The Paris Review's Blog, page 112

June 7, 2021

On Sneakers

In his column Notes on Hoops, Hanif Abdurraqib revisits the golden age of basketball movies, shot by shot.

Coach Tracy Reynolds (Morris Chestnut) and Calvin (Lil Bow Wow) in Like Mike, directed by John Schultz, 2002. Photo: United Archives GmbH / Alamy Stock Photo.

1.

It is best to not get this confused: there are many ways to grow up poor. There are differences between those who have little and those who have barely anything at all, even in the same neighborhood, even on the same street, even if those differences could not be gleaned from the way a house looks on the outside or the way a yard is kept. You’d have to grow up some kinda poor to know these differences, I’d say. You’d have to grow up some kinda poor and know some people who grew up some kinda poorer than you were. Just ask the kids who admired the hustlers and the kids who had to hustle. Just ask the people who got tired of eating the same stale and boring meals and then ask the people who went to bed hungry.

When I talk about how my parents didn’t have the money to buy me cool sneakers when I was a kid, there are multiple things for the initiated and uninitiated to peep: what I’m saying is that my parents didn’t have the money to spend on anything foolish, certainly not anything costing more than a hundred dollars that served the purpose of decorating feet in the unpredictable weather of the Midwest. When I talk about how I pushed lawnmowers in the summer for sneaker cash or breathlessly lifted dense snow out of driveways in the winter, what I am also saying is that I lived in a place where enough people had spare cash to kick me a few bucks for work their kids could have done, work they absolutely could have done themselves.

As many ways as there are to grow up poor, there are just as many ways—if not more—to cloak whatever foolish and misguided shame you might have in your material circumstances. There was always a sacrifice to make in the name of cloaking oneself in some vibrant distraction or deception.

2.

To cut to the end, it turns out all Calvin Cambridge really wanted was a family, and I know—of course this is the case. Like Mike was never really all that much about basketball, I suppose. Movies with kids playing sports are only sometimes about the sport, particularly if the film involves something mystical or magical. The sport is the scaffolding, but the kid, or at least one of the kids on a team, is seeking fulfillment elsewhere. And yes, for Cambridge, this is a bit more urgent. He was in an orphanage, selling candy for an abusive overseer. The shoes were not magic when he found them, but he climbed a pole to retrieve them from a power line, there was a lightning strike, and then Michael Jordan’s old sneakers had the power of Michael Jordan himself. And while all of that is good, it does nothing to move me away from the fact that the movie is, at least in part, about loneliness, about placelessness, about wanting to pull the curtain back on a world where a kid feels worthy of being desired.

But before we go too far, it is also just a silly basketball movie about a silly pair of shoes, and let me be clear that the silly movies I love most are the basketball ones. Especially the ones that take place in the NBA and especially the ones where the league’s universe is warped—where there are made-up teams and players alongside real teams and players. Jason Kidd and Dirk Nowitzki getting in a defensive stance to stop Morris Chestnut’s drive to the rim. These are my favorite part of sports movies, but especially basketball movies. There’s something about the mechanics of basketball that makes it clear who can play and who can’t, even if they’re acting as though they can. That level of cross-universe absurdity is almost needed in a movie such as Like Mike, which relies on the trope of “kid finds an item and the item allows them to live a sports dream.” It cements the impossibility of the journey, in case you were to get any ideas.

3.

The thing is that by the time I was of an independent basketball-loving age, with fully formed memories, no one I hung around wanted to be all that much like Michael Jordan anymore. This was the end of era-one Michael Jordan and then era-two MJ—still singularly great, but a little less cool. The older siblings of my pals had posters of the cooler MJ on their walls. The MJ suspended in midair, two gold chains ascending along with him, making their way up to his open mouth, flirting with his dangling tongue, his arm cradling a basketball, his body twisted in some impossible collection of limbs. The immortal MJ in the dunk contest, adorned in shine the NBA banned years earlier. Get fly to get fly.

To be “like Mike,” in the sense of the early-nineties Gatorade ads, was to want to emulate his movements. In one commercial, a young Black child attempts a dunk, the rim miles away from where he’s going to land. The idea, at the time, was all about making Michael Jordan appear likable, relatable. I remember the commercials vaguely. I remember the song more than anything, its terribly infectious melody that I hummed in my elementary school hallways, wearing black, nondescript sneakers purchased on clearance from some place or the other.

By the time I was in middle school, by the time Michael had left and returned and remained great, though a different kind of great, everyone I knew wanted to be like Penny Hardaway, or Allen Iverson, or, occasionally, Grant Hill, but no one really wanted to be Grant Hill all that much no matter how smooth he was with the ball because if there’s one thing I know, it’s that the older kids on the block declared Grant Hill corny, and lord knows no one wants to be corny.

I have spent a lot of time in the past year meditating on how and when Michael Jordan’s relationship with coolness changed for me. He was a myth for me during the first half of his career, when my memories of him were fuzzy, until about 1993 or so. And then, when he came back, in 1995, the NBA was growing younger, even more exciting than it already was. He foiled and frustrated those younger players routinely. The Bulls were consistent roadblocks to teams like the Knicks, a beloved team in my household. I didn’t relate to this Michael Jordan as I’d related to the one airborne and festooned in gold, frozen on a Nike poster.

June 16, 1996, was Father’s Day. It was also game six of the NBA Finals. The Bulls had a chance to close out the Seattle Supersonics and win another title. I loved Gary Payton, and I loved Shawn Kemp, and so I went into the finals rooting for Seattle, even though I knew my rooting was a futile effort. They played hard, but it soon became evident that, like most teams matched up with the Bulls, they just weren’t good enough. The Bulls won that game, and I don’t remember much of it. I don’t remember how anyone played, and without looking it up, I couldn’t even tell you who the home team was.

It was Michael Jordan’s fourth title, his first since the 1993 championship, which had taken place about a month before his father, James, was murdered.

For all of the visual and aesthetic iconography around Jordan, so much of it—looking back—feels forced and sometimes overly dramatic: the flu game, when he collapsed into Scottie Pippen’s arms, for example. I have no qualms about theatrics, to be clear, especially sports theatrics. So I love every moment of it. But there is a difference between typical sports theatrics and real expressions of emotion. On Father’s Day in the locker room after winning his fourth title, Michael Jordan clutched a basketball on the floor and sobbed. Loud, heaving sobs. He looked spent, not physically, but emotionally. Running fully, publicly, into the arms of his grief. A grief that had lingered. A grief that endured, as so many different modes of grief do.

My mother wouldn’t die until almost exactly one year later. I hadn’t yet been to a funeral, though I’d heard about them. I’d seen my pals and neighbors dressed for them. I’d heard stories of people crying like this, loud and seemingly without control. But this was the first time I’d seen it up close, the first time I’d seen it on someone who, until that point, had been an immortal.

I don’t like making much about the so-called humanization of people. It’s a tired trope that has become too abstract for my liking. The Michael Jordan crying moment didn’t embed within me an understanding that he was human. Rather, it laid a framework for me to fit my large emotional self into. I was a sensitive kid. I’d cried a lot, and I would cry a lot more, and there was a time when I was ridiculed for that outside of my home, and then there was a time when the ridicule stopped. I felt, in my adolescent mind, that I owed Michael Jordan. A foolish feeling, but one I adhered to for years to come. No one could tell me shit about my big, overwhelming emotional pursuits because look at this: a man at the top of his game, his career, wept on national television and it was loud, and messy, and I am remembering now that the Chicago Bulls were the home team because when I close my eyes I can still see the large red “23” against the white fabric, trembling on Jordan’s back with every trembling cry. And that moment wasn’t about basketball for me and it certainly wasn’t about shoes (though I’m sure it didn’t help sales of the latter). And to be clear, I didn’t understand it at the time. I didn’t understand how Michael Jordan could still be sad about something that had happened three years ago. I was not even a teenager yet. I had no idea about the immense nature of grief.

I don’t remember if my mother was even watching the game. She would weave in and out of basketball with varying levels of interest. I have probably imagined her in the room with an arm around me while I watched, but I don’t think that’s real. It won’t stop me from clinging to the fantasy, but I don’t think that’s real.

4.

I am not as lucky as Calvin Cambridge, finding magical shoes by way of a dumpster. But I have found myself undertaking a new task in the past year. My sneaker collection now would be the envy of my teenage self. And I buy sneakers with the understanding that my relationship with them is complicated. I think they are beautiful and emotionally fascinating, but also foolish and a vehicle of multiple exploitations. But I own them. Too many of them, to be exact. And late last spring, I found a pair of original black and red Jordan 11s from 1996. The kind of pair MJ wore in that ’96 finals series. I got them for a great deal, from a person who had never worn them and was never going to. I watched Like Mike again, for a laugh. But through my watching, I got newly obsessed: How many real, original pairs that I could afford at the time of their release can I get now? I dove deep into finding Jordans from 2001, from 2003, from 1998, from 1995. The ones I had once circled in Eastbay catalogs left open on the table in hopes that my parents might glance at them and soften. I found pairs all over the world, never worn. I haggled and hassled and hustled and counted coins and consulted sneaker friends to make sure I wasn’t overspending. I never got as lucky as I’d hoped. A couple of pairs from ’01, a couple from ’96. The thing with sneakers this old, especially if they’ve never been worn, is that the white parts of them begin to yellow organically. The soles begin to soften over time. They require a real tenderness, from a very tactile standpoint: one must touch them gently, hold them gently, lace them up gently. I don’t gaze much at shoes as though they are art. I don’t make a whole thing out of it. But I found myself looking at these as though they were artifacts. Projecting my own past onto them, thinking about where they were when I was coveting them as a thirteen-year-old, as a sixteen-year-old.

But because I firmly believe in wearing the sneakers I purchase, I chose to wear the black and red Jordan 11s from 1996 out of the house during one of my weekly batches of errands. The soles, softened from years of inactivity, crumbled while I walked through Trader Joe’s. All before I got whatever special powers or before I unlocked whatever special magic was inside. As I walked gingerly back to my car, I figured maybe the magic was in the crumbling. The message that whispers a reminder: nothing from the past is as glorious as I remember it. If I get close enough, the memories fall apart.

5.

I remember the morning my mother died because I heard my father crying, loud sobs from his upstairs bedroom. I heard it all through the house. I remember the morning my mother died because I didn’t cry, even though I felt like I should have been crying. It made sense for me to cry and I wanted to, but I didn’t. It was months later, as I was walking home from one of the first days of school with headphones on but nothing playing in my Walkman, that I sat down on a bench and cried, uncontrollably, for what was minutes but felt like hours. I had on my first-ever pair of Jordans, which I’d purchased with money earned from doing chores and saving up my newly boosted allowance. They were caked in a light layer of dirt already. I arose, weighed down and soaked in my own sadness, with a clarity. Grief is something we carry, not something that exits.

But this is just a silly thing. About basketball. About shoes.

Hanif Abdurraqib is a poet, essayist, and cultural critic from Columbus, Ohio.

June 4, 2021

Staff Picks: Exes, Hexes, and Excellence

Joss Lake. Photo: J. Aharonov.

Part sci-fi, part fantasy, part trans Brooklynite millennial saga, Future Feeling revels in its own chaos. Joss Lake’s debut novel kicks off when Pen, a trans man who works as a dog walker, enlists his roommates, the Witch and the Stoner-Hacker, to place a hex on Aiden, a trans influencer whom Pen resents. Rather than falling on its intended target, the hex sends Blithe, an adopted Chinese trans man raised by white parents, to the Shadowlands, a dark landscape one goes to when they have “completely lost their shit.” The Rhiz, a highly elite underground queer organization, enlists Pen and Aiden to bring Blithe back from the Shadowlands, where he’s struggling emotionally with his transracial upbringing and gender transition. Am I doing the plot justice? Not really—I told you this book revels in its own chaos, and chaos and coherent narrative summary don’t tend to mix. But I love how Future Feeling lingers in the mayhem. More than linger, Lake embraces it, forgoing the neat narrative of before and after in favor of the messiness of process and becoming. Plus, this book is fun: hexes, moonlit rituals, a pet plant named Alice the Aloe, and well-placed critiques of gender, capitalism, and the alienating nature of advanced technology all abound. I’m still not sure how to classify Future Feeling—but defying neat categorization is kind of the point. —Mira Braneck

There are doubtless as many ways to write about motherhood as there are writers on the subject. Iman Mersal, whose crisp, incisive prose poems have appeared in this magazine, offers a loose and intimate instruction manual in How to Mend: Motherhood and Its Ghosts, translated from the Arabic by Robin Moger. A contribution to Kayfa ta, a series of how-to books, this pocket-size text is without agenda, reporting the thoughts passing in and out of a woman working through what an identity as mother looks like by studying photographs, keeping diary entries, footnoting staid academic essays, and composing verse. —Lauren Kane

Still from Alien on Stage, 2020, directed by Danielle Kummer and Lucy Harvey.

I have a special appreciation for amateurs. While attempting to woo my now fiancée, I signed us up for Swede Fest—a film festival for low-budget re-creations of popular movies, after the film Be Kind Rewind. We put together a cringe-worthy low-budget remake of Jurassic Park and fell in love in the process. Now, when a work of art feels amateurish, we say it has swede energy, which is another way of saying we can feel the love that went into it. The documentary Alien on Stage has major swede energy. The film follows a crew of English bus drivers who ditch their annual pantomime traditions to put together a stage adaptation of Ridley Scott’s 1979 sci-fi horror classic, Alien. The homegrown ambition, feats of low-budget engineering, and genuine passion that went into this creative undertaking are wholly inspirational, and the resulting camaraderie—onstage, backstage, in the crowd, and behind the camera—is so kinetic that you might just be moved to join the crew. Last year, my fiancée and I made our own low-budget Alien remake, so I’m admittedly biased when I tell you this is the best documentary you’ll see all year, but it has to be the best film made by and about amateurs. The word amateur is often used to mean nonprofessional, but it’s rooted in the Latin for “love.” In this sense, Alien on Stage is every bit the work of amateurs. Feel the swede energy and show them some love—streaming until June 20 with the San Francisco Documentary Film Festival. —Christopher Notarnicola

Chet’la Sebree’s Field Study is a book in fragments, “an investigation,” she writes, “of the effects of the world on one woman’s desire and identity formation.” In a series of meditations drawing from her own relationship history as well as tweets, observations, and quotes from literary and pop culture figures including Audre Lorde, Lupita Nyong’o, Tressie McMillan Cottom, Maggie Nelson, and others, Sebree analyzes desire, interracial relationships, and what it means to be a Black woman in the contemporary U.S. “Am I a tourist to my own existence?” she wonders as she grapples with the lines between history and the present day, fiction and reality. How should the artist approach rendering her own life in a work of art? “In the failing light of summer, forgive me,” Sebree writes poignantly toward the end, addressing her unnamed former lovers. “I’ve cannibalized you.” —Rhian Sasseen

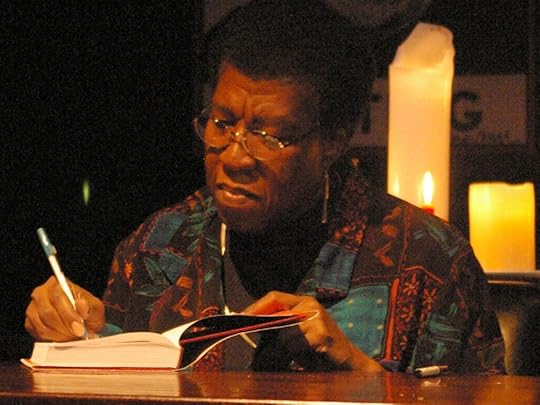

This week, Naomi Osaka was in the news for a series of reasons no one can quite agree on. It is safe to say she is one of the most talented athletes alive today; that she knows it seems to have become a problem. Those on earth who are more talented, more driven, and more self-defined than the rest of us are often given a confusing welcome. The memoir Dear Senthuran, Akwaeke Emezi’s fourth book in as many years, is, among other things, a chronicle of the kind of ambivalence with which most of us react to the extraordinary. Structurally, it is a thing of great beauty. Each chapter is a letter. Some recipients reappear; some don’t. The letters form a mesmerizing, page-turning account of Emezi’s feelings about going from being a relatively unknown M.F.A. student to a celebrated writer—as of this week, they appeared on the cover of Time magazine, and they signed a seven-figure deal with Amazon Studios earlier this spring. Their identity as an embodied nonhuman entity/an ogbanje/a deity’s child interrupts certain social expectations, but Emezi’s talent interrupts them all. Emezi writes magnetically about encountering rejection from their M.F.A. cohort upon announcing that they had landed an agent and a book deal (“the awkwardness … their lack of excitement for me even though this was the thing we are all here for, all supposed to be helping each other toward”) and about their family’s desire to hear that while “big things were happening around me, flashy and powerful, the kind of things that make other people happy … that I wanted them there, that I wasn’t leaving them behind, that I was still available, I was still accessible.” There are a lot of stories in this memoir—it is also a book about suicide, love, and houses—but this week I am considering how Dear Senthuran is about powerful excellence, especially the excellence that appears in bodies that aren’t white and aren’t male. Emezi is changing the world and our reaction to this kind of power. They know there are others who have it—“people can do such spectacular things if you forget to tell them it’s impossible”—and maybe the world is almost ready. —Julia Berick

Akwaeke Emezi. Photo: © Kathleen Bomani.

Poets on Couches: John Murillo and Nicole Sealey Read Anne Waldman

The second series of Poets on Couches continues with John Murillo and Nicole Sealey reading Anne Waldman’s poem “How to Write.” In these videograms, poets read and discuss the poems getting them through these strange times—broadcasting straight from their couches to yours. These readings bring intimacy into our spaces of isolation, both through the affinity of poetry and through the warmth of being able to speak to each other across the distances.

“How to Write”

by Anne Waldman

Issue no. 45, Winter 1968

Perhaps I’m kidding myself about

the life I lead

Sometimes I feel I’m dying

like a lot of things I see around me

Then I turn on the TV and understand

that everything must still be moving

Music, for example, and I rush outside

around the corner to a concert

It’s so easy

Everything accessible from where I

happen to live at the moment

Things like rock concerts not too many trees on 2nd Avenue

Once, on the Sixth Avenue bus

I got a sudden sensation

I had been alive before

That I was a man at some other time

Traveling

You would think this strange if you were a woman

If I were a man right now I’d be getting out of the draft

but I think I’d want to be a poet too

Which simply means alive, awake and digging everything

Even that which makes me sick and want to die

I don’t really, you know

I just don’t want to be conscious sometimes

because when you’re conscious in the ordinary way

you have to think about yourself a lot

Dull thoughts like what am I doing ?

Uptown in a large crowd I want to sit down and cry

because everything is simple and complicated

all at once

Everyone has this feeling

Even people downtown

It is very basic to the way we are

which is why I can say “we”

A lot of drugs can change you if you want

because you too are made of what drugs are made of

In fact you are just a bundle of drugs

when you come right down to it

I don’t want to go into it

but you’ll see what I mean when you catch on

That’s not meant to sound snotty

I’m open to whatever comes along

This is the feeling I get before I take a plane

Then everything’s the same afterward anyway

All into one space and here I am again

alive still, same worries on my mind

The thing is don’t worry!

You are doing what you have to what you can

You hear from your friends

They let you know what’s happening in California, Iowa

Vermont and other places about the globe

They take you out of your little room

just like the newspapers or the news

or the man you live with

and put you in a much larger room

one in which you are in constant motion around the clock

John Murillo is the author, most recently, of Kontemporary Amerikan Poetry, winner of the Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award.

Nicole Sealey is the author of Ordinary Beast and received the Rome Prize. Her poem “Pages 5–8” appeared in the Fall 2020 issue.

June 3, 2021

The Secret Identity of Janis Jerome

Thomas Pollock Anshutz, Woman in an Interior Reading, n.d., oil on canvas, 16 1/4 x 23 1/4”. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

During one of the texting sessions that became our habit over the period I now think of as both late and early in our relationship, my mother revealed the existence of someone named Janis Jerome. The context of our exchange was my need for context: two years earlier I had set out to capture the terms of our estrangement, to build a frame so fierce and broad it might finally hold us both.

If not an opponent to the cause, my mother was a wily associate—allied in theory but elusive by nature, inclined to defy my or any immuring scheme. The channel that opened between us across her sixties and my thirties spanned two countries and bypassed decades of stalled communication. We pinged and texted our way into daily contact, a viable frequency. This was its own miracle, a combined feat of time, technology, and pent-up need. As she neared seventy, the repeated veering of our habitually light, patter-driven exchanges into fraught, personal territory was my doing, a response to a new and unnameable threat. Perhaps she had felt it, too: that there may not be time to know all the people I had been in her absence; that I might never meet the many versions of her I had discounted or failed to recognize. That we wouldn’t tell the most important stories.

If our withholding was mutual, it was part of a tradition I took from her, and she from her mother. I sought a context for this, too, the narrative affliction so common to maternal lines and so little changed by a century of marked progress. If anything, the supposed release from pastlessness and isolation that kept a woman from imagining herself as universal—worthy of story and its ritual transmission—had further troubled a primary bond. “Mother-daughter relationships are generally catastrophic,” Simone de Beauvoir once observed. This we knew; this everyone knows. It has been understood, too, that the general catastrophe of mother-daughter relationships makes them less and not more interesting, unfit for inscription. As much as anyone, I have manifested this view. For the better part of my life, only contemplating our relationship interested me less than contemplation of my mother. As a writer the subject appeared fatal. Our catastrophe represented an absence of imagination and vitality; it was where story went to die. By the time my mother introduced me to Janis Jerome, however, early in 2016, something had shifted. Unbeknownst to her, I had spent the previous two years struggling to articulate the terms of a new project—about legacy, feminism, and failure, questions I sought to examine and refract through the prism of mother-daughter relations. In my half conception of it, the project would rest in the shadow of my mother’s mortality, colored and inflected as I saw fit by the vague, theoretical specter of her loss. It would deploy specific elements of her life—our lives—to larger, abstract ends. As a matter of inability as much as instinct, it would privilege argument over plot, ideas over narrative, something else over straight memoir. When an editor asked that summer why I wanted to write such a book, I made a comment about it being the hardest thing I could do at that moment, like I had any idea.

Past seventy when she shrugged off mother-daughter affairs, Beauvoir refused to identify as a feminist for most of her life. As a product of similar if not the same confusions, I have found comfort in this. I see a heritage in it, however twisted, and heritage is what I seek. I had not turned to my mother for such things; she seemed to prefer it that way. Like her, I learned by example and lack of example not to look to the women closest to me for a sense of who and how to be, what was possible in life. Unlike her, I had a mother who had lived out a neoclassical epic of self-determination: seventies housewife turned M.B.A. turned CEO. Still, her example proved dim, her transformations hidden, their terms boggled. This appeared to me by design: the breach between us had not been a cost of her emancipation but its requirement. As a child I stopped seeing her clearly; in adolescence I stopped wanting to. I charged forth into an old and new kind of catastrophe: despite a near-complete failure to know my mother, my own becoming was both guided and thwarted by a determined effort not to become her.

Standing on the far side of that calamity, I began coaxing our relationship toward disclosure, background, dimension—a shared line of analysis. It was my habit and my handicap: inquiry as an act of love. If she saw it that way, my mother remained a slippery subject, too cool-minded and wildly individual to suffer grand unifying theories, or to share space with the dominant social movement of her time. I respected her resistance even as I weighed its consequence. Early in this process, her lack of interest in feminism interested me most: What was more feminist, I thought, than the purity of its confusion? I found her attitude perverse but not unfamiliar. I had sent at least one of my selves into the shadow sisterhood made up of women who learn to live for themselves, pretending a discrete existence, hoarding their petty freedoms.

I may have met my mother in that lonely place. I would not have known.

*

My mother mentioned Janis Jerome as though I might recognize the name. She had popped up that early spring evening—texting, per usual—with questions about that class, my puking dog, Mercy, and an outstanding payment for one of the contract gigs I used to slap together a living. When I complained, again, about the missing money, she urged me, again, to follow up, keep on it. She took a reliable interest in career and financial concerns, but I recognized her advice as an act of mothering by the way it reached one arm back toward the woman who had had to figure these things out for herself. Be persistent until you understand what’s happening, she went on.

When I started at Canada Trust

almost 40 years ago, they were

underpaying me

I pointed it out and my boss

accused me of thinking only

about money

Can you imagine

It was their mistake!!!!!

It made me furious

So wrong

How did you figure out they

were underpaying you?

I did the math

My salary was supposed to be

10,500 and they were basing

deductions on 10,000

I had the letter!

1977

But I was made to feel small for

asking

Right

It’s a thing with me

*

In the beginning, they made her a clown. They had her bake cakes. At thirty-three, with a six-year-old and a toddler at home, she had answered an ad in the local PennySaver: assistant coordinator of branch promotions for a national trust company that functioned as a bank. The job was her entry into full-time work. On Saturday mornings she would blow balloons and hang streamers while standing on check-signing podiums. She orchestrated “birthday” parties for branches opening around the city. She baked sheet cakes in our kitchen, wrapping nickels in foil and dropping them in batter-filled pans. Sometimes the cake paid a penny per slice. She would dress in a clown costume: rainbow wig, painted face, floppy shoes. The idea, I suppose, was to make customers feel at home, to promote the bank as another member of the family, with occasions to celebrate and a mother willing to make a fool of herself.

She felt too old for grunt work, to be hustling between warehouses and wearing jeans on the job. Within a year she had agitated for a promotion to product communications and a desk in the head office. I have no memory of my mother the clown. From this period I recall only the texture of white crusted icing giving way, the crumble of burnt yellow cake and beguiling tang of money in my mouth.

It was a thing with her: being underpaid, undervalued, undersold. Part of a new generation of girls educated as a matter of course, she had spent four years submerged in the grammar of a failing language, studying the epics and great myths. She earned a classics degree in 1966 and entered an unreconstructed world, marrying three months after graduation and picking up teaching work where she could find it. Five years, a first home, and one baby later, it appeared she might repeat the course of her own mother’s life: raising children, following her husband’s career, adding tick after tick to a thousand-page cookbook. She feared channeling her mother in other ways: a darkness visited. Sitting in her perfect new dining room with her brilliant husband and precious baby, she would fall to sobbing. But this was hormones, stress, exhaustion. This was not her mother’s life.

Earlier that same year, an event advertised as a “dialogue on women’s liberation” took place in New York City. Germaine Greer, Diana Trilling, and two other women joined Norman Mailer at Manhattan’s Town Hall for a much-anticipated debate. D. A. Pennebaker leaped through the aisles, collecting footage his codirector, Chris Hegedus, would eventually help shape into the 1979 documentary Town Bloody Hall. Gloria Steinem and Kate Millett had declined to join the panel. Adrienne Rich, Elizabeth Hardwick, and Susan Sontag sat in the audience. Greer, then thirty-two, gave a dazzling performance, dispatching Mailer with ease. He was made to play the glib, shabby fool; she emerged as a new kind of empress.

Only one moment rattled Greer’s command. Handed the mic where he sat in the audience, the poet John Hollander began by paraphrasing the first half of an Oscar Wilde quip: “All women come to resemble their mothers—that is their tragedy.” From there he asked Greer “how the transformations you envisage [for women] might result in a transformation of that theatrical down-curve.” Visibly irritated, Greer dismissed the question. “I can only say that I don’t resemble my mother at all,” she replied, “and [the question is] based in a false premise.” Diana Trilling, then sixty-five, filled the awkward, intervening silence. In fact she thought it a marvelous question, with far-reaching implications. “Who will a daughter identify with if not her mother?” Trilling wondered. “If women are not to grow by identification with their mothers, what are they to grow by?”

When, at thirty-six, my mother decided to leave Canada Trust and pursue a business degree, her boss jeered. Who did she think she was? He stood in her office doorway at the close of her last day, arms folded. Even with an M.B.A., he told her, you might find yourself back in your kitchen, eating bonbons.

She had also applied to law school. A professional income was the goal, enough to survive on her own if need be. At thirty she feared the marriage at the center of her world was beginning to unmoor. The sense of being undervalued as a partner crushed her before it made her furious. She would rise, still married but divided from that self, well-protected by a fat salary and her own place in the world. The law school’s rejection letter settled it: she would get an M.B.A.

Business schools were growing commodities just then, the new sure thing. Their share of total graduate program enrollments nearly doubled between 1975 and 1985. You might call it a movement, a dazzling mesh of systems, ideas, and aims; a culture unto itself, resolved in its vision of the value, order, and operation of things. My mother understood both her world and the wider one to be changing, and demanding change in turn. What was a woman to grow by? Who could even pretend to know? It was necessary—basic, urgent—simply to grow.

No part of this directive drew her closer to the thing called feminism. From my mother’s vantage, the movement then at hand was chaotic, excessive—opposite the secure, empowered, self-sustaining existence she sought. Its mission was overwrought, ill-defined, its promise too diffuse. Feminist identity was limiting, more pigeonhole than portal. Above all, it seemed to her, a feminist was an imprecise thing to be. Radicalized on first contact with a male-dominated profession, even as she seeded her independence, my mother failed to see what all those shouting women in bigger cities had to do with her.

One of a handful of women in her section of sixty-some M.B.A. students, in the program’s early months she panicked. The business school’s acceptance letter had expressed concern over her high school math transcripts, recommending a summer prep course. Management science gave her nightmares. When her economics professor made sadistic work of handing back test results, she would fume: I’ve got a house, a car, a husband, two kids—why am I taking this shit? Anger bore her down at her desk, each night and every weekend. By the second semester she was acing exams and collecting scholarship checks.

Midway through the program, she was hired as a financial analyst at a life insurance firm. She wore skirt-suits, not jeans, to her new office. She convinced a florist to waive delivery fees for a standing order, letting people wonder who sent the weekly bouquets. Fresh flowers on the desk, she thought, seemed like a female-executive kind of vibe. After a year on the job, shortly after her graduation, she was assigned to train a new hire, a man with the same title and position as her but no M.B.A. Asked to review an internal budget, she discovered this new hire was making a lot more money than she did. She went to her boss, then to HR, asking for parity. Both times the answer was no.

As we texted, my mother continued filling in the details of a story she’d never told me: another job came up, consulting work—well-paid but outside her domain. It was also in Toronto, a two-hour drive from our home in London, Ontario. Aware of my mother’s unhappiness at the firm, a visiting consultant had floated the offer. “Sounds tricky,” I wrote her. “Do you still know him?”

It was tricky

I do still know him

He certainly changed your life

He put the opportunity in front

of me

Do you remember I mentioned

Janis Jerome?

No

There’s a business case about

that whole story

It’s called Janis Jerome

But it’s me

*

How much had gone missing between us? To what version of me had she introduced this other version of her? I spewed questions. She made clipped replies. We kept doubling back over each other. A former professor of hers had written up my mother’s signal career decision as a business case: Beginning in the mid-’80s, M.B.A. students at her alma mater considered the facts and decided whether “Janis Jerome” should leave her family and take the better job. A parallel case describes “Jack Jerome,” whose situation varied from Janis’s only in first name and gender pronoun. When they teach Jack, everyone votes for him to move for the great opportunity, she told me. When they teach Janis, they don’t think she should go.

But what’s the point of the exercise? Do schools still teach it? Where can I find it?

“I think the case was sold to Harvard,” she wrote.

“Google it.”

*

I did google it, and within a few clicks had purchased “Janis Jerome” from the Harvard Business Review, seven pages for $8.95. An M.B.A. pedagogical tool, business or practice cases often present real or lightly fictionalized scenarios to illustrate best and worst practices, elicit discussion, incite debate. “Janis Jerome” presents my mother’s dilemma with alterations to certain identifying details. Some minor edits have been made since 1984, notably to update the salary numbers at stake, but most of the case remains as it was. Written in high narrative style, it opens with Janis at a coffee shop, “scribbling furiously on a pad of paper” as she waits for her sister, Denise. We learn that forty-year-old Janis and her medical researcher husband, David, live in Montreal. A mother of three, Janis “would have described herself as having had a pretty normal childhood.” A personal history unfolds over two pages: Janis the consummate student, then young bride and mother; Janis the devout but bored housewife, deciding to enter financial services and discovering that she is not content to simply fill a job. Janis grows hungry, forever wanting more, “more responsibility, more challenge, more recognition, more advancement.” The case presents Janis’s drive and perseverance as functions of her nature: high-achieving, competitive, a workhorse and born leader.

On the advice of a vice president at the bank where she works (“It’s the MBAs and CFAs who have the fast track now,” he tells her), “depressed but determined,” Janis decides to go to business school. She tells David she’s done her bit for the family, it’s her turn now. Bewildered but ultimately supportive, David has “little idea what had happened to change [her] outlook on life.” Janis worries about her age and about being surrounded by people with more exposure to the business world. The case makes no mention of how she feels joining the program’s single-digit percentage of women.

Early on, Janis can’t keep up. Nothing makes sense. David is miserable and her youngest daughter cries a lot, “claiming that Mommy [doesn’t] love her anymore.” Janis works late at the university library evenings and weekends. Soon she is tutoring other students. By the second year she is confident and in control. The same pattern plays out in her postgraduate life: fear and struggle followed by mastery and success.

By the time the economist “without much experience in business, no business degree, and little knowledge of the company’s operations” joins her department, Janis is bored with her post-M.B.A. job. She trains the economist—referred to as “this new person,” “this newcomer,” and “the new hire”—then discovers a nearly 50 percent discrepancy in their pay. A single pronoun in the following paragraph betrays the economist’s gender: HR tells Janis “it was necessary to offer him a high salary because of the difficulty attracting financial services executives.” Janis comes to believe the company is underpaying her—“relative to this newcomer”—because they saw little chance of a woman with a young family relocating for a better job.

Five pages in, the case returns to Janis scribbling in a café, ready to unload on her sister the pros and cons of the decision at hand: a job offer with an Ottawa consulting firm. Topping the pros list is the “terrific” money, almost double what she makes in Montreal. Although consulting doesn’t excite Janis, she likes her prospective new boss and sees opportunity to move ahead. The whole thing, Janis tells her sister, “represents a major upward movement in recognizing my worth.” Denise is skeptical: Where would she live, what would it cost? Did Janis really expect David to give up his work and follow her? What about the kids?

“You know, it’s funny. I love the children,” Janis tells Denise. “But I see very little of them now … I know that I’ll miss seeing them, and I won’t be there sometimes when they need me. But there will be the weekends. Actually, I’ll probably end up spending more time with them at the weekends than I do now! I think that I’ve been in the office the last three Sundays!” Besides, it might be even worse for the kids if she stays, stagnates, never realizes her potential. “Wouldn’t I be bitter?” Janis wonders. “And what kind of role model would I be? Wouldn’t it be good for them to see their mother as a successful, independent individual rather than as someone tied to her [crappy] job because of family?”

Making its classroom debut in the mid-’80s, “ Janis Jerome” was devised as a primer on the concept of “fit,” the influence on performance and satisfaction of the interplay between an individual’s characteristics, those of her job, and the circumstances of her life. It was also intended to prompt discussion of dual-career families, navigating career crossroads, and the role of HR in better managing high-value employees. Although the case treats it as incidental, Janis’s gender dominated class discussions. Sitting in the same rooms in which my mother had studied a few years before, a majority of M.B.A. students were disgusted by Janis Jerome. She was out of line and out of control, a “hysterical selfish bitch,” wrote one student, “who doesn’t know what she wants.” Splitting the vitriolic difference, another student described Janis as “self centered with high power needs,” a woman “who knows exactly what she wants.”

In addition to asking whether Janis should take the job, a worksheet asks students to predict, using a four-point scale, whether Janis Jerome will be successful in her career, in marriage, and as a parent. Finally, they are asked to indicate their feelings about her. Where does she fall on a seven-point scale between selfish and sharing? Cold and warm? Submissive and dominant? Bad spouse and good spouse? Caring and uncaring? Ambitious and unambitious? Good parent and poor parent? Shortly after introducing the case study, its coauthors reimagined the exercise to harness the extremity of student reactions. They changed Janis to Jack and began teaching the two cases in parallel: two sections of the program went home with Janis, two with Jack—each group unaware of the other. The next day all four sections would gather to share their responses.

The contrast stunned faculty: Janis was a cold, calculating, self-involved bitch; Jack was an ambitious guy with a difficult problem. Janis should stay where she is, lower her expectations, be happy with what she’s got. Having changed course on the cusp of middle age, Jack seemed poised for a professional breakthrough. And bravo to that: what’s best for Jack is by definition best for his family.

After a first sprint through “Janis Jerome,” I read and reread. The layout is simple and—despite a glut of Britishisms and exclamation points—the language plain. If the facts were clear enough, the story kept slipping out of view. It was a familiar sensation, a sort of narrative blindness that focused me on the margins, the things left out. I associate this feeling most with my mother, whose elisions had beguiled me long before her story did. That “Janis Jerome” rests so fully on omission, I thought, helps explain a determinedly private woman’s agreement to dress her life in a wig and funny nose and offer it up for judgment. If the situation is complex, its framing is clean and context-free, a matter of variables and outcomes, success and satisfaction ranked on a numeric scale. The case reduces an existential, gendered dilemma to a purely professional, genderless one. A broader version of this transformative promise had drawn my mother into the world of business. She mastered its concrete terms and structuring principles with what must have been tremendous relief. Told in a different language—the bland jargon of marketing clichés—its stories describe a realm of knowable systems and achievable goals. “Janis Jerome” was designed to be one of them.

My mother didn’t imagine the exercise jumping its rails. The invention of a male twin surprised her. Though it elided the discrimination that had marked her early career and helped change the course of her life, “Janis Jerome” wound up telling a story of gender bias. In 1989, the study’s coauthors published “Confronting Sex Role Stereotypes: The Janis/Jack Jerome Cases,” a paper that describes early reactions to the case and presents data from a more recent Janis/Jack Jerome exercise involving 224 M.B.A. students. The 1989 respondents were more encouraging of Janis, less ruthless in their appraisal. Calling the later results counterintuitive, one of the paper’s authors told me they may have been tied to the growing number of women in the program across the late eighties, the school’s increasingly rigorous antidiscrimination policies, and the corresponding tendency of male students to self-censor.

All down the line, my mother turned down invitations to visit the classes debating her life. The 1989 respondents got an update to the case: the real Janis took the consulting job but was fired after one year due to “lack of person-job fit.” She got another job without much delay, they learned—along with a 50 percent salary bump—and had achieved her goal of vice presidency of a major financial services company within five years of earning her M.B.A. “Her marriage is intact,” they were told, “however she finds it difficult to leave her children on Sunday evenings.”

It is, of course, the case’s most conspicuous gap: What happened to Janis between the ages of eighteen and thirty-six? Where had her fearsome ambition hidden itself? How are we to understand its sudden reanimation? Janis’s marriage is a blank space. The case depicts David as both tolerant and priggish. He agrees to become the primary caregiver and helps with tuition but finds the business world trivial, treating Janis’s M.B.A. friends with “impatience or contempt.” The case concludes with Denise’s perspective: worried about her sister, she wonders how she can help with this decision. Then comes a vague note of duplicity, the suggestion that even those closest to Janis don’t know her heart. Having spoken to David in recent months, the final sentence reads, it was clear to Denise “that Janis announcing that she would be taking a job in Ottawa would come as a tremendous surprise to him.”

My mother was already gone when she clipped a 1985 op-ed titled “Women Must Focus on the Big Dream.” Written by Kati Marton for the New York Times, the piece suggests women “aren’t doing nearly enough to combat” a post-second-wave resurgence of sexism. Marton urges women to bend the tricks of men to suit their own needs: “One of these things is self-centeredness. To our detriment, we have grossly underrated this quality. By self-centeredness, I mean learning to isolate a goal—something you want so badly everything else pales in comparison … Women must learn to focus on their dreams at the expense of other, lesser commitments.” My mother glued the article to a sheet of 8.5 x 11 paper, filed it carefully, and transported it from home to home over the next thirty years. “We must banish forever the notion that ambition is unfeminine,” Marton writes. “Ambition is a sign of self-respect. It carries no gender connection of any sort.”

When my mother announced she was leaving the insurance firm—and London, Ontario—her boss and his boss invited her to breakfast. She was thrilled. She imagined the extension of respect and congratulations, her good-faith induction as a peer. Instead, the boss’s boss seethed, berated, warned of her mistake. They didn’t want her to go but offered no reason to stay. It was the last time she bothered to ask twice for equity, the raise, or a big promotion. From then on she saw the signs and simply left, kept moving. No one ever tried to stop her.

The boss’s boss, an American, had ordered the steak. He wore a massive school ring with a blood-colored stone. My mother trained her eyes on it and waited for the meal to end.

Michelle Orange is author of the essay collection This Is Running for Your Life, which was named a best book of 2013 by The New Yorker. Her writing has appeared in The New Yorker, Harper’s, the New York Times, Slate, Bookforum, The Nation, and many other outlets. A contributing editor and columnist for the Virginia Quarterly Review, she is a faculty mentor in the graduate writing program at Goucher College and an adjunct assistant professor of writing at Columbia University.

Excerpted from Pure Flame , by Michelle Orange. Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, June 1, 2021. Copyright © 2021 by Michelle Orange. All rights reserved.

June 2, 2021

History Is the Throbbing Pulse: An Interview with Doireann Ní Ghríofa

Photo: Bríd O’Donovan.

In the work of the Irish writer Doireann Ní Ghríofa, history is amorphous, a living thing that frequently bleeds into or interrupts the lives of those in the present day. “The past has come apart / events are vagueing,” reads the Mina Loy epigraph that begins Ní Ghríofa’s sixth collection of poetry, To Star the Dark , published earlier this year. In A Ghost in the Throat , a hybrid of autofiction and essay first published by Dublin’s Tramp Press and out this week in the U.S. from Biblioasis, she writes, “To spend such long periods facing the texts of the past can be dizzying, and it is not always a voyage of reason; the longer one pursues the past, the more unusual the coincidences one observes.”

A Ghost in the Throat served as my introduction to Ní Ghríofa’s writing, and it is a work I have returned to repeatedly over the months since I initially encountered it, mulling over its questions of history, motherhood, obsession, and the porousness of time, place, and identity. The book twines together Ní Ghríofa’s harrowing experience following the birth and near loss of her fourth child with the life of Eibhlín Dubh Ní Chonaill, an eighteenth-century Irish noblewoman who, upon discovering her husband’s murdered body, drank handfuls of his blood and composed an extraordinary poem lamenting his loss. “When we first met,” writes Ní Ghríofa, “I was a child, and she had been dead for centuries.” What follows is a tale of love across eras, as Ní Ghríofa painstakingly devotes herself to researching the overlooked pieces of Ní Chonaill’s life and translating her “Caoineadh Airt Uí Laoghaire.” The poem appears in its entirety at the book’s end, translated from the Irish by Ní Ghríofa herself.

The following conversation happened over Zoom in early April from my living room in Brooklyn and Ní Ghríofa’s home in Cork. Even through the screen, Ní Ghríofa is a warm and inviting presence, leaping up frequently to grab books from the stuffed shelves behind her and reading snatches of poetry aloud to illustrate her points. At the time, Ireland was in the midst of its fourth month in severe lockdown due to the ongoing COVID-19 crisis while New York was beginning to announce its vaccination process. Since then, both the U.S. and Irish governments have eased restrictions, and as time moves forward, it is strange to think that this moment of global crisis and fear is, for some parts of the world, beginning to vague into history, too.

INTERVIEWER

A Ghost in the Throat is your first book-length work of prose. Why did you choose prose specifically for this work?

DOIREANN NÍ GHRÍOFA

I suppose I feel as though the form chose me. When I reflect on the path to writing this book in terms of craft, I’m struck by how often I felt driven by the book itself rather than vice versa. I felt as though the book were showing me the form it needed to be in, and because this is my first work of prose, that was very unfamiliar to me. There were points in the process where I felt as though I should be more in control, but anytime I tried to fight against that sense of a natural unfolding, the process very quickly taught me that resisting was a mistake. The book became itself when I was able to relinquish that sense of control. I know how frustrating it is, as a writer, to read interviews where people articulate their process like that. “This character just wanted to be who they were”—it can be irritating to hear authors speak like that, and yet, this is simply the truth of this book’s becoming. It insisted on itself.

INTERVIEWER

It sounds almost like the book possessed you, in a way.

NÍ GHRÍOFA

A little bit. I’m always a little uncertain how open I can be about how strange and disorientating the process was, because it does sound strange when I say it out loud. But it all felt far less strange when I was in the grip of it. This book insisted on itself with a real force, and there were times when I felt almost powerless in the face of it. I have the sense that that’s a rare experience, and I think I’m probably very fortunate that my first book of prose came to me in this way.

INTERVIEWER

How long of a process was it?

NÍ GHRÍOFA

I tend to have a number of works that I’m focused on at any one time, so I was working on A Ghost in the Throat over the same years that I was working on my latest poetry book, To Star the Dark. Because I was working on both books side by side, it’s difficult to say precisely how much time it took me to write A Ghost in the Throat. Whenever I was encountering a difficulty with one book, I would swerve into the other. So they were written in parallel. I find that way of working very satisfying.

INTERVIEWER

In both books, the boundaries of history blur into real life—the new poetry collection begins with that Mina Loy quote, and there’s also the poem in which you’re looking at the photograph of the girl in 1888 and you write, “Her hand exists only in pixels now, this girl / who arrives by optic nerve to live a while / in my mind.” What do you feel is the impact of history on your work?

NÍ GHRÍOFA

I feel like it’s only as we progress through a life in art, or a life in literature, that we begin to understand what our core concerns are, and history is the throbbing pulse of my work as an artist. In all of my books, in all of my poems, I return again and again to our sense of the past and what questions the past is asking of us, and the ways in which we attempt to answer those questions, just by being who we are in the environments we’re born to. I think that’s maybe why that line of Mina Loy’s moved me so much—“the past has come apart / events are vagueing”—because I feel that sense of fracture, too, the mosaic of the past and the sharp edges of it, and the sense of vagueing and blurring and the ways that sometimes, history has a real immediacy to it. There’s a moment in A Ghost in the Throat when I write about how Eibhlín Dubh Ní Chonaill feels real to me—she’s as real as the dog barking behind the tall fence, or as real as the human chorus of the internet. These are things we don’t necessarily see. At a superficial level, they’re invisible to us, but we’re aware of their presence and their heft within our reality, and I guess history feels like that to me. It feels that real.

And then to grow up and live on a daily basis in a place like Ireland is to be confronted regularly with the facts of our history, with the ruins, with the brokenness and those sharp edges, with the ways people have tried to tell our history and the coherence they’ve tried to mold from it, and the ways in which we can question that inherited history and make our own sense of it. For better or worse, I never really grew out of that sense of almost childlike enthusiasm or fascination with the past. I suspect that it’s probably an ordinary part of growing up to become used to the fact that, okay, these streets in our city, many people walked these streets over many generations. You grow used to living an ordinary adult life without having those other lives interfere too much with your own mentality. But I was never really able to get used to that. It seems so strange and interesting to me that there were these other true, real lives that were lived in these same places. That, I reckon, is the soil from which my work grows, and it’s difficult to avoid such thoughts here in Ireland because you’re constantly confronted with visual reminders of the past. You walk out your door and you’re tripping over some archaeological ruin.

INTERVIEWER

There’s a lot of living history in Ireland.

NÍ GHRÍOFA

That’s exactly it. Particularly in our generation, there’s a great sense of looking at recent Irish history and the darker elements of it all, the ways in which people were controlled and treated so poorly, the institutions that were created to dominate people’s lives, the ways in which the state and religion behaved hand in hand to control people, and the ways in which that legacy is continuing now, in terms of systems like Direct Provision. These are all concerns that I think people living in contemporary Ireland are thinking about deeply as they attempt to effect real change here. It’s a long road.

INTERVIEWER

There’s also such an emphasis on women’s lived experiences in the book, and you’re very much addressing the female reader. You use the phrase “this is a female text” a few times, and you apply it to the book, to the body, to so many things.

NÍ GHRÍOFA

The first time I heard that phrase occurred as it does in the book, as I was driving my daughter away from Kilcrea Abbey, which is a place Eibhlín Dubh Ní Chonaill had spent time. This phrase, like an earworm or a pop song you hear on the radio, began to whirl around in my mind. “This is a female text.” And I didn’t initially understand what it meant. When I got home, I was compelled to write it down and begin asking myself, through the book, What is a female text?

As I look back on the book now, what I am most struck by about that refrain is the fact that it says this is a female text. The emphasis within that utterance feels key to me, because it’s a female text—it’s just one female text. There are so many different elements to lived female lives, and so many ways it feels to be female to many, many different people. So I guess all I could attempt to articulate was what it is to perceive a female text from the perspective of a middle-class, cis, white woman living in Ireland. Having written this book, I’m still eager to learn about many, many, many more iterations of how female texts may be seen, felt, lived, and interpreted.

That sense of owning the female experience, though, as it’s described within the book, is quite radical in Ireland, given that there’s deep and profound Shame, with a capital S, instilled in Irish women going back many, many decades. So the choice I made to begin and end a book with the phrase “this is a female text,” in such an unapologetic way, was kind of dangerous. I don’t regret it at all, but I hope to take it as an opportunity to spring into other understandings of what it can be to live a female life.

INTERVIEWER

That multiplicity is so present in the text, too. I’m excited to hear that you were also thinking of that multiplicity of what womanhood even is to begin with.

NÍ GHRÍOFA

You know, I think it’s interesting to carry that curiosity about multiplicity, about what it is to live a life as a woman, into the process of writing a book—to come to the end of the process and still be able to say, I don’t fully understand this.

INTERVIEWER

And in the book, you have these dichotomies—mother’s milk and blood, say, or between languages—but you’re always blurring them. There’s this translation across centuries. Could you talk about the process of translating Eibhlín Dubh Ní Chonaill’s poem? I know you’ve translated some of your own work from the Irish to English. Do you approach translation differently when it’s someone else’s writing versus your own?

NÍ GHRÍOFA

I do. They’ve proven very different, the processes that are involved in translating my own poems versus someone else’s poetry. I suppose I’m kind of in my infancy as a literary translator, as well. So far, I’ve embarked on translating only my own poems, the long Eibhlín Dubh Ní Chonaill poem that appears at the end of A Ghost in the Throat, and all the poetry of an Irish poet called Caitlín Maude. The process fascinates me, and I find the gulf between my approaches to translating my own work and translating another poet’s work quite surprising. Sometimes astonishing, to be honest, because when I’m translating my own poems, I almost take it as an opportunity to revisit a previous iteration of myself, listening really closely to what I was trying to say four years ago and then trying to say it again in the self I am now, in a different language.

I sometimes wonder whether a previous version of myself, if she could be there to witness my translation, would argue against it. In other words, I tend to be quite adventurous in the ways I try to put English on my poems in Irish. Even that phrase itself, “to put English on,” is a really Irish way of describing translation. In Irish, it would be phrased as “Béarla a chur ar,” so I’m translating directly from Irish to English as I say that—like putting the cloak of one language on another. But when I turn to translating poems by other poets, I tend to feel a very deep sense of connection, and a tension, and really profound, bone-level respect. I veer much more toward fidelity. What is fidelity, though, in literary translation?

INTERVIEWER

It’s a great question.

NÍ GHRÍOFA

We’re just getting questions upon questions here.

INTERVIEWER

Multiplicities!

NÍ GHRÍOFA

There you go. I proceed with great trepidation when I’m translating other poets’ work, and with great seriousness. Whereas when I’m translating my own poetry to English, I take chances and I leap sideways and I do a cartwheel here and there. I feel like I can allow myself those flourishes because it’s my work and I can give myself permission.

My book Lies was a dual-language publication, and there was a lot of mischief involved in my translations from Irish to English. I put in little clues for readers. There’s one poem where a time appears on a digital clock, so in one language, I make it 01:37, and in the translation on the facing page, it becomes 01:38, so those digits reveal each other in some way, and if the reader doesn’t speak both languages, there’s a hint, or a little spark, acknowledging the strange twist a poem takes as it moves from one language to another.

I tend to hide clues like that all over the place. I suppose the brief answer to your question is that when I’m translating poems by other poets, I approach them very carefully, with great seriousness, but when I’m translating my own work, I take it as an opportunity to get up to some mischief. It feels almost like a remix, sometimes, when I’m translating one of my poems. The process allows me to approach the poem all over again. And that feels quite exhilarating.

INTERVIEWER

Is there anything you’re reading now that you’re enjoying?

NÍ GHRÍOFA

I love American poetry. I came to writing when I was in my late twenties, and I learned my craft through reading, a process I recommend to anybody who can’t embark on an M.F.A. You can teach yourself to write from home, and it will be fine. I’ve done it. It’s really fine, and it’s actually an awful lot of fun, because you become attuned to voices on the page that begin to feel like they hold little fireworks for you.

Once you start to find the books you’re drawn to, you can go back to them again and again, and every time, they will hold further surprises. One book I keep on my bedside table is Lorine Niedecker’s Collected Works. I know she’s a treasured voice on your side of the Atlantic, but hardly anyone speaks about her work over here, so it has just been like diving into a cool pool. If you could see my copy, every second page is dog-eared.

So I have been reading, rereading, and re-rereading Lorine Niedecker, and the other book I love is Stay, Illusion, by Lucie Brock-Broido. It’s a really beautiful book, and funnily enough, I came across it—let me see if I wrote the date on it when I found it … yes. I found this book in August 2019, in a secondhand bookshop on Valentia Island, off the coast of Kerry, in the south of Ireland. How amazing that Lucie happened to be there, waiting for me, on the shelves.

INTERVIEWER

It was fate!

NÍ GHRÍOFA

I had come across a few of her poems online, and I loved them, so the second I saw this book I fell for it. If you were here now and we were in the same room, I would inflict several readings of her poems on you, but I’ll spare you. [laughs] There’s something about the way both of these poets use language that feels like an actual spell is being cast, and I just get so swept up in their poems that I return to them again and again. Deborah Digges as well. I love her. And I love Rita Dove and Laura Kasischke and Layli Long Soldier and Ruth Stone. There’s something really moving for me in a lot of American poetry, that I’ve learned so much from, and that I return to again and again.

Rhian Sasseen is the engagement editor of The Paris Review. Her work has appeared in 3:AM Magazine, Literary Hub, The Point, and more.

June 1, 2021

Redux: The Modest Watercolor

Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

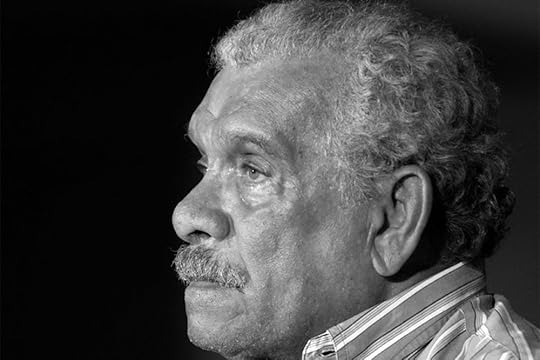

Derek Walcott, ca. 2012. Photo: Jorge Mejía Peralta.

This week at The Paris Review, we’re dabbling in watercolors. Read Derek Walcott’s Art of Poetry interview, Joy Williams’s short story “Jefferson’s Beauty,” and Michael J. Rosen’s poem “Watercolors.”

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, and poems, why not subscribe to The Paris Review? You’ll also get four new issues of the quarterly delivered straight to your door. Or, subscribe to our new bundle and receive Poets at Work for 25% off.

Derek Walcott, The Art of Poetry No. 37

Issue no. 101 (Winter 1986)

What I tried to say in Another Life is that the act of painting is not an intellectual act dictated by reason. It is an act that is swept very physically by the sensuality of the brushstroke. I’ve always felt that some kind of intellect, some kind of preordering, some kind of criticism of the thing before it is done, has always interfered with my ability to do a painting. I am in fairly continual practice. I think I’m getting adept at watercolor. I’m less mucky. I think I could do a reasonable oil painting. I could probably, if I really set out, be a fairly good painter. I can approach the sensuality. I know how it feels, but for me there is just no completion. I’m content to be a moderately good watercolorist. But I’m not content to be a moderately good poet. That’s a very different thing.

Jefferson’s Beauty

By Joy Williams

Issue no. 45 (Winter 1968)

He did not like to be kissed by his mother. He did not like to be touched at all. His body would feel stained and uncomfortable—blurred like a watercolor, no longer entirely his own.

Watercolors

By Michael J. Rosen

Issue no. 126 (Spring 1993)

Knowing that Penn had dabbled, periodically,

in paints, noting the modest watercolor

of his young, late wife, above the files,

someone has leaned a catalogue by his phone:

Gli Aquarelles di Hitler,

Palazzo Vecchio, Firenze, with a note,

Gordon—you know he flunked out of art school?

Penn glances through the booklet. München,

Standesamt, Alt-Wien Ralzenstaat, Auersberg Palais.

The captions sound portentious as their subjects:

basilicas, blocks, towers, a plaza of walls—

less loving details than things accounted for …

If you enjoyed the above, don’t forget to subscribe! In addition to four print issues per year, you’ll also receive complete digital access to our sixty-eight years’ worth of archives. Or, subscribe to our new bundle and receive Poets at Work for 25% off.

Announcing Our Summer Issue

Issue no. 237 of The Paris Review is here for your summer reading! The Summer 2021 issue, online today, features interviews with Arundhati Roy and Roz Chast; fiction by Adania Shibli and five emerging writers; the first English translation of a monologue by Vladimir Nabokov; poetry by Kaveh Akbar, George Bradley, and Ada Limón; an essay on tennis by Joy Katz; and art by Elizabeth Ibarra paired with an essay by Aimee Nezhukumatathil—and, of course, much more!

“I’m grateful for the lessons one learns from great writers, but also from imperialists, sexists, friends, lovers, oppressors, revolutionaries—everybody. Everybody has something to teach a writer,” Arundhati Roy tells managing editor and interviewer Hasan Altaf in the Art of Fiction No. 249. Roy, the author of numerous works of fiction and nonfiction—including the 1997 Booker-winning novel The God of Small Things, 2017’s The Ministry of Utmost Happiness, and the 2019 essay collection My Seditious Heart—describes the singular pleasure of losing herself in novel writing, with detours along the way to discuss her architecture-school days in New Delhi and her time spent reporting in the forests of Bastar. “I love immersing myself in the universe of a novel for years,” she says. “There is never a time when I am more alive … Being in that universe, that imperfect universe, is like being in prayer.”

“I don’t think a cartoon is just an illustration of a funny idea. The drawing style has to go along with the words, and be funny also,” Roz Chast tells Liana Finck in the Art of Comics No. 3. Chast, a longtime contributor to The New Yorker and the author of works such as 2014’s National Book Critics Circle Award–winning Can’t We Talk about Something More Pleasant?, considers how words and pictures “are conjoined twins. They’re interconnected in a primary way. When I was at art school, and a painter, I missed the words, and when I write, I miss drawing.”

Also in this issue: fiction by Anuk Arudpragasam, Camille Bordas, Lydia Conklin, Kenan Orhan, and Christina Wood, and poetry by Jennifer Barber, Charles Baudelaire, Marianne Boruch, Daisy Fried, Ishion Hutchinson, John Kinsella, Michael Klein, Jim Moore, Jesse Nathan, Barbara Tran, and Matthew Zapruder.

Enjoy! And don’t forget to subscribe for full access to both the Summer 2021 issue and our complete sixty-eight-year archive.

May 28, 2021

What Our Contributors Are Reading This Spring

William Hilton, John Keats (detail), ca. 1822, oil on canvas, 30 x 25″. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Poets can be divided into two groups: those who dutifully tortured “When I Have Fears That I May Cease to Be” in secondary school (POET = WORRIED ABOUT DYING scrawled unhelpfully in the margins) without ever giving its author a second thought, and those for whom Keats serves as spiritual teacher. To his followers, Keats is a poet’s poet, is the poet’s poet, a writer whose brief span compressed all the love, pain, and existential uncertainty of a lifetime, which the finest of his fifty-four published poems animate. He believed pain and trouble were their own education, “school[ing] an intelligence to make it a soul.” His was a rare gift, and yet his best poems weren’t earned without effort; early examples are uneven and clumsy, and for that perseverance and learning by shrewd emulation, we admire him all the more. His death at twenty-five trapped that quiddity in amber.

“When I have fears that I may cease to be”—and then he did; he died young, corroborating that fear, poised and brave in his final moments, and leaving the rest of us neurotic types (what sort of reasonable person isn’t hung up on the terror of premature death?) wringing our hands, staring into the middle distance. In this way, Keats confirms every poet’s greatest anxiety—that our fears, in truth, are sometimes justified, and that our clever poems may know more than we do.

These, of course, are my own ramblings on a figure whose life I found myself drawn to only once I had outlived him. Each year now brings me paradoxically closer and farther from Keats.

Andrew Motion’s biography of the poet is fantastically scholarly and accessible, a term that’s been overused so as to mean almost nothing. What I mean is this: on a Sunday in ninety-degree heat, you can lift the tome in your withered state, flip to a chapter at random, and find Motion guiding you with energy, intelligence, and a true sense of partaking in the marvelousness of Keats with you. Motion is wonderfully clear and direct while still making his mark on the prose at every turn, as on our understanding of the dimensions and shape of Keats’s life through his well-considered interest in the poet’s social and political circumstances. His description of Keats’s dying moments is quietly gripping, worthy of a season finale of one of the medical dramas that multiply like invasive species across American television, and yet the book goes on another twenty pages, making such partings bearable. Life goes on, even when major stars extinguish. In Keats’s case, that extinguishing served as a spark, with each subsequent generation of poets holding vigil. —Maya C. Popa

When I came across theMIND’s album Don’t Let It Go to Your Head, I had just met a deadline. I mean, I met the deadline at 3 A.M., but it still counts. Instead of going to sleep, I started listening. When I finished the album for the first time, I sat up in bed, took out my headphones, and thought, Damn—now I gotta rewrite everything. There was something about the way he observed doubt—saying everything I meant to say, but better—that not only reminded me songs are probably the one thing I’ve ever truly loved in my life, but these songs in particular really allowed me to consider the advice on the intro:

Stop.

You’re overthinking it.

Continue.

Which is probably why I ended up staying awake until nighttime came back around again.

A lot of what I was hearing mirrored what I was feeling about myself throughout the process of nit-picking at words, “[hoping] this honesty saves us.” You really gotta read these lyrics, man. “Atlas Complex”? Broke me. “Sea”? Blessed me. “Craig”? Just @ me. Bars on bars on bars on soul on heart on God. It’s like although the content is heavy in an interior way, you can still clean ya house to it. No skips. Spotless sweep. To say I’m obsessed is an understatement. —Kendra Allen

John Keeley, Among the Coal Pits, Staffordshire, n.d., watercolor, 9 1/2 x 9″. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Maybe because lockdown is a little like being buried alive in your own life, I’ve been thinking about mines and mining and miners lately. Here are three sources on what it’s like to be a miner, the art and craft and deadliness and language and silence of it, and who cares.

Brassed Off, a movie about the troubles faced by a colliery brass band upon the closure of their pit, directed by Mark Herman, 1996.

“Nottingham and the Mining Countryside,” an essay by D. H. Lawrence about his father, who was a miner, and about his own childhood in a mining town of Derbyshire, available in Geoff Dyer’s The Bad Side of Books: Selected Essays of D.H. Lawrence.

Coal Mountain Elementary, book-length poem by Mark Nowak on miners in West Virginia and in China, and how to teach children about them in an elementary school. —Anne Carson

When I’m feeling down, uninspired and going dead-eyed to the sound of my laptop’s whirring fan, I’ll seek out a live recording of a band that saw me through my nineties adolescence. These videos tend to be of shows from the band’s early years, before they were famous, or at least super famous, the VHS recordings of talents about to break out, transferred and readily available on YouTube. The one I go to most is Nirvana’s November 20, 1989, show at the venue KAPU in Linz, Austria.