The Paris Review's Blog, page 108

July 14, 2021

Re-Covered: Barbara Comyns

In Re-Covered, Lucy Scholes exhumes the out-of-print and forgotten books that shouldn’t be.

Photo: Lucy Scholes.

When I’m asked how I first became interested in out-of-print and forgotten books, my answer is always the same: it all began with Barbara Comyns. Eight years ago, Virago reissued three of the midcentury British writer’s novels—Sisters by a River (1947), Our Spoons Came from Woolworths (1950), and The Vet’s Daughter (1959)—on their Modern Classics list, and I was immediately and utterly smitten by her singular voice. With her way of combining elements of social realism, replete with Dickensian touches, with all manner of macabre gothic tropes dark enough to have been taken out of the original Grimm’s fairy tales, Comyns was quite unlike anyone I’d ever read. Angela Carter is the only writer who comes close, but Comyns’s work has none of the same feminist underpinning. I wrote a short rave review of the 2013 Virago editions for the Observer, and then I began tracking down copies of Comyns’s eight other works, only two of which were then also in print: Who Was Changed and Who Was Dead (1954), which had been reissued in the U.S. by Dorothy, a publishing project, in 2010, and The Juniper Tree (1985), which appeared as a Capuchin Classic in the UK the following year. I also began learning what I could about Comyns’s life, keen as I was to find out as much as possible about the woman behind these weird and wonderful books.

Tantalizing tidbits were scattered both in the various introductions that had been written by her admirers and friends over the years and in the novels themselves, since Comyns often fictionalized her own life. As a child, she and her siblings had been left to run wild in the hands of inattentive governesses. Comyns’s parents—a deaf and disinterested mother and a violent, alcoholic father—were too consumed with their own sparring to pay their children much attention. Comyns documents this in her debut, Sisters by a River, a book she wrote to entertain her own children when she worked as a cook and housekeeper during World War II; it was initially serialized in Lilliput magazine under the title “The Novel Nobody Will Publish.” As a young woman, she showed considerable talent as a painter; she trained at the Heatherley School of Fine Art and exhibited with the London Group. Later in life, she supported herself and her family by doing a variety of jobs that included modeling, selling antiques and classic cars, renovating houses, and breeding poodles. Perhaps most intriguing of all, though, was her connection to the infamous MI6 double agent Kim Philby, who was a colleague of Comyns’s second husband, Richard Comyns Carr, in Whitehall, and in whose Snowdonia cottage the newlyweds spent their honeymoon in 1945. Ultimately, though, rather than satisfying my curiosity, these enticing snippets of what came across as an extremely eclectic and often precarious life left me with more questions than answers.

Luckily, the task I’d set myself was greatly assisted by the generosity of Comyns’s granddaughter, Nuria, who in 2014 hosted me for a week at her and her husband’s home in Shropshire, where she let me read the diaries that Comyns kept from the mid-’60s, along with other archive material. I wrote about that week, and what I discovered, in a 2016 essay for Emily Books. Until recently, my piece was the most detailed account of Comyns’s life and work available, though I’m thrilled to report that the British academic and writer Avril Horner has recently completed a full-length biography of Comyns, a taste of which can be found in this fascinating essay, published earlier this year in the Times Literary Supplement, about Comyns’s forty-year friendship and correspondence with Graham Greene.

Because Comyns was the very first neglected writer whose work got under my skin, and in light of the fact that four of her novels have been reissued in the past year—including A Touch of Mistletoe (1967), published this week by Daunt Books—it seemed only fitting that I should write about at least one of her books in this column. Rather foolishly, I also thought this would be a relatively easy assignment. Here was a writer about whom I knew more than most people, and whose work I’d read on multiple occasions. This would be a breeze! Yet, as I discovered when I actually sat down to write, not only did I want to avoid simply regurgitating what I’d written about Comyns in the past but, more crucially, as I found myself listing just how many of her works are currently in print—eight of the eleven titles she wrote, and with six different publishers—I suddenly wasn’t sure whether she even strictly qualified as a neglected author anymore.

*

In this column, the same question comes up over and over again: If the book under consideration is so good, how did it ever fall out of print? Yet, when it came to Comyns, I found myself preoccupied by a different question entirely: What does a book or an author being “rediscovered” actually look like? Some kind of critical championing is often the starting point, but republication is the holy grail. Take Kathryn Schulz writing about William Melvin Kelley in The New Yorker, for example, which then sparked a bidding war between publishers eager to reprint his work. Or Brigid Hughes, editor of A Public Space, rediscovering and then reissuing Bette Howland’s work. Or even my own championing, this past year, of Kay Dick’s forgotten dystopian masterpiece, They, which was simultaneously rediscovered by the literary agent Becky Brown and is now being brought back into print next year.

Comyns—whose first novel was published in 1947, and whose last appeared in 1989—won accolades throughout her career, and beyond. Writing about The Vet’s Daughter, Greene—who, as Horner elucidates, both acted as a mentor for Comyns and “advanced her career whenever he could”—applauded her “strange offbeat talent … and that innocent eye which observes with childlike simplicity the most fantastic or the most ominous occurrence.” Anthony Burgess, meanwhile, was equally impressed: “Let us make no bones about it: Barbara Comyns is one of our most original talents.” And Margaret Drabble, Alan Hollinghurst, Maggie O’Farrell, and Helen Oyeyemi are just some of the other writers who’ve more recently sung her praises. “The mildly mystical approach to her subject, with its overtones of inescapable gloom, is expressed in final form in language so precise and economical,” wrote Caroline Moorehead of The Vet’s Daughter in the Times in 1981, “so pared down of all unnecessary words that it conveys a sensation of truth.” This was the first of Comyns’s titles that Virago republished in the eighties. She was the perfect fit for the publisher’s new but rapidly expanding Modern Classics list, which rescued women writers from obscurity, and for each of the five more Comyns reissues subsequently added to the list, similar laudatory reviews followed. Since then, each and every reissue of one of Comyns’s novels has heralded a joyous resurgence of interest in her work. I myself confidently declared her “a neglected genius” in 2013; three years later, given further room to elaborate in my Emily Books piece, I called her “a writer lost in time … ripe for rediscovery.” Did it surprise me to see this exact same phrase—“ripe for rediscovery”—used in the headline above the excellent appreciation of Comyns’s life and work by Lynn Barber in the Telegraph earlier this year? No, not really. As Barber herself perceptively points out, there’s a distinct pattern to Comyns’s career, one that began while she was alive and has continued since her death: “acclaim, followed by neglect, followed by revival.”

Charting Comyns’s trajectory over the course of the past eight years, I noted her star waxing and waning in line with the reappearance of various new editions. The 2013 Viragos were followed by two new NYRB Classics in the U.S.: Our Spoons Came from Woolworths, in 2015, and The Juniper Tree, in 2018. “Barbara Comyns’s writing is in the middle of a resurgence,” wrote Michael T. Fournier in his review of the latter for the Chicago Review of Books. Here we go again, I thought. She seemed to me like an author forever poised on the cusp of definitive rediscovery—whatever that even means—someone who never quite reached escape velocity. But now I think I had it all wrong. The current Comyns “revival”—as Horner, Barber, and the writer Christopher Shrimpton have all termed it—is just further evidence of the enduring appeal of her work. It doesn’t really matter that we’ve been here before. What matters is that Comyns is still being republished, critics are still writing about how brilliant her novels are, and—most importantly of all—these novels are still finding new readers.

*

For those of us who’ve been fans for a while, Comyns is a writer one never tires of revisiting. “I have read it many times,” the novelist Sarah Waters reports of The Vet’s Daughter, a brilliantly haunting tale of grisly horrors set in Edwardian Battersea that’s also surprisingly insightful about the psychological mechanisms of post-traumatic stress disorder, “and with every re-read I marvel again at its many qualities—its darkness, its strangeness, its humour, its sadness, its startling images and twists of phrase.” But all the more significantly, Comyns’s books continue to resonate with new generations of readers. “The particulars of Sophia’s delivery are outdated,” writes Emily Gould in her introduction to the NYRB Classics edition of Our Spoons Came from Woolworths, Comyns’s loosely autobiographical tale of marriage and motherhood while living on the breadline in bohemian London in the thirties, which contains some famously graphic descriptions of childbirth, “but the feelings she describes—of shame, helplessness, and terror, wonder at her baby countered by fear for his life—are still far too common in life, and far too rare in literature.” Most recently, Daunt Books declared Who Was Changed and Who Was Dead—a ghoulish, blood-soaked tale about an outbreak of ergot poisoning in a small village that drives many of its inhabitants mad, and was considered, on its initial publication, to be so disturbing it was actually banned in Ireland under the Censorship of Publications Act—a “twisted pandemic parable,” recognizing that the hysterical fear of contagion amplified therein with such horrifyingly excellent affect makes it especially evocative for readers today. “Perhaps she is currently enjoying a revival because her work speaks more clearly to readers now than it did in the mid-twentieth century,” suggests Horner in her TLS essay, citing Comyns’s originality in exploring “the horrors of grinding poverty and emotional cruelty while celebrating the beauty and the comic incongruities of life.” Comyns’s books are also timely because in many ways they’re ultimately oddly timeless. As Sadie Stein observes in her introduction to the NYRB Classics edition of The Juniper Tree, despite the occasional reference to contemporary life, ultimately the world of the novel is one “outside normal time … and governed by the arbitrary laws of fairy tales”—something that could be said of many of Comyns’s novels, and was echoed by Marina Warner. “In spite of the lovingly detailed suburban ambience, interiors, gardens and clothes,” she wrote of The Juniper Tree in her New York Times review of the book, “the atmosphere feels torqued beyond time and history into a fairy tale theater of desire and wan hope.”

But more than all this, the story of Comyns’s ongoing success also has things to tell us about the growing visibility of rediscovered classics and neglected books. That Observer review I wrote in 2013 afforded me a mere four hundred words to write about all three novels, and I had to pitch hard for those four hundred words. This isn’t to chastise my editor—I’m grateful they saw fit to give me any words at all! It’s long been notoriously difficult to find review space for reissues, regardless of the quality of the work in question. Yet this is something that, over the past few years, finally seems to be changing. Where once reissues were rarely found outside the remit of a notable classics imprint or the more esoteric lists of the smallest of independent publishers, these days they’re becoming increasingly popular. And many publishers are treating these reissues as they would standard front-list titles. At Daunt Books, Comyns’s novels sit alongside other reissues—Marian Engel’s Bear (1976), for example, and Raymond Kennedy’s Ride a Cockhorse (1991)—but also the latest from fresh talents such as Brandon Taylor and Amina Cain. Meanwhile, Faber has recently released new editions of Brigid Brophy’s The Snow Ball (1964) and Beryl Gilroy’s groundbreaking memoir Black Teacher (1976) with just as much fanfare as the publisher affords any of its living authors.

Just as more and more publishers have added Comyns to their lists, more and more people are recognizing the value of reanimating titles from the past. Reissues are taking up more space—on the shelves of bookstores, in review pages, and in readers’ lives. Had someone told me back in 2013 that six years later, I’d be writing a monthly column about out-of-print and forgotten books and I’d regularly see rediscovered books being afforded the same review space as their front-list counterparts, I’m not sure I would have believed it. I probably also wouldn’t have trusted anyone who told me those 2013 Virago editions weren’t Comyns’s last shot at fame. Obviously only time can tell, but I wouldn’t be surprised if I found myself writing about her all over again in another eight years. But then again, maybe I’ll leave it to someone else next time. Comyns has preoccupied my attention for the best part of a decade. I finally understand her story as one of success. And if I’ve learned anything over the past few years, it’s that there are plenty of other writers out there who deserve a revival or two of their own.

Lucy Scholes is a critic who lives in London. She writes for the NYR Daily, the Financial Times, The New York Times Book Review, and Literary Hub, among other publications. Read earlier installments of Re-Covered.

July 13, 2021

Redux: An Artist Who in Dreams Followed

Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

Hilton Als.

This week at The Paris Review, we’re commemorating another year of the best deal in town: our summer subscription offer with The New York Review of Books. For only $99, you’ll receive yearlong subscriptions and complete archive access to both magazines—a 34% savings!

To celebrate, we’re unlocking pieces from the archives of both The Paris Review and The New York Review of Books. Read on for Hilton Als’s Art of the Essay interview, paired with his essay “Michael”; Fernanda Melchor’s “They Called Her the Witch,” paired with Emmanuel Ordóñez Angulo’s review of the novel from which it is excerpted, Hurricane Season; and Adrienne Rich’s poem “Architect,” alongside Mark Ford’s essay on two recent collections of Rich’s poetry and essays.

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, poems, and works of criticism, why not subscribe to both The Paris Review and The New York Review of Books and read both magazines’ entire archives?

Hilton Als, The Art of the Essay No. 3

The Paris Review, issue no. 225 (Summer 2018)

For me, writing is a way of struggling through the intricacies of an antiempirical sensibility. And there must be words other than fiction and nonfiction. I see fiction not as the construction of an alternate world but as what your imagination gives you from the real world.

Michael

By Hilton Als

The New York Review of Books, August 13, 2009, issue

James Baldwin did not live long enough to see Jackson self-destruct. And the most interesting aspect of his essay in light of Jackson’s death is Baldwin’s identification with Michael Jackson, another black boy who saw fame as power, and both did and did not get out of the ghetto he had been born into, or away from the father who became his greatest subject. But the differences are telling.

They Called Her the Witch

By Fernanda Melchor, translated by Sophie Hughes

The Paris Review, issue no. 231 (Winter 2019)

They called her the Witch, the same as her mother; the Girl Witch when she first started trading in curses and cures, and then, when she wound up alone, the year of the landslide, simply the Witch. If she’d had another name, scrawled on some timeworn, worm-eaten piece of paper maybe, buried at the back of one of those wardrobes that the older crone crammed full of plastic bags and filthy rags, locks of hair, bones, rotten leftovers, if at some point she’d been given a first name and last name like everyone else in town, well, no one had ever known it, not even the women who visited the house each Friday had ever heard her called anything else.

Deadly Myths

By Emmanuel Ordóñez Angulo

The New York Review of Books, January 14, 2021, issue

The novel’s themes—poverty (and all that comes with it: dire working conditions, educational deprivation), repressed sexuality, political corruption, and the opium of religion—all point to its main subject, which is violence. But to list these as elements of a Mexican story is to assert a platitude, and Melchor’s novel is not a catalog of the country’s troubles. Hurricane Season is, first and foremost, a horror story—its horror coming from rather than contrasting with the lyricism of Melchor’s prose.

Architect

By Adrienne Rich

The Paris Review, issue no. 155 (Summer 2000)

You could say he spread himself too thin a plasterer’s

term

you could say he was then

skating thin ice his stake in white colonnades against the

thinness of

ice itself a slickened ground

Could say he did not then love

his art enough to love anything more

Could say he wanted the commission so

badly betrayed those who hired him an artist

who in dreams followed

the crowds who followed him

‘Inventing New Ways to Be’

By Mark Ford

The New York Review of Books, November 8, 2018, issue

In the light of Rich’s subsequent career, the terms that Auden used to praise her early work in his introduction to A Change of World came to seem almost comically misguided: her poems, he suggests, are “neatly and modestly dressed, speak quietly but do not mumble, respect their elders but are not cowed by them, and do not tell fibs.” Yet Auden’s somewhat patronizing précis of the virtues of Rich’s debut volume captures some of the cultural assumptions that initially shaped her, as both a poet and a person, and against which she would in time so spectacularly rebel.

If you enjoyed the above, don’t forget to subscribe! In addition to four print issues per year, you’ll also receive complete digital access to our sixty-eight years’ worth of archives. Or, choose our new summer bundle and purchase a year’s worth of The Paris Review and The New York Review of Books for $99 ($50 off the regular price!).

This Book Is a Question

Claire Lispector by Maureen Bisilliat, August 1969, IMS Collection. CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

In an interview with Jùlio Lerner for TV Cultura, Clarice Lispector described her final writing project, the novella The Hour of the Star, as “the story of a girl who was so poor that all she ate was hot dogs.” “That’s not the story, though,” she continued. “The story is about a crushed innocence, an ‘anonymous misery.’ ” This idea of a “crushed innocence, an anonymous misery” is the axis upon which all of Lispector’s work revolves. Lispector, a Jewish Ukrainian, was forced to flee with her family. They migrated to Brazil, where they lived in Recife, in the northeast. In Recife, Lispector’s mother died when she was nine and her father struggled to find a means to support the family. In the same TV interview, Lispector is asked, “Clarice, what did your father do professionally?” This is a common question used to determine one’s social class. Lispector’s face in the frame during the interview appears sad: her eyes, turned away, her mouth half-open. The question is a form of wounding: you can answer and remain fixed in your social class or you can lie or, of course, you can answer obliquely. Lispector tells the truth. She responds, “A sales representative, things like that.” Indeed, Lispector was intimate with precarity. In her preface to The Hour of the Star she wrote, “I dedicate it [this book] to the memory of my former poverty, when everything was more sober and dignified and I had never eaten lobster.”

“My truest life is unrecognizable,” Lispector writes in The Hour of the Star, “extremely interior and there is not a single word that defines it.” This sentiment, of being inexplicable to others, speaks directly to Lispector’s own experience. Though she was the child of immigrants raised in poverty, when Lispector became a recognized writer, she appeared to the Brazilian middle class as a member of their class. And yet, at the same time, she appeared mysterious, an enigma. This seeming strangeness is due to the middle class’s blindness to the working class. They are unable to comprehend Lispector because they are unable to see beyond the confines of their own social class. Like Barbara Loden, who appears incomprehensible to middle-class women, Lispector, excised from her social class, with her melancholia, her alienation from middle-class society, and her removal from the literary world, appears incomprehensible, too.

By marrying her law school classmate, Maury Gurgel Valente—who, upon graduation, became a diplomat—Lispector moved from the working class to the middle class. Lispector never abandoned her origins, though, continuing to write about the poor and marginalized up until The Hour of the Star, written as she was dying. Her childhood always remained intact and within her. In “O manifesto da cidead,” she writes: “That is the river. That is the clock. It is Recife … I see it more clearly now: that is the house, my house, the bridge, the river, the prison, the square blocks of buildings, the stairway, where I no longer stand.” Like Macabéa—the female protagonist of The Hour of the Star, who, Lispector writes, “always noticed small and insignificant things”—Lispector remained acutely aware of the world, seeing everything. As she writes in “Literature and Justice,” “Ever since I have come to know myself, the social problem has been more important to me than any other issue: in Recife the black shanty towns were the first truth I encountered.” This contradiction, that of living as a member of the middle class while identifying with her precarious childhood, resulted in alienation, in melancholia. When she moved to Rio, she left the place that had formed her. This loss resulted in a wound, in a void that could not be filled in with anything. As an adult, Lispector suffered from melancholia, a condition that worsened as the years passed. In Switzerland, where she was stationed with her husband, she saw a psychoanalyst who prescribed pills to alleviate her depression. But because her depression was a symptom of her melancholia, the external manifestation of it, the pills were unable to alleviate it. Surrounded by people who could not see her, people who she felt separate from, Lispector retreated further into her interior world.

“Yes,” she writes in The Hour of the Star, “I have no social class, marginalized as I am. Yes, the upper class considers me a weird monster, the middle class worries I might unsettle them, the lower class never comes to me.” The terms monster and monstrous appear repeatedly throughout Lispector’s work. She felt herself a monster or, rather, she felt herself seen by others as a monster. For example, in The Hour of the Star, she asks, “Who hasn’t ever wondered: am I a monster or is this what it means to be a person?” According to the Oxford English Dictionary, a monster is “a mythical creature which is part animal and part human, or combines elements of two or more animal forms, and is frequently of great size and ferocious appearance. Later, more generally: any imaginary creature that is large, ugly, and frightening.” A monster, then, might be a working-class Jewish woman from northern Brazil who passes as a middle-class member of the Brazilian bourgeoisie: one part intellectual, one part peasant, one part worker, and one part diplomat’s wife.

As an “anonymous” Northeasterner, Lispector was “monstrous” in the eyes of the middle class. Then, later, when she was seen as a member of the middle class, she was seen as a “sacred monster.” In Esçobo, she writes: “One of the things that makes me unhappy is this story of the sacred monster: others fear me for no reason, and I end up fearing myself.” Here, Lispector articulates how we are trained, through the constant interpolation of shame connected to our social class, to despise ourselves.

Abandoning our class background is always an option. We see this possibility in The Hour of the Star, specifically, in Lispector’s creation of Olímpico, Macabéa’s boyfriend, and Glória, her best friend. When Macabéa meets Olímpico, she immediately recognizes herself in him. But he has internalized the society’s beliefs and values, their sense of entitlement, cruelty, and their hatred of the working class and the poor. “Olímpico de Jesus,” Lispector writes, “worked in a metals factory and she [Macabéa] didn’t even notice he didn’t call himself a ‘worker’ but a ‘metallurgist.’ ” He has internalized self-consciousness, something Macabéa does not have. Unlike her, he is aware of the systems of hierarchy, his place in them, and the skills necessary to propel himself out from his class. “He [Olímpico] was more susceptible to survive than Macabéa because it wasn’t by chance that he had killed a man, a rival of his, in the back of beyond, the long jackknife entering softly softly the backwoodsman’s liver. He had kept this crime an absolute secret, which gave him the power a secret gives.” Macabéa falls in love with Olímpico because she sees herself in him: he is also precarious, a laborer. But Olímpico sees his own lower class standing in her and, as a result, despises her for it. Indeed, as Lispector writes, “Having killed and stealing made him more than a random occurrence, they gave him some class, they made him a man whose honor had been defended.” Olímpico leaves Macabéa for her best friend, Glória, because doing so helps him move out of his class: “But when he [Olímpico] saw Glória, Macabéa’s co-worker, he immediately realized she had class.” As Lispector continues:

The fact that she was a carioca made her belong to the longed-for clan from the South. Seeing her, he immediately guessed that, though ugly, Gloria was well fed. And that made her quality goods.

His cruelty represents the violence that is inherent in a class-based society. To absorb the capitalist culture’s beliefs and values is to become complicit in it. In the case of Olímpico, this means seeing one’s self and others as mere objects, and seeing relationships solely for their transactional aspect. This is precisely what Olímpico does. In fact, though Macabéa is surrounded by people of her own class (Olímpico, Glória, and the psychic), each of them has absorbed the beliefs of society: that people are to be utilized as means to move one’s self forward. This self-erasure and the erasure of other working-class people to make money and acquire more capital is the result of capitalism. Because Macabéa has nothing they can extract, Olímpico and Glória ignore her. They are like the doctor Macabéa visits: “This doctor had no point whatsoever. Medicine was just to make money and never for love of his profession or of the sick.” He saw his patients as rejects of society, like himself. “He knew,” Lispector writes, “he was out-of-date with medicine and clinical novelties but it was good enough for poor people. His dream was to have money to do exactly what he wanted: nothing.”

Macabéa, on the other hand, does not engage in transactional relationships, does not objectify herself or others. Indeed, she is unaware (until she meets the psychic) of her own class standing. It is precisely this aspect of her that makes her appear idiotic to others, as Rodrigo, the male narrator, explains: “She had never figured out how to figure things out.” She didn’t know how the structures of power worked or how she might manipulate or use other people to gain access to this power. This “not knowing” is considered by others to be evidence of her “idiocy.”

Similarly, Macabéa is curious. She asks questions. This is not the case with her boyfriend or her coworker, or others of her class who, instead of looking at the world and asking questions about it, expend all their energy trying to propel themselves up the class ladder. Indeed, what Macabéa is criticized for is not her philosophical inquiries, her curiosity regarding why things are the way they are but, rather, her ignorance regarding how to use others. In fact, the entire book is described by Lispector as a question: “I swear this book is made without words. It is a mute photograph. This book is a silence. This book is a question.”

Cynthia Cruz is the author of six collections of poems and a volume of critical essays. She has published poems in numerous literary journals and magazines including The New Yorker, Kenyon Review, The Paris Review, BOMB, and The Boston Review.

Excerpted from The Melancholia of Class, by Cynthia Cruz (Repeater Books, 2021). Reprinted with permission from Repeater Books.

Read Cynthia Cruz’s poems “Fragment” and “Phosphorescence,” which appeared in the Summer 2019 issue.

July 12, 2021

Reading Jane Eyre as a Sacred Text

Frederick Walker, A.R.A., Rochester and Jane Eyre, 1899. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The summer that I did my chaplaincy internship was a wildly full twelve weeks. I was thirty-two years old and living in the haze of the end of an engagement as I walked the hospital corridors carrying around my Bible and visiting patients. “Hi, I’m Vanessa. I’m from the spiritual care department. How are you today?”

It was a surreal summer full of new experiences hitting like a tsunami: you saw them coming but that didn’t mean you could outrun them. But the thing that never felt weird was that the Bible I carried around with me as I went to visit patient after patient, that I turned to in the guest room at David and Suzanne’s or on my parents’ couch to sustain me, was a nineteenth-century gothic Romance novel. The Bible I carried around that busy summer was Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre.

I love the idea of sacredness. I want to be called to bigger things, outside of myself. I don’t want my life to be a matter of distractions from death and then death. I want to surprise myself and to honor the ways in which the world surprises me. I want to connect deeply to others, to the earth, and to myself. I want to help heal that which is broken in us. Which is why I went to divinity school at thirty years old.

But God, God-language, the Bible, the church—none of it is for me. And halfway through divinity school, I realized that my resistance to traditional religion was never going to change. I wanted to learn how to pray, how to reflect and be vulnerable. And I didn’t think that the fact that I didn’t believe in God or the Bible should hold me back.

I, like many of us, have such complicated feelings about the Bible that it’s distracting to even try to pray with it. Too many caveats feel necessary to even begin to try. So I asked my favorite professor, Stephanie Paulsell, if she would spend a semester teaching me how to pray with Jane Eyre. Throughout the semester, we homed in on what I was searching for, a way to treat things as sacred, things that were not usually considered to be divinely inspired. The plan was that each week I would pull out passages from the novel and reflect on them as prayers, preparing papers that explored the prayers in depth. Then, together, we would pray using the passages.

This proved more challenging than I’d expected. I so resisted praying. In Judaism, prayers are prewritten and always in Hebrew. It felt like too much of a betrayal to my Judaism and to my family to pray in English. I just couldn’t do it. Stephanie would invite me, gently, to pray every once in a while. But I always resisted, so instead she would hand me books. She gave me Guigo II, a Carthusian monk who developed a four-step reading practice to bring his fellow monks closer to God. She gave me James Wood, a fellow atheist who wrote How Fiction Works. She gave me Simone Weil, a Jewish woman who escaped to America from Vichy, France, only to go back to Europe and die of starvation because she would not eat more than the prisoners of Auschwitz ate, unable to handle her privilege of escaping.

Eventually, we decided that sacredness is an act, not a thing. If I can decide that Jane Eyre is sacred, that means it is the actions I take that will make it so. The decision to treat Jane as sacred is an important first step, surely, but that is all the decision was—one step. The ritual, the engagement with the thing, is what makes the thing sacred. Objects are sacred only because they are loved. The text did not determine the sacredness; the actions and actors did, the questions you asked of the text and the way you returned to it.

This premise is obviously quite different from traditional ideas of engaging with sacred texts. What makes the Bible sacred is a complex ecosystem of church legitimacy, power, canonization, time, ritual, and other contributing factors. When the sacredness of the Bible or the Koran is questioned, great bodies of people and institutions will rush to defend them. Regardless of how these sacred texts are treated by an individual, they are widely considered to be sacred texts. In how I was treating Jane Eyre, I was saying the opposite: if one treats Jane Eyre as a doorstop, it is a doorstop. If one treats it as sacred, then it can be sacred.

Over the months we worked together, Stephanie and I discerned that you need three things to treat a text as sacred: faith, rigor, and community.

Faith is what Simone Weil called “the indispensable condition.” And what I came to mean by faith was that you had to believe that the more time you spent with the text, the more gifts it would give you. Even on days when it felt as if you were taking huge steps backward with the text, because you realized it was racist and patriarchal in ways you hadn’t noticed when you were fifteen or twenty or twenty-five, you were still spending sacred time with the book. I solemnly promised that when I did not know what a passage was doing, or what Brontë was doing with her word choice, rather than write it off as antiquated, anachronistic, or imperfect, I would have faith that the fault was in my reading, not in the text. In Friday night services, rabbis do not talk about what year the book of Genesis was most likely written and how the version we have today was canonized. A good rabbi instead considers the metaphor of God separating light from dark instead. That was how I set about considering Jane Eyre.

Faith does not mean that I think the text is perfect. Perfect and sacred are not the same thing. My parents, who are sacred to me, are not perfect. Things that are not perfect can give you blessings not only in spite of their imperfections, but because of them. When I was fifteen, I saw Rochester keeping Bertha at home and out of an asylum as an act of mercy. At thirty, his locking her up in an attic and all but forgetting her was not nearly enough to impress me and became something I had to forgive, rather than a virtue of his. Both times, Rochester’s and the novel’s presentation of that act were generative to me. The text was in conversation with my evolving sense of what mercy really is. The text’s imperfections accompany me in my own imperfections and will continue to act as reflection points for me whenever I return to it.

Rigor means that you keep at it even when your heart isn’t in it. You have to do the work whether or not you are in the mood. You have to be slow and deliberate even if you aren’t called to be so that day. It was a commitment, not a hobby. The best secular example of rigor I can think of is the way my brothers look at a baseball scoreboard. We see the same numbers. But they keep looking and looking at them until it becomes clear to them what pitch the pitcher is going to throw next, and they are usually right.

Another example of this kind of rigor is the way you might read into a text message from someone you have gone on a date with. You read it and reread it until you think the “truest” meaning of the message has revealed itself to you. You show it to friends to get their opinions. I was going to do that with Jane Eyre. The person receiving a text has faith that there is a real meaning behind that text and if they can figure it out then they will be able to better manage their own emotions and expectations. And I have faith that Jane Eyre always has some sort of important news to give me.

Community, the final component for treating a text as sacred, is the simplest of the ideas. It means that you need a gym buddy, someone to force you to work out even when it feels like the one thing you don’t want to do. You need someone to question your opinion when you are most sure you are right.

And even more than that, a kind of magic happens when you work in community. Other people’s points of view will blow your mind and open you up to things that you never would have seen in the text on your own. Speaking out loud to someone you respect will help you find your own voice. Engaging with others in sacred, committed, rigorous spaces allows you to treat them as sacred, which is the point of all this anyway.

Vanessa Zoltan has a B.A. in English literature and creative writing from Washington University in Saint Louis, an M.S. in nonprofit management from the University of Pennsylvania, and a M.Div. from Harvard Divinity School. She is the CEO and founder of Not Sorry Productions, which produces the podcasts Harry Potter and the Sacred Text, Twilight in Quarantine, and Hot & Bothered. She also runs pilgrimages and walking tours that explore sacred reading and writing.

Adapted from Praying with Jane Eyre: Reflections on Reading as a Sacred Practice , by Vanessa Zoltan, published by Avery, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2021 by Vanessa Zoltan.

July 9, 2021

Staff Picks: Traps, Tall Tales, and Table Saws

César Aira. Photo: Nina Subin. Courtesy of New Directions.

César Aira’s latest book to appear in English, The Divorce (translated from the Spanish by Chris Andrews), brings to mind an older approach to fiction—that of pure fabular storytelling, unencumbered by character development or realism. The plot is essentially nonexistent: a freshly divorced academic travels from Providence, Rhode Island, to Buenos Aires in order to distract himself from his emotions, and spends a day sitting outside a café around the corner from his guesthouse. While sitting there and chatting with a video artist named Leticia, he encounters Enrique, the guesthouse owner, who is holding a bicycle and appears to be freshly soaked from a large amount of water that has just been splashed upon him. Multiple stories quickly emerge: a surreal childhood encounter between Enrique and Leticia, the impoverished background of an acquaintance of Enrique’s named Jusepe, the strange life of Enrique’s mother (including the time she narrowly survived a mob killing), and the mysterious origins of the love of Enrique’s life, who is connected to the water with which the narrator finds Enrique soaked. These are tall tales in the most pleasurable sense of the term, looping and linking around one another as though to echo the strange circularities and synchronicities that so often repeat themselves in the course of a human life. “And with one hand,” writes Aira of Enrique, “he went on holding the delicate machine at his side: that ‘little steel fairy,’ the bicycle, from whose spinning stories are born.” —Rhian Sasseen

There’s a scene in L. M. Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables where Anne and her best friend, Diana, have a proper tea party. They wear fancy dresses and inquire after each other’s family, there are lots of pleases and may-I’s, and then they get absolutely wasted off of raspberry cordial. I’ve always cherished descriptions of food in literature, and as a child I wanted to taste that delicious, illicit cordial more than anything. A few weeks ago, I picked up a bottle of Current Cassis, a black currant liqueur made in the Hudson Valley. I was drawn to the Matisse-esque logo, and I’ve long loved the taste of currants. I poured it over some ice, and immediately I was in Avonlea—it was the cordial. Syrupy and tangy, Current Cassis tastes like a special occasion. I’ve enjoyed it in a Kir Royale and used it to replace vermouth in Negronis. There was only one small problem: the girls in Anne of Green Gables drank raspberry cordial. I pulled out my old copy of the book and returned to the scene that had burrowed itself into my taste buds: “Anne, you certainly have a genius for getting into trouble. You went and gave Diana currant wine instead of raspberry cordial.” It was currants the whole time. —Eleonore Condo

Anna Webber. Photo: TJ Huff.

Anna Webber has been a jazz artist to watch for more than a decade. She uses complicated, often inscrutable schemes to produce aggressive, emotional, and intellectually stimulating music in which improvisation and composition duel in all sorts of surprising ways. She’s achieved a new level of artistic maturity on her past few records (2020’s Both Are True, recorded with the big band she coleads with Angela Morris, is particularly stunning), and Idiom, a new double-disc set, offers a deep dive into her musical world. The first disc features Webber’s long-standing trio with the pianist Matt Mitchell and the drummer John Hollenbeck. When he’s not closely tracking Webber’s intricate melodies and rhythms, Mitchell plays like a table saw (I mean this in the best way), shooting sparks in every direction. And nowhere else can you hear the brilliant and otherwise gentle Hollenbeck prodding and pounding—though he is no less precise here than in his own, more mainstream music or in his work with Meredith Monk. The second disc records a new thirteen-piece ensemble, though don’t expect much swing—this music is hyper, uneasy, and amorphous, punctuated by patches of silence and sudden bursts of noise. The musicians are searching their instruments for not just notes but sounds, and I often feel like I’m exploring some dark place while holding a flashlight with dying batteries—it’s exciting and a bit scary. —Craig Morgan Teicher

The internet is a fount of testaments to the enormity and sheer multifariousness of human achievement. This week, for instance, a fourteen-year-old named Zaila Avant-garde became the first Black American to win the Scripps National Spelling Bee, but she initially garnered attention for her Guinness World Record–setting basketball skills. In a video posted this past April, she dribbles balls of various sizes and colors like some combination of a celestial deity and a living planetary mobile. Summer Games Done Quick is an extended display of similarly astonishing feats, albeit of the digital variety. The yearly charity event, the 2021 installment of which will wind to a close this weekend, showcases the absolute pinnacle of speedrunning, the practice of completing a video game as quickly as possible. Just about any game can be subject to speedrunning; a cursory glance at this year’s schedule reveals such wildly divergent titles as Grand Theft Auto III, SpongeBob’s Truth or Square, Factorio, Need For Speed: Porsche Unleashed, and Demon’s Souls. I suggest tuning in for even five minutes just to witness a little controller wizardry. If you’re unsure of where to jump in, Bubzia’s blindfolded run of Super Mario 64 tomorrow promises to be jaw-dropping. —Brian Ransom

Barry Windsor-Smith’s Monsters is no gentle giant. This staggeringly detailed 365-page graphic novel revolves around the orphan-turned-outcast Bobby Bailey, who unwittingly signs up for an experimental U.S. military program bent on building a super soldier from Nazi technology salvaged during the final days of World War II. If this description reads like a recipe for some musty bargain-basement hero pulp, then Windsor-Smith has set an exceedingly well-concealed trap. Ornamented with the sensational décor of comics, this book succeeds in reaching beyond those familiar baubles of genre and form to string uncommonly delicate stories of loss, familial bonds, abuse, and romantic love over a not-so-distant history of hatred and violence that haunts us still. Thirty-five years in the making, this is a narrative of patience—foremost in the Latin sense—that asks its readers to take their time, to sit with the brutality of its scenes and sink through the inky depths, to feel for and with its characters, burdensome though these feelings may become, because emotions of this heft should be difficult to bear and their steady transfer from the page requires stamina of the heart. Achingly good, epically scaled, and impeccably designed, Monsters will leave you changed. —Christopher Notarnicola

From Barry Windsor-Smith’s Monsters. Image courtesy of Fantagraphics Books.

Game, Set, Match: Tennis in the Archive

Gentlemen’s Doubles tennis final at the 1897 Wimbledon Championships. Photo: J. Parmley Paret. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

I learned a lot while fact-checking the Summer 2021 issue, and I owe a ton of that knowledge to Joy Katz for her essay “Tennis Is the Opposite of Death: A Proof.” Now, whenever the subject of tennis comes up, I find myself bursting with trivia. Did you know that the first Wimbledon championship was held in 1877, or that the All England Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club employs a Harris’s hawk named Rufus to keep pigeons from interfering with matches, or that Hawk-Eye is the name of the technology used to verify a challenged umpire call? There’s a story in there somewhere. Tennis is well known for drawing the attention of the literary set—Martin Amis, Claudia Rankine, David Foster Wallace, and John Jeremiah Sullivan come to mind—and the archive of The Paris Review boasts a wealth of writing on the subject, the sport often taking the role of the Hawk-Eye—a keen lens through which life’s quick volleys may be slowed, reviewed, and challenged in turn.

In Ross Kenneth Urken’s “1, Love,” a tennis stroke becomes the embodiment of a young boy’s “neurotic, racquet-throwing heart,” with nods to Vladimir Nabokov and Philip Roth along the way:

At its best, my slice backhand follows the flamboyant path of a violin virtuoso’s bow striking the climactic note of a concerto—from above my right shoulder plucked diagonally down to my left shoestring. The ball’s tone is a hollow pok on hard courts and a chalky chh-chh on clay that dies on the second bounce. All these dramatics—mere vestiges of a time when I wanted to impress Angela, my middle school crush.

Louisa Thomas opens “Let It Be Love” by rejecting the schmaltzy application of a popular tennis term:

There’s a T-shirt favored by a certain kind of tennis player that says, “Love means nothing to a tennis player.” It’s a pun that no one, it seems, can resist. The 2010 U.S. Open’s slogan is “It must be love.” Please.

Nick Twemlow eschews sentimental love to tackle a range of tough and tender matters of the heart in his sprawling poem “Attributed to the Harrow Painter”:

When I was twelve,

My tennis coach asked me

To pose for him after practice.

I’m an artist, he told me,

I coach to pay the bills …

“Double Fault” finds A-J Aronstein investigating tennis to “figure out what to pass on (a service motion, a slice backhand, a tennis club, a philosophy)”:

The courts were our family’s livelihood; their quality was a matter of pride for my father. Like a farmer who knows the precise chemical composition of the soil in his fields, he could step out on the courts, sniff the air, and know whether to water them or let them bake in the sun.

Pamela Petro’s “ThunderStick” is titled after and structured around a tennis racket:

It’s not every day you get a box of tennis racquets in the mail. I ripped it open and immediately shook hands with each one.

And Clancy Martin similarly centers his story “An Event in the Stairwell”:

I kept my eyes on the racket. Also on his eyes, because you can anticipate a blow that way. Everyone narrows his eyes and looks where he’s going to hit you before he strikes. This is the first lesson of boxing.

“She promised she’d buy this racket from me. I got this racket special. From my daughter.”

Randy, Emily had told me, had a high school–age daughter who was expected by many people to be the next Serena Williams. She lived with her mother in the Bronx and was sponsored by Puma. I noticed the tennis racket had a broken string. Emily was hiding in the bedroom all this time and had instructed me to tell Randy that she was out. I could not decide whether that was reassuring or suspicious.

In “The Ghost in the Dirt,” Rowan Ricardo Phillips talks clay courts and the forgotten legacy of Georges Henri Gougoltz:

Myth, legend, and truth: they work on their own time and make their own order—they’re brilliant and terrible. This story has never been and will always be about a man’s suicide in the face of crushing financial debt. We’ll get to that. And this story both never was and will always be about Rafael Nadal’s run as the master of clay-court tennis. The two collided, unwittingly, on a warm Sunday afternoon in early June in Paris, 2017, when Nadal once again won the French Open in front of a crowd packed into Court Philippe Chatrier.

To take us out, Scott Korb illustrates the mythic heights of tennis writing in his essay “Stage Struck”:

Sports broadcasters are guiltier these days than sportswriters of the “grand metaphor” approach where tennis is concerned. Following the major tournaments this summer on television, I’ve heard again and again of the history about to be made: Rafael Nadal’s seventh French championship (history made), Djokovic’s career Slam (history not made), Murray’s becoming the first Brit to win Wimbledon since 1936 (nope). Even Federer’s thirty-first birthday was seen as historic, according to a certain fan site: “God is too an imaginative word, rather I would call him a ‘Prophet’ / Someday the prophet will make Tennis the most loved sport, I bet.”

Christopher Notarnicola is a veteran of the U.S. Marine Corps and holds an M.F.A. from Florida Atlantic University. His work was featured in The Best American Essays 2017 and has been published in American Short Fiction, Bellevue Literary Review, Consequence Magazine, Image, North American Review, The Southampton Review, and elsewhere. Find him in Pompano Beach, Florida, and at christophernotarnicola.com.

If you enjoyed the above, don’t forget to subscribe to The Paris Review. In addition to four print issues per year, you’ll also receive complete digital access to our sixty-eight years’ worth of archives. Or, choose our new summer bundle and purchase a year’s worth of The Paris Review and The New York Review of Books for $99 ($50 off the regular price!).

Eileen in Wonderland

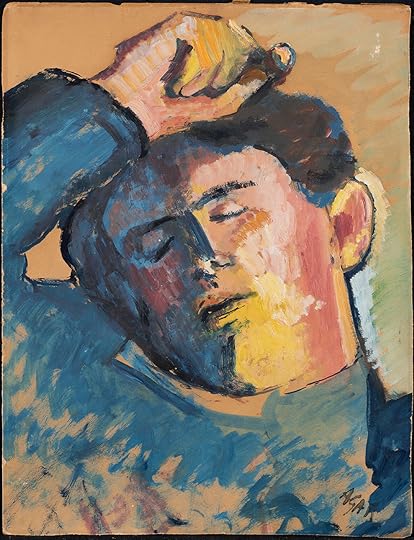

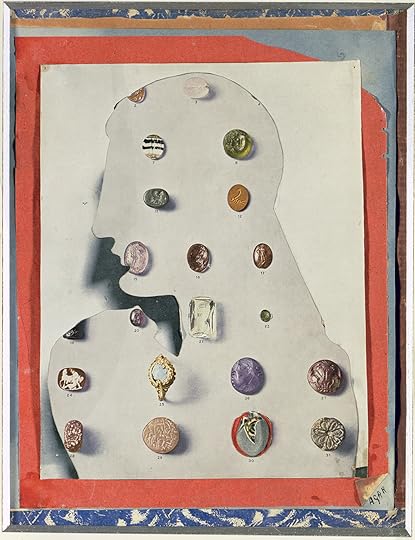

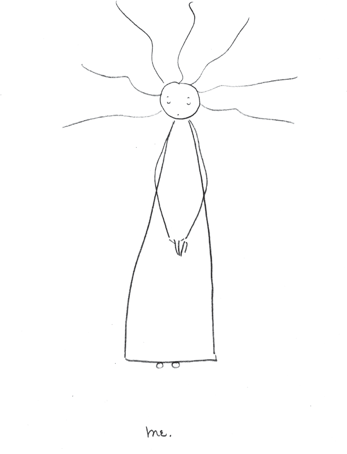

In an undated note bequeathed to the Tate Archive in 1992, Eileen Agar (1899–1991) writes of her admiration for the author of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland: “Lewis Carroll is a mysterious master of time and imagination, the Herald of Sur-Realism and freedom, a prophet of the Future and an uprooter of the Past, with a literary and visual sense of the Present.” The same could be said of Agar, whose long career as an artist spanned most of the twentieth century and intersected with some of the prevailing movements of the time, including Cubism and surrealism. Her timeless work—including the oil painting Alice with Lewis Carroll—will be on view through August 29 at the Whitechapel Gallery’s “Eileen Agar: Angel of Anarchy,” the largest exhibition yet of the sui generis artist’s oeuvre. A selection of images from the show appears below.

Eileen Agar, Erotic Landscape, 1942, collage on paper, 10 x 12″. Private collection. Estate of Eileen Agar/Bridgeman Images. Photograph courtesy Pallant House Gallery, Chichester © Doug Atfield.

Eileen Agar, Dance of Peace, 1945, collage and gouache on paper. Private collection. Estate of Eileen Agar/Bridgeman Images.

Eileen Agar, Quadriga, 1935, oil on canvas, 20 x 24″. Courtesy of The Penrose Collection. Estate of Eileen Agar/Bridgeman Images.

Eileen Agar, Collective Unconscious, 1977, acrylic on canvas, 41 3/8 x 40 1/8″. Courtesy of Royal Academy of Arts. Estate of Eileen Agar/Bridgeman Images.

Eileen Agar, Joseph Sleeping, 1929, oil on board. Courtesy of Redfern Gallery, London. Estate of Eileen Agar/Bridgeman Images.

Eileen Agar, Precious Stones, 1936, collage on paper, 10 1/4 x 8 1/4″. Courtesy of Leeds Museums and Galleries. Estate of Eileen Agar/Bridgeman Images.

Eileen Agar, Eileen Agar, 1927, oil on canvas, 30 1/8 x 25 1/4″. NPG 5881. Estate of Eileen Agar/Bridgeman Images.

Eileen Agar, Alice with Lewis Carroll, 1961, oil on canvas. Private collection. Estate of Eileen Agar/Bridgeman Images. Image courtesy private collection.

Eileen Agar, Untitled collage, 1936, mixed media and collage on paper, 29 3/4 x 21″. Courtesy of Mayor Gallery. Estate of Eileen Agar/Bridgeman Images.

Eileen Agar, Self-Portrait with Dandy, West Bay, Dorset, 1934, drawing with collaged leaf. Private collection. Estate of Eileen Agar/Bridgeman Images.

Eileen Agar, Rock 3, 1985, acrylic on canvas, 23 5/8 x 23 5/8″. Courtesy of Redfern Gallery, London. Estate of Eileen Agar/Bridgeman Images.

Photograph of Agar wearing Ceremonial Hat for Eating Bouillabaisse, 1936. Photograph. Private collection. Estate of Eileen Agar/Bridgeman Images.

“Eileen Agar: Angel of Anarchy” will be on view at the Whitechapel Gallery, in London, through August 29.

July 8, 2021

In the Gaps: An Interview with Keith Ridgway

Keith Ridgway. Photo courtesy of New Directions.

The central chapter of Keith Ridgway’s latest novel, A Shock , takes place in The Arms—a South London pub that serves as a gathering place for many of the book’s characters. “The Story,” as the chapter is titled, is about local patrons regaling one another with anecdotes, all of which speak either directly or obliquely to the stories in the surrounding chapters or to the novel at large. In one tale, a bird flies as high as a mountaintop, where its heart gives out, and it drops, only to take another flight to those same mountainous heights—“Stuck in a loop. Doing the same thing again and again.” So, too, does this novel deal in loops, reinventing itself with every chapter while following familiar characters and themes, collapsing at its center only to unfurl again, opening with “The Party” and closing with “The Song,” which takes place at the titular celebration of the first chapter.

A Shock is an artful exercise in nervous revelry. There is an exciting, almost voyeuristic quality to the reading experience, a bit like wandering slowly through the very house party Ridgway depicts. The novel features an exquisitely arranged guest list of characters. A woman spies on her neighbors through a hole in the wall. Another habitually invents elaborate personal histories. A man obsesses over what might have happened to the former tenants of his apartment. And Ridgway makes a wonderful master of ceremonies, introducing each character in turn and nodding to the many connections between. His language is realistic yet defamiliarized, balancing a fealty to the many flaws inherent in natural modes of expression and the writerly necessities of successful storytelling, rendering confusion with narrative clarity and imprecision with the utmost intention, so that dialogue may drift in and out of earshot, perspectives may shift, details may gain or lose focus as faces emerge or fade from the crowd, but always in service of honest conversation and never at the expense of a good time.

Ridgway is from Dublin. In addition to A Shock, he is the author of the novels Hawthorn & Child, Animals, The Parts, and The Long Falling, which was adapted as the 2011 film Où va la nuit. His writing has earned him the Prix Femina Étranger, the Rooney Prize for Irish Literature, and the O. Henry Award. He lives in London. As much as I would have loved to attend an actual party at the Ridgway place, this interview was conducted over the phone, over the static of the Atlantic, over one evening this past April.

INTERVIEWER

I’d like to start with the idea of the middle. Your latest novel, A Shock, finds characters trapped in an attic, introduced in medias res, and literally squeezed through a gap between walls. What brings you to write toward these liminal spaces?

RIDGWAY

Well, that’s where we live. In the gaps. In this book there are characters who are trapped or stuck or separated in various ways. Sometimes, as you say, literally. Stuck in a building or in part of a building. But also, there are characters trapped in looped thinking, or in poor housing, terrible work, and the political gap that allows those things. I’m not sure I’m all that interested in the spaces themselves, but I am interested in the people. And among them are others who seem less trapped. Who seem somehow to have more freedom of imaginative movement, based on something in themselves, a sort of ability to walk through things. I was interested in all these people.

INTERVIEWER

Both A Shock and Hawthorn & Child follow characters whose conflicts are rooted in their own misconceptions or lack of knowledge. How do you approach the task of writing characters like that?

RIDGWAY

I’ve always been interested in confusion. And I think fictional characters often seem far too well-equipped for the world in comparison to people I know, or to myself. I’m much more interested in writing about characters who don’t really know what it is they want, who don’t even know how they got to the place they’ve found themselves. They don’t know how to proceed, how to go forward, how to go back. That’s much closer to our experiences, right? Mine anyway. And it’s funny. Confusion is funny. So I work on trying to get to know my characters. I spend a lot of time thinking about them, trying to get a sense of them. Some come very quick. Like Pigeon, in A Shock. He just wandered in, and there he was. But with most of them, it takes a bit of time. I try to move slowly. I write a lot that never finds its way into the finished book. I try not to make any decisions about these people, and I just try to allow them to grow in my imagination. Eventually they begin to take on aspects that I find convincing. Then I’m better able to write them.

INTERVIEWER

Do you ever begin with aspects of your own experience? By that I mean, will you use a personal question to establish character or conflict or a driving question for your narratives?

RIDGWAY

I’m not interested in conflicts. I’m not interested in questions or in driving things. I don’t tend to think in those terms. I do often begin with, as you say, aspects of my own experience. I mean, obviously the writing has to start somewhere, right? So I use what I know, and I push it and fill it out. I tend not to think of what I do as explorations or inquiries, but maybe you’re right and that’s exactly what it is. But I don’t write in order to solve anything. I’m really not interested in resolutions or conclusions. I want to move through something, find out what it is, spend time there, see what it’s like. That’s what I want the reader to experience as well. I want them to spend some time with my characters. I want to throw a party.

INTERVIEWER

That’s very much form fitting content. A Shock is filled with characters who are searching not necessarily for anything in particular. Hawthorn & Child revolves around mystery but resolves very few of the questions it raises. Is form a consideration you make after you start developing content, or are the two intertwined in a way that makes them inseparable?

RIDGWAY

I think they are inseparable. And to be honest they are so inseparable that I now largely forget how they each developed during the writing. I remember with Hawthorn & Child I hoped to write a much more fragmentary book. But a sort of coherence asserted itself. With A Shock it was almost the other way around. In the writing the shape just emerged, and at various points I realized various things—such as this bit is the middle, not the end. Actually once I got the middle, strangely, everything else fell into place around it.

INTERVIEWER

Do you see yourself writing toward a certain genre or as writing for any particular audience?

RIDGWAY

No, neither of those.

INTERVIEWER

I wouldn’t think so, but your work is often characterized as such—Hawthorn & Child being a detective novel, your work being situated within a kind of Modernist tradition. Do you identify with those monikers?

RIDGWAY

Not really, no. I like to read detective books. I don’t think Hawthorn & Child is one of those, but there is that other literary tradition of using that form, using the detective novel, or what looks like a detective novel, to do something else entirely. I suppose it belongs to that, but I tend not to think about those kinds of things, where I land or where I lie along the spectrum of literature.

INTERVIEWER

It may not be useful, right? Just do the work.

RIDGWAY

Yeah, I suppose just do the work. But I don’t even think about those things as a reader really.

INTERVIEWER

What are you reading now?

RIDGWAY

I’m reading Victor Serge for the first time, a book called The Case of Comrade Tulayev, which is quite something. And I’m reading a book of poetry by Caleb Femi, a poet from the South London neighborhood where I live now. The book is called Poor, and it’s fantastic. I’m going through that as slowly as I can. Savoring it.

INTERVIEWER

The dialogue in A Shock is handled with a kind of fluency that is almost transcriptive. It feels faithful and authentic, especially in “The Story,” which is the central chapter of the novel. What inspired you to lean toward that more naturalistic speech?

RIDGWAY

A Shock is about my neighbors. Not literally, but all the characters in the book live in Peckham and Camberwell in South London, where I’ve been living for a few years now. I didn’t try to capture any particular South London tone or voice or anything like that. But I wanted to get the sense of absurdity, the gallows humor, but also the kindness, in the way people here talk. People are funny. And I love dialogue that just lets people be the way they are. I like to allow characters to not quite listen to one another, or to talk over one another, or to misunderstand things, get things slightly wrong, say dumb things. I like the way the dialogue works like that, everything it reveals.

INTERVIEWER

That kind of realism manifests in a lot of ways in A Shock. I was struck by the way you render physical intimacy—the sexual honesty of your writing. Can you say a little about how sex plays a role in your work?

RIDGWAY

I don’t know what role it plays. It’s there. It’s part of the lives of the people I’m writing about. People get horny, right? What can you do? You have to let them do what they want. So I write about that. And it’s nice to hear you say there’s honesty in that, because I want it to be straightforward, if you like. This is just the way people are with each other, often, and it’s fine. It’s really fine. I don’t know to what extent it gets written about. I wanted to write about it, so I tried.

INTERVIEWER

Can we talk about rodents? A dead mouse kicks off your novel Animals, a rat makes an appearance in the third chapter of Hawthorn & Child, and A Shock is just littered with rodents. Why rodents?

RIDGWAY

I never even notice my obsessions. People read my books and say things like, You really like gay saunas. Or, You’re terrified of rodents. And I’m like, How did you know? I tend to write something and then forget about it as soon as it’s finished. I’m slightly startled—there’s a rat in Hawthorn & Child?

INTERVIEWER

It doesn’t play a big role. But mice play a big role in A Shock.

RIDGWAY

You know that therapy where you overcome your fear by exposing yourself to it? With that scene I think I was trying to write my way through my longtime fear of mice. Let’s just have as many mice as possible. I’m not sure it’s worked. I’m still very nervous about rodents of any description. I think that’s rational. Animals is a book I wrote a long, long time ago, but I was interested in the fragility of our constructed world, and how close it is to a very different world, and I’m not sure any of us are particularly well set up for dealing with that. And sometimes you get a sense of the peril. A flash of it. I reread Sartre’s Nausea recently and was amazed at how a lot of it had obviously found its way into my own thinking in Animals, and to some extent in Hawthorn & Child, and in A Shock as well.

INTERVIEWER

I’ve read that you don’t enjoy writing. Is that true?

RIDGWAY

No, I love writing. I don’t know where that came from. Oh, no, I do know where that came from. I was fed up with writing. So I stopped for a long time—I just didn’t bother anymore—but I came back to it a few years ago, and I really like it now. I get annoyed if I’m not able to do some writing. If I go a few days without having been able to do any writing, I start to get kind of angsty. Yeah, I enjoy it a lot.

INTERVIEWER

How did you come to writing initially?

RIDGWAY

Oh, Christ, I can’t remember. The roots of it are buried and no longer accessible to me. I read a lot as a kid, and reading has always made me want to write, right from the beginning. I don’t know quite how that works, what the mechanics of that are or the psychology of it, but if I read something fantastic, something I love, it makes me enthusiastic for writing. Reading has always been my biggest pleasure in terms of art. I think the answer is in there somewhere. I can’t remember. I’m really old now.

INTERVIEWER

I wouldn’t say you’re really old.

RIDGWAY

I feel really old.

INTERVIEWER

Fair enough. Your novels weave characters and motifs across places and time—beautiful in their structural complexity—expressing variations on common themes, often incorporating stories within stories. How much plotting takes place away from the page?

RIDGWAY

It’s pretty much all in my head. I do a lot of thinking, but I don’t sketch out plans or plots in advance of writing. At points in the past, I felt it would be a good idea if I did that, and I tried to do it. It’s never worked for me. I need to write my way into things and then I need to write my way out of them, and that seems to be how it works for me. But I do a lot of thinking. I imagine all writers do a lot of thinking, right? I don’t think I’m doing anything unusual there. I feel like I’m working hardest when I’m thinking, and then by the time I get to the page I kind of know what I want to do. So a lot of thinking and then the writing itself goes relatively quickly. Then I have to spend some time fixing it.

INTERVIEWER

When you’re working outside of a conflict-resolution model of storytelling, how do you know when a story is finished?

RIDGWAY

I was going to say that old, hackneyed thing—you don’t finish work, you abandon it—but I’m not sure that’s entirely true. I don’t feel I’m abandoning stuff. I think I get to a point where it feels like everything I wanted to put into the book is there, and I can’t work out a better way of organizing it. At that point it feels like I can’t do anything else, therefore the work must be finished. I think that’s how it works.

Christopher Notarnicola is a veteran of the U.S. Marine Corps and holds an M.F.A. from Florida Atlantic University. His work was featured in The Best American Essays 2017 and has been published in American Short Fiction, Bellevue Literary Review, Consequence Magazine, Image, North American Review, The Southampton Review, and elsewhere. Find him in Pompano Beach, Florida, and at christophernotarnicola.com.

July 7, 2021

Shirley Jackson’s Love Letters

Shirley Jackson, Photograph. CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Shirley Jackson is born in San Francisco, California, on December 14, 1916. Her father, Leslie, emigrated from England at age twelve with his mother and two sisters and became a successful self-made business executive with the largest lithography company in the city. Her mother, Geraldine, is a proud descendant of a long line of famous San Francisco architects and can trace her ancestry back to before the Revolutionary War.

Shirley grows up primarily in Burlingame, an upper-middle-class suburb south of the city. But when she is sixteen, Leslie is promoted and transferred, and the family moves—luxuriously, by ship, through the Panama Canal—to Rochester, in upstate New York. The Jacksons quickly join the Rochester Country Club and become well-established in the city’s active society world. The move is very hard on Shirley, who misses California and her friends there, especially her best friend, Dorothy Ayling. She finishes high school in Rochester (where one of her classes is once interrupted for a few minutes so that Shirley can marvel at snow falling outside the window), then attends the University of Rochester for one difficult year, before deciding to spend the next year writing alone in her room at home, with the lofty goal of producing a thousand words a day. Little of what Shirley writes during that period is believed to have survived.

She then enrolls at Syracuse University, where she enjoys literature classes, and where the university’s journal, The Threshold, publishes her story “Janice,” a one-page conversation with a young woman who brags that she has that day attempted suicide. Another literature student, Stanley Edgar Hyman, from Brooklyn, New York, the brash, intellectual son of a Jewish second-generation wholesale paper merchant, reads her story and vows on the spot to find and marry its author.

Shirley and Stanley meet on March 3, 1938, in the library listening room, and an intellectual connection quickly develops into a romantic one. These letters begin just three months after they’ve met, when both Shirley and Stanley are on summer break, she at home in Rochester and he at first at home in Brooklyn and then rooming with his friend Walter Bernstein at Dartmouth, then working at a paper mill in Erving, Massachusetts.

This is the earliest known surviving letter of Shirley’s. She is twenty-one, and Stanley is about to turn nineteen.

*

[To Stanley Edgar Hyman]

tuesday [June 7, 1938]

portrait of the artist at work. seems i brought a collection of miscellaneous belongings home from school, among them a c and c hat which bewilders goddamnthatword my little brother. he says if it’s a hat why doesn’t it have signatures all over it. mother seems to think i’m insane, and closes her eyes in a pained fashion when i call her chum. she also tells me that love or no love i have to eat and when i say eatschmeat she says what did you say and for a minute icy winds are blowing. there has been hell breaking loose ever since mother woke me this morning by telling me that that was a letter from dartmouth that the dog was eating. when she came in an hour later and found me reading the letter for the fifth time she began to be curious and asked me all sorts of questions about you. yes, she got it all. consequently there was a rather nice scene, me coming off decidedly the worse, since mother quite unfairly enlisted alta’s assistance and alta went and made a cake and i like cake. mother says, in effect: go on and be a damn fool but don’t tell your father. i had to cry rather loudly though. which means that you are going to meet a good deal more opposition than i had counted on. i think mother was mad because she took your long distance call the other day and the big shot was expecting an important business call and he was quite excited when the operator said that the party at the other end of the line wasn’t going to pay. yes, and mother says to tell you that any more letters arriving with postage due and she will either steam the letters open since they belong to her since she practically bought them or she will start taking the postage out of my allowance.

however all in all she is being rather sweet, and more intelligent than i gave her credit for, since she absolutely refuses to forbid me to see you which means that now i have no reason to be romantically clandestine. disappointing when i’d already picked out a hollow oak tree. which brings me to the point: if you love me so damn much why don’t you come out and say so? looked all through your letter to find out if you loved me and you refuse to say. damn you anyway. i love you you dope.

notice if you haven’t already that i have borrowed your distinctive writing style with ideas of my own such as no punctuation which is a good idea since semi-colons annoy me anyway. and incidentally i read mother the poem at the top of the pages in your letter and she translated it for me, she knows french and i don’t but even then it wasn’t such a good idea. i also told father all about communism which was wrong, wasn’t it. he said really in a whatthehelldoyouknowaboutlifeyoushelteredvictorianflower sort of voice.

also. y snarls deep down in her throat whenever i mention you which idoratheroftenchum. she thinks you’re a nice sweet child, only it’s too bad you had to fall into my clutches. i managed to get to talking before she did so now she knows all my troubles and i don’t know any of hers. ’tanley i think i’ll come to new york and get laid. oooooooooh yes. my mother mayhertribeincrease had been reading liberty that oracle of the masses and has discovered that eight out of ten college students are all for immorality. she has been asking me leading questions until i came out and said that if she meant had i preserved the fresh bloom of dewy innocence yes i had but it hurt me a damn sight more than it ever hurt liberty. mother is reassured but not too happy about the whole thing, having doubts.

i didn’t know y was an ardent communist but she is, but then she was a vegetarian once too. we’re going to drink beer, and i mean that we’re going to drink lots of beer. but quantities. we have sorrows to drown.

about our mutual friend Michael. he brought the scamp … boat … in fifth in saturday’s race and mother saw him that night and he was plenty drunk and getting drunker and the damnfool insulted mother in some way and now she’s mad and michael can’t come see me till mother is appeased and he’ll never remember that he said anything wrong till someone meaning me reminds him. are you happier than formerly?

s.edgar. it’s so silly to write this junk when all i want to say is i can’t stand it i won’t wait four months i love you. what am i going to do? it’s not going to be long, is it? it’ll be september soon, won’t it? like hell it will.

shan’t go on like that. i’m going to Be Brave. bloody, but unbowed. going to be a debutante. yeah. i’m going to count the days and minutes till september. think of me sometimes, won’t you, chum. hell. wish i could think of a good quotation to top that paragraph off with.

i shall go on writing revolutionary poetry as long as i damn well please. i just thought of a good line: capitalists unite you have a world to win and nothing to lose but your chains …

dearest, be a good boy, and do wear your rubbers, for mother’s sake, now won’t you?

darling!

p.s. s. edgar; goddamn your lying soul why did you have to go away and leave me? I love you so much.

s.

*

[To Stanley Edgar Hyman]

[June 8, 1938]

hawney!

every time i get a letter from you, which seems to be an event happening with astonishing frequency, i think of more things i want to say to you, most of them being i love you but that’s beside the point. so it has come to the position where i write you every day because you write me every day and i hope you like the idea. anyway i like to write letters in your style because i don’t have to hunt for the shiftkey and because it’s easier on ernest, who is typewriter, and makes him very happy because he is lazy too.

this is gibbering

and it looks like e e cummings, who y said my revolutionary poetry reminded her of and when i asked her what that meant she said she didn’t like e e cummings either.

i know that should be whom

stop correcting me

you better go easy on my mother. she is getting amused by this faithful in my fashion idea and says she thinks you must be an awful dope to expect me to learn to cook. moreover she wants to know why she can’t read your letters. i told her it was secret propaganda but that didn’t help much either. she is having her reading club here this afternoon which means that she expects me to pour tea but that ain’t all she expects. she says: now, darling, please for my sake put on a decent dress and do something with your hair, and you might even do your fingernails something quiet if you can, and will you be polite to my guests, after all they may be society but some of them are really quite nice and if you’ll only be nice like i said i might buy you that silly book.

that silly book being fearing if i can get it

so i put up my hair

but that ain’t gonna stop me from flapping my eyelashes at miss macarty who is the dame what reviews the book and saying sweetly: do you like cathedral close, dear? don’t you think it’s too, too wonderful, and what about eliot? i adore eliot, but robert frost? so much horse-shit, as i know you will be the first to say. you do have such a wonderful grasp of literature, dear.

if that doesn’t finish mother with the reading club i have lived in vain.