The Paris Review's Blog, page 97

November 9, 2021

Divorce Does Funny Things

Benjamin Shaw, Aberdeen Quayside, 2003, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

The man I was meeting worked on the Brent Field. He was a kind of Typhoid Mary, having worked on the site of several accidents, always escaping unscathed. He was staying in a large, anonymous hotel behind Holburn Junction. The lobby was a columnar space several floors high. Its windows were covered in a kind of mesh, which muted the daylight and cast everything in a cool, neutral gloom. I took a booth, upholstered the same indeterminate shade, and waited for him to appear. There was some splashy abstract art on the walls, and a long, curved reception desk at the back of the room. People were moving about in the shadowy recess behind it, like stagehands in the wings of a theater. No one showed any inclination to come out.

The meeting had been arranged by a mutual acquaintance, and this connection, coupled with the blandly corporate look of the building, made me feel as if I were the one being interviewed. After a few minutes, a man stepped out of the elevator. He was small and powerfully built, with red hair and a full red beard. His cheeks were round and rosy, and his teeth pushed against his upper lip, so his mouth didn’t quite close, giving him a look of breathy suspense. He sat down opposite me and rubbed his hands together, in what might have been an expression of anticipation, or an attempt to get warm. The weather was hot and humid, and the air conditioning was turned up high.

“So you’re the writer?” I nodded shyly.

“I’ve often thought I should write a book.”

“You should,” I said. “Why not?”

This was my default response to a statement I heard at least once a day, sometimes more, and the opposite of what I thought. What I really thought was that if people knew how difficult it was, no one would attempt it, that there must be a conspiracy of silence among authors, since this misconception that everyone had a book in them was so widely held. Usually, at this point in the conversation, the person talking about writing would say he didn’t really have the time, I’d agree that it was time consuming, and the subject would be dropped. But this man surprised me, by pushing three cellophane packets across the table. They were three stories from his life, that I could use, or not, as I saw fit. It had taken him several days to write them up, but he’d found the process curiously therapeutic, so in a way, they’d already served their purpose.

“If nothing else,” he said, “they might give you a laugh.”

I thanked him, and tucked them into my bag. I asked where he was going that afternoon. The Brent Charlie, he answered, with a grimace. Two and a half hours in the chopper. Three, in an oncoming wind. If you had the misfortune to be sat next to a big guy—and for some reason, there were a lot of big guys on the Brent Field—you’d spend the flight perched on the edge of the seat. From the Charlie, he’d fly to the Alpha. He was a plumber, and the role was peripatetic, so over the course of one trip he’d work his way around all four platforms.

“Which one’s your favorite?” I said idly. I was thinking out loud, as I did more and more these days, but he surprised me a second time, by treating the question with more seriousness than it deserved.

“Probably the Alpha. It’s small, there’s not so many guys on it, and it’s just been done up. I used to like the Delta. It’s going through decommissioning just now, so the legs will be cut off in six months’ time. And then the Delta will be no more.”

“Which one’s the worst?”

“The Charlie’s got the most people on it, and only a tiny wee gym. The Bravo’s bad for arseholes.”

His voice was low and sleepy, as if lulled by its own susurration. Some of his sentences petered out into nothing. At other times he’d pause, before picking up where he left off.

“The best rig I ever worked on was the Lomond. The atmosphere there was always good. The Tartan was probably the worst. On the Tartan, the cabins had two bunk beds and a cot, for a fifth person. You had three guys on days, two on nights, and one bathroom between the two rooms. Ten people to a bathroom. It was wet the whole time. I’ve worked on the Claymore as well. That’s a disaster of a rig.”

I wondered if his choice of words was deliberate.

“James said you were on Piper Alpha.”

“I was. Only one trip. I was twenty, and very excited to be earning one pound eighty an hour. It was a massive platform, an old rusting bucket, even then. It’s like stepping off a bus, then seeing it go off a cliff. You think, ‘I was on that place and now it’s at the bottom of the sea.’ There but for the grace of God, you know? You read the names, looking for someone you know. My old foreman Jim McCulloch … he was on there.”

He sighed, and looked past me. A waitress had emerged from the back of the room. She was dressed in a drooping dark tunic, and trousers so long they covered her shoes, so she looked as though she was gliding about on casters. She took our order and slid back across the room, towards the desk. Once she was gone, he started talking again.

“There’s a veneer of safety now. But the way a multinational views safety off West Africa is different from the way it views safety in the North Sea. You see pictures of guys welding with cling film wrapped around their eyes. If someone gets injured out there, it won’t make the news, it won’t affect share prices. Or is that too cynical?”

“You’re asking the wrong person.”

He smiled, displaying large, rounded teeth. Many of the men I’d met looked worn out by the physicality of their work, but this man emitted an air of wholesome good health. He must have been in his late forties, at least, to have worked on Piper Alpha, but in the dim light of the lobby, he appeared almost ageless.

“We’ve had a lot of deaths on the Brents over the years. We had the Chinook disaster forty-five people who’d left the Brent Delta. There were two guys killed down the leg of the Brent Bravo. During the last downturn.”

The man explained that oil companies were expected to deliver nominations—specific quantities of oil and gas—to the grid. Failure to do so incurred penalties. But there is a constant tension between production and compliance. Platforms become fatigued over time. Battered by the elements, their structures need continued maintenance. Routine maintenance often puts operations on hold, and during downturns, companies will deploy quick fixes. In 1999, it was alleged that Shell had a protocol known as TFA: “Touch Fuck All.” Permits apparently came with TFA scrawled across them, meaning workers should leave equipment alone, rather than risk a shutdown. Shell commissioned an internal audit, which corroborated the allegations and recommended immediate intervention. But the auditor was transferred, and the report did not surface again until 2006, shortly before a fatal accident inquiry into the Brent Bravo deaths.

One day, the man said, two workers were sent to the bottom of the Bravo’s leg to investigate a leaking pipe. At that point, there were many leaking pipes on the platform. Many grazes and abrasions in its fabric. The bottom of the leg was a stinking, horrible place. Poorly lit and dank. The men had to stand on a metal grate above a stagnant pool of bilge and patch the leak up with a piece of neoprene and a hose clamp. What they didn’t know was that the clear, scentless substance leaking from the pipe was liquid hydrocarbon, which is deadly when inhaled. As it hit the grating below it began to evaporate, swelling back around them in a doughnut cloud.

The alarms activated and the valves designed to divert gas away from the plant and up toward the flare meant to burn it off kicked into gear. All except one, which failed. The system hadn’t been tested for a while. To test is to touch. The men tried to make it up the stairs but they were too far down. They were asphyxiated in minutes.

Shell pleaded guilty to safety lapses and was fined £900,000, a little less than it earned in an hour.

The man paused and looked out toward the street. People were walking past, pale silhouettes against the mesh. The traffic at Holburn Junction was a faint hum.

“There was another one,” he said. “A few years back now. On the Delta. A man filled his pockets with tools and jumped off the side.”

I stared. My mouth hung open in sympathy with his.

“I’ve heard that story so many times. I assumed it was an urban myth.”

“Oh no. It really did happen. I saw him half an hour before. I passed him in the corridor and said, ‘All right Jimmy, how you doing?’ He never took me on, just walked right past. I didn’t think anything of it. Then they started putting calls out over the loudspeaker, asking him to report to heli admin. I said, ‘Maybe he’s jumped off the platform.’ As a joke, you know? Can you imagine how I felt afterwards? When the alarms went off: ‘Man Missing.’ Then the story came out. He was very money-orientated. He worked a lot of overtime. This is only what I’ve heard, mind. But he was the tightest guy in the world. Money was king. I think that played a part in it. His wife was leaving him, and she was going to get the house. It drove him mad. Perhaps he thought that with killing himself, she wouldn’t get anything. Insurance doesn’t pay out for suicide.”

“Divorce does funny things to people.”

“Aye.” He moved back in his seat to make space for the waitress, as she set our drinks down. “That it does.”

Tabitha Lasley was a journalist for ten years. She has lived in London, Johannesburg, and Aberdeen. Sea State is her first book.

From Sea State by Tabitha Lasley published by Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins. Copyright © 2021 by Tabitha Lasley.

Redux: Plates Collapse

Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

This week at The Paris Review, we’re celebrating the release of The Paris Review Podcast Season 3 and lowering the paywall on four pieces featured in the first two episodes. Read on for Robert Frost’s Art of Poetry interview, Yohanca Delgado’s short story “The Little Widow from the Capital,” Antonella Anedda’s poem “Historiae 2,” and Molly McCully Brown’s essay “If You Are Permanently Lost.”

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, and poems, why not subscribe to The Paris Review? You’ll also get four new issues of the quarterly delivered straight to your door.

Interview

Robert Frost, The Art of Poetry No. 2

Issue no. 24, (Summer-Fall 1960)

So often they ask me—I just been all around, you know, been out West, been all around—and so often they ask me, “What is a modern poet?” I dodge it often, but I said the other night, “A modern poet must be one that speaks to modern people no matter when he lived in the world. That would be one way of describing it. And it would make him more modern, perhaps, if he were alive and speaking to modern people.”

Fiction

The Little Widow from the Capital

By Yohanca Delgado

Issue no. 236 (Spring 2021)

The widow arrived at LaGuardia on a Sunday, but the rumors about the woman who had rented a big apartment, sight unseen, had taken an earlier flight. We had already reviewed, on many occasions and in hushed tones, in the quiet that comes after long hours of visiting, what little we knew about the widow and her dead husband.

Poetry

Historiae 2

By Antonella Anedda

Issue no. 231 (Winter 2019)

The book rotted by the rain, the clay that’s slipped,

the earth screeches, plates collapse,

the walls lose their grip on the paintings,

nothing is aligned like the planets we think we understand.

Within the shock announced this morning by the howling dogs

their muzzles pointing toward an imaginary swarm of bees

the floor slides toward the void. We, too,

run away in the wake of a memory of the species

(oh, storm made of fire and basil,

of lamps and beds askew

and you, mountain, gulping water and air)

while the house breaks up and disappears.

Nonfiction

If You Are Permanently Lost

By Molly McCully Brown

Issue no. 231 (Winter 2019)

Even on a much smaller scale, space makes no sense to me. I walk all the way around the perimeter of a room to reach a door that’s immediately to my right, and I set my glass down half an inch from the edge of the table with such frequency that anyone who knows me well gets used to nudging it back again and again over the course of an evening in this small, choreographed two-step.

If you enjoyed the above, don’t forget to subscribe! In addition to four print issues per year, you’ll also receive complete digital access to our sixty-eight years’ worth of archives.

November 4, 2021

The Review’s Review: Spiky Washes

Dominique Goblet’s Pretending is Lying.

A Seattle Queer Film Festival screening of the documentary film No Straight Lines, which profiles five crucial queer cartoonists including Rupert Kinnard and Alison Bechdel, brought me back into the graphics circuit. After reluctantly reading the final panel of Dykes to Watch Out For last weekend, I’ve turned to Pretending Is Lying, a fractured graphic memoir from the Belgian artist Dominique Goblet and the first English translation of her work. Goblet is as invested in her own fraught filial relationships as she is in the work of memory, and the emotional texture she achieves with only graphite, charcoal, and a little ink is stunning—soft leaden shadows, aggressive gradient shading, expressions rendered in jagged lines, dialogue scrawled in restive script. Inaugurated in 1995 and ultimately published in 2007, the book became a kind of living artifact to Goblet’s L’Association editor: “This book smells of oil, grease pencil, humid wood, the disorder of the street market; it exhales twelve years of well-tempered promises, carefully untied and resolutely wrapped up.” —Jay Graham

This week I’ve been basking in the spiky sonic wash of Music for Drums and Guitar, a duo album by guitarist Miles Okazaki and drummer Dan Weiss, two of the leading figures in edgy contemporary jazz circles. Both are absolute masters on their instruments, and both have released many albums as leaders of their own groups, often with each other as members, having collaborated for more than twenty years. This self-released album (which was recorded during the pandemic) comprises two suites of music, one by each musician; the songs are jangly, sometimes heavy, borrowing from hard rock and metal as much as jazz, full of surprising musical details. One has the sense that not only can Okazaki and Weiss anticipate each other’s next moves, but that they are both deeply dedicated to realizing each other’s artistic visions. —Craig Morgan Teicher

“Imagination is delicate,” Teju Cole observes in an essay on grief and the form of the photograph early on in his new collection, Black Paper: Writing in a Dark Time. “It imposes decorum. A photograph insists on raw fact, and confronts us with what we were perhaps avoiding.” In these thought-provoking essays on image-making, the rightward lurch of global politics of the last five years, race, the migrant crisis, artists and thinkers ranging from Caravaggio to Said, and more, Cole writes as though he were taking a photo: he is insistent on highlighting the raw facts, the situation laid bare. Through such clarity, the reader cannot look away. —Rhian Sasseen

Detail from Linda Okazaki’s cover art for Dan Weiss and Miles Okazaki’s Music for Drums and Guitar.

A Philosophical Game: An Interview with Saul Steinberg

Saul Steinberg, Untitled, 1959, gouache, ink, pencil, and crayon on paper, 14 1/2 x 23″. Private collection. © The Saul Steinberg Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.

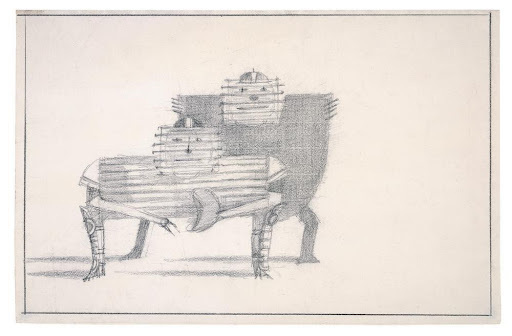

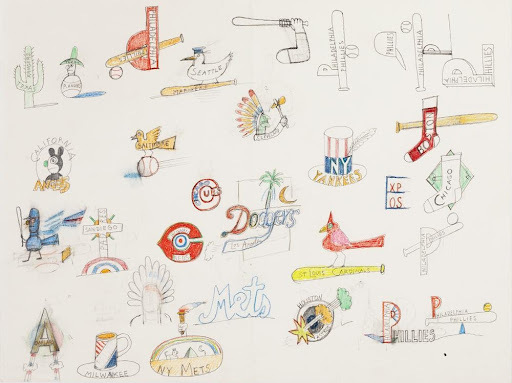

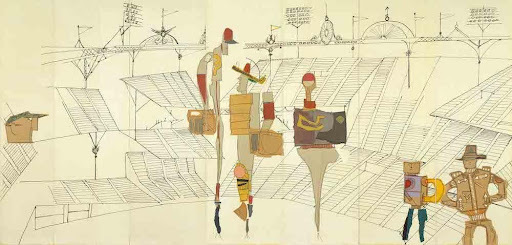

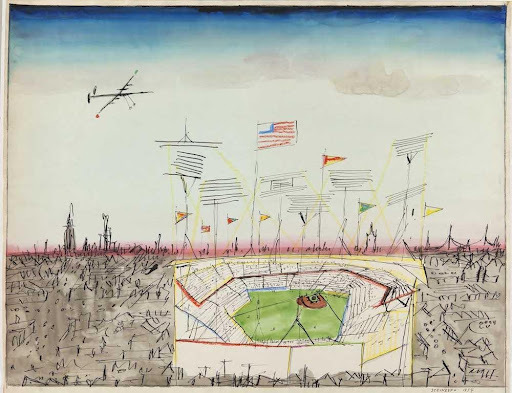

The artist Saul Steinberg, who immigrated to the United States in 1942, was deeply preoccupied with identifying the essential threads of American life. For him, baseball was rich material. In 1954, he traveled with the Milwaukee Braves, taking them as subjects for his deft, sharp linework. The sketches from that trip are some of Steinberg’s most recognizable work, and were published in LIFE magazine in 1955.

In 1972, The Paris Review began an interview with Steinberg that was never published. The manuscript of some thirty-odd transcribed pages was catalogued by the Morgan Library archive staff and then left alone, until the Review recently rummaged through some folders and pulled it out.

Like Steinberg, this magazine has always had a soft spot for baseball. In 1958, our founding editor George Plimpton took to the pitcher’s mound to try out his fastball on the MLB’s All Stars, the first of his “participatory journalism” forays for Sports Illustrated. That experience would eventually become the book Out of My League. Though this transcript does not name an interviewer, we can guess with confidence that it’s Plimpton.

