The Paris Review's Blog, page 95

November 30, 2021

The Fourth Rhyme: On Stephen Sondheim

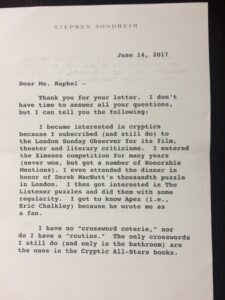

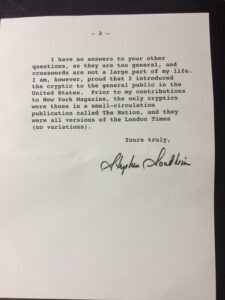

a letter to the author from Stephen Sondheim.

In the late fifties, Stephen Sondheim, who died last week aged ninety-one, performed a song from the not-yet-finished musical Gypsy for Cole Porter, on the piano at the older composer’s apartment. As Sondheim recalls in Finishing the Hat, his mesmerizing and microscopically annotated first collection of lyrics, Porter had recently had both legs amputated, and Ethel Merman, the star of Gypsy—in which Sondheim’s words accompanied music by Jule Styne—had brought the young lyricist along as part of an entourage to cheer him up. Sondheim played the clever trio “Together.” “It may well have been the high point of my lyric-writing life,” he writes, to witness Porter’s “gasp of delight” on hearing a surprise fourth rhyme in a foreign language: “Wherever I go, I know he goes / Wherever I go, I know she goes / No fits, no fights, no feuds, and no egos / Amigos / Together!”

That fourth rhyme–it astonishes every single time–exemplifies everything I revere in Sondheim. He is, of course, a musical-theater god: from West Side Story through Company, Follies, Sunday in the Park with George, and Assassins, his influence trounces superlatives. Even his flops were often revelatory. Merrily We Roll Along proceeds backwards, anticipating by decades the experiments with time in shows like Jason Robert Brown’s The Last Five Years; The Frogs, a reimagining of Aristophanes first performed in Yale University’s swimming pool, must surely have been among the inspirations for Mary Zimmerman’s water-based stage adaptation of Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

Wordplay is never just a pyrotechnic aftereffect in Sondheim’s shows—it’s foundational, crucial to the plot and the characters’ emotional development. And his work continually reminds you that playfulness (in poetry, in music, in lyrics, in visual art) can be most essential when the subject is deadly serious. Sondheim includes a multiple-choice quiz in a love song—“Now/Later/Soon” from A Little Night Music: “(A) I could ravish her / (B) I could nap”—and likewise in a paean to the uses of a gun, sung from the rotating points of view of the actual and would-be assassins of U.S. presidents: “Remove a scoundrel / Unite a party / Preserve the Union / Promote the sales of my book.”

The Sondheim lyrics I love are too abundant to list, but there’s one in his fairytale extravaganza Into the Woods that gets my personal gasp of delight. In the prologue to that show, Sondheim introduces the lyrical and musical motifs of each of the main characters. Full disclosure: I played Rapunzel in my high school’s production; don’t ask me to attempt her high B-flats anymore. Jack’s mother, trying to coax milk from their aging cow, Milky-White, grumbles to Jack that “We’ve no time to sit and dither / While her withers wither with her.” That triple homonym—”withers wither with her”—delights the ear, develops the mother’s character, and moves the plot forward, all at once. (Sondheim’s repetitions are always ingenious: “Then you career from career to career,” he writes in “I’m Still Here,” Carlotta’s torch song from Follies, which my grandmother memorably rewrote to celebrate leaving her job as a middle-school principal—rather an awkward choice for one’s own retirement party, perhaps, but I like to think Sondheim would have understood.) When Jack goes to market and trades the cow, whose meager supply of milk will no longer support them, “for beans”—an idiom that usually means “for nothing”—his mother, a literalist, gets furious again. Jack tells her that these are magic beans, worth far more than their beast, which it turns out they are.

The high point of my own writing life was receiving a typewritten note from Stephen Sondheim. My weakness for that fourth-rhyme effect may be what first drew me to crossword puzzles, so it didn’t surprise me to find out that Sondheim liked them too, but while researching a book on the subject, I learned that he was also a brilliant composer of the cryptic crossword. Crossword lovers tend to remember their first eureka moment with a puzzle: that time they got stumped on a clue, only to realize they’d been seeing it the wrong way. “Strips in a club?” for example, indicates not dancing on a stage but BACON in a sandwich.

Unlike those in American-style crosswords, cryptic clues involve an extra layer of wordplay. In 1968, Sondheim began publishing cryptic crosswords in New York magazine, and wrote about them with reverence: “A good clue can give you all the pleasures of being duped that a mystery story can. It has surface innocence, surprise, the revelation of a concealed meaning, and the catharsis of solution.” He scorned the simpler American variety with equal relish: “The kind familiar to most New Yorkers is a mechanical test of tirelessly esoteric knowledge: ‘Brazilian potter’s wheel,’ ‘East Indian betel nut’ and the like are typical definitions, sending you either to Webster’s New International or to sleep.” I wrote to Sondheim’s agent, asking far too many questions; I edited and re-edited my letter and, after mailing it, spent the night in a cold sweat that I’d used the wrong grammatical tense. When Sondheim, to my astonishment, wrote back, he said that although he no longer had a regular solving practice, he counted introducing American readers to cryptic crosswords among the great achievements of his life. He’d given them a source of delight, a new way of seeing the world.

Crosswords initially appealed to me as a diversion, and I got hooked on them through that gasp of delight, but eventually I realized that they have special resonance in times of crisis. The crossword was invented in 1913, on the eve of World War I, when people craved something comforting in the newspaper. The New York Times first published its crossword during World War II, just after Pearl Harbor, to offer readers a distraction from the bleak headlines. Crosswords also leaped in popularity during the pandemic—I wrote two for The Paris Review in spring 2020—and not only because so many of us needed something to do in isolation. Crosswords provide an experience of immersion, yet they don’t completely shut out the world around you. Wordplay, whether in the best puzzles or in Sondheim musicals, can estrange your surroundings and the language through which you interpret them, allowing your life to catch you by surprise again.

Adrienne Raphel is the author of Thinking Inside the Box: Adventures With Crosswords and the Puzzling People Who Can’t Live Without Them, What Was It For, and the forthcoming book of poetry Our Dark Academia.

Redux: Each Train Rips

Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

Jan Morris © David Hurn.

This week at The Paris Review, we’re traveling via plane, bus, and foot. Read on for Jan Morris’s Art of the Essay interview, Anuk Arudpragasam’s short story “So Many Different Worlds,” Sarah Green’s poem “Vortex, Amtrak,” W. S. Merwin’s essay “Flight Home,” and a portfolio of art by Paige Jiyoung Moon.

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, and poems, why not subscribe to The Paris Review? You’ll get four new issues of the quarterly delivered straight to your door.

Interview

Jan Morris, The Art of the Essay No. 2

Issue no. 143 (Summer 1997)

I’m not the sort of writer who tries to tell other people what they are going to get out of the city. I don’t consider my books travel books. I don’t like travel books, as I said before. I don’t believe in them as a genre of literature. Every city I describe is really only a description of me looking at the city or responding to it.

ZION AND US (DETAIL), 2019, ACRYLIC ON PANEL, 11 X 14″.

Fiction

So Many Different Worlds

By Anuk Arudpragasam

Issue no. 237 (Summer 2021)

The bus was making its way in starts and stops, accelerating and braking as the driver tried, ruthlessly, to overtake on the crowded roads, and Ganesan was gazing out through the half-open window, at pedestrians waiting impatiently at traffic lights and bus stops, at passengers in other vehicles staring silently into their phones or out at the monotonous evening. The light hadn’t yet begun to fade but the day was coming to its end, the city’s commuters all lost in the long, mindless journey from place of work to place of sleep, their last remaining obligation to the outside world.

SUBWAY 2015, 2015, ACRYLIC ON CANVAS, 11 X 14″.

Poetry

Vortex, Amtrak

By Sarah Green

Issue no. 231 (Winter 2019)

Bright scab of track.

Bright stitch each train

rips out. In negative

degrees, metal cowers

as if a god had threatened

to curse it,

and did.

OAKHURST LODGE, 2018, ACRYLIC ON CANVAS, 12 X 16″.

Nonfiction

Flight Home

By W. S. Merwin

Issue no. 17 (Autumn-Winter 1957)

Part of the confusion, once the desire to go back got off the chart, arose from the suspicion that this was simply, at least in part, the first shock of maturity: a realization that home, where you grew up and belonged—belonged with and without your own volition—no longer exists. The desire to return to it, the moment you know it no longer exists.

LONELY PADDLE BOARDER, 2020, ACRYLIC ON PANEL, 18 X 24″.

Art

New and Recent Work

By Paige Jiyoung Moon, with an introduction by Charlotte Strick

Issue no. 236 (Spring 2021)

If you enjoyed the above, don’t forget to subscribe! In addition to four print issues per year, you’ll also receive complete digital access to our sixty-eight years’ worth of archives.

November 29, 2021

White Gods

Jose Chávez Morado mosaic mural El Retorno de Quetzalcóatl, Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico of Mexico City. Photo by Eva Leticia Ortiz.

“We were superior to the god who had created us,” Adam recalled not long before he died, age seven hundred. According to The Apocalypse of Adam, a Coptic text from the late first century CE, discovered in Upper Egypt in 1945, Adam told his son Seth that he and Eve had moved as a single magnificent being: “I went about with her in glory.” The fall was a plunge from unity into human difference. “God angrily divided us,” Adam recounted. “And after that we grew dim in our minds…” Paradise was a lost sense of self, and it was also a place that would appear on maps, wistfully imagined by generations of Adam’s descendants. In the fifteenth century, European charts located Eden to the east, where the sun rises—an island ringed by a wall of fire. With the coordinates in their minds, Europe’s explorers could envisage a return to wholeness, to transcendence, to the godhood that had once belonged to man.

***

A fleet of ships appeared on the horizon, swarming the boundary between heaven and earth. After five weeks on the open sea, sailing in the wrong direction to reach the east, Christopher Columbus and his companions anchored off an unknown coast. Crowds of curious islanders gathered on the shore. “They threw themselves into the sea swimming and came to us,” Columbus wrote in his diary on October 14, 1492. “We understood that they asked us if we had come from heaven,” he claimed, although he did not know a word of their language. A week later, disembarking on an island so densely flocked by parrots that they concealed the sun, Columbus reported he was again hailed as a deity by natives who “held our arrival to be a great marvel,” wearing gold nose rings that he found disappointingly small.

Every time he stepped off the ship’s rowboat and onto the soft sand, exploring places later known as Cuba, Haiti, and the Bahamas, Columbus seemed to walk on the clouds. On December 13, he wrote that a chieftain had informed a crowd of two thousand fearful, trembling kinsmen that “the Christians were from heaven.” The people put their hands on their heads, in “a sign of great reverence,” and made offerings of yams and fish. Approached by an envoy of hundreds of islanders several days later, Columbus again recorded their belief in his celestial status, although he noted that the chief and his advisers “were very sorry that they could not understand me, nor I them. However,” he continued, “I knew that they said that, if I wanted anything, the whole island was at my disposal.” Conquest followed apotheosis: every island he found, filled with people allegedly mistaking him for divine, the mariner took possession of for Spain. He would read an indecipherable declaration, then pause for a refusal that could not occur. “No opposition was offered to me,” Columbus wrote.

***

In 1519, temples were sighted drifting off the coast of Xicalango. According to the Universal History of the Things of New Spain, also known as the Florentine Codex, a sixteenth-century text long held to be an authoritative account of the Spanish conquest, the emperor Moctezuma sent messengers in canoes to greet a fleet of Spanish ships: “They thought it was the god Quetzalcoatl who was returning.” This deity, whose name means “feathered serpent,” was said to have created the earth in an act of discovery: Quetzalcoatl had lifted up the sky and revealed the world beneath, then sailed east on a raft made of snakes, promising to return. When the emperor’s emissaries climbed aboard one of the ships and saw the stout commander Hernán Cortés, they fell to their knees and kissed the ground. “May the god, whom we come to worship in person, know from his servant Moctezuma, who rules and governs his city of Mexico for him, that he says the god has had a difficult journey,” they said. They dressed the weary Quetzalcoatl in the gifts they had brought: a turquoise serpent mask with a crown of parrot feathers, gold medallions and jaguar skins, a shield and scepter of precious stones, a breastplate of seashells and obsidian sandals. They laid out three more outfits before him. But when they had finished, Cortés asked, “Is this all you’ve brought?”

Within days, according to the history, recounted as always by the aggressors, Cortés had managed to bind Moctezuma in chains. Holding the emperor prisoner in his own home, the captain consolidated his rule over the fallen kingdom.

With each crossing of the sea, the pantheon grew: men who went in search of profit and found godhood. Thirteen years later, the conquistador Francisco Pizarro was reportedly mistaken by the Incas for their own vanished and bristly god. The sixteenth-century chronicler Juan de Betanzos wrote that a white, bearded deity was said to have risen from Lake Titicaca to create the earth, the sky, and mankind, then set off walking on the sea and disappeared. The navigator Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa noted that because the god moved over the water, they called him Viracocha, meaning “sea foam.” When Pizarro and his sailors landed on the beach, the people watching from afar assumed they had risen out of the sea. Messengers carried the news to the Incan king Atahualpa that Viracocha had returned. They described the Spaniards: white and bearded, mounted on improbably large sheep, able to kill from a distance. King Atahualpa, declaring himself “happy that in his age and time gods would come to his land,” invited Pizarro to his encampment deep in the mountains of Cajamarca, and was soon captured.

Much like Cortés and his men, Pizarro’s forces swiftly dispelled any illusions of godliness. Rather than creating springs and rivers wherever they went, they carried water in gourds; they raped women and peeled gold from the temple walls. Yet the conquistadors’ texts were widely read and so the stories lingered. Over the following century, nearly sixty million inhabitants of the New World would be killed—enough to cast a chill across the earth, as the forest crept back over once-inhabited lands, cooling the globe and blanketing Europe in snow. The altar of white divinity was the sand.

***

By their own account, Sir Francis Drake and his men, landing on the coast of northern California in the summer of 1579, tried hard to demonstrate their humanness to the tribe who rushed down from the hills to greet them, attired with bows, arrows, spears, and little else. Drake’s nephew, in The World Encompassed by Sir Francis Drake, based largely on the journals of the mission’s chaplain, Francis Fletcher, wrote that on seeing them the locals froze, “as men ravished in their minds.” The captain and his crew could not understand the Miwok language, yet Fletcher confidently recalled: “Nothing could persuade them, nor remove that opinion, which they had conceived of us, that we should be Gods.” The English gave the prelapsarian natives shirts and linen, advising them that “we were no Gods but men, and had need of such things to cover our own shame,” and they ate and drank heartily in their presence, but to no avail. The chieftain placed a crown upon Drake’s head, beseeching him to “become their king and patron: making signs that they would resign unto him their right and title in the whole land.” Despite his “Protestant scruples,” Drake felt he could not refuse: momentary godhood was a trial he would have to bear, a necessary misstep in the transfer of their affections from the wrong Almighty to the right one. The Indians let loose “a song and dance of triumph,” for “the great and chief God was now become their God.” Before departing, Drake erected a wooden signpost so that all who came after him—specifically Spaniards—would see that the territory belonged to the queen. He proclaimed the land Nova Albion, the first English colony in the Americas.

In 1585, Thomas Harriot, a young Oxford mathematician and astronomer, arrived at the English settlement of Roanoke Island. He had brought gadgets—spring clocks and compasses, magnets and mirrors, rifles and books—and delighted in astonishing the Algonquians he met by demonstrating their functions, as he reported in his Briefe and true report of the new found land of Virginia. Observing these charmed objects, Harriot wrote, the Algonquians gathered that “the truth of god and religion” was “rather to be had from us.” Harriot swore a double oath: that the Indians would find salvation in God, and that the English would have absolute power over them. This vow contained a paradox the Spanish had also encountered. How can you seek supremacy through a faith that teaches the universal brotherhood of man? One mark of divinity is that it can withstand its own contradictions.

When the Algonquians suddenly began to drop dead, Harriot interpreted this “marvelous accident” as a sign that the newly planted English colony was under divine protection. In each village he passed through, a strange disease struck the Indians, while the English remained unscathed—“some people could not tell whether to think us gods or men.”

Several hundred miles north along the same coast, in 1609, Henry Hudson reached the river that now bears his name. The captain disembarked the Dutch ship The Half Moon, filled a cup with wine, and offered it around to the Lenape chieftains there. In 1819, John Heckewelder, an evangelist with the Moravians, the earliest Protestant mission in the Americas, recorded the best-known version of this encounter. He wrote that the Lenape assumed Hudson’s ship must house “Mannitto (the Great or Supreme Being).” Everyone was too afraid to drink the wine until one warrior, fearing the wrath of Mannitto, downed the entire glass, staggered, and collapsed to the ground unconscious, a sacrifice “for the good of the nation.” After the man awoke unharmed and begged for more, the other chieftains also drank themselves into a stupor—and so it was, Heckewelder recounts, that Manhattan got its name: Mannahatanink, meaning “the island or place of general intoxication.” It was a moment of riotous communion; a drunken Eucharist before the conquest of what became New York.

Deification can happen when a man is on his knees or flat on his face, but also through history-writing and footnoting, through edits and omissions. Roger Williams, in his bestselling 1643 Key into the Language of America, translated Mannitto as “God,” yet there is no evidence that it meant anything resembling the Christian concept. Williams observed “a generall Custome amongst them, at the apprehension of any Excellency in Men, Women, Birds, Beasts, Fish, &c. to cry out Manittóo, that is, it is a God, as thus if they see one man excell others in Wisdome, Valour, strength, Activity &c. they cry out Manittóo A God.” Perhaps Manittóo was a compliment taken too seriously: new gods were found in translation.

When Lenape scouts first sighted The Half Moon with Hudson at its helm, they noted that the captain wore red, a color that signified vitality and warfare, joy and anger. According to Heckewelder, they marveled, “He, surely, must be the great Mannitto, but why should he have a white skin?” Here Heckewelder, writing two centuries later, was projecting his contemporary racial sensibility onto their first impressions. It seems unlikely (as the historian Evan Haefeli has argued) that to Lenape eyes the strangers would have appeared “white,” the color of wampum shells and flint. The Dutch, when they controlled the New Netherlands, did not identify themselves as “white” but as “Christians.” And the Lenape’s own early accounts fixate on the peculiar hairiness of the Europeans rather than their skin color—to a society of men who did not grow beards, the new arrivals seemed more akin to otters or bears. Or else the Lenape commented on their eyes, for where they lived, only wolves had blue or green irises.

According to records from the early eighteenth century, natives and new arrivals in the English colonies rarely remarked on skin color or identified one another in such terms. Yet within a few decades, the division of peoples into a trinity of white, black, and red had become common. Barbados, England’s first plantation colony, was the first to witness the transition from “Christian” to “white,” as the colonists sought to separate themselves from their slaves, the islanders, and the small but growing caste of people with mixed ancestry. Like a wind, whiteness travelled north and into the Carolinas, as colonialists from Barbados emigrated there. It took a decade to reach the northeast. Around the early 1720s, indigenous people in the South began to appropriate the label “red.” Long before it became a slur, it was a term of empowerment, evoking ardor and prowess in war. When Carl Linnaeus, in 1740, classified the peoples of the New World as “red” in his Systema Naturae, red skin became enshrined as a scientific category, though it is no more grounded in biology than in the air. The Lenape, for their part, called the sunburned strangers Shuwanakuw. The modern Delaware-English dictionary defines this as “white person.” Yet Shuwanakuw derives not from the word for white, waapii, but from shuwanpuy, meaning “ocean, sea, or saltwater.” White people were those who had emerged from the sea.

***

It was Eve, according to Genesis, who first fell prey to the serpent’s temptation. “Ye shall be as gods,” he advised, with a hiss on the simile. In the New World, too, a woman is usually held to blame for the original mistake. The enslaved woman Malinche, whom Cortés chose as his interpreter and concubine, and who, like a Mexican Eve, would become mother to the first mestizo, is often said to have been the first to call the Spanish men “gods.” Ordinarily, in Anahuac, a person was given a name based on where he came from or what social function he fulfilled. But the strangers who washed up on the beach in 1519 had appeared out of nowhere, and their purpose was unknown. Malinche had to find a word for these inscrutable arrivals. According to the friar Diego Durán, she informed the Indians, “These teules say that they kiss your hands and that they will eat.” Teules, or teotl, translated into Spanish as dios, became the first name the Nahuas would use to denote the strangers.

But in Nahuatl the word did not originally mean anything like God in the Christian sense. It was a principle of divinity that could manifest in anything, from idols to images to human impersonators of gods, sometimes destined for sacrifice: a teotl could be a goddess, a sorcerer, a priest, anyone commanding respect; or the word could be an adjective qualifying something as powerful. The Franciscan Toribio de Benavente, also called Motolinía, wrote that the natives referred to the Spanish as teotl for several years, “until we friars gave the Indians to understand that there is only one God.” In 1524, Motolinía was one of the first twelve missionaries to journey from Spain to the nascent colony, where they erected makeshift classrooms. For them, indigenous Aztec deities were not harmless figments of a pagan imagination but literal minions of Satan. They grew preoccupied by the question of how to kill a god.

One method was baptism: it was said the demons clinging to you would drown in holy water. But water was not enough—the missionaries also had to redefine words like teotl, sifting good from evil, breaking open the very syllables so that whatever was hallowed inside would perish. In the 1530s, the friars selected an obscure word to mean “devil” or “demon,”—tlacatecolotl, Nahuatl for “human owl,” or a malignant, shape-shifting shaman—which they began using to categorize all the indigenous deities in the hope that it would desacralize them. Where for the Nahua divinity existed along a spectrum, the friars sought to impose a binary: man and God, whom they made singular, omniscient, all-powerful, masculine. “His will” was manifest everywhere yet somehow detached from the world. He was One and yet also three—this last concept proved especially complicated for the friars to explain in Nahuatl.

Another enslaved interpreter, named Felipillo, is alleged to have been the first to identify the Spanish in Quechua as viracochas, the sea-foam spirits—a suitable name for mysterious beings who arrived by sea. The word only became singularized in the narratives of early Spanish chroniclers such as Betanzos, Gamboa, and the Jesuit missionary José de Acosta, who identified Viracocha as the Incan prime mover, a white, bearded god who formed humanity out of clay, modeling it after himself. The name would become so closely associated with the new religion brought by the conquistadors that in the first Quechua dictionary, from 1560, viracocha was translated as “Christian.” It came to be used as a general term for “white men” or those of privileged status. Yet originally it had connoted a plural category of primordial, ancestral beings, the founders of cities and villages across the Andes. Viracocha and teotl became vessels for the Europeans’ own monotheism—two words for god, made in their own image. Among the Taíno who first sighted Columbus, to describe a thing as “from heaven,” or turey, was merely to mark it as exotic, unusual, or valuable. For other peoples who found Europeans appearing on their shores, to say that a thing “came from the sky” was just a way to call it something you could neither understand nor explain.

What dangers lie in giving a thing the name that belongs to something else? The first friars in New Spain, messengers from a kingdom in the grip of the Inquisition and its prosecutions for heresy, would not have dared invent a claim that the Spanish were gods. Yet, perceiving that this mistake had been made, they seized on it as proof that their arrival in the New World had been providential. Motolinía argued in the 1530s that the natives mistook the Christians for gods because they had anticipated that Christ’s emissaries would arrive—it was a sign that their conversion was preordained. The Indians, though living in a state of primitive darkness, were correct in sensing that the Spanish had a privileged access to God. The entire project of the Spanish conquest was contingent upon this: in 1493, Pope Alexander VI had issued a papal bull decreeing that the right to annex territory in the New World rested upon the conversion of its natives to the Catholic faith.

When the friars began to teach that the Spanish were not teules, and there was only one God, “some foolish Spaniards took offense at this and complained,” Motolinía recorded. “The fools did this in all seriousness, not considering that they were usurping a name that belongs to God alone.” Their indignation masked a deeper anxiety: If the Spanish were no longer gods but men, and if the Indians had now joined them as fellow Christians, then on what grounds could a distinction between the two populations be maintained? If all belonged to a brotherhood of man under Christ, as Saint Paul had preached, what right did the Spanish have to exploit indigenous labor and land? It was a question famously debated in Valladolid in 1550, when Bartolomé de Las Casas challenged Juan de Sepúlveda over Spain’s moral obligations toward the peoples of the New World. By what other means could European supremacy be preserved in the young colony? It would require a new kind of superpower.

***

Several shades of god arrived in the New World at the same moment. Often omitted from histories is the fact that men from West Africa, kidnapped and enslaved, also participated in the Spanish conquest. A well-known passage from the Florentine Codex says of Cortés and the Spaniards: “They were called and given the names of gods who have come from heaven.” The awkward second half of the sentence is rarely quoted: “and the blacks were called soiled gods.” In the century that followed, over two hundred thousand Africans survived the Middle Passage to toil largely as servants in Spanish homes. The population of enslaved Africans soon vastly outnumbered that of the conquistadors, and threatened to overturn the precarious balance of power in the colony. On both sides of the Atlantic, the legend of European divinity grew, yet any notion that the Africans may also have been mistaken for deities was erased from the myth.

The idea of clean blood, or limpieza de sangre, flowed from Inquisition Spain to the New World. By the end of the fifteenth century, Muslims and Jews had been expelled from the Iberian Peninsula or forced to convert to Catholicism; Spanish officials, in order to exclude the new converts from the institutions of power and prestige—universities, guilds, ecclesiastical positions—implemented a system of access through ancestry, relying on archival records and the testimony of neighbors to determine a candidate’s genealogy. Even a drop of Jewish or Muslim blood was said to confer raza, or race, a word used primarily for breeds of horses and dogs. Any Spaniard hoping for permission to travel to the Eden of the New World had to prove the unsullied contents of his veins.

In the Americas, two separate republics were established—with segregated villages and churches—one for the Indians and one for the Spanish and the enslaved. A legal fiction emerged defining three types of bloods that must not mix: “pure Indian,” “white Spanish,” and “black.” Yet as the mestizo population grew, the boundaries of each sphere became more difficult to police. The nascent colony was fragile, for it was built on fictions, as all societies are. As the minority, the Spanish were fearful that an alliance of Indians and black laborers could easily overpower them. They made access to education and nonmenial jobs dependent on purity of blood, as it was in Spain. In the New World, limpieza de sangre shifted in meaning from a notion of blood based on theological lineage to a biological concept, based on skin tone. Race ceased to lurk in the obscurity of whatever one’s great-grandparents had believed, and became visible, for all who were taught to see it.

In his classroom, Fray Alonso de Molina spoke of sins before they are purged in confession as motliltica, mocatzahuaca, “your blackness, your dirtiness.” Revelation 21:27, translated into Nahuatl and then back into English, comes out as, “Nothing black, nothing dirty will enter heaven.” The friars discovered that in Nahuatl, moral values were often expressed in terms of hygiene, so they began preaching about sin as squalor and framing the Christian sacred as clean, pure, white. Fray Juan de la Anunciación, the author of Christian hagiographies in Nahuatl, described how God revealed the devil to Saint Anthony in his true form: ce tliltic piltontli, “a small black child.”

By the eighteenth century, a fashion had developed for casta oil paintings (the word, like raza, was used for animal breeds), depicting every possible combination of human fauna, with names inspired by the zoo. The various family types, dressed up for their portraits, were presented in hierarchical quadrants. There were the white-skinned Spanish, and then the complex taxonomies of everyone of mano prieta, or “dark hand.” When a white and a semi-white person produced a darker baby, it was called a “return backwards”; a child born to two mestizos was tente en el aire, “suspended in the air,” for they were neither moving toward nor away from whiteness. Blackness would never entirely disappear, the paintings proposed, even after generations of breeding.

Racial difference had become divinely sanctioned, inevitable, as intuitive as the idea, for Europeans, that savage peoples should mistake them for gods. Columbus was lowered from the heavens, Cortés grew scales and feathers, and Pizarro glided over the white foam of the sea. With each retelling, the stories justified European conquest. The mark of a god is the ability to conjure things into existence that did not exist before. With the arrival of the foreign deities, a new concept came into the New World. Forged in flesh and blood and language gone astray, it became indelible, a fiction that deified whiteness—this thing we call race.

Anna Della Subin is a writer, critic, and independent scholar born in New York. Her essays have appeared in The New York Review of Books, Harper’s Magazine, the New York Times, and the London Review of Books. A senior editor at Bidoun, she studied the history of religion at Harvard Divinity School. The above is adapted from Accidental Gods: On Men Unwittingly Turned Divine.

November 28, 2021

“Daddy Was a Number Runner”

Twelve-year-old Francie Coffin is going to be late getting back to school, again. Chatty Mrs. Mackey is delaying her with talk of dreams they both had the night before, dreams about fish. Madame Zora’s dream book gives the number 514 for fish dreams. This is important because Francie has come to collect Mrs. Mackey’s wager on the day’s number. Francie, Mrs. Mackey, and their Harlem neighbors all pin their hopes on “the numbers,” a type of daily underground lottery. Francie collects Mrs. Mackey’s number slip and money on behalf of her father, a neighborhood number runner. As Francie observes, “A number runner is something like Santa Claus and any day you hit the number is Christmas.” Before Francie can make it home to the railroad flat apartment where her mother serves her a dreaded potted-meat sandwich and a weak cup of tea for lunch, she’s chased by Sukie, a bully who also happens to be her best friend. Sukie threatens to “beat the shit out of” Francie yet again. Sukie is evil, light-skinned, and pretty. Francie, who laments being “skinny and black and bad looking,” envies Sukie. Sukie isn’t the only danger lurking around Francie’s tenement. There’s also the bald white man in the doorway to the roof of the building—the same man who had recently followed Francie into a movie theater and gave her a dime before fumbling beneath her skirt.

Forty years after I first read Louise Meriwether’s novel, Daddy Was a Number Runner, I still know these opening scenes like the back of my hand. I reread this book countless times from my elementary school years through high school; it was that good. Meriwether’s writing is beautiful, layered, and gutting. She renders Francie’s story such that it was as accessible and compelling to me as a precocious ten-year-old as it is when I read it today, a testament to Meriwether’s craft. Rereading Daddy Was a Number Runner was like catching up with an old friend. Francie’s fraught world—1934 Harlem—differed from mine in key ways. But as a Black girl reader, I didn’t even know I was hungry to see myself, even partially, in a book until I finally did.

In Jacksonville, Florida, in the seventies, I didn’t leave school in the middle of the day to go home for lunch; I was bussed thirty minutes each way from my Black neighborhood to a white school in the suburbs, thanks to Brown vs. The Board of Education. But both my family and Francie’s had gone on welfare (during the thirties, it was called “relief”). For us, it was only for a brief time, until my young, struggling single mother found a full-time job. Francie’s father couldn’t find work that didn’t insult his pride, and their family lived hand to mouth, even while on relief.

In my world, my father wasn’t a number runner; he worked at a luggage manufacturing plant, and he didn’t live with my mother and me.

In my world, my light-skinned best friend didn’t bully me, but she was considered the cute one, while I was the smart one.

In my world, no one talked to me about sex. I got my incomplete sex education from Jackie Collins novels. But I was still more knowledgeable than sweet, naive Francie who believed “the whores did it,” but not her parents.

But we were both Black girls blossoming, Francie and me. Girls “on the edge of a terrifying womanhood,” as James Baldwin wrote in the novel’s foreword. Where Francie was “flat-chested and hollow,” I was plump; puberty had hit at age nine. Instead of predatory white men, it was Black men, the uncles, brothers, and fathers of my schoolmates, who catcalled and made lewd gestures at me, who made me feel like prey. Unprotected.

***

Published in 1970, a year before I was born, Meriwether’s beloved and critically acclaimed coming-of-age novel takes us through a year in the life of Francie. Her family, friends, and neighbors struggle and look out for one another in the wake of the Great Depression, burdened by relentless poverty, racism, the stigma of “going on relief,” dirty cops, and the ever-present threat of violence at the hands of those inside and outside their community. One of Francie’s older brothers can’t resist the lure of a street gang, while the other tires of being teased by his racist white classmates for being poor.

In addition to the bald white man and other men and boys who accost her, Francie is also molested by two other white men, the neighborhood butcher and the baker, whenever she is alone with them in their shops. These passages detailing assaults on Francie unsettled me during my recent reading, just as they did when I was a young reader, albeit for different reasons. Meriwether’s deft prose captured the tension I felt in my own community as a child who was cherished and looked after, but also at times victimized. As an adult, I read these passages as the mother of two daughters, silently begging Francie to tell somebody, anybody, what was being done to her. But then I remember the times I didn’t tell and the times I did, and how the outcome was the same. Daddy Was a Number Runner testifies to a painful truth: the systems and people who fail Black girls and women have been failing us for a very long time.

The violence Francie experiences isn’t the only reason adult-me wants to reach into the pages and hug her. Like Francie, I was once a child embarrassed by her family’s poverty. Year after year, I refused to bring home the paperwork that would allow me to get free lunch at school, something that would’ve made things easier for my mother. Somehow, though, within the first few weeks of school, I always ended up with a free lunch ticket that burned with shame in my hand. Now, as a mother who has had to buy bread with nickels within the last five years, I wish I could tell Francie that the shame of not having enough in one of the wealthiest nations in the world does not belong to her.

Where I now want to hug Francie and her long-suffering mother, I want to shake some sense into her father. Meriwether portrays him as a loving, involved disciplinarian … until he isn’t. When he feels forced to choose between his dignity and staying with his family, Francie’s father’s warped sense of masculinity leads him to choose the former. As a girl, I shared Francie’s trajectory of first longing for and then being angry with an absent father. As an adult, I feel that ache less acutely now, and as a writer, I appreciate the nuance with which Meriwether has written this character. Francie’s father is at the mercy of the same racist and sexist systems and forces of history that hurt Francie and their community as a whole.

***

In his foreword, Baldwin remarked that Daddy Was a Number Runner was, to his knowledge, the first of its kind, a book from the point of view of a Black girl. (The book was published the same year as Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye and the year after Maya Angelou’s I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, both of which I’d read as a teenager.) Meriwether’s novel, Baldwin went on to say, rendered “the helpless intensity of anguish with which one watches one’s childhood disappear.” And, he noted:

At the heart of this book, which gives it its force, is a child’s growing sense of being one of the victims of a collective rape—for history, and especially and emphatically in the black-white arena, is not the past, it is the present.

Meriwether’s story (or rather, Francie’s) took hold of me, and Baldwin’s foreword contextualized it for me. History, I would learn, wasn’t something that happened apart from me. My story, my experiences, belonged to me, and to the centuries-old story of Black girls in this country.

Daddy Was a Number Runner was the first novel I read that was bursting with history, and the best part was, it was my history. Black history beyond static, toothless narratives about Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks. In the pre-Google era of my childhood, I spent countless hours thumbing through encyclopedias and looking up books in the library’s card catalog to solve the mystery of the real people Meriwether references throughout Francie’s story: the nine Scottsboro boys, ranging in age from twelve to nineteen, falsely accused of raping two white women in Alabama in 1931; Rev. Adam Clayton Powell, the charismatic Harlem pastor, politician, and civil rights leader; the Yoruba people of West Africa from whom Francie’s father proudly claimed lineage; Father Divine, the controversial spiritual leader; and Marcus Garvey, the Black nationalist who inspired activism among some of Francie’s neighbors. Through them, Meriwether showed me dynamic examples of Black forebears as entrepreneurs, as fighters, as self-determining, as invested in the Ghanaian concept of “Sankofa,” which emphasizes looking back at our roots in order to move forward. Meriwether gave me my first glimpse at how Black folks remember and resist.

***

In her 1970 review of Daddy Was a Number Runner for the New York Times, novelist Paule Marshall lauds Meriwether’s layered and nuanced depiction of Black life as akin to “what Ralph Ellison once called the marvelous and the terrible.” Some of my favorite parts of the book are the marvelous moments, such as when Francie’s number, 514, hits and her family “collected a fortune, almost three hundred dollars”; when neighbors lend each other a cup of sugar or slice of bread; when all of Harlem pours into the street to Lindy Hop the night Joe Louis, “The Brown Bomber,” knocks out Max Baer; when Francie’s father plays jazz and blues on the piano and the family sings along; when Francie enjoys a delicious fifteen-cent fried chicken dinner in Father Divine’s basement apartment restaurant.

It is a marvelous moment when Francie’s mother assures her at the end of the novel, “One of these days … we gonna move off these mean streets.” But Francie and her brother Sterling are less hopeful. Reading this ending as a kid, I shared their pessimism about their lives, because of the bleak circumstances. But back then I still believed in a happy ending for my own life. I believed that I could grow up, go to college, and live a more materially comfortable life.

At the same time, I understood that there would be limits, dangers. In Daddy Was a Number Runner, the bald white man who assaults Francie is later killed. Francie’s brother James Jr. and some other neighborhood boys are accused of his murder. While James Jr. is eventually freed, two other boys are sentenced to die in the electric chair. My mother called the police after one of the neighborhood drunks sexually harassed me on the street. I was eleven. The cops told my mother there was nothing they could do. This was my first lesson in how Black girls are not promised justice. Because the world does not see us as worthy of protection.

Forty years later, I think of Francie, young-me, and my daughters when the news breaks about Ma’Khia Bryant, age sixteen, who was shot and killed by police in Columbus, Ohio, within hours of Derek Chauvin being convicted for the murder of George Floyd. Repeatedly in the media, Bryant was referred to as a “woman,” and on social media, commenters blamed her for her own death.

I thought of us earlier this year when in Rochester, New York, a body camera video shows officers handcuffing a nine-year-old Black girl’s hands behind her back, and then pepper spraying her when she resists being put in the police car. There’s a point in the video (which I read about but cannot bear to watch) when an officer says, “You’re acting like a child!” The girl replies, “I am a child!”

I thought of us in 2015 when a South Carolina school resource officer wrapped his arm around a teenage Black girl’s neck, dragged her from her desk, and threw across the floor before arresting her. Her crime? “Disturbing the classroom” by taking too long to put her phone away after her teacher asked her to.

I thought of Francie, young-me, and my daughters when journalist Jim DeRogatis concluded, after twenty years of documenting abuse allegations against singer R. Kelly, “The saddest fact I’ve learned is nobody matters less to our society than young black women. Nobody.”

I will keep coming back to Louise Meriwether’s masterpiece of a novel because in it, she shows us that we do matter. Forty years later, as a reader, I still seek out and prioritize books by and about Black women and girls. I still uplift our stories above all others. When people ask me about writers who inspired me to write my own book—a collection of short stories that centers Black women characters and tells the truth of their lives—I usually credit Toni Morrison and James Baldwin with a nod to their unapologetic centering of Black life, and, in Morrison’s case, centering of free, bold Black women. But it is Meriwether who first planted the seed in me, by writing a novel that centers a Black girl in her own story. Which shouldn’t be a radical thing, but it is.

We are worthy, I hear Meriwether say, and the whole truth of our lives, our dreams, and our struggles, are worthy of a book. We are worthy of protection, care, love, and tenderness. Every day the world lies about us. So every day, we must tell the truth.

Deesha Philyaw’s debut short story collection, The Secret Lives of Church Ladies, won the PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction, the Story Prize, and the Los Angeles Times Book Prize: The Art Seidenbaum Award for First Fiction, and was a finalist for the National Book Award for Fiction. Deesha is a Kimbilio Fiction Fellow and will be the 2022–2023 John and Renée Grisham Writer-in-Residence at the University of Mississippi.

“Daddy Was A Number Runner”

Twelve-year-old Francie Coffin is going to be late getting back to school, again. Chatty Mrs. Mackey is delaying her with talk of dreams they both had the night before, dreams about fish. Madame Zora’s dream book gives the number 514 for fish dreams. This is important because Francie has come to collect Mrs. Mackey’s wager on the day’s number. Francie, Mrs. Mackey, and their Harlem neighbors all pin their hopes on “the numbers,” a type of daily underground lottery. Francie collects Mrs. Mackey’s number slip and money on behalf of her father, a neighborhood number runner. As Francie observes, “A number runner is something like Santa Claus and any day you hit the number is Christmas.” Before Francie can make it home to her railroad flat apartment where her mother serves her a dreaded potted meat sandwich and a weak cup of tea for lunch, she’s chased by Sukie, a bully who also happens to be her best friend. Sukie threatens to “beat the shit out of” Francie yet again. Sukie is evil, light-skinned, and pretty. Francie, who laments being “skinny and black and bad looking,” envies Sukie. Sukie isn’t the only danger lurking around Francie’s tenement. There’s also the bald white man in the doorway to the roof of the building — the same man who had recently followed Francie into a movie theater and gave her a dime before fumbling beneath her skirt.

Forty years after I first read Louise Meriwether’s novel, Daddy Was a Number Runner, I still know these opening scenes like the back of my hand. I re-read this book countless times from my elementary school years through high school; it was that good. Meriwether’s writing is beautiful, layered, and gutting. She renders Francie’s story such that it was as accessible and compelling to me as a precocious ten-year-old as it is when I read it today, a testament to Meriwether’s craft. Re-reading Daddy Was a Number Runner was like catching up with an old friend. Francie’s fraught world — 1934 Harlem — differed from mine in key ways. But as a Black girl reader, I didn’t even know I was hungry to see myself, even partially, in a book until I finally did.

In Jacksonville, Florida, in the 1970s, I didn’t leave school in the middle of the day to go home for lunch; I was bussed 30 minutes each way from my Black neighborhood to a white school in the suburbs, thanks to Brown vs. The Board of Education of Topeka. But both my family and Francie’s had gone on welfare (during the 1930s, it was called “relief”). For us, it was only for a brief time, until my young, struggling single mother found a full-time job. Francie’s father couldn’t find work that didn’t insult his pride, and their family lived hand to mouth, even while on relief.

In my world, my father wasn’t a number runner; he worked at a luggage manufacturing plant, and he didn’t live with my mother and me.

In my world, my light-skinned best friend didn’t bully me, but she was considered the cute one, while I was the smart one.

In my world, no one talked to me about sex. I got my incomplete sex education from Jackie Collins novels. But I was still more knowledgeable than sweet, naive Francie who believed “the whores did it,” but not her parents.

But we were both Black girls blossoming, Francie and me. Girls “on the edge of a terrifying womanhood,” as James Baldwin wrote in the novel’s foreword. Where Francie was “flat-chested and hollow,” I was plump; puberty had hit at age 9. Instead of predatory white men, it was Black men, the uncles, brothers, and fathers of my schoolmates who cat-called and made lewd gestures at me, who made me feel like prey. Unprotected.

***

Published in 1970, a year before I was born, Meriwether’s beloved and critically acclaimed coming-of-age novel takes us through a year in the life of Francie. Her family, friends, and neighbors struggle and look out for one another in the wake of the Great Depression, burdened by relentless poverty, racism, the stigma of “going on relief,” dirty cops, and the ever-present threat of violence at the hands of those inside and outside their community. One of Francie’s older brothers can’t resist the lure of a street gang, while the other tires of being teased by his racist white classmates for being poor.

In addition to the bald white man and other men and boys who accost her, Francie is also molested by two other white men, the neighborhood butcher and the baker, whenever she is alone with them in their shops. These passages detailing assaults on Francie unsettled me during my recent reading, just as they did when I was a young reader, albeit for different reasons. Meriwether’s deft prose captured the tension I felt in my own community as a child who was cherished and looked after, but also at times victimized. As an adult, I read these passages as the mother of two daughters, silently begging Francie to tell somebody, anybody, what was being done to her. But then I remember the times I didn’t tell and the times I did, and how the outcome was the same. Daddy Was a Number Runner testifies to a painful truth: the systems and people who fail Black girls and women have been failing us for a very long time.

The violence Francie experiences isn’t the only reason adult-me wants to reach into the pages and hug her. Like Francie, I was once a child embarrassed by her family’s poverty. Year after year, I refused to bring home the paperwork that would allow me to get free lunch at school, something that would’ve made things easier for my mother. Somehow, though, within the first few weeks of school, I always ended up with a free lunch ticket that burned with shame in my hand. Now, as a mother who has had to buy bread with nickels within the last five years, I wish I could tell Francie that the shame of not having enough in one of the wealthiest nations in the world does not belong to her.

Where I now want to hug Francie and her long-suffering mother, I want to shake some sense into her father. Meriwether portrays him as a loving, involved disciplinarian . . . until he isn’t. When he feels forced to choose between his dignity and staying with his family, Francie’s father’s warped sense of masculinity leads him to choose the former. As a girl, I shared Francie’s trajectory of first longing for and then being angry with an absent father. As an adult, I feel that ache less acutely now, and as a writer, I appreciate the nuance with which Meriwether has written this character. Francie’s father is at the mercy of the same racist and sexist systems and forces of history that hurt Francie and their community as a whole.

***

In his foreword, Baldwin remarked that Daddy Was a Number Runner was, to his knowledge, the first of its kind, a book from the point of view of a black girl. (The book was published the same year as Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye and the year after Maya Angelou’s I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, both of which I’d go on to read as a teenager.) Meriwether’s novel, Baldwin went on to say, rendered “the helpless intensity of anguish with which one watches one’s childhood disappear.” And, he noted:

“At the heart of this book, which gives it its force, is a child’s growing sense of being one of the victims of a collective rape — for history, and especially and emphatically in the black-white arena, is not the past, it is the present.”

Meriwether’s story (or rather, Francie’s) took hold of me, and Baldwin’s foreword contextualized it for me. History, I would learn, wasn’t something that happened apart from me. My story, my experiences, belonged to me, and to the centuries-old story of Black girls in this country.

Daddy Was a Number Runner was the first novel I read that was bursting with history, and the best part: it was my history. Black history beyond static, toothless narratives about Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Rosa Parks. In the pre-Google era of my childhood, I spent countless hours thumbing through encyclopedias and looking up books in the library’s card catalog to solve the mystery of the real people Meriwether references throughout Francie’s story: The nine Scottsboro Boys, ranging in age from 12 to 19, falsely accused or raping two white women in Alabama in 1931; Rev. Adam Clayton Powell, the charismatic Harlem pastor, politician, and civil rights leader; the Yoruba people of West Africa from whom Francie’s father proudly claimed lineage; Father Divine, the controversial spiritual leader; and Marcus Garvey, the Black nationalist who inspired activism among some of Francie’s neighbors. Through them, Meriwether showed me dynamic examples of Black forebears as entrepreneurs; as fighters; as self-determining; as invested in the Ghanaian concept of “Sankofa,” which emphasizes looking back at our roots in order to move forward. Meriwether gave me my first glimpse at how Black folks remember and resist.

***

In her 1970 review of Daddy Was a Number Runner for The New York Times, novelist Paule Marshall lauds Meriwether’s layered and nuanced depiction of Black life as akin to “what Ralph Ellison once called the marvelous and the terrible.” Some of my favorite parts of the book are the marvelous moments, such as when Francie’s number, 514, hits and her family “collected a fortune, almost three hundred dollars”; when neighbors lend each other a cup of sugar or slice of bread; when all of Harlem pours into the street to lindy hop the night Joe Louis, “The Brown Bomber,” knocks out Max Baer; when Francie’s father plays jazz and blues on the piano and the family sings along; when Francie enjoys a delicious fifteen cent fried chicken dinner in Father Divine’s basement apartment restaurant.

It is a marvelous moment when Francie’s mother assures her at the end of the novel, “One of these days . . . we gonna move off these mean streets.” But Francie and her brother Sterling are less hopeful. Reading this ending as a kid, I shared their pessimism about their lives, because of the bleak circumstances. But back then I still believed in a happy ending for my own life. I believed that I could grow up, go to college, and live a more materially comfortable life.

At the same time, I understood that there would be limits, dangers. In Daddy Was a Number Runner, the bald white man who assaults Francie is later killed. Francie’s brother James Jr. and some other neighborhood boys are accused of his murder. While James Jr. is eventually freed, two other boys are sentenced to die in the electric chair. My mother called the police after one of the neighborhood drunks who sexually harassed me on the street. I was eleven. The cops told my mother there was nothing they could do. This was my first lesson in how Black girls are not promised justice. Because the world does not see us as worthy of protection.

Forty years later, I think of Francie, young me, and my daughters when the news breaks about

Ma’Khia Bryant, age 16, who was shot and killed by police in Columbus, Ohio, within hours of Derek Chauvin being convicted for the murder of George Floyd. Repeatedly in the media, Ma’Khia was referred to as a “woman,” and on social media, commenters blamed her for her own death.

I thought of us earlier this year when a Rochester, New York, police body camera video shows officers handcuffing a nine-year-old Black girl’s hands behind her back, and then pepper spraying her when she resists being put in the police car. There’s a point in the video (which I read about but cannot bear to watch) when an officer says, “You’re acting like a child!” The girl replies, “I am a child!”

I thought of us in 2015 when a South Carolina school resource officer wrapped his arm around a teenaged Black girl’s neck, dragged her from her desk, and threw across the floor before arresting her. Her crime? “Disturbing the classroom” by taking too long to put her phone away after her teacher asked her to.

I thought of Francie, young me, and my daughters when journalist Jim DeRogatis concluded, after 20 years of documenting abuse allegations against singer R. Kelly: “The saddest fact I’ve learned is nobody matters less to our society than young black women. Nobody.”

I will keep coming back to Louise Meriwether’s masterpiece of a novel because in it, she shows us that we do matter. Forty years later, as a reader, I still seek out and prioritize books by and about Black women and girls. I still uplift our stories above all others. When people ask me about writers who inspired me to write my own book — a collection of short stories that centers Black women characters and tells the truth of their lives — I usually credit Toni Morrison and James Baldwin with a nod to their unapologetic centering of Black life, and, in Morrison’s case, centering of free, bold Black women. But it is Meriwether who first planted the seed in me, by writing a novel that centers a Black girl in her own story. Which shouldn’t be a radical thing, but it is.

We are worthy, I hear Meriwether say, and the whole truth of our lives, our dreams, and our struggles, are worthy of a book. We are worthy of protection, care, love, and tenderness. Every day the world lies about us. So every day, we must tell the truth.

Deesha Philyaw’s debut short story collection, The Secret Lives of Church Ladies, won the PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction, the Story Prize, and the Los Angeles Times Book Prize: The Art Seidenbaum Award for First Fiction, and was a finalist for the National Book Award for Fiction. Deesha is a Kimbilio Fiction Fellow and will be the 2022–2023 John and Renée Grisham Writer-in-Residence at the University of Mississippi.

November 24, 2021

Thanksgiving with John Ehle

PHOTO: ERICA MACLEAN

The Land Breakers, by John Ehle (1925–2018), the first in the author’s “Mountain Novels” series, is a story of America’s founding, set in the mountains of Appalachia and full of the hardscrabble food of the early settlements—wild turkey hen, deer meat, corn pone. These dishes are historically accurate, like Ehle’s work, but diverge from those traditionally associated with the early American table, at least those represented on holidays like Thanksgiving. Ehle’s novels depart from our traditional patriotic fare in more ways than one: they’re mythic, like all origin stories, but hold a broad view of who should take part in them, and honor the country’s origin without diminishing its moral complexity. To me his food suggested an opportunity for a better Thanksgiving, a project which also allowed me to make cornbread in a skillet, serve an entrée in a gourd, and offer an authentic recipe for buckeye cookies found nowhere else on the Internet.

I made pickled green beans, a welcome lightening-up of a Thanksgiving standby.

The Land Breakers was published as a standalone work by New York Review Books in 2014. The story begins in 1779, with two former indentured servants, Mooney and Imy Wright, arriving at a chain of mountains that have been “left but lately” by the Native Americans. It reflects, to some extent, Ehle’s family history; the writer’s mother came from one of the first three families to settle the western mountains of North Carolina in the eighteenth century, according to the book’s introduction. That family history must have been oral to some extent and peopled by multitudes, because the book and the ones that follow it have a breadth of characters and an ornate, backwoods-vernacular prose style that brilliantly captures the time and place. The effect feels like a correction to some of the more sanitized versions of early American history (including ones I’ve previously cooked from). The books are worth reading for the dialog alone. In one snippet we learn that a man’s feelings “‘ain’t like a wart on his thumb, to be took off with ashes.’” In another, someone new to the neighborhood is told “‘…there was two nice new people last autumn, but they got et by snakes…’” A woman says she’s not finished making supper because the bread is not browned, “‘I ain’t served brownless bread yet, and I’m not going to take up shiftless ways.’” The voices are extraordinary.

Browning was an essential step in making my venison stew tender and flavorful.

Ehle began his career as a writer of radio plays, and later married actor Rosemary Harris (their daughter is the actor Jennifer Ehle). In addition to writing novels and varied non-fiction works, he was an activist, working throughout his life for arts education, diversity in education, and anti-poverty initiatives, and spending two years as an advisor to the governor of North Carolina in the 1960s. Ehle’s nonfiction works include a book on the student civil rights protests at the University of Chapel Hill, published in 1965, and a book on the history of the Cherokee nation, published in 1988. A man of diverse interests, he also wrote a book on how to make French and English wines and cheeses at home.

Like some of the greatest Southern writers of the midcentury—he shares literary DNA with Faulkner and O’Connor—Ehle understood race to be a central feature of American life, and his novels include the full scope of peoples who were part of the American story. In The Land Breakers, enslaved people arrive in the story with the slaveowner Tinkler Harrison, the second settler to follow Mooney and Imy into the mountains, and while they aren’t major characters, their presence is one of the book’s moral poles. Connie, an enslaved woman who works as a midwife, curses Lorry on the birth of her child for the sin inherent to human nature. The curse seems unfair to Lorry, who is one of the book’s quiet heroes, and we’re forced to wonder if her sin is that she assumes she has rights over the land. In The Road, the second of the Mountain Novels, it’s primarily Black convicts who work and die on the railroad construction project that is the book’s setting. The white managers of the road project are the book’s heroes, but again Ehle complicates their accomplishment, linking the process of mastering land with the action of mastering people.

My buckeye cookies were inspired by a buckeye tree in the book, whose falling nuts, along with “acorns, beechnuts and chinkapins…rattled always across the forest floor.”

In Ehle’s fiction, his wideness of vision served a greater project: to show history as made by all types of men—the strong and virtuous, like Mooney Wright and his second wife Lorry; the greedy and prideful, like the slave-owning Tinkler; the ne’er do wells and music-makers, like Ernest Plover and his incredibly-named daughter, Pearlamina. These latter two do no work at all, and Pearlamina is a highlight of the book, precisely for her refusal to “break land” the way the others do. If the book frames the settlement project as a savage conflict between the men and the mountain, which is personified almost as if it were a character in its own right, it also understands the desire to live in peace with nature.

Ehle shines a bright light of humanism onto his characters’ lives, making them ask in their own words what their lives mean, and always finding different answers. There were so many of these passages that I began marking them when they occurred. One character thinks: “we are set not adrift as on a sea, for the sea supports whatever floats on it; we are adrift in the air and and move like dried leaves whisked about…” Another character, talking about his travels, says “the endless trails were like the patterns in a man’s life, always progressing but not going anywhere that could be predicted, yet pleasant.” For Mooney, work is the purpose of life, “[w]ork cutting and splitting until your strength was ebbing…go into the house and eat your supper, deer meat usually, a reminder always that the wilderness was close by, and bread made of new corn, and, of late, a piece of boiled cabbage.” The purpose of his work is to make a family and a home, another topic upon which Ehle excels. Few passages are more beautiful than Lorry’s reflections on the house she and Mooney make, where “they had come to be a family…safe unto itself, in a house that smelled of cooking and herbs and wool and wine vinegar, each one in its special season as the family made for itself comfort and protection.”

Apples appeared in the book, and lady apples are in season. I pickled them according to a recipe by celebrated Southern cooking chef Edna Lewis.

As is often the case in books that are concerned with farming and homes, The Land Breakers goes into great detail about food. The fare is gritty and poor in the settlement’s early days. In Mooney’s first encounter with Pearlamina, he says “‘I have some turkey meat….Got that and milk. Got an egg to eat.’” Pearlamina has nothing but herself to contribute, and makes Mooney “nervous and uneasy, lest she go away.” Later, Lorry wins Mooney with her steadiness, going to his house and leaving him a stew of the humble things: “deer meat…mushy with herb-cooking and brown gravy.” When he goes to her house for the next meal, she has only three potatoes to eat, but also some treasured salt which she has been hiding from her sons in a gourd. She brings it out for Mooney, who says gratefully, “‘I like salt better’n anything on a piece of meat.’” It’s a simple statement that tells much about the privations of settlement life.

For my menu, I skipped the turkey in favor of the deer-meat stew with herbs and gravy, enhanced with dried apples, as a nod to the bit of dried apple Mooney keeps in his shirt to disguise his scent while hunting deer. To decide which leaves to use, I drew from a passage that details the herbs and greens Lorry would forage for: “she would take to the paths and find sallet greens, find poke, cut young green shoots from the wild grape vines, pick leaves of herbs she knew were safe, blue root and dock, for example.” Sallet greens are any green used for cooking and might include sorrel or spinach. Poke is an oniony-tasting poisonous weed that grows in Brooklyn as well as Appalachia, where it’s boiled three times to remove the toxins and considered a delicacy. I’m fairly certain I see it in the summer on the bike path near my Brooklyn apartment. Wild grape leaves are available everywhere in my mother’s metro-Boston suburb. Blue root and dock both inspired rabbit-holes of internet research; the former might be gingery, the other is tart and lemony. I couldn’t forage out-of-season, but it was fascinating to realize how many of these items are available to me, even in the city. I worked ginger, onion and lemon flavors into the finished dish.

Served piping hot, this version of corn-bread is crunchy-chewy perfection. Adding butter and honey would be cheating.

Cornbread is ubiquitous in the books, so I made a corn “pone,” an appropriately austere cornbread often made without eggs or milk. As the farms become more established and successful, Mooney slaughters a pig, and the characters are able to eat more lavish meals, like “fresh meat, field beans, and hot bread.” I re-created the field beans, which research indicates were string beans, and pickled them as Lorry does, with vinegar she has made from muscadine grapes. I did not make my own vinegar, but I did ask my spirits consultant, Hank Zona, for a Muscadine wine to serve with the meal, and he sourced me one from North Carolina, which came with the caveat that it was probably going to be “foxy” and sweet-tasting, and more geographically relevant than good with my meal. Hank also picked a Passe-Tout-Grains from Maison Lou Dumont in Burgundy, based on Ehle’s focus on the wines from Burgundy in his nonfiction work on wine and cheese. This particular type of Burgundy is unusual in that it’s a field blend of Pinot Noir and Gamay, and is more rustic than the region’s usual wines. Its style fit the interest Ehle shows in returning to traditional maker-culture in The Cheeses and Wines of England and France.

Ehle wrote about wines from Burgundy. I served a rustic option in an old-is-new-again style that was intensely flavorful but light-bodied, like my meal.

For dessert, there was an offbeat choice of my own, buckeye cookies. I’m told these are the official cookie of Ohio, not North Carolina, but Mooney and Lorry had a buckeye tree outside their house, which turns yellow in the fall, and drops “its eye-shaped seeds.” This moment in the novel, when Lorry is meditating on the beauty of the land around her, is one of my favorite passages. She concludes that “[a]utumn…in these lush, water-fed lands, was more colorful than springtime.” I love fall, too, and those dropping buckeyes made me crave a football-season standby that’s essentially a peanut-butter ball dipped in chocolate. A friend from Ohio shared his mother’s recipe with me, which is distinguished by adding graham cracker crumbs and shredded coconut to the peanut butter filling, making the buckeyes lighter and less sweet than usual.

My austerity foods were a revelation. The settlers had so few possessions that they often used dried-out gourds for dishware and storage. I served my venison stew in a roasted winter squash, accompanied by corn pone and pickled beans and apples. Mooney fell for Lorry because of these foods, and I understand why. My stew was incredibly savory and tender, and fresh thanks to the “foraged” greens. I ate the whole thing, while scraping out bites of the roasted pumpkin. This entree paired wonderfully with the crispy, light cornbread, the crunchy pickled beans, the sweet pickled apples, and the berries-and-spice profile of the Burgundy wine. If there was a relative lack of sugar, fat, starch and dairy on this table—all the things that make Thankgiving such a gut-bomb—I didn’t miss them. I thought my holiday meal was better than the traditional one, and whipped up easy, too.

I am a Lorry Wright type, so I suggest that readers run out and make my recipes instead of their planned Thanksgivings, dashing about town at the last minute for venison and individual-serving-sized winter squashes. But if you are more a Pearlamina Plover and plan to do no such thing, Ehle forgives you. He writes in his food book that he spends more time thinking about making wine and cheese than actually doing so, and suggests that “[i]f you do nothing more than daydream about making them, I will accept that, for even daydreams will help; daydreams are attitudes after all, and have influence.” These are the views of a man with a subtle and expansive view of history—and who sets a good table, too.

Pickling Spice

This recipe will be used for both the Spiced Lady Apples and the Pickled Field Beans.

1 tbsp: cinnamon chips, fennel seeds

2 tsp: crushed bay leaves

1 tsp: yellow mustard seeds, brown mustard seeds, coriander seeds, allspice berries, peppercorns, dill seeds, fennel seeds, cloves, celery seeds, juniper berries

½ tsp dried chili flakes

Spiced Lady Apples

Adapted from In Pursuit of Flavor, by Edna Lewis. You will need a 1 quart mason jar.

2 cups cider vinegar

2 cups white sugar

½ cup light brown sugar

1 tbsp pickling spice

1 cinnamon stick

3 cups lady apples

Put the vinegar and sugars into a large saucepan. Tie the pickling spices up in a piece of cheesecloth and add to the pot. Add the cinnamon stick. Bring to a simmer and cook gently for 15 minutes.

Wash the apples but don’t destem them. Prick them 3 or 4 times with a knife, and add to the pot. Simmer gently for 30 minutes more. When the apples are tender, remove the pot from the heat and let them cool. Transfer apples and syrup to a 1 quart mason jar.

Pickled Field Beans

You will need a 1 quart mason jar.

1 cup vinegar

1 cup water

2 tbsp sugar

1 tbsp salt

2-inch chunk of ginger

1 tbsp pickling spices

Two large handfuls of green beans

Combine vinegar, water, sugar, salt, ginger and pickling spices in a medium saucepan and bring to a boil. Turn off the heat and set aside to cool. Wash and trim the beans, and arrange them in a mason jar so they’re all standing up and neatly aligned. Stuff in as many as you can; they’ll shrink a little in the liquid.

Set a large pot of water on to boil. Blanch the beans in the water for 30 seconds, then shock them to stop them from cooking in a bowl of cold water with ice. Return the beans to the jar. Add the cooled liquid, cover and refrigerate at least several hours before use.

Corn Pone

2 cups cornmeal

1 tsp salt

1 1/2 cups water

4 tbsp bacon grease or neutral oil

Combine cornmeal and salt in a medium-sized bowl. Add water and stir to combine. Let stand for 2 hours (if time allows), to allow grains to soften and soak up liquid. Add bacon grease or oil to a 9-inch cast-iron skillet. Set the oven to preheat to 475, and put the skillet in so it gets hot. Remove the skillet from the oven and pour in the batter, using a spoon to baste the top with the oil that bubbles up along the sides. Bake for 15-minutes until brown and crispy on the sides. Set the oven to broil for the last 2-3 minutes to brown the top. Let cool before slicing.

Venison Stew Served in a Gourd

Serves 2. This recipe requires an overnight marinade.

2 medium-small winter squashes

1 lb venison stew meat

1 cup buttermilk

4 scallions, chopped

1 cup corn flour

3 strips bacon

3 tbsp neutral oil, as needed

1 tsp minced ginger

1 tsp dried thyme

½ cup dried apples

3 cups water

4 cups washed, chopped greens; I used a mixture of dill, watercress and spinach

Salt and pepper to taste

Prepare the venison by cleaning thoroughly, removing every scrap of membrane and silver skin (essential for the venison to be tender). Cut into 1-inch pieces, add scallions, buttermilk and 1 tsp salt, cover and refrigerate overnight.

On the day you plan to serve the meal, preheat the oven to 400. Cap the squashes and scoop out the seeds. Increase the size of the opening, if necessary, in order to make the squash “bowl” shaped. Rub the insides with olive oil, and season with salt. Place on a roasting pan, and roast for 40 minutes to 1 hour, until the interior is soft and the walls of the squash are visibly softened. Remove and reserve.

Remove the marinade from the refrigerator and allow it to come to room temperature. Cook the bacon in a medium-sized dutch oven. Remove bacon and reserve for another use (alternatively you can crumble it over the finished dish). Leave the grease in the oven; you’ll be using this to make the stew. Remove the venison from the marinade, shaking off excess moisture. Place the cornflour on a plate and season lightly with salt. Dredge the venison pieces in cornflour, shaking off any excess flour.