The Paris Review's Blog, page 120

March 29, 2021

Gary Panter’s Punk Everyman

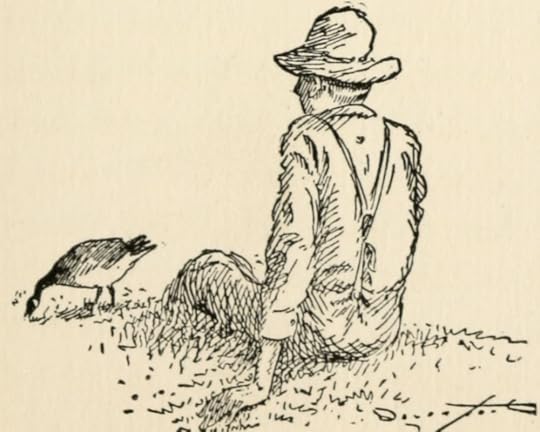

Jimbo in Despair, the drawing used as a color overlay on pages 86–87 of Gary Panter’s Jimbo: Adventures in Paradise.

The first time I drew Jimbo … I knew I’d always be drawing him. I don’t know why.

—Gary Panter

Jimbo was born in 1974, two years before Gary Panter moved from Texas to Los Angeles. He is a combination, Panter says, of his younger brother; his friend Jay Cotton; the comic-book boxing champ Joe Palooka; Dennis the Menace; and Magnus, the titular tunic-clad robot fighter in Russ Manning’s mid-century comic; as well as being influenced by Panter’s Native American heritage (his grandmother was Choctaw). Panter has called Jimbo his alter ego, and the character’s most common epithet is “punk Everyman.”

According to Panter, he didn’t set out to create Jimbo, “he just showed up.” Jimbo made his first public appearance in the punk magazine Slash in 1977 and his cover debut two years later. His pug-nosed mug moved to Françoise Mouly and Art Spiegelman’s radical art-comics anthology Raw in 1981; some of Jimbo’s stories there made up the first Raw One-Shot, a spin-off of the periodical, the following year. He joined an ensemble cast in Panter’s Cola Madnes, written in 1983 but not published until 2000, and landed his first full-length book, Jimbo: Adventures in Paradise, in 1988, published by Raw and Pantheon. Jimbo has since starred in four issues of a self-titled comic published by Zongo in the nineties and stood in for Dante in two illuminated-manuscripts-cum-comic-books: Jimbo in Purgatory (2004) and Jimbo’s Inferno (2006). He is, as you read these words, being sent out into fresh adventures by Panter’s fervid imagination and tireless pen.

Slash, August 1979, published and edited by Steve Samiof and Melanie Nissen.

Gary Brad Panter was born in Durant, Oklahoma, in 1950 (in his birth announcement, the local paper presciently misspelled his middle name as “Bard”). His family moved to Brownsville, Texas, in 1954, and then to Sulphur Springs four years later, where Panter would remain until he left for college, twenty miles away in Commerce, in 1969. In Brownsville, the family house sat across the street from a drive-in movie theater, and the glowing screen was visible from the front yard. He saw Fantasia there, and The Animal World, a 1956 documentary with an extended stop-motion animation sequence of dinosaurs fighting created by Ray Harryhausen and Willis O’Brien. At the theater in town, Panter saw his first monster movie, The Land Unknown (on a double bill with The Curse of Frankenstein, both 1957), about an expeditionary party that accidentally lands in a prehistoric jungle in Antarctica. He still recalls the primitive special effects: actors in monster suits and monitor lizards standing in for live dinosaurs. Panter’s father, an amateur painter of Western pictures, ran two dime stores, wonderlands of dinosaur figurines, toys, and comic books like Donald Duck, Mighty Mouse, and Turok, Son of Stone.

Set against the capacious Texas landscape, these first encounters with visual culture—both the shabby otherworldliness on the screen and the proliferating pop detritus of the dime store—form the bedrock of Panter’s art. It is overlaid with the Church of Christ teachings of his youth and his later break with religion, and his first encounter, almost mystical in Panter’s telling, with hippie culture:

It was the summer of 1968. We decided to drive our old station wagon from Sulphur Springs to Mount Shasta, California, to visit our cousins … [My cousin] Hotrod was in high school and he drove me around town … He drove us by where the hippies lived in town in a ranch-style home with the yard grown up three feet high and a car up on blocks in the side yard.

The [head] shop was dark and smelled like BO, incense, patchouli. Cloth was draped over tables, and the counters were draped or had stickers on the wood. There were flyers in the window. The place was small. There wasn’t a lot of merchandise. No bongs or manufactured stuff. A girl dressed like a hippie was silkscreening a version of the famous Mindbenders poster [by Wes Wilson]. And there were flutes, leatherwork, stone pipes, a hookah, ceramics, beadwork, beads in vials for sale. And a little loom. God’s eyes of yarn. Maybe four people in there being hippies. Psychedelic posters, essences, underground newspapers … It was what a hippie shack should be like. It was alien like Satyricon is alien.

At art school at East Texas State University, Panter was introduced by his professor Bruce Tibbetts to the writings of Marshall McLuhan and Burroughs, to John Cage’s Silence and Stravinsky’s notes on composition, and to the music of Frank Zappa. Robert Smithson visited the school and screened his film Spiral Jetty (1970), a portrait of the earthwork that the artist imagined transcending time and linking the earthly and celestial spheres. Panter consumed art and culture widely and freely, and the collision of disparate elements produced Dal Tokyo around 1972, a futuristic Martian city in which many of Panter’s comics are set. The name blends Dallas and Tokyo, reflecting not only the here and the elsewhere for an East Texas art-school kid but also the origin of the invented land itself: a city terraformed by Texan and Japanese workers and populated by a multitude of aliens. The influences on the creation of Dal Tokyo are legion: J. G. Ballard, Philip K. Dick, Burroughs, and Anthony Burgess; Charles Fort, Immanuel Velikovsky, and books on UFOs; Alice in Wonderland and Oz; Donald Barthelme and Gravity’s Rainbow; cowboy, monster, and Hercules movies; slot racing and Marx-brand play sets (Civil War, spacemen, Romans); modern art, hippie art, and the Sears Christmas catalog. As a “cultural and temporal collision,” according to Panter, it seems to take as a directive Smithson’s desire for “a map that would show the prehistoric world as coextensive with the world I lived in.” It is a world of near-limitless storytelling possibilities, a cultural fusion so complete that it engenders an utterly new world altogether, capacious and flexible enough to meet the unique demands of each Panter comic.

Punk hadn’t infiltrated Texas, as far as Panter knew, but his artistic efforts—in particular the Devo-esque art group Apeweek that sought to invade and pervert the media—predicted the improvisatory and rebellious spirit he’d find in the punk atmosphere in LA. Apeweek, comprising Panter and art-school friends (and later Pee-wee’s Playhouse collaborators) Jay Cotton and Ric Heitzman, made puppet shows, videos for Dallas public television, art installations, and performances in 1974 and 1975. Its imperative was “art that you could make out of a Gibson’s Discount store and use it all wrong,” Panter says. The group’s provocations paralleled those of the contemporaneous Ann Arbor art noise collective Destroy All Monsters, and helped spawn the Church of the SubGenius in North Texas, a legendary huckster cult formed in 1978 that used the language of evangelism—religious and commercial—to wage an outrageous and absurd fight against the “conspiracy of normalcy.”

Panter carried this disruptive, vernacular approach with him to LA in 1976, where he discovered a forward-looking, if not strictly punk, atmosphere. Though he found that “nobody was taking Dubuffet, Jack Kirby, and David Hockney and putting them together with Peter Saul, the Hairy Who, and Fahlstrom,” as he was, he did locate disparate models and like minds for his burgeoning brand of formal hybridization and cultural synthesis. He looked up the illustrators Cal Schenkel and Jan Van Hamersveld and visited Kirby at his house in Thousand Oaks. He became friends with Ed and Paul Ruscha after he knocked on the door of Ed’s studio on Western Avenue. He met Mike Kelley through Claude Bessy (a.k.a. Kickboy Face), an editor of Slash. Leonard Koren liked his portfolio and let him advise on an issue of Wet, the graphically adventurous magazine of “gourmet bathing” that launched in 1976. Koren later introduced him to a young cartoonist named Matt Groening, whose strip Life in Hell made its debut in Wet in 1978.

Panter wearing an Apeweek mask in Los Angeles, 1978. The masks were “about Mexican wrestling, A Clockwork Orange, primitivism.” Photo: Melanie Nissen.

It was in this period that Panter formulated the concept of Rozz-Tox. The Rozz-Tox Manifesto ran in the L.A. Reader in 1979 as a series of personal ads, but the idea for it had begun in 1976 and was an extension of drawings he had made in college. The name drew from his teacher Lee Baxter Davis’s “Pox” series of etchings and from the term rozzes, meaning “police,” in Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange. The x’s and z’s implied something futuristic to Panter, and his original notion was to think about what comes after rock ’n’ roll. “Everything dies as a fad and cultural trend,” he says, “so I imagined some kind of noisy technological modern music.” Inspired by Panter’s reading of various manifestos and accounts of modern art, Rozz-Tox evolved into a phony art movement that not only described the end of Modernism but anticipated the kind of postmodern art that would take hold in the eighties: art that took as its subject, and sometimes its medium, advertising and consumer culture, imitating it in order to critique it—the photographic appropriations of the Pictures Generation, for instance, and Jean-Michel Basquiat’s palimpsestic paintings. “Our own creations have shamed us,” Panter writes in the manifesto. “Teaching us that the hand and opinion of the individual are not as legitimate as that of opinion transmuted and inflated by broadcast … Capitalism good or ill is the river in which we sink or swim. Inspiration has always been born of recombination.”

The Rozz-Tox Manifesto also encouraged finding alternative ways to make and situate art in the capitalist world—advice that has only become more urgent over time. It warns against relying on the “aesthetic” media to point you in the direction of what is good and worthy in art and culture; the individual should follow her own instincts, her own tastes. In other words, great art doesn’t exist only in the pages of glossy magazines.

In punk’s wake came rampant fragmentation and recombination, and Panter’s manifesto, playful and exaggerated, bloomed into this sweeping “postpunk” era. Simon Reynolds’s description of the period from 1978 to 1984 also encapsulates what Panter was up to then:

[Those years] saw the systematic ransacking of twentieth-century modernist art and literature. The entire postpunk era looks like an attempt to replay virtually every major modernist theme and technique via the medium of pop music … Lyricists absorbed the radical science fiction of William S. Burroughs, J. G. Ballard, and Philip K. Dick, and techniques of collage and cut-up were transplanted into the music.

When, as Reynolds reports, John Lydon threw off the Johnny Rotten persona and formed Public Image Ltd (whose name was taken, in part, from a Muriel Spark novel) in 1978, he thought of the group not only as a band but as a “communications company,” one that would intervene in other areas of media in order to demystify the music business and reimagine what it could produce. At the same moment, in California, the Rozz-Tox Manifesto declared, “If you want better media, go make it.”

*

Panter moved to New York in 1986. Before leaving LA, he designed the sets and puppets for Paul Reubens’s Pee-wee Herman stage show. In New York, Rubens asked him to do the same for his new television show, to be broadcast on CBS. Panter’s designs for Pee-wee’s Playhouse infused the atomic aesthetic of fifties LA coffee shops with Dubuffet’s aesthetic agnosticism and the vivid, mass media–inspired British Pop art that Panter admires, in particular Eduardo Paolozzi. “We put art history all over the show,” he said. Jimbo: Adventures in Paradise contains the same kind of recombination: a collage of styles that represents Panter’s thoroughgoing absorption of visual culture. It looks and reads as though it were composed by an otherworldly visitor with the whole of human civilization (at least up to the late eighties) at her disposal.

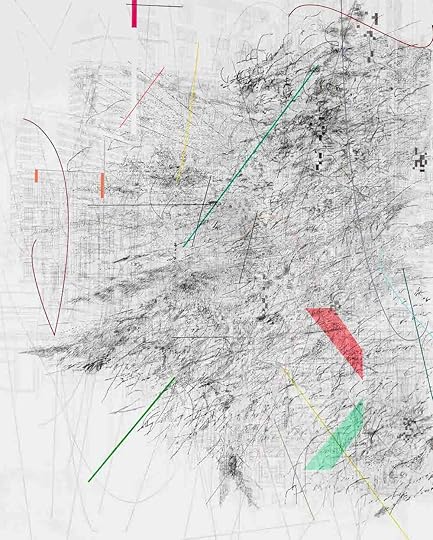

Adventures in Paradise gathered comics from Slash and Raw, together with new material and a handful of Panter’s “William and Percy” strips that ran in the L.A. Reader in the early eighties. The work was produced over a decade, from 1978 to 1988 (the majority dates from the late seventies and early eighties, and the opening and closing sections were the last to be made), but the sequences aren’t arranged chronologically. Instead, Panter organized them to create what he has described as a “rambling coherence.” The book’s mode is disjunction and unmaking—formally, in the salmagundi of page layouts and drawing styles (shifting effortlessly between Cubism, Neo-expressionism, Kirby, sixties Chicago figuration, Ukiyo-e woodcuts, and George Harriman, among others); narratively, as the story leaps, lurches (including a very funny jump cut), and finally explodes; and tonally, from punkish mischief to romance, cartoonish crime to outright atrocity.

It takes place in the near future, in Dal Tokyo, the Martian city run by corporations, and which illustrates Panter’s play-set approach: all the toys and cartoon characters, punks, weirdos, and aliens set in motion in one huge sandbox. He titled the book Jimbo: Adventures in Paradise, though he hadn’t yet read Dante and the book has nothing to do with the Paradiso. (Still, Dante’s celestial theology is arguably no less a radical science-fiction vision of the vast smallness of the universe than Panter’s sociocultural stew bubbling on Mars.) Of his very early career, Panter said, “in some ways you accept your vision or you don’t, and I keep having more and more visions and just moving to the next one to see how far I could go.” It’s an apt description of Adventures in Paradise, too.

The book begins with a soliloquy by Jimbo as he makes his way through the city to a neighborhood Feedomat, a fast-food joint in which orders are transmitted to robots by thought (it’s peak surveillance capitalism):

Have you ever had a dream where you knew you were dreaming, but it was so real that you didn’t trust your judgement? And you thought “Well, maybe it did get this bad, but it got bad so fast and so different!” So then you thought “Nah! It’s just a dream. Things aren’t this bad yet!” When suddenly, it all seemed feasible again … And so boring and normal—convincing—like any other day.

The slippage between dream, nightmare, and reality is a hallmark of Adventures in Paradise, which rambles, and sometimes veers, among different states of reality, some to be believed and others not. It is antic and outrageous, a convocation of childhood wonders that might convince us that “dreams are toys,” as Antigonus reasons in The Winter’s Tale. Jimbo, despite his punk lineage, is no nihilist, no anarchist. He has more in common with a small-town Texas boy gazing rapt at the glowing screen of a drive-in; he is an empathetic and enthusiastic observer, like his creator. “I never jumped in the mosh pit,” Panter says. “I stood in the back, or on the sides, or even backstage, observing.” When Jimbo goes to a show at the beginning of the book, he complains about the fashion—the rubber pants are too tight and he can’t afford the fake scars that everyone wears. And Panter draws him just at the edge of the crowded pit, remarking on, but not joining, the fray. By book’s end, however, the dream does offend. Panter depicts a reality so nightmarish it couldn’t possibly be true, but is.

An ad in the Village Voice, 1988. Only one person showed up for the signing.

Jimbo’s adventure takes him from his mansion high on a green hill, “gigantic but condemned” (a lapsed Eden, not so far from Paradiso after all), to a crowded, kaleidoscopic music show–turned–riot that unravels in hallucinogenic wonder when he drops acid. Rifts tear at the panels and page gutters, nebulous forms that reproduce the way shapes dissolve into one another during an acid trip, but portals, too, opening to parallel planes of existence. He meets Smoggo, the smog monster, and falls in love with his unflappable sister, Judy, the unsung hero of the book who, when she is kidnapped by cockroaches, declares, “Jimbo, it won’t break my heart if I have to save myself!” (She does, too.) Meanwhile, King Ducko and his cockroach lackeys want the plans to the Radioactive Planetoid Burger Bar Corp.—or else. Laced within this main story are strange interludes, starring Rat Boy, Nancy and Sluggo, and Jimbo Erectus, as well as a (self-)critical fable about the United States’ exploitation and debasement of Native Americans.

