The Paris Review's Blog, page 109

July 2, 2021

Staff Picks: Cornets, Collections, and Corn Tempura

James Brandon Lewis. Photo: Diane Allford.

James Brandon Lewis has quietly become a legend in edgy jazz circles over the past decade, picking up where Albert Ayler and David S. Ware left off under the sign of John Coltrane and adding his own highly lyrical sense of song into the mix. I hadn’t known about him, but the recent buzz (including this New York Times profile) tipped me off, and I’m deeply grateful. Lewis’s compositions and solos always feel like they are about something, even if that something is veiled or just beyond the reach of words. Lewis’s amazing new record, Jesup Wagon—his first with his Red Lily Quintet—takes inspiration from the work and life of the Renaissance man George Washington Carver. The music is alternately beautiful and jarring, anxious and clear-eyed. I especially enjoy the musical conversation between Lewis and the cornet player Kirk Knuffke. And I’m absolutely in love with the drumming of Chad Taylor, whose sound is paradoxically anxious and steady. William Parker on bass and Chris Hoffman on cello hold down the low end and add plenty of flourishes and surprises. This is a not-unfriendly way into the challenging fringe of the jazz universe, and after a few listens, Jesup Wagon becomes a good friend indeed, a record equally suited to headbanging and meditation. —Craig Morgan Teicher

The poems found in Moon Bo Young’s collection Pillar of Books, translated from the Korean by Hedgie Choi and published by Black Ocean, are strange and discursive, off-kilter in both their humor and their phrasing. “My lover forgot their brain when they left,” begins “Brain and Me.” “I could blend it and drink it, I guess.” Meanwhile, in “__________*,” the narrator has a relationship with Kafka’s The Trial that goes far beyond the usual readerly obsession: “In Kafka’s The Trial there’s actually a sentence that goes ‘__________*’ The only person who’s seen that sentence is me.” Multiple poems feature the characters of Antoine, Gemelle, and Strains, three young poets who move through life in a series of danger-tinged pratfalls (a few lines from “Collaboration Poem,” where the trio first appears: “This is how art forms change, / says the poet at the podium, / The readers and the poet go bananas and / they become banana-rich”). “Moon Bo Young is both super-funny and super-serious,” Choi explains in her translator’s note. “There’s levity and surrealism, but there’s also God and Death.” Pillar of Books is a collection that wields both modes effectively, frequently employing them in the space of a poem, a stanza, a line. —Rhian Sasseen

Brandon Taylor. Photo: Bill Adams.

It is an anomaly, I think, that the entirety of a story collection be a page-turner, but I count Brandon Taylor’s Filthy Animals among those rare gems that accomplish such a feat. Taylor’s new book kept me reading not just within but between stories as I eagerly devoured one and jumped right into the next. The collection is described as a “portrait of young adults enmeshed in desire and violence,” and this—the knife’s edge between desire and violence, their sometimes (or perhaps frequent) interplay—makes for an incredibly compelling through-line cutting down the center of the book. Three characters in particular weave in and out of the collection: a graduate student named Lionel, who’s on medical leave, and a romantic couple, the dancers Sophie and Charles. After he sleeps with Charles, Lionel finds himself a pawn in a strange power game between the couple; while Lionel and Charles are physically intimate, it is Sophie’s role in the game, all manipulation and control and a sort of social sadism, that makes for some of the most taut and compelling moments in the book. These stories depict the various harms that can accompany intimacy, but they also paint a beautiful portrait of people seeking genuine connection, whether it be with lovers, friends, or family members. Rarely is a collection so tonally cohesive across the board. All in all, Filthy Animals is fantastic—unsettling in a very human way, fully realized, and a major success. —Mira Braneck

If you haven’t read J. Robert Lennon, head on over to the Review’s archive and check out his work in the Spring 2010 issue. Really, follow that link. It’s worth the detour. If you’re jumping back in after reading “The Impossible Man,” you’ll know how a seemingly understandable situation can, in Lennon’s hands, spiral into a scenario of nightmarish complexity. The stories—mostly what we might call flash fictions—in his latest collection, Let Me Think, operate on similar premises. Appearing as flippant or even absurdist dialogues between a married couple, the “Marriage” stories are particularly deceptive in their simplicity, serving as thematic waypoints throughout the book and illustrating how two people may share everything from their home to their native tongue yet still struggle to express the simplest of life’s truths to each other: “Then our marriage is a lie, she says. No, he says. Our marriage is a mystery.” Many of these pieces are about the difficulties of communication, as suggested by the title and the clever cover art—seventy-one numbered points, which, after the stories in this collection, have been carefully placed in service of a cohesive vision. I’m sure you’ll want to connect the dots for yourself. That is, after all, the name of the game. —Christopher Notarnicola

Hirokazu Kore-eda’s film Still Walking takes place in a home of captivating and understated elegance. It belongs to the mother and father of Ryoto, a brooding art restorer who has brought his new wife and stepson for a summer weekend visit. His sister teases him in the kitchen over the sizzle and pop of frying corn tempura, and the rhythms of the film flow around meals taken in a dining room that opens out to a lush back garden. As Still Walking progresses, it becomes harder and harder to comprehend the layout of the house: new scenes reveal rooms and halls that seem disjointed. In the same way, a story that begins as a simple portrait of a family slowly reveals the intricate relationships between characters, and how a past tragedy has left an open wound in each. But Kore-eda’s eye is for small details, and his ear is for humor, crafting all of this with a lightness that counterintuitively lends the movie its gravitas. —Lauren Kane

Still from Hirokazu Kore-eda’s Still Walking, 2008. Courtesy of the Criterion Collection.

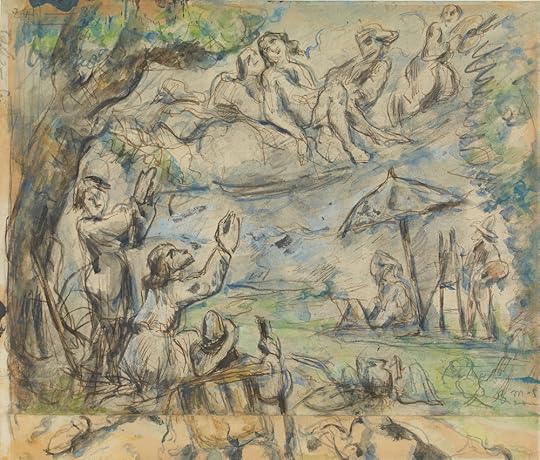

Cézanne on Paper

Although he’s best known for his lush, technically miraculous oil paintings, Paul Cézanne held his sketchbook near and dear. In a 1904 letter to the Fauvist painter Charles Camoin, Cézanne wrote, “Drawing is merely the configuration of what you see.” Thousands of his works on paper have survived. More than two hundred fifty of these rarely shown pieces form the basis of “Cézanne Drawing,” which will be on view at the Museum of Modern Art through September 25. A selection of images from the show appears below.

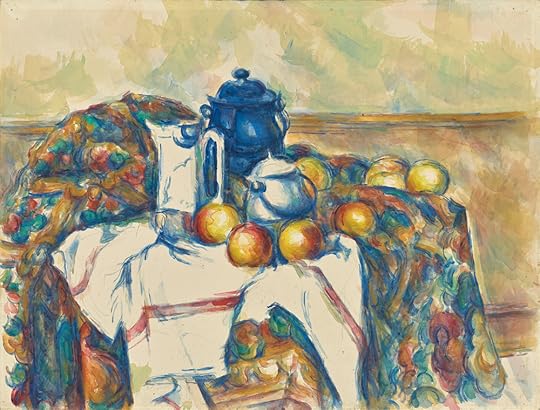

Paul Cézanne, Still Life with Blue Pot, 1900–06, pencil and watercolor on paper, 19 × 24 7/8″. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

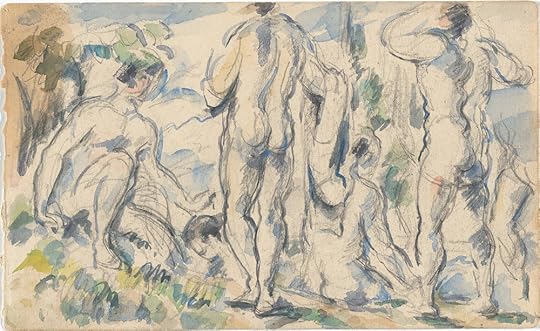

Paul Cézanne, Bathers (Baigneurs), 1885–90, watercolor and pencil on wove paper, 5 × 8 1/8″. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Lillie P. Bliss Collection. Photo © 2021 MoMA, NY.

Paul Cézanne, Forest Landscape, 1904–06, pencil and watercolor on paper, 18 5/8 × 23 5/8″. Private collection.

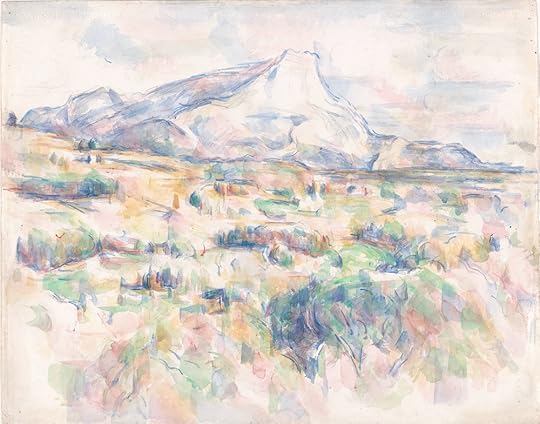

Paul Cézanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire (La Montagne Sainte-Victoire vue des Lauves), 1902–06, watercolor and pencil on wove paper, 16 3/4 x 21 3/8″. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. David Rockefeller. Photo © 2021 MoMA, NY.

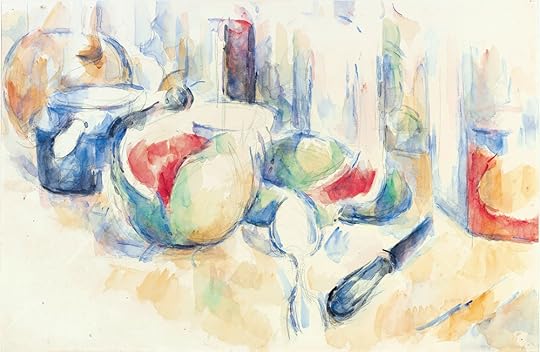

Paul Cézanne. Still Life with Cut Watermelon (Nature morte avec pastèque entamée), ca. 1900, pencil and watercolor on paper, 12 3/8 × 19 1/8″. Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel. Beyeler Collection. Photo: Peter Schibli.

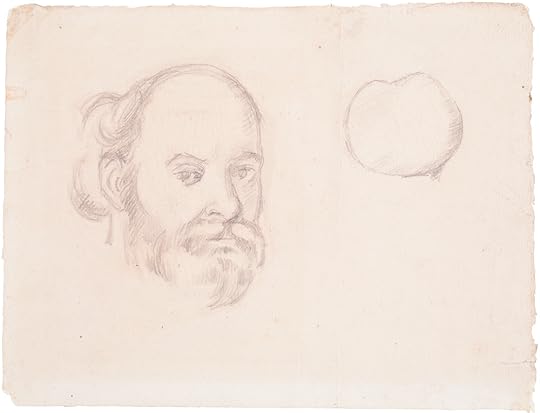

Paul Cézanne, Self-Portrait and Apple (Autoportrait et pomme), 1880–84, pencil on paper, 6 7/8 × 9 1/8″. Cincinnati Art Museum. Gift of Miss Emily Poole. Bridgeman Images.

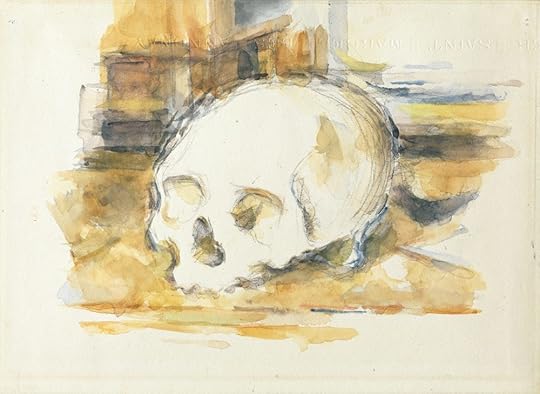

Paul Cézanne, Study of a Skull (Étude de crâne), 1902–04, pencil and watercolor on paper, 9 × 12 1/4″. Henry and Rose Pearlman Foundation (on extended loan to the Princeton University Art Museum). The Henry and Rose Pearlman Collection / Art Resource, NY. Photo: Bruce M. White.

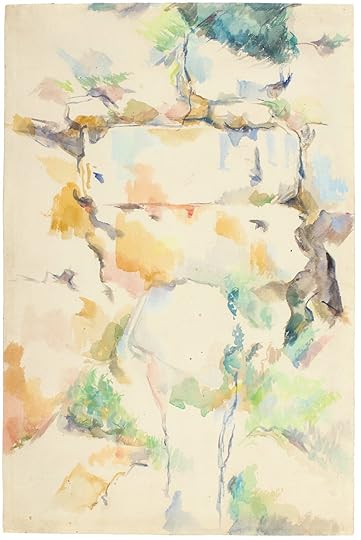

Paul Cézanne, Rocks Near the Château Noir (Rochers près des grottes au-dessus de Château Noir), 1895–1900, watercolor on paper, 18 1/4 × 12″. Private collection.

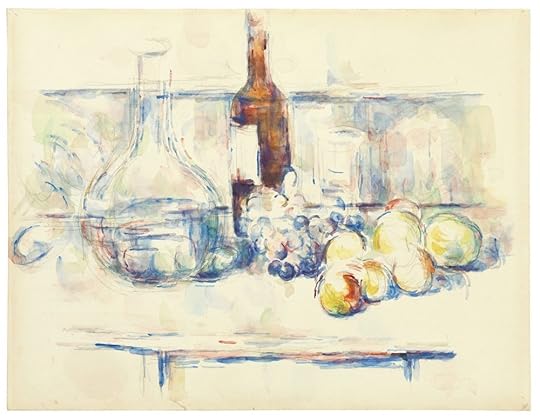

Paul Cézanne, Still Life with Carafe, Bottle, and Fruit (La Bouteille de cognac), 1906, pencil and watercolor on paper, 18 7/8 × 24 5/8″. Henry and Rose Pearlman Foundation (on extended loan to the Princeton University Art Museum). The Henry and Rose Pearlman Collection / Art Resource, NY. Photo: Bruce M. White.

Paul Cézanne, The Apotheosis of Delacroix, 1878–80 (completed later), pencil, ink, and watercolor on wove paper, with a strip added at the bottom, 7 7/8 × 9 1/4″. The British Museum, London © The Trustees of the British Museum.

“Cézanne Drawing” will be on view at the Museum of Modern Art through September 25.

July 1, 2021

Announcing Our Summer Subscription Deal

You’ve been inside all year … need a conversation starter? Announcing our summer subscription deal: starting today and through the end of August, you’ll find plenty to talk about when you subscribe to both The Paris Review and The New York Review of Books for a combined price of $99. That’s one year of issues from both publications, as well as their entire archives—sixty-eight years of The Paris Review and fifty-eight years of The New York Review of Books—for $50 off the regular subscription price.

Since the beginning, when former Paris Review managing editor Robert Silvers cofounded The New York Review of Books with Barbara Epstein, the two publications have been closely aligned. With your subscription to both magazines, you’ll have access to fiction, poetry, interviews, criticism, and more from some of the most important writers of our time, from Joan Didion to James Baldwin, Susan Sontag to T. S. Eliot, Hilton Als to Elizabeth Hardwick.

Subscribe today and you’ll receive:

One year of The Paris Review (4 issues)One year of The New York Review of Books (20 issues)Full access to both the New York Review and Paris Review digital archives—that’s fifty-eight years of The New York Review of Books and sixty-eight years of The Paris Review.If you already subscribe to The Paris Review, we’ve got good news: this deal will extend your current subscription, while your new subscription to The New York Review of Books will begin immediately.

PS: Canadian and international readers, this deal is available to you, too—for $109 and $129, respectively!

June 30, 2021

Place Determines Who We Are

On April 12, The Paris Review announced N. Scott Momaday as the recipient of the 2021 Hadada Award, presented each year to a “distinguished member of the writing community who has made a strong and unique contribution to literature.” To honor the multifariousness of Momaday’s achievements, the Daily is publishing a series of short essays devoted to his work. Today, Julian Brave NoiseCat places Momaday’s work in conversation with the past half century of Indigenous activism it has paralleled.

Pulitzer Prize winner N. Scott Momaday at his Santa Fe studio with old family photos. Photographed on Thursday, February 6, 2020. Photo: Adolphe Pierre-Louis/Albuquerque Journal/ZUMA Wire/Alamy Live News.

The year was 1968, it was finals season at UC Berkeley, and LaNada War Jack (neé Means) sat in the way back of the auditorium, about two hundred or so students perched between her and her professor, N. Scott Momaday. Momaday was just wrapping one of the last lectures of the quarter in that voice-of-God baritone that could give Morgan Freeman and James Earl Jones a run for their money.

War Jack always made sure she attended Momaday’s class. A member of the Bannock Nation from Fort Hall, Idaho, she had moved to San Francisco’s Mission District through the Indian Relocation Act and got into UC Berkeley via an economic opportunity program designed for Black students, becoming the school’s first Native American undergraduate in 1968. It was incredibly meaningful to her to have a Native professor in her first year of college.

At the end of this particular lecture, Momaday turned his focus to one of the most exemplary final papers of the quarter. Without asking War Jack to stand or otherwise identify herself—Momaday knew she was a shy one—he started reading her essay.

“I wrote about our people and the kind of struggle that we had to go through,” War Jack told me this past May. “I ended it really positive but in a Native way. I said something like, ‘As the Sun rises in the morning, we give our morning prayers, and we pray that we continue to exist and survive and to learn and know our cultural ways.’ It was something like that.” After class, Momaday approached his star student. He told War Jack to let him know if she ever decided to write a book.

War Jack didn’t get around to writing that book, at least not for a long while. Instead, like so many other Native students and people in the Bay Area in the waning years of the sixties, she turned her attention to activism. In January 1969, War Jack joined the Third World Strike at UC Berkeley, which in three months secured the first ethnic studies department in the United States. That fall, she teamed up with Native students across the Bay Area, including former Mohawk ironworker and San Francisco State University student Richard Oakes, to form a group called the Indians of All Tribes, which instigated the Occupation of Alcatraz. War Jack stayed on the island for the duration of the nineteen-month protest, bringing national attention to Native American treaty rights and provoking a shift in federal Indian policy from termination to self-determination.

Back in Berkeley, Momaday didn’t make many explicit statements about the political questions Native Americans and the nation were grappling with at the time. He has since revealed that he opposed the Vietnam War and was tear-gassed during a protest on the UC Berkeley campus. But unlike his contemporary Vine Deloria Jr., the Standing Rock Sioux nonfiction writer, Momaday never said much about the Occupation of Alcatraz and the era of Native protest and empowerment that followed. “That is not my temperament. I’m not a political person,” Momaday explained in the 2019 PBS documentary N. Scott Momaday: Words from a Bear. “I follow politics on the television—especially these days when it’s so colorful. But I myself have no interest in writing about government. I much prefer literary and romantic matters.”

Matters of voice and the written word cannot be easily separated from questions of agency, power, and politics, however. Not long after he finished teaching War Jack’s course, Momaday published his pathbreaking first novel, House Made of Dawn, which won the 1969 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction and helped Native authors break into the mainstream—the beginning of a literary renaissance that paralleled our political resurgence.

I have long thought that Momaday’s seeming absence from the political scene was curious, especially after I learned that he was War Jack’s professor—just offstage as one of the defining Indigenous political dramas of the twentieth century played out on Alcatraz Island, which can be seen from Berkeley. But after revisiting his books, I realized that Momaday is apolitical only if one takes a limited view of politics. His work gestures toward an Indigenous, spiritual, culturally rooted, and place-based ethic that resonates with the thrust of Native activism from Alcatraz to Standing Rock and beyond.

Consider Abel, the protagonist of House Made of Dawn, a World War II veteran who returns, shell-shocked and suffering from alcoholism, to his grandfather Francisco’s house on the Jemez Pueblo. After stabbing an albino named Juan Reyes to death because he believes him to be a witch, Abel is convicted of homicide and incarcerated. Upon his release, he’s sent to Los Angeles on the relocation program—the same one that shipped War Jack and so many other Native people from reservations to cities across the United States. In Los Angeles he befriends a Navajo guy named Ben Benally, joins a Native American Church group, and finds work on an assembly line. But he struggles to get by, and slips back into drink. After a particularly bad night on the bottle, Ben puts Abel on a train back to Jemez, where he returns to his relations and his place among his people by performing the traditional funerary rites for his grandfather.

Two things struck me about Abel in this rereading: how close he cuts the profile of a relocated Indian who could have easily been swept up into the Indians of All Tribes or the American Indian Movement, and how small he feels amid the awesome landscapes of the Walatowa village and Cañon de San Diego, as written by Momaday. Indeed, for me, the most striking passages of House Made of Dawn depict Abel moving through the great mystery of his ancestral homelands. The book begins:

Dypaloh. There was a house made of dawn. It was made of pollen and of rain, and the land was very old and everlasting. There were many colors on the hills, and the plain was bright with different-colored clays and sands. Red and blue and spotted horses grazed in the plain, and there was a dark wilderness on the mountains beyond. The land was still and strong. It was beautiful all around.

Abel was running. He was alone and running, hard at first, heavily, but then easily and well. The road curved out in front of him and rose away in the distance. He could not see the town. The valley was gray with rain, and snow lay out upon the dunes. It was dawn. The first light had been deep and vague in the mist, and then the sun flashed and a great yellow glare fell under the cloud. The road verged upon clusters of juniper and mesquite, and he could see the black angles and twists of wood beneath the hard white crust; there was a shine and glitter on the ice. He was running, running. He could see the horses in the fields and the crooked line of the river below.

And it’s in this decision—to put man in his place from the start, and to hold space to revere the earth, creation, and the ceremonies that honor them—that you can see Momaday pointing to something profound. “Both consciously and subconsciously, my writing has been deeply informed by the land with a sense of place,” Momaday writes in a postscript to the 2010 edition of the book. “In some important way, place determines who and what we are. The land-person equation is essential to writing, to all of literature.”

Momaday homes in on this idea in his most recent book, Earth Keeper: Reflections on the American Land, which he describes as a “declaration of belonging” and an “offering to the earth.” In this lyrical seventy-seven-page ode to the American West, Momaday revisits stories he has turned over throughout his career: the origin of the Kiowa, the meaning of his name, and the pueblo village of Walatowa, where House Made of Dawn is set. Earth Keeper never mentions the Water Protectors or Land Defenders at the vanguard of the Indigenous rights and climate justice movements today. But it doesn’t need to in order to render a blistering critique of colonial and capitalist relationships to the other-than-human world and to sing with the power of Indigenous environmental epistemologies and ontologies.

“Ours is a damaged world,” Momaday writes. “We humans have done the damage, and we must be held to account. We have suffered a poverty of the imagination, a loss of innocence. There was a time when ‘man must have held his breath in the presence of this continent,’ this New World, ‘commensurate to his capacity for wonder.’ I would strive with all my strength to give that sense of wonder to those who will come after me.”

Putting Momaday’s work in conversation with the past half century of Indigenous activism it has paralleled is, I think, an illuminating way to consider both his books and the ideas undergirding Native movements. Voice is a fundamental building block for change, and ideas often have roots that run deeper than their political valence. If Momaday can speak so authentically to the Indigenous experience—our long odyssey through an imperial apocalypse, and the enduring power of our ceremonies and cultures, rooted in land and place, as organizing and governing principles—without saying a word about a political party, politician, or even an act of protest, then that just illustrates how fundamental the things he depicts are to our people. Epistemology, grounded in who we are and where we come from—our very being—becomes ontology. It’s from that starting place, that hearth, that you get the Alcatrazes, Standing Rocks, and Lanada War Jacks.

Despite being one of the most significant Native organizers in U.S. history, War Jack rarely describes herself as an activist. “My sons tease me and tell me that I’m a Berkeley radical and all that,” she says. “I’ve had to force myself to speak and say things because if nobody is going to say it, then I wind up having to say it or do it.” At heart, she still is the young woman in the back of the lecture hall. I see a little Abel in that.

But in a small way, Momaday inspired War Jack to use her voice. She’d never considered writing a book until he planted that seed all those years back. And life kept her from it for many decades. But in 2019, the year of the fiftieth anniversary of the Alcatraz Occupation, she self-published Native Resistance: An Intergenerational Fight for Survival and Life, which traces our long struggle for self-determination on stolen land back across centuries.

I asked if she planned on sending her old professor a copy.

“I don’t know if he’ll remember me,” she said. “But I’ll have to do that.”

Julian Brave NoiseCat (Secwepemc/St’at’imc) is a fellow of the Type Media Center, columnist for Canada’s National Observer, and contributing editor with Canadian Geographic. He’s currently working on his first book, We Survived the Night, which will be published by Alfred A. Knopf in North America.

June 29, 2021

Redux: Nothing Is Commoner in Summer than Love

Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

Phillips in Provincetown, Massachusetts, in 2018. Photo courtesy of Reston Allen.

This week at The Paris Review, we’re highlighting the work of queer and trans writers in our archive in honor of Pride. Read on for Carl Phillips’s Art of Poetry interview, Jeanette Winterson’s short story “The Lives of Saints,” Timothy Liu’s poem “Action Painting,” and a selection of diary entries by Jan Morris.

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, and poems, why not subscribe to The Paris Review? You’ll also get four new issues of the quarterly delivered straight to your door. Or, choose our new bundle and you’ll also receive Poets at Work for 25% off the cover price.

Carl Phillips, The Art of Poetry No. 103

Issue no. 228 (Spring 2019)

INTERVIEWER

With that book you were part of a watershed moment for gay poetry.

PHILLIPS

Around the time of my first book, Mark Doty’s My Alexandria appeared. That was a very important book for me. And within a few years were first books from Timothy Liu and Rafael Campo. To write about having sex with someone of the same sex, to write about same-sex love and vulnerability—these were very new things in poetry, as far as I could tell. It’s something that gets taken for granted now, but it’s great that something like this can be taken for granted. Not that any of this means it’s not still very frightening, even dangerous, for many people to speak openly about who they are, and to live openly as they are. For many people of my generation, there was only the hetero model—so what to do when you have the freedom to make your own model?

The Lives of Saints

By Jeanette Winterson

Issue no. 128 (Fall 1993)

It is true that on bright days we are happy. This is true because the sun on the eyelids effects a chemical change in the body. The sun also diminishes the pupils to pinpricks, letting the light in less. When we can hardly see we are most likely to fall in love. Nothing is commoner in summer than love and I hesitate to tell you of the commonplace but I have only one story and this is it.

Action Painting

By Timothy Liu

Issue no. 144 (Fall 1997)

A canvas we cannot stretch across the frame

nor staple down to fact: a ladder leaning

against an awning, workers pitching tar

on the roof of a church packed each week

with swine—a chain of pearls dangling

off the limbs of an artificial tree

where boy scouts gather in a tool shack,

jacking off to the sounds of Perry Como

on a karaoke machine—a televised priest

gesticulating wildly at the pulpit again.

Redpath Museum, McGill University, Montreal, Québec, Canada, 2017

Diaries

By Jan Morris

Issue no. 225 (Summer 2018)

Not long ago there was certainly more of it, but shifting ecology has robbed us of the grass snakes, glowworms, and occasional lizards that used to frequent the place—even the toads seem scarcer. Never mind, butterflies visit me as I laze, bees and wasps buzz around, beetles and caterpillars make for the gravel, sometimes a handsome dragonfly comes up from the river or a robin hops in. A sudden scuffle in the bushes means that a clumsy squirrel or two are in there—and yes, there they are leaping erratically from branch to branch. More often a crow or a blackbird swoops or cackles among the trees, and a wood pigeon monotonously serenades its mate. Sometimes coveys of seagulls from Cardigan Bay pass overhead, on their way to a promising harvesting somewhere: our owls are still asleep, I suppose, but I like to think of them anyway, there in the dark of the woods.

Ah, but here comes our merry postman with his morning consignment of trash. Elizabeth drops her trowel and pops off to make some coffee, and I pull myself together, stretch, send my respectful regards to Ovid and the emperor, and leave the yard to the rest of them.

If you enjoyed the above, don’t forget to subscribe! In addition to four print issues per year, you’ll also receive complete digital access to our sixty-eight years’ worth of archives. Or, choose our new bundle and you’ll also receive Poets at Work for 25% off the cover price.

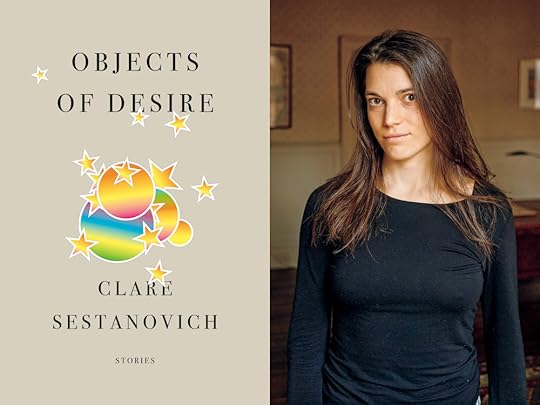

The Momentum of Living: An Interview with Clare Sestanovich

Photo: Edward Friedman.

Clare Sestanovich’s short story “By Design,” which first appeared in the Spring 2020 issue of this magazine, features the unforgettable Suzanne, a woman facing accusations of sexual harassment, going through a divorce, and struggling to accept her adult son’s independent life. In the opening tableau, she sits across from her future daughter-in-law at a restaurant. Suzanne keeps her criticism of the impending marriage to herself but outwardly betrays a deep, unspoken malaise. She consumes an entire basket of bread by soaking each bite in red wine, as if gorging on the sacrament.

In Objects of Desire , which includes the story, Sestanovich revitalizes James Joyce’s style of “scrupulous meanness”—depicting the setting and inhabitants of her narratives in an ultrarealistic, if sometimes unforgiving, light. Moments of epiphany, or at least self-understanding, accompany everyday activities. Suzanne, for example, finds solace not in a major dramatic resolution but in the acquisition of a houseplant. But Sestanovich engages more self-consciously with a matriarchal literary lineage. Her steady hand and bone-clean prose recall such foremothers as Joan Didion, Zadie Smith, and Jhumpa Lahiri. She weaves each narrative around universal trials of womanhood. Through hysterectomies, miscarriages, and unstable relationships, her cast of canny protagonists come to terms with their wants and needs.

Over the past year, Sestanovich has continued to release new work in Harper’s, The Drift, and The New Yorker, where she is an editor. Her characters provided me companionship throughout the solitude of quarantine, and the publication of her full-length debut this week coincides with our uneasy communal reemergence. Sestanovich’s stories about social encounters—meeting strangers on flights, striking up conversations with bartenders, sitting through dinners with in-laws—feel eerily appropriate for this moment of easing back into the world.

Sestanovich and I corresponded by email in the weeks leading up to the publication of Objects of Desire. At the start of our conversation, she reminded me that we had attended the same Quaker prep school. There, students met for worship every week, sitting in silence to await communion with God or one another. This got me thinking about how such veneration of silence might have affected the emergence of Sestanovich’s voice as a writer. Her stories are built around what is waiting to be said—the desires that remain unspoken or held within.

INTERVIEWER

I loved the piece you wrote for The New Yorker earlier this month about chance encounters. The city is “a cartography of a shared world that does not insist on bringing everyone together,” you write, adding that “in parting ways, we are still imparting something of ourselves.” You structure many of your stories around chance and coincidence as well. What purpose, what friction, do passing encounters bring to a narrative?

SESTANOVICH

“Don’t insist on bringing everyone together” is actually a pretty good distillation of my views on plot—though when it comes to hosting a dinner party, I promise I’m more conscientious about togetherness! There’s a certain narrative tidiness that coincidence, if used well, can helpfully disrupt. A lot of us have expectations, in both life and fiction, about the hinges on which our stories are going to turn—you know, the moments the Hallmark aisle tells you to commemorate. Births, deaths, all the things you’d throw parties about.

INTERVIEWER

Sounds like Clarissa Dalloway.

SESTANOVICH

But, at least in my experience, reckonings have very little regard for milestones. Coincidences are sort of antimilestones, reminders—and not always comfortable ones—that the momentum of living builds and breaks in unforeseen ways.

INTERVIEWER

The title of the first story, “Annunciation,” brings to mind the iconography of the Virgin Mary and her impregnation. But Ben is the virgin of the story, and Iris, despite her symbolically virginal name, is quite sexually experienced. How did you go about finding new ways to represent and play with gender and female sexuality in literature?

SESTANOVICH

At some point in my late teens, in college I guess, I experienced what felt like a revelation—women I knew could talk about sex as frankly, as confidently, occasionally as crassly, as I had always imagined men did. And then, soon thereafter, I experienced what felt like a second revelation—all that talking might not have any bearing on how we were actually experiencing sex. There was some way in which our lucid, sincere, empowered thinking didn’t translate into lucid, sincere, empowered acting—for structural reasons, for personal reasons, for murky reasons that we were always at a loss to explain. When I write about sex, I think what I’m trying hardest to capture is that murkiness. What keeps us from getting what we want? What keeps us from knowing what we want?

Iris has what you call experience. She’s intentional about acquiring it. She’s had a lot of sex, and I imagine she thinks of herself as someone who’s comfortable talking about it—good at talking about it. She isn’t, however, very comfortable with vulnerability. She looks away when she sees something real and raw in Ben’s face, she hides her most important truths from her mother, and she falls asleep when there’s something she wants to avoid looking at head-on. I’ve tried to be clear-eyed about sexuality in these stories, and that includes being clear-eyed about all the things we can’t see, or don’t let ourselves see.

INTERVIEWER

Your dedication—“For my mother and her mother”—sets the tone for the collection so immediately, and motherhood is indeed a major theme. But so is the decision not to have children—abortion, IUDs, the mental and physical recovery from a miscarriage, hysterectomies. I’m curious how birth control can function as something of a narrative device. Does its inclusion change how we write female characters and stories?

SESTANOVICH

Yeah, I think so! At a purely linguistic level, I’m interested—sometimes charmed, sometimes repelled—by how the language of procreation has shaped the way we think and talk about creativity. We “gestate” ideas. Some people, I have learned, observe their books’ “birthdays.” So birth control, I think, invites us to think more broadly about the peculiar relationship between creativity and choice. We live in a world where you can choose not to create or procreate. Thank god! But then what? What does it look and feel like when you do choose? These are operative questions for mothers, for artists, for anyone who has felt liberated, or paralyzed, by the revelation of their own agency. I’m drawn to characters who think of themselves as creators—in particular, to characters who yearn to create but struggle to choose. Indecision is so tricky to write about, because stuckness and inertness are the enemies of narrative development. And yet it feels so important to me to try. We know that what looks like paralysis can be a frozen surface over very turbulent waters. How do you put that on the page? The last paragraphs of Miranda July’s near-perfect story “Roy Spivey” contain one of the best examples of this.

INTERVIEWER

Is that the one that ends with the protagonist just standing still while listening to the sounds of her husband move around the house?

SESTANOVICH

“The longer I stood there, the longer I had to stand there.” It’s so good! I’m always looking for examples of paralysis in fiction—and trying to find out if I can write some of my own.

INTERVIEWER

Throughout the collection, you depict women at different stages of adulthood—from late adolescence to menopause. What was it like to assume the voices of women of varying ages and lived experience?

SESTANOVICH

Well, it’s really fun! I guess now I’ll do something that probably no fiction writer should do unless under duress, which is bring up autofiction. Some of the characters in these stories seem a lot like me—twentysomethings who live in New York and are pretty confused about the shape and direction of their lives. Guilty as charged! And yet I don’t feel that there is any more of me in those stories than in others. There’s a story in the book about a middle-aged woman who is unhappily married, frustrated at work, deeply and uncomfortably jealous of her son’s youthful potential, and driven to do extremely destructive things—to herself and others. I found that story almost unbearably personal to write, even though superficially I share relatively little with its protagonist, because it meant accessing my own destructiveness. John Berryman once said, about the central character of The Dream Songs, “Henry both is and is not me, obviously. We touch at certain points.” I think that’s true of every character I’ve ever written. The points aren’t always obvious. Often you have to reach before you touch, and the reaching—imagining your way both farther beyond your life and deeper into yourself—is where meaningful things happen.

INTERVIEWER

The pairing of Debbie and Georgia as dual protagonists in “Security Questions” is quite shocking. They are drawn together across generations by the arbitrary circumstance of Dana’s affair—Debbie as wife and Georgia as girlfriend. They also reminded me, in a way, of Iris and her mother in “Annunciation.” What interests you about intergenerational relationships between women?

SESTANOVICH

I dedicated this book to my mother and grandmother, as you’ve mentioned, because writing is passed down matrilineally in my family—my mom taught me to write, and her mom taught her to write. This is an unusual, and very fortunate, arrangement, but it’s not so different from what I think is constantly being transmitted across generations. Our received narratives are a kind of inheritance—for good and, quite often, for ill. Debbie isn’t Georgia’s mother, but she’s authored her life in a way that fascinates Georgia. Does Georgia admire it? Does she want to replicate it? My guess is probably not—after all, Debbie’s husband is pretty shitty—but she isn’t quite sure. And isn’t that the way of all “role models”? They seem monumental at least in part because we are still under construction.

Debbie’s own mother died a long time ago, and Debbie is now older than her mother ever lived to be. She grieves this fact, and I think it’s a very real kind of loss. Before, even though her mother was dead, she was still alive as a model. When Debbie turned sixty, she could imagine what her mother had been like at sixty—she could turn to her for lessons about sixtyness. Now, for the first time, she has to figure out the lessons on her own. The story she writes will be, in some real sense, hers alone. Now she is the writer, and someone else will be the reader.

INTERVIEWER

As the title suggests, Objects of Desire centers on individual “wants and needs.” In the story by that name, Zeke is forthright about voicing and acting on his desires whereas Val has been brought up to keep it all in. Why did you choose an all-female cast of protagonists to embody this tension between spoken and unspoken desires?

SESTANOVICH

In this story, the phrase “wants and needs” comes up in a therapeutic exercise. The premise of the exercise is simple—writing down your desires is the first step toward fulfilling them. At least some of the characters in the story think this is really stupid, and they’re not totally wrong. Squint one way and it sounds more or less like The Secret. But look at it another way and it’s just the project of literature. The task of writing, for me, is in part a response to the experience of longing. I put the feeling on the page because I often have no idea where else to put it. I don’t expect fiction to become reality in the strictest sense, but by turning fantasy into a very literal object—you’ve held my book in your hands—hasn’t it, in another sense, done exactly that?

I don’t have some grand theory that all fiction is just wish fulfillment by another name, but I am really interested in what happens when we take oblique approaches to desire. As you note, a lot of the women in these stories have a hard time saying what they want. There’s a structural explanation for that. Many women are expected be repositories for other people’s desires, which doesn’t leave much room for them to be the actual source of desire. I buy all that, but I’m also aware that having distance from one’s desires isn’t always a burden—in fact, it can feel, for better or worse, like a kind of comfort. To identify an “object of desire,” you have to first step back and get a good look at the thing—to observe it, to imagine having it before you actually do, to measure what it would take for you to reach out and get what you want. The space between you and that object is the space of subjectivity—the space in which you become yourself.

INTERVIEWER

Yes, you handle the problem of both identifying one’s desires and voicing them. Can you speak to the theme of performance in your stories—especially women performing for men?

SESTANOVICH

There’s one truly professional performer in this book—a musician who is actually among the least performative people in the book. He’s quiet, unassuming, private, more of a soothing presence than a galvanizing one. Another character observes that he “doesn’t seem like a rock star.” In that same story, there’s a woman who, by all appearances, is a demure office worker. When her vitriolic tweets suddenly go viral, everyone else is shocked by the new side of her that’s been “revealed,” but the woman herself says, Nope, this is just me. I’m interested in what just me means—about all the blurry places where our ideas of performativity and authenticity overlap, defying any straightforward sense of what a real self would be. The people I’ve described here are, very literally, pretend. But are they more or less pretend than the person I present to the world when I am trying to make a very specific, perhaps not entirely “true,” impression? Many of the characters I write about are, as the expression goes, trying to find themselves. But which self? The real one? The fake one they like best? The sort of real, sort of fake one the audience likes best? And when and why did we get so obsessed with realness, anyway?

INTERVIEWER

Each story is about transitional phases, perhaps illustrated most beautifully in “Brenda,” in which the title character lives alone in a trailer on the lot where she once planned to build a house with her partner. Has your own reading of these stories changed after this past year of transition and tenuous human connection?

SESTANOVICH

When I was sending the first draft of this manuscript out to agents, I said that the stories were about loneliness. In general, I can’t bear to be asked what the book is “about,” but this was my best attempt. I imagine we’ve all learned something about the texture of loneliness this year, and some of those lessons may become legible only with time. What I already knew, but have certainly come to know more immediately and intensely, is that my own loneliness has more to do with the gyre of time spent with myself than with the hole of time not spent with others. There are characters in this book who share that, I think—who are driven back upon themselves and, as Didion says, find no one at home, or find many people, many selves, they no longer care to share quarters with. We were home alone in many ways this year. My own writing and reading filled much of that space—it brought me relief, gave me purpose, kept me company.

Elinor Hitt is a Ph.D. student in English literature at Harvard.

Read Clare Sestanovich’s short story “By Design,” which appeared in the Spring 2020 issue.

June 28, 2021

On Baldness

Georg Pencz, Samson and Delilah, ca. 1500–1550, engraving, 1 7/8 × 3 1/8’’. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

I

The ships landed on the beaches of Normandy before dawn. Along eighty kilometers of coastline, amphibious vessels slid out of the water like sea monsters and shook themselves dry, flinging off their damp bodies thousands of men smeared with the same euphoria of war. Insatiable, the beach seemed to devour the troops. Aircrafts helped feed the assault from the sky: one by one, the soldiers surrendered themselves to flight, to the allure of the fall. Their jellyfish silhouettes—ephemeral but perfect for slipping through the air—negotiated gravity until the feel of the sand returned to them the animal weight of their bodies.

The landings lasted more than a month and with them the war was near its end. No seaborne invasion has ever equaled that of the Allies on the coast of France. Following the tides of the English Channel, armies from all over the world gathered to free France from Nazi occupation and to contain Nazi control of Western Europe. Besides soldiers, the crew also included spies, nurses, and correspondents. Among them were Robert Capa, J. D. Salinger, and Ernest Hemingway—their eyes wide open.

*

Thanks to the work of Robert Capa, there is now a large photographic archive of the Allies’ expedition in France. Many of his photographs capture in detail the textured expressions of civilians and soldiers, whose faces convey everything from the meekness of subjugation to the ecstasy of liberation, from the understanding of survival to the sheen of fear.

Among these images that bear witness to the Allies’ victory over the Nazis and shed light on the jubilation that flooded the streets of French towns is a series of photographs taken in Chartres just two months after the Normandy landings. The series is a visual record of the violence deployed against women accused of carrying on relationships with German soldiers or collaborating with them. While men convicted of the same crime were killed, the women were subjected to a different kind of punishment: in a public place, as everyone watched, their hair was shorn down to their scalps. The purpose of their shaved heads was not only to provoke disgust in those who saw them but also to serve as a protracted reminder of the betrayals they were accused of.

*

Robert Capa’s photographs manage to convey the various stages of this public shaming. The first few images capture the moment of mutilation. Some women look straight at the camera, having clearly learned to quiet their fear. The dejection on their faces is as transparent as the pleasure the men feel as they run their fingers through locks of hair that don’t belong to them, demonstrating a level of intimacy exclusive to lovers and tormentors. Around them, the audience gives a satisfied smile and applauds at the hard snip of the shears.

Heads shaven, sometimes half-naked with swastikas tarred on their bodies, the women were paraded down the streets to the beat of a drum, either by foot or on top of a wagon. Their exposed scalps transformed them into abject creatures devoid of beauty. To consummate this punishment, their hair was swept into a mound that burned until the smell filled the air.

The bodies of these women had become another territory to be recaptured. Violating them was a strategy that served to denigrate the enemy and ensure the finality of defeat. The public shaming of French women turned into a widespread pursuit, a part of the everyday ritual of French liberation.

II

The practice of shaming women by shaving their heads has Biblical origins. This punishment is alluded to in several Books: Jeremiah, Isaiah, Deuteronomy, Corinthians. In each case the bald woman carries the burden of shame, and her shorn head is a stigma signifying moral weakness and vice. In Isaiah, for example, God threatens to shave off the hair of the daughters of Sion for walking with their heads held high and a suggestive gait, dressed in necklaces and jewels. In Deuteronomy, God tells his warriors that if they should come across a captive woman they find attractive and would like to marry, they must first lock her up in their houses for thirty days, stripped of the clothes of her captivity; there, she must trim her nails and shave her head. Clearly, God was banking on a loss of appeal.

*

In the Middle Ages, women accused of adultery had their heads shaved. In the twentieth century, the female partners of Spanish Republicans, German women who socialized with non-Aryan men, and French women who collaborated with the Germans met the same fate. Each case was a question of eroticism. What they sought to do was unsex the body that had rebelled.

*

Hair has long been viewed as a symbol of sex and status in cultures across the world. It was common among Egyptians for free people to keep their heads shaved and wear a wig. The Greeks offered hair as tribute to the gods and depicted their goddesses with long, abundant locks. There are other examples in mythology that pay special attention to hair: Delilah steals Samson’s powers when she has his hair shaved; Medusa’s head is covered in snakes instead of curls. The Romans were convinced that people with little or no hair were in some way deformed. During Victorian times, respectable women wore their hair up while prostitutes wore it loose.

III

My first witches were the ones in the Roald Dahl novel. It’s not that I’d never seen any before. I was familiar with all of the fairy-tale witches, but none of them scared me. I always thought there was something charming and likable about those witches. Plus, they were right to be angry.

The Dahl witches were the first ones that really frightened me, and showed me that the world could be a dangerous place. What upset me most of all was the possibility that a kind, ordinary lady could be a witch, that she could be hiding a lump of soft, toeless flesh inside her shoes, and that an innocent head scratch might in fact betray the unwelcome presence of a wig. This section gave me nightmares:

There now appeared in front of me row upon row of bald female heads, a sea of naked scalps, every one of them red and itchy-looking from being rubbed by the linings of the wigs. I simply cannot tell you how awful they were, and somehow the whole sight was made more grotesque because underneath those frightful scabby bald heads, the bodies were dressed in fashionable and rather pretty clothes. It was monstrous. It was unnatural.

A crowd of bald heads was irrefutable proof that Dahl’s witches were more than just a story. The fact that the women didn’t have any hair was no fantasy, and this made their recipe for turning children into mice plausible, too.

*

Hair also braids my family history. My sister was six when she stopped growing. The marks my parents made on the wall to measure the passage of time remained unchanged for several months. Even though we are less than two years apart, a gulf began to open between us in those months. I behaved like I was the big sister and exercised the independence of the firstborn child who can already read to herself. My sister, on the other hand, was small and quick to smile, her cheeks colored by the sun. And her hair was so long it fell down to her waist.

She was the only person who seemed not to mind the apparent sluggishness in her growth. She took advantage of all the benefits her ninety-something centimeters afforded her for longer than was normal: she pretended to sleep so she wouldn’t have to go for a walk, she never carried anything heavier than an empty lunch box, and though we never said a word about it, the bottom bunk soon became part of her domain.

The woman at the beauty salon took one look at my sister and decided she’d stopped growing because of the length of her hair; it would have to be cut. Just to the shoulder, she said, as though those words made the verdict any lighter. It took just a few minutes for the sharp edge of the hairdresser’s shears to trim back my sister’s childhood bliss and our parents’ suffocating fantasy: their daughter would grow after all, just like the other kids.

*

When my mother lost her hair, I mislaid words. Not just my own, but also words that weren’t mine. Strands of my mother’s brown hair wound down my throat and knotted inside me like wire. Everything I might have said was caught behind that barbed, rusted tangle. In hindsight, and thanks to the unyielding residue left by my period of quiet, I now believe that chopping my hair off might have been the only way for me to come to terms with my silence. What has stayed with me from those months is a discomfort between my ribs. A deep, stabbing pain that I feel whenever I see a woman wearing a scarf on her head.

—Translated from the Spanish by Julia Sanches

Mariana Oliver was born in Mexico City in 1986. She received a master’s degree in comparative literature from the National Autonomous University of México (UNAM) and is currently working toward a doctoral degree in modern literature at the Iberoamerican University in Mexico City. Oliver was granted a fellowship for essay writing at the Foundation for Mexican Literature and was awarded the José Vasconcelos National Award for Migratory Birds.

Julia Sanches is a translator of Portuguese, Spanish, and Catalan. She has translated works by Susana Moreira Marques, Claudia Hernández, Daniel Galera, and Eva Baltasar, among others. Her shorter translations have appeared in various magazines and periodicals, including Words without Borders, Granta, Tin House, and Guernica. A founding member of Cedilla & Co., she sits on the Council of the Authors Guild.

Excerpted from Migratory Birds , by Mariana Oliver, translated by Julia Sanches. Excerpted with the permission of Transit Books. Copyright © 2021 by Mariana Oliver.

June 25, 2021

Staff Picks: Dopamine, Magazines, and Exhaustive Guides from A to Z

Hazel Jane Plante. Photo: Agatha K. Courtesy of Metonymy Press.

Just as there are an infinite number of stories to be told, there are an infinite number of ways to tell a story. Take Hazel Jane Plante’s Little Blue Encyclopedia (for Vivian) as case in point. When the narrator’s best friend dies, she decides to write an encyclopedia about her friend’s favorite television show. While Plante’s novel takes the form of an A-to-Z guide to the fictional one-season TV series Little Blue, it also tells the story of a queer trans woman mourning the loss of her straight trans best friend, for whom she felt an overwhelming, unrequited love. Through her thorough examination of the show, the narrator creates a beautiful, holistic homage to Vivian’s life. At the end of Little Blue Encyclopedia (for Vivian), I found myself in awe of the book’s author. Not only has Plante imagined an incredibly complex TV show from scratch, she’s written an entire encyclopedia about said show, and somehow told a deeply heartfelt story of mourning, love, and friendship in the process. —Mira Braneck

It is a cliché to observe that the more things change, the more they stay the same, but clichés are clichés for a reason, and across time, space, and history, the squabbles and dilemmas of leftist political movements seem to repeat themselves over and over. The criticisms that the Egyptian feminist, communist, and leader of the seventies student movement Arwa Salih lodges against her generation in the 1996 book The Stillborn: Notes of a Woman from the Student-Movement Generation in Egypt (translated from the Arabic by Samah Selim) are at once particular to her country and moment and also familiar outside their context. A supposedly worker-led movement, she observes, quickly becomes dominated by the bourgeois intellectual class, a vanguardism that functions as “the first step on the road to disengagement from the real world … One of the coarsest forms the hierarchy took was the division between ‘authors’ and everyone else—the drudges who did the heavy lifting and who were also the most likely to be captured by the police.” One chapter, “The Intellectual in Love,” is fiercely critical of the sexism displayed by ostensibly radical men: “Our friend considers it his right to exploit her. His logic is that since she’s accepted exploitation, she deserves it.” Brief in pages but deep in scope, The Stillborn is a fascinating analysis of both revolutionary politics as a whole and the failures of the Egyptian student movement in particular. —Rhian Sasseen

Will McPhail. Photo courtesy of McPhail.

Even in the most socially agreeable of circumstances, it can be hard to make genuine connections with others. Considering our recent trend toward a distraction-hungry, internet-fueled, dopamine-overloaded dystopia and all the longstanding anxieties that come with the uniquely human awareness of a finite existence, it’s a wonder that any of us manage to make friends at all. The cartoonist Will McPhail investigates this very wonder with his debut graphic novel, In., which follows a burgeoning illustrator named Nick as he struggles to connect with those around him, not quite finding a meaningful enough balance between what is considered socially palatable and what he actually feels, adrift between the performative and the authentic. As a medium, the graphic novel is beautifully suited to depicting such concerns, and McPhail’s art style—reminiscent of his work in The New Yorker—is minimal, direct, and as emotionally dense as any work of contemporary poetry. The spare use of color against a largely monochrome palette is particularly effective, not just in illustrating emotional changes but in conveying them—the vibrant fantasies of Nick’s inner world are as arresting, enveloping, and ultimately fleeting for the reader as they are for the protagonist. In. is a sharply observed, funny, and achingly poignant examination of a subject widely understood yet rarely described, rendered subtle and playful, and made wonderfully new. —Christopher Notarnicola

Showtunes is a great Lambchop record, and that’s a high bar for a band whose output almost always lands somewhere in that range between really good and incredible. Songwriter and bandleader Kurt Wagner has been, over the past several LPs, edging toward a new sort of tweaky electronic twang, autotuning and otherwise manipulating his soft, gravelly voice while also using loops, programmed drums, synths, and other effects that don’t usually appear in alternative country music. I still haven’t fallen in love with the band’s previous album of original material, This (Is What I Wanted to Tell You), on which Wagner’s inimitable songwriting voice feels lost in a storm of moody electronics; it feels like he hadn’t yet found a way to integrate these seemingly competing impulses. But barely two years and one pandemic later, he has. Showtunes is a strange and comforting album: quiet, melancholy, but not without hope and consolation. Melody is at the forefront, as are the trappings of Lambchop’s sound—fingerpicked acoustic guitar; long, loping musical phrases; gorgeous, winding vocals; artfully arranged horns—but subtle manipulations abound. It all feels of a piece, a sweet way of welcoming a new season. —Craig Morgan Teicher

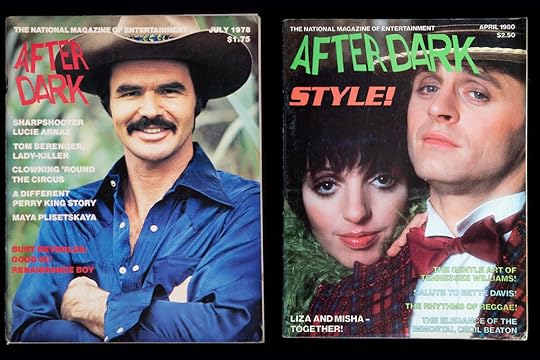

A few weekends ago, a sidewalk sale on St. Mark’s was nicely crammed with young folks eyeing zines and small-press wares, taunting dogs with skateboards and one another with skin. Among the hiply imperfect, inclusive offerings was a magazine polished to a high shine. After Dark was a nightlife and culture periodical produced through the seventies by Danad, then publisher of Dance Magazine. Though officially created to cover dance and city culture, After Dark was gay as the day is long. Hiding in plain sight are letters to the editor requesting further photographs of a model described as “body beautiful” (they were furnished), advertisements for Fire Island bars and NYC baths, celebrations of the nude male form, and lots of purveyors of caftans. Winking interviews with Robert Redford and Burt Reynolds share a binding with campy fashion editorials and spreads of ballet dancers au naturel. It is lovely and light and sexy; if you are thinking the magazine may have faded in the eighties, partly under criticism of a lack of political heft or inclusive gaze, you’d be right. After Dark remains, however, a beautifully shot portrait of a moment. Left Bank Books has lovingly assembled a collection of After Dark issues, many of which are for sale and some of which will be on display in the storefront window through July 5. —Julia Berick

The July 1978 and April 1980 issues of After Dark. Photos courtesy of Left Bank Books.

The List as Body: A Collection of Queer Writing from The Paris Review

Photo: Charlotte Brooks. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

RL Goldberg’s 2018 essay “Toward Creating a Trans Literary Canon” offers up a list of phenomenal trans writing: Eli Clare’s Exile and Pride, a truly life-changing book; Leslie Feinberg’s utterly devastating Stone Butch Blues; and one of my all-time favorite pieces of writing, Andrea Lawlor’s Paul Takes the Form of a Mortal Girl. But it is Goldberg’s explanation of the ethos behind the list to which I keep returning: “It’s not a canon exactly, but a corpus. It’s something more like a body: mutable, evolving, flexible, open, exposed, exposing. It’s the opposite of erasure; it’s an inscription.” To celebrate Pride in my capacity as intern here at The Paris Review, I’ve been reading works by the queer authors in the latest issues of the magazine. The archive contains a myriad of fantastic queer writers, but I wanted to recognize some of our contemporary contributors, folks whose work has appeared in our most recent pages. As I read, I thought a lot about Goldberg’s notion of inscription and the list as body: mutable, evolving, flexible. What resulted is a corpus nowhere near complete, final, or comprehensive—and I don’t want it to be. Rather, it’s meant to pay tribute to the diversity of art created by our queer contributors, each of them offering something distinct to readers of the Review. Some of the work is about sexuality, some of it is about sex, and some of it is about war, about gender, about eggs in a hot pan.

Many of these writers hold identity at the center of their work; the particularities of each piece demonstrate the various (and incredibly individual) meanings of “identity” itself. Lydia Conklin’s “Rainbow Rainbow,” a coming-of-age story published in the Summer 2021 issue, depicts two queer suburban teenage girls, one out and one coming to terms with her burgeoning sexuality, as they venture to Boston to meet an internet crush. In “Token,” Jericho Brown ruminates on the privilege inherent in invisibility:

… I want the scandal

In my bedroom but not in the mouths of convenience-

Store customers off the nearest highway. Let me be

Another invisible,

Used and forgotten and left

To whatever narrow miseries I make for myself

Without anybody asking,

What’s wrong. …

Similar to “Rainbow Rainbow,” Brown’s poem sees the city as a haven. For the girls in Conklin’s story, Boston offers the possibility of a different life; in “Token,” the city offers the space for community. The narrator of the late Anthony Veasna So’s “Maly, Maly, Maly” is ready to flee G Block, the “asshole of California,” for the promise of a four-year college in Los Angeles. “An hour ago we became outcasts,” So writes:

One of us—not me—would not shut the fuck up. And since the grandmas are prepping for the monks and need to focus, we’ve been banished outside to choke on traces of manure blown in from the asparagus farms surrounding us, our hometown, this shitty place of boring dudes always pissing green stink.

And according to the Mas, everything about us appears at once too masculine and too feminine: our posture—backs arching like the models in the magazines we steal; our clothes—the rips, studs, and jagged edges—none of it makes sense to them. The two of us are wrong in every direction. Though Maly, the girl cousin, strikes them as less wrong than the boy cousin, me.

So’s story deals deeply with family, its restrictions and its promise. Ocean Vuong’s “Rise & Shine,” a seriously sensual and cinematic poem, takes up the identity of being someone’s son, and what is passed from parent to child.

Melissa Febos and Danez Smith both hold a single word at the center of their pieces in the Review. In “The Mirror Test,” Febos delves into the linguistic history of the word slut along with her own adolescent experience of sexuality and gender. I think you can guess the focal point of Smith’s “my bitch!”:

o bitch. my good bitch. bitch my heart.

dream bitch. bitch my salve. bitch my order.

bitch my willowed stream. bitch my legend.

bitch like a door. your name means open

in the language of my getting by. bitch sesame.

In Garth Greenwell’s “Gospodar,” the Bulgarian word for “bitch,” kuchko, gets at the core of the narrator’s pleasure in his BDSM encounter with another man. Greenwell’s story is truly one of the best explorations of pleasure and consent in kink I have ever read.

Alex Dimitrov’s “Impermanence” wants, wants, and then wants some more. “Amid Tensions on the Korean Peninsula,” Franny Choi’s poem about war, survival, and collective memory, is nothing short of a formal marvel. Eileen Myles is having the time of their life in “To Love.” Eloghosa Osunde’s “Good Boy,” for which she received the 2021 Plimpton Prize, completely altered my understanding of what fiction can do. Take the opening as case in point:

I’ve always had a problem with introductions. To me, they don’t matter. It’s either you know me or you don’t—you get? If you don’t, the main thing you need to know is that I am a hustler through and through. I’m that guy that gets shit done. Simple. Kick me out of the house at fifteen—a barged-in-on secret behind me, a heartbreak falling into my shin as I walk—and watch me grow some real useful muscles. Watch me learn how to play all the necessary games, good and ungood; watch me learn how to notice red eyes, how to figure out when to squat and bite the road’s shoulder with all my might. Watch me learn why a good knife (and not just any type of good, but the moral-less kind, the fatherlike kind) is necessary when you’re sleeping under a bridge. Just a week after that, watch me swear on my own destiny and insist to the God who made me that I’m bigger than that lesson now; then watch my ori align. Watch me walk from that cursed bridge a free man and learn how to really make money between age damaged and age twenty-two; watch me pay the streets what I owe in blood and notes (up front, no installments); watch me never lack where to sleep again.

The story blows my mind each and every time I return to it.

Over on the Daily, Bryan Washington writes about his experience at New Orleans Pride and other events across the South in “Proud, Prouder, Proudest.” Yelena Moskovich discusses her search for a lesbian canon, and Matthew H. Birkhold examines The Third Sex, a little-known German publication that was most likely the first magazine to focus on trans issues.

This many-limbed corpus is strikingly diverse—in fact, “queer writers” proves to be a relatively loose unifying factor when the work itself is held up side by side. Although I wrote this for Pride, I truly believe that it’s vital to read queer literature not just during June, but every month of the year. This weekend, in celebration of New York City Pride, check out the above works in the Review, along with Lou Sullivan’s diaries, Sarah Schulman’s new book on the political history of ACT UP New York, and Fred W. McDarrah’s reissued Pride: Photographs after Stonewall. Go from there. Happy Pride.

Mira Braneck is a writer from New Jersey.

The Winners of 92Y’s 2021 Discovery Poetry Contest

For close to seven decades, 92Y’s Discovery Poetry Contest has recognized the exceptional work of poets who have not yet published a first book. Many of these writers—John Ashbery, Mark Strand, Lucille Clifton, Ellen Bryant Voigt, Brigit Pegeen Kelly, Mary Jo Bang, and Solmaz Sharif, among many others—have gone on to become leading voices in their generations.

This year’s competition received close to a thousand submissions, which were read by preliminary judges Julia Guez and Timothy Donnelly. After much deliberating, final judges Rick Barot, Patricia Spears Jones, and Mónica de la Torre awarded this year’s prizes to Kenzie Allen, Ina Cariño, Mag Gabbert, and Alexandra Zukerman. The runners-up were Walter Ancarrow, Hannah Loeb, Dāshaun Washington, and JinJin Xu.

The four winners receive five hundred dollars, publication on The Paris Review Daily, a stay at the Ace Hotel, and a reading at 92Y’s Unterberg Poetry Center in the fall of 2021. We’re pleased to present their work below.

Kenzie Allen.

Kenzie Allen is a poet and multimodal artist and a descendant of the Oneida Nation of Wisconsin. She holds a Ph.D. in English and creative writing from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and an M.F.A. in poetry from the Helen Zell Writers’ Program at the University of Michigan. Her poems can be found in Boston Review, Narrative Magazine, and The Adroit Journal. She is the recipient of fellowships from Vermont Studio Center and the Aspen Writers’ Foundation. Born in West Texas, she currently lives and teaches in Toronto.

*

Quiet as Thunderbolts

And I kept it from you like a kill,

my name, my legacy, my shoulder

chip and the small hollow beneath

where I can be wounded. The Longhouse

I whittled to matchsticks, abalone

filling up with hair ties, Ute painted

coffee mugs and iron turtles a pan-flash

of identity, an almond eye watching

from between the white bookcases

and photographs of cities, orchards,

graves. A lonely ironing board

left to the street outside our old place,

candles I lit in Lisbon for all the women

I have loved. Animals who are no longer

with us. Animals who are no longer

ours. So much landscape I can’t

tend to, wide as a child’s face

and crumbled in drought,

rimmed in salt. I kept the Water

Lily, how Bear Clan was given

the medicines, Namegiver,

how she made me darker

with her words. The turquoise ring

and how it pleases the Spirits

to give that which has been

so admired. The sweetgrass

in my sock drawer, the exact volume

of air I can fit in my lungs and belly

as I try to swallow and breathe

its sweetness. Every bead, every

loop of every treasure necklace—

I kept porcupine quills

in my throat, I let the water drown me

every night in my river-bottom

canoe. I’ve been sleepwalking

since I got to this earth,

since they brought up the soil

and made an island, those who did not perish

in the dive. Since the island crawled

into a continent, I’ve been

shell and memory, calendar and hearth.

Ina Cariño.

Ina Cariño holds an M.F.A. in creative writing from North Carolina State University. Their poetry appears in Apogee, Wildness, Waxwing, New England Review, and Tupelo Quarterly. They are a Kundiman fellow, a recipient of a fellowship from the Vermont Studio Center, and the winner of the 2021 Alice James Award for their manuscript, Feast, which is forthcoming from Alice James Books in 2023.

*

Ancestors for Sale

Mag Gabbert.

Mag Gabbert holds a Ph.D. from Texas Tech University and an M.F.A. from the University of California at Riverside. Her essays and poems can be found in 32 Poems, Pleiades, The Massachusetts Review, Waxwing, and The Pinch. She is the author of Minml Poems, a chapbook of visual poetry and nonfiction. She’s received poetry fellowships from Idyllwild Arts and Poetry at Round Top. She teaches creative writing at Southern Methodist University and serves as the interviews editor for Underblong Journal.

*

Tattoo

At forty-three my uncle got one of the ocean on his foot,

which made it look like he was standing in the ocean.

But who could’ve imagined, once he turned forty-four,

that he’d collapse right on its shore, his chest fallen flat

as ink kept lapping against the bones attached to that

skin with its greenish-white tongues, its mouth full

of foam. And his lips lined with sand. There’s a little

black compass I have inked on my hand, a mark people

often mistake for a wedding band: a name promised,

an until-death wish, my path already set. This way

I can think about permanence as I turn toward decay.

When other awful things happen, I hear an old friend

say: there will be an/other side again, and yet I can’t

help but wonder if both sides are the same, just this one

flipped image above and below any still water’s surface

(notice the face in surface, a lake mirroring yours in it,

how it echoes ache, ache before the eyes blue away).

Scientists claim that humans are trained to find faces

in everything—the cracked windshield, a shirt’s stain,

the stopper for the drain—but they also forget to say

soil and waves will seek themselves in our skin. Grief

involve trades: Sorry I’m tide up. I’m knot okay. I still

curl over my bent legs like a seashell when I think about

my dead uncle. Or fate. Then I break down to seas/ash/

hell. The pastor says, he will always be mist. Says, now

he is hole again. But even when I imagine that pink sole

of his beneath its ocean of flesh, or his branched veins

shielding their school of silver fish, they all start to spill

out from his archway. Then ribcage. I remember how,

before he went in the grave, my uncle looked like that

ocean was being siphoned up his leg, like his whole

body was turning a shade of dolphin-sea-grey. It was

as if his calf almost became a real calf then. But now

I can’t seem to erase that one last image from my head.

Alexandra Zukerman.

Alexandra Zukerman is a poet and photographer. Originally from New York, she has spent time in many places meaningful to her. She studied at Harvard and completed an M.F.A. at NYU this spring, where she also taught undergraduate courses. She is currently at work on her first manuscript of poems.

*

Quest 8

The world practices social distancing.

The virus spreads in waves.

In prison, the virus spreads in flat water.

Life goes on as normal.

Normal in prison.

Biographers always talk

about the last day. Sylvia

Plath cleaned her kitchen

and left reminders for herself.

Alan Turing bought theatre tickets

and promised to see the Webbs.

“Mrs. Dalloway said

she would buy the flowers herself.”

It turns out

the learning curve in prison

is a depressed boxspring—

It is normal in prison

to have a Bunkie.

That first visit, we wondered about

our father’s new word— He kept

using it

as though the word

nothing would mean the same thing to us.

His first Bunkie was fifty years younger.

From El Salvador, he came to this country.

El Salvador, then Ukraine, then Israel—

Time in prison is as thick as telling.

Prison is made of small stories.

They sit elbow to elbow

and pass the salt. That last visit,

we watched our father’s mouth—

He hadn’t raised his lids.

Maybe out of neglect, or

he’d found solace

on the shut

side of them.

Prisoners sink in flat water.

You don’t find air

on torture worktables

or in hospital self-assessments.

It doesn’t articulate

pain like fire or nails.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers