The Paris Review's Blog, page 124

February 18, 2021

Corona Porn

In the early stages of quarantine, a lot of people ordered War and Peace. I hesitated. I am not a doctor, or a delivery person, or a health care worker, I thought. I have no god’s-eye view on the real suffering taking place. In the end I reached for Jean Genet’s Our Lady of the Flowers, a lurid masturbation epic first drafted in prison on brown paper bags. Because while a lot of us, in these uncertain times, could use some Tolstoyan omniscience, even more of us could use some sex.

Don’t be shy, don’t be ashamed! Reminder that when Shakespeare was quarantined, he definitely masturbated. As with romance and God, so has mankind been motivated to aesthetic heights by “trafficking in thyself.” Settling in to a ten-year sentence, Genet’s narrator proclaims, “It was a good thing I raised egoistic masturbation to the dignity of a cult! … Everything within me turns worshiper.” There are lots of books about diddling yourself—and I for one have always thought of writing as a way of granting permission. The inexperienced might seek comfort and instruction in Portnoy’s Complaint, where Alexander makes love to a stolen apple in the woods (“‘Oh shove it in me, Big Boy,’ cried the cored apple that I banged silly on that picnic”). In Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God, Janie debuts an orgasm under a pear tree in spring: “She saw a dust-bearing bee sink into the sanctum of a bloom; the thousand sister-calyxes arch to meet the love embrace and the ecstatic shiver of the tree from root to tiniest branch creaming in every blossom and frothing with delight.” The Nausicaa episode in Joyce’s Ulysses is set to the backdrop of festival fireworks and a glimpse of a woman’s underthings (“awfully pretty stitchery”), at whose unveiling Bloom, stationed in a church across the way, can hardly believe his luck: “And then a rocket sprang and bang shot blind and O! then the Roman candle burst and it was like a sigh of O! and everyone cried O! O! in raptures.” After the climax, the disappointment, the shame: “O Lord, that little limping devil. Begins to feel cold and clammy. Aftereffect not pleasant.”

*

Most days, under lockdown, before I sit down to a task I’d rather not, I take half an hour to—you think I’m about to say something else—procrastinate. I scroll through dispatches from anxious people bleating out reports from their private homes: someone has shaved her head; someone has macerated a rare root vegetable into a time-consuming compote. “Got in a lot of good crying today,” someone else says, or maybe brags. There’s a whole genre of these broad-strokes allusions to the times we’re in, i.e., a pandemic, now cresting its second climax. I put on a sweater and meet with a student over Zoom, direct the task light into my face so that my acne will not show. (I learned cinematography; you learned to make sourdough.) Afternoons are given over to further internet pastimes. For example, perusing salacious, Georgian-era pamphlets of puritanical intention (whose executive summary could be: cease and desist from masturbation), which is how I came across this gem: Onania, or, the heinous sin of self-pollution and all its frightful consequences (in both sexes), Considered, with spiritual and physical advice to those who have already injected themselves by the abominable Practice. If only we’d been so severe in phrasing our early warnings about social distancing.

Both social media and masturbation announce themselves as potent distractions. Perhaps it’s no surprise, then, that much of our hand-wringing over social media mirrors the Puritans’ critiques of self-pollution. That there is something masturbatory about idle online existence is in the language of the trade. Even in the prepandemic age, we trafficked in “food porn” and “book porn” and “film porn” and “apartment porn,” photographed our lunches, our brunches, drinks enjoyed in crowded bars. As much as it exists for sharing memories and experiences, Instagram has always moonlighted as a kind of pimp.

Moralists cite unproductiveness, perversion. Masturbation, they say, redirects a fundamentally social impulse toward oneself. In the story of Onan, from the Book of Genesis, and to which Onania pays homage, Onan is slain by God for refusing to impregnate his widowed sister-in-law. The point is that sex is a social obligation, masturbation is a waste (and that if God orders you to fuck your family, you should probably obey). Even Shakespeare, in his Procreation Sonnets, hinted at warnings: “Unthrifty loveliness, why dost thou spend / Upon thyself thy beauty’s legacy?” These so-called hazards, namely prodigality, of solo sex would suggest we are creatures of limited secretion, limited lust. Based on anecdotal evidence, I’d say this is a low-risk eventuality.

Those same charges of perverting sociability and impeding productivity are also commonly upheld against the way we communicate online. Even the non-Luddites refer to our internet habits as masturbatory because we suspect they do corrupt a social impulse, that these mediated norms have a sly way of diverting the impulse to engage with others into a focus on oneself. It makes you wonder about the potential risks of transacting, in a moment of crisis, in the currency of private banalities on platforms that, while keeping us informed, also tempt us into exhibitionism. At the same time, it’s hard to be alone. Right now, there isn’t really any other way to be. We all exist online.

*

Social media and masturbation, whatever else they may be, are basically creative ways of overcoming formal constraints. Masturbation is an expression of desire—either for pleasure or to procreate—convenient to situations where other modes of climax are prohibited (for example, in a pandemic, before your test results come back). Social media, for its part, is the mediated expression of a variety of communicative impulses, among them the desire to be heard by distant strangers. It tends to be populated by a kind of ephemeral speech—the exclamation, the insult, the quip (what is the GIF but a repackaged guffaw?)—made possible by intense proximity; it is the triumph of immediacy over distances and barriers that would otherwise be prohibitive. The difference, of course, between masturbation and social media is that the former (often) has no audience, while the latter has nothing but.

The audience of social media is mercurial, particular. As with most banalities and small talk, any given post isn’t guaranteed an audience, let alone a response. In one sense, when you post online, no one’s listening at all. As a wise friend said when I raised the idea with him, “Forsooth, you’re talking to yourself.” But you’re talking to yourself in public, the way you might on the street, garnering various levels of attention depending on what you say and how you say it. In fact, the very idea of being “in public” or “on the street,” and your subject-position to that environment, influences what you say. The real content of social media is maybe more like soliloquy roulette: the theater is empty, but there’s always the chance that someone might drop by. And it’s this potential for an audience—the implied level of performance—that changes both the speech and our perception of it. Take, for example, the aforementioned hypothetical: “Got in a lot of good crying today.”

It can be critically important to share private moments in a crisis, and to consume them, too (I do). For comfort, for company, for bearing witness. It keeps us in touch, keeps information flowing, provides a forum, cultivates a sense of company; when people share anxieties and fears and stories, others are granted permission to feel or do the same. There are COVID-19 patients, extremely ill and distressed, who have no other form of communication with their loved ones other than through a screen. There are quarantined millions whose social lives are limited to the same. The only way to have sex with someone new right now is to swipe right on Bumble or Tinder. There have been campaigns to bail out prisoners, restaurant workers, cinema workers, domestic workers, to provide depleted hospitals with PPE, all conducted online. Weddings take place in the city hall of Zoom, or at least that’s how mine was held. These platforms are the life support hooked up to real life, and yet, alas, they are no substitution, inferior to the real thing. The true tragedy of COVID-19 is not only that so many are dead, but that so many are dying in isolation, without the physical presence of someone else—of touch—to comfort them.

It is also nice, however, if you are healthy, if you are waiting, to remember how to be alone. To be a body trapped inside. To recall that keeping yourself to yourself can actually protect someone else. And that there are some experiences you might hesitate to share online, even as it becomes more and more synonymous with IRL. Not because the anecdotes themselves (“I masturbated”; “I ate canned soup”; “I shucked some corn”) are untoward, but because one can sense that the medium changes them somehow, in ways beyond our control. This brings us, unhappily, to Marshall McLuhan’s doorstep: “The medium is the message.”

There is a reason so much of social media content is consumed aspirationally, as “porn.” But the difference between actual porn and “porn” is that the kind you masturbate to is exciting precisely because it’s illicit, while social media porn—real life, fully waxed—is perfectly appropriate to consume and produce in public. This libertinism certainly seems something like progress, if only because the authors of Onania wouldn’t like it; as a general rule of thumb, one is inclined to support those things white males of Georgian-era Britain wouldn’t. Masturbation is a public health boon in the middle of a pandemic. But what, if any, are the risks of exhibitionism?

