The Paris Review's Blog, page 121

March 18, 2021

Isn’t That So

In 1954, the Austrian poet Friederike Mayröcker met her life partner, Ernst Jandl, with whom she would live and collaborate for nearly half a century. In the wake of Jandl’s death, in 2000, she wrote a series of books documenting the swirl of her grief. Two of these memoirs have been translated by Alexander Booth and compiled as The Communicating Vessels, which was published by A Public Space Books earlier this month. A selection from one of the books, 2005’s And I Shook Myself a Beloved, appears below.

Ernst Jandl and Friederike Mayröcker at a public reading in Vienna, 1974. Photo: Wolfgang H. Wögerer, Wien, Austria. CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...), via Wikimedia Commons.

In the end people are unconscious / so : when they are alone they want to be with others, and when they are with others they want to be alone, so Gertrude Stein, and my maternal grandmother had the habit of not being able to spend a lot of time in one place : at a tavern with her family she wanted to be at home, at home she complained about having to be at home and that no one came to visit, when someone came to visit she yearned to retire to her room or take a walk, I have inherited this unquiet body of hers this character, standing too, leaning against a window or door, standing balancing a bowl from which I’d eaten and drunk while standing, and I can’t spend a lot of time in one place, and whenever I visit someone, walking in, I say I can’t stay long.

I never knew what to say, I was unable to start a discussion or join a discussion because I am unused to being with others, isn’t that so, preferring to talk to myself or reading a book, which, outside of writing and walking, is my favorite activity, etc.

Because my throat, I mean, my throat is tied and making me cry, which is always a sign of having a lot of work to do, isn’t that so, here in these legendary surroundings I am familiar with the sky and whether it has something to say or reveal about the weather to come, which means I am so familiar with the little sheep when they come, and the vapor trails disappearing beneath them, and I have learned that a whirling evening wind means rain the following day and, likewise, when I am in unfamiliar surroundings and unfamiliar with the sky’s signs I just have to let myself be surprised by the weather the following morning, isn’t that so.

But my eyes were more important than my ears, so Gertrude Stein, and it was always polite to be there, at every reading, and walking into the room Ulla said, WE ARE ALWAYS AT WAR and I was surprised, and it was a flurry of thought, and in my lap the scraps of paper warbled, as I write, as I move, and it floraed all around me and I shook myself a beloved, well, now I have a lit. dog, and in the mornings and afternoons I’d go to Drasche Park, and I enjoyed it though my lit. dog did not pay the slightest attention to me as we walked, astonishing, and so up one street with my lit. dog then down another, and that made me happy, and then another lit. dog walked up : namely, EJ called me from Berlin and said, I’ve found a large flat in a beautiful villa, and there’s a neat lit. dog, too, and you’ll like everything, and so we moved to Berlin for a year and met a lot of people and had a lovely time.

I sleep most of the day because of all the medicine, at night I wait for EJ to speak to me in my dreams, I often dream of him, he acts the way he did when he was alive, I have no fixed ideas about the beyond, sometimes I am afraid to imagine it, sometimes I play with the thought of how it might be, sometimes the feeling that there is no beyond, I read a lot, writing’s only possible when I have these wings, that’s my secret, how much longer do I have to live. My wrinkled forehead, until now no serious illnesses found, which means I could be happy, at times I even am. I don’t know if I believe in God, I pray to him, I guess I believe in him, I cross myself before every church but do not go to Sunday Mass, why not, I beg for his blessing, I ask his blessing for writing, for my health, for the well-being of my dead parents, for EJ’s wellbeing, I’ve made a note: The Gout Register, no idea. I hope I have a lot longer to live, there are so many things I still want to do, the sm. Ischl in the Kaiserlichen Park of Bad Ischl, I feel the summer wind on my arms and legs, cheeks and forehead, but from time to time it’s cool, rainy, past the same shopwindows a hundred times, and it all repeats, year after year, but how long will everything keep allowing itself to multiply, I believe very strongly in the Holy Ghost, the wings too, but that’s my secret, etc. I’m listening to the end of Arthur Honegger’s Le roi David oratorio, a powerful composition, I’m in the spheres, no flurry of thought but a vision of light while listening, ravishing music, etc.

I could hardly write a thing in Berlin because I’d go on walks with the lit. dog, whose name was Fifi, for hours every day, we lived in the area of Krumme Lanke with its lake and delightful landscape and I would go walking with Fifi, and I see myself, I still see myself the way I do everything and I see myself in moments from long ago, that is, as if I had continuously taken snapshots of myself, I see myself, e.g., at night, after visiting Barbara Frischmuth, stepping out of her house and thinking, I’d be afraid to live in a house all by myself, and as if she’d read my thoughts from my forehead she said, I’m not afraid of living here alone.

On the front side of the shortened tram in huge letters I dream: MISSING CAT, we went into the garage to get the car and once again she said she wasn’t afraid even though her closest neighbor was rather far away, we were in that village world and I dreamed “Ovidian cadences” and whenever we, EJ and I, talked about our trip to America we always had to think of the East Coast first and Washington and as to Washington nothing but our trip to a Laundromat where we were helped by an old white-haired African American, he had large yellowish eyes, and we talked about New York, we talked about how we stayed at the Algonquin and at breakfast ran into Siegfried Lenz, who was waiting for his translator, but he was so lost he barely saw us, and how at first we stayed in a dirty hotel that we left again immediately and how we went walking down Broadway and someone told us always keep a few coins in your pocket, etc., they’d come in handy if we got robbed, but we never got robbed and the coins jingled in our coat pockets on our way back home, and how Boston was the only city in America that seemed completely European, and how our trip out West took us only as far as Bloomington, where EJ had an acquaintance, and south to Miami, which impressed me, what with the Atlantic sloshing up against the hotel window or me at least imagining it did, and the vegetation seemed paradisiacal, the only thing we didn’t like, I said, were the air conditioners as soon as you stepped into a building or a cinema so that, instead of taking off whatever we were wearing on top, as usual, we had to put on everything we had, I froze in all the buildings, and I asked myself why it was so excessive, was it simply fashion or a habit, and the second thing we didn’t like was that, in some hotels, we didn’t receive any breakfast, which meant that first thing in the morning we had to wander the long streets to find a place with coffee and muffins and sit on a barstool, swinging back and forth, what an uncomfortable way to breakfast the Algonquin was the only exception : there we received breakfast, and then I paused, I traced.

And then we began to call each other using only our first names, my editor and I, on the phone, and when we talked about friends in common we only talked about José and Sara and Ulla and Jacqueline and Lutz and Katja and Wolfgang and EDITH, strangely enough, one talks to oneself about chestnuts and walnuts and hazelnuts and beechnuts, one talks to oneself about how many one finds and whether they’ve got worms, one talks to oneself about apples and pears and grapes and the kinds one likes the most, in times of war, one talks to oneself about caterpillars but never about spiders or lizards, one talks to oneself about dogs and cats and rabbits but not about bats or mice or moths, so Gertrude Stein, yes, but I am subjected to a step back, a regression, a mountain station, just like how lit. old ladies begin to get cheeks again, like lit. children, babies at the breast, isn’t that so, and so that late summer afternoon I walked up the Waldstrasze, which isn’t too steep and covered in asphalt, and saw ants in droves at my feet, walking over one another, and all the trees seemed bent some of them stretching their main branches in the same direction, in other words, toward the slope of the meadow, it was the end of August and the trees had already begun to lose their leaves, the evening wind blew from the NW and cooled our cheeks, cozy tears, and there was that bag with the swans.

And the huge stones with hieroglyphs and hearts from the coast of Crete that EDITH had brought me lay at my feet in my writing room, and my feet were naked and I thought about the sea and waves and going under and swimming backstroke, which I wasn’t that good at, and all the while I howled and howled, mornings and evenings I couldn’t stop scribbling and howling, in other words, a regression, a regression into puberty, EJ constantly looking into Lili’s eyes at the pub, yes, literally going under in Lili’s eyes, first her left and then her right, and as if wanting to excuse him she said, it’s because I have a rather peculiar iris, and he could not get enough of her, then suddenly he had to tear himself away from her iris, and she knew how often a clock would strike.

