The Paris Review's Blog, page 126

February 2, 2021

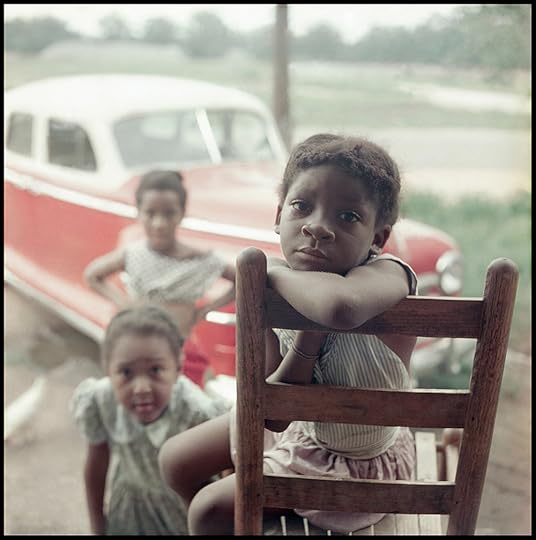

Gordon Parks’s America

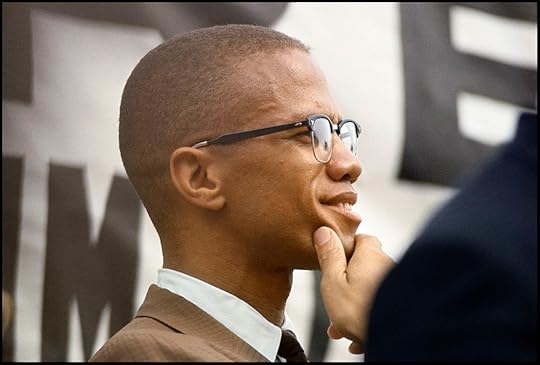

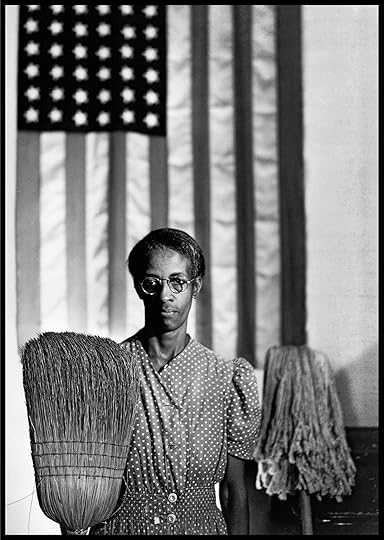

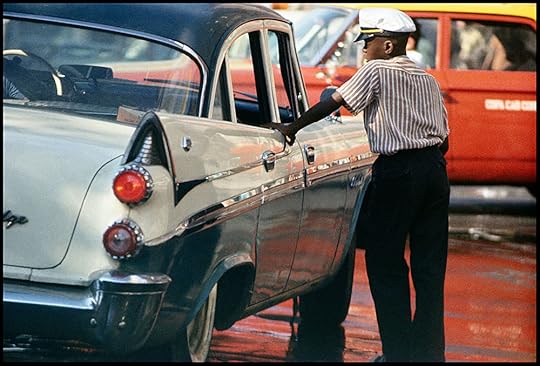

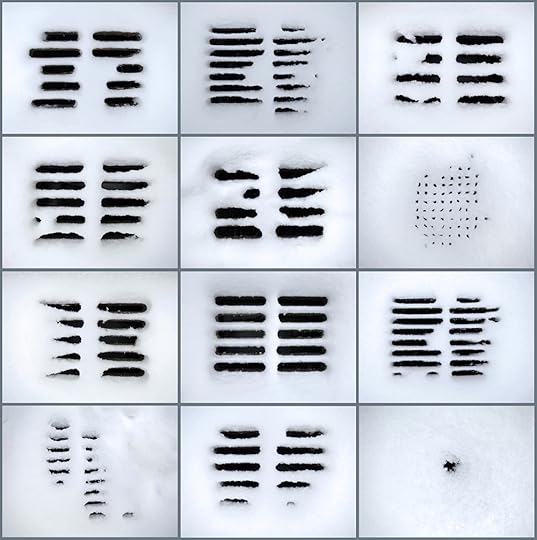

Kansas, Alabama, Illinois, New York—wherever Gordon Parks (1912–2006) traveled, he captured with striking composition the lives of Black Americans in the twentieth century. From his first portraits for the Farm Security Administration in the early forties to his essential documentation of the civil rights movement for Life magazine, he produced an astonishing range of work. In his photographs we see protests and inequality and pain but also love, joy, boredom, traffic in Harlem, skinny-dips at the watering hole, idle days passed on porches, summer afternoons spent baking in the Southern sun. With “Half and the Whole,” on view through February 20, Jack Shainman Gallery presents a trove of Parks’s photographs, many of which have rarely been exhibited. A selection of images from the show appears below.

Gordon Parks, Untitled, Shady Grove, Alabama, 1956, archival pigment print, 34 x 34″ (print). Edition L5 of 7, with 2APs Inventory. Copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation. Courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Gordon Parks, Untitled, Chicago, Illinois, 1957, archival pigment print, 30 x 40″ (print). Edition 1 of 7, with 2APs Inventory. Copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation. Courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

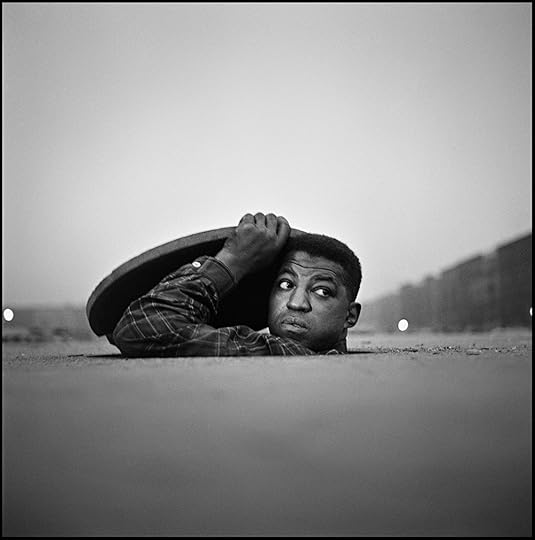

Gordon Parks, The Invisible Man, Harlem, New York, 1952, gelatin silver print, 42 x 42″. Edition 2 of 7, with 2 APs. Copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation. Courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

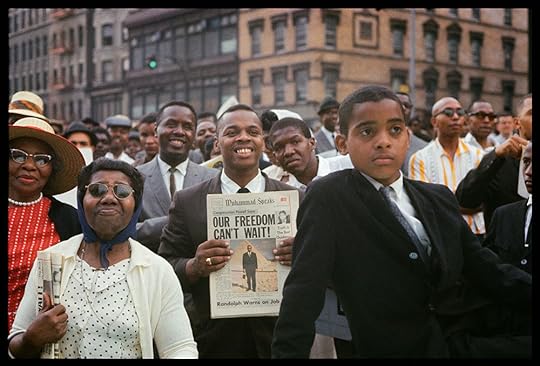

Gordon Parks, Untitled, Harlem, New York, 1963, archival pigment print, 30 x 40″ (print). Edition 6 of 7. Copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation. Courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

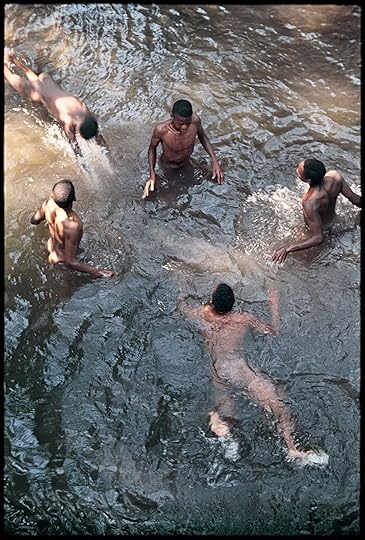

Gordon Parks, Watering Hole, Fort Scott, Kansas, 1963, archival pigment print, 24 x 20″ (print). Edition 1 of 7, with 2 APs. Copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation. Courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

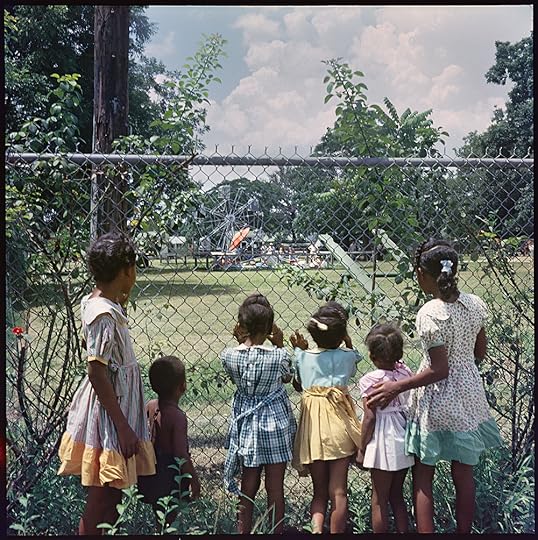

Gordon Parks, Outside Looking In, Mobile, Alabama, 1956, archival pigment print, 46 1/8 x 46 1/4″ (framed). Edition L1 of 7, with 2 APs. Copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation. Courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Gordon Parks, Untitled, Harlem, New York, 1963, archival pigment print, 30 x 40″, Edition 1 of 7, with 2 APs. Copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation. Courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Gordon Parks, American Gothic, Washington, D.C., 1942, gelatin silver print, 14 x 11″ (print). GPF authentication stamped. Copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation. Courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Gordon Parks, Untitled, Harlem, New York, 1963, archival pigment print, 30 x 40″ (print). Edition L1 of 7, with 2 APs. Copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation. Courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Gordon Parks, Department Store, Mobile, Alabama, 1956, archival pigment print, 50 x 50″ (print). Edition 4 of 7, with 2APs. Copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation. Courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

“Half and the Whole” will be on view at both Jack Shainman Gallery locations through February 20.

Redux: A Window like a Well

Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

John Hall Wheelock. Photo: Rowland Scherman.

This week at The Paris Review, we’re peering through windows. Read on for John Hall Wheelock’s Art of Poetry interview, an excerpt from Gerald Murnane’s Border Districts, and Forough Farrokhzad’s poem “Window.”

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, and poems, why not subscribe to The Paris Review? Or take advantage of our new subscription bundle, bringing you four issues of the print magazine, access to our full sixty-seven-year digital archive, and our new monogrammed notebook for only $69 (plus free shipping!).

John Hall Wheelock, The Art of Poetry No. 21

Issue no. 67 (Fall 1976)

One reason I know it was not my line is I consulted a dictionary to find out that an oriel was a window in a balcony that you could look down from. I had sensed that it was some kind of window, but I didn’t know. I looked it up, afraid that it might be the wrong kind of window and wouldn’t fit into the poem. Now I have taken that line on as my own, yet no one can convince me that I didn’t hear it.

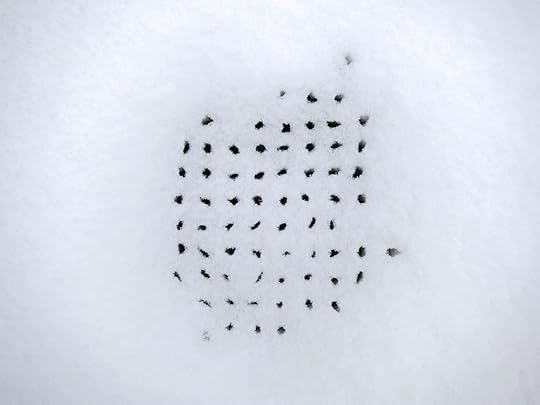

Photo: Klapi. CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...), via Wikimedia Commons.

from Border Districts

By Gerald Murnane

Issue no. 217 (Summer 2016)

I have always believed myself to be indifferent to architecture. I hardly know what a gable is or a nave or a vault or a vestry. I would describe my neighborhood church as a symmetrical building comprising three parts: a porch, a main part, and, at the furthest end from the street, a third part surely reserved for the minister before and after services. The walls are of stone painted—or is the correct term rendered?—a uniform creamy white. I am so unobservant of such details that I cannot recall, here at my desk, whether the pitched roofs of the porch and the main part are of slate or of steel. The rear part has an almost flat steel roof. The windows aren’t of much interest to me, except for the two rectangular windows of clear glass, each with a drawn blind behind it, in the rear wall of the minister’s room. The main part of the church has six small windows, three on each side. The glass in each of these windows is translucent. If I could inspect it from close at hand, the glass might well seem no different from the sort that I learned to call as a child frosted and saw often in bathroom windows.

Photo: Gryffindor, CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/b...), via Wikimedia Commons.

Window

By Forough Farrokhzad, translated by Elizabeth T. Gray Jr.

Issue no. 233 (Summer 2020)

A window for seeing

A window for hearing

A window like a well

that ends deep in the heart of the earth

and opens out into this expanse of recurring blue kindness

A window that overfills the tiny hands of loneliness

with its nightly gift: the perfume of generous stars

And from there one could invite the sun

to the geraniums in exile

One window is enough for me …

And to read more from the Paris Review archives, make sure to subscribe! In addition to four print issues per year, you’ll also receive complete digital access to our sixty-seven years’ worth of archives. Or take advantage of our new subscription bundle, bringing you four issues of the print magazine, access to our full archive, and our new monogrammed notebook for only $69 (plus free shipping!).

February 1, 2021

Cavafy’s Bed

Aerial view of Alexandria, ca. 1929. Photo: Walter Mittelholzer. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

It’s my first Palm Sunday in Rome. The year is 1966. I am fifteen, and my parents, my brother and I, and my aunt have decided to visit the Spanish Steps. On that day the Steps are filled with people but also with so many flowerpots that one has to squeeze through the crowd of tourists and of Romans carrying palm fronds. I have pictures of that day. I know I am happy, partly because my father is staying with us on a short visit from Paris and we seem to be a family again, and partly because the weather is absolutely stunning. I am wearing a blue wool blazer, a leather tie, a long-sleeved white polo shirt, and gray flannel trousers. I am boiling on this first day of spring and dying to take off my clothes and jump into the Roman fountain—the Barcaccia—at the bottom of the Steps. This should have been a beach day, and perhaps this is why the day resonates with me so much.

Two years before, in 1964, we were probably celebrating Sham el Nessim, the Alexandrian spring holiday, which for many of us usually marked the first giddy swim of the year.

But in Rome at the time I am not thinking of Alexandria at all. I’m not even aware that there might be a connection between Rome, this eruption of beach fever, and Alexandria. The yearning to jump into a body of water and drink it whole, and always that search for shaded areas, away from the blazing sun—these are what my body wants, now that the wool I’m wearing is unbearable.

After our long walk on the Pincio, we come back down the Steps and stop to buy a juice and a sandwich each in a small corner bar on Via della Vite. The bar has turned off its lights to keep the premises cool. It feels good inside. I like my sandwich simple, containing only coleslaw.

A used bookstore right next to the Keats-Shelley House by the Spanish Steps happens to be open that day. My father and I do what we always do when we’re together: we look for books I should read. He points out a used copy of Chekhov’s short stories, but I want to read Olivia. So we buy Olivia. He read it in French, he says, and promises it will certainly offset the Dostoyevsky I’ve been devouring that entire year. My father has definite opinions about books. He dislikes current writers, dislikes the bare rag-and-bone shop of the heart; anything that smacks of the immediate world around us turns him off. Instead, he likes his literature a touch dated—say, by thirty to forty years. I understand this. Everyone in the family feels a bit dated and out of sync with the rest of the real, here-and-now world. We like the past, we like the classics, we don’t belong to the present.

A week later, my father is already back in Paris. It’s Saturday, and I am back on Piazza di Spagna, this time alone. Many of the flowerpots have already been removed, though there are a great many still. I don’t want to go home, so I hang around the Spanish Steps. At around twelve or so, I stop at the same bar and buy a coleslaw sandwich, as I’d done the week before. I also buy a book that I know my father would approve of: the short stories of Chekhov. Past one o’clock, the area begins to empty, and all the stores are closed. I am sitting on the warm Spanish Steps and am peacefully reading. I am, of course, not really focusing on the story; what I am longing for is a whiff of a marine breeze; I want to be transported back to last week and to that feeling of well-being and plenitude that had suddenly erupted in our lives without warning or explanation on Palm Sunday.

For a month or so after that day, every Saturday I would buy a book and a coleslaw sandwich and begin reading on the Spanish Steps. I still do not make the connection with Alexandria during that period. I don’t even make it when, exactly a year later, around Palm Sunday once again, I finally decide to buy the first volume of Lawrence Durrell’s Alexandria Quartet. I am alone that day, and the memory of the previous year’s Palm Sunday hovers over the day like an illusion of a day spent not on these Spanish Steps but at the beach in Alexandria. I like this shadow memory.

Half a century later the meaning of these ritual weekly errands to the Spanish Steps is somewhat clearer: part longing for a larger, happier, secure household, and part yearning for an Alexandrian world that was entirely lost. What I wanted by myself in 1967 was the family outing in 1966, though the 1966 outing mattered because it held wisps of Alexandria in 1964.

Alexandria eventually came to me one afternoon as I lay in bed reading Justine. I liked to read in the afternoon and welcomed those precious minutes when a band of sunlight, reflected from a window across the courtyard, would settle on my bed. It was then that I fell upon a list of familiar names of Alexandria’s tramway stations: “Chatby, Camp de César, Laurens, Mazarita, Glymenopoulos, Sidi Bishr,” and, a few pages later, “Saba Pasha, Mazloum, Zizinia, Bacos, Schutz, Gianaclis.” And then I just knew. I had not invented Alexandria. And just because I was never going to see it again didn’t mean that it was dead and expunged from our planet. It was still there, and people still lived in it, and, contrary to what I’d led myself to think, I didn’t hate it, it was not ugly, there were people and things I still loved there, places I still longed for, foods I would give anything to savor one morsel of, and the sea, always the sea. Alexandria was there still. I just wasn’t.

But I already knew it wasn’t the same Alexandria; my Alexandria no longer exists. Nor does the Alexandria that E. M. Forster knew during World War I, nor the Alexandria that Lawrence Durrell made famous after World War II. Their Alexandrias are all gone. And as for the city I grew up in in the fifties and early sixties, it, too, no longer exists. Something else lies on Egypt’s Mediterranean coastline today, but it’s not Alexandria. E. M. Forster, the author of the classic guidebook to Alexandria, lost his way in the streets of the city when he returned before writing the third preface to his Alexandria: A History and a Guide. Durrell might never have gotten lost down some of its sinister lanes, but he certainly wouldn’t recognize the Alexandria of the Quartet one bit—and for good reason: that Alexandria never really existed in the first place. But then, Alexandria was always the child of fancy. Durrell, like C. P. Cavafy, saw another Alexandria, his Alexandria. Many artists have re-created their city and made it theirs forever: Matisse’s Nice, Hopper’s New York, Fellini’s Rome, Joyce’s Dublin, Svevo’s Trieste, Malaparte’s Naples. As for me, I could still take a walk in Alexandria today and never get lost; however, the character of Alexandria has so thoroughly changed in the five decades I’d been away that what I found there, when I finally did go back thirty years after leaving, unhinged me completely. This was not the place I had come looking for. Whatever this was, it was not Alexandria. Where today’s Alexandria is headed is anyone’s guess, though I shudder to speculate.

Cavafy, the ultimate Alexandrian, gave us an Alexandria that was already not quite there in his own lifetime. It kept threatening to disappear before his eyes. The apartment where he had made love as a young man had become a business office when he went to revisit it years later; and the days of 1896, of 1901, 1903, 1908, 1909, once filled with so much eros and forbidden love, were already gone and had become distant, elegiac moments that he remembered in poetry alone. The barbarians, like time itself, were at the gates, and everything would be swept in their wake. The barbarians always win, and time is hardly less ruthless. The barbarians may come now or in a century or two, or in a thousand years, as indeed they had come more than once centuries earlier, but come they will, and many more times after that as well, while here was Cavafy, landlocked in this city that is both the transitional home he wishes to flee and the permanent demon that can’t be driven out. He and the city are one and the same, and soon neither will exist. Cavafy’s Alexandria appears in antiquity, in late antiquity, and in modern times. Then it disappears. Cavafy’s city is permanently locked away in a past that refuses to go away.

As for the old Alexandria of Alexander the Great, of the Ptolemies, of Caesar and Cleopatra, of Callimachus, Apollonius, of Philo and of Plotinus, and, let’s not forget, the Alexandria of the great library, well, it perished many times over and, from the evidence available today, might as well never even have existed. Stones and shards, scraps and fragments, layers and tiers. The Alexandria of these ancients, like Cavafy’s Alexandria or like mine, just happens to have been in Alexandria and, strange to say, happens to be called Alexandria, too, and, coincidentally enough, some of its streets still run along the same lines that the founders of the city laid down more than two thousand years ago. But it’s not Alexandria.

There have been many Alexandrias. Egyptian, Hellenistic, Roman, Byzantine, Ottoman, colonial—each pluralistic: multiethnic, multinational, multireligious, multilingual, multieverything, or, in the unforgettable words of Lawrence Durrell in one of his more whimsical moments, a city of “five races, five fleets and more than five sexes.” But he also branded it a “moribund and spiritless backwater … a shabby little seaport built upon a sand reef.”

Yet Alexandria is more than a place, more than an imbrication of layers and tiers, more than an idea, more than a metaphor, even. Or maybe it’s just that: a self-perpetuating, self-consuming, self-regenerating idea that won’t go away, because it’s already gone away, because it never really existed in the first place, because it’s still struggling to come into being, and we’re too blind to see this.

Alexandria is an invention. It is totally man-made, artificial, the way Saint Petersburg is entirely man-made and, therefore, unnatural. A man-made city does not sprout; it is pulled out of sludge and then shaken into existence. Because it is a graft, it never feels secure in its place, never belongs. It is on borrowed time, and the ground on which it’s built comes from scrounged landfills and stolen earth. Which is why, perhaps, like all newly wealthy cities, Alexandria was always splendiferous and extravagant—to forget it stood on shaky ground, for nothing bound it to earth. You could not swear on the ground you stood on, because the ground you stood on was never really firmly there, nor was it ever divinely yours to be sworn on in the first place. A transitional identity cannot even swear on anything, because it is transcendentally divided, homeless, and, hence, transcendentally disloyal. Which is also why no one had convictions in Alexandria, and any oath, like truth, was always a shifty business. Alexandria borrowed belief systems and robbed traditions from its neighbors because it had none of its own to pass on, though it almost always perfected the things it adopted; its great contribution was not always invention, but reinvention. Under the Ptolemies it stole every book it could lay its hands on, the way it appropriated and then promoted the knowledge it found in them. It borrowed nationalities, borrowed workers, borrowed legacies, borrowed languages, borrowed, borrowed, borrowed, but was never one thing in one place, which is why it is the only spot in the history of mankind that not only understands but that feeds on and ultimately prescribes paradox in its charter. It won’t be shocked when church and brothel share the same roof, because it knows that prophet and street hustler, priest and poet, are not just easy bedfellows, they are one and the same person. Wealth, pleasure, intellect, and God—that’s what Alexandria added up to; or, in the words of Auden about Cavafy, “love, art, and politics.” How these three managed to cohabit without tearing one another apart can be explained by one word only: luck. And luck never lasts—like the library, which burned down many times over, like Hypatia, who died of a thousand cuts. It never lasts, because it cannot last. Cavafy, a Greek born in the Ottoman Empire, living in British colonial Egypt, knew all about barbarians at the gate and all about luck running out. The barbarians came to Byzantium bearing a cross once. Two centuries later they came bearing the crescent. Byzantium never stood a chance. Alexandria didn’t either.

Which is why in my time, and slightly before my time, all Alexandrians had permanent homes elsewhere, held two nationalities, and boasted at least four mother tongues. Everyone was mixed. This was true in antiquity, and it was true in the last century. Alexandria was provisional in every sense of the word, the way truth is provisional, home is provisional, pleasure and, of course, love are provisional. There is no other way. Those who believed that Alexandria was here to stay were not Alexandrians. They were the barbarians.

Alexandria is unreal. You watch it go away. You know it will. You wait for this. You anticipate the end and already know you’ll remember you anticipated it when that day comes. There is no present tense in Alexandria. Time’s covenants were always broken here. However you look at things, everything always already happened, will happen, might, could, should happen. You never planned for next year; that was being presumptuous. Instead, you planned to remember. You even planned to remember planning to remember.

Caught between remembrance and anticipated memory, the present tense always played an elusive minor part in a deafening symphony of verbal tenses and moods. We lived counterfactual lives in a medley of “timescapes.” Once again, irrealis moods: part conditional, part optative, part subjunctive, part nothing. You fantasized a future without Alexandria before even leaving Alexandria, the way you already knew you’d remember rehearsing a preemptive sense of nostalgia for Alexandria while you were still living there.

When Cavafy steps into the room where he made love in his younger days, he is neither here nor there. He watches the cast of the afternoon sun spread over where he remembers there was once a bed, and he is almost certain that he knew, already back then in his younger days, that he’d think of these dear hours in the afternoon many, many years hence. This is, this was, will always be, the real Alexandria. Cavafy never says this. But I do. Otherwise the poem means nothing to me. Here it is in my free translation:

The Afternoon Sun

This room, how well I’ve known it.

Now it and the one next door are rented out

as business offices. The whole house

is home to brokers, merchants, companies.

This room, how familiar it still is.

Near the door here was the couch,

in front of it, a Turkish carpet,

nearby a shelf that held two yellow vases.

To the right, no, opposite, a closet with a mirror.

In the middle, the table where he wrote;

and the three large wicker chairs.

Next to the window was the bed

where we made love so many times.

This poor furniture is nowhere now.

Next to the window, the bed

which the afternoon sun touched midway.

… At four o’clock one afternoon we parted

for just a week … But alas,

That week lasted forever.

Cavafy would never have walked into the old room and just thought, Here was a bed once, here a chest of drawers, here sunlight across our bed. This is not the complete thought. What he thinks of and is unable to say is: I never thought I’d be back here remembering these afternoons when my body and his lay coiled together in this very spot. But that’s not true. I know I thought this, surely I did, and if I didn’t, then let me imagine that, as we lay on this bed, exhausted from our lovemaking, that I already had a presage I’d come back here decades later looking for this younger self who surely would have earmarked this moment so that I’d recover it as an older man and feel that nothing, nothing is ever lost, and that if I should die, then surely this rendezvous with myself will not have been in vain, for I’ve inscribed my name in the hallways of time as one writes one’s name on a wall that has long since been torn down.

The present hardly exists for Cavafy. It hardly exists, but not because Cavafy was too prescient to the ways of the world not to foresee that he’d remember the past before the future had occurred, or because his writing is punctuated by competing temporal zones, but because the real, inhabited zone of his poetry has literally become the transit between memory and imagination back to imagination and memory. The reflux is where things happen. In Cavafy, intuition is counterintuitive, and impulses are thought-tormented, and the senses are too canny not to know that something like disquiet and loss always await lovemaking. The grasp on things is always, always tentative and counterfactual. Cavafy the lover would not have written this poem as a nostalgist, but as someone who was, as he is in so many of his poems, already awaiting nostalgia and therefore fending it off by rehearsing it all the time.

Being in Alexandria is part imagining being elsewhere and part remembering having imagined this. Alexandria cannot die and doesn’t let go, because it never really is, or if it is, it is never itself long enough. It is the shadow of something that almost was but stopped being yet continues to pulsate and craves existence though its time hasn’t come yet but could just as easily have already come and gone. Alexandria is an irrealis city, always apprehended but never fully discovered, always adumbrated but never really touched, an Alexandria that, like Ithaca or Byzantium, has always been and will always never be quite there.

I was aroused and thrilled while discovering Durrell’s sensuality. Who knew that I’d lived in a city where such things happened, things I dreamed of and thought of all the time but needed to see in print to realize they were not just airy, schoolboy fantasies? They would have been at hand’s reach in Alexandria. All I should have done was ask our driver, who was the most open-minded man I knew in Egypt, to tell me where I could find those pleasures Durrell seemed to know so much about. Some open-minded relatives would have helped me find these pleasures, since they, too, knew all about them. There were stores where I could walk in and, like Cavafy’s narrator, ask about the quality of the cloth and allow my hand to graze the salesclerk’s hand. There were women who stood on the same sidewalk in the evening who I wished would turn their gaze on me, though I was just a young fourteen-year-old then. And there were men, too, who threw the most feral glances at me that both scared and troubled me and that I would be tempted to return, because mine would surely lead to nothing. This was a city I’d just begun to know before leaving, and now that it was too late, I was suddenly discovering it in Rome—Rome, whose Spanish Steps and bookish errands and coleslaw sandwiches on Saturday afternoons were nothing more than poor stand-ins for a city and a way of life forever lost. In my room in Rome, and with Durrell and Cavafy as guides, block by block, tram station after tram station, I began reinventing a city I knew I was already starting to forget and could kick myself for not having studied better to anticipate the day when I’d look back from Italy and remember so little.

André Aciman is the New York Times best-selling author of Call Me by Your Name, Out of Egypt, Eight White Nights, False Papers, Alibis, Harvard Square, Enigma Variations, and Find Me. He’s the editor of The Proust Project and teaches comparative literature at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. He lives with his wife in Manhattan.

Excerpted from Homo Irrealis: Essays , by André Aciman. Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, January 19, 2021. Copyright © 2021 by André Aciman. All rights reserved.

January 29, 2021

Staff Picks: Gardens, Glasgow, and Graves

Still from Kentucky Route Zero.

Kentucky Route Zero is haunted in the same way America is haunted. In this five-act play of a video game, the characters Conway and Shannon and their bizarre companions amble back and forth, around and through the real and unreal roads and rivers of rural Kentucky. Everyone has a goal of some sort—delivering one last antique, finding a new workshop, reaching another gig—but all of it folds into the layers of this dreamscape underworld. Just as so many Latin American writers took inspiration from Faulkner, the Southern Gothic of Kentucky Route Zero takes inspiration right back from the magic realism of García Márquez and the pointed political artistry of Neruda. The hopeful folk songs of miners punctuate Kentucky’s caves and forests as their ghosts come out to perform again, long past their deaths at the hands of corporate greed and negligence. Artists and blue-collar workers alike become trapped by exploitative debts that never stop following them. At the heart of Kentucky Route Zero is the mounting fear that these specters are not from the past or even the present but exist eternally. There never were good old days because America’s been stuck in the same cycle since its inception. Any memory of this land is phantom-ridden and cyclical; as Conway says at one point, “I can’t look at anything without remembering something else, and then that reminds me of something else, and—I’m buried in it.” In another scene, a minor character asks, as they’re digging a grave: “Just what are we burying here, anyway? Is it them, or us? Or some mix of both.” Kentucky Route Zero argues that in a sense, we all haunt America. Our debts, fears, and memories hang over others and this nation as much as they hang over us. No single change will exorcise the land, but perhaps by seeking out little slices of beauty where we can find them—little slices of togetherness—we can learn to live with the ghosts and respect them, for they are no different from us. —Carlos Zayas-Pons

My seven years in South Louisiana gave me an earful of music and a bellyful of food. I miss those parts of Louisiana always, but particularly during carnival season. In prepandemic, post-Louisiana times, I did what I could to get my fix. Two springs ago, my boyfriend’s friend’s friend shipped live crawfish to Brooklyn for a boil. Reader, I was the third attendee to arrive. I’ve sought out—and found—real andouille in Manhattan (served wafer-thin at Birdland) and tasted many New York City beignets—none met the standard set by Baton Rouge’s Coffee Call. But as this strange COVID carnival gets under way (Mardi Gras this year is on February 16), I do what I can to celebrate the season safely. Last week, USPS delivered a box of beads, a purple-and-green feather boa, and a box of king cake mix (baby included) from a friend who knew I’d be missing Louisiana right about now. The Venn diagram of pandemic beans and Monday red beans and rice overlaps nicely. And over the weekend, we put on WBRH, Baton Rouge Magnet High School’s public radio station. Dweeby as it sounds (and there are some adorable high school DJs on air midafternoon), the station’s Saturday music lineup is just what I need. Dancing ’round the sofa isn’t quite following a second line down the street, but it’s cheering all the same. —Emily Nemens

Douglas Stuart. Photo: Martyn Pickersgill.

Sometimes it feels like every new novel these days is interested primarily in the concerns of the upper middle classes, their exploits and their triumphs. Thank God, then, for books like Douglas Stuart’s Shuggie Bain, which transports the reader to eighties Glasgow and follows the difficult childhood of its title character as he grows up gay and working class with an alcoholic parent. Like many alcoholics, Shuggie’s mother, Agnes, is both charismatic and brutal, capable of making her loved ones feel like the most special people in the room while simultaneously forcing them to care for her and witness the slow suicide that is her addiction. Stuart is adept at portraying the power politics of both Glasgow, with its sectarian divides, and the world at large: a scene involving Shuggie’s elder sister’s impending move to apartheid-era South Africa illustrates how easy it can be for the oppressed to become the oppressors. And at the center of it all is Agnes: beautiful, funny, and capable of extraordinary interpersonal violence, doomed to repeat the cycle of her addiction on every page, save for “one good year,” as Shuggie heartbreakingly terms it. By its end, Shuggie Bain is a book about power: who has it, what it takes to get it, and how a lack of it will destroy a person just as much as an excess. —Rhian Sasseen

There are books you breeze through, books you dip into, books you devour, books you handle with care; Anushka Jasraj’s Principles of Prediction, a collection of stories currently available only in India, is the last. This sentence, in “Circus,” forced me to put the book away for an entire evening before I could go back to it: “Language is a rigged carnival game where the hoops are too small to fit around any of the prizes.” There is something eerie and prescient, and deeply discomfiting, about how Jasraj captures distance, disconnection, the breakdown of something so fundamental it is hard to put a word to; characters fail to reach each other or even to really reach themselves and generally seem not entirely certain they actually want to do so—because who knows what they will find there? If story, in general, is an attempt to create meaning and to communicate it—because a story is not a story until it is told—these powerful, precise stories are a look at what happens when you can no longer make that effort. —Hasan Altaf

It seems almost impossible that the opening poem of Khadijah Queen’s Anodyne, titled “In the Event of an Apocalypse, Be Ready to Die,” was written years ago rather than right now, on the occasion of this attenuated world ending, but it was. The book greets us with a prescient warning, readying us for a world “transformed but not really transformed”—but still, “remember galleries, gardens, / herbaria. Repositories of beauty now / ruin.” The whole collection progresses in iterations of this: transformations in which the world, then the body, feel untenable, but small things emerge to feed our hopes nonetheless. “Foolish I know,” Queen declares, “to try so many times / after spectacular failure,” and yet she walks this line of mournfulness and hope so expertly that she invites you to attempt it, too. And I cannot fathom that “The World Tells You Not to Expect the World” was written long before I encountered it, at this exact phase of life in which I need it, though the poem feels almost extemporaneous as it comes up from the page to say: “do it anyway—be made, all / out of love.” Every poem in Anodyne reminds me what a poem can do, what a poem should do, in how it gets to the details of personhood by attending so gorgeously to the details of the world. There are no empty sentiments; every permission to accept tenderness is hard earned. And there is no shying away from harshness when conjuring beauty or cultivating hope. “How we fail is how we continue,” Queen says. And we continue. —Langa Chinyoka

Khadijah Queen. Photo: Michael Teak.

The Conundrum of “Conundrum”

Stephanie Burt on how to remember Jan Morris’s trans memoir Conundrum. Jan Morris died in November of 2020, and you can read a remembrance of her by her colleagues here.

JAN MORRIS

Before the actor Elliot Page and the model Janet Mock and the legislator Danica Roem and the TV star Nicole Maines were born, before Against Me! and Anohni and Cavetown had sung a note, before Jenny Boylan’s She’s Not There and Kate Bornstein’s Gender Outlaw and Eddie Izzard’s Definite Article, twenty years before the first recorded appearance of the word cisgender, and three years after I was born, in 1974, the Anglo-Welsh travel writer and veteran Jan Morris published a short and beautiful book called Conundrum. Morris was already famous as the first journalist up Mount Everest, part of Edmund Hillary’s expedition: she would go on to publish dozens more books and a flurry of essays (some in The Paris Review) before her death in 2020, but Conundrum remains her best known.

Not the first modern trans memoir, but perhaps the first with literary ambitions, Conundrum helped establish one way of thinking about what it means to be trans. It’s an early example of the “wrong body” narrative (the phrase shows up on the first page), the story by which the truly trans person always knew she was a woman (if assigned male at birth) or a man (if assigned female). It’s also the kind of now-obsolescent narrative by which genital surgery, and only genital surgery, confirms trans women as really and only true women: Morris’s longed-for operation, in Morocco, becomes “the climax of my life.” Her preface to the 2001 reissue called the volume “a period piece.” Between the lead-up to surgery, the wrong-body story, and the occasional nostalgia for Empire, Morris’s memoir might now seem so dated as to provide no help for the present—except that it does, and not just for its rich style. Conundrum remains a sympathetic guide, not so much to present-day transgender struggles as to trans joy.

As a child in Somerset and Oxford, Morris knew herself as a “girl in a boy’s body.” She “cherished that knowledge as a secret” through the male sociability of a boarding school, the Army’s postwar Ninth Lancers, the Everest expedition, and the professional life of a midcentury foreign correspondent, rushing from coup to summit to tourist attraction to war zone. “The flexibility and self-amusement I absorbed from the Oxford culture—which is to say, the culture of traditional England” saved her sanity, by her own account, while the situational homosexuality, and the male camaraderie, of her teens and twenties neither scarred nor transformed her. “I was kindly treated in the Army,” she remembered, “and far from making a man of me, it only made me feel more profoundly feminine at heart.”

She was, in a sense, a foreign correspondent already, embedded in “an entirely male adult world.” Morris says that she was “pining for a man’s love,” though not in a directly sexual sense: Morris denied that her feelings were (her word) homosexual. Instead Conundrum insists on a more diffuse sensuality that Morris found in ritzy fast cars, in Venice, in a “caress” from a loved one of any gender, in other “tactile, olfactory, proximate delights,” prose style itself perhaps among them. Morris’s sense of “the British masculine ethos” emphasizes esprit de corps, shared devotion to a shared public goal, like statecraft or mountain climbing. Women, by contrast, keep on “doing real things, like bringing up children, painting pictures, or writing home.”

Her sense of group effort as masculine and individuality as feminine speaks to a social stratum that had Empire while Americans had a frontier. “I was a child of the imperial times,” she admits, decrying “that distasteful ignominy, Suez.” She had already quit as a foreign correspondent, becoming instead a full-time freelance writer, before coming out, but she continued traveling for pleasure and for her many freelance assignments. The Arab world comes off well in her brief accounts: “In the heart of Muslim Cairo, women were more naturally accepted in the office than they would have been at the Guardian,” let alone the Times of London. Mexicans, South Asians, and Fijians are, on the other hand, “guileless peoples.” (She means it as a compliment—they accepted her gender—but it has not aged well.)

The last half of the memoir chronicles Morris’s journey from globe-trotting journalist, to Wales-based (and still traveling) parent and husband, to increasing unhappiness with her body and her movement through the world, until—first with hormones, then with changed social status, then with surgery—she becomes able to live as who she is. Reputable UK doctors, willing to perform Morris’s bottom surgery, insist that she first divorce her wife. Instead she chooses a surgeon in Morocco. Morris’s time in Casablanca “really was like a visit to a wizard,” and it left her “astonishingly happy” —as, to judge from her prose, she remained. Jan and Elizabeth would stay together, one way and another, for seventy years.

There is no one trans story: Morris’s memoir remains one of many. It’s a fine lesson about her life alone, but an iffy guide to trans lives more generally. Many of us don’t need surgery, many of us need it but don’t get it, and many of us do want it very much, but do not regard it as the climax of anything—hormones, social transition, and outward appearance can all be more important. So can meeting other trans folks: only in Casablanca, after “the operation,” did Morris “set eyes for the first time on others like me.”

Around 1991, I read Conundrum for the first time myself. I remember it as validation—a literary author, one who (as we said then) had a sex change, felt as I did. Much later, starting on hormones, I, too, “relished the goodness of the sun in a more directly physical way… Life and the world looked new.” Today it is not hard to meet other trans people online, and even (if you are lucky enough to live in, say, Wellington, New Zealand, or some other place without COVID-19) in person. Back then I could do so only in books. I had met young gay men, and fallen hard for charismatic lesbians, and felt out of place at fabulous parties hosted by splendid drag queens. I had tried and failed to see myself in the confidence of genderfluid rock stars. But I had never encountered anyone who admitted to feeling like me.

Morris could hardly have seen so many of us coming. She believed she was one of “at least 600 people … in the United States,” “perhaps another 150 … in Britain,” to have had gender-affirming surgery (she said nothing about how many people might want it). She predated by decades today’s galaxy of trans books for trans readers (some from queer or trans publishing houses), books like Imogen Binnie’s Nevada or Rachel Gold’s Being Emily or Roz Kaveney’s Tiny Pieces of Skull or the anthology We Want It All. Nobody knows how many trans people there are—it depends how you count us—but a UCLA law school study from 2016 guessed over a million in the United States alone.

More troublingly, the Morris of 1974 sites herself among “true transsexuals,” and as against “the poor castaways of intersex, the misguided homosexuals, the transvestites, the psychotic exhibitionists.” Insisting that she’s one of the real, deserving few, and not of the mentally ill, unreliable many, Morris replicates the medical model propounded in the sixties and seventies by doctors such as Harry Benjamin and Robert Stoller. (Benjamin himself prescribed her hormones.) Today we call this sort of distinction between deserving and undeserving trans people (practiced largely by cis doctors) gatekeeping, and many of us want to end it. (It’s a particular problem, both for teens and for adults, in Britain.) Still other passages could have been written today: wondering whether and how to come out with young children in the house, she registers “the fear that I might in some way harm them by revealing the truth too soon. Besides they had a marvelous mother already.”

The modern movement for trans acceptance owes far more to trans people from other backgrounds and with other ambitions, to Marsha P. Johnson or to Sandy Stone, than it ever could to Jan Morris. But that is not Morris’s fault. Conundrum belongs near the headwaters of a great and nourishing river of Western trans self-representation, a river whose expansion has given us, from its initial runnel of autobiographies, science fiction writers, poets, stand-up comedians, young adult novelists, comics writers, and cartoonists.

Yet Morris also places herself in a tradition of English aesthetes and prose stylists, stretching back hundreds of years, from Thomas Browne to Gilbert White, Virginia Woolf to Charles Lamb. She’s part of trans history because she’s part of trans literature, and she’s part of trans literature because she’s part of literature more broadly. She invites us to pay sustained attention not just to what she says but to her way of saying it.

Here, for example, is Morris on Everest: “In the morning it is like living, reduced to miniscule proportions, in a bowl of broken ice cubes in a sunny garden. Somewhere over the rim, one assumes, there are green trees, fields and flowers; within the bowl everything is brilliant white and blue. It is silent in there. The mountain walls deaden everything and cushion the hours in a disciplinary hush.” And here she returns to Venice: “Sometimes, after dinner, especially if friends from home were with us, reckless and laughing with wine we would creep down the stairs of the old palace, braving the chinks of light which, surreptitiously revealed from chained door or curtained window, testified to the unremitting interest of our neighbors and unfastening the boat from its mooring in the side canal, with difficulty we would start up its engine and sail down the Grand Canal, past the great bulk of the Salute, until, as though we were passing into some undiscovered country, we entered the wide lagoon.”

If you enjoy that sentence—and I do—more joy awaits, not only in Conundrum but amid Morris’s fifty-five (not a typo; there are at least that many) other books, many about places (Oxford, Venice, Wales, Sydney, Manhattan, India), most not overtly about gender. Two more collections of Morris’s essays and diary entries will appear in 2021. If, on the other hand, you want beautiful insights about being trans, you can also find them in the authors name-checked above, and many more. There are many ways to be trans, to come out, to enjoy the lives and the bodies trans people can have. The one in Conundrum is the one I found first.

Read our Art of the Essay interview with Jan Morris in our Summer 1997 issue.

Read excerpts from Jan Morris’s diaries in our Summer 2018 issue.

Stephanie Burt is a poet and critic and professor of English at Harvard University. Her books include After Callimachus: Poems, Don’t Read Poetry, Advice from the Lights: Poems, and the essay collection Close Calls with Nonsense, which was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award. Her work has appeared in such publications as the London Review of Books and the New York Times Book Review. She serves as poetry coeditor for The Nation.

January 28, 2021

The Most Appalling, Appealing Psychopaths

In her column, Re-Covered, Lucy Scholes exhumes the out-of-print and forgotten books that shouldn’t be.

Here’s a question: Can you name the debut novel, originally published in Britain in September 1965, that became a more or less immediate best seller, and the fans of which included Noël Coward, Daphne du Maurier, John Gielgud, Fay Weldon, David Storey, Margaret Drabble, and Doris Lessing? “A rare pleasure!” said Lessing. “I can’t remember another novel like it, it is so good and so original.” Coward, meanwhile, described it as “fascinating and remarkable,” admiring the author’s “strongly developed streak of genius.” Du Maurier—a writer whose own work is famously mesmerizing—declared it “compulsive reading … Endearing, exasperating, wildly funny, touching and superbly amoral.” Gielgud thought it “full of fascinating characterisation and atmosphere.” Never not in tune with the times, Weldon deemed it “a magical mystery tour of the mind,” Storey “a superb piece of confectionery,” while Drabble described it as “strange and unforgettable … Highly original and oddly haunting.”

Yet despite such heaped adulation, I’m willing to bet that hardly anyone reading this will have heard of the novel in question, though some might be familiar with its author. It’s called The Sioux, and was the work of sixty-six-year-old Irene Handl, a famous British actress beloved for her roles on both stage and screen, rock ’n’ roll superfan (and member of the Elvis Presley fan club), fellow of the Royal Geographical Society, not to mention a devoted Chihuahua owner and for many years president of the British Chihuahua Club.

The blurb on the British first edition describes the book as “a sustained tour-de-force, one of the most unusual and remarkable novels of recent years.” Unusual and remarkable is spot-on. “The Sioux” is the nickname the Benoir family call themselves, on account of their fierce tribalism. They’re French—their ancestors escaped Paris during the Revolution, fleeing first to Martinique then, during a slave insurrection, from there to Louisiana—feudal, and astronomically rich. Both The Sioux, and its sequel, The Gold Tip Pfitzer (1973)—which is dedicated to Noël Coward—are two of the maddest novels I’ve ever encountered. The Benoirs themselves are among the most appalling and repugnant, monstrously overprivileged, egomaniacal psychopaths ever created. To be absolutely honest, I’m not sure these books should actually be republished—the misplaced cultural appropriation of their chosen soubriquet is, if you can believe it, one of the Benoir family’s least egregious crimes—but, just like Drabble before me, now that I’ve read them, I simply haven’t been able to stop thinking about them.

Even the very existence of these novels is something to be marveled at. Handl apparently first put pen to paper when she was nineteen, while in Paris in the twenties, but abandoned the project after only writing a few pages. It wasn’t until the early sixties, while taking a much-needed break from her stage career due to exhaustion, that she found the time to return to her notebooks and finish working on the story she’d begun all those years earlier. (It was another enforced rest that then afforded her the opportunity to write The Gold Tip Pfitzer.) And what she wrote also defied expectation. Who would have thought that a middle-aged British actress famous for playing working-class stereotypes, from meddling landladies to browbeaten wives, would write a sui generis chef-d’oeuvre of high-camp Southern Gothic? Readers today will recognize an ambiance akin to that found in Patrick deWitt’s “tragedy of manners,” French Exit (2018), or the idiosyncratic style of Wes Anderson’s feature films, though compared to the vicious maneuvering of the Benoirs, the dysfunctional Tenenbaums look as picture-perfect as the Waltons.

These novels aren’t just the feat of an impressive imagination. Handl proves herself an original and flamboyant stylist, oscillating between vaudevillian slapstick, demented dark horror, and passages of sheer—if extravagantly baroque—poetry. Perhaps unsurprisingly for an actor who excelled at character parts, The Sioux is driven by dialogue. And what dialogue it is! A Franglais like no other, sprinkled with private endearments and bon mots, the meaning of which are usually known only to the family, with a dash of “Ol’ Kintuck,” “Creole,” and “Miss’ippa” thrown in for good measure. This is more a novel in speech than anything else, not least because if you strip away all the melodrama and the gaudiness, plot is actually pretty thin on the ground. It takes a while for this lack of story to sink in for a reader though, as the showy voluptuousness of the prose enfolds one in a cloying, claustrophobic embrace. Handl writes in the present tense, sharply shifting back and forth between the interior monologues of her various characters, adding to the muggy intensity of the reading experience.

*

Where to begin ? Well, first things first, with the Benoirs themselves, I suppose, which isn’t at all as easy a task as you might imagine, since each and every one of them goes by a befuddling number of different names (coupled with the fact that, as appears to be an unfortunate side effect of a family that’s as inbred as this one, everyone’s pretty much called some form of the same name to begin with). The novel opens with a transatlantic telephone conversation between the head of the family, Armand-Marie Xavier Benoir (also known as Benoir, Herman, Hermie, and Nap)—who’s at his home in Paris—and his sister, Marguerite (also known as Mimi, Mim, Mi, The Governor of Alcatraz, and Breadcrumb)—who’s at hers in New Orleans, having just arrived back from her honeymoon. Marguerite is only twenty-six but she’s already on her third marriage. Her latest husband is an English banker named Vincent Castleton (most often referred to as Vince, or “Poilu,” on account of his body hair, which apparently distinguishes him from the Benoir men, whose skin is “as smooth as silk”), a likable if often bemused gent who’s clearly bitten off more than he can chew when it comes to the machinations of his dreadful in-laws.

The topic of the siblings’ conversation is Marguerite’s son, nine-year-old Georges-Marie Benoir—also known as Georges, Marie, Little Benoir, Petit-Monsieur, The Dauphin, Puss, Moumou, Old Duck, Little Ducky, Old Dear, Old Man, Old Daddy, Old Darling, Mim’s Chap, His Nibs, King Nutty, Woozy, The Wizard, Mimi’s Flirt, Little Rubbish, Waxy Willie, and Thingo. His father was Marguerite’s first husband, her cousin Georges Benoir, whom she married when she was only sixteen and who perished shortly thereafter in a racing car accident. Armand, incidentally, is also married to his cousin; another Marie Benoir, just to make things even more confusing—here I can’t help but think of Claude Lévi-Strauss’s description of incest as “bad grammar” in the “language of kinship.” The Benoirs’ linguistic acrobatics certainly defy all manner of rules and traditions. That said, a marriage to a first cousin is this family’s idea of expanding their gene pool, especially since there’s more than a whiff of something unnatural about Marguerite and her son’s relationship (in the same way that there was between Armand and his and Marguerite’s mother, while she was still alive). By the time we get to The Gold Tip Pfitzer, the fact that Armand and Marguerite often share a bed is just one of the many shocking discoveries that leaves Castleton reeling.

So, Moumou—who, while his mother and his new stepfather were on their honeymoon, was left in his uncle’s care in Paris—is the heir to the Benoir fortune, but he’s also desperately ill, suffering from acute monocytic leukemia. Not that this is immediately made clear. At first, it’s hard to work out whether we’re dealing with a case of Munchausen Syndrome by proxy, staggering maternal neglect, or just the wild whims of so much wealth and privilege. Marguerite’s beauty is matched only by her cruelty. One minute she’s ordering around servants and relatives alike in the service of the darling Dauphin, instructing them to serve him champagne and oysters in bed or feed him nothing but Vichy water, biscottes, and cognac; the next she’s telling people not to fuss over him. “I don’t spoil him,” she protests. “I love him far too much to let him make a nuisance of himself.” What on earth, wonders poor Castleton—who’s as yet barely met his stepson—has he let himself in for?

Yet, when Marguerite’s son finally arrives in New Orleans in the flesh—deathly pale and very small for his age, the very picture of innocence in his impeccably tailored snow-white sailor suit—Castleton is surprised to find that the boy is a delight. Sure, he’s a little highly strung, but who wouldn’t be with a family like his? What he absolutely isn’t is the precocious brat that Castleton—and the reader—had been expecting. Incidentally, the boy’s arrival is truly majestic. He and his entourage—his valet, his nurse, his beloved foster sister, Dédé (conceived by George’s wet nurse so there would be a ready supply of milk for the little princeling), his personal detective (don’t even ask!), Marguerite’s two French chauffeurs, and Armand, who’s brought with him his two valets as well as his pet capuchin monkey, Ouistiti (who has a penchant for furiously masturbating while perched on his master’s shoulders)—tumble out of two tricolor-flying white Rolls Royces (the second of which is referred to as “The Ambulance” because it’s been fitted out with a bed for the miniature invalid).

Initially, everything looks peachy. How delighted Marguerite must be to have her beloved son by her side once again, even if he does look “spooky as hell and deliciously ready for the mortician.” But at the same time, her mandate for complete obedience doesn’t exactly scream doting mother. Unmoved by the genuine and loving bond forged between her two best boys, she demands that Georges call Castleton “Papa.” The poor little chap is in agony, he can’t bear to disappoint her, nor can he bring himself to call his new friend the name that belongs to his dear dead father only. Given Handl’s confusing emphasis on her characters’ many pet names, it’s weirdly fitting that one character’s refusal to use a particular moniker should be the fulcrum on which the novel’s plot turns. Castleton himself doesn’t mind what Georges does or doesn’t call him—nor does he understand the fuss his new wife is making—but Marguerite is resolute, so she whips little Moumou into submission, an act of astonishing violence that leaves his tiny, delicate hands a bloody pulp.

The sustained ferocity of the scene is truly shocking—rivaled only by the episode depicting Georges’s death in The Gold Tip Pfitzer, a gruesome, screwball caper as the dying child is chased around a bathroom in the middle of the night, hemorrhaging from a nosebleed of horror-movie proportions and eventually dying in Marguerite’s arms, mother and child soaked in blood and mucus. Here, there’s little evidence of maternal love, even twisted. The little boy collapses in pain and despair, while Marguerite’s awful fury escalates with each blow:

He falls to his knees.

She says in a terrible voice: “Get up or I will surely kill you.”

She hauls him to his feet, still crying: “Jamais, jamais de ma vie,” and beats him till she can beat him no more.

He shrieks out in a high sweet voice like a terrified bird. “Don’t whip me, mama! O, you will kill me with that thing! Pas plus, pas plus, maman-chérie!“

He has slipped down on to the floor, but she has still got hold of his hand. She beats it till she is satisfied. “Will you dare to disobey like that again? Will you dare?”

*

Although the scene is undoubtably appalling, it’s not, I’m afraid to say, entirely unexpected. The whip—grimly known as a “soupir d’amour” because the noise it makes “is supposed to resemble the sighs of a young girl in love”—appears, like Chekhov’s gun, in the novel’s second chapter. Small enough to lie “coiled in [a] drawer like a baby snake,” it’s a horrific relic of the family’s ugly past, originally used to “discipline” the slaves on their plantations on the Mississippi Delta. This, then, is the original sin to which all the amorality, cruelty, and vice exhibited by the current Benoirs can be traced back to. It’s sobering enough to understand that the family’s immense wealth is awash with the blood of those they enslaved; but the fact that this remains such a blind spot for everyone involved is especially hard to stomach. The Benoirs aren’t just incapable of self-reflection, it’s much worse than that: they’re all laboring “under the impression they are still living in pre-secession and are happy to spend the rest of their lives up to the eyebrows in Spanish moss.” Georges’s nurse, Madeleine—whom Marguerite insists on calling “Mammy”—is, like many of the family’s servants, directly descended from slaves on their plantations, and she’s not treated much better than her ancestors were. And Marguerite’s vileness when it comes to Madeleine’s daughter, Dédé—whom Georges loves like a sister and likes to sleep beside at night—is quite physically painful to read.

This is an illustration of how the legacies of slavery reverberate through the generations; not simply how long-ingrained systemic inequality is near impossible to escape, even if we like to claim times have changed, but of how the cruelty and violence that white slave owners enacted on their Black slaves with such impunity was then replicated and continued for years to come. But at the same time, if ever there was a book that needed some serious trigger warnings, this is it. Handl certainly deserves recognition as a writer of uncommon talents. These were the only two books she published, though I sorely wish she’d had the time and energies to have produced more, if only to have seen whether she could dream up anything to rival the Benoirs. And yet, no amount admiration can detract from the disturbing horror she portrays.

Castleton’s marriage to Marguerite only lasts fourteen months, but his entanglements with the Benoirs leave him feeling “like the sole survivor of a mine disaster.” That is more or less what I felt like myself after turning the final page and resurfacing, shell-shocked and decidedly worse for wear, back into the real world (which is saying something given the absolute state of things right now). Reading these books is a visceral experience, an assault on the senses. From her indulgent descriptions of dinner tables overloaded with delicious gourmet delights, to the fragrant enchantments of a courtyard garden in the early evening—“where all the brilliant flowers have been freshly sprayed for the night, the callas and the cannas and the belles de nuit, and the begonias and the bignonias and the Cherokee roses, and where the fountain is splashing away like fun among the palmetto fans”—it all builds to a near-suffocating crescendo, one that ultimately left me slightly nauseated and gasping for breath. “I dislike people that think a terrible lot of money,” Handl said, when asked about the origins of her grotesque fictional creations. “Except they’re very funny, and I write about them nastily.” No one could try and claim that Handl expresses any sympathy with her characters; the only problem here is that sometimes their nastiness outweighs hers.

Read earlier installments of Re-Covered here .

Lucy Scholes is a critic who lives in London. She writes for the NYR Daily, the Financial Times, The New York Times Book Review, and LitHub, among other publications.

In the Green Rooms

Little known in the U.S., the writer Tove Ditlevsen (1917–1976) is widely beloved in her native Denmark. She wrote dozens of books of fiction, nonfiction, and poetry, but her crowning literary achievement is the Copenhagen Trilogy, a trio of frank, riveting memoirs published stateside by Farrar, Straus and Giroux earlier this week. An excerpt from the third volume, Dependency, newly translated from the Danish by Michael Favala Goldman, appears below.

Tove Ditlevsen. Photo courtesy of Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Everything in the living room is green—the carpet, the walls, the curtains—and I am always inside it, like in a picture. I wake up every morning around five o’clock and sit down on the edge of the bed to write, curling my toes because of the cold. It’s the middle of May, and the heating is off. I sleep by myself in the living room, because Viggo F. has lived alone for so many years that he can’t get used to suddenly sleeping with another person. I understand, and it’s fine with me, because now I have these early morning hours all to myself. I’m writing my first novel, and Viggo F. doesn’t know. Somehow I think that if he knew, he would correct it and give me advice, like he does all the other young people who write in Wild Wheat, and then that would block the flow of sentences coursing through my brain all day long. I write by hand on cheap yellow vellum, because if I used his noisy typewriter, which is so old it belongs in the National Museum, it would wake him up. He sleeps in the bedroom looking out on the courtyard, and I don’t wake him until eight o’clock. Then he gets up in his white nightshirt with the red trim, and with an annoyed look on his face, he walks out to the bathroom. Meanwhile I make coffee for both of us and butter four pieces of bread. I put a lot of butter on two of them, because he loves anything fattening. I do whatever I can to please him, because I’m so thankful he married me. Although I know something still isn’t quite right, I carefully avoid thinking about that. For some incomprehensible reason, Viggo F. has never taken me in his arms, and that does bother me a little, as if I had a stone in my shoe. It bothers me a little because I think there must be something wrong with me, and that in some way I haven’t lived up to his expectations. When we sit across from each other, drinking coffee, he reads the newspaper, and I’m not allowed to talk to him. That’s when my courage drains away like sand in an hourglass; I don’t know why. I stare at his double chin, vibrating weakly, spilling out over the edge of his wing-tip collar. I stare at his small, dainty hands, moving in short, nervous jerks, and at his thick, gray hair which resembles a wig, because his ruddy, wrinkle-free face would better suit a bald man. When we finally do talk to each other, it’s about small, meaningless things—what he wants for dinner, or how we should fix the tear in the blackout curtains. I feel glad if he finds something cheerful in the newspaper, like the day when it said people could buy alcohol again, after the occupying forces had forbidden that for a week. I feel glad when he smiles at me with his single tooth, pats my hand, says goodbye, and leaves. He doesn’t want false teeth, because he says that in his family men die at fifty-six, and that’s only three years away, so he doesn’t want the expense. There’s no hiding the fact that he’s stingy, and that doesn’t really match the high value my mother put on being able to provide. He’s never given me a piece of clothing, and when we go out in the evening to visit some famous person, he takes the streetcar, while I have to ride my bicycle alongside it, speeding along so I can wave to him when he wants. I have to keep a household budget, and when he looks at it, he always thinks everything is too expensive. When I can’t get it to add up, I write “miscellaneous,” but he always makes a fuss about that, so I try not to miss any expenses. He also makes a fuss about having a housekeeper in the mornings, since I’m home anyway, doing nothing. But I can’t and won’t keep house, so he has no choice. I feel glad when I see him cut across the green lawn toward the streetcar, which stops right in front of the police station. I wave to him, and when I turn away from the window, I completely forget about him until he shows up again. I take a shower, look in the mirror, and think to myself that I am only twenty years old, and that it feels like I have been married for a generation. It feels like life beyond these green rooms is rushing by for other people as if to the sound of kettledrums and tom-toms. Meanwhile I am only twenty years old, and the days descend on me unnoticeably like dust, each one just like the rest.

After I get dressed, I talk with Mrs. Jensen about lunch and I make a list of what needs to be purchased. Mrs. Jensen is taciturn, introverted, and a bit insulted that she’s not alone in the house anymore, like she used to be. What nonsense, she mumbles, that a man of his age would marry such a young girl. She doesn’t say it so loud that I have to answer, and I can’t be bothered to listen to what she says. I’m thinking about my novel all the time, which I know the title of, though I’m not completely sure what it will be about. I’m just writing; maybe it will be good; maybe not. The most important thing is that I feel happy when I’m writing, just as I always have. I feel happy and I forget everything around me, until I pick up my brown shoulder bag and go shopping. Then I’m gripped again by the morning’s vague gloom, because all I see in the streets are loving couples walking hand in hand and looking deep into each other’s eyes. I almost can’t bear the sight of it. I realize I’ve never been in love, except for a brief episode two years before, when I walked home from the Olympia Bar with Kurt, who was going to be leaving the following day for Spain to take part in the civil war. He might be dead now, or maybe he came back and found himself another girl. Maybe I didn’t really have to marry Viggo F. to make it in the world. Maybe I only did it because my mother wanted me to so badly. I poke a finger into the meat to see if it feels tender. This is something my mother has taught me. And I write on my little notepaper what it costs, because I’ll forget before I get home. When the shopping is done and Mrs. Jensen has left, I put everything out of my mind so I can hammer away at the typewriter, now that it won’t disturb anyone.

My mother comes and visits me regularly, and together we can be pretty silly. A couple of days after I got married, she opened up the closet and looked through Viggo F.’s clothes. She calls him “Viggomand,” because she has just as much trouble as other people calling him by his real name. I can’t do it either, because there is something immature about the name Viggo when it’s not referring to a child. She held all his green clothing up to the light and found a set that was so moth-eaten, she thought it couldn’t be worn anymore. Mrs. Brun could use this to sew me a dress, she concluded. It was never any use to oppose my mother when she made a decision like that, so offering no resistance, I let her leave with the clothes, hoping that Viggo F. wouldn’t ask about it. Sometime later we visited my parents. We don’t do that very often, because there’s something about the way Viggo F. talks to them that I can’t stand. He speaks loudly and slowly, as if to mentally disabled children, and he searches carefully for subjects he thinks might interest them. We visited them, and suddenly he prodded me with a confidential elbow in my side. What a coincidence, he said, twirling his mustache between his thumb and forefinger. Did you notice that the fabric of your mother’s dress exactly matches a set of clothes I have hanging in the closet at home? Then my mother and I dashed from the room and burst out laughing.

During this period I feel very close to my mother, and I’m not harboring any deep and painful feelings about her anymore. She is two years younger than her son-in-law, and they never talk about anything except how I was as a child. I don’t recognize myself at all in my mother’s early impressions of me; it’s like they’re talking about a different child altogether. When my mother comes to visit, I stuff my novel away in my locked drawer in Viggo F.’s desk. I make coffee and we drink it while we chat. We talk about how good it is that my father has gotten steady work at the Ørsted factory, about Edvin’s cough, and about all the alarming symptoms from my mother’s internal organs, which have plagued her ever since Aunt Rosalia’s death. I think my mother is still pretty and youthful. She’s petite and her face is nearly wrinkle-free, just like Viggo F.’s. Her permed hair is thick as a doll’s, and she always sits on the edge of her chair, with a straight back and her hands on the handles of her purse. She sits the same way Aunt Rosalia always did when she only was going to stay “a brief moment,” and then didn’t leave until several hours had passed. My mother leaves before Viggo F. comes home from the fire insurance company, because he is usually in a bad mood then and doesn’t like it if anyone is here. He hates his work at the office and he hates the people there, too. He has something against everyone, I think, unless they happen to be artists.

After we’ve eaten and gone over the household budget, he usually asks how far I’ve come with The French Revolution, which is supposed to be part of my basic education, so I make sure that I have read at least a few new pages in it. After I’ve carried out the dishes, he lies down to rest on the divan, and I glance at the blue globe outside the police station, which illuminates the deserted courtyard with a glassy light. Then I roll down the shades, sit down, and read Carlyle until Viggo F. wakes up and wants coffee. While we drink it, and if we don’t have to go out to visit some famous person, a strange silence spreads between us. It’s as if everything we might have said to each other was used up before we were married, as if we spent all the words that ought to have lasted the next twenty-five years; because I don’t believe he’s going to die in three years. The only thing occupying my thoughts is my novel, and since I can’t talk about that, I don’t know what to talk about. A month ago, just after the occupation started, Viggo F. was alarmed because he thought the Germans were going to arrest him, since he had written an article in the Social-Demokraten about the concentration camps. So we talked about what might happen. And in the evening his equally frightened friends, who had similarly troubled consciences, came by. But now they all seem to have forgotten about the danger, and they live mostly as if nothing ever happened. Every day I’m afraid that he will ask me if I have finished reading his manuscript for the new novel he’ll be sending to Gyldendal Publishing. It’s lying on his desk, and I’ve tried to read it, but it’s so boring and wordy and full of knotty, incorrect sentences, that I don’t think I will ever be able to get through it. That also makes the atmosphere between us tense—that I don’t like his books. I’ve never said that out loud, but I’ve never praised them either. I’ve just said that I don’t understand much about literature.

Though our evenings at home are sad and uniform, I still prefer them to the evenings with the famous artists. When I am with them I’m gripped by shyness and awkwardness, and it’s as if my mouth were full of sawdust, because it’s impossible for me to come up with clever answers to their jovial remarks. They talk about their paintings, their exhibitions, or about their books, and they read aloud poems they have just written. For me, writing is like it was in my childhood, something secret and prohibited, shameful, something one sneaks into a corner to do when no one else is watching. They ask me what I am writing at the moment, and I say, Nothing. Viggo F. comes to my rescue. She’s reading right now, he says. You have to read an awful lot to be able to write prose, and that will be the next thing. He talks about me almost as if I weren’t present, and I’m relieved when we finally get up to go. When he’s with famous people, Viggo F. is a completely different person—cheerful, self-confident, witty—just like he was with me in the beginning.

One evening, out at the home of the illustrator Arne Ungermann, they mentioned wanting to gather together all the young people who are published in Wild Wheat, since they are most likely very lonely, scattered around Copenhagen. They would probably be happy to get to know one another. Then Tove could be the head of the association, says Viggo F., giving me a friendly smile. Thinking about that makes me happy, since otherwise I only see young people when they venture out to us with their work, and they barely even glance at me then, since I’m married to this important man. My elation frees up my tongue and I say it could be called “The Young Artists Club.” The idea draws general applause.

The next day I find the addresses in Viggo F.’s notebook, and in a few brief phrases I write a very formal letter in which I suggest a meeting at our home one particular evening in the near future. Then I deposit all the letters in the mailbox beside the police station, imagining how happy they will be, because I think that they’re poor and lonely like I was not long ago, and that they’re sitting in ice-cold, rented rooms all around the city. It occurs to me that Viggo F. knows me quite well after all. He knows I’m tired of only being around old people. He knows that I often feel suffocated by life in his green rooms, and that I can’t spend my entire youth reading about the French Revolution.

—Translated from the Danish by Michael Favala Goldman

Tove Ditlevsen was born in 1917 in a working-class neighborhood in Copenhagen. Her first volume of poetry was published when she was in her early twenties and was followed by many more books, including the three volumes of the Copenhagen Trilogy: Childhood (1967), Youth (1967), and Dependency (1971). She died in 1976.

Michael Favala Goldman is a widely published translator of Danish literature, a poet, educator, and jazz clarinetist. More than a hundred of his translations have appeared in such journals as Harvard Review, World Literature Today, and Columbia Journal. Among his sixteen translated books are the Water Farm Trilogy, Farming Dreams, and Something to Live Up To: Selected Poems of Benny Andersen. His first book of poetry, Who has time for this?, came out in 2020. He lives in Northampton, Massachusetts.

Excerpted from Dependency: The Copenhagen Trilogy: Book 3 , by Tove Ditlevsen, translated by Michael Favala Goldman. Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Copyright © 1971 by Tove Ditlevsen & Gyldendal, Copenhagen. Translation copyright © 2019 by Michael Favala Goldman. All rights reserved.

January 27, 2021

The Lioness of the Hippodrome

In Susanna Forrest’s Écuyères series, she unearths the lost stories of the transgressive horsewomen of turn-of-the-century Paris.

Céleste Mogador as a countess (wikimedia commons)

My horse carried me like the wind. I couldn’t breathe; I hugged his neck, like jockeys do; I called out to him; he leapt forward again … I was going to overhaul my companions, maybe win the race! This idea transported me. I threw my horse against the ropes at the turn … I blocked the woman who was pressing closest to me and I passed her! I was so happy that, for fear of seeing the other woman beat me, I closed my eyes, left everything to my horse and spurred his left flank. I heard them say: She has won!

That’s Élisabeth-Céleste Venard looking back on her first race as a stunt rider at the Hippodrome at the Barrière de l’Étoile outside Paris in 1845. At the time she was twenty, already notorious, hired to titillate the new arena’s eight thousand spectators in sidesaddle hurdle races, costumed parades, and chariot chases. She hared around for another circuit, took her winner’s bouquet, and breathed, “France is mine!” All eyes were on her, and her “nom de guerre,” Mogador, was on every tongue. “Mlle Céleste has a mischievous little face that exposes itself quite happily to the public’s lorgnettes,” wrote one critic.