In his account of entering the field, Plimpton observed that it is “unbelievably vast, startlingly green after the dark of the tunnel. In the looming stands the stark symmetry of empty seats … after the reverberating confines of the corridors, the great arena seemed quiet and hollow, and you felt you’d have to talk very distinctly to be heard.” I can’t be certain that Saul Steinberg ever set foot on the field at Yankee Stadium from the players’ tunnel, but his drawings of stadia evoke the same effect: bright oases situated in the muted hodge-podge and discord of the city.

Here Steinberg lays out for Plimpton (or whomever) what he has gleaned about nationhood through watching sports. Their conversation makes its way from whether American baseball is doomed to whether the eye grows weary of symmetry.

Some notes on the text presented here: At one point, the tape cut out, and that spot has been indicated in brackets. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity, but has otherwise been kept true to the original transcript.

INTERVIEWER

You were talking about baseball being a political game.

STEINBERG

Yes. Trying to figure out America, instinctively you look for the things that attract a great passion and seem incomprehensible to you on arriving in the States. There must be a secret. There must be a reason, a key to this passion. And the fact you don’t understand it means that it’s essential; you have to. I was brought up watching what’s called soccer here. It’s called football in Europe. And that was for me a very dear game. It looks very much like the primitive politics of a continental European country, and also like a continental primitive passion. What you have is a primitive situation of two groups trying to overpower each other and doing a direct damage that is physical: penetrating somebody’s goalpost.

INTERVIEWER

What do you see the ball as?

STEINBERG

The ball has to be touched with the foot. Now, the foot is the most brutal part of the body. The two extremities enter in this game. One is the head and one is the foot. None of them enter for what they are. The head enters only as the foot … because you hit the ball with the head. Sure, there are all sorts of strategies and abilities and gimmicks like dribbling and so on. But it’s a very primitive game of overpowering the opposition and screwing the other side. Get the ball past the goalkeeper inside, and that’s it. And there are all sorts of mechanical things going on, like foul: touching with the hands is taboo. You know that game. The main thing about it: there is a constant action and there isn’t one moment of meditation like in baseball.

Now, what struck me about baseball was that I couldn’t figure out how a big crowd of primitive, simple people would sit down on their seats and watch no action … I was saying, What’s going on here? This was no entertainment. What are they doing? But later on I figured it out and I understood that people who watch the so-called “no action” of baseball, actually they are making their own strategy. They impersonate the manager of the game; they impersonate the pitcher. They go through all the sweating and the emotions of the pitcher. They try to impersonate the confrontation of the man at bat and the man on the mound in the situation. And the situation can be very complex. One has to know the score; one has to know the personal lives of the players… If you read really the stories in the paper day by day you can find out how certain family situations can upset the pitcher, or how certain situations can become dramatic because of jealousy or interoffice fights between managers and owners and competition between clubs. Or the fact that a certain pitcher is high-strung at this moment; he’s lost so many games. He had made the almost no-hit game and something went wrong, so his luck is running out. He has cold hands, sweaty hands … and you feel it with him. These are human situations—the situations which are interesting for a novelist.

These psychological situations, in other words, were extremely interesting for me when I understood them. It took me a long time to study the game to understand it. So, it’s far removed from the simplicity of football, of soccer, where the action is constant and direct. And there are all sorts of things that are the equivalent of European politics where you have a fight between two groups, a military coup, a palace revolution. It seems to me that the game of soccer—the way it’s played in Europe, the way I saw it—was more like tribal war. I can see that if we in New York would fight New Jersey, we’d have the same sort of simple rules … to do as much damage as possible.

The game of baseball, it seems to me, is nearer to a philosophical game where you have to reach the moment where some sort of inspiration will make the pitcher pitch the ball, and he has to figure out the mathematical moment when the man at bat may be upset for a moment. It’s the coincidence of staring at each other. Now, this situation is very profound humanly: outstaring somebody that’s showing not the physical muscle of the leg or of the head, but the muscle of what’s called guts or balls. So it’s something beyond playing physical power and speed.

Saul Steinberg, Untitled, 1954, ink, watercolor, pencil, and crayon on paper, 22 3/4 x 29″. Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne, Paris; gift of The Saul Steinberg Foundation. © The Saul Steinberg Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.

INTERVIEWER

I have a theory about baseball which is rather different than yours. I can’t see it in terms of European politics. I think it’s a fascinating equation you make between the sport that a country plays and its politics. It always seems to me that baseball in this country is very much a nineteenth-century game. It deals with space, for example. It’s a non-martial sport. It’s not a martial art at all. Whereas, football is twentieth century. It’s mechanized. The only thing about baseball which reminds me of nineteenth-century America—not nineteenth-century Europe—is that it demands that an individual be faced with a particular problem. For example, a fly ball hit to center field. That man suddenly is the equivalent of the homesteader who has a problem to solve with no one to help him, with enormous space around him. It’s a puritan, early America, nineteenth-century space.

What really worries me about baseball … my favorite sport … I could go and watch baseball for days and days and never get tired of it. But I’m afraid we’re being told by the press in this country that it’s a dull sport, a boring sport, and that things are wrong with it. All the attempts to speed it up dismay me tremendously because part of the nineteenth-century aspect of the game is its solitude and its pace. It’s the only game I know of where the game can’t start until the pitcher throws something. There’s no other game that works that way. Most sports have a big clock where you know what’s going on. Football has a clock. Cricket is run by a clock. You stop at three o’clock for tea. Boxing—three minutes a round. Baseball … the pitcher can stand there forever, and he does not commit the game to the future until he winds up and throws something.

STEINBERG

And one has to win. In baseball one party has to win. You can’t have a draw. This is a nice idea. The city slickers are huddled together … and far away the good fellows from Nebraska in center field … [TAPE RAN OUT] I was saying the city slickers, the battery, the ward healers, tenderloins, the political hot-shots and the inner circle the way it is … the infield … guys like shortstops and first basemen and so on, together with the umpires who stay there, huddled to see something that represents the Supreme Court probably … the law that watches them … and far away in the wilderness, in the bushes, are the remote folks from Nebraska, from Vermont, from who knows where. But occasionally, they get the honor to catch a fly ball that shakes them from their sleep, from their dozing. But the reason for the slowness of the game and for the sleepy atmosphere … the whole field sometimes seems to have—the afternoon games especially in the summertime—there is something exotic about the thousands of people dozing, watching the game in order to, in the back of their minds, taste with more sweetness the true happiness of a homer, let’s say. When the wood hits the ball, everybody knows that’s a homer from the sound of it. Everybody perks up and wakes up with such vigor by contrast with the lethargy that had settled over the field. I would say there is no excitement if these would happen too often. You need this grayness for this flash to happen, to be more visible.

Saul Steinberg, Untitled, 1971–1972, charcoal and colored pencil on paper, 13 x 19 3/4″. The Saul Steinberg Foundation, New York. © The Saul Steinberg Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.

INTERVIEWER

Do you think that baseball is doomed as an American sport?

STEINBERG

I don’t know. I understand they make it now with artificial grass inside; also they play it mostly at night.

INTERVIEWER

But you love the night games.

STEINBERG

I love the night games, but then I saw it on television and it is just as good if you start watching on television. There is some sort of a complex feeling that you have now. If you watch something on television, like a color TV ballgame, when you see it in reality it starts looking like television. The idea of baseball itself is the afternoon game … summer game … which was the important thing for me I think when I saw it first. It’s disappearing. Matter of fact, on color TV it looks like a billiard game … because of the green rug—green table, and you see all these balls moving. Anyway, I can’t think of it as being real. I don’t want to see it. I read it in the paper now.

Saul Steinberg, Untitled, ca. 1980, pencil, crayon, and colored pencil on paper, 25 3/8 x 19″. The Saul Steinberg Foundation, New York. © The Saul Steinberg Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.

INTERVIEWER

Which neighborhoods do you particularly remember? Did you go to Chicago on your Milwaukee trip?

STEINBERG

Yes, we went to the Cubs field. They had a beautiful view of some sort of Chicago skyline. From high up you see one thing, then you go low down and you see something else. This was such a long time ago, I forgot. I haven’t been there since. But to get there it seems you always go to a part of town you’ve never been before and don’t dream of going. You get involved in strange parking lots, curious subterranean ways of getting in. Of course the public ballpark can be something interesting. When I go out at the intermission of a chamber music concert I always see all sorts of people that I know. It’s a cocktail party. I kiss dozens of wives, and so on. But I get panicky when I don’t know anybody. The same thing with baseball. You start seeing people you’ve never seen before. After all, we go to the movies and we stay in darkness. The only people we see are those comical characters lined up to buy tickets! Sometimes I pass them in review, without the slightest idea of going to the movies, just to look at them because they are like a museum of cast figures, costumed couples and so on. As they stay lined up and they can’t lose their line, you can watch them from very near without staying outside the rope of course, without any qualms. It’s an occasion for watching people the way one watches birds. So I sit in the movies generally and I don’t see anybody.

But in the ballpark you see people. You promenade, you watch … And the only time I had this occasion to be with strange people was during the war maybe, when I was in the company of lots of people. Not the people that I knew, but strange people from Montana to Arizona … from all sorts of places. So going to a ballgame is a great occasion for seeing a variety of people, and it’s not like the subway. The subway is something else. You are in a room with people, and there is something sad about them. It’s like people you meet in prisons or police stations, or waiting rooms of dentists. They’re not real people. In order to watch people you have to see them at liberty, and that’s the occasion of the baseball field.

Saul Steinberg, Baseball, from The Americans mural at the U.S. Pavilion, 1958 Brussels World’s Fair. Musées royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, Musée d’art moderne.

INTERVIEWER

Have you been to Shea Stadium and seen the Mets?

STEINBERG

No, I haven’t seen them at all this year. I went out in San Francisco to Candlestick Park a few years ago. It is beautiful, but it intimidates me when I see a baseball field that starts looking like a Howard Johnson … like a premeditated architecture. Basically, the beauty of the baseball field was the fact that it was caused by what’s called maidan in India. It’s the empty space in between houses. Maidan is used in the parade ground where the army is called to order. It’s an international word baksheesh. It works better in this language because it reflects more this emptiness … very casual with all sorts of weeds growing … where you improvise a game. This is how children play. The lot hasn’t been built yet. When this thing existed in the Bronx, or maybe a house has been demolished and there is some space to play. I imagine that the baseball field was caused by a real estate combination where irregular forms could be used for this sort of thing. This is why it was always an interesting architecture.

Ebbets Field was very peculiar. It was like a skyscraper inside. It was very high, as I remember. The Yankee Stadium was much more professional. It was made to look like a cathedral. It had elements of the Eiffel Tower and the decorations and so on. But the one in Philadelphia was tops. And the Milwaukee field was a new one, I think … Well, anyway, the way they have the grandstands and … what are they called? the places in the sun? … the bleachers. They add some bleachers, and they add something to it. It’s improvisation. It’s part of the American vernacular in architecture to build a thing like this.

INTERVIEWER

The new stadia that look like Howard Johnson motels disturb you?

STEINBERG

They make me uneasy. It’s sleek. It’s symmetric. The eye gets tired watching these things.

INTERVIEWER

Is the eye tired by symmetry?

STEINBERG

Yes. It gets bored, not tired.

INTERVIEWER

What are some other examples of that?

STEINBERG

Lincoln Center is one of the biggest horrors of the world. It springs out of the drafting table of the engineers and architects … who love nothing more than making symmetry. He makes a center, and then goes left and right doing the same thing … a repeat performance. That’s of course boring. On top of it, they add to the symmetry something cruel—these water pools—where the thing reflects itself again in symmetry. So you have double or triple symmetry, vertical and horizontal.

INTERVIEWER

You’ve always had a feeling for rococo and non-symmetry. Railway stations fascinate you?

STEINBERG

Railway stations are interesting. They’re built from improvisation … sheds. They curve sometimes, come this way and that way. The oldest railway stations, like Victoria Station or Saint-Lazare, well, the moment they became professional and symmetrical like the railway station in Milano, it was the sign of the decadence. This is always the law of human progress. When something becomes professional, it’s the beginning of the end.

Lauren Kane is a writer and an assistant editor for The Paris Review.

George Plimpton was founder of The Paris Review and its editor until his death in 2003.

Saul Steinberg, Untitled, 1954, ink, watercolor, crayon, and colored pencil on paper, 22 3/4 x 29″. Museum Ludwig, Cologne. © The Saul Steinberg Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.

November 3, 2021

The Paris Review Podcast, Episode 20

George Saunders photo by Chloe Aftel, courtesy of the author.

Season 3 of our acclaimed podcast continues today with the release of episode 20, “A Gift for Burning.”

We open with an excerpt from George Saunders’s Art of Fiction interview with Benjamin Nugent in which they discuss how Saunders’s teenage job delivering fast food prepared him to write fiction. Then poet Monica Youn reads her poem “Goldacre,” a disquisition on the Twinkie. Next, Molly McCully Brown reads her essay “If You Are Permanently Lost,” about spatial cognition and the power of not knowing where you are. We end with “Fam,” Venita Blackburn’s very short story about self-love and social media.

Listen now and subscribe at theparisreview.org/podcast or wherever you get your podcasts. New episodes will arrive every Wednesday in November. And don’t forget to catch up on Season 1 and Season 2.

The Paris Review Podcast is produced in partnership with Stitcher.

November 2, 2021

Games of Taste

Diego Delso, Interior of the Vasconcelos Library in Mexico City , 2015, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

A few years ago, I attended an academic conference where a prominent scholar of Latin American literature announced that he hated The Savage Detectives, a novel he considered overwritten and overrated. The statement provoked enthusiastic hooting from the back of the room, as if in glee at a taboo being broken. At the coffee break, I approached the critic and confessed I was a fan of the novel. Bolaño is a one-trick pony, he replied, and his trick is to parody and empty out the genres of Latin American literature—the dictator novel, the novela negra, the novel of testimony, and so on. This trick organized his writing at the level of the sentence, the chapter, and the novel. I said this sounded like an interesting trick, at least; he conceded that it was true Bolaño was a master at this exercise—but once you saw the trick there was nothing else, and hispanophone writers were no longer interested in his work. He claimed, happily, that the Latin American sales of Bolaño’s books were down. I asked him why he thought U.S. readers, who mostly lacked familiarity with these Latin American literary traditions, had embraced Bolaño. This, he told me, was the result of a clever marketing campaign: Bolaño’s big books had been released alongside new editions of Kerouac, and American readers were encouraged to understand the Chilean writer as a Southern Cone Beat. I expressed skepticism: Did anyone remember that marketing campaign? Was Kerouac selling well? My interlocutor was losing patience. Critics love Bolaño, he said, because they can pour whatever theory they please into his work. He told me Bolaño’s work was an excuse for American readers not to read any other Latin American literature. When you read The Savage Detectives you’re not enjoying yourself, he said, as much as you think you are.

There was a lot going on. I was struck by the high-handedness of these proclamations, but I wasn’t sure they were wrong. This uncertainty was partly just a matter of how artistic judgment works. Taste, precisely because it’s an intensely subjective matter we feel compelled to make others agree with, is awash in bad feeling. The buzzkill always has the advantage over the ardent fan, an advantage the literary theorist Gérard Genette called the “authority of the negative.” The question “How can you like this?” is, he noted, always more disturbing than “How can you dislike this?” The quickest way out of this bad feeling is to imitate your naysayer: surrender your taste, learn to despise, or to believe that you despise, what you had previously enjoyed. (More bad feeling, of a new variety, ensues.) In my case, the bad feeling was as much a matter of geopolitics as of aesthetics. My enjoyment of Bolaño wasn’t quite real, my new acquaintance said, and the part of it that felt real was a function of American ignorance.

The conversation didn’t end my pleasure in Bolaño, but it stayed with me. It crystallized something that was becoming visible in the academic and academy-adjacent social worlds I inhabit: Bolaño, and especially The Savage Detectives, had become shorthand for a certain brand of American cluelessness. In a 2018 essay in n+1, Nicolás Medina Mora, a Mexico City native living in the United States, reported on a trip home during which he sat in a café listening to an expat gringo couple discuss plans to rent a house on Oaxaca’s beach-lined coast. Medina Mora invents their backstory: they’re bien-pensant gentrifiers, the kind of people who insist on calling their Brooklyn neighborhood by the Spanish name used by the Puerto Ricans they’ve displaced. Soon it becomes clear that their enclave is being overrun by finance types, and they decide to push on to fresh frontiers. “They were getting tired of going to magazine parties and gallery galas where they disliked most of the people. And then one day he stumbled on his old copy of The Savage Detectives and found himself thinking: Why don’t we just move to Mexico City?”

Medina Mora doesn’t say Bolaño’s novel is bad. But he suggests that it’s peculiarly liable to being liked in bad ways. A lot of Bolaño skepticism turned on this fine distinction. In the academic world, a 2009 essay by Sarah Pollack, a specialist in Latin American literature, offered a carefully argued version of Medina Mora’s point. Pollack made it clear she considers Bolaño a writer of “genius,” but maintained that this was only one component in the runaway anglophone success of The Savage Detectives. Pollack claimed that Bolaño’s compelling biography—his youthful wanderings and poetic experimentation, his experience of Pinochet’s dictatorship, his death at fifty, just a few years after he began to achieve massive international recognition—had played a part in his renown. So had his press’s publicity campaign: Bolaño’s previously translated work had all been brought out by New Directions, the independent publisher with a pedigree in foreign and experimental fiction, but the contract for The Savage Detectives had gone to Farrar, Straus and Giroux, which had a bigger marketing budget. FSG decorated the novel’s jacket with a photo of Bolaño at twenty, long-haired and skinny and standing on what looks like a Mexico City rooftop. This picture, Pollack wrote, was “a nostalgic memento that for U.S. readers evokes the rebellious counterculture of the sixties and seventies,” and it facilitated the reception of the novel as escapist fantasy: “Thanks to Bolaño, U.S. readers can vicariously relive the best of the seventies, fascinated with the notion of a Latin America still latent with such possibilities.”

Pollack wasn’t wrong about the exoticism characterizing much of the anglophone reception of Bolaño. The worst offender may have been a New York Times piece on Between Parentheses, the 2011 English translation of Bolaño’s 2004 collection of essays and talks. The book showed Bolaño to have been a searching reader of a large swath of world literature (page through it and you’ll find discussions of Baudelaire, Borges, Highsmith, and the Goncourt brothers; Pepys, Perec, Piñera, and Walt Whitman). But the Times writer, a normally thoughtful Dwight Garner, sounded as if he were reviewing The Mark of Zorro: “The swashbuckling Bolaño could declaim and brawl at the same time,” he proclaimed. “He was a lover and a fighter.” Reading Between Parentheses, Garner averred, was “not like sitting through an air-conditioned seminar with the distinguished Señor Bolaño. It’s like sitting next to him, the jukebox playing dirty flamenco, after he’s consumed a platter of Pisco Sours. You may wish to make a batch yourself before you step onto the first page.” (The online version takes this last limp joke weirdly literally, offering a hyperlink to Epicurious’s recipe for the frothy beverage.) There is indeed an unbuttoned quality to Bolaño’s style, but it hardly demanded this cartoonish rhetoric. It was difficult not to feel that the pan-Latin whateverness of Garner’s review expressed a particular condescension to Spanish-language writing—hard to imagine the Times recommending Manischewitz to accompany your Roth, a wheel of brie with your Houellebecq.

Such patronizing praise could obviously tell nobody much of interest about Bolaño as a writer. But just for this reason, I was wary of letting the critique of the Bolaño phenomenon stand in for a reading of Bolaño—wary, that is, of letting an interpretation of this novelist’s work be captive to the stupidest things some Americans had said about it. As a fan, I of course had my own reasons not to want to see myself in Pollack’s and Medina Mora’s diagnoses. But beyond my own investments, there were questions to be asked about the logic of their arguments. As often in criticism that speculates about audience motivation, the interpretive claims didn’t always follow cleanly from the established facts: Who knows how many readers of The Savage Detectives bought the book because they saw the author photo? Who can say whether those readers wanted, as Pollack claimed, to “relive the best of the seventies” (whatever that was, and if they had lived through them the first time), and whether that fantasy took them through the novel’s 647 pages?

More striking still was the way these writers black-boxed their own assessment of Bolaño’s work while they attended to the reviews, blurbs, and promotional material that sold or distorted it. Even when they explicitly claimed admiration for his work, the arguments about Bolaño’s bad readers seemed to hint that the author himself was at fault. The suggestion was crystallized in Pollack’s “thanks to Bolaño,” with its ambiguous sense that the novelist had engineered the misreadings, or at least not armored his work against them. Soon I saw this slippery sense of causality everywhere. In 2015, the translator and critic Veronica Esposito reiterated the worry that Bolaño—a writer she loved—was loved by American readers for the wrong reasons. Bolaño’s major novels, Esposito wrote, “played off liberal American politics and curiosity about our Latin American neighbors”—a formulation suggesting that the books had been purpose-built to cater to Americans (in addition to intimating that curiosity about other parts of the world is blameworthy). Esposito’s verbs did a lot of quiet conflating, so that the work’s success was consistently described as the author’s plan: Bolaño didn’t just become a best-selling author but “was able to take advantage of and become a major commodity”; in a global market favoring books that could be translated with relative ease, “Bolaño turned such a style to his advantage”; in a literary field increasingly defined by well-publicized international prizes, “Bolaño both anticipated and profited from these developments.”

You don’t have to believe in the disinterested purity of the Artist to be struck by these critics’ faith in their demystifying logic: the suggestion is not just that most successful writers angle for success but that Bolaño’s big success was the result of his big skill as an angler. The picture that emerges is of a canny self-marketer. This logic—whereby suspicion of the work’s readers shades into disdain for the writer—reached its oddest moment in a 2009 essay entitled “Questions for Bolaño” by the eminent scholar of Latin American literature Jean Franco. The piece’s inquisitorial title was a rhetorical gesture: Bolaño, dead six years at the time of the essay’s publication, was evidently not going to be responding to these questions anytime soon. The essay is nonetheless incisive about the formal and political meaning of his work. Franco establishes the kinship of The Savage Detectives with formally jumpy, art- and politics-obsessed novels by Julio Cortázar and Roque Dalton; she is acute, and dubious, about what she calls Bolaño’s “romantic anarchist” politics—his preoccupation with friendship as the most meaningful unit of social and ethical life, the absence in his fictional worlds of explicit appeals to state reform, a fatalism that can feel apolitical. But the essay’s ambivalence goes beyond the usual scholarly skepticism; its insights are laced with animus. Near the opening, Franco describes Bolaño’s major novels as “two huge teasers”—a description she awards because of their failure to reach traditional closure (a peccadillo commonplace in most twentieth-century experimental fiction). She jokes that his prolificacy in life and the steady pace of posthumous publication make it reasonable to “suspect that Bolaño may not be a person but a company.” Finally, after noting that Bolaño is popular in a moment in which “Twitter replaces commentary,” Franco jumps to the startling claim that “Bolaño has turned illusion into a doctrine, twitter [sic] into life project.” Never mind that Bolaño died three years before Twitter’s debut. The retrocausal logic of Franco’s swipe makes this writer not only a wily PR genius, shilling his product from beyond the grave, but a posthumous devotee of one of the twenty-first century’s more toxic media inventions.

Other writers followed suit. There was a piece decrying the “Bolaño Myth,” another warning of the “Roberto Bolaño Bubble.” The latter, in The New Republic, regretted high-mindedly that when such a small percentage of books published in English is translated from other languages—3 percent is the commonly floated number, 0.7 percent if you just count literary fiction and poetry—Bolaño was taking up more than his fair share, especially with the posthumous publications: “We have enough,” the piece concluded. Worse, this writer claimed, Bolaño’s popularity had “hidden costs,” among them the risk that anglophone readers will think “that he is the only Latin American writer of importance to emerge” since García Márquez. A curious cultural protectionism suffused these responses, a concern with a volatile product getting into the wrong hands. A kind of novelistic vibranium, Bolaño’s work apparently had the ability to obliterate continents of literature. This notion that the way to counteract American ignorance about Latin American literature would be to curb American enthusiasm for a major Latin American author was peculiar. That the Bolaño craze might result in increased interest in hispanophone writers among English readers was rarely mentioned as a possibility. (But as some of these same writers would later concede, there is a case to be made that this is just what happened: a host of writers about whom Bolaño had said nice things in print—César Aira, Rodrigo Fresán, Alan Pauls, Carmen Boullosa, Juan Villoro, Sergio Pitol, Rodrigo Rey Rosa, Mario Bellatin, Andrés Neuman, Horacio Castellanos Moya—have arrived in English or seen the number of their books in English translation increase since his death, almost always with Bolaño’s stray comments used as jacket blurbs. And a host of writers too young for him to have read—Alejandro Zambra, Valeria Luiselli, Samanta Schweblin, Yuri Herrera, Juan Pablo Villalobos, Fernanda Melchor, Álvaro Enrigue, Guadalupe Nettel—have been published in English to widespread attention, in a wave of interest in Latin American literature that has been plausibly traced partly to Bolaño’s prominence.)