And I said to EJ, I can learn a lot from my old doctor, I could learn a lot about life, I say, especially as far as discretion’s concerned, she is the most discreet person and was unable to stand one of her chauffeurs because, as she said, he had no discretion, she always said, he is not discreet, everything he should keep to himself just comes right on out, etc., my old doctor especially reminds me of the figure of Gertrude Stein and I admire her immensely, she is very cultured, she likes to laugh, but she can also take command or be jealous, this arm of blooms.

And over and over we told each other how much we had liked Boston, yes, that it was basically our favorite because it seemed so European, and whenever EJ and I talked about our trip to America we affirmed to each other how much we had liked Boston, indeed, it was our favorite and we repeated ourselves constantly until all we could do was laugh whenever one of us began to speak about Boston, and because everywhere and, most of all to my friends, I said, ach, I’d like to write ONE more big book before I have to go, now I’m afraid, I mean, even more afraid that everything could turn out to be true, I mean, now I’m more afraid of dying than ever before, while my old doctor, to whom I also said, I want to write ONE more book before I die, just smiled and said, I am not afraid of dying whatsoever, I am ready to die at any moment, namely, prepared.

And Elisabeth von Samsonow wrote me a guardian angel for the throat and a dress into which the soul too can climb, and that certain South American doctors can lure the soul back to its ancestral home by waving clothes at that very place where a patient is scared… you’re no doubt out and about a lot and incubating a new book, a bit like Paracelsus writes : “the generation of things with sensation in the soul,” it was gorgeous and the whole day glowed with the beautiful feeling of friendship, etc., then stay healthy while you work, my old doctor said to me on the phone and I write everything down on back of all the fax paper I’ve received from Mario, and my blood pressure was up because, in my head, I was writing and writing constantly while Elisabeth von Samsonow had written me a double-sided letter I really loved and kept with me at all times, I ate a fig and said to EJ, I have to buy Bach’s complete works, I need the complete works because on the radio only the tiniest of tastes, etc., only ever Mozart… (“go for a walk down the beach today like Ely…”). Back then, I say to EJ, back when the RADIOPLAYDAYS were beginning, I didn’t trust myself to ask Paul to house Ely and me together in the same youth hostel so I could be near him day and night and so instead I struggled but did not waste a single opportunity to escape to meet him, to talk with him, to seek contact, and so, being with Ely the whole time, that was the story with Ely but it’s been over a long time now, I say to EJ, and it floraed all around me and I shook myself a beloved—

I am ablaze, I say to EDITH, but I am not allowed to talk about it at all, I am not allowed to accept it at all or it won’t continue, I say to EDITH, I didn’t hear a thing, EDITH says, just reswallow the fire like the fire-eater does, EDITH says, the light was flickering in the other room and it’s like a bat twitching over our heads as evening breaks it’s like lightning, and I am in another world, I say to EDITH, and I don’t understand that it won’t always be this way, and in the morning I ran into a man with a white turban who looked at me, I was in another world, namely, on one day I am different than the day before, thus when on Tuesday I can write on Wednesday I can’t and have no idea how I could do so the day before, etc., on Wednesday, e.g., I was so far gone I felt like I had never written a thing, isn’t that so, and I was amazed that I’d been able to write anything at all because on Wednesday the thought of ever having written had completely vanished, was utterly unimaginable, as when someone who had never written hears something about being able to write—it was completely UNREAL / UNEARTHLY.

*

And whenever the fax bell rings I think and hope it’s you, I say to EJ, and that you’ll tell me about your world, how exciting it would be to hear your voice telling me how you are, what you’re up to, whether you listen to music or the nature of the fires you’ve been making your way through, in other words, from one fire to the next, and do you still think about me?

—Translated from the German by Alexander Booth

Friederike Mayröcker was born in 1924 in Vienna. One of the leading figures of German literature, she is the recipient of numerous honors, including the Georg Büchner Prize. Among her books to have been translated into English are brütt, or The Sighing Gardens and Scardanelli.

Alexander Booth is a writer and translator who, after many years in Rome, at present lives in Berlin. His work has appeared in numerous print and online journals and he is the recipient of a 2012 PEN/Heim Translation Fund Grant for his translations of the poetry of Lutz Seiler.

Excerpted from The Communicating Vessels , by Friederike Mayröcker, published by A Public Space Books. Copyright © 2005 Suhrkamp Verlag Frankfurt am Main. English translation copyright © 2021 by Alexander Booth. Reprinted by permission of A Public Space Books.

March 17, 2021

Memoir of a Born Polemicist

The following serves as the introduction to Vivian Gornick’s new collection Taking a Long Look: Essays on Culture, Literature, and Feminism in Our Time , which was published by Verso Books this week.

Vivian Gornick. Photo: Mitch Bach. Courtesy of Verso Books.

I can remember the exact moment when I left polemical journalism behind me to begin the kind of nonfiction storytelling I had longed, since childhood, to write. One summer morning, on vacation from my job at the crusading Village Voice, where I wrote most often on behalf of radical feminism, I sat down at a makeshift desk in a beachfront hotel room and found myself typing: “I’m eight years old. My mother and I come out of our apartment onto the second-floor landing. Mrs. Drucker is standing in the open doorway of the apartment next door, smoking a cigarette.” These were the first sentences of my memoir Fierce Attachments, and with them I began the long apprenticeship of a writer who, in the act of making naked use of her own undisguised experience, has taught herself to value writing that serves the story rather than writing that imposes itself on the story. By which I mean: as a polemicist I went in search of stories that would illustrate my argument and then used the language I thought would best make it; as a memoirist I developed a set of interacting characters and let them find the language that would best express their situation.

*

I was in grade school when a teacher held a composition of mine up to the class and said, “This little girl is going to be a writer.” I remember being thrilled but not surprised; somehow, the prediction sounded right even then. Decades later, in college, I took the few available writing courses (there were no writing programs then) and again, the teacher (a tough-talking, working-class novelist) pronounced me a writer. This time I was proud because everyone in those classes considered this teacher’s nod of approval an anointment. The week before graduation I went up to his desk and stood dumbly before him.

“Yes?” he said.

“What do I do now?” I said.

“Write,” he said.

“About what?” I said.

“Kid, get outta here,” he said.

So I got myself day jobs—office clerk, per diem high school teacher, editorial assistant—and I wrote. Mainly, I wrote short pieces: my mother and a neighbor talking about an abortion over my four-year-old head, an immigrant marriage in a public garden, a rally at City Hall calling for the mayor’s dismissal. Lame, all lame. I’d read these pieces over and I’d see that the language was pedestrian, there was no ruling structure, and the narrative drive was languid. The problem, I finally understood, was that there was no real point of view; and at last I saw that the point of view was missing because I actually had nothing to say. I was simply accumulating what another writer once called “black marks on a sheet of paper.”

Then one evening in the late sixties I was present at a public meeting in which Black people and white people fell out violently over who owned the civil rights movement. The place had exploded with emotion—loud, angry, threatening. I felt the heat building in my chest. I, too, wanted to be heard. But I didn’t have the courage to brave the chaos in the room so I determined to commit the scene to paper. I can still feel the urgency I experienced that night as my fingers flew across the keyboard, and the excitement as I worked to disentangle a set of thoughts and emotions that were—transparently!—begging to be made sense of. It came to me that what I wanted badly was to put the reader behind my eyes—see the scene as I had seen it, feel the atmosphere as I had felt it—and to use my own left-leaning, literary-minded self as what I thought of even then as an “instrument of illumination.” I had stumbled on the style that was becoming known as personal journalism and had immediately recognized it as my own.

The thing I now find interesting is that in the morning I put the piece in an envelope, took it to the corner mailbox, and without hesitation sent it off to the Village Voice. It never occurred to me to send it to The New Yorker or the Times or any of the many respectable publications then in existence. No, the Voice, I instinctively knew, was where I belonged. And, indeed, the Voice not only published this piece: within a year I was on its staff, where I remained for a good ten years, allowing counterculture journalism to slowly—very slowly—teach me my profession.

It took a while for me to realize that polemics had supplied me with a built-in point of view; and then another, even longer while, to realize that this point of view was articulated by a persona—the narrating voice I pulled from myself to tell the story at hand—that determined everything about the piece: the shape of its structure, the tone of its language, the arc of its direction. Even more important, in time I came to realize that when the sights of this persona were trained outward—that is, on politics and culture—it served one agenda, and when trained inward, another: the first resulted in personal journalism, the second in personal narrative.

But no matter: ultimately everything went back to the dominating question of a point of view. Even though, as I have said, mine at the Voice was the inherited one of the born polemicist, just having one had taught me to take seriously the matter of knowing when I had something to say, and when I was spinning my wheels and simply putting black marks on a piece of paper. After I’d left the Voice and drifted away from openly polemical writing, I saw that, for me, my viewpoint would have to originate elsewhere. I began to write essays, memoirs, book reviews in which I paid more and more attention to a point of view served by an unsurrogated persona who was going to do all in her power to find whatever valuable story was waiting to be rescued from the material at hand.

Taking a Long Look, then, is a collection of pieces written over a period of some forty years that demonstrate, I hope, the apprenticeship of a writer whose critical faculties have been shaped by the hard-won knowledge that reading into the material is energizing but reading out of it is infinitely more rewarding.

Vivian Gornick is a writer and critic whose work has received two National Book Critics Circle Award nominations and been collected in The Best American Essays 2014. Growing up in the Bronx among communists and socialists, Gornick became a legendary writer for the Village Voice, chronicling the emergence of the feminist movement in the seventies, and a respected literary critic. Her works include the memoirs Fierce Attachments—ranked the best memoir of the past fifty years by the New York Times—The Odd Woman and the City, and Unfinished Business: Notes of a Chronic Re-Reader, as well as the classic text on writing The Situation and the Story. Read her Art of Memoir interview.

From Taking a Long Look: Essays on Culture, Literature, and Feminism in Our Time , by Vivian Gornick. Used with the permission of the publisher, Verso Books. Copyright © 2021 by Vivian Gornick.

March 16, 2021

Poems Are Spiritual Suitcases: An Interview with Spencer Reece

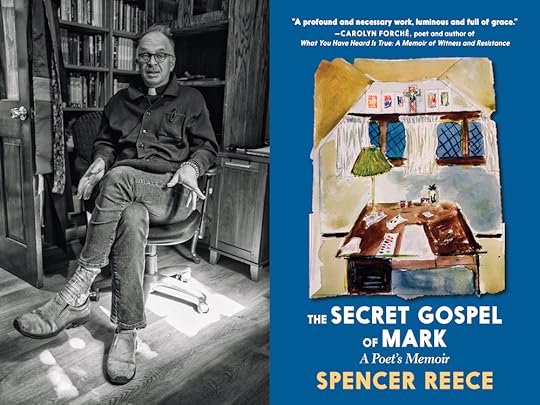

Photo: Pete Duval.

Spencer Reece’s memoir, The Secret Gospel of Mark , feels like what it is—a product of remarkable time and care. It took Reece seventeen years to write the book, and however much he wanted it to be done earlier, he kept waiting for and working toward a rightness that eluded him. I can’t remember anymore how I stumbled into that process. I’d occasionally written to him over the years to tell him how much I admire his poems and to share what I’d written about them, and somehow, at some point, that resulted in him sending me a draft of the book.

By then, Reece had already discovered the structure he credits with unlocking the book—one in which he defines and shapes each part of his life through the life and work of a poet who was important to him at that time. But he still wanted help, which, as Reece presents it, is one of the defining features of his life. For all of the ways in which he once struggled to make a life for himself outside of—and then, eventually, inside—the social structures that refused him and his queerness, he has also inspired a remarkable number of people to help and shelter him. Just as salient, though, is the abundance Reece offers those who enter his life. Little communities pop up around him like mushrooms. Working through edits and revisions with him felt like being admitted into a sacred space.

Sacredness is fundamental to the story Reece tells. After years of suffering from alcoholism and rebuilding himself in recovery, unable to find the literary recognition he longed for, and confined by self-loathing, Reece in short order found himself singled out for publication by Louise Glück and the subject of attention from publications like the New York Times—whose profile spurred him to begin working on the memoir, hoping to correct for the sense that he had worked and lived in isolation, without help or love. He then began his journey toward the priesthood. In his telling, poetry and Christianity seem inextricable, which is also the case in his writing, where his audible love of accuracy abides in an equally audible humility—a willingness to move in mystery and honor the sometimes-slow-to-manifest potential for beauty and love.

For all Reece’s patience, though, he isn’t still. Since 2004, he has published two books of poems—The Clerk’s Tale and The Road to Emmaus—and a third, Acts, is due out from Farrar, Straus and Giroux in 2024. He edited an anthology of poems from Our Little Roses Home for Girls in San Pedro Sula, Honduras, where he taught for two years, and he founded and ran the Unamuno Author Series during his years as a priest in Madrid. He now leads a church in Jackson Heights, Queens. The Secret Gospel of Mark has just been published, and All the Beauty Still Left—a collection of his watercolors combined with quotations into a small, tender book of hours—comes out next month.

We discussed his memoir through a flurry of emails over two days in January, as hatred and disease continued to flare up all around us.

INTERVIEWER

The Secret Gospel of Mark is doing a lot of things—it’s a writer’s memoir, a book of religious devotion, a record of the lives of poets you’ve cherished, a portrait of your parents’ complicated love, a story of healing into queerness and of the wounds that preceded it, a narrative of addiction and recovery, and quite a bit more—and yet it all feels unified. In the book, you describe the moment of its inception seventeen years earlier, a need to fill in a story that “talked about how I had jettisoned out of oblivion,” and a desire to recognize all the people who had shepherded you. How did you get from that original impulse to an understanding of how all these elements could work together?

REECE

I’m a slow creator—I’ve begun to think I’m on the Bishop plan, or equally the Larkin plan, of about a thing every decade, or a thing every two decades. This prose took a long arc of seventeen to eighteen years from that first impulse to what went to print. I don’t plan for this to happen—I just can’t seem to pull it all together quickly. Some inspirations come quick, surely, but the final product, no. Regarding the emotions, I’m notorious among those who know me best for not understanding something in real time, and only in hindsight can I seem to sort something out. Maybe that’s why I’ve turned to poetry, as a way to make sense of real time.

I am a poet. I walk, talk, and think like one. I think I finally accept that. I ended up writing a prose book dedicated to poetry. What “unified” it, to use your word, took a long time to see and was actually something very simple. Structure unified the book. My goal was to take all this complexity and make it a fluid read. While what I was attempting was complicated, I wanted it not to read as “complicated,” maybe like Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts. When you explain that book, it gets complicated, but it doesn’t feel that way when you read it. You flow right along with all those references. The structure of my book came when I assigned poets to periods of my life—Plath and my early life, Herbert and my first turn to faith, et cetera. The poets needed to enter the narrative organically, which meant I needed to think back to when the poets entered my life and recall what was happening then. The whole thing kind of fell into place after that, which happened about seven years ago. Then there were seven more years of editing and honing. The final chapter is a swirl of contemporary poetry, poets in real time, friends, along with the decline of my mother’s health. But only in the last year of editing did I see the figure under which these things swirled—Jesus. Thus the final chapter is called “Follow me” and concerns my past ten years as an ordained man. So it goes!

INTERVIEWER

Your prose actually reminds me of your poems. There’s an audible quality of patience, as if given enough time—say, seventeen years!—the shape of things will become apparent, and in the meantime, it’s possible to abide in mystery without loneliness. I tend to hear an element of religious faith in that way of writing, even though it goes at least as far back as your first book of poems, which you wrote when your faith was apparently less consistent and clear. Is that part of your experience, or am I just imposing that from without, as a nonbeliever?

REECE

It’s odd. Often in life, earlier life, I have had little patience with many things—falling in love, searching for an apartment, finding a job. But very little has come to me quickly. Patience came to me through waiting, through life. The first book, if I can dig back to my state of mind at the time, I really wanted published much sooner. But it kept getting turned down and passed over. That went on for fifteen years! Roughly three hundred rejections, as a poetry enthusiast once counted for me. I was humbled by that. Was it faith? Was it tenacity? Was it stubbornness? It taught me something, all those rejections. Apparently, once that book was in the world, I didn’t forget that experience. The second book of poems did not come to me for eleven years more. I will be sixty by the time my third book of poems, Acts, is bound—another ten years. Between The Road to Emmaus and Acts I have produced one anthology, been heavily involved with another, founded a literary series, helped produce a festival, been involved in a documentary about poetry, helped establish a chapbook prize for Latinx poetry, and now published this poet’s memoir in addition to my book of watercolors. It’s been a rich decade that way. There’s been joy in that, which might be close to faith, and the joy of the past decade has been sharing gifts God gave me. You are asking about faith specifically, though, and I am not answering that. I am not answering it because mainly, like writing or painting, I find it all mysterious. I find it, ironically, beyond words. No doubt this poet’s memoir must get as close to my thoughts about faith as anything I’ve ever tried to express. It was a challenge! Waiting is probably tied up in faith. I mean, the Bible is simply full of waiting, isn’t it? Everyone in there is waiting around—everyone.

INTERVIEWER

You say that you were ready to quit writing before Louise Glück picked your first book for the Bakeless Prize. Do you think you could have actually quit writing? Might you have quit sooner had it not been for the validation of people like James Merrill?

REECE

After three hundred rejections, I remember saying to myself in Florida, I would stop entering contests. If I continued to write, it would be just for me, for my own entertainment, which I suppose is a good foundation for all writing regardless of publication. I did feel beaten down, I have to say, and maybe in that thinking, I wondered what it would be like if I just stopped. I thought the contests were rigged. Or I thought you had to know somebody, and I didn’t. I thought you had to have an M.F.A. to know the people to get books published, and I didn’t have that either. The politics of getting a book into the world seemed beyond my scope completely, and so I vowed to devote myself to retail management. That’s when everything changed. Merrill had been dead ten years at that moment. I hung on to his letters and encouragement, but I wasn’t sure he cared for what I wrote. I supposed I would go down the Emily Dickinson chute. How many others have gone down that chute? Discouraged, turned away from the prize of publication and embrace? I think that’s why those thoughts felt so charged falling under the chapter about her. It is a deeply joyful art, and making the art is the goal. But my experience perhaps led to the past ten years of bringing others into the light and celebrating them, because in the end poetry is so democratic. Abandoned girls in Honduras and young Spanish students in Madrid all have access to it. You never know whose life might be changed, as mine has been.

INTERVIEWER

This book honors the people who shepherded you, but your descriptions of them are strikingly candid and often unflattering—even as they are unmistakably loving. You write that accuracy is the most important thing for you. Do you feel any tension between accuracy and love, or are those qualities essentially aligned for you?

REECE

I suppose they are aligned. If writing isn’t telling the truth, what good is it? Love according to Jesus is a commandment, not a suggestion. And love has got to grow out of some truth. Otherwise, what is it? There are many kinds of love and many kinds of truth. It’s the Keats idea that truth is beauty and that is all we need to know.

INTERVIEWER

There are so many beautiful sentences in The Secret Gospel of Mark. You write, “Hopkins’ loneliness comforts my mind.” I think that gets at one of the paradoxes of art—its ability to both render something accurately and give it a separate, even contradictory life. One of the surprises and pleasures of this book is how mobile poems become, the ways in which they echo in your experiences. I feel like we’re often taught not to do that, that we’re encouraged to keep art stationary, to see a given creation only within its own perimeters. Can you say a little about what you think poems are for—and why recording the entrance of poems and poets into your life helped you tell your story?

REECE

As the writing went on, as I kept in the forefront of my mind this impulse to honor those that had helped me, I realized that poetry had really consoled me—saved me, to risk sounding evangelical. I don’t know what others do. Listen to Janis Joplin maybe. Or long-distance running. Or who knows what. Go to church. I’ve done all those! But poetry was always the core for me. I never really understood why I was so compelled by poetry so early on. There was some kind of sound being made that connected to me. Poems are freedom. They’re invisibleness. I really understood that in Honduras when the girls started memorizing Shakespeare and Auden and everything else—that these words coming out of their mouths were charms, that they could take the memorized poems with them wherever they went. Poems are spiritual suitcases. Poems comfort in the hour of need. They have comforted me. Plath when I had such inexplicable anger. Bishop when I wondered how I would manage this world. Herbert when I began to want to know more about prayer. Merrill when I wanted to see how to be me, whatever that was. Dickinson in all those years of isolation and then beyond them. Hopkins when I decided for the second time to be a priest and still wondered if I was too outside the fold. And in the final chapter, Strand, Blanco, Pardlo, Munoz swirling together as I began to navigate life as an ordained man—what did it mean to be among contemporaries in the art as one who was following Jesus? Where would I go?

INTERVIEWER

You seem to be drawn to likeness. There are so many similes here, and they’re often playful. For instance, at one point you write, “The muddy stream and lake the campus encompassed were overpopulated with ducks and their excrement, their loose anuses going off like firecrackers.” Another sentence goes, “They took to my parents and were as decorous as airline pilots.” But the similes also seem to register other parts of your sensibility—the desire for belonging, the apparent belief that if you lay things alongside each other with enough care, they’ll show you something profound. Is play, is humor, important to you when you write?

REECE

Similes and metaphors are always multiplying in my mind. I’m not sure when or how that started. Was it seeing Humpty Dumpty, an egg turned into a bachelor with a bow tie? It probably started somewhere around there. I was a kid who lived in fantasy for years. I didn’t even understand I was doing that, and my parents didn’t discourage it—made-up people, villages, towns, maps, languages. All that spilled into poetry by high school. My father was also a very funny man, and his mother was equally funny. I think I inherited my humor from them. My grandmother was part Cherokee, everyone said, and she was a great bowler and a chain-smoker, and she drank an awful lot, and she died when I was six. She was just sixty, which seems young to me now! But I still remember that she made everyone laugh. She was subtle, sly, downtrodden in a loveless marriage, but the humor carried her. I suppose that formed a part of me.

INTERVIEWER

I wonder how all of that—but especially the first part—works with your hunger for accuracy.

REECE

Well, so much of what we see we don’t understand. The universe, for example, all the stars, what lies beyond the universe. We really know little. And with regards to one another, how much do we ever really fully know a person, even those close to us? So accuracy is often a guess. All I can say is that I ask myself a hundred times over, Is this accurate? Is this the truth? If the writing strays from that, it must go. Were the duck anuses really like firecrackers? Roger and Dan like airline pilots? Yes and yes. So maybe metaphor and simile expand the reality and possibility of things. The metaphors and similes are often about surprise—whatever is being connected is not expected—and I think surprise is what I treasure most in art.

INTERVIEWER

I have one last question. Putting aside sales and recognition and all those things, what do you hope this book might do when it heads out into the world?

REECE

I’ve never had lower expectations than I have now. Which is not to be confused with the fact that I feel a great sense of accomplishment and peace. I gave the book my all, but I honestly don’t know what to say. I know it’s the truth. It’s a gospel—which as you know breaks down to “God spell” in Anglo-Saxon. Maybe it’s cast a spell of some sort, some sort of release. The thing about making something as a writer, if you’ve done it right, is that you learn—the book has taught you something rather than the other way around. You think you are telling the book what it will be, but if you’ve done it right, it will end up telling you what it is. And now I’ll take what I’ve learned and go away for a while longer.

Jonathan Farmer is the author of That Peculiar Affirmative: On the Social Life of Poems and the editor in chief and poetry editor of At Length. He lives in Durham, North Carolina, and teaches middle and high school English.

Redux: Montaigne Was Right

Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

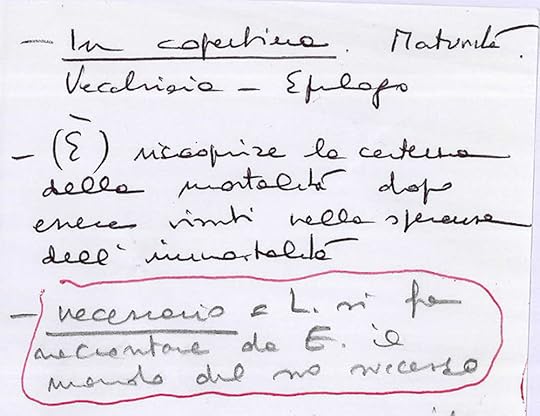

Notes from Elena Ferrante’s final revisions to The Story of the Lost Child.

This week at The Paris Review, we’re thinking about friendship, with its many complexities and joys. Read on for Elena Ferrante’s Art of Fiction interview, Ayşegül Savaş’s short story “Layover,” and Jana Prikryl’s poem “Friend.”

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, and poems, why not subscribe to The Paris Review? You’ll also get four new issues of the quarterly delivered straight to your door.

Elena Ferrante, The Art of Fiction No. 228

Issue no. 212 (Spring 2015)

The Neapolitan Novels didn’t have to make their way like the other stories in the frantumaglia. From the start I had the sensation, completely new for me, that everything was already in place. Maybe that was the result of the connection with The Lost Daughter. There, for example, the figure of Nina, the young mother who fascinates Leda, was already central.

But it seems pointless to make a list of the more or less conscious connections that I see between my books. The theme of female friendship certainly has something to do with a childhood friend of mine, whom I wrote about some time ago in the Corriere della Sera, a few years after her death. That’s the first written trace of the friendship between Lila and Elena. And then I have a small private gallery—stories, luckily, unpublished—of uncontrollable girls and women, repressed by their men, by their environment, bold and yet weary, always a step away from disappearing into their mental frantumaglia. They converge in the figure of Amalia, the mother in Troubling Love—who shares many features with Lila, if I think about it, including a lack of boundaries.

Petrona Viera (1895–1960), Friendship, date unknown, oil on fabric, 23 5/8 x 23 5/8″. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Layover

By Ayşegül Savaş

Issue no. 234 (Fall 2020)

Lara was supposed to have breakfast with Selin, a friend from middle school who had a long layover in Paris. It was eight thirty, and Lara was frustrated not to have the morning to herself before teaching in the afternoon. She loved the early, luxurious hours when she was free to do anything she wanted, which often meant making coffee and going back to bed to read.

She hadn’t seen Selin in more than fifteen years, though they’d kept in touch a little over Facebook. Selin sometimes wrote out of the blue, having remembered an episode from their school years, or to ask how Lara was doing. Lara had moved to Boston for university, then to New York, before coming to France. Selin would write that she dreamed of visiting Lara in these places.

Lara didn’t see Selin when she went back to Istanbul. Her trips were short, barely enough time to see her parents and closest friends. She had nonetheless kept track of the general shape of Selin’s life: she still lived in Istanbul; she had a boyfriend who resembled her, with a thick mop of hair and a cartoonish smile; she posted photographs of her handicrafts, which received enthusiastic comments from other crafters.

Fragment of a statue discovered in Amarna, Egypt, in a group of statues representing Akhenaten and Nefertiti. Photo: Titlutin. CC BY-SA 4.0, (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...), via Wikimedia Commons.

Friend

By Jana Prikryl

Issue no. 225 (Summer 2018)

Montaigne was right, without the body’s meddling love

is more thrilling.

Yet from the start in elementary what she did

with it was far

from irrelevant, her jeans, mascara, rings all

articulate.

And she was always so pretty. Claire Birchall of

the yellow hair,

the twins at my birthday party came out and told me

I was unfair

for playing with no one but her. I said I was sorry.

I didn’t care …

If you enjoyed the above, don’t forget to subscribe! In addition to four print issues per year, you’ll also receive complete digital access to our sixty-eight years’ worth of archives.

March 15, 2021

Imagining Nora Barnacle’s Love Letters to James Joyce

James Joyce and Nora Barnacle, seated on a wall in Zurich. Image from the UB James Joyce Collection courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, The State University of New York.

The fact is no one should be able to read the intimate words that anyone writes to their partner—those outpourings are composed for two people only: the lover and the loved. But when you’re writing a novel about Nora Barnacle and James Joyce, and the letters are published and are, well, just there, they become impossible to ignore.

Whenever I told anyone I was writing a bio-fictional novel about Nora and Joyce, they would remark, with glow-eyed glee, “Oh, no doubt you’ll include the letters.” And, yes, I have included them. But not quite as you might think.

The first challenge for me as a novelist was that the letters are still under copyright—they were first published in 1975. The second challenge was that Nora’s half of the correspondence was not available, missing—perhaps destroyed—and I had to fill those gaps with imagined letters of my own. I mimicked Joyce’s real letters as closely as I could. I wrote Nora’s part of the correspondence using Joyce’s letters as a call-and-response guide. When he praised her for using certain stimulating phrases and words, I included them in her letters to him, in the voice I had invented for her.

People often react in a jokily titillated way to Joyce’s erotic utterances, or the “dirty letters,” as they are commonly referred to in Ireland and in Joyce circles. “My love for you allows me to pray to the spirit of eternal beauty and tenderness mirrored in your eyes or to fling you down under me on that soft belly of yours and fuck you up behind, like a hog riding a sow, glorying in the open shame of your upturned dress and white girlish drawers and in the confusion of your flushed cheeks and tangled hair,” he wrote to her in 1909. Of course, Joyce was enchanted by words and used them brilliantly, and the letters reflect that. He and Nora weren’t a pair of Edwardian prisses. They were Roman Catholic, yes, and both suffered the quashing of sexuality that the clergy excelled at, but privately, many Irish people were more pagan and earthy in their customs and thought processes than they let on. Eroticism existed in early twentieth-century Ireland, and Joyce and Nora were probably not the exceptional, lusty mavericks we might consider them to be.

Joyce frequented prostitutes as a teenager, and Nora had some experience of young men by the time she met her beloved Jim; she had walked out with at least three men that she told Joyce about. Both Joyce and Nora enjoyed the erotic writings of Leopold Ritter von Sacher-Masoch, for whom masochism was named. They were two young people, proud of their bodies, in touch with their sensuality, and unafraid of sharing themselves wholly with each other.

The sensual letters that the two shared began in 1909 when Joyce, in Ireland on business, missed Nora terribly—she had remained in Trieste. He hinted to her that she might write something private to him, words that he didn’t dare write himself. Nora understood him perfectly and apparently she did write such a letter. In my version, she writes, among other things: “You think me too small and girlish, perhaps, to discipline a man. But when you get here I will order you to take off your clothes and, if you disobey me, I will sit on you and pin your arms down until you howl for forgiveness, and until your prick quivers and begs for my mercy, until I let it fuck me.”

I wonder if Joyce and Nora thought they had invented this lewd behavior—I thought I had when, as a teenager, I wrote frank letters to my boyfriend who lived about a mile away. I wonder if everyone has done this, especially now that so much of our communication happens through texts and emails. Certainly, those of us who are passionate about the power of words are often comfortable marking pages with smoldering sentences for our beloveds. When that former boyfriend emigrated, my letters were left behind—his mother told me that she had read and kept them, and I was a little appalled. Much as Joyce’s letters should not be ours to digest, I wanted to say, But they’re not yours to read or own. I didn’t, though. I didn’t say anything at all.

When researching my bio-fictional novel about Emily Dickinson, I read the erotic letters between Emily’s brother, Austin, and his mistress, Mabel Loomis Todd. The letters were direct, steamy, and quite mad in parts—for their paranoia and plotting—and I thought uncomfortably, No one on earth should be privy to these kinds of intimacies! When I first read Joyce’s letters to Nora, I was similarly gobsmacked. I recognized the frank language and the explicit, obscene imaginings. I liked, too, the intimate, tender spillover into poetic trances. But I was made wide-eyed, particularly, by his obsession with defecation as an erotic act. There are numerous references to Joyce’s love for what he calls “the most shameful and filthy act of the body.” Over and over he refers to being turned on by “shit,” “farts,” and “brown stains.” Even now, more familiar with the letters, I squirm a bit when I read this from Joyce to Nora: “The smallest things give me a great cockstand—a whorish movement of your mouth, a little brown stain on the seat of your white drawers, a sudden dirty word spluttered out by your wet lips, a sudden immodest noise made by you behind and then a bad smell slowly curling up out of your backside. At such moments I feel mad to do it in some filthy way, to feel your hot lecherous lips sucking away at me.” This was an utterly private sharing between lovers, the things they traded to bind themselves together, and Joyce’s fetish ought not bother me at all, as I shouldn’t know about it. Although, anyone who has read Molly Bloom’s wondrous speech in the Penelope episode of Ulysses might reasonably guess at Joyce’s delight in the coprophilic. When Molly wants money, she plans to let Bloom kiss her bottom, saying he can “stick his tongue 7 miles up my hole as hes there my brown part then Ill tell him I want £1.”

In Joyce’s letters, he blames Nora for making an animal of him, while begging her to write ever more impure things. He reminds her that he never uses obscene phrases in speaking. “When men tell in my presence here filthy or lecherous stories I hardly smile. Yet you seem to turn me into a beast. It was you yourself, you naughty shameless girl, who first led the way.” This was not strictly true, as the letters seem to show that he planted the seed for the correspondence himself, but Joyce never let the truth get in the way of a good story.

Stephen Joyce, grandson to James and Nora, was naturally upset at the publication of the erotic letters, particularly when a missing letter—from Joyce to Nora—emerged at a Sotheby’s auction in 2004. Stephen, Joyce’s literary executor, made it clear he would not permit the publication of the letter, calling its sale an invasion of privacy. Saying he thanked God he had no children of his own, he remarked, “Can you imagine trying to explain certain things to them? That would be a nice job, if their whole family’s private life was exposed.” When Stephen Joyce destroyed correspondence between his aunt Lucia and Samuel Beckett, he said, “I didn’t want to have greedy little eyes and greedy little fingers going over them.” And who could blame him? Few would relish the exposure of the pet names their grandfather had for their grandmother’s private parts, or hearing their beloved granny referred to as “darling brown-arsed fuckbird.”

Joyce worshipped Nora, and he wanted her to understand the wildest, worst parts of him; he wanted her collusion, while needing Nora to remain a compassionate and ever-loving spouse as well. His biographer Richard Ellmann said Joyce wanted Nora as “his queen and even his goddess; he must be able to pray to her.” The letters make all this clear—one moment he dreams of her “in filthy poses” provoking him with bawdy touches and expressions, the next he wants time to fly on quickly so he can be with her again: “I want to go back to my love, my life, my star, my little strange-eyed Ireland!”

Nora Barnacle was clearly a willing participant in the to-and-fro of the erotic letters. Her beloved Jim may have suggested the correspondence, but he didn’t need to school her. Nora knew, from their shared bed, exactly what would delight and titillate him. Once, when Joyce asked to watch her defecate and she complied, her shame meant she couldn’t look him in the eye afterward, so she may not have been as devoted to brown stains, and so on, as he was. But Nora—ever earthy and pragmatic—no doubt knew how to keep Joyce tethered to her. In my versions of her letters, Nora feeds back to Joyce some of his own sexual phrases and, crucially, is masterful with him, knowing that erotic dominance is a way to keep him bound tight to her while they are far apart. She also mentions their shared bed in Trieste, in case he forgets where he truly belongs.

We know we only have access to this most private world because we recognize the importance of every James Joyce utterance; the letters are literary artifacts as well as insights into Joyce’s sensual self. But what of Nora’s missing letters? The Joyces were wanderers—they moved house frequently and, in the war years, often suddenly. Who knows what got left behind and might yet turn up in a forgotten valise or trunk. How wonderful it would be if Nora Barnacle’s erotic letters were to be found, so that we might hear her voice and gain a penetrating insight into the woman that James Joyce loved, body, heart, and mind.

Nuala O’Connor was born in Dublin, Ireland, in 1970. A graduate of Trinity College Dublin, she is a full-time writer and lives in County Galway with her husband and three children. She has won many prizes for her fiction, including the Short Story Prize in the UK and Ireland’s Francis MacManus Award, and is an editor at the flash e-zine Splonk. Her fifth novel, Nora, was published earlier this year by Harper Perennial.

March 12, 2021

Staff Picks: Maps, Marvels, and Madmen

Charles Lloyd and the Marvels. Photo: D. Darr.

Charles Lloyd, one of the living legends from the great era of sixties jazz, has ridden a late-career high with a sort of supergroup he calls the Marvels, consisting of himself on tenor sax, Bill Frisell on guitar, Greg Leisz on steel guitar, Reuben Rogers on bass, and the wizardly Eric Harland on drums. On their first two albums, the group offered a mix of classic Lloyd originals, jazzed-up folk and rock covers, and vocal collaborations with Lucinda Williams. This group doesn’t feel like a studio band; clearly they’ve played together and enjoyed it, learned each other’s tics and tricks. So their latest record, Tone Poem, seems to catch them in medias res, doing what they do—and since everyone here is a master musician, they’re doing it damn well. The album opens with two jaunty Ornette Coleman tunes that focus on the melodic beauty of the late avant-gardist’s compositions. Next, they offer a slow, hopeful take on Leonard Cohen’s “Anthem.” Other highlights include a lush and luxurious ten-minute version of “Monk’s Mood” and a look back at “Lady Gabor,” written by Lloyd’s long-ago collaborator Gábor Szabó, a major sixties innovator in his own right whose music is too little known now. Overall, this is a mostly relaxing album, with a seamless flow of sounds, thanks to Lloyd’s smooth, continuous voice on sax, Frisell’s incredible ability to create and sustain musical textures, Leisz’s subtle steel guitar work, and Harland’s light touch. After only a few listens, Tone Poem has whispered its way deep into my consciousness. —Craig Morgan Teicher

Wendy S. Walters’s piece in the newest Ocean State Review addresses Pip, the “smallest soul of many lost ones” aboard the Pequod, with thoughtfulness and lyricism that open new doors in Melville’s masterpiece and make one want to reread it (or, rather, renew one’s eternal resolution to reread it). Not strictly essay or fiction or criticism, this is an invocation that pays mourning to Pip as written (except Ishmael, all hands on the Pequod are lost, but Pip is lost over and over again) and suggests the possibility of an alternate ending in which he “clung to some wooden box until a boat in search of its lost child finds you. But then it would be you, Pip, who represented a country’s hope for itself: a brown boy born into servitude meets the monsters and survives to tell the story. How that would change every ending.” Walters writes beautifully of the dead. In “Lonely in America,” which appears in her 2015 collection Multiply/Divide: On the American Real and Surreal, she confronts with careful grace the practical and emotional difficulty of connecting with people interred in African burial grounds in New England, whose lives are skimmed over in history books and whose grave sites are neglected or even paved over. After reading these two pieces, I look forward to digging into the rest of the collection, as well as a new piece Walters has in BOMB—and then maybe I’ll see about Melville. —Jane Breakell

The three novellas that make up Marie Vieux-Chauvet’s Love, Anger, Madness: A Haitian Triptych may differ in form, moving between first person, third person, and even a few pages of play-esque dialogue, but they all depict the brutality of life under a dictatorship modeled on that of François “Papa Doc” Duvalier. The book was originally published in France in 1968, after a period of surveillance and censorship in Vieux-Chauvet’s native country, but the English version, translated by Rose-Myriam Réjouis and Val Vinokur and featuring an introduction by Edwidge Danticat, appeared in 2009. I first encountered Vieux-Chauvet’s work via the Twitter account Women in Translation, which has been sharing an ongoing thread dedicated to promoting overlooked women writers in translation for every day of 2021. After reading Vieux-Chauvet’s Dance on the Volcano, an epic of the years leading up to the Haitian Revolution, I was hungry for more. Her prose is lyrical, and her depictions of twentieth-century Haiti’s struggles with corruption, its descent into authoritarianism, and its complexities of class, race, and gender are sharp. As Claire, the thirty-nine-year-old virgin who narrates Love, observes: “Freedom is an inmost power. That is why society limits it. In the light of day our thoughts would make monsters and madmen of us. Even those with the most limited imagination conceal something horrifying … It is a matter of will and action. Of choosing to be puppets or to be human beings.” —Rhian Sasseen

Watch jack-of-all-trades John Lurie roll tires down a hill, repeatedly crash his drone, and paint wonders with watercolors in HBO’s Painting with John. This is top-tier television. If I could suggest just one episode, let it be the fourth, “Fame Is Bad.” For saying so, I must issue a direct apology:

Dear John,

I did not comply when you demanded that I turn off your show. I almost did. I reached for the remote in that quiet tension between your demands because listening to you is so much like listening to a friend, and I forgot for an instant before you told me again to turn off your show that you were not sitting across from me in my living room. With so much virtual communication these days, who can bear to send another friend away with the push of a button? For that, I am not sorry. You followed by saying, “Or if you don’t turn it off, at least don’t tell anybody about it,” but I had already made up my mind to tell as many people as possible, and I knew then that my telling would partly take the form of an apology. The episode continued, and you had a conversation with the moon, and I realized the world desperately needed a friend like John Lurie. For even minimally contributing to your fame, I apologize. If this keeps us from becoming actual friends, I get that. If it helps in some small way to bring about a second season of Painting with John, I’ll save you a spot at the coffee table. —Christopher Notarnicola

Independent bookstores have done a truly incredible job keeping us all stocked with reading material throughout the past year, and for that we owe them an immense amount of gratitude. I’ve had no trouble staying flush in terms of new books thanks to these businesses’ efforts, and I know it’s been no small feat. Yet while my shelves have stayed full at home, there is a lot to be said for actually setting foot in a bookstore. Going in for one thing and leaving with something you didn’t know you needed. Finding something new, aided not by an algorithm but by an actual human being. Browsing. So this week, unable to head out to spend an afternoon at my local brick-and-mortar, I turn to Jorge Carrión’s Bookshops: A Reader’s History, translated from the Spanish by Peter Bush. Somewhere between a scholarly dive into the sociocultural history of bookstores and a survey of Carrión’s own travels, the book crisscrosses the globe in its exploration of the places people purchase books. What I find most endearing is Carrión’s obvious reverence for his subject matter. This guy loves bookstores! And he writes for his fellow literary patron, for anyone who has ever lost an afternoon to a well-curated selection. Carrión’s own ephemera amassed on pilgrimages to bookstores around the world serve as pins on his personal map, marking his travels throughout the narrative. And what did I find when I opened my copy of the book? A highlighter-orange bookmark from Garden District Book Shop in New Orleans, where, in the long-ago age that was 2019, I took a wonderful trip with wonderful friends and purchased this particular volume as we made our own pilgrimage to the city’s local independents. So while I continue with curbside pickup from my local and online orders from far-flung favorites, I’m reminded of time spent browsing with people I love. And I look forward to doing that again one of these days. —Mira Braneck

Jorge Carrión. Photo: Beto Gutiérrez, CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...), via Wikimedia Commons.

Cooking with Kenji Miyazawa

In Valerie Stivers’s Eat Your Words series, she cooks up recipes drawn from the works of various writers.

Photo: Erica MacLean.

Lately, when I think about jealousy or, shall I admit it, when I feel jealous, I remind myself of the story “The Earthgod and the Fox,” by the Japanese writer Kenji Miyazawa (1896–1933). When I think about politics, I consider Miyazawa’s story “The Fire Stone.” For my artistic practice, there’s “Gorsch the Cellist”; for my place in nature, “The Bears of Nametoko.” I can’t say there’s a Miyazawa story for everything—the writer died young and lived nearly a century ago in rural northern Japan—but he had stories for many of our basic human vices, and for our basic forms of goodness, too. And this only scratches the surface of his work’s appeal.

Miyazawa was born in 1896, the son of two pawnbrokers in the town of Hanamaki in the rural Iwate Prefecture. His parents were pious Buddhists and wealthy people by local standards; their son became a teacher of agricultural science and a social activist who attempted to improve the lot of farmers in his region. His poetry and fiction were not celebrated or even much published in his lifetime, but word spread posthumously, and he is now one of Japan’s foremost writers, widely taught in schools. When I decided to cook from Miyazawa’s work, I asked Tetsuro Hoshii, a Japanese acquaintance who lives in my Brooklyn neighborhood, to help me with the menu, and he revealed excitedly that he was named after a tribute to a Miyazawa novel—that’s how brightly the writer’s star continues to shine, almost a century after his death.

The jazz pianist Tetsuro Hoshii holds a gobo, or burdock root, ready to go into the “badger stew” from the story “Gorsch the Cellist.” Photo: Erica MacLean.

The stories have a timeless quality and a resemblance to fairy tales or children’s literature. Animals talk. Mushrooms play music (“tiddley tum-tum, tiddley tum-tum”). In one of my favorites, “The Earthgod and the Fox,” the title characters are both in love with “a single, beautiful, female birch tree.” The earth god is a better person, but the fox brings the tree poetry and art books and even promises her a telescope to look at the stars, and she secretly prefers him. The earth god suffers agonies of jealousy until the unexpectedly savage denouement, in which the fox, for all his airs, is revealed as a fraud. His den, vaunted to be full of books, “a microscope in one corner and the London Times lying over there, and a marble bust of Caesar here,” turns out to be “quite bare and dark, though the red clay of the floor had been trodden down hard and neat.” The pocket of his fancy suit contains “two brown burrs, the kind foxes comb their fur with.”

There are many layers to peel back from this story, but on the top level, I can’t think of a better demonstration of the difference between what we think others have when we’re envious and what they actually have.

In another favorite, “Gorsch the Cellist,” a man plays the cello “at the moving picture theater in town.” He has a reputation for being “none too good,” in fact, worse than all the other players, and he is constantly bullied because of it. He has a “great, ugly” cello and lives alone picking grubs off his tomatoes and cabbages in his spare time. Every night, he grumpily “scrub[s] away” practicing his cello. This is often how my own artistic attempts feel, including the preliminary grub picking. But one evening, a cat comes in and demands to hear Schumann. The next, a cuckoo asks to be taught a scale. The third evening, a badger cub pleads for lessons—you see, it plays the side drum, and its father said Mr. Gorsch was a nice man. Gorsch is not a nice man to any of these creatures. He torments the cat, cooperates only reluctantly with the cuckoo, and threatens to turn the badger into soup: “Badger soup, you see, is a badger just like you, boiled up with cabbage and salt for the likes of me to eat.” But grudgingly, he does help and even enjoys himself a little bit, and when he goes back to work, his playing has improved beyond all measure. As a commentary on how painfully and backwardly we improve at our work (or at least I do) and how rarely we recognize our teachers while they’re teaching us, the story is perfect.

We chopped the Napa cabbage in large chunks for the nabe pot. Chopsticks, which Hoshii brought with him, are a useful implement for prodding vegetables to determine their doneness. Photo: Erica MacLean.

The setting for all of this could seem naive, but it was not. The talking animals, human protagonists, and personified birch trees feel like folk elements that could come from any time in history, but that’s a carefully crafted illusion. The telescopes and copies of the London Times and smatterings of scientific concepts would make for strange folktales. The modern elements delineate Miyazawa’s Japan: recently opened to the West, increasingly educated, and slowly industrializing. Nature was still holding its own against man, and so were “traditional ways of life” against the modern, as the translator John Bester writes in the introduction to Once and Forever: The Tales of Kenji Miyazawa. But the future was telegraph poles and electricity, and although Miyazawa treated that future with whimsy, he did so knowingly. The whimsy, perhaps, is a serious comment on how we ought to value such things. Remember that the fox claims to have a telescope and a copy of the London Times, but when all is revealed, he’s just a fox with a couple of burrs in his pocket and a “hard and neat” floor in his den. His virtues are not the highfalutin ones he dreamed of, and his pretensions impress the girls but ultimately get him in trouble. The same could be said of humanity’s march toward progress.

I don’t think Miyazawa found modernity to be of the utmost relevance, though. His concerns were religious and profound, and his practice consisted of breathing life into the sphere of our existence, creating a space whose boundaries were the stars and far-off London, as well as a crab’s-eye view of the bottom of a creek. Everything in Miyazawa’s work seethes with life. Each leaf, flower, blade of grass, and berry seems to have its own special action. Flowers bloom “with all their might,” grasses shine “like white fire,” and shadows “flutter, flutter” on their way to the earth. “Mackerel” clouds seem “almost to be reeling with all the moonlight they’d soaked up into their bellies.” It’s a Buddhist view of things, where all creation has equal value and man is just one protagonist. This animism is perhaps best expressed in the story “The First Deer Dance,” in which a group of deer is drawn by the scent of the chestnut-and-millet dumpling a young boy has left behind, but the animals are frightened to discover an unknown white item on the ground beside it: a towel. The deer think the towel is alive and want to understand what kind of creature it is. Their dialogue about this mystery captures the joy of a world where god is in everything. And once the matter of the towel is taken care of, this is how they eat the dumpling:

“Ah, now for the dumpling!”

“Ah, a boiled dumpling ’n all!”

“Ah, ’er be quite round!”

“Ah, yum yum!”

“Ah, luvly!”

Hoshii’s nabe-pot recipe features what he calls “the winter food of northern Japan”: gobo, daikon, and mushrooms. Photo: Erica MacLean.

Again, Miyazawa is not all innocent. He is aware of cruelty, both the human kind and that of the natural world. But one senses the Buddhist detachment here, too, and an equivocation between the human predator and the animal. His villains are operating by the rules, just like everyone else. If the rule is that some people take advantage of others, that’s human nature, or nature nature—take your pick. But Miyazawa does, as in the dialogue above, celebrate the beauty and joy of existence again and again. And somehow the living freshness washes away the sin. Why cling to judgment when mountains and the stars are still breathing, when the water gives off its “phosphorescent glow”?

In this way, what start out as human tales end up as divine ones, and the reader travels from thinking about herself—her jealousy, her art, her feelings about nature and politics and industrialization—to thinking about god.

For the modern Western reader, it’s all very unfamiliar. It was this sense of distance between myself and Miyazawa’s world, as well as between myself and the traditions of Japanese cuisine, that inspired me to invite in a guest chef when cooking from his work. This summer, in the brief bubble of time when such things were possible, I’d seen a concert by the jazz pianist Tetsuro Hoshii and heard that he was also an accomplished cook. As I discovered, Hoshii, whose father is from northern Japan, has a family connection to Miyazawa. I gave him a long list of dishes and ingredients from Miyazawa’s stories, including the chestnut-and-millet dumpling from “The First Deer Dance” and a snack of “slices of salted salmon with chopped cuttlefish” eaten by the hunter in “The Bears of Nametoko.” Hoshii enlisted his father to track down the specific dish references in the original Japanese editions of the stories and came up with suggestions for how we might make versions that would be true to the spirit of northern Japanese countryside cooking while making use of the ingredients accessible to us in New York. For the “chopped cuttlefish,” he suggested a preparation of squid and daikon, since cuttlefish is unavailable, and for the badger stew, from “Gorsch the Cellist,” a preparation of lamb and vegetables cooked in a Japanese nabe pot, a rustic-style, lidded clay vessel that goes directly over the heat source. Hoshii explained that chestnut-and-millet dumplings are a dessert made with sweet rice flour, like mochi. We agreed to try those as well.

Ideally, I would have had a heat source at the table for nabe-pot cooking, as is traditional in Japan, but my gas range worked. Opening the pot at the table creates a dramatic steam effect. Photo: Erica MacLean.

One of the hallmarks of Japanese cuisine is simplicity. The squid dish, ika daikon, uses essentially two ingredients—squid and daikon—both cut into largish slabs and prepared in liquid immersions: cold water to wash the squid; boiling water to simmer the daikon for twenty minutes before shocking it and adding it to the final cooking liquid. The nabe-pot dish is also extremely simple and based on liquid immersion: you make a soup base by soaking dried kombu (kelp) in cold water for an hour, cut up the vegetables and meat (with some additional soaking), bring the cooking liquid to a boil, and then add the ingredients in a specific order. The only additional flavorings are soy sauce and ginger.

The results of this slow-paced, deliberate cooking were delicious and had the depth, clarity, and subtlety of flavor I associate with Japanese fine dining. I was again reminded of just how much “simple” food relies on technique. (When you have only a few ingredients, the creation of flavor is all technique.) Hoshii showed me how to dry-clean a burdock root with tinfoil—“you don’t want to disturb the skin”—before shaving it off with a knife directly into a bowl of cold water, where you soak it for twenty minutes before adding it to the stock. He also made a tinfoil “simmer lid” for the ika daikon, which he claimed was the best way to regulate the bubbles. Small touches like cutting the ginger for the ika daikon garnish in half-matchsticks versus grating it for the nabe pot made delicate differences in flavor. There was also the judgment and intuition factor on when to remove the kombu from the simmering liquid (when the flavor is strong enough but not too strong), how much soy sauce to add to the nabe pot (to taste, without measurements), and so on. The lazy cook might think, Couldn’t I just throw this all together and boil it? But I have tried that with a similar recipe and can attest that it doesn’t taste the same.

“If I made this dish for American people, I would put in more spices,” Hoshii said. “This is very authentic.” Instead, he relied upon small touches to create flavor and texture, like shaving the burdock root into water. Photo: Erica MacLean.

Another distinguishing feature of Japanese cuisine is an emphasis on presentation. Here, too, it was essential to have Hoshii’s eyes in the kitchen, showing me things I wouldn’t ordinarily see. I think of myself, in a vague way, as someone who tries to make her food look pretty. In practice, that means I occasionally stack things or add some garnish or present the “best side” after I’ve slopped something on a plate. Hoshii’s techniques were a new level. He arranged everything he plated. For the ika daikon, he carefully chose how many slabs of daikon to put on the plate, then arranged the squid bodies next to them. To cook everything together and then parse out the ingredients for prettier service is something I’d never thought of. I plated the nabe-pot stew for the photographs for this piece, but after we’d taken the pictures, Hoshii served us some more for our lunch, laying beautiful stacks of meat and vegetables on one side of the bowl and letting broth fill the rest, another spin on the principle of separation. Even more sophisticated, for the ika daikon he reserved half the squid bodies to go in during the last five minutes of cooking time, which gave them a color different from those that had been stewed longer; this made the dish more visually interesting.

Considering how important looks are to the final product, Hoshii and I were a little disappointed in our dumplings—there’s only so much you can do with a ball of boiled dough. For this recipe, we wrapped a dough of cooked millet and sweet rice flour around a paste of mashed chestnuts. They were chewy and only mildly sweet. Once they had cooled and dried out some, they made sense as the kind of snack a child might carry on an errand.

Millet, a grain that does not get much love in American cooking, is mentioned several times in Miyazawa’s stories. Here, it has been boiled, mashed, and mixed with sweet rice flour to form a dumpling wrapper. Photo: Erica MacLean.

The day on which we made the food was cold and sunny, without a cloud—mackerel or otherwise—in the sky. Outside my window, the man-made stretched from horizon to horizon—in one direction the skyscrapers of Lower Manhattan, in the other, across the water, the cranes on the Jersey shore. I could not imagine any of it coming to life, or talking or singing songs, and if it were to, I feared I wouldn’t like what it was saying. I did like the meal, though, and Hoshii’s generosity in helping me cook it. If Miyazawa’s spirit could be said to be anywhere in my world, it was in the steam rising off the nabe pot and the delicate flavors within.

Photo: Erica MacLean.

Ika Daikon

Recipe courtesy of Tetsuro Hoshii.

a sheet of dried kombu

4 cups of water

a pound of squid

three-inch chunk of daikon

1/4 cup sake

1/4 cup mirin

1/3 cup soy sauce

1 tsp brown sugar

ginger (for garnish)

scallion (for garnish)

Photo: Erica MacLean.

Put the dried kombu and water together in a medium saucepan, and allow to soak until the kombu expands, which should take anywhere from thirty minutes to an hour.

Wash the squid thoroughly in salted water, drain, and cut the bodies into inch-and-a-half rings. Set aside.

Slice the daikon into four thick slices, and peel. Cut crosses into the center of each slice; this will help the flavors penetrate. Fill a separate saucepan with water, put the daikon in, and bring to a boil. Turn down to a simmer, and cook until the daikon is soft when nudged with a chopstick, about twenty minutes. Drain, and blanch the daikon in cold water for three to five minutes.

To the saucepan with kombu and water, add the daikon, the sake, the mirin, the soy sauce, the brown sugar, half the squid bodies, and all of the tentacles. Bring to a boil, and then turn down to a simmer. Fashion a rough tinfoil “bowl” to put over the liquid in the pan, and use this as a “simmer lid.” Simmer for ten minutes, then remove the kombu. Simmer for twenty additional minutes, then add the rest of the squid bodies, and simmer for five minutes more.

To serve, scoop out the daikon slices and squid bodies and arrange artfully in a shallow bowl, topped with some of the liquid and garnished with small matchsticks of ginger and chopped scallion.

Photo: Erica MacLean.

Nabe-Pot “Badger Stew”

Recipe courtesy of Tetsuro Hoshii.

For this recipe, you’ll need a gas range top and a Japanese-style nabe pot, a lidded clay vessel that sits directly on an open flame.

a piece of dried kombu

3 1/2 cups water

a lamb shoulder chop (about 1/2 lb)

salt

pepper

a gobo (burdock root)

daikon (about three inches)

half a bundle of enoki mushrooms

an eighth of a head of Napa cabbage

a leek

soy sauce (to taste)

3 tbs grated ginger

Photo: Erica MacLean.

Place a sheet of dried kombu in four cups of water inside the nabe pot, and let it sit until it expands, which should take anywhere from thirty minutes to an hour.

Remove the fat from the lamb, and slice into strips as thinly as possible. Season liberally with salt and pepper, and set aside.

Clean the gobo (burdock root) by crunching up a sheet of tinfoil, wrapping it around the root, and using it to scrub. You do not want to peel the root, or get it wet, since the skin is important for the flavor. When the root is clean, shave slices off of it into a bowl of cold water, making about a cup and a half total.

Peel the daikon, slice it about a third of an inch thick, and cut into quarters.

Separate the enoki mushrooms, and cut them in half.