The Paris Review's Blog, page 101

September 22, 2021

Bezos as Novelist

The first thing that needs to be noted about the collected works of MacKenzie Bezos, novelist, currently consisting of two titles, is how impressive they are. Will either survive the great winnowing that gives us our standard literary histories? Surely not. Precious few novels do. Neither even managed, in its initial moment of publication, to achieve the more transitory status of buzzy must-read. But this was not for want of an obvious success in achieving the aims of works of their kind—that kind being literary fiction, so called to distinguish it from more generic varieties. In Bezos’s hands it is a fiction of close observation, deliberate pacing, credible plotting, believable characters and meticulous craft. The Testing of Luther Albright (2005) and Traps (2013) are perfectly good novels if one has a taste for it.

The second thing that needs to be noted about them is that, after her divorce from Jeff Bezos, founder and controlling shareholder of Amazon, their author is the richest woman in the world, or close enough, worth in excess (as I write these words) of $60 billion, mostly from her holdings of Amazon stock. She is no doubt the wealthiest published novelist of all time by a factor of … whatever, a high number. Compared to her, J. K. Rowling is still poor.

It’s the garishness of the latter fact that makes the high quality of her fiction so hard to credit, so hard to know what to do with except ignore it in favor of the spectacle of titanic financial power and the gossipy blather it carries in train. How can the gifts she has given the world as an artist begin to compare with those she has been issuing as hard cash? Of late it has been reported that Bezos, now going by the name MacKenzie Scott, has been dispensing astonishingly large sums of money very fast, giving it to worthy causes, although not as fast as she has been making it as a holder of stock in her ex’s company. Driven by the increasing centrality of online shopping to contemporary life, its price has been climbing. There are many fine writers of literary fiction, maybe too many—too many to pay close attention to, anyway—but only one world’s richest lady.

But the weird disjunction between the subtleties of literary fiction and the garishness of contemporary capitalism and popular culture might be the point. The rise of Amazon is the most significant novelty in recent literary history, representing an attempt to reforge contemporary literary life as an adjunct to online retail. On the one hand, Amazon is nothing if not a “literary” company, a vast engine for the production and circulation of stories. It started as a bookstore and has remained committed ever since to facilitating our access to fiction in various ways. On the other hand, the epic inflection it gives to storytelling could hardly be more distinct from the subtle dignities and delights of literary fiction of the sort written by MacKenzie Bezos.

It was she who, according to legend, took the wheel as the couple drove across the country from New York to Seattle to start something new, leaving her husband free to tap away at spreadsheets on his laptop screen in the passenger seat. If this presents an image of Jeff as the author of Amazon in an almost literal sense, it surely mattered—mattered a lot—that his idea for an online bookstore was fleshed out while living with an actual author of books or aspiring one. “Writing is really all I’ve ever wanted to do,” she said upon the occasion of the publication of her first novel in 2005. By this time Amazon was already the great new force in book publishing, although it had yet to introduce the Kindle e-reader, the device that made a market for e-books. Neither had it hit upon perhaps its most dramatic intervention into literary history, Kindle Direct Publishing, the free-to-use platform by whose means untold numbers of aspiring authors have found their way into circulation, some of them finding real success. It had not yet purchased the book-centric social media site Goodreads, or Audible.com, or founded any of the sixteen more or less traditional publishing imprints it now runs out of Seattle.

That self-published writers have succeeded mostly by producing the aforementioned forthrightly generic varieties of fiction, and not literary fiction, is part of this story. Romance, mystery, fantasy, horror, science fiction—these are the genres at the heart of Amazon’s advance upon contemporary literary life. They come at readers promising not fresh observations of the intricacies of real human relationships—although they sometimes do that, by the way—but compellingly improbable if in most ways highly familiar plots.

In one recent self-published success, a man awakens to find he has been downloaded into a video game. Rallying himself surprisingly quickly, he lives his version of The Lord of the Rings, but now with a tabulation of various game statistics appearing in his mind’s eye. In another, a young woman is gifted with the power of prophecy, making her a target of the darkly authoritarian Guild. Run, girl, run! In still another, a woman has a job as a “secret shopper,” testing the level of customer service at various retail stores, stumbling into a love affair with the impossibly handsome billionaire who owns them all. Then there are the zombies. There are as many moderately successful self-published zombie novels as there are zombies in any given zombie novel—hundreds of them. Whether dropping from the air into the Kindle or other device, or showing up on the doorstep in a flat brown box, these are the works that Amazon’s customers demand in largest numbers and which it is happy to supply.

The Testing of Luther Albright is nothing like them, though no doubt it, too, has been delivered to doorsteps by Amazon on occasion. What I find fascinating is how the traces of genre fiction are visible in the novel all the same, if only under the mark of negation. Told in the first person, it recounts the strained but loving relationship of a repressed WASP father to his wife and son. He is a successful civil engineer in Sacramento, a designer of dams, and has built the family home with his own hands. Leaning perhaps too heavily into the analogy between the structural soundness of buildings and of family relationships, the novel has an ominously procedural, even forensic quality, reflecting the quality of mind of the man who narrates it. Luther is not a negligent father or husband, just a painfully self-conscious and overly careful one, so much so that he might be creating the cracks in the foundation of his life it was his whole purpose to avoid.

But no dam breaks and nothing ever crashes to the ground.

Indeed, it can seem that the novel is structured by a systematic refusal of potential melodrama, the kind of thing that would naturally have been at the center of a thriller. He buys his son a nice new car and watches nervously as he drives it a bit carelessly, but no horrific accident ever occurs. His strikingly pretty wife gets a job at a crisis helpline and begins to stay out late. She is acting a bit strange. Is she having an affair? Actually, no, she is just working hard talking people off the ledge. There has been an earthquake near Sacramento. Will the dam he designed break, drowning thousands? No, it holds, despite the best efforts of a local reporter to scare people into thinking it won’t. Best of all: Luther has hidden the gun he inherited from his alcoholic father in a secret compartment in the basement. He worries about it being there. It throbs in his mind like a telltale heart. Chekhov’s law tells us it is required eventually to go off, but it never does.

This is not just literary fiction, but militantly literary fiction, however politely so. It insists on the dramatic tension built into ordinary middle-class life. It is a declaration of autonomy from the ginned-up fakery of genre fiction even as it watches the latter out of the corner of its eye. The same is true of Traps. Told in the present tense, alternating the stories of four quite different women in Southern California and Nevada over the course of a few days, it contrives their convergence at a crucial juncture in each of their lives. It has something of the structure of the modern thriller à la Dan Brown but without the global conspiracies and evil monks and rigorously indifferent prose. Instead it features a subtle background motif of our relation to dogs, those creatures we care for but who can also occasionally be dangerous. It attends to details—“a bulletin board behind her fringed with notes and flyers and a few canceled checks, and on the counter next to the register sit a bowl of peppermint candies, a March of Dimes donation can, and a rack of People magazines, the one with mothers and children on the cover”—with no significance other than as an intensification of what Roland Barthes called the reality effect of realist fiction.

Unless it be those copies of People magazine: one of the four protagonists of Traps, the easiest to connect to the situation of her author, is a skittish movie star and mother who sees her family life become fodder for paparazzi. Another, we learn, is part of the private security team that protects her as one surely protects MacKenzie herself in real life. Against the luridness of Hollywood gossip, the novel is on the side of the sanctity of private histories and intimacies. It finds interest and even some excitement in the difficult work of maternal care, which can turn the traps of life and love into opportunities for growth and renewal. Like Luther Albright, it is a testament to the decisive importance of family. “Family life” being some of the favored territory of literary fiction, much less prevalent as a theme in romance, mystery, fantasy, or science fiction. Appropriately, the novel is dedicated to the author’s parents, and its acknowledgments speak touchingly of the personal importance of her four children and then husband, Jeff.

A man who, meanwhile, is known to have a taste for popular fiction, especially for works of epic science fiction, although he has a documented interest in literary fiction, too. Perhaps he was encouraged in that direction by MacKenzie, who studied creative writing with Toni Morrison at Princeton. He attended the same university but studied computer science. As the author (he would prefer the term “inventor”) of Amazon, he has created something akin to a work of epic science fiction sprung to life. The sprawling logistical networks, state-of-the-art warehouses, superpowered information technologies and interfaces—all of it, to which we might add his personal investment in space travel through his privately held company Blue Origin, an investment said to be running at the rate of about a billion dollars a year. For Stern School of Business professor Scott Galloway, Amazon’s “core competence” is really “storytelling,” not the other stuff. In The Four: The Hidden DNA of Amazon, Apple, Facebook, and Google, he explains: “Through storytelling, outlining a huge vision, Amazon has reshaped the relation between company and shareholder.” Has it done the same for the relation between writer and reader?

In the early years of Amazon, Jeff Bezos was very much a showman—a goofily ingratiating alternative to Steve Jobs with a notoriously honking laugh. Amazon was something that had to be sold hard to shareholders and customers alike. These days, with nothing left to prove to anyone, his public persona has cooled, his gaze sharpened, the laugh traded in for a quietly bemused smile. As could have been predicted by one of his ex’s novels, with their suspicion of predatory media, he briefly found himself at the center of a “dick pic” blackmail scandal involving his new TV-anchor-cum-helicopter-pilot girlfriend, but handled it with admirably preemptive efficiency before it could really get off the ground. Even so, the distance Jeff has traveled from domestic life with a camera-shy, preppy novelist wife could hardly have been made clearer. From now on, the founder of what once billed itself as Earth’s Biggest Bookstore would himself be living large, larger than life.

In truth, it’s not quite fair to associate all of this with popular genre fiction, only one sort of which runs toward the epic—the big, the bold, the world-forming. Neither is literary fiction always obsessed with the intimate and small, having its own avatars of epic in writers like Thomas Pynchon, David Foster Wallace, Karen Tei Yamashita, and the like. If works like MacKenzie Bezos’s are sometimes held in contempt for their avoidance of politics in favor of domesticity, the epic versions of literary fiction are harder to criticize on those grounds. The dynamic opposition of “more” to “less” and vice versa has been fundamental to the aesthetic development of contemporary fiction in all its forms, high and low. One might speak, for instance, of how the romance novel, that most generic of genres, is all about the forging of the small world of a marriage as a space apart from the alienations of modern life. This is as opposed to the epic sprawl of Game of Thrones, where marriages are wholly public, wholly political, and deadly; or for that matter a science fiction epic like Neal Stephenson’s Anathem (2008), whose concerns are so cosmic as to leave that level of human relations behind altogether.

More and less. If the keynote of Amazon is certainly the first, the second is never far behind as a rejoinder to it in an aesthetic economy shadowing the real one. A real one where, in a sense, every meaningful decision is a matter of having or acquiring or selling or spending more or less of something, including, of course, money. Whether in the form of literary fiction or genre fiction—the first, in the Age of Amazon, being in essence a subset of the second, simply a genre in its own right—the novel will appear in these pages as what I would call an existential scaling device. It is a tool for adjusting our emotional states toward the desired end of happiness, whatever that might look like to a given reader, however complex or simple a state it might be. Fulfilling that task depends upon the rules of genre, upon the implied contract it draws up between author and reader for the reliable delivery of stories of a familiar kind. Genre being a version, within the literary field, of the phenomena of market segmentation and product differentiation. Before that, dating back to antiquity, it was a way of piecing through the different things that stories can do for us and instructing writers to construct them accordingly.

Gravitating as a matter of course toward literary fiction, to the genre that likes to think of itself as nongeneric, scholars of contemporary literature have generally been neglectful of this all-important organizing feature of literary life, and no wonder. When it comes down to it, works of literary fiction are more reliable providers of discussable interpretive problems than works of genre fiction, whose interest often snaps into focus only at the level of the genre as a whole. Coming alive in the classroom, works of literary fiction advertise their interpretability in many ways, not least by refusing to fully subordinate the unit of the sentence, with its potentially artful intricacies, to the purposes of plot. Neither do they forgo thematic subtleties, things you could miss on a quick read. That, paradoxically, is their generic appeal.

To be sure, individual works of genre fiction have been known to generate volumes of learned commentary. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818), Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897), and Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five (1969) are works of apparently inexhaustible literary interest, however historically belated their recognition as masterpieces by scholars and other arbiters of aesthetic rank. Furthermore, if it were ever really the case, the days are long past when one could safely assume that any given new work of genre fiction must be artistically unsophisticated. Genre categories have by now found themselves internally differentiated into more or less “literary” instances appealing to relatively distinct if no doubt overlapping audiences. Ironically, this is true even of the category of literary fiction, whose more routinely sentimental examples are no more likely to find themselves the objects of scholarly attention than their more luridly generic brethren. They might even find themselves categorized as something else altogether, as “women’s fiction” or “chick lit” or other offshoot of romance.

But artistic complexity of the kind congenial to the classroom is not necessarily what readers of genre fiction require. Just as important, frequently enough, is the work’s reliability as a competent new execution of a certain generic narrative program. That is where it falls in line with the ways and means of Amazon as a paragon of reliable service, and why genre fiction is the heart of the matter of literature in the Age of Amazon. Only as it were accidentally, because it is something a number of readers still prefer, does the company serve up the dignified delights of literary fiction.

Positioning literature lower on the hierarchy of human needs than we might like, putting books on the virtual shelf alongside other staples one might order from the Everything Store, Amazon is not so much anti- as omni-literary, making an epic narrative out of the speedy satisfaction of popular want. What literature loses in that transaction—too much, no doubt, for scholars to accept without a fight—it partly gets back as an endorsement of its everyday necessity. For whole cultures as well as for individuals, stories are of prime importance, and not just on special occasions. They are what guide our purposeful and pleasurable movement through time. Certainly, they have been necessary to Amazon, whose rise as a titan of contemporary commerce would have been unthinkable without the inspiration provided by works of fiction and the market opportunity presented by books.

Mark McGurl is the Albert Guérard Professor of Literature at Stanford University. His last book, The Program Era: Postwar Fiction and the Rise of Creative Writing, won the Truman Capote Award for Literary Criticism. He previously worked for the New York Times and the New York Review of Books.

Excerpt from Everything and Less: The Novel in the Age of Amazon by Mark McGurl, published by Verso Books. Copyright © 2021 by Mark McGurl.

A Woman and a Philosopher: An Interview with Amia Srinivasan

Photo: Tereza Červeňová/Morgenbladet

When Amia Srinivasan published her essay “Does Anyone Have the Right to Sex?” in the London Review of Books in early 2018, several months into the public discussions surrounding #MeToo, it provoked many strong feelings—not to mention gave the world the sentence: “Sex is not a sandwich.” Opening with a reading of the incel manifesto written by the perpetrator of the Isla Vista killings, it became a far-reaching meditation on the ideological, political, and public dimensions of sexual desire and how we might begin to think more critically about them.

Srinivasan trained as a philosopher at Yale and then Oxford, where she has since established herself at the heart of the old boys’ club that is analytic philosophy. In 2019, she was given the Chichele Chair in Social and Political Theory once occupied by Isaiah Berlin; she is the first woman, the first person of color, and the youngest person ever to take up her post. Most readers, however, will know her for her rich and entertaining pieces in magazines like The New Yorker and the London Review, including my favorite, a 2017 paean to octopuses—“the closest we can come, on earth, to knowing what it might be like to encounter intelligent aliens.”

Srinivasan’s new book, The Right to Sex , is a collection of bold yet subtle essays, equally distinguished by their capaciousness and economy, full of sharp turns and trapdoors. It offers a formidable account of the workings of race, class, and institutional power within our sexual politics. “The Conspiracy against Men” swiftly dismantles many common misconceptions about false rape accusations, Title IX, and cancel culture, some of which have grown invisible through repetition. There’s a piece on the fierce and profound engagement of Srinivasan’s students with once derided antiporn figures like Catharine MacKinnon and Andrea Dworkin, whose arguments have a new force for those who feel that online porn has meaningfully structured their own consciousness and sexualities, and another on the increasing coziness with state and corporate interests that has marked mainstream UK and U.S. feminism over the past few decades. “On Not Sleeping with Your Students” upends a cherished Ivy League defense of professor-student romances, making the case that people who initiate students into new ways of thinking might well (and arguably should) inspire feelings of excitement and attraction—yet their responsibility is precisely to direct those feelings to advance the student’s learning, not to gratify the professor’s vanity or lust. That essay, Srinivasan told me recently on Zoom, “is the one that I’ve had women most consistently write to me about.”

INTERVIEWER

When did you become a feminist?

SRINIVASAN

I had no relationship to feminism growing up. I remember distinctly a French teacher in school—I guess I was in sixth form—asking which of us identified as feminists. And we looked at her as if she was asking, Which of you identify as Levelers? Right? Some historical category that just seemed completely inappropriate and also deeply unsexy. And then, when I was an undergraduate, I’m horrified to say that among the mainstream humanities students, feminism wasn’t seen as something very intellectually serious.

So, feminism was an entirely extracurricular thing that I came to as a graduate student at Oxford. Literally what happened was that one summer, my best friend, who was then a grad student in philosophy at NYU, handed me a copy of The Second Sex, and I think she had a copy of The Feminine Mystique. And she just said, Look, I think it’s about time that we read these.

And then a little later on, I ran a reading group in feminist philosophy. What was great was that it brought out of the woodwork lots of students who you would have thought wouldn’t be interested in this stuff. We were all writing dissertations on epistemology and metaphysics and philosophy of language. People who seemed like very mainstream analytic philosophers turned out to be having these subterranean, dissenting inclinations and desires.

INTERVIEWER

So this was partly a rebellion against the institutional experience you were having?

SRINIVASAN

It was an expression, I think, of a certain kind of intellectual frustration I was experiencing from working in a very narrow analytic mode. On one hand, I found the emphasis on clarity and precision important, and I’m grateful for it. On the other, I found it stifling, and I was worried that the parts of my brain that I valued the most—the parts that engaged with literature and poetry and history—were being pruned away. So, it was a reaction to the analytic philosophy training I was getting. And also a reaction in another way, which is just that philosophy is a very male-dominated discipline, and that has all the results you would expect, plus some that are harder to articulate unless you’re in that kind of environment. Michèle Le Dœuff has this great line in Hipparchia’s Choice. I’m going to butcher it, but it goes something like, When you’re a woman and a philosopher, it’s useful to have feminism to be able to understand what is happening to you.

INTERVIEWER

Do you think of your nonacademic writing as connected to what you publish as a philosopher? And how do you see the relationship between philosophy and politics?

SRINIVASAN

We should have a much broader understanding of what counts as philosophy and what counts as political theory. A lot of the great feminist texts are profitably read as both, and that’s something I try to get across with my students. Reading The Dialectic of Sex is a lot like reading the Republic, for example. They’re both thrilling, weird, carnivalesque, problematic, very cool, imaginative texts that bear deep engagement.

I don’t spend much time thinking about whether what I do is philosophy or not. I just write about what I’m interested in. Unlike some people who are philosophers by profession and interested in social and political issues—especially the imperfect social and political realities with which we are faced—I have a vast amount of time for totally pointless things. I was supervised by two philosophers who work in very abstract epistemology, metaphysics, philosophy of language and logic, and I would absolutely hate the idea that they would have to show the political relevance of what they do. While the arts and the humanities more broadly have an important social and political function, their justification should never rely on that function. And so, I’m very worried about an impetus to make the humanities politically relevant. I don’t think their political importance lies in their relevance. When they are relevant, that’s a lovely thing, because it would be a tragedy to leave politics to the politicians or the social scientists.

I think the truth is, if I had a different set of skills, if I could choose, I would much rather be an artist than a philosopher. I mean, what better thing is there to be able to do than create something absolutely beautiful?

INTERVIEWER

Speaking of beauty, in the book you quote this wild, vertiginous passage from Beauvoir about what sex might be like if the sexes were equal.

SRINIVASAN

Right, exactly. That is also something I wanted to bring out from these classic feminist texts that people often misread or just misremember or misconceive as being resolutely dour and pessimistic and boringly political. You see this in someone like Shulamith Firestone, who ends by talking about being freer to love. You see it in Valerie Solanas talking about the emancipation of the imagination. The emancipation of the imagination, of course, is central to Andrea Dworkin, this person we think of as being so relentlessly negative about human and social life. But she’s got this vision. She just wants more! That’s the thing I would like people to know about a lot of feminist texts, is that they’re just not satisfied. It’s not negativity. It is a deep desire to bring about other kinds of imaginative possibilities, and a dissatisfaction with the constraints on imagination, on women’s imaginations in particular, that they viscerally feel.

INTERVIEWER

So, in thinking about our desires as political, as social—not individual, in some sense—is there a tension there when we consider what to do about them? What would be a collective way of addressing the politics of desire?

SRINIVASAN

When I first wrote what is now the title essay of the book, I was trying to point out a largely unremarked upon tension between the commitment to consent-centric sex positivity and intersectionality. If you’re going to really think about the relationship between, say, racial domination and patriarchy, then you’ve got to think about the racial formation of desire. This isn’t a particularly new thought. Angela Davis takes Shulamith Firestone to task for failing to do precisely this.

In the book, I stress that I’m not trying to suggest a project in which every individual sits around thinking about whether their desires conform to their political commitments, much less proposing some sort of Maoist sessions where we all sit around and tell each other whether that’s true or not. Mostly because I just think that’s bad politics. We can look at the history of the U.S. women’s liberation movement to see what happens when a group of people committed to radical social change start to embrace an obsessive concern with the putative mismatch between individual lives and political commitments. At the same time, we need some of that, right? Because that is what distinguishes the New Left from the old Left.

I want us to have an ambivalent relationship to questions of what it means to render the personal political. What I’m really proposing is something that queer people for a long time have been proposing, which is just to think more imaginatively and creatively about what your desires might actually be. And this brings us to psychoanalysis, because one thing that tradition teaches us is that we’re in the constant business of repressing all sorts of things about ourselves and our sexualities and our affinities. At least some of those forms of repression—maybe not all of them—stop us from living freer lives. So, I’d like to see this project as a liberatory one rather than a disciplinary one. I’m not telling the person who is fixedly straight—whatever that means, but let’s just suppose there are such people—that you have to be queer. But I am saying, Let’s all be a bit more attuned to those instances where we are not listening to desire, but listening to a political force that tells us what we shouldn’t desire. I take that to be in keeping with a broader queer tradition.

INTERVIEWER

You’ve had the experience before of being objectified by journalists—the “hot philosopher” who “gives good interviews,” et cetera. That’s obviously annoying. At the same time, we’re all embodied creatures. You and I both, for example, appear in the world as quite femme. It seems to me that our experiences of that must structure what we then feel and write about a subject like sexual desire. Is that something you think about?

SRINIVASAN

I have so much to say. How much am I going to say on the record? I have nothing close to a reconciled relationship to my own embodiment. Not only in the deep philosophical sense of not having overcome my own mind-body problem—the fact that I have this finite, vulnerable, embodied existence—but I have nothing like a reconciled relationship to my own legibility as a female subject, as a woman. As a young person, my intense fantasy was to be disembodied entirely. I started feeling that when I was probably five or six, but that fantasy stayed with me throughout my teenage years and into college. It wasn’t that I simply didn’t like looking a particular way. I didn’t want to look any way.

The other fantasy I had very intensely was about adopting the life of the figure of the sannyasi. Sanyas is the Sanskrit word for renunciation. The sannyasi is someone who has renounced everything—their name, their family relations, all property, all civic status. And they have no possessions. They wear an ochre robe and they go out in the world surviving as a mendicant. And it seemed so plainly obvious to me that this was the correct way of being in the world. Refusing to take up or dress in accordance with any kind of social role, an utter refusal of any form of gaze, any form of legibility, any form of relationality, which then, in my young view, would set my mind free. I still find it a very powerful vision of existence. And I still find it deeply painful that we aren’t total authors of ourselves, that we can’t just wake up and be something completely new.

But when it comes to dressing, I do tend to dress in a relatively feminine way. Part of it is just what makes it easier to go through the world or what feels like a form of armor that one can put on—which isn’t to say I don’t love clothes. I was very happy to appear in Vogue, for example. Hilariously, the person who notified me when that piece came out was Jacqueline Rose, on day one. Which I had so much respect for. I remember once Jacqueline walking into the British Library reading room—I didn’t know her then, although of course I admired her—in head-to-toe Chanel. And she sat down across from me, and I sat looking at her in wonder, and I realized I was going to get no work done. So I just picked up my stuff and left.

INTERVIEWER

You mentioned psychoanalysis earlier, and you seem committed to the idea that there are considerable constraints on how much we can know about ourselves. That idea has implications for the politics of desire and of identity, and for politics in general. And it feels in some ways like quite an unfashionable idea now.

SRINIVASAN

It is unfashionable. To think of the self as being obscure to oneself. I think you’re right to point to the phenomenon of identity politics as having something to do with this. It’s very important as people pursue the politics of recognition, to think of themselves as having a sovereign inalienable right to declare themselves to be something, to know themselves, and for their declarations of knowledge to be taken as dispositive.

And yet there are places where we risk overstating our ability to know ourselves. So if we think about something like trans politics, it’s very familiar to us that if you want a liberatory, trans-inclusive feminism, you need to take trans people at their word when they tell you who they are. But it’s important to notice that a kind of epistemic overconfidence is often in play when you’re thinking about trans-exclusionary feminism. This is a point I take from Jacqueline Rose, who says the question to ask of trans-exclusionary feminists is, Who do you think you are? How is it that you think you have such a reconciled relationship to your sexed body and your assigned gender and the way you are socially read? Her point is that all the ways in which we repress our discomfort and dissidence against the gender system haunt us in our dreams and our fantasies, where we are not stably always women or men. That’s a profound insight. And then the political question becomes, Whose ways of accommodating themselves to the oppressive system that is gender become socially sanctioned, and whose ways aren’t?

There’s a related issue with the way we sometimes talk about men, as if all men have a reconciled relationship to their manhood. As if it’s an easy thing, the demands of a certain kind of masculine performance, for both those men who fit it and don’t fit it. The idea that there’s no drama there, no anxiety there, I think is descriptively wrong and politically not particularly useful.

The right to be able to tell stories about ourselves is very important. It’s also very important that we have the right to change the stories we tell about ourselves. And that the stories we tell about ourselves are stories we tell in communion with other people. So much of what I say about myself is formed through what I’ve learned from other people who’ve helped me make sense of myself.

INTERVIEWER

The book covers a lot of tricky, fiercely contested ground. Do you worry about being misinterpreted?

SRINIVASAN

Are we going to write in a way where we could not possibly be misread? That kind of writing is bad writing. I was struck by this wonderful short review of my book in the Irish Times by Naoise Dolan, when she said something like, “Srinivasan isn’t worried about being misread. She’s not writing in a way that stops her from being viciously misread by her enemies.” I wasn’t trying to deliberately leave myself open for misreading. It just never occurred to me to write in a different way. But now I see that writing that wants to fearlessly engage with complexity is always going to be open to misreading. That’s true of so many great feminist texts, texts that open themselves up in those ways that I think continue to pay dividends.

INTERVIEWER

That’s why you teach people like Dworkin or Firestone?

SRINIVASAN

Everyone remembers Firestone’s line about shitting a pumpkin, which of course is not even her line—she’s quoting a friend. But what people forget, for example, is that extraordinary chapter “Down with Childhood,” on the oppression of children, which I love teaching my students because for so many of them it just feels like this disclosure of something they’ve wanted to say for so long about, for them, pretty recent experiences of being thwarted and infantilized and undermined and controlled as children.

Then she gets into freeing children’s sexuality, and pedophilia, and we’re in very murky and difficult territory. But there are certain feminists in this #MeToo moment who basically think we shouldn’t be reading Firestone for that reason. And it strikes me as profoundly anti-intellectual, but also as totally lacking what my colleague Rachel Fraser here at Oxford has called the carnivalesque in feminism. The importance of wackiness and weirdness and strangeness and audacity. I think it would be very sad if we lost that.

INTERVIEWER

You see that as an important quality for feminism specifically, or any movement?

SRINIVASAN

It’s important in any radical political tradition. It’s no surprise that utopian writing always has these wacky ideas. I mean, think about More’s Utopia, full of these strange possibilities, because the same political imagination that leads to the disclosure of new possible social arrangements also sometimes generates some crazy shit. The broadening of the sense of what’s possible, but also of what’s delightful and interesting about human life, has got to be central to a radical politics.

INTERVIEWER

It’s interesting, your attachment to that kind of unruliness. Because you yourself have come up within these institutions and been so successful—you seem the ultimate A student, in a way.

SRINIVASAN

I had a profile come out when I got the Chichele, and an old friend wrote to me to say that he thought it hadn’t captured my wackiness and sense of play and fun. I said to him that I don’t think that was the interviewer’s failing. I didn’t show that because I made a concerted decision to try and be taken seriously. There’s plenty of unruliness in my life. But it is undeniably true that I am the A student and in many ways the good Indian daughter who would bring home a 97, and my father would half-jokingly ask me where the three points were. Of course, it’s playing into a stereotype of Indian fathers, which he was knowingly doing. But it also comes from somewhere.

INTERVIEWER

It’s striking to me, actually, that in this book, which engages with sex, violence—things that can feel so deeply personal—you reveal very little about yourself. Is that in some sense a political choice?

SRINIVASAN

These essays are not personal essays in the contemporary mode. I’ve never written personal essays in that sense. At the same time, the essays feel very personal to me. I also have a habit of reading all philosophy as somehow betraying the self. I think that’s true of everything I write, not just these essays, but more abstract and technical pieces of epistemology. I feel myself haunting those pieces in, to me, quite obvious ways.

One thing is that I’m just instinctively private and want to be left alone. And I’m scared. I’m afraid of the internet and I’m afraid of the indelibility of it, the way that revelations of the self can never be undone. And then you’re always read through those revelations.

I’m also suspicious of biography as a genre, even as I have this biographical tendency when I read philosophy, which is supposed to be antithetical to biographical readings. But there are eruptions of the personal in the book. I have that moment where I make a joke about friends saying about me that I’m practically white—I thought a lot about whether I should keep that in or not. Sometimes what happens in essays is, I have more personal things and then I strip them out. But I decided to keep that. It felt like one of the most personal moments in the book, but for me, that’s always to take a position of intense vulnerability. I think part of the reason I like philosophy is because it… Nothing ever makes one truly invulnerable, but it gives one some immunity, at least some critical distance, some pretense of invulnerability. There’s also a question here about how much of political interest one can learn from my personal experience. I’m very aware of the limits of my own case. I mean, yes, I’m a woman. I’m a woman of color. I’m also just an extraordinarily privileged person and I don’t find my own story terribly interesting, is the truth.

INTERVIEWER

I’m suddenly thinking of that line in your octopus piece about the zoo and the aquarium—certain creatures being on display in captivity for the good of the species as a whole. That’s probably a very inappropriate connection to make.

SRINIVASAN

No, but see, those are the moments for me where I feel like I am… That to me is like a style of personal writing. I don’t write personal essays, but I feel like I’m constantly talking about myself. That octopus essay certainly feels like that. I mean, the dynamics of distance and proximity, knowability and unfathomability, are extremely personal preoccupations of mine, and I just find lots of ways of writing about them. I can be talking about octopuses. I can be talking about technical arguments in epistemology. I think I’m always just working out my own problems with other minds, though—my own mind and the other minds of actual other people I know and love. So maybe that’s a way of writing about the personal, in secret.

Lidija Haas is the senior editor of The Paris Review.

September 21, 2021

Redux: Too Sweet a Muddle

Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

Ali Smith, with Leo, in Cambridge, 2003.

This week at The Paris Review, the leaves are changing, the air is cooling, and the autumn equinox approaches. Read on for Ali Smith’s Art of Fiction interview, Robert Walser’s work of fiction “From the Essays of Fritz Kocher,” and Reginald Shepherd’s poem “A Muse.”

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, and poems, why not subscribe to The Paris Review? You’ll also get four new issues of the quarterly delivered straight to your door.

Ali Smith, The Art of Fiction No. 236

Issue no. 221 (Summer 2017)

INTERVIEWER

Were you pleased to see Autumn referred to as “the first serious Brexit novel”?

SMITH

Indifferent. What’s the point of art, of any art, if it doesn’t let us see with a little bit of objectivity where we are? All the way through this book I’ve used the step-back motion, which I’ve borrowed from Dickens—the way that famous first paragraph of A Tale of Two Cities creates space by being its own opposite—to allow readers the space we need to see what space we’re in.

Autumn leaves of bramble courtesy of Wellcome Images via Wikimedia Commons.

From the Essays of Fritz Kocher

By Robert Walser, translated by Damion Searls

Issue no. 205 (Summer 2013)

Colors fill up your mind too much with all sorts of muddled stuff. Colors are too sweet a muddle, nothing more. I love things in one color, monotonous things. Snow is such a monotonous song. Why shouldn’t a color be able to make the same impression as singing? White is like a murmuring, whispering, praying. Fiery colors, like for instance autumn colors, are a shriek.

Autumn leaves and fruits of bramble courtesy of Wellcome Images via Wikimedia Commons.

A Muse

By Reginald Shepherd

Issue no. 131 (Summer 1994)

He’s the friend that lightning makes, raking

the naked tree, thunder that waits for weeks to arrive;

he’s the certainty of torrents in September, harvest time

and power lines down for miles. He doesn’t even know

his name. In his body he’s one with air, white as a sky

rinsed with rain. It’s cold there, it’s hard to breathe,

and drowning is somewhere to be after a month of drought

If you enjoyed the above, don’t forget to subscribe! In addition to four print issues per year, you’ll also receive complete digital access to our sixty-eight years’ worth of archives.

September 20, 2021

Harvest Moon

In her monthly column The Moon in Full, Nina MacLaughlin illuminates humanity’s long-standing lunar fascination. Each installment is published in advance of the full moon.

Pieter Brueghel the Elder, Landscape with the Fall of Icarus, ca. 1558, oil on canvas mounted on wood, 29 x 44″. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

In 1957, the first satellite was launched into orbit around the earth. A gleaming metallic sphere about two feet in diameter with four long antennae, it had the look of a robot daddy longlegs. It weighed a hundred and eighty-four pounds and sped through space at about eighteen thousand miles per hour. After three months and more than fourteen hundred spins around this planet, it reentered earth’s atmosphere, blazing into flames.

This event, positioning something manufactured by human hands into the same realm as moon and sun and stars, was “second in importance to no other,” Hannah Arendt writes. It marked the moment when humankind named the relief that we would one day be able to escape earth’s bounds. Science made real “what men anticipated in dreams.”

In dreams, they anticipated the moon. They anticipated flinging themselves away from the earth up to the glowing pearl in night space. They’d been dreaming this for a long time, who knows how long. The moon, earth’s shadowy white sister, is the ultimate dream object. Even if not dreamed of directly, the moon is dreamtime’s overseer, companion; it’s the quiet warden of the night mind. Lyndon B. Johnson watched the Russian satellite move across the sky and knew: “Second in space is second in everything.” In 1961, John F. Kennedy said, “I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth.” And thus, we who are earthbound began “to act as though we were dwellers of the universe,” Arendt writes. Perhaps we always have been, but now we have the tools to see.

What’s the view like from the moon? Some argue that seeing earth from moon’s vantage gives “humans a false sense of independence from this planet,” as Daisy Hildyard writes in The Second Body. She talks of Earthrise, the iconic image taken from lunar orbit in December 1968 by the astronaut William Anders, which shows the moon’s pocked and chalky surface in the foreground and the swirling blue-white dome of earth floating three quarters full in the blackness. A collective wow resulted, seeing this planet from that perspective, and an altered sense of our place in the cosmic swing of things. Fifty years after the photograph was taken, astronaut Anders said: “It really undercut my religious beliefs. The idea that things rotate around the pope and up there is a big supercomputer wondering whether Billy was a good boy yesterday? It doesn’t make any sense.” A supercomputer in the sky doesn’t make sense, no, but what does? How do we make sense of what it means to flee our home planet? What happens when technology allows us to do something before we understand what we’re doing? Way up like that, “humans look down from a distance on all other forms of life,” Hildyard writes. It can “make the human feel superhuman.” A little like a god.

One man, recently, flew 282,480 feet into the air. Another man, recently, flew 351,210 feet into the air. Both entered space. Both reached a point so far away from earth, they escaped its gravitational tug. Of the two men, Richard Branson was first to penetrate, with Virgin Galactic. Jeff Bezos went higher up. Branson’s craft looked more like a traditional plane, with a “feathering system” to ensure a smooth runway landing. Bezos built a phallus with a feather painted on it, rising up the shaft. “He’s Icarus / he’s hickory-dickerous … He’s a god now, the talk of the town. He’s got no place to go but down,” writes John Hodgen in a poem called “For the Man with the Erection Lasting More Than Four Hours.” Launch to climax to landing, tumescence to detumescence, Bezos’s flight lasted a little over ten minutes.

Blue Origin is the name of his space concern. Our blue origin, the water all life came crawling from, the churning primal scene on our Blue Planet, our Mother Earth. He traveled as far away as he could, so far he couldn’t feel her pull, to look back down upon her, it, us, the whole blue world, knowing, too, that many were looking at him, the way we look up at the moon.

New Shepard was the name of Bezos’s rocket, named for Alan Shepard, the first American to go to space. But it announces the stakes. Aren’t we meant to hear an altered echo of good shepherd? Doesn’t it nudge the mind that way, even a mind that doesn’t know much about the Bible? John 10:14: “I am the good shepherd,” says Jesus. “I know my sheep and my sheep know me—just as the Father knows me and I know the Father.” The modern age began, writes Arendt, “with a turning-away, not necessarily from God, but from a god who was the Father of men in heaven.” That supercomputer in the sky.

Fathers, sons, flight—as far as fathers go, no one would rank Daedalus as World’s #1 Dad. Why didn’t he and his son Icarus make their famous flight at night? Moonlight won’t melt wax. But I think Daedalus knew exactly what he was doing. Years before his fateful flight with Icarus, Daedalus, master craftsman, took his nephew Perdix under his wing, to teach him about inventing. The boy showed promise: He saw a fish spine on the sand and invented the saw. He joined metal arms with a hinge, Ovid explains, “and while the first stood firm—erect and central—the second moving arm described a circle.” It was all too erect and central for Daedalus; he knew his nephew would outshine him, and he couldn’t bear to be the the arm in orbit around the brighter sun. So he shoved his nephew off a high wall. Athena swept in before the boy splattered on the cobblestone and turned him to a low-flying partridge. Did Daedalus know Icarus would steer himself toward a more powerful god, the fiery sun itself? Was his sun-timed flight on wings of wax a subtler shove? A father knows his son. No goddess switched Icarus into a bird or a fish. Hickory-dickerous, Icarus, ichthus, back to the water he went, joining the ghosts in the ocean.

And anyway, had they flown by moonlight, we wouldn’t have learned of the consequences of ambition unmatched by ability. And Brueghel would not have painted the shepherds and farmers not seeing Icarus splash into the sea, and Auden would not have written “how everything turns away / quite leisurely from the disaster.”

The Icarus complex, a lesser known diagnosis in the satellite of psychological complexes, is a condition of overambition, characterized by cynosural narcissism—a craving for attention and admiration, “a desire to attract and enchant all eyes, like a star in the firmament,” as the psychiatrist Henry A. Murray, who first coined the term, put it. It’s defined, too, by ascensionism, or the wish, in Murray’s words, “to overcome gravity, to stand erect, to grow tall, to dance on tiptoe, to walk on water, to leap or swing in the air, to climb, to rise, to fly, or to float down gradually from on high and land without injury.” Maybe one was not held enough as an infant. Maybe one’s mother did not return one’s gaze. A sense of free fall results. Can’t get your mother’s attention? You might try to defy gravity itself to get everyone else’s. Maybe you know people like this. Maybe you are like this. No goal too lofty, and a back-of-brain anticipation of tumbling through space.

When Bezos landed back on earth, he and the three other joyriders dribbled from the glans of the rocket. They beamed and waved, shaky-kneed, pumped their fists, looked Smurfie in their blue suits. They’d been up to the lore-glutted spacescape and returned to tell of it, tracking a path for future deep-pocketed thrill seekers to follow. Money can’t buy happiness, but it can help ensure you’ll be woven into an unfolding mythology.

They floated down and landed without injury, unlike Icarus, and unlike Phaeton, another son cautioned by his father, the god Apollo, when he was granted access to the chariot that pulls the sun across the earth. Not too high, not too low, Apollo says, and tries to dissuade him one last time: “Let me bring light unto the world.” Fathers sometimes have a hard time giving up the reins. Phaeton takes off, doomed from moment one. He flies too close to the earth, scorching its surface, boiling the seas, so that smoke-choked earth herself pleads with Zeus. “If all three realms are ruined—sea and land and sky— / then we shall be confounded in old Chaos. / Save from the flames what’s left, if anything / can still be saved.”

Save from the flames what’s left, if anything can still be saved.

We turned away from god as Father, but should the modern age end, Arendt asks, “with an even more fateful repudiation of an Earth who was the Mother of all living creatures under the sky?” What a bind we’ve put ourselves in, clinging to our mother’s skirts and simultaneously lighting her skirts on fire. What a bind we’ve put ourselves in, creating technology that outpaces our ability to understand its consequences.

It takes courage to launch oneself off the known surface into someplace new, to aim oneself into the place of dreams. And there’s no extinguishing the impulse to explore. But it takes courage, too, to turn toward the disaster, to look from ground level, part of it, and ask, What can I do?

Zeus throws a lightning bolt at Phaeton and he falls in fire, burning back to earth into the river Po. The body of water doesn’t matter. Mediterranean Atlantic Mississippi Amazon. The consequences of the Icarus complex: a craving for immortality, an internalized father-son rivalry, perpetual adolescence.

“To all you kids down there,” says Branson in a video from his spaceflight, “I was once a child with a dream, looking up to the stars. Now I’m an adult in a spaceship, with lots of other wonderful adults, looking down to our beautiful, beautiful earth. To the next generation of dreamers, if we can do this, just imagine what you can do.” A woman with a blond ponytail floats beside him, giggling.

Old chaos is closer than we think. The risk of having a view from space: being too far away to see exactly what we’ve reaped.

Nina MacLaughlin is a writer in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Her most recent book is Summer Solstice. Her previous columns for the Daily are Winter Solstice, Sky Gazing, Summer Solstice, Senses of Dawn, and Novemberance.

September 17, 2021

The Review’s Review: These Were the Angels

Illustration: Liby Hays. Courtesy of Hays.

Liby Hays’s Geniacs!, a graphic novel out this summer from the art book publisher Landfill Editions, takes place at a hackathon—truly inspired material for slapstick comedy, body horror, and philosophical reflection alike. This tech competition’s goal? Invent a new life-form. “People always think my ideas are dumb … but they’re purposefully so! Their failure is coded within them! It’s like when scientists artificially reanimate the cells of a dead pig’s brain. The brain becomes trapped in an infinite loop reliving the terror of its final moments. But within that narrow terror loop… We might find potential for new forms of thought to arise!” So muses our heroine, a morbidly minded wordsmith undercover as a “po-ent” (poet-entrepreneur). Her (hot, tattooed) slacker partner would rather copy and paste some old code, though, than entertain her inefficiently emo-poetic concepts. Hays’s detailed black-and-white illustrations are as gymnastic, compositionally, as her characters’ dialogue: her panels cut across the page in dizzying fits of polygons and word bubbles that leave us spiral-eyed, minds buzzing, cartoon birds circling our heads. A canny and cryptic meditation on group projects, life, “life,” art, and the cheat code lifestyle only slightly more surreal, though much more fun, than my worst nights of coding. —Olivia Kan-Sperling

“In a city we are forever brushing sleeves with our other possible selves,” writes Lauren Elkin in her latest book, No. 91/92: A Diary of a Year on the Bus, culled from a series of iPhone notes compiled during her 2014 commute in Paris. “Underground we go shooting through the tunnels trying to survive and be happy.” Drawing on the works of Georges Perec and the subway poems of Jacques Jouet, Elkin situates her observations within an Oulipian history of randomness and chance, suggesting that a life mediated through a screen is just as susceptible to the what-ifs, daydreams, and abrupt interruptions of a life lived away from one. —Rhian Sasseen

“I’m talkin’ neat, like freak. / I’m talkin’ neat, like fleek. / I’m talkin’ neat, like a geek.” —Brian Ransom

Jenna Gribbon, Interior Lightscape, 2021, oil on linen, 80 x 64″.

I encountered Jenna Gribbon’s Watching Me Swim (2018) on a corner of the internet called gay Tumblr, which is practically a tautology. It was a coup de coeur for me, seeing her work for the first time. Running through October 30 at Fredericks & Freiser, her solo show “Uscapes” comprises newer works. It’s no surprise that Gribbon’s girlfriend Mackenzie Scott (not that one), who performs music under the name Torres, appears as muse in every piece. This has become a hallmark of Gribbon’s work, as have lovely, messy domestic scenes—Scott clipping her toenails on the lip of the bathtub, for one—and cleverly composed, reflexive nudes. It’s easy to fixate on the details—the omnipresent neon-pink areolae, the intricately rendered folds of fabric, the glint of Scott’s fingernails as she props her hands in front of her vulva in one portrait, the fleshiness of a belly in another. These minutiae clash nicely with the works’ louder elements. Fat swipes of paint bear the memory of a brush’s grooves, and about half a dozen pieces on view are massive, like the nearly seven-foot-tall Interrogation Lightscape (2021), in which Scott appears as a kind of giantess, haloed by white light, sitting naked between a pair of thighs, holding eye contact. As we orbited the gallery, my buddy spun around and let out a laugh. “She’s always teasing us, you know. She’s making fun of the viewer,” they said, gesturing toward a painting of Scott pissing into the dirt. Toying with the voyeur—and with the tropes of figurative painting—is surely an energizing force here. Gibbon’s paintings emerge, in her own words, “from inside the scopophilic feedback loop.” —Jay Graham

Getting me through this week is The Magic of Now, a new live album by the pianist and bandleader Orrin Evans, which was recorded this past December at the Smoke Jazz & Supper Club, in New York City. The band photo in the CD shows the rhythm players—Evans, the bassist Vicente Archer, and the drummer Bill Stewart—all masked, their hands flying over their instruments; only the rising star sax player Immanuel Wilkins isn’t masked, for obvious reasons, but he’s surrounded by see-through barriers. It’s a moving document of the perseverance of art through the pandemic, and the music makes a powerful case for art’s necessity. This is just really great straight-ahead jazz, nothing tricky, just lots of power and passion and the chance to hear Wilkins, who seems to be everywhere in jazz right now, play the hell out of his horn as though all our lives depended on it. —Craig Morgan Teicher

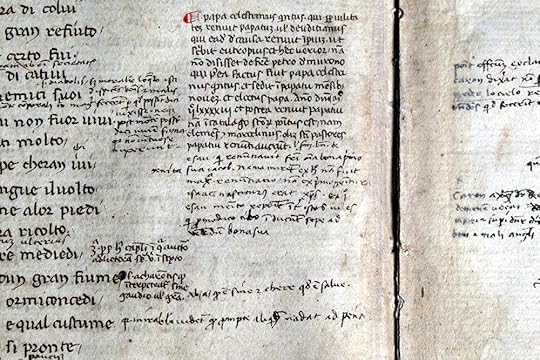

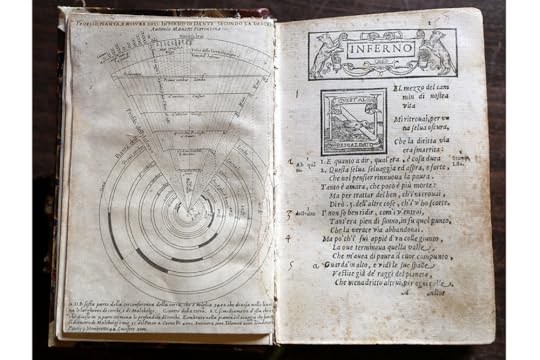

One undeniable certainty about studying religion in any academic way is that, without even trying, you find yourself having opinions on famous heretics—more precisely, you have favorites. My personal favorite heretic is Menocchio, the subject of Carlo Ginzburg’s 1976 study of sixteenth-century popular culture The Cheese and the Worms. Ginzburg’s project breaks the mold of social history by building a narrative from the bottom up, using source materials as far removed from structures of power and influence as he could dredge up, trying even to get at the texture of oral culture lost to time. The protagonist that emerges is an incredibly learned, charismatic, and irreverent miller who, in the face of the Roman Inquisition, imagined a view of creation that rings through centuries by way of Ginzburg: “All was chaos, that is earth, air, water, and fire were mixed together; and of that bulk a mass formed—just as cheese is made out of milk—and worms appeared in it, and these were the angels.” —Lauren Kane

Carlo Ginzburg. Photo courtesy of Johns Hopkins University Press.

How a Woman Becomes a Piece of Furniture

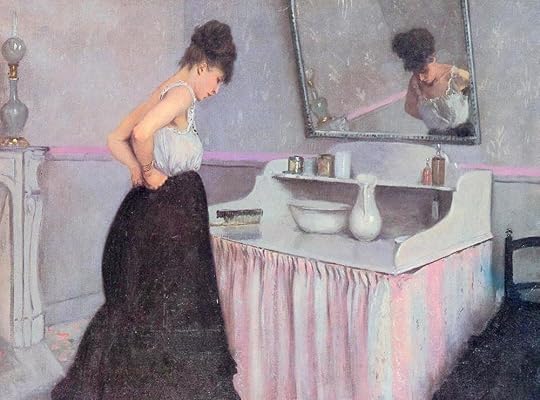

Gustave Caillebotte, Woman at a Dressing Table, 1873. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

My grandmother collected perfume bottles, a seeming whimsy for a woman of such plainness and ferocity. I have three of them, given to me when she was still alive. They lived in a drawer and then later, in a decorative moment, on the bookshelf, where I have since placed them higher and higher out of reach, as my daughter has attempted to climb up to play with them, a slow-moving game between us, until now they are so high up as to be out of view. I tend not to be sentimental about objects, but I at least don’t want them to break, this being all I possess from my grandmother, anything else guarded by her surviving daughter, who, having remained unmarried, still lives alone in the house in which she was born, that being the way in my family. The bottles are candy-colored glass—blue and purple twins with matching Bakelite flowers as the stoppers, and another newer, smaller one, with complementary hand-painted purple flowers with bluish-green stems and yellow pistils at the centers, and with a gold atomizer. They are not valuable—objects in my family become antiques only through accruing dust in the house they’ve inhabited, on mantles and in glass. I can still see the menagerie that resided on the heavy wooden dresser in my grandmother’s bedroom, which was covered with plastic and underneath it a lace doily. On top of the doily, viewable through the plastic, were black-and-white photographs: portraits of relatives, baby photos, and photographs of her late husband, who died when she was still a young woman with a young child, leaving her a widow until her death in her nineties, half-paralyzed from a stroke but still ruling the world from her dining room table, waving her grabber at her grown children, gleefully threatening to hit them with it for whatever crime committed, usually (her word) stupidity. The table itself was covered always with at least a cheap cloth-backed vinyl or plastic decorative tablecloth of garish pattern, frayed or cracking at the edges, and for holidays, a nicer, solid-colored linen cloth on top. Underneath was the heavy mahogany table, like all the furniture in my grandmother’s house, the immovable furniture of generations. My grandmother’s collection of perfume bottles crowded next to her jewelry, which was minimal and rotely worn, including not only her heavy wedding band, which my sister keeps asking for, but also her silver watch, which my grandmother must have had to wear to keep time while working the linens counter at Marshall Field’s all those decades after becoming a widow, having had to close up her husband’s butcher shop and store where she had previously presided behind the register, the calves widening from girlish into matronly, all those varicose vein decades, after suddenly becoming a single mother with a young child to raise, her older grown sons, the twins, away in the Navy, later returning in order to gather around their mother, one staying unmarried and in that house until his untimely death, the other moving away, but not too far, that other being my father, who accrued his own museum, having lived for his own decades in the state of the widower, although his savings account was never the subject of existential dread, he having been the one who made all the money in his marital life, my mother at home with the children, as was the way. She was a saint, an angel, both my uncle, my grandmother’s son, and my father, my grandmother’s other son, said about both their mother and my mother, respectively, at their funerals, one having died of an astonishing old age, and the other, at a sudden and tragic middle age. I didn’t recognize who they were talking about. All I recognized was the empty monologue of Catholicism, which serves to erase by anointing the woman at home, who only exists in service to others but not to herself. Does she even exist, I often have wondered, to herself? Writing this I have no idea why my grandmother collected perfume bottles, were they gifts that her sons brought home from overseas, and they began to unthinkingly accumulate, over birthdays and Christmases? My grandmother cut her ridged nails with the kitchen scissors, she never wore makeup, let alone perfume. I have no idea what my grandmother, or my aunt, or my mother, thought about at night in their empty houses, in the solitude of caretakers. I have no idea if they were unhappy, whether they thought of their girlhood, or when the children were young, whether they had regrets, and if they could, what would they confess? I have no idea because I never asked, and they would never have said. It would have been an impossibility. Their inner monologue would have been closed to me.

What you need to understand is how a woman can become a piece of furniture. The kind of woman who lives in a house like a museum, filled with artifacts of her past relevance. In the Portuguese writer Maria Judite de Carvalho’s only novel, the compact, merciless tragedy Empty Wardrobes, published originally in 1966, the widow Dora Rosário manages an antique shop referred to by her young daughter as the Museum, an occupation secured for her by a pitying network of female acquaintances, the plight of necessary supplications that Carvalho mocks, that bitter sharpness of waking up to a society’s cruelty, masked by exhaustion. What you need to understand about Dora Rosário is she is meant to be ancient, past her prime, meaning in the tradition of great women’s melodrama, she is thirty-six years old. While he was alive, her incompetent husband refused to let her work, she was supposed to be at home, taking care of her child, who grows to be a cheerfully callous teenager over the course of her mother’s decade-long career as a widow. For that past decade as well Dora has lived amid the antique furniture at the Museum, dressing like an “off-duty nun,” tending also to her late husband’s memory, the required dissolution of self like an ecstasy of sustained mourning brought to an art form. The permutations of her consciousness are an exercise in the way the imagination can drift in tedium, resembling the clerk Bernardo Soares in another famous translation from Portuguese by Margaret Jull Costa, Fernando Pessoa’s Book of Disquiet. The exquisite style of the passages set amid these baroque objects that possess more value than the solid and unmoving woman hired to guard over them. The ache of this emptiness and dustiness, the matron as a museum:

She had spent the best part of the last ten years there, among tables large and small, some semicircular and propped against the wall, others like long-legged birds, half-asleep and slightly unsteady on their feet, others standing imperiously on sturdy legs with strong metal claws gripping the floor. There were also sundry writing desks and a tall, delicate Etienne Avril escritoire, chests dating from various centuries, a solitary Regency lounge chair, its upholstery wearing thin, and many other pieces of furniture, all with very full curriculum vitae and all devoured by generations of energetic woodworms, but still very solid, gathered together like decaying aristocrats in a home for superior elderly folk. Glass domes covering beautiful clocks that had long since stopped, images from the eighteenth century, ornate boxes, exquisite, elegant ivory figurines, odd plates held together with metal brackets, a fine Persian rug, and, scattered here and there on the walls, frozen after many years in flight, were a profusion of Baroque angels, chubby and cheerful, modestly veiled or else fully clothed and even wearing boots, all of them with their bird wings spread. It was there in the Museum—because it really was more museum than shop, since it had more visitors than buyers—that Dora spent her days.

There is a gesture among the elders in my family of a slight turning away when anything taboo is brought up, the subjects one is not supposed to refer to—adultery, divorce, the great unhappiness of a traditional marriage. Empty Wardrobes is set amid a cloister of three generations of women who also have been refusing to hear any such taboos, or perhaps truths, except in the quiet hangover of the monologue of a maiden aunt becoming undone (explained away as eccentricities, or an episode), which then catalyzes the midnight confession of the mother-in-law/matriarch—whose aging appearance across the novel is rendered in a series of hilarious grotesques—to her daughter-in-law, Dora, the closed and severely unfashionable widow. This speaking of the unspeakable between generations of women unleashes a series of events, which opens up an abyss of regret for our heroine’s wasted life, and, temporarily, a return to the self, or a new self, with optimism’s ephemerality and artifice. Then sometime later on, supplying the novel’s frame, Dora Rosário, out of will and despair, tells of the tragedy of her life to the devastatingly witty yet still mournful narrator, a former friend and tossed-aside mistress of one of the men, a buffoon, all of the male characters in the book being buffoons, mere shadowy catalysts who still unfairly hold all the power. There is also the teenage daughter, unthinking in her own youth and beauty about her pronouncements of her mother’s hopelessness, who never sees her mother’s lifetime sacrifice, although there is a recursive sense of her future fate once she gets what she thinks she always wanted, which is to become a rich man’s wife.

Reading Empty Wardrobes I thought of the great Modernist novels of wives, which are by their occupation works of tedium and duration—The Passion According to G.H. by fellow midcentury writer of Portuguese Clarice Lispector, Marguerite Duras’s The Ravishing of Lol Stein, and of course, Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway (although Carvalho’s characters are funnier and more cruel than Woolf’s). Reading this novel, I felt awakened by the possibility of literature, which is to tell of a consciousness that in real life is rendered dull and redundant, incapable of imagination or higher thought (the disappearance of the clerk, as well as the wife and her past tense, the widow). It feels shocking for such a complete and alive work of literature like this to have been untranslated for so long. This is a hilarious and devastating novel of a traditional Catholic widow’s consciousness, encased like ambered resin in the ambient cruelty of patriarchy, an oppression even more severe in the God, Fatherland, and Family authoritarianism of the Salazar regime in Portugal. A work like this, set in the regime of a dictator who weaponized Catholicism and “family values,” is by its very nature deeply political, even if—no, especially if it’s set in a series of interiors, in the domestic space, in the space of service. I read this novel with something resembling a rapturous grief, as if I couldn’t believe this consciousness had finally been rendered in literature, the consciousness of so many women familiar yet unknowable, no longer muted, not saturated with sanctimony but alive, alive with rage transmuting disdain into hilarity by sheer force, alive with intense paroxysms of sadness.

Kate Zambreno’s most recent book is a study of Hervé Guibert, To Write As If Already Dead. She is a 2021 Guggenheim Fellow in nonfiction, and is at work on a collection, The Missing Person.

Introduction used by permission from Empty Wardrobes (Two Lines Press, 2021). Copyright © 2021 by Two Lines Press.

September 16, 2021

All You Have to Do Is Die

Graham Crumb, 2011, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

People were drinking wine out of plastic cups. The chairs were pushed close together. Bags were tucked under feet. I sat on the bookshop stage with two other writers, ready to read our ghost stories. Before we began, the moderator asked, “Do you believe in ghosts?” After a pause, we spoke of doubt. Creepy incidents were related. I found myself saying that perhaps the dead might be watching us.

I’ve never seen a soul move through the air. I am not sure that we are anything more than a skin-bag of electrical impulses. But ghosts are different from the other uncanny citizens. They are only one step away from the known. To become a ghost, you don’t have to be bitten by a vampire or receive a curse or encounter a mad scientist or fall under the spell of a full moon. All you have to do is die.

Still, I imagine the first days of ghosthood would be tricky. There are so many different hauntings, so many ways to do it. In a way, it reminds me of puberty. The unpredictable shifts. Sudden changes in weight and the way people see you. Unexpected blood. Puberty was a process I did not enjoy and, unluckily for me, it was nothing I could google—or more accurately “Ask Jeeves,” the search engine my IT teacher recommended. It was a time when strange men’s penises appeared in my Hotmail account and were not caught by the junk filter. I didn’t trust the internet. And so I found myself flipping to the back of the magazines my classmates’ mothers bought. The paper was always wrinkled from the girls’ hands that had come before. At the back would be a quiz or a decision tree to tell you what sort of person you were or would become. Sometimes there was the freckle of a biro mark, or an initial to mark the previous reader’s path. It was reassuring.

Playing around, I tried to devise one as an introduction to that stage of life yet to come—our ghosthoods.

But then I wondered if there was a reason the quiz, though my favorite part, always came at the very back of the magazine. Perhaps first you needed to see the parade of girls with their flattened hair and sparkly eyelids to begin to feel out who you might want to be. Sadly, I have no ectoplasmic photoshoots to present to you. So here is the next best thing—

Seven Big Questions for Your Life After Death

If you can answer all of these, then you’ll have a plan. Or, at least, a ghost story of your own.

1. Where will you haunt?

Castles are the obvious place. But you have to pity a castle ghost these days. It must be difficult to haunt a National Trust property stocked with brochures and push-chairs and a cafeteria where you can get tea and scones and jam in a miniature jar.

Though perhaps such refinement would appeal to you. Queen Mary’s doll’s house stands in Windsor Castle. It boasts gilt chairs, electric lights, a wine cellar, and of course a library. Inside the library are miniature leather-bound books, each with its own miniature story. One of these books is by Vita Sackville-West. Her story narrates the life of that doll’s house’s very own haunting. This smallest of ghosts eats at the miniature table with miniature cutlery and sleeps in every bed of the house. She runs overflowing baths and has a generally fabulous time. And no one understands how this mess is being made.

Maybe your aspirations are more humble. Maybe it is your own bed, your own walls that you wish to haunt. Virginia Woolf has kind ghosts in common with her lover Vita. In “A Haunted House,” Woolf writes of a couple who wander their beloved home to keep it “Safe! Safe! Safe!” They and their house pulse with their ghostly joy. At times, I have looked at my own walls—painted in Dulux white—and wondered about staying here should lightning strike me down. I consider that, eventually, the spider plant would be tossed away, the radiators with their bubbled paint pulled out. Still, there are other options. Lately, I have been writing only ghost stories, and it is usually place that I start with. A hotel, a reliquary box, an Uber. There are so many locations to be dead inside. You could say I am still considering my options.

Maybe you’d rather take up residence in a human body. It has been known to happen. In Japanese Buddhist legend, there is a story of a hunter who was possessed by the spirit of a fox he had killed. That it was a fox is no coincidence. In Japanese folklore, foxes are the tricksters of the spirit kingdom. By beating their tails against the ground, they may create fox fire. They can give out money that turns to leaves in the morning. Or cause rain to fall from a clear sky.

Can you feel what it would be like to sink into another’s bone and blood and limb? Can you feel the way your spirit might have to shift? Or can you imagine a creature you killed coming to rest inside your bones?

2. Who were you when you were alive?

An early draft of this essay was called “Ghosts Are People, Too.” But that implies a belief that I don’t hold. If spirits exist, if the soul can walk free from the body, then why should it only be ours? To some extent, you and the gods have already decided what you are in life. I’d be surprised if you are anything other than a human. But perhaps that is hasty. If you’re reading this in print then you’re reading it on the finely shredded life of a tree, and who is to say that the tree isn’t reading, too?

In Shintoism, there is a word for the place where a spirit might take up residence, the Yorishiro. It could be a tree or a shrine. Holy trees are inhabited by the kodama—literal translation: tree soul or tree spirit. Such trees are usually strung around with hemp rope from which paper lighting is hung to indicate their holiness. Toriyama Sekien’s 1776 woodblock print catalogue of yokai (monsters/spirits) begins with an illustration of a kodama. A white gust pours from a twisted pine tree and along this gust walks an old woman bent-backed and long-necked, following an equally aged man. The caption included in the picture says that the spirit of the tree will show its form after one hundred years.

The word for echo is the same as the word for tree spirit in Japanese. Supposedly because an echo is the spirit of the woods replying to a shout. I recently came across the work of Takei Takeo and learned about his book Kodama no denki, in which he gives the story of one such tree spirit. This book, made in collaboration with an artist, was illustrated not in ink but in marquetry—slivers of wood cut and pasted to the paper to form images. On the last page, Takei suggests you attempt to listen to the ‘voiceless voice’ of each tiny slice of wood. Should you be in Boston, you can find this book at the Boston Museum of Fine Art and give it a try.

3. Would you rather receive an invitation?