By way of analogy, McLuhan suggested that in representing every perspective simultaneously, Cubism nullifies both the content and the idea of perspective; the most lasting impression of the Cubist painting is Cubism itself, not, as the title would suggest, “Fruit Dish” or “Girl with a Mandolin.” The most lasting effect of social media, in a similar sense, may be a configured confessionalism. The bigger the crowd, the more perspectives represented simultaneously, the more defined the experience is by the panorama of the aggregate; the more likely the form is to overwhelm the content. We’re no longer seeing the fruit bouquet, Prime-delivered for Valentine’s Day, that someone lovingly arranged and posted. We’re seeing the mosaic of Instagram itself.

All this speed, all this simultaneity, invites a kind of redundancy and self-referentiality. Though a post may originate with a desire to say something about the world, it just as often winds up referencing the metahumor and metasuffering of the platform itself. The impulse to react to the real world is therefore rerouted back onto the virtual. The shimmer this creates is an alloy of both solipsism and solidarity, the fusion of the first person and the omniscient; a novel written by Genet and Tolstoy at once (yikes). Aftereffects potentially not pleasant. Because out there nurses are hooking suffocating people up to ventilators, and you’re just at home, you know…

Why not?! The state of the world has always been incompatible with private joy: reading novels, masturbating, eating fruit compote. “Integrity is the orgasm,” Doris Lessing writes in The Golden Notebook. Although it’s true, it’s invoked in a melancholic scene, one in which a woman is wondering if she can ever achieve a vaginal O with someone she doesn’t love, and who is not herself. Take English, August instead, the great Indian, post-Independence, civil service, quasi-Shakespearean, masturbation picaresque. Agastya, an elite Kolkata native, passes long hours beneath his malfunctioning ceiling fan in a rural village’s stifling heat, watching the lizards scurry up the wall while he exalts in himself. True, afterward, he’s quite depressed. Come to think of it, it’s really a book of boredom and existential ennui and placelessness. Our Lady of the Flowers, I’m reminded, charges forward toward a death sentence. It should be safe to retreat to the seventies best seller The Joy of Sex: A Gourmet Guide to Lovemaking. Joy is right there in the title! Though I see here the authors have euphemized a hand job, unappealingly, as a “corpse-reviver.” Limping little devils. Petit malle, say the French. Not integrity, but little death. A fleeting escape from processing, emotionally or intellectually, the world in which you’re trapped.

*

Coronavirus is the most significant disruption to American life since 9/11, yadda yadda, we know, but it’s also the first, unelected national disaster that Americans have responded to and processed primarily online, and in particular on social media, as opposed to in print or on TV. That is to say, through a medium where genres of content—the kitchen, the brunch, the pandemic—are each awarded their own niche “porn.” And if porn hinges on a kind of fantasy, consumed aspirationally, then is it possible to make a pornographic production of a disease-free world? Social media’s newest genre of idle excitement may be “corona porn.”

Good porn realizes fantasy while eliding its consequences. Anne Boyer, in her unsentimental memoir, The Undying, about surviving stage-three breast cancer, writes of the “patho-pornography” of breast cancer awareness campaigns and their unintentional harm. The nation’s pink-ribbon porn, she argues, supports the myth that breast cancer is curable, as well as the neoliberal idea that survival hinges on an individual patient’s attitude. Every October, the world becomes “blood pink with respectability politics,” and in all the hopeful messaging it is “as if anyone who dies from breast cancer has died of a bad attitude or eating a sausage or not trusting the word of a junior oncologist.” The suggestion is that the symbols of performative solidarity—derived from an outpouring of emotions by the healthy on behalf of the sick—can have an uncomfortable way of imposing fantasy and false hope on ugliness. Not to mention, Boyer points out, glossing the class and racial politics that fracture diagnoses, outcomes, and treatments. In the book, she recalls expressing these frustrations and fears with other women and survivors through support groups on Facebook and like outlets, online communities that in many ways became a crucial link to sanity. Those digital survivor networks are thanked in the acknowledgments.

The state of affairs, in the aggregate, is that everyone has been sick, or else knows someone who has; that everyone has a lost a job, or else knows someone who has been laid off; that too many have lost or nearly lost a loved one to COVID-19; that the brunt of physical and economic morbidity has fallen along expected racial lines; that inequality has been further exacerbated, and violent hate crimes are on the rise. I can glean all of this from newspapers just as well as from my feeds. But filtering the pandemic through a medium that tends to emphasize the primacy of personal experience risks, on the level of the whole mosaic, mapping onto a political stance that does the same: what is owed to me, versus what is owed to us. Last April, a friend of mine, a doctor who faced some of the highest rates of COVID-19 exposure in the nation, took to miming jacking off every time the hospital congratulated his team or provided them with gratis cupcakes. I think what he meant, in part, and in his frustration, is that no matter how much we praise or honor those at the center of the pandemic, the fact remains: something is unfolding that is profoundly, deeply unfair.

We don’t cheer for essential workers in the evenings anymore, bang pots and pans at 7 P.M. (though there was that brief revival for a lackluster Biden win). What tepid winds of change 2021 promises! I liked leaning out my windows and into my street, in April, to clap along with neighbors, each of us peering from our little portals onto a shut-down world. It made me feel something. It made it seem like something, someday, had to give. It was necessary and important. We could not have skipped it. All the same, I wouldn’t totally disagree with my overworked friend’s medical opinion that we on the sidelines might as well be masturbating. Afterward, clammy, you’ll likely feel worse. But you may forget, briefly, in that “little death,” about our collapsing world, and the best part is, no one has to know. You can keep it all, the pleasure and the forgetting and the shame, to yourself.

Jessi Jezewska Stevens is the author of The Exhibition of Persephone Q. Her next novel, The Visitors, is forthcoming from And Other Stories in 2022.

February 17, 2021

The Power of the Kamoinge Workshop

In 1963, with the civil rights movement in full swing, a group of New York City–based Black photographers began meeting regularly to talk shop, listen to jazz, discuss politics, critique one another’s work, and bond over the power of their shared medium. Thus, the Kamoinge Workshop was born, a collective whose members pursued wildly varying aesthetic interests but held a mutual commitment to photography’s value as art. “Working Together,” an exhibition featuring work by fourteen key members of the Kamoinge Workshop, will be on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art through March 28. A selection of images from the show appears below.

Anthony Barboza, Kamoinge Members, 1973, gelatin silver print, 9 3/4 x 10″. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase with funds from the Jack E. Chachkes Endowed Purchase Fund 2020.55. © Anthony Barboza.

Adger Cowans, Footsteps, 1960, gelatin silver print, 8 1/4 × 13 1/4″. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Aldine S. Hartman Endowment Fund, 2018.201. © Adger Cowans.

Ming Smith, America seen through Stars and Stripes, New York City, New York, printed ca. 1976, gelatin silver print, 15 3/4 × 20″. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Adolph D. and Wilkins C. Williams Fund, 2016.241. © Ming Smith.

James “Jimmie” Mannas, No Way Out, Harlem, NYC, 1964, gelatin silver print, mount: 15 1/8 × 11″. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Arthur and Margaret Glasgow Endowment, 2019.201. © Jimmie Mannas.

Shawn Walker, Easter Sunday, Harlem (125th Street), 1972, gelatin silver print: sheet, 7 3/4 × 9 3/4″. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase with funds from the Photography Committee, the Jack E. Chachkes Endowed Purchase Fund, and the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation 2020.61. © Shawn Walker.

Albert Fennar, Salt Pile, 1971, gelatin silver print, 6 1/2 x 6 1/2″. Collection of Shawn Walker. © Miya Fennar and The Albert R. Fennar Archive.

Beuford Smith, Two Bass Hit, Lower East Side, 1972, gelatin silver print, sheet: 11 × 14″. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Arthur and Margaret Glasgow Endowment, 2017.36. © Beuford Smith/Césaire.

“Working Together: The Photographers of the Kamoinge Workshop” will be on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art through March 28.

Sliding into Patricia Lockwood’s DMs

If navigating the internet were an Olympic sport, Patricia Lockwood would sweep the medals. She is not a coder or a programmer (though surely she could be). She doesn’t live in the internet but upon it. She sails along on trends and tweets, a fisher of men, understanding, as she writes, that “everyday their attention must turn, like the shine on a school of fish, all at once.” As the tides shift, she is always one twist ahead of the internet’s dangers, such as overexposure and cancellation. We here at The Paris Review are often made aware of her one important question we have yet to answer:

Lockwood is not only the quiet queen of twitter, she is also a poet, memoirist, sublime critic, and her first novel is on sale this week. I spoke to Patricia Lockwood about her “internet novel” No One is Talking About This over direct message on Twitter, which was something like interviewing Scorsese on the set of Gangs of New York, or something like Scorsese interviewing Fran Lebowitz in front of the World’s Fair Panorama of New York. Unlike Lockwood, the internet overwhelms me. It always has. Lockwood caught COVID-19 in early 2020 and is still suffering from nerve-related difficulty with her hands. She had to ask me to slow my typing because my blank terror at awaiting a response on any messenger app, a form of communication detached from facial expression, intonation, and occasionally context, sends me into a frenzy.

I was embarrassed but not surprised to betray myself. Lockwood knows how to cast an astral projection on the Web, while most of us (read: this interviewer) are still tapping the bloated backside of a desktop PC trying to find our way “inside the computer.” Lockwood’s novel is about a woman who navigates the internet with such perfect ease that she becomes an Internet-ese celebrity expert asked to speak about the internet to audiences around the world, what it is and what it means. The protagonist of No One is Talking About This describes the feeling that the internet “was a place where she knew what was going to happen, it was a place where she would always choose the right side, where failure was in history and not herself, where she did not read the wrong writers, was not seized with surges of enthusiasm for the wrong leaders, did not eat the wrong animals, cheer at bullfights, call little kids Pussy as a nickname, believe in fairies or mediums or spirit photography, blood purity or manifest destiny or night air, did not lobotomize her daughters or send her sons to war, where she was not subject to the swells and currents and storms of the mind of the time—which could not be escaped except through genius, and even then you probably beat your wife, abandoned your children, pinched the rumps of your maids, had maids at all. She had seen the century spin to its conclusion and she knew how it all turned out.”

The first part of the novel is told from so deep within the internet that it is almost vertiginous, but Lockwood never loses control. Then, the protagonist steps out of her element and into the real-life concerns of her family. Lockwood’s novel is in two distinct parts: there is the era before her niece’s genetic condition becomes clear, and the after.

I slid into Lockwood’s DMs to ask her about the novel, her screen names of yore, the Zoom cat, and I snuck the conversation back, once or twice, to the terra firma of her astute literary criticism, which seems to be a third language in which Lockwood is fluent.

@juliaberick:

Hello, Patricia! Thank you for agreeing to an interview by DM. I felt it would add a note of authenticity to this interview if we scheduled it for 2 A.M., but quarantine is strange enough.

@TricaLockwood:

Hi Julia! Let’s do this little old thing

DM hogs, in the chat

@juliaberick:

Can I start by asking what the last DM you got was before this one? I’m interested in what it’s like to be very online and have open DMs.

@TricaLockwood:

Looks like it was a red heart on a koala picture I sent to John Darnielle.

@juliaberick:

Does one receive bundles of dick pics? Cornucopias of dick pics?

@TricaLockwood:

Yeah, I’m not sure why I left them open. I have always been more inclined to openness; I like to hear about things. Occasionally people will DM to say thank you for a poem I wrote, or that they named their cat after Miette—I would miss those things if I were locked down.

I don’t get all that many dicks, really. A few textual wangs, here and there. But Twitter also hides “suspicious content,” so I don’t click on pics if there’s a warning.

@juliaberick:

Thanks, Twitter.

You met your husband online—is that right? Does that change your idea of “strangers on the internet” do you think?

Like maybe the masses are actually friends waiting to be made, husbands waiting to be wed, instead of just faceless analytics?

@TricaLockwood:

Maybe. Or maybe I met my husband online because of this quality, because my mind was ALREADY so open that anything could fall in. Including—my god—a Man.

@juliaberick:

HA

There are theories that online dating is changing the gene pool, because people can self-select more readily for partners, and that this is especially true for those who might have been too shy to meet folks irl—though perhaps your story with your husband disproves them. I just think about how the internet is changing the way we mate.

@TriciaLockwood:

I don’t know about that—our case might actually support those theories. Because we never had kids! No chance to SMell EAch OTher beforehand.

@JuliaBerick:

HA

Okay good point

Did you keep any of your early conversations?

@TriciaLockwood:

Sorry, can you see my typing ellipses? I’m probably typing too slow but I’m having problems with my hands.

I didn’t actually—all those love letters lost like gorillas in the mist. They’re locked up somewhere in a Hotmail account, I think. If you want to keep something safe on this earth, put it in an old Hotmail account.

@JuliaBerick:

Sorry ‘bout your hands. I can see the ellipses! I’ll slow down. I learned my typing speed from trying to capture the heart of a 14 yo boy on the AIM and I’ve never recovered composure.

It’s not great now that I Slack my colleagues all the time.

Someone with the right skills and the right pleather can probably liberate those love letters for you at some point…

@TriciaLockwood:

Spandex, probably. It’s a privilege, not a right.

Did you ever capture the boy on AIM?

@JuliaBerick:

Not at all

@TriciaLockwood:

Hahahahaha

@JuliaBerick:

I must have put up the wrong away message after all

Can you remember one of your early screen names?

@TriciaLockwood:

Oh yeah I’ve got a great one. fruitandcake.

Does this ring any bells?

@JuliaBerick:

Hahaha

@TriciaLockwood:

THE FIG NEWTON TAGLINE. MY BRAND WAS INTACT FROM AN EARLY AGE.

@JuliaBerick:

That is truly impressive

The entire time I was reading the novel, I pictured you like the oracle of Delphi.

@TriciaLockwood:

A CARYATID WITH WHITE EYES—sorry caps lock was still on

My toga pouring like a fountain

Oracles is also a very “online word,” though I don’t know how many remember that

The training program for oracles is the same as it is for vestal virgins, except they switch out the snatch and the eyes. In my opinion.

@JuliaBerick:

HA

I had a friend who asked everyone he met for a year, “would you rather do ___ celebrity with a snatch in the middle of her stomach or with three eyes?”

This seems relevant

But okay a real-ish q

I’ve read that you revised the first section of the novel, in the first months of the pandemic, to add in things that had happened since you began writing. What didn’t make it into the novel that you wish had. The cat lawyer? The QAnon Shaman?

Can you even believe the cat lawyer?

@TriciaLockwood:

AH, I actually tweeted this one. It’s the Perfect Dinosaur Butthole. That should have made it.

@Juliaberick:

They changed something in the matrix

@TriciaLockwood:

Exactly. You can smell some uncanny difference. Berenstain Bears.

@Juliaberick:

I think that if we were meeting in person, I would have said 25 minutes ago that I cannot believe how brilliant the novel is, except that I can, because your work is fabulously, uncannily exquisite

@TriciaLockwood:

Thank you! Yes, all these interviews would be so changed if we were able to do them in person. There’s been a sense of grief throughout the process, in fact, and I think that’s the reason.

@Juliaberick:

Your recent review in LRB of Ferrante’s The Lying Life of Adults also basically wiped out my brain and replaced it—it was so newly correct. It also made want to think about your novel differently

About how both Twitter and (forgive me) autofiction make the writer the HERO. The manipulator.

Do you think that is true at all? Does Twitter change Lenu’s into Lila’s?

@TriciaLockwood:

I loved doing that review—I felt limerent the whole time I was working on it. It’s been my constant companion ever since the election, up through the Georgia runoffs, up through the insurrection. The entire time I was doing my promotional push, it’s all I was thinking about. I was like, stop asking me all these questions! I’m considering the problem of Alfonso!

No, a Lenu can’t be changed into a Lila. It’s a leopard/spot situation.

But also Lila identified Lenu as *someone like her,* which is easy to forget. She takes her by the hand because there IS some likeness, some ruthlessness that she identified—the ruthlessness that will eventually write the story.

That’s why one critical approach to them considers them as parts of each other. This is not quite right, I think. Lila identifies something animal in Lenu, some scent that is like hers.

@Juliaberick:

Even if what is animal in Lenu is only her desire to be like Lila

Hmm

@TriciaLockwood:

One temptation with a book like this, the book I wrote, is to make the protagonist both right and good. To position her on the correct side of every issue.

To go back and revise in the light of further information, to elevate her. Lenu talks in one of her bookstore Q&As about how we must not become “policemen of ourselves,” while at the same time tailoring everything she says to some standard of Nino’s. Nino, that little fuck! Twitter is certainly a place where this can happen—where we issue proscriptions while at the same time tailoring our speech to different audiences within the stream.