The book coheres because it doesn’t try to. It runs on artistic adrenaline, unalloyed energy, and the joy of drawing. Its ruptures and tangents embody the social upheaval of the late seventies and eighties, and Adventures in Paradise, perhaps more than any other comic by Panter (or by anyone, for that matter), inextricably links avant-garde and popular culture into a single work full of feeling and ideas. It runs hot like a punk song and yet its hero is a sensitive hippie. “It was rude and so weird and not readable—all of the things that made comics narratively legible are part of the sabotage that is Jimbo,” Spiegelman recalls of the comic’s reception among general readers. For all the book’s fragmentation, Jimbo is fully alive as a character. As Smoggo tells him, “You’re litrature, buddy.”

In 2014, writing about his memory of visiting the hippie shack in California, Panter recalled the aura of activity in the place. This “evidence of doing,” as he calls it, links the process of making to the body itself. In thinking about that experience, he observes that H. C. Westermann’s work “radiates powerful vibes of having been intensely touched, refined.” He comments, too, on “the ears of Peter Saul’s mind, the hand craft of Nutt, and Wirsum.” Markmaking (or objectmaking) is, for Panter, a process that conjoins knowledge or emotion and physicality. “Drawing is a way of controlling your world if you can control your hand,” he has said. His love for movies in which special effects are visibly human-made finds expression in his unpolished, ratty line—his distinctive drawing style that evidences its own handmade-ness.

In Adventures in Paradise, he dedicates a story from 1979 to “the Guardians of the Ratty Line, who are Bringing it to its proper place in society”—among them, Matt Groening, Edwin Pouncey (a.k.a. Savage Pencil), Cal Schenkel, and Jeffrey Vallance. The camaraderie reminds me of Bernard Sumner’s first impression of the Sex Pistols: “I saw the Sex Pistols. They were terrible. I thought they were great. I wanted to get up and be terrible too.” Looking back on Raw’s publication of Panter’s Jimbo comics, Spiegelman has said: “There’s a separate moment in comics’ trajectory that indicates some new sensibility coming in. Gary was the clearest version of what that might be, as separate from what I’d known up to that point in underground comix.” Mouly saw in the work a “sense of what could be happening now and could be the future of comics.” Panter, always looking to see what comes next, had created the next thing.

*

At the end of the Adventures in Paradise, Jimbo must disarm an atomic bomb; he fails. The story overloads, narratively and visually, in one of the most masterfully drawn sequences of the medium. Panter composes each page in a different style, forms dematerializing and recombining in a new state, atoms rearranging. He studied books on Hiroshima and Nagasaki and modeled the comic’s backgrounds on what he read. He has described the ending as a “histrionic but heartfelt” meditation on the bombings of Japan as well as an attempt to address that “unsettled debt.” The nuclear threat was present as he drew those pages, too: in 1979, only a few years before he composed the atomic sequences, the Three Mile Island facility, in Pennsylvania, melted down. In a strip earlier in the book, drawn contemporaneously with the meltdown, Panter adds a winking aside to the reader: “No patriotic American would be mad if you, our society’s vandals, threw a brick through your nearest corporation that invests heavily in nuclear power.”

The cubist shards, moody ink washes, and spectacular arrays of breathless line work describe a puncture in time, a fragmented moment in which the present seems to leap forward in an instant. This existential doom is somehow elegant, as when Smithson, flying above his Spiral Jetty suspended in the Great Salt Lake, observes,

The flaming reflection suggested the ion source of a cyclotron that extended into a spiral of collapsed matter. All sense of energy acceleration expired into a rippling stillness of reflected heat. A withering light swallowed the rocky particles of the spiral, as the helicopter gained altitude. All existence seemed tentative and stagnant. The sounds of the helicopter motor became a primal groan echoing into tenuous aerial views. Was I but a shadow in a plastic bubble hovering in a place outside mind and body?

Panter’s pen dips into horror after horror, before alighting on the burned horse. Why a horse? His father, Panter once recalled, was “sentimental about horses and dogs and hates Western novels where the horse get killed. If anything bad happens to a horse in the story he’ll throw the book down.” The destruction of a horse was perhaps the best representation of barbarity Panter could think of. That final image, still and terrible: it evokes the obliterating silence that Dick describes in the novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, “the lungless, all-penetrating, masterful world-silence.”

When Panter met Dick in LA in 1980, they exchanged stories about personal visions and the confusion that surrounded those visions. Panter told Dick about a bad trip he’d had in college, simultaneously foreboding and retrograde:

The pictures were coming at me ten thousand a second, and they were all relative, personal and manufactured. A lot of them were in the style of my art and most of them were wrong. They also seemed to be predictive, and I felt like a lot of what happened in my acid trip was like an echo of what I might experience later. As if giant trauma memories from the future would be impressed upon me as well as the past.

The time warp in Panter’s bad-trip hallucination—of the past pressing forward and the future echoing backward, both converging on the fleeting present—is a counterpart to Walter Benjamin’s terrifying vision of the angel of history:

His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But the storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. This storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.

Both visions come to pass in the final image of Adventures in Paradise, in Jimbo—his horrible deed at an end, his head tilted back and away from the mangled body of the horse, the day done. Smoggo calls him “an unlikely custodian for a living nuclear nightmare.” Jimbo would have liked to repaired things but found the task impossible. He has been moving toward this moment from the first pages of the book, from a capitalist paradise, to the world in ruins, and then to whatever comes next.

Nicole Rudick is a critic and an editor. She has written widely on art, literature, and comics for The New York Review of Books, the New York Times, The New Yorker, Artforum, the Poetry Foundation, and elsewhere. She was managing editor of The Paris Review for nearly a decade and edited two issues of the magazine as well as The Writer’s Chapbook: A Compendium of Fact, Opinion, Wit, and Advice from “The Paris Review” Interviews.

Excerpted from Jimbo: Adventures in Paradise , by Gary Panter , published this week by New York Review Comics . Copyright © 2021 by Nicole Rudick, courtesy of New York Review Comics.

March 26, 2021

Staff Picks: Language, Liberation, and LaserJet

Rachel Sennott in Shiva Baby. Photo: Maria Rusche. Courtesy of Utopia.

The writer and director Emma Seligman is in good company. Like the breakout features of auteurs such as Wes Anderson, Ana Lily Amirpour, and Damien Chazelle, Seligman’s feature-length debut, Shiva Baby, evolved from a short film of the same name. The story centers on the near–college graduate Danielle (Rachel Sennott), who struggles to keep her composure when her ex-girlfriend and her sugar daddy turn up at a family shiva. The title does a lot of work in forecasting the mood of the film, mixing sugar baby, or one who works as a companion for an older client, with shiva, the Jewish period of mourning. The tension between the two terms manifests in Danielle, literally and figuratively lost between bassinet and casket, no longer a defenseless child but not quite an independent woman, swirling in the awkward overlap of what were previously distinct and separate social circles. The film’s genre matches this duality, with more cringe and quips than most comedies but dizzying visuals and a nervy score fit for horror, straddling the humorous nuance of Gillian Robespierre’s Obvious Child and the familial psychodrama of Trey Edward Shults’s Krisha, both of which also began as shorts. But if you’re not interested in form, then show up for the cast. Polly Draper is a standout as Danielle’s mother, Dianna Agron is tension incarnate, and Sennott makes good on the promise of her Twitter bio: “sexy in a weird unconventional dreary way.” —Christopher Notarnicola

Gjertrud Schnackenberg’s poem “Strike into It Unasked,” which appears in the Spring issue, opens with a LaserJet printer and moves into the realms of physics and faith. Similarly, “Venus Velvet No. 2,” one of the six long poems that make up her 2010 collection, Heavenly Questions, begins with a pencil and its “vein of graphite ore preoccupied / In microcrystalline eternity.” But it would be wrong to say Schnackenberg’s work is just an experience of finding the divine in the mundane. Her verse is formally considered and lush, musical prosody rendered in mystical and expansive language. Heavenly Questions is a slim volume to be read with the window thrown open on a bright spring afternoon, an encounter with possibility, the passage of time, and a poignancy that both settles and troubles the mind. —Lauren Kane

Garielle Lutz. Photo courtesy of Short Flight / Long Drive Books.

In the title story of Garielle Lutz’s new collection Worsted, forthcoming from Short Flight / Long Drive Books, language itself has become deeply suspect. This would not be quite so notable, I suppose, if Lutz weren’t known for her incredible use of English. Lutz’s work is a marvel of the possibilities of language. Each of her sentences is an intricately crafted thing, deeply complex yet crystalline in its clarity; because of the technical nature of her writing, some consider her to be the only untranslatable American writer. “Worsted,” however, is partially a story of language’s failures. As soon as “something gets itself described,” it becomes useless. The letters of the alphabet are “tragedies.” The narrator even points to his own potential to be read incorrectly: “People will naturally want to have misread that adverb,” he says. “No grudge will be held.” But while language has failed the narrator in the opening pages of Worsted, Lutz has once again found stunning success in its possibilities. Even as Lutz writes of a man for whom language is nothing but a tragedy, her command of each and every word remains supreme. —Mira Braneck

The experimental filmmaker Ephraim Asili’s debut feature, The Inheritance, is a fascinating exploration of the history of radical Black intellectual thought and art that takes Godard’s La Chinoise as inspiration, remixing and filtering it through the lives of a group of young West Philadelphia activists and artists. The film begins with Julian, who has just inherited a house, along with a collection of books and records, from his grandmother. His girlfriend, Gwen, suggests that he turn the house into a collective. Based on Asili’s own time spent living in a Black liberationist group, what follows is a collage of the daily lives of the collective’s members (staging plays, discussing their backgrounds, occasionally having gently comedic arguments about wearing shoes in the house or playing the trumpet in the bathroom) interwoven with video clips of and readings from the figures with whose work they are interacting (early on, there’s an electrifying clip of Shirley Chisholm at a political rally; later, Sonia Sanchez reads one of her poems). Halfway through the film, Asili includes a series of sobering testimonials from three present-day members of MOVE, the Philadelphia liberation group that was the target of a police bombing in 1985. Like La Chinoise, The Inheritance is visually stunning, with a bright palette of primary colors illuminating its scenes. But while Godard’s film veers into criticism of its radical-chic university students, Asili’s is optimistic in its exploration of the possibility of cultural inheritance. —Rhian Sasseen

It is said that old Shetland fishermen, finding themselves bereft of a nautical almanac, might still find their way home by the undercurrent that always travels in the direction of land. It is for this current that Roseanne Watt’s unique 2019 debut, Moder Dy—“mother wave”—is named. The collection is written in both English and Shaetlan, the local vernacular of the Shetland Islands. Watt describes Shaetlan as “a form of Scots shaped by sea roads” and “a fraught coalition between English, Lowland Scots, and old Norse.” That tension manifests in the poems themselves, and there is an uneasy reconciliation of different elements of home, of linguistic inheritance, and of time and generations. In the introduction, Watt recounts how her languages bifurcated around the time she started school, how the moment of realization came when she was on the phone with her grandmother: “And with this, a choice seemed to present itself: which one?” Moder Dy would suggest that Watt has rejected that binary and instead choreographed the two languages to more accurately reflect her own contemporary experience. But while time and tradition relent for Watt, they perhaps do not for others. From an elder we hear “de saat dat coorses trowe / dy veins is de lifeblöd / o an aulder converseeshun” (in one of Watt’s “uneasy translations,” that is rendered as “the salt that courses / through your veins is the lifeblood / of an older conversation”). It’s an incredible work of poetics, social history, and translation, and it all seems to be happening before our eyes. —Robin Jones

Roseanne Watt. Photo courtesy of Birlinn Limited.

Lee Krasner’s Elegant Destructions

Lee Krasner, one of the most phenomenally gifted painters of the twentieth century, often would create through destruction. She had a habit of stripping previous works for materials—fractions of forgotten sketches, swaths of unused paper, scraps of canvas from her own paintings as well as those of her husband, Jackson Pollock—that she would then reconstitute as elements of her masterful, distinctive collages. A new show devoted to her endeavors in this mode, “Lee Krasner: Collage Paintings 1938–1981,” will be on view at Kasmin Gallery through April 24. A selection of images from the exhibition appears below.

Lee Krasner, Stretched Yellow, 1955, oil with paper on canvas, 82 1/2 x 57 3/4″. © 2021 Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Collection of Carolyn Campagna Kleefeld Contemporary Art Museum of California State University, Long Beach. Gift of the Gordon F. Hampton Foundation, through Wesley G. Hampton, Roger K. Hampton, and Katharine H. Shenk. Courtesy of Kasmin Gallery.

Lee Krasner, The Farthest Point, 1981, oil and paper collage on canvas, 56 3/4 x 37 1/4″. © 2021 Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy of Kasmin Gallery.

Lee Krasner, Imperfect Indicative, 1976, collage on canvas, 78 x 72″. © 2021 Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy of Kasmin Gallery.

Lee Krasner, Seated Figure, 1938–1939, oil and collage on linen, 25 x 18″. © 2021 Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy of Kasmin Gallery.

Lee Krasner, Untitled, 1954, oil, glue, canvas, and paper collage on Masonite, 48 x 40″. © 2021 Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Private collection, New York City. Courtesy of Kasmin Gallery.

View of “Lee Krasner: Collage Paintings 1938–1981,” 2021, Kasmin Gallery, New York. Photo: Diego Flores.

“Lee Krasner: Collage Paintings 1938–1981” will be on view at Kasmin Gallery through April 24.

March 25, 2021

A Taxonomy of Country Boys

Cartoon by Homer Davenport from The Country Boy, 1910. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

To be or not to be a country boy? To my ear, this has always been one of the animating questions in country music. In “Thank God I’m a Country Boy” (1974), John Denver, for instance, revels in the persona. From the picture he sketches, it’s not hard to see why. Country boys, Denver says, have all they need: a warm bed, good work, regular meals, fiddle music. The life of a country boy, he sings, “ain’t nothing but a funny, funny riddle,” and who doesn’t like a good laugh?

For Hank Williams Jr., however, this country boy business isn’t something to joke about. In “A Country Boy Can Survive” (1981), he says the rivers are drying up and the stock market is anybody’s guess and the world, as a general rule, is going to hell and if you knew what was good for you, you’d be a country boy, too, because in the end only country boys—the ones “raised on shotguns,” the ones who know “how to skin a buck” and “plow a field all day long”—will make it out alive.

Loretta Lynn could do without Hank Jr.’s heated rhetoric, but as she sings in “You’re Lookin’ at Country” (1971), “this country girl would walk a country mile / to find her a good ole slow-talking country boy.” Then, so as to underline her preference, she repeats, “I said a country boy.” Not just any country boy will do. Drawl aside, Loretta makes plain she wants a workhorse with a worn shovel who, in exchange for a tour around the farm, will “show me a wedding band.”

It’s doubtful Lynn’s narrator would have gone for the type Johnny Cash sings about on his first album, Johnny Cash with His Hot and Blue Guitar!—not that Cash’s country boy would care. He has “no ills,” “no bills,” “no shoes,” “no blues.” A country boy’s greatest privilege, Cash’s “Country Boy” (1957) suggests, is his ignorance of the finer things. In part, he’s happy with his “shaggy dog,” fried fish, and “morning dew” because he hasn’t been exposed to much besides.

Having little, Cash says, country boys have “a lot to lose.” Cash, who by this stage in his life had traded Arkansas fields for a Memphis recording studio, spends a lot of time wishing he could get back to being a country boy, but his hot-and-blue guitar says otherwise. The truth is you couldn’t go back if you wanted to, but would you go back even if you could?

It’s when country boys leave the country, or are made aware of other ways of living, that problems arise. They either get nostalgic (Cash) or defensive (Hank Jr.), or they come down, in the case of Glen Campbell’s “Country Boy (You Got Your Feet in L.A.)” (1975), with a bad case of impostor syndrome.

In the first song on his album Rhinestone Cowboy, Campbell sings about a country boy who has hit the big time:

You get a house in the hills

You’re paying everyone’s bills

And they tell you that

You’re gonna go far

But in the back of my mind

I hear it time after time,

Is that who you really are?

Having lived for so long on so much less—“I can remember the time,” he sings, “when I sang my songs for free”—this country boy can’t enjoy his change of fortune. His modest beginnings are both a grace and a liability. On the one hand, they keep him from getting carried away. On the other, they prevent him from being fully present. To do so, he fears, would be a self-betrayal. In the end, he realizes that he’s going to have to choose. A country boy in Hollywood won’t stay so for long.

What about a country boy in finance? In the video for Ricky Skaggs’s 1985 hit “Country Boy,” the bluegrass legend Bill Monroe accuses Skaggs of losing his bearings. The scene takes place in a Manhattan office building, where Skaggs sits behind a big desk in a business suit. Buzzed in by Skaggs’s secretary, Monroe looks around. “I heard it was bad, boy, but I didn’t know you’d sink to this,” he says, at which point Skaggs whips out his guitar and tries to prove him wrong.

Monroe’s disapproving presence turns Skaggs’s foot stomper into a précis on Nashville’s shifting sensibilities in the eighties. Skaggs had come up under Monroe’s tutelage. He first played mandolin with Monroe’s band when he was six years old. In his teens and twenties he had toured with the Stanley Brothers and the Country Gentlemen, more bluegrass royalty. With his high-lonesome voice and confident grasp of the bluegrass canon, Skaggs had often been regarded as the future of the genre, which is to say a faithful steward of its past. Now he was making mainstream country. Had he sold out?

You can take the boy out of the country but not the country out of the boy—that’s what Skaggs contends. Despite ills and bills and all the rest of it, not to mention a streak of No. 1 records, a country boy is a country boy once and for all. He might work in a bank instead of a coal mine and live in a walk-up instead of a cabin in the woods, but deep down, he’s still a “cotton picker,” still a “hog caller chewing cud on the stile.” Monroe isn’t convinced. He shakes his head in disgust. “I’m just a country boy,” Skaggs counters, over and over, “country boy at heart.”

“Just a country boy.” For Skaggs, the words are a pledge of allegiance. For Don Williams, however, they’re a convenient excuse. In “I’m Just a Country Boy,” a song first recorded by Harry Belafonte and which Williams took to No. 1 on the country charts in 1977, the meagerness wrapped up in the word “just” has real-world consequences.

Williams’s country boy won’t be marrying the woman he loves because he can’t afford her. He can’t afford much of anything. He might have, as the chorus says, “silver in the stars” and “gold in the morning sun,” but they don’t take sunshine at the jeweler’s. And yet the “justness” of being a country boy resigns him to his letdown. The song is less a dirge than a shoulder shrug. “I’m just a country boy,” Williams sings, as if to say, What did you expect?

Even so, resignation has its own complexity. That’s the theme of another Williams song, the somber “Good Ole Boys Like Me” (1979), which might as well be called “I’m Still Just a Country Boy.” In that song, which was written by Bob McDill, the narrator looks back on a childhood full of sensually overwhelming contradictions and tries to reckon with his place in the world. In a chapter about Nashville from his travelogue A Turn in the South, V. S. Naipaul describes McDill’s achievement as a kind of magic composed of “the calling up and recognition of impulses that on the surface were simple, but which, put together with music, made rich with a chorus, seemed to catch undefined places in the heart and memory.”

The narrator of “Good Ole Boys Like Me” recalls his gin-drunk father reading him the Bible at bedtime, lecturing him “about honor and things I should know,” then staggering “a little as he went out the door.” In the chorus, he declares his allegiance to Hank and Tennessee Williams, one a honky-tonk hero who forever exploded the boundaries of country music, the other a playwriting shake-scene who left Mississippi for New York and European cities and never stopped writing about displaced country people.

The country boy remembers falling asleep to the sounds of John R., a Nashville DJ who played rhythm and blues, and to the words of Thomas Wolfe “whispering in my head.” Wolfe’s two most famous novels, the autobiographical Look Homeward, Angel and the equally autobiographical You Can’t Go Home Again, tell the story of a country boy’s struggle to leave and return to the South. Don Williams’s country boy has taken Wolfe’s cue.

Unsettled by the death of a friend from substance abuse and, we might infer, by the fear of becoming a sentimental drunk like his old man, the country boy has “hit the road,” and in more ways than one. He admits, in the final verse, that he has purposefully moderated his Southern accent to sound like “the man on the six o’clock news.” Maybe he’s not a country boy at all. Maybe he never was one to begin with. “I was smarter than most,” he says, “and I could choose.”

Still, that he can recall these experiences and artifacts with such precision reveals how inured of them he remains. So much so that in the end, his statement about freedom of choice has been allayed by a kind of fatalism. “I guess,” he concludes, “we’re all gonna be what we’re gonna be / so what do you do with good ole boys like me?”

I’m not sure how to take that question. Which way is it aimed? Is the “you” a world that no longer has much use for country boys? Or is the “you” the country boys who couldn’t care less about their own relevance and so regard this narrator with suspicion? Don Williams’s country boy is some combination of Skaggs’s and Hank Jr.’s varieties. He’s survived, all right, but in spite of his upbringing, not because of it, and what would it mean if in the end it turned out he wasn’t a country boy, not even at heart?

“Good Ole Boys Like Me” has always reminded me of a painting by Marc Chagall called I and the Village, a framed poster of which hung on a wall in my Tennessee elementary school. Chagall completed I and the Village when he was in his midtwenties. He had traveled from Belarus to Paris and back. The painting, a spectacular of rapt disorientation, describes the churn.

In it, scenes from Vitsyebsk, the town where Chagall grew up, wheel around a polychromatic dreamscape. The characters are earthy, low down, and yet the picture radiates a kind of weightlessness. A man with a green face and white eyes holds a little tree of life. There’s a woman milking a goat on a cow’s cheek. In the background, a woman in blue skirts stands on her head, a kind of yin to the yang of a peasant shouldering a scythe.

I and the Village projects a cockeyed vision of village life. Later, Chagall would write in his memoir, My Life, that the flying figures and transmogrifying vistas that characterized his early breakthroughs had come in response to a desire, expressed in desperate prayers while walking the streets of Paris, to “see a new world.”

In the third or fourth grade, I would not have had the vocabulary to articulate such thoughts, but I think I sensed, as I walked by I and the Village en route to class or hovered in front of it while waiting in line to go to the gym or restroom, something of Chagall’s fraught relationship with his roots.

There was adoration in the Chagall, and there was also revulsion, nearness and distance, the red and the green. The artist loved this place and these people even though, as I suspected, he wasn’t one of them. His village wasn’t Vitsyebsk; his village was the canvas. Likewise, Don Williams’s “good ole boy,” out of place in the country and the city alike, finds comfort, if nowhere else, in the country song, which for all of its parochialism never comes off as provincial.

It’s telling, if not surprising, that the chorus of “Good Ole Boys Like Me” commends, out of all the country singers in the canon, Hank Williams Sr., Hank Jr.’s dad. Ol’ Hank, to my knowledge, didn’t write any songs called “Country Boy.” What he did write, unforgettably, was “Ramblin’ Man” (1953), a minor-key manifesto, delivered in a brazen blue yodel, about the allure of the open road, a place he calls in another song “the lost highway.”

What is a rambling man? A country boy gone rogue. As much as he sees the good in a simple, even simplistic way of life, a rambling man values his freedom more. He’s a flight risk. In love and work, he’s liable to unlatch at any moment, not caring who he works up or lets down in the process. Ashley Monroe, a country singer who has taken up the rambler mantle, describes the calculus in her song “I’m Good at Leavin’ ” (2015):

A couple times I said I do

A couple times I said we’re through

I never really seem to get what I was needing

I’m good at packing up my car

I’m good at honky-tonks and bars

Waylon Jennings, in his 1974 cover of Ray Pennington’s Hank-inspired “I’m a Ramblin’ Man,” puts it more bluntly: “You’d better move away / You’re standin’ too close to the flame.”

More than a personal liability, though, Hank’s rambling man is also something of a jongleur. Hank recorded “Ramblin’ Man” under the auspices of his alter ego, Luke the Drifter. The songs Hank recorded as Luke tend to deliver morality tales. Luke is a kind of itinerant preacher, a wandering prophet whose home church seems to consist solely of Hank Williams, whose own songs, reflective of his life, were often about carousing, heavy drinking, and existential despair.

Instead of Dr. Jekyll to the country boy’s Mr. Hyde, Hank’s rambling man is a wiser, more bruised iteration of himself. He seems older than Hank, at once more frightening and more reasonable, cut off from society and yet drawing from a deeper source. He hasn’t abdicated responsibility so much as secured the necessary distance to appraise experience and report back. Rambling, in this sense, is the process by which a country boy becomes a man.

“Ramblin’ Man” was never released as a single. The song was the B side to “Take These Chains from My Heart,” a honky-tonk ballad that went to No. 1 following Hank’s death, at age twenty-nine, on New Year’s Day 1953. Hank’s passing translated “Ramblin’ Man” into a last will and testament. “And when I’m gone,” he sings,

And at my grave you stand

Just say God’s called home

Your ramblin’ man

Like John Denver, Ol’ Hank invokes the Almighty. “Let me travel this land,” he prays,

From the mountains to the sea

’Cause that’s the life I believe

He meant for me

One thanks his stars he’s a country boy. The other thanks his he isn’t only that. The question, in other words, is not whether or not to be a country boy. The question is, What kind of country boy are you going to be?

Drew Bratcher was born in Nashville. He received his M.F.A. from the University of Iowa. He lives in Chicagoland.

March 24, 2021

Redux: The Clock Is Ticking

Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

Antonella Anedda. Photo courtesy of Antonella Anedda Angioy.

This week at The Paris Review, we’re celebrating the return of spring. Read on for Antonella Anedda’s Art of Poetry interview, Souvankham Thammavongsa’s short story “The Gas Station,” and Diane di Prima’s poem “Song for Spring Equinox.”

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, and poems, why not subscribe to The Paris Review? You’ll also get four new issues of the quarterly delivered straight to your door.

Antonella Anedda, The Art of Poetry No. 109

Issue no. 234 (Fall 2020)

INTERVIEWER

What is your earliest memory of poetry?

ANTONELLA ANEDDA

The first poem I ever heard was by Aleksandr Blok, on the radio in a small village in Sardinia. It’s an early work that begins, “Carried on the breeze, / the Spring’s music drifted from far, far away.” The poem was about space and wind—how the wind breaks open the clouds to reveal a strip of blue sky.

Photo: W.carter. CC0, via Wikimedia Commons.

The Gas Station

By Souvankham Thammavongsa

Issue no. 228 (Spring 2019)

The gas station was on the edge of town, before you hit the interstate. It was bright green like a tennis ball. Easily spotted from miles away. This was where he worked. The gas station man. He came out to pump the gas. He was not beautiful, but she liked looking at him. Grotesque seemed right to describe him. It was not yet spring. The white sand in the town still glimmered. The ocean still swelled, wave after wave crashed into shore. There was a chill in the air, but he was shirtless. He had hair all over his chest. Like pubic hair. Messy and wet and shining. It was inappropriate to walk around like that.

Abraham Brueghel, Allegory of Spring, ca. 1680, oil on canvas, 38 1/2 x 53 1/4″. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Song for Spring Equinox

By Diane di Prima

Issue no. 44 (Fall 1968)

It is the first day of spring, the children are singing

(they are supposed to be sleeping) the clock is ticking

the cats are waiting for supper, one of them pregnant

kittens to herald the spring, nothing is blooming

nothing seems to bloom much around farms, just hayfields and corn

farms are too pragmatic, I look at ads

for hydrangea bushes, which I hate they remind me of brooklyn …

If you enjoyed the above, don’t forget to subscribe! In addition to four print issues per year, you’ll also receive complete digital access to our sixty-eight years’ worth of archives.

The B Side of War: An Interview with Agustín Fernández Mallo

Agustín Fernández Mallo. Photo: Aina Lorente Solivellas.

By “injecting the novel with a large dose of Robert Smithson, and Situationism, and Dadaism, and poetry, and science, and appropriation (collage and quotes and cut-and-paste), and technology (often anachronistic), and images (almost always pixelated), and comic books,” as Jorge Carrión has written, and perhaps above all because he simply presented compelling new possibilities for the form, Agustín Fernández Mallo is considered to have revolutionized the Spanish novel.

Mallo was born in Galicia in 1967 and started working as a radiation physicist in 1992, designing X-ray systems and developing cancer-radiation therapies. Nocilla Dream, his debut novel, took the Spanish literary scene by storm in 2006, and bears all the hallmarks of his output since—an interest in form, a desire to highlight the connections between art and science, and an attempt to put his self-styled “post-poetry” into practice.

The following conversation, translated from the Spanish by Thomas Bunstead, was organized by Fitzcarraldo Editions ahead of its publication of Mallo’s The Things We’ve Seen, also translated by Bunstead. The book, his fourth to appear in English, is out this week in the UK and will be released in the U.S. on June 15. Originally published in Spanish by Seix Barral as Trilogía de la Guerra in 2018, it won the prestigious Biblioteca Breve Prize.

INTERVIEWER

Does any one principal idea run through The Things We’ve Seen?

MALLO

There is a recurring idea in the novel, the thesis that the dead are never entirely dead, that in fact we cohabit a kind of hybrid space, us and them, as well as that the largest social network ever is not that of the internet but the one that joins the living with the dead. This leads us additionally to the idea that we are all socially connected with somebody who died in war.

INTERVIEWER

What’s behind the title of the novel in Spanish? And how did the English title come about?

MALLO

The title in Spanish, Trilogía de la Guerra (War Trilogy), comes from the fact that, in effect, it is composed of a trio of novels shot through with the experiences of people who have either been through war, or are still living out wars they’ve been through. But they aren’t accounts of those wars, or indeed of the characters’ fortunes during them, but deal rather with what we might call the B side of war, its unsuspected echoes in our day-to-day lives, while also being a reflection on the nature of war. For example, the current-day economic tensions between northern and southern Europe are, to my mind, nothing but a contemporary, secular version of the war between the Protestant north and the Catholic south. In fact, one of the ideas in the novel is that it’s impossible to understand the conflicts in the world today without an idea of their religious origins. Every war has its origin in one religious cosmovision or another. However bygone they may appear, they come back around repeatedly. Or, for example, to ask oneself that if wars are legal—which they are—then what does it mean for certain wars to be adjudged illegal—or what difference there is, juridically as much as morally, between a war and an act of terrorism. One of the recurring phrases in the novel is an illuminating line by the Spanish poet Carlos Oroza, “It’s a mistake to take the things we’ve seen as a given,” hence the title of the English version, which in the context of this novel can be interpreted as “it’s a mistake to take as dead that which we have seen die.”

INTERVIEWER

How and when did you begin writing it?

MALLO

It started out of a coincidence, and in the exact same way as the journey undertaken by the protagonist in the first part of the novel. I was invited to take part in a symposium about online networks called Net Thinking on the island of San Simón, in northwest Spain, the unusual thing being that only fifteen people were going to be involved, fifteen of us cut off from the world for several days on this tiny island with its very turbulent history, from being a place where the pirate Francis Drake once took refuge, to a prison camp for Franco’s opponents during the Spanish Civil War. I agreed to take part because there was something funny about these conversations concerning networks and global connectivity due to be broadcast live around the world on TV and social media taking place while we were completely cut off from the world, confined to the island, as if inside Plato’s cave.

It also so happened that I’d owned a book for a number of years entitled Aillados, Galician for “isolates,” about this island during the time it served as a prison camp. It includes lots of photographs from that time, showing the prisoners in different moments and places, and I took it with me, for information more than anything else. The moment I stepped onto the island I could feel the weight of all the bones and other objects beneath my feet, a weight increased by the fact that not only were the different wings of the prison camp still intact, we were actually going to be lodging in them. Then, in spare moments, I started doing something that began out of mere curiosity—I went looking for the places in which the photographs in the book had been taken, and I would then take the same photograph but in the present day.

When I found the first location and took my photo and compared it with the one from 1937, I became conscious of the chasm separating the two. In one photo, prisoners looking back at the camera, some even smiling, people who had gone on to die, some of them by firing squad, and in my photo, in the here and now, a sunlit scene—greenery, the sea—which could just as well have been out of a tourist pamphlet. Between the two there lay a gap, a very deep historical, narrative, and political gap, which I tried to get to the other side of, but could not—a few short centimeters that at the same time constituted light-years. This produced a vertigo that prevented me from taking the step that would get me from one photo to the other. It was then that I had a sense of the dead never being entirely dead and the living never entirely alive, and of the fact that we actually coexist, we inhabit the same social network. And so I got to work writing something that would be an attempt to build a bridge to take me from one photograph to the other.

INTERVIEWER

What was the writing process like? How long did the project take?

MALLO

Well, about six years in all, during which the Spanish Civil War opened the way for other wars in different places in the world, and to reflecting on what war is, in general. I started writing the San Simón story, and as is the way with everything I do, whether it ends up as a novel, poetry, or nonfiction, I didn’t at that point know whether it would be short or long, I didn’t even know what genre it would eventually take shape as. After that, everything started accreting in a very organic way, a coming together of quotidian experiences, unexpected occurrences, little details that take you from one horizon to another, visions of a sort, or modest domestic epiphanies that ended up constructing a spontaneously articulated text much like a wide-ranging network. I think this is one of the characteristics of the texts I produce—their organization, not in a treelike or hierarchical mode, but more like multifaceted networks, the advantage of which being that this allows me to connect, with nothing but a metaphorical link, concepts, facts, or events that are in principle very far removed from one another. As for research, it was minimal, the less the better. I’m of the opinion that the need to read up on anything and everything in order to write a novel is a myth that stems from the realist tradition, or from the kind of novel with roots in journalism. Research is a stone that can weigh the writer down, dragging you into the abyss—it prevents you from imagining or being free in your fiction making.

INTERVIEWER

Did you travel or read anything in particular for this book?

MALLO

Yes, and both were actually important to the project. Although I don’t like traveling—I don’t believe in the idea of physical travel as necessarily superior to traveling inside one’s mind or to being holed up somewhere—my public activities as a writer mean I’m always having to go to one place or another, and I must admit that I pick up on details and have experiences on those trips that I later recycle and sublimate in the things I write. In the case of The Things We’ve Seen, there are aspects of my own experiences in Shanghai, Normandy, and the U.S. So after these six years of writing, which took me to a lot of other countries as well, and with certain reference points in mind, such as David Lynch, W. G. Sebald, Elias Canetti, and Salvador Dalí, I saw that I had a novel on my hands.

INTERVIEWER

In the Nocilla Trilogy, Julio Cortázar and Jorge Luis Borges—both Argentine—are very important influences. In The Things We’ve Seen, on the other hand, that weight falls more with two Spanish artists, with García Lorca and Salvador Dalí. Why?

MALLO

Out of aesthetic affinity. In Lorca’s case, his work has never interested me except for Poet in New York, which I find fascinating, and that’s why he features in the part of my novel that takes place in current-day New York. With Salvador Dalí it’s different. He seems to me one of the best writers of the twentieth century, as well as a total artist who at the beginning of the twentieth century was bringing a great talent to bear on the practice of what we would today call interdisciplinarity—theater, filmmaking, painting, performance, and literature. It seemed inevitable to me to have the ghosts of Lorca and Dalí meeting in Central Park today, speaking to one another through the railings—one who lives forever inside the park and the other elsewhere in the city, having this dialogue concerning their friendship, the war, Lorca’s death, and the value of modernity.

INTERVIEWER

Formally, The Things We’ve Seen represents a 180-degree turn from the Nocilla Trilogy, the turning point between which was Limbo, the novel you wrote between these two trilogies. What do you think it’s down to, this evolution from a fragmentation that was, let’s say, poetic in character, toward a greater emphasis on narrative? Could it have anything to do with the fact that Nocilla Dream started out as something you wrote by hand, and The Things We’ve Seen, I suppose, directly on the computer?

MALLO

Doubtless that’s part of it. Nocilla Dream and Nocilla Experience were written in a hotel bed in Thailand, when I was recovering from a broken hip after being hit by a motorbike while on holiday there and didn’t know how I was going to get back to Spain. I started making notes in a very intuitive way, on pieces of paper I found around the room, and at the end I saw that I had these novels. I also wrote Nocilla Lab by hand, in Sardinia, in a notebook I bought there, and the first hundred pages in that novel are made up of a single, unbroken paragraph, in a sort of Bernhardian style. Because of that, I believe there’s another element underlying the evolution in my prose, which has to do with that fact I was initially drawn to styles and forms I hadn’t tried before, and which, precisely because of that, I found it exciting, seductive, to try out. In other words, when I wrote the Nocilla Trilogy I didn’t know how to write the Nocilla Trilogy, I learned in the doing of it, and so if I went on writing in that style it would have been mechanical, something soulless for me. The same goes for writing Limbo, El Hacedor (de Borges) Remake (The Maker (by Borges) Remake), and my most recent novel, The Things We’ve Seen, which was a text that demanded I look into new forms, and prompted me to set myself the challenge of exploring them. It’s the only way writing makes sense to me—the excitement of looking for new personal worlds. Then again, obviously there’s also the question of time and growing older. Time passes and with it your cosmovisions shift.

INTERVIEWER

Writing is learned by writing. What about publishing?

MALLO

Indeed. When I wrote the Nocilla Trilogy, I didn’t know how to write something of that kind, and when I got to the end I couldn’t go on writing in that way because I knew by then how it was done, I had got the hang of it, and I therefore found it boring. The same with The Things We’ve Seen, when I wrote it I didn’t know how something like it was done, I learned over the course of six years of writing, and now that I know how it’s done I suppose I’ll write some different kind of fiction, because in order to make fiction I have to feel the excitement of aesthetically investigating my own poetics. And the same goes for when I’m tackling something in poetry or nonfiction. I write for myself, not for the reader. I think that writing for the reader is a mistake, there are millions of readers, there’s no such thing as “one reader,” and you’re therefore never going to make them all happy. It’s just as crazy to write to please a certain person as it is to displease someone. You have to write to investigate your own poetics, trusting that this poetics possesses sufficient empathy that it will connect with some readers, and nothing more. Anything else is bound to backfire, there will be the whiff of imposture.

INTERVIEWER

In Wittgenstein, Architect, your art project with the Spanish artist Bernardí Roig, you recall the moment in which you proposed climbing the rock face up to the philosopher’s cabin, taking the most direct route, and filming it, because “it is something that’s never been done.” To what extent do you believe that this impulse to innovate is a spark for your books?

MALLO

I suppose that’s part of it, but, being completely sincere, it isn’t a clear part of what motivates me. I don’t think, I’m going to innovate. That would probably mean not only not innovating, but making a fool of yourself. Things appear as in an emersion, from materials you’re already familiar with, things other people have given you, which you then work with and recombine so that something of your own emerges, something original. This, in general, is how the mystery of life functions, like all complex systems, like the brain, and that’s how a revolutionary painting by Michelangelo or a goal in a football match might come about. The way I write is by letting myself be taken along by everything from the way I was educated, my culture and my aspirations, and given that I did my further study in the sciences, naturally one of my aspirations is to propose new kinds of worlds, to create metaphors that did not exist before, were not articulated in this way. When I went to Norway and opened that direct climb to the Wittgenstein Cabin, it was on the basis of an idea that suddenly came to me once, to creatively combine various passions—rock climbing, Wittgenstein’s philosophy, and art. The principal idea of this action, video plus text, is the following. Rock climbing is drawing on a wall, tracing out a route using your body, so the idea was to get up to the cabin Wittgenstein built in 1914—a place for him to go and think—by the shortest route, to trace out a very direct route, which is of a piece with his philosophy at that time, the work leading up to the Tractatus.

INTERVIEWER

Again, it’s about a journey. Though you don’t like traveling, journeys are always a departure point for your work, journeys that are in some way conceptual, artistic projects. I mean, for example, the journey to the shoe tree in Nocilla Dream, or the journey through the Europe of World War II in The Things We’ve Seen. Your poetry also contains such experiences. How do you see the relationship between your literary work and journeys?

MALLO

Well, there are two things. The first is that I don’t like traveling for pleasure, simply to “go and see” something. The world has already very much been mapped and I believe that your usual journey, undertaken to “experience different situations” and “feel different emotions,” is a regurgitation, an echo of the nineteenth- and twentieth-century journeys of exploration in search of the “other”—that is, they respond to a concept of the “exotic,” typically Western, which holds no interest for me whatsoever, or at least doesn’t interest me currently as a physical act. This kind of journey is nothing more than a fiction that is not only colonial but, as I say, typically Western. In fact, we are the only culture that travels in order to “see things,” with no practical meaning to the journey, purely for leisure. In this sense, I even think the figure of the tourist is more honest and coherent than that of the traveler. And I believe that this whole search for the exotic and the “other” can and should now give way, in the twenty-first century, to something more effective, more real, and less invasive, traveling as it were secondhand—through social networks, books, television, Google Maps, et cetera—all of this being a kind of “travel” that redefines what is supposedly virtual and makes it real. For example, in The Things We’ve Seen, using Google Street View, I undertake Nietzsche’s famous walk in Turin, when he hugged the horse and fell permanently mute. Well, I did do that walk physically myself, I went there and did it, I retraced the steps Nietzsche took, but the things that showed up when I consulted the Street View version of the walk seemed far richer to me, far more suggestive for the novel. And secondly, yes I do like to travel but only with a certain objective in mind, with the idea of one project or another. And finally, when I travel I write a lot because I try to reproduce an ambience most approximate to that in my home, and in a hotel that can only happen by watching television and writing.

INTERVIEWER

The journeys you go on are conceptual projects, like those of Robert Smithson, who is one of your great influences, but there are surreal elements to them as well, like those of another guiding light, David Lynch.

MALLO

Yes, certainly, I’m very interested in the moment in which we introduce a slight distortion into reality, a “soft focus” that makes us see the real differently, the side that is not visible or not evident. This is the moment in which, paradoxically, we can see what reality was like and learn from it. It’s something that, in a different language, science does, saying to us that that which we did not believe real is also “another thing.” The glass of water on the table has another dimension if expressed in terms of the not at all arbitrary union of hydrogen and oxygen. And to undertake such an operation one has to see things somewhat surreally, in the most etymological sense of the word, “to wish to see above or beyond the [supposed] reality,” infer that which is not evident at first sight.

INTERVIEWER

What has it meant to you to be published in English?

MALLO

My work has been translated into many languages, but in none of them has my work resonated and had as much impact as in English, both in the UK and the U.S. So it’s wonderful for my work to be projected in this way, and it gives me a sense that my fictions are understandable not only in the habitat and cultural system of my own language, of Spanish—the Hispano-American language would be a better way of putting it—but also in a culture that is in principle very distinct—the Anglophone one. Though it is also true that, as Nicolas Bourriaud says, all artists and writers are today “radicants,” an apt simile that denotes us as climbing plants that, through fleeting accretions, take on elements of other cultures—we imbibe them, we utilize them, and later, when we make our way to other places and cultures, we let go of them in order that we can go on developing an art with global tendencies. We are semionauts.

INTERVIEWER

I once heard Eloy Fernández Porta say that Borges was the most punk writer of the twentieth century. Do you consider yourself a punk writer?

MALLO

Fernández Porta was exactly right, because Borges is one of the most radical writers of the twentieth century. Yes, I consider myself punk insofar as that means radical, because radical is not shouting more than others or setting fire to cars, but “grasping things by the root,” such being the etymological meaning of radical, which is what I try to do when I make poetry, or write novels or nonfiction—to write attempting to go to the root of things, to propose new aesthetics, and, above all, to work with no aesthetic or academic prejudices whatsoever. Or, put another way, writing what you need to write in each moment according to your creative needs, your culture, your environment, your aspirations, writing what you believe you must write.

—Translated from the Spanish by Thomas Bunstead

Jorge Carrión is the author of Bookshops: A Reader’s History, Against Amazon, and Madrid: Book of Books, all three of which were translated into English by Peter Bush.

Thomas Bunstead was born in London in 1982 and currently lives in west Wales. He has translated some of the leading Spanish-language writers working today, including Maria Gainza, Juan José Millás, and Enrique Vila-Matas, and his own writing has appeared in publications such as the Brixton Review of Books, Literary Hub, and The Paris Review. He is a former coeditor of the translation journal In Other Words and is a Royal Literary Fellow at Aberystwyth University (2021–2023).

March 23, 2021

Announcing the Next Editor of The Paris Review

Emily Stokes. Photo: Taryn Simon.

The board of The Paris Review Foundation, which publishes the literary quarterly The Paris Review, is pleased to announce the appointment of Emily Stokes as the next editor of The Paris Review. She will be the sixth editor in the sixty-eight-year history of the magazine.

Ms. Stokes joins from The New Yorker, where she has been a senior editor since 2018. Ms. Stokes was also an editor at T: The New York Times Style Magazine, Harper’s Magazine, and the Financial Times. She is a graduate of Cambridge University and was a Kennedy Memorial Trust scholar at Harvard.

“Emily will honor the Review’s tradition of discovery,” says Mona Simpson, the publisher of The Paris Review. “I believe she’ll publish distinctive work in a distinctive way, with courage, subtlety, and style.”

“Like many readers, I came to The Paris Review through its interviews, which show writing to be the hard, inspiring work that it is,” Ms. Stokes says. “Over the years the Review has introduced me to new and established writers who have provided the most pleasurable kind of company. After a year in which we have been alone and driven mad by the news, the Review’s mandate, to publish ‘the good writers and good poets, the non-drumbeaters and the non-axe-grinders,’ is a timely calling, and I am tremendously excited and grateful for this opportunity.”

“We are delighted to welcome Emily Stokes at a time when The Paris Review is reaching the broadest and largest audience in its history,” say the co-presidents of The Paris Review Foundation, Matt Holt and Akash Shah. “We are also grateful to our readers and other supporters, and to our staff, who continue to shepherd this institution with great dedication.”

The Paris Review was founded in Paris in 1953 by William Pène du Bois, Thomas H. Guinzburg, Harold L. Humes, Peter Matthiessen, John P. C. Train, and George Plimpton, who edited the publication from its inception until his death in 2003. Its interviews with major writers of the last hundred years have been hailed by one critic as “one of the single most persistent acts of cultural conservation in the history of the world.” The Paris Review Foundation also maintains an award-winning digital presence through its online publication, the Daily; has a book imprint using material first published in the magazine; and is producing the third season of The Paris Review Podcast.

For press inquiries, please contact Akash Shah, co-president of the foundation (ashah@theparisreview.org).

March 22, 2021

Touched by a Virgin

La Conquistadora at the Cathedral Basilica of Saint Francis of Assisi, commonly known as Saint Francis Cathedral, at 131 Cathedral Place in Santa Fe, New Mexico, on November 11, 2019. Photo: © gnagel / Adobe Stock.

My first published piece was in a book referred to in my family as Touched by a Virgin. The book is a collection of testimonials by people who have been touched, healed, or otherwise interfered with by the Mother of God. I did not submit my piece for inclusion in this book. It might best be categorized as the kind of book a great-aunt might buy you for a confirmation gift, and that you never read but somehow never give away. It’s a Chicken Soup for the Soul: Mariolatry Edition.

I do not list this publication on my CV. In fact, maybe we can agree between us to keep the fact of its existence a secret.

When I was twenty-five, in graduate school studying fiction writing, my grandmother called me from Santa Fe to tell me that at Mass that morning, she’d met a writer. “A real writer,” she clarified, as I did not yet count as a real writer—to her, to myself, to anyone.

“Oh, was she nice,” my grandmother said. “I told her you wanted to be a writer, too.”

I didn’t think much of this. My grandmother is always meeting people. In a family full of introverts, my grandmother is the outlier. She favors bright colors—golds and magentas and pinks and reds—and loves a party. When I was in high school, spending summers with her, if we were out for dinner, she’d ostentatiously place her margarita on the table between us so I could take sips. If we were downtown together, in a shop or on the Plaza, in any kind of proximity to a good-looking guy my age, she’d nudge me forward to talk to him, then finally, in exasperation, strike up a conversation with him herself. She makes friends everywhere: on airplanes, at the grocery store, in public restrooms. Of course she’d befriended a new face at Mass.

My grandmother went on to say that she’d invited this real writer home for lunch, and had shown this real writer my “beautiful story” and that this real writer had asked to keep a copy of it. You can see where this is going, but I couldn’t.

My “beautiful story,” as my grandmother called it, was my college application essay, written just after I’d turned seventeen. It was about attending Mass with my grandmother at the Saint Francis Cathedral in Santa Fe. It was also about my special affection for and fascination with the wooden statue of the Blessed Mother brought by the Spanish in 1626 during their conquest of the New World—a bloody conquest they framed as a holy war.

La Conquistadora is the oldest continuously venerated image of the Blessed Mother in the United States. She lived in Santa Fe for fifty years, until the Pueblo Revolt in 1680, when the Pueblo people retook the land that had been stolen from them by the Spanish. The remaining Spanish settlers fled with the statue. Twelve years later, the fight was on again: Don Diego de Vargas returned the statue to what he proclaimed was her rightful place in what has been called the “bloodless reconquest” of Santa Fe—“bloodless,” perhaps, until Don Diego de Vargas ordered the mass execution of Pueblo men and the enslavement of Pueblo women and children. In the nineties the statue’s name was changed to Our Lady of Peace.

Here, from the prayer by the priest and New Mexico historian and genealogist Fray Angélico Chávez on a prayer card, is an example of the kind of peacenik language that sums up La Conquistadora’s role in the region: “O Conquistadora, our Patroness and Queen, the woman whose seed will crush the serpent’s head … O Conquistadora, our Patroness and Queen, through Jesus Christ, the Prince of Peace, and our Universal King, convert all the infidels and enemies of the Peace of Christ … ” In his rather sweet history of the statue, written in her voice, Fray Angélico tried, not very successfully, to reconcile La Conquistadora’s contradictory roles as representative of peace and mascot of a violent land grab.

La Conquistadora stands two and a half feet tall. Her carved face is placid and regal and a little bored looking; her hair, a wig, is thick and dark under a veil. Sometimes, though not always, she holds an infant Jesus rather loosely in her large, stiff hands. He has to be pinned to her dress, and his startled expression reflects his understanding of his precarious position.