The Paris Review's Blog, page 125

February 10, 2021

Isn’t Black Representation What We Wanted?

“Don’t you think it’s funny how now the people making these ads get it?” I say to my best friend, my voice cradling the words “get it” with invisible quotation marks. We’re watching television, something we do together often now, grateful to be in each other’s bubble. “What?” she replies, looking up from her phone. “The models,” I say. “Oh, I know,” she says. We’ve been friends for twenty-eight years. She knows what I mean without my having to explain.

After yet another murder, one salve seemed to be representation. Between announcements of our crumbling democracy and more and more people dying, there were now ads with smiling Black faces. Black girls with crowns of 4c curls. Black women running businesses. Black men walking hand in hand down a suburban street with their Black and biracial daughters. It makes you wonder why Black people had to die in order to see ourselves reflected.

The Thanksgiving issue of The New Yorker features a little Black girl with a blue iris flower in her Afro holding an American flag with her sleeves rolled up. I’m caught off guard by the emotion it elicits. It makes me want to frame it. Keep it and one day show my daughter, if I have one. I stand in my mother’s house looking at the cover and wonder: Why does such a quotidian image make me want to cry? It isn’t just that it’s beautiful in the midst of the year’s chaos and pain. It’s because I can’t help wondering what it might have been like for me and my friend to grow up with images such as this one on a magazine like this one. Perhaps then I wouldn’t have been so caught off guard. The image could just have been beautiful, not uncommon.

Isn’t this what you wanted? That’s what I imagine the executives who made these decisions asking. Yes, but not at this price. I smile at the images, I’m glad for them, but they needn’t have come like this. They should have come before this. Without this. The taste in my mouth is bittersweet. I hate that guilt and corporate desire fuels change, rather than genuine understanding. Because if you understood, it wouldn’t have taken a murder of eight minutes and forty-six seconds to get us here.

In Pretend It’s A City, Fran Lebowitz tells Martin Scorsese that she doesn’t understand people who complain about not seeing themselves in books. “A book is not supposed to be a mirror,” she says, “it’s supposed to be a door.” I understand the sentiment, but I disagree with the argument. It’s the type of sentiment that can only be felt by someone who was unknowingly represented almost everywhere she turned. She didn’t know what she had.

In a conversation at the New York Public Library, Lebowitz talks with her friend, Toni Morrison, and the two discuss a bygone era of “the common reader,” people who used to be more open to receiving and entering the imaginary world of books, regardless of whether they spoke to the reader’s own experiences. “Many readers are looking for some replica of their lives,” Morrison says, a point, she notes, Fran herself makes often. But whereas Lebowitz writes in the second person as a resistance to inviting the reader in, Morrison says, “I am the reader of the books I write.” “Your other readers aren’t you,” Lebowitz pushes. And Morrison, laughing, replies, “Yes, they are.” She wants to invite the readers in, so that even though her books may not be exactly about their own lives, they represent a version of the world as she saw it. A version that was missing. Her books offer both a door and a mirror.

I didn’t read books as a child and demand to know, Where am I? The issue was that few books assigned to me in school ever said, Here you are. As a young person, I grew used to the books chosen in school where Blackness was present only if it was pointed out. The pointing it out was the point: it removed the idea that Blackness could ever be the default. Remember the jolt and pit you felt when you read that word in a book that your teacher described as a classic?

In 1959 James Baldwin wrote, “What the mass culture really reflects is the American bewilderment in the face of the world we live in.” If any word describes 2020, it may as well be bewilderment. There is the saying, “You can’t be what you can’t see.” But perhaps more accurate would be to say, “You notice what you don’t often see.” Walking down the street, a white man I passed yelled that my hair looked like Minnie Riperton’s. He meant it as an insult. I replied, “Thank you.” It is no accident our society requires legislation like the CROWN Act, which prohibits race-based discrimination based on hair. It is a direct reflection of the lack of representation.

As tempting as it may be to stew and worry about what might have happened if a segment of America had never woken up, it feels more productive to feel gratitude. Gratitude for the children who will hopefully grow up in a society that offers both mirrors and doors.

Because when people talk about representation, or reflections, or mirrors, they don’t mean, Replicate my exact experience. They mean, Make it ordinary to see someone who looks like me. Make it as common as it once was to see a friend. Make it so that I don’t even notice.

Maura Cheeks is a writer and researcher from Philadelphia.

Presenting the Finalists for the 2021 PEN America Literary Awards

This morning, PEN America released the 2021 Literary Awards Finalists. More than forty-five imprints and presses are featured on the list, with half of the titles coming from university and indie presses. Twenty books are from writers making their literary debuts, and half the titles among the open-genre awards are poetry collections. Chosen by a cohort of judges representing a wide range of disciplines, backgrounds, identities, and aesthetic lineages, these fifty-five Finalist books represent a humbling selection of the year’s finest examples of literary excellence.

The stories on the Finalists lists are about parents, grandparents, and grandchildren, about siblings and their rivalries. These writers share the lives of people who are nonbinary and people who are transgender; people of all ages with changing bodies; immigrants and citizens and people seeking refuge; a basketball legend; a young woman who plucks factory chickens smooth; a tugboat driver; and Phillis Wheatley, America’s first Black poet. Writers and translators lay soldiers, veterans, and scientists to the page. They show us an Algerian bookstore owner, a ranger-naturalist in the Great Western Divide, the first 999 women sent to Auschwitz, a mother named Ivory Mae who bought a yellow house for her family, and a DREAMer named Gina. They write of the first and last stargazers, and ask us to look up.

From the deepest fathoms of the ocean to the Mexican American borderlands; from southeastern Nigeria, Hawaii, colonial Jamaica, and China to contemporary Salt Lake City, Harlem, and weight-lifting gyms; from the Gambia to 1770s Boston; from Colombia, Iran, Taiwan, and French-occupied Algiers to a greenhouse in Sweden; across rivers and into the underworld; from Australian rainforests to Alaskan estuaries, the deserts of Saudi Arabia, and nineteenth-century Edo, Japan; and from Lisbon to Angola—connected by curling strands of hair—these stories, whether real or imagined, tell the truth.

In these stories we see the banality of daily life. We see families, legends, religious rites and cleansing; we see burials, wildfires, knife blades, emperors, gods, and divine favor; false teeth, sobriety, and addiction; sexual manners and vulgarities, magical flowers and their nectar, mythology, and queer dreams. We are shown the limits of American assimilation, the search for home, and migration as “an ancient and lifesaving response to environmental change, a biological imperative as necessary as breathing.” We hear whale songs transmitted over ocean waves. We read interdisciplinary poetics, newspaper clippings, imagined and factual obituaries, technological escapes and collapses, faked deaths and stolen identities, the murder of Black men, and the horrors of the suburban imagination.

Amid what is for many the most challenging time of their life, we remember through these books the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, the Tiananmen Square massacre, the transatlantic slave trade, the 1961 state-sanctioned drownings of Algerians in Paris, and the establishment of our global caste systems, and we recognize how our history has made our present. These books tell of real people, of a reality far beyond an expired canon. They remove barriers and show us our connected humanity.

These books reveal to us the world. Read them. Read their stories.

—Jane Marchant, literary awards program director for PEN America

*

PEN/Jean Stein Book Award ($75,000)

To a book-length work of any genre for its originality, merit, and impact, which has broken new ground by reshaping the boundaries of its form and signaling strong potential for lasting influence.

Judges: Vievee Francis, Fred Moten, Tommy Orange

Borderland Apocrypha, Anthony Cody (Omnidawn)

The Death of Vivek Oji: A Novel, Akwaeke Emezi (Riverhead Books)

Be Holding: A Poem, Ross Gay (University of Pittsburgh Press)

The Freezer Door, Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore (Semiotext(e) / Native Agents)

Sharks in the Time of Saviors: A Novel, Kawai Strong Washburn (MCD)

*

PEN Open Book Award ($10,000)

To an exceptional book-length work of any literary genre by an author of color.

Judges: Toi Derricotte, Brandon Hobson, Katie Kitamura, Jamil Jan Kochai, Akil Kumarasamy, Solmaz Sharif

A Treatise on Stars, Mei-mei Berssenbrugge (New Directions Publishing)

Un-American, Hafizah Geter (Wesleyan University Press)

Wild Peach, S*an D. Henry-Smith (Futurepoem Books)

Small Press Distributions

Inheritors, Asako Serizawa (Doubleday)

How to Pronounce Knife: Stories, Souvankham Thammavongsa (Little, Brown and Company)

*

PEN/Robert W. Bingham Prize for Debut Short Story Collection ($25,000)

To an author whose debut collection of short stories represents distinguished literary achievement and suggests great promise for future work.

Judges: Ben Marcus, Elizabeth McCracken, Ingrid Rojas Contreras

Alligator & Other Stories, Dima Alzayat (Two Dollar Radio)

Adults and Other Children: Stories, Miriam Cohen (Ig Publishing)

You Will Never Be Forgotten: Stories, Mary South (FSG Originals)

A House Is a Body: Stories, Shruti Swamy (Algonquin Books)

Further News of Defeat: Stories, Michael X. Wang (Autumn House Press)

*

PEN/Hemingway Award for Debut Novel ($10,000)

To a debut novel of exceptional literary merit by an American author.

Judges: Ramona Ausubel, Jack Livings, Stuart Nadler

These Ghosts Are Family: A Novel, Maisy Card (Simon & Schuster)

Luster: A Novel, Raven Leilani (Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

Shuggie Bain: A Novel, Douglas Stuart (Grove Press)

Sharks in the Time of Saviors: A Novel, Kawai Strong Washburn (MCD)

How Much of These Hills Is Gold: A Novel, C Pam Zhang (Riverhead Books)

*

PEN/Voelcker Award for Poetry Collection ($5,000)

To a poet whose distinguished collection of poetry represents a notable and accomplished literary presence.

Judges: Sherwin Bitsui, Cynthia Cruz, Terrance Hayes, Claudia Keelan, Bao Phi

Conjure, Rae Armantrout (Wesleyan University Press)

Obit, Victoria Chang (Copper Canyon Press)

The Age of Phillis, Honorée Fanonne Jeffers (Wesleyan University Press)

Kontemporary Amerikan Poetry, John Murillo (Four Way Books)

Blessed as We Were: Late Selected and New Poems, 2000–2018, Gerald Stern (W. W. Norton & Company)

*

PEN Award for Poetry in Translation ($3,000)

For a book-length translation of poetry from any language into English.

Judges: Daniel Borzutzky, Marissa Davis, Meg Matich

Lean Against This Late Hour, Garous Abdolmalekian (Penguin Books)

Translated from the Persian by Ahmad Nadalizadeh and Idra Novey

Raised by Wolves: Poems and Conversations, Amang (Phoneme Media)

Translated from the Chinese by Steve Bradbury

Sense Violence, Helena Boberg (Black Ocean)

Translated from the Swedish by Johannes Göransson

Katabasis, Lucía Estrada (Eulalia Books)

Translated from the Spanish by Olivia Lott

A New Orthography, Serhiy Zhadan (Lost Horse Press)

Translated from the Ukrainian by John Hennessy and Ostap Kin

*

PEN Translation Prize ($3,000)

For a book-length translation of prose from any language into English.

Judges: Jacqui Cornetta, Somrita Urni Ganguly, Ana L. Méndez-Oliver, Amanda Sarasien, Niloufar Talebi, Sevinç Türkkan

Our Riches, Kaouther Adimi (New Directions Publishing)

Translated from the French by Chris Andrews

That Hair: A Novel, Djaimilia Pereira de Almeida (Tin House)

Translated from the Portuguese by Eric M. B. Becker

Ornamental, Juan Cárdenas (Coffee House Press)

Translated from the Spanish by Lizzie Davis

Girls Lost, Jessica Schiefauer (Deep Vellum)

Translated from the Swedish by Saskia Vogel

A Country for Dying: A Novel, Abdellah Taïa (Seven Stories Press)

Translated from the French by Emma Ramadan

*

PEN/Diamonstein-Spielvogel Award for the Art of the Essay ($15,000)

For a seasoned writer whose collection of essays is an expansion on their corpus of work and preserves the distinguished art form of the essay.

Judges: Sandra Cisneros, John D’Agata, Adam Gopnik

Had I Known: Collected Essays, Barbara Ehrenreich (Twelve)

Unfinished Business: Notes of a Chronic Re-Reader, Vivian Gornick (Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

Nature Matrix: New and Selected Essays, Robert Michael Pyle (Counterpoint Press)

Terroir: Love, Out of Place, Natasha Sajé (Trinity University Press)

Maybe the People Would Be the Times, Luc Sante (Verse Chorus Press)

*

PEN/E. O. Wilson Literary Science Writing Award ($10,000)

For a work that exemplifies literary excellence on the subject of the physical or biological sciences and communicates complex scientific concepts to a lay audience.

Judges: Nassir Ghaemi, Christine Kenneally, Erin Macdonald, Banu Subramaniam

The Bird Way: A New Look at How Birds Talk, Work, Play, Parent, and Think, Jennifer Ackerman (Penguin Press)

Fathoms: The World in the Whale, Rebecca Giggs (Simon & Schuster)

The Last Stargazers: The Enduring Story of Astronomy’s Vanishing Explorers, Emily Levesque (Sourcebooks)

The Next Great Migration: The Beauty and Terror of Life on the Move, Sonia Shah (Bloomsbury Publishing)

Owls of the Eastern Ice: A Quest to Find and Save the World’s Largest Owl, Jonathan C. Slaght (Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

*

PEN/Jacqueline Bograd Weld Award for Biography ($5,000)

For a biography of exceptional literary, narrative, and artistic merit, based on scrupulous research.

Judges: Nicholas Buccola, Karl Jacoby, Nell Painter, Anna Whitelock

Black Spartacus: The Epic Life of Toussaint Louverture, Sudhir Hazareesingh (Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

MBS: The Rise to Power of Mohammed bin Salman, Ben Hubbard (Tim Duggan Books)

The Sword and the Shield: The Revolutionary Lives of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr., Peniel E. Joseph (Basic Books)

999: The Extraordinary Young Women of the First Official Jewish Transport to Auschwitz, Heather Dune Macadam (Citadel)

Stranger in the Shogun’s City: A Japanese Woman and Her World, Amy Stanley (Scribner)

*

PEN/John Kenneth Galbraith Award for Nonfiction ($10,000)

For a distinguished book of general nonfiction possessing notable literary merit and critical perspective that illuminates important contemporary issues.

Judges: Roxane Gay, Thomas Page McBee, Dunya Mikhail, Eric Schlosser, Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, Laura Wides-Muñoz

The Yellow House, Sarah M. Broom (Grove Atlantic)

Deported Americans: Life after Deportation to Mexico, Beth C. Caldwell (Duke University Press)

Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Riotous Black Girls, Troublesome Women, and Queer Radicals, Saidiya Hartman (W. W. Norton & Company)

Hidden Valley Road: Inside the Mind of an American Family, Robert Kolker (Doubleday)

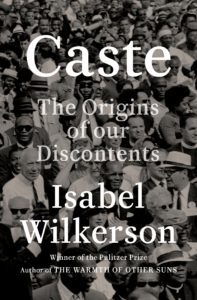

Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents, Isabel Wilkerson (Random House)

Learn more about the 2021 PEN America Literary Awards.

February 9, 2021

The Art of an Even Keel

Photo: Mairead Small Staid

In the torpor of the past ten months, I’ve found myself missing most those things I rarely did before. I miss the grand galleries of art museums, though the nearest is more than an hour away and trips have always been sporadic. I daydream about travel, about the tenuous camaraderie of the airport screening line, the stratus-brushed horizon beyond the window, the world narrowed to a seat, a tray, a book, a bubble of time removed from the world and set ever so gently aside. What I miss, I think, is less action itself than the likelihood of action—or of accident. Even as the pandemic spans four seasons, some underlying transformation (or its potential) is absent; some kinetic possibility is missing in each changeless change. I miss, I want to say, the cusp of things, even as I know this to be a meager complaint amid the litany of real loss. That needling lack remains. And so, seeking some approximation of museum or airport, I’ve turned to the closest thing I have—my shelves—and there found a book on the work of the Italian artist Max Coppeta.

Piogge sintetiche is the book’s title, Synthetic Rain, and the unit of measure for the work within is the drop, caught upon vertical or horizontal planes. Coppeta’s synthetic rain is made of crystallized liquid, suspended on sheets of glass, paper, wood, methacrylate, or PVC. Rare is the solitary drop; they come in trios or quartets or scattered crowds. I would call them by the collective noun of patter, flung over a black or bronzed or transparent background or, in certain pieces, spread across a line of upright and parallel planes, one drop to each sheet, as if this rain did not fall but fly, its path tracked in glassine intervals like a sleek, modernist update on Muybridge’s birds.

