The Paris Review's Blog, page 113

May 27, 2021

New York’s Hyphenated History

In Pardis Mahdavi’s new book Hyphen , she explores the way hyphenation became not only a copyediting quirk but a complex issue of identity, assimilation, and xenophobia amid anti-immigration movements at the turn of the twentieth century. In the excerpt below, Mahdavi gives the little-known history of New York’s hyphenation debate.

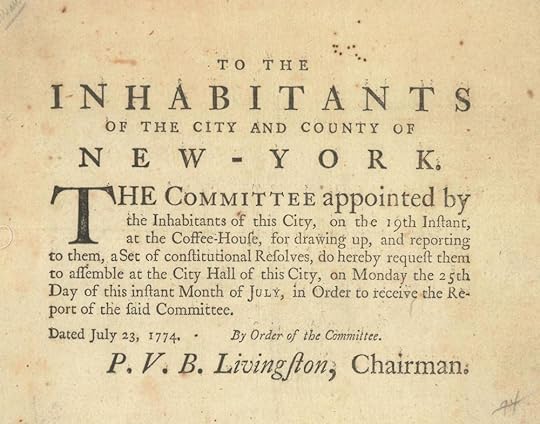

Flyer for the New-York hyphen debate, 1774 copyright © New-York Historical Society

In the midst of an unusually hot New York City spring in 1945, Chief Magistrate Henry H. Curran was riding the metro downtown to a meeting at City Hall. Curran, the former commissioner of immigration at the Port of New York, and former president of the Association Against the Prohibition Amendment, had forgotten to bring his copy of the paper that morning. As a result, he found himself reading the various ads surrounding him on the colorful New York City subway.

Curran tried to focus on different advertisements to distract himself from the heat, and from his growing restlessness. Until, that is, one particular ad seized his attention. It was an ad for the “New-York Historical Society.” Innocuous enough at first, it was the tiny piece of orthography that caught Curran’s eye and sent a wave of heat through his body. Was that—could that be a hyphen? Sitting unabashedly between the words New and York? The anti-hyphenate politician was furious.

Curran swiftly exited the subway, marched into City Hall, and got his friend Newbold Morris, president of the New York City Council, on the phone. Later that week, the New York World–Telegram—oh, the irony of the hyphen placement in the publication that reported the incident—documented the conversation between Morris and Curran.

“This thing—this hyphen—is like a gremlin which sneaks around in the dark … you should call a special meeting of City Council immediately and have a surgical operation on it! We won’t be hyphenated by anyone!” Curran reportedly said to Morris.

What Curran either didn’t know, or wanted to erase, was the fact that up until the late 1890s, cities like “New-York” and “New-Jersey” were usually hyphenated to be consistent with other phrases that had both a noun and an adjective. In 1804, when the “New-York Historical Society” was founded, therefore, hyphenation was de rigueur. The practice of hyphenating New York was adhered to in books and newspapers, and adopted by other states. Even the New York Times featured a masthead written as The New–York Times until the late 1890s.

It was only when the pejorative phrasing of “hyphenated Americans” came into vogue in the 1890s, emboldened by Roosevelt’s anti-hyphen speech, that the pressure for the hyphen’s erasure came to pass.

Curran was no exception to the wave of anti-immigrant xenophobia sweeping the nation at the time of Roosevelt’s speech and in the lead-up to World Wars I and II. During his time as commissioner of immigration, he penned a famous article that appeared in the recently unhyphenated New York Times entitled, “The Commissioner of Immigration Shows How He Is Hampered.” The essay was Curran’s response to outrage over the deportation of an immigrant mother who had arrived at Ellis Island with her young children, only to be sent back “home” while her children were to remain in the U.S. In the piece, Curran called for the public to afford the judges of such decisions “sympathy more than censure.”

Writing in 1924, several years after Roosevelt’s speech, Curran accused New York society of being overly judgmental, noting that “it is Ellis Island that catches the devil whenever a decision comes along that does not suit somebody. Of course, we are now in the midst of the open season for attacks on Ellis Island. We have usurped the place of the sea serpent and hay fever. We are ready to be roasted.” For the next twelve years he served as commissioner of immigration, Curran became more staunchly anti-immigrant, and his hatred was fueled by the anti–hyphenated Americanism espoused by people like Roosevelt and, later, Woodrow Wilson.

Curran was outraged that his beloved city would appear hyphenated, and he continually insisted that Morris call a meeting to pass a law that barred the use of a hyphen in New York. Meanwhile, curators, historians, and librarians banded together with antidiscrimination and immigrants’ rights defenders to defend a hyphenated New-York. Curran could not win this time, they insisted. The curators and librarians at the Historical Society bravely stood by the hyphen in their name, confirming that they had been founded in 1804, that the hyphen was in the original configuration of New-York, and that, no, this hyphen would not be erased. Hyphenated Americans and activists throughout New York City worried that this erasure would signal that they would not be welcome in the one city that was supposed to be a bastion of openness in America.

In the days leading up to the meeting, head librarian Dorothy Barch proclaimed that despite all of their research, no one had found any documentation indicating that the hyphen in New-York had ever been officially deleted by the government or any lawmaking body in the city, state, or country. The day before the meeting, curator Donald A. Shelley declared that they couldn’t even change their name if they wanted to because it is “chiseled in stone on the front of our building.”

The press and the pressure to enact an anti-hyphenation law were mounting in the lead-up to the meeting. Curran insisted that the hyphen was a scourge and that it should be erased completely, as it threatened to divide American society. In erasing the hyphen, Curran wanted to delete hyphenated Americanism altogether. He was firm: the hyphen divides, and as a divider, it threatened the future of the city, the state, the country. As he had done in his role as commissioner of immigration, he felt strongly that any immigrant or child of immigrants who identified as anything other than an American should be returned to whatever country was on the other side of that “filthy hyphen.” As such, he was emphatic in his attempt to whip the votes of his fellow council members in the lead up to the meeting.

All of this activity garnered a range of emotional reactions. Some people felt that this anger and energy, coming amid World War II, was misplaced. The upcoming meeting became the subject of mockery for artists and social commentators alike. At the meeting, a group of musicians and composers performed a song they had written entitled “The Hyphen-Song.” The words, written by popular songwriter Leonard Whitcup, included:

Take a boy like me, dear

Take the girl I’m dreaming of—

Add a hyphen, what’ve you got?

You got–UM–M–you’ve got love!

Me without you–you without me

It’s a sad affair—

But take a tip from the hyphen—

And baby we’ll get somewhere

The musicians performed to great acclaim. Activists gathered outside, tying ribbons to the stone etching of the hyphen to highlight the need to protect the orthographic mark that suddenly had so many political and social reverberations.

In the end, much to his chagrin, Curran lost this contest. No law was ever passed outlawing the hyphen, and it remains to this day, etched in stone on the building of the New-York Historical Society, a homage to the journey of the city and the hyphenated individuals who fought the good fight to keep the hyphen—and its many meanings—alive.

Today, the New-York Historical Society hosts hyphen festivals and blogs, and their softball team is named the Hyphens. Henry Curran died in 1966 at the age of eighty-eight. Before his death, and after his hyphen assassination attempt, he went on to be LaGuardia’s deputy mayor and the borough president of Manhattan. He died at Saint Barnabas Hospital in New-York.

Pardis Mahdavi is dean of social sciences in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences and a professor in the School of Social Transformation at Arizona State University. She is a nonfiction writer with twenty years of experience as an anthropologist, a public health researcher, and an expert in sexual politics across the globe. She is the author of Hyphen, as well as five other books, including the first book on sexual politics of modern Iran, Passionate Uprisings: Iran’s Sexual Revolution. A former journalist turned academic, she has written for Ms. Magazine, Foreign Affairs, The Conversation, The Huffington Post, Jaddaliyya, and The Los Angeles Times Magazine.

Extracted from Hyphen , by Pardis Mahdavi, which will be published in Bloomsbury’s Object Lessons series on June 3.

May 26, 2021

To Witness the End of Time

Podgrad pri Vranskem Castle, 1830. Kaiser, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Terry Pratchett’s 1988 summary of The House on the Borderland begins: “Man buys House. House attacked Nightly by Horrible Swine Things from Hole in Garden. Man Fights Back with Determination and Lack of Imagination of Political Proportions.” It ends: “The journey to the Central Suns sold me infinity.” Infinity is a rather lofty reward for persevering through a battle with pig-men. But Pratchett was right. William Hope Hodgson’s novel, published in 1908 (but likely written in 1904) is one of the most startling accounts of infinity that I’ve ever read.

The novel came to me serendipitously: my friend Mike stumbled across it while googling some Dungeons & Dragons thing called “Into the Borderlands.” He read the book, loved it, and passed it on to me. I read it with no knowledge of who Hodgson was or what I was getting into. As an immigrant, I often experience the delight of belated discovery: Frederick Douglass, Star Wars, Lolita. But with Hodgson, I’m not alone. After his death in Ypres at age forty-one, Hodgson was mostly forgotten until a brief—and apparently unsuccessful—revival in the thirties. When fiction reappears after a spell of obscurity, we often say it was before its time. To me, The House on the Borderland is untimely in another, more enthralling way: it undoes time. It begins conventionally enough. The narrator (a figure for the author) and his friend decide to take a fishing trip to “a tiny hamlet called Kraighten” in the west of Ireland—an unusual place for a vacation, but a classic frame for a Gothic tale all the same. One day, the two men go exploring. Tracking a strange spray of water shooting up above the canopy, they find themselves in a kind of jungly lowland with a pit in the middle of it. Jutting into this pit is a protruding rock, at the tip of which sits the ruins of an old house. In the rubble, they find a half-destroyed book—a diary. Smoking their pipes at camp that night, “Hodgson” reads it aloud.

The entries feel at first like a haunted-house story, with echoes of Edgar Allan Poe: a rambling old mansion bought by folks from out of town, a canine companion named Pepper who tugs at our heartstrings, intimations of a long-lost love, and a hero unaccountably drawn to investigate holes in the ground. But then the diarist recounts a strange vision of spinning out into the universe and descending upon an unearthly plain ringed with mountains, a black sun limned by a ring of fire hovering over it. In the middle of the amphitheater, he sees what appears to be a replica of the house in which he lives on Earth—this one, though, has an eerie, green glow. In the mountains above, he makes out the giant shapes of ancient gods—Kali, Set—and a hideous beast that moves “with a curious lope, going almost upright, after the manner of a man. It was quite unclothed, and had a remarkable luminous appearance. Yet it was the face that attracted and frightened me the most. It was the face of a swine.”

This creepy vision turns out to be prophetic. Soon the novel tells the strange tale of a battle between the diarist and a horde of these pig-men, of smaller size but fleshier and more horrific presence than the vision. Hodgson ingeniously weaves together the horror of Circe turning Odysseus’s men into pigs, the biblical overtones of demon-possessed swine, and the pig-human hybrids of H. G. Wells’s Island of Dr. Moreau. Indeed, the prose begins to resemble something out of Wells, as a science-minded explorer tries to discern the line between the unnatural and the supernatural. The narrator’s experiments are exaggeratedly methodical, which of course makes us skeptical of him. When the horde vanishes without a trace, his sister seems afraid of him and makes no mention of the pig-men. Later, he measures a subterranean pit in the cellars of the house by placing candles around its perimeter: “Although they showed me nothing that I wanted to see; yet the contrast they afforded to the heavy darkness, pleased me, curiously. It was as though fifteen tiny stars shone through the subterranean night.” His efforts to map space seem futile or, rather, aesthetic. There’s a tinge of the sublime horror of weird architecture and eldritch space to all of this. In effect, this metaphor, which likens the abyssal candelabra to stars, converts an obsession with space into an obsession with time.

The narrator is reading (“curiously enough”) the Bible when he has another vision. It begins with a sound: “A faint and distant, whirring buzz, that grew rapidly into a far, muffled screaming. It reminded me, in a queer, gigantic way, of the noise that a clock makes, when the catch is released, and it is allowed to run down.” But the clock in the study is in fact speeding up, the minute hand “moving ’round the dial, faster than an ordinary second-hand,” the hour hand moving “quickly from space to space.” The narrator looks out the window. What follows—a kind of ekphrasis of time-lapse film—is astonishing. While The Time Machine (1895) also describes time sped up, to my mind, Hodgson’s language and imagery far surpass Wells’s.

Surrounded by the “blur” of “world-noise,” the narrator watches the sun go from orb to arc to streak to flicker to quiver of light. He sees clouds “scampering” and “whisking” across the sky; the “stealthy, writhing creep of the shadows of the wind-stirred trees”; and when winter comes, “a sweat of snow” that abruptly comes and goes, “as though an invisible giant ‘flitted’ a white sheet off and on the earth.” He sees “a heavy, everlasting rolling, a vast, seamless sky of grey clouds—a cloud-sky that would have seemed motionless, through all the length of an ordinary earth-day.” He grows used to “the vision of the swiftly leaping sun, and nights that came and went like shadows.” The advancing edge of a black thundercloud flaps “like a monstrous black cloth in the heaven, twirling and undulating rapidly.” He catches “glimpses of a ghostly track of fire that swayed thin and darkly towards the sun-stream … it was the scarcely visible moon-stream.” Poor Pepper turns to dust. His own face has grown old in the looking glass. Eventually, he sees a long, rounded shape under the “aeon-carpet of sleeping dust” in the room—his corpse. It has been “years—and years.” He has become “a bodiless thing.”

At this point, the novel gets even weirder, merging spiritual and scientific language into a grand, universal theory of ghosts, angels, demons, heaven, hell, as well as planetary orbits and star deaths. Our ghostly narrator repeatedly hints that he has reached the end of time—yet time presses on. He drifts, without will, into unknown dimensions via large bubbles with human faces locked within them. Eventually, he watches as his house on the borderland—the borderland between what and what exactly?—is overrun with pig-men, set aflame as the Earth flies into the sun, and then rises again in the phosphorescent incarnation of the house from his first vision. He is borne toward it, steps inside, and wakes in his study. All is well, it was just a dream … except that poor Pepper is still a heap of dust.

The House on the Borderland closes with the vengeance and the patness of genre fiction. Pig-men, of a sort, return. The narrator gets another dog, who is also sacrificed to plot. H. P. Lovecraft (of all people) noted a touch of sentimentality to the novel, too. But I have never read a more remarkable account of time beyond a human scale. This account feels especially worth revisiting now, when time poses a new problem for humans: we’re running out of it. Or it’s running out of us—we are the grains of sand falling through the thin neck of years left before we reach three degrees too far.

How can we conceive of the time of climate change, the time of planetary death? The House on the Borderland tried to conceive of exactly this a century ago. Yes, the narrator’s acts are fruitless. He gets haplessly carted about the universe to witness the end of time, which never really ends, is always at the edge, nearing an asymptote, on the borderland. Sure, his diary breaks off midspeech and Hodgson slams the frame story shut with an unsatisfying clunk. Still, I urge you to dwell in The House on the Borderland, to explore both its means—its ragged form and otherworldly atmosphere—and its ends: the sublimity and humility of recognizing just how uneasily we sit within the endless spinning of time.

Namwali Serpell is a professor of English at Harvard University and the author of Seven Modes of Uncertainty (2014), The Old Drift: A Novel (2019), and Stranger Faces (2020).

Excerpted from B-Side Books: Essays on Forgotten Favorites, edited by John Plotz. Copyright © 2021 Columbia University Press. Used by arrangement with the publisher. All rights reserved. B-Sides—a celebration of great books that time forgot—is also a series at Public Books.

May 25, 2021

Redux: A Good Reading Night

Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

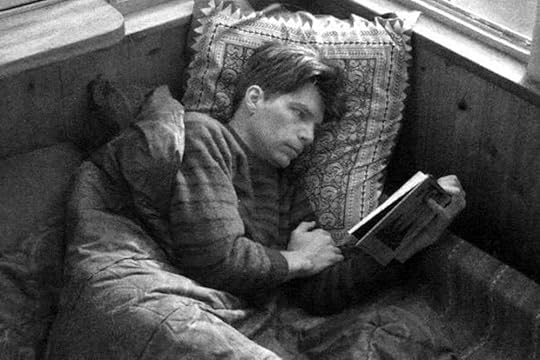

Richard Powers.

This week at The Paris Review, we’re counting the weekdays. Read on for Richard Powers’s Art of Fiction interview, Gish Jen’s short story “Amaryllis,” and Wayne Miller’s poem “Reading Sonnevi on a Tuesday Night.”

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, and poems, why not subscribe to The Paris Review? You’ll also get four new issues of the quarterly delivered straight to your door. Or, subscribe to our new bundle and receive Poets at Work for 25% off.

Richard Powers, The Art of Fiction No. 175

Issue no. 164 (Winter 2002–2003)

In the early eighties, I was living in the Fens in Boston right behind the Museum of Fine Arts. If you got there before noon on Saturdays, you could get into the museum for nothing. One weekend, they were having this exhibition of a German photographer I’d never heard of, who was August Sander. It was the first American retrospective of his work. I have a visceral memory of coming in the doorway, banking to the left, turning up, and seeing the first picture there. It was called Young Westerwald Farmers on Their Way to a Dance, 1914. I had this palpable sense of recognition, this feeling that I was walking into their gaze, and they’d been waiting seventy years for someone to return the gaze. I went up to the photograph and read the caption and had this instant realization that not only were they not on the way to the dance, but that somehow I had been reading about this moment for the last year and a half. Everything I read seemed to converge onto this act of looking, this birth of the twentieth century—the age of total war, the age of the apotheosis of the machine, the age of mechanical reproduction. That was a Saturday. On Monday I went in to my job and gave two weeks notice and started working on Three Farmers.

Amaryllis

By Gish Jen

Issue no. 179 (Winter 2006)

In the meanwhile there was Tara’s grandfather in Flushing to think about—Yah Yah, Tara called him.

“He’s going to want you to give him a bath,” she warned. “Just say no.”

“No baths,” promised Amaryllis.

“And he goes to get groceries in Manhattan Chinatown on Wednesdays. Don’t ask why, we’re just glad he still knows when it’s Wednesday. So if you go and don’t see him, that’s where he is.”

“How old is he?”

“How old is he. Ninety-one, we think, though he seems younger. He’s outlived both his kids. He’s more agile than I am. This doctor is always asking him what he eats.”

Reading Sonnevi on a Tuesday Night

By Wayne Miller

Issue no. 172 (Winter 2004)

A film of mist clings to the storm windows

as the thunder gets pocketed and carried away

in the rain’s dark overcoat. A good reading night—

car wheels amplified by the flooded street,

leaf-clogged gutters bailing steadily, constant

motion beyond my walls echoing

my body’s gyroscopic stillness. Sonnevi says

Only if I touch do I dare let myself be touched,

and that familiar and somewhat terrifying curtain

of reading slips around me …

If you enjoyed the above, don’t forget to subscribe! In addition to four print issues per year, you’ll also receive complete digital access to our sixty-eight years’ worth of archives. Or, subscribe to our new bundle and receive Poets at Work for 25% off.

Flower Moon

In her monthly column The Moon in Full, Nina MacLaughlin illuminates humanity’s long-standing lunar fascination. Each installment is published in advance of the full moon.

Gustav Klimt, Bauerngarten, 1907, oil on canvas, 43 1/4 x 43 1/4″. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

An afternoon at the end of May, I stood on a porch in another state, and the day went staticky and dark. The sky purpled and every blade of grass on the hill was pricked by the electricity in the air, a field of green antennae buzzing with the signal. The purple that took hold: not a soporific lavender but the threatening plum of storm, a night come sudden and gone wrong. Said someone on the porch whose third language was English, “It is an eclipse?” It was not, but it felt like one, or how I imagine one to feel, time getting bent by light, the boundary breaking between day and night, one bleeding into the other, destabilizing in the way that certain incomprehensibilities can be, when the messages the senses bring to the brain outpace the brain’s ability to make sense of them.

Sound went weird as well. In the pond at the bottom of the hill, the peeper frogs, which otherwise started their song at nightfall, were tricked by the sudden dark and began a berserk and feverish peepage. Each night these mud-colored squishers ballooned their throats in seductive celebration, engaged in the springtime pursuit of keeping their creaturehood around. Fertile vernal peeping fever. You could hear messages, words, rhythms in their high-pitched love songs. Peak peak peak. Complete complete complete. Seek seek seek. That afternoon, a thunderstorm moved through, the sun reappeared, and, like that, the frogs returned to their daytime silence.

They saw night where there was none, and made what meaning they could from it. We heard words where there were none, the same way we make a face on the full moon’s surface: a perceptual inclination called pareidolia, in which our minds impose patterns or meaning where they might not exist. You’ve glimpsed a turtle riding a motorcycle in a cloud? Seen a demon in the nubbled texture of your ceiling? Heard syllables sloshing from the dishwasher? Pareidolia. It used to be considered a symptom of psychosis. Now it’s known as just another route to making meaning. “Look at walls splashed with a number of stains,” advised Leonardo da Vinci. “You can see the resemblance to a number of landscapes … vicious battles … lively postures of strange figures.” We can see “monstrous things” and we’re better for it: “by indistinct things the mind is stimulated to new inventions.” We make sense where there is no sense, out of the half-seen and overheard, out of all the indistinct; the big truths don’t reveal themselves when we look at them directly. Tonight, the full moon is the closest it will be to earth all year, a big fat full supermoon. What will you see on its round white wall?

“On a white wall, you draw allegories of rest,” writes the night poet Alejandra Pizarnik:

And they’re always of a mad queen who lies beneath the moon on the sad lawns of an ancestral garden. But don’t speak of gardens. Don’t speak of the moon. Don’t speak of roses or of the sea. Speak of what you know. Speak of the thing that rings in the marrow, that plays in your eyes with shadow and light … Just speak of the silence.

On the silent white wall of the moon, some draw a man. I had assumed, and wrongly so, that the Man in the Moon was a vision shared worldwide. “For us, it is a rabbit,” a poet from Mexico told me, explaining an Aztec myth of the creation of the sun. The legend involves two gods; rituals of self-sacrifice using feathers, gold, pus, and blood; and an entrance into fire—one god humble and willing, the other holding back, such that when he did enter the fire, the rest of the gods realized they couldn’t have two bright shining suns, and threw a rabbit into the reluctant one’s face, dimming its shine and leaving a bruiseshadow of the rabbit on its surface.

The moon rabbit exists for Japan, China, and Korea, too. In Chinese myth, it toils over a mortar and pestle, pounding out the elixir of life. An Angolan myth tells of the frog on the moon, one who traveled in a bucket to deliver a marriage proposal to the daughter of Lord Sun and Lady Moon. Some cultures see a toad; others, a crone. What’s there? What message does your mind bring back to you when you look? What news? In another state of mind, you might see monsters in the cloud or hellscapes on the ceiling, hear creep creep creep from the frogs. Same shapes, shadows, sounds; different messages entirely. Where’s the line between imaginative leaps and hallucinatory skewing, actual madness? Are we anytime so far away from a deeper fever?

Let’s speak of the moon. Let’s speak of gardens. Let’s speak of the fire of the fever, the ringing heat in the marrow. The Romantic poet and noted lunatic Gérard de Nerval—who’s said to have walked a lobster on a leash, among other eccentricities—lived now and then in a state of “what I shall call the overflow of dream life into real life. From this point on, everything at times took on a double aspect.” A double aspect: the twins real and unreal, siblings staring into the mirror of each other’s faces. A dam breaks and dream life overflows, like a sudden storm, like an eclipse, like a bleeding gash in time, every shaft of light and bend of grass sending signals to interpret. Nerval feverishly considers the “unbroken chain of men and women to whom I belonged and yet all of whom were myself.” He’s dizzied by permutations both “finite and unlimited.” How could anyone make sense of it? “You might as well query a flower about the number of its petals.”

We’ll ask the flowers. We’ll see what they have to say. May’s moon is the Flower Moon, and when I close my eyes I see a swirl of petal color. In the small city where I live, spring’s parade moves something like this: the witch hazel and the snowdrops, then crocuses, purple rockets in the mulch, daffodils, forsythia, then tulips—cupped, flirtatious tulips—azalea, lilacs, rhododendrons, and the peonies, now, the peonies, fistfuls of lingerie, and on as spring opens itself into summer. May, the most colorful month, exuberant twin to November’s gray austerity—it builds on April’s efforts and serves as the transition between glassy spring and summer lush. The trees toss “in what certainly looks like sexual arousal,” as Tony Hoagland puts it, “overflowing with blossomfoam.” As we are.

May resanguinates the world. Its very name asks a question, grants permission, holds possibility. So much potential energy. Warming days, increased light, petal smells, shoulders, sweat, and this year’s emergence out of quarantines—a collective spring fever spikes. It isn’t always pleasant. All the signals say, Here we are, awake, and heated to the touch. What do we do with it? Some answers come more readily than others. The animals are in a tizzy, too. At a cemetery pond earlier this month, I saw two ducks fuck. The mallard drake looked like he was having a seizure on the water; he then pecked the neck of his mate, mounted her, pumped for, what, ten seconds, and they web-footed it to shore for pillow talk as they preened. Opening, overflowing, all this thrashing and spilling.

What’s it got to do with the moon? We see a face, a rabbit, a frog, we’re wanting for meaning, for messages, for signals sent so we can understand. The future builds up behind us, but we can never turn all the way around to see it. Our minds clamber for something to grasp on to in all the indistinctness. The moon and the earth are in kissing distance, and tonight the earth will move between Lord Sun and Lady Moon for a total lunar eclipse. Earth’s shadow will give the moon a garnet glow, making it a blood moon.

Blood in the sky and blood on the street. I took a run on roads outside the city recently. Stone walls, wide barns, empty rolling fields. Near a vernal pond, a turtle had been crushed, freshly so, by a car. Flipped upside down, its amber undershell was smooth and cracked, red stripes around the rim. The red of the blood on the road was shocking in its aliveness. A small pile of the turtle’s guts, propelled from its body, lay shining a few inches away, coiled like a little heap of earthworms.

I am no haruspex, no seer, I cannot read the future in the splay of viscera across the cratered cement of a suburban back road. Guts on the street and there’s no telling what may happen next or what any of it means. Done examining the turtle, I continued on my run. Before my heart rate had a chance to rise again, another chance for prognostication, this time in the form of a frog who’d been flattened as well, the entirety of its insides squeezed out of its mouth. Poor small friends. Crushed and cracked open by the press of immediate need. The risk of wanting, the risk of seeking something new.

There were these two, the future spelled out in the angle of their intestines, and what I can see now, what those guts tell me now: there were others I couldn’t see, ones who’d made it safe across the street, to live and thrive in the face of all the risks, come what may. The future tugs on us, as the moon does, come what may. In a face, in a shadow, in the overflow of dream life into real life, in all the indistinct places, come what may, come what may, we wander the night gardens of our minds in search of something we can understand. Let’s speak of what we know, and then we’ll see what we hear in the silence.

Nina MacLaughlin is a writer in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Her most recent book is Summer Solstice. Her previous columns for the Daily are Winter Solstice, Sky Gazing, Summer Solstice, Senses of Dawn, and Novemberance.

May 24, 2021

The Magic of Simplicity

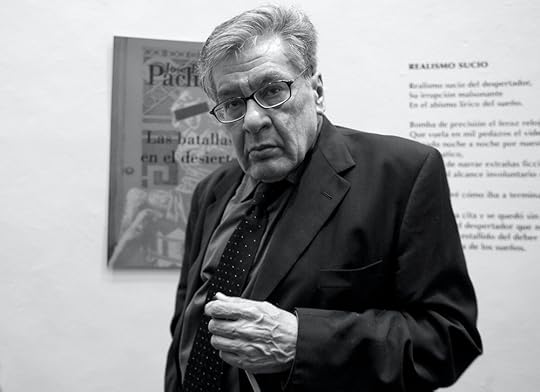

Photo: Octavio Nava / Secretaría de Cultura Ciudad de México from México. CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...), via Wikimedia Commons.

For decades, José Emilio Pacheco’s Battles in the Desert has been one of the most widely read novels in Mexico. Since its original 1980 serialization in the weekend cultural supplement Sábado and its subsequent publication, a year later, by the iconic Ediciones Era, this story of impossible love between a boy and his best friend’s mother has established itself as one of the most important novellas in Mexican literature, which boasts such gems in this genre as Carlos Fuentes’s Aura, José Revueltas’s The Hole, and Salvador Elizondo’s Elsinore: un cuaderno (Elsinore: a notebook), to name just a few.

The considerable reach of this novella is in large part thanks to its readers’ word-of-mouth recommendations over the years and the fact that, since its second edition, it became part of standard middle school and high school curricula throughout the country, especially in the capital, Mexico City, awakening among students of successive generations the kind of interest and awe that very few “required” or “compulsory” texts ever generate among adolescents. Cementing the widespread love for Battles in the Desert isn’t only its detailed portrait of bygone days, its appealing brevity and intimate, confessional tone, but also its glowing emotional credibility, so strong that many readers believe the story to be autobiographical, to the amusement and astonishment of its author.

Born in Mexico City in 1939, just a few months before the start of World War II, José Emilio Pacheco was first introduced to the magic of fiction at the age of eight, during a school trip to the theater at the Palacio de Bellas Artes to see Salvador Novo’s stage adaptation of Don Quixote. “On that now distant morning,” Pacheco would relate in his 2009 speech accepting the Cervantes Prize, the highest award in Spanish-language literature, “I discover that there is another reality called fiction. It becomes clear to me that my everyday speech, the language into which I was born and which is my only wealth, can — for those of us able to use it— resemble the music of that show, the colors of the costumes and the houses that lit up the stage.” This early calling led him to write what he called “little pirate novels” inspired by the adventure stories — by Salgari, Verne, Dumas — he began to devour around that time, and by his nineteenth birthday he had already tried his hand at every literary genre, publishing his work in newspapers and student magazines. After abandoning his law degree at the National Autonomous University of Mexico to fully devote himself to literature, he became part of the so-called Generación de Medio Siglo (Mexico’s midcentury literary generation) along with his friends Sergio Pitol and Carlos Monsiváis, as well as other writers who would rejuvenate Mexico’s national literature, such as Salvador Elizondo, Juan Vicente Melo, Juan García Ponce, and Inés Arredondo.

The Pacheco-Monsiváis-Pitol triumvirate in particular took pains to marry high and low culture in their works, catching the attention of younger readers. From his poems to his novels, his short stories to his journalism, from his translations, essays, and literary criticism to his historical works, José Emilio Pacheco took a rigorous approach to form and cultivated extreme clarity of content. For forty years, and across several publications, he published his renowned column Inventario (Inventory), combining his own special mix of forms (criticism, journalism, and the essay) and sharing with the general public his favorite book discoveries as well as his encyclopedic knowledge — all expressed in his unique conversational style, at once erudite and personal. It’s beyond question that his writing influenced his readers’ tastes and broke ground for many Mexican authors’ literary experiments.

Reading Battles in the Desert, one will note the special magic of Pacheco’s writing — that simplicity, so deceptive and so masterful. The narrative voice is a well-calibrated device gliding through the reality of things, stories, and emotions, always giving the impression that memory never betrays. “Pacheco’s craft and mastery make writing look easy,” writes Luis Jorge Boone in “José Emilio Pacheco: Un lector fuera del tiempo” (“José Emilio Pacheco: a reader outside of time”), an essay on the author’s work. “Achieving that almost magical ease took Pacheco years of rewrites, edits, cuts. The layers upon layers of work the author put into his books over the years is legendary.”

Lengthy prose poems he stripped down in their final versions to pithy lines. Translations took years of painstaking transference — his translation of Eliot’s Four Quartets into Spanish, for example, consumed more than two decades. Works of fiction went on being refined until the very last day their author was able to revise them: they were edited again and again in a firm rejection of conclusiveness. “I do not accept the idea of a definitive text,” Pacheco wrote in his notes to his complete poems, Tarde o temprano: Poemas 1958–2009 (Sooner or later: poems 1958–2009). “For as long as I am alive, I will go on editing myself.”

For its thirtieth anniversary edition, he went so far as to amend several sections in Battles in the Desert, including its ending, even changing the age of Mariana (a character inspired by the actress Rita Hayworth, according to Pacheco) to imply that the story was being narrated in more recent times: “I will never know if Mariana is still alive. If she is, she would be eighty years old,” declares the narrator of that anniversary edition. The first-serial Sábado version was shorter, and Pacheco said that Fernando Benítez, the editor, had to practically snatch it out of his hands to prevent him making further revisions.

That original version arrived, essentially complete, in a feverish session at his typewriter the day after the opening of an exhibition of lithographs by Vicente Rojo, where Pacheco had been interviewed about the poems he’d written to accompany Rojo’s works, channeling the horrors the artist had witnessed as a child in Barcelona during the Civil War. During that interview, and on subsequent occasions when he was asked about the origin of Battles in the Desert, Pacheco mentioned an idea that had recently affected him (and which he attributed to the writer Graham Greene): that childhood love, being hopeless, is also the saddest. The next day, from that one idea emerged the entire story of young Carlos’s woes —this was the story that Pacheco would continue to work on, revising it again and again until its 1981 publication by Era, at that time led by Neus Espresate, the legendary publisher who managed to persuade Pacheco that Battles in the Desert was a novella, and that it should be published separately and not as part of a collected stories, as Pacheco was convinced it should be.

During an interview shortly before his death in 2014, Pacheco was asked why nostalgia so imbues his stories. “We can only write about what is no more,” he replied. “Writing is an attempt to preserve something in the midst of all that disappears and is destroyed each day. But there is no nostalgia in my texts: there is memory.”

And indeed, there is no nostalgia for former times in Battles in the Desert; in its place there is testimony, recovery, and even denunciation of the historical transformations that, from the forties onward, would alter the colonial features of Mexico City and see it transformed into a megalopolis of skyscrapers and traffic that eventually engulfed the entire Anahuac valley, or Valley of Mexico, making room for the millions of migrants who would descend upon the capital looking for better living conditions: peasants displaced by the new agricultural systems, professionals fed up with the sleepy provinces, and foreigners fleeing fascism. And although leaders would continue to hail the ideals of the Mexican Revolution — land for the dispossessed, decent wages for the proletariat, and state intervention in economic affairs — a growing alliance between politicians and businessmen would usher in an era of unbalanced growth and social inequality. The consumerism of the opulent classes would exist hand in hand with the social neglect of the undermined majority, and the corruption that oils the wheels of commerce and industry would become commonplace. Though a large part of the capital’s population would preserve their traditional, provincial customs around food, family, and religion, the younger generations enthusiastically embraced the “North Americanization” made inevitable by the introduction of brands, food, technology, fashion, music genres, TV series, and movies from the U.S. This schism is precisely the “pivotal moment” that Pacheco so lucidly incarnates in his narrator’s intimate, familiar voice, telling us about the world of his childhood, the joys and sorrows of his school and family life, and that first passion, which hits him like a stab wound out of nowhere.

The story of an impossible love, the tale of desire in its purest and most defenseless form, the portrait of a city and country at the dawn of a radical transformation, the critical, unsparing evocation of a society plagued by institutional corruption (still the scourge of modern Mexico), Battles in the Desert is a reckoning with the past and an attempt to preserve what was, what is no more — that love and horror that Pacheco shows us with moving simplicity.

—Translated from the Spanish by Sophie Hughes

Fernanda Melchor was born in Veracruz, Mexico, in 1982 and is widely recognized as one of the most exciting new voices of Mexican literature. Her novel Paradise is forthcoming from New Directions in 2022. An excerpt from her novel Hurricane Season was published in the Winter 2019 issue.

Sophie Hughes has translated numerous Spanish and Latin American authors. She is currently translating Fernanda Melchor’s novel Paradise for New Directions.

Excerpted from Fernanda Melchor’s afterword to Battles in the Desert , by José Emilio Pacheco (translated from the Spanish by Katherine Silver), which will be published next week by New Directions. Courtesy of New Directions.

May 21, 2021

Staff Picks: Miners, Mauretania, and Melancholy

Chris Reynolds. Photo: Chez Blundy. Courtesy of New York Review Books.

Mauretania is a mood. Spend some time with Chris Reynolds’s The New World: Comics from Mauretania and you’ll feel it. Stark illustrations will envelop you in their contrasts—the blanket blacks of the foreground, the impossible star-bright skies—and you’ll find yourself thumbing anxiously for the uncertain medium of shadows. The characters will elude you—transient, distant, largely muted in their emotions—and their struggles will become your own as you search for meaning in an increasingly mysterious world. We tend to use the terms creepy or uncanny to describe such a mood. I’ve always liked the German word unheimlich. But that describes only a piece of the feeling that permeates these comics. For those moments when life is relatively fine and yet you can’t seem to shake the unease that manifests in everything from the building across the street to the sunlight that “roars across the fields” to the nearly programmable behaviors of the people around you, when you can’t remember why you entered a room, or when you’ve finished solving a problem only to realize you are just as confused as when you began, I propose the word Mauretania. An example: My local grocer no longer requires customers to wear masks, and the CDC says it’s all right, but it still feels a bit Mauretania in there. Things somehow feel Mauretania more and more. —Christopher Notarnicola

A lot has been said about Bennington College, with its unique educational model and the various well-known writers among its alumni (seriously, a lot has been said, and most of it is kind of wild). In “Bennington Girl,” however, Jill Eisenstadt explores the archetype of “the B girl,” a figure overrepresented in cultural production but underrepresented in discussions surrounding the college itself. (“Though the college still receives outsized attention,” Eisenstadt writes, “the focus is more on the school than the girl. Blame or credit the spread of progressive ed, #metoo or the achievements of B boys,” chief among them Jonathan Lethem and Bret Easton Ellis.) The B girl, Eisenstadt claims, is everywhere once you start looking for her. She is an “artistic, sexually bold, brilliant or flaky, monied, spooky (probably communist) free spirit.” She is an archetype, a trope—a caricature, really. The essay is incredibly well researched, diving into a wide array of B girls in literature and film and seamlessly drawing from Eisenstadt’s own experience at Bennington (she is, along with Donna Tartt, one of the non-male-identifying members of the so-called Literary Brat Pack that emerged from the college). After reading Eisenstadt’s essay, I returned to Tartt’s The Secret History. You may recall Camilla, one of the only women in the book and certainly the lone central female character. I’d argue that she is not a B girl, even if she is portrayed as humorously nymphlike. The (very few) other female Bennington students, however, largely fit the B girl profile. Take Judy Poovey, Richard Papen’s generally reviled neighbor, as a case study, with her red Corvette, her seemingly endless supply of any number of drugs, “a spandex top which revealed her intensely aerobicized midriff,” and her vocal desire to sleep with Richard (which she, our resident B girl, of course puts in “less delicate terms”). Like Eisenstadt says, once you start looking, B girls are everywhere. This is cheating, perhaps, considering that The Secret History’s Hamden College is an overtly fictionalized Bennington—but there’s Judy, B girl archetype, plain as day. —Mira Braneck

Brian Dillon. Photo courtesy of New York Review Books.

I’m late to Brian Dillon’s Essayism: On Form, Feeling, and Nonfiction, which was published in the U.S. in 2018, but luckily, when it comes to a book this profoundly thoughtful about the relationship between text and mood, there is no deadline or time limit. In a series of chapters that examine the essayistic writing of Elizabeth Hardwick, Virginia Woolf, Walter Benjamin, and more, Dillon slowly unspools paragraphs, sentences, and phrases until he is left with the thread of emotion, a personal story of depression that interweaves it all. The relationship between writing and depression is a long-standing and famous one, but Dillon adds new shades and colors, transforming a familiar palette into one both strange and thought-provoking. —Rhian Sasseen

It’s been a good month or so for readers of Natalia Ginzburg. Two novellas, Family and Borghesia, were released as a single volume by New York Review Books in April, and earlier this month her novel Voices in the Evening was reissued by New Directions, with an introduction by Colm Tóibín. Family, in a broad sense, is a through line in Ginzburg’s body of work, and all of these delight in the same wry observational humor that’s at the beating heart of her autobiographical novel Family Lexicon. For being closer to pure fiction, Voices seems in some ways a franker account of everyday life under and after Fascism than Family Lexicon is, perhaps finding a footing in being a step removed from reality. The novel is set in a “nutshell of a town,” where the dramas of several couples unfold around the village’s recent memory of a young man’s murder at the hands of Blackshirts, while yet another member of their close-knit socialist community is casually accepted as a Fascist sympathizer—a tension that rings true with how personal relationships muddle political lines. As for the novellas, one couple is at the center of Family, a relatively lighter tale that pokes fun at bourgeois notions of marriage, and the only relationships in Borghesia are between a widow and her many cats. All three of these stories have a subtle power that catches you at the end, and each sings with the characteristic wit and piercing clarity of prose that holds you rapt when you read her work. —Lauren Kane

One shouldn’t come to Jia Zhangke’s Artist Trilogy—a series of documentaries about painting (Dong), fashion (Useless), and literature (Swimming Out till the Sea Turns Blue)—with too many expectations of gleaning concrete information about the subjects at hand. Jia offers little explanation to the uninitiated viewer. Instead, the films are elaborate swerves, at first centering artists before exploding outward to encompass the more unexamined reaches of modern life in China: the day laborers who live and die on the job in Dong, the coal miners who scrub their bodies down after every shift in Useless, the farmers who toil amid endless fields of grain in Swimming Out till the Sea Turns Blue. These drifts in focus may frustrate the more impatient among us, but they serve to eradicate any barriers between artists and the material conditions within which they create. In setting out to pursue the truth of other art forms, Jia reveals mastery of his own: the images he captures are rich and indelible. —Brian Ransom

Still from Jia Zhangke’s Swimming Out Till the Sea Turns Blue, 2020. © Xstream Pictures.

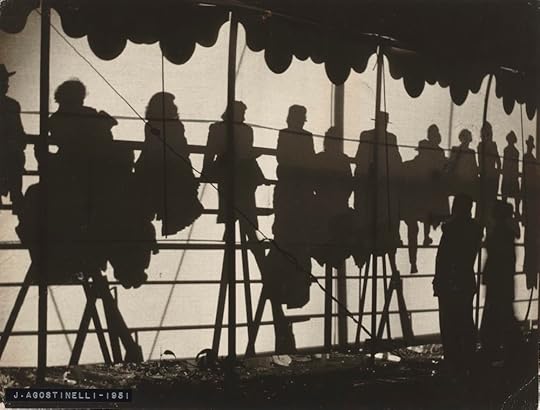

The Amateur Photographers of Midcentury São Paulo

Outside of Brazil, the achievements of the São Paulo–based amateur photography group Foto-Cine Clube Bandeirante have long been overlooked. Its ranks included biologists, accountants, lawyers, journalists, and engineers, all of whom were united in their passion for the art form. To encourage innovation, the club held monthly contests, which often resulted in photos that look unreal from today’s vantage point: crisp shadows of circus goers roosting on bleachers, nightmarish skyscrapers slurring across the frame, pedestrians wandering among the streetcar rails like planets locked in lonely orbit. Presenting the group’s work for the first time internationally, “Fotoclubismo” will be on view at the Museum of Modern Art through September 26. A selection of images from the show appears below.

André Carneiro, Rails (Trilhos), 1951, gelatin silver print, 11 5/8 × 15 5/8″. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Acquired through the generosity of José Olympio da Veiga Pereira through the Latin American and Caribbean Fund. © 2020 Estate of André Carneiro.

Thomaz Farkas, Ministry of Education (Ministério da Educação) [Rio de Janeiro], ca. 1945, gelatin silver print, 12 7/8 × 11 3/4″. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of the artist.

Julio Agostinelli, Circus (Circense), 1951, gelatin silver print, 11 1/2 × 15″. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Acquired through the generosity of Richard O. Rieger. © 2020 Estate of Julio Agostinelli.

Palmira Puig-Giró, Untitled, ca. 1960, gelatin silver print, 15 3/8 × 11 1/8″. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Agnes Rindge Claflin Fund. © 2020 Estate of Palmira Puig-Giró.

Aldo Augusto de Souza Lima, Vertigo (Vertigem), 1949, gelatin silver print, 11 × 14 3/4″. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Acquired through the generosity of James and Ysabella Gara in honor of Donald H. Elliott. © 2020 Estate of Aldo Augusto de Souza Lima.

Maria Helena Valente da Cruz, The Broken Glass (O vidro partido), ca. 1952, gelatin silver print, 11 7/8 × 11 1/2″. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Acquired through the generosity of Donna Redel. © 2020 Estate of Maria Helena Valente da Cruz.

Geraldo de Barros, Fotoforma, 1952–53, gelatin silver print, 11 7/8 × 15 1/8″. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Acquired through the generosity of John and Lisa Pritzker. © 2020 Arquivo Geraldo de Barros. Courtesy Luciana Brito Galeria.

Roberto Yoshida, Skyscrapers (Arranha-céus), 1959, gelatin silver print, 14 5/8 × 11 5/8″. Collection Fernanda Feitosa and Heitor Martins. © 2020 Estate of Roberto Yoshida.

“Fotoclubismo” will be on view at the Museum of Modern Art through September 26.

May 20, 2021

The Voice of ACT UP Culture

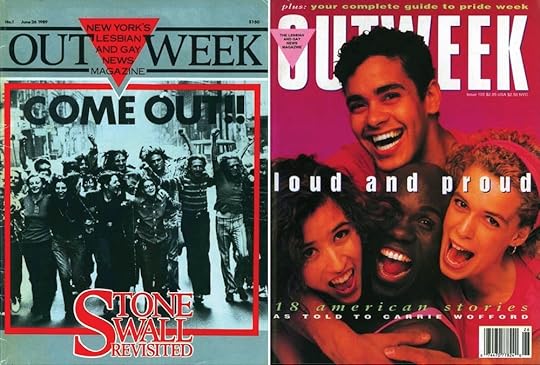

Sarah Schulman’s new book Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987–1993 is the culmination of twenty years of research, interviews, and writing on the history of American AIDS activism and the grassroots organization ACT UP. In the excerpt below, Schulman describes the impact of OutWeek, the first major national publication to call itself a lesbian and gay magazine, through some of its founding members.

The first and last covers of OutWeek magazine, published weekly from June 26, 1989, until July 3, 1991. Images from the OutWeek Internet Archive and courtesy of Gabriel Rotello. Photo credit to Jim Fouratt and Michael Wakefield, respectively.

In the eighties and nineties, queer people were excluded from authentic representation in corporate television and film, both news and entertainment, and most lesbians as well as queer people of color could not get serious stage time for plays from their points of view. As a result, print was the most important venue for community communication. Queer and feminist bookstores were all over the country. In 1992, I was able to do a book tour that stopped in each gay bookstore in the U.S. South. Every big city had a least one gay and/or feminist newspaper, and some, like San Francisco, had more than three. Most heterosexuals, whether civilians, scientists, civic/political leaders, or cultural gatekeepers, did not read the queer or women’s press because, frankly, they didn’t know it existed. The walls between countercultural queer life and the official mainstream were thick and invisible. The queer press was made for queer people, and it both reflected and created the countercultural bonds that built community.

*

ANDREW MILLER

Andrew Miller grew up a “squirrelly, hypersmart, bookish, musical, isolated kid,” who was also gay, and he was afraid early on because he lived through a time when lots of his friends died. But the cataclysm crept in through a kind of slow unraveling of the fabric of our community, “through lack of information, and fear, and not having answers, and being sick, and not knowing what to do, or having somebody else be sick, and not knowing how to fix it, and not knowing if you were gonna get it, and not having anybody that you could ask about it, or not wanting anybody to know … not being able to tell anybody else.” Andrew remembered rushing out to get his passport, because there was a six- or nine-month period when President George H. W. Bush and Congress were considering making an HIV test a requirement for getting one.

Andrew joined the ACT UP Actions Committee and the Coordinating Committee while working as a stringer for out-of-town gay weeklies. He was writing for the Bay Area Reporter (San Francisco) and Windy City Times (Chicago) and, most of all, Gay Community News (Boston). At this time, around 1988, the situation in New York with the gay press was dismal.

“The only game in town was the New York Native, which had broken the story about AIDS and had some wonderful writing in it, originally, including by Larry Kramer, also some really solid reporting. But by this time … they refused to believe that HIV was the cause of AIDS and their reporting was getting very bizarre. They had become very hostile to ACT UP … My frustration was that often there were better stories about New York—often by me, but also by other people—in the papers in Chicago and Boston than there were in New York. And I hated this … there wasn’t a way to circulate meaningful information.”

Andrew met Michelangelo Signorile at ACT UP. Mike had been talking to Gabriel Rotello, who had access to someone who could provide funding. That person turned out to be a PWA businessman named Kendall Morrison, a phone sex entrepreneur who made his money from a service called 550-TOOL. Kendall was in ACT UP, and he signed on to fund the publication. A paper was also a way for him to have a vehicle in which to advertise his phone sex lines. “So he was a smart businessman.”

*

MICHELANGELO SIGNORILE

OutWeek came about when a bunch of people who had been working on the Media Committee, along with others in ACT UP, were talking about how they needed a publication, something that would be the voice of the new bold, oppositional, and coalitional politics coming out of ACT UP. Sex was very much a part of the ACT UP culture, so having phone sex ads, as a result of Kendall’s patronage, “just seemed appropriate and fine.” There was never really a clear delineation between OutWeek and ACT UP—not only in the coverage but also on the business side. It was widely distributed on corner newsstands in the city, and “other people were reading it who hated ACT UP, and hated OutWeek, but they would read it.” So it was broadening the debate to more people who needed to be engaged.

*

ANDREW MILLER

Gabriel was the editor. Mike was the features editor. Andrew was the news editor. Maria Perez became art director, and Sarah Pettit was arts editor. OutWeek’s cultural framework intersected with ACT UP’s. It covered shows by ACT UP artists, reviewed books by ACT UP authors. Maria Perez’s visual style was very downtown and contemporary, a combination of camp and sophistication. Handmade and sleek, it was interactive with ACT UP’s countercultural aesthetic. When there were rifts in ACT UP, OutWeek covered them, and when ACT UP attacked politicians, OutWeek always asked them for a response. Its main political difference with ACT UP was that OutWeek endorsed candidates for public office, which ACT UP would never do. Even with a small regular circulation of ten thousand, the weight of being on New York’s political and cultural cutting edge gave it a long reach. “Gay people weren’t out in publishing, to the extent that they are today. OutWeek made it possible for there to be a National Lesbian and Gay Journalism Association.” Gay Community News in Boston was the only other queer newspaper so closely aligned with activist movements. The national gay press, especially The Advocate, started out bold, but as the community expanded, it remained white male oriented and thereby became more driven toward assimilation. The Advocate also gave up its sex ads in order to attract the first mainstream brand, Absolut Vodka, that dared to advertise in a gay publication. One Advocate editor told me that when they put anyone but a white male on the cover, they lost sales. OutWeek, on the other hand, regularly had women, people of color, drag performers, or genderqueer people on the cover. The publication closed in 1991, a year before ACT UP’s split, and no queer publication has been both that cool and that influential since.

*

GABRIEL ROTELLO

Gabriel Rotello was raised in “WASP Connecticut.” His mother was a teacher, and his father invested in real estate. He moved to New York in 1974 and became a keyboard player. His partner, Hap Hatton, got sick in 1986 and died two years later. Gabriel went to a support group at GMHC and then saw ACT UP’s concentration camp float at Gay Pride. What stood out for him in ACT UP was the structure. There was no hierarchy. There were no paid officials. There were no offices.

He joined the Fundraising Committee, and then, one day, “this light bulb went on in my head, and I thought, Oh my God. What if somebody started a new publication that reflected what’s going on in ACT UP?” Gabriel went to Barnes & Noble and bought two bags full of books on how to start a magazine, read them all, and took notes. He made a list of, in his opinion, the smartest lesbians and gay men in New York who had been involved in politics in ways that he had not been involved. He called them all up and said, Hi, my name’s Gabriel Rotello. I’m going to start a new gay magazine in New York, and I would love to just meet with you, and you could just tell me everything that I need to know. And every single one of them said yes. The way he understood it was that he created his own, independent affinity group, and OutWeek clearly could not have been an affinity group of ACT UP, because it was a commercial enterprise that cost about a million dollars overall. Yet it was far from traditional. Gabriel knew that they were not going to get corporate ads. “We were calling the cardinal a fucking pig.” Sometimes, when something particularly outrageous was on the cover, they could ramp up the print run to thirty or forty thousand and sell out. Even if it was just a typical week and it was the middle of summer, OutWeek could print fifteen thousand copies and sell out, running on a combination of circulation and queer-friendly and countercultural ad revenue. The pharmaceutical companies didn’t even try to advertise.

OutWeek’s biggest controversy had nothing to do with ACT UP directly, but everything to do with AIDS: outing. Initiated by Michelangelo, the goal of outing was to confront powerful people in positions to influence AIDS policy who hid their homosexuality—usually to maintain their currency—and in this way deprived the AIDS community of arenas of support and visibility that were necessary to shift the paradigm. “At the end of the day, I think you can put on the fingers of one hand the names of the famous people that we actually outed. We talked about it as breaking a barrier in journalism.”

*

THE WOODY MYERS CONTROVERSY

The overwhelming majority of the lesbian and gay vote had turned against Mayor Koch because of his languid response to AIDS, and instead supported Mayor-Elect David Dinkins. As one of his first orders of business, Dinkins announced that he was appointing a man named Woodrow Myers to be his new health commissioner, who would be in charge of AIDS policy. Myers, who was Black, had previously been health commissioner of Indiana. Dinkins was the first African American mayor, and African Americans had a huge number of health issues in New York City. Gabriel began calling people in the Indiana state government to find out what Myers was like, and he discovered, to his horror, that Myers had advocated for mandatory contact tracing, mandatory name reporting, and the quarantining of people with AIDS in Indiana. And everybody Gabriel called said the same thing. “It was common knowledge in Indiana.”

OutWeek came out every Monday, the same day as the ACT UP meetings. Gabriel wrote a story, five days before publication, during which time the mayor might actually appoint Myers. And Gabriel felt that the scoop couldn’t wait. So he called the New York Times and said, I have a story that I think that you’re going to want to put on the front page of the New York Times, but it’s going to be on the cover of OutWeek next Monday. But we sort of feel like we can’t really wait, so I will give you the story, provided that you credit it to OutWeek magazine in your lede. And they said, Well, let’s see what it is.

So he faxed it over, and about five minutes later, they called and said, It’s going to be on the front page of the New York Times tomorrow, and it’s going to say “OutWeek magazine” right in the lede. And that started what has often been called the most bitter dispute of the Dinkins administration. In typical OutWeek fashion, they ramped it up: there had been a selection committee for Woody Myers, and there was a very prominent gay person on that committee named Tim Sweeney, who was the associate director of GMHC. Gabriel called him up before the Times ran the piece and asked, Did you know about this? You were supposed to be vetting this guy or anybody for Dinkins. And Tim said, Yeah, I did know about it, but I didn’t really think it was that big a deal. You have to understand, Indiana’s a very conservative state. I actually felt that he was sort of taming even worse things that might have happened in Indiana. He was trying to keep it from being even worse than it was going to be. And he seems like a really nice guy, and I met him and he was really great. Gabriel called everybody back up in Indiana and said, What’s up with this? They were like, Are you kidding? He was the guy. Nobody even talked about contact tracing or mandatory name reporting until he came along. It was his idea. What are you talking about?

In OutWeek’s role of trying to keep gay leaders accountable to the grassroots, Gabriel wrote a strongly worded editorial, in which he excoriated Mayor Dinkins. He said, He’s broken the vow. We regret having endorsed him for mayor. He’s proven himself to be an enemy of our community. And then he called for Tim Sweeney to resign or, if he refused to resign, for the board of GMHC to fire him. That’s the kind of thing that OutWeek did on a fairly regular basis.

“In ACT UP there was accountability. You got up to say something on the floor, and if you were an asshole, people screamed at you and told you. It was like Parliament in London, Get off! Sit down!, you know, whatever. But with our [greater queer] community, there was this self-perpetuating group of people, boards of directors that were dominated by very wealthy people. That’s mostly how you got on a board; you were really rich and you had lots of money, then you would sit on the board and decide the policy and elevate various people, and there was just no accountability.”

The next week the letter section exploded in OutWeek, with a number of leaders of gay and lesbian organizations calling for Gabriel’s resignation. But Gabriel experienced a lot of people supporting him, indicating a more radical turn in the general stance of the community toward its own organizational boards. “And it just turned into this cacophonous thing.” Sweeney did not resign, but Woody Myers did. And he was replaced by Margaret Hamburg, who had previously worked closely with ACT UP in Washington at the NIH. The threats of mandatory testing were averted, setting an entirely different tone for the future of AIDS in New York City.

“What we were trying to do—in OutWeek—was to take the vision, or at least my vision, of what the floor of ACT UP was, that energy, that anger, that whole worldview, and just send it out to the world. To people that could never make a Monday-night meeting because they lived in Des Moines, Iowa, or Tallahassee, Florida, to a high school kid that could never even get to New York. Just to send that out there to inspire people to believe that we could get through this nightmare, you know, with strength and positivity and power and humor and effectiveness.”

Sarah Schulman is the author of more than twenty works of fiction (including The Cosmopolitans, Rat Bohemia, and Maggie Terry), nonfiction (including Stagestruck, Conflict is Not Abuse, and The Gentrification of the Mind), and theater (Carson McCullers, Manic Flight Reaction, and more), and the producer and screenwriter of several feature films (The Owls, Mommy Is Coming, and United in Anger, among others). Her writing has appeared in The New Yorker, the New York Times, Slate, and many other outlets. She is a Distinguished Professor of Humanities at College of Staten Island, a Fellow at the New York Institute of Humanities, the recipient of multiple fellowships from the MacDowell Colony, Yaddo, and the New York Foundation for the Arts, and was presented in 2018 with Publishing Triangle’s Bill Whitehead Award. She is also the cofounder of the MIX New York LGBT Experimental Film and Video Festival, and the codirector of the groundbreaking ACT UP Oral History Project. A lifelong New Yorker, she is a longtime activist for queer rights and female empowerment, and serves on the advisory board of Jewish Voice for Peace.

Excerpted from Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987–1993, by Sarah Schulman. Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux on May 18, 2021. Copyright © 2021 by Sarah Schulman. All rights reserved.May 19, 2021

Over Venerable Graves

Robert Cutts, The Graveyard of St. Mary’s Church, Fishpond, 2009. CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...), via Wikimedia Commons.

Here’s what happened: I was looking at pictures someone sent me from Germany, and one of them was particularly striking. Winter, a dark forest or maybe a park, and a narrow path winding its way right to a church, and a giant Christmas tree all decked out in glorious lights, and the sky above looks not like Germany but more like Gzhel porcelain or Vyatka toys, dark blue with enormous cold stars. On my tiny screen, the tree was lit like a bonfire, and it looked like a perfect postcard if you wanted to, say, wish someone a happy new year; all it needed was a couple of words appropriate to the occasion.

I sent the card (“good tidings in the new year”) to several people, some of them even responded, and a month later I opened the picture file again. But then—well, yes, the dark forest or park with its snowy hills, the shrubs, the church, the spruce—of course this was a cemetery. I have no idea how I failed to notice it the first time around.

But it’s quite easy not to see the cemetery, it is always in your head anyway; any thought brought to its endpoint will brush up against it: unmarked graves, half-covered in snow, and at the end of the road a spruce (“All the apples, all the golden ornaments”), and not much further—the church, we-all-fall-down. As the Orthodox hymn for the repose of the deceased says, “The whole world is a common, sacred grave, for in every place is the dust of our brethren and fathers.”

For some reason it matters to us how much space will be set aside for each and every person. The old jokes about six feet of English soil (“and since he’s taller, we’ll add one more”) can be easily put into the language of the Vagankovo cemetery. As if the size of our last earthly allotment meant something—and the more space surrounds you, the greater, freer, sweeter the rest. The obscure meaning of posthumous landownership (“Though senseless flesh will hardly care / Precisely where it goes to rot”) alludes to a merger with the landscape—or an acquisition that doesn’t require expert witnesses. Meanwhile, the earthly lot of the dead is shrinking before our eyes, which is hardly just the result of overpopulation and lack of space.

W. G. Sebald’s essay “Campo Santo” was published posthumously in a book in which three or four essays sketch the deliberately incomplete outline of a journey through Corsica. These essays leave a strange impression, as if the author were approaching the light at the end of that tunnel we’ve heard so much about from popular literature. The narrator and the narration thin out over the course of their movement, they are dissolved in quick flames; the very language and its objects—Napoleon’s uniform, the school fence, the village burial rituals—are in equal measure blinding and transparent. The author crosses over, the letters stay behind. It’s not surprising that the central text in this book is about a cemetery.

There, Sebald laments the fact that there are no ghosts to be found in Corsica anymore. The way he describes them (short, with blurry features, always at a slant from reality, petulant like children, and vengeful like jackdaws), there isn’t much to lament. But the fact that the local dead were no longer left offerings of food and drink (on doorways and windowsills), that they stopped frightening their fellow villagers on late-night roads, that they stopped visiting relatives and strangers, saddens him more than you would expect. His strange compassion for these unpleasant creatures, his visible displeasure that they have to lie in the narrow communal cemetery instead of on their own land, or the fact that the living and dead no longer exist on equal terms, seems suspiciously personal—as though the author had a vested interest here, as though this were his very own sorrow. And that is in fact true: this essay was written from—and on—the side of the dead. The uneasy urgency that Sebald’s own end, a senseless death in a car crash, gives this text forces us to read it all in italics, like an urgent missive from the end of the world, from the borderlands between here and there. The trouble is that, if we are to believe its message, there is no difference between here and there.

The dead mean less and less to us, Sebald says. We clear them from the road with the utmost speed and great zeal. They take up less and less of our time, they take up less space: cremations, urns, little cells in a concrete wall. “And who has remembered them, who remembers them at all?” He describes cemeteries as if they were prisons or reservations (designed to isolate, edge out, weigh down with granite and marble, to deprive the dead of their own, to surround them with strangers). He mourns the things that knew how to live on for decades (we remember what those were like: a father’s coat, worn for years by his son, a grandmother’s thimble, a grandfather’s geometry box, a memory of mother—a ring or an armchair) and suddenly found themselves replaceable. The absence of the will to preserve, which has gotten a hold of all of us, can also be described in another way, as a military operation or social reform: its task is an abolition of memory.

Indeed, the past is so broad that, it seems, we want to hem it in a little, to reduce all of it into less: just the important stuff, just the good parts. The idea that history (and culture) has a short and a long program, a top five or ten (the way only the church bells of the sunken city of Kitezh rise out of the lake) is not new. What’s new is how strangely weary we are of everything that preceded us. The new currents—theories in the vein of Fomenko, which compress time and space into a single point; educational reforms, with their inevitable cuts to the humanities—are all driven by the simpleminded desire to make things more simple. So that the well is a little less deep, so that there is less homework to assign, so that the buzzing mass of lived experience can be rolled up into a compact, taut ball (or rolled out into a transparent thin crepe). To use Sebald’s own words, “We have to keep throwing ballast overboard, forgetting everything that we might otherwise remember.” Under our feet, there’s either the raft of the Medusa or a rock “no larger than the head of a seal jutting out of the water” from the old fairy tale. On it, the present is living out its time: washed by the sea of the dead, half-drowned in the past, half a step away from death and oblivion, eyes tightly shut.

When the past is not preserved but discarded (the way you might clip hair or fingernails), the dead have fallen out of favor. They find themselves in the position of an aggrieved minority. They lose the right to our attention (and the ability to dodge said attention); they no longer have a say—they are remembered as others see fit. In a way, they are beyond the purview of the law: their possessions belong to others, anyone can insult them, we don’t know anything about them, but we act like they don’t even exist. Cemeteries, these ghettos for the dead, move to the outskirts of large cities—beyond the threshold of the everyday, where the living can only venture a couple of times a year, with dread, as if crossing a front line.

Because the first thing a cemetery conveys—any cemetery, large or small, covered in marble sculptures or in weeds and nettle—is the actual bulk of everything that came before me (“I had not thought death had undone so many”). Our natural inclination to look at history as an exhibit of accomplishments (or a sequence of traumas) is suddenly pushed out by other kinds of histories. Cooking pots, bedsheets, irons, porcelain, faience, diapers, baby powder, hollow gold rings, underskirts, postcards from the city of Gorky, a Niva edition of Chekhov, sleds, a Napoleon cake, union fees, ring four times, theater clutch bags, two-kopeck coins, quarter-kopeck coins, a monthly pass (September), a vocabulary notebook, a butter dish, a mimosa, a ticket to the Moscow Art Theater. Over each grave, like a post, like a beam, there is an invisible (maybe glowing, maybe devoid of any color or weight) mass of what has been. It reaches as high, it seems to me, as the sky, and indeed the sky rests on it.

What is memory to do in a world of overproduction—when there is so much surrounding us, so many old pots, featherbeds, glasses cases? So many dead languages and so many unmarked and abandoned graves? At the old Jewish cemetery in Prague it went like this: There was very little space, and many dead people, and time passed year after year. The dead were buried in layers, one floor atop another, and when they came up against an old headstone, they would pull it out and put it right next to the new one, like a row of steepled houses. This seems like the fate of any attempt to bury one’s dead: you try to dispatch a dead idea underground, and an older one works itself loose underneath it, and not even one, but three, like the heads of the hydra. That’s what history looks like from a fixed vantage point: layers and layers of accidental proximities and irresponsible analogies; from this perspective it really seems that it’s time to digest the past. To draw out (of the organism) the excess, the unnecessary, the things that have been weighed in the balances and found wanting. To leave the nutritious, the beneficial, the usable. To remove the typical, to leave in the singular. At last, to establish a vertical.

But everything about the reality of graveyards resists the vertical. The trade of the dead is, in the most literal sense, horizontal; their bodies and their deeds prove the futility of any kind of selectiveness. Rows, and rows, and rows, names and dates, if you can even find a name. A giant day care, a nursery with millions of beds—that’s what it looks like, if you imagine for a minute that the sleepers might wake. A dormitory under the open sky, with little beds (and bunnies on each cubby). And look how many of us there are.

If one believes that our true home is not here but in the open sky, any one thought will come up against the cemetery and move along it like a runway. I like to picture it like the cemetery in Rome whose name can be translated as the heterodox cemetery, Cimitero Acattolico. There are stone pines, and cypresses, and quiet, sluggish cats, and an old city wall, and an Italian (farsighted) sky. Persephone’s pomegranates ripen, splatter, and spill their seeds over the footpaths. There lie people with strange fates—those who died far away from home (and if everything other than heaven is a foreign land, we will all meet the same fate). Young women (“beloved wife of so and so”—of twenty-two, twenty-six, nineteen years and six months, February 6, 1842). Young children (“Wordsworth attended the christening,” the stone says) and grown children (“son of Goethe,” the stone says). Keats, Shelley, Viacheslav Ivanov (representatives of the vertical). And behind them, and in front of them, and together with them—all-all-all, all the epithelium of the past and present, hoping (or not) for the resurrection of the dead. Fourth-rate writers, third-wave emigrants, no-name Germans and Danes, old Russians and new Romans. Kôitiro Yamada, born in Hiroshima (“of Aki Province”), died in Rome thirty-three years later—on the fifteenth of January, 1883. Shiny thickets of acanthus. A stone boy in tall boots. “Thy will be done.” “Zum Licht.” “Harmony, harmony was your last sigh.”

“Sacred

To the Memory of Robert

The eldest son of Mr. Robert Brown,

of the City of London, Merchant.

Who unhappily lost his Life at Tivoli by his

Foot slipping, in coming out of Neptune’s Grotto,

on the 6th July 1823.

Aged 21 years.

Reader Beware

By this Fatal Accident

a Virtuous and Amiable Youth has been

suddenly snatched away in the bloom of Health

and pride of Life!

His disconsolate Parents are bereaved

of a most excellent Son,

His Brothers, and Sisters have to lament

an attached, and affectionate Brother,

and all his Family and Friends

have sustained an irreparable Loss.”

“Under this stone

rests the body of the former psalmist

of the Imperial Russian Mission,