Sorry that was all a mouthful. God knows I took approximately One Thousand Pages of notes on all these themes.

@Juliaberick:

I think one interesting thing about your protagonist is that she is aware of how useful it is to be nimble, to move more quickly than the morality of the internet. She exists above all the morass of offending and being offended. There is also her canny sense of how to bring her internet skills to the real world. When she sees a geneticist who is conspicuously excited by how rare the baby’s condition is, instead of being pained, she thinks, “Messy bench who loves drama.” It’s a quick phrase that puts the doctor in a place where she can do no real harm. In some ways she is absolutely without moral standing, maybe because she stands so centered in the slipstream.

@TriciaLockwood:

Yes, her soul is not a moral soul, it is an attentive one, a white beam of observation. But nimbleness within the portal is also ruthlessness. It is what keeps you ahead, what keeps you out of other people’s teeth. Yet in the second half of the book the protagonist is surely thinking, to what end? What did I believe was chasing me before?

Why was I practicing this agility, what was I adapting to? Has it given me the muscles for what I’m now experiencing? Has it given me the language, the ability to listen, the cry? Does it allow me now to lift and carry a human life? To some extent she finds that it did, that whatever lives we lead they do prepare us for these moments.

@Juliaberick:

In that way, the novel really sadly/eerily presages the pandemic: a stark medical reality has pulled a lot of people out from their less conscious routines. Did you see people around you asking themselves those questions this year? Recognize it?

@TriciaLockwood:

I did. I think that’s true, though I also think the internet been a crucial way for people to connect this year. At times we’re all biting each other like the Donner Party, but it still has been crucial.

But for me, I got COVID in March, and that threw me out of the portal in another way—I had a lot of neurological symptoms, and I developed Howard Hughes–level nerve pain in my hands. So first I couldn’t really read and understand what was happening online, from spring all the way through fall. And then I couldn’t use my trusty finger, my little ET pointer, to scroll in the same way.

@Juliaberick:

I sincerely hope you are feeling better. My partner hid the fact that you had COVID from me until we started to feel better from our own. He knew I would have been very worried for that ET pointer.

@TriciaLockwood:

Hahahahaha

@Juliaberick:

We had like a nothing case

We just ate ramen and groaned at each other

But for a minute there I was sure it was the end

@TriciaLockwood:

Yeah, did your body Prepare to Die? Everyone I’ve talked to, even people who had mild cases, experienced a moment where their Bodies Prepared to Die.

@Juliaberick:

I prepared to defend my sanity.

My gentleman was like:

But are you sure its COVID? (I’m a rampant hypochondriac.)

And it was an ENORMOUS moment of intellectual crisis, because I was like, can I really be crazy enough to be making this up?

And then he got it too and I had only enough energy to say “see” and then moan like we were the Ingallses in the part of Little House on the Prairie where they all get diphtheria

@TriciaLockwood:

My husband and I both experienced that too and we really were on death’s door, down on all fours and crawling from room to room. I think it’s because at that point you just couldn’t get tested, and doctors really did treat you as if it was an INCREDIBLY REMOTE POSSIBILITY that you might have it. Which is insane—at that point thousands of people a day were dying in NYC!

@Juliaberick:

We were in NYC

And my doctor was saying don’t get tested, the ER is a battlefield from which you will never return

@TriciaLockwood:

Right. Like we really didn’t feel we could go to the hospital.

@Juliaberick:

I guess I did prepare to die

Now that you mention it

I had blocked it out

@TriciaLockwood:

Perhaps because the body was encountering something absolutely new, for the first time in a long time. I found it interesting later.

@Juliaberick:

I’m finding it interesting now. It is the total surrender everyone is always talking about. While you were sick, did you have religious feelings you thought you had lost track of?

(I was going to have my final question be about something else. But COVID just fills the brain.)

@TriciaLockwood:

No, nothing of the kind actually. But I felt returned to my childhood in the most visceral possible way. My dreams were hyperreal and populated with my oldest friends and most ancient episodes. I actually recovered memories, as if some path in the brain had been set on fire.

In a way it was DOPE AS HELL.

@Juliaberick:

I know what you mean. I don’t want to keep you past an hour. Please carry on promoting this masterpiece and lighting my brain on fire from the spires of the LRB.

And… I’m sorry that we at The Paris Review have kept you waiting on that review of Paris.

@TriciaLockwood:

NO, I never want to know!

Julia Berick is a writer who lives in New York. She works at The Paris Review.

February 16, 2021

Redux: Drowning in the Word

Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

Simone de Beauvoir.

This week at The Paris Review, we’re celebrating Valentine’s Day and dwelling on both the highs and lows of love. Read on for Simone de Beauvoir’s Art of Fiction interview, Akhil Sharma’s short story “The Well,” Frank O’Hara’s poem “Love,” and Eric Fischl’s portfolio “Couples.”

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, and poems, why not subscribe to The Paris Review? Or take advantage of our current subscription offer, featuring our stylish new notebook—the perfect place to draft love poems, write your novel, or log your reading list. (And you can always just buy the notebook, too!)

Simone de Beauvoir, The Art of Fiction No. 35

Issue no. 34 (Spring–Summer 1965)

INTERVIEWER

None of your female characters are immune from love. You like the romantic element.

DE BEAUVOIR

Love is a great privilege. Real love, which is very rare, enriches the lives of the men and women who experience it.

INTERVIEWER

In your novels, it seems to be the women—I’m thinking of Françoise in She Came to Stay and Anne in The Mandarins—who experience it most.

DE BEAUVOIR

The reason is that, despite everything, women give more of themselves in love because most of them don’t have much else to absorb them. Perhaps they’re also more capable of deep sympathy, which is the basis of love. Perhaps it’s also because I can project myself more easily into women than into men. My female characters are much richer than my male characters.

Photo: Armstrong Nurseries. Courtesy of the Henry G. Gilbert Nursery and Seed Trade Catalog Collection. No restrictions, via Wikimedia Commons.

The Well

By Akhil Sharma

Issue no. 218 (Fall 2016)

As I told her I loved her, I felt, as I often did with Betsy, that what I was saying was a lie, a melodrama, a way to capture her, that things would not work out, that I was being foolish, that I was acting as if I didn’t understand the reality of the situation, except that I did and was willing to break things and make things very bad just so I could get her.

Tears slid down her cheeks.

“Why are you this way?” she asked.

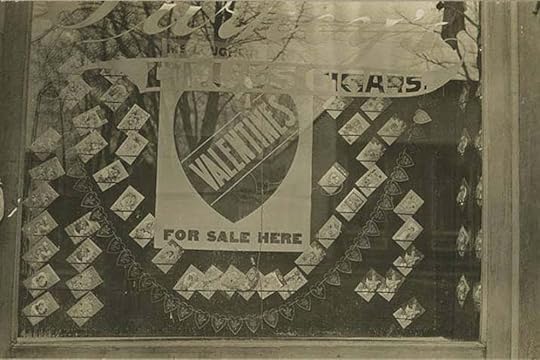

Photo courtesy of the John I. Monroe Collection, via Wikimedia Commons.

Love

By Frank O’Hara

Issue no. 49 (Summer 1970)

A whispering far away

heard by the poet in a bower

of flesh his limbs stir

is it sadness or the perfection

of eyes that clutches him?

And a parade of lamenting

draws near a wave of angels

he is drowning in the word

Art: Eric Fischl.

Couples

By Eric Fischl

Issue no. 86 (Winter 1982)

If you enjoyed the above, don’t forget to subscribe! In addition to four print issues per year, you’ll also receive complete digital access to our sixty-seven years’ worth of archives . Or take advantage of our current subscription offer, featuring our stylish new notebook—the perfect place to draft love poems, write your novel, or log your reading list. (And you can always just buy the notebook, too!)

Searching for Gwendolyn Brooks

Gwendolyn Brooks at her typewriter.

Often, when I look back at the poems that have found their sudden ways to me—the ones that have chosen me in particular, to move through me and onto the page—it is hard to imagine they are related to one another. It is hard to believe the poems that sprawl wide, the poems that play their tricks, the poems that exhume and resurrect, that breathe strange and speak with different tongues, all share a common denominator. It is hard to believe all the differently hued poems I’ve written have come from my own throat, born of the same place but perhaps of a different season, fruit of the same tree perched on a different branch.

How is one of my poems that sounds like “How Great,” by Chance the Rapper—a song that I love—related to another poem that I would not have written without reading Eve Ewing’s Electric Arches? How is a poem I wrote about my late father’s gold chain related to a poem I only fairly recently discovered?

This is the natural order of being descended from one common lineage, so much of the work I love the poetic offshoot of one common ancestor. Those that have taught me my best lessons have all learned from Gwendolyn Brooks, or have learned from someone who had learned from Brooks. Today, if I squint hard enough, if I ask the right questions, it seems everything—the poems, the music, the seasons—points me back to her.

*

My poetic lineage is constructed, as I see it, via the long list of all the poems, visions, music, stories, and every syllable of any bit of good language that I’ve encountered in my life. What becomes cardinal in that lineage is the bits that manage to sear my inner skull with their light and bring me new ways of seeing.

One entry point into my lineage can be found in the poetry of Ross Gay, and more specifically, his poem, “,” and, even more specific still, his line, “My color’s green. I’m Spring.”

I was first assigned Ross Gay’s Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude while in an undergrad workshop, and I consumed it so quickly I made small gusts of wind as I turned the pages. Gay’s ability to wield the hues of joy made me hunger. His poems taught me how I myself might enter language through the wide threshold of rapture.

Gay is known to enter delight through many different doors, but in “Sorrow Is Not My Name,” Gay decided the door would be death itself. Death and the many tools it has sharpened and dipped into fire. Death and its claws tapping through the frost on our bedroom windows. I have been in close proximity to the reaper and his wide blade, and so it feels familiar to watch Gay’s speaker name death as it appears throughout the landscape:

just this morning a vulture

nodded his red, grizzled head at me

He names it again as he finds death even closer:

the skeleton in the mirror, the man behind me

on the bus taking notes

And yet, there is delight. There is a sense that Gay’s speaker will surely perish eventually, maybe even soon, but certainly not today, not in this particular poem. Today, Gay’s speaker feels only delight rupturing through his body.

…yeah, yeah.

But look; my niece is running through a field

calling my name.

The speaker remembers, almost like a prayer, that their name is not endued with sorrow. And thus, the poem ends with a line that has clogged the cogs of my thinking; clogged them with glee:

I remember. My color’s green. I’m spring.

*

At the top of the poem, right under its title, Ross Gay attached the words “after Gwendolyn Brooks,” after serving as a dangling thread to be followed. I put great effort into finding the Gwendolyn Brooks poem that inspired Gay. I wanted to trace the impetus that made Gay write such a splendid thing, that made him feel so alive that he saw himself akin to an entire color, an entire season.

I googled, I asked friends, I skimmed as many poems by Brooks that I could find online and searched every book of hers I could get my hands on. I had little luck. All my friends knew of the Ross Gay poem but knew nothing of Brooks’s influence. I decided, ultimately, that it was enough to just adore Gay’s work, to read it over and over again in my head, to study its nuts and bolts. At the time, I didn’t yet have the gall to reach out to him directly, but I thought maybe someday, if I ever met him in person, I could ask him myself.

Almost half a year after I put my search to bed, a friend happened to share a Brooks poem on social media that I had never read before. I knew immediately that it was the poem I had so desperately looked for. The poem found me as if it were inevitable, and when I read it, I lost my shit entirely.

“To the Young That Want to Die,” by Gwendolyn Brooks, is, as I have proclaimed to homies, a banger: it’s a powerhouse, a marvel, a jewel. It serves as a manual, a list of instructions, but it also doubles as a song, a prayer, a mantra for those who might be sorry, overwhelmed, and wishing for an end. “Sit down. Inhale. Exhale.” is how Brooks’s speaker begins, addressing “the young” that the title alludes to, employing periods instead of commas to signify that each one of these steps are whole and singular and calling for our undivided attention. The poem, like Gay’s, is about death, but it is also about patience, about time:

The gun will wait. The lake will wait.

The tall call in the small seductive vial

will wait will wait:

Like Gay, Brooks lists the weapons that might be eager to harm. But here, Brooks seems to tell us that everything that wants to devour us will wait. So why won’t we?

Death will abide, will pamper your postponement.

I assure you death will wait.

Brooks turns to those who so desperately wish for release and says plainly, “You need not die today. / Stay here.” In my head, I can hear the plea between the lines. I can hear, “Stay here, please.”

And in the last bits of the poem, in a final couplet, is the seed that I assume Ross Gay held in his palms, watered, and grew into his own fruit—the lines that today make me feel most alive and furthest away from what dark and desolate corners might be calling my name.

Graves grow no green that you can use.

Remember, green’s your color. You are Spring.

*

Where (on God’s green earth!) did this gorgeous little poem come from? And why was it so hard for me to find?

Which Brooks collection did it live in, if any?

Which young—her young? The young of the world at large?—was she singing to, prompting to come down and off the ledge?

Enamored with the Brooks poem that seemed, at first, so elusive, I wanted to know as much as I could about what spurred Brooks to write it. With the title in hand, the internet told me it was uploaded to a few Tumblr sites; pinned on Pinterest; shared in a post on Prison Culture, a blog about the effects of the prison industrial complex; referenced in George E. Kent’s A Life Of Gwendolyn Brooks; and mentioned in an essay on Brooks in the Kenyon Review. A few years ago, the poem went viral after the inimitable poet Natasha Oladokun shared it on Twitter, and it has gone viral a few other times, too.

But none of these appearances provided me with more context. I was hoping something could point me toward the year the poem was born, or at least toward the original source, a collection or an anthology, or anywhere the poem might have appeared with Brooks’s will attached.

After posting on my social media, after asking everyone and anyone for clues, I only arrived at insights much later due to the kindness of a homie, Brian Baumgart, who had unearthed what I could not: a recording and a transcript of a reading by Gwendolyn Brooks herself, where she reads “To the Young Who Want to Die,” as well as a few other poems, at a celebration for Emily Dickinson and her legacy.

Giddy with the discovery, I whispered, “What year, Gwendolyn? What year?” to myself as Brooks’s voice poured into my ear, as I rewound and replayed the recording to ensure I caught each word, each detail. I had heard recordings of Brooks reading a poem or two before, but in this recording, Brooks has space to let her good mood sprawl, space to banter and make jokes. I could tell in the timbre of her voice—from her eagerness and satisfaction—that Brooks is in her element, and maybe exactly where she wished to be at the time.

And while there was no exact reference to the year of the recording, Brooks does, at one point, ruminate a bit about a time she read a poem about love in front of a group of young people, and how they snickered, how they must have thought she knew nothing of love, and by its consequence, they must have thought she knew nothing of romance. As a rebuttal, Brooks speaks to her experience with romance, and as a clue, she references her two children. Specifically, she mentions her daughter and how old she was at the time. And with that subtle, indirect marker of time, and a little bit of math, it became easy to deduce the particular year that Brooks—the one at my ear—was in.

*

1985 must have been a difficult time for the young, as must have been the nineties, and also the turn of the millennium, as, too, has been the past decade, and the new decade, pulling us slowly but surely into its calamities. Today, all my young have friends that have wished for death, and some have friends who have actually found it. But, too, all my young have friends who found comfort through exchange, through speaking what must be spoken, through giving language to whatever inside them demands language. I have friends who turn to poetry to name their sadnesses and anxieties. I have friends that speak about the art that saved their lives, that made them feel seen, that gave them language for the cloud hanging heavy above their hair. Every year and every decade seems to want to, at some point, inflict its worse upon us, and so the balm needs to be perpetual; not so much universal as potent, and liberally available. Brooks’s poem is one such balm. “To the Young Who Want to Die” is, I believe, timeless.

In my ear, Brooks tells me the poem came to be after she watched a film about two lovers who were barred from being together by their families, their parents, and their elders, and, in their desperation, decided to end their lives as a means to spend eternity together. Trying to handle the idea of suicide with care, Brooks hesitates for a bit, bouncing around what she wants to say by confirming that she is neither a therapist nor a psychiatrist, and she’s not fitted to speak on the phenomenon of suicide with authority. “But I’d just like to say,” she says, “to young people who might be thinking about doing away with themselves, feeling that they’re not important, that they have nothing to give, that they do have something to give.”

*

While searching for “To the Young Who Want to Die,” a broad view of Brooks’s indelible legacy became clear: Gwendolyn Brooks was born in Topeka, Kansas, grew up in the historically Black neighborhood of Bronzeville in Chicago, and, by the age of twenty-one, she had published more than seventy-five poems in the Chicago Defender. Gwendolyn Brooks published Annie Allen in 1949; for it, she was the first Black author to win the Pulitzer Prize. Gwendolyn Brooks taught in institutions across the United States and her books, awards, and accolades are as numerous as the cardinals and robins that populate Chicago. Gwendolyn Brooks died in 2000. By that time, she had intersected with and played pivotal roles in the poetics of countless poets.

I bring up Brooks’s name to any Black poet and the effect is the same. On the subway with S. Erin Batiste, on the very same night I meet her, I speak of my interest in Brooks’s work and, after her face ignites with glee, she points me in the direction of Brooks’s sonnet ballads. Tiana Clark reads from her new book in a Brooklyn bookstore and later, in a bar, hovering above flickering candles at a table packed with poets, I shout Brooks’s name above the bar’s music and Tiana smiles as if remembering someone from a past life, and shouts back, “Queen!” In the office of Terrance Hayes (inventor of the Double Golden Shovel, a poetic form made with the intention of honoring Brooks), I explain that Brooks keeps coming up in my work, and, with a smile crawling across his face, he spins a story about her and Robert Hayden in the eighties.

I bring up Gwendolyn Brooks to any Black poet and each time the obvious is made more evident: Gwendolyn Brooks is an ancestor to us all; we are all writing in her lineage.

*

“You are Spring.” I whisper the words to myself as I imagine Brooks might say them if she were reading them to me. In my imagination, I hear her voice as a lullaby, or a secret: soft and gentle. But in the recording of Brooks’s reading, she dances her way through each line, feeling out each word and adding her flares as she sees fit, peppering in her tiny melodies, as if to ensure no two recordings of her reading the poem would ever be the same. She arrives at the final line, that final phrase, “You are Spring” and says it as if it was the best news: the news that the war is over, that honey is still on the shelf despite the famine. She emphasizes Spring as if her speaking the word was spring itself, a spark in her voice, the sound of the word leaving her lips and bringing to life a landscape that wasn’t alive before.

*

And so I imagine it happened like this: Gwendolyn Brooks became herself as a teenager in Bronzeville and maybe, some number of blocks away and some decades later, Chance the Rapper leans into poetry while also beginning his lean into rap. His songs, like “Sunday Candy,” fall from my headphones as I walk through streets in Brooklyn. Gwendolyn Brooks becomes herself in Bronzeville and, some decades later, Eve Ewing pens a play about Brooks’s life before penning a manifesto for the young, brown-skinned girl she once was. Gwendolyn Brooks reads a poem in 1985 and says, “Remember … You are Spring,” and beneath a different sky in a different city, the poet we’d come to know as Ross Gay began to bloom. And later, Gay, himself an entire season, pushed tiny seeds into the soil of his garden before writing a line of his own and there, between the lines somewhere, is where I begin to appear.

Gwendolyn Brooks wrote poems with phrases that rippled through time and built multiple lineages each.

Gwendolyn Brooks wrote a line that asked her readers to stay alive and ain’t that a word.

Gwendolyn Brooks said stay alive and we are still alive today, writing in her name. Put that in the notes sections of your books. Put that in your craft essays, in your literary canons. Put that on everything.

Bernard Ferguson is a Bahamian poet and essayist. He’s currently working on a book of nonfiction about the climate crisis.

The Garden

Ernest Lawson, Garden Landscape, ca. 1915, oil on canvas, 20 x 24″. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Ma thought it was a good idea. That we work together in the garden. But it wasn’t a garden then, just a long rectangle of funky-smelling earth behind a two-story apartment house in the Flatbush section of Brooklyn. An elderly couple named Mr. and Mrs. Schwartz owned the house and backyard. This was in the early seventies, and already the Jews were moving out. I was ten or twelve the summer we worked in the earth. The Schwartzes lived downstairs from us in that house, and on Fridays their apartment went semidark because of the Sabbath. What a beautiful word for something I didn’t know anything about. Then, one day, I saw the tattooed numbers on Mrs. Schwartz’s arm and in a flash everything I’d learned in school flooded my mind and heart: all those bodies laid to waste, gold teeth extracted and made into something else, the gas chambers and the musicians who played as the walking dead stood naked, hoping for water, hoping to be cleaned.

And there was more. There is always more pain and beauty. Recently, a friend told me about the gardens Jews kept for Nazi families who wanted something beautiful to look at while they smelled death at work, had schnapps and what all outside, the condemned Jews not lifting their heads as they worked the earth and tended flowers, such beautiful living organisms thriving on a plantation where murder was grown and harvested. And I think of Mrs. Schwartz now as I think about the earth behind our house—her house—and the numbers blooming on her arm like flowers. I never got to ask her how old she was when she was marked like that, and did she remember or see barbed wire fencing the condemned in like the wiring around flower beds and vegetable beds our innocent neighbors used to keep predators out? Nor did I get to say to her, even as those numbers on her arm blossom and die in my memory, What is it about flowers that no matter where they’re grown—in death camps or by the sea, in private homes or on the border of war zones—why is it they keep on flowering while insisting on their right to inspire feelings in us that we can barely know, or articulate in all our truth and terribleness?

When I think about the Schwartzes, I think about their building, our home, and I think about the steep staircase leading up from the street to our apartment, and the long shape of our apartment itself, and the fact that we lived next door to a gas station where fumes bloomed. This is the only apartment I have vivid memories of—we moved a fair amount when I was a kid—and part of what I remember about it is the garden or, more accurately, how the garden came to be.

It wasn’t anything but overly fertilized rust-colored dirt when Ma said she thought something could grow there. She was always trying to make a family, and to make that family grow. But there was so much bad earth. Our father didn’t live with us; for most of the time I knew him, he lived with his mother, in Crown Heights, a bus ride away. It had always been this way. My parents visited, and on weekends out my father took me and my little brother on long walks around the city. We saw the beautiful consumerist goods on Madison Avenue, and, in the Village, heard women catcalling to passersby from the Women’s House of Detention. Rainy days in Chinatown, and some snowy days at the Guggenheim Museum, or looking at the precipitation falling on the stone lions at the New York Public Library. And then there was my father’s hand, or, more accurately, certainly from an emotional point of view, my hand in his tougher rougher bigger hand and it was the best foreign feeling in the world: I knew his hand but not him, and even now that feels like defeat, my remembering the pleasure of my hand in his, and all that I wanted from him that wasn’t forthcoming. My dreams of him were always tied up with things ending—at the end of our Saturdays together, he took a gypsy cab home—and so with a kind of death. On some level I must have wanted him to stay even though I couldn’t stand him, or stand him leaving. In any case, I can’t believe these memories continue to make me vulnerable to him, the way flowers are to our human hands—cut them or leave them alone? Water them or let nature take care of them? The flowers are vulnerable to us!—and remind me that all I want to do is find my father again, but in a better person, a he who will protect me from the original father who maybe taught us how to cultivate flowers, but certainly not how to find soul-nourishing love when it’s needed, which is always.

I don’t remember when my mother suggested growing flowers. But for sure her impulse was in part inspired by her desire to keep looking for activities that prompted and encouraged our father to be a father to his sons. That was part of what mediocre therapists might call their dynamic—her hope and his pulling back, her cajoling him and telling him what he must do, and him doing it sometimes, but always grudgingly. Daddy was Ma’s only real baby, or the only one who was allowed to be a baby. I remember her saying she would ask the Schwartzes about the land, and I remember my father standing with me at the Schwartzes’ door soon thereafter, and the deeply kind Mr. Schwartz telling my father that the dirt back there had been overly fertilized by someone a long time before, and it had been left untended after that. In my memory or my imagination, which is usually the same thing, my father says to Mr. Schwartz, I’ll take care of it. Or perhaps it was my mother who asked the Schwartzes about the ground, then decided we would make the best of it. Because that’s what she always did. And maybe what I wanted my father to do.

*

To get to the backyard, you had to go through a dank dark cellar. Once done, you were standing at the border of that filthy, rank-smelling earth. It was always cold in the basement; it was like someone’s idea of death. I wonder what flowers grow in the cold; flowers commemorate death, we know that, but I wonder what buds in the cold, or in the bad earth. I don’t know anything about flowers even though flowers will bury me in the end.

Mr. Schwartz didn’t lie: the earth in the backyard was bad, and it stank of neglect. But my mother was determined that we make something of it—a place for flowers—and I don’t think her wish had anything to do with reality; are wishes even part of what’s possible; reality didn’t apply to my mother’s wish that my father be a father. I was probably the same about flowers, meaning in my mind they were one thing and I hoped they’d be another. I had an interest in flowers but not in growing them. That is, I loved seeing bouquets of love in a given movie protagonist’s arms—Ginger Rogers, say; she was always starring in movies, in the forties in particular, where some guy was always giving her flowers after a fight or an unexpected reconciliation—but what did that have to do with now, and me and my little brother making rows and holes and then watering what we couldn’t see growing in the earth, let alone admit to in our hearts? Were flowers only for white people in the movies? We put things in the ground and hoped for some kind of best, but where was the best, and with whom? Once flowers began to grow—would that be proof of my brother’s dedication and diligence? Or mine?

But before all that—before we could plant anything we had to clear the area of bottles, cans, and other debris that people had chucked in earth that wasn’t even ours. Junk stood in the brown with hints of red soil like urban flowers, and as we collected that trash and threw it into big plastic bags, I felt the nausea I have always felt when looking out, or handling waste: wasted. As if all the hours of the day are bullshit and all the love you wanted to have for Daddy was a joke, and always would be, and all the love you could hope for was emptying to the soul as picking up after someone else’s carelessness in a yard God had apparently forsaken.

But not Ma. She wouldn’t forsake her dreams of a garden, which is to say a family. But could flowers bring us together? As my brother and I planted seeds, Daddy sat away from us, doing what he mostly did when we were together: he read the newspaper, or the Racing Form. After he showed us—from a distance—how to make rows, and water and plant, he appeared to be as interested in us creating flowers together as those people who had dropped empty Coke and beer bottles in our earth. Ma wanted to make a garden—something that lasts—in a rental situation. That just occurred to me—we didn’t own the earth we were working. And yet, despite that fact, Ma wanted the last event of flowers to be ours. I have spent most of my life thinking about how she flowered with such hope despite the facts. When I told someone I know a little bit about the scene—my father reading the Racing Form while me and my brother were out there—he said, Like an overseer? I was startled by his remark. Was it all so obvious, so “political”: working land that wasn’t ours, Daddy as the overseer, my little brother and I were indentured to some idea of Daddy, that if we got the garden right, he would get us. And, once gotten or understood, he would pick us up like bouquets made up of beautiful blooms that defied the smell of our sad hopeful flesh in his presence. (We burned in his presence, burned, and burned.) And after cradling us as tenderly as Ginger Rogers cradled her flowers, he would hand his boy bouquet over to our Ma. Standing there, holding us all, she was finally buried in the blooming family she always longed for, and we were no longer a dream, but as real as a garden that didn’t belong to any of us, but what did that matter when there was so much hope and so many flowers just around the corner?

Hilton Als began contributing to The New Yorker in 1989, writing pieces for Talk of the Town. He became a staff writer in 1994, a theater critic in 2002, and chief theater critic in 2013. He has received a Guggenheim Fellowship for creative writing, a George Jean Nathan Award for Dramatic Criticism, the American Academy’s Berlin Prize, and the Pulitzer Prize for Criticism for his work at The New Yorker in 2017. He is the author of the critically acclaimed White Girls, a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award and the winner of a Lambda Literary Award in 2014. A professor at Columbia University’s writing program, he lives in New York City. Read his Art of the Essay interview.

Excerpted from (Nothing but) Flowers , published by Karma Books, New York, later this spring, reprinted by permission of The Wylie Agency LLC.

February 12, 2021

Staff Picks: Bathing Suits, Bright Winters, and Broken Hearts

Still from Black Bear. Courtesy of Tandem Pictures.

Lawrence Michael Levine’s fourth feature, Black Bear, really messed with my equilibrium. I first saw the film as part of Nightstream, a collaborative virtual horror film festival, so I guess I shouldn’t be surprised that it stirred up something deep in my psyche. The plot unfolds in three distinct strands. One follows a filmmaker and former actress named Allison (Aubrey Plaza) who heads to a wooded retreat to seek inspiration for her next film while navigating the awkward tension of the cabin’s caretakers, Gabe (Christopher Abbott) and Blair (Sarah Gadon). The second departs from almost everything established by the first, picking up on the final day of shooting for a film directed by Gabe and costarring Blair, whose apparent chemistry with Gabe informs Allison’s starring performance at the cost of her sanity. The third strand involves Allison meditating by the lake in a red bathing suit. Feeling disoriented yet? Fear not. Black Bear delivers plenty of laughs from a stellar supporting cast and a career-best performance by Plaza. This cabin-in-the-woods head trip is well worth the spins. —Christopher Notarnicola

Sion Sono’s Red Post on Escher Street—now streaming online as part of the Japan Society’s 21st Century Japan film series—is a love letter of sorts, a two-and-a-half-hour film about filmmaking that follows a director named Kobayashi as he attempts to cast his latest project with unknowns, much to the consternation of his producers. Its scenes have the loose anything-could-happen feel of improvisation; its characters—a group of girlfriends, a young widow, a hilarious Kobayashi-themed fan club, a legendary and slightly pathetic movie extra, a woman whose father has just stabbed himself following their incestuous affair, and a ghost—run the gamut from silly to serious but are always interesting. It’s the last twenty seconds of the film, though, that really captured me. In those seconds, the camera suddenly turns handheld, the location switches to the famous Shibuya Crossing in Tokyo, and two actresses, in a moment of guerrilla filmmaking, launch into a speech exhorting the unsuspecting audience to not be extras in their own lives. There’s a certain quality that good art has, a sensation that it sparks within me, that I can describe only as “it makes me feel alive.” Watching those last twenty seconds of Red Post on Escher Street, pent up and cooped up in my apartment as we lurch into a full year of quarantine, I felt something click. I felt that swooning, whooping kind of happiness, of possibility, that good art makes you feel. Simply put: I felt alive. —Rhian Sasseen

Anna Keesey. Photo: Chandra Ferguson. Courtesy of Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

In 2013 I read a short story called “Bright Winter,” by Anna Keesey, which has more or less haunted me ever since. Early in the year of 1844, a father writes letter after letter to his Adventist son, scoffing at the disorderly religious fervor that pulls at the seams of their town, pleading for him to come home with increasing sadness, and noting all the while disconcertingly warm weather. After seven years of thinking about this story, I realized I could read Keesey’s novel, Little Century, which I wolfed down in a few days. Keesey imagines a most refreshing Western in which an eighteen-year-old Chicagoan named Esther Chambers strikes out for the Oregon high desert after her mother dies. There, she decides to help her handsome older cousin with a little homesteading fraud and thus becomes embroiled in the brief but exciting life of the town of Century (est 1900). Esther won me over when her elaborate daydreams about her new frontier lifestyle on the train ended with the thought “How did one make cheese?” She knows nothing, but it’s fine—remember being eighteen? She learns a novel’s worth. Century is a hard place, but in Keesey’s hands, Esther experiences not a simple descent into cynicism but an organic grafting of youthful earnestness and lived experience that yields a full-fledged character. Moreover, the language shimmers; there is pleasure in reading and rereading each sentence. I am distressed that there are no other Keesey books to read at the moment, but I’ll be glad to think about Little Century for years to come. —Jane Breakell

William Parker, the stalwart torchbearer of New York’s free jazz scene, has just bestowed upon the world a treasure chest of music in the form of the ten-disc box set Migration of Silence into and out of the Tone World. The set comprises ten complete albums of new material written by Parker and performed by one or another configuration of the dozen musicians who participated in this project, which focuses on female voices, both instrumental and vocal. Much of the music is lyrical and funky, composed rather than chaotic, and most of it feels very positive and uplifting. As a lyricist, Parker is a bit cosmic and, um, happy for my tastes, but if you’re like me, you’ll focus most of your attention on the singing rather than the words. On that front, the disc called Cheops, which features the experimental vocalist Kyoko Kitamura, is stellar, as is Harlem Speaks, with Fay Victor singing, Parker playing bass, and the amazing Hamid Drake playing drums. The disc I’ve listened to most often, however, is Child of Sound, a solo piano performance by Eri Yamamoto. I love solo piano music for its focus and the room the instrument leaves for musical crannies and meaningful silence. I don’t like every album in the set, and this is far too much music to take in at once, but there’s so much here to love that I suspect I’ll be falling in love with parts of this work for a long time to come. —Craig Morgan Teicher

The narrator of Sarah Rose Etter’s The Book of X has a stomach twisted in a knot. I’m not speaking metaphorically here, not referring to her anxiety or her nerves—Cassie’s torso quite literally takes the shape of a knot, a genetic condition shared among the women in her family. The Book of X, published by Two Dollar Radio in 2019, follows Cassie from her childhood on her family’s meat farm, where they reap their harvest from the Meat Quarry by pulling armfuls of the stuff from the walls, to her adulthood in the city, where she works as a typist and cycles through various men, all the while navigating the physical and emotional pain caused by her body. Interspersed in the narrative are dreamlike visions in which Cassie imagines a life different from her own. The Book of X is jarring, surreal, and definitely weird. Carmen Maria Machado calls it a “gorgeous, grotesque, heartbreaking novel.” Roxane Gay says it “viciously lays bare what it means to be a woman in the world.” I recommend The Book of X, yes, for these reasons—it is gorgeous and grotesque, and it did break my heart—but also for its sheer strangeness. A knotted torso? A meat quarry? Etter is certainly commenting on our world, and she does so with incredible, sharp, and visionary invention. —Mira Braneck

Sarah Rose Etter. Photo: Natalie Graf. Courtesy of Two Dollar Radio.

People-Shaped White Rocks

Jean-Antoine Houdon, Madame His, 1775, marble, 31 1/2″ tall. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Eugene Victor Thaw, 2007.

There are few uncooler-sounding words than “eighteenth-century marble portraiture.” Even typing these words makes me feel like I’m prepping for the PSAT. But eighteenth-century marble portraiture—specifically that of Jean-Antoine Houdon, known for his uncool likenesses of Voltaire and George Washington—can be extraordinarily strange. Furthermore, the examples here are nearly nowhere to be found on your phone except in lo-res preview form. In other words, you have to actually go to the Frick to see them.

Two busts, sculpted within two years of each other, are paired in an out-of-the way hall of the museum: a woman, Madame His, and a man, Armand-Thomas Hue. Translucent, actual-sized, people-shaped white rocks carved in Enlightenment dress and balanced atop quadrangular pedestals at eyeball height, both are lopped off somewhere above the waist and function as the sort of thing that museum-going twenty-first-century humans are likely to walk right past and think, “Oh, art.” Which is just what I did, on my way to the Bellini painting I’d planned to write about. But something stopped me. Madame His doesn’t look like the majority of eighteenth-century painted portraits I’d seen, which largely crash-land somewhere in flyover caricature country: big watery eyes, boiled-egg chins, tiny red lips. As I circled the bust, I increasingly admired how it substantiated my mental template of “actual human being,” how Houdon had worked outside his epoch’s stylizations. I was surprised by how the marble skin seemed to suggest hidden muscles and tendons, by how the slightly rougher fabric of the bodice lightly met her soft shoulders. Then I looked up, and something even more surprising happened: Madame His met my gaze.

As any kid with a crayon knows, the human eye is attuned to finding faces. Two dots will fix the seen for the seer, and vice versa; we are constantly seeking to pin other consciousnesses down, catching in our headlights the thoughts of others at our shared twin fulcrums of empathy. That ubiquitous 1975 smiling yellow disc proves it. But in art, it’s up to the artist’s skill and sensitivity whether the sensation of life or the sentiment of “have a nice day” is the result. So it’s to Houdon’s credit that at that moment in front of Madame His, the chasm of the centuries sprang together, and I felt, if just for a moment, like I was uncannily and most genuinely in the presence of someone two hundred years dead. Even more painfully, if I moved ever so slightly one way or the other, she turned once again to stone—not unlike the passengers on the plane with whom I’d traveled to New York, nearly all of whom had closed the shades of their windows to more effectively bury themselves in the light of their screens.

On that flight, I’d sat next to a sixtyish woman in an alarmingly bright red dress. (Her dress was the detail I remembered most as I’d only gotten in a couple of sidelong glances at her, but I also noted her frizzy chestnut hair, square silver earrings, and slightly downturned nose.) Despite more than two hours spent sipping complimentary soft drinks and crinkling pretzel bags within five uncomfortable inches of each other, we—agreeably—didn’t exchange a word and parted at the LaGuardia jet bridge forever. I had completely forgotten about her until the following morning at the Frick, when I looked over from a painted slice of the Renaissance and there she was, right next to me, again: the same alarming red dress, the same frizzy hair, same square silver earrings, same nose. I began to seek the right words to try to express how fabulously weird it was, here in a city of millions, that we’d cross paths twice. But she clearly hadn’t noticed me either on the plane or at that moment, and she turned and walked away.

Madame His’s hallway companion in eternity, Armand-Thomas Hue, won’t look at you either. Try as you might, you absolutely will not be able to meet his eyes. I wonder if this was Jean-Antoine Houdon’s subtle aim, as it ultimately says more about his subject and is almost more of an artistic accomplishment than what he managed with Madame His—and also because it’s what most of us spend our lives actually doing.

Jean-Antoine Houdon, Armand-Thomas Hue, Marquis de Miromesnil, 1777, marble, 25 1/2″ tall. Purchased by The Frick Collection, 1935.

Chris Ware is an American writer and artist who has contributed graphic fiction and covers to The New Yorker. Among his numerous books are Rusty Brown (2019) and Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth (2000), which won the Guardian Prize. His work has been exhibited at the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Jewish Museum in New York, among other institutions.

From The Sleeve Should Be Illegal & Other Reflections on Art at the Frick , published by The Frick Collection in association with DelMonico Books ‧ D.A.P.

February 11, 2021

And the Clock Waits So Patiently

The following essay appears in But Still, It Turns , edited by Paul Graham and published by MACK earlier this month. The book accompanies an exhibition of the same name showing at International Center of Photography (ICP) until May 9.

Gregory Halpern. Image from ZZYZX (MACK, 2016), in But Still, It Turns, edited by Paul Graham (MACK, 2021). Courtesy of the artist and MACK.

Time, unfortunately, though it makes animals and vegetables bloom and fade with amazing punctuality, has no such simple effect upon the mind of man. The mind of man, moreover, works with equal strangeness upon the body of time. An hour, once it lodges in the queer element of the human spirit, may be stretched to fifty or a hundred times its clock length; on the other hand, an hour may be accurately represented on the timepiece of the mind by one second.

—Virginia Woolf, Orlando: A Biography

I don’t know whose side you’re on,

But I am here for the people

Who work in grocery stores that glow in the morning

And close down for deep cleaning at night.

—Jericho Brown, “Say Thank You Say I’m Sorry”

I

Now, wherever and whenever that is for you

Dark stars inked on the palm of a raised hand. A tiny blackbird alone in the gaping, giant world of a street curb. Someone crouching in asphalt-baked sun in a position of prayer or pain or ecstasy, or perhaps all of the above. A guy kneeling to cut open a watermelon as two mothers perch on the edge of a gas station parking lot, their children swarming close. The craggy shadow in the desert cast by a rock face; the man in a poncho crossing a thin creek over tall, shadowy grasses. The herculean act of pushing a massive tree down the middle of a rural Alabama street. A young boy fitting his small body in the space between tire rim and hub of a car, draped around the curve of the wheel. The frozen, shouting faces of a lineup of white cheerleaders some sixty years ago and, in an image from perhaps the same year, a white mother teaching her little girl to shoot a gun. A deer running down a highway embankment, between roads.

We know that a photograph lives in multiple eras at once: the time of its making, the time of its unveiling, the various eras of its subsequent rediscovery. Lazy language has us reaching for the trope of “capturing” “a moment.” Similarly it is ingrained in us to look at photographs as stilled time, as past. But even this is a relative condition. The perception of the past is split in the act of remembering: how a moment first appeared, how it is seen differently later and reseen again, taken out of isolation, reshaped by knowledge and context. How the singular is part of a larger sequence.