The largest of these pieces is titled Long Drop, singular, though the work is composed of dozens of bubbles of crystallized liquid arrayed the length of a platform, one to each dedicated sheet of glass. The drops look like stuttered steps of the same breath, bubbles spilling from an absent diver’s mouth. My eyes move from one plane to the next as if in order, though the planes are concurrent. The title gives lie to their separation, to a world in which we expect to see a thing as it is and not as it is, was, and has been all at the same time. The illusory simplicity of nature—a plain, pretty droplet of rain—gives way to a demonstration of physics, a breakdown of space-time. Coppeta splits the drop. Like light, carrying the possibility of both particle and wave, his work possesses both sequence and simultaneity, simultaneously. Were you in the same space as this work, you could face it; you could stand at one end of the domino-like line of sculptures and stare it down, nose to nose with the flat-headed end of time. Were you in the same space, you could circle it, sidelong.

I am not in the same space. I’ve never seen Coppeta’s work except through the photographs printed in this book. “In a painting, words are of the same cloth as images,” says René Magritte, and in the glossy folds of an artist’s monograph, sculptures are of the same cloth as the words pinned to the page beside them. They are pixels described by other pixels, equally confined, and I lose the thread of my thought in all this representation, every drop doubled in the words written about it—the book’s, my own—like the hall of mirrors at a fairground I wandered through last year—no, the year before last, now. Piogge sintetiche, the cover reminds me every time I turn to it, and I think: Coppeta’s crystallized liquid is rain in the way the word rain is rain—but it’s possible I’ve been reading too much Magritte. It is January in Minnesota, and the only rain I’ve seen in months is this synthetic variation; outside, the snow accumulates.

Coppeta’s pieces, says the critic Antonello Tolve in his accompanying essay, “demonstrate a profound form of ataraxia.” My dictionary defines the word as “peace of mind,” but I read it first in Sarah Bakewell’s biography of Montaigne, and her definition is engraved in my mind, whole and unalterable: “the art of maintaining an even keel.” The word figures greatly in the glossary of my days—I am indisposed to an even keel, often veering too far to one side (depression) or the other (hypomania). Ataraxia, my husband reminds me, for I’ve shared the word with him, when he senses the ship of my mind listing into frenzy; ataraxia, he says, hands cupped around my shoulders, as if the metaphor might be made literal and my mental state steadied along with my physical form. Funny: there’s no need for such a reminder when I’m tipping instead toward misery—then I try to right myself, desperately, but cannot manage.

For some of October and all of November and much of December, I could not manage.

I bought the book from a small museum in my husband’s hometown, where we visited his parents a few years ago, when we, almost unthinkingly, bought tickets, boarded an airplane, and traveled almost two thousand miles at a speed that could peel asphalt from the earth. The museum hadn’t existed when my husband was a child and a teenager, and we were cheered by this sign of someone’s bright commitment to art and thought in the desert. I bought a reckless number of items (given my small suitcase) from the tiny gift shop, feeling rich in my desire to keep the place there for our next visit. Besides, I wanted to make the unexpected pleasure of the discovery tangible, something I could keep, as we say, for a rainy day. It’s been a rainy day, despite the weather, for ten months now.

Photo: Mairead Small Staid

The book on Coppeta’s work stood out among the others on display, appealing to certain proclivities: given my pick of an artist’s materials, I would choose glass; given my pick of languages, I would choose Italian, which I spoke every day for three months, once, thirteen years ago, and have never spoken since. In the middle of one delight-filled day, I was reminded of others; far from home, I was reminded of the farthest I’ve ever been. I have always liked to think of happiness as synonymous with travel, with art, although the words are insufficient and the routes are hardly foolproof. Places disappoint, and works, and days—though that one didn’t.

The book’s back cover describes Coppeta’s work as “inviting the viewer to move that which is motionless,” and I think, the spine cracked and the pages spread across my lap, of how we speak about freezing time, as if it were liquid—as if the right artist could crystallize it, catching time on a sheet of glass and setting it upright in a gallery. But I’ve been trying to hurry time along, to make it flow or even steam: a physical impossibility, that hastening. I just want to press fast-forward, I’ve said more than once over the past ten months, plaintive and banal, though the days I set as destination—the summer, the fall, the election, the year’s end—kept arriving, however slowly, and revealing themselves in all their inadequacy. The name of the last year, long used as a blunt epithet for the more subtle devastations taking place, has been exposed as insufficient shorthand. Those devastations persist.

The pages before me hold nothing but their own liquid geometries. Caught upright, the drops threaten to slip, to spill, and never do. They shimmer, whether strewn or aligned in strict formations like diagrams articulating the complex principles of what, I do not know. The black or bronzed PVC behind them shines, some secondary illustration of the properties of light, but I like best the series arrayed on clear glass: each drop casts a shadow on the surface behind, a reminder that these barely-there suspensions have heft, and can cause interruption. Coppeta’s background is in set design, a profession concerned with building the world in a few square feet, and I find new rules of nature in the simple, impossible properties of each drop: the edge of it static, unspilling, while the gleams and shadows within and around it shift (I imagine) along with the light. Tolve describes light, in Coppeta’s work, “as a totalising ingredient, as a preferred glue between the work and the space, between the fixity of the object and the movement produced.”

I imagine, I had to add, parenthetically, for I don’t know what any light does upon meeting Coppeta’s drops. I realize the foolishness of my fixation, from afar, on these works of art whose appeal lies in their very dimensionality, in their relation to the air around them and the light source above and the viewer standing before, reflected in the glass surrounding the drops to which she’s been drawn or in the liquid drops themselves. My own shadowy outline is precisely what I do not see in these pages; I can see each piece only from the angle chosen by the photographer tasked with its recording, and the gleams of light limning the edges of every drop do not move as I turn the page. We are, both of us, stuck.

Photo: Mairead Small Staid

Yet I imagine. Perhaps the very lack of my presence there, or the work’s here, is the reason for its pull on me: it requires this imagining. I become an ardent, hardworking collaborator in the museum I struggle to make out of my living room, ignoring the blank gaze of the television and the laundry awaiting folding on the couch. “The cathedral leaves its locale to be received in the studio of a lover of art,” Walter Benjamin wrote. “The choral production, performed in an auditorium or in the open air, resounds in the drawing room.”

It’s not the same, of course. Benjamin said as much, and the difference between the Coppeta pieces I look at and the Coppeta pieces as they are is not unique to these light-strewn sculptures. The aura, as Benjamin called it, of any painted or plastic work is singular and physical and irreplicable. I know this is not how art, any art, is supposed to be encountered, but in this time of limited encounter, I take what I can get. The book is a book, after all, tucked between the writings of John Berger and the notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci on my shelves. I read it as I would read them; I read the photographs of sculptures that are (photographs, sculptures) of the same cloth as the words with which they share the page.

This is not—or not only—a diminishment. Amid the detritus of my own life, rather than within the clean lines of a museum, a sterner corralling of my mind is required—I rise to the task, and am better for it, and feel that I have done something with a day I might otherwise have wasted, as I have wasted so many. Expanse is offered, too, in the way I can make strange musings of these pieces, independent of their reality; there is no chance of being disappointed by the place, the work, or the day, for I have no expectations. Coppeta’s pieces are not large, according to their printed dimensions. But met only in a book, absent the comparison of person or wall, they seem to me massive—life-size, the life provided as metric being my own. I imagine each work stretched to a body’s dimensions, each drop able to be entered like a room. A new room! And myself made new within it.

Photo: Mairead Small Staid

The binding of the book is separating, a rind of useless glue peeling from the place where the sheaf of pages no longer meets the spine. I’ve worn it out, treated it as roughly as Berger’s essays or Leonardo’s notebook entries, and laid it too flat beneath my hands as they busied with their own notebook and pen. It’s kept me company for the last month, this book, while I write stray lines in its vicinity: For we speak, too, of being frozen in time, as if time were the surrounding glacier, and we the ones who long to melt once more. Lines like that. I’m trying to go easy on myself, you see, to maintain the even keel I have only recently regained. I flip through the untethered pages. I peruse.

The book is bilingual, the concise descriptions beside each piece—material, dimensions, where the work is held—rendered in both English and Italian, the same different words repeated throughout: liquido cristallizzato su vetro / liquid crystallized on glass; collezione privata / private collection. I learn or relearn the words; I learn the gaps between the words. The works themselves are full of similarities and repetitions, cognates and translations of shape and form: drops strung like echoes of other drops, planes reiterated. Even certain titles are repeated: Black Box, 2013; Black Box, 2015. In a series called Pieghe / Folds, pieces of black PVC are creased as if they were sheets of paper that once carried notes. Drops cluster or sprawl along each fold, subject to the small gravities of their making. I like these pieces particularly, for they remind me of the human hand at work in sculptures that otherwise might be nature-made, physical or mathematical, acts of God as much as the rain whose shape they gesture toward. The work of making, too, requires many repetitions, a sameness and sameness and sameness that gives way to something, finally, different.

Photo: Mairead Small Staid

You sound happier, my mother says over the phone, gently, for she knows how unhappy I can be. Her statement draws my attention to the truth of it; I’ve always found happiness amplified, not diminished, in my own awareness of it, as if reflecting on the state functioned literally—a reflection like that of glass, doubling whatever is placed before it. Liquido cristillizzato su vetro / liquid crystallized on glass. Though this quality is not possessed solely by happiness—depression is a hall of mirrors—and the method is no guarantee. Doubt still comes knocking in the long gray hours of an occasional afternoon, and my teetering mind threatens to undercut, among other things, its own interest in these sculptures, in these photographs of sculptures, in the words I would write about photographs of sculptures and the happiness, yes, I would find there. Why all this bother, doubt wants to know, shutting the broken book. Aren’t they merely trinkets, desk ornaments, distractions fit for a child? Pretty, sure, but not worth this—this elaboration, this reflection upon reflection.

And perhaps I do read too much into them; I read too much into everything. The drops are days, passing and unpassing, unbearably identical; the drops are people, keeping their distance; the drops are pages or sentences or single words, all I can manage—at times, they seem so flimsy, bubble slipping to bauble in my clumsy mind. At times, they catch the light.

Art needn’t be made of glass to offer such reflection. I’m always trying to pinpoint myself in whatever lies before me, as if each work were a map and a spot on it marked, You are here. Without the art, how would I know? The map of my days lately has been circumscribed and small, and still I’ve been unmoored within it, fragile as a page slipped from its binding. I stare at Coppeta’s work, at that profound form of ataraxia, and hope it might inspire the same in me: not peace of mind but activity thereof, a motion made possible by stillness and light. This is another kind of cusp—from Latin’s cuspis, point or apex—neither the end of one thing nor the beginning of another but the balanced and ongoing frisson where they meet. I think of a ship’s prow cutting through the water, steady yet exhilarating. Even-keeled. Afloat. Wind and spray on a sun-warmed face. I think of the endlessly complicated, endlessly beautiful equations that make such a relation possible, that allow a sustained and sustaining equilibrium between the fixity of the object and the movement produced.

Over the phone, a friend tells me that the large art museum where she works as a curator reopened a few months ago, briefly, before closing again. “In the little bit of time that we were open,” she says, “I’ve never seen people looking so slowly. Everyone who was there really wanted to be there.” I’m reminded that I, too, really want to be here. I, too, am trying to look slowly, far from the museums as I am. I don’t mean this sentence as some sort of recompense, some worth found in these days that have cost so many so much. I only mean that this is how I have survived them, how I have wanted to survive.

Mairead Small Staid is a poet, critic, and essayist living in Minnesota.

Redux: Who Walked Unannounced

Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

Maya Angelou.

This week at The Paris Review, we’re highlighting work by Black American writers in honor of Black History Month. Read on for Maya Angelou’s Art of Fiction interview, John Edgar Wideman’s short story “Sightings,” and Lucille Clifton’s poem “bouquet.”

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, and poems, why not subscribe to The Paris Review? Or take advantage of our current subscription offer, featuring our stylish new notebook—the perfect place to draft love poems, write your novel, or log your reading list. (And you can always just buy the notebook, too!)

Maya Angelou, The Art of Fiction No. 119

Issue no. 116 (Fall 1990)

I try to pull the language in to such a sharpness that it jumps off the page. It must look easy, but it takes me forever to get it to look so easy. Of course, there are those critics—New York critics as a rule—who say, Well, Maya Angelou has a new book out and of course it’s good but then she’s a natural writer. Those are the ones I want to grab by the throat and wrestle to the floor because it takes me forever to get it to sing. I work at the language.

Photo: Carl E. Jepson. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Sightings

By John Edgar Wideman

Issue no. 171 (Fall 2004)

The first time it happened I could forgive myself. Cutting across the hall from my office and glimpsing a man—pale, wearing metal-rimmed glasses, a thin man in a light-colored rolled-sleeve shirt and khaki pants, busy with files he was returning or extricating from a chin-high bank of beige metal cabinets lining the wall to my right, just inside the departmental office—nothing unforgivable about being confused a split second by the sight of someone I knew was dead, dead a good long while, dead and buried two thousand miles away in cold, high Wyoming, the dead man Roger Wilson’s office down and across from mine, fourth-floor Bartlett Hall, the dozen years I’d taught at U.W. …

Photo: Frank Hurley. Courtesy of National Library of Australia from Canberra, Australia. No restrictions, via Wikimedia Commons.

bouquet

By Lucille Clifton

Issue no. 233 (Summer 2020)

i have gathered my losses

into a spray of pain;

my parents, my brother,

my husband, my innocence

all clustered together

durable as daisies.

now i add you,

little love, little

flower,

who walked unannounced

into my life

and almost blossomed there.

If you enjoyed the above, don’t forget to subscribe! In addition to four print issues per year, you’ll also receive complete digital access to our sixty-seven years’ worth of archives . Or take advantage of our current subscription offer, featuring our stylish new notebook—the perfect place to draft love poems, write your novel, or log your reading list. (And you can always just buy the notebook, too!)

February 8, 2021

On Sports Time

Photo: © 3asy60lf / Adobe Stock.

Michael Jordan is facing the camera. It’s May 7, 1989, and Jordan has just made the winning shot in Game 5 of the first round of the NBA playoffs. He is rising, effortless, his legs swinging open like scissors. Craig Ehlo, behind and to the left of Jordan, is sinking, crumpling into profile, making himself thin. Jordan swings his arm in sync with Ehlo; they are nearly perfect mirror images of each other. They hit the ground, magically, at almost exactly the same time, drifting in the same temporal current.

Time in a sporting event is, like accordion bellows, structural and flexible. On some throws the ball seems to stay suspended in the air for a long time, slowing time along with it, and accelerates as it reaches the players, like the moment the last of a liquid gurgles down a drain. On the TV of a bar in the Vienna airport I once saw a goalkeeper let a ball, leisurely struck, slip through his hands and go dribbling into the net; the scoring player swung wildly around, mouth tensed into a perfect circle, eyes blaring at nobody, kicking at the place he had just been standing as if he were abusing himself in the immediate past. A giftedly swift athlete makes others slow more than they themselves seem fast. Often, near the end of close games, time itself becomes a commodity, and infinitely valuable—where before the clock ticked on, ambient, it is now neurotically watched, brooded over, and stopped at strategic points. The moment of this transfiguration is variable, unique to each individual game, and sudden. All at once, it is late, and seconds are to be collected and held like a squirrel hoards nuts.

The annual cycle of sports is an orientating scaffold of my days. It marks and ticks time more viscerally than the calendar. Baseball inaugurates the thaw of winter and ends with the first chill breeze of autumn. When it is too cold for baseball, football surfaces seamlessly, and as the football season progresses, the weather gets colder and colder, descending into a sort of existential starkness. Great clouds of visible breath come streaming from helmets and mingle. Within the football season, Sundays are a center of gravity; in baseball and basketball seasons, the hours of 7 to 10 P.M. are bracketed, with holiday-flavored day games on the weekend. The sports year is a persistent forward motion, in repetition—reified time. Each event opens into and points toward the next, and as games happen they harden and are left dangling like chrysalis husks, becoming mere prelude to the present. Soon enough, the present culminates, selects a champion, and loops round again—another opening day, another Super Bowl—to smudge out the prior event, blur it into the undifferentiated past. As long as the center keeps moving, as long as there is another game and season imminent, the past holds almost no interest except as argument, context, or benchmark for the evaluation of the current moment.

So from March of last year, when the NBA suspended play, to the end of July, when the NBA resumed in a sprawling Orlando compound fortified against the world, there were no major American sports, and I was cut adrift. With little new to talk about except for equivocal, shifting estimates of when play might resume, sports media dug into their archives and filled the programming calendar with old games, which I began to watch obsessively, starved. (I tried, for a few days, to catch live games of the Korean Baseball Organization, airing at 2 and 5:30 A.M.) Sports television became unmoored from time. Switching from channel to channel was a hopscotch through decades—a kaleidoscope of uniforms, hairdos, pad sizes, and video quality. There were airings of games on their anniversaries, single days spanning the arc of one player’s career, faithful presentations of old series in chronological order. The television became, like Borges’s Aleph, a keyhole into the dizzying totality of postwar American culture. In a few hours, you could go from Whitney Houston in a billowing white tracksuit singing the national anthem at the Super Bowl in 1991 as the Gulf War kicked off, to an unseasoned Tom Brady, leggy and awkward as a foal, winning his first Super Bowl in the shadow of 9/11, everything star-spangled, to jumpy black-and-white footage of a batter trotting pigeon-toed around the basepath, fans in suits with rolled-up newspapers, to blurry pillar-boxed video of Magic Johnson and Larry Bird galloping in painted-on shorts, the hardwood color dimmed to a honeyed gold.

A live game is not only the event itself playing out across time but the feeling of that time, the expectations, the anxieties—inaccessible after the fact—and the ineffable charge and transformation that thousands of people expectant and invested and watching together impress upon an event, as a song is heard differently when found on the radio rather than selected personally. A game rewatched, alone and isolated from its chronology, is a different thing altogether, remote and indigestible. An old game is simultaneously complete, the outcome known or knowable, and undetermined, its meaning in part contingent on what is happening, and will happen, in the present tense of live play.

Yet with sports time stopped, the remoteness of these old games fell away, and I soon became heavily invested in them. In lockdown I would structure my day around them, as I had with live sports, and watch them from start to finish like movies, alert for foreshadowing, patterns, callbacks—the theme of the game, its moral. I began treating them as self-contained human dramas, rather than a procession of events that shed their interest as they happened. Knowing the final score of a game, I would watch for moments and decisions—seemingly inconsequential at the time, or the consequences unknowable—in which the outcome was truly determined. A player would miss a shot early in the game that I knew he would make at the end to win it—in the first failure I read the final success. A team would betray fear, a lack of nerve, in a game I knew they would lose, and everything after that faltering seemed to confirm it, the end result a flower sprouting from the soil of that decision. A player whom I knew went on to an undistinguished career would have one game, or even one stretch of time within a game, in which they played perfectly, transcendently. With the subsequent disappointment amputated, the inevitable return to normalcy and mediocrity irrelevant, the momentary greatness existed self-sufficiently. Players who now despise each other were laughing together. Players with no subsequent connection would, for one game, despise each other, throwing elbows and staring with visceral, time-collapsing hatred. A man, now old, would hang in the air for an extraordinarily long time, glide through other players like they were ghosts. There were some games whose details, even their outcome, I had totally forgotten, and I experienced them like they were new. Each game was interesting in itself, known in time but abstracted from its place in a process. No winner to be crowned, no tournament to move through, just an assortment of fragments shored against temporary ruins, each one of which could be picked up and admired. From outside time, with no present tense to flow into, all time seemed to be equally present.

Eventually the seasons picked up where they had left off, time began to whir again, and I gradually lost interest in the old games, a vestigial limb withering away. Once again, they pale in comparison to the present, and I am incapable of recapturing the immersion, like the sense and sensation of a dream slipping away. Yet when I watch a live game now there is the residue of the other way of viewing, a double consciousness—both following the game and thinking of how it will be seen when finished, filed away, and seen alone. Time is in part a human application.

Michael Jordan and Craig Ehlo are tethered to each other in the video for only a moment. After they both land, the camera moves in on Jordan, cutting Ehlo from the bottom corner of the frame, and Jordan stands alone, filling the picture, pummeling the air until his teammates mob him, and he moves. His team would lose two rounds later.

Matt Levin is a writer living in New York.

February 5, 2021

What Our Contributors Are Reading and Watching This Winter

Promotional still from Ethos.

As I searched for new shows to binge during quarantine this fall, I kept forgetting the title of the most recent Turkish Netflix drama. Ethics? Event? Euphoria (no), Eulogy … Ego … What was that show friends had told me to watch?

The English title is Ethos, but the words you see in the opening credits are, of course, in Turkish: Bir Başkadır. Episode after episode, I would rack my brain for a suitable translation—one that fit the idea of ethos, but also matched the delicate world of the show. “It’s Something Else,” I ventured to my partner. Or, “There’s One More Thing.” Or, maybe, simply, “The Other,” as in, an-other-ness? Something about this eight-episode miniseries—its wistful soundtrack, its themes of miscommunication, deflection, silence, and withholding—encouraged me to keep generating my own language for it. I still haven’t looked up the dictionary translation for the Turkish phrase.

Ethos is, admittedly, the first Turkish show I’ve managed to watch past the first episode. I never took to the long and overstated soap operas that played continuously on the TV in the restaurants of my childhood, nor could I get into the flat knockoffs of American shows with equally vague titles, like Intersection. I even struck out with The Magnificent Century—a gaudy historical drama about sex in the Ottoman Empire that I did attempt, in earnest, to enjoy.

What makes Ethos different is, well, everything and nothing, which is part of its running metacommentary. In its better moments, the show uses subtle humor and poignant details to write its characters both into and then out of the roles that it also, inevitably, inscribes. The most memorable scenes revolve around communication set askew: the aristocratic mother who calls her housekeeper by the wrong name, the conservative abla who prays as a way of ignoring her cosmopolitan sister, the ornery young hodja-in-training who tries to flirt by detailing each stop on a bus route through unremarkable neighborhoods of the city.

I appreciated what the show was able to do with a bus route, the way it displaced any celebratory focus on Istanbul’s prominent postcard sites. Rather than marveling at the Hagia Sophia or the Blue Mosque, the camera takes us to the interior spaces of the city: dystopian skyscrapers, dingy suburban nightclubs, sun-soaked Anatolian homes. About halfway through the series, when I saw the Bosphorus lapping up against the glass window of a traditional Ottoman yalı, I nearly choked on my Kombrewcha. I kept trying to figure out where the camera was shooting from, which neighborhood these characters actually lived in. At some point, I thought I could make out the Galata tower in the distance, but I wasn’t too sure.

Although I had to read the subtitles, I could tell the dialogue in Ethos leaned heavily on the fanciful “gossip tense” in Turkish (mish-mush)—a grammar used to describe anything that is only known allegedly, or secondhand. Even with subtitles, the conversations and spaces of the show reveal the thickly layered social and psychological underpinnings of this grammar, what it means to have a “gossip tense” at all. —Sara Deniz Akant

D.H. Lawrence

After last month’s white supremacist convulsion at the Capitol Building, I went back to an essay I’ve read many times by D. H. Lawrence called “Fenimore Cooper’s Leatherstocking Novels.” In the past, mass shootings—school shootings in particular—have brought me to revisit this essay in an attempt to understand what it is about the American psyche that compels us to try to murder each other on a regular basis.

Lawrence’s style is, I don’t know, weird, but after a minute you get used to it. He’s at the podium, preaching. Lots of exclamation points. Be forewarned, his essay’s retrograde colonialist attitudes require reading from an ironic distance, just as we’d read the Leatherstocking novels themselves. My arguments with Lawrence’s approach are part of why I keep returning to this essay, I suspect.

He starts out with that old writing-workshop trick of telling you how much he loves the Leatherstocking novels before ripping them down to the studs. Then he takes some ad hominem shots at Fenimore Cooper, who—pearl clutcher—referred to his writing as “my work.” You can practically see Lawrence’s eyeballs rolling around his head when he writes, “If there is one thing that annoys me more than a business man and his BUSINESS, it is an artist, a writer, painter, musician, and MY WORK.” He accuses JFC of being a liar, a self-deluded dandy, a fake. And then it gets ugly, because Lawrence’s take on the colonialist destiny of white Americans is almost as troubling as the American myths of manifest destiny he’s attacking. But if you can lash yourself to the mast and weather it all, you’ll arrive at the reason I keep rereading this essay: “American Democracy was a form of self-murder, always. Or of murdering somebody else.”

Sure, it’s a metaphor. America is a young snake that has to shed its old, European skin in order to become a slick, vital, wriggling democratic thing. But it’s also as literal as a bullet to the brain. I think I return to this essay as a corrective to my own hope that this country is not by nature a bloodbath, and has not always been. There’s no resolution here, just recognizance and forgetting, repeated endlessly. It’s a reminder to see that which is, not that as I wish it would be. —Jack Livings

Still from Shadow of a Doubt.

“The enemy is within,” remarked House Speaker Nancy Pelosi in a recent press conference; those words rang in my head as I rewatched Hitchcock’s sublime Shadow of a Doubt for maybe the twentieth time. Teresa Wright plays Charlie, the teenage girl who summons her uncle (also named Charlie) to save her family from their drab, boring, bourgeois American lives. But from the moment Uncle Charlie (Joseph Cotten) emerges from a mephitic cloud of smoke at the railway station, we know this is going to end badly. Eventually he is revealed to be a fascist and a sociopath, and he aims to take possession of Charlie’s soul.

Released in early 1943, this is a film about the spread of ideas, about sickness and contamination. Even music is a contaminant here—like the “tune” stuck in Charlie’s head, the one she can’t stop humming, ends up being a sort of rebus for her uncle’s hidden crimes. “I think tunes jump from head to head,” she muses, a line that resonates with Hitchcock’s entire body of work, most prominently in Psycho, in which Mother has “jumped” into Norman’s body, come to take possession of him. Charlie, like Norman, is too open. She is capable of telepathy and communicating across realms. It’s a gift that becomes her curse. Shadow of a Doubt is a kind of horror movie about communication.

I love the odd, creepy subtexts in this movie. I love the twinning of the Charlies, the scherzos of black comedy, the waltzing fin de siècle couples that make semiregular appearances. Teresa Wright gives a pitch-perfect performance—she gets every shade of Charlie’s innocence and disillusionment. Cotten oozes charm and menace. There is a subversive erotic charge to their relationship, an incestuous element Hitchcock doesn’t bother to conceal. “We’re not just an uncle and a niece,” Wright tells the gap-toothed Cotten as he slips the ring of one of his murdered victims on her finger. “It’s something else.” The “something else” that defines their relationship is one of several enigmas at the center of this ravishing, cryptic, unsettling film. — David Adjmi

Still from 16 Days of Glory.

I’ve spent some strange hours recently with Bud Greenspan’s Olympics documentaries, starting with 16 Days of Glory, a five-hour film that chronicles the 1984 summer games in Los Angeles. Greenspan made a bunch of these, starting with the ’84 Olympics and progressing into the twenty-first century. The earliest installments are the most unwieldy and also the most absorbing, as longstanding rivalries and low-profile underdog stories intersect with geopolitics and nationalisms in revealing ways. I also very specifically recommend the opening-ceremonies montage from the film on the 1994 Lillehammer games, which culminates in someone executing a massive ski jump into the arena while holding the lit torch. —Natalie Shapero

I love getting new Song Cave titles in the mail; they’re beautiful objects, always sparking with thought. Most recently, the stripped-down voice of Phan Nhiên Hao’s Paper Bells, translated by Hai-Dang Phan, has been echoing in my head and influencing how I see. The poems curate a kind of object music, knitted by little jumps, that can feel like Apollinaire, like Tranströmer:

Dawn ferments in the alley café

submissive like spoiled fish.

Behind glass pizza melts

foreigners in the age of integration and boxers

haggle in the backpacker district. (“The City of Ant Nests”)

In other poems, such as “Nights Working as a Janitor in Seattle,” Hao’s ironies, which range from the quietly affectionate to the declamatory, both contain and wryly indulge the pathos of exile:

you flee from one floor to the next

all night, a lost soldier

from a throng of defeated immigrants

What sticks with me is the sense of vast stretches of time not condensed into gemmy lyric, but rather indexed in their refusal to cohere. The poems feel consubstantial with the detritus of globalization they so often record. In a materialist ars poetica that feels directed against Heaney’s naturalism, Hao writes, in “Manufacturing Poetry”:

In an afternoon with nothing to do

I sit manufacturing poems

out of sixteen screws, two metal plates,

and four wheels

As in Lorine Niedecker’s “condensery,” there’s a play on the long association of poetry and “nothing,” but there’s also a careful attention to the tiny imaginative possibilities of interstitial time. It’s possible to read the fact that “manufacturing,” i.e., labor, structures even potential leisure time as depressing, or constricting, and perhaps it is, but this is a poem that ends in an impossible victory over such inexorable forces: “Blasting open fate / I tunnel deep.” Making has changed to destruction, modesty to unsustainable bravado. For me, the real poem is in the echoic emptiness after that brash declaration, as the visible poem is reabsorbed by the world that made it. —Noah Warren

Still from The Florida Project

I’d say I don’t mean to always go so hard in the paint for Floridian stories—but that would be a lie. I do. If you haven’t seen The Florida Project yet, you should, right away. It has the atmosphere of a small film, but the emotional and visual impact is astounding, reminiscent of my favorite kind of writing. Quiet, searing, haunting stories. The film essentially explores the lives of Sunshine State residents pushed to the outskirts of their own city by the relentless tourism of Walt Disney attractions (and other parks; Orlando is home to so many). The larger commentary seems to be about capitalism, or at least that’s what I got—how the system drains resources from local communities for the benefit of someone far richer and more powerful a thousand miles away. On the surface, I think the film portrays Floridians and Florida exactly as the rest of the country expects. But as in all things, once we move beyond the layers of our own prejudice, we can come to see the true nature of something or someone sparking underneath, their humanity as visceral as our own. If we allow ourselves, we can see the complexity and awfulness and beauty that define living for us all. 10/10 had me in my feelings, and made me appreciate that sometimes, even when uncomfortable, that’s the best place to be. —Dantiel W. Moniz

‘T’ Space: Opening Celebration for Ensamble Studio with Fast Forward and Marie Howe (July 25, 2020) brings together music, architecture, and poetry in one event. Fast Forward’s musical performance sparked my recent poem, “Dilemma,” in the Winter issue. As I watched Fast Forward tumble across bicycle handlebars, I thought of John Cage, chance, noise, and music. And as I watched Ca’n Terra make a space out of an abandoned stone quarry in Menorca, I thought of transformations on our planet. Finally, in watching and listening to Marie Howe read her poetry, I thought of luminous and precise language. I hope viewing this video gives you as much pleasure as I received. —Arthur Sze

Lately, I’ve been searching for a poetry that can meet my weary attention. Uche Nduka’s Facing You is a collection whose relationship to meaning is abstract, haptic, immediate, associative, and gratifyingly dense all at once. Desire and carnality subsume both his syntax and poetry’s purpose—to plumb experience’s unspoken gaps, to find the phenomena there waiting to bloom. Nduka’s propositions are by turns political and erotic, provocative and punning, as these short, flinty and lushly irreverent poems buzz into focus, linger, flit away. It’s as close to hummingbirds as poetry can be:

What happens, the tumult asks

when you fall through history?

…Why do I throw parties

in the abyss?

“You make sublimity / hot,” he writes, as the poems skip and languish in their “accounting, decanting / of the triple experience.” I’m relieved to find in this work none of exposition’s encumbrances, just voice, cresting into aphorism, embodied in a series of epigrammatic and sonically juicy cadences. Nduka’s poems prompt as much as they describe: “May it not be your thought alone / that is rebellious,” he imparts. In a season of solitude, Nduka’s work reminds me of the lyric’s double pleasure, belonging to itself and to others, and of its many shared mouths, speaking in compact, evocative language like glimmering beads of sweat. —Alicia Wright

Cooking with Andrea Camilleri

In Valerie Stivers’s Eat Your Words series, she cooks up recipes drawn from the works of various writers.

Photo: Erica MacLean.

A police inspector wakes up in his beachfront apartment in Sicily and goes for a long swim, then to the office to confront his day of paperwork and complications: the corrupt officials, the jealous girlfriend, the frequent corpses. He has barely started before it’s time for lunch at the kind of restaurant he likes—one with no decor and the owner’s wife in the kitchen. The inspector is an aggressive, tightly wound man who does his job well. The pleasure that he takes in his food is an escape of a kind, an embrace of life by a person who regularly confronts death. The pleasure the reader takes in him is thanks to such signs of a deeper humanity, which add heft to the tales of murder in an exotic locale.

Many readers will already know that I am speaking of Inspector Montalbano, the creation of one of Italy’s best-loved contemporary authors, Andrea Camilleri (1925–2019). Many will also agree with me that at this point in the winter, the world of politics, and the ongoing COVID-19 nightmare, it’s time for some well-crafted, plot-driven escapism, and Camilleri’s books provide this. Conveniently, there are twenty-six of them, which means long stretches of joy. And that’s even before we start cooking from them.

In Excursion to Tindari, Montalbano opens his refrigerator to discover that his housekeeper has left “caponata! Fragrant, colorful, abundant, it filled an entire soup dish, enough for at least four people.” He consumes it with wine and bread for dinner. Photo: Erica MacLean.

Montalbano was a late-in-life success for Camilleri, a television writer trained for stage and film direction who began publishing novels only in his fifties and didn’t have a hit until a decade later. The first Montalbano book came out in 1994, when Camilleri was almost seventy, and the last one was published posthumously in 2020. The inspector has always been popular in Italy and is becoming increasingly popular in translation. A television series, in Italian with subtitles, is currently available on Amazon Prime, and a Montalbano tourism genre has sprung up in Sicily.

The books’ plots tend toward the lurid—mob bosses, pyramid schemes, kidnappings—but Camilleri prided himself on setting the action in the present day and making connections to the real world of Italian politics and bureaucracy. (One of the funniest running jokes is about the police department’s conversion to computers.) Montalbano’s character has depth: a neurotic mother who died young, a distant father who in old age owned a vineyard, a long-distance girlfriend whom he can live neither with nor without. (For me, part of the drama is continually hoping he’ll dump her—she can’t even cook!) But where the books really stand out is in their evocation of Camilleri’s native Sicily, an effect achieved, in many ways, through the food. It’s also worth mentioning that in the original Italian, the books are layered with humor employing the Sicilian dialect, a pleasure that readers in translation have to forgo.

Rounding the Mark opens with Montalbano thrashing sleeplessly. He notes that for once it wasn’t because he had “bolted down too much octopus a strascinasali or sardines a beccafico the evening before.” Pictured here is the sardine filling. Photo: Erica MacLean.

The detective genre is foodie by nature—watching our hero eat dinner is an easy way to humanize a character about to perform inhuman feats—but Camilleri distinguishes himself by the extreme extent to which cuisine appears in his writing, and in the way his food shows us his native land. The Sicilian regional specialities on his pages are seemingly endless, and thus we learn that Sicily is a breadbasket, with an ancient, layered culture and deep traditions. The maritime bounty of Montalbano’s meals—at one point, he memorably eats a starter of grilled fish followed by a second course of grilled fish—demonstrates that Sicily is an island. We see the farming and animal husbandry traditions in the cheeses: ricotta, pecorino, a hanging bulb–shaped cheese called caciocavallo, and many more. And the wealth of desserts hints at the island’s history as a cosmopolitan hub of medieval Europe: cassata cake, gelato, marzipan pastry stuffed with pumpkin puree, cannoli, an extraordinary variety of named cookies.

The way Montalbano eats, too, tells us about his culture. Sicily, according to Mary Taylor Simeti’s cookbook Sicilian Food, is “a society in which the whole family eats all three meals at home.” Montalbano can’t do that—as a bachelor and a man of his time and place, he does not cook—but he has the next best thing: a housekeeper who cooks his dinners for him and, for his lunches, a favorite restaurant whose cuisine seems of a piece with the housekeeper’s. Not to say that the food is casual—on the contrary, the home cooking is composed. The order and formality of these meals, even at home, indicates a world of tradition, perhaps changing but still steeped in the past. Imagine any American these days sitting down in a restaurant—every day, during work!—to eat two courses of food, uninterrupted.

Simeti’s cookbook is her own “eccentric” historical look at food in Sicily. She includes copious quotations from source materials, starting in the ninth century B.C. with Homer—Odysseus, the first traveler, went to Sicily—and painting a picture of heat, sun, and culinary abundance. Simeti’s research also gives us a living glimpse of the island’s wealth and desirability, a status that led, as she says, to “centuries of foreign conquest and domestic oppression.” She concludes that the conquest and oppression have created an “insular” culture with “terrible density … daunting when it immobilizes the island in the face of its ills” but “fascinating and deeply satisfying when it informs … the actions and rituals of every day”—such as the cooking. Camilleri seems to see the same thing. Montalbano’s quasi-religious eating is the counterbalance to his days of trying to do good in a place where “things never budged, even when there was a storm on the horizon.”

One of the many ways my Sicilian cooking sojourn was not a walk on the beach was that I had to convert all the cooking measurements. Photo: Erica MacLean.

As I read, I began to catalogue dishes by book and page number, and these lists soon sprawled over densely written pages that could provide inspiration for months or years of cooking. Almost everything Montalbano ate was unfamiliar to me, from his favorite snack of càlia e simenza (“a mixture of roasted chickpeas and salted pumpkin seeds,” eaten out of a paper cone) to the sardines a beccafico that cause him to wake with indigestion after having “bolted down” too many the night before. I already knew that caponata is an eggplant dish, but I wouldn’t have known it contains capers, green olives, and cocoa powder and is meant to be served cold. Tinnirùme are gently steamed zucchini blossoms. Cassata turns out to be an iconic Sicilian layer cake meticulously decorated with candied fruit. The frozen version appears at least twice in Camilleri’s oeuvre. Perhaps most tempting was the assortment of cookies: biscotti regina, mostaccioli, tetù, taralli. I could have made a menu of cookies alone.

With much hand-wringing and difficulty setting limitations, I decided to make sarde a beccafico, because I had to have a fish; ditalini with ricotta, pecorino, and black pepper (from a restaurant scene in the book Rounding the Mark), because I also had to have a pasta; “fragrant, colorful, abundant” caponata, to add a vegetable element; a “silversmith’s cheese” from Simeti’s cookbook that uses caciocavallo, one of Sicily’s intriguing cheeses; and lastly, as a challenge, the crazy layered tower of a frozen cassata. Simeti’s recipe suggested that I make the gelati myself.

The winemaker COS, whose red blend is seen here, has been making natural wine in Sicily long before it was cool to do so. Its vineyards are a short drive from the town Montalbano’s fictional town is based on. The white comes from a similar Sicilian coastal region, from a vineyard surrounded by a bird sanctuary. Photo: Erica MacLean.

To complement the meal, my spirits consultant, Hank Zona, suggested two Sicilian wines: a white Sicilia from the importer Mary Taylor and a red Cerasuolo di Vittoria Classico from COS. Zona describes the white as “just a really good Sicilian table wine of the kind they would have sat around drinking in Camilleri’s books.” It’s made from 100-percent Grillo grapes, which are native to Sicily, and has a bright, citrusy, food-friendly profile with a lot of salinity. Mary Taylor specializes in wines by small makers from distinct regions whose wines display the typical qualities of the grape. My red, from the winery COS, is a blend of two Sicilian grapes, Frappato and Nero d’Avola. The former is a grape that makes “lighter, more floral” red wine that’s good to serve chilled; the latter is “more full-bodied and tannic.” Blended, the two grapes have a cherrylike taste, a beautiful red color, and a lot of versatility. COS was started by three friends in 1980 and is now “the benchmark producer in the Vittoria appellation of Sicily,” Zona says, and is recognized as a pioneer of biodynamic winemaking in Italy. Sicilian wine in general is trendy, since high-quality winemaking is relatively new to the island and new makers are doing interesting things with local grapes.

Every one of my dishes brought Sicily a little closer, revealing something about the island’s food culture, provisions, or traditional cooking methods. The sarde a beccafico called for the sardines to be butterflied, despined, and then stuffed with a mixture of bread crumbs, pine nuts, and currants. The flavors remind me of the food of ancient Rome, and after a consultation with my fishmonger, I learned that the deboning is better left to the professionals because sardines have delicate flesh. This dish, intended to be served cold, improved in my refrigerator for several days after I made it. Unlike Montalbano, though, I found that a little sarde a beccafico goes a long way.

My cookbook explains the origins of sardines a beccafico: “The beccafico is a songbird that grows fat and sweet on a diet of figs, as fat and sweet as these sardines rolled about a filling of breadcrumbs, currants and pine nuts, and baked with orange juice and bay leaves.” Photo: Erica MacLean.

For my pasta, I was attempting to re-create a dish Montalbano eats in a restaurant with one of his femmes fatales, but I learned through internet research that this is such a humble preparation that there’s barely a recipe—you toss your cooked pasta with a little ricotta and pasta water, season it, and shave some pecorino cheese on top. Simeti, however, claims ricotta in Sicily is made from sheep’s milk, with the cow-milk variety “considered an inferior version.” I wanted to make some, but I discovered that to start it you need whey leftover from making … pecorino! The two cheeses in my dish were a natural pairing. Ditalini was hard to find—the selection of pasta shapes in the average grocery store is not what it used to be—but I tracked some down at Caputo’s Fine Foods, my local Italian grocery.

Caponata is another dish meant to be served cold, causing me to wonder if the “virtuous Sicilian housewives,” as Simeti calls them, responsible for all those home-cooked meals don’t have all kinds of cold, preprepared dishes up their sleeves, ready to set a quick table when the family returns home for lunch. The dish also calls for red sauce, which certainly would have been premade and canned once a year when the tomatoes were abundant. I bought mine at another legendary specialty shop, A.L.C. Italian Grocery, in Brooklyn.

Still yet a third Italian specialty source—Mia Famiglia, in Millburn, New Jersey—provided me with caciocavallo for my silversmith’s cheese (though actually what I bought was scamorza, a close cousin that also has the distinctive gourd shape achieved by being hung to dry). Caciocavallo, according to Simeti, is “the principal cow’s milk cheese of modern Sicily” and often serves as an accompaniment to pasta instead of Parmesan. The cheese melts slowly and thus is ideal for frying. This dish, seasoned with vinegar, was historically used as a substitute for meat or fish when neither were on hand. The “unusual combination” of cheese and vinegar, Simeti writes, was mentioned by the ancient Greek poet Archestratus as a Sicilian specialty. As a “cheese cutlet” for an easy dinner, I thought it was brilliant.

My cookbook quotes an eighteenth-century traveler’s note that in Sicily the frozen desserts were “so disguised in the shape of peaches, figs, oranges, nuts &c., that a person unaccustomed to ices might very easily have been taken in.” This was my best attempt. Photo: Erica MacLean.

My dessert, the frozen cassata, was an epic project requiring candied zucchini, a layer of sponge cake, a frozen Chantilly cream, three gelati (vanilla, chocolate, and pistachio), and a special metal mold of very specific dimensions that is impossible to purchase online in America. Fortunately, I am an old hand at candying a zucchini, and I have a set of metal bowls that turn out to be extremely useful vintage pudding molds (a score when you need to freeze a cassata or boil a dessert in the style of the British navy). One had just the dimensions I needed. I made the gelati myself because I was curious about Simeti’s recipe, which calls for cornstarch in the base, but unless you’re an expert at making ice cream, I think store-bought would be just as good or better. One benefit to making the gelato was that I was forced to shell and blanch my own pistachios; I was amazed by the increased brightness and freshness of flavor in comparison to the pre-hulled variety. For any dessert involving pistachios, this process is laborious but very worth it.

Did I succeed in opening a portal to Sicily and sitting at the table with Inspector Montalbano? Simeti writes that Sicilian food will never be the same elsewhere, since the local ingredients have a “peculiar intensity of flavor that the island’s merciless sun induces,” without which “almost any Sicilian recipe … will be immeasurably diminished.” Still, I was impressed by my plate’s combination of simplicity, practicality, frugality, and old-fashioned elegance, which seemed so different from the throw-anything-together way we eat today. Even without the smiting flavors of Sicily, the plate had balance, and the disparate items I’d chosen went together as if guided by the hand of an ancient tradition. And my Sicilian wines delivered the climate in a bottle. The meal wasn’t easy weeknight Italian, and it wasn’t even close to my style of home cooking, but it offered a philosophy I think I could learn from. Since a homemade dinner is now truly the best escape available, I was pleased.

Photo: Erica MacLean.

Silversmith’s Cheese

Adapted from Sicilian Food , by Mary Taylor Simeti.

an ear of scamorza cheese, cut into slices 1/2 an inch thick

2 garlic cloves, crushed

1 tbs olive oil

1 tsp vinegar

2 tsp dried oregano

1/4 tsp sugar

Photo: Erica MacLean.

Fry the garlic in oil in a medium-size heavy skillet over medium heat until browned. Discard the garlic, reserving the oil in the skillet. Add the slices of cheese and fry, about four minutes on the first side and two on the second, until brown and crispy. Remove carefully to a serving plate, and sprinkle with the vinegar, dried oregano, and sugar. Serve immediately.

Photo: Erica MacLean.

Caponata

Adapted from Sicilian Food , by Mary Taylor Simeti.

1 1/4 lbs eggplant

salt

olive oil

half a medium-size onion, sliced

3 celery stalks, chopped and blanched for a minute in boiling water

20 pitted green olives, cut in half

2 tbs capers

3/4 cup tomato sauce

1/4 cup (or to taste) white wine vinegar

1 tbs sugar

1 tbs unsweetened cocoa

5 tbs toasted almond slivers

Photo: Erica MacLean.

Cut the eggplant into one-inch cubes, sprinkle liberally with salt, and let drain for an hour. In the meantime, put the sliced onion in a medium-size skillet, and cover with water. Simmer on medium-low heat until the water has evaporated and the onion is beginning to brown. Resist the temptation to add salt at any point during this process; the other ingredients are very salty. Add a tablespoon of olive oil to the onions and fry briefly, then add the celery, olives, capers, tomato sauce, vinegar, sugar, and cocoa powder. Simmer on low for five minutes.

When the eggplant has drained, soak it in cold water to rinse off the salt, and squeeze dry with a kitchen towel. Heat a tablespoon of olive oil in a separate skillet, add the eggplant, and fry, stirring occasionally, until cooked through. Place on paper towels to drain.

Add the eggplant to the tomato mixture, stir to combine, and taste to adjust seasoning. Top with toasted almonds, and serve chilled or at room temperature. (Ideally, you would allow the caponata twenty-four hours in the refrigerator for the flavors to meld, but I did not wait that long.)

Photo: Erica MacLean.

Sarde a Beccafico

Adapted from Sicilian Food , by Mary Taylor Simeti.

12 sardines (see instruction on preparation)

1/2 cup bread crumbs

3 tbs olive oil, divided

2 tbs pine nuts

2 tbs currants, plumped in hot water for five minutes

1 tbs minced parsley

4 anchovy fillets

12 fresh bay leaves

juice of a lemon

juice of an orange

2 tsp sugar

salt and pepper (to taste)

Photo: Erica MacLean.

The sardines must be cleaned and prepared, heads removed, bodies butterflied, bones and spines removed. The tails stay on, and the fins can be cut off last, with scissors. My cookbook suggests that this can be done at home, but since the sardines’ flesh is delicate and the bones are small, this takes a sharp knife and considerable skill. I suggest asking the fishmonger for help. You can cut off the fins (but not the tails—they’re necessary for presentation!) at home with scissors if the fishmonger misses any.

Preheat the oven to 350, and lightly oil an eight-by-six glass baking dish.

Lay out the sardines, and season with salt and pepper.

In a small skillet, fry the bread crumbs in two tablespoons of olive oil, stirring regularly, until browned. Add the pine nuts, currants, and parsley, and season to taste. Take a sardine and, placing it skin side down, put a tablespoon of filling on it and roll it up toward the tail. Place it in the baking dish so the tail is sticking up in the air. Repeat this with the rest of the sardines, alternating them with bay leaves as if they were on a skewer and arranging them in neat rows so they have no room to unroll.

Sprinkle the sardines with lemon juice, orange juice, sugar, and a tablespoon of olive oil. Bake for twenty-five minutes. Serve cold.

Photo: Erica MacLean.

Ditalini with Ricotta

2 cups ditalini pasta

1/2 cup sheep’s milk ricotta cheese

grated pecorino (to taste)

salt and freshly grated black pepper (to taste)

Photo: Erica MacLean.

Cook the pasta al dente, according to the package instructions, reserving the pasta water when you are done.

Place the ricotta in a medium-size bowl, and add a cup of pasta water, stirring to make a creamy sauce. Add the sauce to the pasta, and stir to combine, adding additional pasta water if necessary to create a moist, creamy texture. Season with salt and freshly grated black pepper to taste, garnish with grated pecorino, and serve immediately.

Photo: Erica MacLean.

Frozen Cassata

Adapted from Sicilian Food , by Mary Taylor Simeti.

Note 1: I believe that a perfectly acceptable variation on this recipe would be to use store-bought gelato or ice cream.

Note 2: If you are making your own gelato, start several days ahead of time. And even with store-bought gelato, you’ll need to make the pan di Spagna and compose the dessert the day before you plan to serve it, and allow it to harden overnight.

Note 3: You will need a rounded aluminum or tin mould that is 6 inches deep and 9 inches in diameter. Stainless steel, plastic, and glass do not work as they do not allow the dessert to freeze rapidly enough.

Overall requirements for the cassata:

pistachio gelato, about 2 cups

vanilla gelato, about 2 cups

chocolate gelato, about 2 cups

a three-quarter-inch layer of pan di Spagna (see recipe below)

an eight-inch springform pan

1/4 cup rum (not aged) or sweet liquor of your choice

candied zuccata (see recipe below)

frozen Chantilly cream (see recipe below)