The Paris Review's Blog, page 110

June 24, 2021

Strawberry Moon

In her monthly column The Moon in Full, Nina MacLaughlin illuminates humanity’s long-standing lunar fascination. Each installment is published in advance of the full moon.

Watercolor illustration from Aurora consurgens, a fifteenth-century alchemical text. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Summer now, and the petals are wet in the morning. The moon was born four and a half billion years ago. It’s been goddess, god, sister, bridge, vessel, mother, lover, other. “Civilisations still fight / Over your gender,” writes Priya Sarukkai Chabria. Dew is one of its daughters—or so the Spartan lyric poet Alcman had it in the mid-seventh-century B.C.: “Dew, a child of moon and air / causes the deergrass to grow.”

Cyrano de Bergerac, twenty-three hundred years later, imagined a dew-fueled way of getting to the moon. “I planted myself in the middle of a great many Glasses full of Dew, tied fast above me,” he writes in his satirical A Voyage to the Moon, published in 1657. If dew rises to the sky, evaporating into the atmosphere, he reasons, enough ought to take him, too. He lifts off, but “instead of drawing me near the Moon, as I intended, she seem’d to me to be more distant than at my first setting out.” He smashes a few dew vials and drops back to earth. A firework rocket gets him where he wants to go, and on the moon he meets a Spaniard who’d arrived there pulled by birds.

This figure, the space archaeologist Alice Gorman points out, alludes to a text published a few decades before de Bergerac’s work. Francis Godwin’s The Man in the Moone tells the story of a Spanish soldier who’s pulled to the moon by twenty-five swans. He launches on his lunar adventure at the moment in the year when the birds fly south.

But Godwin didn’t know that south was where the birds went. Sometimes we forget to think of what we know. In the seventeenth century, Europeans had no idea where the birds went in winter. Every year a mystery. One November morning, off they flew, only to drop out of the sky again come spring. In 1684, Charles Morton—a “renegade physicist,” according to Gorman—wrote a pamphlet arguing that storks spent winters on the moon.

Storks bring the babies, blanket bundles in their beaks. How wholesome, how Hallmark. How horrifying the fairy-tale origin story, the children’s book author Katherine Rundell reminds us in the London Review of Books. In 1839, Hans Christian Andersen wrote of a group of young storks who are teased by some kids, led by one boy, taunting with a song about the storks getting stabbed, hanged, and roasted. The young storks are fearful, then want revenge. Their mother tells them no, you cannot peck their eyeballs out; learn to fly instead; you’ll need to know so we can fly to the pyramids and eat frogs and snakes all winter. The young ones learn to fly but don’t give up on wanting payback. The mother comes up with a solution.

I know where the pond is where all the human babies lie till the stork comes and fetches them to their parents. The pretty little babies sleep and dream such lovely dreams as never come to them afterwards. All fathers and mothers want a little child like that, and all children want a sister or a brother.

We’ll fly to that pond, she says, and bring babies to the children who were not cruel; the ones who were, no little sibling for them. But what of the mean ringleader, the young storks ask.

In the pond there lies a little dead baby that has dreamt itself to death; we’ll take that to him, and he’ll cry because we’ve brought him a little dead brother.

Ice water spills down the spine from a cup at the base of the skull. Not just at the thought of this afloat and swollen blue-lipped dead brother, which makes me feel like I’m biting ice, but the babies in the pond dreaming dreams lovelier than they’ll ever dream again. A lonely, chalk-light sadness, that: all our best dreams behind us, warm amniotic celluloids unspooling before we’re born. “All children want a sister or a brother.” I think it’s probably true. A lack filled, a teammate under the circus tent. Artemis, moon goddess, was twin to sun god Apollo, and golden-horned deer pulled her chariot. NASA aims to put a woman on the moon by the end of this decade as part of the Artemis Program, twin to the Apollo 11 moon landing in 1969. They weren’t rivals, Artemis and Apollo, not this particular pair of sun-moon twins. “Like two mirrors in love with their likeness,” as Octavio Paz put it about siblings. But no matter what, a stork unloading a sibling before flapping back to the moon or swallowing snakes by the pyramids is a delivery received not without ambivalence.

Maurice Sendak captures this ambivalence in his 1981 masterpiece Outside Over There. Ida is the older sister. Her father is away at sea; her mother stares into the nothing, a chilling goneness in her eyes. Her baby sibling wails. Ida (a name as close to id as it is idea) minds the child and turns her back to practice her horn. As she plays, the goblins come with hooded heads and black cave faces. They steal the baby from the cradle and leave an ice baby in its place.

I turned the page to this illustration recently, having last seen it when I couldn’t yet read, and it sent a jab through my center; a hot-cold fist clenched my heart. As it did when I was small. As it did every single time. How strange, what the body remembers. Would you feel it, too, if you hadn’t seen it as a child? If you turned the page to see that ice baby in the cradle now, would it jolt you? The haunted uncanniness of the swollen ice moon baby face, its stiff body and blank stare, dead light coming from its eyes, looking right into you and not seeing you at all. Ida—who in dark and secret moments maybe wished her sib away, tired of the crying, who maybe wanted to refocus her mother’s million-mile stare, who maybe didn’t know that’s what it was she wanted—storms when she realizes the baby’s gone, furious at the thieving goblins, and at herself for turning her back. Brave Ida wraps herself in her mother’s golden velvet cloak and floats backward out the window into the titular outside over there.

This fury and devotion: she has to save her sibling. Sendak draws the dreams that unspooled in the pond, touching at the things we know without knowing, that live in the subsurface atmospheres of our shadowy and unexplored interiors. Caves, ladders, lanterns, shepherds, bridges, boats, ruins, rivers, thrashing seas. The hooded goblins carry the baby away, and Ida floats in her draping robe. (Some have said the folds of the fabric nod to Bernini’s The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, and I see it, too, but I was not leaning against my mother’s shoulder as a four-year-old thinking, Ah, yes, Bernini.) The full moon appears on each page of her search, cloaked by cloud and hidden by cliff until after Ida charms the goblins, when it emerges in its uncurtained dawnlight fullness. “Ida played a frenzied jig, a hornpipe that makes sailors wild beneath the ocean moon.” The goblins dance themselves into a frothing frenzy, and Ida is reunited with her sibling, who’s cooing in an eggshell, sweet as a strawberry, and ready to go home.

We build ladders made of myths and misconceptions, fairy tales and picture books, satellites, spaceships, and probes, cows jumping over goodnight moons, to climb back into the mystery, to try to make better sense of where we are and what we’re doing. The dreams that came to us in the pond must exist in our memories, making quiet home in some distant pocket of our minds. Is this the home we’re trying to return to? To some shared memory of the dream before we were born? “There is no ‘the truth,’ ” writes Adrienne Rich, “truth is not one thing, or even a system. It is an increasing complexity.” We’re all babies in our sleep, vulnerable and soft, dropped into the dark territory, the moon a shifting guardian keeping cool watch out the window, protective older sister.

In Aztec myth, Coyolxauhqui is the goddess of the moon, older sister to the sun god Huitzilopochtli. Coyolxauhqui and her four hundred other brothers were not pleased when their mother, the goddess Coatlicue, found herself pregnant by a bundle of feathers that fell into her lap. Disgusted and ashamed, they made a plan, hatched by Coyolxauhqui, to murder her. Coatlicue was warned, and as the brood approached, out burst the armored full-size Huitzilopochtli from his mother’s body. He dismembered Coyolxauhqui. He chopped off her head and flung her body parts across Coatepec—or Serpent—Mountain. It’s been written that the dawn sun murders the moon each morning. I think the truth is more complex: collaboration more than violence, an allegiance and shared power.

Chandra, god of the moon in Hindu mythology, has four arms and twenty-seven wives. In certain yoga practices it’s believed that two channels of energy line the spine, ida and pingala. Pingala, associated with the sun god Surya, rises up the right side, and is linked with the solar, the extroverted, heat and light. And ida (id, idea) lines the left, linked to Chandra, the lunar, the shadowy, cooling, and instinctive. The channels rise over the skull, intersect at the third eye, and end in each nostril. Can you feel moon juice rising up the left side of your spine? Is your ida open? Breathe in.

Maybe in your life you have pressed your forehead against another’s forehead. And maybe in that moment, you were not mother or father or child or sister or brother or friend or lover. Maybe in that moment, you were two skulls, two moons, hidden behind a thin cloud of forehead, behind a thin mist of eyelid, two skull moons glowing against each other, skull curve surface touching, eye sockets cratering, and the increasing complexity of truth collecting in the dark and infinite space that pooled in the shadowed place at the backs of your heads. The shadowed half of the moon is where the dream visions collect before they’re sent to the pond to be dreamed and forgotten.

We do not need vials full of dew or twenty-five swans, a rocket or a mother’s velvet cloak to feel the magnetic contours of another body in space. Bone against bone, moon against moon, your skull and my skull, and the depthless dark ponds inside them.

Nina MacLaughlin is a writer in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Her most recent book is Summer Solstice. Her previous columns for the Daily are Winter Solstice, Sky Gazing, Summer Solstice, Senses of Dawn, and Novemberance.

June 23, 2021

Watch the Summer 2021 Issue Launch

This past week, the extended Paris Review family gathered online to celebrate the launch of the Summer 2021 issue. If you weren’t able to tune in, you can watch a recording of the event below. You’ll see Kenan Orhan reading from his story “The Beyoğlu Municipality Waste Management Orchestra,” Ada Limón reading her poem “Power Lines,” and Kaveh Akbar reading his poems “An Oversight” and “Famous Americans and Why They Were Wrong.”

There’s more where that came from: check out the rest of the Summer 2021 issue now. And if you enjoyed the above, don’t forget to subscribe! In addition to four print issues per year, you’ll also receive complete digital access to our sixty-eight years’ worth of archives.

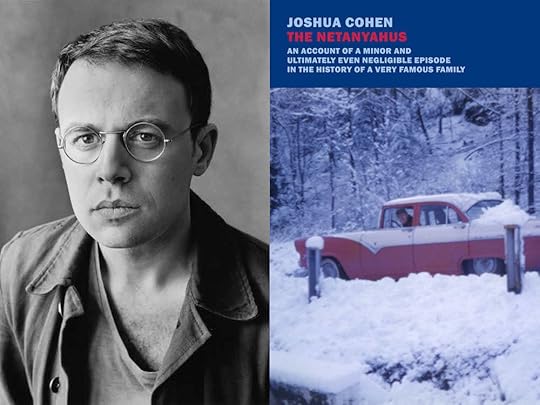

The Covering Cherub: An Interview with Joshua Cohen

Photo: Marion Ettlinger.

At 248 pages, Joshua Cohen’s latest novel, The Netanyahus: An Account of a Minor and Ultimately Even Negligible Episode in the History of a Very Famous Family, is slim by his standards. His 2010 comic novel Witz comes to 824 pages. Book of Numbers is just shy of 600. Beyond page count, there is an instantly recognizable intensity to Cohen’s writing, and in this respect, too, The Netanyahus is a bit of an outlier, for it unfolds with the ease of an anecdote, a comic—if cautionary—tale.

Published in the U.S. this week by New York Review Books, the novel follows a series of events surrounding a job talk in 1960 by the conservative religious historian Benzion Netanyahu at a small college in upstate New York. The narrator is the liberal economic historian Ruben Blum, who is assigned to take charge of Netanyahu’s campus visit, despite not knowing his work, because he is the only Jewish member of the faculty. Netanyahu unexpectedly brings his family along, and their encounter with Blum’s family is about equal parts farcical and disturbing. There are a few other plot points and some significant digressions, including two inserted letters and a fully delivered speech. But all of it comes together in a kind of playful package that I found more congenial—or differently congenial—than Cohen’s previous work.

In the afterword, we learn that the novel is based on real-life events told to Cohen by the literary scholar Harold Bloom, toward the end of Bloom’s life. Ruben Blum is a stand-in for Harold, the Blooms really hosted the Netanyahus, and so on. How much of the rest is true is unclear, for out of Bloom’s anecdote Cohen has crafted a story about two Jewish families half a century ago that is also an inquiry into the religious and political tenets upon which Netanyahu’s son—the famous Benjamin—would later reshape modern Israel. The result is a surprising hybrid, a learned and investigative novel that retains some of the feeling of a story shared by friends. Over and over, Cohen reconfigures the space between artifice and autobiography, between irony and earnestness, between what’s made up and what’s real, and how each of those modes offers its own understanding.

Cohen is the author of six novels, four story collections, and Attention, a collection of essays and criticism. I met him more than a decade ago, when I was the associate director of Dalkey Archive Press, and he and I hustled around New York promoting Witz. We became friends, and have grown as friends, mostly by talking about books we like. We also both spent part of our distant pasts working as musicians on cruise ships, and I would like to think that over the years we’ve quietly bonded over the fact that neither of us ever brings that up.

I interviewed Cohen by email in May and early June 2021. I told him ahead of time that I wanted to discuss Judaism as subject matter, the use of nonnarrative material in a narrative work, and varieties of comedy and irony, in that order.

INTERVIEWER

When Book of Numbers came out, in 2015, you told me you were done writing “Jewish books.” You’d written Witz, a very Jewish book, then Four New Messages was not a particularly Jewish book, nor was Book of Numbers. But later you wrote Moving Kings, an arguably very Jewish book, and now The Netanyahus, inarguably Jewish. Maybe this is a question about subject matter in general, the things we return to, but I’m interested in why you feel drawn back to this one.

COHEN

You know about the covering cherub? God dwelled in the holy of holies in the Temple in Jerusalem, and because God can’t be experienced directly—because direct experience of God will destroy a mortal—a cherub, or actually two cherubs in some accounts, was employed to hang out there, covering the presence of God with its wings. This was originally in Ezekiel, and though I’m sure I encountered it there at some point in my life, I only really noticed the cherub because of Harold Bloom, whose writing about it didn’t come from the Hebrew either, but from Milton and Blake. It was Milton and Blake who’d turned this cherub singular and associated it with Satan—the angel that covers God, that covers for God and, made overproud because of the privilege, falls. Bloom turned the covering cherub into the artist, the writer, who absorbs the divine light and filters it for the rest and, in doing so, suffers. Why am I bringing this up? Because it’s beautiful, in its cracked romantic way, but also because the process by which this beauty came to me is a model. Here is a figure from what I might call my tradition—Ezekiel, which I had to read at school—that hadn’t meant anything to me until, once Miltonized and Blaked, it Bloomed. This is typical, I think. We don’t know what pasts we have until other traditions absorb and filter them—in this case, a pair of English poets acting as covering cherubs for cherubic Harold. And now here I am, cherubing for you—telling you that after every book I finish, I declare myself “done.” (Mrs. Geller, my fifth-grade teacher of Bloomian proportions, used to remind me, “Turkey is done, a person is finished.”) After Four New Messages, I was “done” with technology, but then I wrote Book of Numbers. After Moving Kings, I was “done” with the Jews, but then I wrote The Netanyahus. At this point, I think declaring myself “done” means “I’ll have another.”

INTERVIEWER

Partly I ask because in the novel’s afterword, you introduce a sort of commentary on your own subject matter, in the form of an angry message you—“the author”—purportedly received from the real person one of the characters is based on. This person has nothing nice to say about the book in general, but her opinions on the subject matter are really scathing. “None of this Jewish crap still matters,” she writes. “No one reads books anymore and the Jews are either on the wrong side of history or irrelevant.” I wondered how much of this quote was real. Then I wondered how much was you. I can’t decide whether it dialectically undercuts what came before or takes the story to a fitting end.

COHEN

I’m not sure it’s an either-or. I think it’s fitting and undercutting both. I couldn’t write a book that doesn’t acknowledge the role of books in the world today. I could read one, of course, but I couldn’t write one, in the same way that I couldn’t take up blacksmithing or fletchery unselfconsciously. It’s like men who wear hats or grow beards—and I don’t mean Hasidim. They know what they’re doing, they know they’re being purposefully anachronistic—antiquarian—but the trick is to never admit it, the trick is to pretend it’s perfectly normal. I was never able to fake it like that. I know that what I’m doing is out of step and against the grain, and I think it’s important to acknowledge that—rather, I think it’s important to bring in the present moment in all its opposition, as a type of background against which the book’s drama can be read. I think my Blum character would understand this as a variety of double-bookkeeping: inviting into the book what was happening around me—what I wasn’t living—while I was busy writing and hoping that the invitation would be enough to compensate.

INTERVIEWER

In fact, you’ve invited all sorts of things into this novel. In his review of The Netanyahus for the Guardian, Leo Robson says a lot of laudatory things but also takes the book to task for your inclusion of nonnarrative materials—letters, a whole speech—that advance the book’s intellectual project but do less to drive the drama. We could talk about the long history of novels that include found forms or essayistic material, but the issue for me is simpler than that. I read those parts as neither impressive nor pretentious, but simply wonderful, a real pleasure. As someone who loves this kind of thing, I want to ask why you love this kind of thing.

COHEN

I don’t even know that I consider it a kind of thing. It’s not like I have a switch to flick that turns me intellectual, or emotional, or psychological. People talk about everything, they don’t just say what you want them to say or even what they want to say, and characters should be the same. In the deli today there was talk of UFOs, Biden’s hair, the history of Belarus, and the grill guy’s girlfriend problems. We bring ancient history into present conversation all the time, calling facts opinions and opinions facts, and when it comes to the nonverbal, to reading—isn’t the internet just one big dumb essay? Aren’t most people reading this big dumb essay all the time, knowing they’ll never finish?

INTERVIEWER

Okay, but there’s a choice here. Putting aside the question of what’s commercially viable, you didn’t accidentally include large nonnarrative sections in this book. Something about the subject, or something about the project as it initially came to you, or as it developed as you went, led you to decide that these forms—the letter, the speech—were a part of this particular book you were writing. And of course it would have been a choice not to use these forms as well. Why this choice, in this book, is what I want to know.

COHEN

Because you’re pushing, I’ll try. The novel of ideas—which is a phrase I hate and I’m going to blame you for not forcing on me, so that I have to force it on myself—is a tricky beast. Why it’s tricky is because of people. Novels can’t have an idea without a person and vice versa, of course, and though novels can contain countless ideas, the persons they contain come in two basic flavors, the author and the characters. Sure, an author can be a character, and a character can be an author, but I’m speaking about fundamentals. Who is the person expressing this idea, to whom and how and why? Newer novels are pretty antisocial—the person with the ideas is the author, wandering around somewhere that’s usually a city, thinking first-world thoughts in first person, talking to the reader and so essentially talking to themselves. Call this autofiction if you want, call this essayistic fiction, whatever—it’s antisocial, with a narrator who’s also the protagonist who’s also their own doctor, lawyer, surgeon, judge; the resident expert, through which all knowledge passes: if they didn’t read it, see it, hear it, or if they weren’t told about it, then it doesn’t exist, not for the reader. Now, contrast that to older novels like, say, The Man Without Qualities or, even better, The Magic Mountain. These are social novels. There isn’t any one person with all the ideas. Instead, the ideas are given to, spoken by, incarnated through the characters, who meet up in salons and sanatoriums and go on strolls through the snow, or to dances, or to interminable parties and meals, wearing out their quotation marks as they talk and talk and talk. Sometimes these characters converse in groups that chain—in the Musil, Ulrich and Arnheim, Ulrich and Diotima, Arnheim and Diotima—and sometimes they go back and forth dialectically—in the Mann, Settembrini, the so-called humanist, versus Naphta, the so-called radical—but mostly they do both and more, and if they’re Russian, they also perform monologues without interruption, a guest delivering six pages on metaphysics as the tea cools, and the host has switched to vodka and is already drunk.

Don’t worry—I’m getting to my point. A lot of my writing, some stuff published, a lot of stuff I’ll never publish, has to do with navigating these categories. What I like about the antisocial novel of ideas is the immediacy of first person—I like to read a mind thinking. And what I like about the social novel of ideas is other people besides the first person—I like difference and challenge and arguments with stakes. In everything I do, I’m trying to find ways of combining these categories, of juxtaposing them, blending them, mixing them up—in Four New Messages and Book of Numbers by faking emails, chats, edited and re-edited interview transcripts and drafts, and in The Netanyahus by forging letters of recommendation and lectures. My interest in this comes from my sense that this is how we live, merged with technology, enmeshed in other people’s text, even in self-generated authorless text, and unable to distinguish fact from fiction.

INTERVIEWER

What you talk about as social I think of as the subjectivity of all ideas, that ideas exist in the context of the people who think them and the moment in which they are thought, and to ignore this rootedness in experience is to pretend the world is more rational than it is. I am very skeptical—more skeptical than you, I think—of omniscience, of authority being taken too seriously, the authority of the author included. Which brings me to the question of irony. Fake forms are one thing—fake emails, fake letters—but fake ideas are another. The Netanyahus is much more theatrically fun than a Thomas Mann novel. It is a book full of comic scenes and lots of pathos, but since it is also full of ideas, the question is how the ideas are to be taken. Do ideas exist here as a part of the world, or as commentary on the world? Or both? Or sometimes one, sometimes the other?

COHEN

This is the question I’m always asking myself—about myself. And I’m not sure I have any answers that don’t collapse into comedy, which is exactly what happens in the book. The book is a fair portrayal only of my own inner argument: how far I’m willing to push these conflicting ideas within myself until I stop caring about the ideas and care more about the conflict; the contradictions become less interesting than the drama of contradiction, the compromising positions I put myself in by refusing to compromise and the humor inherent in backing myself into opposing corners. If, as you say, ideas exist in the context of the people who think them— I think we agree that this is what I mean by “social”—then the moments that most compel me are those when the context becomes untenable. Do you really lose self-respect or dignity when you refuse to budge? Of what use is integrity? And so on. In my perversity, I want to connect this not to political ideology but to “the writing life.” I love the freedom of writing, but then, is it a freedom? What have I sacrificed or lost for the privilege of this freedom? I have done some ridiculous, comical things in order to preserve my independence, or what I call my independence, as has almost every writer I’ve ever met. They’ve denied themselves pleasures, restrained their social urges, disdained or pretended to disdain their natural impulses toward material gain—toward money—all to pursue this phantom ideal, or all to pursue the time and conditions in which to purse this phantom ideal: total freedom on the page. And let me tell you, it’s hilarious. The whole situation is hilarious. And what’s more, it’s funny how many years it took me to recognize that—how many books it took me to recognize and be able to laugh at the unintended comedy I created out of a hard-line fidelity to an abstraction.

INTERVIEWER

Well if the dark comedy of the artist-self comes through in this novel, I suspect that is only because every kind of comedy comes through. Beyond the personal and dramatic and situational ironies, the comedy of errors and slapstick physicality, and the fact that the Netanyahu brothers could be the Three Stooges except that our knowledge of later world events makes their meathead behavior very scary—and beyond your verbal humor, which is always precise but is here pretty toned down—there is also the fact that your narrator is a classic schlemiel, and that tonally the book folds itself around him, making it actually, in my reading, the lightest of your books, in the sense of the gentlest. Your fiction is always comic, but your comedy is not often gentle. From whence the gentle? Is it because you’re telling someone else’s story? Because the book is written for a friend, in the memory of Harold Bloom?

COHEN

From whence the gentle, indeed—from Harold, or from Harold dying, and from so many of his generation dying, and probably from my own sense of getting older, and probably from this past year of plague and lockdown. I should also say that when you’re writing an acidic character, like Benzion Netanyahu, it’s hard to be acidic yourself. It’s better to moderate the general tone so that the character’s tone pokes through, cruder and sharper.

INTERVIEWER

I think I’m also saying I did not find much darkness in this book. But maybe what I should be saying is that I find darkness around the book, inescapably, in the looming shadow of the real-life future—the political rise of Benjamin Netanyahu and all that has meant for the world—that readers of Blum’s tale can’t help but hold in mind. The book’s title suggests it is about current events, but really, current events are the book’s unspoken truth. In this particular sense I might put The Netanyahus in a lineage with Georges Perec’s W or W. G. Sebald’s novels, books with absent centers, dark jokes for which history provides the punch line.

COHEN

That’s extremely generous because I know how much Perec means to you. I’m a student of his, too—interested if not in the strictly Oulipian nature of some of the work then in his principle of writing through lacunae, of purposefully excluding something from a book that might ultimately provide its key. These books tend to be tests, of the reader as much as of the culture itself—tests as to whether a culture has preserved within itself enough of what Van Wyck Brooks called “a usable past,” to enable the book’s comprehension. If you had only the most superficial idea of Nazi aesthetics—if you knew nothing at all of its cult of physicality—would you be able to understand W? If you knew nothing about German writing outside of Germany—in Austria, in Austria-Hungary, at the fringes of the German-speaking world—how could you hope to get at what Sebald is trying for, the assertion of an alternative German canon in the wake of et cetera? Their novels become trials of historical consciousness—do you remember enough to understand them?—as much as of present-day consciousness—do you see and hear the world around you clearly enough to make any connections between the world and the page? Books that omit context or explanation, books that refrain from acknowledging their analogies and allegories, books that withhold from the reader not in a spirit of exclusion but as a spiritual catalyst, books that, yes, summon up the cherub to cover their intentions—these are the books that provoke the reader, or at least provoke me as a reader, into seeking out the sources that are being denied, and in the process of that seeking I find myself situated within and vital to myriad continua. Or, to put it another way, this is how tradition works. This is what it means to live in a culture. Our books should be missing something, the finding of which makes us whole.

Martin Riker is the author of the novel Samuel Johnson’s Eternal Return, and his critical writing has appeared in publications including the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, and London Review of Books. He teaches at Washington University in St. Louis and co-runs, with Danielle Dutton, the feminist publisher Dorothy, a Publishing Project.

The Dogs of Plaza Almagro

“I’m interested in people’s specificity,” Hebe Uhart once remarked. The Argentine writer, who died in 2018, wrote with what Alejandra Costamagna terms “a philosophical position that arises from the ordinary.” Animals , a new collection of Uhart’s writing on creatures, critters, and companions, offers countless examples of her keen powers of observation. In the below excerpt, Uhart visits Plaza Almagro in Buenos Aires and interviews an eccentric collection of dog owners.

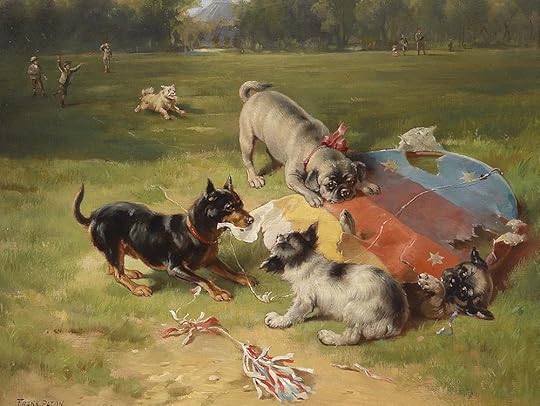

Frank Paton, A Found Toy, ca. 1878, oil on panel, 12 1/2 x 15 1/2″. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Here we are in winter, but the winter has made a mistake: it’s a spring day. The plaza is full of dogs, alone and accompanied; they’ve been set loose to enjoy the lovely day. Beside me sits a very circumspect lady with a dog on A+ behavior, not even sparing a look at the dogs in the pen as they bark wildly. She says to me:

“I’ve always protected animals. Back when I worked at a logistics warehouse I used to pick up all the ones that people dumped there.”

“Señora, what do they store at a logistics warehouse?”

“What does that matter? I have great memories of Torolo and Negrita, who’d made a hole in the concrete to hide their puppies, and Torolo used to slip away and come back later, always right at mealtime.”

When she says Torolo’s name, her voice makes it sound as though he were some famous singer.

A girl walks by with a slightly frenzied dog, and the lady says, “To have contact with a dog, you need to be balanced, and if the dog has a lot of energy, you keep yours low. That girl is adding to her dog’s energy.”

I am afraid I won’t pass the energy or aptitude test and go off to another bench, whistling softly to myself. There sits María Cristina, with her little dog Sharka. The dog is wearing a jacket on which it says PLAYBOY. María Cristina has something birdlike and nocturnal about her, with her lips in a shade of blue; her hair is golden, and she wears tinted glasses. She says:

“They gave her to me with the name Sharka. She came from a house with an abusive man, he’d beat the people and the dogs. My sister feeds her on pork chops and roast chicken, and we give her apples, that’s right. She’s the first dog I’ve ever had. At home we had canaries, finches, parakeets. In my family, we’re the kind to be around animals. In our house the birds would fly loose around the kitchen and then voluntarily get into their cages on their own.”

At one end of the plaza, a dog is running beside his owner, big blockheads the pair of them. The dog doesn’t know whether to play with the ball his owner is throwing, chase the pigeons, or go after the other dogs. The owner has a similar appearance, and, as though exaggerating his feeling of heat, he has on a sleeveless T-shirt; he seems to be sweating profusely, and he gives me the impression that he’s pursuing several careers or taking on various jobs but never sticking to any, always being drawn to something new. It’s like Torolo’s owner said: if our energies are overlapping, we don’t do well.

But it’s spring … On another bench sits Victoria, but she has to go. She says:

“He goes by Luis, but his real name is Luis Alberto, after Spinetta.”

Farther along sits Mariela, age somewhere around twenty. She seems as fragile as her clothing, which is in varying colors but looks as if it’s been washed with bleach or some corrosive liquid that has left all of the colors completely faded. For the same reason her skirt has a hole in it and is made of wool as fine as a strand of spittle.

“Is that your dog?”

“No, he’s my friend’s. I feel like he’s free inside the plaza.”

“And what’s his name?”

“Why should he have just one name? He goes by Teo or Cielo. No, I don’t want to own a dog, because pets are possessions—we decide when they can go out or how much they eat. I don’t want to enslave a living being. People even determine where they can sleep, they have to sleep wherever others decide.”

“And is there a reason for that austere outfit you’re wearing?”

“No, just for the ensemble of colors.”

“Ah. And where would you like to live?”

“In the country. I’d like to be a rural teacher, but I also like trades like carpentry, cooking … ”

“Would you keep animals in the country?”

“I’d like to have a dog without a leash, free. I’d let him be with other animals … ”

“And if your dog ran away, would you go looking for him?”

“I’d go looking for him, but I’m not convinced that he’d ever come back.”

I leave the realm of freedom and go over to the pen, which is the realm of barking. I go in and dogs of all sizes come over, leaping up on me; a dog walker energetically gets them in line, though I don’t know if Mariela would have approved of this exercising of authority. The walker’s name is Ramón, and he’s short on temper and few on words. He doesn’t feel like talking about the dogs; one is called Vicky, another Néstor. Named for Kirchner. (A girl I once asked for directions had named her dogs Fidel and Sandino.) Ramón says:

“I’ve always had a pepé, because purebred dogs are very choosy about their food.”

“What’s a pepé?”

“It’s a mutt,” he says, and pays me no more mind. He doesn’t feel like talking.

Walking along the gravel path, I come across Iván, from Corrientes, a chamamé singer. He knows a lot about dogs; his is Juanita. He says:

“She inherited the personality of a bloodhound from her father, and her mother comes from a bulldog and terrier mix. We’ve committed barbarities with animals by turning them into spectacles, like in bullfighting or cockfights.”

“Does your dog know when she’s misbehaving?”

“Yes, when she makes a mess, she gets onto the futon and doesn’t move. She’s five months old. Sometimes she’ll tear a pillowcase. And she resents it when I leave, like a cat. Yesterday I had to run an errand and it took a while, and when I came back, she gave me the cold shoulder.”

“What kind of thing do you sing?”

“I’m a chamamé musician, I write poetry; poetry seeks you out, just like dogs.”

I go back to the pen once more, and there’s a completely new line-up of dogs, and here’s Nicolás, a walker. He studied to be a park ranger in Buenos Aires; he’s from Lobos and in the future aspires to become a ranger in a protected area and study the fauna.

“What about dogs drew your attention when you started working?”

“My attention was drawn to the way they communicated with the posture of their bodies and the energy they transmit. The energy thing stands out. I have a friend who’s a walker, and the dog that leads her pack is the tiniest one. They express things with their bodies that we can’t. I think they’re more honest than we are.”

I don’t want to get myself into those complex depths, so I ask:

“Why do tiny dogs confront much larger dogs? Can’t they perceive their size?”

“Little dogs want to demonstrate their energy. I think they perceive energy more than size.”

“What do you remember from your first days as a dog walker?”

“The pack concept: I would end up being the alpha, but some packs have an alpha and a beta, that is, not just a first but also a second, though not all packs do. I come from Lobos, and I’ve seen a street dog curled up from the cold, and when another dog nearby growls, the curled up one will stretch out in a show of submission, all without physical contact. One thing that alarms lots of dogs is a hat with earflaps (if a man is wearing one). They can’t understand it, maybe because the ears are hidden, and they’re also disturbed by fluorescent colors, but they always look at what people have on their heads.”

“And what surprises them the most?”

“They’re shocked if someone hits them because that behavior doesn’t happen among them; they bite each other, they don’t hit.”

“And what’s your dog’s name?”

“My dog comes from Lobos. His name is Lennon.”

Then he tells me how European hares and starlings are threatening the local species, but that comes from his knowledge as a park ranger.

And I go off to take a look at someone on a bench; I’m puzzled by her mater dolorosa bearing. She has a puppy on her skirt who is very comfortable in that spot but wears a mournful and expectant expression.

“Is he yours?”

“No, he got lost here in the plaza. They say he belongs to some people who come here often.”

“What’s his name?”

“He doesn’t have a name. I don’t know.”

“So you aren’t going to keep him?”

“I wish I could, but I live in a hotel.”

And the girl comes to the plaza every day, in case the owner turns up.

—Translated from the Spanish by Robert Croll

Born in 1936 in the outskirts of Buenos Aires, Hebe Uhart is one of Argentina’s most celebrated modern writers, and a teacher to fiction writers like Alejandro Zambra, Mariana Enríquez, and Samanta Schweblin. Sam Carter wrote that her work “helped shape a generation of writers in Argentina as both a teacher and a writer, her influence both diffuse and impossible to ignore.” During her lifetime she published two novels, Camilo asciende (1987) and Mudanzas (1995). She is best known for her short stories and crónicas, where she explores the lives of ordinary characters in small Argentine towns. Her Collected Stories won the Buenos Aires Book Fair Prize (2010), and she received Argentina’s National Endowment of the Arts Prize (2015) for her body of work, as well as the Manuel Rojas Ibero-American Narrative Prize (2017).

Robert Croll is a writer, translator, musician, and artist originally from Asheville, North Carolina. He first came to translation during his undergraduate studies at Amherst College, where he focused particularly on the short fiction of Julio Cortázar. He has worked on texts by such authors as Gustavo Roldán, Javier Sinay, and Juan Carlos Onetti. Croll has also translated several of Ricardo Piglia’s works published by Restless Books.

Excerpted from Animals , by Hebe Uhart, translated from the Spanish by Robert Croll. Excerpted with the permission of Archipelago Books. Translation copyright © 2021 by Robert Croll.

Read Hebe Uhart’s short story “Coordination” (translated from the Spanish by Maureen Shaughnessy), which appeared in the Spring 2019 issue.

June 22, 2021

Redux: The Name like a Net in His Hands

Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

Hass teaching at St. Mary’s College, ca. 1977. Photo courtesy of the author.

This week at The Paris Review, we’re thinking about fatherhood and Father’s Day. Read on for Robert Hass’s Art of Poetry interview, Jonathan Escoffery’s short story “Under the Ackee Tree,” and Louise Erdrich’s poem “Birth.”

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, and poems, why not subscribe to The Paris Review? You’ll also get four new issues of the quarterly delivered straight to your door. Or, subscribe to our new bundle and receive Poets at Work for 25% off.

Robert Hass, The Art of Poetry No. 108

Issue no. 233 (Summer 2020)

When you’re taking care of small children, it’s the one time when you don’t have to ask what the meaning of it all is. The meaning is to get through the day without closing a car door on their fingers.

Cradle, 1762, mahogany and white pine, 30 1/2 x 27 1/2 x 46″. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Gift of Cecilia E. Brinckerhoff, 1924 (24.143).

Under the Ackee Tree

By Jonathan Escoffery

Issue no. 229 (Summer 2019)

You name your second son Trelawny to remind yourself of home. It long enough after you reach that you miss JA bad-bad. You miss walk down a road and pick Julie mango off street side. When you try pick Miami street-side mango, lady come out she house with rifle and shoot your belly and backside with BB. In the back of your Cutler Ridge town house, you start try grow mango tree and ackee tree with any seeds you come by, but no amount of water or fertilizer will get them to sprout.

Birth

By Louise Erdrich

Issue no. 111 (Summer 1989)

When they were wild

When they were not yet human

When they could have been anything,

I was on the other side ready with milk to lure them,

And their father, too, the name like a net in his hands.

If you enjoyed the above, don’t forget to subscribe! In addition to four print issues per year, you’ll also receive complete digital access to our sixty-eight years’ worth of archives. Or, subscribe to our new bundle and receive Poets at Work for 25% off.

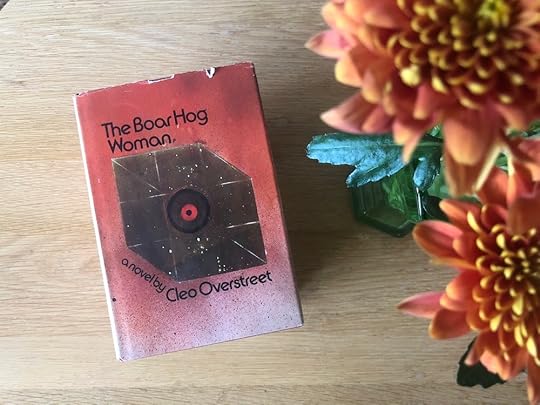

Re-Covered: Cleo Overstreet’s The Boar Hog Woman

In Re-Covered, Lucy Scholes exhumes the out-of-print and forgotten books that shouldn’t be.

Photo: Lucy Scholes.

In a literary landscape often obsessed with youth—whether it’s the buzz surrounding so-called hot new talent or those “30 under 30” and “best of young novelists” lists—stories of late-in-life success prove especially fascinating. I’m talking about writers like Penelope Fitzgerald, who didn’t publish her first book until she was in her late fifties, and won the Booker Prize at sixty-three. Or the British novelist Mary Wesley, who was seventy when the first of her ten best-selling novels for adults made it into print. Then we have the doyenne of them all, Diana Athill, who experienced unexpected literary celebrity in her nineties. As such, Cleo Overstreet’s debut novel, The Boar Hog Woman—which was published in 1972, when its author was fifty-seven years old—couldn’t help but catch my attention. David Henderson’s celebratory obituary for Overstreet, which ran in the Berkeley Barb on the occasion of her death, only three years later, in the summer of 1975, opens with a description of the deceased as “a grandmother and a novelist.” She “came to writing late in life,” Henderson explains, “but she had in her mind’s eye many stories to tell. She dedicated the last 12 years of her life to putting them down on paper.” Unlike Fitzgerald, Wesley, and Athill, however, Overstreet’s late-in-life career was sadly short and sweet. Henderson mentions her “unpublished novels,” referring to the most recent by name: Hurricane, the manuscript of which Overstreet’s close friend Ishmael Reed was apparently asked to edit for posthumous publication by Random House. Yet as far as I can see, this never actually happened, which means that The Boar Hog Woman remains the only one of Overstreet’s books to have made it into print.

Of all the books and authors I’ve written about thus far in this column, The Boar Hog Woman and Cleo Overstreet have to be those about which and whom I’ve uncovered the least information. Bar the brief author bio on the dust jacket of my secondhand copy of The Boar Hog Woman, Henderson’s obituary is the only account of Overstreet’s life that I’ve found. There’s a short Kirkus review of the novel that describes it as “weirdly engrossing,” and a significantly longer write-up—a rave, by the writer and film scholar Clyde Taylor—in the June 1974 edition of Black World. But what I learned from these pieces, combined with the novel’s publication date, was enough to intrigue me. Two of the most exciting and experimental female-authored works to emerge from the Black Arts Movement were written during the early seventies—Fran Ross’s Oreo (1974) and Carlene Hatcher Polite’s Sister X and the Victims of Foul Play (1975)—so I was keen to see how The Boar Hog Woman compared.

Short answer: although not quite up there with Oreo, Overstreet’s entertaining and often moving account of the comings and goings of a close-knit Black community in mid-’60s Oakland, California, more than holds its own. But don’t just take my word for it. “Cleo Overstreet has done to narrative what Sterling Brown and Langston Hughes did to Negro poetry, put it on a solid Black footing by tapping the folkroot,” Taylor writes. “She gives a hip to the creaky machinery of the novel—point of view, stream of consciousness, the objectivity of the narrator, the incessant analysis of motivation, jabber jabber—then she leaves it hanging out to rust. She has up-fingered its tradition more successfully than any Black writer in North America.”

*

Overstreet’s garrulous narrator—a woman of late middle age who runs a beauty salon (as the author herself did) but whose name we never learn—tells long-winded tales about her friends and neighbors, including the titular Boar Hog Woman, who runs the barbershop where the local men like to hang out, and whom the narrator’s own husband, Hars, has recently left her for. The Kirkus review sums it up well: the novel is “about nothing so much as its own energy, as it jumps dazzlingly from event to event, casually skipping years here and there in total indifference to causality, psychology, and symbolism—all the conventional devices that over-imbue our ordinary novels with ‘meaning.’ ” The narrator certainly doesn’t mince words when it comes to her villainous rival—or any other character, come to think about it—thus, reading the novel is like listening to a gossipy friend. It’s easy to imagine her accompanying side-eye, raised eyebrows, and pursed lips. One of the best jokes here is how often the narrator complains about everyone else’s blathering and tattling, while she’s clearly the worst of the lot! Fictional shenanigans aside—a funeral that’s a hotbed of fainting and fighting, an old man whose attempts to join the gang at the barbershop are thwarted by bands of flower children, even a search for buried treasure—Overstreet paints a portrait of the kind of community that she clearly knows intimately, and she takes as her subjects the universal themes of love, loss, and ordinary, everyday jealousies and betrayals.

So far, so authentic, but add to this an undercurrent of something decidedly strange. Were it not for the novel’s prologue—in which a Black man named Amos Sandblack gets a job rearing boar hogs in the middle of the Nevada desert, an experiment during which only one animal is ever born, a runt, which Amos’s wife treats like a baby until it disappears one day after somehow having transformed into what the couple take, at a distance, to be “a little black girl with her clothes almost torn off”—we’d be forgiven for assuming that the jealous narrator is simply painting her adversary in a less than flattering light. But something much weirder is going on. “The Boar Hog Woman is a woman who is a hog which is a male hog,” reads the opening line of the blurb on the dust jacket, which is about as clear as it gets! “Science fiction? Surrealism? Poetic license gone mad in prose?” the blurb continues. None of the above, we’re told; rather, this is a novel that should be read as “contemporary myth, touching us where myth ought to touch—at the heart of our need to understand the forces molding our destinies.”

And this is exactly what Overstreet does so brilliantly. “The Boar Hog Woman is not a novel,” writes Taylor; “it’s a story, a long tale, a mythic narrative, an East Oakland shaggy-dog story.” Beneath its more diverting, diaphanous exterior lies what Henderson describes as “an intensely moving tale of a woman who loses her man in middle-age to another woman, subsequently seeing the friends they had shared drifting away and sometimes dying.” The narrator watches in dismay as the men in the neighborhood flock like moths to the Boar Hog Woman’s flame. It doesn’t matter that she’s no great beauty, and it’s not just Hars whom she entices away from his wife. The Boar Hog Woman employs a staff of “aged whores,” well-practiced at handling their clientele. The men might all be so old they “could not have raised a hard if their life depended on it,” but in the company of these women, they behave as though they’re frisky young studs. And although distinctly unimpressed by these drooling lovesick “fools,” the narrator can’t help pining after her lost husband. Such is life, though; his abandonment is presented as a horrible inevitability. She’s not the first wife to be deserted, and she won’t be the last. “The life of a wife is like the life of a maid,” she reports, half in anger, half in resignation. “She can work the hell out of herself and try to make something comfortable or make ends meet. And that son-of-a-bitch will go and find his old worn-out whore and put her in front of his wife.”

Not that this is a world without loyalty. The community is tethered together in large part by the steadfastness of friends, not to mention the kindness of strangers. In a particularly affecting episode, two children who embark on a long and perilous journey across the city one rainy night to visit their father’s grave are thankfully taken under the wing of a passing benevolent truck driver. Then there’s the man who usually keeps an eye out for them—their dead father’s best friend—no matter how rude their widowed mother is to him. Or take the narrator’s relationship with her old pal Katie Blue, a woman who “would do you a big favor and in the same breath would cut your throat with her tongue.” Underneath this caustic exterior, the women are still there for each other.

In spite of the rather pathetic predictability of the old men’s conduct, there’s more than an air of melancholy to their antics. Overstreet encourages us to laugh at them, but that doesn’t stop her from also presenting them as victims of circumstances and structures beyond their control: “All of these men had hard jobs, and they worked hard on those jobs. They would work all the week working like a mule and misusing their home and thinking that they were enjoying themselves. This was a slow way of committing suicide by working all of the week and sitting up all of the weekends and drinking rotgut whiskey.” As Taylor points out, although not “de Text of revolutionary Black consciousness,” it is a novel “brushed by that awareness.” As Overstreet writes:

The system for over four hundred years had had its eyes focused on the black man. This was worked on him and his manhood, trying to stand up like a man. He has all the qualities of a man, but the system won’t let him perform like a man … The white man uses psychology on the black man in every way. He might call him “Boy,” that is the old way of working on the black man’s mind. Now this theory has gotten old, now he has to think in terms of some other way of exploiting the black man.

Systemic racism is nothing new, of course, but the nuance of Overstreet’s observations—the way she probes the intersections of race and gender to explore the emasculation of Black men and the knock-on effect this has on the way they treat the Black women in their lives—seems pretty advanced for the time of the book’s publication.

As a case in point, perhaps the most stirring, not to mention shocking, episode here is when one of the gang, Ben, gets drunk with Hars and confesses—for the first time ever, it seems—that beginning when he was a child and on through his adolescence, he was sexually abused by a significantly older white woman. As he tells his story, we learn that it wasn’t just that he couldn’t say no; he had to contend with the knowledge that if his abuser’s white husband ever walked in on them, she would have “hollered raped, and they would have killed me and she would have stood in line watching it.” It was a good thing war broke out when it did, Ben says, drawing his tale to a close. “Man, you are talking crazy,” Hars tells him, confused as to how his friend could welcome something that amounted to so much death. “But look at all the lives that is lost in the black race in those Mississippi delta and hills, and nobody do anything about it,” Ben counters. Earlier in the novel a joke is made of the fact that Ben can’t tell the difference between the Civil War and World War II, but no one’s laughing now: “In my book World War Two was the Civil War,” he explains soberly, “because where I lived it was still slavery, and many of those colored people was able to get away from their slave masters and they had a job waiting for them and a place to stay. Roosevelt did more for the colored people that way than Abraham did; at least he did what he promised them.”

*

Since she herself was born, raised, and married in rural Mississippi, when her characters talk about pre–World War II life in the South, we can only assume Overstreet’s writing about a world she knew well. After living in Georgia, Washington, Oregon, and New York, she and her family settled in Berkeley in the early forties. She attended a variety of colleges, including real estate school, mortuary school, and beautician school. She also raised three children—Harry Lee Overstreet, a Berkeley-based architect and politician; the abstract expressionist artist Joe Overstreet, who lived and worked in New York for most of his life; and her daughter, Laverta O. Allen, who worked in education—and, at the time of The Boar Hog Woman’s publication, had eleven grandchildren. Overstreet was active in the civil rights movement from the early sixties to the time of her death, and Henderson—who knew her personally—describes her as “one of the most dynamic women I have ever met,” a combination of “ancient griot spirit of wisdom mixed with contemporary Americana.” This is something that comes across in her work: Taylor describes The Boar Hog Woman as “ooz[ing] the intuitive, self-comfortable Blackness of a holy-roller lady, without the self-consciousness of ideology.”

Why The Boar Hog Woman isn’t better known today, I’m really not sure. According to Henderson, Overstreet had more than a handful of notable admirers: Taylor and Reed, of course, but also the well-known feminist Kate Millett, the activist lawyer Flo Kennedy, as well as other academics in the Berkeley area. Taylor rates the novel “in the front ranks of Black fiction … alongside of Ellison, Wright, Toni Morrison, Reed, Gaines, Himes, Toomer, Kelley, McKay, way up there.” Henderson also argues that Overstreet’s brilliant depiction of older women (and men) should have seen her more widely championed by the women’s liberation movement: “She used an oral poetic tonality that gave her reader full entry into the main character’s heart and mind. No, love is just not for teenagers, nor the jokes about the old folks doing it in the old folks home, love is eternal and the emotions Cleo Overstreet’s protagonist feels over lost love is universal, is anyone’s heartbreak.” When he hails her use of language—which he describes as “straight out of Mississippi, via Africa, she is not as eloquent as Doris Lessing or as poetic as Anais Nin, but if you go with just the power and energy of the works, then Cleo Overstreet ranks with the highest of the highest”—he’s echoing Taylor’s memorable summation of the novel: “It might hit you like white lightning when your taste runs to Scotch, but you have to give it dues for undiluted strength and character.” To think that this was just the beginning of what she could have gone on to write feels like such a cruelly snatched-away opportunity—stolen from both Overstreet herself, since she’d waited so long to dedicate herself to her writing, and from us, her readers. Whatever string of circumstances arose that contributed to The Boar Hog Woman fading away from view, Overstreet’s tragically early death undoubtedly plays a large part. In the three years between its publication and her passing, the novel went from thrilling debut to poignant swan song.

Lucy Scholes is a critic who lives in London. She writes for the NYR Daily, the Financial Times, The New York Times Book Review, and Literary Hub, among other publications. Read earlier installments of Re-Covered.

June 21, 2021

Remembering Janet Malcolm

Janet Malcolm and Katie Roiphe in conversation at NYU, 2012. Photo courtesy of Roiphe.

In one of my last email exchanges with Janet Malcolm, in one of the darkest parts of the pandemic, she wrote to me, “I can only try to imagine the hard time you and the children are having. How can you not be stalled on writing? I wish there was something I could do to help.” Her response warmed me, elevating my state of general stagnancy into something almost socially acceptable. The idea of her in my house, helping with my son’s online schooling—his teacher was reading out “rat facts” during his daily forty-five minutes of Zoom—was so incongruous that it made me laugh.

Before I met Janet, she was the only living writer who terrified me, because I loved her work so much. I had devoured The Silent Woman in graduate school, and then read everything else. I was in awe of her brutal precision, her sharp inquiries into the production of stories, her moral wrangling with journalism and biography. H. G. Wells once said that Rebecca West wrote like God, and I always felt a little like that about Janet Malcolm.

The Paris Review had tried to interview her twice, but she had pulled out of the process both times. She was not comfortable being recorded by an interviewer in a ranging conversation, and only agreed to my interview if we conducted most of our exchange in writing. We wrote our questions and answers back and forth over months. We came to love the nineteenth-century, evening-post rhythms of our exchange, and at some point in the course of our emails we became friends. I noticed that she had none of the usual writer’s vanity, exhibitionism, need for attention. She constantly deflected the conversation away from anything too personal. She was more interested in craft, in the exchange of ideas. As our interview went into proofs, Janet noticed that my questions and observations had been radically whittled down in the edit. She objected. “You become characterless,” she wrote to me. She threatened to pull the interview once again. There was no doubt in anyone’s mind that she was serious.

In the interview, I asked her to talk, among other things, about the conflicts between motherhood and work. “I have indeed felt the pull between the ruthlessness of the writer and the instincts of the mother,” she said. “But this may be too deep a subject for an e-mail exchange on the art of nonfiction. Probably the place to discuss our struggles with the art of mothering is a dark bar.” I never got to have that conversation with her, or to go to a dark bar. Instead, we’d have lunch at Choshi, the now-closed sushi restaurant near her house, where we talked about my messy life (never hers, despite my best efforts) and writing and work. She gave me tips on my hopeless interviewing style. “You don’t have to be friends with everyone you interview!” she would say. “If someone suggests going off the record, tell them you don’t want to hear it. They’ll probably talk to you anyway.”

She was known for her sharp eye, her gorgeous sentences, her frightening brilliance, her astonishing reporting, her fierce intellectual presence, her ability to cut through people’s pretensions with a single phrase, but she was also generous, warm, supportive, and kind. Months after our interview, she offered to participate in an afternoon of live Paris Review interviews at NYU. She dreaded public conversations, but she knew that I was embroiled in a fraught tenure process, and that the conversation might help make me seem valuable to the university and its endless committees. I had somehow managed to corral Gay Talese and Lorrie Moore into the evening as well, and the idea was that they, too, would be informally interviewed onstage. Janet, set against the dangerous spontaneity of casual conversation, insisted that she and I read our interview like a play. There was something sublime and deranged about this arrangement, but there was also an elegance to her solution: she had found a way to be both present and not, at the same time. We sat there and read our parts.

Katie Roiphe is the author, most recently, of The Power Notebooks, and the director of the Cultural Reporting and Criticism program at New York University.

Read Janet Malcolm’s Art of Nonfiction interview, which was conducted by Roiphe.

June 18, 2021

Celebrating Juneteenth in Galveston

Jas. I. Campbell, Historic American Buildings Survey: Ashton Villa, Photograph, 1934. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

The long-held myth goes that on June 19, 1865, Union general Gordon Granger stood on the balcony of Ashton Villa in Galveston, Texas, and read the order that announced the end of slavery. Though no contemporaneous evidence exists to specifically support the claim, the story of General Granger reading from the balcony embedded itself into local folklore. On this day each year, as part of Galveston’s Juneteenth program, a reenactor from the Sons of Union Veterans reads the proclamation at Ashton Villa while an audience looks on. It is an annual moment that has taken a myth and turned it into tradition.

Galveston is a small island that sits off the coast of Southeast Texas, and in years past this event has taken place outside. But given the summer heat, the island’s humidity, and the average age of the attendees, the organizers moved the event inside. A man named Stephen Duncan, dressed as General Granger, stood at that base of the stairwell, with other men dressed as Union soldiers on either side of him. Stephen looked down at the parchment, appraising the words as if he had never seen them before. He looked back down at the crowd, who was looking back up at him. He cleared his throat, approached the microphone, and lifted the yellowed parchment to eye level.

“The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor. The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.”

All slaves are free. The four words circled the room like birds who had been separated from their flock. I watched people’s faces as Stephen said these words. Some closed their eyes. Some were physically shaking. Some clasped hands with the person next to them. Some simply smiled, soaking in the words that their ancestors may have heard more than a century and a half ago.

Being in this place, standing on the same small island where the freedom of a quarter million people was proclaimed, I felt the history pulse through my body.

General Granger and his forces arrived in Galveston more than two years after Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation and more than two months after Robert E. Lee’s famous surrender. A document that is widely misunderstood, Lincoln’s proclamation was a military strategy with multiple aims. It prevented European countries from supporting the Confederacy by framing the war in moral terms and making it explicitly about slavery, something Lincoln had previously backed away from. As a result, France and Britain, which had contemplated supporting the Confederacy, ultimately refused to do so because of each country’s antislavery positions. The proclamation allowed the Union Army to recruit Black soldiers (nearly two hundred thousand would fight for the Union Army by the war’s end), and it also threatened to disrupt the South’s social order, which depended on the work and caste position of enslaved people.

The Emancipation Proclamation, some forget, was not the sweeping, all-encompassing document that it is often remembered as. It applied only to the eleven Confederate states and did not include the border states that had remained loyal to the U.S., where it was still legal to own enslaved people. Despite the order of the proclamation, Texas was one of the Confederate states that ignored what it demanded. And even though many enslaved people escaped behind Union lines and enlisted in the Federal Army themselves, enslavers throughout the Confederacy continued to hold Black people in bondage throughout the rest of the war. General Lee surrendered on April 9, 1865, in Appomattox County, Virginia, effectively signaling that the Confederacy had lost the war, but many enslavers in Texas did not share this news with their human property. It was on June 19, 1865, soon after arriving in Galveston, that Granger issued the announcement, known as General Order Number 3, that all slaves were free and word began to spread throughout Texas, from plantation to plantation, farmstead to farmstead, person to person.

A ninety-two-year-old formerly enslaved man named Felix Haywood recalled with nostalgic jubilation what that day meant to him and so many others: “The end of the war, it come jus’ like that—like you snap your fingers … Hallelujah broke out … Soldiers, all of a sudden, was everywhere—comin’ in bunches, crossin’ and walkin’ and ridin’. Everyone was a-singin’. We was all walkin’ on golden clouds … We was free. Just like that we was free.”

*

The air at Ashton Villa smelled of salt and heat. The street hummed with light traffic. The residence’s coral-red brick facade shimmered under the summer sun. Each of the three stories of the Victorian-style house held tall white-trimmed windows with forest-green shutters that opened on either side. A cast-iron veranda extended its shadow over the walkway leading to the front door.

Completed in 1859, the villa had served as regional headquarters for both the Union and the Confederate armies during the Civil War, moving back and forth between each of them while the battles that would determine the future of Texas, and of the country, were won and lost. The home was built, in large part, by the labor of enslaved people.

I walked inside and was grateful for the cool air. In the back of the old residence was a large, bright room. I walked in and sat down at one of the two dozen round tables laid out across the long rectangular space, each blanketed by a large white cloth with its trim overhanging the edges. The ceiling was so high it looked like it was running from the people below. A large chandelier was suspended from the middle of the room, its glass ornamentation hanging from curved silver arms, each translucent crystal glimmering under the canopy of light. A man at the front of the room was playing the piano, his fingers gliding along the keys in a series of chords, a preview of each song he planned to share during the event.

The room began to fill with a slow trickle, followed by a gush, of limbs and smiles as the start of the program drew near. As friends, family, and neighbors saw each other, they moved enthusiastically toward the tables, hugging, shaking hands, and squealing with delight at each small reunion. Some wore Juneteenth T-shirts with Pan-African colors embedded in the designs; some were dressed in dashikis and colorful beads. Many looked as if they were on their way to a picnic. The vast majority of the people in the room were Black, though a range of races and complexions were scattered throughout.

The scene was similar to the beginnings of the Black church services I knew as a child. It was a scene of fellowship, a sanctuary less reliant on the building it sits in than on the community it has built. Ashton Villa was brewing with the anticipation of revival.

This was the fortieth anniversary of Al Edwards Sr.’s Juneteenth prayer breakfast. The event has been held annually since the Texas House Bill 1016 passed in 1979, a piece of legislation championed by state legislator Al Edwards Sr., that made Juneteenth an official state holiday.

*

Reverend Lewis Simpson Jr., pastor of Saint John Missionary Baptist Church, came up to the podium and led the group in prayer. Leaning on his cane, nodding his head as if it were being lifted and released by an invisible string above him, he outlined the parallels between God’s freeing of the Israelites and the freedom achieved by enslaved Black people in America, a parallel that had long been made by Black ministers both during and after slavery.

“You led us out of captivity, and for that, Father, all of us”—he lifted his head—“just say thank you.”

I looked around to see every person’s head bowed in prayer, as devotional ad-libs cascaded across the room.

After Reverend Simpson stepped down, the pianist, who had been playing lightly in the background of the prayer, seamlessly transitioned into the beginning of the melody for “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” also known as the Black National Anthem.

Originally written as a poem by James Weldon Johnson to celebrate the birthday of the late president Abraham Lincoln, the poem evolved into a song, and the song evolved into something much larger than a tribute to any singular figure. Scholar Imani Perry, in her book about the origins of the song, May We Forever Stand, writes that it “was a lament and encomium to the story and struggle of black people” that ultimately became “a definitive part of ritual practices in schools and churches and civic gatherings.”

Without anyone having to ask, everyone in the room stood up. Some held pieces of paper with the song’s lyrics, but the majority stood simply with their eyes shut and their hands clasped. They did not need to read the words. Their bodies swayed and their lips moved to a hymn that had long been imprinted in their memories.

I half sang and half looked around the room, observing the way people’s mouths moved over the words, how the vowels at the center of each lyric stretched out and hung like the laundry on a warm day. Around me was a tapestry of sunlight and song, pain and catharsis moving through the air. As I listened to people sing, I imagined the words floating above us, my eyes tracing the curve of each invisible piece of language, while the chords from the piano echoed throughout the room. I felt almost as if I should reach up and grab the words and place them in my pocket, in an effort to carry this moment with me once it came to an end.

When we reached the second verse, I felt something different come over the crowd, and felt something different come over me:

We have come over a way that with tears has been watered,

We have come, treading our path through the blood of the slaughtered,

Out from the gloomy past,

Till now we stand at last

Where the white gleam of our bright star is cast.

The crowd had turned into a congregation. My own lips, after an initial wariness, curled around each slice of song and found a home there. I had sung the Black National Anthem countless times—in churches, in schools, at my own dinner table—but hearing the harmony of those words reverberate around me in this place, on this day, moved me in a way I had not experienced before.

When the crowd sang “We have come over a way that with tears has been watered, / We have come, treading our path through the blood of the slaughtered,” I thought of how 154 years ago such a lyric would not have been an abstraction, the blood would not have been metaphoric. I felt as if there was something that had been clenched inside me I was now able to release. I exhaled, able to breathe in a new way.

Clint Smith is a staff writer at The Atlantic and the author of the poetry collection Counting Descent. The book won the 2017 Literary Award for Best Poetry Book from the Black Caucus of the American Library Association and was a finalist for an NAACP Image Award. He has received fellowships from New America, the Emerson Collective, the Art For Justice Fund, Cave Canem, and the National Science Foundation. His writing has been published in The New Yorker, The New York Times Magazine, Poetry Magazine, The Paris Review, and elsewhere. Born and raised in New Orleans, he received his B.A. in English from Davidson College and his Ph.D. in Education from Harvard University.

From the book How the Word is Passed by Clint Smith. Copyright © 2021 by Clint Smith. Reprinted by permission of Little, Brown and Company, New York, NY. All rights reserved.

June 17, 2021

Worldbending

In Akwaeke Emezi’s new book, Dear Senthuran: A Black Spirit Memoir, the writer traces their experience as an ọgbanje, an Igbo term that refers to a spirit born into a human body, through letters to friends, family, and lovers. In the below excerpt Emezi describes trying to find community within their M.F.A. program and their discovery that working fearlessly could be a form of worldbending.

Guy Rose, The Blue House, c. 1910. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Dear Kathleen,

Sometimes, you remember me better than I remember myself. I think that’s important in a friendship—to hold reflections of people for them, be a mirror when they start fading in their own eyes. I hope I do the same thing for you, too. I can’t wait for you to get here for Christmas; I know Germany has been hard on you this fall.

The last time we texted, you wrote, I need you and our time this break. I know what you mean. The world can be a grit that sands away at us, and love can be a shelter from that. If this godhouse in the swamp is a wing, then I imagine you arriving and joining me underneath it, where we make syrup with the chocolate habaneros from my garden and sit out on the haint-blue porch. I wish the house was bigger, five or seven bedrooms instead of three, so I could fit more of us in here. We are safer with each other. We see the worlds we’re trying to make, and we lend our power to each other’s spells. I was steaming baos in my kitchen today and I got so excited to show you this house, my house. Just a year ago, you came down to the swamp for Christmas and we stayed in that sublet and cooked fish fresh from the lake. And now I have this house, this land, and the shock of what I made happen still makes me reel when I look at it fully. You think I’d be used to it by now, the way I can make things come true, but every year it expands. Every year I make bigger and bigger things happen—and it’s not just me, obviously. It’s my chi and the deityparents and God and so on, but I have to say yes first and I have to do the work and I can’t believe it works.

You know how people are so in awe of Octavia Butler’s journal, the way she wrote down what she wanted with her books? I think it’s because written worldbending resonates so widely. I’ve been curious about what other languages one can worldbend in, though, languages of manifestation, if you like. Writing things down, using images to make vision boards, speaking things aloud—these are all spells. Most of my own worldbending is very action-based: I move as if the future I want is absolutely assured, making choices and spending money like a prophet—buying clothes for galas before I was ever invited to one, paintings for a bungalow I had no idea how I’d ever afford, the pink faux fur for my book launch before I even had a book deal, shit like that. And see, this is why I love you, because you never thought it was impossible; you dream even bigger for me than I do for myself. I ran the potential outfits for make-believe events by you and you took them all seriously. When the noise started happening for my book, I told you I was shocked, and you immediately called me a liar. “You said this would happen,” you reminded me. “You’re not surprised! Don’t act surprised.”

Man, I’m supposed to act surprised, though. We all know the thing of how Black artists are meant to be grateful and humble, but when I started entering literary circles as a baby writer, there was all this culture I knew nothing about. That M.F.A. program I was in, when you came to help me after my surgery, it was full of writers who were afraid. I don’t mean that in a bad way; there’s nothing wrong with fear. I just wasn’t afraid of the same things. I wasn’t worried about failing, because if I failed my life would be just the same as it already was, so there was nothing to be scared of. If I succeeded, however, everything would change, and that was terrifying.