The Paris Review's Blog, page 122

March 9, 2021

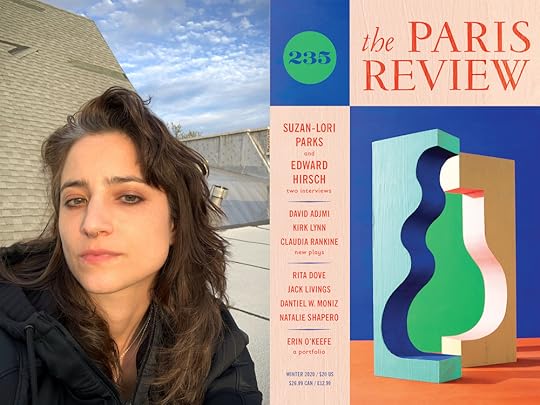

Language Once Removed: An Interview with Sara Deniz Akant

Sara Deniz Akant.

There’s something special these days about a phone call. A particular kind of listening happens when you’re not watching faces on a screen or coping with the internet connection but instead focusing just on the voice on the other end of the line. Sara Deniz Akant is a poet whose ear is especially attuned to disembodied voices, whether they be documents from long ago or the memory of her mother’s singing.

As a result, so many of Akant’s poems feel alive with multiple speakers, though they are playfully mysterious characters. Her collection Parades (2014) sent me to my old Latin reference books, but in vain. Everything I recognized was not quite what I’d thought, a familiar ancient sound slightly muddled on its way to the twenty-first century. The poems in Babette (2016) are also deft explorations of meaning that toggle between their own lexicon and one you can translate. Akant’s two poems in the Winter issue of The Paris Review are just as convivial, with voices fading in and out of focus. It’s tempting to say her process is about acting more as conductor or clairvoyant than as poet, but at the same time, Akant speaks about days spent writing in her spare office with an academic’s clear articulation about everything from research to how to recognize the end of a poem to the perks of living between languages.

Throughout our telephone conversation earlier this year, Akant and I discussed how one’s own language can linger in notes until it becomes like the voice of someone else, how marginalia can mingle with text, and the creative boundaries of word processing.

INTERVIEWER

Can you remember what first sparked your interest in literature?

SARA DENIZ AKANT

I was forced to memorize and sing poems in grade school, and I think just having all of that language set to music was pretty influential. Also, my mom would walk around the house singing songs, and singing the wrong words to them. There was one about a sinking ship called “The Golden Vanity.” And my grandfather would sing to me in Turkish—for example, “Fış Fış Kayıkçı,” a nursery rhyme.

But I mark in my mind one particular moment in retrospect, because at the time, I certainly wasn’t thinking that real people were writers. One year I got really sick, and I stayed home from school for a few days and had all these fever dreams—I called them “voices in my head.” That’s the origin of my feeling, for the first time, like a writer. In my mind, there’s the fever dream time, and then I dabbled in it until I was twenty-one or twenty-two and taking a class called Poetry in the Present during my last semester of college. It was a small seminar taught by Anselm Berrigan. We mostly read New York School poets. I was really moved, and everything kind of fell out in front of me. I didn’t have any other plans after college, and so I found this passion in the last moment.

INTERVIEWER

I’m not surprised to learn that you attribute your first writerly impulses to this dream moment. I think of your work as very voice-driven or language-driven.

AKANT

I always think of it as language once removed—it’s just a little slant. My dad speaks a number of languages, and he doesn’t really have an accent, but he still communicates certain words and phrases in a peculiar way. Having all of those different languages and sounds—and then also being a little dyslexic on top of that—generates sound-based ditties in my head. I went to speech therapy when I was younger because I had trouble saying things out loud in the correct way. My mouth couldn’t make the words come out. And so when I started actually writing poems, there was so much internal language, and all these strange, unused sounds tumbled out. Things unsaid, not-quite-real sounds—they were suddenly just available.

INTERVIEWER

What makes you want to take that language and shape it into a poem?

AKANT

Speaking was hard, but reading was also hard. At a certain point, I realized that reading was really overstimulating. So I started reading in this creative way where I let my thoughts be associative and distracted—I let myself read things incorrectly. I still have a habit of picking up a book and moving from the back of it to the front. I was just doing that the other day, and I was like, Why do I still do this? But the linearity of the page is really hard for me, so learning about cut-ups and collage in contemporary writing allowed me to be like, Oh, there’s this word, and it looks like this word, and now I’m remembering a story, and actually I’m seeing this other word inside the word, and so I’m going to write that word instead.

INTERVIEWER

Has your way of coming to a poem changed?

AKANT

My early poems were produced out of a sense of error on the page, or some flicker of language I would see as I was reading, or something I heard or misheard. But I also was really interested in building characters. I liked the way a character could emerge from language play and then build its own narrative. All of that is still part of my practice, and when I get too far away from it, I feel a little lost. I guess what’s changed is I’ve grown out of the neologisms, if you want to call them that—they were part of a certain skill set I had at that moment, and maybe it’s still there, but I’m less interested in it. I think now, I’m slightly more intentional, which makes everything more difficult. It’s not the younger energy of putting all these words on the page and seeing what happens. It’s more taking notes all the time and working toward getting something to emerge on the page.

INTERVIEWER

Does it feel more satisfying to be more intentional?

AKANT

Maybe intentional isn’t the right way of putting it. With the earlier books, what I was really interested in was writing sci-fi-esque poems and accessing that liminal space I felt throughout childhood but didn’t really have words for. I was interested in accessing that by creating something sort of scary. I liked the internal language in my head and collaging it with other voices or with my family, but I actually wanted it to be hermetic. I liked it to shock people into feeling like, Oh, wow, I really don’t know where this came from. I still want that intimacy of the internal language and the connection I’m building with the stories I’m throwing on top of each other, but these days I’m more interested in reaching out than retracting. Whereas I think in the earlier work, it was like, I’m all the way over here, and you could never reach me. I liked that sort of loneliness.

INTERVIEWER

In your collection Parades, you make use of things like characters or marks down the page, em dashes filling up a line. What do these bits of typographical play signify to you?

AKANT

I love thinking about the limitations of a Word document. What do I have on a keyboard that I could use to try to add to language or build it in a different place? I wanted more—more distance but also more visual cues, more information that wasn’t necessarily semantic. You know that thing in an email where you don’t quite know how to end it, and you don’t want to say “best” because that’s boring, and you don’t want to say “all best” because that sounds weird? With people I knew well enough, I started just putting colon, colon, slash. It’s like an emoji that’s not directly translatable. I like experimenting whenever I put language on the page. I remember spending hours moving a colon around, trying to decide where it went, and at a certain point realizing like, Huh. Other people aren’t doing this. Am I wasting my time? But I liked it. I liked the lo-fi aesthetic. What can a keyboard do without trying too hard, without going and finding a preexisting image? What can I just make with these symbols?

INTERVIEWER

Do you have a particular writing method or technique or rhythm? How do you go about getting ready to write?

AKANT

I use my iPhone notes a lot. It’s just what I have in front of me. The notes are just where I dump things. I don’t know when I do it. Sometimes it’s like, Oh, let’s open up a note on my computer and see what comes out. But most of the time, it’s just that things collect there. It happens a lot more when I’m moving around or traveling for some reason—not now, because of COVID-19—taking a bus or just in a new place or feeling dislocated. Whenever I go to Turkey, for example, all of this writing flows out, or into the notes, let’s say. I don’t think this was necessarily my process a while ago. But now I have these notes that I then create out of. It’s a little retroactive, but I guess it gets fused with whoever I am that day. I was recently using notes that I definitely wrote a long, long time ago. So I don’t necessarily remember what the emotions or experiences around my notes were. It’s just material that I get to reinfuse with my current interest, current mood, current desires or intimacies. I also use notes in the margins of books while I’m reading—mostly my own but also sometimes notes made by others in used copies. The marginalia build a narrative adjacent to the narrative.

INTERVIEWER

How do you decide when you’re done with a poem?

AKANT

I struggle with the question of closure. I do love that chill at the end when you think, Ah, it’s done! Now everything’s opening up in front of me, and I have to go and think about it. So I guess a poem feels done when I reach that moment—when I’m sufficiently scared or a little uneasy. I used to think of poems as their own thing. It’s just this one poem, and this is the world that it lives in, and this is what it does. But I’ve started thinking more of poems in relation to other poems. Like, even if this thing is done, it’s just continued in the next one. The ending of a poem isn’t stressful because there isn’t anything that’s really ending. It’s just this section, or it’s just this moment. And at some point I feel like I’ve reached an emotion that is new or frightening enough for me to disappear for a bit.

INTERVIEWER

What are you working on now?

AKANT

I’m working with family documents, family archives that are pretty sparse. It’s a challenge. I don’t even know if poem is the right word. Projects? Spaces? Moods, characters? I’m trying to create stuff out of that material. I have these really dry documents right here on my desk today. For example, this one reads, “He who has read this speech with great interest on the continental shelf, please allow me to close some material.” When I said I would misread or mistranslate what I saw on the page and then create, I was working with language that was a lot richer. It’s a challenge to see if I can use this much drier, dustier material. It’s also hard because it’s family stuff, so it feels different. It’s not that surreal gesture of, Oh, I’m going to just use this material like it’s paint on the page. I’m forced to insert myself back into a place where I was already semi-existing. There are traces of me in that debris. So whatever I built around myself in this world or in the poem, it’s a different kind of perverse growth, a new uncanny process.

Lauren Kane is a writer who lives in New York. She is the assistant editor of The Paris Review.

Read Sara Deniz Akant’s poems “Dracula, by Marriage” and “Bruce Baba,” which appear in the Winter 2020 issue.

March 8, 2021

Oh, Heaven

In Eloghosa Osunde’s column Melting Clocks, she takes apart the surreality of time and the senses.

Naudline Pierre, Lead Me Gently Home, 2019, oil on canvas, 96 x 120″. Photo: Paul Takeuchi.

When I say the name Heaven, someone I love answers me through two realms and a time machine. It doesn’t matter where our bodies are in the world, what distance separates us, or what headlines are going on about, I say that name and we appear elsewhere. When we rechristened each other recently, we gave and received three names each. They call me [redacted] or [redacted] or [redacted] and the world stops. I call them Heaven or [redacted] or [redacted] and the Earth’s core shifts. All six of our names have different emotional hefts for me, but I suppose Heaven carries a particular weight. There were borders between us when I chose the name, so they didn’t see the choice in real time, but they know my why. They cried, too, when they first heard it, because they know what this word means to me.

There was a time when I was obsessed with staying saved and helping loved ones get on the road to heaven. I called that love. That level of conviction gave me something to live for, but after I released it, I realized the obsession added indelible bass to my anxiety. Sometimes, when I get still enough, I can still feel the reverb thudding through me. When people die now, though, I don’t see them facing a heated binary, standing before a white light: Heaven or Hell? Instead, I close my eyes and support their spirit in what it believed. I wish for them what they wished for themselves. And beyond that: I imagine with them what they imagined for themselves, or what their spirit would have dreamed of if they weren’t afraid. It’s been this way for years: I see dead people deciding, because a sure thing I know is that every person has a spirit—whether they are awake to it or not—and our spirits have agency, so that we can cocreate our own realities with God.

But I suppose if you’re vanilla about life, the way I think and talk about death in person—openly, vocally, quasi-casually—would be considered morbid. It’s both big and small talk to me, and I do both. Even then, I (still) find myself holding back more than I would if I wasn’t scared of scaring the people I love. Now largely unplugged from religious imaginations of The Afterlife, I know what I am working toward instead. There are implications for what I see as possible beyond death, and those implications double as instructions coded onto my spirit. I accept the challenge without flailing. To get to that thing, that place—my own personal heaven—there’s work I have to do in this lifetime; there are things I have to allow to change me, because when I die, I don’t want to be wished into an eternity I did not conceive, an everlastingness I did not imagine, a heaven that cannot hold me. My loved ones know what I have agreed with God instead. I’m at peace with that.

*

What even is a heaven, anyway? My old faith described it as a place where we are blameless and holy, or God’s dwelling place. I still partly agree. But sometimes, I find, a word weighs you down because you are carrying an impersonal definition. What’s different now is: I believe that God has multiple addresses—inside and outside and beyond and before and after us—and I define heaven as a(ny) site of spiritual rest. When asked what I wanted the most in love, I used to say rest. Rest from pain, rest from hypervigilance, rest from the violent volume of the world. I still mean that. That’s relevant here because we chase heaven, mostly because we’re chasing rest. Sometimes, I’m still so shocked by the absurdity of aliveness I have to slap my own thigh to remember I’m in a body, but that doesn’t change the fact that love lives in my body and I inside God. Because of that, I think of God—as in Love—as heaven, the boundaries that fence my life as heaven, the tenderness weaving through my chosen family as heaven, community as heaven, my dining table as heaven, a home with full acceptance as heaven, the absence of pretense as heaven, right now as heaven.

For months now, I’ve been building heaven into a playlist for my chosen family, as a portal into rest, respite, relief. These are people I commit my life to, people I hold deliberately, and I have always loved them with loss in mind, because love’s a sieve in a sense, I think. Whatever you love will pour through you or you through it. It keeps me careful. It keeps me awake. So, Kokoroko to Obongjayar to Shabba Ranks to Joan Armatrading to Gyptian to Tanerélle to Buju Banton to the Cavemen. Old Tuface meets Dawn Penn meets Nneka meets Flying Lotus meets Duendita meets Sampha meets Florence Welch meets new Wizkid. Through the making of this space, I’ve been thinking a lot about how if love is the surreal location where I can catch a loved one’s head before it rolls off their neck from sheer weight, where they can stroke my wing before I even know I need to cry about the shameful shade it turned, where we can breathe in our spiritual other-bodies, separate from the weight of flesh and hierarchical definitions, then that’s where I want to spend the rest of my life. Heaven is, in the end, wherever we are fully known and fully loved.

*

Naudline Pierre’s work is a place like that. Have you ever met a painting you immediately wanted to climb into because you were sure—you could bet on it with your life—that nothing painful could touch you there? When things get too tiring on this side, I project her work onto the wall in my home, close my eyes, and move to the edge of my body, readying myself from the inside. To live in this world is to have the body be the loudest thing. But there are—and have always been—other just-as-true realms in which we have form. Pierre’s work is a spiritual reality that’s happening right now. It helps me take breaks from whatever hurts, whatever has crushing weight. It helps me remember that to think of the immaterial world, the Other World, as my first address is not escapism, it’s fortification, strength making, muscle memory. Pierre’s work wakes my memory of my inside self, my spirit self, my body beyond flesh, my love with echoes surrounding it. I enter the world she centers and turn immediately celestial. More than myself. Bloodless but multilimbed and massive-winged. I’m spiritually present and cared for. And not just that, but I have kin, people who brush through my heavenly hair, who link their careful arms around each other’s ankles, who cover their loves with full and lush feathers. Hot beams of light pour out of all our heads, our faces haloed by complete love. Inside there, we’re visible, outrageously colorful and unmasked, boldfaced, touching and unsorry. It’s not quite the heaven I grew up believing in, even though that place has its own glorious music, a score. People fall down still, we stumble. I know. We float off into weightless clouds. I see that. But I notice how we’re hardly ever alone. We’re always being caught, upheld, hallowed in this place that goes beyond respite and right into the heart of pleasure for its own sake. I’ve been wondering, then: What if the most exciting thing about that heaven isn’t the colors, or the wings, or our other-bodies, but the relationships, the togetherness, the touch?

*

In 2016, I wrote to one of my favorite people in the world:

Touch is a strange thing.

I’ve always believed that we ought to approach each other with wonder, trepidation, adoration, and a sweet trembling every time, because every body is a mystery. Every body has fears, resentments, passions, worries, excitements, desires stored in them. I’ve always thought that it’s lazy and disrespectful to approach another person’s body, eager to display “acquired experience”—because that comes with a lazy assumption that one already understands what all the other person’s fearsresentmentspassionsworriesexcitementsdesires lead to. But we aren’t taught to consider that. I don’t think of sex or sexual acts as urgent or utterly necessary. It has never been that way for me. But I don’t say those things out loud anymore.

There’s no better way to say it than I’ve had to relearn touch as a walk on a tightrope. I’ve had to give up on being approached tenderly and with reverence, on being touched by a person who isn’t afraid to leave all their senses open. I’d given up on someone who would not only understand silences but would encourage them because they needed them, too. Someone who could, for example, walk by me in the kitchen and not talk to me or pull me in but plant a kiss on the shoulder to register presence, to remind me of hereness and let that be enough. I’ve always wanted to have my hands held or my face traced or my partner’s nose chasing the back of my neck and feel the world explode in my chest. But I learned that people mostly do things like that on their way to a “bigger” act or to something explicitly sexual.

I have wanted attentiveness more than I’ve ever wanted formula.

But bad things come out of trusting the wrong people. So, I create my safe spaces myself because I’m not sure of the possibility of anyone else considering them. I’ve subconsciously adopted certain mainstream desires as my exoskeleton to protect myself. Desire as defense. They’re not necessarily me, but they are bearable until. Endurable, until. They are understood in the accepted language that people who touch each other speak. In a way, it’s sort of like learning a language for survival value because you’re in a foreign land. You don’t want to stick out too much so no one preys on you and hurts you. Or kills you.

*

Many minds later, my favorite way to be touched is like I can be lost. My favorite thing to remember is that something else is always possible. To touch or be touched well, I think, is to remember that people are floorless, cannot be known without being known or mastered at all. We suck at this until we don’t; we fail at it until we learn. Recently, when a lover and I were sat with our feet in the pool, I said, We won’t get to the bottom of us. You can’t get to the bottom of me, because even I haven’t met the bottom of me. I can’t get to the bottom of you, because same. To believe this about myself and others is to keep my senses open. It’s how we stay awake. It’s how we stop waiting for death and give ourselves a chance at heaven. Now.

Reading Cruising Utopia recently, I came across the difference between queer time and straight time. It made all the sense in the world to me. To experience the world through a time stack is to experience queer time and to experience queer time is to spend significant moments in the future and work backward from there. In the future, everything starts and everything ends. Sometimes, I hope from there because change is not just possible but certain. Sometimes I grieve from there because I’m humbled by how little I can control. Meditating on grief affects how I love now, how I touch. That bittersweet spot is where SBTRKT and “Wonder Where We Land” meets Hundred Waters’ “Show Me Love,” for instance. Every day, I think this about the people I love: If I’ve seen what the loss of you has already done to me when you go, what the loss of me has already done to you when I go, how can I not be deliberate about you? If we’ve shattered each other already in tomorrow; if we chose to go deep enough for you to reach me here, for you to mark me this absolutely on purpose, what’s more important than you holding me now? The goodbyes are inevitable, really. But the world is passing, and I’m holding your hand. The world is passing and I’m holding your hand.

To queer time is to love like I believe in our right to not just eternal but immediate rest. To be free is to act from inside a yes I can take for granted, to work toward regretting nothing. I can’t always meet my own standards, because being in a body means my capacity can crumble before my desire. That hurts, but I try to try. The other day, I got a WhatsApp missed call from December 31, 1969. It was a glitch in my phone but I felt touched by the past. One of my parents was eight years old then. Sometimes a memory you weren’t there for grows an arm just to touch you. Other times, possibility finds and peels you open, shows you how wrong you’ve been about what you think is (im)possible. Sometimes, you’re shaken to the core by all the ways your heart surprises your body; by a hand landing on you too correctly, too gently. I’ve been touched like that before. That was heaven and I grew wings, let me tell you. I haven’t lost them since.

Eloghosa Osunde is a writer and visual artist. Her debut work of fiction will be published by Riverhead Books in 2021.

March 5, 2021

Staff Picks: Raisins, Rhythm, and Reality

Allan Gurganus. Photo: © Roger Haile. Courtesy of W. W. Norton.

In his Art of Fiction interview, Allan Gurganus preaches the power of the sentence. But for me, the real satisfaction to be had from the newly released Uncollected Stories of Allan Gurganus comes from the layers: a shrewd grad student’s thrifting trip becomes the story of a portrait, which is actually the story of a tragic moment in a small town’s history; a local news report becomes a firsthand account of the incident told by a police officer to his tape recorder. (In fact, local news reporters are more than once a way of getting into a story; they act as a kind of chorus for small-town America.) Gurganus’s Uncollected Stories is lean, nine extended narratives often broken up by Roman numerals. He is unafraid of the darkness deep inside his characters. These are tales that left me feeling unsettled and newly aware of strangers I encountered, the likely mysteries in their lives—and yes, in awe of excellent sentences. —Lauren Kane

Why are the three musicians who make up the jazz group Thumbscrew so wonderful together? It’s almost as if they shouldn’t be—each has such a distinctive sound on their instrument and such a unique musical sensibility. The band’s guitarist, Mary Halvorson, is all prickles and edges and sharp, sudden turns; the bassist, Michael Formanek, plays somewhere between gloopy and ghostly; the drummer, Tomas Fujiwara, is a wonky miasma of rhythmic hailstones. They are all gluttons for rhythm, for finding all its nooks and crannies. Never Is Enough is their sixth album as a collective, and I think it’s their best yet. Recorded and composed during an extended residency at Pittsburgh’s City of Asylum, this is a tight series of new compositions by a band that is now deeply in sync. The trio breezes and bangs through songs that bubble and squawk and shriek and slide over and around their boundaries. This is aggressive, rock-facing jazz, but it’s not the kind of music that makes you want to cover your ears from the inside—it manages to be heavy, intellectually stimulating, and relaxing all at the same time. Plus, the vinyl version comes with a little live EP on the fourth side. —Craig Morgan Teicher

Terry Waite. Photo: James Gifford-Mead. CC BY-SA 4.0, (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...), via Wikimedia Commons.

Terry Waite was released in November 1991. He had been held hostage in solitary confinement in Beirut for 1,763 days, and his release dominated the news in Britain to such a degree that even eight-year-old boys like me couldn’t help but take notice. His name and face, and particularly that image of him waving from the door of an airplane when he arrived home, were familiar to everyone, and deference to this unassuming man became part of my generation’s cultural inheritance. Growing up, I often saw the best-selling account of his imprisonment, Taken on Trust, on bookshelves back home, though I never read it. Something about this pandemic brought him to mind, however, and I found myself ordering it one lazy afternoon. Last weekend, the book arrived on my doorstep, and I’ve barely left my comfy chair since. It’s a remarkable story, though distressing, of course. Waite had been in Lebanon to negotiate the release of other prisoners and in the process was taken hostage himself. Taken on Trust, it seems, was written in his head while he was in prison—a remarkable literary achievement—and the scenes alternate between memories of his previous life and his years in captivity. It’s a testament to his skill as a writer that the everyday scenes never feel like they’re getting in the way of the main event, and there are many moments of quiet poignance in both of these disparate parts of his life. He resists entirely the temptation to sensationalize. Reading Taken on Trust, I’m reminded of Lionel Trilling’s statement on Orwell: “He communicates to us the sense that what he has done, any of us could do.” But this, of course, is merely an act of generosity on Waite’s part: most of us would not be able to endure as he did. And very few of us, when first stepping back onto home soil, would still be possessed of the good manners to thank the assembled crowd for having braved the drizzle on that soggy English day. Gosh, what a thoroughly decent fellow he seems to be. —Robin Jones

This week, I’ve been reading Jenny Hval’s Girls against God, translated from the Norwegian by Marjam Idriss. It’s a strange book, and I can’t quite pin it down. Witchcraft, girl bands, and black metal abound. On one page, it’s a diatribe against small-town life in southern Norway; the next, it’s a criticism of canonical practices in high art. Is it horror? A surreal dreamscape? A feminist manifesto on art and culture? All of the above. The book knows no bounds—in subject matter, genre, or possibility. It moves in and out of time, between the real and surreal. Hval seeks to dispel divisions, collapse binaries, and make space for something new. To nullify the reader-writer divide, the narrator turns and addresses us directly. She calls us in: “Don’t try to follow me,” she says, “just close your eyes.” I don’t try to follow. I’m just along for the ride, trailing Hval’s various whims as she pokes and prods me onward. I keep reading and wait to see where we end up. —Mira Braneck

Raisin meditation is a mindfulness practice in which the practitioner eats a single raisin, essentially, but not before examining the raisin’s every conceivable aspect—its little raisin ridges, its rich raisin history, its aromatics, its weight, its raison d’être! The result is often a greater understanding and appreciation of the subject, followed by, after much practice, a heightened awareness of life’s other overlooked details. Such has been my experience with The Anatomy of Melancholy, by Robert Burton, who trained his mind not on the sun-dried grape but on gloom, or what we might call depression. First published in the seventeenth century, the book is an exhaustive exploration of melancholy in its many manifestations, causes, and cures as told by Democritus Junior, a speaking persona whose namesake was an early proponent of atomism—the explanation of complex phenomena in terms of a collection of indivisible parts. The navigation of such an atomistic approach requires a kind of wanderer’s spirit, as our speaker admits: “So that as a river runs sometimes precipitate and swift, then dull and slow; now direct, then per ambages; now deep, then shallow; now muddy, then clear; now broad, then narrow; doth my style flow.” My efforts have taken me through nearly a third of Burton’s pages—a thousand or so to go—which is to say I have only just begun to go with the flow, to weave through the book’s rocky raisin valleys, to press against its tender edges, to hold it to the light and appreciate the delicate translucency of its flesh. Never has melancholy seemed so meditative. —Christopher Notarnicola

Gilbert Jackson, Robert Burton (detail), 1635. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

The Fabric of Memory

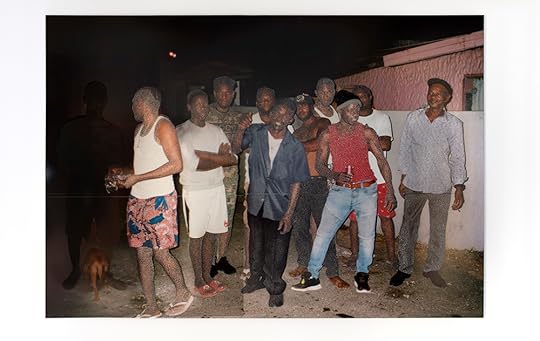

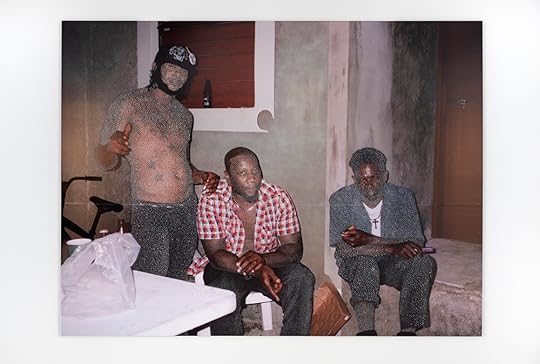

In Paul Anthony Smith’s Untitled (Dead Yard), a figure stands with arms outstretched in the midst of a haze of ghostly breeze-blocks. The physical appears to commune with the spiritual; unreality encroaches on the real. It’s a startling effect, one that persists throughout Smith’s second solo show with Jack Shainman Gallery, “Tradewinds” (on view through April 3). Using a needled wooden tool, Smith painstakingly works over his photographic prints, puncturing the surface and chipping away at the ink. Each stipple, each architectural flourish laces the images with the fabric of memory. This is not reality; this is the world in recollection, the white noise of time and distance always threatening to drown out the past. A selection of images from “Tradewinds” appears below.

Paul Anthony Smith, Breeze off yu soul, 2020–2021, unique picotage with spray paint on inkjet print, mounted on museum board and Sintra, 40 x 54″. © Paul Anthony Smith. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Paul Anthony Smith, Dog an Duppy Drink Rum, 2020–2021, unique picotage, spray paint, and acrylic paint on inkjet print, mounted on museum board and Sintra, 72 x 104″. © Paul Anthony Smith. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Paul Anthony Smith, Islands #3, 2020–2021, unique picotage with spray paint on inkjet print, mounted on museum board and Sintra, 60 x 40″. © Paul Anthony Smith. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Paul Anthony Smith, Untitled, 2020–2021, unique picotage and acrylic paint on inkjet print, mounted on museum board and Sintra, 68 x 96″. © Paul Anthony Smith. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Paul Anthony Smith, Yaad Star, 2020–2021, unique picotage with spray paint and gouache on inkjet print, mounted on museum board and Sintra, 60 x 40″. © Paul Anthony Smith. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Paul Anthony Smith, Untitled, 2020–2021, unique picotage with spray paint on inkjet print, mounted on museum board and Sintra, 40 x 60″. © Paul Anthony Smith. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Paul Anthony Smith, Untitled, 2020–2021, unique picotage, spray paint, and acrylic paint on inkjet print, mounted on museum board and Sintra, 72 x 96″. © Paul Anthony Smith. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Paul Anthony Smith, Who JAH bless…, 2020–2021, unique picotage on inkjet print, mounted on museum board and Sintra, 60 x 40″. © Paul Anthony Smith. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Paul Anthony Smith, Untitled (Dead Yard), 2020, unique picotage on inkjet print with spray paint, mounted on museum board and Sintra, 95 7/8 x 71 7/8″. © Paul Anthony Smith. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Paul Anthony Smith, Untitled, 2020–2021, unique picotage with spray paint on inkjet print, mounted on museum board and Sintra, 60 x 40″. © Paul Anthony Smith. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

“Tradewinds” will be on view at Jack Shainman Gallery’s 513 West Twentieth Street location through April 3.

March 4, 2021

Sheri Benning’s “Winter Sleep”

The Spring 2021 issue, which went live earlier this week, features three poems by Sheri Benning. One of these poems, “Winter Sleep,” serves as the basis for a short film of the same name. Shot in the Rural Municipality of Wolverine Creek in Saskatchewan, t he project is a collaboration between Sheri and her sister, the visual artist Heather Benning, along with the filmmaker Chad Galloway.

~Hope.docx

Sabrina Orah Mark’s column, Happily, focuses on fairy tales and motherhood.

An illustration from Jack and the Beanstalk, Elizabeth Colborne

I am cleaning my house when I receive a Facebook message from the manager of Project Safe that a volunteer has found my plague doctor, or someone who looks like my plague doctor. The baseboards are thick with dust. I spray a mix of vinegar and lavender, and run a rag across them. The plague doctor, or someone who looks like my plague doctor, has been put aside in the office for me. I write back, “Oh! oh! I hope it’s him.” The rag is black. I am on my hands and knees. “I hope it’s your doll!” writes the manager. “Fingers crossed,” I write back. “It has to be him,” I say to no one. “It just has to be.”

I text my mother, “I’m cleaning the gustroom.” I notice the mistake before I hit send, but I send it anyway. She calls. I pick up. “Shouldn’t you be writing?” she asks. I should. “I can’t move,” says my mother. She received her second dose of the vaccine yesterday and now she’s having a reaction. I tell her I’m writing about hope. I tell her the reaction means the vaccine is working. “I feel like I’ve been hearing about this essay on hope for weeks,” she says. She’s impatient. “I can’t lift my arm,” she says. I tell her I’ve read every version of “Jack and the Beanstalk” I could find because I thought if I followed the hunger and the despair and the cow traded for a pocketful of magic beans and the beanstalk that grows overnight through the clouds and the boy named Jack who climbs the beanstalk and robs a giant of his harp and hen so he and his mother could live happily ever after I could make a beautiful map of hope because isn’t that what we need right now? “Isn’t what what we need right now?” “Hope,” I say again. “A map of hope,” I say again. “Hope?” says my mother, like it’s the name of a country she’d never pay money to visit. “What we need is a hell of a lot more than hope,” she says. We’re both quiet for a minute. “How’s the essay going?” asks my mother. “Terribly,” I say. “No surprise,” she says.

I tell her the manager of Project Safe just messaged me that a volunteer thinks she might’ve found my plague doctor, or someone who looks like my plague doctor. “Here we go again,” says my mother, “with the plague doctor.” I lost him months ago, and now he’s coming home. “Why couldn’t she just send you a photo?” I was wondering that, too, but I don’t admit it. If it’s not my plague doctor I want to at least postpone the time in between the darkness and the figure who emerges. “There’s no way it’s your plague doctor,” says my mother.

“Fee-fi-fo-fum,” I say. “What?” she says. “I said ‘feel better,’ ” I say.

In some versions of “Jack and the Beanstalk,” each time Jack climbs the beanstalk his mother grows sicker and sicker. And in other versions, each time Jack climbs back down and shows his mother his gold and tells her he was right about the beans after all, his mother grows quieter and quieter until it’s impossible to know if she’s even there anymore.

I go to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s website. I click on the IF YOU PLANT THEM OVERNIGHT BY MORNING THEY GROW RIGHT UP TO THE SKY link. I want a vaccine, but what I want even more are magic beans I can plant in my arm that will grow into a beanstalk my sons can climb if they ever run out of hope. I click on the link but it just leads me to a page on “adjusting mitigation strategies.” I try to click back, but I can’t. My computer freezes. I have to restart, and when my computer turns back on, and I return to this essay on hope, I realize it wasn’t properly saved. Most of it is lost. Only a few old notes, like branches, are scattered across the page. I start to cry, and tell my husband I’m giving up writing forever, and then I kick the air, and then I watch tutorials on recovering documents that advise me to search for “hope” with a “~” in front of it. What is that called? A tilde? It looks like a downed beanstalk.

A tilde means “approximately” and it also means an exhausted sigh, like being almost not there, which is the hopeful state I am in when I type the tilde next to hope, which is the name of the lost document. In Hebrew hope is tikvah, which means a braided rope or a cord or something you could climb up or climb down, I suppose, like a beanstalk. The tilde could be mistaken for a cutting from a tikvah, a cutting I can’t imagine being long enough to ever get me anywhere. If I could pinch it off the screen and throw it out the window I would.

Had I turned on Time Machine I could have recovered my unsaved document, but I didn’t even know there was a Time Machine, and so I never turned it on.

In most versions of “Jack and the Beanstalk,” at the top of the beanstalk is not the giant’s house but dust, a barren desert. There are no trees, or plants or living creatures. Famished, Jack sits on a block of stone and thinks about his mother. In Benjamin Tabart’s “The History of Jack and the Bean-Stalk” (1807), when Jack gets to the top of the stalk he looks around and finds himself in “a strange country … Here and there were scattered fragments of unhewn stone and at unequal distances small heaps of earth were loosely thrown together.” At the highest point of hope is a long empty road. At the top of the beanstalk is dirt that lies fallow so a world can regenerate.

The first known printing of Jack is “The Story of Jack Spriggins and the Enchanted Bean” (1734), which is ascribed to a certain Dick Merryman, who writes he got most of the story from the chitter chatter of an old nurse and the maggots in a madman’s brain. What grows a fairy tale in Merryman’s brain is made out of larva and babble, and what’s at the top of the beanstalk is a giant named Gogmagog, which sounds like a boy trying to say the word God but he can’t because his mouth is filled with dust.

Project Safe is only a five minute drive from my house. It’s bright and warm, and greener than it should be in February. The five minute drive feels too short. Shouldn’t my hope and the fulfillment of my hope be farther apart? Shouldn’t it take my whole life to drive to Project Safe? My heart is beating fast. I park and go inside. I go past the racks of donated clothes, and coffee mugs, and old couches, and books. My heart is beating faster. I can already feel the weight of my plague doctor’s small porcelain body in my hand, his soft velvet coat. I want to call out “I’m here!” because I’m once again close enough to the plague doctor for him to hear me. “I’ve come at last!” I want to sing. And then I see her. I see the volunteer who found my plague doctor or someone who looks like my plague doctor. She knows it’s me. She looks like my stepdaughter. She knows I’ve come to retrieve what I’ve lost. “It’s in here,” she says brightly. I follow her. She smells like oranges, and her smile is so beautiful. She leads me to a back office filled with bags and bags of donations. “Wait here,” she says. I wait and in my waiting I know something is wrong. She returns too quickly. There is too little dust. What the volunteer is holding is not my plague doctor. It’s a mask of a plague doctor, and this mask is the size of my face. I don’t know if it was wooden or plastic because I back away from it immediately and say something like “no” or “thank you for trying” or “he is much smaller and he has arms and legs.” I wave goodbye to the volunteer as if I am in the ocean and she is on the shore instead of where we really are which is standing barely ten feet apart in the back room of a thrift store.

On my way out the door, I stop because I notice a small rusted harp leaning against a ceramic brown hen with a crack running along one wing. I bring both to the register. “Just these two?” asks the volunteer. “Yes,” I say. “Just these two.” I smile so I do not cry. “Thank you again for trying,” I say.

I leave my car in the Project Safe parking lot, and climb down the beanstalk with the hen and the harp in the pocket of my coat. My mother is waiting for me at the bottom. She is no longer feverish and she shows me she can now lift her arm. I would give her the hen and the harp, but when I reach into my pocket I realize both have turned to dust. Now my hands are covered with dust and as the dust falls from my hands it looks like the ellipses to all the stories we thought were over but are still being told. My sons come outside and ask for some dust. I give them each a handful because there is so much dust and they laugh and shout and sprinkle it all over our yard, and their sprinkling looks like ellipses, too. “Did you know?” says Noah, “that without dust there would be no clouds.” “No,” I say, “I didn’t know that.” “It’s true,” says Eli. “There’d be no clouds if we had no dust.” My mother, my sons, and I all look up at the sky. It’s so blue and there are so many clouds. “That one’s shaped like a giant,” says Noah. “And that one, Mama, is shaped like your mouth,” says Eli. And one cloud, the one hardest to see but I promise it’s there, is shaped exactly like what you’d always hoped it to be…

Read earlier installments of Happily here.

Sabrina Orah Mark is the author of the poetry collections The Babies and Tsim Tsum. Wild Milk, her first book of fiction, is recently out from Dorothy, a publishing project. She lives, writes, and teaches in Athens, Georgia.

March 3, 2021

A Message from the Board of Directors

The Paris Review, a literary quarterly based in New York, announced that its editor, Emily Nemens, has resigned to pursue work on her second novel.

In her statement, published today on The Paris Review’s website, Nemens said, “The Paris Review’s mission has always been a dual one: to provide a platform for great literature, and to inspire readers with ambitious new writing. I’m proud that we’ve been able to accomplish both during my time at the Review, and I would like to thank the writers, readers, and colleagues on staff and the board who have collaborated with me toward these objectives.”

The Paris Review, founded in 1953, features original fiction and nonfiction, art, and in-depth interviews with notable writers about their creative processes. Under Nemens’s leadership, the quarterly won awards and attained a record number of subscribers. The Review also has an active digital presence with a large following, and has recently produced two seasons of podcasts featuring readings, interviews, and archival material.

At the time of Nemens’s departure, issue no. 236 has just appeared, and Nemens’s editorial work on the Summer 2021 issue, no. 237, has been completed. The Paris Review is undertaking an active search for her successor. “While we will miss Emily,” said co-presidents Matt Holt and Akash Shah, “we have a wonderful staff, and the magazine has never been in better shape financially. We are all very excited about the next chapter.”

“We are grateful for Emily Nemens’s editorial stewardship of The Paris Review during the past three years,” said publisher Mona Simpson. “In particular, we thank Emily for her leadership guiding the staff through the anxieties and sorrows of the pandemic. We are excited for her new work and wish her every happiness.”

Letter from the Editor

Read a message from the board of directors.

The Paris Review’s mission has always been a dual one: to provide a platform for great literature, and to inspire readers with ambitious new writing. I’m proud that we’ve been able to accomplish both during my time at the Review, and I would like to thank the writers, readers, and colleagues on staff and the board who have collaborated with me toward these objectives. The project of the Review is an ongoing one—seven decades strong—but over the past three years, I’m particularly proud of a few accomplishments: I’m thrilled to see the quarterly at record high circulation, and that the work we publish in its pages has been recognized by peers, including the 2020 American Society of Magazine Editors’ Award for Fiction and the 2021 volume of Best American Poetry, which will include five poems from TPR. Collaborating on the poetry program with Vijay Seshadri was a joy, and I’m eager for readers to explore Poets at Work, an anthology that Vijay edited, when it arrives next month. I’m glad that we are able to support writers early in their careers—few things please me more than an emerging writer landing a book deal off of the strength of their Paris Review story—and concurrently give space to voices I have admired for decades. The Writers at Work interview series is a national treasure, and shepherding conversations with writers like Suzan-Lori Parks, Nathaniel Mackey, and George Saunders into print was a singular privilege.

More readers are finding us online—on the Daily, via newsletters, and on social media—than ever before, with thanks to our great digital team. We made a second season of the podcast and already have some aces in the hole for season three. And while we hosted some good parties and programs in the Before Times, even more readers found us through recent virtual events. Some accomplishments behind the scenes: We began an institutional giving program, with a mind toward building a broader network of philanthropic and government support. We opened digital submissions and began a virtual reader program, offering mentorship and professional development to a nationwide group of volunteer readers. And I’m glad that we were able to create a safe, stable, and creative workplace for TPR’s staff through an unprecedented global crisis. I hope the magazine continues to thrive, through the stressful conditions of the ongoing pandemic and into brighter days ahead.

In his “Letter to an Editor,” in the Review’s first issue, William Styron considers the writer’s duty: “He must go on writing, reflecting disorder, defeat, despair, should that be all he sees at the moment, but ever searching for the elusive love, joy, and hope—qualities which, as in the act of life itself, are best when they have to be struggled for.” The quest Styron describes is not just for expatriate writers of the Silent Generation—it’s an editor’s job, too. From our offices in Chelsea, and, since last March, from an apartment in the East Village, I have sought love, joy, and hope to share on these pages. Yesterday we welcomed the Spring issue, no. 236, into the world, and now, with my work on the Summer issue complete, I am leaving The Paris Review to write my next book. Hopefully, eventually, I’ll edit again—connecting writers to readers is among the world’s best professions. Through it all I will keep seeking out those elusive qualities and sharing them as best I can.

—Emily Nemens

March 2, 2021

Redux: This Cannot Be the Worst of My Days

Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

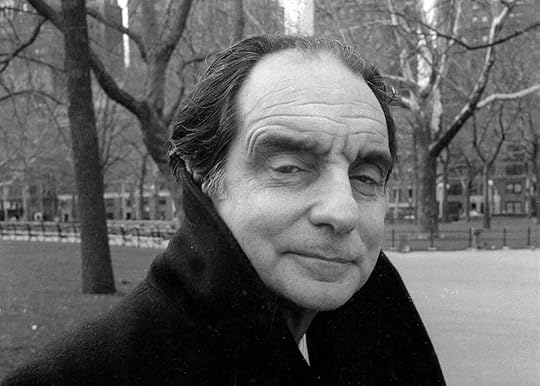

Italo Calvino.

Spring may be around the corner, but this week, we’re taking one last look at winter. Read on for Italo Calvino’s Art of Fiction interview, Deborah Love’s story “One Winter,” and Rohan Chhetri’s poem “New Delhi in Winter.”

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, and poems, why not subscribe to The Paris Review? You’ll also get four new issues of the quarterly delivered straight to your door.

Italo Calvino, The Art of Fiction No. 130

Issue no. 124 (Fall 1992)

By then I had reached a level of obsession with structure such that I almost became crazy about it. It can be said about If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler that it could not have existed without a very precise, very articulated structure. I believe I have succeeded in this, which gives me a great satisfaction. Of course, all this kind of effort should not concern the reader at all. The important thing is to enjoy reading my book, independently of the work I have put into it.

Hermann Dischler, Abendliche Winterlandschaft mit Tannen, 1907, oil on canvas, 7 x 10 3/4″. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

One Winter

By Deborah Love

Issue no. 50 (Fall 1970)

This morning the snow is falling again. It has already filled in the ruts in the drive. The snow makes me happy. Under it tired landscapes concede, errors disappear, and sin is borne under, the whiteness an absolute of infinite possible beginnings.

The baby is still asleep and I wander about the house looking out of the windows. From the kitchen I can see the fields, which go on and on like a vast white sea glazed by sunlight. A pattern of weather has set in. The morning clears and we can watch the spot of sun breaking the gray surround. By early afternoon it closes in again and the gray becomes dotted with white as the snow begins to fail. When the snow is falling the temperature rises as high as 20° but by late afternoon the sky clears and it drops again to zero.

In these warm interludes I take the baby out. She walks over the crust while I break through and flounder in the drifts. It frightens me to imagine I will not be able to climb out of my own footshafts. There I will thrash and make deeper and deeper the cave I am creating, while the baby crawls away to freeze and die.

Carl Skånberg, Vinterlandskap i skymning, 1880, oil on canvas, 26 3/4 x 49 1/8″. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

New Delhi in Winter

By Rohan Chhetri

Issue no. 234 (Fall 2020)

Those mornings in the last days of December,

as the smog deepened over the mausoleum

& the ghost of the emperor’s first wife

lingered about the four gardens, weeping

over her dead child

until a solitary jogger tore the curtain of fog

with a flashlight, making her flee

through a chink in the heavy lid of the small red tomb,

I rose at dawn, washed my face with water

cold as needles & went to work, stomach taut

as deerskin stretched over the seat of a chair.

On the terrace garden above my office,

I drank coffee & smoked a long cigarette

as something unnameable loosened its grip on my neck.

I remember thinking then, This cannot be

the worst of my days, but mostly I remember

myself in some variation of afraid.

Why, I can’t tell …

And to read more from the Paris Review archives, make sure to subscribe! In addition to four print issues per year, you’ll also receive complete digital access to our sixty-eight years’ worth of archives.

Showing Mess: An Interview with Courtney Zoffness

Like so many books, for so long now, I read Courtney Zoffness’s Spilt Milk while mostly isolated with my family. I’ve spent much of this year thinking about what books are worth, why any of us keep bothering. I felt disconnected from fiction that seemed too invested in its own intelligence to engage with characters’ flaws or vulnerabilities. In this time, Spilt Milk enacted a particular sort of magic on me. It’s nonfiction, memoir, a series of essays, unabashedly interested in the quotidian. As a mother, Zoffness worries that her child worries too much, just as she used to and still worries. In another essay, Zoffness, as a freshly minted M.F.A. student, finds herself doing research for the memoir of a Syrian Jew because she needs a paycheck, and so begins tracking the persecution and forced departure of ten thousand Jews from Aleppo. Yet another essay centers on raising her young white son in brownstone Brooklyn, a son who is obsessed with visiting the police precinct close to their home, and the arrival of 2020’s Black Lives Matter protests.

What Spilt Milk helped me to remember was how intimate books can feel, at a time when intimacy feels so hard to come by; a single consciousness unfurling through all the spaces that lack easy resolution, willing to lay itself bare. It’s a strange time for all of us, trapped as we are in our own ways, so relentlessly isolated and afraid. Books are not a cure, and yet books like Spilt Milk remind me that there is a way to feel closer to other people, to feel intimate with them, to see all the ways the individual is so often the surest path to understanding the universal.

INTERVIEWER

One of the things that I sometimes find challenging, or just less true-feeling, about nonfiction is its desire to land somewhere specific. I think so much of life is messier, more about questions than answers, than this idea suggests. You do a gorgeous job of giving us the satisfaction of an essay that feels whole and nourishing while allowing for ambivalence and uncertainty to still feel alive at the end. I wonder if you could talk about how you think of endings? How do you know your pieces are finished and how do you think about the sense of understanding you want your reader to leave with?

ZOFFNESS

Endings are so deceptive. That final period gives the illusion of resolution or conclusion when my thoughts and feelings on nearly every subject and experience in Spilt Milk remain unresolved. I think that one of the aims of an essay is to ask questions, not necessarily answer them, and I try to embed this spirit of inquiry in each piece, to be transparent about my own internal conflicts or uncertainty along the way—whether over parental choices or astrology or my feelings about other people. I want to show messiness. This approach hopefully trains readers not to expect a resolution, but it can also make it harder for me to discern the right endnote. Several of these endings gelled through trial and error.

INTERVIEWER

“I want to show messiness” is a thing that I would say about my own writing as well, a thing I think lots of writers would say, and yet so much of writing is about precision and control. You dip in and out of scenes so quickly and seamlessly. How do you navigate the relationship between the mess you wish to portray and the precision with which you convey it?

ZOFFNESS

I think a carefully composed container can make the mess easier to hold—for the writer, as well as the reader. Sometimes pointed questions can help me chart a course, like trail markers. Other times, questions will emerge from the material. In “Boy in Blue,” for example, about my young, white son’s cop obsession, I write about simultaneously honoring his love of dramatic play while wrestling with his preferences. Readers hear both my attempts to educate him and the limits of his comprehension. A question grew out of these scenes that I hadn’t been able to articulate before I began: How vast is the harm society will do to my sons, and the harm they will inevitably do in return, while their mother waits for them to grow up?

INTERVIEWER

Oof. Yeah.

A common thread through many of these essays is ritual and religion, but then the rituals are often absent of their intended weight. You are Jewish and in the book you grapple with your Judaism, but do not have a relationship with a specific god. How do you think of ritual both as a subject and as a practice?

ZOFFNESS

I think ritual can be beautiful and important. I also don’t think the same ritual necessarily means the same thing to each practitioner—or even the same thing to a single practitioner each time. I believe the meaningfulness of any act depends on the human performing it. I may feel nourished singing certain songs on a particular holiday but the nourishment doesn’t come from feeling close to a god, as it may for others. It comes from an awareness that so many people are doing this same thing at the same time—and have for centuries. It comes from hearing the voices of my younger selves singing this song on holidays past, and the sound of my sons’ voices blending with mine in the present.

INTERVIEWER

I wonder about the particular ritual that writing demands and also the faith inherent in making things. How do you relate these in your work? What sort of faith can be felt outside the spiritual?

ZOFFNESS

This question reminds me of a conversation I have with a doctor in Spilt Milk who notes that a patient’s belief in treatment is part of what makes it effective. She says, “Every time you take a pill, it’s an act of faith. You’re accepting the possibility that you can feel better.” I want to say the same holds true for the literary arts, even if I don’t consciously conceive of it this way when I work. Every time we write a new sentence, we’re accepting the possibility that we can write better. Artistic progress depends on practice, and also a subterranean faith in the process—and ourselves.

INTERVIEWER

Yes! I so agree with this, and using the word practice feels useful as a way of thinking about all of one’s work as a progression. I wonder about the specificity of your practice. Do you write everyday? Do you have any physical or thought rituals around how you work?

ZOFFNESS

I’ve attempted to adhere to a writing schedule, but ultimately I think I’m more of a binge writer. When a literary idea sinks in its teeth, I will work on it fanatically, mull over it constantly, take notes on any paper scrap in my vicinity. I am similarly obsessive about sentence-level shining in the final stages. Then there will be a fallow period where I’ll twiddle on a few different things but prioritize other parts of my life. Maybe the lulls between the sprees are restorative?

INTERVIEWER

Yes. I wonder if this is particular to parenting in some ways. I often describe this to people as dam building, followed by a breaking, but it also has to do with knowing that I can’t actually sustain the level of obsessiveness that I perform.

ZOFFNESS

It’s possibly connected to parenting and I find consolation in this explanation. If I’m really honest with myself though, I’ve always had a hard time regimenting the practice for a sustained period of time. I admire the hell out of other writers who stick to a schedule. Did you have different writing habits before kids?

INTERVIEWER

My practices have stayed similar but the intensity has shifted. I used to get up “early” but that was 6 A.M. and now it’s 4:30 A.M. As a writer who writes about motherhood, how does your role as mother inform your work? How do you navigate writing about your kids?

ZOFFNESS

Curiously, I’ve been writing about motherhood since before I became a mother, though primarily in fiction. One of my first published short stories when I was a young graduate student was about an older woman pregnant with twins. I remember asking a friend who had kids to vet my descriptions for accuracy. That said, becoming a mother transformed my work, not only because it curtailed the time I had to write, but because I started seeing everything through a maternal lens. Everyone was somebody’s child. My kids are really young in this book, mostly under five, so I felt okay including their likenesses on the page. They’re a little older now. If I want to write about them, I ask their permission.

INTERVIEWER

Yeah. My kids are not yet old enough to read my books, but even their ability to sneak a peak over my shoulder now has been a reminder of how their relationship to my work can and will shift. Connected to this is how our various beliefs, and maybe sometimes pathologies, are passed down. There’s the sort of flip, common talk about children being similar to their parents, but for a certain type of person, the idea of our children having to deal with some of the same internal battles that we dealt with can be terrifying. What were the problems and questions you sought to explore in that first essay, “The Only Thing We Have to Fear,” and what, if anything, felt clearer to you after the writing?

ZOFFNESS

The opening essay morphed and evolved over many years. Earlier drafts were really research heavy. I went down a rabbit hole of scientific studies on the parent-child transfer and was studiously deciphering medical jargon. At one point my therapist told me she thought chasing answers to this heredity question was a symptom of my anxiety, which I found hilarious and perfect and probably true. “This Essay is a Symptom of My Anxiety” was a provisional title. I suppose what became clear as I watched my children grow and reworked this essay is the formula-less-ness of parenthood. Even if I found a study or statistic that “proved” some kind of inheritance, would it have mattered? What would it ultimately change? What light could it shed on my distinctive family, or our unique dynamics?

INTERVIEWER

I wonder about the power of language to make us feel in control of an experience that is itself defined by our lack of power. Do you find deploying language around these moments of powerlessness difficult? Energizing? How has writing about parenthood shifted your relationship to the powerlessness inherent in loving another human being this way?

ZOFFNESS

In the same way endings can falsely signal resolution, I think language can falsely suggest control. There’s a difference between describing or dramatizing parental concerns and navigating them with your children. Describing these moments may help me make connections within my own life, and to the world at large, but I don’t think they make me a more effective mom.

INTERVIEWER

Ha. Yes. Speaking of all the roles we fail at as women, in your book there is also a sense of powerlessness around gender more broadly. After a student makes sexual advances at you in front of the class in “Hot for Teacher,” you write, “He’d still felt the need to exert sexual power over me. I was still a woman.” That we can see and name our powerlessness as women often does us very little good. And yet, we both write books. Is there power in naming these dynamics, in grappling with ideas that feel immutable, but still laying them bare?

ZOFFNESS

I think animating these moments of powerlessness sheds light on what contemporary womanhood can feel like, which is worthwhile for all kinds of readers. It can generate awareness and empathy. One aim of that essay was to show the continuity of this experience over time—an aggressive nine-year-old male classmate, a high school jock who cornered me in the dark, the sexually predacious OB-GYN who assaulted dozens of patients. I am a mother of sons. I think a lot about the messaging they receive about boyhood and manhood—and, perhaps more importantly, girlhood and womanhood. When does the indoctrination begin? How can I run interference?

INTERVIEWER

Your essay “It May All End in Aleppo” engages with so many different spaces in which we have so little power—the particular and unrelenting tragedy of Syria, the attacks on and exodus of Jews from Aleppo starting in 1947, this repeated idea about our “struggle to distinguish between what’s real and what’s imagined.” Does the writing in these spaces have a different weight or texture?

ZOFFNESS

It does seem like there are concentric circles of powerlessness and the further out we go, the more abstract they become. I find it easier to write about moments of personal vulnerability because I can translate their weight and texture. I can’t rely on firsthand observations to describe sectarian violence in Syria, a country I’ve never visited, even if, as that essay makes clear, I ghostwrote the memoir of a Syrian Jewish refugee. Powerlessness is a big part of Sol’s history—all the ways in which Aleppine Jews were persecuted after the formation of Israel. They couldn’t own property and had to abide by curfews and were arbitrarily arrested and assaulted. I was moved to learn that a Muslim neighbor saved Sol’s family’s lives when an anti-Semitic mob came calling. Then, in a gutting twist—one that speaks again to powerlessness—Sol voted for Trump in 2016. He didn’t object to Trump’s executive order banning foreign nationals from Muslim countries. Here I had done all this work to get close to his experiences only to have him declare, We all have bigotry inside us. You do, too. It was brutal.

INTERVIEWER

I think there is a sort of strange pressure on writers to talk about “right now,” as if it were possible to make sense of the hot white fact of this moment. Where are you in relation to that impulse as you sit alone in your apartment with your family in the twelfth month of quarantine in 2021? What feels solid about right now? What’s making you feel less afraid?

ZOFFNESS

Having a less sadistic president in office feels pretty solid, as do the vaccines going into more and more arms every day. All of this suggests less death and less suffering. America is just as racist and the planet is still intensely endangered, but there’s room for optimism, too. I’m encouraged by the youth vote surge in 2020. The next generation is showing a commitment to activism and justice of all kinds. Maybe what I’m saying after all this talk about motherhood is, I am less afraid because of the children.

Lynn Steger Strong is the author, most recently, of the novel Want.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers