The Paris Review's Blog, page 116

April 28, 2021

Watch a Conversation between Eloghosa Osunde and Akwaeke Emezi

Every year, the Paris Review Board of Directors gives awards to recognize remarkable contributions to literature. One of these, the Plimpton Prize for Fiction, is a $10,000 award that celebrates an outstanding story published by an emerging writer in the magazine in the previous calendar year. The winner of the 2021 Plimpton Prize for Fiction is Eloghosa Osunde, for her story “Good Boy,” which appeared in the Fall 2020 issue.

In commemoration of this year’s Plimpton Prize, we’re presenting a taped conversation between Osunde and the artist and writer Akwaeke Emezi, introduced by managing editor Hasan Altaf. The video, which appears below, will be available to stream on our YouTube channel from April 28 to May 11.

And don’t forget: readers are also invited to stream a special free screening of PBS’s American Masters documentary N. Scott Momaday: Words from a Bear, which will be available until Friday, April 30. Momaday is the recipient of the 2021 Hadada Award, presented each year to a “distinguished member of the writing community who has made a strong and unique contribution to literature.”

April 27, 2021

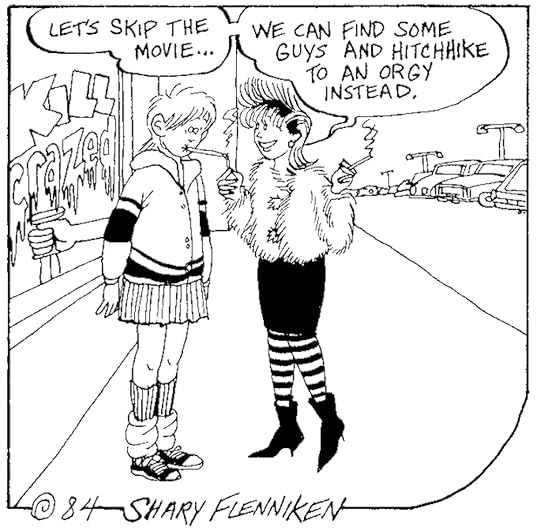

Comics That Chart the Swamp of Adolescence

Copyright © 2021 by Shary Flenniken.

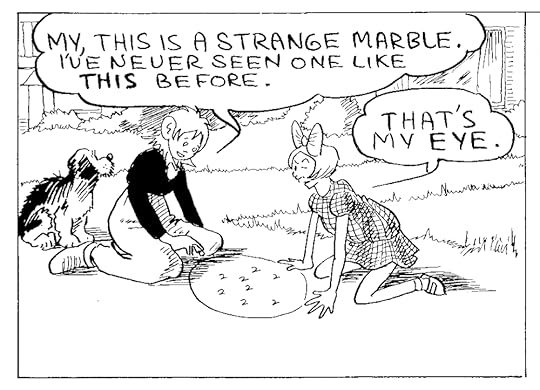

I don’t know how old I was when I first read Shary Flenniken’s Trots and Bonnie, but I definitely wasn’t old enough. I was a precocious reader and pretty sex-obsessed for a child, and my parents would buy National Lampoon every now and again and leave it where it could fall into my unsupervised little hands (parenting was a different animal entirely in 1984, kids). I couldn’t have been more than seven, but the experience is as clear and vital as if it happened yesterday: here was something that looked friendly and kidlike, but it was dangerous. It was confusing, it was weird, and it was very, very hot.

Copyright © 2021 by Shary Flenniken.

By the time I came of age, I had put National Lampoon on my mental back burner. I wouldn’t say I forgot about Trots and Bonnie, but I’d stored it away deep in my subconscious, where it formed a bedrock of my sensibility I wouldn’t recognize until years later. When I reacquainted myself with the strip in my twenties, it was like seeing a long-lost and deeply beloved friend. I also realized I’d been ripping Shary off for years. Those blank Little Orphan Annie eyes, the cheerful willingness to be absolutely disgusting, the heady mix of raunch and innocence—all things that had percolated through my own mind and heart and spilled out into my own work, a dim echo of the masterful original.

Copyright © 2021 by Shary Flenniken.

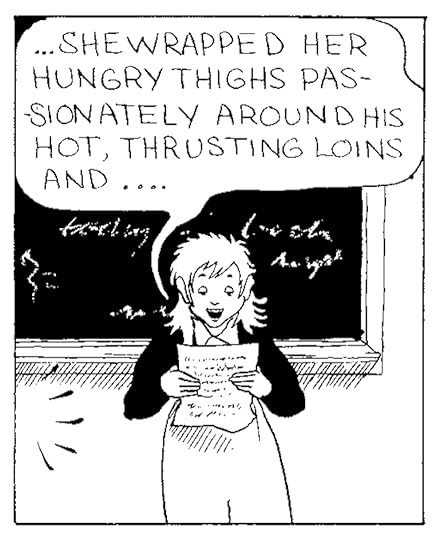

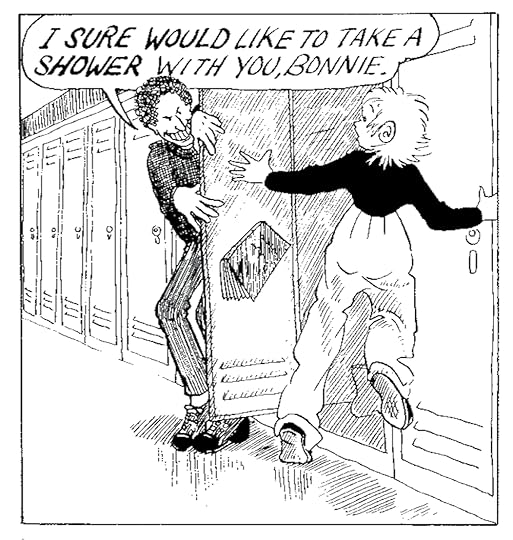

How to explain Trots and Bonnie to the uninitiated? It’s a bit like Little Nemo, if Little Nemo had been drawn for and by pervs. The titular characters are a girl in early adolescence, Bonnie, and her wry, horny dog, Trots. Bonnie stands as a kind of wise-fool character, observing the often hypocritical, sometimes hedonistic world around her with the candor and freshness of a child and the lust of a dirty old man (if parenting was different in the eighties, cartooning was different in the seventies: a strip featuring a young teen rubbing one out to literary porn penned by her dog might raise more lawsuits than eyebrows in today’s cultural climate). Bonnie’s floppy trousers and slouching posture paired with Trots’s smart-cracking wiseacre role have antecedents in Bud Fisher’s Mutt and Jeff. The drawing is lyrical and lovely—all swooping lines and flat textures, like an Erté drawn in the girls’ bathroom at a particularly ill-run reformatory. Flenniken draws like an angel, but, like Caravaggio, prefers the company of sinners.

Copyright © 2021 by Shary Flenniken.

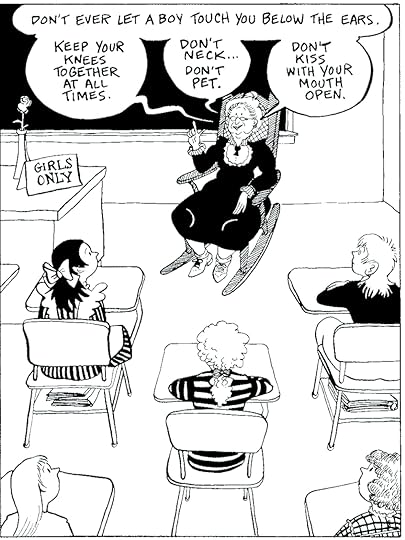

Bonnie’s adventures are more quotidian than Nemo’s, but no less wild. The lands between girlhood and womanhood are weirder and more unsettling than anything Winsor McCay ever dreamed up. The monsters traversing her landscape are real: neighborhood drunks, uncaring parents, and that biggest bogeyman of all, puberty. Yet she moves through the world with amiable good cheer, in danger yet never a victim. Her hair is a semi-androgynous shag; her high-waisted, baggy pants conceal the randy monster that throbs beneath. Her more worldly best friend, Pepsi, dresses in an incongruously childlike pinafore paired with fishnets, a perfect metaphor for the terrifying underage sex fiend she is. When Pepsi rhapsodizes about condoms or proclaims proudly that her perfect gentleman boyfriend has “the smallest cock in all eighth grade,” it’s both hilarious and deeply unnerving. Supporting character Elrod, a younger neighborhood boy, gets the worst of their impulses: shot, mutilated, and drowned like an X-rated Wile E. Coyote. Their world is brutal and lecherous and gross, yet suffused with heart and a fierce solidarity with the point of view of its main inhabitants.

Copyright © 2021 by Shary Flenniken.

What Flenniken understands and brings gleefully to the page is that adolescent girlhood is positively feral and that teenage girls are both threatened and threats themselves. J. M. Barrie tells us in Peter Pan that children are “gay and innocent and heartless,” and that little weirdo had it right—that’s the terrible power of children, the monstrous innocence that makes them capable of anything, a state of being we fatuously describe as “pure.” You dump a bunch of hormones into a child’s body and all of a sudden you have this awful hybrid creature: a changeling with the self-centeredness and nonexistent impulse control of a child but the body and urges of a breeding-age adult. It’s a dangerous time in a young woman’s life, but as with most dangers, it has a messy, chaotic, super-hot fun side as well. To speak frankly of this fun side is tricky for adults, to say the least. We remember it, if at all, as a fever dream, a sticky, humid jungle of lust and stink. Grown-ups have to blind themselves to the sexual power of eighth-graders, for reasons I sincerely hope are obvious. But the kids can see each other head-on, and they wield their sexuality with all the grace and care of a toddler toting an AK-47. Flenniken dares to write and draw from that swamp with a complete lack of adult-world moralizing or editorial restraint. Arguably, “moralizing” and “restraint” weren’t really anyone’s bag when she was creating these strips, but there’s still an audacity in her work that I imagine felt as electrifying then as it does now.

Copyright © 2021 by Shary Flenniken.

Bonnie and Pepsi are obsessed with sex, but they’re not here for the male gaze. Their desire is frank and straightforward and more than a little demented, and it’s depicted with a bracing honesty that feels less like a political statement and more like Flenniken is reporting from the front lines with no filter, no safety net, and no intention of telling anything but the truth. Trots and Bonnie ran into the late eighties, but it was born from a seventies worldview, a decadent, anything-goes carnival where thirteen wouldn’t get you twenty. The hangover from this era was vicious and the societal course-correction necessary, but the importance of hearing from girls of the era rather than from the guys who liked to ball girls of the era cannot be emphasized enough. Bonnie isn’t masturbating on the toilet because she wants you to watch. She’s doing it because her body belongs to her and she’s horny as fuck.

Copyright © 2021 by Shary Flenniken.

As a child I was mystified and entranced by these strips. As a twenty-year-old, I was delighted anew by their bawdy, anarchic swagger and their pie-eyed charm. As a forty-two-year-old, I am so far from the lawless, deeply screwed-up Eden that Trots and Bonnie inhabits that it may as well be documenting life among the Stone Age clans. Part of me wants to call protective services—have I become a scold, or just a mother? Barrie tells us that those who are no longer gay and innocent and heartless can no longer fly. Being earthbound is the price we pay for our experience in this world, perhaps, and maybe to understand danger and value safety is to run the risk of identifying with the wing-clippers of this world. But looking at these strips I feel an echo of that old and savage glee, a distant memory from when I lived in those lands. Would I move back there if I could? Probably not, but we are so lucky to have in Shary Flenniken a cartographer of our most treacherous and rewarding landscapes. Would that we all had such balls.

Copyright © 2021 by Shary Flenniken.

Emily Flake is a cartoonist and illustrator. Her work has appeared in The New Yorker, the New York Times, Time, and many other publications. Her weekly comic strip, Lulu Eightball, has appeared in numerous alternative newsweeklies since 2002. She lives in Brooklyn.

Excerpted from Trots and Bonnie , by Shary Flenniken , published this week by New York Review Comics . Text copyright © 2021 by Emily Flake. All images copyright © 2021 by Shary Flenniken.

Redux: Seventy Memories

Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

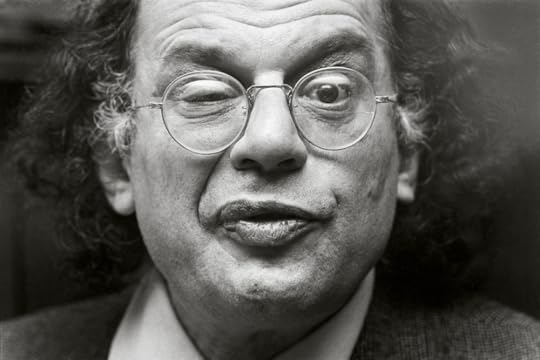

Allen Ginsberg, ca. 1979. Photo: Michiel Hendryckx.

This week at The Paris Review, as National Poetry Month winds down, we’re continuing to celebrate Poets at Work, our latest anthology of interviews. Read on for work by three of the writers included in the book: Allen Ginsberg’s Art of Poetry interview, an excerpt from Susan Howe’s “Defenestration of Prague,” and Derek Walcott’s poem “The Light of the World.” You can also read Paris Review poetry editor Vijay Seshadri’s introduction on the Daily.

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, and poems, why not subscribe to The Paris Review? You’ll also get four new issues of the quarterly delivered straight to your door. Or, subscribe to our new bundle and receive Poets at Work for 25% off.

Allen Ginsberg, The Art of Poetry No. 8

Issue no. 37 (Spring 1966)

You have many writers who have preconceived ideas about what literature is supposed to be, and their ideas seem to exclude that which makes them most charming in private conversation … And the hypocrisy of literature has been … you know like there’s supposed to be formal literature, which is supposed to be different from—in subject, in diction and even in organization, from our quotidian inspired lives.

Photo: Avinash Bhat. CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...), via Wikimedia Commons.

from Defenestration of Prague

By Susan Howe

Issue no. 86 (Winter 1982)

Skeletal kin

tilt

italic lunacy

long illness of little difference

Seventy memories

masks

singing and piping

to be

(half words)

beginning and begetting …

CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...), via Wikimedia Commons.

The Light of the World

By Derek Walcott

Issue no. 101 (Winter 1986)

Marley was rocking on the transport’s stereo

and the beauty was humming the choruses quietly.

I could see where the lights on the planes of her cheek

streaked and defined them, if this were a portrait

you’d leave the highlights for last, these lights

silkened her black skin, I’d have put in an earring,

something simple, in good gold, for contrast, but she

wore no jewelry …

If you enjoyed the above, don’t forget to subscribe! In addition to four print issues per year, you’ll also receive complete digital access to our sixty-eight years’ worth of archives. Or, subscribe to our new bundle and receive Poets at Work for 25% off.

April 26, 2021

Pink Moon

In her new monthly column, The Moon in Full, Nina MacLaughlin illuminates humanity’s long-standing lunar fascination. Each installment will be published in advance of the full moon.

Edvard Munch, Måneskinn (Moonlight), 1895, oil on canvas, 36 1/2 x 43 1/4″. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

An electric blue dusk in an April eight years ago, and a fat full moon was showing off above the trees. I was away from home and walking to a bar to celebrate something privately, and I paused on my way to watch the moon move, its blond glow shifting bonier as it tracked its path higher into the coppery blue. “Beautiful night,” said the bartender when I took a seat. “Beautiful night, beautiful moon,” I said. He poured my drink and an older gentleman on the stool to my right leaned toward me and asked with a sticky blue cheese voice, “What does a young woman like you think of the full moon?” I laughed. Was he asking me if my womb was throbbing? What does anyone think of the full moon? I told him I didn’t know how to answer that question. I’ve been thinking about it since.

It’s April again, surging month, and the full moon rises tonight. What do you think of the moon? Joyce considers “her luminary reflection … her potency over effluent and refluent waters: her power to enamour, to mortify, to invest with beauty, to render insane, to incite to and aid delinquency: the tranquil inscrutability of her visage … her arid seas, her silence.” So: light, power, water, beauty, insanity, delinquency, tranquility, inscrutability, silence. It’s a start. The moon reflects back what we aim at it; what we see there tells us as much about ourselves as it does about this chalky pearl two hundred forty thousand miles away, give and take. “Between us / we had seventeen words / to describe the moon,” writes the poet Arundhathi Subramaniam. I wonder what they were. Let’s see how many we can come up with.

Before that, one word. In more than two dozen languages, the words for month and moon are the same. In Croatian, mjesec; Czech, měsíc; Slovak, mesiac. In Filipino, buwan; in Malay, bulan. In Japanese, 月 (tsuki); Hmong, lub hlis; Maori, marama; Igbo, onwa; and Zulu, inyanga. In Romanian, Estonian, Uzbek, and Turkish: lună, kuu, oy, ay. Our timekeeper, our month maker, our definer of cycles, tetherballing around us in 27.32-day spans. I say our as though we own it, as though it belongs to us, attached to where we are by the invisible bands of gravity. It does not belong to us. If anything, we belong to it, subjects to its rhythms, its pull, its power, the night’s one glowing, slow-blinking eye. Across the world, notions of month and moon mingle and mesh in the very language they’re expressed. You cannot talk about one without talking about the other.

Lună Kuu Oy Ay

I saw it written and I saw it say.

April’s full moon is the Pink Moon, per the Old Farmer’s Almanac, which draws on Native American and Colonial American sources. Pink moon, pink month: April with its cotton candy texture, sweet spun sugar wool. April brings the sense—everything stirring, about to burst or bursting—that one is waking up from a dream, or moving into another one. It “comes like an idiot,” as Edna St. Vincent Millay puts it, “babbling and strewing flowers.” April’s nighttime atmosphere has a distinct flavor to it, too. The blue light of this month’s dusks is thin, metallic, not the take-a-spoonful blue of November dusks. And lamplight through windows on early evening walks is lemony, not the hearthy and inviting orange-gold glow when the year gets colder. Here in the small northeastern city where I live the birds returned some weeks ago, their sour song in the predawn dim getting sweeter as spring makes more of an effort. The Pink Moon refers not to the color of this evening’s moon but to a star-shaped, pink-petaled flower that spreads itself across the continent this month called phlox.

Flocks of rufa red knots, shorebirds with russet breasts, are on the move right now, making their annual nine-thousand-mile migration from Tierra del Fuego up to the Arctic, where they lay their eggs. On the night of the full moon in April, horseshoe crabs, ancient armored beasts of the sea, are drawn to the shores of the mid-Atlantic to lay their eggs. Urged by the swell of the tide and the ultraviolet light of the moon, they travel up from the seafloor and scramble in the sand; waves lap over their spiked shells as they deposit millions of slick, jewel-like sacks of horseshoe matter into the shallow ditches they’ve dug. The red knots depend on these eggs to fuel them for the rest of their journey north. Each year, the birds descend to the beaches of Delaware and New Jersey timed to this state of moon swell and make a great feed, gulping horseshoe eggs by the hundred thousand before they take wing again, heavier, egg-loaded, in this lunar-led triangle of timing and survival. Egg Moon is another name for what’s up tonight.

What’ll hatch? What’ll come out? What’ll crack through the shell and emerge into this busted, blooming world? What blind, hungry, pin-boned pouch of needs? What fresh life? “It’s spring,” writes the poet Ouyang Jianghe, “and everyone’s got something to puke.” April is the year’s heaving dress rehearsal. This month and moon provoke a spewing and strewing, a laying, a seeding, a spreading. At the bottom of Craigie Street, a magnolia tree drops its white and pale-pink goat-tongue petals and the sidewalk is slicked with them as footfalls grind them slimy. I see the petals on morning walks and wonder if the blooms on the tree fold up in the moonlight or stay splayed. “Tonight the moon is full,” writes Clarice Lispector. “Through the window the moon covers my bed and turns everything milky bluish white … I escape by closing my eyes. Because the full moon is light insomnia: numb and drowsy like after love. And I had decided to go to sleep so I could dream, I was missing the news that comes in the dream.”

What news in the dream? My mother tells me she can’t sleep on the full moon. It might be true for me, too, but whether I inherited it in my blood or by suggestion, I do not know. Either way, I like the idea of the full moon as light not being able to sleep. What news in the dream? Limulus polyphemus is the name of the horseshoe crab that the red knots eat the eggs of, named after Polyphemus, the one-eyed giant who smashes Odysseus’s men against the wall of his cave and sucks their brains and bones before Odysseus gouges out his eye and escapes with the rest of his crew tied below fat, woolly rams. Polyphemus because people mistook horseshoe crabs for having one eye. They have ten. All the better to see the ultraviolet rays of the moon with. In 1967, the Nobel Prize in Medicine was awarded to three doctors “for their discoveries concerning the primary physiological and chemical visual processes in the eye.” They focused their research on limulus polyphemus.

The ten-eyed horseshoe crabs are nabbed from the sand, lifted to labs where they’re stabbed in the heart and drained of a third of their blood, which is copper-based and milky blue. It’s collected for the limulus amebocyte lysate found there, which detects bacterial contaminants called endotoxins, lethal even in minor amounts, and used to test whether medical equipment is sterile. If ever in your life you have had a vaccine, it’s been touched by the blood of the horseshoe crab. The crabs, so drained, are returned to the sea. Splish splash. Some live.

No splish-splash to be had in the twenty-two seas of the moon, evocatively named as they are: Mare Nectaris, Mare Fecunditatis, Mare Tranquillitatis, Mare Crisium, Mare Humorum. Seas of Nectar, Fecundity, Tranquility, Crises, and Moisture. Twenty-two seas, one ocean, and a bunch of marshes, bays, and lakes (Lake of Death, Lake of Oblivion, Lake of Sorrow, Lake of Dreams). Nothing watery about them, they’re fields of solidified lava from ancient eruptions, iron rich, dark, and dry as bone. Early astronomers, when they looked, thought the dark parts were water.

Here, the ocean wears all its mirrors on its back, they bring the news that comes in the dream, and tonight, the full moon will be reflected and repeated there, millions of moons bouncing back off millions of mirrors. All the old Aprils are in this April, the well-worn egg-shaped orbit swings us back to budding fizz on trees, to hungry suckling tongues, to the blue dusk blush, everything stirring and sticky with renewal. We can’t stare at the sun. It will char our retinas and take our sight. The moon won’t burn, even at its brightest, we can look and look, the way we look at the faces in dreams, which reflect what we bring, with darkness and emptiness behind them. Tonight, step into the milk-blue dim, get softened in the mothlight, and feel the moon pull on all your fluids and juices.

Nina MacLaughlin is a writer in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Her most recent book is Summer Solstice. Her previous columns for the Daily are Winter Solstice, Sky Gazing, Summer Solstice, Senses of Dawn, and Novemberance.

April 23, 2021

Staff Picks: Motion Pics, Feature Flicks, and Oscar Picks

Still from Lili Horvát’s Preparations to be Together for an Unknown Period of Time, 2020. Courtesy of Greenwich Entertainment.

Lili Horvát’s Preparations to Be Together for an Unknown Period of Time was Hungary’s entry to the Oscars’ Best International Feature Film category, but unfortunately it wasn’t selected. Horvát’s second feature (named after a 1972 underground experimental theater piece) is a sophisticated puzzle of a film, filled with questions concerning the nature of desire, memory, and the human brain. Opening with a quote from Sylvia Plath’s poem “Mad Girl’s Love Song,” the film follows Márta, a highly successful Hungarian brain surgeon living in New Jersey, who returns to Budapest after an unexpected affair with János, a fellow brain surgeon, at a conference. Filled with anticipation, she waits for him at their designated meeting spot, only to be stood up. Worse yet, when she tries to confront him, he claims to have no idea who she is. Did Márta imagine the whole affair, or is János a classic cad, promising the world and delivering nothing? Horvát’s slow, measured shots cut through these possibilities as carefully as Márta cuts through a human brain. Eventually, we arrive at a conclusion that I at first worried was too pat. Reflecting on it now, though, I’m not so sure—this is a film where nothing is as it seems, least of all its characters’ motivations. —Rhian Sasseen

I have no idea what movies came out in 2020. I can tell you that it’s sheer joy to watch George Segal fall for Elliott Gould in California Split, a 1974 buddy movie that, since it happens to be about gambling, is included in the Criterion Channel’s “The Gamblers” series. Segal plays Bill, a moderately fun guy who works in publishing and wears a turtleneck sweater well, while Gould plays Charlie, a guy you’d bail on all your other friends to hang out with—provided you like gambling. But even if you don’t, you’ll like watching these two celebrate each other’s good luck and insist on buying the next round. The movie doesn’t glamorize addiction—Bill and Charlie’s friendship is a bright part of that darker story, and they both know it—but neither does it oversimplify or moralize. You don’t have to be a degenerate to feel impatient during the few scenes in Bill’s office, eager to get back to a game. Perhaps you’ll wax nostalgic for a time in your own life when friends were always available to join you in some variety of irresponsible behavior. The casino could be mistaken for a weird way out of nine-to-five capitalism, at least if you’re lucky—but there’s the rub. —Jane Breakell

Anthony Hopkins as Anthony in The Father, 2020. Photo: Sean Gleason. Courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics.

How terrifying, the descent into dementia, and how discomposing the experience offered up by Florian Zeller’s The Father. Watching the final scenes of the film, I was desperate for a landmark by which to orient both myself and the protagonist, Anthony, played by Anthony Hopkins. If a landmark appears—and we can’t be sure that one does—we discover that any brief orientation can’t alleviate the horror and pain. It may even compound the confusion. We, like Anthony, lose our bearings around each corner, and just as we feel our footing is sure, the ground gives way beneath us. For ninety minutes, his reality is ours. I never thought I’d admire a performance from Hopkins as much as I admire his Mr. Stevens in The Remains of the Day, but he is truly devastating here. It’s a distressing, anxious, and very convincing representation of dementia’s torments. —Robin Jones

In 1971, the People’s Video Theater sent a film crew to document a sleepaway camp for disabled teenagers. Using archival footage as well as present-day interviews with the campers, Crip Camp tells the little-known story of Camp Jened, a radical place where barriers to access were all but nonexistent. This utopian experience empowered the teens who attended, and the film, nominated for this year’s Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature, traces their trajectory from campers at Jened to leaders in the struggle for disability rights. The organizing on the part of these bunkmates-turned-activists resulted in legislation like the Americans with Disabilities Act. I love Crip Camp not only because it draws attention to a rarely discussed movement—it also shows just how formative spaces like Camp Jened can be, especially for young people. Upon returning to the site of Camp Jened (it closed in 1977), the former camper Denise Sherer Jacobson says, “I almost want to get out of my wheelchair and kiss the fucking dirt.” —Mira Braneck

I do not know how the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences decides which films are worthy of its annual awards and which are not deserving of the chance to win a small gilded humanoid. I do know that many exciting films are necessarily ignored by this inherently exclusive celebration. And thinking on such created disparity—Academy darlings versus undesirables—puts me in mind of John Waters’s Cecil B. Demented, a film that lampoons both the perpetually even-keeled filmmakers who produce too many crowd-pleasers for the Hollywood system and the overzealous indie fanatics who rebel against that system with borderline religious fervor. Marvel at one of the lesser-loved works by the master of schlock and shock! Watch a group of cinema terrorists kick off the production of their guerrilla film by nabbing the fictional A-lister Honey Whitlock at her rom-com movie premiere, setting the theater ablaze! Among this ragtag group of celluloid maniacs: Maggie Gyllenhaal as a Satan-worshipping makeup artist, Lawrence Gilliard Jr. as a set designer and diegetic DJ, Michael Shannon as a chauffeur who is inordinately interested in Mel Gibson’s genitalia, and Melanie Griffith, who manages to channel some of that Cherry 2000 B movie magic into her role as an indifferent Hollywood celebrity–turned–sympathizer for the cinematic underground. On Oscar night, instead of wondering why some films are lauded while others are shunned, I will probably just hum this film’s mantra, “Demented Forever,” and watch the shiny figurines go out. —Christopher Notarnicola

Still from John Waters’s Cecil B. Demented, 2000.

A Kind of Packaged Aging Process

Passengers boarding an ocean liner, 1925. Photo: Australian National Maritime Museum, via Wikimedia Commons.

It was for convalescent reasons that I lately undertook a resolutely up-market Mediterranean cruise, with a Greek classical bias, and since I thought of such a cruise generically as being a kind of packaged aging process, at first I decided for literary purposes to rename our ship the Geriatrica. Later I changed my mind.

It was perfectly true, though, as I had foreseen, that we formed a venerable passenger list, and sunset intimations were soon apparent. Hardly had we left the quay than a charming American senior citizen approached me as I stood at the rail, and said that since she heard I wrote books, she thought I might be amused by her favorite quotation from Groucho Marx. “It goes like this,” said she. “ ’Next to a dog, a book is a man’s best friend, but inside it’s too dark to read anyway.’ Isn’t that hilarious? I just love it.” I laughed politely, but I could not help thinking that with the passage of time the tale must have lost something in its telling.

Of course the passage of time had to be a preoccupation on board such a ship as ours. “Facing Up to Rheumatism” was one of our first educational lectures, and for myself I felt that the ancient seas through which we passed, seas of glory, seas of fate, seas where young gods fought and heroes died, were themselves allegories of mortality’s challenge. “Facing Up to Decay,” in fact, might have been a more apposite mantra.

*

Half of us faced up to it cockily. Vivid combinations of lipstick and wrinkle could be observed at the Captain’s Gala Dinner. Nautical-looking veterans with binoculars were up at crack of dawn to sail into Istanbul. Loud accents of the English fifties reverberated over gins and tonics through the Whaleback Bar. Proudly muscular old couples marched their obligatory exercise around the promenade deck (fifteen circuits to the mile) before, having dressed formidably for dinner, they joined their friends for cocktails by the pool.

The other half of us preferred resignation, and more often sat in discreet twos or fours over fruit drinks with flexible straws. They were very likely looking at maps of tomorrow’s classical site, or discussing the recent lecture about Theban mosaics. Some of the ladies wore shawls. Few of the gentlemen wore white dinner jackets. Unless there was a bridge game going, they usually went to bed early.

But the odd truth is, the two categories blended. The metallic bray of the home counties was subsumed into homelier vernaculars, a generally club-like air prevailed, and when the time came for the fancy-dress dance at the Seafarers’ Lounge, it was hard to tell which of my fellow passengers represented Defiance, and which were Resignation. This was because, I gradually came to realize, they were united in toughness, in resolution, and in enthusiasm. They were all there to enjoy themselves, and even the oldest among us, even the ones with Zimmer frames, even the palest convalescents, were out for a good time. They were docile in their obedience to the ship’s rules, but it was a willing suspension of liberty.

By Zeus, how terrific was their energy! Nothing dissuaded them. With earnest diligence they listen to the spiel of the tour guide. Like aging gazelles they spring up the tiers of the Epidaurus theater. We see them vivaciously haggling with Anatolian souvenir sellers, courageously experimenting with the effects of ouzo, returning to the ship loaded down with toys for the grandchildren, talking nineteen to the dozen, and ending the day with an enormous multicourse meal in the Geriatrica’s dining room, for which they boisterously thank the Filipino waiters like old friends and shipmates (which, after half a lifetime of cruises, many of them are).

*

By the time we reached our port of disembarkation, I was quite won over. The sprightly enthusiasm of it all had seduced me: the fertile mix of Carnival and Palm Court, and the determination to make the most of everything. On our last day aboard, that delightful old American lady approached me again. “I knew I’d got that Groucho story wrong. I’ve been thinking about it all this time, and this is how it should go: ‘Outside of a dog, a book is a man’s best friend, but inside it’s too dark to read anyway.’ ”

This time I really did laugh. I marveled that throughout our voyage, in museum, taverna, and Seafarers’ Lounge, she had been assiduously worrying out that joke; and even as she spoke my eyes strayed to the Sunshine Promenade above her head, where the passengers were seizing their last chance of seaboard exercise around the measured mile.

There they were in silhouette, as those gods and heroes might be on a Grecian vase: the mad sinewy sprinter overtaking everyone, the scholarly couple deep in talk, one or two young bloods from the entertainment staff, an old man bowed over another’s wheelchair, several solitary energetic ladies, a few game military men forever arthritically on the march.

I had grown to be proud of them—to be proud of us!—and as I laughed at the Groucho story, and admired that living frieze above us, there and then I renamed our ship. The SS Indomitable, I dubbed her then, and all who sailed in her.

Jan Morris (1926–2020) was a Welsh writer, journalist, and historian. She resided with her partner, Elizabeth Morris, in northwest Wales, between the mountains and the sea. Her many books include In My Mind’s Eye, Coronation Everest, and the Pax Britannica trilogy.

Excerpted from Allegorizings , by Jan Morris. Copyright © 2021 by the Estate of Jan Morris. Used with permission of the publisher, Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

April 22, 2021

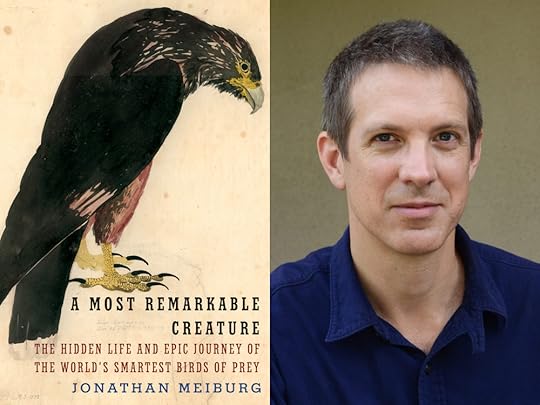

At Home among the Birds: An Interview with Jonathan Meiburg

Photo: Jenna Moore.

Jonathan Meiburg was born in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1976 and grew up in the southeastern United States. In 1997, he received a Thomas J. Watson Fellowship to travel to remote communities around the world, a year-long journey that sparked an enduring fascination with islands, birds, and the deep history of the living world. Meiburg explores these passions in his new book, A Most Remarkable Creature, which traces the evolution of the wildlife and landscapes of South America through the lives of the unusual falcons called caracaras. Like the omnivorous birds at the heart of his book, Meiburg is more generalist than specialist. He’s written reviews, features, and interviews for publications including The Believer, Talkhouse, and The Appendix, on subjects ranging from the music of Brian Eno to a hidden exhibition hall at the American Museum of Natural History. He also conducted one of the last interviews with Peter Matthiessen. But he’s best known as a musician—albums and performances by his bands Loma and Shearwater have earned critical acclaim for many years, often winning praise from NPR, the New York Times, the Guardian, and Pitchfork. In 2018, Meiburg organized and performed in a three-night live reconstruction of David Bowie’s Berlin Trilogy for WNYC’s New Sounds program. He lives in central Texas. This interview was conducted electronically between there and Wilmington, North Carolina.

INTERVIEWER

Recently an anhinga started roosting by the tidal creek that runs through my backyard. It’s fun to watch—the long snaky neck and the way it hangs its wings out to dry like laundry. Once, when the creek was clear, I watched it hunt, and it flew along underwater like a fish. I’ve been told that anhingas aren’t really supposed to be here, or that this is north of their range, which is shifting due to climate change.

MEIBURG

To me anhingas are among the most beautiful birds, and maybe the most like their dinosaurian ancestors of any birds. A lot of people think they’re sort of goofy, and I can see that, too—the tiny heads, the absurdly long necks and flight feathers, the overall sense that they’re a prototype someone meant to refine later. They have wonderful nicknames like “snakebird” and “water turkey.” I love how you can see them soaring way up in the sky for no apparent reason, like ravens with long, skinny necks, even though they make their living wading around on the bottoms of rivers.

They need to stay underwater for a long time, so they have very little oil on their feathers. This helps them sink and stay down. But it means they have to spend a lot of time standing on perches and holding their wings out to dry, which is usually how you see them, and it locks them out of places that get really cold. I was used to seeing them in the southeastern U.S., especially along that elevated stretch of I-10 that crosses the Atchafalaya Basin—but they were thick along the river in southern Guyana when I visited, and they seemed completely at home among colorful, feathered weirdos like parrots, toucans, and capuchin birds.

INTERVIEWER

What role does this movement of animals between South and North America play in your story? I think of it all as one big blob of land with a canal in the middle.

MEIBURG

This question is pretty much at the heart of my book, which starts with Darwin scratching his head about why the striated caracara, a bold, social, curious bird of prey he met at the southern tip of South America, lived there and nowhere else. Trying to figure that out changed the way I thought about the world.

INTERVIEWER

Expand on that, for those of us who don’t instantly make the connection between “strange bird confined to the southernmost part of South America” and “the world.”

MEIBURG

Until I started trying to understand where the caracaras came from, I’d never realized that North and South America, biologically and geologically, are basically strangers to each other. Lumping them together as a single “New World,” as Europeans did, really doesn’t make much sense. Tectonic forces kept the Americas apart for a hundred million years. When they finally joined hands at the isthmus of Panama a few million years ago—a short time, if you’re a paleontologist—two sets of animals who’d pursued completely separate evolutionary journeys confronted each other, which one scientist called “one of the most extraordinary events in the whole history of life.”

Caracaras are part of this story. Like the parrots, their ancestors probably entered South America through the forests of a warm Antarctica, and in the southern New World they mostly play the same roles crows play here—clever, social scavengers, like raccoons with wings. But unlike large crows, which have never found a foothold in South America, caracaras made it to the northern hemisphere thousands of years ago. We’ve found their fossil bones in California and Arkansas, and although they retreated south after people arrived in the Americas, they’re slowly coming north again. The website eBird says they’ve been seen recently in the Outer Banks.

INTERVIEWER

How did you settle on that bird in particular?

MEIBURG

What hooked me was their personality. Beside the fact that they’re big, flashy birds of prey that behave more like crows, striated caracaras just don’t act like wild animals are “supposed” to. They swagger up like they’ve got as much right to be here as you do, and look you right in the eye. If you sit still they’ll start trying to take things out of your bag. I have a little video of one trying to figure out what to do with a pair of hiking poles. They’re utterly and confidently themselves, and they made me realize that the reactions of every wild animal I’d ever seen—hiding or fleeing in terror—weren’t how it always was. Animals had to learn to do that, from bitter experience.

INTERVIEWER

Any chance you’d share that clip?

MEIBURG

Here it is.

I should make clear that by “caracaras” I mean all ten species, a unique lineage of odd falcons that lives mostly in South America. Striated caracaras are the rarest, but they’re all equally wonderful in their own ways. One tropical species, for example, lives in large family groups that raise one chick at a time, and survives on a diet of wasps’ nests and fruit. They all appear in the book. There’s no such thing as “the caracara” any more than there’s a bird called “the eagle.”

INTERVIEWER

You were approaching these birds as a naturalist. When did they turn into a book?

MEIBURG

A long time ago, you told me, “Never write a book if you can help it.” I couldn’t help it. Before I met striated caracaras, I’d vaguely thought scientists knew most of what there was to know about animals, especially animals surrounded by celebrity wildlife like penguins and whales, so I was naively surprised that I’d never heard of these unusual birds, then genuinely surprised at how little was known about them—even though they’d also transfixed Darwin, who wondered the same things. What were they? Why did they act like this? Why did they live at the bottom of the world and nowhere else?

INTERVIEWER

You’ve mentioned Darwin, but surely some other people or peoples noticed them, even so far south.

MEIBURG

Oh, yeah. The Inca emperors were allowed to wear the feathers of Andean caracaras, and dancers dressed as these birds still feature in solstice parades in highland Ecuador and Peru. A crested caracara showed the Aztecs’ ancestors where to build Tenochtitlán—now Mexico City—and Toba people in northern Argentina told an ethnographer from the United States that the supernatural hero Carancho—another name for a crested caracara—entrusted humans with the secrets of fire and medicine.

When you compare that with the way Europeans regarded striated caracaras in the Falklands, it’s hard not to shake your head. Sealers and whalers called them “flying devils,” and the enterprising colonists who turned the islands into a sheep farm the size of Connecticut slapped a bounty on the birds’ beaks, nearly driving them to extinction. A marooned sealer declared them “the most mischievous of all the feathered creation,” and even Darwin called them “false eagles” who “ill become so high a rank.” They’re protected now, and minds are changing—though as I say in the book, I’m not sure how much time they have left if we don’t take some fairly wild measures to save them. There are about the same number of adult striated caracaras as there are giant pandas in the wild.

INTERVIEWER

Is it true that we were once members of a nameless band that did two benefit shows then instantly broke up?

MEIBURG

I’ve never admitted it in public.

INTERVIEWER

Is it also true that you are now in a pretty famous band called Shearwater that just put out a record produced by Brian Eno?

MEIBURG

Not quite. Shearwater has done seven albums for Matador and Sub Pop since 2006, and I’m working on an eighth right now. As for Eno, he mixed the final track, “Homing,” on the most recent album by Loma, a band I started a couple of years ago with Emily Cross as the singer. He shouted out our first record on the BBC at the end of 2018, which helped get us in gear for a second. Weren’t you on the same radio program with him when I saw you last in NYC?

INTERVIEWER

Bri? We’re like the same person. We go shooting. There was a radio thing. Listen, though. Your book grows out of your work as an ornithologist, and your band is named after a bird, and I’ve seen you perform songs about birds. You did one here in Wilmington. What’s it all about?

MEIBURG

Paying close attention to birds draws me out of myself, which I crave more and more as I get older. Music does exactly the same thing—it gives you the feeling of being humbled and exalted at once.

John Jeremiah Sullivan is a contributing writer for The New York Times Magazine and the Southern editor of The Paris Review. His latest work of fiction, “Uhtceare,” appears in the Spring issue.

The Grace of Teffi

The following serves as the foreword to Other Worlds: Peasants, Pilgrims, Spirits, Saints , a newly translated selection of the Russian writer Teffi’s stories, which was published earlier this week by New York Review Books.

Teffi. Photo courtesy of New York Review Books.

There are writers who muddy their own water, to make it seem deeper. Teffi could not be more different: the water is entirely transparent, yet the bottom is barely visible.

—Georgy Adamovich

It is not unusual for a writer to be pigeonholed, but few great writers have suffered from this more than Teffi. Several of her finest works are extremely bleak, but many Russians still know only the comic and satirical sketches she wrote during her first years as a professional writer, from 1901 until 1918. Few critics have recognized the full breadth of her human sympathy, her Chekhovian ability to write convincingly about people from every level of society: illiterate peasants, respectable bourgeois, monks and priests, eccentric poets, bewildered émigrés, and public figures ranging from Lev Tolstoy to Rasputin and Lenin. Teffi also has a remarkable gift for writing about children, for showing us the world from the perspective of a small child.

Throughout her life, Teffi was a practicing member of the Russian Orthodox Church. Both Orthodox Christianity and Russian folk religion, with its poetic understanding of spiritual matters, were important to her. And she recognized that many of her finest stories were those inspired by these themes. In December 1943, she wrote to the historian Piotr Kovalevsky: “Which of my things do I most value? I think that the stories ‘Solovki’ and ‘A Quiet Backwater’ and the collection Witch are well written. In Witch you find our ancient Slav gods, how they still live on in the soul of the people, in legends, superstitions, and customs. Everything as I encountered it in the Russian provinces, as a child.”

Teffi made few such direct statements about her work. I know just one other passage in a similar vein:

During those years of my distant childhood, we used to spend the summer in a wonderful, blessed country—at my mother’s estate in Volhynia Province. I was very little. I had only just begun to learn to read and write—so I must have been about five … What slipped quickly through the lives of adults was for us a matter of complex and turbulent experience, entering our games and our dreams, inserting itself like a brightly colored thread into the pattern of our life, into that first firm foundation that psychoanalysts now investigate with such art and diligence, seeing it as the prime cause of many of the madnesses of the human soul.

These two statements have guided our choice of stories. We have translated all but one of the stories from Witch. We have included the two other stories Teffi mentions: “Solovki,” an account of a pilgrimage to the Solovetsky Islands in the White Sea, and “A Quiet Backwater,” which incorporates a memorable monologue about the patron saints of various birds, insects, and animals. And we have chosen ten other stories on similar themes, many of them from the first of Teffi’s more serious collections, The Lifeless Beast. For the main part, we present the stories according to their order of publication. The one exception is that we begin with “Kishmish,” which was written much later. This short, semiautobiographical story serves as a perfect introduction to many of the main themes of Other Worlds.

This is the first time that Teffi’s more “otherworldly” stories have been brought together in this manner. Our hope is that this will allow readers a clearer sense of the depth of understanding beneath her dazzling wit and brilliance.

*

Teffi was well aware of how often her work was misunderstood. Her preface to The Lifeless Beast begins:

I do not like prefaces …

I would not be writing a preface now were it not for a sad incident.

In October 1914 I published the story “Yavdokha.” This melancholy and painful story is about a lonely old peasant woman. She is illiterate and muddle-headed and so hopelessly benighted that, when she receives news of the death of her son, she is unable to grasp what has happened. Instead, she wonders whether or not he will be sending her money.

One angry newspaper then … indignantly scolded me for laughing at human grief.

“What does Madame Teffi find funny about this?” the newspaper asked indignantly. After quoting the very saddest passages of all, it repeated, “And does she consider this funny? And is this funny, too?”

The newspaper would probably be most surprised if I were to tell it that I did not laugh for a single minute …

And so the aim of this preface is to warn the reader that there is a great deal in this book that is not funny.

Several of the stories in The Lifeless Beast seem startlingly modern. The journalist’s misunderstanding shows us how far beyond the conventions of her time Teffi had moved. Yavdokha has no companion but a hog and is hunchbacked from living in a hut that has sunk deep into the ground. She lives five miles from the nearest village and is alienated both from the other peasants and from everything to do with the Russian state. After someone has read out a letter informing her of her son’s death she repeats the word “war”—but it is unclear if she even grasps what the word means and she certainly does not take in that her son has died. Yavdokha could have stepped out of one of Samuel Beckett’s last plays.

Curiously, misunderstandings not unlike the journalist’s are a central theme of The Lifeless Beast. In some stories, the misunderstandings arise from differences of social class; in others, it is the young and healthy who fail to understand the old and needy; in still others it is adults who fail—or do not even try—to understand children. Teffi’s portrayal of human failings is unflinching; in “Happiness,” she describes happiness as an “empty and hungry” creature that can survive only if fed with the “warm, human meat” of someone else’s envy. In a smaller number of stories, however, she evokes moments of genuine love and compassion. In “Daisy,” a seemingly inane aristocratic lady enrolls as a military nurse because that is the fashionable thing to do, quickly becomes involved in her work, and, to her surprise, is deeply moved by the gratitude of an uneducated soldier she helps to treat. “The Heart” follows a similar pattern; Rakhatova, a frivolous actress, thinks it would be entertaining to confess to a simple, poorly educated monk before receiving Communion in a remote monastery. She is taken aback by the monk’s spontaneous joy when she says she has not “committed any grave sins.”

The eyes now looking at her were so clear and joyful that they seemed to be flickering, just as stars flicker when their clear light overflows …

“Praise the Lord! Praise the Lord!”

He was trembling all over. It was as if he were a large severed heart and a drop of living water had fallen onto it. The heart quivers—and then all the other dead, severed pieces quiver too.

As always, Teffi’s imagery is carefully developed. The last sentence refers back to the scene that greeted Rakhatova and her friends when they arrived at the monastery the previous day:

The peasant was hacking at the fish with a broad knife …

Then the peasant took a bucket and poured water over the pieces of fish and the severed head. There was a sudden movement in one of the middle pieces. A twitch, a quiver—and the whole fish responded. Even the chopped-off tail jerked.

“That’s its heart contracting,” said the Medico.

Born in 1872, Teffi was a contemporary of Alexander Blok and other leading Russian Symbolists. Her own poetry is derivative, but in her prose she shows a remarkable gift for grounding Symbolist themes and imagery in the everyday world. “The Heart” is entirely realistic and at times even gossipy—yet the story is permeated throughout with Christian symbolism relating to fish. In “A Quiet Backwater,” she achieves a still more successful synthesis of the heavenly and the earthly. Toward the end of this seven-page story a laundress gives a long disquisition on the name days of various birds, insects, and animals. The mare, the bee, the glowworm—she tells a young visitor—all have their name days. And so does the earth herself: “And the Feast of the Holy Ghost is the name day of the earth herself. On this day, no one dairnst disturb the earth. No diggin, or sowin—not even flower pickin, or owt. No buryin t’ dead. Great sin it is, to upset the earth on ’er name day. Aye, even beasts understand. On that day, they dairnst lay a claw, nor a hoof, nor a paw on the earth. Great sin, yer see.” In a key poem—almost a manifesto—of French Symbolism, Charles Baudelaire interprets the whole world as a web of mystical “correspondences.” In a less grandiose way, Teffi conveys a similar vision. She was, I imagine, delighted by the paradox of the earth’s name day being the Feast of the Holy Spirit—not, as one might expect, the feast of a saint associated with some activity like plowing.

The Lifeless Beast is notable for its striking imagery and bold rendition of peasant speech, and for being one of a very few treatments in Russian literature of World War I as experienced by civilians. Teffi’s insight into human selfishness and viciousness never wavers. Nevertheless, she remains true to her faith in Christian love—as practiced by Daisy in a field hospital, as experienced by Rakhatova through Orthodox ritual, and as embodied in the generous, restorative understandings of folk religion.

*

In early 1920 Teffi settled in Paris. Russian émigrés throughout the world were quick to set up publishing houses and Teffi was one of their most valued authors. In 1921 alone she published five books: two miniature selections of articles and stories, in Berlin; a collection of comic sketches, in Shanghai; the short story collection Black Iris, in Stockholm; and A Quiet Backwater—which includes most of the stories from The Lifeless Beast—in Paris.

Teffi’s high standing is still more clearly shown by her publications in periodicals. “Ke fer?” (Que Faire?)—a brilliant evocation of the Russians’ sense of alienation in Paris—was published in April 1920, in the first issue of the important The Latest News. And “Solovki”—an almost Brueghelesque account of the widespread practice of mass pilgrimage to holy sites—was the first item in the first issue (August 1921) of the glamorous, lavishly illustrated journal The Firebird, which featured work by almost all the best-known émigré writers and artists. These two publications serve as markers to the twin paths Teffi would follow for the next fifty years. Many of her stories are about the mishaps and absurdities of émigré life; others are about a long-lost past.

“Solovki” was republished in Evening Day. Teffi’s following collection, A Small Town (Paris, 1927), is not represented in Other Worlds, since most of the stories deal with her émigré present—the “small town” of Russian Paris—rather than her Russian past. We have, however, included three stories from The Book of June. Like “Solovki,” the title story is a sympathetic account of overwhelming religious experience. Here, however, Teffi enters more deeply into the heroine’s inner world, into her most inarticulate thoughts and feelings; it is one of Teffi’s most sensitive treatments of adolescence.

*

Most of the stories in Witch bear the titles of folkloric beings—for example, “Wonder Worker,” “The House Spirit,” or “Rusalka” (a female water spirit resembling the Lorelei). Some of the stories are grim, some fanciful, some sober and philosophical. Some are realistic, with only the merest hint at the supernatural; in others, the supernatural motifs are more pronounced. Sometimes a character tries all too transparently to cover up his or her misconduct through some implausible supernatural explanation; sometimes it is the rationalist skeptics who appear foolish and blinkered. One piece, “About the House,” is hardly a story at all—more like a chatty retelling of a scholarly article, with a brief anecdote tacked on at the end.

All the stories are presented from the perspective of a Russian exile. Often the tone is nostalgic. Sometimes there is a note of bewilderment: Could such things truly have happened? Could such a world as old Russia really have existed?

Witch is a coherent and self-contained collection. Its main themes, however, are anticipated in “Wild Evening” and “Shapeshifter,” the last two stories in The Book of June. The central character of these two stories—and also of the first and last stories of Witch—is clearly modeled on Teffi herself. In 1892, at age twenty, Teffi married a lawyer by the name of Vladislav Buchinsky. We know little about her years as a young wife and mother, living in small provincial towns, but we know from statements Teffi made later that she was deeply unhappy.

“Wild Evening” is about fear of the unknown; except for an opportunistic peddler, everyone in the story—the young Teffi, the monks, even the horse—is in a state of terror. All around lurk threatening forces—darkness, cattle plague, the unclean dead. “Shapeshifter” may represent Teffi’s fantasy of a different course her life might have followed; a stranger’s chance intervention prompts the Teffi figure to decide against marriage to a lawyer who has much in common with the real-life Buchinsky. The opening, title story of Witch shows us a young husband and wife feeling more and more exasperated with each other as they grow ever more afraid—though neither will admit it—of a maid suspected of witchcraft. And in “Wolf Night,” the concluding story of Witch, we glimpse this same husband and wife perhaps a year or two later. The husband has grown even more resentful and evil-tempered, and the wife—now pregnant—is overwhelmed by nightmares of the house being surrounded by wolves. Ten lines before the end of the story, the husband says to the wife, “Please! Do me a favor! Go and stay with your oh so clever mother. A fine way she must have brought you up, to make you into such a hysteric.”

Teffi did not ever go back to her “oh so clever mother,” though it is possible that her husband may have uttered some sarcasm similar to the above. All we know for sure is that in 1898, probably on the edge of a breakdown, Teffi abandoned her husband and three children and moved back to Saint Petersburg to begin her career as a professional writer. There is little doubt that this rupture—which she very seldom spoke about—was a source of almost unbearable guilt and pain. Nevertheless, the words she wrote nearly fifty years later to her eldest daughter have the ring of truth. After saying she had been a bad mother, Teffi backtracks: “In essence I was good, but circumstances drove me from home, where, had I remained, I would have perished.”

At the heart of Witch, framed by these stories drawing on her unhappy life as a young woman, stands a group of six stories in which Teffi moves further back in time, to her own childhood. At one level, these can be read as a fictional treatment of folk beliefs in Volhynia (now part of western Ukraine). At the same time, they constitute a memorial to Teffi’s younger sister Lena, the closest to her of her six siblings. Lena had died in 1919, and Teffi writes movingly about her death in Memories, which she completed only shortly before the stories in Witch. In both books, Teffi portrays herself and Lena as inseparable.

One of these stories, “The Kind That Walk,” is a study of anti-Semitism—and of xenophobia more generally. Teffi deftly shows us people’s blind fear of Moshka, an honest and competent Jewish carpenter; she is equally deft in evoking the fascination with which she and Lena listen to the adults’ wild talk about how Moshka, many years earlier, had been dragged off by the devil. Many of the other main characters in these six stories are domestic servants. Teffi’s mother and some of her elder siblings appear now and then, but it is the children’s Nyanya, or nanny, who is the most important authority figure.

There are also two stories set mainly in Moscow and Petersburg. The longer of these, “The Dog,” begins with the narrator, Lyalya, recalling idyllically happy summers as a teenager on a country estate in the company of friends and admirers. In those days, she says with pained emphasis, she was carefree and high-spirited. She had felt briefly troubled, however, by the intense feeling with which a shy young boy called Tolya once swore eternal devotion to her, promising always to remain her “faithful dog.” A few years later, Lyalya falls in with the bohemian crowd who frequent the Stray Dog, the famous Saint Petersburg cabaret where all the major poets of the time used to give readings. Somehow, almost inadvertently, Lyalya takes up with Harry Edvers, a particularly odious pseudo-poet who later ends up working for the Cheka, the Bolshevik security police. In the story’s final scene she calls on her “faithful dog” for help—with dramatic results. Lyalya concludes:

That’s the whole story; that’s what I wanted to tell you. I’ve made nothing up; I’ve added nothing; and there’s nothing I can explain—or even want to explain. But when I turn back and consider the past, I can see everything clearly. I can see each separate event and the axis or thread upon which a certain force had strung them.

It had strung the events on the thread like beads and tied up the loose ends.

“The Dog” is convincing on every level. As an evocation of a lost childhood paradise, the first pages bear comparison with the work of Teffi’s friend and colleague Ivan Bunin. As a reckoning with the febrile cultural world of prerevolutionary Saint Petersburg, it anticipates Anna Akhmatova’s Poem without a Hero (written 1940–1965). Like Akhmatova, Teffi sees the bohemian abandonment of traditional moral values as having paved the way for the brutalities and duplicities of Communism. And the denouement provides a fine example of a writer drawing on the occult not for exotic ornament but as a source of psychological truth. The huge dog’s sudden appearance may be mere chance; it may be a real embodiment of Tolya’s loyal and resolute spirit; or it may be Tolya’s spirit prompting Lyalya toward an act that requires superhuman powers. Teffi has taken care not to exclude any of these possibilities. Unlike the “certain force” spoken of by her narrator, she does not tie up the story’s loose ends.

*

In the letter quoted earlier, Teffi says of Witch, “This book has been highly praised by Bunin, Kuprin, and Merezhkovsky. They praised it for its artistry and the excellence of its language. I am, by the way, proud of my language, which critics have seldom commented on.”

Teffi’s pride is justified. Along with Andrey Bely, Ivan Bunin, Vladimir Nabokov, and Andrey Platonov, she is one of a number of great twentieth-century Russian prose writers who were also poets but whose poetic gifts found their truest expression in prose. It is difficult, though, to define what makes Teffi’s language so remarkable. She makes skillful use of repetition, often using a single word as a leitmotif for an entire story. In “Wild Evening,” for example, she uses the adjective dikii (wild) of a horse’s eye, of the night, of a person, and of the dangerously high seat of a two-wheel carriage. In “Rusalka” she repeats mutnyi (murky, cloudy, troubled) more and more often in the course of the story; she uses the word especially often in relation to the two sisters’ troubled visions in the last pages, when one of the housemaids either drowns or turns into a rusalka and the girls fall ill with scarlet fever. It is also true that Teffi has a fine ear for the linguistic peculiarities of people from different social groups—ranging from Volhynia peasants to Russian émigrés in Paris; it is not for nothing that the satirist Mikhail Zoshchenko, as a novice writer, noted down some of Teffi’s most striking coinages and malapropisms. Nevertheless, the twenties was a rich period for Russian prose and none of the above is enough to make Teffi unique.

What truly sets her apart is her lightness of touch. More than Vladislav Khodasevich, more than Akhmatova or any of the Acmeist poets, it is Teffi who has inherited the grace and fluency of Pushkin. She can write as simply and tautly as Hemingway—but without the least sense of willed tightness. She can write long, complex sentences dense with embedded participial clauses, yet these sentences, unlike apparently similar sentences in the work of Bunin, retain a conversational quality. Some of her more unreliable narrators come out with phrases as memorably absurd as characters out of Zoshchenko—yet even here there is a difference. Zoshchenko’s sentences seem brilliantly constructed; Teffi’s appear simply to have happened. It may be for this very reason—her success in creating an illusion of naturalness—that Teffi’s language has received so little scholarly attention.

Many of her greatest contemporaries, however, were well aware of her gifts. Zoshchenko studied her intently; Bunin admired her; Mikhail Bulgakov borrowed from her Civil War articles for The White Guard. And Georgy Ivanov referred to Teffi as “a unique phenomenon in Russian literature, a true miracle that people will still be wondering at in a hundred years’ time, crying and laughing at once.”

*

The last two pieces in this collection are “Baba Yaga” and “Volya,” two essays from Earthly Rainbow (published six months before Teffi’s death), in which Teffi asserts her profound Russianness. Baba Yaga is the name of the archetypal Russian folktale witch and the word volya is used for what Teffi understands as a peculiarly Russian kind of unbounded emotional freedom. Both essays end with a heartfelt cry. Baba Yaga, confined in her wintry hut, longing for wildness, freedom, and open spaces, cries, “B—o—r—i—n—g.” And in the last lines of “Volya” the aging Teffi remembers herself as a young woman, waving at the spring dawn and crying out, “Vo-o-o-ly-a-a-a!” Shortly before this, she has heard a boy on the other side of the river singing his heart out. The last line of his song—“Sing Volya, Volya, Volya!”—is described as “heartrending, piercingly joyful, like a sudden yelp, coming from somewhere too deep in the soul.”

Teffi is indeed one of the most graceful of Russian writers. It seems likely, however, that this grace is a way of managing an almost unbearable burden of pain. There are a great many heartfelt cries in these stories. Some of these cries and desperate screams seem almost infectious, so agonizing that those who hear them can’t help but let out similar screams. The epileptic sleigh driver in “Shapeshifter,” for example, lets out a cry with “something so terrible about it” that the narrator screams, too, jumping up from her seat and almost tumbling out of the sleigh. And the narrator of “Witch” describes, at some length, the scream of a guinea hen “wailing for her slaughtered mate.” She continues:

This isn’t easy to explain to you, but such a cry of inconsolable despair, above the dead little town, in the silence of that trackless steppe, was more than any human soul could bear.

I remember coming home and saying to my husband, “Now I know why people hang themselves.”

He screamed, clutching his head in his hands.

In the last pages of “The Book of June,” Katya lets out repeated screams of terror: “Katya had no idea what made her keep on screaming like this. Some kind of lump seemed to be filling her throat, making her gasp and wheeze and scream out Grisha’s name.” And two of Teffi’s very finest works end with still wilder cries. The heroine of “Solovki” gives herself up to a prolonged scream during a service in the main monastery church: “What mattered was not to stop, to expend more and more of herself in the cry, to give herself to it more intensely, yes, more and more of herself: Oh, if only they didn’t get in her way. Oh, if only they let her keep going … But it was so hard. Would she have the strength?”

One of the most painful passages in all Teffi’s work is the last page of her autobiographical Memories, her account of her final, irrevocable departure from Russia. It is the summer of 1919 and she is on her way to Istanbul, on a boat leaving Novorossiysk harbor:

From the lower deck comes the sound of long, obstinate wails, interspersed with words of lament.

Where have I heard such wails before? Yes. I remember. During the first year of the war. A gray-haired old woman was being taken down the street in a horse-drawn cab. Her hat had slipped back onto the nape of her neck. Her yellow cheeks were thin and drawn. Her toothless black mouth was hanging open, crying out in a long tearless wail: “A-a-a-a-a!” Probably embarrassed by the disgraceful behavior of his passenger, the driver was urging his poor horse forward, whipping her on.

Yes, my good man, you didn’t think enough about whom you were picking up in your cab. And now you’re stuck with this old woman. A terrible, black, tearless wail. A last wail. Over all of Russia, the whole of Russia … No stopping now …

These cries and wails differ in tone. The boy’s “sudden yelp” in “Volya” is “piercingly joyful,” whereas the gray-haired woman in Memories is mired in despair. In at least one respect, however, the cries are all too similar. All are painfully raw; all come from “somewhere too deep in the soul.” It is as if these characters have been flayed. Layers of protective skin have been torn away and what should be hidden lies dangerously exposed.

Teffi’s grace seems all the more precious when we understand that it was both a protective cloak and her way of trying to keep her footing. It may perhaps have been what enabled her, unlike many of her contemporaries, to preserve her balance and sanity throughout a seemingly never-ending series of catastrophes—World War I, the Russian Civil War, the viciousness of émigré political infighting, and life under German occupation during World War II. If Teffi liked to refer to herself as a witch, if she identified at the end of her life with Baba Yaga, this may be because she was hoping to charm the inner and outer darkness, to cast a spell on it that might keep it at bay.

Robert Chandler’s translations from Russian include Alexander Pushkin’s The Captain’s Daughter; Nikolai Leskov’s Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk; Vasily Grossman’s An Armenian Sketchbook, Everything Flows, Stalingrad, Life and Fate, and The Road; and Hamid Ismailov’s The Railway. His cotranslations of Andrey Platonov have won prizes both in the UK and in the U.S. As well as running regular translation workshops in London and teaching in an annual literary translation summer school, he works as a mentor for the British Centre for Literary Translation.

Excerpted from the foreword to Other Worlds: Peasants, Pilgrims, Spirits, Saints , by Teffi, edited and with a foreword by Robert Chandler, translated by Chandler and several others, including Anne-Marie Jackson, Sabrina Jaszi, Sara Jolly, Nicolas Pasternak Slater, and Sian Valvis, published by NYRB Classics. Foreword copyright © 2021 by Robert Chandler.

April 21, 2021

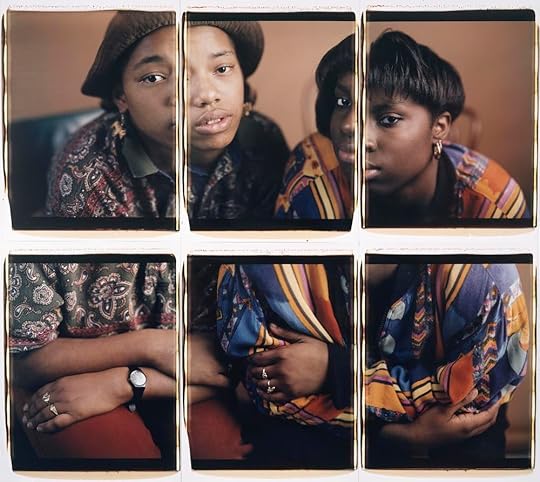

Every Day Was Saturday in Harlem

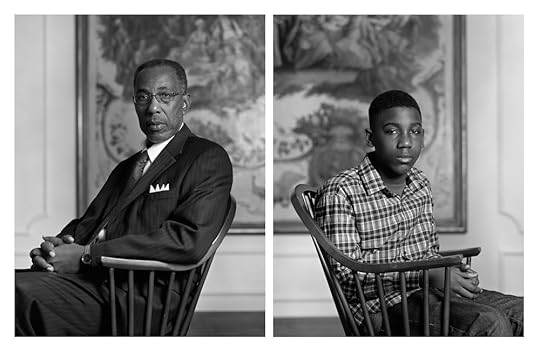

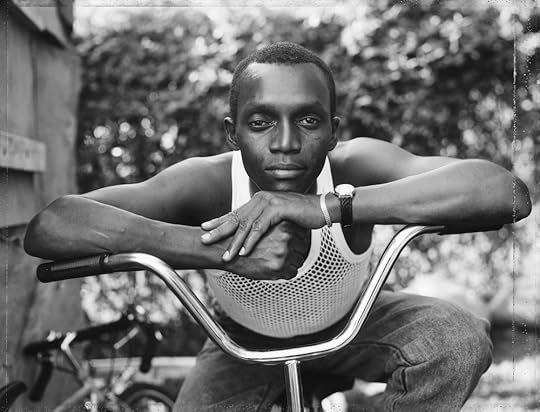

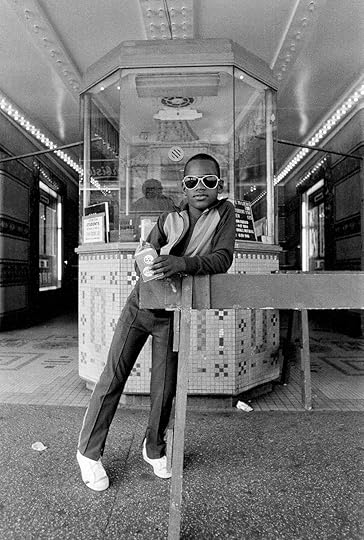

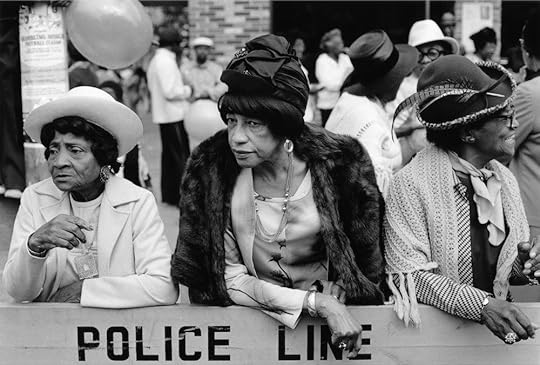

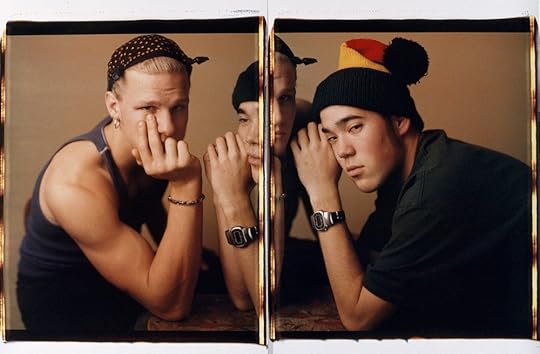

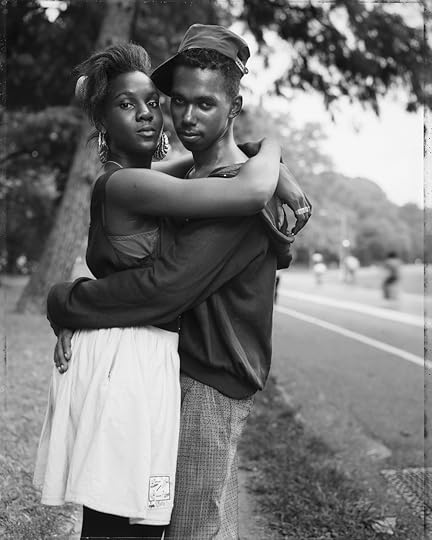

As a child, the Queens-born photographer Dawoud Bey marveled at the vibrancy of midcentury Harlem, where his parents had met and many of their friends and family members still lived. “Driving through the crowded streets, I was amazed by what appeared to be the many people on vacation,” he has written. “It seemed to me that no matter what the day, everyday was Saturday in Harlem.” In 1975, equipped with a camera, he began paying weekly visits to the neighborhood, walking the streets and capturing pictures. This approach—on the ground, studied, empathetic—led to his first series of photographs, “Harlem, USA,” and would inform his practice in the ensuing decades of his career; much of his work feels grounded in the unmediated intimacy of these early street portraits. Bey’s Harlem photographs and a bounty of other pieces from his near half century at work are on display in “An American Project” (up at the Whitney Museum of American Art through October 3), his first retrospective in twenty-five years. A selection of images from the show appears below.

Dawoud Bey, Martina and Rhonda, 1993, six dye diffusion transfer prints (Polaroid), overall: 48 × 60″. Whitney Museum of American Art, gift of Eric Ceputis and David W. Williams. © Dawoud Bey.

Dawoud Bey, Don Sledge and Moses Austin, from The Birmingham Project, 2012, pigmented inkjet prints, each: 40 x 32″; framed, each: 41 1/8 x 33 1/8 x 2″. Rennie Collection, Vancouver. © Dawoud Bey.

Dawoud Bey, A Woman at Fulton Street and Washington Avenue, Brooklyn, NY, 1988, inkjet print, 40 x 30″. © Dawoud Bey and courtesy of the artist, Sean Kelly Gallery, Stephen Daiter Gallery, and Rena Bransten Gallery.

Dawoud Bey, Two Girls from a Marching Band, 1990, pigmented inkjet print (printed 2019), 30 x 40″; frame: 41 1/8 x 50 1/8 x 2 1/8″. Collection of the artist. Courtesy Sean Kelly Gallery, New York; Stephen Daiter Gallery, Chicago; and Rena Bransten Gallery, San Francisco. © Dawoud Bey.

Dawoud Bey, A Young Man Resting on an Exercise Bike, Amityville, NY, 1988, inkjet print, 30 x 40″. © Dawoud Bey and courtesy of the artist, Sean Kelly Gallery, Stephen Daiter Gallery, and Rena Bransten Gallery.

Dawoud Bey, A Boy in Front of the Loew’s 125th Street Movie Theater, 1976, gelatin silver print (printed 2019), 14 x 11″; frame: 20 5/8 x 16 5/8 x 1 1/2″. Collection of the artist. Courtesy Sean Kelly Gallery, New York; Stephen Daiter Gallery, Chicago; and Rena Bransten Gallery, San Francisco. © Dawoud Bey.

Dawoud Bey, Three Women at a Parade, Harlem, NY, 1978, gelatin silver print, 11 x 14″. © Dawoud Bey. Collection of the artist. Courtesy Sean Kelly Gallery, New York; Stephen Daiter Gallery, Chicago; and Rena Bransten Gallery, San Francisco.

Dawoud Bey, Hilary and Taro, 1992, two dye diffusion transfer prints (Polaroids), overall: 30 1/8 × 44″; frame: 33 3/4 × 47 1/2 × 1 3/4″. Whitney Museum of American Art, Purchase, with funds from the Photography Committee.

Dawoud Bey, Untitled #20 (Farmhouse and Picket Fence I), 2017, gelatin silver print, 44 x 55″. Collection of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; Accessions Committee Fund purchase. © Dawoud Bey.

Dawoud Bey, A Couple in Prospect Park, Brooklyn, NY, 1990, inkjet print, 40 x 30″. © Dawoud Bey and courtesy of the artist, Sean Kelly Gallery, Stephen Daiter Gallery, and Rena Bransten Gallery.

“An American Project” will be on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art through October 3.

April 20, 2021

Redux: Spreading Privacies on the Internet

Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

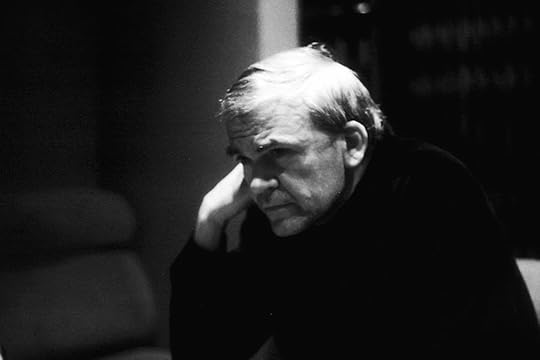

Milan Kundera, ca. 1980. Photo: Elisa Cabot.

This week at The Paris Review, we’re spending too much time online. Read on for Milan Kundera’s Art of Fiction interview, Hiromi Kawakami’s short story “Mogera Wogura,” and Stephen Dunn’s poem “Historically Speaking.”

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, and poems, why not subscribe to The Paris Review? You’ll also get four new issues of the quarterly delivered straight to your door. Or, subscribe to our new bundle and receive Poets at Work for 25% off.

Milan Kundera, The Art of Fiction No. 81

Issue no. 92 (Summer 1984)

Today one can compose music with a computer, but the computer always existed in composers’ heads—if they had to, composers could write sonatas without a single original idea, just by “cybernetically” expanding on the rules of composition. Janáček’s purpose was to destroy this computer … My purpose is like Janáček’s: to rid the novel of the automatism of novelistic technique, of novelistic word-spinning.

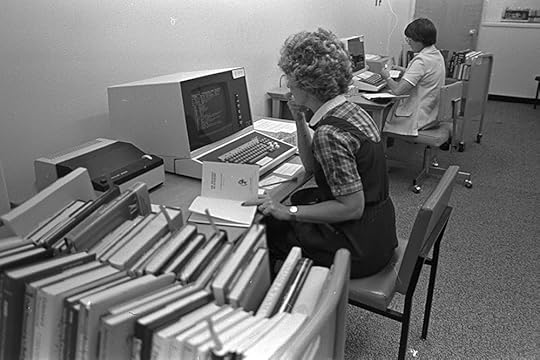

Photo: University of Texas at Arlington Photograph Collection. CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...), via Wikimedia Commons.

Mogera Wogura

By Hiromi Kawakami, translated by Michael Emmerich

Issue no. 173 (Spring 2005)

The young humans who have joined the company in recent years don’t even seem to notice how different I look. I don’t think they consciously decide not to wonder about me, why my form is so unlike theirs; they simply can’t be bothered. People sometimes make comments—“You’re pretty hairy, aren’t you?”—but no one openly stares at me anymore, or presses me for information about my background. Until a decade or so ago, people really gossiped a lot.

I sit at my computer until lunchtime, mostly dealing with statistics. Sometimes a young woman comes from general affairs and asks me to write out an address on an envelope in calligraphy, using a brush. I’m a good calligrapher. Everyone says I write sharper-looking characters than anyone else in the company.

Photo: Ellinor Algin. CC BY 4.0, (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...), via Wikimedia Commons.

Historically Speaking

By Stephen Dunn

Issue no. 219 (Winter 2016)

It was a year of pirates in speedboats,

anonymous bullies spreading privacies

on the Internet, and the worst of them

doing worse than that and wishing to be known

for what they’d done, their perfidy

an advertisement for a cause.

Thus it was a bad year for historians,

whose stories couldn’t be correct

for longer than a few days. More than ever

the imperfections of memory

would combine with the slipperiness

of documentation to produce versions

only people who need not be persuaded

could agree with …

If you enjoyed the above, don’t forget to subscribe! In addition to four print issues per year, you’ll also receive complete digital access to our sixty-eight years’ worth of archives. Or, subscribe to our new bundle and receive Poets at Work for 25% off.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers