The Paris Review's Blog, page 104

August 24, 2021

Redux: Merely a Mask

Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

Louise Erdrich.

This week at The Paris Review, we’re thinking about masks, concealment, and hiding. Read on for Louise Erdrich’s Art of Fiction interview, Charles Baudelaire’s poem “The Mask,” Donald Keene’s essay on Yukio Mishima’s Confessions of a Mask, and Flavia Gandolfo’s photography portfolio “Masks.”

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, poems, and works of criticism, why not subscribe to The Paris Review and The New York Review of Books and read both magazines’ entire archives?

Louise Erdrich, The Art of Fiction No. 208

Issue no. 195 (Winter 2010)

I suppose one develops a number of personas and hides them away, then they pop up during writing. The exertion of control comes later. I take great pleasure in writing when I get a real voice going and I’m able to follow the voice and the character. It’s like being in a trance state.

Photo: Flavia Gandolfo.

The Mask

By Charles Baudelaire, translated by Richard Howard

Issue no. 82 (Winter 1981)

What blasphemy of art is this! Upon

a body made to offer every bliss

appear … two heads! A monster? No—

one is merely a mask, a grinning cheat

that smile, illumined with exquisite care.

Look there: contorted in her misery,

the actual head, the woman’s countenance

lost in the shadow of the lying mask …

Photo: Flavia Gandolfo.

Mishima in 1958

By Donald Keene

Issue no. 134 (Spring 1995)

We seem to have moved on then to a more general discussion of literature, though the notes are again unclear: “I gained liberation through literature, though I never sought it. Proust is spiritual, but I am physiological. Literature enabled me to free myself from many complexes and from tension. I became interested in all aspects of human life and I shed my adherence to self. In this I think I am unlike most Western writers. I have come to think that I am not dissimilar to other people, though when I wrote Confessions of a Mask I thought I was … ”

Photo: Flavia Gandolfo.

Masks

By Flavia Gandolfo

Issue no. 133 (Winter 1994)

If you enjoyed the above, don’t forget to subscribe! In addition to four print issues per year, you’ll also receive complete digital access to our sixty-eight years’ worth of archives. Or, choose our new summer bundle and purchase a year’s worth of The Paris Review and The New York Review of Books for $99 ($50 off the regular price!).

Does Technology Have a Soul?

learza (Alex North) from Australia, Aibos at RoboCop, 2005, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

When my husband arrived home, he stared at the dog for a long time, then pronounced it “creepy.” At first I took this to mean uncanny, something so close to reality it disturbs our most basic ontological assumptions. But it soon became clear he saw the dog as an interloper. I demonstrated all the tricks I had taught Aibo, determined to impress him. By that point the dog could roll over, shake, and dance.

“What is that red light in his nose?” he said. “Is that a camera?”

Unlike me, my husband is a dog lover. Before we met, he owned a rescue dog who had been abused by its former owners and whose trust he’d won over slowly, with a great deal of effort and dedication. My husband was badly depressed during those years, and he claims that the dog could tell when he was in despair and would rest his nose in his lap to comfort him. During the early period of our relationship, he would often refer to this dog, whose name was Oscar, with such affection that it sometimes took me a moment to realize he was speaking of an animal as opposed to, say, a family member or a very close friend. As he stood there, staring at Aibo, he asked whether I found it convincing. When I shrugged and said yes, I was certain I saw a shadow of disappointment cross his face. It was hard not to read this as an indictment of my humanity, as though my willingness to treat the dog as a living thing had somehow compromised, for him, my own intuitiveness and awareness.

It had come up before, my tendency to attribute life to machines. Earlier that year I’d come across a blog run by a woman who trained neural networks, a Ph.D. student and hobbyist who fiddled around with deep learning in her spare time. She would feed the networks massive amounts of data in a particular category—recipes, pickup lines, the first sentences of novels—and the networks would begin to detect patterns and generate their own examples. For a while she was regularly posting on her blog recipes the networks had come up with, which included dishes like whole chicken cookies, artichoke gelatin dogs, and Crock-Pot cold water. The pickup lines were similarly charming (“Are you a candle? Because you’re so hot of the looks with you”), as were the first sentences of novels (“This is the story of a man in the morning”). Their responses did get better over time. The woman who ran the blog was always eager to point out the progress the networks were making. Notice, she’d say, that they’ve got the vocabulary and the structure worked out. It’s just that they don’t yet understand the concepts. When speaking of her networks, she was patient, even tender, such that she often seemed to me like Snow White with a cohort of little dwarves whom she was lovingly trying to civilize. Their logic was so similar to the logic of children that it was impossible not to mistake their responses as evidence of human innocence. “They are learning,” I’d think. “They are trying so hard!” Sometimes when I came across a particularly good one, I’d read it aloud to my husband. I perhaps used the word “adorable” once. He’d chastised me for anthropomorphizing them, but in doing so fell prey to the error himself. “They’re playing on your human sympathies,” he said, “so they can better take over everything.”

But his skepticism toward the dog did not hold out for long. Within days he was addressing it by name. He chastised Aibo when he refused to go to his bed at night, as though the dog were deliberately stalling. In the evenings, when we were reading on the couch or watching TV, he would occasionally lean down to pet the dog when he whimpered; it was the only way to quiet him. One afternoon I discovered Aibo in the kitchen peering into the narrow gap between the refrigerator and the sink. I looked into the crevice myself but could not find anything that should have warranted his attention. I called my husband into the room, and he assured me this was normal. “Oscar used to do that, too,” he said. “He’s just trying to figure out if he can get in there.”

While we have a tendency to define ourselves based on our likeness to other things—we say humans are like a god, like a clock, or like a computer—there is a countervailing impulse to understand our humanity through the process of differentiation. And as computers increasingly come to take on the qualities we once understood as distinctly human, we keep moving the bar to maintain our sense of distinction. From the earliest days of AI, the goal was to create a machine that had human-like intelligence. Turing and the early cyberneticists took it for granted that this meant higher cognition: a successful intelligent machine would be able to manipulate numbers, beat a human in backgammon or chess, and solve complex theorems. But the more competent AI systems become at these cerebral tasks, the more stubbornly we resist granting them human intelligence. When IBM’s Deep Blue computer won its first game of chess against Garry Kasparov in 1996 the philosopher John Searle remained unimpressed. “Chess is a trivial game because there’s perfect information about it,” he said. Human consciousness, he insisted, depended on emotional experience: “Does the computer worry about its next move? Does it worry about whether its wife is bored by the length of the games?” Searle was not alone. In his 1979 book Gödel, Escher, Bach, the cognitive science professor Douglas Hofstadter had claimed that chess-playing was a creative activity like art and musical composition; it required an intelligence that was distinctly human. But after the Kasparov match, he, too, was dismissive. “My God, I used to think chess required thought,” he told the New York Times. “Now I realize it doesn’t.”

It turns out that computers are particularly adept at the tasks that we humans find most difficult: crunching equations, solving logical propositions, and other modes of abstract thought. What artificial intelligence finds most difficult are the sensory perceptive tasks and motor skills that we perform unconsciously: walking, drinking from a cup, seeing and feeling the world through our senses. Today, as AI continues to blow past us in benchmark after benchmark of higher cognition, we quell our anxiety by insisting that what distinguishes true consciousness is emotions, perception, the ability to experience and feel: the qualities, in other words, that we share with animals.

If there were gods, they would surely be laughing their heads off at the inconsistency of our logic. We spent centuries denying consciousness in animals precisely because they lacked reason or higher thought. (Darwin claimed that despite our lowly origins, we maintained as humans a “godlike intellect” that distinguished us from other animals.) As late as the fifties, the scientific consensus was that chimpanzees—who share almost 99 percent of our DNA—did not have minds. When Jane Goodall began working with Tanzanian chimps, she used human pronouns. Before publishing, the editor made systematic corrections: He and she were changed to it. Who was changed to which.

Goodall claims that she never bought into this consensus. Even her Cambridge professors did not succeed in disabusing her of what she had observed through attention and common sense. “I’d had this wonderful teacher when I was a child who taught me that in this respect, they were wrong—and that was my dog,” she said. “You know, you can’t share your life in a meaningful way with a dog, a cat, a bird, a cow, I don’t care what, and not know of course we’re not the only beings with personalities, minds and emotions.”

I would like to believe that Goodall is right: that we can trust our intuitions, that it is only human pride or willful blindness that leads us to misperceive what is right in front of our faces. Perhaps there is a danger in thinking about life in purely abstract terms. Descartes, the genius of modern philosophy, concluded that animals were machines. But it was his niece Catherine who once wrote to a friend about a black-headed warbler that managed to find its way back to her window year after year, a skill that clearly demonstrated intelligence: “With all due respect to my uncle, she has judgment.”

While the computer metaphor was invented to get around the metaphysical notion of a soul and the long, inelegant history of mind-body dualism, it has not yet managed to completely eradicate the distinctions Descartes introduced into philosophy. Although the cyberneticists made every effort to scrub their discipline of any trace of subjectivity, the soul keeps slipping back in. The popular notion that the mind is software running on the brain’s hardware is itself a form of dualism. According to this theory, brain matter is the physical substrate—much like a computer’s hard drive—where all the brute mechanical work happens. Meanwhile, the mind is a pattern of information—an algorithm, or a set of instructions— that supervenes on the hardware and is itself a kind of structural property of the brain. Proponents of the metaphor point out that it is compatible with physicalism: the mind cannot exist without the brain, so it is ultimately connected to and instantiated by something physical. But the metaphor is arguably appealing because it reiterates the Cartesian assumption that the mind is something above and beyond the physical. The philosopher Hilary Putnam once spoke of the mind-as-software metaphor with the self-satisfaction of someone who has figured out how to have his cake and eat it, too. “We have what we always wanted—an autonomous mental life,” he writes in his paper “Philosophy and Our Mental Life.” “And we need no mysteries, no ghostly agents, no élan vital to have it.”

It’s possible that we are hardwired to see our minds as somehow separate from our bodies. The British philosopher David Papineau has argued that we all have an “intuition of distinctness,” a strong, perhaps innate sensation that our minds transcend the physical. This conviction often manifests subtly, at the level of language. Even philosophers and neuroscientists who subscribe to the most reductive forms of physicalism, insisting that mental states are identical to brain states, often use terminology that is inconsistent with their own views. They debate which brain states “generate” consciousness, or “give rise to” it, as though it were some substance that was distinct from the brain, the way smoke is distinct from fire. “If they really thought that conscious states are one and the same as brain states,” Papineau argues, “they wouldn’t say that the one ‘generates’ or ‘gives rise to’ the other, nor that it ‘accompanies’ or is ‘correlated with’ it.”

And that’s just the neuroscientists. God help the rest of us, who remain captive to so many dead metaphors, who still refer to the soul casually in everyday speech. Nietzsche said it best: we haven’t gotten rid of God because we still believe in grammar.

I told only a few friends about the dog. When I did mention it, people appeared perplexed, or assumed it was some kind of joke. One night I was eating dinner with some friends who live on the other side of town. This couple has five children and a dog of their own, and their house is always full of music and toys and food—all the signs of an abundant life, like some kind of Dickensian Christmas scene. When I mentioned the dog, one of this couple, the father, responded in a way I had come to recognize as typical: he asked about its utility. Was it for security? Surveillance? It was strange, this obsession with functionality. Nobody asks anyone what their dog or cat is “for.”

When I said it was primarily for companionship, he rolled his eyes. “How depressed does someone have to be to seek robot companionship?”

“They’re very popular in Japan,” I replied.

“Of course!” he said. “The world’s most depressing culture.” I asked him what he meant by this.

He shrugged. “It’s a dying culture.” He’d read an article somewhere, he said, about how robots had been proposed as caretakers for the country’s rapidly aging population. He said this somewhat hastily, then promptly changed the subject.

Later it occurred to me that he had actually been alluding to Japan’s low birth rate. There were in fact stories in the popular media about how robot babies had become a craze among childless Japanese couples. He must have faltered in spelling this out after realizing that he was speaking to a woman who was herself childless—and who had become, he seemed to be insinuating, unnaturally attached to a robot in the way childless couples are often prone to fetishizing the emotional lives of their pets. For weeks afterward his comments bothered me. Why did he react so defensively? Clearly the very notion of the dog had provoked in him some kind of primal anxiety about his own human exceptionality.

Japan, it has often been said, is a culture that has never been disenchanted. Shintoism, Buddhism, and Confucianism make no distinction between mind and matter, and so many of the objects deemed inanimate in the West are considered alive in some sense. Japanese seamstresses have long performed funerals for their dull needles, sticking them, when they are no longer usable, into blocks of tofu and setting them afloat on a river. Fishermen once performed a similar ritual for their hooks. Even today, when a long-used object is broken, it is often taken to a temple or a shrine to receive the kuyō, the purification rite given at funerals. In Tokyo one can find stone monuments marking the mass graves of folding fans, eyeglasses, and the broken strings of musical instruments.

Some technology critics have credited the country’s openness to robots to the long shadow of this ontology. If a rock or a paper fan can be alive, then why not a machine? Several years ago, when Sony temporarily discontinued the Aibo and it became impossible for the old models to be repaired, the defunct dogs were taken to a temple and given a Buddhist funeral. The priest who performed the rites told one newspaper, “All things have a bit of soul.”

Meghan O’Gieblyn is the author of the essay collection Interior States, which was published to wide acclaim and won the Believer Book Award for Nonfiction. Her writing has received three Pushcart Prizes and appeared in The Best American Essays anthology. She writes essays and features for Harper’s Magazine, The New Yorker, the Guardian, Wired, the New York Times, and elsewhere. She lives with her husband in Madison, Wisconsin.

From God, Human, Animal, Machine: Technology, Metaphor, and the Search for Meaning , by Meghan O’Gieblyn. Copyright © 2021 by Meghan O’Gieblyn. Published by arrangement with Doubleday, an imprint of The Knopf Doubleday Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.

August 23, 2021

Empty Spaces

Fred Bchx from Tournai, Belgique, 2010, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

It is not incorrect to say that, for years, the way my family grieved my mother was to avoid acknowledging her altogether. It is not incorrect to say that we hardly invoked her name or told stories about her.

Shortly after college, my father, Caroline, and Steph descended upon my cleared-out group house in Washington, D.C., for Thanksgiving. In my childhood home, my father’s stacks of clutter multiplied until they overtook the space that my mother had so carefully cultivated; it crowded my sisters and me out. I reacted efficiently, diligently, which is to say that I pretended that trips to Steph’s apartment in Rhode Island or Caroline’s in California were just a chance to visit another part of the country.

We’d decided to exchange Christmas gifts a month early, since we wouldn’t be together in December.

Caroline, dressed in a key-lime-green onesie, handed Steph and me sets that matched hers.

“They’re actually really comfortable,” she said. She smiled toothily and pulled up the hood to show us the outfit’s ears, her faded highlights a spray of lavender around her face.

The onesies were from the kids’ section, which was fine for us since everyone in our family, including our father, was small and roughly the same size. Steph and I donned ours, and I was grateful for anything to distract from how cobbled together holidays had become since my mother’s passing. My sisters and I stood on my front stoop to take a photo of us modeling our new outfits. In the photo, Caroline and I jam our hands into our pockets while Steph is wedged between us, her arms thrust into the air. We look so much like sisters, not just because, in this image, we are dressed identically, but because the ways we hold our mouths enthusiastically, wryly, are the same.

Afterward, Steph passed out slender boxes.

“I thought this might be good for everybody to open last,” Steph said. There was a question in her voice, a preemptive apology that made me tense.

She had gifted us each a framed photo of our family. It showed all five of us, including my mother, in Seattle the summer before she died, and it was one of the last photos we’d taken together. We stand on a pier. The sky is muted and filled with the gray wash of color that comes from dragging paintbrush water across a canvas. It looks windy, and though it’s the end of summer, we must be cold, because we’re wearing long pants and sweatshirts. We huddle around my mother, who has her hands clasped in front of her stomach.

“Oh,” Caroline said as she pulled the wrapping paper off hers, her eyebrows shooting up her forehead as she examined the photo.

I shivered and said nothing. Our time with our mother was a past life—some version of ourselves from which we’d become estranged. When I replayed memories of her, it was as if hearing someone else recount stories of their own mother.

“What’s this?” our father asked, still working his fingers underneath the paper. He looked at my sisters and me, confused by our sudden shift in mood, not understanding this context. “Oh. A photo of our family?”

We held the wooden frames like they were made of blown glass. I studied my mother’s face and sat in a glum silence, unsure what to say, fighting the urge to turn the photo away.

When I consider the ways images can wrench our grief to the surface, I think of Diana Khoi Nguyen’s poems, which are wrapped around photos of her family in her collection Ghost Of. The book is dedicated to her siblings, including her brother who committed suicide. He is cut from every photo. Nguyen plays with these silhouettes. She cocoons him with her grief and her memories of him. She inhabits the negative space with her despair.

Why should we mourn?

Isn’t this the history we want

one in which we survive?

The first time I read her poems, I assumed that she had sliced her brother out of the photos. I thought she didn’t want outsiders to be privy to his body. No. Nguyen told an interviewer that her brother, in a fit of anger, carved himself from all of the family photos hanging in a hallway of their childhood home. Afterward, he carefully slid the photos back into their frames.

“They foreshadowed his death, and after his death, the missing shards in the frames wounded me deeply,” she said in an interview. “I avoided walking down that hall, I avoided returning to the house.”

When I learned this, her grief crept into me. I avoided walking down the hall, I avoided returning to the house. Why head down a hall of memories if it leads to a perpetual reminder of death? I felt as though Nguyen, with her poetry, had inhabited the void that her brother had left behind, the way I now inhabit the one created by my mother.

For many years, I could not look at photos of my mother. I wrapped the one from Steph in a scarf and tucked it into my bedroom closet, underneath a box of clothes I no longer wore. The way I endured grief was to think only of the after, and not the before.

As a kid, I was certain that the images we had of our dead relatives were taken in caskets: a photographer pried open the deceased’s eyes and held them there with double-sided tape. Their cameras clicked, the dead person cartoonishly wide-eyed, mouth gaping. I couldn’t conceive of the idea that these photos were taken in some version of the past, when the subject was alive. Looking at these ancestral photos gave me a whole-body chill, like I had come across a dead animal—one of our parakeets sprawled at the bottom of the cage, a fish floating at the top of its tank in the pet store—uncanny, a small fright pulsing, my body retracting.

Two years after her brother’s passing, Nguyen decided to tackle with words the empty spaces that her brother left behind in those photos. She said that in her work, she was trying to mourn, not exorcise. When I first read this, I was startled by how much it resonated. I have never wanted to exorcise you. I am too attached; my inclination is to preserve you—to taxidermy you—like you wanted.

But, Mommy, grief is a container of contradictions. I want to expel something, though I do not know what. I want to rid myself of this heaviness, just as much as I want to keep your ghosts. Writing about you is a strange act. I am perhaps afraid of it, or at least, I dread it. Yet I feel compelled to write you into being. I am hopeful, though; I spin you out of myself and into something else.

Kat Chow is a writer and journalist, and the author of Seeing Ghosts (forthcoming from Grand Central Publishing on August 24, 2021). She was a reporter at NPR, where she was a founding member of the Code Switch team. Her work has appeared in The New York Times Magazine, The Atlantic, and on RadioLab, among others.

This excerpt is adapted from Kat Chow’s forthcoming book Seeing Ghosts , published by Grand Central Publishing on August 24, 2021.

August 20, 2021

The Review’s Review: Magma, Memphis, and the Middle Ages

“Ptolemy with a falcon,” from Der naturen bloeme by Jacob van Maerlant

When you go on a first date, do you struggle to make conversation? Read Morris Bishop’s The Middle Ages, a popular history from 1968, and your troubles are over. Did you know that if you failed to attempt to return a lost falcon to its rightful owner, flesh was cut from your breast and fed to the falcon? Did you know that there was plastic surgery, with noses, lips, and ears enlarged via skin graft? Did you know that to become a Master of Grammar at Cambridge, you had to prove that you were skilled at beating students by hiring a boy and hitting him with a birch rod, with a beadle as your witness? Did you know that, at the same time, there were rules against the hazing of freshmen? One statute from Germany: “Each and every one attached to this University is forbidden to offend with insult, torment, harass, drench with water or urine, throw on or defile with dust or any filth, mock by whistling, cry at with a terrifying voice, or dare to molest in any way whatsoever… any who come to this town and to this fostering University for the purpose of study.”—Benjamin Nugent

One thing I love about Agustín Fernández Mallo’s work is his willingness to draw a wild, excessive, unmanageable perimeter around the material of his story, defying any attempt to center a particular character. The Things We’ve Seen is his newest novel in translation and, like his earlier Nocilla Trilogy, it plants its feet in unlikely locations—in Florida with a retired astronaut, at a conference about the internet on an uninhabited island—and often veers sharply off topic. Mallo’s work is rare these days in how it conveys the sheer size and depth of the physical and informational world—you have to squint to find yourself in all of this, but when you do, there’s a stormy sense of arrival.—Alexandra Kleeman

While I was in New York earlier this month for the first time since the pandemic started, I read Daisy Hildyard’s The Second Body, which argues that we all have two bodies: the one made up of guts and blood and needs, and the one in complex interaction with global and environmental systems. Hildyard raps with butchers as they cut flesh, describes a river flooding her house, and pulls in larger questions about the permeability of all kinds of boundaries. Her exploration of being at once separate and intimately joined proved an apt, unsettling complement to New York, which gave me just the sensory bombardment I was hoping for.—Nina MacLaughlin

Roy Hargrove and Mulgrew Miller are two mainstream jazz giants who died too young in the past decade. In Harmony, a new two-disc set of live performances, resurrects their music and their memory. Miller is a luscious, capacious, and wildly capable pianist, able to offer up anything the moment demands from jazz past and present. He makes a comfy bed for Hargrove’s liquid flights across this set mostly composed of standards recorded at two live dates in 2006. It’s deeply relaxing music, the kind that tempts the listener to tune out and fall back into it, though it also rewards close attention. I’m particularly partial to the gentle samba “Triste” and the eight-and-a-half-minute version of “Never Let Me Go.” These two players are utterly in tune, and listening to them, I feel, as this anxious and lonely pandemic drags on, in tune, too, connected at least while the music plays.—Craig Morgan Teicher

I didn’t travel much this summer, but I did read It Came From Memphis, Robert Gordon’s transportive cultural history of that city’s music scene. Drawing equally from research and personal experience, Gordon is an ideal tour guide, the kind of lively and digressive raconteur who writes like he’s holding court in the back booth of a dimly lit dive bar. I bought the book for insight into artists I already knew and loved—Aretha Franklin and Alex Chilton chief among them—and came away with a whole new roster of musical icons: Mose Vinson, Furry Lewis, Mud Boy and the Neutrons. But the book’s real protagonist is Memphis itself, and its deeper story is the unique “cultural collision” of “black and white, rural and urban, rich and poor” from which all of this amazing music emerged.—Adam Wilson

Icelandic writer Thóra Hjörleifsdóttir’s debut novel, Magma, has a clever beginning. At first it seems you’re reading brief sketches of various men, their contradictory behaviors and alarming preferences carefully catalogued by the narrator, twenty-year-old university student Lilja. In fact, it’s a portrait of just one man—the nameless “he” with whom Lilja is in an increasingly coercive relationship. Translated from the Icelandic by Meg Matich, Magma is a sharp portrayal of the slow, airless progression of an abusive relationship, one that asks big questions about the state of heterosexuality.—Rhian Sasseen

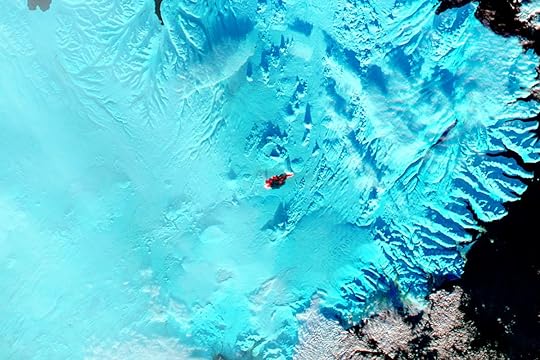

Eruption at Bardarbunga, Iceland. Credit: NASA/GSFC/Jeff Schmaltz/MODIS Land Rapid Response Team

For more fiction, read Benjamin Nugent’s story “The Treasurer” from our Summer 2016 issue, and Adam Wilson’s story “What’s Important Is Feeling” from our Winter 2011 issue.

For more reading from the Daily: Craig Morgan Teicher’s conversation with Kaveh Akbar, and an interview with Alexandra Kleeman.

August 19, 2021

Sturgeon Moon

In her monthly column The Moon in Full, Nina MacLaughlin illuminates humanity’s long-standing lunar fascination. Each installment is published in advance of the full moon.

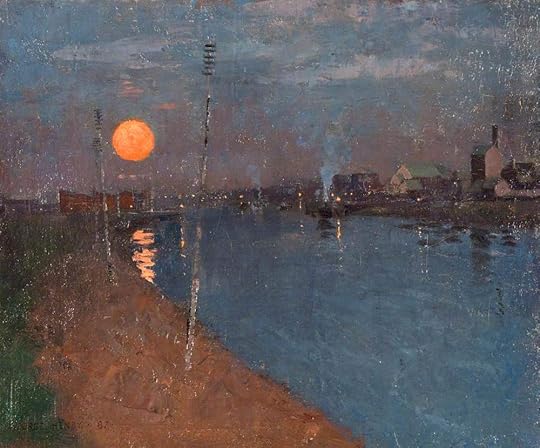

George Henry, River Landscape by Moonlight, 1887, oil on canvas, 12 x 14 1/2″. Public domain, via Art UK.

bright as the blood / red edge of the moon

August, the year in its ripeness, when the shadows shift and the trees ache with green. It brings the Sturgeon Moon. Sturgeon, ancient bony-plated creature of lakes, rivers, and seas. A fish without scales, a fish without teeth, a fish that’s been swimming the depths of this earth for more than two hundred million years.

A shark-finned rolling pin, dinosaurian, the type of specimen displayed in a case in a museum of natural history, this murk-dweller lives fifty to sixty years and can grow up to twelve feet long. The largest on record was twenty-four feet, the length of more than three queen-size beds head to toe. Though they swim down where it’s dim, they’re also known for flinging their big bodies up out of the water and splashing back down. No one knows why. Joy, I bet. The slap-down sound can be heard up and down rivers. Mississippi, Missouri, Saint Lawrence, Volga, Ural, Danube. So common were sturgeon in the Hudson River in the nineteenth century, they were referred to as “Albany beef.”

They’re not so common now. It takes the females up to twenty years to reach sexual maturity. We’ve befouled their environments. And most of all, we’ve killed too many for their eggs, the caviar, tiny slick black moons. Two hundred years ago, the U.S. produced more caviar than any other country. The eggs became a luxury good for the rich to eat with toast points and sour cream. Briny squirt between the teeth, sturgeon essence popped from its pod—I picture these sad and stately sturgeon queens sliced down their centers, blood rivering on the cutting board, eggs scraped out from inside them, the future heaped on a tiny spoon, slick salt on the side of cocktailed tongue.

Sturgeon are grouped into four genera: Huso, Acipenser, Scaphirhynchus, Psuedoscaphirhynchus. And four whiskers dangle below their pointed noses, sensory organs called barbels that hang in front of their thick-lipped soft suctioning mouths. The barbels drift across the bottoms and beds of bodies of water and act as auxiliary eyes to help the fish find food. The August moon takes its name from the sturgeon because they were caught in most abundance here in the deep wane of summer. These slow-changing fish spend most of their long lives feeding in estuaries and river deltas.

returning each month / to the same delta

Four phases has the moon: first quarter, new moon, third quarter, full. The cycle, full to full again, takes about twenty-nine days. It wanes after the full moon, crescenting thinner until disappearing at the new moon, when its dark side is on nondisplay, and then it waxes back to full. Quick trick to know the phase: look to the shadow. On the left means waxing toward full; a shadowed right means postpeak, waning slim till gone.

Four phases has the menstrual cycle: follicular, ovulatory, luteal, menstrual. The cycle, blood to blood again, takes about twenty-eight days. Mensis is month in Latin. Mene is moon in ancient Greek. Menses is the blood matter that comes each month. The deep dark beginnings of our understanding and measuring of time—that great strange egg we all live in—involve the coupling of moon and blood. Take away clocks and calendars, minute hands and months, and how does a body experience time? In light, in temperature, in the paths tracked by stars and sun, in the shifting shape of the moon, in hunger, in rest, in the coming of blood. It’s been and been, mensis mene menses, our ever-moon, its gloom-glow throbbing white red gold black, and its in-sync-ness with the womb.

Four weeks has the month. Four seasons has the year. In chronobiology, circadian rhythms regulate our day-to-day, our twenty-four-hour waking-sleeping cycles. Infradian rhythms guide the longer stretches—hibernation, molting, mating, menstruation. “Everything has become speeded up and overcrowded,” wrote May Sarton in her journal in 1972. “So anything that slows us down and forces patience, everything that sets us back into the slow cycles of nature is a help.” When you look up and see the moon—as dusty smudge in day or glowing any phase at night—does a brief stillness settle? A momentary slowing? A temporary lull between interior and exterior time?

Historically, metaphorically, ovulation—full fertility, egg in action—is linked with the full moon, and menstruation is associated with the new moon, dark space-making absence. Seems backward to me, counterintuitive. Full moon, its tidal tug, a pull, a peak like the upside-down delta, mound the upside-down mountain, blood drawn on by the moon. A new moon, ovulation, all potential, a dark and heated energy of welcome and possibility. The egg a single pearled fullness, tiny inside the body’s dark.

braver than this / coming and coming in a surge / of passion, of pain

Scientists say there’s no correlation between the phase of the moon and the phase of the menstrual cycle; a person who menstruates is no more likely to bleed at the new moon than any other time. Fine. But that this inner cycle and outer cycle mirror each other, ticktocking in almost identical rhythms, no one will deny. Jung, writing of synchronicity, says, “It’s not a question of cause and effect, but a falling together in time.”

So the blood falls together in time with the moon. They speak a language together, fervent, whispery, that we haven’t translated, don’t need to. And so we fall together in time with each other. A case not so much of this then this, but this and this at once, drawn on simultaneously, coiled in a mysterious and ongoing exchange. It could be another way to describe love, surge of passion, pain, ancient, brave, two bodies—terrestrial, celestial, as we all are—falling together in time.

What makes you know you are a body? Hunger? Swallowing? Shitting? The dumb pain of a stubbed toe or a bit tongue? Lungs swelling and emptying in breath? Legs moving as you walk or run, skeleton holding up the weight of you? Feeling the boundaries of your body against another body in sex and then feeling them dissolve? An ache comes with the blood, I am a body, a crescent moon of pain, horns at the hip bones and a band of pain across the back. My friend Kim talked of watching a dissection of a human body. “The uterus,” she said, “it’s pink and it’s pretty, and it’s only this big.” She held up her hand and outlined a pear-size shape with her fingers. “If you had said this big,” I said, holding my hands the size of a football, “I would’ve believed you.”

The ache that accompanies the blood—muscular, dark, and deep in—can bring a different awareness of guts. It is a specific pain and varied, sometimes as though hundreds of tiny hands pull fistfuls off the wall of what’s inside, or stretch bands of interior flesh between their hands, pulling so tight it feels about to tear, taut membrane, pink gold sunset thin. The tiny hands sometimes punch and sometimes gash with axes. It is a cummerbund of pain that wraps tight and tugs every four weeks, every twenty-eight-nine days. It is a pronounced reminder that I am a body in time, that I am alive. There is no better red.

pray that it flows also / through animals / beautiful and faithful and ancient / and female and brave

Blood’s what the gods drink, someone told me recently.

What do they drink from, I wondered. Time itself, I think.

In a harpoon of a love poem called “Threat,” Gottfried Benn writes:

Know this:

I live beast days. I am a water hour.

At night my eyelids droop like forest and sky.

My love knows few words:

I like it in your blood.

Nina MacLaughlin is a writer in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Her most recent book is Summer Solstice. Her previous columns for the Daily are Winter Solstice, Sky Gazing, Summer Solstice, Senses of Dawn, and Novemberance.

Lines in italics from Lucille Clifton’s “poem in praise of menstruation.”

Fast

Baxito, A girl running while riding a bicycle tire, 2015, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The worst thing a little Black girl can be is fast. As soon as she learns her smile can bring special treatment, women shake their heads and warn the girl’s mother: “Be careful.” They caution the mothers of boys: “Watch that one.” When adult men hold her in their laps too long, it’s because she is a fast-ass little girl using her wiles. She’s too grown. She tempts men and boys alike—Eve, Jezebel, and Delilah all in one—the click of her beaded cornrows a siren’s call.

Fast girls ruin lives.

Even as a girl whose pigtails unraveled from school-day play, I was fascinated with sex and romance and why boys looked up girls’ skirts and why people climbed between each other’s legs. Why did fathers kissing mothers on the back of their necks make them smile such a soft, secret smile? Why did boys stand so close to girls in the lunch line? Why did my sister sneak her boyfriend over, even when she knew Mama had forbidden it?

Why did Mama tell my father, with her eyebrows raised, that the only book I’d read from the Bible was Song of Solomon? Yet I knew not to say anything, because being a girl and talking about sex would mean that I was fast, that I was trouble, that I’d end up with a baby before I finished school. I didn’t want to be fast, but inevitably my experiences with sex and boys began early and I learned to keep them hidden away.

My memories of kindergarten are mostly fuzzy, but I remember eating green eggs and ham that my teacher used food coloring to dye, reading Sweet Pickles books, the boy who kissed every girl during nap time, and the two boys I kissed under the back porch.

The nap-time lover, an oak-brown boy made of angles, would wait until he was sure the teacher was gone, then make his rounds. He was a lousy kisser. He’d mash his mouth against ours, lips closed, twisting his head back and forth like the actors in the old black-and-white movies we’d watch with our grandparents. I’m not sure why he started kissing us, but we girls were supposed to keep our eyes closed and remain passive, even as giggles lifted our shoulders from thin foam mattresses. One day, he came around and I kept my eyes open. I wanted to know if he closed his.

He did not. We stared at each other until our faces softened into brown clouds; then he licked my mouth. Why did adults like doing this? It was too wet and smelled of peanut butter. To get revenge, I stuck my tongue into his mouth. Then we battled, our tongues bubbling saliva out of the corners of our sticky lips. I’m not sure what the prize was, but he finally pulled away and laughed before moving to the next girl. Based on the rounds of “Yuck!” and “Ew!” that followed, he tried to slip other girls his tongue with varying success.

Over the next few days, he started bringing a handkerchief to wipe his mouth between girls. There were fewer exclamations of disgust. I’m not sure if he stopped the wet kisses or if everyone became used to them. With me, his kisses began to taste like peppermint candy but remained sticky. We kept our eyes open. I put my hand on the back of his head once, like the women in those same old black-and-white films. He grunted softly, the sound you make when you’re surprised nasty-looking food tastes good. His response scared me, but I liked it. At five years old, I already knew that if you liked what boys did too much, no one would like you. Girls called you names. Boys rubbed themselves against you while you waited for your turn on the monkey bars.

I never touched him with anything other than my mouth again.

I don’t remember how he was caught, but the nap-time kisses stopped. I think I missed them. Taking the required nap became difficult, because I was tense, listening for the rustle that meant someone was moving from his blue-and-red mat.

I soon found myself under the back porch at home with one of the little “mixed” (now called biracial) boys in the neighborhood. He had an Afro of loose waves, like Mr. Kotter from the TV show, and blue eyes that changed colors, especially when his white mother called him home. He never wanted to go. One day, she yelled his name, and he pulled me under my porch and stared at me. His breath did not smell good. It smelled of hunger, a stale metallic scent, but when he leaned in to give me a kiss, I accepted it.

I put my hands on either side of his face, and he did the same. We pecked at each other with our mouths, thumbs invading each other’s eyes, as we tried to imitate adults. And then his neighbor showed up—another boy our age. He was brown like me, with hair that blended into his skin but filled with close waves his mother made sure he brushed down all the time. His eyes were the same color as his skin but with black-black lashes. Those eyes were wide as he breathed out that he was going to tell we were being nasty. I reached out and kissed him, too. I don’t remember how he tasted, but I know he stopped talking.

I’ve lost track of how long we were under the back porch. The boys took turns kissing me. I took turns kissing them. My mother called me from the kitchen, and I hurried from our little cove. The boys’ mothers would just yell and yell until they came home, but my mother would come look for me. I shot into the house. My heartbeat fluttered my shirt. I could smell those boys on me—the foreign stink of their spit and sweat a secret reminder of my adventure.

Boys were quiet when you kissed them. They didn’t tease you for being skinny or bucktoothed or smart. Boys followed your lead when you kissed them. Boys let you rescue them from home when you kissed them. But kissing boys meant you were fast. Being fast meant you had babies nobody wanted and women talked mean about you. When you were fast, old men smiled at you with half of their mouths and invited you inside when no one else was home. Fast girls ruined lives. I didn’t want to be fast. I wanted kisses that were secrets I controlled.

*

Teenage motherhood is nothing new to my family, but it’s something my mother wanted to stop with her, as far as her two daughters were concerned. My sister, Izzie, is what Mama calls a pullout baby. She was born almost two years before Mama’s high school graduation. When my sister was a teenager, I saw a note Mama had written her: “Always use a rubber.” I giggled at rubber, such an old-fashioned term by then. Seven years separate me and my sister, and I’d been hearing Mama’s voice deepen with warning for a long time: “Don’t bring no babies home unless you can take care of them.”

My sister developed early. Until high school, she was always the tallest girl in her class. Her curves constantly fought against the age-appropriate clothes Mama bought for her. Mama knew how grown men could be, so she tried her best to keep Izzie a child as long as possible. Luckily, my sister went along with that plan. She’s the sweet and obedient one. Perhaps that’s a part of being the firstborn in the family. We have a younger brother, J, so that makes me the middle child, the baby girl. I’m my father’s firstborn. I am a mess.

I was a scrawny child who always carried books around. For a long time, my family called me Bugs, as in Bugs Bunny, because of my overbite. Family friends said I was cute, but it didn’t seem like boys thought so. At least, the boys I wanted to like me never did. I’ve since learned this is how life is, but until junior high, I felt overlooked for the girls who already wore training bras, had professionally styled straight hair, and who boasted of boyfriends at other schools.

My sister came of age in the eighties. Izzie watched all those Brat Pack movies—Sixteen Candles, The Breakfast Club, and Pretty in Pink, plus stuff like Weird Science and One Crazy Summer … and I watched right alongside her. I sat next to her and watched MTV until the music videos started to repeat themselves.

So I listened to these songs and watched the videos; I watched the movies and saw my sister clutching her hand to her chest because a white girl who sews her own clothes got to kiss the rich, popular guy. I saw teenage love played out as Forever Love, as overcoming class divides and teaching the rich kid that poor people are cool, too. I saw that white girls got to bring home boys and yell at their parents and be wanted, even if by someone undesirable. No adult was monitoring them to make sure they weren’t tempting grown men. In the movies, no white girls were considered fast. Instead, they were pressured to have sex, not stay away from it.

Black girls were tucked way in the back of the extras or in the second row of the dance number, their hair looking burnt from too much straightening, their makeup chalky, and with no love interest more significant than a dance partner.

There were plenty of sassy Black teenagers on television, in characters like Dee Thomas on What’s Happening!! or Tootie on The Facts of Life. These girls always had a smart remark ready on their lips and got plenty of laughs, but just like in real life, every crush they had led to lectures or scolds: “He’s just using you.” “You don’t know any better.” “Don’t make any decisions you might regret.”

Images of white girls in love came easily, but everywhere I turned, Black girls were warned.

In the fifth and sixth grades, school friends started to become pregnant. My mother wouldn’t let me go to their baby showers. She said it would condone their situation, and she didn’t want me to think it was okay to have a baby before I got to ninth grade. These preteen moms looked like they were in high school, but they had boyfriends who should’ve been in college. The girls wore gold jewelry and had haircuts like women with real jobs—tapered in the back with curls crunchy from holding spray in the front. They had figures that betrayed their ages and minds and could barely solve word problems, and yet they were the ones labeled “fast.” And maybe they were. Maybe they’d felt compelled to race to catch up to their bodies and ended up at a finish line they didn’t expect.

I remember one girl asking me why the grass was always wet in the morning. I replied, “It’s dew,” and she said, “No, it’s clear.” She thought I was talking about feces, as in doo-doo. And this was a child being blamed for her own middle school pregnancy.

I was not unaffected by my classmates’ becoming pregnant young, even as I remained fascinated by sex and love. I was scared. Teenage pregnancy was a family curse, and every time I looked in the mirror, wondering when my boobs and booty would come in, I worried it would happen because of “an accident.” I was the only one of my friends who was shapeless and without a boyfriend, or even a boy I was talking to. The girls started making noises about introducing me to friends of their boyfriends, and it scared me. When sixth grade began to come to a close and my mom asked me about where I wanted to go for junior high, I told her I wanted to go to a magnet school. Mama assumed I wanted a more challenging curriculum, but in reality, I wanted to leave my friends behind. I was afraid that if I stayed with them, I’d end up pregnant, too, and as much I hated having my body policed by the elders in my community, I did not want to be fast either.

I wanted to be loved.

Nichole Perkins is a writer from Nashville, Tennessee. She examines the intersections of pop culture, race, sex, gender, and relationships. Nichole is a 2017 Audre Lorde Fellow at the inaugural Jack Jones Literary Arts Retreat and a 2017 BuzzFeed Emerging Writers Fellow. She is also a 2016 Callaloo Creative Writing Fellow for poetry. She hosts This Is Good For You, a podcast that highlights the pleasures of life. She formerly cohosted Thirst Aid Kit, a podcast about pop culture and desire, with Bim Adewunmi, a producer at This American Life, and was also a cohost of Slate’s podcast The Waves, which looked at news and culture through a feminist lens. Her first collection of poetry, Lilith, but Dark, was published by Publishing Genius in July 2018.

Excerpted from the book Sometimes I Trip on How Happy We Could Be, by Nichole Perkins. Copyright © 2021 by Nichole Perkins. Reprinted with permission of Grand Central Publishing. All rights reserved.

August 18, 2021

What Is Drag, Anyway?

Martin Padgett’s first book, A Night at the Sweet Gum Head , tells the story of Atlanta’s queer liberation movement through the alternating biographies of two gay men, runaway–turned–drag queen John Greenwell and activist Bill Smith. In the excerpt below, an underage Greenwell sneaks into a bar and discovers drag.

Another Believer, Eagle Portland interior, 2021, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Huntsville, Alabama

January 1971

John Greenwell could stay in Huntsville and be the town queer, or he could run away and be free, so he ran.

He threw a couple of days’ worth of clothes in a cheap gray briefcase he’d had since high school, counted eleven dollars in his wallet, each bill worn down like him, and flew out of the house that he had never called home.

He had been born in Kentucky, the son of a mother he loved and an abusive, alcoholic father he grew to hate. The family moved whenever the military shipped them to another place: Tennessee, Texas, California, Germany, Alabama. By the time he finished high school in Huntsville, John Greenwell had already lived many lives.

He had been a good student, a Boy Scout, a member of the French club, an actor in a school film about poverty. A graduate. A heterosexual. When he braved the cold and walked to the bus station on the edge of Huntsville and put his dollar on the counter and found a seat on a bus headed east, he put that John Greenwell to death.

He dreamed of becoming a hippie, of growing out his short brown hair, of life with people like him. He wanted to see the world through psychedelic eyes. He wanted to touch the bodies of gods.

The bus rumbled to life. Its air brake hissed as it pulled away. Huntsville dimmed behind it as John’s eyelids flickered. He fell asleep to the urban lullaby he’d learned in eighth grade, Petula Clark’s escape fantasy, “Downtown.”

The bus crossed an imaginary line in the dark and Alabama faded into Georgia. John woke for a moment, decided he would never go back, then drifted off into the comfort of his dreams.

*

Wet bus doors slapped open and woke John up in Atlanta as midnight grew near. He walked from the smartly styled art deco bus station toward a hotel down the street, paid four dollars for the night, tossed his briefcase onto the dirty mattress of his small, cold room, and charged downstairs, not knowing what he would find.

John had only cruised a few city blocks toward the Strip when a one-armed man called out from his car. He didn’t say much. He didn’t need to. John ran back to his small, cold room, grabbed the cheap gray briefcase too small to hold any fear, raced back down the stairs, and jumped in for the ride. The newly minted couple drove south, to a house in a bad neighborhood where the stranger slept with a gun under his pillow.

*

The stranger waved goodbye to John in front of Rich’s department store the next morning. The ornate temple to commerce towered over an entire city block, so imposing Atlantans used it to locate themselves physically as well as socially. Margaret Mitchell had bought her dress for the Gone with the Wind premiere in 1939 there. Martin Luther King Jr. had integrated the store’s lunch counter. Coretta Scott King wore a conservative cloth coat from Rich’s when the reverend accepted his Nobel Peace Prize.

Rich’s had an auditorium, a china store, its own post office. Shoppers could wander past the Store for Fashion with its hat bar and wig salon, or the Parfumerie, where cloying spritzes of Chanel No. 5 clung to the air. They could smell the heady scent of yeasty breads and Lady Baltimore cakes and pecan pies that wafted from the bakery, watch children cheer as they rode the curly tailed Pink Pig monorail overhead through the toy department, or taste the tangy dressing of the Magnolia Room cafeteria’s chicken salad. Shoppers from around the South made special trips to Atlanta to buy from Rich’s. It was Oz compared to the Sears catalog store where John’s mother had bought the scruffy overalls that had followed him there.

John pushed his way through ornate brass-and-glass doors, found a friendly face at a counter, and asked if Robert worked there. A counter clerk pointed him to the shoe department, where Robert looked up in mild shock. He never expected his young acquaintance to make the trip to the city.

They had met only briefly, in a clandestine place months before, but Robert had made a promise, and he kept his word. He brought his stray home to his lover and they made John a bed on the couch.

John exhaled, then slept deeply. He had been in Atlanta just one day. He had a place to sleep, and a few dollars in his wallet. It was nearly all he had, now that life had started all over again, after it had barely begun.

*

Atlanta

Summer 1971

John rang up customers and stocked shelves at the SupeRx drugstore while he waited for night to come.

He had pined for the great unknown of big-city life, just like the heroes and heroines he read about in books and saw on television. The Wizard of Oz went Technicolor when Dorothy hallucinated her way out of Kansas; John’s life flipped into brilliant relief when he left black-and-white Alabama for urban Atlanta. The allure was absent in the SupeRx’s fluorescent lighting or its dingy carpet or its mind-numbing work, stocking shelves and counting receipts and checking out customers. It all came to life at night.

The drugstore lacked a certain glamour, but it was better than his first unsteady months in Atlanta when he had waited tables, took on odd jobs, and slept with men who let him stay overnight. SupeRx paid $1.60 an hour, enough to get him a room in a house nearby. It gave him something to do until he could head out after dark, to places like the Cove, where freedom coursed along invisible conduits.

Since he was six months under the age of twenty-one, John still was too young to get into any bar, gay or straight. His salary gave him the ten dollars he needed for a fake ID. When the Cove’s bouncers took his fake ID and pulled him out by his ear, John had to join the clique of underage revelers who waited in the lobby of bars, in the hope of finding a source for a new license, or at least a lift back home.

He had better luck at Chuck’s Rathskeller. A friendly bouncer drove him home one night, then gave him a place to sleep. One night turned into three. Soon the bouncer became his roommate and friend, one who would look the other way when John slipped in the bar through a back door.

Chuck’s had taken over an old juke joint and dance hall on the corner of Tenth and Monroe, near a high school on the corner of Piedmont Park. During the day the park teemed with the gay life John had dreamed about, shirtless men walking together hand in hand, women spread out sunning on picnic blankets. At night, the crowd reemerged at Chuck’s, where a DJ spun dance records for hundreds of club-goers. Atlanta drew gays and lesbians from all over the South, and on any given weekend the club put them all on display like the packaged goods once sold inside its walls.

Chuck’s held drag shows late at night, taking over the mantle from shuttered clubs like the old Joy Lounge and the infamous Club Centaur. John had heard about drag before he came to Atlanta but had never seen it. He watched, rapt in curiosity at drag shows, whenever he could. He saw an acquaintance, Alan Orton, perform as Barbra Streisand, his profile a mirror image of the Broadway queen. He witnessed a man named Alan Allison blossom into womanhood as Allison. He thought he saw Pearl Bailey perform “Hello, Dolly!” but realized it must have been a convincing illusion.

He clapped along as the crowd gave the drag queens applause and money. They were quasi-celebrities, queens of a demimonde that existed only at night, hidden under the mantle of dark.

John had long held fantasies of fame. But drag? It just wasn’t what men did in Alabama. He found it odd and disturbing, but it drew him in nonetheless.

*

What is drag, anyway?

Drag intersects with impersonation but goes beyond it. Impersonation is nonthreatening mimicry: Jonathan Winters as Maude Frickert, Flip Wilson as Geraldine. They’re men in dresses, no more. Their brilliant comedy derives not from the assumption of gender but from the assumption that the only punch line is in the contrast between their feminine look and their masculine selves.

But a gay man in a dress, or a lesbian in short hair and men’s clothes, is an altogether different being. Their images course with the electric knowledge that the performers have voluntarily given up citizenship in their presumed gender. Drag decimates presumptions of sexual identity—male, female, and all the points on the spectrum between those labels.

Drag gives many people the tools to decipher the complex meaning of their sexuality, a way to choose the place where they can exist peacefully inside themselves. Some see drag as an ultimate expression of self. Some see it as a threat.

When it matters most, drag asks universal questions. If you could wipe the slate and create a new identity, what would it be? What would you keep, and what would you set aside? Would you still be yourself?

Drag teaches an important lesson: Sometimes, to find out who we really are, we have to become someone else.

*

When the Cadillac pulled up to his antique-strewn apartment, John knew a star had arrived. John’s roommates had offered to put up some visiting performers from Louisville, including the leggy woman who strode up the driveway. She wore huge Jackie Onassis glasses, red hot pants, and a white tank top that exaggerated her height, her dark skin, her strong resemblance to Leslie Uggams.

“Hello, I’m Crystal Blue,” she said softly, in a high-pitched drawl, and extended a hand to John. She mesmerized him. Her voice perfumed the air with ambiguous allure.

She took his hand and inspected his clean-shaven face, smooth skin, high cheekbones, and lean, hundred-and-fifty-pound figure. He would make a beautiful woman.

“You do drag, don’t you?” Crystal asked him.

He wanted to meet men. He hadn’t moved to Atlanta to do drag.

“You will, honey. You will.”

Over the next few days, John grew to admire Crystal. Drawing from a suitcase, she had the magic to transform herself into a new person, one without a past. John realized he could do the same, become someone else, perhaps a beautiful woman with raven hair and long eyelashes. He tended to give in to his impulses, so when Crystal offered to teach him her art, he said yes.

Crystal groomed John. With the entourage she’d brought along, she helped him pull on and pin her wig, a black helmet updo sprayed heavily with Aqua Net. It fit. John didn’t have a clue how to glue on the big, thick eyelashes Crystal wore. She helped. He knew nothing about makeup. Crystal knew how to soften his male features. With her hired hands she reinvented him in a matter of minutes, and when she was done, the mirror reflected someone he did not recognize.

Wearing one of Crystal’s costumes, he toted her makeup and gowns and slipped into Chuck’s Rathskeller with her. He sat backstage while Crystal prepared, then watched as she transfixed the crowd with a song from the Broadway musical Purlie, the story of preacher Purlie Victorious Judson, who battles Jim Crow laws in his Georgia hometown and finds allies within a family held nearly in slavery, eventually freeing them from bondage.

Melba Moore’s “I Got Love” wafted from a turntable in the dim cavern of a club as Crystal wrapped her arms around herself. She walked with a confident strut and worked the crowd. “I know I’m a lucky girl, for the first time in my life I’m someone in this world!” In turn, the crowd pulled out dollar bills, first a few, then many. By the time Crystal took her third callback, the money had grown into a pile. She lifted it, and let it rain down on her.

John watched in awe at Crystal’s command of the crowd. For the first time, he thought he might want to do the same.

Martin Padgett has an M.F.A. from the University of Georgia’s Grady College of Journalism and received a 2019 Lambda Literary Fellowship. He has written for Oxford American, Gravy, Details, and Business Week. He lives in Atlanta, Georgia.

Excerpt adapted from A Night at the Sweet Gum Head: Drag, Drugs, Disco, and Atlanta’s Gay Revolution , by Martin Padgett. Copyright © 2021 by Martin Padgett. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

Poetry Is Doing Great: An Interview with Kaveh Akbar

Photo: Paige Lewis. Courtesy of Graywolf Press.

Enthusiasm is at the heart of Kaveh Akbar’s literary endeavor. Since the publication of his 2017 debut collection, Calling a Wolf a Wolf, a hyperspeed, ultrasensory journey through addiction, recovery, and spirituality, he’s become one of the best-known poets in America, and that’s saying something in this moment when poetry is suddenly, somehow, cool. But before that, Akbar was already a tremendous presence—a prototypical online influencer, sharing pictures of pages from other poets’ books with his many followers, spreading the gospel far and wide. Calling a Wolf a Wolf was a phenomenon, reaching thousands of readers, many of whom discovered and fell in love with poetry through their feeds. Though Akbar has since left social media, he remains an advocate through his work as poetry editor of The Nation. When I spoke to him over Zoom, he was at an artists’ residency at Civitella, in Italy, and despite the distance and shaky internet connection, we gabbed about the life-or-death practice of poetry like the pair of gleeful nerds we are.

Akbar’s second collection, Pilgrim Bell , feels less frantic than his first, though no less intense. There’s lots of white space on the page, and the poems are often cut into short, staccato sections, sentence fragments that accrue emotional power but avoid straightforward narrative or confession. The poems deal with family, religion, love, the wreckage of Trump’s America, and daily life in the highly pressurized environment of the past few years. They feel profoundly intimate to me, as if they seek to reclaim the nuanced language of inner life from all the public noise that threatens it. Reading Akbar’s work and talking with him was a welcome reminder that this art form is soul-sustaining and worth building a life around.

INTERVIEWER

Let’s start with the idea of poetry as a practice. Is it something you feel you need to do regularly?

AKBAR

Yeah, I mean it’s never off. Everything that enters my consciousness enters first through the prism of its poetic utility. Were you ever a kid who would hold your shirt out like—I don’t know if you can see it—like this, and you would fill it with stones or shells or whatever? I feel like I’m just moving through the world with my shirt out in front of me, filling it with language and images. And over the years I’ve realized that one hundred thousand percent of the time, if I’m like, “I’ll remember this, I don’t need to write it down,” I forget it instantaneously. So I just write everything down.

INTERVIEWER

What do you use to write it all down on? Your phone? A notebook?

AKBAR

I have all of these legal pads everywhere—there are four of them on this desk that I’m sitting at right now. There’s no organization to it, I just use whichever one is closest to me. I also have thousands of pages of digital notes on my computer.

INTERVIEWER

I know you’ve spoken about this before, but could you talk about how that practice helped you overcome addiction?

AKBAR

There were a lot of things that helped me move out of addiction. It wasn’t like I picked up a book of Komunyakaa’s poetry and suddenly I wasn’t addicted. Early in recovery, it was as if I’d wake up and ask, How do I not accidentally kill myself for the next hour? And poetry, more often than not, was the answer to that. I would pick up Neon Vernacular and then I would have a place to be for, like, four hours. If I was writing a poem, that’s two, four, eight hours that just flew by. That was a place to put myself for a big chunk of that time.

INTERVIEWER

So do you think of Calling a Wolf a Wolf as a kind of survival mechanism?

AKBAR

I love my first book very much, I’m very proud of it and I have a lot of affection for it—but it is this sort of clumsy, loud, noisy, urgent, uneven thing, and so much of that has to do with the sense I had that I was floating out in the ocean, clinging to this two-by-four.

INTERVIEWER

Just flipping through Pilgrim Bell, the first thing I notice is that the poems are thinner, for the most part, and a lot of them are made up of little sections that feel like bursts of consciousness. How did that formal decision evolve?

AKBAR

I wrote my first book living basically a hermetical poet’s life. I taught two classes a week, but aside from that I had no real responsibilities to be anywhere, to be anyone, or to do anything. So there was a lot of quiet in my life that was filled with writing. I had a lot to say, and the unpunctuated line—which I stole from Lucille Clifton, and Ellen Bryant Voigt’s Headwaters, and middle and late W. S. Merwin—allowed me to get at a sort of supersaturation and momentum and centripetal force that could evoke the urgency of the things that I was talking about.

Then, in between the two books, my life got noisier. I got married. I began to teach at different institutions. As my life got noisier, I became more and more interested in building silence into the poems. I began looking to people like Jean Valentine, who uses silence as almost an architectonic element on which the poems are built, so that language is sort of the negative space around it.

I was also reading If Not, Winter, Anne Carson’s versions of Sappho. I was amazed by how open those synapses in Sappho are, how time sort of marbled these silences across Sappho. That not just allows but demands that your imagination complete the circuit of cognition. It became really interesting to me to disrupt the syntax in some way that activates the reader. Especially when—not to put too fine a point on it—engaging these sorts of psychospiritual dramas that are also invested in a lot of civic and social matters.

INTERVIEWER

I don’t know how much of the book was written during the Trump presidency, but I bet a good deal of it.

AKBAR

Yeah, a lot of it.

INTERVIEWER

So there was that overabundance of noise, as well.

AKBAR

Yes. And between writing the two books I had gotten off of all social media. I don’t mean to speak prescriptively but, for me, it was really insidious how that shit colonized my mind and colonized the algorithms of my thinking and hijacked my rage. On social media, the same rhetorical language was being used about the casting of some Marvel movie as about the leveling of a village in Syria. The same exact rhetorical algorithms of outrage were used to talk about one as the other. Our brains haven’t evolved enough to differentiate between the two. Language is language. And so I was just not in command of my compassion, the distribution and focus of my rage, and it took a while to recalibrate. I think I still am recalibrating.

INTERVIEWER

I think, fundamentally, the thing that we practice when we live and work as poets is how to reliably wind up in a quiet internal place that is the opposite of social media. Sometimes it takes ten or twenty years to be able to do that, and that’s what becoming a poet is.

AKBAR

I feel like everyone from Catullus to Carson has said some version of, You have to figure out how to train your instincts and then get out of the way. And it’s the most obvious thing when you can sense it, but it’s the hardest thing to articulate. And what works for me isn’t what would work for you.

INTERVIEWER

Finally, you have to withdraw to a private place, to a private way of doing it. I mean, you can tell me how you do it in an interview, but—

AKBAR

Right. And it’s hard because, again, a big part of my life is teaching across a number of different institutions, and though I have a degree in English education, by and large the prerequisite for teaching poetry is just having written a lot of poetry, which doesn’t actually really help me tell anyone else how to write poetry.

INTERVIEWER

Well, the actual prerequisite for teaching is a lot like the prerequisite for writing poetry—you have to be able to enter a state in which you are lucid and can pass a conversation around a room. Teaching, like poetry, is a spiritual practice.

AKBAR

That’s a beautiful way to frame it. I say things like that and then I get self-conscious that people are like, “Oh, he said the S-word.”

INTERVIEWER

With poetry you have to have a way of corralling the people in your head, getting them to where you need them to be so that you can address them. I think that has to be spiritual, on some level. And religion is an aspect of your poetry. It’s in there.

AKBAR

But I think even the most secular writers, even the most skeptical, feet-on-the-ground writers still talk about time flying by, or how such and such a phrase just came to them. They’re still sort of mining the language of the supernatural to talk about what is not them in their writing.

INTERVIEWER

Right. Whatever you call it, it’s that. Another thing that happened between your two books is that you got a little famous, right? I’m curious to know what kind of pressure that exerts on the writing. How do you manage that sense that people are watching? When you were on social media, one of the ways you seemed to manage it was by being a kind of community organizer, sharing other people’s poems a great deal. You’d say, “Hey, this is great,” and that would whip up excitement around a poem, and that seemed to be a generous or healthy way to handle what might otherwise have become a crushing self-consciousness.

AKBAR

Well, you know, the crushing self-consciousness doesn’t go anywhere. [Laughs.] There’s a reason that I found my way into poetry. I think we all have the aesthetic mediums to which we are most permeable, and there’s a reason that mine was poetry, because it creates a one-to-one relationship between you and the person that you’re reading or the person that you’re writing to. “Personism,” the Frank O’Hara essay, is really important to me, and thinking of the poem as a way of almost picking up the telephone and speaking to a specific other, whether that other is the page or God or justice or whatever.

That self-consciousness was really corrosive to everything. To my ability to be creative. To my ability to think and doubt and sit in uncertainty without trying to resolve it. And I think that those are critical states for me to be able to nourish and protect. There came to be too many ports of entry into my consciousness. And, to be really real, I just wasn’t doing very well with it. I would obsess over meanness. Of course, anyone on the internet will experience some amount of meanness. I got, and still get, a fair number of people writing me and calling me racist names and so on. That doesn’t bother me as much anymore, because I can say to myself, Oh, this person is unwell. The stuff that did get under my skin was the straw man thing of situating me as the avatar for a system that I, too, was trying my best to move against. I reached a point where I couldn’t enjoy a moment of my life—the joy of my students, quiet moments with my spouse—without feeling like I was doing something wrong, like I was defective in my living, my ethics. And over time, eventually, I was able to apprehend that there were a lot of quiet channels of my goodness. I do a lot of work with people in recovery that I don’t talk about publicly. And that stuff is actually probably most of my life.

INTERVIEWER

That’s really wise and helpful to hear.

AKBAR

I don’t want this to come out and sound like I think everyone should quit. Some people use social media in a perfectly healthy and good way. Just like I can’t drink today, and plenty of people can drink safely. I couldn’t use social media safely.

INTERVIEWER

If you have the kind of personality that gets obsessed with things, which many poets do, then poetry can help absorb that obsessiveness—but there have certainly been times when I had to pull myself back from poetry just to deal with my family. So, it’s always about finding something you can be addicted to that won’t eat the rest of your life.

AKBAR

Exactly that. I can’t improve upon what you just said. I’m not even going to try.

INTERVIEWER

Could you talk a bit about your investment in the poetry community?

AKBAR

I feel like a lot of people operate as if poetry is teetering on the brink of extinction, and it’s all of our jobs to sort of huddle around the final flame of poetry and defend it. I think it’s doing great. Citizen was a New York Times best seller, and even books that are not that high-profile get a lot of attention—there’s a lot to be really excited and enthused about. I want to be of service to poetry because I think a life spent in humble, joyful service to that which you love best is a life really well lived. But that has taken a quieter, more behind-the-curtain form in my life now than it used to.

INTERVIEWER

Is being poetry editor for The Nation one of those behind-the-curtain forms of service?

AKBAR

Totally. And my assistant editor, Kate O’Donoghue, does beautiful work with me. We’ve really tried to develop a global curatorial aesthetic, so we’re publishing a ton of work in translation, from authors and translators all around the world. I have such reverence for the gift of getting to read through the queue of poems, to have my ear to the soil of the poetry conversation. That’s been one of the great gifts of the past couple years of my life.

Craig Morgan Teicher is the digital director of The Paris Review and the author of several books, including We Begin In Gladness: How Poets Progress and Welcome to Sonnetville, New Jersey.

August 17, 2021

Redux: Some Instants Are Electric

Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

Margaret Jull Costa. Photo: © Gary Doak / Alamy Stock Photo.

This week at The Paris Review, we’re highlighting women writers and translators from around the world in honor of Women in Translation Month. Read on for Margaret Jull Costa’s Art of Translation interview, Hiromi Kawakami’s short story “Mogera Wogura,” Claribel Alegria’s poem “Summing Up,” and Svetlana Alexievich’s work of nonfiction “Voices from Chernobyl.”

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, poems, and works of criticism, why not subscribe to both The Paris Review and The New York Review of Books and read both magazines’ entire archives?

Margaret Jull Costa, The Art of Translation No. 7

Issue no. 233 (Summer 2020)

Translating is writing, and I see no distinction, really, between being a writer and being a translator, apart from the very major distinction that I don’t start with a blank page but immerse myself in another writer’s words and transpose them into my own language. People often ask if I don’t yearn to write my own novels, and I don’t. I don’t have that kind of storytelling imagination. Just as actors don’t all yearn to write plays or musicians to compose symphonies, I enjoy the process of interpretation and performance, of conveying someone else’s words and ideas to a new audience. Not that I’m a neutral voice, that’s not possible, but, if all goes well, I’m the writer’s voice with a different cadence.

Mogera wogura by Coenraad Jacob Temminck, 1842, via Wikimedia Commons.

Mogera Wogura

By Hiromi Kawakami, translated by Michael Emmerich

Issue no. 173 (Spring 2005)

Every morning, I go around and give each human a few soft pats on the shoulder. First, this allows me to make sure they’re still alive. Second, it gives me a chance to find out if they want to leave immediately, or if they’d prefer to stay a little longer.