And yet the skepticism remains intriguing despite the factual shakiness of some of its predictions. The wariness with which these writers expressed their admiration, the careening quality of their disdain—now aimed at American readers, now at publishers, now at Bolaño—all of it bespoke a distress that wasn’t utterly clear about its origins or meaning. A few lines in Esposito’s essay hinted at the emotional and political energies swirling around this crisis of taste. Decrying the romanticizing coverage of Bolaño’s death, in particular the speculation that the liver disease that killed him was the result of a (probably apocryphal) heroin addiction, Esposito strikes a satirical pose: “The writer who boldly leaps where none have leapt before, who mixes passion and love together into art. This is the Bolaño we love to read… Our sweet hearts flutter at the thought of artists who ‘die too soon,’ and they absolutely purr for a man who lived a self-destructive life because he wanted to.”

Quite apart from the content of the claim, one notices the expression of self-contempt—parodistically expressed but vivid nonetheless. I was unpleasantly sensitive to these tones of self-blame: He did die too soon, I thought to myself. What’s wrong with saying so? I was pretty sure Esposito felt the same way, scare quotes notwithstanding. Whence this eagerness to ridicule fairly unremarkable sense of regret for the loss of a figure you admire? Why the desire to see literary appreciation under the most contemptible aspect? Rarely had the principle of de gustibus non est disputandum felt so disputable; rarely had the space for liking something felt so besieged by a worry over what that liking might say about you. If aesthetic judgment is particularly vulnerable to “games of influence” (Genette), the game here seemed to be operating according to rules nobody wanted to state openly. The sense you got was that it was embarrassing to be caught liking Bolaño, even if it was hard to say why.

And in truth, I could relate. It was embarrassing to be an American who liked Bolaño, and not just because in doing so one may have become a dupe of marketers or indulged in exoticizing projections. It was embarrassing because, for anyone remotely alert to the distribution of world power, being American is itself embarrassing. And being an American consumer of cultural products from abroad underlines that geopolitical shame with an intellectual one: impossible to disburden oneself of the phantom image of the Ugly American, trampling over local customs, missing cultural cues, expressing even in one’s appreciative curiosity (especially there) an offensive entitlement. Even thus overdrawn, the picture has its basis in fact. As important, it forms an inevitable, if infrequently remarked upon, psychic accompaniment to any act of mildly self-aware North American cross-cultural consumption: the American ignorance and arrogance exposed by the Bolaño skeptics was in no way surprising, as anyone who has participated in the competitive anti-Americanism among Americans abroad knows. For every asshole traipsing through Mexico City brandishing The Savage Detectives, there was someone else who knew enough to bury his copy deep in his luggage and, if asked, to pretend never to have heard of it.

David Kurnick is associate professor of English at Rutgers University at New Brunswick. He is the author of Empty Houses: Theatrical Failure and the Novel (2012). His writing has appeared in the Village Voice, Public Books, and the Chronicle of Higher Education, and his translations from Spanish include Julio Cortázar’s Fantomas Versus the Multinational Vampires (2014) and work by Álvaro Enrigue. The Savage Detectives Reread will be published on February 1, 2022.

Excerpted from The Savage Detectives Reread by David Kurnick. Copyright (c) 2021 Columbia University Press. Used by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.

Redux: Weird Ghost

Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

COURTESY ROLLIE MCKENNA COLLECTION.

This week at The Paris Review, we’re telling scary stories. Read on for James Merrill’s Art of Poetry interview, Joy Williams’s short story “Tricks,” William Faulkner’s ghost story “The Werewolf,” and Bhanu Kapil’s poem “Three Ghost Stories: 1944–48,” paired with photos from Flavia Gandolfo’s portfolio “Masks.”

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, and poems, why not subscribe to The Paris Review? You’ll also get four new issues of the quarterly delivered straight to your door.

Interview

James Merrill, The Art of Poetry No. 31

Issue no. 84 (Summer 1982)

INTERVIEWER

The Ouija board, now. I gather you use a homemade one, but that doesn’t exactly help me to imagine it or its workings. An overturned teacup is your pointer?

MERRILL

Yes. The commercial boards come with a funny see-through planchette on legs. I find them too cramped. Besides, it’s so easy to make your own—just write out the alphabet, and the numbers, and your yes and no (punctuation marks too, if you’re going all out) on a big sheet of cardboard. Or use brown paper—it travels better. On our Grand Tour, whenever we felt lonely in the hotel room, David and I could just unfold our instant company. He puts his right hand lightly on the cup, I put my left, leaving the right free to transcribe, and away we go. We get, oh, five hundred to six hundred words an hour. Better than gasoline.

Fiction

Tricks

By Joy Williams

Issue no. 90 (Winter 1983)

Liberty had never cared for Halloween. The night gave the false hope that when one was summoned to the door by a stranger’s knock, one’s most horrible fears could be realized by the appearance of ghosts, bats, ambulatory corpses, and the headless hounds of hell.

Fiction

The Werewolf

By William Faulkner

Issue no. 79 (Spring 1981)

The young man looked around outside the deserted station, hoping to find an attendant. No one was in sight. From the high ridge on which the station was built, he looked down into the shrouded valley and wondered at its darkness—why, even so late in the night, there should not be a single light gleaming through the fog from a single cottage. Suddenly at his feet a pattern of light fell. A lamp had been lit by unseen hands. Someone was inside the station.

Poetry

Three Ghost Stories: 1944–48

By Bhanu Kapil

Issue no. 228 (Spring 2019)

Mum nudged me and whispered, Go home. But I couldn’t move. The orange was stuffed with blood clots. My daughter has not eaten for a year and a half, said the girl’s mother. We left as quickly as we could. On the way home, we stopped at the old woman’s house. Tonight is the deciding factor, said the old woman. The girl is possessed by a ghost. A very famous person is coming to give a treatment. It’s a weird ghost. Many people from different religions have tried to get the ghost out but all have failed. Once, a Sikh gentleman came. He traveled from Lucknow and after some prayers he hung pictures of Guru Gobind Singh and Guru Nanak above the girl’s bed. Then he took out a big sword and hung that up, too. However, the pictures swung from side to side, so did the sword, and fell on the floor. Tonight at 2 A.M. a new man will start his treatment. Come with me. We will go and look.

Art

Masks

By Flavia Gandolfo

Issue no. 133 (Winter 1994)

If you enjoyed the above, don’t forget to subscribe! In addition to four print issues per year, you’ll also receive complete digital access to our sixty-eight years’ worth of archives.

October 29, 2021

The Review’s Review: Organic Video

Shigeko Kubota’s Berlin Diary: Thanks to My Ancestors. 1981. Cathode-ray tube monitor, crystal, ink, and twine. 9 × 8 × 11″ (22.9 × 20.3 × 27.9 cm).

“Everything is video,” the Japanese-born, New York–based artist Shigeko Kubota remarked in a 1975 interview. “[We] eat video, shit video, so I make video poems… Part of my day, everyday, the memory—I like to put in video.”

Overlooked compared to some of her other Fluxus-associated peers (including her husband, the pioneering video artist Nam June Paik), Kubota’s work is now the subject of a small but brilliant exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, Liquid Reality, which spans her artistically fertile period from 1976 to 1985. In Kubota’s hands, video abandons its cold, sleek pretense, instead taking on a wild quality, with inverted color schemes and pulsating time warps akin to an overgrown garden. “Film was chemical, but video was more organic,” she told The Brooklyn Rail in 2007, eight years before her death at the age of seventy-seven. In her work, mountains stand tall, water seeps, and, in 1979’s River, a literal stream babbles over three neon-colored monitors, like some magic rivulet snatched from an old mythology and transported to our technological age.

[image error]Video Haiku–Hanging Piece (1981). Cathode-ray tube monitor, closed-circuit video camera, mirror, and plywood. Overall dimensions variable, mirror: 40 × 42″ (101.6 × 106.7 cm).

[image error]Duchampiana: Nude Descending a Staircase (1976). Standard-definition video and Super 8 mm film transferred to video (color, silent; 5:21 min.), four cathode-ray tube monitors, and plywood. 66 1/4 × 30 15/16 × 67″ (168.3 × 78.6 × 170.2 cm).

On a late afternoon in early October, a crowd filmed Kubota’s videos, and water from Niagara Falls I (1985) splashed. The people’s murmurs were like the whirring sound of a tape spinning backward. The room grew cool and dark. Suddenly, a small shriek, and a beleaguered MoMA employee ran over to one of the three open-top pyramids comprising 1976’s installation piece Three Mountains. A couple stood near the lip of one of them, peering in. There, inside the column, amid mirrors and monitors reflecting endlessly, lay another type of screen: while taking a video, one of the couple had by accident dropped their phone. —Rhian Sasseen

Inside of Three Mountains. 1976–79. Four-channel standard-definition video (color, sound; approx. 30 min. each), seven cathode-ray tube monitors, plywood, and mirrors, overall dimensions variable.

* * *

A while ago, I was surprised to hear myself describe the reading of John le Carré as a guilty pleasure. I suppose I was trying to elevate my bookshelf in some way—trying to suggest that I occasionally wolf down some genre stuff in between Gravity’s Rainbow and Finnegans Wake. In any case, it was ungracious nonsense. The further I get into middle age, the more I lean toward hospitable books and the more I distrust the assertion that this hospitality is evidence of some sort of authorial limitation or lack of literary ambition. As Ian McEwan stated, le Carré is not simply a spy writer, “he’s in the first rank.”

All of which to say, I have le Carré’s final book, Silverview, sitting on my nightstand, waiting for me when I get home. How wonderful and how reassuring to be welcomed into the dusty, bureaucratic world of le Carré’s espionage one last time. —Robin Jones

I recently asked an old friend to send some music they’d been listening to as a lazy way of staying connected. They sent back Leona Anderson’s 1957 album Music to Suffer By, which has exactly the anti-sonorous quality you’d expect from a silent film actress; the song “Summertime Blues” by the Flying Lizards; and Miharu Koshi’s 1983 album Tutu, which is lightly industrial at heart and rich synth on top, and has me head over heels. —Lauren Kane

Cooking with Mary Shelley

Photo: Erica Maclean

This year, I suggest a sad and lovelorn Halloween, tender and tolerant of monsters. The book for the mood is the 1816 novel Frankenstein, by Mary Shelley (1797–1851), a classic of gothic literature whose pages inspired foraged-fare acorn scones, a cocktail, and a bread pudding—not weird science, but foods of love.

Readers, critics, and biographers have long sought the key to Frankenstein in Mary Shelley’s life, which had all the tragedy and plot twists of a good gothic novel. Shelley was the daughter of Mary Wollstonecraft, author of the early feminist text A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, and William Godwin, a radical political writer as famous as Wollstonecraft in his time. When Mary was sixteen, she fell for a young poet on the make, Percy Bysshe Shelley, and ran off to France with him, along with her fifteen-year-old stepsister, Claire Clairmont, who also later had a sexual relationship with Shelley. The ménage ran out of money and returned to England, but stayed together, perennially short of cash and living according to the principles of free love. Their conduct ostracized Godwin despite his radical reputation, and most of Mary’s circle of friends.

Frankenstein asks “Who shall conceive the horrors of my secret toil, as I dabbled among the unhallowed damps of the grave?” Making scones was much more pleasant.

Mary began work on Frankenstein a few years later, when she was still in her teens, on another trip to Europe. One fateful rainy afternoon, a group that included Mary, Percy, and Lord Byron dared each other to write scary stories. The others never followed through, but Mary’s story would become perhaps the most famous result of a parlor game ever produced. The book is composed in nested points of view, letters and stories within stories, a structure that was popular at the time and is particularly elegant for Frankenstein because the layers make the wild contents feel more plausible. It follows the conventions of gothic literature, exploring themes of fear, exile, and loneliness, and begins in a frozen wasteland, with letters from a young sea captain describing a perilous mission to the far north. There, the sea captain meets Victor Frankenstein, once a promising young scientist, whose “heart overflowed with kindness and the love of virtue” but who had “committed deeds of mischief beyond description horrible, and much, much more.”

Frankenstein’s crime was to have stitched together a giant man from the parts of other men and endowed it with life. When the ecstasy of conception is over, he is horrified by his creation, which has a “dull yellow eye” and a “shriveled complexion,” and moves with “convulsive motion.” He flees from it, but the creature eventually pursues him, and murders, one by one, his family members and loved ones. In the morality of the book, the retribution is partially a condemnation of scientific overreach, but is more a consequence of Victor Frankenstein’s lack of appreciation of what it means to be a human being. When the monster confronts Victor and reveals its point of view, we learn that it felt itself to be “a poor, helpless, miserable wretch” and that it longed for companionship. In this context, Victor’s abandonment of it upon its birth was cruel.

There is nothing cruel about bread, cream, onions, herbs, and cheese. Recipe from A Gothic Cookbook, by Ella Buchan and Alessandra Pino.

The monster demands that Victor make it a female companion—and promises that if he does so, it will do no further harm. Its words are moving:

If you consent, neither you nor any other human being shall ever see us again. I will go to the vast wilds of South America. My food is not that of man; I do not destroy the lamb and the kid, to glut my appetite; acorns and berries afford me sufficient nourishment. My companion will be of the same nature as myself, and will be content with the same fare. We shall make our bed of dried leaves.

Victor fails to honor this romantic request, and brings about his own downfall. One lesson of Frankenstein is that what matters in life is not our accomplishments but how we treat each other, which must have had special resonance for the author, given her personal circumstance of love and exile. The stitched-up green corpse, in this reading, becomes an object of tenderness, a person we should all do better by.

A page from A Gothic Cookbook, with acorns collected for me by my mother and illustrations by Lee Henry. The cookbook will include a recipe on how to make acorn flour.

I was inspired to write about Frankenstein when I came across A Gothic Cookbook, by Ella Buchan and Alessandra Pino, a project currently in the funding stage from the London-based publishing company Unbound. Buchan and Pino were able to share the introduction to their chapter on Frankenstein and several of their recipes, which reflected the creature’s choice to sustain itself on found and foraged vegetarian foods. Percy Shelly was a vegetarian, as was Lord Byron, and the creature’s vegetarianism, they write, “becomes a symbol of his inherent goodness.” They made an acorn bread inspired by the creature’s diet of acorns, and a bread pudding made up of the components of a shepherd’s breakfast that the creature eats after it has unfortunately scared the breakfast’s owner away. They also shared a recipe for a green-hued Corpse Reviver 1818 cocktail from a drinks supplement to the cookbook, which is available to certain pledge levels.

I planned to make the bread pudding, which sounded easy and delicious, and the cocktail, which miraculously asked only for alcohols I already had on hand. I also wanted to include a dish made from items I could forage myself, and settled on apple scones made with acorn flour (both are in season). If Victor Frankenstein had been merciful and created a wife for the monster, the wife would have been in luck, because these foods were amazing. The Corpse Reviver 1818 is made with gin, Chartreuse, vermouth, lemon juice, and a few drops of absinthe—appropriately green and strange for Halloween. The bread pudding was rich, herby, and crispy, and served as evidence that nothing can possibly go wrong with bread, onions, cheese, and cream. My foraged scones tasted like gingerbread, and showed that a diet that does no harm can also be highly rewarding.

One night, while foraging for food like these acorns, the monster also finds an abandoned portmanteau containing “Paradise Lost, a volume of Plutarch’s Lives, and The Sorrows of Werther.” Naturally, it devours them. Photo: Erica Maclean.

The first two dishes were easy, but the scones were more of a process. One challenge in making them was to incorporate apples, the seasonal wild ingredient available to me, in a way that wouldn’t make the final product too wet. I foraged super-ripe, spotty little red apples from a tree on my property in Vermont, then sliced them and dried them out in a two-hundred-degree oven for two hours, which made them surprisingly sweet and cutely miniature, as well as dry enough not to impact the scone texture. The second challenge was to make the acorn flour, a process that in truth I didn’t quite finish it in time, so I’ve used flour ordered online for the photos seen here. The scones with the store-bought acorn flour were toothsomely dry and pillowy, with tangy pops of flavor from the apples. I’ve since made the acorn flour at home, though I haven’t baked with it, and it was ridiculously time intensive but fun. I wouldn’t venture to offer a recipe, but I did learn how to crack acorns (a lot of bashing in a mortar and pestle); how to remove the toxic inner skin of acorns (freeze for twenty-four hours, then thaw, and it’s still not easy); and how to leach out the tannins from acorns (grind and then soak; mine took twenty-four hours). A fresh-cracked acorn is powerfully redolent of oak and is something everyone should smell at least once in their lives. The fully processed acorn flour is mild and little bit magical, with the faintest hint of vanilla and dried leaves.

It was not lost on me that to make these dishes required time, modern technology, and access to ingredients not found in the wild—mostly things the creature did not have, but which I had access to as a benefit of our shared human society. If the book’s message was to emphasize the value of that, it’s a good reminder for any holiday, including Halloween.

Photo: Erica Maclean

Corpse Reviver 1818

Makes one cocktail. Adapted from A Gothic Cookbook’s vintage-style cocktail booklet, available as a crowdfunding pledge level: https://unbound.com/books/a-gothic-cookbook/levels/12092/

Ingredients

1 oz dry gin

1 oz Lillet Blanc (you can also use white vermouth, though it will be drier/less sweet)

1 oz Chartreuse

A few drops of absinthe

1 tbsp of lemon juice

Lemon twist, to serve

Method

Fill a cocktail shaker with ice and add the spirits (you only need a little dribble of absinthe). Add the lemon and shake well. Strain into a chilled coupe or martini glass. Add a lemon twist, and enjoy!

Photo: Erica Maclean

Photo: Erica Maclean

Apple-Acorn Scones

6 small, sweet foraged apples

1 cup acorn flour (store-bought)

3/4 cup white flour

1 tbsp baking powder

6 tbsp sugar, divided

1/2 tsp salt

8 tbsp cold butter, diced

1/4 cup plus 1 tbsp buttermilk

1 egg

2 tsp ground cinnamon, divided

Make the dried apples. Preheat the oven to 200. Line a large baking sheet with parchment paper. Slice the apples as thinly as possible, place them in a single layer on the baking sheet, and bake until shrunken and dry, about two hours. Let cool.

Increase the oven temperature to 375. Mix together the acorn flour, white flour, baking powder, 3 tbsp of the sugar, and salt in a medium mixing bowl. Add the cold butter, and cut in with a pastry blender until the mixture is mostly combined and any remaining chunks of butter are smaller than pea-size. Make a well in the center, and add the egg and the buttermilk. Whip with a fork to combine, and then start pulling in the flour mixture, stirring until the entire mass is moistened. Use your hands to crunch the dough together until it is homogenous and forms a single ball.

Flour a work surface and roll the dough out to an 8 x 10″ rectangle. Sprinkle half of the rectangle with 1 tbsp of the remaining sugar, 1 tsp of cinnamon, and 1/4 cup of dried apples. Fold the dough in half, roll out again, and repeat the process with another 1 tbsp of sugar, the remaining 1 tsp of cinnamon, and another 1/4 cup dried apples. Fold again, but do not roll out.

Using your hands, crunch the folded dough into a roughly circular shape, scatter with dried apples, dust with the remaining 1 tbsp of sugar, and press lightly with your fingers to make the apples adhere. Place the dough on a baking sheet, cut it into six wedges, and pull the wedges apart a little so they don’t stick together when they cook. Bake for seventeen minutes, until puffy and cooked through.

Shepherd’s Breakfast Bread Pudding

Adapted from A Gothic Cookbook, by Ella Buchan and Alessandra Pino.

Ingredients

2 red onions, finely sliced

1 tbsp olive oil

3 tbsp balsamic vinegar

1 tbsp granulated sugar

1/3 cup of red wine

1 medium loaf of day-old or slightly stale bread, sliced

4 tbsp unsalted butter, softened

2 tbsp chopped fresh herbs (thyme, parsley, and rosemary work beautifully)

100g hard cheese, grated (we used 50/50 cheddar and Gruyère)

1 cup whole milk

2 eggs

1 cup heavy cream

1 tsp Dijon mustard

3/4 tsp salt

Pepper to taste

Make the caramelized onions. Heat the olive oil over a medium heat, add onions, and sauté for a few minutes, or until soft. Add vinegar, sugar, and wine, increase heat and cook until the liquid has evaporated and the onions are sticky. Season with salt and pepper.

Beat the softened butter with the herbs and a pinch of salt. Spread this mixture over each slice of bread, then quarter each one into triangles.

Preheat oven to 350 and grease a large baking dish. Arrange a layer of bread on the bottom, top with a layer of onions, and sprinkle with cheese. Repeat the layers until the ingredients are used up, ending with cheese.

Whisk together the milk, eggs, cream, mustard, 3/4 tsp salt, and pepper to taste. Pour over the bread, pushing down so it soaks up the liquid. Rest for five minutes then bake for 25-30 minutes, until puffy and lightly golden.

Valerie Stivers is a writer based in New York. Read earlier installments of Eat Your Words.

October 28, 2021

Skinning a Cat: On Writer’s Block

Yesterday, we launched Season 3 of our podcast, with an episode that includes Yohanca Delgado reading her story “The Little Widow from the Capital.” To mark the occasion, we asked Delgado what allows her to begin writing again when nothing else has worked:

When I struggle to write, I shrink my expectations: two words a day. No more, no less. The part of my brain that seeks narrative shyly re-emerges. Maybe day one is easy: a first and last name. But even as I close my laptop, I don’t want to stop there. Beatriz Ortiz wants something. And word by word, the exposed brick wall in Beatriz’s office emerges, the smell of the tangerine she’s peeling…

It becomes an Oulipian exercise, a game of Pass the Story. In A Swim in the Pond in the Rain, George Saunders describes the construction of a story as a gradual process, in which different versions of the writer slowly build the best possible draft through small revisions. The version of me who has just watched Viy has access to a different set of narrative links than the version of me who has just re-read a story from Christine Schutt’s Pure Hollywood or Nafissa Thompson-Spires’s Heads of the Colored People, or who has just spent an hour googling “is shrink-wrap recyclable.” Each day, a version of myself floats a decision about where the story might go, and I relearn that by putting one word in front of another, I can make my way to places I’ve never been before.

Yohanca Delgado’s notebook, showing a from Aracelis Girmay’s “The Black Maria.”

The episode also features conversations from The Paris Review’s Art of Poetry interviews with Antonella Anedda and Robert Frost, and it occurred to us that writers might seek counsel there as well.

ANTONELLA ANEDDA

I follow a sound or an image and then I jot down the words in a notebook or in the back of a book. I can and must write everywhere. I have a husband, a very old father, a very old aunt, a daughter. What I’m trying to say is that I cannot have “rituals” as I write. I work hard, as anyone must, but I take advantage of every time and place. I am at home in every moment of calm. I write, I read, I rewrite, I read again, I correct, I put up with my desperation, get through my desperation, get over my desperation. This all takes some time before moving on to the computer. I build up my courage, reread, make corrections. When I am exhausted, I deliver the poem.

ROBERT FROST

Very first [poem] I wrote I was walking home from school and I began to make it—a March day—and I was making it all afternoon and making it so I was late at my grandmother’s for dinner. I finished it, but it burned right up, just burned right up, you know. And what started that? What burned it? So many talk, I wonder how falsely, about what it costs them, what agony it is to write. I’ve often been quoted: “No tears in the writer, no tears in the reader. No surprise for the writer, no surprise for the reader.” But another distinction I made is: however sad, no grievance, grief without grievance. How could I, how could anyone have a good time with what cost me too much agony, how could they? What do I want to communicate but what a hell of a good time I had writing it? The whole thing is performance and prowess and feats of association.

What it is that guides us—what is it? Young people wonder about that, don’t they? But I tell them it’s just the same as when you feel a joke coming. You see somebody coming down the street that you’re accustomed to abuse, and you feel it rising in you, something to say as you pass each other. Coming over him the same way. And where do these thoughts come from? Where does a thought? Something does it to you. It’s him coming toward you that gives you the animus, you know. When they want to know about inspiration, I tell them it’s mostly animus.

Listen now at theparisreview.org/podcast or wherever you get your podcasts. New episodes will arrive every Wednesday in November. And don’t forget to catch up on Season 1 and Season 2.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers