The Paris Review's Blog, page 118

April 14, 2021

Tope Folarin, Fiction

Tope Folarin. Photo: Beowulf Sheehan.

Tope Folarin is a Nigerian American writer based in Washington, DC. He won the Caine Prize for African Writing in 2013 and was shortlisted once again in 2016. He was also named to the 2019 Africa39 list of the most promising African writers under 40. He was educated at Morehouse College and the University of Oxford, where he earned two Masters degrees as a Rhodes Scholar. A Particular Kind of Black Man is his first book.

*

An excerpt from A Particular Kind of Black Man:

Tayo and I learned early on that all junkyards are basically the same. Dad had been taking us to junkyards all over Utah since we were toddlers, and we’d grown accustomed to the sights. At the front of the entire mess is a shack that’s supposed to serve as an entryway, checkout counter, and, depending on the whims of the owner, a bar as well. Inside the shack there are car parts strewn all over the place: exhaust pipes on the counter, alternators and radiators spread across the floor, license plates everywhere. At the back of the shack there’s a door that leads to the junkyard, a gate to another land.

For each junkyard is like an unexplored planet. The terrain is always unfamiliar; the air barely breathable. There are craters everywhere, and my father moves forward carefully, scouting the path ahead before calling back telling us it’s okay to follow. Every junkyard looks like the site of a massive industrial explosion, the secret innards of various contraptions laid out for us to see, while we roam about like postapocalyptic scavengers searching for the parts that will make our dying car go.

There wasn’t much scavenging on this visit, though. Dad woke Tayo and me before dawn on the first day of our summer vacation and we drove to the Hartville Junkyard in our new ice cream truck. He asked the man behind the desk to follow us, and we walked through the industrial rubble until we came upon a long, sleek-looking freezer. Dad pointed at it.

“This is the one I want. How much?”

The man wheezed in response. “For this? This is top of the line, yes, sir. This’ll probably run you about . . . oh, I’d say about two-hundred fifty dollars.”

“But it doesn’t work,” my father replied flatly.

“Don’t matter. She’s a looker. I could get someone to come out here and pay three hundred for her.”

Back and forth they went until they settled on a price. One hundred eighty-five dollars, and the man threw in a carburetor for free. Dad laughed long and hard after the man left to draw up our receipt.

“See? What did I tell you? I drive the best bargains in all of Utah!”

We returned home with the freezer in the back of the truck, and Femi joined us in cleaning it. Femi still had a thick Nigerian accent then, and I couldn’t decide if I liked him or not. This was the era when Tayo and I were basically the same person—same speech patterns (a solid middle-American accent spackled with the occasional Nigerian-accented phrase), same walk (a loping, confident gait that we’d adapted from our father’s), and we each possessed a similar propensity for attracting occasional trouble (for various things, but we both excelled at watching television when there were dishes that needed washing). Femi’s younger than Tayo and me, but he was our stepmother’s oldest, and back then he carried himself like a kid with responsibility. I couldn’t tell if he was acting perfect on purpose.

When we finished Dad told us to transfer a few boxes of ice cream from the freezer in the garage to the freezer in the truck. We did as we were told, and then Femi asked him how the ice cream would stay cold since the freezer didn’t work. Dad turned around in his seat.

“Why don’t you guys trust me? I have everything covered. Are you finished?”

We nodded and Dad immediately put the truck into reverse.

Steven Dunn, Fiction

Steven Dunn. Photo: Beowulf Sheehan.

Steven Dunn, aka Pot Hole (cuz he’s deep in these streets) is the author of two novels from Tarpaulin Sky Press: Potted Meat (2016) and water & power (2018). Potted Meat was a finalist for the Colorado Book Award, and shortlisted for Granta Magazine’s Best of Young American Novelists, and adapted to a short film by Foothills Productions. The Usual Route has played at L.A. International Film Festival, Houston International Film Festival, and others. He was born and raised in West Virginia, and teaches in the M.F.A. programs at Regis University and Cornell College.

*

An excerpt from Potted Meat:

LOSE A TURN

Grandma thinks I’m her husband again. He died before I was born. She says to me, Remember when you came home from the mines all dirty and took me dancin. Yeah, I say, we had big fun. And that one gal, she says, whats her name, you know, that slew-footed heffa, the one starin at you. Aw cmon now, I say, that was nuthin, you know I only got eyes for you.

Grandma slips back in. She says, Boy, you wash them dishes yet. I was just about to, I say. Well what you waitin on. She changes the channel to Wheel of Fortune and solves a puzzle before I do, and before the people on the show do. Them some slow-ass folks on that show, she says. A commercial comes on. She looks at me. That was a real nice date, huh, dontcha remember.

I wasnt dirty I tell you that. I got off of work, came home, cleant myself up, and put on one of them nice suits, a real nice one. I told her to put on her dancin shoes cuz we was gonna hit the town. Now I aint never been the dancin type, but after I had me a few whiskies I shonuff cut a rug that night. I got to twirlin her round with one finger. Beige dress flutterin all over the place, showin them pretty legs. Boy I tell ya, that was a good night.

Grandma is too old to wipe her own butt. Last week when I was wiping her butt, she slipped out again. Who the fuck are you touchin my ass, she said. Like usual I was holding her arms with one hand while wiping her with the other. She started hitting me and trying to roll off her potty chair. My hand slipped down and shit smeared my forearm. Get the fuck off me, she said. The best thing to do is wait until she slips back, so I walked to the bathroom to wash my arm and hand. I walked back to the room and she was still sitting on the potty chair. Its you again, she said, dear God, please help.

I told you we was gonna find a nice church in West Virginia once we got settled. I know the churches aint like the ones back home in Louisiana, but theyll do, baby. The mines payin me good, you makin some good friends, plys we got all these damn kids runnin around here. We gonna be alright.

Grandma finally called for me. I walked into the room and she said, would you mind helping me please, I had a little accident. I started wiping her, but the shit had dried a little and the toilet paper kept crumbling off. I soaked a washrag with warm water and soap. Thank you, she said, it must be something I’m eating thats making me mess all over myself. She farted. And started laughing. Thats enough gas to put in that car out there, she said.

Wheel of Fortune comes back from commercial. After every plate I wash I turn and look at Grandma. As long as I can see her looking up like she is thinking I think she is present. As long as I can hear her calling out an R or S or T or L or N or E, I think she is present. Buy a vowel, she says. She’s still here. Buy another vowel, she says. She’s still here.

Jordan E. Cooper, Drama

Jordan E. Cooper. Photo: Beowulf Sheehan.

Jordan E. Cooper is an OBIE Award–winning playwright and performer who was most recently chosen to be one of OUT Magazine’s “Entertainer of the Year.” Last spring he had a sold out run of his play Ain’t No Mo’, a New York Times Critics Pick. Jordan created a pandemic-centered short film called “Mama Got A Cough” that’s been featured in National Geographic and was named “Best of 2020” by the New York Times. He is currently filming The Ms. Pat Show, an R-rated “old school” sitcom he created for BET+, which will debut later this year. He can also be seen as “Tyrone” in the final season of FX’s Pose.

*

An excerpt from Ain’t No Mo’:

ZAMATA: Free?

WOMAN: (To TV) Bitch said free.

ZAMATA: What free?

WOMAN: (To TV) What country?

NEWSWOMAN: Land of the free.

WOMAN: (To TV) What free?

ZAMATA: What land?

NEWSWOMAN: This land.

WOMAN AND ZAMATA: Has free?

NEWSWOMAN: We’re all free.

ZAMATA: To do what?

NEWSWOMAN: Be free.

ZAMATA: Says who?

NEWSWOMAN: The free.

ZAMATA: Didn’t you report on the Damien Martin shooting?

WOMAN: She did! (To Trisha) They’re talking about your man over here, girl.

NEWSWOMAN: Yes.

ZAMATA: Was he free?

NEWSWOMAN: Yes.

WOMAN: (To TV) To die! They killed his ass too.

DAMIEN: Another way is coming!

TRISHA: Would you stop?

WOMAN: (To Trisha) What? He dead ain’t he?

DAMIEN: I’ll stop when you listen. I know you feel what’s right.

ZAMATA: And what about that woman they strangled last night?

WOMAN: Was she free?

NEWSWOMAN: Yes.

ZAMATA: And the baby they slaughtered last week?

NEWSWOMAN: Who is ‘They’?

WOMAN: They!

TRISHA: Them.

ZAMATA: The land.

TRISHA, ZAMATA AND WOMAN: The free

Joshua Bennett, Poetry and Nonfiction

Joshua Bennett. Photo: Beowulf Sheehan.

Joshua Bennett is the author of three books of poetry and literary criticism: The Sobbing School (Penguin, 2016), Owed (Penguin, 2020), and Being Property Once Myself (Harvard University Press, 2020), which was a winner of the Thomas J. Wilson Memorial Prize. He is the Mellon Assistant Professor of English and Creative Writing at Dartmouth College. Bennett holds a Ph.D. in English from Princeton University, and an M.A. in Theatre and Performance Studies from the University of Warwick, where he was a Marshall Scholar. He has received fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the Ford Foundation, and the Society of Fellows at Harvard University. His writing has appeared in The Nation, the New York Times, The Paris Review, Poetry, and elsewhere. His next book of creative nonfiction, Spoken Word: A Cultural History, is forthcoming from Knopf.

*

An excerpt from “Where Is Black Life Lived?”:

I’ve been thinking quite a bit recently about the role of air in African American letters. The people that could fly. Eric Garner. Christina Sharpe highlighting the link between anti-black racism and the weather. It bears remembering. For the legal studies scholar and foundational critical race theorist Derrick Bell, one of the first characteristics of the black utopia he describes in his classic vignette, “Afrolantica Awakening,” is that it is simply a place where we can breathe. A space of celebration and retreat, somehow flourishing both inside and beyond the constraints of the present order. The sanctuary; the dancehall; my grandmother’s salon, glistening at a distance. When we turn to the written page, where is Black life lived? Anywhere. Everywhere. Underwater, outer space, underground. Even where there is no air at all. We imagine it as if it were otherwise. We conjure a world that is worthy of us. And then we gather there: unbowed, unburied, unabashed in our joy.

*

An excerpt from The Study of Human Life:

“Dad Poem (Ultrasound #2)”

……..with a line from Gwendolyn Brooks

Months into the plague now,

I am disallowed

entry even into the waiting

room with Mom, escorted outside

instead by men armed

with guns & bottles

of hand sanitizer, their entire

countenance its own American

metaphor. So the first time

I see you in full force,

I am pacing maniacally

up & down the block outside,

Facetiming the radiologist

& your mother too,

her arm angled like a cellist’s

to help me see.

We are dazzled by the sight

of each bone in your feet,

the pulsing black archipelago

of your heart, your fists in front

of your face like mine when I

was only just born, ten times as big

as you are now. Your great-grandmother

calls me Tyson the moment she sees

this pose. Prefigures a boy

built for conflict, her barbarous

and metal little man. She leaves

the world only months after we learn

you are entering into it. And her mind

the year before that. In the dementia’s final

days, she envisions herself as a girl

of seventeen, running through fields

of strawberries, unfettered as a king

-fisher. I watch your stance and imagine

her laughter echoing back across the ages,

you, her youngest descendant born into

freedom, our littlest burden-lifter, world

-beater, avant-garde percussionist

swinging darkness into song.

April 13, 2021

Redux: Come, Be My Camera

Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

Suzan-Lori Parks. Photo courtesy of Parks.

This week at The Paris Review, we’re thinking about writing for the screen and stage versus the page. Read on for Suzan-Lori Parks’s Art of Theater interview, James Salter’s short story “The Cinema,” and Claribel Alegría’s poem “Documentary.”

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, and poems, why not subscribe to The Paris Review? You’ll also get four new issues of the quarterly delivered straight to your door. Or, subscribe to our new bundle and receive Poets at Work for 25% off.

Suzan-Lori Parks, The Art of Theater No. 18

Issue no. 235 (Winter 2020)

I love the process of writing. Whether it’s a TV script or a play, novel, song, or a film script, writing is all the same process. Just the rhythms are different. And where you have to begin and end is different. And how much you can see of a scene is different. What details you need to make a scene. In the novel, there are more words in those details. You can’t just say, “She’s tall and good looking.” You’ve got to let us know how so! Give me specifics. You’ve got to let us know how good looking she is.

Photo: Bhuoc9. CC BY-SA 4.0, (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...), via Wikimedia Commons.

The Cinema

By James Salter

Issue no. 49 (Summer 1970)

It was now Iles’ turn, the time to expose his ideas. He plunged in. He was like a kind of crazy schoolmaster as he described the work, part Freud, part lovelorn columnist, tracing interior lines and motives deep as rivers. Members of the crew had sneaked in to stand near the door. Guivi jotted something in his script.

“Yes, notes, make notes,” Iles told him, “I am saying some brilliant things.”

A performance was built up in layers, like a painting, that was his method, to start with this, add this, then this, and so forth. It expanded, became rich, developed depths and undercurrents. Then in the end they would cut it back, reduce it to half its size. That was what he meant by good acting.

Photo: Cquoi. CC BY-SA 4.0, (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...), via Wikimedia Commons.

Documentary

By Claribel Alegría, translated by Darwin T Flakoll

Issue no. 108 (Fall 1988)

Come, be my camera.

Let’s photograph the ant heap

the queen ant

extruding sacks of coffee,

my country.

It’s the harvest.

Focus on the sleeping family

cluttering the ditch …

If you enjoyed the above, don’t forget to subscribe! In addition to four print issues per year, you’ll also receive complete digital access to our sixty-eight years’ worth of archives. Or, subscribe to our new bundle and receive Poets at Work for 25% off.

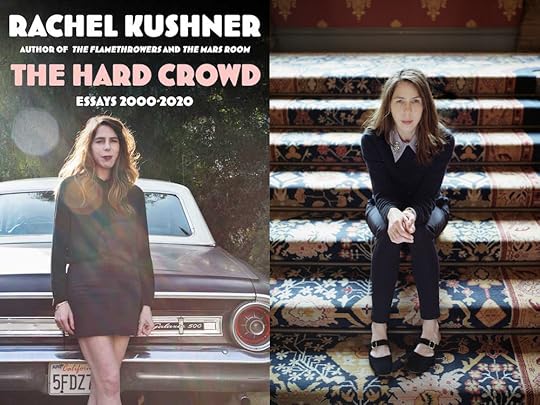

On Memory and Motorcycles: An Interview with Rachel Kushner

Photo: Gabby Laurent.

One morning last week, while sitting at my desk attempting to make headway on various writing assignments, I went on Craigslist and bought a motorcycle—a banana-yellow 1969 Honda CT90 Trail. It was something I had been thinking about doing for a while. I’ve been interested in motorcycles since I was a kid, and a few years ago, I took a course and got my license. But if I’m being honest, the decision to finally bite the bullet and get a bike was at least partially influenced by the opening essay of Rachel Kushner’s new collection, The Hard Crowd .

Kushner, the author of the novels Telex from Cuba (2008), The Flamethrowers (2013), and The Mars Room (2018), wrote the essay in question, “Girl on a Motorcycle,” in 2001 for an anthology titled She’s a Bad Motorcycle: Writers on Riding. Describing her first bike, a 500cc Moto Guzzi, Kushner’s voice has all the confidence, wisdom, and cool of her later work. “Motorcycles didn’t enter my own life as gifts from men or ways to travel to men,” Kushner asserts, “but as machines to be ridden.” The piece goes on to describe something called the Cabo 1000, an illegal and dangerous thousand-mile motorcycle race on the Baja California peninsula, much of which takes place on dirt roads that weave precipitously through desert mountains. Kushner participated in the race when she was twenty-four, the age I am now.

The parallels between Kushner and me end here. Next to the bikes she and her friends rode, my motorcycle would look like a tricycle. At one point during the Cabo 1000, Kushner clocked 142 miles an hour. At its very fastest, my bike won’t go much over 50. Still, something about the self-possession and sheer high-octane energy of Kushner’s writing—and her descriptions of the pleasures of the road, where she feels “kinetic and unfettered and alone”—took hold of my imagination and propelled me to pursue my own, albeit more modest, thrills.

Not all the essays in The Hard Crowd are automotive in nature. Kushner also writes elegantly about Italian film, prison reform, sea captains, and Marguerite Duras. There is a remarkable and heartbreaking piece about a crowded refugee camp for Palestinians inside Jerusalem. There are sensitive and expansive considerations of Denis Johnson, Clarice Lispector, Cormac McCarthy, and Jeff Koons, among others. The critic James Wood uses the term “serious noticing” to describe the kind of looking that great novelists do, the revelatory and incisive attention to detail that “rescues the life of things.” Kushner does a lot of serious noticing in this book, of people, places, images, and texts. She also reflects on the various “hard crowds” she has been a part of, conjuring the San Francisco of her youth—a grungy haven populated by bikers, skaters, punk rockers, poets, and dropouts—with vivid, transporting detail. She recalls the friends she had in those years, when she was waitressing and hanging around in bars in the Tenderloin, as some of “the most brightly alive people” she ever knew. Many parts of this book read like a love letter to them, as well as to her younger self and to the places and experiences that shaped her.

This interview was conducted via email in late March. Throughout our exchange, Kushner was funny, thoughtful, and generous with her responses. And while I will not, of course, divulge the author’s email address, I can report that it is among the cleverest I have encountered.

INTERVIEWER

The Hard Crowd is a collection of essays from 2000 through 2020. What was it like to revisit your past work? Have any of the essays taken on new meaning for you as they’ve aged?

KUSHNER

For years I’ve toyed with the idea of putting together a collection of essays, as they’ve piled up—I’ve been writing them since before I published any fiction—but I wasn’t in a hurry. I needed to find the right through line, an organizing principle that would seem appealing and deliberate. It was only when this phrase “the hard crowd” came to me as a title that I sat down and looked at everything and started pulling out pieces I thought could sit next to one another in a sequence. I excluded most of my writing on contemporary art, because the discourse of visual art is somewhat specialized—maybe someday I’ll make a book of those pieces. For The Hard Crowd, I was looking for a certain kind of resonance. The idea was to make a proper book that is meant to be read in order, from beginning to end, each essay “passing the torch.” When I got to the end, I wrote the title essay and realized this book was some kind of statement about who I am and what I value. This took me by surprise. I thought this was a side project, but the book has as much to do with who I am as my novels do.

INTERVIEWER

Did you significantly rewrite or expand any of the pieces from their original forms? If so, which ones, and in what ways?

KUSHNER

I revised most of the essays. First, one by one. Later, I made changes based on how the pieces talked to one another, page 1 to page 250. The first essay, about the Cabo 1000, I hadn’t looked at since I’d published it twenty years back. It’s full of details I have no memory of. If I hadn’t written them down, they’d be erased, gone. At first I wasn’t sure how or whether to revise such a thing, given that it’s an archive of a version of me that no longer exists. But the more I opened up the essay to examine it as mine, as something to scrutinize and improve, the more alive it became, receptive and amenable to new interventions. I’d written the essay on Marguerite Duras for an Everyman’s Library edition of her work, and it had also appeared on The New Yorker’s website. But regardless, I wrote a new opening and restructured the essay. I’m always learning more about Duras and thinking more about her work, and I wanted to bring in some elements that would have been less relevant to the Everyman’s collection, like her script for Hiroshima mon amour, whose more unsettling thematics—like that Duras is basically equating the trauma of a French girl’s affair with a German soldier with the annihilation of Hiroshima—get kind of swept under the rug. I totally revised the Jeff Koons essay, “Happy Hour,” to think more vigorously about his version of populism, and it has a new ending that’s a bit mean to one of his collectors, but also seemed warranted.

INTERVIEWER

The opening essay is about your experiences riding motorcycles in California in your early twenties and the biker community you were a part of. It centers around the story of your participation in a harrowing and illegal thousand-mile motorcycle race down the Baja California peninsula. Why did you choose that to be the opening piece?

KUSHNER

I knew right away it would be the opening piece. It was the first thing I ever published, but more importantly, it gives an account of who I was before I was a writer. At least one version of who I was. It’s a granular glimpse into a certain world—gearhead San Francisco in the nineties, which I lived—and so it pertains somehow to who I am still. That experience of the Cabo 1000, it would feel harrowing if I had to do that now, but I don’t think it seemed harrowing then, although there were some dicey moments, which I detail in the piece. I remember being really disappointed that I’d crashed because I’d spent so much time prepping my 600 Ninja. I don’t remember thinking, I could have died. I was preoccupied with my motorcycle. Especially after the ambulance drove over and crushed all the expensive fiberglass bodywork that had come off my bike in the crash. When you’re involved in something, you see it up close. But also, I’ve never been someone who thinks about the what-might-have-been—I go with the what-was. I was fine, relatively. And as I say in the essay, even despite crashing at 130 miles an hour, having my motorcycle stolen, having all my possessions bounced out of the truck bed, et cetera, my attitude was intact. I remember a feeling of genuine happiness.

INTERVIEWER

I’m curious about whether you see any relationship between riding motorcycles and writing. Do you think a writer needs to be fearless?

KUSHNER

I don’t think a writer needs to be fearless. I don’t look at things quite that way. If one were to divide writers into two crude categories, I believe that some face inward and some face outward. To know themselves, some writers look inward. Others, in order to have a sense of themselves as bounded entities, need to be immersed in the unknown world. I believe this is a basic orientation that you’re probably born with—which way you face. I face outward. Even when I was very young, I gravitated toward worlds of knowledge and people, subcultures, that had to be learned directly, through experience, as if this process of immersion in the unknown would help me to understand myself. This orientation might seem brave to some, but it isn’t required to become a writer. You can live a sheltered life and still be a great writer, although perhaps making something unique and startling and innovative in both cases requires not caring what other people think. But I’m not sure if that’s bravery or something else—purpose and vision, maybe.

INTERVIEWER

You have written three novels and a small collection of stories. Do you think of yourself primarily as a fiction writer? What do you see as the unique challenges and possibilities of nonfiction?

KUSHNER

Yes, a fiction writer—without proof or elaboration. That’s the thing, what I’m after. I’ve always interspersed novels with these assignments, which are sometimes desirable breaks, and they expose me to knowledge and ideas that might prove useful later. Those longer pieces for The New York Times Magazine, which I included in the book—on Palestine and on Ruth Wilson Gilmore and prison abolition—are unique in that they allowed me to fully commit myself to some other world and to try to understand it. If novels are always some charged engagement with one’s own unconscious, those pieces—in which, respectively, I went to a refugee camp where 85,000 people live in one square kilometer, and I spent a week talking to Gilmore, who basically invented her own category of geography scholarship and possesses bodies of knowledge of which I’m woefully ignorant—those pursuits required me to submit and listen and learn. They each posed specific challenges. The Palestine piece was me as an on-the-ground observer, hoping to communicate for the reader what anyone might have felt had they been in my shoes the weekend I spent in the camp. The prison abolition piece was making an argument, and needed to humbly present its case in a convincing manner to even the most defensive and reactionary reader. Both benefited greatly from my collaboration with my editor at the Times Magazine, Claire Gutierrez.

INTERVIEWER

Can you describe your writing process a little bit? Do you write every day? Do you have any specific habits or rituals around how you work?

KUSHNER

I try to work every weekday. Sometimes, more with fiction than with essays, I find that I’m combing over what I already wrote, which I now consider wasted time. I used to think procrastination was part of the process and not to be fretted over. Recently I read this interview with Roni Horn—an amazing artist—and she said procrastination is escapism or laziness. That shook me awake. I don’t have rituals except the computer I write fiction on isn’t connected to the internet. The office I write in is a poor man’s version of Freud’s office, with globes, tchotchkes, rugs, and ancient artifacts—but instead of plundered Egyptian tombs, most of this stuff comes from the thrift stores of Bakersfield, California.

INTERVIEWER

One thing I noticed was that you almost never end a piece where I might have expected you to—and you don’t seem interested in landing anywhere definitive. It feels almost as though you are actively resisting drawing conclusions, preferring instead to linger on a question or an image or a moral paradox. You do a beautiful job of crafting endings that are satisfying while still leaving room for ambivalence and uncertainty. How do you know when a piece is finished?

KUSHNER

If a writer presents themselves as the one with moral clarity, I’m suspicious. Even when the writer offers themselves up as the fall guy, I’m suspicious, because the effect is still, ultimately, to establish a moral clarity. I like to make a true-feeling statement and then look for things that challenge it and tear it down. In terms of endings, I changed some of them as I was revising these essays. Suddenly a new end that was clever but not pat, or made a new swerve I hadn’t previously seen as possible, announced itself. The ending can reframe the whole essay, even for the person who wrote it. I didn’t rewrite this ending, but the essay about “bad captains” ending with professional basketball players disembarking the boat first, before everyone else, just seemed exactly right. A new world hierarchy I could get behind.

INTERVIEWER

In your essay on Koons, there’s a wonderful line that appears almost as an aside, buried in em dashes, where you say “abstraction, after all, is the language of the rich.” That made me laugh and got me thinking about abstraction more generally. Abstraction can be used, as it is in this instance, to mask or soften violent politics—or, in the example of Koons’s advertisements, to communicate a kind of class fantasy—but abstraction is also a fundamental element of language. All writers must traffic in abstraction to some extent, right? How do you think about abstraction in your own work?

KUSHNER

You say it perhaps better than I could—that abstraction can be used to mask or soften the violence of property relations, and to communicate fantasies of class identification for the purposes of advertising. I got this originally from Koons’s claim about liquor ads going from explicit tableaux you can unpack quickly in looking at them—usually men and women about to hook up—to the monochrome of a Frangelico ad, as he moved from poor to wealthy neighborhoods. I was thinking of the discourse of advertising and the eighties, when Koons made these liquor ad paintings. And when I was revising this piece for the book, I thought, Wait a minute. Truly rich people don’t buy Frangelico. They buy Jeff Koons paintings.

All culture traffics in abstraction, and probably one could make an argument that education, property, and social class correlate with abstraction in visual art, but there would be exceptions. About my own work, I’m really not sure. I go by instinct, which isn’t exactly abstract but suggests that one has to approach things from some unexpected angle. You have to sneak up on yourself. If you know too explicitly what you want to say, the whole process feels dead. In that sense, I guess I court abstraction, if not the explicit investment in abstraction I was making fun of in that essay, an aesthetic that reassures rich people they are safely distant from the realm of kitsch.

INTERVIEWER

I imagine there aren’t many people in the world who have both attended dinner parties with trustees of the Whitney Museum and spent time in a Palestinian refugee camp. These feel like distant universes—worlds that are hard to reconcile—and yet they are united here by your voice and perspective. Can you talk a little bit about how your ability to occupy those different spaces informs your work? Are you a different person, a different writer, in each context? Is it ever disorienting?

KUSHNER

I’m the same person whether in Shuafat—where I felt humbled and awed by a world that was foreign to me—or at some art-world thing where I am not awed or humbled but still watching things from a remove. I don’t think of my life as divergent or broad, really. Some of the lucky opportunities I’ve had come with the territory of being a writer. I didn’t seek out going to Palestine and instead was invited there and said yes, because it seemed like I could learn a lot. But I guess I did choose to go to Shuafat refugee camp. I can’t recall feeling disorientation, except when I found out my host, Baha Nababta, had been murdered. That threw me for a loop. But I think that’s not the kind of thing you meant. I’m often willing to meet people on their turf, their reality, but that’s because I have range and not because I’m shape-shifting. I just pull from the part of me that is applicable to the situation.

INTERVIEWER

In your essay on Denis Johnson, a writer I deeply admire, you write, “[His] stories are about death and immortality, art and its reach, and they ask elemental questions about fiction, not as a literary genre but as a human tendency.” That is a wonderful way to frame the stakes of his work. What do you mean by “fiction as a human tendency”?

KUSHNER

Some people are full of it, but lies can be kind of interesting. The lie is sometimes a pretty honest portrait of who someone is. I think in the line you quote I was referring specifically to the stories in his final book, The Largesse of the Sea Maiden, which is full of tales that people are telling others and themselves, like the narrator who tells the story about this guy who has a prosthetic leg and the woman he marries. “You and I know what goes on,” the narrator tells us, and, like, no—we do not know what goes on. We know only what goes on in the mind of the person telling this story, which is that he’s picturing these two people screw. Maybe I meant fiction as a tendency not quite in the by now hackneyed “tell ourselves stories in order to blah blah” manner but as a less dignified and more blunt kind of chatter, either internal or spoken out loud, fired, or misfired in some direction. There are lots of scenes in his books of people bullshitting other people and making grand declarations to upholster some debased or delusional moment with meaning. “We killed the mother and saved the children,” Georgie says famously in “Emergency,” of these baby rabbits that he has carved from their mother’s belly and that they definitely do not save.

I think beyond his work, Denis Johnson probably had great sympathy for tall tales, not as maliciousness, but just because they’re how people get by. My friend James Benning met Johnson years ago in Santa Fe, New Mexico. They were both supposed to attend this boring function where they were each being honored. They immediately hit it off, decided not to attend the function, and spent the evening drinking in various bars together instead.

INTERVIEWER

That sounds like fun. Now, I was curious about the epigraph of the book, which is a quote from Clarice Lispector that comes up again in the penultimate essay—“What others get from me is then reflected back onto me, and forms the atmosphere called: ‘I.’ ” Why did you choose that?

KUSHNER

When I chose it, I knew my editor, Nan Graham, wanted to use the photograph of me with my car for the cover of this book. Partly, I was thinking of that. The immodesty of putting my own image on my book, an image that might be functioning to steer the reader toward some idea, some fantasy, of who I am. And from there, I’m calculating the reader’s idea of who I am into who I think I am. But it’s about much more than a photograph. It suggests flow from me to others and back to me, a vulnerability and receptivity that I cherish. Maybe we are all doing this all the time, but it requires a mystic like Lispector to spell it out.

INTERVIEWER

Reflecting on old friends and people you knew in San Francisco, you write, “I was the weak link, the mind always at some remove: watching myself and other people, absorbing the events of their lives and mine. To be hard is to let things roll off you, to live in the present, to not dwell or worry. And even though I stayed out late, committed to the end, some part of me had left early. To become a writer is to have left early no matter what time you got home.” Are you suggesting here that to be a writer is to be something of an outsider, observing the people and things that inspire you without fully participating in life? It’s interesting to me because your essays seem to suggest just the opposite—that you are someone who has lived voraciously.

KUSHNER

If to be a writer is “to have left early,” the key subordinate is “no matter what time you got home.” I’m trying to get at a form of distance that isn’t an outsider’s purview. You can be immersed, an insider, but if you’re the one who later turned out to have been the writer, then by virtue of what you noticed and thought about, and through the act of recording what you noticed and thought about, you install distance. I wasn’t an outsider among the people I describe in the title essay. I probably hid certain parts of myself. But every thoughtful person does that to survive their youth, and the people I admired as living in the present and letting things roll off their back, maybe they were hiding something also, but from my perspective they were, as the expression goes, “about that life.”

In delving into autobiographical territory, I had to think about what the act of writing about my own life is, and means. And I decided that it’s something of a conversion. You’re made different in the very act of putting your memories into a concrete form. My sense is that by the time you’re able to write the experience down, you aren’t the same person who lived it, and whoever you were, or thought you were, is recast by the odd confidence, the dubious bravado, of putting pen to paper.

INTERVIEWER

In the same essay, you describe yourself as “soft” compared to the people around you—and you say you understood that softness to be a kind of moral failing. What has being “the soft one” meant to you in your life?

KUSHNER

I was thinking out loud about this idea of a hard crowd and who is hard, and I would never romanticize myself as such. But my emphasis there wasn’t so much on me, nor softness generally, and more on what I admired in other people growing up, how people are stars and have star quality. The people who impress you, they live in your head forever. And maybe what I mean by softness is the ability to notice that star quality, to take it in. The people I have known have shaped my life more than Proust or Dostoyevsky has.

INTERVIEWER

Lastly, what have you read recently that you particularly enjoyed?

KUSHNER

All spring I’ve been reading Adorno’s Minima Moralia. I’m auditing a graduate class that is entirely that book. I find it difficult. The style isn’t even quite “dialectical” to my layperson’s mind. It’s what perhaps gets left out of the dialectic, the shards and debris that refuse synthesis. Even the title—“little ethics”—is a mystery. Latin, but why? It’s an attempt to echo ancient philosophy, but more through contrast than emulation. Much or even all of the book is about the loss of the possibility of ethics. No good life, Adorno says, in a wrong world. Now totally accustomed to that wrong world, a contemporary reader has to grasp the material, social, and historical conditions whose loss Adorno mourns, and also one has to grasp Adorno’s sentences, which scroll out, then undercut themselves, so that one cannot be quite sure what he’s saying, but you can at least gather that all is subordinated to the economy, and that everything is ruined.

Cornelia Channing is a writer from Bridgehampton, New York. She is a copy editor at New York Magazine.

April 12, 2021

N. Scott Momaday Will Receive Our 2021 Hadada Award; Eloghosa Osunde Wins Plimpton Prize

Every year, the Paris Review Board of Directors gives awards to recognize remarkable contributions to literature. This year, the directors are celebrating two extraordinary writers and taking special steps to ensure the future of exceptional writing. Read on to learn about the ways we are celebrating this year.

The Hadada Award

N. Scott Momaday. Photo: Darren Vigil Gray.

The Paris Review Board of Directors is pleased to announce that N. Scott Momaday is the recipient of the 2021 Hadada Award, presented each year to a “distinguished member of the writing community who has made a strong and unique contribution to literature.” Previous winners include Joan Didion, Philip Roth, and Joy Williams.

Born Navarro Scott Mammedaty on February 27, 1934, Momaday is a member of the Kiowa tribe. He achieved national recognition when his debut novel, House Made of Dawn, won the 1969 Pulitzer Prize. Widely considered a watershed moment for Native American literature, the book’s publication blew open the door for a new generation of writers. In the years since, he has written fiction, poetry, plays, folklore, children’s books, essays, and, most recently, Earth Keeper: Reflections on the American Land (2020), a series of meditations on humanity’s relationship with the natural world. He is also an accomplished visual artist and an ardent climate activist. He has been honored with a National Medal of Arts and an Academy of American Poets Prize, and became a founding trustee of the National Museum of the American Indian, part of the Smithsonian Institution.

Paris Review publisher Mona Simpson said:

The Paris Review editorial committee wishes to honor N. Scott Momaday with the 2021 Hadada Award for his long commitment to, in his words, “the remembered earth.” We respect his originality in all things—he first achieved fame with his novel House Made of Dawn and in the decades since has devoted his attention to poetry, playwriting, painting, and teaching literature. With tenured appointments at Stanford and the University of Arizona, he also taught as an adjunct at the Institute for American Indian Arts. “There is no better blessing than to be believed in,” he writes. Momaday was born and grew up in the American West and remains loyal to this landscape. “Ours is a damaged world,” he writes. “Will I tell my grandchildren, I wonder, of animals they will never see?” At a time when the solutions to the impending climate crisis are calculated and known, and all that’s necessary to save the planet is human commitment, Momaday offers inspiration. “Let me say my heart,” he writes. “Give us one more day and one more.”

Momaday’s relationship with The Paris Review began more than three decades ago, when several of his poems appeared in the Spring 1986 issue. An excerpt from Earth Keeper was published on the Daily this past year, and Momaday’s Writers at Work interview, conducted by the poet Layli Long Soldier, is in progress. When notified about his receival of the Hadada Award, Momaday said: “I am very pleased to receive the Hadada Award for two reasons in particular. First, The Paris Review is an excellent literary journal, and it is certainly a singular distinction to be recognized by it. Second, I am told that my friend Peter Matthiessen, a writer I admired and a recipient of the Hadada Award, could imitate the little-known call of the hadada ibis and did so on request. This remarkable facility, and this prestigious award, inspire me to honor Peter’s memory.”

To celebrate Momaday’s award, a special episode of The Paris Review Podcast featuring an excerpt of his Writers at Work conversation will be released on April 23. From April 19 to April 23, readers will also be invited to stream a special free screening of PBS’s American Masters N. Scott Momaday: Words from a Bear, directed by the Kiowa filmmaker Jeffrey Palmer. Register here.

The Plimpton Prize

Eloghosa Osunde. Photo courtesy of Osunde.

The winner of the 2021 Plimpton Prize for Fiction is Eloghosa Osunde, for her story “Good Boy,” which appeared in the Fall 2020 issue. Named for one of The Paris Review’s founding editors, George Plimpton, the $10,000 award celebrates an outstanding story published by an emerging writer in the magazine in the previous calendar year. Past recipients include Ottessa Moshfegh, Yiyun Li, and Jonathan Escoffery.

Carl Phillips, a member of The Paris Review’s Editorial Committee, said,

“The face of a thing is not the body of it” and “everything in this life is what? Image,” says Eloghosa Osunde’s speaker in her brilliant story “Good Boy.” Making use of that take on morality, our hero thrives financially by helping people deceive others—from offering artfully curated (i.e., fake) Instagram accounts to selling souvenirs that people can use to “prove” they’ve traveled, though they never in fact left home. A queer man in Nigeria, he’s learned that to lie is to survive, including lying to oneself: “necessary fictions,” as another character puts it. Osunde’s story speaks in part to the costs and compromises of those fictions; the other part celebrates the joy of finding the chosen families that allow us to be who we are, in the open, and ultimately to have access to the sacred, in the form of love. “At different times, we were terrified that we wouldn’t find our tribe, we wouldn’t find our people who would see us for us because of what we’d been told to hide … this love shit is holy.” Indeed, it’s holy, and powerful, and, in Osunde’s hands, transformative. I love this story’s vulnerability and its honest handling of joy—celebrating joy without ignoring the complicated psychology that, for so many of us, getting to joy has required.

Osunde is a Nigerian writer and multidisciplinary artist whose writing has appeared in Guernica, Catapult, and Berlin Quarterly. She is a 2019 Lambda Literary Fellow, a 2020 MacDowell Fellow, and the 2021 prose judge of Fugue Journal’s annual writing contest. Her visual art has been exhibited widely and featured in Vogue, the New York Times, and Paper Magazine. Osunde also writes a column for The Paris Review Daily, Melting Clocks, in which she takes apart the surreality of time and the senses. Her first work of fiction, VAGABONDS!, is forthcoming from Riverhead in 2022.

Upon learning that she had won the Plimpton Prize, Osunde said:

As soon as I knew what the Plimpton Prize was, I wanted it. As soon as that was clear to me, I wrote it down in my journal where I make these things plain without shame, then left it alone. This story was a breakthrough for me, because it was the first to come through after VAGABONDS!—my debut work of fiction, which relocated me to a place where imagination meets courage. It means so much to me that a story I wrote from a true place, an empowered place, with a protagonist like the one who powers this story—Nigerian, queer, beautiful, troublesome, stubborn, fearless, flawed, loved, loved, loved—gets to meet many more readers. I hope this opportunity means “Good Boy” will get to continue as it has done since the beginning of its life; that it keeps moving readers to envision new ways to be and belong, whatever that might look like for them. Thank you to the judges for this honor; to Emily and Hasan, the incredible editors who worked with me to shape this story; and to the people who make up my heart, my family, my life, because my imagination is always made larger and richer by their love.

In commemoration of this year’s Plimpton Prize, we will present a conversation between Osunde and the artist and writer Akwaeke Emezi, introduced by The Paris Review’s managing editor, Hasan Altaf, on our YouTube Channel on April 27 at 6 P.M. Click here to register for reminders about this event.

The Southern Prize for Humor

In 2021, the Editorial Committee elected to donate the $5,000 usually awarded to the winner of the Terry Southern Prize for Humor to an organization providing financial support to the writing community during a time when funds for the arts are in particularly short supply. The directors are proud to donate the $5,000 to Teachers and Writers Collaborative in New York.

Teachers and Writers (T&W) is one of the longest-running and most respected organizations to provide arts education to children, by bringing professional writers into public school classrooms during the school day. To learn more about T&W leadership and programs, visit their website: https://twc.org/about.

Events!

April 19–April 23

For the week of April 19, readers will be invited to stream a special free screening of PBS’s American Masters N. Scott Momaday: Words from a Bear, directed by the Kiowa filmmaker Jeffrey Palmer. Register here.

April 23

Tune in to a special episode of The Paris Review Podcast featuring an excerpt of Momaday’s Writers at Work conversation.

April 27

Watch a conversation between Eloghosa Osunde and the artist and writer Akwaeke Emezi on our YouTube Channel on April 27 at 6 P.M. Click to register for reminders about this event.

April 9, 2021

Staff Picks: Comma Splices, Nice Zones, and Ladies Alone

Nona Fernández. Photo: Sergio Lopez Isla. Courtesy of Graywolf Press.

There is an incantatory quality to Nona Fernández’s The Twilight Zone, a feeling of walking, as though under a spell, and then accidentally tripping into the murky unknown. Translated from the Spanish by Natasha Wimmer, the novel traces the reverberations of Pinochet’s dictatorship throughout Chilean life from the eighties to the present day, using pop culture—in particular the television series The Twilight Zone, though Ghostbusters, Billy Joel, and the Avengers movies are also invoked—as a jumping-off point. This is a brilliant move: when reality features frequent disappearances, torture, and televised interviews with the military members who committed these atrocities, it becomes its own kind of dark fiction. “I wonder how we’ll tell ourselves the story of our times,” the narrator thinks at one point. “Who we’ll leave out of the Nice Zones in the story. Who we’ll entrust with control and curatorship.” —Rhian Sasseen

A Fairly Honourable Defeat may or may not be the book that an Iris Murdoch fan would recommend to get a reader started, but sometimes these things are decided for you, and this robust, devastating novel has set me on my own Murdochian evangelism. A Fairly Honourable Defeat begins with Hilda and her husband, Rupert, discussing the strength of their union; it concludes with Simon and Axel discussing the strength of theirs. In between, there is manipulation, doubt, and betrayal, alongside lengthy debates about good and evil. As though I were watching a play, I was immediately pulled into the lives of these frustrating, flawed characters, and distraught not to be able to intervene as their tragic fates were sown and reaped. It’s a meaty book that breezes by but lingers long enough for you to get your hands on more Murdoch. —Lauren Kane

Sterling HolyWhiteMountain. Photo courtesy of Sterling HolyWhiteMountain.

Rarely have I read a story that delights in punctuation as much as Sterling HolyWhiteMountain’s “Featherweight,” in the April 5 issue of The New Yorker: the exuberant exclamation marks, the trippy comma splices and ellipses, the suspended hyphens in “long nights, two- or three- or four-times-in-a-night nights.” For this reader that would have been more than enough on its own, but “Featherweight” is a remarkable story, with a light touch that befits its title; it’s not until you reach the end that you realize how far HolyWhiteMountain has brought you—and then you go back to the beginning to see if you can figure out how he did it. I still haven’t—like the best stories, this one reveals little of its seams or scaffolding, but it is a delight to read, and the writer one to watch. —Hasan Altaf

NoBudge is a streaming platform like no other. The name comes from “no budget,” as in no-budget filmmaking, but NoBudge also calls to mind the idea of no compromise, which is indicative of its mission to curate and champion truly independent works of cinema. You might like Naz Riahi’s award-winning Sincerely, Erik, a short about a bookseller’s struggle to connect with his patrons. Or Dan Arnés’s Please Enjoy Your Stay, a surreal comedy about a musician who can’t seem to check out of his hotel room. Or Caleb Johnson’s Joy Kevin, a keyed up hour-long drama anchored in an artist couple’s disdain for their too-small apartment. If NoBudge were a friend you’d made during grad school, they would probably live in a too-small apartment and be a bit awkward at social gatherings. They would be the kind of friend who pulls you from a conversation to introduce you to someone you might never have met otherwise, someone who would take up your hand and shake up your heart. And then you and NoBudge might not see each other for a while. Because maybe it’s blockbuster season. But you might check in on them one quiet evening in your own too-small apartment. Because they always have something important to say. And aren’t you wondering how they’ll manage to say it? —Christopher Notarnicola

A lot has been said about letter writing in the past year, so I’ll refrain from waxing poetic. For now, I’ll just say this: it’s as great as all those articles claim it to be. I’m fairly certain my pen pal would agree. We’ve been corresponding almost exclusively by mail for years; our addresses change, but the notes keep coming. My pen pal, an avid art lover, sends me postcards featuring famous portraits of solitary women (think Hopper’s Automat, Sargent’s Madame X). I write back, illegibly, with whatever stationery is on hand. Recently, to add to the arsenal, I ordered a box set of postcards from The Believer. I didn’t look too hard at its contents before purchasing; I love The Believer, and the postcards feature art and words from the pages of the magazine. I was pleasantly surprised, however, when the set arrived and I learned that its contents play host to more than a few women reveling in their solitude. Among the many: a woman smiling under a beach umbrella, legs unshaven and sunglasses big and bug-eyed; a woman lying on the floor, legs propped up against the wall while she listens to records; a woman sitting outside her Airstream, camping in a desert, with the neon lights of some city glowing in the background. Plenty of options to counter my dear friend’s seemingly endless supply of lone ladies. If alone time isn’t your thing (or if you’re a bit sick of it after this year), don’t worry: the set includes a great variety of content from The Believer—excerpts from comics, previous covers of the magazine, and lines pulled from poetry and interviews. There’s a little something for everyone. Is your pen pal an animal lover? Check in on their pets alongside a drawing of a couple of monkeys and a turtle. A poet? Ask them how the work is coming, accompanied by a line from Natalie Diaz. A gardener? Celebrate the arrival of spring with a rendering of potted plants. There’s a great assortment to choose from, and I bet there’s at least a few your pen pal will love. —Mira Braneck

An assortment of postcards from The Believer’s box set.

Poets on Couches: Carrie Fountain Reads Maya C. Popa

National Poetry Month has arrived, and with it a second series of Poets on Couches. In these videograms, poets read and discuss the poems that are helping them through these strange times—broadcasting straight from their couches to yours. These readings bring intimacy into our spaces of isolation, both through the affinity of poetry and through the warmth of being able to speak to each other across distances.

“Letters in Winter”

by Maya C. Popa

Issue no. 236 (Spring 2021)

There is not one leaf left on that tree

on which a bird sits this Christmas morning,

the sky heavy with snow that never arrives,

the sun itself barely rising. In the overcast

nothingness, it’s easy to feel afraid,

overlooked by something that was meant

to endure. It’s difficult today to think clearly

through pain, some actual,

most imagined; future pain I try lamely

to prepare myself for by turning your voice

over in my mind, or imagining the day

I’ll no longer hug my father, his grip

tentative but desperate all the same.

At the café, a woman describes lilacs

in her garden. She is speaking of spring,

the life after this one. The first thing

to go when I shut the book between us

is the book; silence, its own alphabet,

and still something so dear about it.

It will be spring, I say over and over.

I’ll ask that what I lost not grow back.

I see how winter is forbidding:

it grows the heart by lessening everything else

and demands that we keep trying.

I am trying. But oh, to understand us,

any one of us, and not to grieve?

Carrie Fountain is the author of three books of poetry, most recently The Life, and serves as poet laureate of Texas.

April 8, 2021

Untitled, No Date

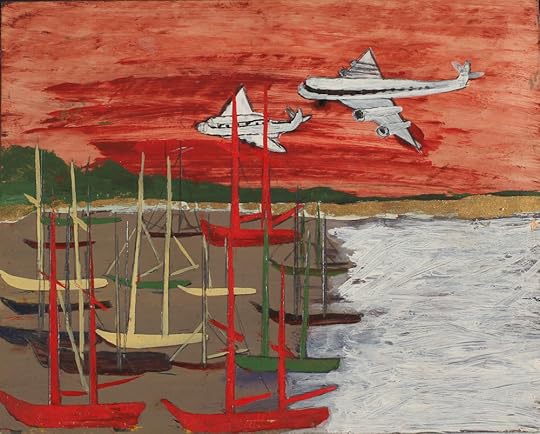

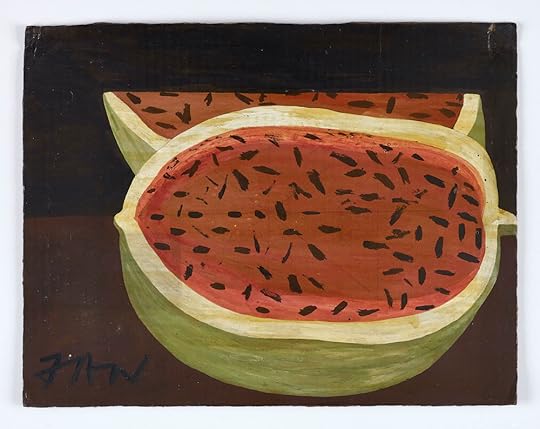

As is the case with far too many artists, the multitalented Frank Walter (1926–2009) did not receive his due during his lifetime. By all accounts a polymath—his second cousin recalls that “as a child, he’d sit us down under a fruit tree, and while he’s typing on one subject matter, he’s lecturing us on other matter”—Walter spent much of his life in relative solitude on Antigua, with his ideas and memories to keep him company as he painted, drew, wrote, sculpted, captured photographs, made sound recordings, and fashioned toys. He brimmed with a restless creativity; he left behind some five thousand paintings, two thousand photographs, fifty thousand pages of writing across various genres, and much more. A new exhibition featuring a fraction of this work will open at David Zwirner’s London gallery on April 15. A selection of images from the show appears below.

Frank Walter, LANDSCAPE Untitled (Airplanes over boats in harbor), n.d. © Courtesy Kenneth M. Milton Fine Arts. Image courtesy of Kenneth M. Milton Fine Arts and David Zwirner.

Frank Walter, Untitled (Watermelon), n.d. © Courtesy Kenneth M. Milton Fine Arts. Image courtesy Kenneth M. Milton Fine Arts and David Zwirner.

Frank Walter, Untitled (black birds in foreground with white bird on a shark), n.d. © Courtesy Kenneth M. Milton Fine Arts. Image courtesy Kenneth M. Milton Fine Arts and David Zwirner.

Frank Walter, Untitled (Abstract Triangles Red, Yellow, Black and Silver), n.d. © Courtesy Kenneth M. Milton Fine Arts. Image courtesy Kenneth M. Milton Fine Arts and David Zwirner.

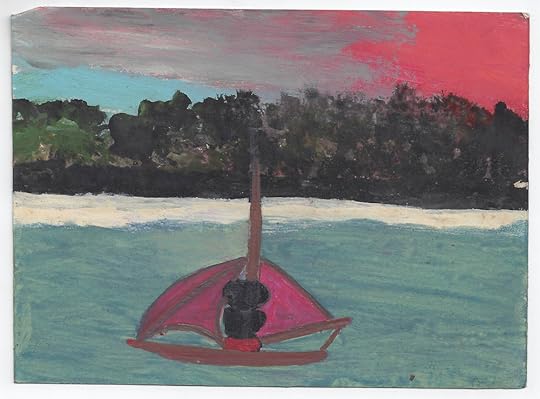

Frank Walter, FIGURATIVE Untitled (Self-portrait on water with red hurrican sky moving in), n.d. © Courtesy Kenneth M. Milton Fine Arts. Image courtesy Kenneth M. Milton Fine Arts and David Zwirner.

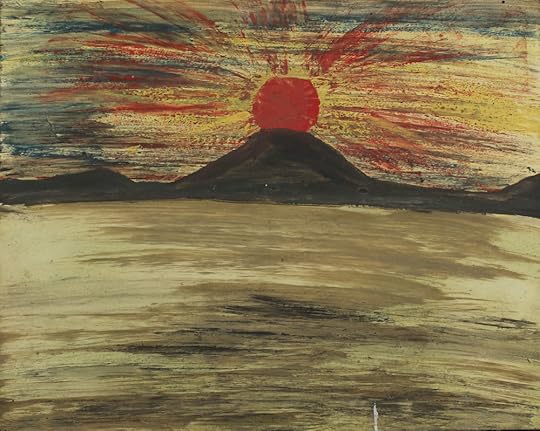

Frank Walter, Untitled (Red sun, black mountain, grey sea), n.d. © Courtesy Kenneth M. Milton Fine Arts. Image courtesy Kenneth M. Milton Fine Arts and David Zwirner.

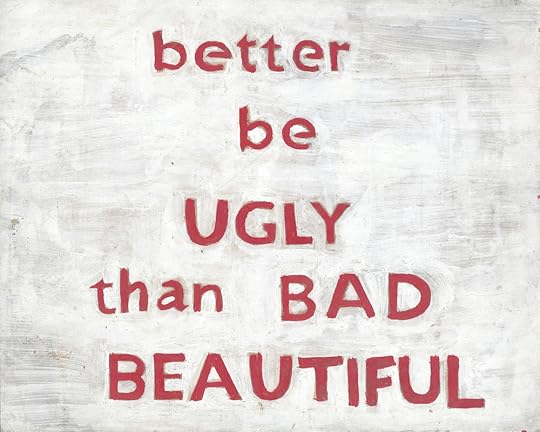

Frank Walter, Better be UGLY than BAD BEAUTIFUL, n.d. © Courtesy Kenneth M. Milton Fine Arts. Image courtesy Kenneth M. Milton Fine Arts and David Zwirner.

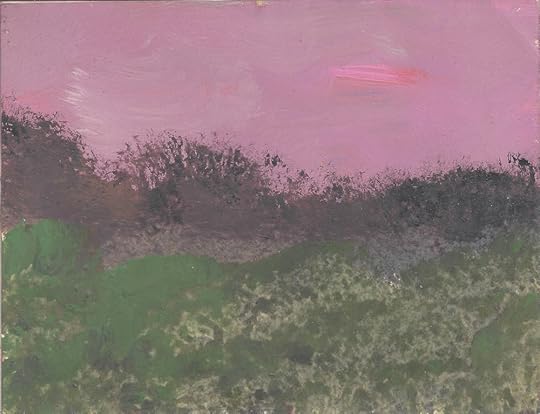

Frank Walter, Untitled (Pink and lavender sky with green foreground and brown plantings), n.d. © Courtesy Kenneth M. Milton Fine Arts. Image courtesy Kenneth M. Milton Fine Arts and David Zwirner.

“Frank Walter” will open at David Zwirner’s London gallery on April 15.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers