,” says my mother. I text her a photo of my plague doctor in his ruffled blouse and beak mask sitting on my bookcase a few months before he disappeared. “I still don’t know what that is,” says my mother. “Forget it,” I say.

“If you want to find it then look for it.” “I am looking for it.” “Then look harder.” “I am looking harder.”

“It’s the strangest thing,” I keep saying. But I know it isn’t the strangest thing.

I tell everyone who will listen that I’ve lost my plague doctor. Nine months ago I wrote about seeing the small porcelain doll in a shop in Barcelona, and wanting him immediately. If he had been real his beak mask would’ve been filled with juniper berries, and rose petals, and mint, and myrrh to keep away a plague I thought belonged only to the past. This was ten years ago. My husband and I were on our honeymoon, and I thought I only wanted the plague doctor. I didn’t know I’d eventually need him, too. “You can’t be serious,” says my brother. “Who loses a plague doctor during a plague?” “I guess I do,” I say.

“We’ll find him,” says my husband. But we never do.

The only explanation is that he fell into a donation bag when I was cleaning out closets, and I accidentally dropped him off at Project Safe. “That is not the real name of the thrift store,” says my brother. But it really is the real name: Project Safe. I imagine my plague doctor at the bottom of a bag of old shoes calling for me. The news keeps breaking. The number of dead keeps rising. I go on Project Safe’s Facebook page. I offer a reward. I will pay whoever bought him five times what they paid. I will donate to the charity of their choice. I will sail across the sea in a paper boat with my pockets full of dried rose petals and fresh air and ancient coins to lure him home.

The manager of Project Safe puts a photo of my plague doctor up by the register. She understands, she tells me, what it feels like to lose something. I feel grateful and ridiculous. The news keeps breaking. The number of dead keeps rising.

I even looked behind the curtains. I even looked in the piano.

The plague doctor is not the only thing I’ve lost since the pandemic began. The longer I am in my house, it seems, the more things I lose. As if there’s a correlation between the hours I inhabit my house and its contents disappearing. “I could’ve sworn I put my copy of Virginia Woolf’s The Waves right here.” “Haven’t seen it,” says my husband. “I’ll help you look,” he says. I look over at our sons. Their rosy cheeks seem to have been replaced by the color of the living room. Is this the year they were supposed to learn all the major rivers? Or is it the year they were supposed to learn how to find the hypotenuse of a triangle? I could spend months going around this entire house picking up everything that’s now lost. I tell my neighbor, the scientist, I’ve lost my plague doctor. But I don’t think he hears me. We’re standing too far apart.

My husband leaves the book he is reading, Journeys out of the Body, open on our bed. “That’s all we need,” I mutter to nobody. I imagine the plague doctor and my husband holding hands on the back of a milk carton. I imagine a toll-free number underneath them in numbers printed so small it could easily be mistaken for pinpricks in the carton, the milk leaking out so slowly it’s barely noticeable until it’s gone.

I tell our mail carrier I’ve lost my plague doctor. “Of course you have, dear,” she says. “Everyone loses their plague doctor.” Her hands are small and covered in plastic gloves or fog. She gives me my mail. Nothing is addressed to me.

Sometimes I hear my husband’s footsteps coming up the stairs and I think he’s about to knock on my office door with the plague doctor safe in his arms.

What I’m trying to say is that I’m mourning something nameless that has vanished into thin air, and I’m calling it my plague doctor. What I’m trying to say is that we didn’t even have a chance to say goodbye. We should’ve at least had the chance to say goodbye. Goodbye, plague doctor! Goodbye, old world! The plague doctor is what I’m holding so I can hold what I’m grieving. Or rather, what I’ll never hold again.

I tell Bruno Bettelheim I’ve lost my plague doctor. “A child,” he says, “needs to understand what is going on within his conscious self so that he can also cope with that which goes on in his unconscious. He can achieve this understanding, and with it the ability to cope, not through rational comprehension of the nature and content of his unconscious but by becoming familiar with it through spinning out daydreams—ruminating, rearranging, and fantasizing about suitable story elements in response to unconscious pressure…” “Excuse me, Bettelheim, for interrupting you but what do you think I’m trying to do here?” Bettelheim looks around. “You lost your plague doctor,” he says. “Vanished into thin air,” I say. A sadness, like a mask, falls over his mouth. His mouth is so beautiful. “I miss mouths,” I say. “I miss my plague doctor,” I say. “I miss stupidly believing history was lived mostly in the past. I miss not being afraid … Bettelheim?” “Yes?” “When will my sons be able to return to their childhoods?” Bettelheim looks at his wrist where a watch should be. “I could’ve sworn I was wearing a watch,” says Bettelheim. The news is breaking. The number of dead keeps rising.

“The child,” says Bettelheim, “fits unconscious content into conscious fantasies, which then enable him to deal with that content.” “Like storing my grief inside a figurine?” I ask. “Yes,” says Bettelheim. “It is here that fairy tales have unequaled value because they offer new dimensions to the child’s imagination … the form and structure of fairy tales suggest images to the child by which he can structure his daydreams and with them give better direction to his life.”

“Which direction are you walking Bettelheim? I’ll walk with you.” We walk slowly down empty street after empty street. Bettelheim stops at a trash can and looks inside. “You never know,” he says.

Other than this fairy tale that is not a fairy tale but the true story of my missing plague doctor, I can’t find a fairy tale in which an object vanishes with no explanation. Even the girl with no hands grows back her hands. Cinderella’s glass slipper is never really missing, and when the prince disappears we know the whole time we can find him inside the beast. Even the darning needle, which breaks and falls down the drain and floats away with the dirty gutter water and is found in the street by schoolboys and is stuck in an eggshell and is run over by a wagon, is never out of our sight. Everything in a fairy tale has already been lost. The fairy tale is where we go to find it again.

I never find my copy of Virginia Woolf’s The Waves, but if I had I would’ve copied this down: “I need silence, and to be alone and to go out, and to save one hour to consider what has happened to my world, what death has done to my world.” I want a lost and found in my living room manned daily by Woolf. A small booth with a sliding window. Tap, tap. Woolf slides the window open. “State your missing.” And I state my missing. Obviously she never returns anything. But just hearing her sort through the missing is a comfort.

My husband buys me a new plague doctor who is twice the size of my missing plague doctor. Big enough for my missing plague doctor to possibly be hiding inside. Around the new plague doctor’s waist is a crescent moon, and from it hangs a lantern, and keys, and an empty birdcage. He is so black and slender and beautiful he could easily be mistaken for my plague doctor’s shadow. He is like the grandmother who comforted me when my grandmother died.

“We wanted to hold,” writes Heather McHugh, “what we had.”

“I left you a surprise,” says Eli, my seven-year-old. On my desk is a plague doctor made out of clay with a note: “Plage Dok.” On its chest is a bright pink heart. Now there are two doctors. One made of shadows, and one made of clay. What we lose is also what we gain. I turn on the faucet and out gush more plage doks. I fill up my glass and I drink and I drink. In the glass the plage dok’s letters rearrange themselves like cells: gold lake, pale opal, old page, aged god. I pull each word from the glass, and carefully dry them before they fade. “What’s that?” asks Eli. “Another story?” “I hope,” I say. “What’s it about,” asks Eli. “I think it’s about saying goodbye.”

Read earlier installments of Happily here.

Sabrina Orah Mark is the author of the poetry collections The Babies and Tsim Tsum. Wild Milk, her first book of fiction, is recently out from Dorothy, a publishing project. She lives, writes, and teaches in Athens, Georgia.

January 13, 2021

Being Reckless: An Interview with Karl Ove Knausgaard

Read an excerpt from In the Land of the Cyclops here.

Karl Ove Knausgaard’s newest release, In the Land of the Cyclops, is a collection of essays and reviews translated from the Norwegian by Martin Aitken and published in the United States by Archipelago Books. The title essay, first published in a Swedish newspaper in 2015, is an enraged response to a critic who asserted that Knausgaard’s depiction of a relationship between a teacher and a student in his first novel was pedophiliac. Knausgaard argues forcefully that explorations of all human impulses are necessary, and touches on many of the themes that have lately become associated with his body of work: Nazism—which forms a central plank of Book 6 of My Struggle—identity, literary freedom. While Knausgaard is a writer who is provocative in both the scope and the theme of his work, his politics resist neat categorization: “All my books have been written with a good heart,” as he puts it in this essay, perhaps conveniently. And despite the provocations of its title essay, the book is really a cabinet of Knausgaard’s curiosities. His interests lie in visual art, destabilized reality, meaning, and perception. There are pieces on topics as disparate as the photography of Sally Mann and Cindy Sherman, the perfection of Madame Bovary (“Madame Bovary is the perfect novel, and it is the best novel that has ever been written”), and Knut Hamsun’s Wayfarers. The Bovary essay seems to contain the key to the collection, to the extent that there is one: Knausgaard describes Flaubert’s book as a novel “which is about truth and which asks what reality is.”

About Francesca Woodman’s photographs, which he first dismissed, he changes his view: “Why did I find Francesca Woodman’s photographs, youthful as they were in all their simplicity, so relevant now, while those great paintings of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries suddenly and completely seemed to have lost their relevance to me?” A review of Michel Houellebecq’s Submission, a novel by an author who is a byword for outrage, is about “an entire culture’s enormous loss of meaning, its lack of, or highly depleted, faith.”

The pandemic poses problems for book tours, and Knausgaard, according to his publisher, hates Zoom. We corresponded via email at the dawn of 2021.

INTERVIEWER

The title of your new collection is used as a derisive descriptor for Sweden. Sweden also appears at length in Book 6 of My Struggle, as a figure of scorn for what you describe as its failed, hypocritical social policies. In America, on the Left, there is a fantasy of a sort of single, undifferentiated “Scandinavia” that has wonderful social programs and proves that capitalism can exist along with strong social supports. But during the pandemic, Sweden made choices that did not seem to be in keeping with that reputation. How does the pandemic response align with or recalibrate your ideas about Sweden?

KNAUSGAARD

I would say that there was a certain one-eyedness in Sweden’s approach to the pandemic. They did it their own way without looking to other countries. Even when the death rate in the country was ten times higher than that of the neighboring countries, they continued to do it their way. Having said that, we don’t yet know for sure why some countries have been hit harder by the pandemic than others. But Sweden’s approach wasn’t out of character for sure.

INTERVIEWER

How has the pandemic affected your daily life and movements?

KNAUSGAARD

I have lived full time in London for two and a half years now. Being a writer, I have always worked from home and lived in a kind of permanent lockdown, so the pandemic didn’t change much in that sense. The big difference was that everyone else in the family also stayed home. It worked remarkably well, though; most of the children did online schooling, but it was still a lot of things to do, so I got around four hours a day for writing. Weirdly, I wrote the major part of a novel that spring. I guess that came about because of the time limitation, I couldn’t afford to sit there and think, I had to get the writing moving. The novel was published this fall in Norway. I still can’t get my head around the nature of the pandemic, however, with all the suffering and the horrible number of deaths taking place out there, in the very city we are living in, at the same time as we are indoors, cooking, playing games, and spending more time together as a family than ever before. Somehow, that double perspective found its way into the new novel. It is not about the pandemic, though, but the experience of it must have played a part.

INTERVIEWER

I saw in one interview that you quit smoking, started up again, and then as of 2018 you were back off smoking. What’s your smoking status now?

KNAUSGAARD

Still smoking, unfortunately.

INTERVIEWER

One thing I find interesting about your work is that it is quite often about politics, but your positions on specific matters are usually elusive (“I long to be free, totally free in art … if we look at a picture of a tree, we are immediately caught in a net of politics and morals”). In your essay about Knut Hamsun, you say, “He despises the mass, but not the people who belong to it,” and you, too, seem to privilege the individual rather than the collective. As Jon Baskin points out in his essay about your work, you seem almost to be more suspicious of any feeling of “we” or “us” than of the actual ideas that create that collective feeling (your essay about Anders Breivik in The New Yorker, for example, more or less dismisses his political ideas as a motivating factor in his crime). Have your thoughts on this changed in the last few years, watching the refugee crisis and the response in Europe, or Donald Trump’s election in America? Are the ideas that can unify and animate a group irrelevant?

KNAUSGAARD

This isn’t as easy as your question make it sounds. The one unifying political idea in Europe at the moment is the right-wing usurpation of the we, that is based on the exclusion of immigrants and foreigners. The biggest party in Sweden now is the anti-immigration party, Brexit can be seen as an anti-immigration movement, then you have Hungary and Poland, and Trump came to power with a strong us-and-them rhetoric, didn’t he? The good thing about the Scandinavian welfare state has always been that it has created a feeling that the society belongs to us. They are our hospitals, our schools, our roads and railways, even our politicians. That requires a certain consensus, and that consensus, however necessary, can also lead to exclusion (in Sweden, an exclusion of different opinions, in Norway, an exclusion of the world). So to insist on idiosyncrasy is a way of keeping the “we” open, not closing it down, as your question seems to indicate.

I think that is something all the artists and authors that I write about in In the Land of the Cyclops do. Art is about transgressing the expected, not confirming the world as we know it. Cindy Sherman’s photos are a good example. In some of them she juxtaposes man and woman, flesh and dead matter, fiction and reality, and through that, we can get a glimpse of the boundaries that keep our world together and that we do not normally see, because they are the world to us. Regarding what I have written about Breivik, the essence is actually the opposite of what the question states: the massacre was only possible because of his isolation, the lack of possible corrections, the lack of a real “we.” He operated with a fictitious, or virtual, “we,” in which he was a hero, a defender of Western values. But there was no one else there. He was alone, unavailable for correction. What he did was in my opinion much more related to American school shootings than to political terrorism. In both, there is a lack of belonging, a lack of togetherness, a loneliness. Those pockets of disconnection in society are dangerous, just as extreme polarization is also dangerous. It is created by a lack of hope, a lack of future, a loss of dignity—then another, stronger, simpler identity is taken in their place.

INTERVIEWER

The eponymous essay in this collection was a response to a criticism of depravity leveled at your work. You also write, in the essay “Inexhaustible Precision,” about a critic who, hilariously, positively reviewed your debut, and then retracted the review and wrote a critical one. Is there a response to your work, whether critical or positive, professional or from a lay reader, that has moved you or otherwise stayed with you? I’m curious if, among other things, you hear from readers about your very deft and compelling depictions of parenting. Is there criticism that consistently stings?

KNAUSGAARD

The reviewer who first wrote the novel up and the next week changed his mind and tore it down was unexpectedly honest, and the phenomenon, interesting, not least because I recognized the feeling. I have been mesmerized by books myself, only to find them shallow a few days later, like I have been manipulated. And manipulation is, somehow, a part of the novel-writing trade. At that time, after my first novel, I read everything that was written about me. I googled myself and was very unhealthily absorbed by it all. After my second novel, I stopped doing that. Now I never read anything about my books, neither reviews nor anything else. I learned that from a colleague, Majgull Axelsson. We were on tour together and she probably saw how tormented I was by all the press and then gave me some very good advice: never read reviews. Never read, listen to, or watch interviews, just treat them as nice meetings with interested people and go on. I have done so ever since. To avoid it completely is impossible, however—two days ago, for instance, I bought the Observer at the supermarket here, and when I opened the review pages, I saw my photo and the headline, “Now It Is Our Struggle.” Even if I closed it the next second, I got enough information to understand that it was a review of the essay collection and that it was probably a hatchet job.

But I found the headline funny, and there is nothing I can do about it anyway—the book is already written, and I am working on the next. I don’t know how to make them better, it is never like my writing improves from one book to the next, it is more that the limits are set, and the limits are your personality, the person you are. But improving the writing isn’t my goal, my goal is to make the writing go to new places, to explore things, to search for meaning, to look for the world. It is not about trying to write the one great novel. To me, all writing is the same, be it essays, novels, nonfiction, diaries, or letters. They all have some of that search in them. Of course you can improve technically as a writer, but at the end of the day, who cares about technique? It is a tool, not something to admire in itself.

One of the essays in the book is about Anselm Kiefer’s art, and I was lucky enough to see him work in his studio for a day. It was all process, all about movement, and he was so reckless with his work, which was constantly exposed to chance and arbitrariness. He is incredibly gifted as a visual artist, he can do whatever he wants to, and it was like the material, the matter itself, was a resisting force, something he wrestled with, so that his clever ideas stopped being clever and even stopped being ideas, but became works of art, which is something else. I have been thinking a lot about that since I was there. Edvard Munch was also reckless with his paintings, and incredibly prolific. I do like that a lot, that it isn’t about the one painting or the one book, the one color or the one sentence, but something that goes on and unfolds over years. It is a liberating thought.

So no, I have never learned from critics. But I have always had several readers during writing, the editors, of course, and my wife, Michal, but also friends and colleagues. What happens then is that the book gets more of an objective existence, which makes it easier for me to see it from the outside, what it is, and not only what I want it to be.

INTERVIEWER

What are you working on now?

KNAUSGAARD

This fall, I published a new novel in Norway called The Morning Star. The story didn’t end there, however, so now I’m writing the second novel, and there seems to be a third after that. It is very much fiction, with many different characters and also some supernatural elements in it.

Read an excerpt from In the Land of the Cyclops here.

Lydia Kiesling is author of the novel The Golden State.

Almost Eighty

In the summer of 2011, three months before her eightieth birthday, the playwright Adrienne Kennedy reflected on her life in the unpublished essay “Almost Eighty.” Now, nearly a decade later, with Kennedy’s ninetieth birthday right around the corner, the piece has finally been published in He Brought Her Heart Back in a Box and Other Plays , which Theatre Communications Group released in November . The essay appears in full below.

Adrienne Kennedy’s mother, Etta Hawkins (née Haugabook), 1928, while a student at Atlanta University. Photo courtesy of Adrienne Kennedy.

At almost eighty, I wondered if I could find reasons to live.

I kept begging my son to print out pages of my mother’s scrapbook, which was on his computer. Why?

All I knew was my eightieth birthday was in three months, and I was extremely sad. I had been at his family house in Virginia for a month, the month of June. For the first time I could not see how I was going to financially maintain my apartment in Manhattan, my beloved apartment on West Eighty-Ninth Street, an apartment I’d had for twenty-nine years, despite commuting to California and Boston, my precious home near the Hudson.

I seemed to lack energy, purpose. Dreams.

“Please print out mother’s scrapbook,” I begged. He was busy. The scrapbook was in the middle of other documents.

I didn’t know why but I kept begging. I wanted to see that scrapbook, started in 1926. I wanted to see all the glued-on photographs and programs that filled the pages until 1928. And from 1928 to 1954 all the photographs and newspaper articles that were stuck inside the pages of the scrapbook.

I’d already decided if I can’t find reasons to live, then what’s the point?

What can I embark on at eighty?

What could I possibly embark on?

“Embarking” had always been one of my mental mainstays.

Finally, Adam printed out my mother’s scrapbook that she started when she was a student at Atlanta University, 1926–1928. I felt it was my compass. My beautiful compass.

*

The Crimson Cover

The crimson cover with a border of green-and-pink flowers started a long line of my love of books with red covers. Today I possess a small red library. As a child the sight of this red cover made my heart beat faster. I remember the twelve-year-old girl in Cleveland, Ohio, who held the book with the red cover in her lap and dreamed of life to come, dreamed of the future. I still needed to dream of the future.

*

The Red Book, 1943

Lying on the top of the book had been a long photograph of the graduation, 1928, from AU. The two-year normal school education made it possible for women to teach. My mother’s first teaching job was in Florida, a white wooden-frame schoolhouse with about twenty children.

Then as I looked at my mother’s fellow graduates, I thought of these Black women starting out on their teaching careers. A common thought was that the “race” had to be educated. Education was the only way for a Black person to compete in American Society. Could I still educate?

*

In 2011

At the beginning of the scrapbook, stuck inside a page, was the 1928 commencement program.

Commencement was a word I’d always liked.

Commencement

Commencement

Commencement

What commencement would I join? I didn’t know. How can you begin when you’re eighty? My father died at seventy, my mother at ninety-two, my brother at thirty-eight.

*

Fellowship

My father’s Morehouse program was next to my mother’s. Morehouse College, 1928, he majored in social work. Perhaps I could still look forward to thinking of that young social worker who left Atlanta for Dayton, Ohio, and then to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where he worked for the K Clubs for boys, clubs formed to help youth in their goals, their problems, in overcoming the poverty they faced in 1929. The Clubs emphasized fellowship.

In 1929, fellowship was valued. I realized I could still look forward to thinking of these Negro boys in smoky Pittsburgh and my father and his young idealistic colleagues setting out to save the race. They sang at meetings:

Blessed Fellowship

Blessed Fellowship

Leaning on the

Everlasting Vine

Blessed Fellowship

Leaning on the

Everlasting Vine

At seventy-nine, I still have the Everlasting Vine to lean on, and always will.

The original paper of the scrapbook is a pale beige heavy paper with a border of green leaves, green leaves to frame your thoughts. There is a forest of green leaves that surround this Virginia house that my son lives in with his family. I realize I can smell the soil, see different shades of green hedges along the stone path leading to the front entrance. Green leaves on this summer morning make me think of the green mint bushes we had in our backyard in Ohio and the taste of them in my mother’s iced tea.

Green leaves make me think of the maple tree my father planted on the tree lawn of our house.

There is always a commencement of green leaves.

*

Lakes, Rivers, Streams

There is a photograph (1928) of my father in a lake sitting in a rowboat. He is wearing a white shirt and is somber. He is about twenty-four years old. He appears to be in the middle of a lake in Georgia.

Lakes. Lakes. How I love lakes. In Cleveland, we lived close to Lake Erie, the part of the lake that flowed between the shores of Cleveland to the shores of Canada. When I was thirteen, my neighbor took me on a cruise across Lake Erie to Canada. It was on a white boat, and my friend Rachel, her aunt, and I ate sandwiches and drank Coca-Cola. It was my first boat journey.

I had been on the lake in Aurora, Ohio, at camp. I had been in a rowboat on a lake with water lilies. Lakes. Rivers … The Hudson River, which I have loved since I first saw it in 1955 and have lived near since. My son’s family lives near the James River.

Lakes, rivers, the streams that bordered the Faculty Club in Berkeley, California, where I lived often during the eighties …

Even if I am almost eighty, I can still see Rivers. I can still quote Langston Hughes: “I’ve Known Rivers.”

*

The Great Lakes

It made me happy that as a child I lived on the Great Lakes. Lake Huron, Lake Michigan, Lake Ontario, Lake Erie. I can still be inspired by the sound of the words and the pride I felt at being amid the Great Lakes. In Manhattan I can still walk to the Hudson, and in Virginia I can still walk along the banks of the James River in the sun.

*

In the Scrapbook

The words are written in Blue Ink.

Blue Ink

Ink Jar

Fountain Pens

I have a love for all three, there is a joy in looking at handwritten words in blue ink. We read blue ink, from ink jars in inkwells once upon a time. You filled your fountain pen with blue ink. I still have one fountain pen. A gift from Signature Theatre Company.

*

Aunt Rena

Rena Dickerson. She wasn’t really my father’s aunt but a woman in Atlanta who lived near Morehouse in the twenties. She and her husband let Morehouse boys board at their house, and my father said she gave him and other students free meals, especially on Sundays.

I didn’t meet her until I was twenty-two. She had long since left Atlanta, been widowed, and lived in New York in a brownstone with her cousins. However, she lived in Brooklyn only on her days off. Her regular job was as a cook on an estate in Greenwich, Connecticut. My husband, Joe, our son, Joseph Jr., and I once in 1955 on a Sunday afternoon went to visit her in Greenwich. (At that time we lived at Columbia University in Bancroft for married students.) On that Sunday in 1955, Aunt Rena was buoyant, fashionable, and filled with information about New York City. She told me the only store I should shop at was Bloomingdale’s.

But I first met Aunt Rena in 1954, a year earlier. That year, a new baby, back living at home in Cleveland with my parents. Joe was in Korea. Aunt Rena came to Cleveland to the World Series.

She got up at four o’clock in the morning to go down to the stadium to get in line for tickets. She practically ran along our sidewalk to me—amazing because I saw her as old. “How old is Aunt Rena?” I asked my mother …

Aunt Rena was so thrilled, energetic, and happy, had traveled from New York City to Cleveland. And the night before had made a gigantic pot of chicken and noodles.

“Rena’s way up there,” my mother said. “Rena’s in her late seventies.”

*

Photographs

My parents in Atlanta when they were sweethearts.

They are standing near the steps of a brick home, she in a print silk dress with a pleated skirt. He has on a college sweater with an M (that I still have), knickers, and a baseball cap.

Silk dresses, prints with pleated skirts. When I was an adolescent in the forties, my mother picked out dresses for me with pleated skirts. She continued. The dress I wore for going away after my wedding was a shantung dress (she picked out) with a pleated skirt. She had continued.

*

Continuing (The Box Camera)

Until the sixties when it vanished, my mother had a box camera that she had owned since the thirties. She photographed rare events like visitors from Detroit or old friends from Akron, Ohio. These were people from their early days in Georgia, there was cousin Edith from Chicago. These people: cousin Hattie from Detroit, the Humberts from Akron, were born around 1900, came North to pursue tirelessly, relentlessly, and continually education, professions, racial equality.

Embarking on a journey was a theme that permeated my parents’ and their friends’ conversations. We’ve come a long way. We still have a long way to go. But we’ve come a long way.

They’d say: “I remember just four years ago we couldn’t eat at Schrafft’s in Downtown Cleveland. Before the War it was unheard of that Negroes would be living out here in Glenville.”

Did I still have a long way to go? Maybe a long way to learn how to continue.

*

Scrapbooks

The red scrapbook led to my own love of scrapbooks, love of photographs, passion for writing on pages in blue ink, writing thoughts on pages in blue ink about the days, events, the significance of a day.

I must continue to remember the significance of a day.

*

I think of: Morehouse College/History/War Against _______

Martin Luther King Jr. and his father, Daddy King, went to Morehouse College. Daddy King and my father were there at the same time. Martin Luther King Jr., along with Nelson Mandela, are leaders I admire beyond words … Purpose, fighting wars, struggle.

I must still be a part of the struggle. Perhaps history still needs me, so those before me won’t be forgotten, obliterated.

*

Poring

I had published stories, plays, taught at UC Berkeley and Harvard; of course I had two sons by my only marriage and five grandchildren. But I could not see any future, a future with verve, hope, excitement that I’d once had.

I still wondered why I had begged Adam to print out the scrapbook. Why had I always pored over the pages, constantly gazed and imagined, curiously?

I realized poring curiously over pages was a trait I still possessed. I was still in possession of my curiosity.

*

In 2011

It’s now clear to me that in her scrapbook my mother was gluing together a society, joining, adhering meaning.

*

Gazing and Imagining

1943 was the time at age twelve I climbed the steps of the attic in our house to sit on the floor, after I’d taken the red scrapbook out of the old dresser drawer. The attic smelled of furniture polish, old wallpaper, the old wardrobe trunk with drawers pulled out still with ancient gloves or a hat. There were broken dishes on an old chest of drawers. A small window faced the maple trees along the street. The floors were polished. The former family’s grandmother had lived on this floor. I’d sit often in summer, gaze at the pages, and imagine ATLANTA.

At the same time, I started my own movie star scrapbook. In my movie star scrapbook, one of the pictures I studied again and again was a picture of Elizabeth Taylor in Life magazine. She was sitting in her bedroom in Hollywood. We were the same age, and I longed to be and to look like the little girl she played in Jane Eyre. Her name was Helen. When the cruel headmaster punished Jane Eyre, it was Helen who cried out in her defense, and it was Helen who was made to walk in the cold rainy courtyard of the Yorkshire, England, school with a weighted board on her shoulders. She died later that night. She had shown devotion and courage.

2011, this spring, I took out my scrapbook and gazed at the Life magazine photograph. I thought: I could still show devotion and courage. I could. I can. My family needs my devotion and courage, and for me to imagine a future with them.

On the back of the Life magazine pages were pictures of World War II in France. One of the great historical world struggles.

*

Gluing a Vision

I see one of the reasons I begged Adam to print out the scrapbook. I longed for the vision contained in the songs, the poems.

Invictus

Out of the night that covers me,

Black as the pit from pole to pole …

*

The Vision

… the romantic images, these two Atlanta students, young Negroes going North. The romantic girl who pasted programs, napkins, tickets, wrote: “I saw my sweetheart today.”

*

She Glued Together: A Concrete Vision of a Wonderful World

The words:

Vespers

Eventide

Baccalaureate

Nearer My God to Thee

Salvation

She Walks in Beauty

Friendship

Fellowship

Jesus is my friend

He walks with me and He talks with me and He tells me I am His own

I shall pass this Way but once

Scripture

Morning Service

Heaven on Earth

Remembrance

The song “Throw Out the Lifeline”

*

Gluing a Story

The red book glued together a story, a vision of beauty, romance, friendship with the language of a nineteen-year-old girl.

… the romantic couple on the grass would one day quarrel, part, and fight bitterly over the questions surrounding the death of my brother, their only son.

In 1943. Climbing the steps of the attic I was seeking answers. I must still seek … “Vespers,” “Eventide,” “She Walks in Beauty.” I must still seek “Throw Out the Lifeline.”

*

In 1943

Alongside the red book, rolled up in the drawer, was my mother’s diploma, from Fort Valley Boarding School.

Before Atlanta University, my mother had gone to boarding school. Her father sent her to the school.

Her mother was dead. She lived with her grandmother who worked away at Warm Springs, Georgia. And who my mother said was mean to her. My grandfather, a white landowner, sent my mother to Fort Valley. On holidays the headmaster of the school invited her to his family’s house. She told me she was lonely and sought refuge in books. Fort Valley School imitated English boarding schools in the content of lessons and, as well as they could, in the decoration of the interior of the school. Many or most of the books and furnishings were given to the school by wealthy whites, the population of the girls school was, of course, all “Negro.”

My father was from the same Georgia town, Montezuma. My parents had known each other since they were children. He had been at Morehouse Academy since he was twelve. My grandmother, a servant, dreamed of him being “somebody.” His father, who sold fruits and peanuts on incoming trains, had disappointed her. My father always had jobs at Morehouse, and my grandmother and her sister, also a servant in the same household (owners of a canning factory), sent my father clothes, dollars, food. People in the town said, “C. W. was going places.” After the Academy he went on to Morehouse College. He was popular, played baseball, and wanted to “lift his race up.” He majored in social work. Summers, Morehouse sent him to the tobacco fields in Connecticut to earn money, and he spent one summer at the New York School for Social Work in Manhattan. They were together a young teacher and a young social worker seeking the perfect and equal American Life. “Helping the Race was primary.”

I see I can still seek the perfect life. They also sought God. I can still seek God.

After 1928, the photographs and newspaper clippings, mementos, continued, folded inside the red book. She continued recording wonders, parties, banquets, church events, school events, napkins from her bridge club meetings, poems from the Cleveland Plain Dealer, and I must continue.

Adrienne Kennedy has been a force in American theater since the early sixties. She is a three-time Obie Award winner for Funnyhouse of a Negro (1964), June and Jean in Concert (1996), and Sleep Deprivation Chamber (1996), and she is the recipient of an Obie Award for Lifetime Achievement. Kennedy was inducted into the Theater Hall of Fame in 2018.

“Almost Eighty” appears in He Brought Her Heart Back in a Box and Other Plays , by Adrienne Kennedy, published by Theatre Communications Group .

January 12, 2021

Redux: Then I Turn On the TV

Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

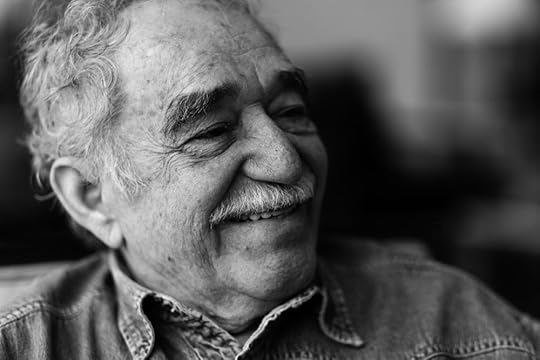

Gabriel García Márquez.

This week at The Paris Review, we’re thinking about newspapers, newsprint, television sets, and media. Read on for Gabriel García Márquez’s Art of Fiction interview, Peter Mountford’s short story “Pay Attention,” and Anne Waldman’s poem “How to Write.”

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, and poems, why not subscribe to The Paris Review? Or take advantage of our new subscription bundle, bringing you four issues of the print magazine, access to our full sixty-seven-year digital archive, and our new TriBeCa tote for only $69 (plus free shipping!).

Gabriel García Márquez, The Art of Fiction No. 69

Issue no. 82 (Winter 1981)

I’ve always been convinced that my true profession is that of a journalist. What I didn’t like about journalism before were the working conditions. Besides, I had to condition my thoughts and ideas to the interests of the newspaper. Now, after having worked as a novelist, and having achieved financial independence as a novelist, I can really choose the themes that interest me and correspond to my ideas. In any case, I always very much enjoy the chance of doing a great piece of journalism.

Photo: Mysid. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Pay Attention

By Peter Mountford

Issue no. 223 (Winter 2017)

When she returns the following Tuesday, Bertram is watching CNN. There are two screens now: the one that’s right in front of his face and the television that’s been mounted on the wall all along. She sits and mutes the television. “You have more preloaded dialogue for me?”

Photo: Hana Kirana. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

How to Write

By Anne Waldman

Issue no. 45 (Winter 1968)

Perhaps I’m kidding myself about

the life I lead

Sometimes I feel I’m dying

like a lot of things I see around me

Then I turn on the TV and understand

that everything must still be moving

Music, for example, and I rush outside

around the corner to a concert

It’s so easy

Everything accessible from where I

happen to live at the moment …

And to read more from the Paris Review archives, make sure to subscribe! In addition to four print issues per year, you’ll also receive complete digital access to our sixty-seven years’ worth of archives. Or take advantage of our new subscription bundle, bringing you four issues of the print magazine, access to our full archive, and our new TriBeCa tote for only $69 (plus free shipping!).

On Jean Valentine

Jean Valentine (photo: Tyler Flynn Dorholt)

What I know about change, I’ve learned from the line break. Never ran this hard through the valley / never ate so many stars, Jean Valentine writes, daring you to guess what happens to her next. Like a Counting Crows promise replaying in my head, something child and vulnerable in me wants to believe “this year will be better than the last.” But quarantine—like a locksmith—copies my every day into sameness. It’s been a metronome of writing and work, in between video chats to Gambia with my nephews, first teeth sprout in the newest one’s mouth. I want to believe “I am changing” behind some curtain with the same control Jennifer Hudson calls up when she sings it, but as a poet, it’s more like I’m standing at the edge of someone else’s line break. I am changing—though, from this vantage point, I can’t yet see how.

I interviewed Valentine on December 19, 2013, for a now closed poetry journal where I was an editor. She was eighty-one and had invited me to her Morningside Heights apartment. Between us were fifty-two years and a plate of cookies she set on the table. I’d found her poetry my first year of grad school and each poem had planted in me something tender—inexplicably true—as a land mine that set itself off. And so, when news of her death broke through the world, it leaped. As though over the lacuna a line break creates.

Like so many, upon hearing, I thought of her seminal poem “Door in the Mountain,” and found myself, once again, at the mountain’s base. I was carrying a dead deer / tied to my neck and shoulders but had only, in the last few months, realized that that dead deer had named itself America. Deer legs hanging in front of me / heavy on my chest.

Over the course of three hours, Valentine told me Sylvia Plath had set her on fire. She said, “I think it’s hard on the people who are the firsts.” Like it was a promise she was giving me, “human nature can change. I have seen it change, I have.” And when I said sometimes your gods disappoint you, she nodded, “Sometimes your goddesses, too.”

There were five years when she didn’t write. She’d lost her publisher, her relationship. Her therapist had died. Then, her language came back. Once again, poems fashioned themselves from her dreams. “You are dreaming for humanity,” she told me of mine. What she wanted of poetry was “someone who is just going to go to the absolute end of their rope for this thing.”

She was a poet who could carve both stillness and speed from the gap and one who, for me, lit the match. She was the poet who first taught me to obsess over the responsibility of the line break and in her house, she held her shoulders like a woman no longer afraid to let it be known she liked to be amused. Whatever she and her line breaks had been through, she’d long ago found the courage to say.

People are not wanting /—“How much breath,” she asked me in her living room, “do you need to get where you want to go?”—to let me in.

For years of my adolescence, it was like the Counting Crows’ “Long December” was always on. I had a loneliness in me so big, yet so compact, it could have been shaped like a Jean Valentine poem. “Long December” was stagnation in a song. It was a song about time not changing, time being endless, and yet, in that space, so much still feeling possible. A song about living inside a seeming contradiction. Which, in poetry, is one of the mechanisms that makes the leaps of a good line break work. A great line break has music, can hold between it the melancholy of a teenager with the loneliness of a nineties lead singer and the improv of jazz. All you have to do is close your eyes and jump to know what I mean.

The best line breaks, like Jean Valentine’s, disrupt the connections you think are possible. It makes you trust yourself to the gap. Using everything you’ve ever known and forgotten, your mind and your imagination construct a bridge beneath you in real time. Suddenly, instead of “minding the gap,” you cross it. Studying her poems, I learned I could build a bridge between anything I loved—a poet, a song.

*

All those years ago in her living room, over tea and cookies—were they chocolate or were they gingersnaps?—Valentine told me of her difficult times and her uncertain ones. I didn’t recognize it then, but she was giving me the narrative arc of what change can be. It involved failure, chance, relationships—both romantic and platonic—a sense of humor, and sad songs you learn to cherish because even if in the passing decades they don’t hold up, they still have a way of keeping you standing. “Maybe I’m just untouched by embarrassment,” she’d said, smiling from behind a memory she’d learned to be gentle with. “I do look back and see foolishness. It doesn’t bother me too much. I think the main thing is to keep going.”

Change involves people you loved turning into glass, others into ghosts. No writing for five years. It means a break in the line you thought you’d been making. It’s writing the gap in order to cross it. Jean Valentine’s line breaks are the music, the dream, the ends between two points. The breaks trust us, make bridge-builders of us all.

Door in the mountain

let me in

“Door in the Mountain” is a poem of faith and change. We surrender to both. Every line break, a trust fall, and oh my god, the poet has caught you. Jean Valentine reminding us: waiting can be a form of change. In a crag, can be an entrance.

*

All over Brooklyn, tossed firs overwhelm the January air with Christmas’s carcasses. My father texts a painting he’s rendering from a photograph my wife took of the Grand Canyon. He purples ancient rock, Arizona sky—his brush showing us, day by day, what millennia do to color. These small moments are the beads I move across the abacus of our stand-still lives to promise myself time is passing. In my country that doesn’t play fair, I’m hoping the same predictable day waits for me behind America’s trapdoors. In a country that is always attacking Black people, COVID’s uncertainties are a reminder that the devil you know can become its own blessing.

From Valentine, I know it’s possible to grow weary, to be generous, and to laugh locked outside the mountain’s door. And if, in searching for a way in, I lose my words, I know from her that my words will take me back.

The final stanza of the poem is a leap through time, dimension, and possibility. The line break reminds me, though the door is not open—child, finally, you have found the mountain’s door. You see, people are not wanting to let you in. Change makes the mountain out of us. You think you can’t make it, and then suddenly there’s how far you’ve come.

Hafizah Geter is a Nigerian-American poet, writer, editor, and literary agent at Janklow & Nesbit. She is the author of the debut poetry collection Un-American from Wesleyan University Press, longlisted for the 2021 PEN Open Book Award. Hafizah’s poetry and prose have appeared in The New Yorker, Tin House, Boston Review, Longreads, and The Yale Review, among other publications. She lives in Brooklyn, New York.

January 11, 2021

Ways to Open a Door: An Interview with Destiny Birdsong

The spectacular present-day emergencies have inspired calls for art that responds to the moment, that speaks to the now, that lays claim to a particular kind of relevance. Emergency authorizes presentism, even as a virulent strain of presentism has everything to do with the emergencies we are facing. In this way, emergency casts the solution in terms of the logic of the problem, which guarantees the problem’s endurance; there is no out from this place. It feels, then, like a vital recalibration when I encounter Destiny Birdsong’s poem “Pandemic,” which is definitely not about COVID-19, and remember that language holds a history—and that history enters the present whether I recognize it or not. Throughout her debut poetry collection, Negotiations, from Tin House, Birdsong reminds you that if you offer deep attention—if you are precise and specific and careful—you will end up exactly where you need to be, which is to say: you will learn something about where you already are.

The poems in Negotiations attend to a series of concerns—sexual violence, autoimmune disease, anti-Blackness, artistic genealogies, the nourishments and injuries of kinship—but it would be more accurate to say that the poems in this collection expose the entanglements that have long existed, so that to name one site of encounter is necessarily to summon others. Birdsong’s poems reveal the ways that so many borders—nation, race, gender—are structured to maintain hierarchies of allegiance and care. In “400-Meter Heat,” which departs from the 2016 Olympic race where Bahamian sprinter Shaunae Miller-Uibo secured a narrow victory over American Allyson Felix, Birdsong writes: “I’m saddest whenever two black women are competing // because I never know who to root for, / and I’m arrogant enough to believe my split loyalty // fails them (which makes me more American again).” To notice is not only to reflect; it is also to register possibilities. The emergencies of the present are scored through with the fault lines of the past. Birdsong’s poems transform as they touch.

From our respective quarantines, Destiny Birdsong and I spoke over FaceTime about the complications of metaphor, embodied histories in language, and the possibility of curses.

INTERVIEWER

Negotiations has two epigraphs. Terrance Hayes, “What moves between us has always moved as metaphor,” and TJ Jarrett, “The worst has already happened to us, she said. / What good is metaphor now?” Would you say a bit about your relationship to metaphor in the context of this project?

BIRDSONG

I grew up in an environment where metaphor worked very strongly. Because there were certain things that people just didn’t talk about outright, metaphor became a way to sustain relationships that were complicated, or very tender. Also, people said horrible things to me because I had albinism. Those lines from Terrance Hayes really spoke to the way I grew up—afraid of language in a way that made metaphor a safe space. I read TJ Jarrett’s poem, “At the Repast,” a little later, at a moment in my life when that aversion to transparency just wasn’t working. I had to come to terms with things that had happened to me. I realized how dangerous it can be to refuse to say a thing. I had to call things what they were. In the poems, I’m always toggling back and forth between those two worlds.

INTERVIEWER

Do any significant metaphors of your childhood come to mind?

BIRDSONG

When I was four or five, I drew a picture of my imaginary friend, who looked suspiciously like me. My mom was so tickled. She showed it to everybody. When the adults looked at it, they knew that I was starting to see myself as visibly different from other people, but nobody ever said that. There was this kind of chuckle. It was understood. Maybe that’s different from metaphor, but it was part and parcel of the Black experience—these vocalizations, eye contact, little turns of phrase that, for the initiated, make things very clear. But if you’re outside, there’s a barrier between you and what’s being said. There was a lot of that happening. I’m not sure if that’s quite metaphor, but that’s what comes to mind.

I’m going to have to chew on that question for a bit because there was really a lot of silence.

INTERVIEWER

My friend who is a social worker uses poems in her practice because poems can hold traumatic experiences without coercing them into narrative. I’m thinking about a line from your essay for The Paris Review, “Be Good.” You write, citing Cathy Caruth, “And the truth is more than a combination of facts, of what we know happened. It’s also the lost experiences, ‘what remains unknown in our actions and our language.’ ” You have a Ph.D. in English, and have done critical writing as well as poetry. What does poetry as a genre offer for working with metaphor or silence?

BIRDSONG

I grew up in this family of silences, but in poems, I could say things under the aegis of poetry. When we think of poetry, we often think of heightened speech, ornamental language—a text whose beauty can allow things to happen in it. And maybe that’s what drew me to poetry. It still offers me the opportunity to make something beautiful, even out of things that are really ugly and disturbing.

I wrote “Be Good” years after I started writing about my sexual assault. I remember talking to one of my friends, who’s also a survivor, and she said, “Please don’t write a critical analysis about rape.” For me—and for some other people around me—it’s just not useful. In my experience, when you’re writing a critical analysis, there’s a certain performance of intelligence that has to happen, a performance of knowledge, a performance of complexity. But sometimes a thing is just a thing. It happened, and it was bad. I needed to get to that truth through poetry before I could write about how respectability politics and class and gendered norms in the Black community influenced that experience.

INTERVIEWER

A lot of the poems deal with being read and misread, reading and misreading. You also have a robust notes section that builds a kind of bibliography into the book. How do you feel about your own work being read?

BIRDSONG

I rarely think about that when I’m drafting because if I did, I probably wouldn’t write things. I am excited about the book. I got my M.F.A. in 2009, and I left my M.F.A. program thinking, I’m going to have a book in a year. Every one of my professors said, “Your thesis is not a book.” And it wasn’t. But that desire for a book has been a long time in coming. And that desire has changed over time. At first it was a desire for validation—I really am a writer. This thing I’ve been telling my family members about is now something they can pick up and hold. Now, I’m most excited about entering what has always been, for me, a rich conversation. Even in high school when my only real access to poetry was my high school textbooks, and I was memorizing John Donne and Shakespeare, it felt like a place where people were talking to me in ways I could relate to. It feels wonderful to enter that conversation in a tangible way.

As for the notes section, that’s the academic in me. Cite your sources. I also wanted to make clear that these poems are products of bodies of knowledge. As much as they are in conversation with capital-P Poetry, they’re in conversation with music and scripture and historical events that happened during my lifetime.

INTERVIEWER

The way you’re talking about bodies of knowledge brings me to “Ode to My Body.” In that poem, the body is a subject distinct from the I. But even as there’s this cleaving, there’s a different form of entanglement with Lucille Clifton’s “the lost baby poem,” which your poem riffs on. In other words, as the poem distances from one kind of body in order to see it differently, it joins with a different kind—a body of poetry, a body of Black women’s literature. What came into view for you as you enacted these shifts on the page?

BIRDSONG